Vincent van Gogh at the age of nineteen, January 1873

Vincent van Gogh’s letters are without any doubt the most impressive artist’s correspondence we know. Providing an inexhaustible source of information about the artist’s dramatic life and exceptional work, these documents have been studied by generations of art historians and biographers. From their first publication, Van Gogh’s letters have also been valued for the intrinsic qualities of his writing, his evocative style and vivid, unadorned language. They convey the artist’s personal ideas and emotions in such a compelling way that they attain the universality of all great literature.

Van Gogh was passionate to the point of fanaticism and expressed himself without reservation. He showed his vulnerability by asserting ideals, by getting into arguments, and by sharing with the reader his outrage, his melancholy, and later his mental illness. The letters tell the story of his eventful life, detailing his close ties with his brother Theo, and the evolution of his artistic skills. It is the insight they give us into the development of a ground-breaking artist – a man who did not hesitate to show his most human side – that make these letters so fascinating.

With hindsight it can be said that he developed as an artist with amazing speed: it took him only ten years to draw and paint the extensive oeuvre that would make him world-famous. Recognition was a long time in coming, however. Only after his self-inflicted death in 1890 did his work finally begin to receive the attention it deserved and his reputation as a pioneering artist become firmly established – a development in which his letters played a vital role.

The letters in this publication have been carefully selected to give both the first-time reader and the connoisseur an immersive and enlightening account of Van Gogh’s life and ideas during his years as an artist, from 1880 to 1890, living in Belgium, the Netherlands, and France. The letters have not been abridged but have been set out in their entirety, to respect the composition and tone of Van Gogh’s letters.

Vincent van Gogh at the age of nineteen, January 1873

Vincent van Gogh: a Complex Character

Van Gogh cut a striking figure. Theo’s wife Jo van Gogh-Bonger, who became acquainted with Vincent in 1890, described him in her introduction to the 1914 letters edition as ‘a robust, broad-shouldered man with a healthy complexion, a cheerful expression and something very determined in his appearance’. Small in stature, Vincent had green eyes, a red beard and freckles; his hair was ginger-coloured like that of his brother Theo, his junior by four years. He had a facial tic, and his hands seemed to be in constant motion. He was rather unsociable, which made him difficult to live with. People were often afraid of him, because of his wild and unkempt appearance and his intense manner of speaking. The way he looked and acted alienated people, which did not make life easy for him.

Van Gogh was almost always convinced that he was right, and this made him quite tiresome. He was a passionate, driven man, whose tendency to act like an egocentric bully made many people dislike him. Van Gogh refused to let this upset him: ‘[B]elieve me that I sometimes laugh heartily at how people suspect me (who am really just a friend of nature, of study, of work – and of people chiefly) of various acts of malice and absurdities which I never dream of’ (252). He did not avoid confrontations, nor did he spare himself. Theo described him in a letter of March 1887 to their sister Willemien as ‘his own enemy’.

Van Gogh was strongly inclined towards introspection: he never hesitated to explore and record his mood swings, or to redefine his moral position. He did this mainly because he had few people to talk to. Examining his own state of mind, he saw a ‘highly strung’ individual. At the age of twenty-nine, he sketched a merciless picture of himself:

Don’t imagine that I think myself perfect – or that I believe it isn’t my fault that many people find me a disagreeable character. I’m often terribly and cantankerously melancholic, irritable – yearning for sympathy as if with a kind of hunger and thirst – I become indifferent, sharp, and sometimes even pour oil on the flames if I don’t get sympathy. I don’t enjoy company, and dealing with people, talking to them, is often painful and difficult for me. But do you know where a great deal if not all of this comes from? Simply from nervousness – I who am terribly sensitive, both physically and morally, only really acquired it in the years when I was deeply miserable. (244)

These last words refer to the years immediately before he embarked on his artistic career.

However impulsive Van Gogh was, he generally set to work only after much deliberation: ‘For the great doesn’t happen through impulse alone, and is a succession of little things that are brought together’ (274). Time and again, it was willpower and hard work that enabled Van Gogh to raise his low spirits.

