Module 3-PACK-Teen Parent Handout #14

Family Empathy Interviews

Directions: Pair with a teen from another family and alternate asking and answering questions with them, until the interviews have been completed. Write down answers as you go, and prepare to share the responses with the group when the interviews are done.

Parents Ask Teens (paired with teen from another family):

1. What would you think, feel, and do, if your parents didn’t come home one night (and didn’t answer their cell phones)?

2. What is your greatest fear related to one or both of your parents?

3. What is your top wish for one or both of your parents?

4. What is something you regret saying or doing within your family?

5. If you could have a do-over, of # 4, what would you say or do instead?

PACK-Teen Module 4

To begin PACK-Teen Module 4, refer to the Introductions, Check-Ins, Guidelines, and Orientation section that can be found at the beginning of PACK-Teen Module 1.

“Win–Win” Conflict Resolution

Inform parents that a number of the nation’s experts on effective parenting, including Ross Greene, Thomas Gordon, and Sam Goldstein advocate for a collaborative problem-solving approach to parenting. Ross Greene has demonstrated that his program, aptly named Collaborative Problem Solving, effectively reduces aggression and explosive behavior in outpatient samples (Greene et al., 2004), as well as on acute psychiatric units (Greene & Ablon, 2006). Many parenting experts argue for efforts at “win–win” conflict resolution between parents and teens—a life skill that can serve teens well across settings and throughout their lifetimes. Many models for effective management of corporations likewise call for a “win–win” (Covey, 1989) philosophy of leadership. The point should be made, using a Socratic approach, that any outcome other than “win–win,” in the context of a relationship, especially one as important as that between parent and teen, constitutes a “lose.”

Discuss with the group that the premise of a collaborative problem-solving approach is for parents to project a spirit of cooperation and compromise. This approach involves expressing empathy, active listening, or mirroring, followed by problem solving around any issue, conflict, or problematic behavior. The message parents should strive to convey is, “Let’s work together to figure out a way to solve this dilemma so that we both get what we want.” This style of conflict resolution is the mainstay of customer service, well-run businesses, and family and couples therapy. Often, it is considered alternative and even radical by parents, but many experts argue and have demonstrated that it is a very effective approach to parenting, particularly in the case of oppositional teens. Win–win conflict resolution and collaborative problem solving builds relationships, enhances self-esteem, and fosters resiliency in youth. Adolescents in particular, as they navigate the psychological phase of development, often termed separation-individuation, are highly invested in being heard and inputting to decisions affecting them. If parents habitually engage in a collaborative discussion with their teens, rather than approaching them in a more dogmatic or directive fashion, they increase the odds of their teens responding cooperatively and flexibly. Additional benefits to this style of communication include strengthening those relationships and communication channels, building trust, and enhancing adolescent self-esteem.

Review with the group the typical sequence of events and interactional patterns that occur between any two people who are at odds, when one or both of them is upset. No conflict or problem can be addressed in a creative, collaborative, and productive manner unless both parties are totally or at least mostly calm, open, and receptive. What tends to happen, when an exchange around a conflict occurs in the face of heightened negative emotions in either party or both, is a sparring match. Essentially a verbal volley ensues, and as negative emotions intensify and defensiveness escalates, the tone and context become increasingly toxic and derogatory. Remind the group again of the rule of thumb that stipulates one should only attempt to tackle a conflict or problem when calm.

Parental Resistance

It has been common for parents to bristle and recoil at the recommendation that they adopt an empathic and collaborative approach to conflict resolution with their teens. They are inclined to perceive this approach as comparable to “giving in” or conceding in parent–teen power struggles. They sometimes recount childhood memories of having been raised via an authoritarian style of parenting where compliance, respect, and deference to parents were essentially demanded and where the potential or real consequences for disobedience were particularly grim and menacing, such that parental threats and intimidation powerfully influenced and controlled child behavior. Parents often ask, “Why can’t our kids just respect and listen to us, like we did with our parents?” They often express frustration and a sense of dismay and demoralization regarding their sense that youth of subsequent, successive generations have presented as increasingly “entitled,” “disrespectful,” and “spoiled.

You can offer feedback to the group and facilitate discussion regarding the gradual shift that has occurred in society in general, especially in professional environments during the past 50 years or so, which has paralleled the power and dynamic shift that has emerged in most modern American families. As delineated by Daniel Goleman (2005), in a series of books he authored on the modern-day construct of “Emotional Intelligence,” relating its applications across society as well as business environments, there has been a gradual morphing of culture and dynamics in professional settings from one that was rigidly hierarchical to one that is increasingly collaborative, embracing of diversity and team-oriented. The role and value of “emotional intelligence,” that is, social competency and skill in reading and reaching other people, has increasingly burgeoned as a set of occupational and leadership skills that are sought and considered essential to workplace success. In earlier decades, dating back prior to 1980, organizations tended to designate clear and supreme bosses who unilaterally made decisions and exercised supreme power and authority, without input or consent from subordinates, regarding the company’s mission, vision, and operations. In more recent decades, especially as technology has exponentially advanced and global reach has become the norm, successful enterprises have increasingly embraced a philosophy of worker empowerment and team collaboration as the most productive and optimal style of operating. Family dynamics and relational patterns, along with family role expectations and power differentials, have followed trends in American society and businesses in general, where all parties expect to have a voice and to have their views given due consideration. The goal of family (team) synergism is pursued, with the consolidation of input from varied and multiple parties considered exponentially more valuable than that of a few or of just one individual.

Setting the Stage for PSTc

Highlight with the group that problem solving is another skill set that is often deficient in many youth who struggle with anxiety, depression, dysregulated mood, or impaired impulse control. When agitated or upset, which such teens often are, they simply cannot think “outside the box.” They cannot think of multiple, creative options and solutions to any given dilemma and become “black and white” thinkers, when distressed. Hence, they are likely to resort to defiant, explosive behavior or other forms of “melting down.” Parents can help their teens build skills and—at the same time—increase cooperation, foster resiliency, and strengthen the parent–adolescent dyad by routinely employing this type of collaborative approach.

Encourage parents to recall the physiology and psychology of the “fight-or-flight” response. Point out that many youth who struggle with emotion regulation, depression, anxiety, or impulsivity are vulnerable to entering a state of fight of flight at the slightest provocation. They are “sensitized” (as are their parents many times) and tend to become hyperaroused quite readily in response to environmental cues. Remind parents that the first step toward calming their teen is learning to calm themselves down or, better yet, remaining calm in the first place. If they are to be effective, parents need to disconnect from their adolescent’s emotional and agitated response and remain objective and rational. Until such a skill is mastered, advise parents to at least “act as though” they are calm and deploy a body posture, facial expression, and tone of voice that is “matter of fact” and rather unemotional. They must train themselves to become impervious to the teen’s affective state if they are to calm their adolescent and effectively manage or, better yet, avert explosive behavior. They should be continuously mindful of the utility of refraining from interpreting their adolescent’s outburst personally and instead strive to understand the factors which precipitated it.

Reiterate the point that feelings are contagious. Although this is human nature, this tendency to assume the feeling state of those in our midst, especially family members, can be overcome with effort and practice. Parents can learn to will themselves to step back, think things through, and develop an effective strategy that has not been unduly influenced by strong negative affect, for intervening with their youngster. Help the parents recognize that when they remain calm, they maintain their capacity for rational, logical, and creative thinking. In addition, they are more likely to maintain their capacity for experiencing and expressing empathy, solving problems, and supporting their adolescent. They also are modeling the appropriate regulation of affect and impulse control for their teen. If parents can remain calm, they can then move to helping their teen lower his or her level of arousal.

Sometimes, if a parent and/or adolescent has become too escalated, a “time-out” or a “cooling-off” period is needed before a conflict should be addressed. Some youth become so agitated so quickly that they need some time by themselves before they are capable of responding in a productive way and accepting the supportive intervention of their parent. Ultimately, with practice, parents can learn to anticipate their teen’s temper outbursts and reverse their trajectory before they become full-blown. Likewise, adolescents can practice and master relaxation and calming techniques in their workshops. These skills ideally are frequently practiced by youth at home and modeled and reinforced by parents.

Lowering Arousal

Methods for lowering arousal were introduced in PACK-Teen Module 2 and can be reviewed again briefly with the group. Using a didactic style of teaching, invite the group to recall approaches for lowering arousal. In sum, one must use a calm, reassuring tone of voice and nonthreatening body posture. The most effective and relationship-building language-based technique for lowering arousal and defusing upset in youth—or anyone, for that matter—is the verbal expression of empathy, empathy, and more empathy. Mixing empathy with mirroring can go a long way toward helping youngsters feel as though their feelings and perspective are understood, validated, and respected.

Remind parents of the previously suggested guideline that they spend at least 3 minutes empathizing and listening, to their teen before they react or even begin to communicate their own agenda. During this 3-minute process, direct parents to refrain from adding any new or original ideas or feedback of their own to the discussion with their adolescent. Advise them simply to listen with undivided attention or, if they feel a verbal response is necessary, to use empathy statements or mirroring techniques. Their only mission is to focus completely on developing a deeper understanding of their teen’s feelings and perspective regarding the situation at hand.

Picking Your Battles

Ask the parents to generate a list of domains of conflict that they commonly encounter with their teens. Invite them to share examples of behaviors exhibited by their adolescents which they wish would stop, as well as cite behaviors which they would like to see their teens start. When families initially enter treatment, especially at an intensive outpatient level, they are often demoralized and exasperated, having developed long-standing patterns of conflict-ridden, adversarial interactions. Parents often develop patterns of intense emotional reactivity, wherein they tend to exhibit equivalently strong, negative reactions to all instances of negative behavior, failing to moderate their responses, relative to the magnitude of the behavioral infraction. In other words, caregivers and their adolescents are prone to becoming ensconced in a chronic “battle of wills,” in which nearly every issue can become fodder for intense conflict and debate, sometimes out of proportion to the issue.

