The Villain vs. the Recluse

ACCORDING TO THE NARRATOR of Barnaby Rudge, “the despisers of mankind … are of two sorts. They who believe their merit neglected and unappreciated, make up one class; they who receive adulation and flattery, knowing their own worthlessness, compose the other. Be sure that the coldest-hearted misanthropes are ever of this last order.”1 This statement is true in Dickens’s early novel, but it doesn’t sum up misanthropy’s role in his other works, where hatred and villainy have dramatic, asocial effects. Moments before hanging himself, for example, Ralph Nickleby toasts “the coming in of every year that brings this cursed world nearer to its end. No bell or book for me,” he adds, in what is doubtless the best speech in Nicholas Nickleby; “throw me on a dunghill, and let me rot there to infect the air!”2

Dickens’s sentimental misanthropes may declare loudly that they’re “neglected and unappreciated,” but most abstain from violence, withdrawing temporarily from communities that would corrupt—and even annihilate—their integrity. He styles them as comically self-involved, not as villainous recluses and hateful sociopaths. Among such characters are Mr. Venus, the “harmless misanthrope” in Our Mutual Friend, and Nicodemus Dumps (“long Dumps”), an amusing curmudgeon in “The Bloomsbury Christening” who forewarns his baby godson about life’s tribulations.3 Such men suffer from neglect, and in Venus’s case (as his name implies) blossom when their love is requited, but their behavior represents a strategic withdrawal from society, rather than a conclusive break with it.4 When many Dickens novels end, these misanthropes catch a benign—even infectious—spirit leading them back to other people. Dickens follows Victorian convention in psychologizing them, even turning them into comic legacies of eighteenth-century sensibility and ressentiment.

By contrast, his “coldest-hearted misanthropes” imperil through motivelessness and gratuitous cruelty his interest in self-sacrifice and citizenship. “Disdainful of the company of his fellow-creatures,” Tom Codlin in The Old Curiosity Shop joins Ralph Nickleby in displaying a “deep misanthropy” that in Dickensian terms rules out ethical engagement with humanity.5 Although he and comparable antiheroes may refrain from extreme violence, they have little in common with Dickens’s lovelorn melancholics. Dickens downplays economic gain as a motive for their villainy, the better to magnify their commitment to personal and collective harm. As John Kucich notes, he diverts them “from an economy of purpose and reward, lifting them into a world of transcendentally profitless combat.”6 Why?

While some haters in Dickens’s work (Miss Wade, for example)7 fall between these stools, signaling the limits of Dickens’s categories, hatred of humanity recurs in his writing in psychological and nonpsychological guises, and the latter is my central concern. Such hatred tests his conception of sociability as a realm beyond which groups and communities fall apart in embitterment. Hatred in these instances doesn’t ratify society by making the exception prove the rule. As Victor Brombert argued recently, the resulting antiheroism is disturbing, because in its “willful undermining of the idiom of tragedy” it harms “our deep need to bestow dignity and beauty on human suffering.”8 “Hostile to the cult of personality,” antiheroism not only thwarts our desire for edification and perfectibility but also compels us to view suffering as a form of anguish for which there may be no meaningful answer or solution.9

Dickens used villainous misanthropes to reveal a profound discrepancy between individual drives and socially sanctioned pleasures. In particular, his interest in antiheroic characters destroys psychic and philosophical consistency by breaking with Bentham’s utilitarian model, discussed briefly in the introduction. Moving, then, from Dickensian antiheroism to the problems besetting (in ever wider circles) intersubjectivity, familial strife, and social hatred, I’ll examine his work in rough chronological order, making clear why his interest in misanthropy recast his social satires, and what is philosophically at stake in this shifting emphasis.

Instead of endorsing Bulwer’s association of misanthropy with sardonicism, Dickens unraveled this expectation, indicating that his villains finally evade such measurable principles. To that end, his “coldest-hearted” misanthropes have no redeeming qualities.10 Amoral in outlook, the cause of their hatred generally unexplained, they’re incapable of sharing the world with others, which partly defines my interest in them. Opacity also shrouds the cause of their contempt. We know only that their desire for retribution is stronger than their desire for freedom, which puts them at odds with “the calculative consistency” of utilitarianism, “the dominant ethical programme of the nineteenth century.”11 Flaunting their repugnance for personal and social reform, they override social ties with gratuitous behavior, which in turn helps Dickens offset radical evil from his lovelorn misanthropes’ harmless self-regard. Indeed, his malefactors are so devoid of conventional motivation that they become susceptible to metonymic caricature, as when Rigaud’s gestures in Little Dorrit prove absurdly artificial and Carker’s teeth designate his rapacity in Dombey and Son.

Since motiveless violence is difficult to condone, Dickens’s conception of villainy blocks identification, leaving its agents vulnerable to severe retributive impulses. For reasons that I’ll assess, given his satires of social hypocrisy, Dickens insists that such asocial behavior is irremediable and must be eliminated. Punishment isn’t enough. The violent deaths of Daniel Quilp and especially Carker—the latter’s body ripped apart by a railway train, then thrown to the winds—expunge their hostile impulses in scenes that still carefully probe their intensity.

Preceding a chapter titled “Several People Delighted …” and written with deliberate syntactical ambiguity, Carker’s death is sufficiently protracted to make him conscious of his impending agony:

[Carker] heard a shout—another—saw the face change from its vindictive passion to a faint sickness and terror—felt the earth tremble—knew in a moment that the rush was come—uttered a shriek—looked around—saw the red eyes, bleared and dim, in the daylight, close upon him—was beaten down, caught up, and whirled away upon a jagged mill, that spun him round and round, and struck him limb from limb, and licked his stream of life up with its fiery heat, and cast his mutilated fragments in the air.12

In Dickens’s moral scheme, as the passage illustrates, Fate punishes evil in a corrective impulse almost as violent as the people it eradicates. In Our Mutual Friend, indeed, we learn that “Evil often stops short at itself and dies with the doer of it; but Good, never” (105). By this sleight of hand, Dickens makes an otherwise corrosive, contaminating evil relatively self-contained, implying that it needn’t tarnish other characters or his narrators. Nevertheless, at other times he ascribed part of his own severity to “the attraction of repulsion,” an “invisible force” binding him imaginarily to not only murder and death but also the agents—Bill Sikes, Tulkinghorn, and Jonas Chuzzlewit, among them—who can’t abstain from violence.13 “Still he was not sorry,” the narrator says, recounting Jonas’s murder of Montague Tigg in Chuzzlewit. Through indirect speech and a rare moment of interiority, he establishes almost eerie familiarity with Jonas’s murderous aims: “He had hated the man too much, and had been bent, too desperately and too long, on setting himself free. If the thing could have come over again, he would have done it again. His malignant and revengeful passions were not so easily laid.”14

