Chapter 14

Health Insurance Coverage

When Paul R. had a small surgical procedure at his doctor’s office, he was amazed at the $2,500 bill. Since the procedure ultimately resulted in a diagnosis of stomach cancer, it was only the beginning of the surprises.

Unless you are very, very wealthy, medical insurance is your most important asset. This chapter provides an overview of private individual and group health insurance coverage and tips for maximizing their use. If you do not currently have health insurance, ideas are included to help you obtain it.

Section 1. Private Health Insurance—Overview: From Indemnity to Managed Care

Until recently, the average person with health insurance—whether through an employer’s plan, a separate group policy, or through an individual policy—had indemnity coverage. Indemnity insurance permits patients to manage their own care with the freedom to select doctors, hospitals, and treatments. Increasingly, employers and insurers are moving toward so-called managed care plans under which the insurance company “manages” your care by selecting the physicians you can choose and overseeing treatment options. With managed care plans your freedom of choice is limited.

Managed care plans evolved in response to the following perceived problems with indemnity plans, among others:

• The plans were too costly, with no incentive to keep costs down.

• The plans led to the oversupply of specialists and the undersupply of general practitioners.

• The plans raised concern about the quality of unmonitored care.

• The plans failed to emphasize staying healthy and early preventive care.

Unfortunately the managed care trend—while attempting to address all these very real problems at the same time—has resulted in a system that can more precisely be called “managed cost.”

If you don’t have coverage now, knowing what to expect out of both systems will help you obtain the best coverage you can. If you do have one of these coverages, you may want to focus only on the applicable section.

Section 2. Indemnity Health Insurance: An Overview

Evaluating coverage provided by indemnity plans. Under indemnity coverage, the patient receives a service provided by a doctor or hospital. The patient either pays the bill and then obtains reimbursement from the insurer or the bill is submitted directly to the insurer for payment. Reimbursement depends upon the following factors, which are described in greater detail below: whether the service is covered by the plan; the deductible; coinsurance; whether the fees are reasonable and customary; and lifetime benefit limits.

Covered services. Your policy will describe the services that are covered under the plan.

• Medically necessary: Health coverage is generally limited to treatments that are medically necessary. Preventive care is usually not covered.

• Reasonable and necessary fees: Insurers have schedules of fees for covered services that are intended to reflect their reasonable costs. The insured is not prevented from incurring a higher bill for the service, but the insurance company will not pay above the maximum for the particular visit, treatment, or procedure. To illustrate, if the “reasonable and necessary” fee for Paul’s procedure was only $2,000 instead of the $2,500 he was billed, then $2,000 instead of $2,500 becomes the starting place for the calculation.

• Deductibles: A deductible is the amount of covered medical expenses that the insured must pay for each year before any benefits are paid by the insurance company. The idea of the deductible is to eliminate the claims that the insured can absorb without much pain. To illustrate, the starting point for Paul’s procedure for reimbursement purposes was $2,000. If he had a $500 deductible, the insurance carrier would ask for proof of how much Paul had paid in medical bills since the beginning of the policy year. If it was less than $500, the difference between that amount and $500 would be deducted before determining how much the carrier would pay toward the bill. Paul had previously spent $200. So the company would pay $2,000 less $300 (the $500 deductible less $200 he had paid) or $1,700.

• Coinsurance: Coinsurance discourages overuse of the medical system by requiring the insured to pay part of his medical expenses. Indemnity policies generally cover only a percentage of the covered costs incurred, typically 80 percent. To illustrate, let’s take the above example one step further: say that Paul’s policy also had an 80 percent coinsurance provision. The company would only pay 80 percent of the $1,700 or $1,360.

• Lifetime limits: Typically policies have limits on benefits to be paid by the insurance company during the insured’s lifetime of between $250,000 and $1 million.