“Zoning” Behaviors

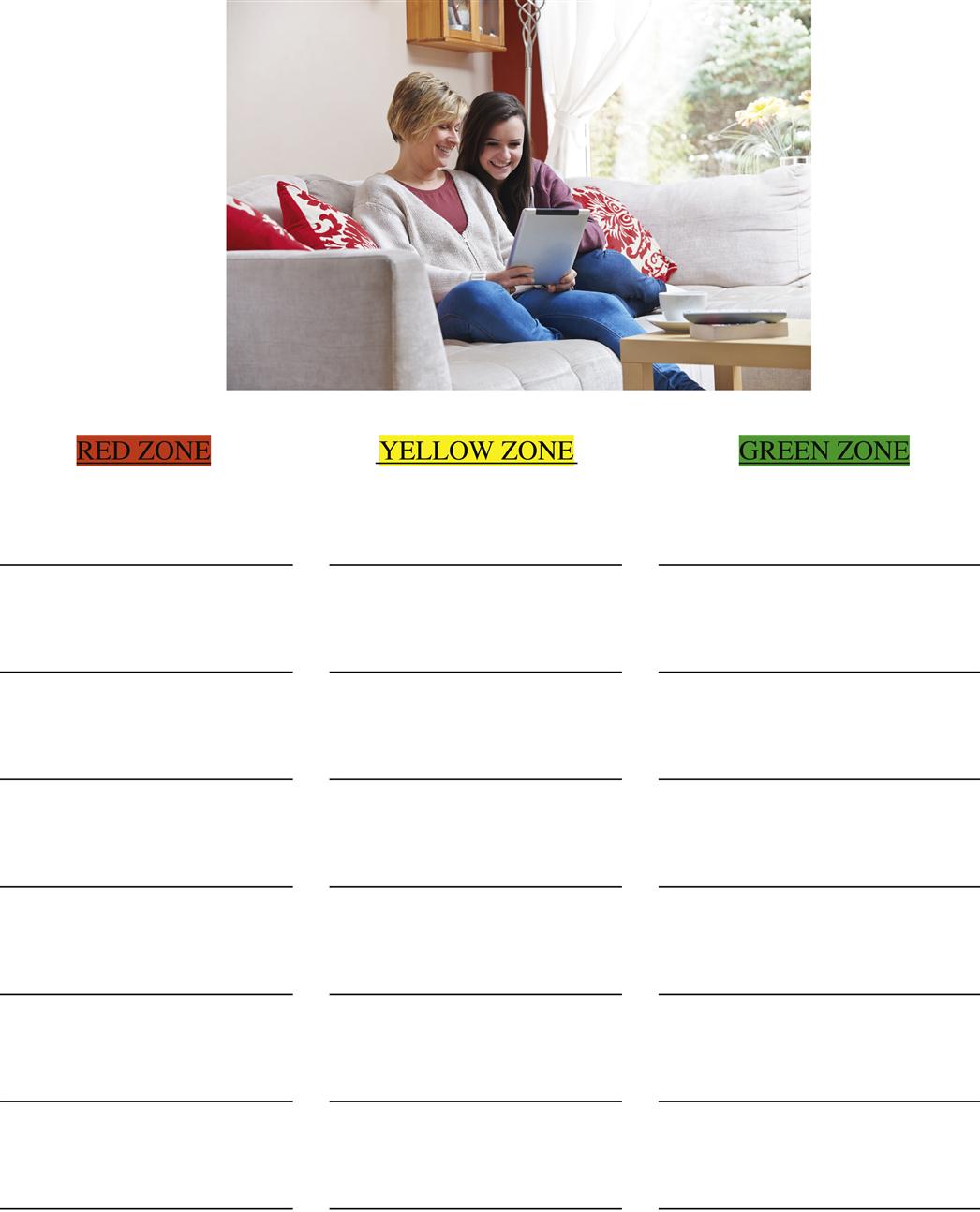

Given the common family dynamic which has evolved in families who present for treatment, it is helpful to provide a structure or system for parents (and teens) to prioritize behaviors and disagreements and put them in perspective, relative to one another.

On the dry erase board, create the following three headings, side by side:

| RED Zone | YELLOW Zone | GREEN Zone |

This method of prioritizing behaviors is similar to those proposed by Ross Greene et al. (2003) and Stanley Turecki and L. Tonner (2000), who advise parents to reflect upon and order parental goals, before developing or implementing any behavioral interventions. The “Red Zone” category is intended as a place to list behaviors which are unsafe or illegal, constituting examples which are not at all negotiable and pose a potential risk of loss of life or limb. Initially, parents often argue for the inclusion of behaviors which are not dangerous or illegal in this category, insisting that from their perspective, certain behaviors are utterly intolerable. Examples could include “cursing,” “being disrespectful,” and “dressing inappropriately.” However they should be offered feedback, that although such behaviors may represent important priorities in their households; they certainly do not pose a potential threat of serious injury, death, or incarceration. Those behaviors can nonetheless be assigned a high level of priority, and slated as targets to be addressed, by listing them under category “Yellow Zone.”

The “Yellow Zone” category is intended for behaviors which are important to the caregivers, but for which the details and nuances are open to some degree of debate and negotiation. These behaviors will serve as fodder for the PST exercises that follow and are recommended as the agendas upon which families should focus, in their parent–teen interactions and behavioral contract negotiations. Examples include homework, hygiene, friends, chores, curfew, cell phone, and computer access. The last category, “Green Zone,” represents behaviors which the parent might find annoying but that they are willing to ignore or forgive, for the time being, given the other behavioral priorities they have identified. Examples might include their teen’s choice of style of hair or dress, poor table manners, consumption of junk food, or choice of music. Provide parents with PACK-Teen Module 4 Handout #17 with the three above-mentioned categories as headings and invite them to work together and with their teens, to create a customized list of behaviors, relevant to their household, as part of the family homework.

Problem Solving Together

Make the point to the group that the “problems” that arise in families, which tend to generate conflict between family members, especially between parents and teens, typically involve wishes that are at odds or compete with one another. It is often helpful to reframe family “problems,” which represent parent–teen conflicts, as competing “wishes.” In other words, the goal of parent–teen problem-solving efforts is really to clarify, accurately define, and reconcile or align the competing wishes each party is entertaining. Any time the term problem-solving is used in reference to efforts to address parent–teen conflicts, the verbiage “wish alignment,” can be substituted. Such a reframe can be powerful in generating buy-in to a process for parent–teen conflict resolution, as it is hard not to feel inspired by a goal of “wish alignment” or “wish reconciliation.” In addition, applying that verbiage forces the parties to present their concern in an affirmative manner, rather than negatively or in a way that could activate the other person’s defensiveness. For example, if a parent is concerned about school, they are required to reframe their concern as a wish, such as “I would like Johnny to complete all homework daily,” versus “Johnny has to stop blowing off school.” Or if a parent is concerned about dating, they might state their wish as “I want to ensure Suzy is safe, at all times,” versus, “Suzy is behaving inappropriately, when it comes to dating.” Lastly, with a goal of wish alignment under consideration, the ideas for solutions generated are more likely to address the concerns or agendas of both parties. Consider the following examples:

• A teen would like to borrow the car to drive to a friend’s house at night, while the parent wants to ensure the teen returns home safely, prior to the neighbor curfew. How can these two wishes be reconciled?

• A teen is spending time each afternoon playing video games, but the parent is worried about homework and chores being completed. How can these two wishes be reconciled?

• A teen is asking to spend the night at a friend’s house, but the parent wants the teen to remain home to spend time with visiting relatives. How can these two wishes be reconciled?

• A teen would like to obtain a belly button piercing, but the parent would like the teen to wait a few years before deciding. How can these two wishes be reconciled?

As part of anger management and problem solving or “wish reconciliation,” training in the corresponding adolescent workshops, the teen facilitators teach the acronym D.I.R.T., which is comprised of the followingd:

D stands for define, as in define the problem (represent as two “wishes” if a parent–teen conflict).

I stands for identify, as in identify possible solutions.

R stands for reflect, as in reflect on the possible solutions.

Introduce parents to this same acronym so they can be aware of the format that is familiar to their adolescents. The problem-solving or wish alignment steps represented by D.I.R.T. are inclusive only of the intellectual or cognitive parts of problem solving. The application of the D.I.R.T. steps is predicated on the party using the steps having already processed their upset feelings and achieved a state of relative calm along with lowered physiological arousal. For parents, however, the steps for problem solving—as related to approaching disagreements or conflicts with their adolescents—include an additional, essential component that serves to defuse upset feelings, build an alliance, and bolster self-esteem in their teen. The problem-solving steps for the parents can be remembered as “The 5 D’s” of PST, which include the followinge:

Defuse: Parents can defuse upset by presenting themselves as a calming force, expressing empathy, and using mirroring. Parents can use empathy formulas to express empathy in a nonthreatening way.

Define: Parents should define the problem or competing wishes, first from the teen’s perspective and then their own. It is essential to avoid blame, derogatory language, criticism, or premature suggestions of definitive solutions. Offer the following PST problem definition stems to ensure that the parent follows a model most likely to maintain calm, lower defensiveness, and build an alliance:

“I hear you saying that…. However, I am worried that….”

“I understand you feel as though…. However, I get upset when….”

Da’ Party: Invite the teen to a problem-solving (wish alignment) or idea brainstorming party. Begin with, “Let’s put our heads together and see if we can figure out a solution where we both get what we want.” This brainstorming session is best facilitated by the active avoidance of any critique or commentary regarding ideas and by simply writing them all down, even the provocative or outrageous ones. Essentially the message at this juncture is that “anything goes” or “anything is possible.”

Decide: Review the list of ideas and contemplate which ones are “hot-headed,” and which are “cool-headed.” Together with the teen, pick one that is realistic and acceptable to both parties.

Do it: Implement the plan, ensuring a mechanism for tracking its success.

Through Socratic discussion within the parent group, make the point that any conflict, dilemma, or problematic behavior may be approached and resolved a myriad of ways. In the business world, good managers know that if they involve staff in the process of developing a system or strategy to achieve the company’s agenda, the staff is much more inclined to feel valued, inspired, and motivated to follow through. Adolescents, likewise—especially those who are defiant or defensive—want to have input into the events and decisions that affect their lives. They respond more cooperatively if they feel as though their feelings have been understood and validated and their agenda was at least considered while possible solutions were being formulated. They are much more likely to cooperate with their parent’s agenda if they have been invited to play at least some role in identifying a solution.

Many parents will express concern about the suggestion of following the PST process in approaching conflicts with their adolescent, feeling as though it may lead to permissiveness or “giving in.” They often relate their desire to be “in charge,” endorse feeling entitled to “call the shots,” and complain that they should not have to negotiate solutions to parent–teen conflicts with their adolescents. The parents can be asked to relate how effective a coercive, dogmatic, or directive approach has been, in addressing concerns with their adolescents. They will typically readily admit that such tactics are not only ineffectual, but generate intense conflict and served to “drive a wedge” between parents and teens. Using a Socratic method of teaching, help the parents appreciate that engaging in a collaborative process inevitably increases the chances that the teen will voluntarily cooperate, internalize a desire to change his or her behavior, and take ownership for his or her actions even when the parent is not present.

Having used themselves as a calming force, expressed empathy, and done some mirroring, the parents will have reassured the adolescent that their agenda or concern is understood, respected, and firmly “on the table” for consideration. The teen typically will calm and “soften,” knowing that he or she has been heard and that the parents are not about to dismiss his or her agenda or attempt to control or box him or her in (a defiant, defensive teen’s worst fear). It is only then that the adolescent is likely to be more receptive to hearing the parents’ concerns and agenda. The parents can summarize the teen’s feelings and viewpoints and then briefly mention the parents’ own agenda. The parents should keep this part short and must be very cautious with respect to how they word their concern. They will rapidly lose their audience and alliance if they begin to launch into a long lecture or lesson. So, too, it is essential that the parents just state the facts regarding the problem behavior and that they be specific.

It is important for the parents to avoid judging or interpreting the behavior. Parents should be careful to avoid the use of shame, blame, or put downs and are wise to completely avoid the use of the words “but” or “you” when stating their concerns. To the degree possible, the parents should avoid even mentioning the adolescent at all and instead share their worry or concern in a more generic way that does not specifically implicate the teen. In addition, parents should be careful not to insert their own solution prematurely but rather only briefly highlight their feelings and viewpoint.

In summary, the principles regarding ideal wording of the parents’ version of the problem or wish (after hearing their teen out, expressing empathy, and mirroring) include use of neutral language, use of feeling words, and identification of a specific behavior about which the parents are concerned. What works best is for parents to recap the adolescent’s feelings and agenda before succinctly sharing their agenda. The parent can use standard verbiage or “stems” such as those mentioned above, under the definition portion of the “5 D’s” of PST. Consider the following examples:

Johnny has been hitting Suzy. Rather than saying “I’m concerned about how nasty and rotten you are to your sister,” it would be better to say, “Johnny, I hear you saying that Suzy annoys you a great deal; however, I get upset when one person I love hits another person I love” or, “However, I’m not okay with name calling or hitting.” They could then formulate their agenda in the style of expressing a wish, such as “I’d like our family to express anger in a safe way, at all times.”

Tommy has been refusing to shower and change his clothes. Rather than saying “You’re going to have to shower and change your clothes daily,” it would be better to say, “Tommy, I hear how much you hate showering and changing your clothes; however, I worry about health when showers aren’t taken” or, “However, I am concerned that not showering may lead to poor health.” The wish that corresponds might be expressed as “I’d like my family to maintain healthy hygiene at all times.”

