PACK-Teen Treatment Protocol

Mary Nord Cook

In an era of ever-decreasing inpatient and partial hospitalization stays, coupled with shrinking community resources, increasing numbers of patients need intensive outpatient behavioral health services that are readily accessible, convenient, efficacious, and cost-effective. There is a significant need for clinic-ready, manualized treatments for diagnostically complex, treatment-refractory youngsters, who present with a range of emotional and behavioral disturbances. A manualized Intensive Outpatient Program (IOP) was developed at Children’s Hospital Colorado (CHCO) in January 2006, to serve a broad and diffuse patient population, aged 7–18 years old, referred on the basis of clinical acuity rather than primary diagnosis. To ensure standardization of service delivery and enable program dissemination, the written materials were deliberately evolved to be explicit and readily followed. To the best of our knowledge, no other published, manualized programs are available that target a broad and diverse patient population referred based on acuity, symptom severity, treatment refractoriness, and level of functional impairment, rather than diagnosis. Chapter 4 describes the parent training component of the adolescent or teen treatment protocols that served the families of patients 12–18 years old. The child treatment protocols, targeting 7–12 year olds, and their families, were previously published in 2012.

Keywords

Treatment refractory; comorbid; diagnostically diffuse; parents; families; children; adolescents; teens; Intensive Outpatient Program (IOP); cost effective; efficacious; manualized; evidence-based; standardized

Established Parent Introductions and Check-Ins

Each Parenting Approaches for Challenging Kids (PACK)-Teen session follows a similar pattern and routine. Ask established or returning parents to remind the group of their first name and the name of their adolescent, who is enrolled in the program. After their first week, ask parents to check-in briefly regarding the past week, or interim period, since the last session. Cue them to relate one example of a “victory” (required) during which they used a new skill during a parent–teen interaction, in support of their self-identified individual or family treatment goals. They may additionally relate an instance of a “challenge” (optional), describing an experience during which they or their teen attempted to use a new skill or complete the “family homework,” but struggled and felt their effort was only partially successful or had outright failed. The point should be repeatedly reiterated so that we can learn from victories or successes and challenges or failures. All efforts and experiences are fodder for personal and family growth, if appropriately examined, discussed, and understood.

Workshop Guidelines

Following introductions briefly go over the group guidelines, inviting established or returning parents to assist with the process. Use of the word “rules” is avoided because it tends to invite resistance—even among adults. Guidelines include the following: punctuality is required, pagers and cell phones must be turned off, and of course, confidentiality is required. During the discussion of confidentiality, point out the few exceptions to confidentiality, which relate to client safety (e.g., suicidality, homicidality, abuse). Make the point, that part of maintaining confidentiality means that while they are enrolled in the treatment program, they and their teens should refrain from developing personal relationships that transpire outside of group sessions. This point should be made explicitly and despite doing so, many adolescent patients may still covertly develop friendships and even romantic connections, while in program, that sometimes become inappropriate and distracting. Many teens referred to such programs struggle with maintaining balanced and healthy interpersonal boundaries and often rush relationships, in a desperate effort to make connections with peers and feel liked and accepted. Therapists can’t control whether or not this happens, but they certainly can and should make the point explicitly, to both parents and teens, that personal communications with group peers, outside of sessions, is contraindicated, at least while in treatment. The guidelines should be mentioned at the start of each group session. Without this practice of routinely reminding the group of expectations every visit, inevitably parents will violate group guidelines, which may take the form of forgetting to turn off electronics, coming late, or leaving early.

New Parent Introductions and Check-Ins

After established or returning parents have introduced themselves, and “checked in,” go around the room and ask new parents or caregivers to identify themselves by first name; mention their adolescent’s name, sex, and age; and then comment on first one strength, talent, or positive attribute of their teen, followed by one challenging trait or behavior pattern, for which they are seeking help and guidance. Parents of adolescents with histories of emotional and behavioral problems are often surprised and ill-prepared to be queried about and report upon their teen’s strengths. Many in our programs have endorsed that the inquiry during the check-in and introduction process is the first time they recall having been asked about positive qualities their teens possess, in a long line of involvement with behavioral health providers and services. They find it refreshing but are often taken aback.

Once all new parents have had an opportunity to share one strength and challenge pertaining to their teen, ask the returning parents whether or not the challenge mentioned resonates for them, in reference to their own families. Encourage at least one or two of the established group members to relate a commonality, tied to the challenges reported, with respect to their current or past experiences and concerns regarding their own teen. The terms “strength” and “challenge” are used as cues for new parent check-ins, inviting them to identify and comment on a more global attribute, quality, or trait of their teen. The terms “victory” and “challenge” are used to cue returning or established parents, thereby inviting them to relate specific instances of attempts to apply new skills or strategies.

By creating a highly structured format for the introductions and check-ins, as well as reminding parents at the start of each session of those explicit expectations, emphasizing the direction to share briefly, the stage is set to contain that phase, for the sake of ensuring adequate time for didactic discussion, skills training, and practice of skills. This predictable and structured format serves to proactively prevent inappropriate or excessively prolonged check-ins. Setting clear expectations and structuring the check-ins in advance, increases the odds that parents are mindful of time limits and follow specific workshop guidelines, rather than having to be interrupted or redirected, by group facilitators, after they’ve launched into potentially lengthy and counterproductive check-ins.

During the check-ins, it is important for the clinicians to refrain from problem solving immediately as parents share concerns; instead, it is better to simply note the concerns and tie them into later discussions and practice of skills. Nearly every issue or experience related by parents during check-ins may be used as an example during the didactic and skill-building portion of the workshops. In fact, using examples from check-ins for practice the same day or week increases the degree of relevance and engagement experienced by parents during skill-building exercises; therefore, if parents request immediate attention to concerns raised during check-ins, encourage them to remember their questions and use them for practice during the subsequent portion of the same session.

The separate weekly, individual therapy session provided to each family creates a forum for customized safety planning and problem solving around issues pertaining to specific youth, which may not have been adequately addressed during the group sessions. In addition, the third weekly session, which occurs if implementing the Intensive Outpatient Program (IOP) service delivery model, uses the media of art and music to reinforce concepts and rehearse skills, from the first two weekly, more structured, language-based sessions. This creative arts session additionally provides a forum for whole families to process their feelings and express themselves within a less structured intervention, using nonverbal modes of experience and learning.

New Parent Orientation

If using a “rolling” style of admission, new patients may be joining the workshop at any time, mixed together with “established” parents, who are returning after attending previous sessions. New parents should already have been oriented to the program content, format, and logistics, as part of a standard intake process that occurs prior to the first session, but inevitably they either claim to not have been oriented at all or to have forgotten some portions of their orientation. This has occurred frequently, at our site, despite the practice of routinely providing families with both verbal and written summaries detailing program components and expectations, during their intake.

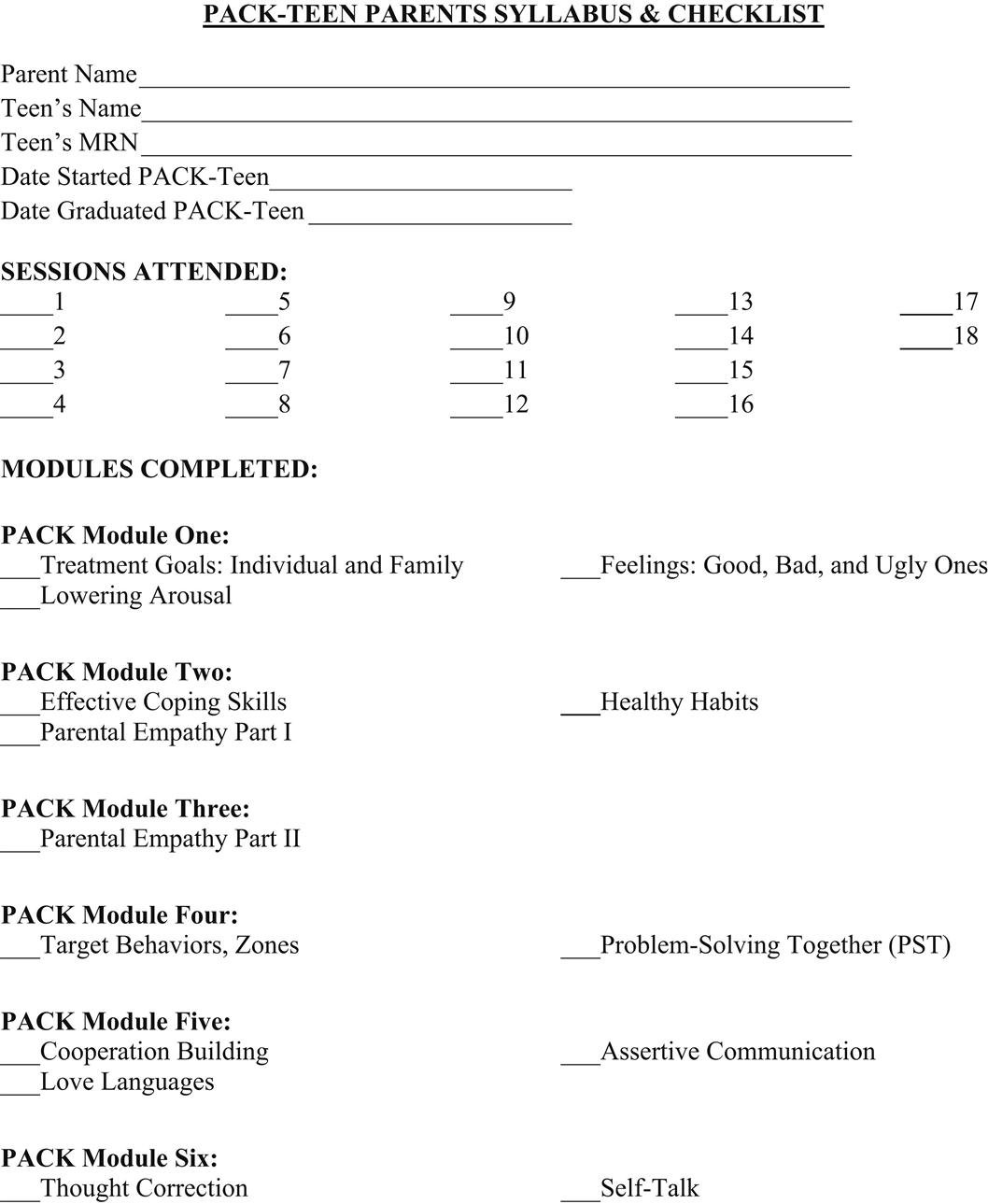

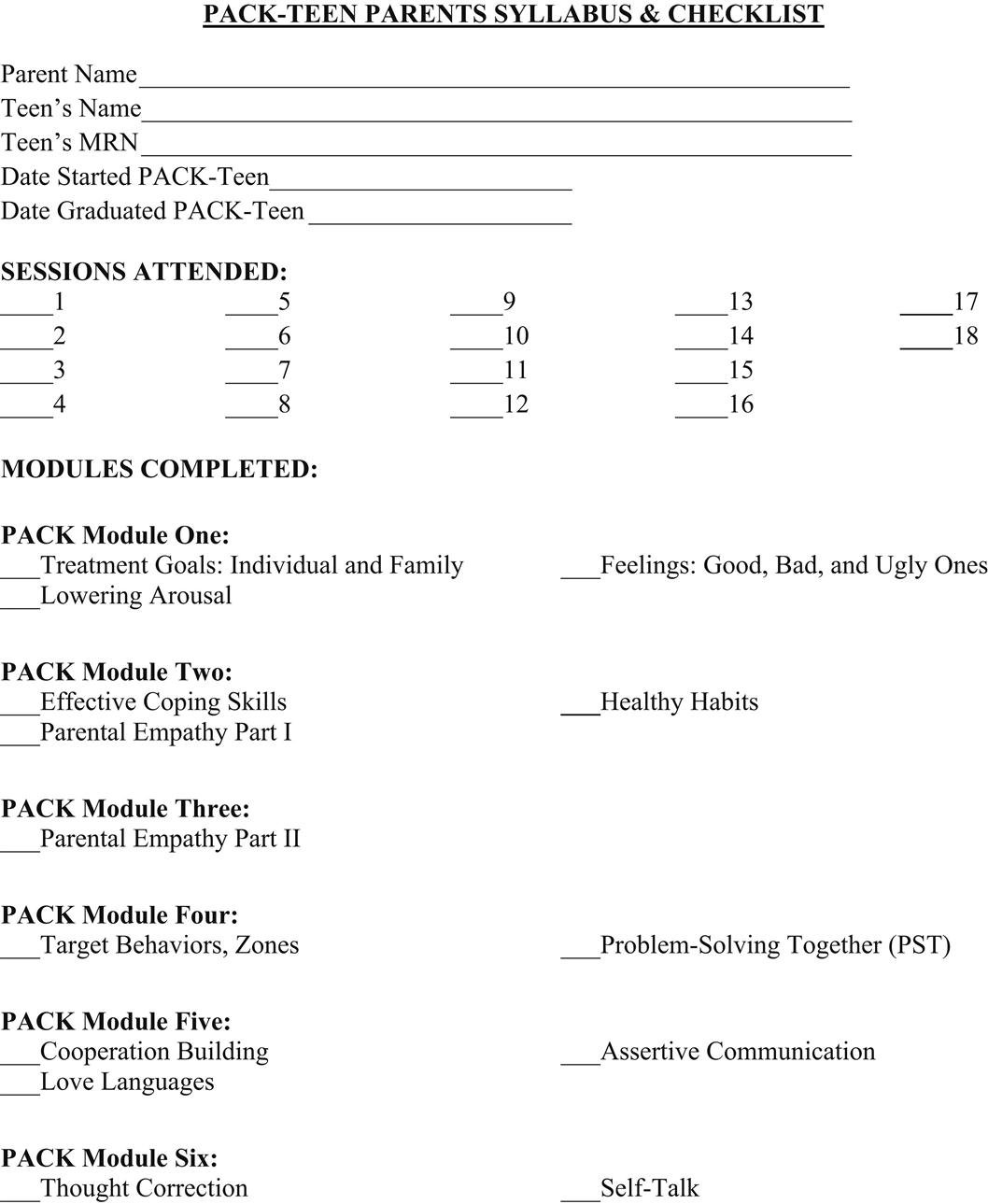

Provide a brief orientation of the program to new parents at the start of their first session, recruiting established or returning parents to assist with this process. A PACK-Teen program syllabus, copies of which are available in the book’s companion website, can be handed out to each new parent during their first session and reviewed, as a way of orienting to all program topics or skill sets. Additionally, the program’s format, including its different components, times, days, and locations, can be reviewed briefly by the therapists, assisted by returning parents. Details regarding options for the program format are provided in a separate section, titled “Format and Operations.”