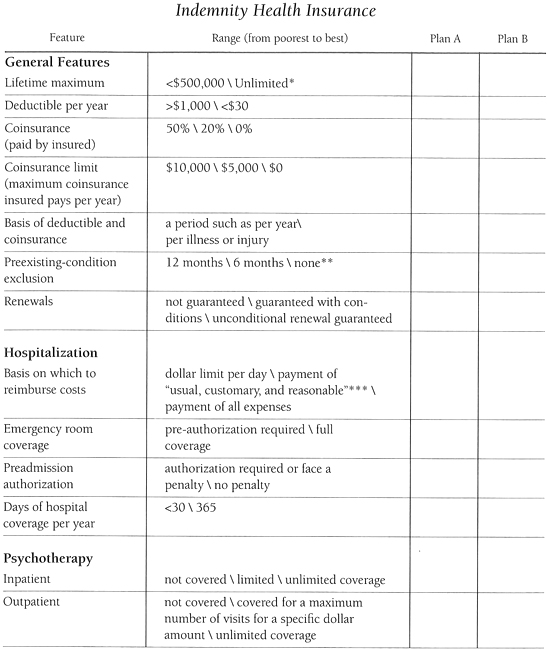

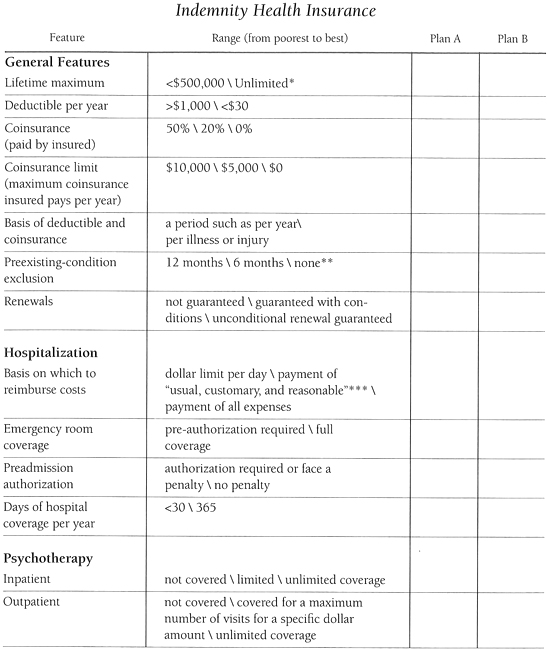

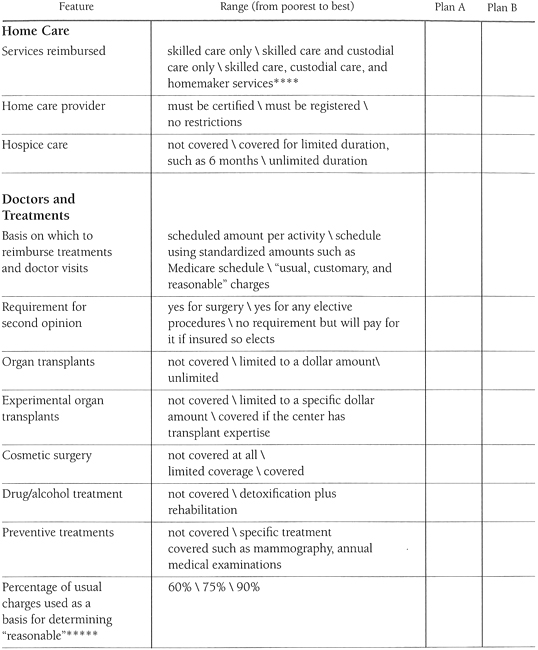

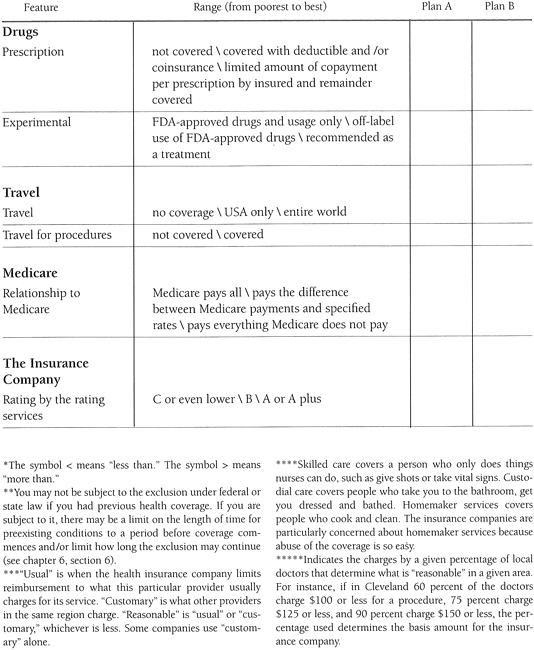

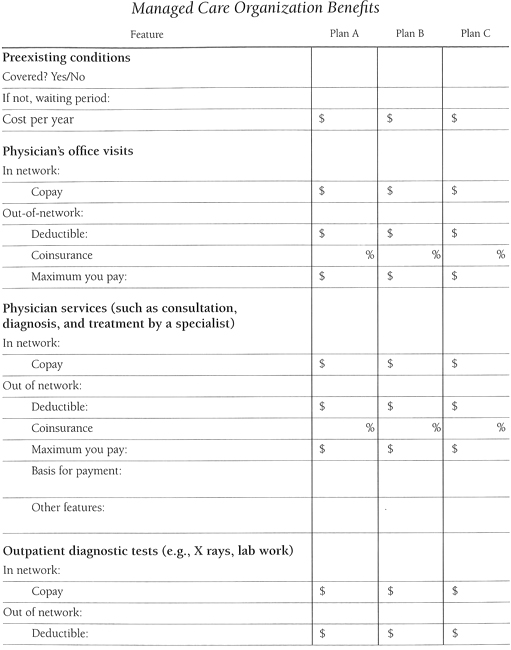

With these general concepts in mind, the chart starting here is a guide to evaluating coverage under a particular plan. It lists various features typically available under indemnity plans. You need to look at your condition (as well as the health of your family if covered) to determine which features may be more important to you.

Columns headed “Plan A” and “Plan B” are provided for your use to help you understand what coverage you have or to compare two coverages.

The amount of the deductible, coinsurance factor, and maximum an insured pays per year are directly related to the amount of the premium.

Tip. Compare premiums at the various alternative limits. It may pay you to take a higher deductible for a lower premium and keep the difference in an interest-bearing bank account. If you are not a person who saves money, it may be better to pay a higher premium for a lower deductible so you won’t have the stress of needing to find cash to pay the deductible when you are not feeling well.

A rule of thumb to consider is not to spend $1 unless you expect to receive at least $3 in benefits.

Tip. As you evaluate the various alternatives, consider whether the features of a particular plan will address the projected statistical progression of your condition and which plan will work out best for you economically. Contact your GuardianOrg for information on the statistical progress of your condition and the potential health care costs to anticipate.

Tip. Indemnity plans send the insured an Explanation of Benefits (EOB) that explains why they paid what they paid (or didn’t). It usually also includes a phone number for questions about payments.

Section 3. Managed Care Health Insurance ↑↑↑

3.1 An Overview

In general. Under managed care plans, a single company pays for and also provides health services. The company collects premiums and then pays the providers directly.

The primary care physician becomes a gatekeeper to the health system. In addition to taking care of your general health, she either opens the gate, referring you to specialists or other treatments, or not. The gatekeeper must follow guidelines that are established by the particular managed care organization (MCO) with respect to treatments, access to specialists, prescription drugs, and procedures and must seek approval for any deviations. Referrals are only to specialists who have also signed up with the MCO. Specialists must also follow guidelines and seek approvals. If you are not referred to the specialist or if the specialist is not in the plan, the MCO will generally not pay.

The facilities in which treatments take place, including hospitals, also must be part of or at least approved by the MCO.

Since it is all part of one system, there are no bills or maximums for the insured to be concerned about. Bills go from the doctor or facility directly to the insurance carrier. There is generally no deductible, and coinsurance is replaced with a copay. A copay is generally a small dollar amount, such as $15, that the insured pays for each access of the system, whether it is for a visit to the doctor’s office or a $1,000 MRI procedure.

Most managed care plans do not impose any waiting periods for preexisting-conditions.

Unlike indemnity policies, managed care plans generally cover preventive care, such as an annual physical examination. The downside is that “managed care” often becomes “managed costs,” and you lose some freedom to determine your medical destiny.

