Chapter 4

Assessing Your Situation

David B. worked for seven years as a collection manager for a garment manufacturing company. After he took a look at how much he spent on his job, including gas, oil, repairs on the car, lunches, keeping his business shirts and suits clean and pressed, and, as he said, “a little here and a little there,” he found he could stay at home, work part-time near where he lived, and save money even though he only made half of what he had been making.

David took two of the concepts described in this chapter, True Net Pay and Life Units, and applied them to his own situation.

To prepare for the worst, it is important to examine your own situation honestly. At the same time, the sooner you identify and plan for your goals, the better the chances are that you will be able to take the necessary steps to meet them.

This chapter starts with the place where you probably spend most of your waking hours, your work. If you’re like the vast majority people who have done this exercise, you’re in for a surprise.

If you don’t work, at least read section 1.2 before skipping to section 2.

Section 1. Your Employment

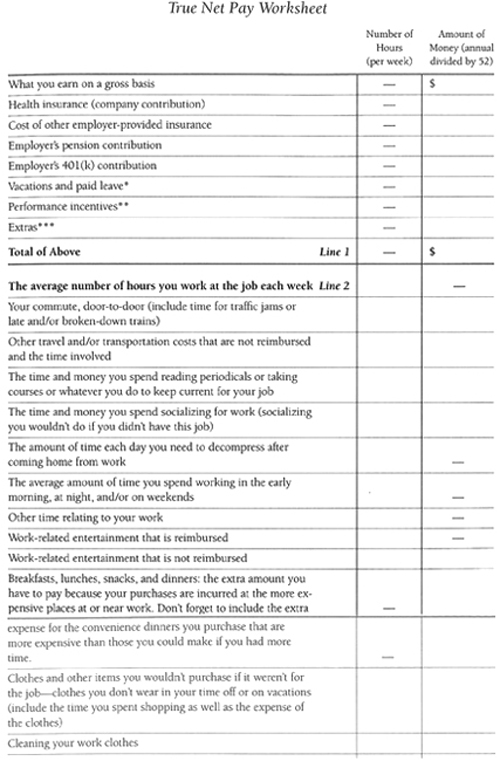

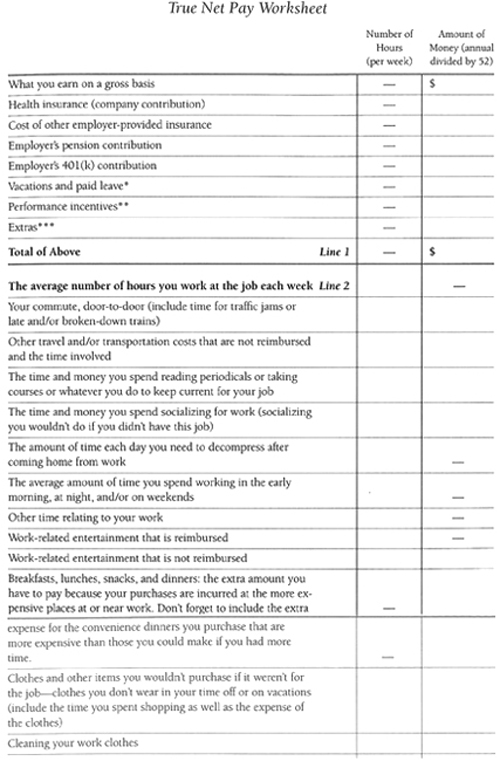

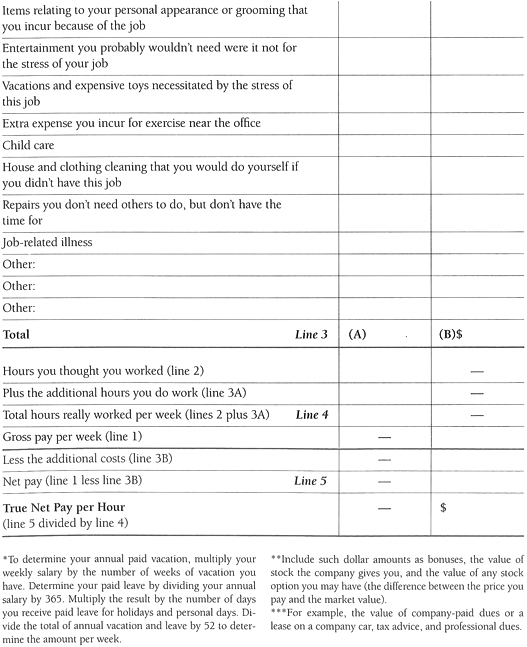

1.1 True Net Pay

Evaluating your net pay. Regardless of whether you work for others or are self-employed, if I asked you how much you earn per hour, you would probably either tell me the dollar amount if you work on a straight hourly basis or your weekly or monthly pay divided by what you think of as your workweek, usually between thirty-five and forty hours. However, this equation only begins to tell the story. Many incidental costs, both in money and time, are connected with any job.

To determine your True Net Pay, the amount you actually earn per hour before tax, complete the worksheet here (if you do not have actual amounts, use estimates). The odds are, you’re in for a surprise.

1.2 Life Units

The term Life Units reflects the amount of hours of our lives we spend to do something. If your True Net Pay is $10 an hour and you want to purchase a shirt that costs $40, it will require trading four hours of your Life Units to purchase that shirt. That’s 4 hours out of the 8,760 hours in a year, which really equates to 4,380 useful hours when you realize approximately 50 percent of our hours are devoted to necessary body maintenance, i.e., sleeping, eating, eliminating, washing, grooming, and exercising. If you have a life expectancy of twenty years, that’s 87,600 useful hours; thirty years is 131,400 useful hours.