Managing Parental Resistance

When parents first enroll in PACK IOP-Teen, it is common for them to focus on trying to change their adolescents; they often are eager to quash their teen’s maladaptive behaviors and engender in them more respectful, compliant, and deferential attitudes. Parents often endorse a desire to rid their teens of angry or distressed feelings and effect change in their adolescent’s overall attitudes, behavior patterns, and styles of relating; however, they usually will acknowledge that the more they have attempted to change or control their teen’s behavior, attitudes, or feelings, the more their youngsters have resisted.

You may want to ask parents, “What can you control?” in reference to effecting changes to their adolescent’s difficult behaviors. The answer, of course, is that the parents can control how they approach and respond, to their teen as well as the behavior they model. However, because families can be understood as “closed systems,” in which changing one element inevitably reverberates and effects change throughout the system, the power to modify their end of an interaction is often enough to effect the changes they desire in their adolescents. Parents often have commented to us, “It took me a little while…but we finally figured out the intervention is actually targeting us—not our teen!” Such a reflection is partly true, although it is our experience that the most effective and powerful way to effect change in an adolescent is to intervene simultaneously and equivalently with both the parents and their teen. A phrase that captures a principal tenet of PACK IOP-Teen places emphasis on an aspect of the parent–adolescent relationship over which the parents have full control and is as follows: “Model the behavior you want to see.”

Parents who are newly admitted to a program like this are often, “at the end of their rope” and commonly lament, “We’ve tried everything! Nothing works!” Exhausted and stressed parents of teens often feel as though they have failed and are incompetent. They often feel guilty, embarrassed, and helpless, a mindset commonly associated with a psychological defensive posture which manifests in the form of devaluing or negating others. That is, because it is so uncomfortable to feel as though one is incompetent, especially at the highly valued role of parent, parents who are struggling might be inclined to devalue and criticize clinicians and programs attempting to help. The underlying assumption, which is probably mostly an unconscious one, is that “Look, if I’m feeling incompetent then everyone must be incompetent. There is no solution or effective method—otherwise, I would have identified it by now.”

However, typically, their past failed efforts were focused mostly or exclusively on the teen, without sufficient attention to the contexts and systems surrounding the teen, by far the most important of which is the family, particularly the parents. The critical shift of paradigms that must occur, for meaningful family system changes to occur is the notion that parents can be powerful change agents in relation to their teen’s attitudes and behaviors. However, that is only the case if parents focus their efforts on optimizing their own attitudes and behaviors, including that which they model, along with the patterns by which they approach and respond to their teen. You might point out that most families already have much of what they need to emotionally support one another—but those resources just need to be discovered and cultivated. Essentially, most families already possess a set of “ruby slippers.” They are often simply unaware or at a loss as to how to operate them.

The experience parents often relate of encountering increasing levels of resistance as they have escalated their efforts to change or control their teen’s behavior, feelings, or attitudes, can be understood by considering humanistic theory as formulated by Carl Rogers (1961), who espoused that humans are most able to change, once they feel unconditionally accepted by others, and ultimately themselves. He stated, “The curious paradox is that when I accept myself just as I am, then {and only then} I can change” (p. 17). Humanistic theory serves as a fundamental tenet for Parent Effectiveness Training, a parent training program focused on fostering a sense of unconditional positive regard through empathic communication between parents and children (Gordon, 2000). A similar philosophy or formula for psychological healing is encouraged in the PACK IOP-Teen program, aka, “If you accept teens as they are … then they will change.” Such a suggestion often feels counterintuitive to most parents, who might initially respond with skepticism or resistance. Established parents, who’ve already recently experienced the benefits of empathic communication, can often assist in helping overcome the resistance and skepticism that may be held and espoused by new parents.

Workshop Format, Past Topic Review, Family Homework

Once orientation, introductions, check-ins have been completed, write the current session’s overarching topic on a dry erase board, and delineate specific time allocations for each component. It is helpful to give a mini-review (no more than 10 minutes) of what was discussed in the previous session, prior to launching into new material. The clinicians should invite returning members to assist in this process as a way of engaging them, assessing their degree of retention and also reinforcing previously taught constructs. If using a rolling style of admission, newly joined members can be reassured by the therapists that they will receive exposure to the briefly reviewed topic, in much greater depth when their cycle through the program predictably rotates back to that particular module.

After briefly recapping the previous sessions’ topic or skill set, begin that day’s discussion, using an interactive, experiential, and psycho-educational style. The basic sequence of interventions, for each module includes psycho-education, using an interactive format, introduction of new topics and skills, modeling of new skills and then provision of an opportunity for parents to rehearse them. The parents and teens will later join, to rehearse skills together and then families are assigned additional practice exercises, to perform at home, in between sessions. All modules contain homework assignments for families; worksheets related to homework are given to parents (and teens) at the end of group sessions; these sometimes involve activities or parenting interventions and other times paper-and-pen exercises.

“What About My Teen?” Examples

After every major topic or skill set, it is advisable to pause and invite the group to share and discuss examples from their own lives that relate to the topic covered in the current module. Encourage the parents to share either relevant victories or challenges; either type of scenario can provide teachable moments.