Another concept that is introduced in managed care policies is capitation. Capitation is used as a means of reimbursing physicians with an eye to controlling costs. Under capitation the insurance carrier “capitates,” puts a cap on, what it pays the physician per patient. If, for example, the company pays the doctor $2,000 per year per patient and the doctor sees the patient only one time, she makes money on the patient. However, if she sees the patient once a week, she makes less money.

Tip. If the doctor makes less because you require more attention, that does not necessarily mean you will receive less care. It only means that you should be aware of potential hidden financial forces that may affect the amount of time a physician spends with you on your health care.

Types of managed care organizations. There are several types of managed care plans. In this book, they are referred to generically as MCOs. The types of MCO plans from the least to the most restrictive are:

• Preferred-provider organization (PPO): A preferred-provider organization may be a true MCO if it assumes the insurance function, or it may be simply a group of doctors and/or hospitals with no gatekeeper that have negotiated discounted rates, either capitated or fee for service, to care for a group of people. These doctors and hospitals care for other patients as well. Members can choose services inside or outside the network just as in an indemnity plan, but the cost of services provided by professionals in the network is discounted.

• Point of service plan (POS): Under this system, members have a managed care plan that provides access to any doctors or services within the network. In addition, members can choose to go outside the system to see a physician or for a treatment without a referral. However, the member must pay for a larger portion of such services outside the network (such as an 80 percent coinsurance amount instead of a small copay dollar amount). Claims forms are used for nonnetwork services.

• Individual practice associations (IPA): Members must use doctors and hospitals in the network of affiliated individual practices.

• Health maintenance organization (HMO): Members can only use the doctors on staff at the HMO and the hospitals contracting with the HMO.

3.2 Evaluating Managed Care Plans

Several problems have emerged for patients as a result of managed care’s attempts to manage costs. Because the financial success of the system is based on limiting use of services, there is a built-in incentive to limit patient care. This incentive plays out in different ways depending on the structure of the managed care plan. For example, many MCOs pressure doctors not to recommend costly or promising treatments whether they are covered by the plan or not. Also, MCO policies theoretically pay for out-of-network benefits if in-network specialists document that you require special out-of-network care. However, as a practical matter, in-network doctors may feel pressured not to recommend out-of-network care, or the MCO may not approve it. Examine your plan to know what to look for when managing your care under the plan. Talk with other people in the plan with your condition to learn from their experiences.

The place to start your evaluation is with the gatekeeper, since the gatekeeper is so important to your health. The remaining questions may seem daunting, but the more you know about your coverage, the more likely you’ll be able to make the system work for you. The rule “Before you invest, investigate” applies as much to managed care plans as it does to investments.

The MCO gatekeeper. Gatekeepers (generally referred to as the primary care physician or PCP) can create difficulties for people with a life-challenging condition in several ways:

• Generally the gatekeeper is not a specialist. Since your condition probably requires the attention of a specialist, you would normally have to go to the gatekeeper for permission each time you want to see the specialist. Not only is it a nuisance for you that consumes Life Units, the gatekeeper probably has a financial incentive not to refer you to the specialist.

• Because the gatekeeper is usually a general practitioner, she may lack the experience to detect symptoms or subtle changes that may raise a red flag to the specialist. In general, the earlier a condition is noted, the more likely the treatment will be effective.

Some plans have acknowledged the problem for people with a life-challenging condition by providing that the specialist may also be the primary care physician. Others provide a system of easy access to the specialist by such means as allowing unlimited visits to the specialist once an initial referral is made by the primary care physician, or allowing a fixed number of visits to a specialist before another visit to the primary care physician is required to authorize more specialist visits.

Tip. If your plan does not contain either one of these solutions, ask your specialist to recommend a primary care physician from those available in your plan.