Life Units are precious. They are limited and cannot be replaced. Healthy people tend to think of hours on this planet as infinite. However, this is not true of anyone who has realized at some point that he or she may have a life-challenging condition. Even if your condition is in remission or is entirely gone, you will never again view time in the same way. Whether life continues for a day or forty years, time will always be more precious.

1.3 Fulfillment

Now that you have an idea of your True Net Pay, and the real amount of hours you devote to your job, let’s focus on a more subjective ideal—fulfillment. Remember, the happier and more positive you are, the healthier and longer your life is likely to be.

If you feel fulfilled in your work, or even content, then skip this section. If you want more out of work, read on.

Assessing fulfillment. If the world is truly your oyster, and you could do anything you want, is your current job what you would do?

If the answer doesn’t immediately spring to mind, a few questions may help guide you in deciding what fulfillment means for you, and how much you find in your job. As you answer these questions, be aware, and let go, of the strong pull in our society to define ourselves by our jobs. We’ve come to identify ourselves and our self-worth with our jobs to the degree that we don’t say, “I do carpentry or law.” We say, “I am a carpenter or I am a lawyer.” Ask yourself:

• Would you do your job if you didn’t have to work for a living? If not, what would you want to do if you didn’t have to earn money?

• What did you want to be when you grew up?

• What have you done in your life that makes you proud?

• If you knew you were going to die within a year, how would you spend that time?

1.4 Two People in a Single Economic Unit

If you and a spouse or life partner form a single economic unit, consider looking at True Net Pay and fulfillment for each of you. Most families with two incomes spend large amounts of money on items that are needed because both people are working. For instance, if only one person were working there would be little need for child care, convenience foods, restaurants, and housecleaning. If both people are fulfilled in their jobs and there is a net income from both jobs, then the exercise may be unnecessary. But if one of the people is less than satisfied at his or her job, the value of the income of the less fulfilled partner may not be worth the lack of fulfillment.

If you do the calculation, subtract from the income of the less fulfilled partner the cost of all the convenience items. If you combine taxes, figure the tax on the income of the less fulfilled partner by calculating the taxes on the two incomes together, then the taxes on the fulfilled partner’s income alone. Subtract the difference from the less fulfilled person’s income. Again, you will probably be surprised at the results. However, before eliminating the less fulfilled person’s job, make sure you consider the value of that person’s health and other benefits.