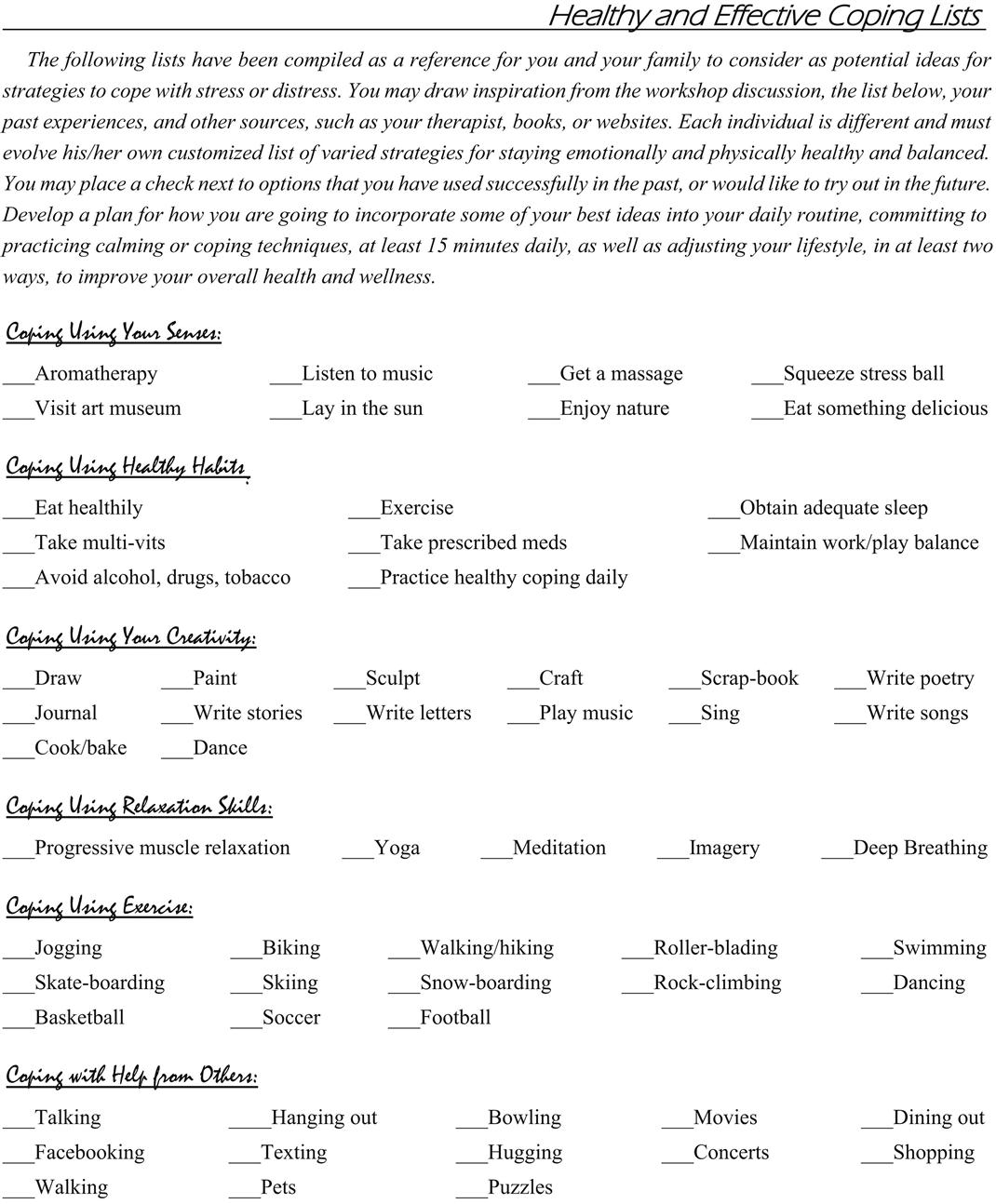

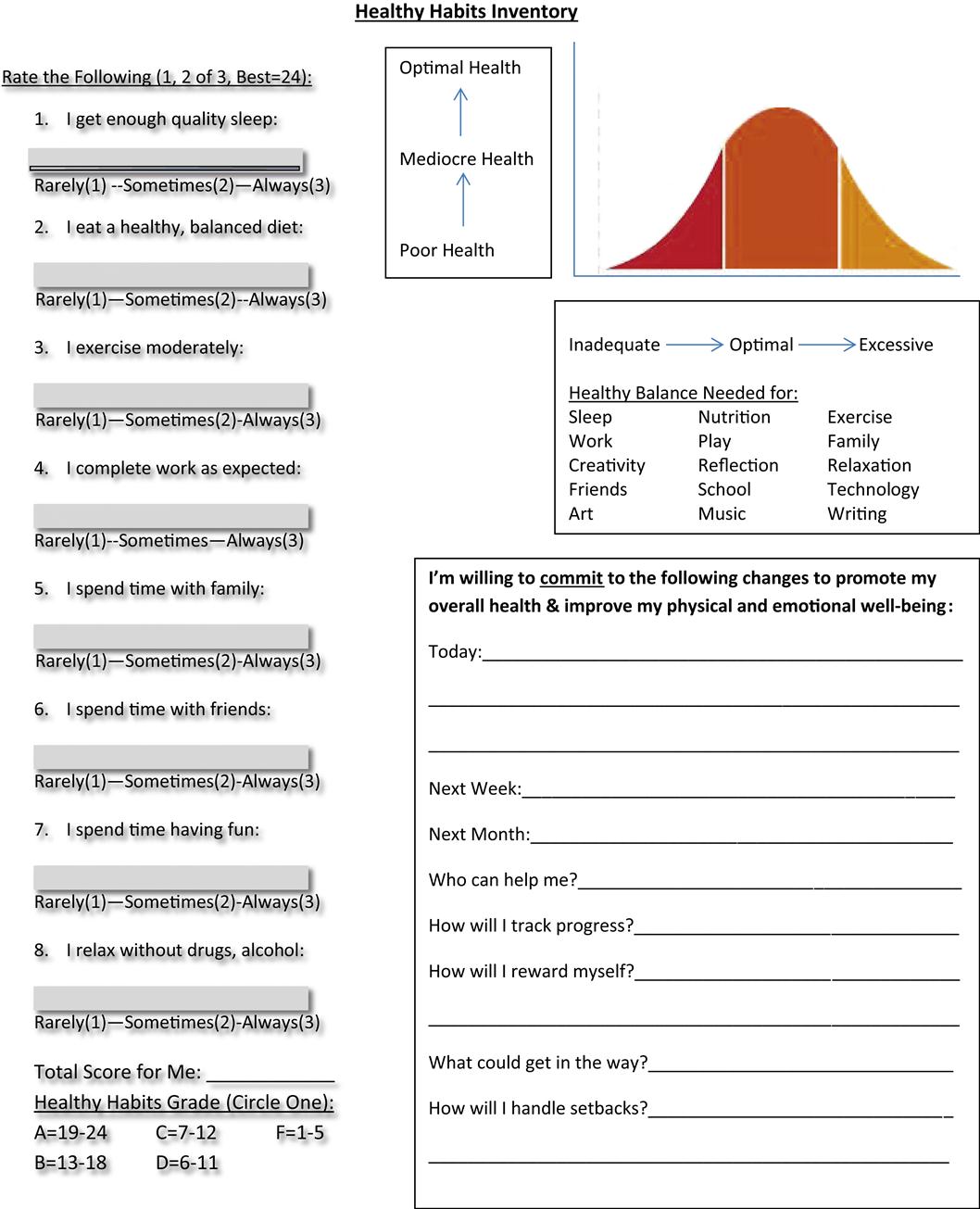

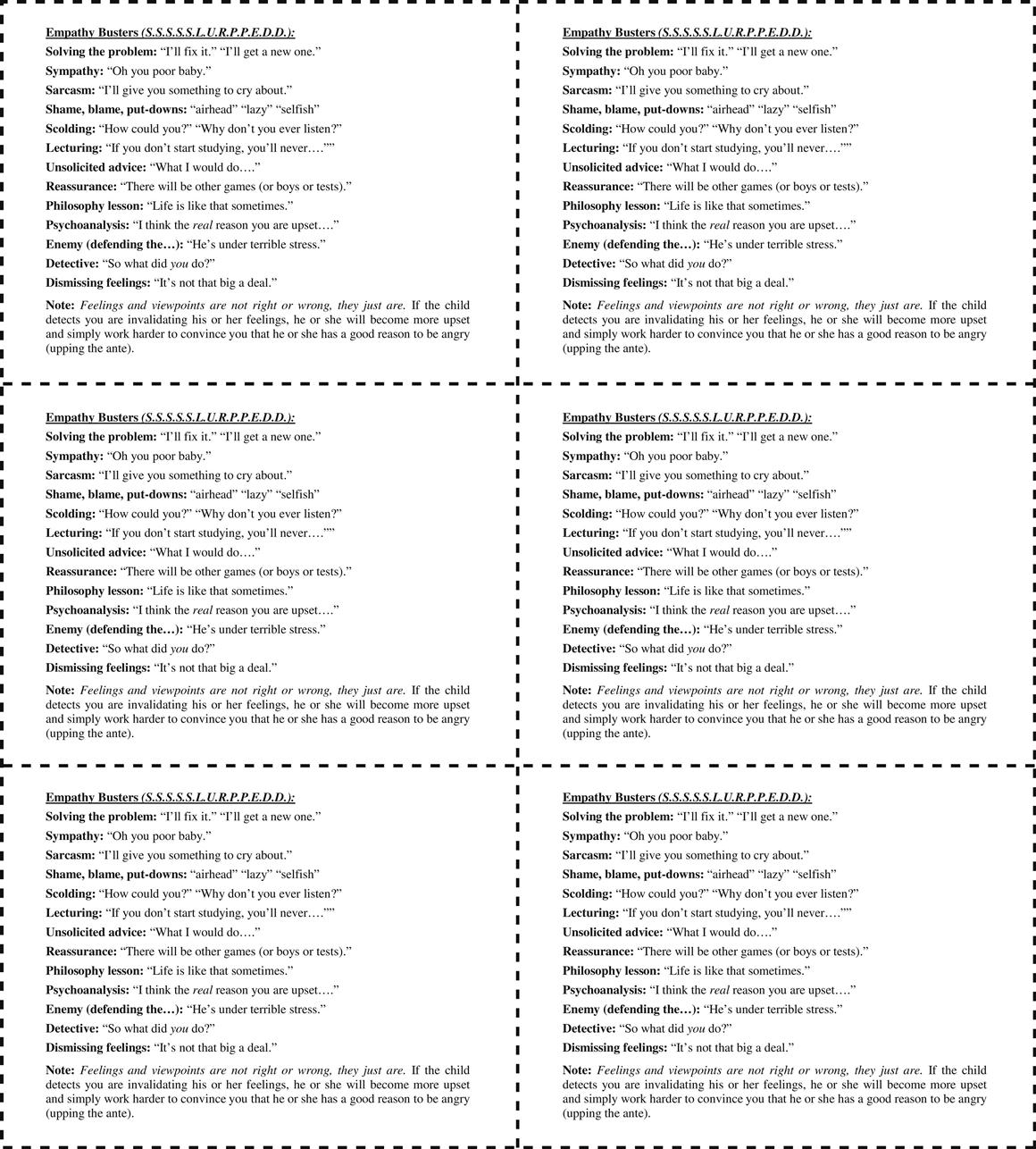

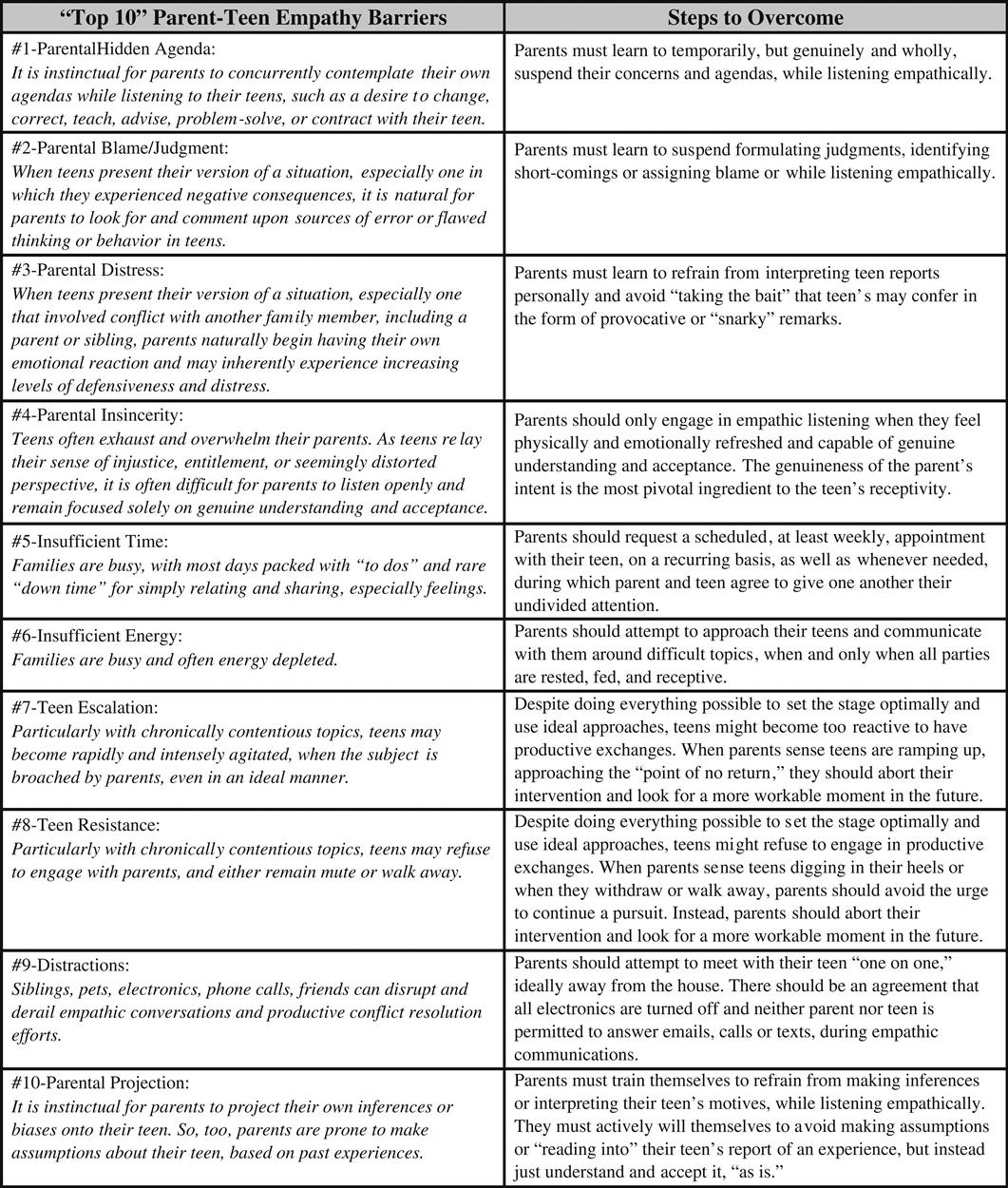

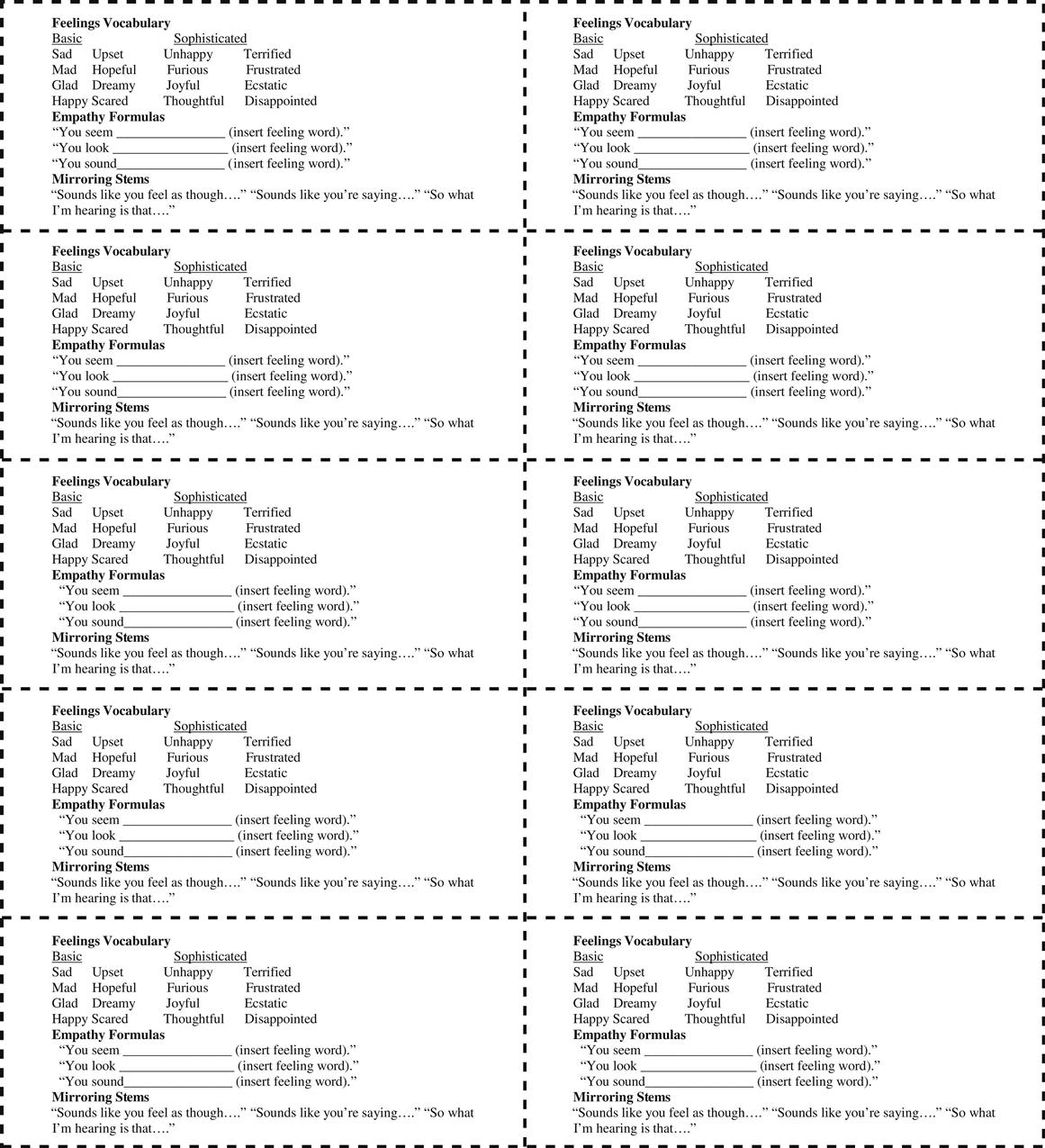

Handouts and “Business Cards”