A loving and protective family

As is the case with all of us, Van Gogh’s character was to a certain degree imprinted by his upbringing and family circle. Vincent, born in 1853, was the son of a village parson in rural Brabant. His parents, Theodorus van Gogh (1822–85) and Anna van Gogh-Carbentus (1819–1907), raised their children with Christian values that formed the basis of a virtuous and hardworking life. As was usual among middle-class families in the nineteenth century, they all did their utmost to prevent any member of the family from drifting away from the fold, as it were. Together they strove to lead a respectable life, in strict observance of the proprieties and in the firm conviction that those who become well-regarded members of society will encounter much good in their lives. The modest livings occupied by the Reverend Theodorus van Gogh comprised the villages of Zundert, Helvoirt, Etten and Nuenen, all situated in the province of Noord-Brabant in the south of the Netherlands. As a preacher who attached great importance to morally acceptable behaviour, he could count on a good deal of sympathy from his parishioners.

Vincent, the oldest of six children, was not the firstborn: exactly one year before his birth, his mother had been delivered of a stillborn child, likewise named Vincent. Vincent was followed by Anna (1855–1930), Theo (1857–91), Elisabeth (‘Lies’, 1859–1936), Willemien (‘Wil’, 1862–1941) and Cornelis (‘Cor’, 1867–1900). Their mother, a kind-hearted woman, shared the care of the family with her husband and a nursemaid.

The love between the parents and their children and the respect they showed one another is evident from the family correspondence, of which hundreds of letters have survived. Fond memories of his early years were deeply rooted in Vincent, and they surfaced during the attacks of mental illness (considered in those days to be a form of epilepsy but now generally thought to have been psychoses) that disrupted the last year and a half of his life. At the end of 1888, after his first serious breakdown, he reported that during his illness he had seen ‘each room in the house at Zundert, each path, each plant in the garden, the views round about’ – every detail, in fact, of the surroundings of his parental home (741).

The Van Goghs wanted to give all their children an education that would allow them to develop their talents to the full, but this was no easy task, financially speaking. Their main worry turned out to be finding a suitable position for Vincent. In the nineteenth century, association with the upper class was often a means of advancement for members of the middle class, and parents who were determined to help their children succeed stimulated and even engineered their climb up the social ladder. This is apparent from the advice the Van Goghs gave their children about moving in society, which books to read, and the courtesy calls they should make. By present-day standards the children were extremely obedient, but this can be explained by the prevailing standards of conduct, which were dictated by middle-class Christian morals. When things went wrong, however, and a person was unwilling or unable to comply with these high standards, it could easily lead, as it did in Van Gogh’s case, to a gnawing sense of guilt and a permanent feeling of failure in one’s duties towards those who had one’s best interests at heart.