Section 2. A Financial Snapshot: Today

This section shows you how to put the information you’ve just gathered into the picture you’ll need to assess your situation. You don’t have to wait until the information comes back from the credit bureau, SSA, or even the MIB. You’ll only need the information described in chapter 3, section 7, “Your Financial Information.”

For purposes of this chapter, the reference is to “your” finances. If you are part of a couple, and you combine your income and/or expenses, the numbers you insert in the various worksheets should reflect that. Likewise, your goals should reflect your goals together.

When amounts of money are discussed, you only need a ballpark estimate—not the exact dollar amounts. Round off the numbers to the nearest $100 or $500 or whatever works for you. If you can’t find a number readily, let’s say within five minutes, then estimate it using your best guess. Please don’t make any major financial decisions until you replace the estimated numbers with more accurate ones. When you eventually locate the accurate information, you can return to the form and update it.

As you put these numbers together, remember, no shame and no blame. This is not the time to kick yourself for the investment that did not do well or the investment you didn’t make that made your least favorite person rich.

You may want to make copies of the forms so that you can reassess your situation in the future.

Tip. Don’t worry if your numbers indicate a shortfall. We will focus on appropriate treatments for your situation in later chapters.

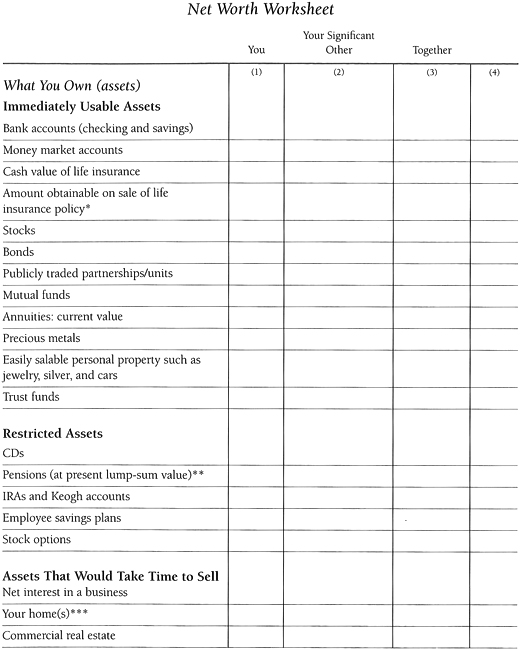

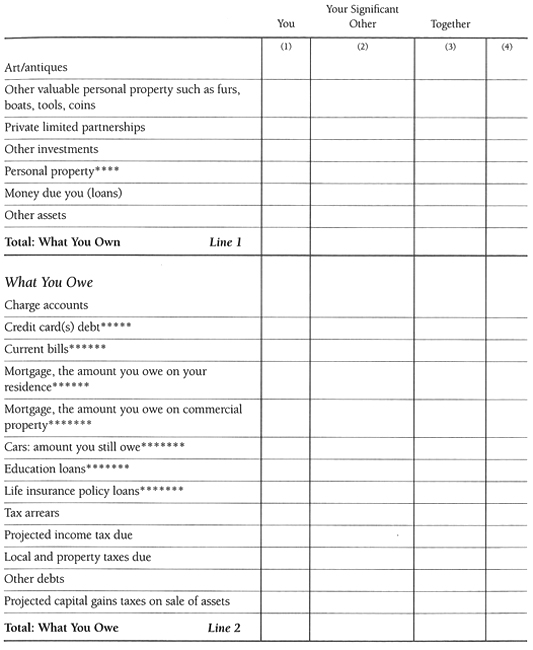

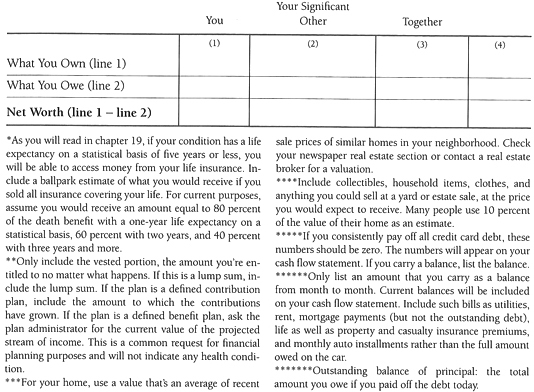

2.1 Net Worth

The first goal is to determine your net worth: how much you are worth today after all the things you own and all the amounts you owe are taken into account. Finding this number is really no more difficult than completing a credit card application.