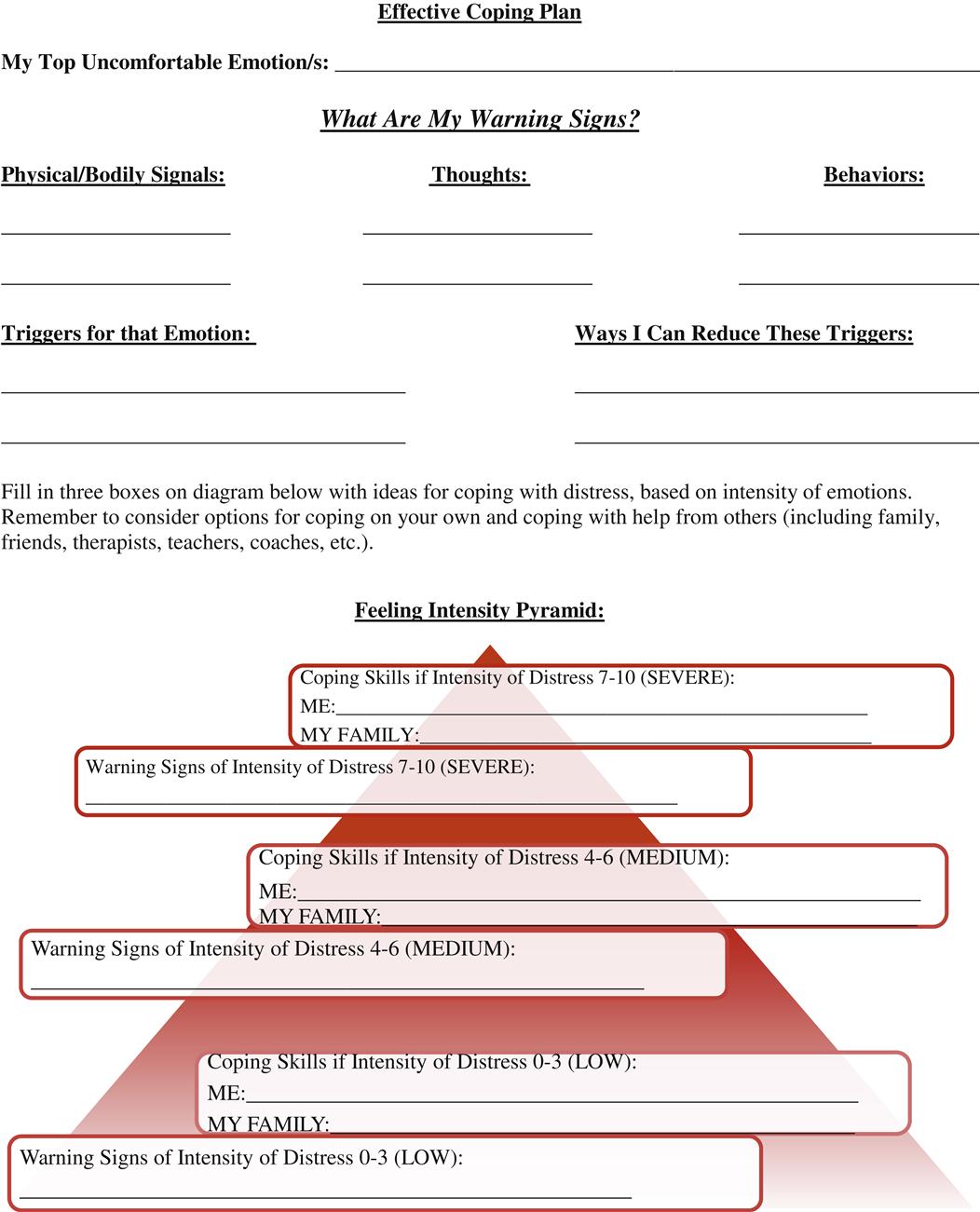

All of the sessions have corresponding handouts, available in the book’s companion website that can be given to the parents to review information covered during the group, either during the session, or at its close. Provide parents with these handouts as the related material is covered during the session, rather than in advance. In some cases, modules have associated worksheets that are intended for teens and parents to complete during the session. If workbooks have not been assembled by the clinicians in advance, advise the parents to keep their handouts together, in a safe place at home. Encourage them to maintain all handouts in a protective folder, or notebook, for future reference. Most modules also contain “business cards” reviewing material as well, which may be cut out, and provided to parents during the workshop to serve as a reminder. Laminating the cards elevates the level of preciousness of the cards and in our experience, increases the likelihood the cards will be kept and safeguarded for future reference. The parents may also be given copies of the “business cards” to keep, to tuck in their wallets and save for future reference.

Alternatively, all handouts and worksheets, except those required for homework in between sessions, can be preprinted and assembled into workbooks. These workbooks can be handed out to parents on their first day, but should be maintained by the clinicians, when not in use. They should be given out, when needed, during the workshop, but collected and held by the therapists in between groups. Otherwise, parents inevitably forget to bring them to sessions, or become distracted by them during group, sometimes flipping through them, even when they are not being referenced. The workbooks can be given to parents to keep, at the point of graduation. For convenience and to facilitate flexible use, all handouts are available digitally as separate documents, in the book’s companion website.

Introductions, Check-Ins, and Orientation Summary Outline

• Copies of parent handouts or workbooks

• Established Parent Introductions and Check-Ins

• Have the introduction and check-in format for new versus established parents written on the board.

• Go around the room and have each established parent take turns doing as follows:

– Ask each parent to identify themselves by first name.

– Ask each parent to mention their teen’s first name.

– Ask each new parent to mention one “victory” or success (required) and “challenge (optional),” from past week, related to their teen.

– Ask one or two returning or established parents to share commonalities pertaining to the teen challenges related by the new parents.

– If there are new parents, invite each established parent to help in orienting the new parents to the workshop format and guidelines.

– Established parents may check-in regarding their family progress, including approaches they tried which were effective thus far.

• Workshop consistently starts on time and finishes on time, punctuality required, leaving early or stepping out of workshop during session, not allowed.

• Confidentiality required, “What is said in here, stays in here,” playfully termed the “Vegas Rule.”

• Exceptions are safety issues (suicidality, homicidality, violence, abuse/neglect).

• Part of maintaining confidentiality includes refraining from communicating with group peers, outside of sessions, while enrolled in the program.

• All cell phones, pagers, electronics of any kind must be turned off during group.

• New Parent Introductions and Check-Ins

• Have the introduction and check-in format written on the board.

• Take turns having each parent introduce themselves and check-in as follows:

– Ask each parent to identify themselves by first name.

– Ask each new parent to mention one positive feature or strength of their adolescent and mention one “challenging behavior” they’d like to focus on.

• If new parents present, provide brief overview of what to expect from program, review PACK-Teen Syllabus, format for IOP program (three sessions weekly, describe how sessions vary from one another, etc.).

Handouts/Business Cards

Module 1-PACK-Teen Handout #1

PACK-Teen Module 1

Introductions and Guidelines

Begin Module 1 of the PACK-Teen program with a brief orientation if there are new members, introductions, “check-ins,” and a review of workshop guidelines, as detailed in the PACK-Teen Introductions, Check-Ins, and Orientation section. Follow the same basic routine at the start of each session. After introductions and “check-ins” are completed, mention the overarching topic of the current session, and write the schedule for the day on a dry erase board, with time allocations specified for each section. If there are new parents, provide them with copies of the program syllabus, and take a few minutes to review it, including briefly highlighting the topics or skill sets to be covered, throughout the program. For subsequent sessions, review these elements as needed for new members, including providing them with copies of the program syllabus, along with recruiting established parents to welcome and briefly orient new ones.

Review

Once introductions have been made, guidelines have been reviewed, and the current session’s topic mentioned, conduct a brief review of material from the previous session for no more than 10 minutes. Recruit returning parents to assist with this process.

Treatment Goals: Individual and Family

Throughout the program, there is an emphasis on clearly and concisely articulating primary treatment goals, for each individual, and their family. Likewise, both teens and parents are repeatedly encouraged to focus on their own role in improving family cohesion and functioning. Participants are routinely invited to contemplate goals they can realize and behavior changes they can personally implement. Parents are reminded to “Model the behavior you want to see” and that “If you accept teens as they are … then they will change.” It is common for both parents and teens to initially present with a defensive posture, in a blaming mode and the more the facilitators and their peers can shift them away from that position, the more open, flexible, and workable they become.

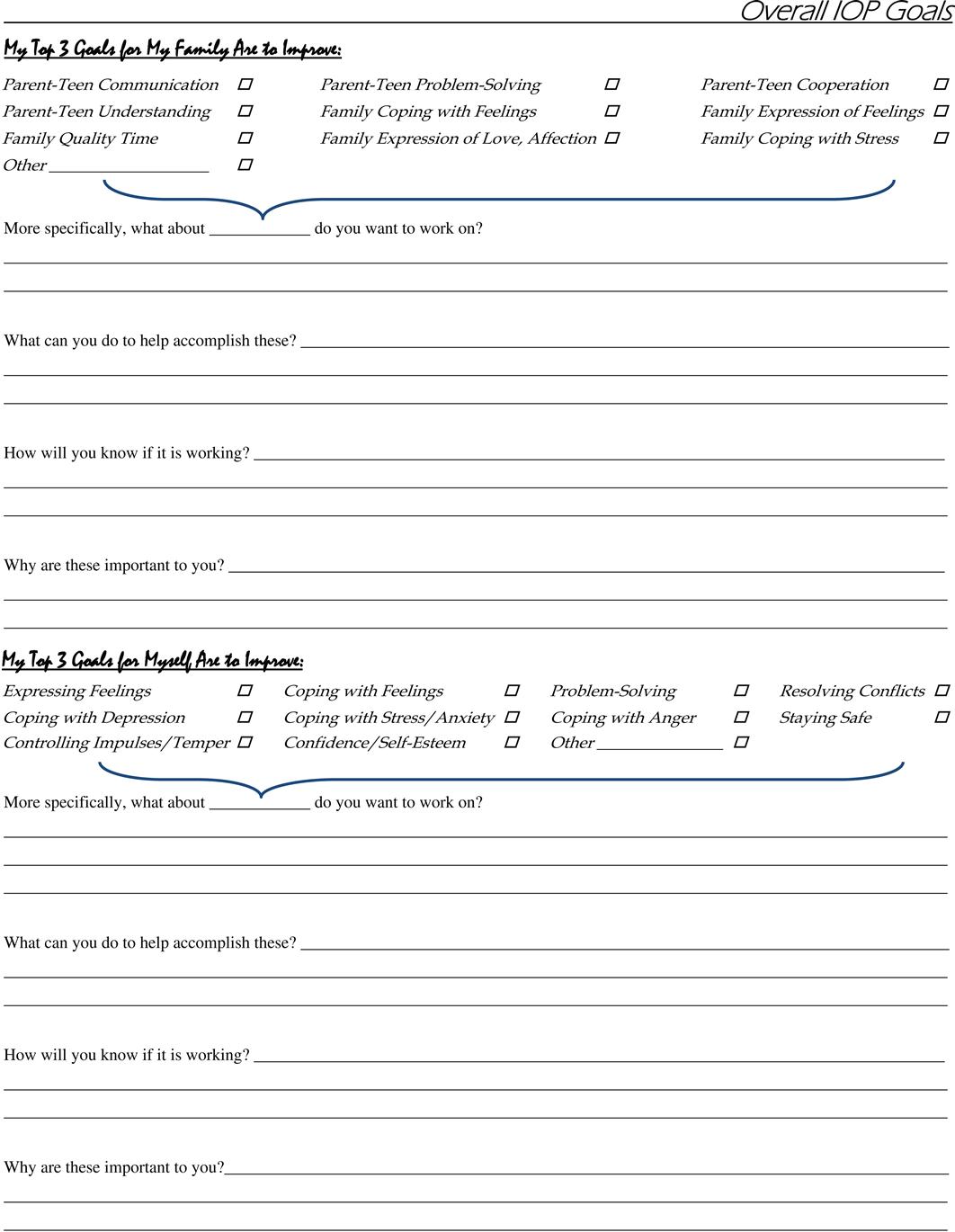

Ask parents to identify both an individual and family goal, during their first session, which is connected to the topics or skill sets covered in the program. When the expectation of formulating goals which are highly relevant and specific to the program is not made clear, it is very common for parents to identify treatment goals that are irrelevant, unrealistic, or vague, such as “I want to be a better parent,” or “I’d like my teen to move out.” A goals worksheet should be provided to new group members, at the end of their first session. They should be advised to further contemplate and write out their individual and family goals at home, prior to the next session. The worksheet contains several explicit directions and cues, which help parents focus on goals that are relevant, measurable, and realistic.

Other parents in the group and therapists may assist new parents with formulating and potentially reframing, specific treatment goals, if needed. As new parents share their experiences and reasons for entering the program, they can usually be readily guided to formulate specific treatment goals, which tend to flow naturally from their past experiences, including both challenges and victories. Additionally, the parents are expected to formulate and relay to their group, their ideas and plans for achieving their self-identified individual and family treatment goals.

During subsequent sessions, as part of routine check-ins, invite parents to discuss their progress in relation to each of these goals. Returning parents should have completed a goals worksheet, that they may be cued to reference, throughout the program, during “check-ins.” The parents are repeatedly urged to identify and comment on their own strengths and challenges, as well as their teens’, throughout the program, which may impact goal attainment, positively or adversely. Treatment goals can be established during Module 1 or the parent’s first session if using a “rolling” style of admission, but are typically dynamic and evolve throughout the course of the program, as each family masters various skill sets and achieves behavioral and relationship targets.

Feelings: Good, Bad, and Ugly Ones

Feelings Overview

Remind the parents that a primary goal of the program is to arm them with knowledge and tools in support of modeling, teaching, and reinforcing the psychosocial skills, on which the teens are being coached, with a goal of skills mastery for entire families. To that end, they will be acquainted with similar kinds of materials and urged to perform practice exercises, in parallel to the domains covered by teens. To begin, the most fundamental and universally relevant topic that merits their attention is the exploration of feelings or emotions, followed by strategies for effectively managing and coping with difficult or uncomfortable feeling states.

