WHEN I BEGAN WRITING THIS BOOK, actors appeared nightly on U.S. television, warning viewers that hateful thoughts could lead to hate crimes, “so watch what you say. Hate destroys.”1 Advertisements flooded network television, offering Paxil (paroxetine hydrochloride) to an estimated ten million Americans experiencing “social anxiety disorder” (SAD).2 And a team of psychiatrists in California announced that Samson, the biblical figure, may have suffered from “antisocial personality disorder” (ASPD).3 This seemed fitting, if scarcely plausible, when they added that generalized anxiety disorder “afflicts more than one-half the general [U.S.] population.” The psychiatrists doubtless boosted that figure by including as examples of social phobia fears about eating alone in restaurants, writing in public, and using public rest rooms.4

A staple of American life before the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, these claims flourished while Americans enjoyed the longest period of peace and prosperity in more than two generations. Polled in December 1997, however, 57 percent of them believed that “the people running the country don’t really care what happens to you.”5 If we can trust that figure, then collective happiness is neither a simple nor a logical effect of social harmony and increased wealth. Indeed, that greater prosperity can magnify incivility is a problem for politicians, cultural theorists, and writers tackling the social scene.

Journalists and scholars have made similar claims on the other side of the Atlantic, the principal focus of this book. In the British political magazine Prospect, expatriate Michael Elliott recently accused “Rude Britannia” of becoming “rougher as it gets richer” and of turning “incivility” into “a real social problem.”6 Although Elliott blamed both outcomes on the collapse of Britain’s empire and the country’s “modernisation and liberalisation,” he conceded that “it’s easier to dislike anti-social behaviour than to measure its impact; and it’s easier to do either of those than to figure out how to persuade people to behave better.”7 Elliott didn’t view the demand for “satisfactory adjustment to society” as a problem in its own right, yet one dictionary now defines this adjustment as a condition of mental health. The same dictionary glosses normal, tendentiously, as “free from any mental disorder.”8 Given the above percentages about generalized anxiety, presumably this last definition is rather optimistic.

Let me stress at the outset: This book doesn’t try to persuade people to behave better. It admits the difficulty of measuring, much less diminishing, antisocial behavior. And it shows that incivility predates the collapse of Britain’s empire, filling the very works of Victorian fiction and nonfiction that many still view as morally exemplary. Dickens’s Our Mutual Friend, Eliot’s Daniel Deronda, and Trollope’s The Way We Live Now—just three of many exceptions to popular characterizations of the Victorians today—don’t merely caution readers to settle for less while urging them to treat their spouses, neighbors, and relatives better. All three works advance bleaker explanations for rancor. Often deriving more pleasure from discord than from harmony, their characters view neighbors as severe obstacles to happiness and fulfillment. Allegedly schooling readers in good manners, these novels actually portray hatred in nearly insoluble forms. In this book I examine the resulting tension, calling it systemic, because it stems from impulses, emotions, and forms of rebellion that society can’t integrate. I also challenge the myth that nineteenth-century England was simply a breeding ground for today’s precarious civility. Indeed, if understanding antisocial behavior in contemporary Britain and the United States is truly our goal, then rereading Victorian fiction would be a good place to start.

Received wisdom about Victorian culture has, I think, blinded us to the range and intensity of its antisocial dynamics, including the cultural prevalence of acute misanthropy and schadenfreude (joy in another’s sorrow). Hatred and Civility unmasks these dynamics, eliciting their disruptive energy in readings of Victorian novels, plays, poetry, and journalism, as well as sermons, philosophical essays, and medical tracts. Granted, some scholars before me (Peter Gay, Daniel Karlin, and Victor Brombert among them) have complicated others’ widespread assumptions that the Victorians were essentially charitable and genial, but I approach these and related issues from a different perspective, asking why the Victorians blamed misanthropes in particular for betraying a set of values that many ordinary citizens found unsustainable. Given the severity of this blame, it is all the more ironic that narrow assumptions about Victorian morality recur in contemporary Britain and North America as an ideal by which both societies are measured and found deficient. Victorian scholars may dismiss these assumptions, calling their suggestion of “manners and morals” inaccurate and prim, but that doesn’t alter popular judgments about the nineteenth century, which stoke powerful arguments today about the family and “traditional values.”