If you have completed a Net Worth statement recently, pull it out and skip the rest of this section. If not, the form starting here will provide an easy mechanism for determining your Net Worth.

There are a few instructions you should be aware of:

• Use only the first three columns for now.

• When you insert numbers that are for items other than cash or cash equivalents (such as stocks and bonds or certificates of deposit and anything else that can quickly be converted to cash), estimate what you would get if you sold them today—not what you would like to obtain or what you paid or a fictitious insurance value.

• Include the full value of each item in what you own, without deducting any debt or mortgage you owe with respect to that asset. You will be asked to list the mortgage or debt due under the heading of “what you owe.”

• When you list what you owe, include what you owe today, not what you may owe at some future time.

• Keep things simple by using the balances from your last statements instead of trying to add on any new purchases or subtracting any payments from the last statement.

• For future reference, retain a brief description of where or how you obtained your values.

Tip. There are probably as many different worksheets for determining Net Worth as there are books and computer programs on the subject. If you are more comfortable with another worksheet, please use that one. A word of caution: If you use another worksheet or software program, look for a hidden agenda. Many programs are reasonably priced and provide much useful information, but they basically exist to help promote the company’s financial products. You can judge a software program by the following criteria: First and foremost, it should be easy to use. Second, it should be flexible, allowing you to try a number of “what-if” scenarios, and even to change the program’s assumptions. Third, it should be informative, explaining the concepts. There is no single answer—so if the program says there is, pass it by.

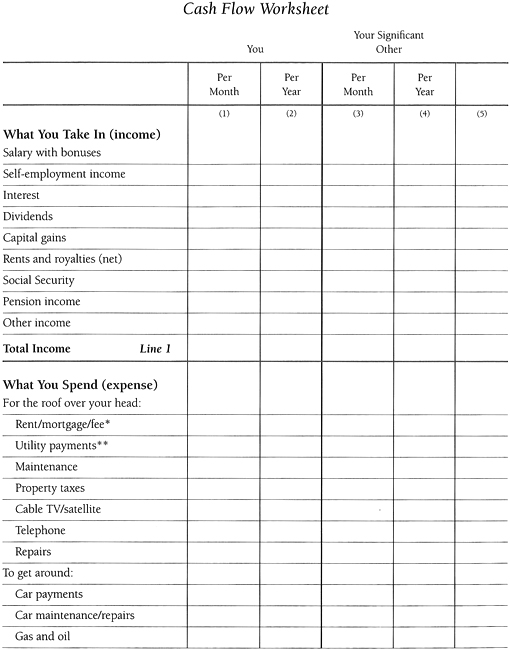

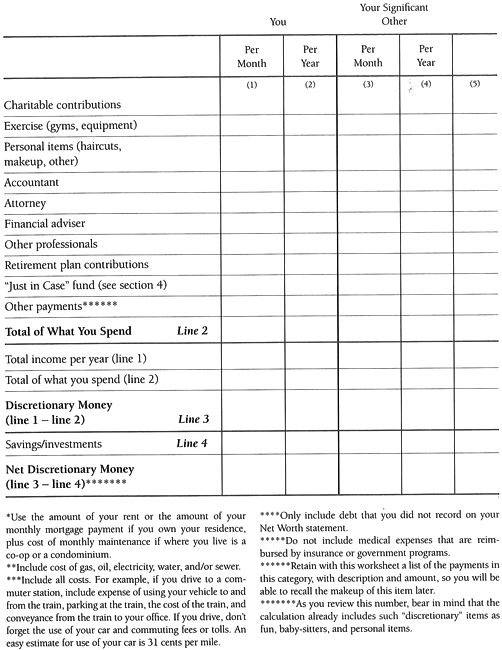

2.2 Cash Flow

Now that you know your net worth, the next step is to determine your cash flow—what and how much money comes in and where it goes.