Ask the group whether they think emotions are important, and then have them indicate whose feelings they consider important. Typically, they will conclude that yes, feelings are important and that everyone’s feelings are important, at least to the person having them and those who care about that individual. Make the point that youngsters who struggle to regulate their emotions and control their impulses often come to view emotions, especially forms of anger, as “bad”; likewise, they often come to view themselves as “bad” for frequently expressing their emotions in an ineffective or even destructive manner. Because many of the youngsters enrolled in the Mastery of Psychosocial Skills (MaPS) IOP-Teen program have histories of being extremely reactive to emotions, and additionally often live in households wherein family members, including parents, may have modeled ineffective expression of emotions, learning to regulate and express emotions appropriately, is often a focus of treatment for many families.

Using a psycho-educational and Socratic style of teaching, ask questions about emotions, with the goal of helping the group recognize and acknowledge that experiencing a full range of emotions is perfectly normal and, in fact, unavoidable. Generate discussion to help the parents recognize that feelings are not good or bad—they just are—and that it is normal to experience anger, along with a full range of emotions, on a regular basis. Assist the group in recognizing that all feelings are part of the human experience and serve important functions.

Facilitate discussion regarding how emotions, even uncomfortable or difficult emotions, are often expected or understandable. Have the parents provide examples of when this might be the case. The goal of this discussion is to guide the group to recognize that their emotions serve a purpose and can often fuel positive, appropriate change. An example the parents might suggest is becoming angry in response to a bully mistreating their teen, propelling them to inform a counselor or administrator, for the sake of protecting their youngster and eliminating the bullying. An additional example might include instances during which citizens become outraged enough about an injustice that they are energized and mobilized to try to make things right and effect positive change. Depending on the examples the parents themselves are able to generate, you may want to contribute examples from history such as the actions of Rosa Parks, Mahatma Gandhi, and Martin Luther King, Jr.

While acknowledging that all feelings are normal and acceptable, in and of themselves, ask the group to discuss whether or not behavioral responses or reactions to emotions should be managed or limited. It is important to reiterate and reinforce the point, however, that unmanaged or inappropriate expression of emotions can be destructive, hurtful, and wrong.

Help the parents realize the point, that if feelings can be proactively monitored, labeled with words, discussed and processed, they can be understood and managed in healthy, adaptive ways, rather than destructively acted out. Ask the group if any of them are in the habit of monitoring, labeling, and verbally communicating their feelings with others, on a frequent basis. Most parents will indicate they have no such habit and little to no experience with monitoring, labeling, or conveying their feelings (aside from anger, perhaps, which they may have experience expressing aggressively). Recommend that parents target a goal of becoming expert at monitoring their own feelings; appropriately identifying and labeling them; and then expressing them in safe, nondestructive, nonhurtful ways. If they can become masterful in their ability to monitor, label, and express feelings, and routinely model effective mood regulation and interpersonal processing of emotions, they can support their teen’s progress in powerful ways. Remind the parents, “Teens don’t do what we say. … They do what we do!”

Ambivalence or Mixed Feelings

Facilitate discussion regarding the potential for experiencing two or more different conflicting emotions at the same time, by asking the group, “Is it possible to feel happy and sad at the same time?” Or “Is it possible to feel angry and hurt at the same time?” “Is it possible to be mad at someone and love them at the same time?” Ask whether more than one emotion or even seemingly conflicting emotions can be experienced simultaneously. Guide the group, through Socratic discussion, to recognize that emotions, like people and relationships, are complicated and that often individuals experience a variety of overlapping or even conflicting emotions simultaneously.

Foster additional discussion among the group regarding the phenomenon of ambivalence in relationships. Ask the parents to define the term ambivalence, cueing them to formulate a simple and concise definition, such as “a mix of bad and good,” or “mixed feelings.” Help the parents recognize and accept that everyone feels anger occasionally, even toward people they love very much. Generate discussion regarding the fact that all relationships and all people are a mix of good and bad. Make the point that just because people sometimes feel angry, including toward people they love, does not mean that they are bad people or that they do not love those at whom they have been angry. Inform the group that while experiencing intense emotions, all human beings may sometimes experience fleeting thoughts or wishes to harm others; as individuals age and mature, however, they learn to control their impulses and refrain from acting out aggressive thoughts or fantasies.

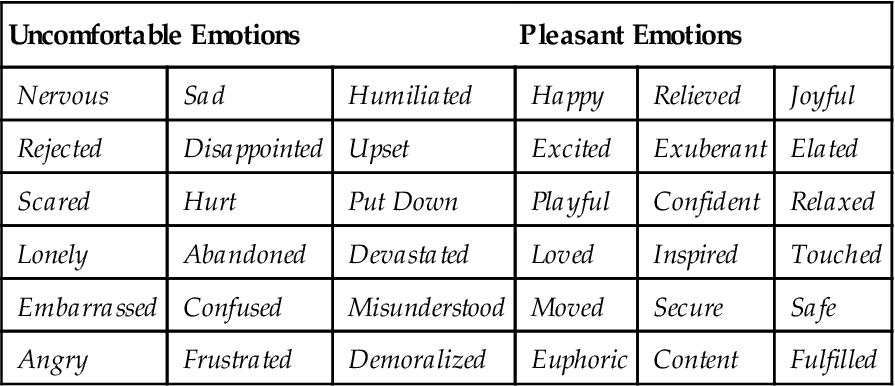

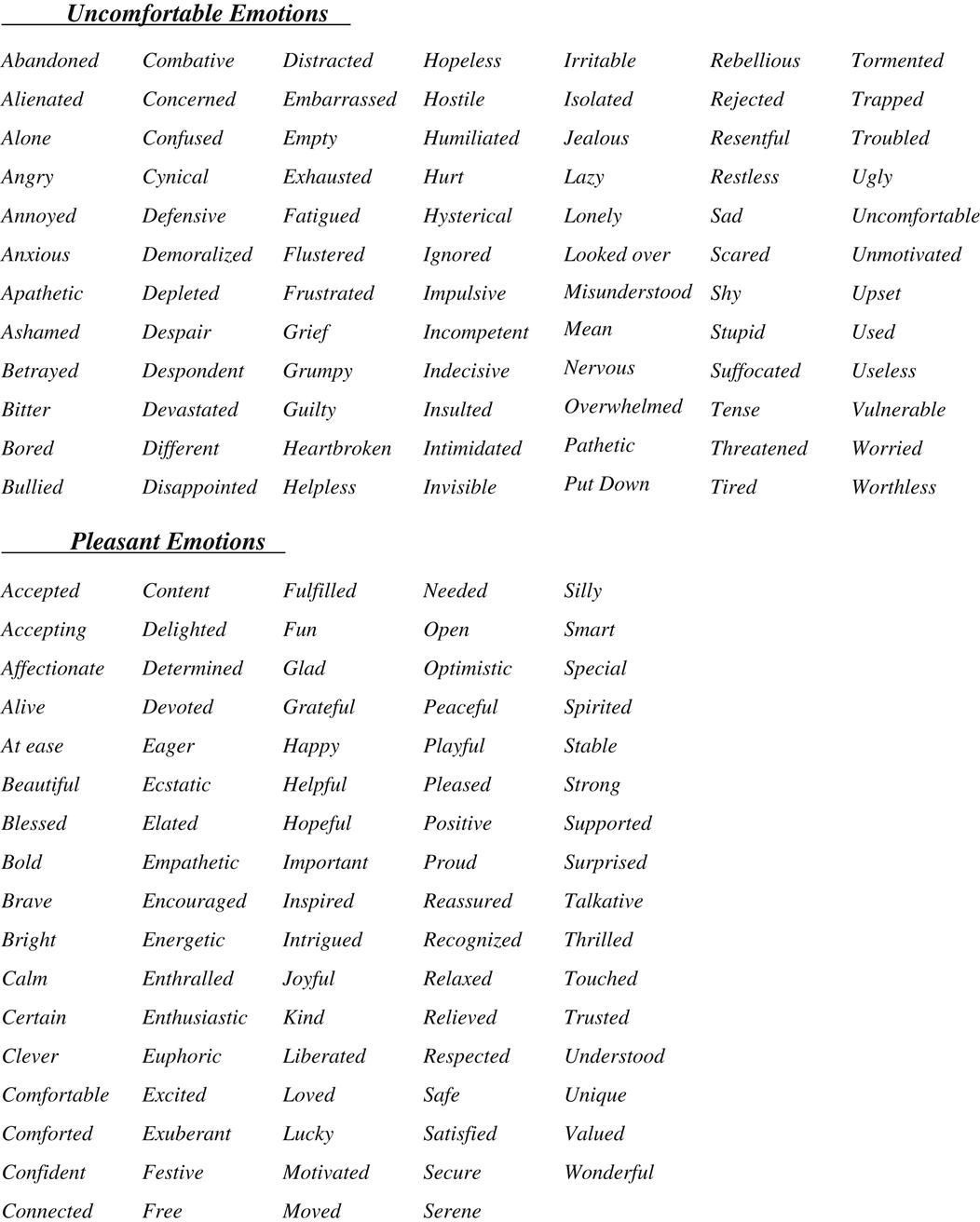

Feelings Vocabulary

Reference the earlier point, that when feelings are aptly labeled and discussed, they can be understood and effectively managed, and then invite the group to brainstorm a list of feeling words, which can be written on a dry erase board. Point out that parents have an opportunity to support their teens, by modeling the appropriate labeling and verbal expression of feelings. Let them know that youth who are prone to act out feelings, in unproductive or even destructive ways, are likely to have impoverished feelings vocabularies and maybe inadequate words to describe emotions. Again, remind the parents to distinguish feelings from physical or physiological states, such as “hyper,” “tired,” or “sore.” Additionally, help them discern the difference between feelings and thoughts, perceptions or judgments. For example, parents might endorse feeling as though “my family situation is hopeless,” when asked to reflect upon their feelings, although that statement is more representative of a thought or viewpoint, rather than indicative of an emotion or feeling state. The term “hopeless” by itself could represent a feeling state, but not when used as a descriptor referencing a family situation. It is helpful to have the caregivers initially focus on more positive or pleasant emotions and then switch and instead brainstorm another list comprised of more uncomfortable or unpleasant ones. The lists generated, which can be subsequently augmented via input from the therapists, might resemble those that follow:

| Uncomfortable Emotions | Pleasant Emotions | ||||

| Nervous | Sad | Humiliated | Happy | Relieved | Joyful |

| Rejected | Disappointed | Upset | Excited | Exuberant | Elated |

| Scared | Hurt | Put Down | Playful | Confident | Relaxed |

| Lonely | Abandoned | Devastated | Loved | Inspired | Touched |

| Embarrassed | Confused | Misunderstood | Moved | Secure | Safe |

| Angry | Frustrated | Demoralized | Euphoric | Content | Fulfilled |

Feeling Intensities

Have the group define intensity of feelings, which can be summarized as how little or how much you feel a feeling. Introduce the group to a scale, 0–10, and invite them to begin routinely noting their feelings, as well as assigning an intensity percentile.

Feelings Identification and Somatic Monitoring

Ask the parents to take turns identifying and relating their top two or three most uncomfortable, difficult, or distressing feelings and why they tend to cause problems in their lives. Encourage parents to identify warning signs for their emotions to include physiologic or bodily sensations as well as behavior changes or signs observable by others that indicate they are experiencing that particular emotion. Questions such as the following may be posed, to generate fruitful discussion:

How do you know you are experiencing that particular emotion?

How do you differentiate between feeling anxious versus feeling excited? (This is an example of a question used because the two feelings can physically be similar.)

Where in your body do you feel sadness (hurt, anger, etc.)?

How do you know you are becoming sad (hurt, angry, etc.)?

How would you describe the sensation of feeling sad (hurt, angry, etc.)?

What changes do you notice in your body, when you begin to feel sad (hurt, angry, etc.)?

Some examples of physical sensations or bodily effects noted, in association with various feelings include the following list:

Differentiate between physiological changes, such as the list above, versus behavioral warning signs which might include:

Facilitate discussion regarding the mind–body connection and help the group recognize regarding that there are physiological and bodily reactions that typically accompany all emotions, which can vary between individuals. Help the parents appreciate the value of identifying and attending to their bodily and behavioral warning signals, as early as possible, related to impending and escalating feeling states. Guide them to recognize the window of opportunity for self-soothing and coping that can be leveraged, before impulsive or harmful responses take over. Stimulate discussion with the group regarding the fact that many people find it difficult to deescalate their feelings and emotional reactions before they act out in some manner (again, the normalizing thing works really well). The goal is to learn to be proactive in identifying their own triggers and bodily signals and attenuate them early. As youngsters, along with their family members, become more tuned into their body signals, they can become better at taking care of themselves and dealing with their difficult emotions and the precipitants before they react impulsively in a manner they might regret. Again reiterate the point, that role-modeling healthy, pro-social behaviors, is often the powerful intervention parents can offer, in support of promoting emotional and behavioral health in their teens.

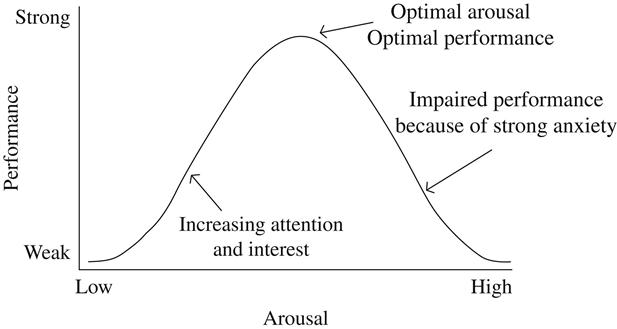

“Fight-or-Flight” Responsea

Generate discussion regarding the phenomenon of fight or flight. Encourage the parents to discuss what they know about the phenomenon of the fight-or-flight response and its origins.