Bobby has been refusing to complete his homework. Rather than saying “You must do your homework,” it would be better to say,” “Bobby, I understand you find homework frustrating and you’d rather play video games; however, I worry that if the homework doesn’t get done, it will be hard to learn” or, “However, I get upset when the homework doesn’t get done.” The parent might state a corresponding wish as “I’d like my children to complete all homework daily, and turn it in by deadlines.”

Reiterate that the goal is to lower arousal in the parent and teen, build an alliance between the parent and teen, and then put the teen’s concern on the table followed by the parent’s. With the problem defined from both the adolescent and parent’s perspectives, the brainstorming and problem-solving process can begin. Effective and cooperative problem solving (or wish alignment) can only occur if both parties are calm, feel listened to, and have established a spirit of collaboration.

Help parents recognize the reality that most youngsters, when calm and in a cooperative state of mind, are fully capable of creative and effective problem solving or wish reconciliation. In fact, while calm and in a cooperative frame of mind, youth are often willing and able to generate ingenious and creative solutions, even above and beyond options parents are able to conjure up on their best day. Many adolescents with emotional and behavior disorders, however, are not masterful at regulating their feelings and controlling their impulses. They need help and support around modulating and coping with the intense, negative feelings that often overwhelm them. In the case of youth with severe mood dysregulation, the most powerful intervention parents can provide is assistance with monitoring, labeling, discussing, and processing their feelings. Parents can model calmness, serve as a calming force, and use mirroring and empathy to achieve that end.

As in any brainstorming session, ensure that the parents appreciate that it is essential for all parties to refrain from commenting or critiquing. This, again, is well known in the business world. The idea is to facilitate the generation of a wide array of ideas and potential solutions. No idea is wrong or out of the question, at least during the brainstorming phase. It is extremely powerful for the parent to go ahead and write down all ideas. In the beginning, this process may seem awkward and go slowly. Parents and adolescents may need to grow into this process if they never have attempted it before. It is better if parents encourage teens to generate ideas rather than supplying the majority of ideas themselves. Often, parents can readily identify a simple, mutually satisfactory solution, but they should attempt to hold back and allow the teen an opportunity to solve the problem. We repeatedly recommend to parents that they strive to “play dumb” with their adolescent whenever they are engaged in a mutual problem-solving exercise; instead, they should work to solicit as many ideas as possible from their teens.

Suggest that the underlying goal of this style of approach is to propel youngsters to become invested and intrinsically motivated to pursue a workable solution. This is more likely to occur once they feel heard and validated and have been invited to generate ideas for solving the problem and/or resolving the conflict. It may help to ask parents, “Whose idea is the most brilliant, anyway?” A defiant, defensive teen, especially, is most likely to find his or her own idea the most brilliant and therefore embrace it. Every session of problem solving is an opportunity for relationship building and learning. The youngster is being taught effective conflict resolution and problem-solving skills, which in turn foster resilience or the capacity to “bounce back” from stress. In addition, the odds of cooperation increase if the adolescent has been actively involved in the process of evolving a reasonable agreement that is acceptable to both the parent and the teen.

After parents have engineered a creative brainstorming session with their youngster, during which a number of potential solutions have been identified and written down, the parent and teen can set about the process of selecting the most viable option. Some of the potential options will seem workable and some may sound outrageous, but it is important for parents to nonetheless tolerate them all and jot them down as possibilities during the brainstorming phase. Usually, after this process has occurred, the adolescent has become calmer, more flexible, and more willing to compromise and cooperate. With both parent and teen working together as a problem-solving team, effective and positive outcomes are likely to be forthcoming.

Distribute to parents the PST script located on the book’s companion website as PACK-Teen Module 4, Handout #16 and also printed for your reference at the end of the bulleted outline for this module. This script was developed to illustrate how the process might look in an ideal world. Ask two parents to volunteer and read the script that appears below, aloud as if role-playing the scenario:

The problem: Your older daughter Laura, aged 13 years, has been insulting and threatening your younger daughter Emily, aged 5 years:

Mother: I’ve noticed Emily has really been on your nerves a lot lately.

Laura: Yeah. She is an annoying little brat and won’t leave me alone.

Mother: Sounds like you’ve had it with Emily.

Laura: Well how would you like it if she followed you around all day and constantly took your stuff?!

Mother: So you feel as though she won’t respect your privacy and your things.

Laura: Exactly—she’s so spoiled and gets away with murder! I can’t stand her. I wish I was an only child!

Mother: It sounds like you’ve had it with Emily. I can see you really just want her to leave you, your room, and your things alone.

Laura: Plus she also deliberately mimics everything I say and do. I hate that. Why can’t she get her own personality?

Mother: So you also want her to stop imitating you and do her own thing. I can see your points and get why you’re so frustrated. However, I get upset when one person I love says hurtful things to another person I love. I don’t want to see anyone I love get their feelings hurt. Plus I’d like this family to work out their differences in a more positive way.

Laura: She deserves it. She brings it on herself. I warn her, but she doesn’t listen!

Mother: So you’ve been trying to give her warnings, but she hasn’t been listening. I hear how much she annoys you and agree that her behaviors have contributed to the problem. I’d like us to work out other ways of dealing with Emily, that won’t leave her feeling put down. Let’s put our heads together and see what we can come up with, so that she’ll leave you alone, and you won’t get so frustrated that you resort to yelling. What ideas do you have?

Laura: Give her up for adoption.

Mother: That’s one idea—I’m writing it down. What else?

Laura: I could lock my door.

Mother: Okay, that’s another option. Anything else?

Laura: I could lock up or hide my stuff that I don’t want her to touch.

Mother: Do you have any things you don’t mind her playing with?

Laura: A few. I could set up times to play with her, because I think what’s really going on is just that she wants more of my attention.

Mother: We could set up rules about which things she can and cannot touch and certain times she’s allowed to be in your room and other times she’s not. We could even post a schedule on your door. Also, you could reward her by playing with her when she respects your property and privacy. If she violates the contract, then play times with you could get revoked.

Laura: Those are actually pretty good ideas. I’m going to write up a schedule and contract for her to sign. I can also come up with some things of mine that I wouldn’t mind giving her, if she follows our agreement.

Through didactic discussion, the details regarding the nature of the problem being explored with PST and the potential solutions are not important. The bottom line goal is for parents to approach any conflict or problem with a spirit of collaboration. The sense parents should convey is that “We’re in this together,” “We’re on the same side,” and “We can work this out if we put our heads together.” This process will facilitate communication, build the relationship, teach and model life skills, and foster resiliency.