Consider a recent example of this evaluative struggle—the art exhibition “Exposed: The Victorian Nude,” which showed at the Tate Gallery, London, in 2001 and, for several months in 2002, at the Haus der Kunst, Munich, and the Brooklyn Museum of Art. What was striking about the exhibition’s mixed reviews was not the critics’ polar assessments of the art’s aesthetic merits, which in today’s climate are quite predictable, but the service to which those assessments were put. Writing in London’s New Statesman, Eliot biographer Kathryn Hughes applauded the exhibition’s “cogent” arrangement but criticized it for appealing to outmoded stereotypes about the Victorians. “When it comes to titling anything to do with the Victorians,” she observed, “there is a tiresome tendency to lean on the image of dark secrets being brought to the surface,” a tendency that the word exposed seems to confirm.9 Instead, the New Statesman subtitled the review “Kathryn Hughes Finds That the Victorians Differed Little from Us in Their Response to Nudity,” a tack that Matthew Sweet also adopted in his recent study, Inventing the Victorians.10 In “Undressing the Victorians,” by contrast, art historian and conservative critic Roger Kimball tries to keep the Victorians mysterious and foreign, and thus balks at material hinting at their and our shared interest in nudity. He begins his review for the New Criterion with an epigraph from Burke’s “Letters on a Regicide Peace”: “Manners are of more importance than law,” then complains that the exhibition’s very rationale means “yet another chapter in the so-called culture wars,” a chapter he views as “a battle about everything the Victorians are famous for: … cleanliness, hard work, strict self-discipline, etc.”11 “The assembled works of art,” Kimball intones, “provide the excuse to fight some contemporary ideological battles: battles about the place of sexuality in public life, the ideals of modesty and seemliness, the concept of sexual normality.”12

The empirical evidence that Kimball saw clearly did nothing to dislodge this assessment, and the military rhetoric shaping his judgment allegedly does nothing, in turn, to up the ante. Still, Hughes and Kimball agree, from very different perspectives, that at stake in such evaluations is nothing less than our entire conception of the Victorians. Scholars no longer can afford to ignore this yawning gulf in Victorian studies or the canards that shape it. If I begin by tackling such resilient assessments of Victorian culture and society, it’s to expose the half-truths that they veil. Kimball might in fact recall Walter Houghton’s chastening, if rather broad, indictment of Victorian hypocrisy, in his now classic study The Victorian Frame of Mind: “The Victorians … pretended to be better than they were. They passed themselves off as being incredibly pious and moral; they talked noble sentiments and lived—quite otherwise.”13

Arguments about civility or sociability did not, we’ll see, emerge in the nineteenth century independent of a wide body of literature highlighting the lively hostile impulses an individual should aspire to control. Yet hatred and repression also did not coexist in anything like a simple cause-effect relation—an idea leading many to champion repression as a way to eliminate these tensions or to put them to fresh use. Arguments like these not only imply that literature and art sublimate such emotions, promoting only sociability, but also downplay the kinds of struggle that precede narrative or poetic closure, including the upheaval awaiting readers disturbed by their excited response to dramatized hostility. Claiming that culture teaches us to thwart unruly passions, moreover, ignores that collective judgments—especially in late-Victorian fiction—often are injurious to individuals and foster outrage at social hypocrisy, double standards, and punitive rectitude. Above all, these works often entertain readers with outlandish scenarios giving antisocial behavior a thrilling, if vicarious, emancipatory appeal. That such excitement may occur at the expense of other parties may be unpleasant, even unethical, but that these scenarios are fictional shouldn’t blind us to their exhilarating effects. What’s striking about Victorian fiction, as will emerge, is less its moral didacticism than its willingness to let hatred and civility collide in Jekyll-and-Hyde fashion—often at the expense of sociability and similar ideals.

In Robert Louis Stevenson’s enormously popular novel, for example, Henry Jekyll describes his asocial counterpart, Edward Hyde, as “a being inherently malign and villainous,” whose “soul boil[ed] with causeless hatreds.”14 Hyde’s demonic rage and blithe capacity for murder clearly push us beyond the realm of misanthropy, yet it’s a mistake to attribute unwavering civility to Dr. Jekyll. As he acknowledges, the being that “shook the very fortress of [his] identity” isn’t separate but something emanating from him that generates “perennial war” in his consciousness (57, 55). “I was radically both,” he admits of a creature reveling in “ape-like spite” (56, 70). “This, too, was myself” (58).

Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde is doubtless the best-known account of acute hatred and doubtful civility in Victorian literature, but its willingness to ascribe these extremes to a transforming powder, and to eliminate them with Jekyll’s suicide, skews a fascinating conflict in less extravagant works. The novel’s ending lets Victorian and contemporary readers imagine that the “perennial war” it stages is soluble and normally invisible, rather than one that, to a much lesser degree, afflicts us all. No society can tolerate the full expression of every impulse, hostile or murderous, crossing the minds of its diverse citizenry. What, though, of works that voice this hostility in less egregious forms?

“Other people are quite dreadful,” sniffs Lord Goring in Wilde’s An Ideal Husband. “The only possible society is oneself.”15 First performed in January 1895, three months before Wilde’s first trial over accusations of “gross indecency,” his play is a deft commentary on sanctimony. Doubtless, Goring’s claim provoked as many Victorians to laughter as to anger, but in doing so it tested the bounds of credible sociability. How would a modern Goring or his author view today’s sociopolitical climate, a time of anthrax, enemy combatants, and terrorists in our midst? Strange to say, the question presses our faith in Victorian values and sociability. As Felice Charmond cries in Hardy’s Woodlanders, “The terrible insistencies of society—how severe they are, and cold, and inexorable. … Oh! why were we given hungry hearts and wild desires if we have to live in a world like this?”16 Her question accents a tension between social control and individual satisfaction, indicating that Victorian society is to her more a cause of misery than a means of alleviating it. Tired of society’s “terrible insistencies”—its corruption, inequality, and relentless pressures—many today would voice harsher indictments of this entity.17

What, then, do we owe our friends and neighbors, to say nothing of complete strangers? What is required of us, as distinct from what we choose to give?18 These earnest questions may first engage duty, morality, and altruism, but accompanying and undercutting them is the equivalent of Don Juan’s infamous suggestion, in Byron’s poem, that “hatred is by far [our] longest pleasure; / Men love in haste, but they detest at leisure.”19 Given the Victorians’ hope of finding societal explanations for good and evil, we must raise these questions when reading their works, and it’s useful to imagine their most gifted thinkers asking us the same thing.

In A Dream of John Ball, William Morris says “fellowship is heaven, and lack of fellowship is hell: fellowship is life, and lack of fellowship is death.”20 Shunning the “vapour-bath of hurried and discontented humanity,” his metaphor for urban life, Morris summed up his predicament in 1894, two years before he died: “Apart from the desire to produce beautiful things, the leading passion of my life has been and is hatred of modern civilization.”21 Believing himself “born out of his due time,” Morris found happiness evoking life five centuries earlier, in medieval England.22 But while he and other Victorians earnestly practiced the biblical injunction “Love thy neighbor as thyself,” an injunction that Morris could reconcile with his socialist beliefs, many other nineteenth-century works voice a different message: Fear—sometimes hate—thy neighbor.

One reason this aspect of Victorian culture remains underexplored is because misanthropes—once prized for their integrity and disdain for humanity’s worst excesses—came to appear immoral, degenerate, and even quasi-criminal. As my introduction explains in some detail, the evolution of this judgment in the nineteenth century highlights the changing role of communities in deciding who belongs, who doesn’t, and why. Exposed at such moments is the barely veiled underside of better-known claims about positivism and communitarianism—the assumptions that humanity is inching toward perfectibility and that society is the best means of ensuring this outcome. Because the resulting thematic collision stems from a structural difficulty, moreover, it can’t be remedied by murdering villains, dissolving a character’s egoism, or creating conditions that demand greater altruism—stock remedies in Victorian fiction that the major writers examined here quickly left behind. That is why this book examines complex issues like “surplus” enmity, failures of sociability, ties between narration and hostility, and the kinds of antisocial impulses that, for Dickens, Browning, and Conrad, push their characters from conventional psychology to eschatology. These writers helped fashion a move from self-responsibility to interest in the limits and extinction of personality, the threat of asocial drives, and the duplicity that illusions of civility can mask.