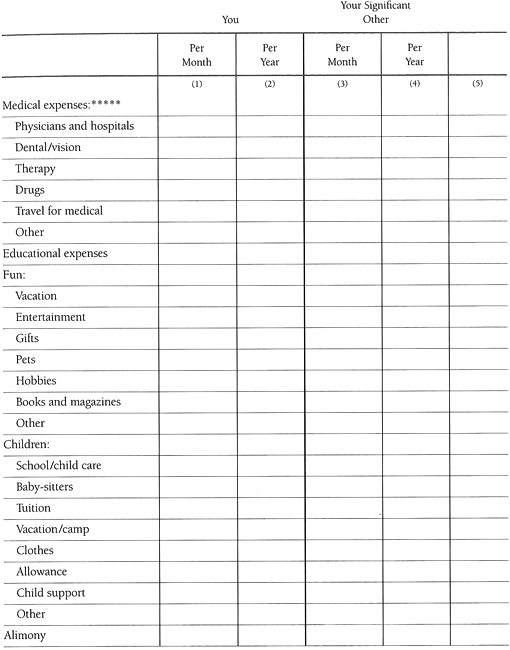

Adapt the Cash Flow worksheet starting here as necessary to reflect your particular situation. The goal is to include all your regular and unusual income and expense.

Before you start. Some guidelines are:

• Please make several photocopies of this worksheet. You’ll use one now, and you may wish to use other copies to periodically check where you are in the future. Keep at least one blank copy for use with the discussion in chapter 17.

• Cash expenditures will probably be hard to reconstruct, but you can come up with a pretty good estimate if you think about a typical week and how often you buy things for cash. For example, if you eat lunch at work five days a week and that’s $7 a shot, that’s $140 a month. An alternative is to keep track of your spending for a week, or even just one typical weekday and one typical weekend day, and estimate your weekly spending based on those days.

• It will help to pull out a current pay stub, which shows your income for the year to date as well as all deductions, and last year’s W-2 or pay summary, showing income and withholdings.

• For now, we are interested only in the columns headed “Per Month” and “Per Year.” The rest of the worksheet will become relevant later.

Tip. To take control of your financial situation, you need to know how much money you spend daily and on what. In a notebook or a budget workbook (available from any stationery store), track all your expenses, in detail, for the next three months to find out where your money really goes. Categorize your spending narrowly. For example, say “movies” or “theater” instead of “entertainment.” Write down every penny you spend. Don’t forget to include the cash you get from the ATM. An easy method is to keep the cash withdrawal slip in your wallet and note on it your expenditures every time you pull out your wallet to get cash. Don’t try to do anything about your spending pattern: the key is to first get a handle on it.

Section 3. A Financial Snapshot: If You Become Disabled

Now that you know where you are today, let’s take a look at what would happen in a reasonable period of time, say two years, in the event that your condition leads to a disability likely to last more than twelve months. The underlying assumption is that for the next two years you have income and expense that are the same as you now have, and that you then become disabled. Hopefully, you will not become disabled—but you don’t want to be caught short if it happens. Again, if this exercise comes up with a shortfall, don’t worry. That is what this book will help you through.

3.1 Net Worth in Two Years

Use column (4) on the Net Worth worksheet starting here to reflect an assumed date to go on disability (e.g., two years).

• Net money: Look at the Net Discretionary Money you just calculated and estimate how much of that you will be able to save each year until then. Add that amount to an account you’re likely to put the money in. For example, if you normally put any net income remaining after expense in your savings account, include it there.