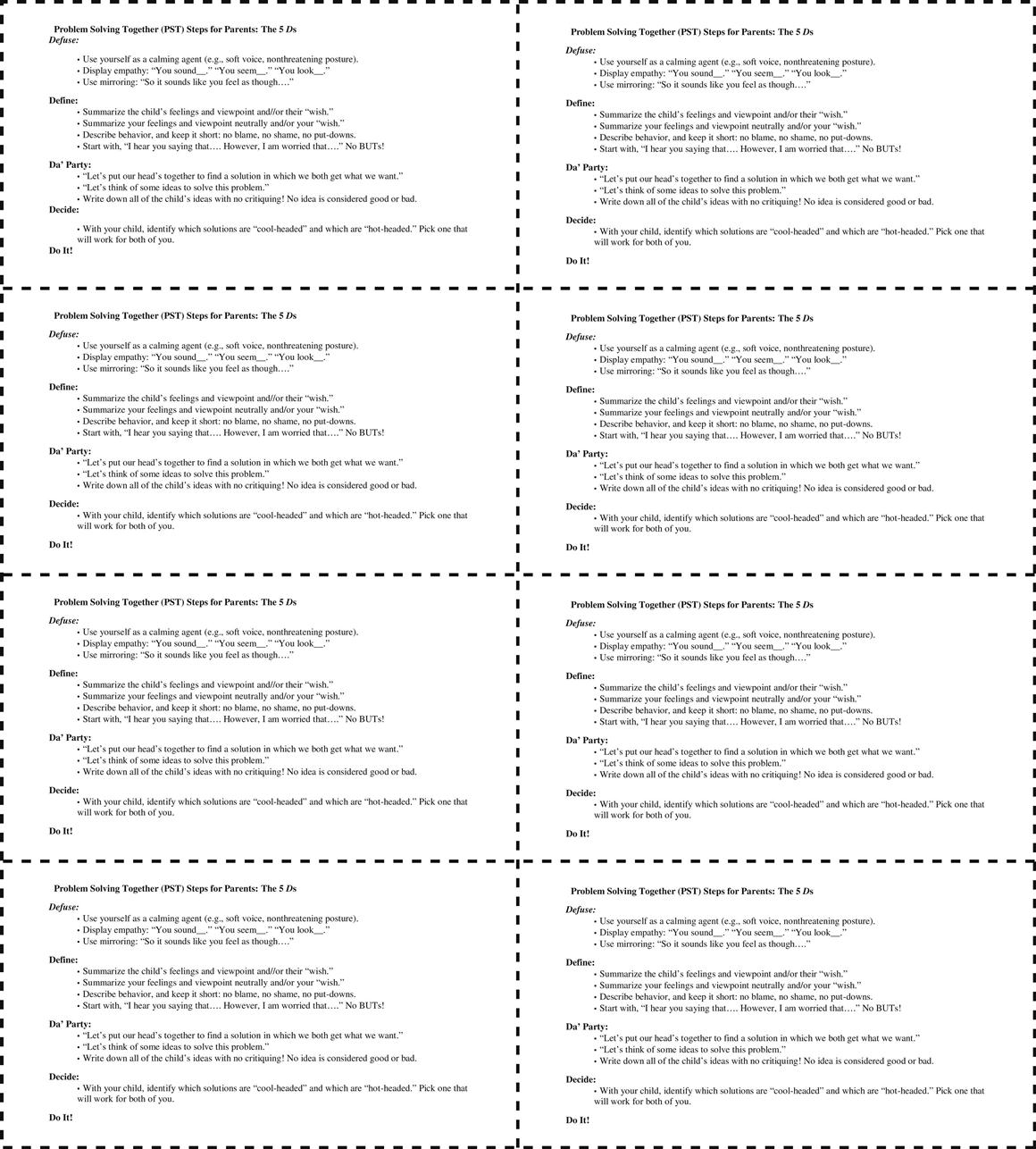

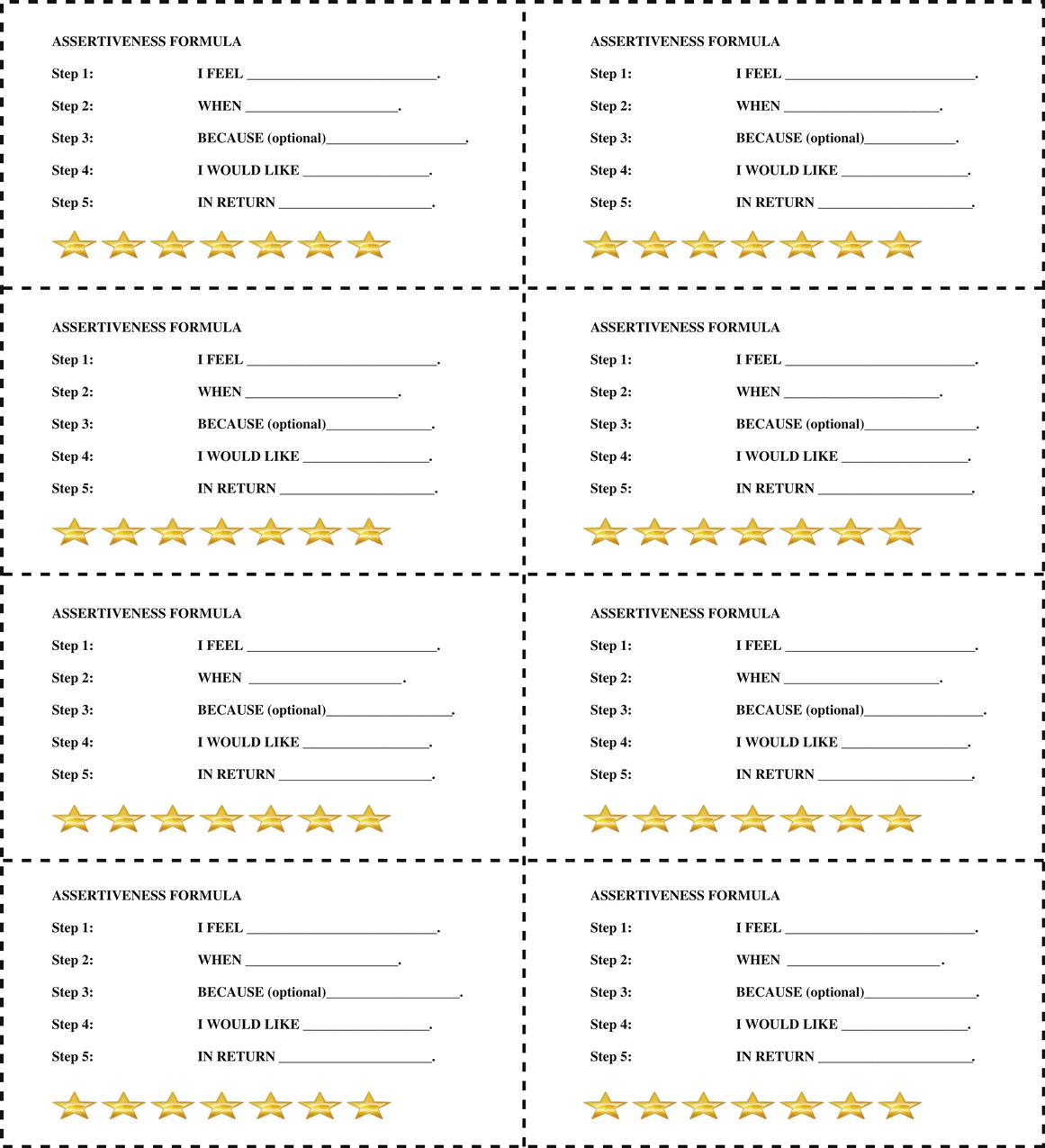

PST Role-Plays

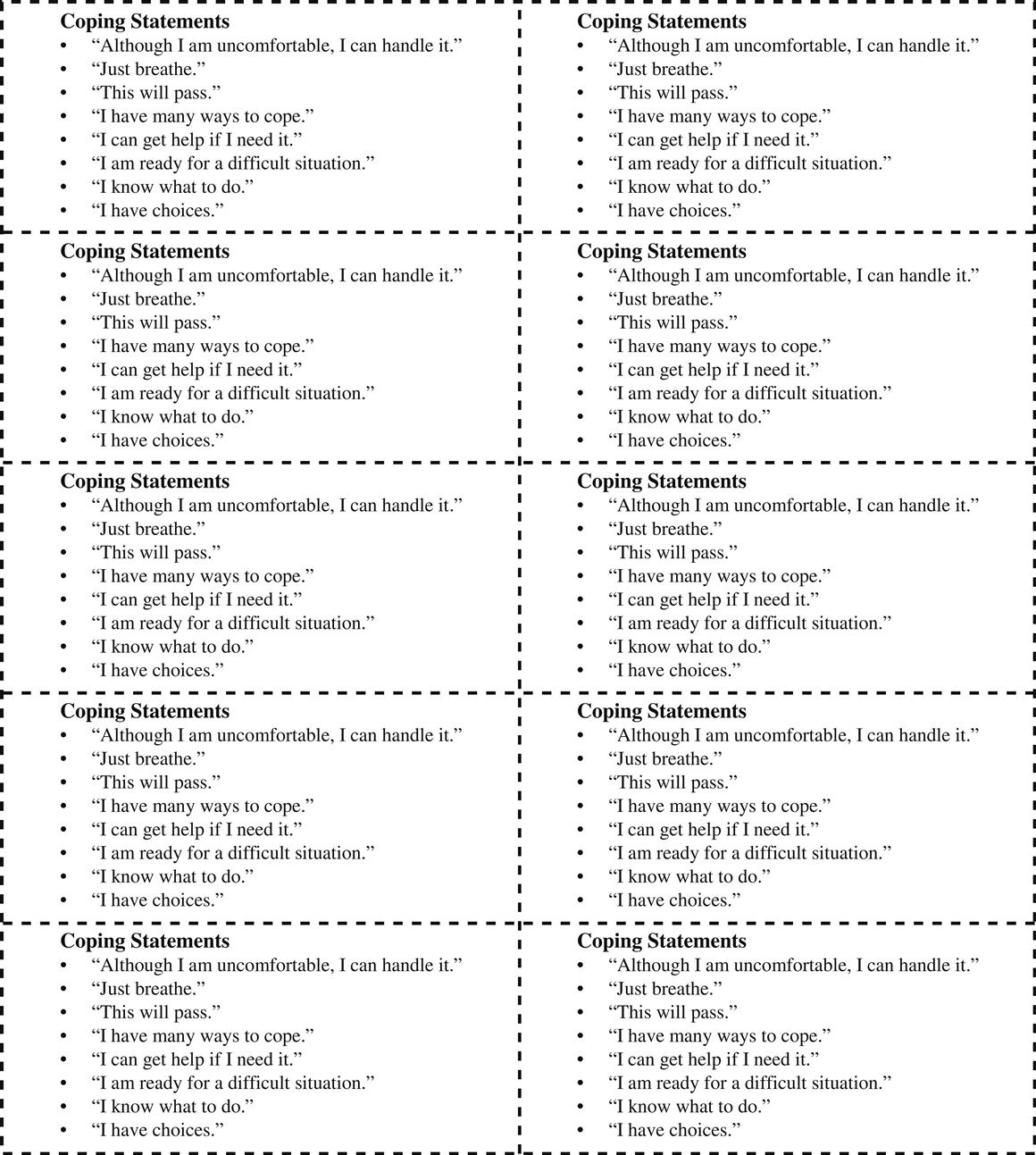

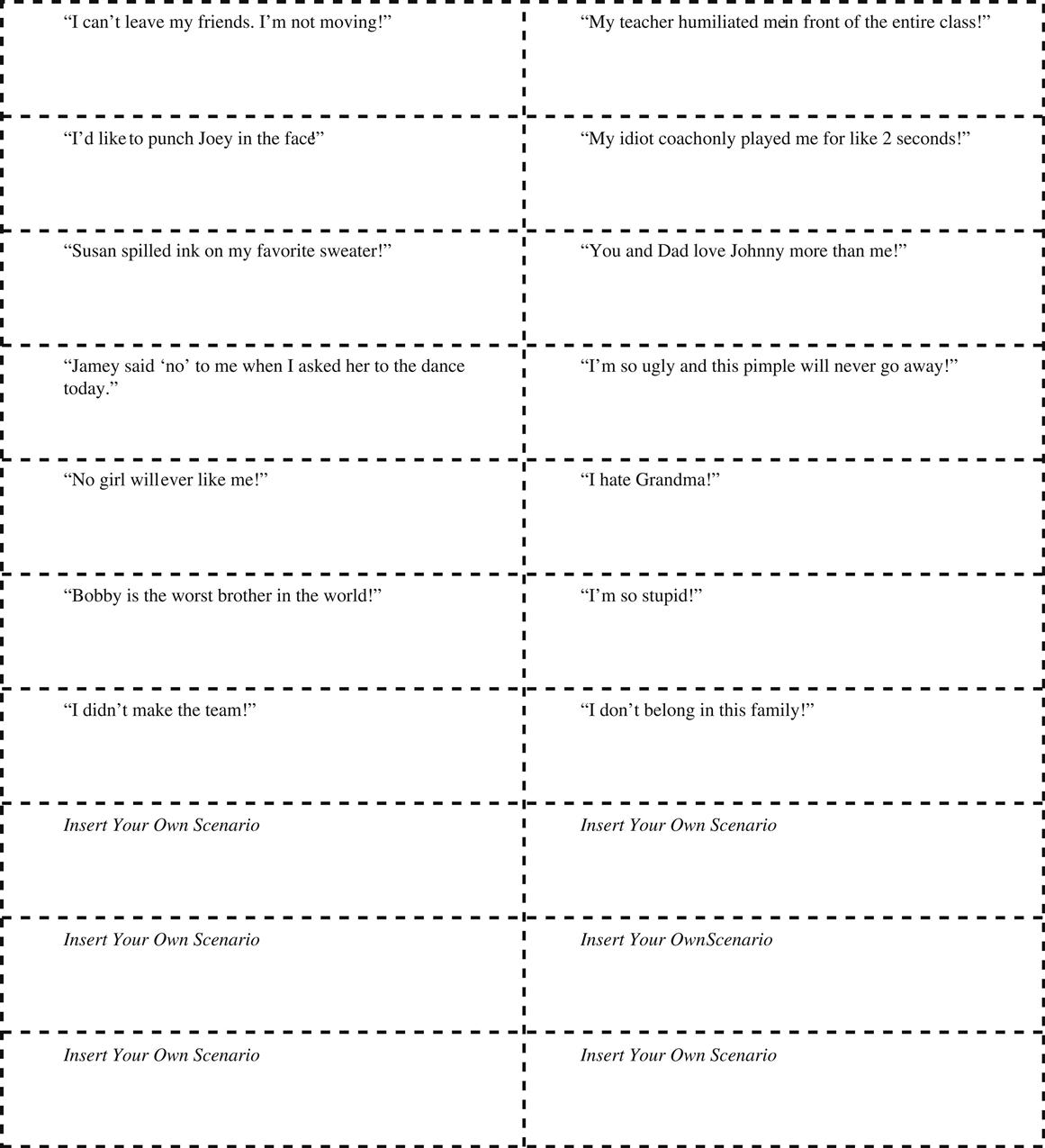

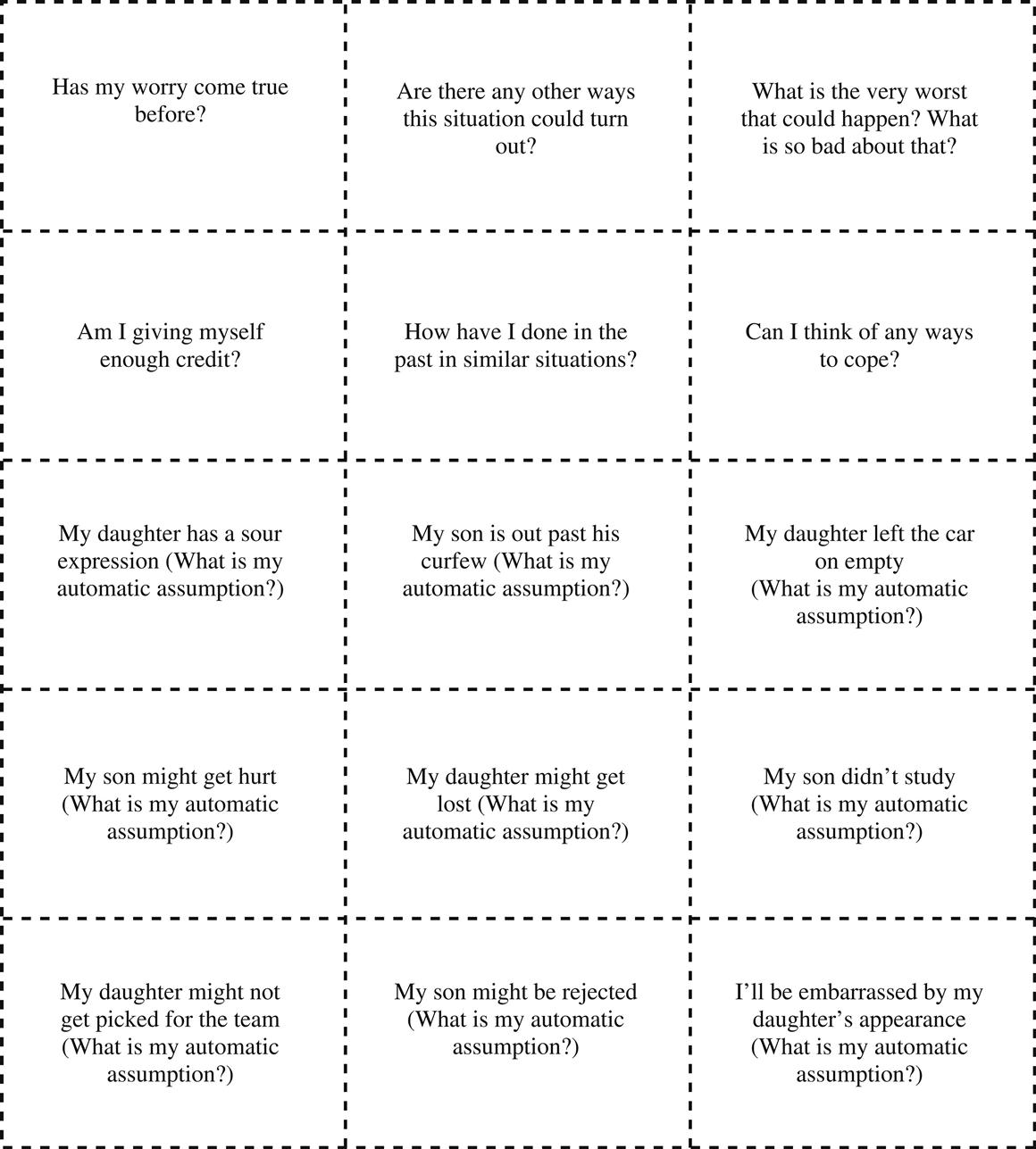

Here again, as with empathy and effective parent–teen communication, this process is fairly straightforward to comprehend intellectually but often difficult to employ in reality—especially in the heat of the moment. Encourage parents to role-play problem solving during the workshop. Give them copies of PACK-Teen, Module 4 Handout #15, describing the PST Steps for Parents: The 5 D’s, along with copies of the PST worksheet, PACK-Teen Module 4, Handout #18, available on the book’s companion website—to use as guidelines, and coach them throughout these exercises.

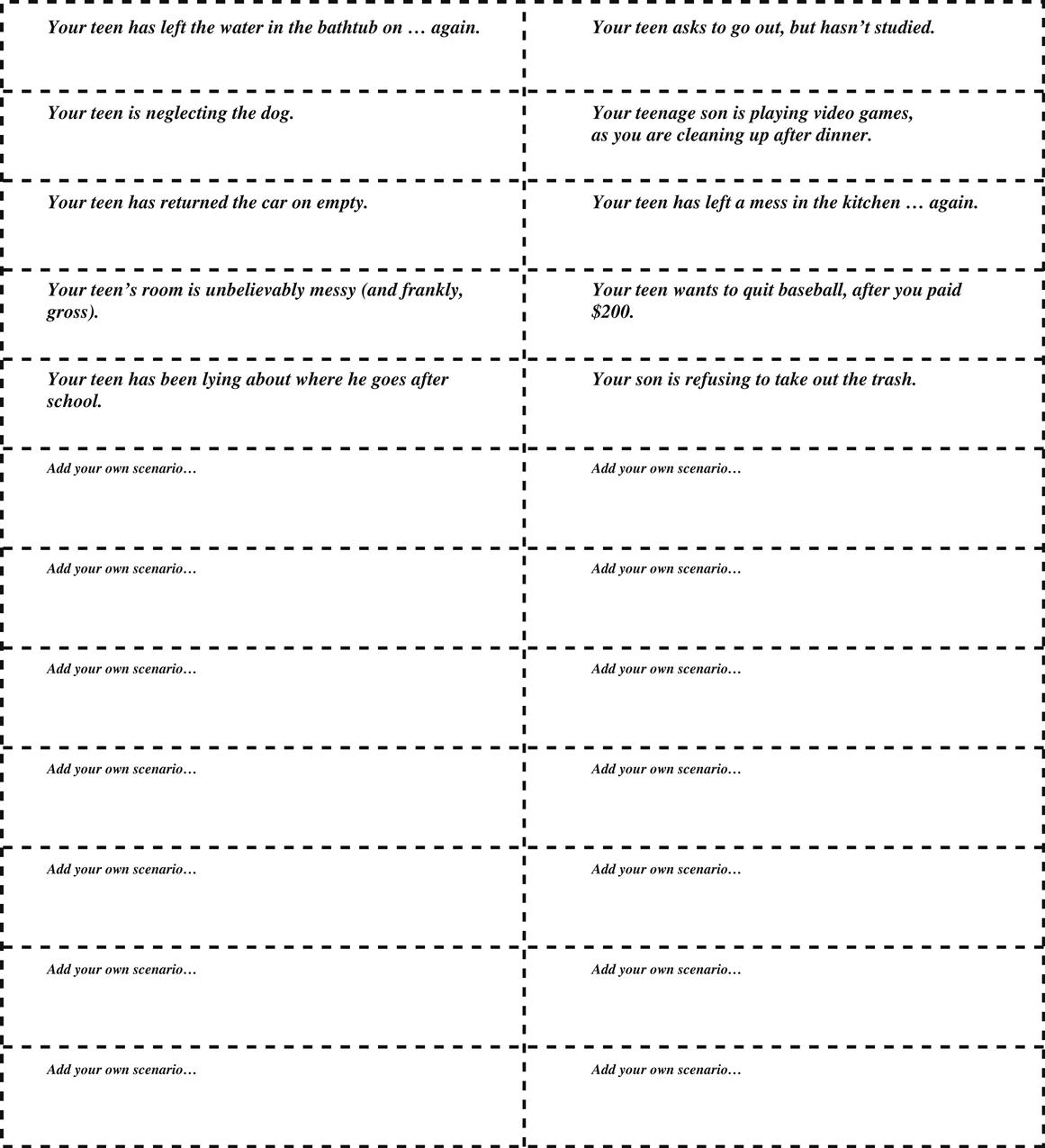

The parents can also be provided with “business cards” describing the “5 D’s” to keep in their wallets, as a handy reminder. Sample scenarios are available on the book’s companion website in the Module 4 PACK-Teen Therapist’s Toolbox. Some cards have been left blank deliberately so they can be used by parents to write down their own examples derived from actual experiences with their adolescent. Caution the parents that their teens are likely to say provocative things during this exercise but that they should avoid taking the bait. During the brainstorm, anything goes, and the parents should be advised to write down all ideas without commenting about whether they are good or bad. During the subsequent week, while home, encourage parents to “play dumb” and seek advice from their teens regarding problem solving.

Joint Session for Module 4

During the second IOP session of the week, after first having the parent and teen groups check in separately, have them join to practice problem solving together. In a group format, have the adolescents teach the steps for problem solving to their parents, using the D.I.R.T. acronym. Invite suggestion of an issue or behavior that might be mildly contentious, between parents and teens, that most participants would agree falls into the “yellow zone” category. The example can be a real one or hypothetical. It is recommended that the first issues or behaviors tackled during practice of PST, represent issues that are “low stakes” and not sources of intense and long-standing feelings and parent–teen conflict. This point should be reiterated multiple times, especially in discussions of recommendations for practice at home, within families. As greater ease and mastery of the PST process is achieved within families, parent–teen dyads can increasingly use the steps to resolve higher stakes, more “hot button” issues.

Using the example agreed upon, facilitate one or more PST exercises with the group using the steps and verbiage familiar to the adolescents. Invite the group to define the problem, which reflects a real or hypothetical parent–teen conflict, in two parts or as two wishes. Encourage the group to word the wishes affirmatively, devoid of blame or criticism for the other person. Empathize that it is essential for both parties in the dyad to feel satisfied with the description of their version of the problem or wish. Also cue the group to brainstorm about solutions that might aptly fulfill the wishes of both parties, or satisfy both the teen and parent’s agendas. Remind the group that the goal is to arrive at a “win–win” resolution for the conflict. The point should be made, via Socratic questioning, that in relationships, especially priority ones within families, any outcome other than a “win–win” is a “lose.” As with some of the other techniques presented in this book, it is a good idea for the parent and teen groups to have rehearsed separately before joining them together to practice.

Family Homework