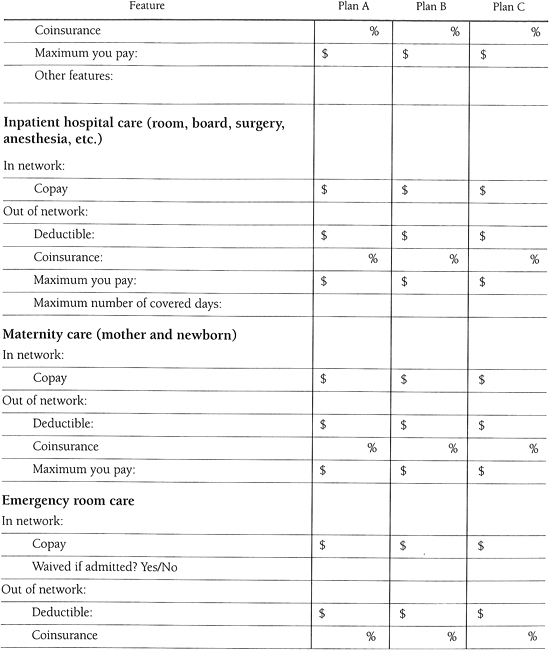

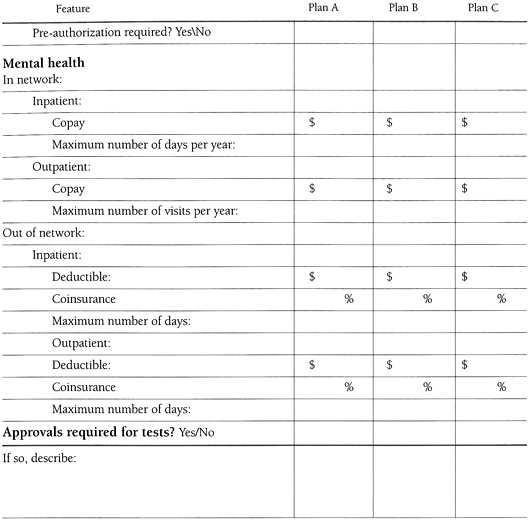

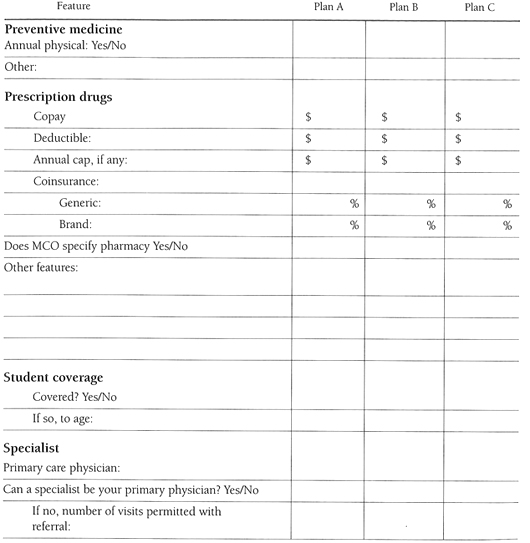

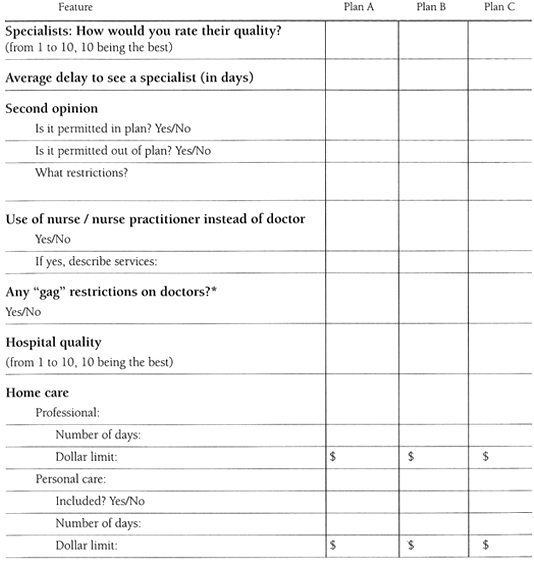

Coverage. The chart here can assist you in evaluating your plan or different MCO plans you may be considering. The first column lists some of the basic features common to managed care plans.

Also consider:

• Intervew the doctor who will be your gatekeeper, and the specialist you will use if different from the gatekeeper. Ask the questions suggested in chapter 24, section 1.4.

• Does the plan provide a consumer advocate, an ombudsman, or a consumer advisory board? If so, how are those people selected?

• Is the MCO “federally qualified”? If it is, one-third of the members of the MCO’s board of directors must be consumer members with no financial relationship with the MCO.

• Does the MCO have a case-manager system for people with a chronic problem? A case manager can go to bat for you and knows how to work the system. Sometimes a case manager can even get you discounts on equipment.

Tip. If you have a choice, select a plan

• with many members who have the same condition you have. The more such members the MCO has, the more experienced and competent it is likely to be in addressing your needs.

• that has qualified specialists and treatment facilities for your condition. If you have a condition such as cancer that has different types, look for specialists in your type. (If you have a strong relationship with a particular doctor, choose a plan that she is in.)

• that provides easy access to those specialists.

• that monitors and coordinates all aspects of your health. This may be more difficult with a network of independent physicians. The plan may even have a “disease management” program for your condition. If it doesn’t, look for a case manager or ombudsman who may be responsible for assisting people with chronic conditions and can go to bat for you.

• that is associated with hospitals that are the best in your area in the specialty you need.

• with the least restrictive options that you can afford. Plans that reimburse you (in whole or in part) for services outside the system assure you access to the specialists and treatments you choose. Generally, the fewer restrictions the higher the cost of the plan.

• with no gag rules.

Tip. Through the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA), a coalition of MCOs and employers, managed care plans can pay to be evaluated. You can obtain a copy of these evaluations for free. Call 800-839-6487 or access them on the Internet at www.ncqa.org. It is also expected that the American Association of Retired Persons (AARP) will be evaluating plans by the time this book is published. AARP can be reached at 202-434-2277. Also, during 1997, new rules were adopted requiring Medicare HMOs to furnish information, at least some of which will be published at www.hcfa.gov. An MCO that has been disciplined for failing to provide medically necessary services or for other infractions is listed in the Cumulative Sanctions report at www.dhhs.gov/progorg/oig.

Section 4. Maximizing Use of Health Insurance (Indemnity and MCO)

In general, whether your coverage is indemnity or managed care.

• Any benefits booklet you receive is merely a summary of the plan’s coverage. You are entitled to, and should obtain, a copy of the complete contract. Obtaining the copy now will allow you to find out exactly what your coverage includes and what you have to do to obtain services under the plan. It will also save time when it could be critical—such as if you need to appeal a decision, at which time you should attach a copy of the pertinent plan provisions.

Start by reading the “definitions” section first. An insurance policy is a contract, and the terms will be defined according to general usage, unless specifically defined in the policy. It may take several readings before the terms of the policy become clear. If you still have questions, ask for assistance from your employer or broker, social worker or GuardianOrg. Asking your employer for assistance in interpreting the provisions will not by itself alert your employer to your condition. Remember, you do not have to disclose your condition to your employer even if she asks.

• If you are told that something is covered, but you don’t see it in the policy or the insurer’s literature, ask for confirmation in writing. If you don’t receive written confirmation, don’t believe it.

• If your policy contains a provision waiving premium payments in the event of disability, check to determine when the insurance company must be notified of the onset of disability for you to be eligible for the waiver. If you do not act within the period mentioned, you may have to continue to pay premiums.

• Your state may require that health insurance policies include certain stated coverage as a matter of right regardless of whether it is spelled out in your policy. Contact your state department of insurance to find out what the law requires. Telephone numbers are included in the resources section.

• Find out as much as you can about the treatment of your illness. See chapter 25, section 3, for how to obtain this information.

• Share the information about maximizing the use of your coverage with others who may be in need of it. In addition to making you feel good, this makes you part of an information network that could provide you with helpful tips as well.

• If you need a letter or report from a physician and don’t have time for delay, write what you want the physician to say. Then deliver it to the doctor (even via fax or E-mail) and ask the doctor to copy it onto her stationery and return it to you.

• Try to establish a friendly relationship with a person at the insurance carrier. Relationships can help speed up matters and are a good basis for getting rules bent.