The narrator captures Jonas’s cruelty and contempt for old age, but avoids explaining “his malignant and revengeful passions,” leaving in doubt why they galvanize him. The same holds for all such malefactors: The real cause of their hostility recedes into elements of identity that Dickens stops short of psychologizing. First introduced to us as a form of human “vermin” (16), Rigaud seems to hate only good people. Besides noting his joy in terrifying Mrs. Flintwinch and in revenge against a society imprisoning him, we’d be pressed to explain why. Carker, too, may be repellent, and Quilp “a study in sadistic malice,” but what inspires their behavior—beyond their shared pleasure in tormenting the weak and defenseless—baffles us.15 We know only that such abusiveness must end.

The severity with which Dickens treats such violence implicates us as readers. Because Carker’s gruesome death seems meant to equal the joy he received in humiliating others, his swift punishment should satisfy readers who are “virtuously disgusted” by such antiheroes.16 Indeed, one form of relief we experience from moral corruption is the pleasure of witnessing a shoddy specimen of humanity dismembered and “cast [into] mutilated fragments.” This isn’t our sole satisfaction in completing Dombey and Son, but the narrator’s extreme description presses us to consider what it means to defeat one form of vindictive cruelty with another. Why else did witnesses at public executions cheer with approval when people hanged, as Dickens noted with alternating contempt and fascination when, in July 1840, forty thousand people (himself among them) watched the murderer François Courvoisier die?17 Why else, too, do some North Americans today follow zealously the plight of inmates on death row, counting down the final seconds of the prisoner’s life so joyfully that they might almost be ushering in a new year?

The Family of Man

Let’s return briefly to the early 1840s, though, to invoke before displacing biographical concerns. At the start of his first six-month trip to North America, in early 1842, Dickens was basking in his newfound celebrity. The ordeal of fame soon began to tell, however, as he found Americans’ aggressive interest in him intrusive and, ultimately, disgusting. He resented being an object for vast crowds, who peered at him as if he were inhuman. “If I turn into the street,” he complained to John Forster from New York, “I am followed by a multitude. If I stay at home, the house becomes, with callers, like a fair. … I go to a party in the evening, and am so inclosed [sic] and hemmed about by people, stand where I will, that I am exhausted for want of air. I dine out, and have to talk about everything, to everybody.”18

His revulsion peaked at Niagara Falls, where, instead of reading about Americans’ sense of awe in the visitors’ books, he saw comment after comment that was merely fatuous. “If I were a despot,” he wrote Charles Sumner, “I would force these Hogs to live for the rest of their lives on all Fours, and to wallow in filth expressly provided for them by Scavengers who should be maintained at the Public expence [sic]. Their drink should be the stagnant ditch, and their food the rankest garbage; and every morning they should each receive as many stripes [whippings] as there are letters in their detestable obscenities.”19

Five months after returning from North America, Dickens began Martin Chuzzlewit, a satire informed by his experiences abroad, though the novel isn’t reducible to them. Several chapters representing Tapley’s and young Martin’s episodes in America condemn the country’s obsession with money, ostentatious culture, and indifference to poverty. According to the narrator, life—especially in North America—is ruthless and deeply inhumane: “Such things [as infant mortality] are much too common to be widely known or cared for,” the narrator complains with devastating understatement. “Smart citizens grow rich, and friendless victims smart and die, and are forgotten. That is all” (601).