• Mutual funds and other investments: Change the amount to reflect what you conservatively estimate the value will be. The goal here is to try to find out what reality, rather than your dream, would be like. An average increase over the past five years may be a good guide to the future, unless those years have been exceptionally good or not so good.

• Retirement plans: Include the amount of money you would be able to access at or before the time you become disabled.

• Life insurance: Increase the amount obtainable on a sale to reflect decreased life expectancy due to the passage of years, even though new drugs or treatments may occur to change this projection.

• Other assets: Add in other assets you may gain access to, such as money in a trust fund that you gain control over during this time.

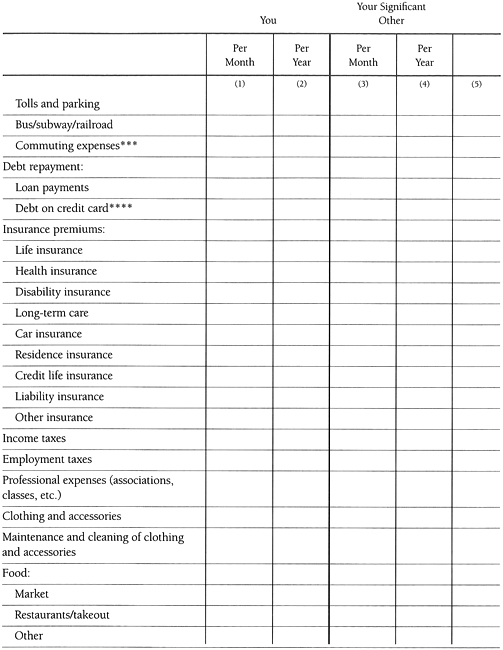

3.2 Cash Flow on Disability

Using column (5) of the Cash Flow worksheet, label it “Disability” and create a projection of what would happen if you become disabled. Start with the numbers you’ve already filled in and make the following adjustments, using realistic instead of optimistic projections:

What you take in (income).

• Salary: Include the amount of net income you would continue to receive under any long-term formal or informal plan your employer uses. There is no reason to include a short-term disability plan since, by definition, it is only short-term and won’t give you a true picture of what it will be like to be on long-term disability.

• Bonuses: Include them if any can reasonably be anticipated.

• Self-employment income: Include any self-employment income you can reasonably foresee even if you are disabled.

• Interest, dividends, and capital gains: Adjust these numbers to reflect any principal or savings you may have to take out to live on.

• Social Security: If you already have the response from SSA, use the numbers they note as a ballpark. If you don’t have their form yet and have worked at least forty calendar quarters in the past ten years, then approximate a number based on the following: The average award is between $700 and $800 a month. The current maximum award is approximately $1,200 a month. Awards are even less if you worked less than the required quarters. Note: If you will receive disability from your employer, check to see if the amount includes or is in addition to any payments you may be entitled to receive from SSA. If it includes Social Security, then note Social Security income at zero since it will already be included in your income from your employer.

• Pension income: What you can expect to receive per month on disability.

• Other income: Include any money you will receive from private disability policies as well as any money you may receive from an association, union, or religious organization to which you belong. If the policy requires a deduction for Social Security payments, put the gross income here, and put zero in the Social Security space. Also, include all income you can expect from any other source (e.g., perhaps acknowledging the contribution you made to their lives, your children have agreed to give you a monthly income).

What you spend (expense).

Medical expense: Since the assumption is that your condition creates an expense during the next two years, estimate the amount of medical expense that will not be reimbursable from your insurance company, employer, or government program. The simplest projection may be to use the numbers you obtained as part of the “average” cost curve with respect to your condition (see chapter 3, section 4), less the amount you will be reimbursed. If you want to try to get a more accurate grasp of your own situation, use the following calculations instead, less the amount of any reimbursement.

Physician expense: Include attending physician and any specialists.

Medical travel: Include the cost of going to and from the doctor or the hospital and parking. This may not seem like a lot of money, but Connie T. took approximately three hundred trips to the doctor in a year.

Medical supplies: Not generally covered by insurance since they are not prescription items.