“Victorian misanthropy” is thus a protean term, and leading literary and philosophical works conclude differently about how to define it. This makes it difficult to give one account of hatred in the nineteenth century; we must consult more sources and juggle varied, sometimes contradictory perspectives. Neither the Victorians nor scholars today can say with certainty that misanthropes are petty but not wise, mean rather than charitable. As an unnamed character declares in Dostoyevsky’s Brothers Karamazov: “The more I love mankind in general, the less I love human beings in particular.”23 In “compensating” for the apparent imbalance, he clings to an ideal love of humanity but finds it impossible to love individuals a fraction more: “The more I … hated human beings in particular, the more ardent has become my love for mankind in general” (62). Posing difficulties for social theorists and visionaries, such paradoxes are difficult to interpret without importing preexisting assumptions from psychology, sociology, and philosophy (especially communitarianism, old and new). Still, theorists in these disciplines often skirt those paradoxes, hoping less to tolerate misanthropy and antisocial behavior than to explain them away. To understand misanthropy in all its complexity, we must therefore turn to literature, which recasts social issues in imaginative ways and lets responsibility take a backseat to representation.

The word misanthropy stems from the Greek misánthropos (misein, to hate + anthropos, man). Although the Oxford English Dictionary defines this noun as simply “hatred of mankind,” it lists five different uses of the word, ranging from “bad opinions of mankind” (James Harris’s 1781 Philological Inquiries) to the “revenge” we take on humanity “for fancied wrongs it has inflicted on us” (William Alger’s 1867 meditations The Solitudes of Nature and of Man).24 Since the Middle Ages, moreover, the verb to hate has supported both “strong” and “weak” definitions: “to hold in very strong dislike; to detest; to bear malice to,” and a second, milder response: “to dislike greatly, be extremely averse (to do something)” (OED 7:6). While the Victorians generally coupled misanthropes with the first definition of hate, thereby associating their hatred with “very strong dislike” and “malice,” subtle variations in how and why they hated make interpretation pressing but difficult. As the OED’s examples show, the Victorians and their forebears could employ hate imprecisely, and they sometimes turned misanthropy into a synonym for enmity, rancor, and antipathy—emotions whose object ordinarily wouldn’t encompass all humanity.

When using these terms interchangeably, however, most Victorians took for granted hatred’s pathological status, which therefore exacerbated the condition of misanthropes. Compelled to socialize, pressured into thinking more than their forebears were that companionship is healthy, misanthropes at the time faced a bitter irony: the expectation that a social answer would dispel their problems. As Carlyle insisted in “Characteristics,” “Society is the genial element wherein [man’s] nature first lives and grows; the solitary man were but a small portion of himself and must continue for ever folded in, stunted, and only half alive.”25 A few pages later, in a voice for which he’s better known, he nonetheless praises solitude by lamenting the height to which “the dyspepsia of Society [has] reached; as indeed the constant grinding internal pain, or from time to time the mad spasmodic throes, of all Society … too mournfully indicate.”26

As such ambiguous statements imply, my title Hatred and Civility is not contradictory. Nor does it blame nineteenth-century intellectuals—Carlyle among them—for believing citizens should strive for collective fulfillment. Instead it highlights the partial collapse of this ideal in literature, as well as the persistence of so-called irrational hatred in Victorian fiction and society, which generates antisocial perspectives and, occasionally, full-blown misanthropy. The result corrects our misshapen idea of the Victorians, describing a significant historical, cultural, and ethical shift in what sociability at the time meant and entailed. Hatred and Civility shows what happened when the Victorians’ faith in community buckled under the pressure of sustaining fellow feeling, letting more intemperate emotions emerge.

The nineteenth century offers so many examples of hatred that the first question any critic faces is what to leave out. Although discussion of these subjects in French, German, Russian, and North American cultures would generate several books, I interpret this material only when it has a clear relation to hatred and misanthropy in nineteenth-century Britain. For example, my chapter on Dickens includes a brief section on Dostoyevsky’s Notes from Underground, because the latter is central to accounts of hatred burgeoning at the time, and Dickens almost certainly influenced Dostoyevsky’s work. Additionally, many late-Victorian writers (including Stevenson, Gissing, and Wilde) considered Dostoyevsky an important antecedent, and for good reason.

Although my interest is British hatred in general and misanthropy in particular, I acknowledge that these phenomena are distinct in scope and style. Characters hate humanity in the works I examine; societies display acute forms of cruelty and violence. Of course, the wealth of available material means that no one could give an exhaustive account of British writers interested in these interrelated topics. Still, readers may be surprised that Hardy, despite his prominent disdain for “madding crowds” and “shoddy humanity,” isn’t a player here.27 Though he took a dim view of humanity, Hardy wrote parables about social bigotry rather than justified misanthropy.