• Be aware that insurance companies are beginning to distinguish between treatments that are “experimental” (e.g., Phase 1 or 2 of a clinical trial) and those that are “investigational” (e.g., Phase 3) (see chapter 25, section 8.1 for a description of the various phases in clinical trials). The further along in the approval process, the more likely the treatment you want will be covered (see also section 6 below).

• Do not be afraid to be the proverbial “squeaky wheel.” If you have a group plan through your employer, ask your employer to help. The employer can threaten to cancel the contract with the MCO. (The employer may also offer to pay for treatments the plan refuses).

Don’t be afraid to use the insurance company’s appeals process if necessary. Another alternative is to speak with your state’s insurance department. A phone call to your insurance carrier from this regulatory agency on an informal basis often works wonders in getting instant results. If all else fails, get legal assistance.

Tip. Keep your insurance carrier’s name and phone number and your ID number in your wallet in case you need authorization for emergency services or to enter a hospital.

If you have managed care coverage. Especially with managed care, it is important to be proactive. Managed care can be managed by the MCO, the doctor, the employer, or you, the person receiving the care. Think of yourself as a consumer as well as a patient. You are purchasing a product or service—not receiving a benefit. In addition to the above advice:

• It cannot be repeated often enough: choose a primary care physician who is also your specialist if possible. If you can’t do that, see the above alternatives. If you are not already a patient of that person, be sure the doctor is not overloaded and is able to see you as a new patient.

• Due to capitation, many doctors limit the amount of minutes they spend with each patient. If your doctor doesn’t take the time to do a thorough job or answer your questions, complain. For advice on maximizing the use of the time with your doctor, see chapter 24, section 4. If necessary, change doctors.

• MCOs have treatment guides for illnesses that cover procedures the plan believes are appropriate for different conditions. In theory, a guide is supposed to improve health coverage by assuring that all physicians in the plan practice what the carrier considers to be the most up-to-date and appropriate medicine. However, all too often the guides become rigid, and physicians are not allowed to treat people beyond limits prescribed by the guide. Having a copy of this guide helps you to compare what the MCO thinks that your treatment should be against what you think your treatment should be. Guides are hard to obtain, but worth the effort. The best place to start is with your primary care physician, or ask your specialist to obtain the information from your primary care physician. Many physicians will not be forthcoming with these guides for a variety of reasons. Perhaps someone else covered by your plan, or your GuardianOrg, will be able to secure this information for you.

• If your employer changes carriers during treatment, you will likely want the physician who started the process to finish it. Ask your new gatekeeper to recommend that your treatment be continued by your current physician. If necessary, ask for a referral to a sympathetic in-network specialist, then ask that person to recommend that your current physician is the best person to finish the job. If possible, the doctor should also state that staying with your current physician will be the least costly alternative. If necessary, ask your current physician to speak with the MCO.

• If you want a second (or a third) opinion, push for it. If you can afford it, it’s better to go outside the plan to a physician who is likely to be more objective than in-network physicians and may have a different idea of the preferred treatment for your condition. Reports from these doctors may be important to your demand that the plan cover costly or experimental treatments.

• Out of network:

• If you want to go out of the plan for a specific reason, find out how much it will cost and whether any portion of that money will be covered by the plan. Don’t assume without checking that any costs are covered. For example, if you want to use a nonnetwork surgeon and are willing to pay his bill, don’t assume that hospitalization is covered even though the hospital is one that the plan uses.

• Suggest to a doctor within the network who is willing to work with you that care for your condition be handled by a physician outside the MCO. Once a course of action is agreed upon, the doctor within the network could prescribe any recommended drugs and treatments. Consequently, all treatments and drugs, to the extent possible, would be done inside the system. If your current network doctor won’t go along with this suggestion, look for other doctors in the MCO who will. Any agreeable doctor within the MCO will do since the expertise for your condition will be supplied by the outside specialist.

• If you receive reimbursement when you access services out of the network, find out whether the plan will reimburse you based on the out-of-network physician’s bill or a standard such as what is “usual, customary, and reasonable.” If the plan uses the latter type of standard, you will have to pay any difference unless you can convince the plan to the contrary.

• Learn about the procedure for grievances (general complaints) and appeals (requests for reconsideration of requested services and/or treatments you have been denied).

Tip. With an MCO, whenever you feel it is necessary, remind anyone who is making decisions about your treatment that your right to good health care comes before their drive to cut costs.

An excellent guide on how to use an MCO is The HMO Health Care Companion, a Consumer’s Guide to Managed-Care Networks by Alan G. Raymond, HarperPerennial, 1994.

Tip. Since health coverage is so important, if you own your own small business and can’t get health or other coverages such as disability, consider selling your business to a company that will give you the benefits you need—and hopefully eliminate some harmful stress.

Section 5. Claims (Indemnity and MCO)

Paperwork. With indemnity coverage, and some MCO coverages (when accessing a doctor or treatments outside the plan is permitted and will be reimbursed), your expenses will not be paid or reimbursed unless you file a claim with the insurance company in the time prescribed in your policy and in the form required by the carrier (usually on forms the carrier will supply you). With most MCO coverages, when you use the plan’s services, you do not need to file claims as the system does the paperwork for you. If you have a question, rather than guess and have the claim eventually rejected, call the carrier’s claims department and ask for guidance.

Tip. Make copies of all your bills. Keep your originals for follow-up unless your carrier is one of the few that insists on originals. If it does, make a good copy for your file.

Submit claims in the proper order. The patient’s insurance is always primary. The spouse’s coverage is secondary. As between Medicare and private coverage, see chapter 15, section 1.

Tip. If your policy has more than one coinsurance rate, calculate how much you will receive if you submit the bills in different orders, such as the bill with the highest coinsurance first and then vice versa. Keep in mind differing deductibles as well when you do this calculation.

How to submit claims. The safest way to submit claims is to use certified mail, return receipt requested. Signature by the receiving party proves the insurance company received the claim. If you insert the postal receipt number in the letter and keep a copy of the letter, you will also have proof of what was received as well as when it was received.

Records. Keep careful records of your health care expenses. Without them you may not collect the maximum benefits to which you are entitled.