The response consists of elevated arousal; increased heart rate, pulse, and breathing; increased strength in large skeletal muscles; and shifting into a highly instinctive, primitive state of mind (residing in the amgdala) that is bent on survival. Blood rushes to the major vital organs including the heart and lungs and to large skeletal muscles but notably away from the frontal lobes and rational decision-making parts of the brain (prefrontal cortex). The body is deliberately routing all resources, that is, blood flow to only the most vital, life-sustaining areas, of which the frontal lobes is not one.

Thus, a person experiencing a fight-or-flight response might feel dizzy, lightheaded, or confused. This response is a vestige of cavemen times, when early man had to be on guard and have the capacity to launch instantly into a physical state in which he was prepared to run away or fight when faced by that saber-toothed tiger or wooly mammoth. Ask the caregivers “What happens to people when they feel threatened or experience the fight-or-flight response?” and write down the ideas they generate on the dry erase board. The list may ultimately resemble the following:

Increased blood flow to large organs

Increased blood flow to large skeletal muscles

Facilitate discussion with the parents regarding the fact that arousal states (along with most emotional states)—as most people know and have experienced—are usually contagious. That, too, probably conferred early evolutionary advantage and so has been preserved in the species. It is rare, however, that the fight-or-flight response is apropos in modern society. People no longer face saber-toothed tigers or their modern-day equivalent. Discuss with parents, that, unfortunately, many youngsters are sensitized to enter this high-arousal state with minimal provocation. Their central nervous system wiring is functioning as though “short-circuited” and vulnerable to misfiring out of cue. In fact, there is a burgeoning body of literature, growing out of functional brain imaging studies, that is amassing evidence demonstrating a pattern of amygdala hyperactivation (emotion) coupled with prefrontal cortex and anterior cingulate (rational decision-making) hypoactivation, in adults and youngsters with anxiety and mood disorders (Wegbreit, Cushman, Puzia, et al., 2014). This robust scientific finding can help answer parental inquiry as to “Why is my child/teen struggling with emotional regulation?” Caregivers can likewise become sensitized to activation of their own threat or “fight-or-flight” response; especially if they have a long history of managing frequent escalations in their teens. In short, both their teens’ and their own arousal system can become “twitchy” and prone to firing and misfiring, akin to a “hair-pin” trigger.

Greene (2001) suggests that youth lose at least 30 IQ points when they become hyperaroused. They become more primitive and less capable of rational, logical, reasonable thought and conversation. If their parents likewise become hyperaroused, it as though gasoline has been poured on a fire, with both parties operating in a primitive, low-intellect, aggressive state. Ask the parents to reflect on an instance during which they entered this high-adrenaline state themselves. Encourage them to recollect the event in vivid detail and to share highlights with the workshop. Ask, “When highly aroused, what becomes of one’s ability to think clearly, to reason, to negotiate, or to problem-solve?” A hyperaroused person loses much of his or her capacity for rational thought along with 30 IQ points and instead becomes braced for action, either defending against or evading danger, a primitive being. Their higher-level brain functions shut down, leaving only the most primitive part of the brain engaged and functional. You might orient the group to reference the psychological mindset of a threatened individual as being controlled by their “savage” brain (amygdala) which is more powerful but much dumber than their “civilized” brain (frontal lobes or prefrontal cortex). The former is comprised purely of brute force, but lacking intellect and capacity for reason. The latter brain regions are admittedly less powerful, but much more intelligent, effective, sophisticated, and mature.

Threat in Eye of Beholder

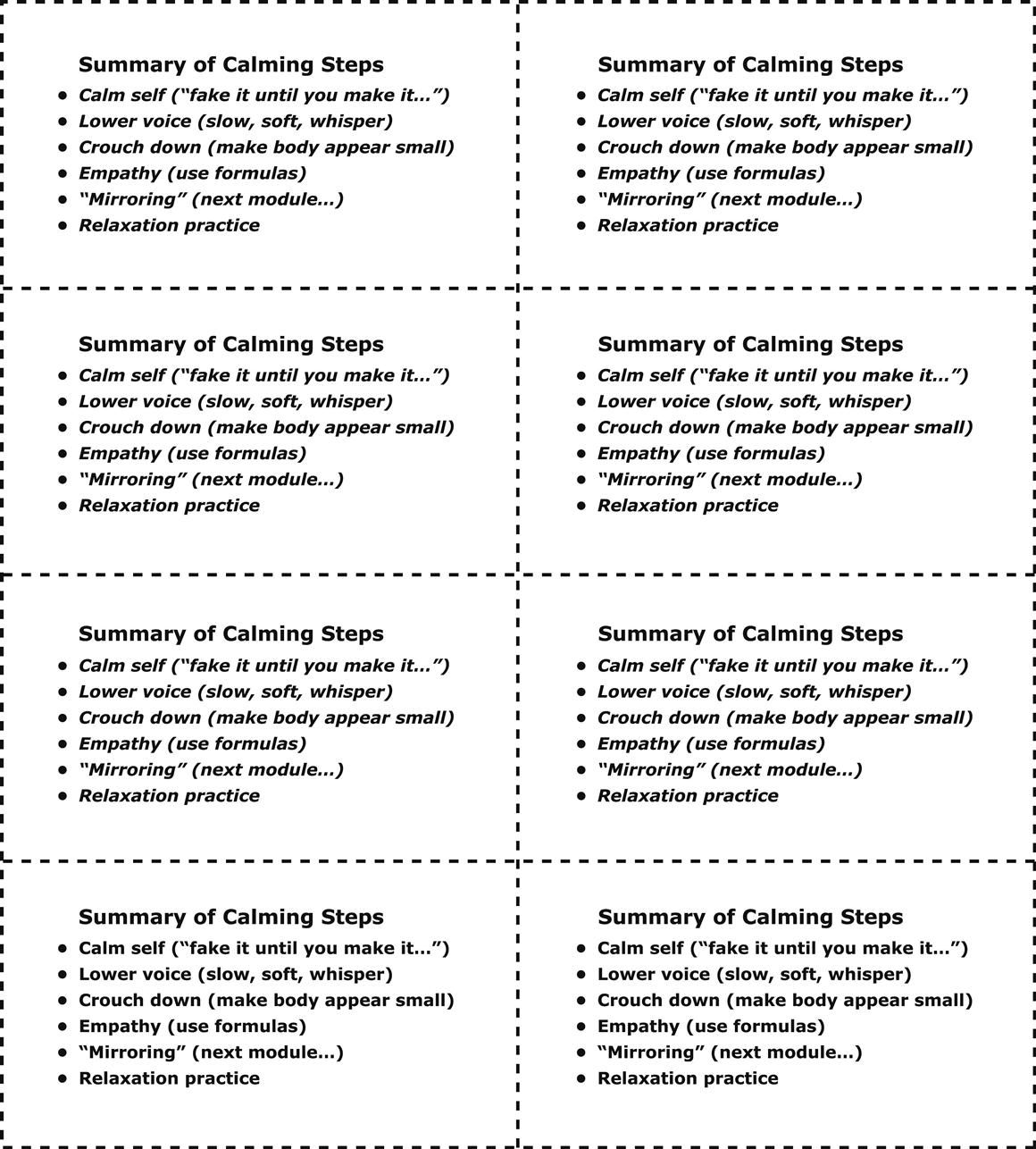

The point should be made that often adolescents who are becoming increasingly agitated genuinely feel threatened, even when others do not perceive an obvious or significant threat. Nonetheless, youth who are dysregulated tend to adopt a defensive or aggressive posture and behave as though they are under attack. Often, their brains inadvertently extrude large amounts of adrenaline, which heightens physiological arousal and in turn activates a mindset of defensiveness or aggression. Parents and other adults who are attempting to deescalate such a teen or prevent an escalation can behave in a manner that makes them unlikely to be perceived as a threat. Essentially, parents can present themselves as soft, vulnerable, and allied with the teen, causing the teen to deescalate more readily and become increasingly open, flexible, and cooperative. “Business cards” summarizing the steps for lowering arousal can be handed out now or at sessions’ end. These are available at the end of the bulleted outline for this module, as well as in the Therapist’s Toolbox on the book’s companion website.

Lowering Arousal

Contagiousness of Feelings

Suggest to parents that the plan for the remainder of the session is to focus on exploring techniques for coping with heightened arousal states in youngsters. However, prior to learning to cope with their teen’s heightened states of arousal, parents must become skilled at lowering and controlling their own arousal and behavioral responses to distress. Facilitate a discussion regarding the contagious nature of arousal and of feelings in general. It is easy and natural to laugh and joke when in the midst of playful, jovial company. Likewise, when in the presence of individuals who are agitated, irritable, angry, furious, or out of control, it is hard not to be affected and to avoid reacting in concert. This natural tendency is amplified in instances of parents witnessing their children experiencing and expressing intense feelings. Furthermore, if parents have teens who have been impulsive, dysregulated, and prone to explosive and aggressive outbursts, they may have become highly “sensitized” to their youngster’s emotional reactivity. Essentially, they may have heightened “anticipatory” anxiety in response to their teen’s upset and both parent and teen may be wired to escalate especially rapidly, with minimal triggers, as a programmed reaction to one another’s cues and provocative behaviors or remarks.

Cue discussion around the typical sequence of events and interactional patterns that occur between any two people, who are at odds, when one or both of them is upset, angry, frustrated, anxious, or experiencing some other negative emotion or mix of feelings. Inevitably, the communication degenerates and becomes not only unproductive, but often hurtful or even menacing. No conflict or problem can be addressed in a creative, collaborative and productive manner unless both parties are totally or at least mostly calm, open, and receptive. The rule of thumb needs to be that one should only confront a conflict when calm. There is a vast body of literature, encompassing a broad range of patient populations and treatment options that demonstrates that “Expressed Emotion,” or aggressive, critical, and hostile communication, negatively correlated with outcomes. In other words, emotionally charged relational patterns make patients do worse and confer increased risk of poor outcomes, whereas the absence of expressed negative emotions promotes treatment progress and protects against relapse (Han & Shaffer, 2014; Miklowitz et al., 2009).

Enmeshment

Highlight the fact that some parents are overly emotionally connected to their own adolescents, sometimes even to an unhealthy, extreme degree. This dynamic, termed enmeshment, results in a tendency for the identities and feelings of parents and their teens to fuse. Short of being enmeshed, many parents are naturally extremely tuned in to their youngster’s affective states. Some parents note each facial grimace, frown, furrowed brow, evil eye, and fist of fury. Because of this strong emotional attunement parents have with their teens, parents often assume and begin directly experiencing similar feeling states when in their midst. This applies especially when youngsters are distressed or highly agitated. It is hard for parents to tolerate witnessing their adolescents in distress because they, too, feel it deeply and feel obligated to do whatever they can to assuage their teen’s painful feelings.

Interrupting Cycles of Arousal Escalation

Ask parents to reflect upon and share specific experiences along these lines. They may recall how unbearable it was to observe their adolescents in psychic pain. If a youngster is angry, especially if his or her anger is directed toward the parent, the feelings between the two tend to fuse. The parent–teen dyad of the reciprocal cycle of anger tends to fuel itself like gasoline poured on a flame. The teen’s escalation leads to the parent’s escalation, which leads to further teen escalation, which leads to further parent escalation, and so on and so forth. Ask the group, “How can parents interrupt the cycle? How can you resist these natural, instinctual tendencies for your feelings to fuse with those of your teens?” This reaction is hard-wired, a vestige of early man; clearly, it once conferred evolutionary advantage to have been preserved all these years. Educate parents that they can actually resist this tendency and reverse nature, at least within themselves.

Share with the group that mental health providers routinely train themselves to step back, disconnect, and safeguard against assuming the emotional states of their patients. When a client becomes agitated or despondent, it is not that the therapist becomes cold and does not care; however, to be empathic and helpful to their clients, therapists must retain a reasonable level of affective control within themselves. If clients shout or cry, therapists know better than to follow suit. It would be ridiculous and also render the therapist incapable of helping and stabilizing the client.

Through didactic discussion, help parents recognize the counterintuitive reality that a person is best able to understand, validate another’s feelings, and be supportive, if he or she can remain somewhat objective, rational, and calm. Encourage parents to try to understand and validate their adolescent’s feelings but to avoid taking them on as their own. Teach parents to emotionally disconnect a bit if their teens are overwhelmed so that they can adopt a reasonable approach that will be helpful and supportive.

Nonverbal Calming Techniques

At this point, move to fostering a discussion of nonverbal techniques or behaviors for lowering arousal. Have the parents brainstorm and see whether they can identify the following actions that are typically useful in this regard:

Controlling breathing (slow, deep, abdominal breaths)

Assuming a nonthreatening body posture (facing the person with palms showing and open).