Psychotherapy: Even if it is covered, coverage is usually for a limited number of visits and the amount of overall coverage may be limited as well.

Home care: Most insurance coverages limit the number of visits. Most companies will waive the limit if they think the only alternative is expensive hospitalization, but don’t count on it.

Prescription drugs: Medicare does not cover any prescription drugs out of the hospital, unless you have MediGap plan “J.” Many other plans have drug caps of limited amounts, such as $500 per year.

Private hospital room differential: If you want to use a single room in a hospital instead of a double, you have to pay the difference. This can be at least several hundred dollars a day. Generally, hospitals only move patients to single rooms at no additional cost when the patient is deemed to be contagious.

Medical insurance premiums: Once an employee shifts to disability, she has to pay the full cost of the premiums that before were often paid in full or in part by the employer. Generally, for the first eighteen months of disability, premiums may not exceed 102 percent of what the employer continues to pay for the coverage. For months nineteen to twenty-eight, the premiums can escalate to 150 percent of the premiums the employer pays. If a right to convert to individual coverage exists, approximate the premiums for the individual coverage or use the figure charged for premiums during disability.

Deductibles: Include the amount that may be payable with respect to health insurance.

Coinsurance or copayments: All types of health insurance require that you pay some part of your medical expense. This is called coinsurance in indemnity-type plans, or a copayment in managed-care plans. Copayments of $15 or $20 may not seem like a lot, but they can add up to $500 or $600 per year. Sometimes they are capped. Often, they are not.

Usual, customary, and reasonable: If you have indemnity health coverage, there may be amounts payable in excess of “usual, customary, and reasonable” charges.

Alternative therapies: These therapies, such as Eastern medicine and disciplines, are not generally covered by health plans, although some plans may cover them.

Experimental treatments: Any new drugs that are not yet approved by the federal Food and Drug Administration are “experimental” and not reimbursed without a struggle, if at all. Sometimes even new uses of approved drugs are considered experimental.

Clinical trials: If you participate in a study of an experimental drug (see chapter 25, section 8), you may incur expenses that are not reimbursed, such as travel and outside tests.

• Clothing: Reduce the expense to the cost of the clothes you will need if you’re not working.

• Food: You will no longer need expensive meals at work and may have time to cook more. On the other hand, you may plan to eat a special diet that costs more money.

• In general: As you look at the rest of the items, remember that you are no longer working. Perhaps that means less in child care, or maybe it means more because of your disability. You may not need vacations anymore or you may want to take the vacations you’ve been postponing. Whatever your situation, think about how it could reasonably be expected to change and insert the number that results. The rule of thumb for a person on retirement without additional medical bills is that expenses are 70 to 80 percent of preretirement expenses.

As you prepare your worksheet, also include items that apply to everyone, regardless of health history, such as:

• Inflation: Adjust all numbers for reasonably anticipated inflation.

• Residence, including mortgage or rent, utility payments, maintenance of residence, property taxes: Adjust to reflect a possible change in where you live, which may be required by your condition. Even if there is no change, factor in the increases you can expect, such as in property taxes or in rent/maintenance.

• Taxes: Estimate to reflect what they would be with your new income. If there is a net change from your current income, call the IRS for a free estimate of the tax rate at the different net income at 800-829-1040.

Section 4. A Financial Snapshot: Your Goals

You’ve just worked through a forecast to obtain an idea of what would happen if you have to stop work and go on disability in the future. It’s worth taking a few minutes to do another forecast, except this one is at the opposite extreme: What are your goals, and from today’s vantage point, if you remain healthy, how close are you to realizing those goals? For example, do you want to pay college tuition for a child? Have funds for your retirement? For another purpose?

A general rule of thumb to determine how much you will need if you retire is to multiply your annual expenses by 0.7 if you have children living at home, or 0.6 if your children have left home.

A “just in case” fund. One of the goals you should consider is setting aside liquid assets to serve as

• a contingency fund, which should be large enough for you to weather unexpected decreases in your income.