Keep the records in a systematic order. Without a system, your finances can become a jumble quite quickly, and probably at a time when you are not feeling well. Furthermore, depending on your policy, you may have to advance payments to the doctor or facility. This can add up to a lot of money, and you want to be sure to be reimbursed as quickly as possible.

An easy, efficient system for keeping track of claims. Bill C. set up three separate folders. In the first folder he placed all his bills. Since his health policy required that bills be submitted within thirty days of being incurred, he marked his calendar to check this file every two weeks. At that time he submitted all new claims with a cover letter that gave a brief description of what was enclosed. He then placed a copy of the cover letter and the appropriate bills in a second file, which was marked “Claims Submitted, but Not Paid.” As soon as he received reimbursement or was notified the bill was paid, he moved the notification, his letter, and the (now paid) bills to a third file: “Claims Submitted and Paid.” If any other correspondence was received, or telephone conversations occurred concerning any specific bill, that correspondence or notes about those conversations were clipped to the appropriate bill. Whenever Bill checked the file with bills waiting to be submitted, he also checked file two to see if more than twenty days had passed without notice of payment or reimbursement with respect to the bills already submitted. He made sure the system would be continued if he traveled or became incapacitated by putting a note on top of file one describing his system.

If you have access to a computer, you can keep these records on a spread sheet that would show the bill, submission date and amount, as well as the reimbursement date, and amount.

Claims personnel who work for the insurance carrier. Try to develop a friendly relationship with the claims manager or any other claims personnel with whom you work at the insurance carrier. It helps if you direct your inquiries and submissions to the same person every time. While each company has its own rules, a company is made up of human beings, and rules can often be bent if the people in charge want to bend them. Mary F. and her claims manager became so friendly that the manager suggested Mary explore treatments that were more expensive for the carrier but would help resolve a problem for which Mary’s prior treatment had been ineffective.

Tip. Keep a record of all conversations with the insurance carrier, including the date, the time, the person or people with whom you spoke, their direct telephone number if they have one, and the substance of the conversation. If the advice you’re given goes beyond something the person will do right away, ask for confirmation in writing. If the discussion is about medical matters, note the medical expertise of the staff member involved.

Go for the maximum. When it comes to filing claims with the insurance carrier, file claims for everything that relates to your health to ensure that you receive maximum reimbursements. It’s your job, not the carrier’s, to maximize your benefit. Let them deny the claim if it’s not covered.

Assistance. If you need assistance in filing and following up on claims, find out if your GuardianOrg can help. In addition, there are independent claims representatives who will pursue claims for you for a fee. If your GuardianOrg or doctor doesn’t provide a local referral, contact the National Association of Claims Assistance Professionals, Inc. (NACAP), 5329 S. Main Street, Ste. 102, Downers Grove, IL 60515-4845 (800-660-0665). These representatives can also help evaluate current or proposed policies or plans. Check the representative’s experience: even if your state requires licensing, the requirements are minimal.

Section 6. Appeals If Your Claim Is Rejected

If your claim is rejected. First look at why. If something is missing from your claims form or incorrectly stated, correct it and resubmit the claim.

If everything was in order, look at whether you believe your claim is justified. If it is, continue on. Above all, be persistent.

Writing. If the carrier did not put the denial in writing, ask for a letter detailing the reasons why your claim was denied. If it is your doctor who turned down your request, obtain the letter from her. The facts will help in evaluating what you need to do to win your appeal.

Keep a written log of all conversations relevant to your claim, including the information described in the tip on this page.

Usual, reasonable, and customary. If the insurance company refuses to pay more than what it considers “usual, reasonable, and customary” (a standard applied in many indemnity policies), it will be up to you to prove that your doctor’s charge meets the standard. Ask your doctor to write a letter documenting and justifying the charge. Also call specialists in the same geographic area in which you live and ask what they charge for the same procedure. Try to find at least ten specialists. Identify the procedure with the procedure code number that was on your doctor’s bill.

Experimental treatments. Health insurance does not generally pay for experimental treatments. In some states, as long as the drug or treatment is approved for one use, insurers must pay for so-called off-label uses (uses other than the one for which the drug or treatment was approved). Perhaps you can obtain the drug and/or treatment free, or at little cost, by joining a clinical trial (see chapter 25, section 8).

If the carrier does not want to pay for the treatment and/or drugs you want, argue that the treatment is within a generally accepted standard of care for your condition and that it is medically necessary. In addition to asking your doctor for an opinion letter that fits the insurance contract language with supporting documentation such as peer-review study reports, obtain support letters from other specialists in the field performing the same procedure for the stated condition and from national patient-support organizations stating their experience with the acceptance of, and reimbursement for, this procedure. At the least, you should argue that the therapy is the best available for obtaining benefits that will save the insurer money down the line.

Tip. For a free evaluation of the suitability of an experimental treatment by a panel of experts, call the Medical Care Volunteer Ombudsman Program at 301-652-1818.

Cosmetic. If the insurance company claims that a procedure or device is not covered because it is for purposes of appearance rather than medically necessary, e.g., a wig, ask your doctor to write a letter explaining why it is necessary for your physical and/or mental health. The bill you receive should reflect medical necessity as well. For example, if the subject is a wig, ask the wig maker to bill you for a “prosthesis” rather than a “wig.”

Find advocates. If the carrier rejects your requests, look for financial clout and relationships to apply pressure. If your coverage is through your employer, ask your plan benefits manager for assistance immediately upon notification of a claim denial. The employer has more clout than most individuals. The larger the employer, the greater the clout. Also, go back to your doctor and ask her to go to bat for you.

Erma B. had three minor outpatient procedures performed in a plastic surgeon’s office. Each time she asked the doctor’s nurse if she needed her MCO card. Each time she was told no. The fourth visit was a much more extensive procedure. When the doctor’s office asked for authorization from the MCO, it incidentally requested coverage of the prior three visits. The MCO turned down coverage for the first three visits solely because they had not been pre-authorized. Repeated calls by the patient and the primary care physician did no good. Finally the doctor’s office manager reminded an officer of the insurance company she knew that the doctor had been a member of the MCO for five years and would leave if this was not corrected. The MCO relented.