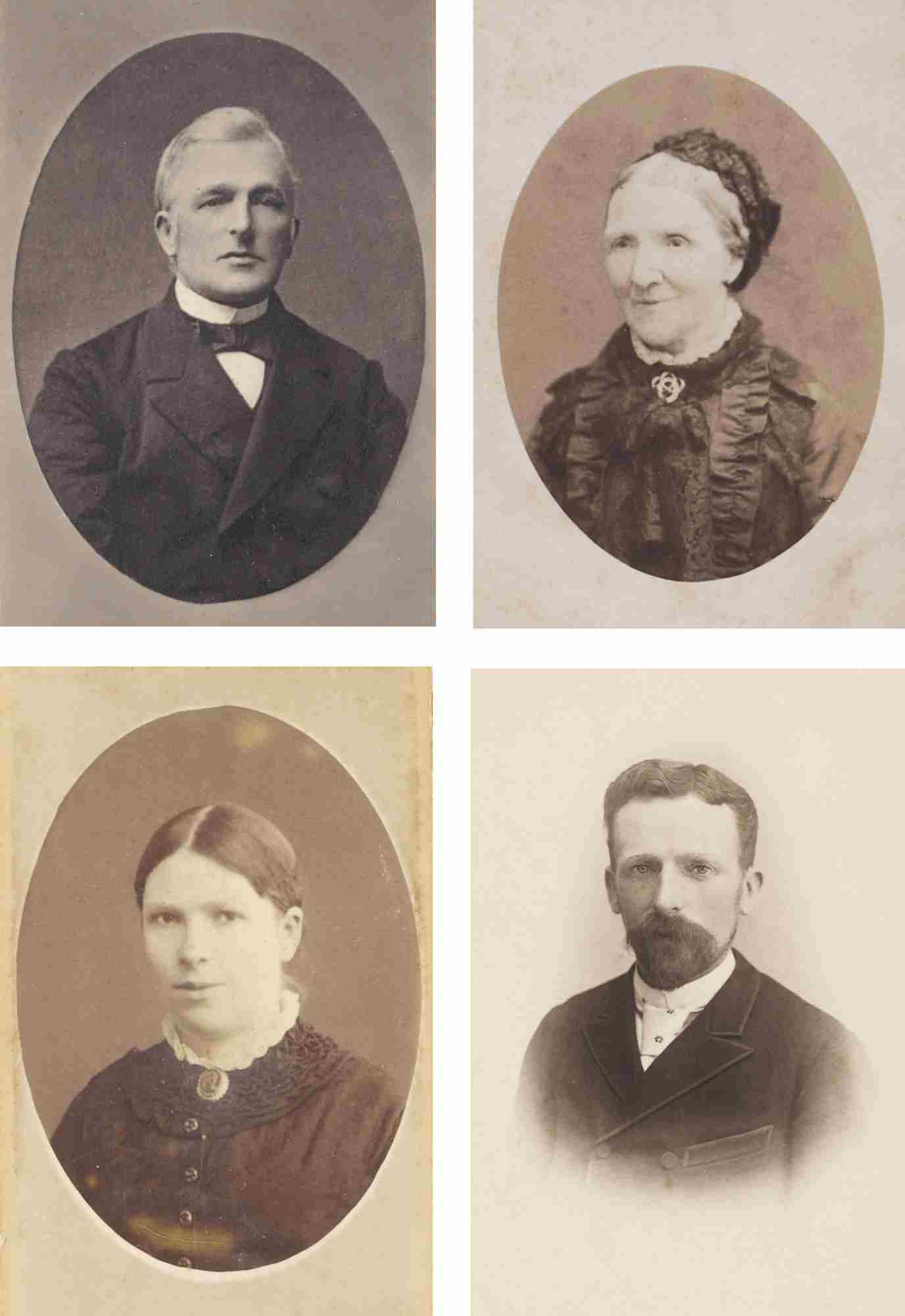

CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT: The Revd Theodorus van Gogh (Vincent’s father), date of photograph unknown; Anna van Gogh-Carbentus (Vincent’s mother), 1880–88; Theo van Gogh (Vincent’s brother), 1889; Willemien van Gogh (Vincent’s sister), c. 1887

The duty of solidarity was characteristic of the Van Gogh family. Leading a pious life and lending one another support were in the general interest, and that was also true of other group activities that kept the family together, such as attending church, singing hymns and reading and reciting morally acceptable poetry and novels, all of which strengthened both heart and mind.

For a long time harmony prevailed in the Van Gogh family, but in 1876 there was a flare-up of the tension between Vincent and his father, and the discord continued until the latter’s death in 1885. Their lifestyles became increasingly incompatible, and Vincent’s social maladjustment was a constant source of irritation to his father. Vincent, in turn, was annoyed at his father’s interference and narrow-mindedness; holding his ground, he showed complete disregard for the conventions his parents considered so important. His workman’s clothes, his unpredictable behaviour and his association with people from the lower classes were thorns in his parents’ sides. For Vincent, things became clear to him late in 1883: ‘In character I’m quite different from the various members of the family, and I’m actually not a “Van Gogh” ’ (411).

The bond with Theo

Although he came to distance himself from his family, Vincent had a special bond with Theo. Theo was the apple of his parents’ eyes and the diplomat and linchpin in the family. Vincent’s late decision to become an artist, at the age of twenty-seven, was largely due to Theo’s encouragement. The fact that it was Theo who persuaded him to pursue an artistic career greatly influenced their relationship in the following years. Theo considered it his duty to lend Vincent both moral and financial support. Throughout the ten years of Vincent’s life as an artist, Theo remained an obliging benefactor, whose support was invaluable in furthering his brother’s artistic endeavours. At first Vincent viewed Theo’s financial support as a loan that he would one day be able to repay – an advance on what he would be earning as soon as buyers could be found for his work. When this failed to happen, however, the brothers agreed that Theo could deal freely with Vincent’s drawings and paintings. Theo thought that brotherliness was much more important than cashing in on his investment, although as time went on he also became convinced of the special quality and value of Vincent’s work.