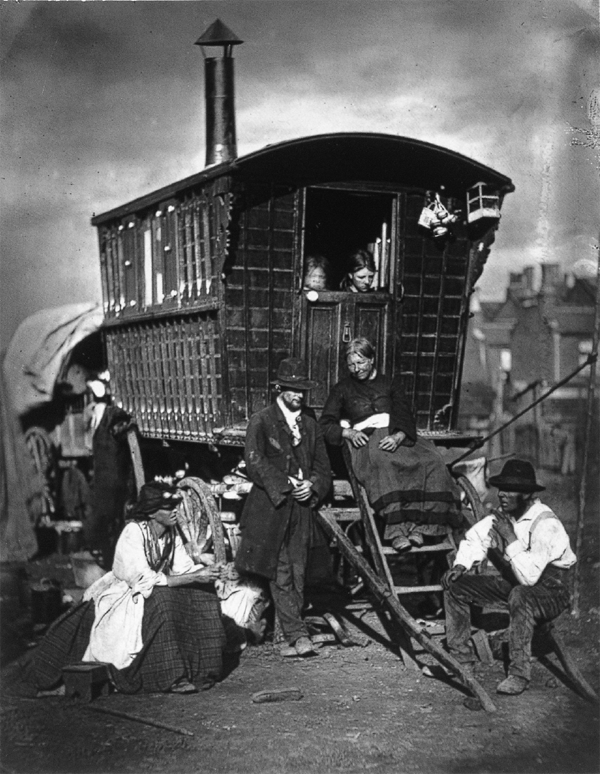

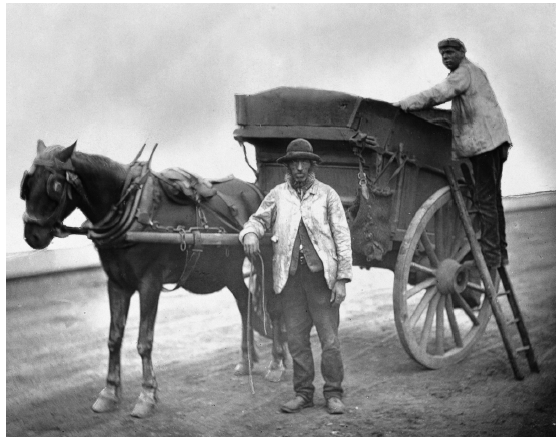

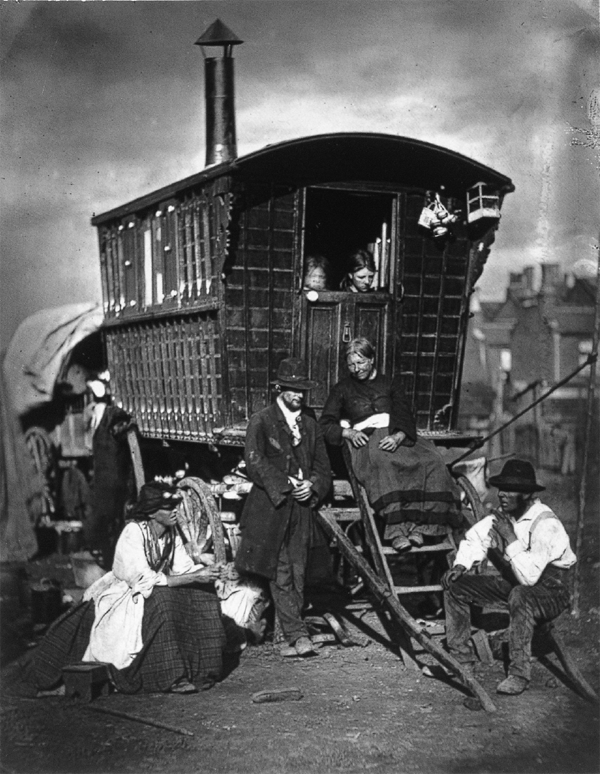

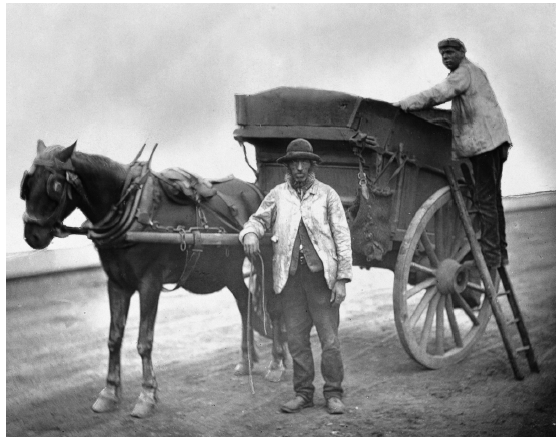

As many Britons and North Americans lived at the time in appalling conditions, with cities like London beset by overcrowding, disease, and “cess lakes,” most of these characterizations are painfully accurate. Dickens read Edwin Chadwick’s Report on the Sanitary Condition of the Labouring Population (1842) shortly after it appeared, and, like Henry Mayhew, Friedrich Engels, and Elizabeth Gaskell, confirmed its wretched summary of urban poverty whenever he visited England’s poorest slums, factories, and prisons.20 Over the course of the nineteenth century, the population of London alone swelled from roughly one million to four and a half million, while the city’s average age of mortality at midcentury fell, incredibly, to twenty-seven (twenty-two for the working classes); life expectancy in the capital—and in England and Wales generally—didn’t improve substantially until the last quarter of the nineteenth century (see FIGURES 2.1 and 2.2, respectively John Thomson’s photograph London Nomades and Gustave Doré’s study Bluegate Fields).

Since it was common for families of seven or eight to live in one room (which also doubled as a workplace for its many occupants), it was often necessary, according to a cringing inspector in 1856, that when a death occurred “the living … eat, drink and sleep beside a decomposing corpse, overheated by a fire required for cooking, and already filled with the foul emanations from the bodies of the living and their impure clothes.”21 As Peter Ackroyd asserts in his excellent biography of Dickens, “No Londoner was ever completely well, and when in nineteenth-century fiction urban life is described as ‘feverish’ it was a statement of medical fact and not a metaphor” (384).22 At the end of 1847, roughly half a million Londoners were infected with typhus fever, a figure excluding the vast number of people already dead from typhoid (a separate affliction), cholera, tuberculosis, scarlet fever, diphtheria, scrofula, and smallpox. Such was the extent of disease and poverty that Dr. Simon, working extensively to reform public health, described “swarms of men and women who have yet to learn that human beings should dwell differently from cattle—swarms to whom personal cleanliness is utterly unknown; swarms by whom delicacy and decency in their social relations are quite unconceived.”23

Dickens wasn’t referring to such “swarms” and “cattle” when he fantasized whipping North America’s human “hogs” and “fellow swine,” and I’m not reading him as a sociologist. But it’s necessary to remember this fantasy and context when we examine his satire of Victorian selfishness hobbling sociability. As he remarked in the preface to Chuzzlewit’s first cheap edition, published several years later, in 1849, the novel aims to show “how Selfishness propagates itself; and to what a grim giant it may grow, from small beginnings” (39). Like Bulwer’s, his account of antisocial behavior is also conceptual, the novel advancing a sophisticated perspective on self-regard that with devastating effect makes reciprocity and intersubjectivity almost inconceivable. This encapsulates my interest. “At every turn! … Self, self, self,” laments old Martin: “Every one among them for himself” (Chuzzlewit 868; also 95). “What is missing here, and throughout Martin Chuzzlewit for the most part,” adds J. Hillis Miller, in a brilliant reading of the novel, “is any intersubjective world. There is no world of true language, gesture, or expression which would allow the characters entrance to one another’s hearts.”24

Through its mock genealogy of the Chuzzlewits, the novel thematizes this dearth of sympathy in its opening chapter.25 Yet after a probing inquiry into murder, fraud, criminal psychology, poverty, and solipsistic hatred, the novel ends with a flood of sentiment so richly exuberant that the narrator asks six times if such joy amounts to folly. Though he considers these questions rhetorical, producing the amusingly dismissive answer—“If these be follies, then Fiery Face go on and prosper! If they be not, then Fiery Face avaunt!” (905)—is innocent pleasure sustainable when reciprocity seems constitutively impossible?

Dickens, in the early 1840s, insisted that it is. Characters like Tapley and Tom Pinch triumph over adversity, representing tenacious—if demure—examples of loyalty. Near the beginning of Chuzzlewit, the narrator even claims: “No cynic in the world, though in his hatred of its men a very griffin, could have withstood these things in Thomas Pinch” (147). He’s referring with mock-epic bathos to Tom’s incomparable satisfaction in eating a stale sandwich (the Pecksniffs’ thoughtful leftovers). Yet despite its comic aim, the statement is inaccurate, even woefully mendacious. Virtual parodies of resilient innocence, Tom and his sister—“pleasant little Ruth!”—are recipients of gratuitous abuse in a world almost indifferent to their beneficence and well-being (672). As Miller notes, they represent “the unexpected theme of the impasse to which total unselfishness leads… [:] that the man who is wholly unselfish ends with nothing but the esteem of those around him, and the privilege of serving them” (121).