In addition, parents can depict themselves as nonthreatening by crouching down and attempting to minimize their size while speaking softly and slowly. Sometimes whispering will distract and disarm youth who are becoming distressed. Whispering and calm behavior tend to be contagious in the same way that agitation can be contagious. Parents often admit that they struggle to control their own arousal when facing off with their distressed or agitated teen. They are encouraged to “fake it until they make it,” that is, to pretend to be calm and strive to act accordingly until they are genuinely able to remain relaxed, even if their teen is distressed. Parents will discover that if they master the ability to at least present outwardly as calm, they will ultimately achieve a state of genuine calmness. In other words, acting calmly lowers arousal within a person behaving as such and leads to actual calmness in self and others.

“Taming Bambi” Metaphor

Share with the group that forging trusting and empathic connections with adolescents is akin to “Taming Bambi.” Adolescents tend to be defensive and mistrustful in their baseline posture toward the world, especially adults and most particularly in reference to their parents. The level of reactivity and mistrust teen’s harbor often increases exponentially relative to the extent of a legacy of escalating parent–teen conflict and acting out behaviors, which tends to proceed and precipitate entry into treatment. Encourage parents to consider the steps necessary to build trust with a wild animal, especially one prone to flightiness, and exaggerated startle response, such as a deer. Bambi is unlikely to initiate a connection with a human, and initially unlikely to accept attempts by a human to encroach. Humans must find ways to entice Bambi to venture closely and he will do so, only at his own pace, on his own terms. One false or sudden move by the human will send Bambi running rapidly for the hills, and if the breach in trust is too great, he might never return.

Parents must tread ever so delicately and ensure they are offering something that is especially incentivizing to their teens, to facilitate overcoming their natural instinct to flee. If parents attempt to forge relations and communications with teens in an overly aggressive or abrupt fashion, they may burn bridges beyond repair. They must outreach teens gingerly, mindful of the reactivity and flightiness to which they are prone, putting out crumbs delicately and then backing off sufficiently, such that their easily triggered teens can slowly but surely accrue comfort and trust, at a pace they control. In the likely event, in the case of a teen presenting for psychiatric treatment, that there has been intense and chronic parent–teen conflict and patterns of hostile communication, the parent is at an even greater disadvantage, where they are essentially starting from a deficit position, in building trust with their teen. This situation would be akin to a human attempting to encroach upon and make contact with a Bambi who had been treated aggressively by a human in the past, or specifically that very person now attempting to mend the bond between parent and deer (or teen).

“What About My Teen?” Examples

After covering each major topic, it is worthwhile for the facilitators to pause and invite some brief discussion regarding specific examples or applications of the material or skills covered as they relate to the teen for who they are attending treatment. Invite parents and caregivers to share examples of actual experiences with their youngsters and take turns role-playing instances of conflict while attempting to lower their own arousal as well as their teens’.

Feelings Triggers

Invite the group to recall examples of past experiences involving uncomfortable feelings and elaborate upon the circumstances under which those emotions were elicited. As individual parents share examples, inevitably their peers will identify and point out parallels from their own lives. Encourage the caregivers to especially reflect on what kinds of events set them off. Through didactic discussion, make the point that every individual will perceive the same situation differently and that different things make different people angry. It is very common for adolescents to identify interpersonal stressors as their most common and intense trigger for intense distress. Teens especially are prone to becoming overly dependent upon validation from peers for self-worth, as well as prone to failing to preserve their own definition of self as separate and distinct from others. Hence loss of friends or romantic break ups can trigger catastrophic reactions in adolescents who are left feeling empty, worthless, and devastated. Similarly, teens with ill-defined identities are likewise vulnerable to disintegrating emotionally in the face of intense conflict and verbal assaults, laden with derogatory labels and put downs, from family members, including parents and siblings. That finding is often associated with difficulties in maintaining healthy and balanced interpersonal boundaries, as detailed in the next section.

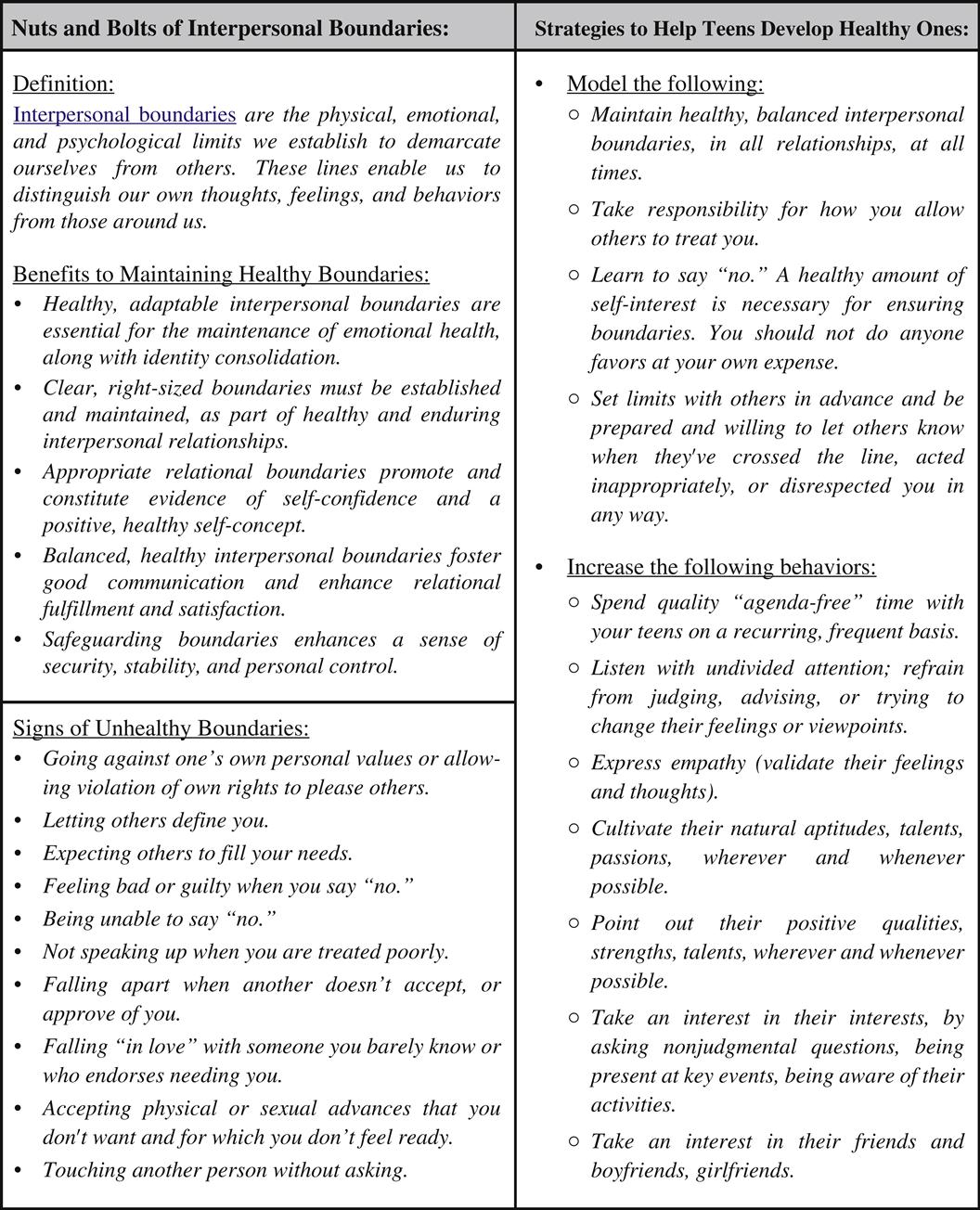

Interpersonal Boundaries

It is well established, that the most salient and critical developmental task of normal adolescence is identity consolidation, most especially in regards to defining oneself, in relation to others (Stiles & Raney, 2004). Typically developing teens shift their focus and prioritization of interpersonal relationships from parent–child to peer–peer (Flannery, Torquati, & Lindemeier, 1994). Within this context of heavy reliance upon peer acceptance and relationships, a fundamental interpersonal skill must be honed, pertaining to the capacity to healthily balance forging positive connections with peers with psychological autonomy (Scott & Dumas, 1995). The case has been made, via a significant body of literature that interpersonal boundaries that fall toward the extreme ends of the spectrum, ranging from extremely open to totally closed, are problematic and contribute to maladaptive social and psychological development, as well as fuel emotional and behavioral struggles (Peck, 1997).

Many teens, who have had difficulty making and keeping friends and/or have been embroiled in intense and chronic family conflicts, are relatively inept at managing interpersonal boundaries. They often exhibit patterns of rushing hastily into relationships at mock speed, in an intense, forceful, and emotionally dependent manner, characteristically revealing their whole life story at a first meeting, or instead refuse to open themselves up to engaging even superficially with peers.

Stimulate a discussion with the group about interpersonal boundaries. Invite them to define that term, as well as define the terms “identity formation” and “sense of self.” Ask them to ponder extremes of interpersonal styles, ranging from extreme openness, on the one hand, contrasted with extreme withdrawal and impenetrability, on the other. Ask them for examples of experiences wherein they observed interpersonal boundaries that were too loose, or fluid. Guide them to recognize the pitfalls and dangers inherent in maintaining relationship boundaries that are too diffuse, whereby one individual loses their distinct identity or sense of self and instead merges or becomes “enmeshed” with another individual. Diffuse boundaries can be seen in any relationship including inside professional situations, families, friendships, and romances. Ask them to reflect upon experiences wherein they observed an unhealthy degree of interpersonal walling off or impenetrability and invite them to consider and discuss potential risks inherent to that extreme style of relating.

Facilitate discussion around the value of striking a balance between remaining separate and distinct, psychologically, from others, versus allowing one’s definition of self and self-worth to be utterly dependent on feedback from others. Provide psycho-education regarding what is known in reference to optimal adolescent psychological development and social success, that is, that flexible and balanced interpersonal boundaries promote well-being and healthy relationships. Make the point that the capacity to define oneself is in part contingent upon one’s capacity to form relationships with others, wherein a connection develops, but at the same time, both individuals retain their distinct and separate identities. Invite parents to share specific examples regarding interpersonal struggles they’ve witnessed in their adolescents and brainstorm options for promoting healthy and flexible interpersonal boundaries. Examples of parenting strategies for promoting appropriate interpersonal boundaries and consolidation of identity or sense of self in their teens include the following:

• Modeling flexible, healthy, and balanced interpersonal boundaries, in all relationships, at all times.

• Spending quality time with your teens on a recurring, frequent basis.

• Listening with undivided attention and refraining from judging, advising or trying to change their feelings or viewpoints.

• Expressing empathy (validating their feelings and thoughts).

• Cultivating their natural aptitudes, talents, passions, wherever and whenever possible.

• Pointing out their positive qualities, strengths, talents, wherever and whenever possible.

• Taking an interest in their interests, by asking questions, being present at key events, being aware of activities.

• Taking an interest in their friends and boyfriends/girlfriends.

“What About My Teen?”

After covering each major topic, it is worthwhile to pause and invite some brief discussion regarding specific examples or applications of the material or skills covered as related to the adolescent for whom the parents are attending treatment. The parents and caregivers might be asked to provide an example or two of instances during which they understood their teen’s unhealthy behavior to be the function of a mismatch between developmental level or capabilities and environmental demands.

Family Homework

As a homework assignment, ask the group to pay attention to their bodily signals of emotions and take note of their triggers and warning signs during the subsequent week. They should also be provided with the treatment goal and family crisis plan worksheets and directed to complete them, prior to the next session. Additionally, encourage the parents to schedule family meals, at least once weekly, where all members gather at a table and each person takes a turn, sharing the best and worst parts of their day to model and facilitate practice of conversation and listening skills.

Joint Session for Module 1

As described in detail, in the format and operations section, parents and teens are brought together, once a week, in reference to each Module set, for the sake of discussing and practicing the skill sets that were initially introduced and rehearsed separately. At the start of the “Joint” session for PACK-Teen and MaPS-Teen Module 1, hand out the “Family Strengths and Goals” interview worksheets, which were designed to promote further contemplation and discussion of each family’s strengths and goals. Teens are invited to “swap” parents with another teen and partner with parents, who are not their own. Teens take turns with parents; alternately interviewing one another, using the interview questions outlined in the “family strengths and goals” interviews, with slightly different versions available for parents versus teens. Handouts are available containing the interviews to cue the participants, as well as provide a mechanism for writing down answers, to serve as later reminders while reporting results. A slightly different version of the handout is available for teens to interview parents than the one intended for parents to interview teens.

Advise the teens and parents to jot down answers, as they move through the interview. Cue them to demonstrate exceptional listening skills, by maintaining consistent eye contact, staying focused, and tracking their partners’ responses closely. They are encouraged to demonstrate that they are interested in hearing what the speaker has to say by using facial expressions, body language, tone of voice, and responding empathically. After all parties have completed their interviews, cue the larger group to come back together and have the teens and parents take turns presenting the information gleaned from their interviews.

As the reporting wraps up, ask the group to reflect upon their thoughts, feelings, and observations related to the exercise and information shared. Facilitate discussion regarding common themes that emerged and invite comments regarding any insights that were derived or experienced as surprising. Also reflect upon the purpose of the exercise, including explaining the importance of identifying individual and family strengths. Often, individuals tend to focus on aspects of a relationship or situation that are not going the way they would like. Ironically, it is often more difficult and counterintuitive to consider and point out aspects that are going well. As they progress through treatment and beyond, encourage families to focus just as much on strengths and victories, as they do on challenges. Also explain the importance of setting individual and family goals, that are realistic and relevant, as well as formulating plans to achieve them. Encourage families to set aside some time periodically to discuss how they are doing with the fulfillment of their family goals. If they find that they aren’t progressing as they would like, encourage them to identify a different plan.