Consider the poem “In a Wood,” composed as he was reading articles on Arthur Schopenhauer and Eduard von Hartmann, and discovering French impressionist painting. In the poem’s opening stanza, the speaker asks broadly, rhetorically,

When the rains skim and skip,

Why mar sweet comradeship,

Blighting with poison-drip

Neighbourly spray?

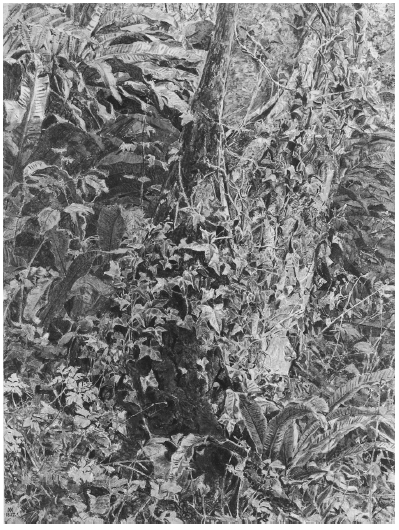

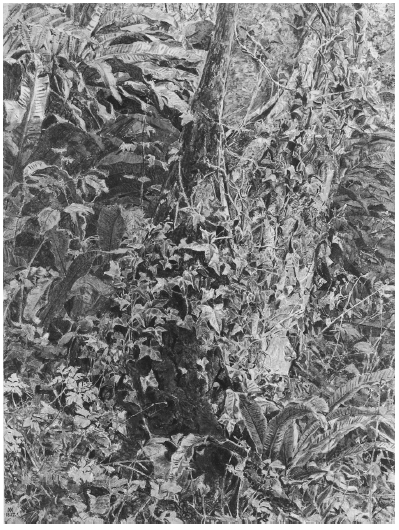

“Heart-halt and spirit-lame,” he looks for peace in a remote wood, only to unearth a Darwinian nightmare in which anthropomorphized trees are “combatants all!,” destroying one another as they compete for light and space. Rank and embattled vegetation certainly were recurring motifs in midcentury art and photography, roughly two decades before Hardy wrote his poem, and in Albert Moore’s watercolor Trunk of an Ash Tree with Ivy (1857) and John Dillwyn Llewelyn’s photograph Lastrea Filix Mas (c. 1854), the artists’ fascination with decay hovers between delight and hints of menace (FIGURE 0.1 and 0.2). But while his Romantic spirit is similarly crushed, Hardy’s speaker describes additional alienation from humanity and language—a common lament in Victorian poetry. Longing for solace, he turns “back to my kind,” grudgingly conceding that there “now and then, are found / Lifeloyalties.”28 The passive voice in this clause makes clear that from the speaker’s perspective, loyalty arrives by chance, not design. Many other passages in Hardy’s work display similar concerns, often with gloomier conclusions: “Done because we are too menny [sic]” is the plaintive explanation young Father Time gives for hanging his sister, baby brother, and himself near the end of Hardy’s last novel, Jude the Obscure.29

Other, obvious candidates for inclusion in this book include Thackeray, Arnold, and Carlyle. The first (despite his middle name, Makepeace) was notorious for ridiculing his rivals while condemning the misanthropy of others, like Swift; the second was renowned for his fear of mobs and fascination with solitude;30 the third, infamous for railing against greed and stupidity. The number of other texts worth discussing is vast, including Disraeli’s early fiction; Morris’s and James Thomson’s horror of urban humanity in, respectively, The Pilgrims of Hope and The City of Dreadful Night; and Meredith’s and H. G. Wells’s late work, especially Wells’s Mind at the End of Its Tether. While researching this book, I also read a large number of articles on hermits, eremites, misers, and crowds—most dating from the 1850s and 1860s. Such topics merely touch on hatred and misanthropy but raise a host of related questions about political reform and religious debate to which an encyclopedic approach could only begin to do full justice.31 Clearly, the list of possible works to engage could go on and on, but as brevity and space require a focused approach, these topics and figures generally appear in my notes only.