If neither the doctor’s nor the employer’s prodding help, ask for a second opinion from an outside source and have that doctor explain his or her reasoning in writing. While this is the recommended route, if paying for the opinion is a concern, you can usually obtain a second opinion that your plan will pay for if you use a network doctor. You can obtain free information to help bolster your case from your GuardianOrg.

Follow the grievance or appeal process. Pay strict attention to all deadlines. Send copies of all correspondence to your doctor. If you’re not getting what you want, write a letter to your insurance carrier’s administrative review board. The letter should

• state that you are enclosing

• a copy of your medical report prepared by (name of doctor) on (date).

• a statement of the treatment or payment for which you asked.

• a copy of the denial letter.

• include a restatement of the reason or reasons for the denial as contained in the letter.

• state that you want to appeal the denial of the request for (treatment or payment) and describe what you are requesting that was denied.

• describe the part of the plan (whether in your employer’s summary plan description or the summary the insurance company gave you) that covers the matter in question.

• include a copy of all the letters and reports you have gathered supporting your position.

• request that if they deny the appeal, they specify which of your medical records are in their possession as well as all other information that relates to the matter. Then ask the company to tell you, in writing, what portion of the records and the section of the plan description are being used to deny your request. This information will be useful if you have to proceed to a court action. Also ask for the names of the people who made the decision to deny your claim.

• Give them a reasonable deadline by which to respond to you, such as fourteen business days.

You may also consider including a suggestion that if they deny your request, you would like the matter given an external (out of the plan) review. This request may prod them to see the matter differently, even if the plan does not include provision for an external review.

Tip. The hint (not the threat) of publicity may cause an MCO to move toward your point of view. Most companies do not want the publicity, or a lawsuit, about lack of adequate medical care. Be cautious with your hint—threats usually cause people to stiffen their position.

Regulators. If you’re not satisfied with the answer you receive or the speed at which your insurance company is answering you, call your state insurance commissioner and department of health. Be prepared with records of all letters written, calls made, and decisions reached so you can provide a complete picture to the regulators. The prospect of a state regulator being involved may even spur the MCO to resolve the matter in your favor.

As a last resort, you can go to court.

If you lose your appeal for reimbursement. If you have medical expenses that are not reimbursed by your insurance even after exhausting the appeals process, do not just throw the bills away. You may be able to deduct them from your income taxes. See chapter 18, section 3.5. This information is also important if there is an annual maximum on the amount you are required to pay out of pocket.

Section 7. Keeping Health Coverage

Once you have coverage, keeping it in force is critical. As you will see below, you can still obtain health coverage if you lose your current coverage, but the new coverage may be subject to a new preexisting-conditions exclusion or other limitations.

Pay premiums on time. While every policy I’ve seen contains a grace period after the due date in which premiums can be paid without the coverage lapsing, it is better to pay premiums on time. If the insurance carrier is looking to cancel your coverage, you give it an acceptable excuse if your payments are received even one day late. Even if the insurer agrees to continue coverage, it can do so by “reinstating” the policy instead of just continuing it, which would mean that any exclusionary periods could start again from the date of the reinstatement.

Tip. If your budget can handle it, and if the insurance company will allow it, consider paying premiums annually or biannually. The fewer times you make payments, the less likely you will slip up. At least, note the monthly due dates on your calendar in case you don’t receive a premium notice from the carrier or in case someone takes over your affairs for you. Your bank may be able to set up direct payments from your bank account. If you need help paying premiums, government money may be available since it is generally less expensive for the government to pay premiums than to pay for your actual health care costs.

Watch the period in which to exercise rights. If you have coverage through your employer and you leave work, be sure to exercise your COBRA or other right to continue coverage within the time allotted in your plan—usually within thirty days after termination.

If you leave work to go on disability. If you leave work to go on disability, read the discussions in chapter 6 about your right to continue your coverage under COBRA and similar laws as well as the right to extend coverage.

Notice of termination. If you receive a notice of termination of coverage from your insurance company, generally accompanied by a check representing a refund of premiums, do not cash the check! Find out what is going on from your broker or employer. If you are not satisfied with the answer, contact your attorney.

Section 8. Obtaining Health Coverage

If you are currently diagnosed with a life-challenging condition and do not have health insurance, the best way to obtain it is to go to work for an employer that offers health insurance—the better the coverage the better off you are. In fact, good health coverage may even be more important to you than the salary—particularly if it is also accompanied by disability coverage and/or life insurance.

Many plans, especially those of large employers, may not have a preexisting-conditions exclusion. Or you may have rights under HIPAA as described in chapter 6, section 6.

If a new employer’s plan is not the answer, consider the following options:

• Contact your state’s insurance department to find out if your state requires that insurance companies provide an annual “open-enrollment period” during which people with preexisting conditions can obtain coverage. (See the resources section for a listing of the insurance departments.) If your state doesn’t have the requirement, consider moving to one that does. It cannot be emphasized too often how important health insurance is to your physical and financial health.

• Check with the “Blue” health insurance company in your state (e.g., Blue Cross and Blue Shield) to find out if they have an open-enrollment period.

• Watch for companies that are new to your area or that make an attempt to gain market share since they often have an open-enrollment period.

• Check to find out if, in your state, MCOs can deny you coverage or impose a preexisting-conditions exclusion. If they can’t, refer to the MCO evaluation chart starting here to assist in deciding which one to join.

• Perhaps you are a member of or can join a professional or membership association, a union, a fraternal organization, or other group, through which you can purchase group coverage. The more experience and/or training required to become a member of the association, the more likely it will offer health coverage to members and the less restrictive entry requirements will be for any health plan it offers.

• Some twenty-five states have “high risk” insurance pools for people who cannot obtain conventional coverage. Contact your state insurance department for more information including whether there is a waiting list for enrollment. These coverages usually have high premiums even though the states generally subsidize a lot of the cost. They also have limitations on coverage and possibly even periods of preexisting-conditions exclusions—but they are better than nothing.

• Some states have programs for working individuals or small businesses for which you may qualify. If this is of interest, contact your state insurance department. It may even be the extra boost you need to consider starting your own small business if that has been part of your dream.