Miller’s is a productively harsh way of judging such modest virtue. Despite old Martin’s triumphant restoration of order at the end, it’s wholly improbable that the simpleminded Pinches would prevail over the unscrupulous Chuzzlewits. Even John Westlock is pallid beside such scoundrels as Seth Pecksniff and Sairey Gamp, who has insight enough to insist, in these now-famous words, “we never knows wot’s hidden in each other’s hearts; and if we had glass winders there, we’d need keep the shetters up, some on us, I do assure you!” (534–35). As Gamp’s self-involvement exemplifies a type of nonreciprocity driving the novel’s moral and social vision, she compels us to reassess the characters’ presumed autonomy and capacity for intersubjectivity, a topic I shall consider as a symptom of familial and social hatred.

Aspects of this enmity survive the narrator’s final attempts at eliminating them. Indeed, the novel’s preoccupation with malice and glee remains intractable, a problem the conclusion can’t resolve. During the final cleanup, the narrator even hints that part of old Martin’s misanthropy is feigned to test his grandson’s affection for Mary Graham (888). This is a tepid explanation for the old man’s justified fury, especially when “family forces” have left him in a “state of siege” (105). What ensued was “a skirmishing, and flouting, and snapping off of heads” (106)—a type of internal corrosion stemming from rancor, to alter the metaphor, that wears away subjectivity until all that remains, as Gamp foresaw, is individuals’ petty satisfactions and cruelties.

Because it destroys meaning and symbolic relations, this depletion of subjectivity has profound antifamilial effects. In collective terms, “the family forces” eventually dissolve into a “jealous, stony-hearted, distrustful company” (107). And like Martin’s marauding relatives, Jonas waits impatiently for his father’s (Anthony’s) death. In mockery that Chuffey pretends not to hear, he voices an extraordinary hostility to old age, giving full rein to normally repressed oedipal hatred. If we considered Dickens only indignant about such cruelty (or wholly in control of his fictions’ meaning), we might call these and other scenes realizations of the common Victorian metaphor “the battle of life,” which he helped popularize.26 But as we saw earlier when invoking his “attraction [to] repulsion” and interest in executions, Dickens was captivated by the demonic energy and asocial drives fueling characters like Jonas, Krook, Headstone, and especially Quilp, so it’s necessary to consider the philosophical implications of these scenarios.27

Time and again (despite the country’s already severe mortality rates), Chuzzlewit announces that the old don’t die fast enough, as if those waiting to inherit must either pounce at the right opportunity or, in Jonas’s case, attempt patricide. According to the novel, such murderous life envy taints every generation. With remarkable candor, old Martin adds that under such circumstances the elderly are for their brethren “fit objects to be robbed and preyed upon and plotted against and adulated by any knaves, who, but for joy, would have spat upon their coffins when they died their dupes” (92). “But for joy”: These relatives are so predatory, he implies, that not even tact can veil their resentment at his protracted energy, an idea we’ll see Browning elaborate. The narrator concludes the first chapter by invoking “the Monboddo doctrine touching on the probability of the human race having once been monkeys” (56).28 But after we’ve seen the Spottletoes, Pecksniffs, and Slyme and Tigg in action, the analogy seems unfair to apes.

“Why do you talk to me of friends! Can you or anybody teach me to know who are my friends, and who my enemies?” (84). Given Martin’s assessment of his relatives, such remarks turn intergenerational hatred into a fault line splintering the Chuzzlewits’ lineage and cooling the warmth of “Fiery Face” at the novel’s end (905). As old Martin insists, again voicing the psychological cause of his misanthropy, “Brother against brother, child against parent, friends treading on the faces of friends, this is the social company by whom my way has been attended” (92).

Since the novel’s opening chapter blends satire and allegory, advancing “a kind of master-summary of the family of man,” the narrator views such treachery and parasitism as a universal tendency that society tends to encourage rather than quell.29 The Pecksniffs and Spottletoes display traits to which all humanity is susceptible, that is, but to which Victorian society, with its love of wealth and status, is especially prone. In Dickens’s representational scheme, the nineteenth century is propelled toward mutual depredation exactly as it imagines itself transcending nature entirely. If “mankind is evil in its thoughts and in its base constructions” (373), as the narrator later claims, then it’s understandable old Martin would “fle[e] from all who knew me, and taking refuge in secret places [would] live … the life of one who is hunted” (92–93). Because of his “contempt for the rabble,” the only social tie he can imagine, early on, is one in which he thwarts others’ expectations of remuneration after his death (223, 93). What he wants, paradoxically, is a consensual dearth of sympathy.

Hatred and Self-Regard

Although Chuzzlewit’s satire on selfishness compounds Dickens’s problems in concluding the novel, we can’t explain his difficulties by invoking the novel’s somewhat chaotic material (a standard criticism of the work). Nor can we follow other critics and specify the novel’s thematic problem in creating altruism out of widespread selfishness. Because the novel’s interest in self-regard shapes its overall perspective on character and intersubjectivity, it’s impossible to separate characters’ traits from their relation to society. As most of them are drawn conceptually to isolation, that is, thematic modifications, such as the removal of old Martin’s prejudice, make the narrator’s final stress on sociability unconvincing. The novel’s very structure derails that move.

Let’s approach the thematic issue, however, in order to displace it. For in doing so we’ll see how thwarted intersubjectivity in the novel becomes a powerful metaphor for wider concerns like stymied collectivity. One of the skills old Martin tries to renounce, apparently in wisdom, is reading his relatives’ unconscious motivations. In the end, he considers this scrutiny to be as selfish as the behavior it delights in exposing:

“There is a kind of selfishness,” said Martin: “I have learned it in my own experience of my own breast: which is constantly upon the watch for selfishness in others; and holding others at a distance by suspicions and distrusts, wonders why they don’t approach, and don’t confide, and calls that selfishness in them. Thus I once doubted those about me—not without reason in the beginning—and thus I once doubted you, Martin.” (884)

Superficially, this form of address—from Martin Senior to Junior—bolsters interpersonal, generational, and narrative connections, but it also severs other ties and prolongs the novel’s rancorous dynamic, for Martin’s reflection quickly swerves into a rant against Pecksniff. Because little substantively improves at the end, the novel’s rebuke to humanity—its justification for misanthropy—confirms why characters would shun one another, aspiring ideally to autarky. Having detailed such extreme hatred, the novel faces near-insurmountable difficulties in representing once-sworn enemies starting to trust one another. Interpreting an earlier moment in the novel, Miller reminds us that “most of the characters are unwilling to consider such reciprocity, and instinctively try every means they can find to do without other people” (123).