This book, then, is neither a sociological nor an exclusively historical account of hatred in Victorian Britain, and its emphasis isn’t reducible to psychological and biographical concerns. My primary goal is not to unearth links between fictional accounts of hatred and authorial sadism, or to view fiction as a means of restraining readers’ malice by venting before curbing our schadenfreude. Instead, I take a different tack, asking why readers gloat when characters we’re encouraged to revile suffer and even die. What “providential” design secures in Victorian fiction a form of justice that life at the time so often denied? Dickens and Browning pursued these questions with keen intelligence, Browning in particular forging a style that’s faithful to poetic, not political, justice. In comparison with other Victorian works, book 11 of his Ring and the Book arguably is unsurpassed in highlighting the pleasure of vengeance blind to its own self-defeating consequences. The result isn’t quite cathartic, as I explain more fully in chapter 5. Judging pleasure a zero-sum element, Browning provokes, rather than diminishes, the full poetic power of schadenfreude.

These revenge scenarios may be deeply satisfying (Carker’s grisly death in Dickens’s Dombey and Son and Baldassarre’s long-awaited retribution in Eliot’s Romola are other examples that I consider), but they blur the line between misanthropy and villainy. Although villains conventionally harm specific targets and misanthropes’ ubiquitous hatred often helps them abstain from violence, hatred itself can corrupt or dissolve these comforting distinctions. Is Baldassarre untainted by misanthropy when soliloquizing, “I am not alone in the world; I shall never be alone, for my revenge is with me”?32 The question becomes muddier if, as Eliot’s narrator permits, we consider his revenge warranted—owing to Tito’s betrayal—and thus unlike his son’s villainy.

Hatred and Civility also interprets works by writers (including Eliot and Charlotte Brontë) who, despite their frequent avoidance of admirers and occasional statements about others’ disloyalty, are rarely called misanthropes.33 They appear in this book because misanthropy is a factor they represented and struggled to diminish in their work. Moreover, the following chapters combine historical arguments with philosophical claims about hatred, including the limits of fellowship and humanity’s near limitless capacity for malice—topics close to Eliot’s heart, since many of her siblings and friends rejected her for living unmarried with George Henry Lewes. As an accompaniment to my allusion to Romola and a foretaste of later inquiry, Eliot’s readers might ponder why her fictional teachers and intellectuals invariably are curmudgeonly (for example, Bartle Massey in Adam Bede, Bardo de’ Bardi in Romola, and the scabrous Edward Casaubon in Middlemarch) or confirmed misanthropes (Latimer in The Lifted Veil, and Touchwood, Proteus Merman, and the narrator in Impressions of Theophrastus Such). In this last, eccentric book, completed just before Eliot died, the long-suffering Merman is “lacerated,” “pilloried[,] and as good as mutilated” by the community of scholars he hopes to join. His fate is written as an allegory and given the richly sardonic title “How We Encourage Research.”34

Biographical details in the following chapters may help readers gauge whether a character’s opinions replicate an author’s ideas, but fiction overall should not be confused with psychobiographical and social concerns. I stress this, because the esteem in which critics hold Eliot and Brontë risks eclipsing the way antipathy in their novels corrupts fellow feeling. Eliot is a good litmus test for this problem. Invoking her countless statements on fellow feeling, some critics recoil at the thought that enmity imbues her later fiction. Justly observing that much has been written on vindictiveness in Romola, Felix Holt, Middlemarch, and Daniel Deronda, others contend that arguments about hatred’s persistence in her work are now so obvious as to be almost banal. Both reactions are a problem for those working on Eliot and hatred. While offering proof of this emotion risks eclipsing Eliot’s well-known thoughts on fellow feeling, resulting in merely a fatuous preoccupation with evidence, a stronger account of what hatred does in her work won’t satisfy those who believe Eliot resolved her fictions’ moral ambiguities in the first place.

The problem deepens when one implicates several truisms in Eliot studies: Her critical and narrative perspectives often clash; her later works differ considerably from her earlier fiction; perspectives on fellow feeling shift imperceptibly within novels; and what Eliot achieves in her fiction frequently produces effects she denounces in her letters and essays. With other writers—say, Edward Lytton Bulwer—these tensions are easier to explain and somehow matter less. With Eliot, even sophisticated critics view her fiction and philosophy as mutually reinforcing. As with perhaps no other Victorian writer, scholars search her essays and letters for the exact cause of her literary arguments. Given these factors, can one plausibly examine her works’ multiple concerns without appearing mildly contradictory?