• Consider dependent coverage under a spouse’s plan. To cover a spouse, all that is needed is a marriage certificate: the two of you do not need to live together. There may be an additional premium to pay, but this is insignificant compared to the benefit. There may not even be an increase in premium if the spouse already has children. If you ultimately divorce, you may be eligible for coverage for thirty-six months as a divorced dependent. (Note: Your spouse may even have spousal life insurance with no medical questions asked.)

• Consider moving to a country that provides medical care, such as Canada or the United Kingdom.

• Veterans with incomes below about $22,000 a year receive care at Veterans Administration hospitals at no cost. Veterans with incomes above about $22,000 a year, regardless of preexisting conditions, can get medical care on a space-available basis at VA hospitals. A veteran need not have been in combat. For nonindigents the charges are reasonable, such as only $2 per prescription. Veterans should contact the Veterans Administration information line at 800-827-1000 to learn more about available health coverages.

• A government program may be available. Review the discussion of Medicare and Medicaid to see if you satisfy or could satisfy eligibility requirements. A government program might also pay for the drugs you need, such as the Ryan White program for people with HIV/AIDS.

Tip. Before signing a health insurance application, be sure any preexisting conditions are listed if requested, and that all information is correct. False information or misrepresentation of health conditions on your application may result in the denial of benefits or cancellation of your coverage at the time you need it most.

Tip. If you are replacing an existing policy with a new one, do not cancel your current policy until you are sure you have been approved by the new company and your coverage is in effect. If there is a preexisting-condition exclusion period in the new policy, maintain your current coverage simultaneously until that period expires.

Section 9. Legal Protections

Federal and state laws do not require that an employer carry health insurance for its employees, or, if it does so, whether and to what extent the employee contributes to the premium payments.

The following laws relate to health coverage:

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA): In general, under HIPAA no employer with two or more employees who offers group health insurance can refuse health coverage to anyone who recently had health coverage. See chapter 6, section 6.

Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA): The federal ADA prohibits discrimination in employee benefit plans. See chapter 6, section 1.

COBRA and other continuations of health care: Under federal and many state laws, you are entitled to continue health coverage provided by an employer after you leave work. See chapter 6 for details.

State laws: As with any insurance coverage, state laws govern health insurance. If you have questions about the laws in your state, contact your state insurance commission (see resources section).

Section 10. Hospital Indemnity (Income) Coverage

Hospital indemnity insurance pays a predetermined amount of money each day you are hospitalized, regardless of the cost of hospitalization or the reason. There is usually a six- to twelve-month elimination period, and it is generally sold with no health questions. Even though the benefit is relatively low per day—such as $100 to $200—payments can quickly add up. For example, if a chemotherapy treatment requires hospitalization overnight, that is two days in the hospital. If treatments are three times a month, the policy provides income of $600 per month. You can use the money for any purpose you choose.

While this coverage is not recommended for the average healthy person because of its expense, it is valuable for someone who anticipates the possibility of hospitalization due to an existing health condition.

Hospital indemnity coverage can often be obtained from your credit card company, as well as your insurance broker. AARP sells hospital indemnity policies to anyone fifty years of age or older, with only a three-month waiting period for preexisting conditions (telephone 800-523-5800). The AARP policy also has additional benefits for a ninety-day period after a hospitalization.

Tip. If you are likely to require hospitalization, consider stockpiling a multiple number of these policies so the money you receive each day you are in the hospital really adds up. Sally F. received a total of $350 a day for each day she was in the hospital—over and above all expenses, which were covered by her medical coverage.

Tax considerations. According to IRS rulings, premiums for a policy providing guaranteed weekly benefits without regard to hospital or medical costs are not deductible. Any proceeds received are not treated as taxable income.

Section 11. Covering the Cost of Long-Term Care

As the name indicates, long-term-care insurance policies cover the cost of long-term care.

If you already have an affordable long-term-care policy of value, continue paying the premiums. If you don’t have this coverage and have been diagnosed with a life-challenging condition, you may be able to obtain it through a new employer. Otherwise it will be difficult to obtain—particularly if you are likely to need the care. Long-term-care policies require medical exams. It is possible to obtain this coverage with an exclusion for your current condition, but I would not recommend it.

For those who don’t have these policies, when it comes to anticipating paying for long-term care

• review your existing medical insurance coverage to see what part of long-term care would be covered.

• review your retirement investing to maximize the amount of money available to cover these costs.

• think about new uses of existing assets (chapters 19–23).

• consider the long-range planning necessary to become eligible for Medicaid long-term care (see chapter 15, section 2.3).

Evaluating long-term-care policies. Under the typical policy, benefits begin sixty days after a doctor certifies that the policyholder has lost the ability to do one or more of the following functions themselves: bathing, dressing, eating, moving without falling, moving from bed to a chair, and getting to the toilet. For an additional premium, the waiting period can be reduced.

The standard policy covers home care and care in a nursing home. At-home services are usually required to be provided through a home-care agency and can be limited to between four and six hours of care per day. Some policies provide direct cash payments for home care, which could allow for the hiring of a companion rather than using a home-care agency.

These policies cover the long term. Better policies have an inflation rider that increases coverage by at least 5 percent per year, and benefits should last at least three years. Preferably there should be a waiver of premium upon entering a facility. Good policies have provisions for respite care (to provide for breaks for family care providers) and adult day care. A policy should be cancelable only for failure to pay premiums. Carefully review the policy to identify exclusions.

Tax. Reimbursement payments received under a long-term-care insurance contract are excluded from income. On per diem contracts, payments up to $175 per day ($63,875 annually) are tax-exempt.

Amounts received from accelerated benefits of life insurance polices can be considered long-term-care benefits. Those are tax free if the benefits are paid to a person considered to be chronically ill and are paid under a contract provision interpreted as qualified long-term-care insurance.

Section 12. Excess Major Medical Policies

Excess major medical policies, also known as catastrophic major medical policies, provide coverage of medical expenses to the outer limits. They are relatively inexpensive to obtain, but have a high deductible, which can range from $5,000 to $50,000. They serve as a safety net over any health coverage limits.

These policies are difficult to find and may contain a waiting period for preexisting conditions of as much as two years. If an individual policy is not available, this coverage may be available through a fraternal or professional association.