For homework, encourage each family to negotiate potential behaviors or issues, upon which all would agree fall into the “yellow zone” category, that is, there is room for compromise.

Advise the families to practice the PST technique at home with real scenarios, at least twice prior to the next session, although caution them to initially practice on minor issues, that are more readily resolved and less contentious. As they develop mastery of this process, they can move to medium-sized conflicts and ultimately graduate to high-stakes zones, with histories of heated debates.

Therapists should discuss and hand out the Practice with PST: The 5 D’s worksheet located on the book’s companion website in the PACK-Teen Parent Workbook section, under PACK-Teen Module 4, which can be assigned to facilitate family homework. You can provide parents with extra copies of the worksheet and have them use it as a reference, while practicing PST at home with their teens. Invite them to report back on their efforts, at the next workshop. The teens have been learning the acronym for problem solving D.I.R.T. concurrently during MaPS-Teen Module 4, which maps onto the second–fifth D of the parent “5 D’s” acronym.

PACK Module 4 Summary Outline

Materials Needed

Established Parent Introductions and Check-Ins

• Have the introduction and check-in format for new versus established parents written on the board.

• Go around the room and have each established parent take turns doing as follows:

• Ask each parent to identify themselves by first name.

• Ask each parent to mention their teen’s first name.

• Ask each new parent to mention one “victory” or success (required) and “challenge” (optional), from the past week, related to their teen.

• If there are new parents, invite each established parent to help in orienting the new parents to the workshop format and guidelines.

• Established parents may check-in regarding their family progress, including approaches they tried which were effective thus far.

Workshop Guidelines

• Workshop consistently starts on time and finishes on time, punctuality required, leaving early or stepping out of workshop during session, are not allowed.

• Confidentiality required, “What is said in here, stays in here,” playfully termed the “Vegas Rule.”

• Exceptions are safety issues (suicidality, homicidality, violence, abuse/neglect).

• Refrain from developing personal relationships outside group while in program.

• All cell phones, pagers, electronics of any kind must be turned off during group.

New Parent Introductions and Check-Ins

• Have the introduction and check-in format written on the board.

• Take turns having each parent introduce themselves and check-in as follows:

• Ask each parent to identify themselves by first name.

• Ask each new parent to mention one positive feature or strength of their adolescent and mention one “challenging behavior” they’d like to focus on.

• Ask established parents to comment on commonalities noted during new parent check-ins.

New Parent Orientation

Discuss “Win–Win” Conflict Resolution

Setting the Stage for Problem Solving

Review Empathy and Mirroring

Introduce PST

• Generate discussion regarding patterns of family conflict.

• Parent–teen conflicts or “problems” typically represent two wishes or agendas that compete or oppose one another.

• The goal of family problem solving or “wish alignment” or “wish reconciliation” is to evolve a plan whereby both the teen and parents feel satisfied that their wish will be realized to their satisfaction.

Introduce the Teen Version of PST—Acronym D.I.R.T.

Introduce the Parent Version of PST—The 5 D’s

• Defuse: Parents can defuse upset by presenting themselves as a calming force, expressing empathy, and using mirroring. Parents can use empathy formulas to express empathy in a nonthreatening way.