Why is this avoidance “instinctive”? By emphasizing the novel’s interest in selfishness, rather than its comparable concern about hatred, Miller surprisingly can’t say. He reads the novel’s conclusion as a gesture toward reciprocity and collective integrity, with Dickens indicting antisocial behavior. Yet, arguably, this is only half true: The novel’s focus on familial embitterment overwhelms its later stress on sympathy. Despite his brilliant reading of the novel’s dearth of intersubjectivity, then, Miller surely begins from the wrong premise. As many characters strive to avoid reciprocity, it’s hasty to imply that they’ve wanted all along to participate communally (see FIGURE 2.3). The novel disqualifies this optimism, replicating forms of violence and division even as it seems to eradicate them.

Put bluntly, Miller leaves insufficient room for the novel’s interest in disaffection. Assuming that the characters’ bids for autonomy are only briefly warranted, he supports the novel’s facile conclusion, which jars with its early pronouncements on the characters’ solipsism. Because of Dickens’s model of thwarted intersubjectivity, that is, they’re unable to form such ties, rather than merely disinclined to do so. Compare this with Miller’s point: “There is no help for it,” he claims, referring to Nadgett the spy, an early incarnation of Detective Bucket in Bleak House. “Each man must seek some kind of direct relationship to other people, a relationship which recognizes the fact of their consciousness, and makes it an integral part of the structure of his own inherence in the world” (127). The imperative in this sentence is odd, given Miller’s cogent argument, four pages earlier, about instinctive avoidance. Nevertheless, he concludes that the characters try to cultivate “authentic individuality,” healing their self-division and the community’s flagrant vices (139).

There is, I contend, “help for it,” but only if we’re prepared to view “help” as strong opposition to the noxious effects of “family forces” (Chuzzlewit 105). Impressive as a type of ideal, Miller’s argument down-plays that language and satire hamper “authentic individuality”; and he simplifies Dickens’s acute understanding of characters’ unconscious aspirations, whereby, at least in fantasy, “inherence in the world” obtains not by emulating Tom Pinch, as Miller noted, but by triumphing over one’s enemies, even shockingly—as in Jonas Chuzzlewit’s case—by trying to kill one’s father.

Let me stress, once more, that although Dickens traverses this fantasy, he doesn’t tolerate its outcome. Indeed, he condemns such extremes when he might have harnessed Jonas’s hatred by depicting milder forms of antisocial behavior. In the opening chapters of Chuzzlewit, for example, the desire for autarky is for the novel one of few viable paths to survival. Subjectivity, the narrator implies, is so precarious—so vulnerable to assault from predatory relatives—that we should view it as a defensive war against the world. According to this model, which Dickens develops in later works, antisocial sentiment is understandable, though not exactly desirable. Friendship and love occur—if at all—only after this elemental battle has taken place. The following section represents this battle by taking a brief but necessary detour through the work of Dostoyevsky, one of Dickens’s near-contemporaries and brilliant readers.

The Antihero

Though Nicholas Nickleby and The Pickwick Papers appeared in Russian in 1840 (Oliver Twist and Barnaby Rudge followed the next year, and Chuzzlewit in 1844), Dickens secured his reputation in Russia with the translation, in mid-1847, of Dombey and Son. As many critics have observed, he had a profound effect on Tolstoy, Gogol, Belinsky, and Dostoyevsky (born nine years after Dickens), who saw in his accounts of society a fascinating oscillation between restoration and disintegration.30 During the five years that Dostoyevsky spent in penal servitude in Siberia for his limited role in the Petrashevsky circle, a group comprising radical idealists opposed to the czar, he read David Copperfield and The Pickwick Papers in Russian. Twenty years later, having published The Insulted and Injured and The House of the Dead and traveled to Paris and London, he wrote Notes from Underground, often viewed simplistically as the gateway to such mature works as Crime and Punishment and The Brothers Karamazov.31

“I am a sick man. … I am a spiteful man. I am an unpleasant man.”32 With these words, Dostoyevsky’s friendless cynic recounts how, as a civil servant, he loved exhibiting “supreme nastiness” (16). “When people used to come to the desk where I sat, asking for information, I snarled at them, and was hugely delighted when I succeeded in hurting somebody’s feelings. I almost always did succeed” (15). But the narrator’s self-evaluation isn’t reliable. Apparently, he lies to us “out of spite” when supplying this opening anecdote: “I was simply playing a game with [these] callers; in reality I never could make myself malevolent” (16).

The narrator lacks the will, apparently, to retaliate when others wrong him, yet he can’t resign himself entirely to inaction. His life consists in alternately splenetic and voluptuous forms of self-torment, rendering him abject (17). Evincing a “morbid irritability” stemming partly from his unexpressed hatred of others, he “resentfully sulk[s] in the background,” seething to himself (51, 52).

Too pure a hatred of others apparently would rob Dostoyevsky’s antihero of the pleasure of self-recrimination, generating a type of grandiose contempt for others that he would find nauseating. Yet for many years he has “carried on a campaign” against an officer, an enemy he can’t intimidate. This begins one evening when the officer, finding the dejected narrator in his way, takes him by the shoulders and lifts him aside, as if he were “an insect” (52). Although the narrator claims he’s recklessly courageous, this time he is stymied, humiliated.

The resentment flourishes for want of an outlet. The narrator composes a story slandering the officer, but when a journal rejects it, the author’s “rage positively choke[s]” him (54). He writes a letter begging the officer to apologize for his rudeness, but challenging him to a duel if he refuses. The narrator tells these details self-mockingly, yet similar pique mushrooms into attempted murder in Dickens’s Our Mutual Friend, published the same year, when Eugene Wrayburn scorns Bradley Headstone’s accomplishment in becoming a teacher. Wrayburn survives Headstone’s later attempt on his life, but Headstone is so deranged by this point that he finally kills himself and Rogue Riderhood. Though Dostoyevsky’s narrator keeps a fraction more perspective, he writhes in torment whenever the officer brushes him aside. After years of self-rebuke, he exults one day when they squarely collide, the narrator refusing to yield. The officer walks on, scarcely noticing, but the narrator “return[s] home completely vindicated. I was delighted. I sang triumphant arias from Italian operas” (58).