It may appear as though the relationship between the brothers was one-sided, with the calm, generous Theo always ready to help his stubborn impulsive brother and receiving little in return. But Theo, for his part, depended heavily on Vincent, describing him to his wife Jo as ‘adviser and brother to both of us, in every sense of the word’. Vincent and Theo’s mutual dependence continued to grow over the years, but not without many conflicts. At times Vincent was mean and nasty to Theo, and he always tried to get his way. This put a lot of strain on their relationship, so much so that at one point Theo was convinced that it would be better for them to part ways. Yet their fraternal friendship proved able to withstand such fierce clashes. Theo supported Vincent through life’s difficulties and acted as a buffer between him and the ‘hostile world’ (406). The kind-hearted Theo, who felt responsible for Vincent his whole life and always remained loyal to him, protected his brother and saved him from many pitfalls.

Vincent repressed his feelings of guilt towards Theo, his dearest friend and confidant, and the only one who could cope with his difficult character. Vincent was well aware that his brother was investing a great deal in him, and the knowledge that he would never be able to repay Theo occasionally made him despair.

Searching for his Destiny

Working in the art trade, 1869–1876

Vincent attended the village school in Zundert and received lessons at home from a governess. He then spent several years at a boarding school for boys in Zevenbergen and went from there to a secondary school in Tilburg, the Hogere Burgerschool Willem II. After living at home for another year, at the end of July 1869 he finally found – at the age of sixteen – a position as the youngest employee of the international art dealer Goupil & Cie in The Hague.

Goupil & Cie Gallery, The Hague, c. 1900

It was one of his father’s brothers, also called Vincent (Uncle Cent), who introduced Vincent to the art world. For years Uncle Cent had been a partner in the firm of Goupil & Cie, and he now put in a good word for his nephew. Vincent was thus given a chance to become intimately acquainted with the art trade. The firm flourished, its success due in part to the publication and sale of reproductions of numerous artworks. Van Gogh’s work for an art dealer – spending his days surrounded by paintings, prints and photographs – and his visits to museums laid the basis for his impressive knowledge of art. His boss, Hermanus Tersteeg, showed him the ropes and taught him a great deal about art and literature.

Goupil & Cie had a number of branches, and in May 1873 Van Gogh began working for the company’s London branch. The correspondence from these years reveals that he was seeking a place outside the protected world in which he had grown up. In his spare time he walked as much as he could and worked in the garden. Sometimes he was very homesick. On holidays such as Christmas and Easter, the family tended to gather at the Helvoirt parsonage, where the Van Goghs were now living. By this time Theo was also working for Goupil, starting at the Brussels branch and moving to the Hague branch at the end of 1873. In London Vincent changed address often: in August he moved to Brixton, and a year later to Kennington. His appreciation of the city grew, as did his interest in art and literature. His letters contain many quotations from books that had moved him; Theo, in turn, sent his brother poetry. Their tastes and preferences were perfectly in keeping with the fashions of the day: romantic poetry (Heinrich Heine, Alphonse de Lamartine) and Victorian novels (George Eliot, Charles Dickens). Literature was a comfort to the boys and helped them expand their horizons.

Religious obsession

After a temporary transfer to the main branch in Paris, Vincent returned in early 1875 to London, where he began working for the gallery of Holloway & Sons, which had been taken over by Goupil & Cie. In mid-May he was back at the Paris branch. He gave detailed accounts of his visits to the Salon, the Louvre and the Musée du Luxembourg, and he described the prints he had hung in his small room in Montmartre, where he became friendly with his housemate, Harry Gladwell. Night after night he read the Bible out loud to this Englishman: ‘We intend to read it all the way through’ (55). Van Gogh became more and more obsessed with Bible study and went to church frequently. The letters written at this time are full of references to Holy Scripture, rhyming psalms, Evangelical hymns and devotional literature. This religious obsession, which lasted for several years, caused him to neglect his work and was one of the reasons for his eventual dismissal from Goupil’s.