• an emergency fund, to weather unforeseeable emergencies.

• a cure fund, to cover the purchase of the cure that will hopefully be developed for your condition, as well as the expense of revamping your life at that point.

Tip. While the following section describes the preferred amount to retain as your Just in Case Fund, the practical goal is to do whatever you can. Just do your best. Create and add to the fund at whatever level you can. Doing anything is better than doing nothing at all. Don’t make yourself nuts.

Ideally, the Just in Case Fund should equal your anticipated fixed and variable expenses for twelve months. At the least, the fund should equal an amount for your Cure Fund, which considering the current cost of new drugs and treatments should be between $15,000 and $20,000, plus an Emergency Fund equal to a multiple of your income. If you work for the government, the Emergency Fund should be at least three months of income; if you are self-employed, if your income fluctuates, your work is seasonal, or if you rely on commissions, your job or income may be more at risk, and six months would be more reasonable. If you work for a private employer with a steady income, the fund should be approximately four and a half months. If your income greatly exceeds your expenses, your fund should be at least the equivalent of the above number of months’ worth of fixed and variable expenses.

If you are part of a two-income unit, consider the likelihood that you will both lose your jobs at the same time. The likelihood may be high if you both work for the same employer. At the other extreme, it would be very unlikely if you work in fields that are affected differently by the same economic conditions. For example, if one of you works as a bankruptcy attorney and the other sells luxury items, a downturn in the economy would affect each of your incomes differently. If the likelihood is low that you will both lose your jobs, then a Contingency Fund equal to three months’ expenses plus $20,000 for a Cure Fund would be reasonable.

You can make do with less cash if you have credit available or if there are assets you can easily borrow against, such as a retirement plan at work.

It is preferable that these funds be retained in a low-risk liquid asset (see chapter 13).

Tip. To work up to the necessary funds, think of payments into your Just in Case Fund as a priority debt that has to be paid every week. Make payments convenient: consider asking your employer to deposit a portion of your paycheck into a savings/investment account, or ask your bank to make automatic transfers. Start off easily, at perhaps 5 percent of your income, and work up to your optimal savings rate. The amount you start with is less important than getting started. The habit of saving is what becomes critical. Keeping a chart of your progress may help you reach your goals.

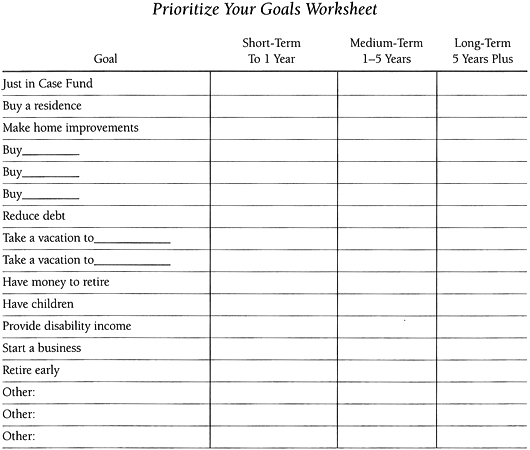

Prioritize goals. Once you have identified your goals, unless you have a large amount of resources, you need to quantify and prioritize them. The worksheet below will assist you in setting your priorities. Fill in a number between 1 and 10, 10 being something that is of most importance to you.

Once you have prioritized your goals, you need to turn them into dollar amounts so you can determine how much money you will need, and when you will need it. For example, if you want to purchase a house, you need to estimate how much it will cost, how much you will need as a down payment, and when. From there, you can estimate how much you have to save and over what time.

Photocopy the Net Worth and Cash Flow worksheets and add columns to suit your needs, or use those worksheets as a model and create your own. From today’s vantage point, project your net worth and net income at the various stages that are most important to you (such as when the children are in college or upon retirement), inserting the numbers that seem reasonably appropriate. The idea is to determine how your financial picture will look at each stage if you stay on your current course, and to determine whether there could be a shortfall. As before, don’t worry about shortfalls. This book will help you overcome them to accomplish your needs and desires.