This well-known anecdote is relevant for understanding not only Dostoyevsky’s and Dickens’s work, but also all arguments about hatred and civility in this book. As my introduction explained, the anecdote gives Dostoyevsky’s narrator a rationale for asking, “Can man’s interests be correctly calculated?” (30). After referring to such satisfactions as wealth, freedom, and prosperity, he notices that philosophers omit from consideration another impulse, a “prompting of something inside [ourselves] that is stronger than all [our] self-interest” (30).

Neglecting this satisfaction apparently nullifies the above elements of pleasure, rendering them “nothing but sophistry” (31). Indeed, in a move anticipating Freud and Jacques Lacan, the narrator highlights a form of counterintuitive enjoyment that’s satisfying in proportion to the ontological damage it causes.33 “The point is not in a play on words,” he insists, “but in the fact that this [‘irrational’] good … upset[s] all our classifications[,] … always destroying the systems established by lovers of humanity for the happiness of mankind. In short, it interferes with everything” (31).

Dostoyevsky’s interest in what “destroys” utilitarianism and related social arrangements parallels Dickens’s depsychologizing account of malefactors, twinning radical opposition to society with an equally extreme capacity for self- and collective harm. As this satisfaction has quasi-revolutionary effects in Dostoyevsky’s novella, whose punning title positions the iconoclastic and misanthropic somewhere “beneath” normalcy (podpo’lie, “underground,” can mean dissidence, shelter from social harm, and death),34 I’ll advance this parallel briefly in implicit commentary on Dickens’s contemporaneous work.

In a move influencing aspects of Western literature and philosophy, Dostoyevsky’s narrator views the decision to pursue this satisfaction as inimical to culture and custom:

It is indeed possible, and sometimes positively imperative (in my view), to act directly contrary to one’s own best interests. One’s own free and unfettered volition, one’s own caprice, however wild, one’s own fancy, inflamed sometimes to the point of madness—that is the one best and greatest good, which is never taken into consideration because it will not fit into any classification, and the omission of which always sends all systems and theories to the devil. (33–34; second emphasis mine)

In short, Dostoyevsky’s narrator establishes an ethical relation to the unconscious, which in its indifference to Victorian culture’s staid precepts frees individuals from frequently unjust social imperatives. Yet while it’s difficult to exaggerate the influence of these well-known claims on subsequent forms of nihilism, existentialism, and radical psycho-analysis,35 it’s necessary to assess the relative strength of these antisocial impulses as they recur in contemporaneous Victorian fiction. As the next two sections show, such writing may lack the philosophical clarity of Dostoyevsky’s remarkable novella, but it sometimes depicted comparable scenes and arguments with equal intensity.

Dickens and Disaffection

“I am a disappointed drudge,” explains Sydney Carton, in A Tale of Two Cities. “I care for no man on earth, and no man on earth cares for me.”36 Though lacking the edginess of Dostoyevsky’s antihero (whom he uncannily echoes), Dickens’s protagonist points similarly to a gap between individual drives and socially sanctioned pleasures, such that the former exceed the latter, leaking into more-complex terrain. For much of the novel Carton is almost immobilized by ennui, his nightly drinking confirming an apparently unshakable morbidity. Love for Lucie Manette shatters his complacency, generating a desire for self-sacrifice, but under conditions that ordinarily would spawn greater futility: She’s all but engaged to Charles Darnay, whom she eventually marries. Instead of despairing that his love is largely unrequited, however, Carton awaits a chance to confirm Lucie’s estimation of him. The moment comes when, resembling the imprisoned Darnay, he substitutes himself for the condemned man and sacrifices himself in what Dickens calls “an act of divine justice.”37

Although A Tale portrays this moment as valiant, my summary of the novel highlights a psychological paradox that other works by Dickens—chiefly Chuzzlewit and Our Mutual Friend—put more skeptically. Love in A Tale is more an extension of egoism than a means of voiding it. The pleasure of self-sacrifice is necessarily—though not exclusively—self-serving. Carton doubtless secures an honorable reputation for posterity and makes an undeniable difference to Darnay and Lucie, but as he’s “half in love with easeful Death,” in Keats’s phrase, Lucie is partly a sublime means of fulfilling his destiny.38 In this ambiguous light, she’s a prop for a mission half perceived—Carton’s well-documented desire for self-dissolution—rather than a means of aborting his purposelessness. “I have had unformed ideas of striving afresh, beginning anew, shaking off sloth and sensuality, and fighting out the abandoned fight,” he tells her in a crucial passage. Yet even here his language is ambiguous, signaling a desire to break with the past (“beginning anew”) by reconnecting with some unfinished business (“fighting out the abandoned fight”).

“A dream, all a dream,” he continues, “that ends in nothing, and leaves the sleeper where he lay down, but I wish you to know that you inspired it” (181). Unlike Macbeth, whom he partly echoes, Carton finds peace, not anguish, in annihilation. Since we can’t isolate his drive to sympathy from this “dream,” the material effects of sacrifice increase, rather than diminish, the satisfaction of the internal drama. Elements of Carton’s altruism paradoxically extend his preexisting illusion, whereas the gratuitous rage of a character like Ralph Nickleby almost could succeed, in the earlier novel, in destroying this fantasy.

As at the end of Chuzzlewit, Dickens and many of his critics would defend Carton’s illusion. Indeed, because the latter’s self-sacrifice touches on heroism, it might seem wrongheaded to hint that a preceding commitment to death tarnishes valor with suicide. Still, Carton’s—and the novel’s—final words are inconclusive, binding with a semicolon two statements answering related but nonidentical aims (sacrifice and self-dissolution): “It is a far, far better thing that I do, than I have ever done; it is a far, far better rest that I go to than I have ever known” (404).

Starker outcomes in other Dickens novels implicitly comment on these permutations. In Great Expectations, Bentley Drummle’s diffidence to humanity is in most respects identical to Carton’s. Pip calls him “a sulky kind of fellow … proud, niggardly, reserved, and suspicious” (192, 203). Drummle exemplifies what I would call an aversion to—or even nondisposition for—sociability that runs throughout Dickens’s work, which characters can’t overcome by fiat. Accordingly, Drummle slinks around as if he were subhuman, even prehistoric:

He would always creep inshore like some uncomfortable amphibious creature, even when the tide would have sent him fast upon his way; and I always think of him as coming after us in the dark or by the back-water, when our own two boats were breaking the sunset or the moonlight in mid-stream. (203)

The analogy isn’t gratuitous, as Drummle does indeed haunt Pip and menace his dreams. Winning the support of Jaggers, who christens him “the Spider,” he marries Estella, casting both in marital hell until he’s killed flogging a horse. But as Drummle temperamentally has much in common with Carton—for long stretches of time, both live under a “cloud of caring for nothing” (A Tale 179)—why does Dickens give them such different fates? Owing to their resemblance, Drummle might (like Carton) have found salvation in self-sacrifice; and Carton (like Drummle) could easily have maintained “a fixed despair of himself,” remaining “silent and sullen and hang-dog” (180, 169). These comparisons point to a chiasmus in Dickens’s work, extending the distinction in Barnaby Rudge between sentimental misanthropes and those whose hatred pushes them beyond redemption. Carton’s misery opens a saving path to sympathy that Drummle’s torment disables, even voids. Dickens intriguingly makes misanthropy worthy of sympathy in A Tale, but a precursor to complete embitterment and death in Great Expectations. As in previous works, then, but especially at this moment in his literary career, misanthropy is central to his fiction and its underlying philosophy, representing the fulcrum on which his conception of sociability turns.