In October 1875 the Van Gogh family moved to the village of Etten, where the Reverend Van Gogh had been appointed. Vincent spent Christmas and New Year’s with them here. When he returned to Paris, he heard that Goupil had decided to terminate his contract as of 1 April, partly because he had stayed away too long during the busy time at the end of the year, though another cause of consternation was his attitude to his job. His father was deeply disappointed, and wrote about it in what were, by his standards, very bitter letters to Theo, since the consequences for the family were especially painful: ‘How much he has spurned! What bitter sorrow for Uncle Cent. What a bitter experience. We are glad that we live in relative isolation here and would really like to shut ourselves in. It is an unspeakable sorrow.’ Vincent seemed less upset by this loss of face, although he definitely felt guilty. Working in the art trade for six years had indeed taught him a lot, but it had not made him happy or opened up any prospects for a career. His future was now completely up in the air.

The Search for a Calling, 1876–1880

Van Gogh spent the next four years in England, the Netherlands and Belgium, trying to find his direction in life. After his dismissal from Goupil & Cie, he travelled in April 1876 to Ramsgate, near London, to work as an assistant teacher at a boarding school for boys run by William Stokes. After a trial period of one month, he was allowed to stay, but without a salary. Shortly afterwards the school – along with Van Gogh – moved to Isleworth. There he enjoyed long walks and took pleasure in the boys’ company, but he soon realized that he would prefer pastoral work, something ‘between minister and missionary, in the suburbs of London among working folk’ (84). Not only that, but he was also urgently in need of a steady income.

In July he went to work at another boarding school, also in Isleworth, run by the Methodist minister Thomas Slade-Jones. Vincent’s letters to Theo became longer and longer, owing to serious digressions and an abundance of biblical quotations. His increasing interest in religion was accompanied by more moralistic reading, his favourites being George Eliot’s Scenes of Clerical Life and Felix Holt, John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress and Thomas a Kempis’s De imitatione Christi. To his immense satisfaction he was given his first opportunity to deliver a sermon at the Wesleyan Methodist Church in Richmond in October. The sermon, which he copied out for Theo and enclosed in a letter, compared life to a pilgrimage (96). Shortly after this he became a lay preacher at the Congregational Church in Turnham Green, and also taught at their Sunday school, but as an unpaid volunteer. While he was home for Christmas – as always, a time for reflection, when they all came together in a veritable conclave – the family discussed Vincent’s limited prospects in England, and it was decided that he would stay in the Netherlands.

Uncle Vincent arranged a job for him as a clerk-cum-factotum for Blussé & Van Braam, a bookseller in Dordrecht. During this period Van Gogh’s religious fanaticism intensified. His letters were now full of devotional texts and musings about his desire to become a preacher; numerous biblical prints decorated the walls of his room; and he attended one church service after another, exploring a wide variety of denominations. A line from Paul’s Second Epistle to the Corinthians – ‘sorrowful, yet alway rejoicing’ – became a motto that he wore like ‘a good cloak in the storm of life’ (109).

Yet another failure

Van Gogh’s struggle was bound up with his own uncertainty about his place in the world. He dreamed of a vocation in the church, spreading the Word as a preacher, like his father. He viewed striving to achieve that goal as a means of freeing himself from the ‘torrent of reproaches’ that he had ‘heard and felt’ (106). Influenced by his Calvinist upbringing, he spoke more than once of the conscience as man’s infallible, God-given moral compass. But however conscientiously he tried to live his life, somehow he could not find the right path. His work at the bookshop was merely a temporary solution; the family continued to search for a suitable situation for him. Uncle Cent, who had been so supportive up to now, stopped trying to help when it became apparent that his nephew was serious about becoming a preacher.

Vincent – who had no high school diploma – approached other uncles in Amsterdam for suggestions and help in preparing himself to study theology. His family was by no means convinced that this was his true calling, and they worried about his unstable mental state. Even so, Vincent moved to Amsterdam in good spirits in May 1877 and went to live with one of his father’s brothers, Uncle Jan van Gogh, director of the naval dockyard. A maternal uncle, the minister Johannes Stricker, took it upon himself to supervise Vincent’s studies.