Read the excerpt from Michael Riera’s book aloud, as it appears on the parent handout during the final 5 minutes of the joint group session, before adjourning and dismissing the group.

PACK-Teen Module 1 Summary Outline

Materials needed

Established Parent Introductions and Check-Ins

• Have the introduction and check-in format for new versus established parents written on the board.

• Go around the room and have each established parent take turns doing the following:

• Ask each parent to identify themselves by first name.

• Ask each parent to mention their teen’s first name.

• Ask each new parent to mention one “victory” or success (required) and “challenge” (optional), from the past week, related to their teen.

• If there are new parents, invite each established parent to help in orienting the new parents to the workshop format and guidelines.

• Established parents may check in regarding their family progress, including approaches they tried which were effective thus far.

Workshop Guidelines

• Workshop consistently starts on time and finishes on time, punctuality required, leaving early or stepping out of workshop during session, not allowed.

• Confidentiality required, “What is said in here, stays in here,” playfully termed the “Vegas Rule.”

• Refrain from developing personal relationships with other patients while in program.

• Exceptions are safety issues (suicidality, homicidality, violence, abuse/neglect).

• All cell phones, pagers, electronics of any kind must be turned off during group.

New Parent Introductions and Check-Ins

• Have the introduction and check-in format written on the board.

• Take turns having each parent introduce themselves and check in as follows:

• Ask each parent to identify themselves by first name.

• Ask each new parent to mention one positive feature or strength of their adolescent and mention one “challenging behavior” they’d like to focus on.

• Ask established parents to relate commonalities noted during new parent check-ins.

New Parent Orientation

Review

Treatment Goals: Individual and Family

Feelings: Good, Bad, and Ugly

Feelings Overview

• Generate broad discussion of feelings.

• What are feelings? Are they important? Whose are important?

• What feelings “get them in trouble?”

• What is the purpose of feelings?

• Encourage the parents not to ignore their feelings, and remind them that emotions serve a purpose. Share that it does not make you a bad person if you have anger; it’s what you do with the feeling that counts.

• Ask the parents, “Is it ever a good thing to be angry about something?” May also provide the group with examples of anger that is put to good use. For example, a parent getting angry over how a bully is treating someone and deciding to tell the administrator so that it stops is a positive result of anger.

Ambivalence or Mixed Feelings

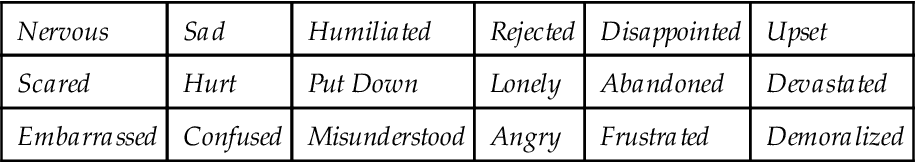

Feelings Vocabulary and Intensities

• Invite discussion and brainstorm regarding negative or uncomfortable feelings. Generate list on whiteboard such as the one that follows:

| Nervous | Sad | Humiliated | Rejected | Disappointed | Upset |

| Scared | Hurt | Put Down | Lonely | Abandoned | Devastated |

| Embarrassed | Confused | Misunderstood | Angry | Frustrated | Demoralized |

• Assist parents in distinguishing feelings from thoughts or perceptions/judgments.

• Have the group define intensity of feelings, which can be summarized as how little or how much you feel a feeling, introduce a rating scale, based on percentage 0–100.

• Ask, “Are emotions good or bad?”

• Help parents realize that emotions are not “good” or “bad,” they are natural and serve important functions.

• Discuss if behavioral responses to emotions can be “good” or “bad.”

• Ask, “Can more than one emotion or even seemingly conflicting emotions be experienced at the same time?”

• Discuss ambivalence and reiterate that this mixture of emotions is often the case.

Feeling Identification and Somatic Monitoring

• Invite the group to reflect upon and discuss the various bodily signals and sensations they have experienced, associated with various feelings.

• Where in your body do you feel sadness (hurt, anger, etc.)?

• How do you know you are becoming sad (hurt, angry, etc.)?

• How would you describe the sensation of feeling sad (hurt, angry, etc.)?

• What changes do you notice in your body, when you begin to feel sad (hurt, angry, etc.)?

• Choose two or three feelings as examples and generate lists on the whiteboard, as the parents share examples.

• Some examples of physical sensations noted, in association with various feelings include the following list:

• “I feel sick to my stomach.”

• Discuss mind–body connection and guide group to recognize the value of attending to early bodily signals, especially for anger.

“Fight-or-Flight” Response

• Generate discussion about the “fight-or-flight” response. Discuss its origin and purpose as well as the physiological or physical changes associated with it (turn off frontal lobes).

• Make a point about contagiousness of feelings and discuss the phenomenon of “sensitization” whereby escalation can become more automated, and more rapid, if hostile exchanges have become a pattern.

• Orient group to terms “Savage” brain (amygdala, brainstem) versus “Civilized” brain (prefrontal cortex, frontal lobes)—one all brute force, no intellect or reason—the other less powerful, but much, much more intelligent, effective, and mature!

Discuss Contagiousness of Feelings and Enmeshment

Discuss Cycles of Arousal Escalation

• When a defiant, defensive adolescent (or a teen with psychosocial impairments or difficult temperament) hears “No,” “You can’t,” or “You must” or feels boxed in or controlled, a power struggle or meltdown is imminent.

• Recognize that fear is usually under or behind anger. Anger and anxiety go together. Essentially, one might react with hostility when he or she feels threatened. The threat does not have to be rational or realistic; it’s the perception of threat that matters.

• When a teen or parent becomes “aroused” or feels threatened in some way, he or she experiences an adrenaline response “fight or flight”—accompanied by physical symptoms of arousal and/or anxiety, including increased heart rate, increased respiratory rate, dizziness, and lightheadedness. This is because blood rushes away from the brain to the large skeletal muscles, heart, and lungs.

• One’s capacity for rational thought disappears when one is furious and/or upset.

• When aroused, humans are evolutionally programmed to fight or run away. We tune out the sound of the human voice and instead tune in to the frequency of large predators or other threats. When angry, your teen literally cannot hear you.

• As a parent becomes aroused in response to the teen’s arousal (parent is emotionally connected to teen, and the teen knows how to push the parent’s buttons), the parent’s arousal only further fuels the teen’s arousal, resulting in a vicious cycle of escalating emotions. Because of this long-standing cycle, the parent and teen essentially are both sensitized or programmed to react automatically when faced with certain cues (e.g., “No,” “You can’t,” “You must”).

Discuss Nonverbal Techniques for Lowering Arousal

• Lower your own arousal—quiet your voice, control your breathing, use a gentle tone of voice, and assume a nonthreatening body posture (same techniques psychiatrists use with agitated patients).

• In other words, when you child goes up, you go down. Model the regulation of affect and appropriate expression of anger.

• Use relaxation training (hand out and discuss relaxation training scripts, located on the book’s companion website as PACK-Teen, Module 1, Handout 1).

Summary of Calming Steps

• The steps for calming down a distressed child can be summarized as follows:

• Calm yourself (“fake it until you make it”).

• Lower your voice (speak slowly and softly; whisper).

• Crouch down (make body appear small).

• Display empathy (use formulas).

• Use mirroring (covered in next module).

• “Business cards” outlining these calming steps are available digitally in the PACK-Teen Therapist’s Toolbox on the book’s companion website. These cards can be cut out and handed to parents to serve as reminders during the workshop as well as at home.

Review “Threat” (i.e., “Fight or Flight”) Response

“Taming Bambi” Metaphor

• Introduce the idea that empathically connecting with teens is akin to “Taming Bambi.”

• Teens must feel as though they control pace and manner.

• Parents should be mindful on offering incentives “crumbs” that are powerful, such that teens are compelled to approach.

• One false or sudden move experienced as threatening to teens, can send them running for the hills, so gentle and delicate approach, alternating with sufficient backing off, is key.

Feeling Triggers

Interpersonal Boundaries

• Facilitate discussion around the notion of interpersonal boundaries including inviting a definition of the term.

• Cue the group to reflect upon the value of striking a balance between remaining separate and distinct, psychologically, from others, versus allowing one’s definition of self and self-worth to be utterly dependent on feedback from others.

• Provide psycho-education regarding what is known in reference to optimal adolescent psychological development and social success, that is, that flexible and balanced interpersonal boundaries promote well-being and healthy relationships.

• Invite the group to share specific examples of interpersonal struggles they’ve witnessed in their adolescents.

• Brainstorm with the group options for promoting healthy and flexible interpersonal boundaries in their teens.

• Modeling flexible, healthy, and balanced interpersonal boundaries, in all relationships, at all times.

• Spending quality time, with your teens on a recurring, frequent basis.

• Listening with undivided attention and refraining from judging, advising or trying to change their feelings or viewpoints

• Expressing empathy (validating their feelings and thoughts)

• Cultivating their natural aptitudes, talents, passions, wherever and whenever possible

• Pointing out their positive qualities, strengths, talents, wherever and whenever possible

• Taking an interest in their interests, by asking questions, being present at key events, and aware of their activities

• Taking an interest in their friends and boyfriends, or girlfriends.

PACK-Teen Mantras

What About My Teen?” Examples

Family Homework

• As a homework assignment, ask the group to pay attention to their bodily signals of anger and take note of their anger triggers, during the subsequent week.

• The parents are encouraged to schedule family meals, at least weekly, where all members gather at a table and each person takes a turn, sharing the best and worst parts of their day, to model and facilitate practice, of conversation and listening skills.

Wrap Up and Answer Questions

Joint Session Ideas for Module 1

• Complete Family Strengths and Goals Interview:

• Teens “swap” parents and join with parents who are not their own.

• Both parties interview each other using the attached interview questions.

• Parents and teens report back to the group about what they learned about one another. Ask about thoughts and observations from the group.

• Facilitate discussion regarding common themes. Also discuss the purpose of the exercise. Explain the importance of being able to identify strengths.

• Encourage families to focus just as much on strengths as they do on challenges. Also explain importance of setting goals as well as having a plan to carry them out.

• Encourage families to set aside some time periodically in order to discuss how they are doing with fulfilling their family goals.

• Read excerpt from Michael Riera’s book aloud, as it appears in the parent handout, during last 5 minutes of session, before adjourning and dismissing the group.

Handouts/Business Cards

Module 1-PACK Parent Workbook Cover

Module 1-PACK-Teen Handout #1

Module 1-PACK-Teen Handout #2

Module 1-PACK-Teen Parent Handout #3

Module 1-PACK-Teen Parent Handout #4

Module 1-PACK-Teen Mantra Cards Therapist Tool #1

Module1-PACK-Teen Parent Handout #5

Family Strengths and Goals Interview: Parent Version

Directions: Pair with a teen from another family and alternate asking and answering questions with them, until the interviews have been completed. Write down answers as you go, and prepare to share the responses, with the group, when the interviews are done.

Parents Ask Teens (paired with teen from another family):

1. What is your favorite feature of your family?

2. What is something your parent does really well?

3. What works really well in your family?

4. What is something you wish you could change about your family?

5. What is something you wish you could change about yourself?

6. Describe a favorite memory of a time with your family.

7. Share three activities (you think your family would be willing to do), that you would like to do with your family.

8. What would you be willing to do, to improve your family relationships or help in achieving your family goals?

Module 1-PACK-Teen Parent Handout #6

Parenting Adolescents:

The following passage by author Michael Riera (2012) was excerpted with permission from Uncommon Sense for Parents with Teenagers, Third Edition:

Until this point, you have acted as a “manager” in your child’s life: arranging rides and doctor appointments, planning outside or weekend activities, helping with and checking on homework. You stay closely informed about school life and you are usually the first person your child seeks out with big questions. Suddenly, none of this is applicable. Without notification, and without consensus, you are fired from the role of manager. Now you must scramble and re-strategize; if you are to have meaningful influence in your teenager’s life through adolescence and beyond, then you must work your tail off to get rehired as a consultant.… As a consultant, you offer advice and give input about decisions when you are asked. Otherwise, you’ll lose your client. You don’t garner the automatic praise and admiration that you did earlier. And, when your client asks for advice, you need to make sure that she really wants it. Sometimes, more than anything else, she simply wants your reassurances that she’ll figure it out herself. Sometimes she will temporarily lose belief in herself and ask to borrow your belief in her for a short while. Offering advice is not helpful when the real problem is the teenager’s lost belief in herself. A rule of thumb is not to take your teenager’s request for advice too literally until the third time. Nobody wants a consultant who tries to take over the business. What you are doing is not doing—you are waiting, but not abandoning. As a consultant, you must also save your “power plays” for health and safety issues; everything else is negotiable on some level. Skipping a biology class is definitely not on a par with driving a car after drinking alcohol. Finally, at this stage in your relationship, you are no longer the focus of your child’s praise and admiration; rather, you are often the scapegoat for the confusion about what it is to be an adolescent. As a manager, you were quite content to take their feedback personally, as a reflection of you; as a consultant, you must learn to not take most of their feedback personally, since it is often more about them than about you.

PACK-Teen Module 2

Introductions, Check-Ins, Guidelines, and New Parent Orientation