Leaving Society

Although the passage from Barnaby Rudge with which I began this chapter underscores the importance of this fulcrum as Dickens established his career, hatred’s effect on his communitarian spirit intensified in scope, shifting from lovelorn misanthropes, such as Carton, to “cold…-hearted” antiheroes like Drummle. In even later works, however, Dickens continued representing characters that hate humanity, but (in ways resembling Bulwer) tipped the emphasis toward wholesale indictments of societies, as corrupt forces violently overwhelm his solitary misfits.

As we saw earlier, signs of this tension appear in Martin Chuzzlewit and recur prominently in the later Bleak House, given Tulkinghorn’s temperamental differences with the aptly named Lawrence Boythorn. But the tipping point in Dickens’s fiction arguably is on the cusp of the 1850s and 1860s, when he published A Tale of Two Cities and Great Expectations. Hence, in the 1858 short story “Going into Society,” a character’s querulous relation to society finally devolves into a powerful narrative indictment of the latter. Though Chopski (Major Tpschoffki), an ambitious dwarf, tries entering “select” London Society to pass among the wealthy, his plans come to nothing: soon destitute, his fortune stolen, he returns to his former life “soured by his misfortuns [sic].”39 According to him, Society performs the same circus tricks that he once cultivated, and knowing this brings his disaffection close to misanthropy: “They’ll drill holes in your ’art, Magsman, like a Cullender,” he tells his interlocutor, “and leave you to have your bones picked dry by Wultures, like the dead Wild Ass of the Prairies that you deserve to be!” (229–30).

Given its ambivalence about society—set off by Chopski’s pun on art and heart—the story is also a precursor to Our Mutual Friend, a novel that in this respect is really Dickens’s darkest work and crowning achievement.40 The Veneerings, Podsnaps, and especially the Lammles epitomize the circus act that Chops dismisses. They’re also endless recipients of Dickens’s narrative contempt: Mrs. Podsnap displays a “quantity of bone, neck and nostrils like a rocking-horse,” and Lady Tippins’s throat has a “certain yellow play” that resembles “the legs of scratching poultry” (21, 23).

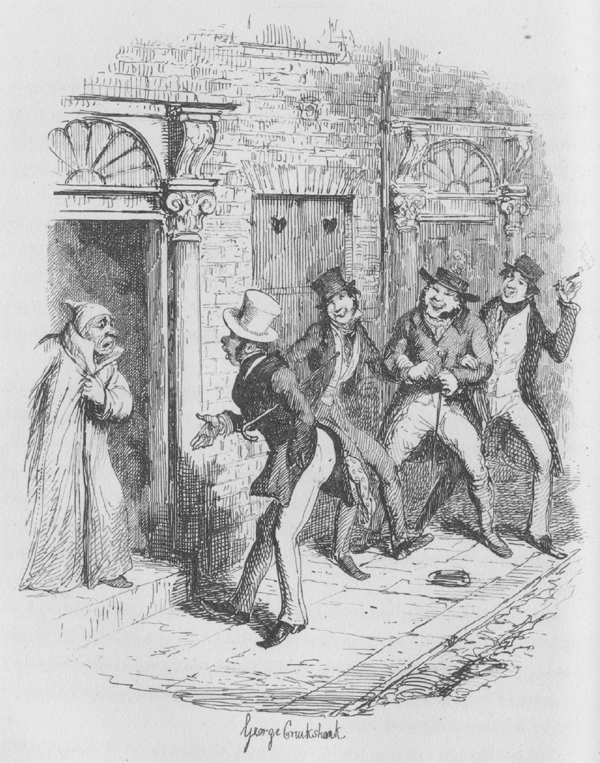

These de-anthropomorphizing comparisons recur throughout the novel, recalling earlier allusions to human vermin, cattle, hogs, monkeys, and spiders. Reversing the position of men and animals relative to culture and nature, such comparisons also gnaw at dignity. Whereas Dickens’s early illustrator and (generally) close friend Cruikshank presented Victorian society as benign, industrious, and well regulated in his “British Bee Hive” (discussed in the introduction), his own analogies in Our Mutual Friend are consistently degrading. Comparing a “perfect piece of evil” like Rogue Riderhood to “a roused bird of prey,” the novel tirelessly displays what is “half savage” about humanity (358, 14, 13).41 Indeed, these comparisons are so noticeable—and unflattering—that one of Dickens’s own characters alludes to them, as if imitating readerly discomfort, and recommends that they cease (98). They don’t.