I suspect not. If after detailing Eliot’s preoccupation with ill will one provides her thoughts on fellow feeling, he or she risks accusing her improbably of idealism or naïveté. Yet given Eliot’s remarkable talent as a writer, even the smallest allusion to ethical failure can seem patronizing, translating easily into presumptions about artistic deficiency. As this dilemma raises wider questions about interpretive method and the status of literature in this book, let me add that even the most stolidly realist narrative or didactic tract may convey fantasies contradicting its stated design. To that end, it is paradoxical but not naïve to assert that fiction alternately buttresses and challenges hypotheses about society. Moreover, for good or ill, young Victorians arguably derived more instruction from reading novels than by reading philosophy, sermons, tracts, biographies, and even conduct books. Admittedly, these contentions about fiction’s effects may vex historians, just as too many speculative claims could lead us to echo Thomas Gradgrind, Dickens’s ardent utilitarian in Hard Times: “Now, what I want is, Facts. … Facts alone are wanted in life.”35 Certainly, Hatred and Civility reproduces a fair number of them. But a purely empirical approach to hatred—like a literalist approach to fiction—can’t account for hatred’s and fiction’s counterintuitive effects. As Browning’s speaker declares suggestively in Ferishtah’s Fancies: “Soul—too weak, forsooth / To cope with fact—wants fiction everywhere!”; the latter alone blends “things visible and invisible.”36 “Whoever enlists fiction to assist in the hunt for knowledge,” adds Peter Gay in his recent study, Savage Reprisals, “must always be alert to authorial partisanship, limiting cultural perspectives, fragmentary details offered as authoritative, to say nothing of neurotic obsessions.”37 To assess the ensuing literary effects, one must surely combine Gay’s approach to intellectual and cultural history with a form of close reading that poets such as Browning practiced.

While parsing these concerns in my Eliot chapter, I question more broadly in this book whether aesthetic harmony requires an ethical resolution of narrative conflict, and whether hatred in novels is gratifying because it voices a set of tensions that Victorian society symbolized more reluctantly. This is where I depart from Gay’s fascinating claim that novelists such as Dickens, Flaubert, and Thomas Mann composed several works in revenge against personal slights.38 Focusing less on the relation between biography and creativity, I explore the philosophical repercussions of extreme hatred in Victorian culture, before weighing their effect on, say, Eliot’s fictional communities and her statements about compassion. Eliot arguably could picture the latter only in abstract, impersonal forms; solicitude fails when her fiction makes altruism bridge deeply embittered conflicts among neighbors. More broadly, that her largely intellectual interest in hatred could tarnish her reputation sadly confirms what misanthropy has come to mean for us. To those insisting on a clear correspondence between her fiction and her life, I can only add that despite cultivating a persona exuding warmth, Eliot chafed at being put on a pedestal. Like Jane Austen, she also wrote in her letters comments on other people that might surprise a few of her readers.

As this book draws on some material unknown to Victorianists and general readers (the pages of many sole surviving editions at the British Library being previously uncut), I supplement analysis of rare works with salient quotations. Despite the mediocrity of these works, they signal what was published on hatred in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Britain.

Readers interested in the history of misanthropy should consult Not in Timon’s Manner, Thomas Preston’s lively account of “feeling, misanthropy, and satire in eighteenth-century England.”39 Among the growing number of studies on Victorian misanthropy, four stand out as particular influences: Gay’s The Cultivation of Hatred, volume 3 of The Bourgeois Experience, from Victoria to Freud, and Savage Reprisals; Daniel Karlin’s Browning’s Hatreds; and Victor Brombert’s In Praise of Antiheroes.40 With these key texts, Adam Gillon’s The Eternal Solitary: A Study of Joseph Conrad proved indispensable, as did John Portmann’s philosophically rich account of schadenfreude in When Bad Things Happen to Other People.41 I also found compelling Barbara Ehrenreich’s observations in The Snarling Citizen and Nobel Prize winner Wisława Szymborska’s poem “Hatred,” which asserts that this emotion “knows how to make beauty,” even though it creates a face “twisted in a grimace / of erotic ecstasy.”42 Among the many philosophical works influencing this project were Giorgio Agamben’s oblique but fascinating Language and Death: The Place of Negativity; Alain Badiou’s provocative study Ethics: An Essay on the Understanding of Evil; Joan Copjec’s collection Radical Evil; Renata Salecl’s (Per)Versions of Love and Hate; and Slavoj Žižek’s Tarrying with the Negative: Kant, Hegel, and the Critique of Ideology.43 Finally, for a wryly intelligent overview of misanthropy, focusing especially on contemporary people-hating in North America, one should read Florence King’s With Charity Toward None: A Fond Look at Misanthropy.44