• Define: There are two versions of the “problem” or two opposing “wishes” to consider. Parents should define the problem or “wish” first from the teen’s perspective and then their own. It is essential to avoid blame, derogatory language, criticism, or premature suggestions of definitive solutions. It is helpful to reframe for the “problems,” as “wishes” which are at odds. Instead of “problem solving,” this process can be termed “wish alignment” or “wish reconciliation.” Offer the following PST formulas to ensure that the parent follows a model most likely to maintain calm, lower defensiveness, and build an alliance:

• “I hear you saying that…. However, I am worried that….”

• “I understand you feel as though…. However, I get upset when….”

• Da’ Party: Invite the teen to a problem-solving or idea party. Begin with, “Let’s put our heads together and see if we can figure out a solution from which we both get what we want.” This brainstorming session is best facilitated through the avoidance of any critique or commentary regarding ideas. Instead, simply write them all down, even the provocative or outrageous ones.

• Decide: Review the list of ideas and contemplate which ones are “hot-headed,” and which are “cool-headed.” Together with the teen, pick one that is realistic and acceptable to both parties.

• Do it: Implement the plan, ensuring a mechanism for tracking its success.

Present an Example of Effective Problem Solving

Perform PST Role-Plays

Discuss Troubleshooting if the Solution Does Not Work

• Parents may ask, “What if the plan you and your teen agree upon works for a while and then fails? Suppose the teen reverts to his or her old ways? What then?”

• Parents either can go back to lecturing and punishing or go back to the drawing board.

• Even the most perfect plan will not be permanent. What worked for the teen when he was 15 years old may not work for him when he turns 16. Parenting is a continual process of readjustment and facing new problems. By involving teens in the search for solutions, parents provide them with the tools they need to help them solve the problems that confront them now and in the future when they are on their own.

• Example of parental approach when solution has failed:

• Parent: “I’m disappointed that our ideas aren’t working anymore. I’ve observed you hitting your brother again, and that’s not okay with me. Should we give the old plan another chance? Should we try to figure out what’s getting in the way? Or, do we need to come up a new plan?”

Review, Answer Questions, and Wrap Up

Family Homework

• Discuss and hand out the Practice with PST: The 5 D’s worksheet (located in the PACK-Teen Parent Workbook Module 4 on the book’s companion website).

• The teens also have been learning steps for problem solving during their MaPS-Teen Module 4 session. Encourage parents to seek advice from their teens regarding problem solving at home throughout the following week.

• Ask families to complete at least two D.I.R.T. exercises during the subsequent week.

Joint Session for Module 4

• During the second PACK and MaPS Teen IOP session of the week, there is an opportunity for teens and parents to join together for 60 minutes.

• Have the families negotiate a list of behaviors or issues for which there is “wiggle room” or an opportunity for compromise, aka “Yellow Zone” issues.

• As a group, work through a sample PST exercise.

• Encourage the group to define the problem or parent–teen conflict as two wishes, and word the two components affirmatively without assigning blame or criticizing the other party.

• Cue the group to brainstorm solutions that could result in potential “win–win” resolutions or potentially fulfill the wishes or address the agendas of both parent and teen.

• Point out that any outcome of a disagreement, in the context of a relationship, other than a “win–win” is a “lose.”

Handouts/Business Cards

Module 4-PACK-Teen Parent Handout #15

Problem Solving Together (PST) Steps for Parents: The 5 D's

• Use yourself as a calming agent (soft voice, nonthreatening posture, lower to adolescent’s eye level).

• Display empathy: “You sound___.” “You seem____.” “You look____.” (Insert feeling word such as upset, frustrated, disappointed, sad, hurt, angry, or worried.)

• Use mirroring: “So it sounds like you feel as though….” “So what I hear you saying is….” “So what you are saying is that….” “So the way you see it is….” “So in other words….” Paraphrase or infer the teen’s feelings and viewpoint.

• First summarize the teen’s feelings and point of view and/or their “wish.”

• Summarize your feelings and point of view and/or your “wish.” Use neutral language, describe behavior, and keep it short—no blame, no shame, no put-downs. Start with “I hear you saying that…. However, I am worried that…” or, “I understand you feel as though…. However I get upset when….”

• “Let’s put our heads together and see if we can find a solution where we both get what we want.” “Let’s see if we can find a solution that works for both of us.” “Let’s think of some ideas to solve this problem.”

• Do not critique: No idea is considered good or bad at this point.

• Go down the list and with your teen identify which solutions are “cool-headed” and which are “hot-headed.” Try to pick one that will work for both you and your teen.

Possible next step (optional):

• For recurrent, important problem behaviors or conflicts, you and your teen can write out a behavioral contract with target behaviors, a tracking system, and rewards.

Adapted with Permission from Cook, M. (2012). Transforming Behavior: Training Parents and Kids Together, Brookes Publishing, Baltimore, MD.

Module 4-PACK-Teen Parent Handout #16

Sample Problem Solving Together (PST) Scenario

The problem: Your older daughter Laura, aged 13 years, has been insulting and threatening your younger daughter Emily, aged 5 years:

Mother: I’ve noticed Emily has really been on your nerves a lot lately.

Laura: Yeah. She is an annoying little brat and won’t leave me alone.

Mother: Sounds like you’ve had it with Emily.

Laura: Well how would you like it if she followed you around all day and constantly took your stuff?!

Mother: So you feel as though she won’t respect your privacy and your things.

Laura: Exactly—she’s so spoiled and gets away with murder! I can’t stand her. I wish I was an only child!

Mother: It sounds like you’ve had it with Emily. I can see you really just want her to leave you, your room and your things alone.

Laura: Plus she also deliberately mimics everything I say and do. I hate that. Why can’t she get her own personality?

Mother: So you also want her to stop imitating you and do her own thing. I can see your points and get why you’re so frustrated. However, I get upset when one person I love says hurtful things to another person I love. I don’t want to see anyone I love get their feelings hurt. Plus I’d like this family to work out their differences in a more positive way.

Laura: She deserves it. She brings it on himself. I warn her, but she doesn’t listen!

Mother: So you’ve been trying to give her warnings, but she hasn’t been listening. I hear how much she annoys you and agree that her behaviors have contributed to the problem. I’d like us to work out other ways of dealing with Emily, that won’t leave her feeling put down. Let’s put our heads together and see what we can come up with, so that she’ll leave you alone, and you won’t get so frustrated that you resort to yelling. What ideas do you have?

Laura: Give her up for adoption.

Mother: That’s one idea—I’m writing it down. What else?

Laura: I could lock my door.

Mother: Okay, that’s another option. Anything else?

Laura: I could lock up or hide my stuff that I don’t want her to touch.

Mother: Do you have any things you don’t mind her playing with?

Laura: A few. I could set up times to play with her, because I think what’s really going on is just that she wants more of my attention.

Mother: We could set up rules about which things she can and cannot touch and certain times she’s allowed to be in your room and other times she’s not. We could even post a schedule on your door. Also, you could reward her by playing with her when she respects your property and privacy. If she violates the contract, then play times with you could get revoked.

Laura: Those are actually pretty good ideas. I’m going to write up a schedule and contract for her to sign. I can also come up with some things of mine that I wouldn’t mind giving her, if she follows our agreement.

Module 4-PACK-Teen Parent Handout #17

Module 4-PACK-Teen Sample and Blank Scenario Cards for PST Practice Therapist Tool #6

Module 4-PACK-Teen, PST Steps for Parents Therapist Tool #7

Module 4-PACK-Teen Parent Handout #18

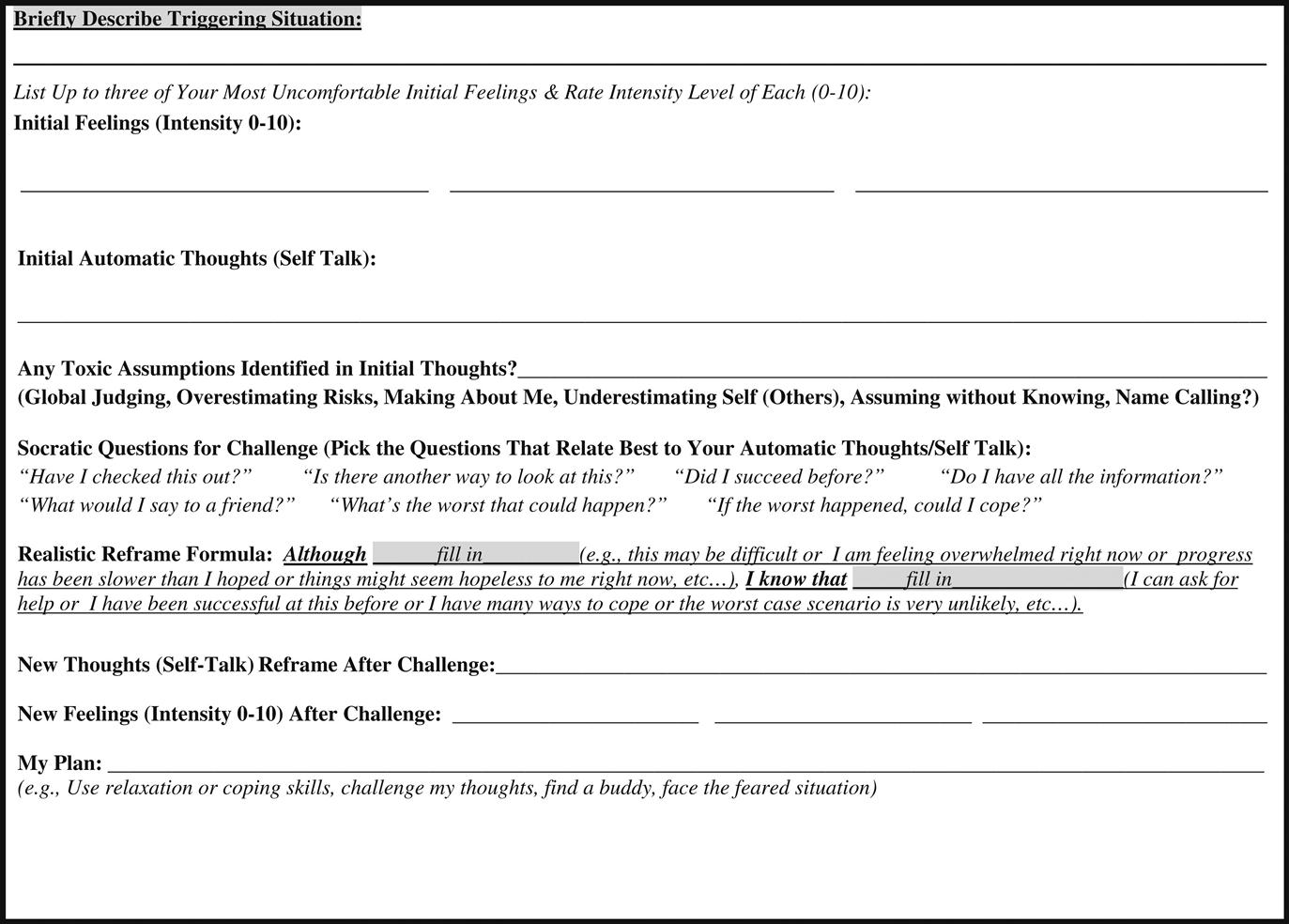

Practice with Problem Solving Together (PST): The 5 D's

Defuse: Lower arousal; listen to your teen’s thoughts and feelings.

Calm yourself, calm the teen, display empathy, and use mirroring.

Parent: ______________________________________________________________________

Teen: ________________________________________________________________________

Parent: ______________________________________________________________________

Teen:________________________________________________________________________

Parent:_______________________________________________________________________

Teen: ________________________________________________________________________

Parent (sum up your teen’s point of view):

___________________________________________________________________________

Define: Summarize their problem or “wish”; then add your worry or feelings and “wish.”

After reiterating the teen’s viewpoint, begin by stating “I hear you saying that…. However I am worried that…” or, “I understand you feel as though…. However, I get upset when….” Or, use assertiveness formula or “I statements.” Express your feelings and state your concern without blaming or attacking. Keep this short!