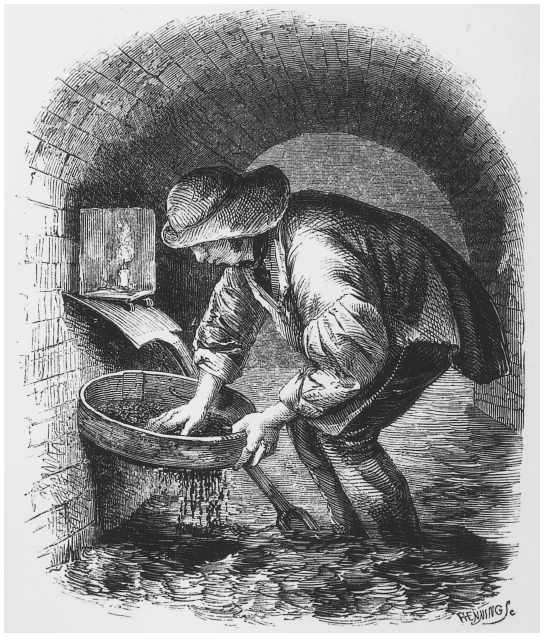

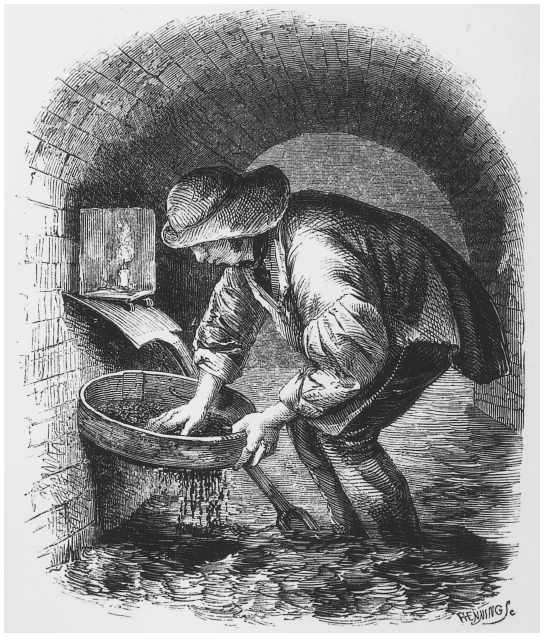

As these descriptions surpass the novel’s real and false aristocracy, Dickens’s satire of “Society” frequently balloons into a bitter indictment of all communities. When for instance Lightwood and Wrayburn visit London’s Docklands to identify the drowned body of ostensibly John Harmon (actually George Radfoot), they pass “where accumulated scum of humanity seemed to be washed from higher grounds, like so much moral sewage, … pausing until its own weight forced it over the bank and sunk it in the river” (30). While the anger in this passage is unmistakable, its source is unclear (see FIGURE 2.4, a sketch adapting Richard Beard’s daguerreotype The Sewer-Hunter). The judgment rests with the collective subject of “seemed,” which potentially embraces the two diffident gentlemen, the “Society” with which they’re often reluctantly associated, and even the narrator. The point is, we cannot be sure.

This generalized hostility may explain the narrator’s allusions to “us smaller vermin” and the “crawling, creeping, fluttering, and buzzing creatures, attracted by the gold dust” of Noddy Boffin (118, 208). But the object to which vermin once referred (a villain like Rigaud) now refers to society in its entirety. Indeed, the ensuing elemental bestiary in Our Mutual Friend lies broadly between humanity and dust, the latter being in two senses the goal of life, as the novel reminds us with devastating irony. So, despite the narrator’s bid to clean up—and even sublimate—Harmon’s Dust Mounds, his preoccupation with slime, waste, and death helps erode an early nineteenth-century belief in perfectibility (see FIGURE 2.5, Thomson’s photograph Flying Dustmen). Though it voices contempt for Wrayburn’s eventual marriage to Lizzie Hexam, “Society” gorges on what Boffin’s workers recover from old Harmon’s Mounds.

Underscoring the irony of this perverse ecology, Our Mutual Friend forges a partnership of sorts between Mr. Venus and Silas Wegg, one of its antiheroes. Wegg is perhaps best known for combining egregious disloyalty with easy familiarity, even condescension, toward perfect strangers. Yet since his treachery fuses an impulse to appropriate others’ lives (self-aggrandizement shielding him from recognition of his pathetic stature), his anticommunitarianism is more complicated than Quilp’s or Rigaud’s. Better integrated into society, he nicely represents its shameless duplicity and dark “plotting” (187).

Most characters in the novel are either as opportunistic as Wegg or as desultory as Venus—indeed, by the end misanthropy tarnishes almost everyone but the novel’s now reformed “harmless misanthrope” (297). Lizzie and Harmon go separately into hiding, the latter holding exemplary status as a wandering Cain, less despite than because of his innocence. “I have no clue to the scene of my death,” he tells himself in a remarkable passage; a “spirit that was once a man could hardly feel stranger or lonelier, going unrecognized among mankind, than I feel” (360). The narrator calls this “communing with himself,” something other characters do, often unconsciously, at moments of profound despair and vulnerability (367). Besides Harmon’s eventual marriage to Bella, and Wrayburn and Lizzie’s concluding love, this may be, remarkably, the closest the novel comes to nonantagonistic intimacy.

When Charley Hexam threatens to betray Headstone to the police, as well, a “desolate air of utter and complete loneliness [falls] upon [the latter], like a visible shade” (692). Notwithstanding Wrayburn’s joy in goading him, an internal voice exacerbates Headstone’s murderous consciousness more effectively than could any legal authority. Apparently, Headstone “irritated [his condition], with a kind of perverse pleasure akin to that which a sick man sometimes has in irritating a wound upon his body” (535). Such Dostoyevskian insights recur frequently in the novel, underscoring Dickens’s break with Bentham, for whom psychic negativity was illogical and socially irresponsible. Moreover, despite his solitary existence as a reclusive lock-keeper, Riderhood paradoxically is anything but alone. When asleep, he experiences “an angry stare and growl, as if, in the absence of any one else, he had aggressive inclinations towards himself” (617).42 These inclinations surpass extreme guilt and self-recrimination, and thus—as I argued earlier—conventional forms of psychology, the narrator emphasizing that “nothing in nature tapped” this character (617). Still, remarkably, when Riderhood is brought back from the brink of death, the narrator calls his resistance to life unexceptional. “Like us all, every day of our lives when we wake,” the narrator admits, “he is instinctively unwilling to be restored to the consciousness of this existence, and would be left dormant, if he could” (440). Our commitment to death and contempt for consciousness are stronger than our interest in life (an idea Browning develops), and this outcome collapses most ontological distinctions between Dickens’s “waterside character” and us. Self-extinction may be our ultimate goal, but even paltry company in this novel is preferable to facing our conscience. Society, however, has other concerns.

Our Mutual Friend’s most thoughtful sign of this tension is so subtle it’s likely to wrong-foot us: Wrayburn realizes that his marriage to Lizzie is incompatible with his continuing participation in Society.43 Although his choosing love would bolster sentiment in an earlier Dickens novel, Wrayburn makes this decision solemnly, weighing and then rejecting what membership in Society entails. Considering the novel’s interest in ubiquitous hatred, significantly neither its antihero nor its reformed misanthrope voices the intelligent disdain concluding Dickens’s last complete novel; instead, one of its erstwhile citizens does so. “But it cannot have been Society that disturbed you,” Lizzie cautions. Wrayburn gently corrects her: “I rather think it was Society though!” (792).