Parent: ______________________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________________________

Da’ Party: Brainstorm solutions with the teen.

Encourage the teen to start by stating, “Let’s put our heads together and figure out a way that we both can get what we want. “Play dumb” (“I just can’t think of anything else,” “I wonder what would work— …this is a toughie”), write down all ideas, and avoid commenting or critiquing until the end.

Parent: ______________________________________________________________________

Teen: ________________________________________________________________________

Parent: ______________________________________________________________________

Teen:________________________________________________________________________

Parent: ______________________________________________________________________

Teen: ________________________________________________________________________

Parent: ______________________________________________________________________

Decide: Discuss which ideas are best, pick one together, and make a plan to follow through and track progress. For recurrent, problematic behaviors, consider a written contract.

Parent: ______________________________________________________________________

Teen: ________________________________________________________________________

Parent: ______________________________________________________________________

Teen: ________________________________________________________________________

Parent: ______________________________________________________________________

Do It! Implement the plan, ensuring a mechanism for tracking its success.

Parent: ______________________________________________________________________

Teen: ________________________________________________________________________

Parent: ______________________________________________________________________

Teen: ________________________________________________________________________

Parent: ______________________________________________________________________

Possible next step (optional):

Write a contract

For recurrent, important problem behaviors or conflicts, you and your teen can write out a behavioral contract with target behaviors, a tracking system, and rewards.

Adapted with Permission from Cook, M. (2012). Transforming Behavior: Training Parents and Kids Together, Brookes Publishing, Baltimore, MD.

Pack-Teen Module 5

Introductions and Guidelines

To begin PACK-Teen Module 4, refer to the Introductions and Guidelines section that can be found at the beginning of PACK-Teen Module 1.

Communication Test

After the usual beginning routine, hand out another “pop” quiz to start off this session. Provide the same directions as given for the “empathy test.” Invite parents to choose the answer that most closely matches their typical approach. Remind them that no one will be grading the quizzes and that they are only intended to generate discussion. A hard copy of the test appears after the bulleted outline section of this module, as well as in digital form within the PACK-Teen Workbook section on the book’s companion website. Once finished, ask them to set aside the completed tests for later review and discussion.

Cooperation Busters

Just as in the case of empathy, there are a variety of common, typical parenting approaches that inadvertently sabotage good communication and decrease the chances of a cooperative response from youngsters. Introduce these “communication busters” by writing them on a dry erase board. Then present examples and ask parents to select which type of “buster” is being illustrated by each example. The list of “communication busters” includes the following, remembered using the acronym “O.S.P.L.A.T.T.!”f:

Cooperation Busters (“O.S.P.L.A.T.T.!”):

Examples: “Go and clean your room right this minute!” “Mow the lawn, now.” “Take out the trash,” “Feed the dog,” “Do your homework.”

Examples: “I’ve told you a hundred times,” “You need to stop acting like a baby,” “You never listen!”

Examples: “You are such an airhead!” “You are irresponsible…lazy…selfish…(whatever)…”

Examples: “Do you understand how important it is to have nice manners? First impressions are important. If you want to be respected, you need to be polite and make a good impression. You’ll never get a job if you can’t learn how to act right.”

Examples: “You never listen,” “You are so careless,” “How could you?” “If you only planned ahead…” “It’s your own fault,” “You should know better.”

Examples: “You hit your sister one more time and I’ll give you a smack,” “If I catch you lying again, you are grounded for life,” “If you don’t shape up, I’m sending you to military school (or to live with your Dad).”

“The Golden Rule:” A useful rule of thumb, termed “The Golden Rule,” states, “No Shame, No Blame, No Put Downs.”

Through a process of Socratic questioning, help the parents recognize that the approaches described by “The Cooperation Busters,” first of all, aren’t effective, but secondarily tend to alienate youth. Any approach involving a put down can become a self-fulfilling prophecy. For example, if a youngster hears from an adult, especially a parent, that they are viewed as lazy, irresponsible, selfish, they tend to become increasingly that way. Youth see themselves through their parents’ eyes. The labels, good and bad, which are attached to adolescents, tend to tenaciously adhere and become integrated into their self-images. Derogatory labels erode self-esteem and produce shame, as well as generate resentment toward the label user. Youth are not inspired to assume a spirit of cooperation when they are being insulted. It’s hard to follow directions and do what is asked, when someone is telling you what is wrong with you. In addition, teens are made to feel defensive and once defensive, their primitive threat response is activated, which results in them experiencing anything subsequently said as static or the garble that represented the teacher or parent’s voice from Charlie Brown’s cartoon series.

Facilitate a discussion regarding the fact that lectures are a turn off for everyone, especially for youth. Ask the group what adolescents hear, when adults launch into a lecture. The group might mention the teacher’s voice in the old Charlie Brown cartoons. Help the parents recognize, through a course of didactic discussion, that “Wha wha wha wha wha” is what teens generally hear, when a grown-up launches into a long lecture. Lectures are usually not only ineffectual but also experienced as irritating. They don’t improve communication, strengthen relationships or increase cooperation. Most youngsters need to learn most of life’s lessons, on their own, via direct experience. Most youth, especially adolescents, don’t do what parents say but instead what parents do. Suggest to parents that they delete lectures from their repertoire of approaches for effecting positive relational and behavioral changes.

Generate discussion about the use of threats, helping the group appreciate the fact that threats raise anxiety and lower self-esteem. Elevated anxiety usually only aggravates acting out and aggressive behavior. Threats additionally don’t teach anything, improve relationships or enhance psychosocial skills. Parenting goals may be reviewed, briefly. Through a method of Socratic teaching, guide parents to recall their underlying, long-term goal that their youngsters will do the right thing, even when parents are not in the room and even when not faced with potential threats, punishments, or rewards. An additional concern that should be highlighted is that threats drive a wedge between parents and adolescents. Although intimidation and threats do result in compliance in some youth, they nonetheless always pose a risk of jeopardizing an alliance and good relationship between parents and teens.

Besides which, it can be noted, that threats usually don’t result in compliance or cooperation, when applied to defiant, defensive, and willful youth. Threats are experienced by defiant, defensive youth as a challenge and they typically respond with escalated defiance. Another concern is a tendency for many parents to make empty threats. Examples include, “You are grounded forever,” “I’ll never buy you another jacket,” “I’m going to send you to military school.” Sometimes parents make realistic threats but don’t follow through and in so doing, they lose credibility and effectuality.

Orders or commands are also ineffectual and alienating, especially to defiant, defensive youth. Parents are encouraged to think about how they feel when their spouse or boss commands them or gives them an order. Most adults resent commands and are more likely to resist doing whatever it is that’s being asked. Most prefer being asked politely. Some examples of instructions which are more likely to achieve a cooperative response are, “Please take out the trash,” “Please walk the dog.” “Once you do, you can play video games, whatever.” Commands that would alienate and decrease the odds of a cooperative response include, “Clean your room … NOW!” or “Do your homework this minute!” In sum, parent utilization of “Cooperation Busters,” is likely to activate defensiveness, increase defiance, and heighten arousal.

Review Test on Communication

After introducing each of the busters, invite the group to review the test on communication together. Go around the circle and ask the parents to take turns reading each question aloud and then reading the answers. As they read the answers, they should indicate whether the answer illustrates a “Cooperation Buster,” or sounds like a potential “Cooperation Builder.” If they state that an answer represents a buster(s), advise them to indicate which specific one(s) is being demonstrated.

What About My Teen Examples?

After covering each major topic, it is worthwhile for the facilitators to pause and invite some brief discussion, regarding specific examples or applications of the material or skills covered, as related to the child for whom they are attending treatment. The parents and caregivers might be asked to provide an example or two, of instances during which they noted that their child’s level of cooperation seemed to diminish, when approached in the form of a “Cooperation Buster.”

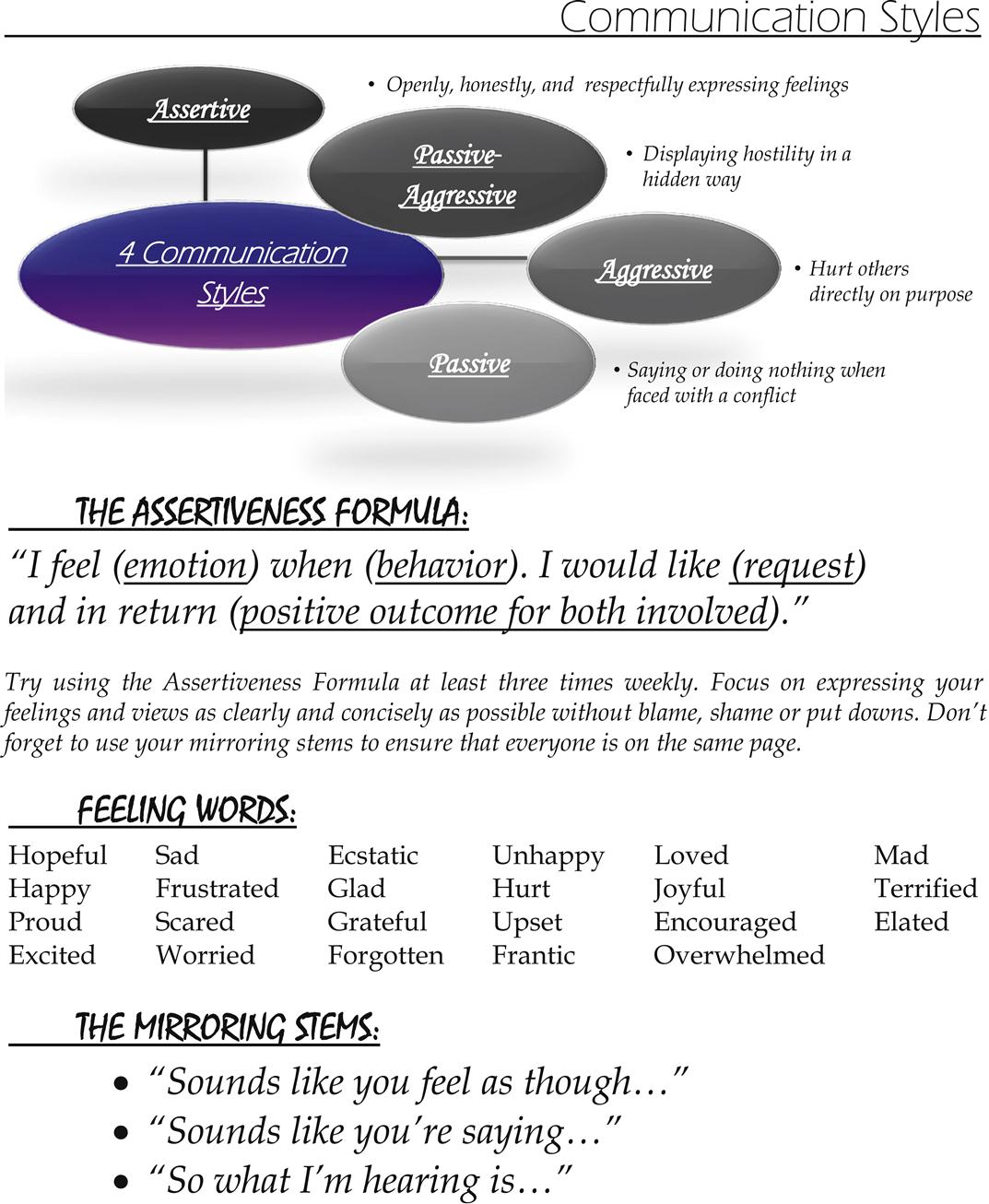

Four Styles of Communication

Before delving into optimal parenting approaches, termed “Cooperation Builders,” by PACK-Teen, which tend to engender cooperative attitudes, the clinicians facilitate a discussion, using the dry erase board, regarding the four styles of communication. Cue them to especially consider patterns of communication around instances during which one individual is expressing concerns, frustration, or anger, to another individual, to whom those concerns pertain. The facilitators use a method of Socratic teaching, as always, starting with and building on what the group members already know. The four types of communication are eventually defined as followsg:

Passive: A passive style of communication implies saying or doing nothing when faced with a social conflict or distressing situation.

Passive–Aggressive: Passive–aggressive communication refers to a style whereby people display hostility or aggression in a covert way. For example, they might deliberately lose or forget something, or show up late to meet someone with whom they are angry.

Aggressive: Aggressive communication refers to physical or verbal aggression, whereby overt hostility is expressed in a way intended to deliberately hurt others.

Assertive: Assertive communication is considered the ideal style. It involves openly and honestly expressing one’s feelings without using shame, blame, or put downs and making simple and clear requests of others.

Relay to parents that assertive communication is the key to “Talking So Kids Will Listen” (Faber & Mazlish, 1980). The counterpart of assertive communication is empathic listening which is the key to “Listening So Kids Will Talk.”

Encourage discussion regarding the importance of imparting and empowering youngsters to stand up for themselves and their beliefs, using words. Aggression and anxiety usually go hand and hand. Youth often behave aggressively when they feel threatened or hurt, or when afraid they won’t be heard or get their needs met. However, aggressive communication obviously comes with a price and typically does not lead to teens getting what they want or need, although nonetheless some persist in this style. Messages delivered in an aggressive style, whether overtly or covertly, whether through body language, tone of voice, or word choice are met with an activation of a threat response from the individual to whom the message is sent. The target of aggressive communication will instinctively and almost instantaneously run away, hide, or fight back.

Invite parents to brainstorm strategies they might deploy to foster a transition in their adolescents, from using a predominately aggressive, to adopting an assertive style of communication. As youngsters become increasingly masterful at regulating their feelings and communicating assertively, they are increasingly able to achieve desired goals and improve their relationships, outcomes which are inherently and powerfully reinforcing. Parents can model assertive communication as their primary style and cultivate an appreciation that assertiveness, rather than aggression, provides them with an ideal mechanism for expressing their needs, which will increase the likelihood that they will get what they want.

Present the following two scenarios, and then read each answer aloud, asking the parents to identify answers as either passive, aggressive, passive–aggressive, or assertive, as you read each answer:

1. You have been waiting in line to purchases tickets to a concert of your teen’s favorite band. You plan to surprise your teen for their 16th birthday. You heard they are running out of tickets and two couples cut in line in front of you.

b. You politely point out the long line and ask them to move to the back (assertive).

c. You start loudly complaining about how rude they are (passive–aggressive).

d. You loudly yell curse words and threaten them if they don’t leave (aggressive).

2. Your coworker asks to piggy back on your presentation right before an important meeting because he went out every night with friends instead of preparing.

a. You pretend you don’t hear him and don’t respond (passive).

b. You call him lazy and tell him to get lost (aggressive).

c. You roll your eyes, sigh loudly and mutter insults under your breath (passive–aggressive).

d. You calmly and politely say, “Sorry man, you need to do your own work.”

Some reflection and review of the guidelines, regarding defining their version of the problem, in following “The 5 D’s” of PST, is useful, at this juncture. The principles to be followed, in ideally wording the concern during assertive communication, are the same and include the deliberate use of neutral language, use of “I statements” and feeling words, identification of a specific behavior, and avoidance of derogatory language, shame, blame, put downs, or accusations. Here again, as with PST, the parent would be wise to avoid the use of the words “But” or “you,” and if possible, avoid specifically mentioning the teen, altogether, while still pointing to a specific behavior about which they have concerns. The therapists are referred back to the narrative section of Module 4, on PST, for additional details and examples.

In our experience, in applying the assertiveness formula to negative feelings and behaviors, parents have been inclined to spend too much time detailing the problem behavior; they occasionally even turn this part of the formula into a lecture. In addition, parents typically make the mistake of using derogatory language and negatively interpreting or judging the behavior rather than just stating it in a brief and neutral way. The behavior needs to be defined concisely, simply, and precisely. Consider the following examples:

Rather than saying, “I feel angry when you are rotten and selfish,” it is better to say, “I feel upset when you call your sister names and won’t share.”

Rather than saying, “I feel frustrated when you turn your room into a pigsty,” it is better to say, “I feel frustrated when you leave your clothes on the floor.”

When done well, assertive requests increase the likelihood that the other person will want to change their behavior, compared to other styles of communication. The most reliable and important barometer of whether or not an individual was effective with their assertive communication is how the person to whom the message was directed responds. Many folks perceive themselves as assertive, but others experience them as aggressive. The assertive communicator must be careful to word their message in a manner that is devoid of “Shame, Blame, or Put Downs.” The listener should respond by exhibiting interest and receptivity to the assertive communicator’s message. The recipient should not react defensively, but instead should demonstrate openness and even express a willingness to change their behavior. An ideally delivered assertive message should elicit a compassionate response and should lead to resolution of a conflict and positive changes in behavior.

Discuss with parents that not only does their use of assertive communication model a desirable behavior; it also significantly increases the chances the adolescent will respond cooperatively and internalize a desire to change their behavior, for the long term. The facilitators suggest a method of using “I statements, to first say how they feel, point out the specific behavior they don’t like, in a nonderogatory, nonblaming way and make a request for a change. The bottom line with assertive communication is that it constitutes the essence of ‘speaking in a way that others will listen.’”

Assertive Communication+Empathic Listening=’s “Win-Win” Conflict Resolution

Remind the group that the counterpart to expressing a message assertively, is empathic listening, which constitutes the essence of “listening so others will talk.” Help the group recognize the merit of honing the skills of assertive communication, along with empathic listening as they relate to facilitating optimal conflict resolution, by presenting the following metaphor:

Conflict Resolution Is a Game of “Precision Catch”

A successful, mutually satisfactory, assertive and empathic interchange is a prerequisite that must transpire before any productive conflict resolution or interpersonal problem solving, can occur. Masterful empathic listening, coupled with astute, on point “mirroring,” requires intense focus, a good deal of self-restraint and a hefty dose of maturity. Dialogues that set up and promulgate effective, synergistic, “win-win,” conflict resolution can be likened to a novel, hypothetical game that might be aptly named “precision catch.” What typically transpires when two individuals experience a disagreement or conflict is that they instinctively and precipitously launch into a contentious debate, akin to a tennis match. In tennis, of course, the object is to “win,” at the expense of one’s opponent, possibly humiliating them in the process. Each player attacks the ball and rallies as rapidly as they are able, never pausing to hold or examine the ball, or give any consideration to the wants or needs of their opponent. The contender with the fastest and most agile maneuvers, coupled with the most powerful and aggressive blows, will most likely triumph over their rival and reign victorious. However, by contrast, consider a game of “precision catch,” perhaps involving a football, in which the goal is simply for a team of two, to achieve the highest percent of completed passes. The passer and the receiver roles are interdependent and interchanging. They are at once on the same team, so therefore continually and enthusiastically rooting for one another. If one does well in their role, it increases the odds of both winning. The receiver is beholden to the passer, to engineer a tight spiral and deliver an accurate, gently arcing, softly thrown football that lands precisely and effortlessly in the receiver’s outstretched hands. The passer is beholden to the receiver to remain open, focused, and prepared for each toss. Such is the case in effective assertive communication—the speaker must transmit their message in a most predictable, discernable manner, devoid of potential for inducing harm, or being deflected or dropped. If the passer is skilled in their throwing abilities and the receiver also competent and attuned, the odds of a successful team outcome are optimized. Of note, in precision catch, the receiver must be solely focused on the role of catching the ball (message) from the passer, during that phase of the game. While preparing to make a catch, the receiver cannot simultaneously be contemplating a passing strategy if they wish to ensure they make their reception. Similarly, during collaborative conflict resolution exchanges, the listener must remain wholly focused on the speaker, rather than mentally forging ahead and preparing their rebuttal. In precision catch, once caught, the ball is held momentarily, before the receiver, who now becomes the passer, lobs it back to the original passer (now the receiver). There is a rhythm and a turn-taking that must transpire, as well as a synergy that is cultivated when both passer and receiver are aligned in a mission to make accurate, gentle passes and catch them carefully and reliably.

Programs for assertiveness training, such as that by Sheila Hermes (1998), often advocate starting out with a formula for assertiveness such as the one that appears below, under “Cooperation Builders Part I.” The group can practice and commit a similar formula to memory. As parents master this style of communication, they can ad lib more and become less reliant on such formulas. Still, these are tough skills to master, even for adults. Mastering this skill set is typically fairly challenging but not untenable.

Reiterate repeatedly the need for the listener, who is intended as the recipient of the assertive message from a speaker, to initially respond by “mirroring” or reflecting back the message they heard, before introducing their own response or potentially competing agenda. What we’ve often observed, when families begin rehearsing assertive communication, is the listener bypasses the empathic listening and mirroring step and instead responds with their own assertive statement that represents their own potentially competing agenda, which leads to head-butting and obstruction of communication flow. The listener can bring their concern or agenda to the negotiation table, but only after demonstrating they’ve clearly heard and understand the viewpoint and feelings of their counterpart.

Summarize to the group that assertive communication means saying what’s on one’s mind in a firm, but polite way, but without attacking, belittling, or blaming the other person. The goal of assertiveness is to put others “in their shoes” and help others understand their perspective and feelings, that is, how they are being affected by the other person’s behavior.

“Business cards” listing the four styles of communication and the assertiveness formula are available on the book’s companion website in the PACK-Teen Module 5 Therapist’s Toolbox section. These cards may be cut out in advance and distributed to the parents, after the four styles of communication have been introduced. The cards may be used during the workshop, to assist with the exercises that follow, and later on, as reminders, for outside the program. Encourage the parents to keep the cards handy in their wallets, backpacks, or purses, and use them, to mentally rehearse the steps for assertive communication, as well as practice the steps in vivo. The teens are being taught the same communication styles and techniques concurrently, in the MaPS-Teen Module 5 workshop, so parents can model and reinforce them with their adolescents.

Practice with Assertive Communication

Assertive communication techniques can be additionally reinforced a variety of ways. Provide each parent with a sample and blank scenario card, for practice of the assertiveness formula, available for cut out on the book’s companion website in the PACK-Teen Module 5 Therapist’s Toolbox. Allow the group a few minutes to fill in their blank scenario card. Once a series of potential scenarios has been generated, ask the parents to contemplate options for addressing the concern on their sample scenario cards and then invite the group to take turns presenting their examples. Invite group discussion regarding the possible responses that demonstrate all four communication styles.

Another helpful exercise to employ with the parents is to have them take turns role-playing scenarios in which assertive responses would be appropriate. The parents often enjoy and embrace such role-plays, because it is an opportunity to dramatically act out the behavior of another person, perhaps their teen, in a manner that discharges frustration in a playful way. Either provide cards with sample scenarios to the parents or invite them to offer scenarios based on their own life experiences. Sample scenarios include the following:

The hairdresser cut your hair two inches shorter than you requested—you feel hideous.

Your teen keeps taking your toiletry supplies such as your toothpaste, shampoo, soap, etc.

Your spouse has a habit of interrupting you mid-sentence.

Your teen tends to address you in a demeaning and disrespectful manner whenever they have friends over.

One of your coworkers keeps teasing you about your voice and laughing and it bothers you a lot.

Your coworker routinely fails to complete their assigned tasks on joint projects.

You want to stay home and watch a movie but your spouse want to go party across town.

Your friend shows up late, changes their plans or cancels, every time you make plans.

During the assertive communication role-plays, keep reminding the listener to respond empathically and first “mirror” or paraphrase what they heard, prior to introducing their viewpoint or agenda to the discussion (again using assertive method).