Preparing for the university entrance exam proved extremely difficult for Vincent. As he so often did, he compensated for his lack of ability by going for long walks and writing about them in letters full of lengthy, evocative passages. No matter how hard he tried to persevere in his studies, he became more and more downcast and disheartened. He wrote to Theo that his head was numb and burning and his thoughts confused. Once again he realized that he had failed in the task he had set himself. Years later he would look back on his year in Amsterdam as ‘the worst time’ he had ever been through (154). Dejected and defeated, he returned to his parents’ house in Etten, hoping that he might become a Sunday-school teacher.

Evangelist in the Borinage

In July 1878 Vincent went to Brussels in the company of his father and the Reverend Slade-Jones to discuss his admission to a Flemish training college for evangelists. He was given a three-month trial period and sent to work in Laken, where he lived with a board member’s family. He was not accepted for the training course, however, and left in early December 1878 for the Borinage, the mining region of Belgium, to look for evangelical work. In mid-January 1879 he was given a six-month appointment as a lay preacher in Wasmes, a village near Mons. His tasks included giving Bible readings, teaching children and visiting the sick. Van Gogh was confronted with real poverty and squalor, but he devoted himself wholeheartedly to caring for the sick and injured. He identified so much with the poor that he gave away all his possessions and lived in a small hut, where he slept on the ground.

This exaggerated display of humility was one reason for the evangelization committee’s dissatisfaction with him; they also judged him to be lacking in both the gift of speech and the organizational skills necessary to hold gatherings at which the congregation could be taught the Gospel. His appointment was terminated, and in August he left for the nearby village of Cuesmes, where he went to live with an evangelist. Impressed by this ‘singular, remarkable and picturesque region of the country’ (150), he concentrated more and more on drawing. For years he had drawn for his own pleasure, and occasionally included sketches in his letters. Now, however, drawing – together with writing – became an increasingly important way of capturing his impressions in images: ‘Often sit up drawing until late at night to have some keepsakes and to strengthen thoughts that automatically spring to mind upon seeing the things’ (153).

Theo went to visit him, and they discussed Vincent’s future. Feelings must have run high during this talk, because immediately after Theo’s departure, Vincent defended himself in a letter that reveals the fears and differences of opinion that were seriously undermining his relations with Theo and the rest of the family (154). The rift between the brothers ultimately led them to stop corresponding for nearly a year. Vincent broke the silence with a cri de coeur in which he expressed himself with exceptional force (155). He felt like a caged bird, a good-for-nothing, but he wanted to make himself useful and find his vocation in life, and he accepted the help Theo was offering him.

To Theo van Gogh (letter 155)

My dear Theo,

It’s with some reluctance that I write to you, not having done so for so long, and that for many a reason. Up to a certain point you’ve become a stranger to me, and I too am one to you, perhaps more than you think; perhaps it would be better for us not to go on this way.

It’s possible that I wouldn’t even have written to you now if it weren’t that I’m under the obligation, the necessity, of writing to you. If, I say, you yourself hadn’t imposed that necessity. I learned at Etten that you had sent fifty francs for me; well, I accepted them. Certainly reluctantly, certainly with a rather melancholy feeling, but I’m in some sort of impasse or mess; what else can one do?

And so it’s to thank you for it that I’m writing to you.

As you may perhaps know, I’m back in the Borinage; my father spoke to me of staying in the vicinity of Etten instead; I said no, and I believe I acted thus for the best. Without wishing to, I’ve more or less become some sort of impossible and suspect character in the family, in any event, somebody who isn’t trusted, so how, then, could I be useful to anybody in any way?

That’s why, first of all, so I’m inclined to believe, it is beneficial and the best and most reasonable position to take, for me to go away and to remain at a proper distance, as if I didn’t exist. What moulting is to birds, the time when they change their feathers, that’s adversity or misfortune, hard times, for us human beings. One may remain in this period of moulting, one may also come out of it renewed, but it’s not to be done in public, however; it’s scarcely entertaining, it’s not cheerful, so it’s a matter of making oneself scarce. Well, so be it. Now, although it may be a thing of rather demoralizing difficulty to regain the trust of an entire family perhaps not entirely devoid of prejudices and other similarly honourable and fashionable qualities, nevertheless, I’m not utterly without hope that little by little, slowly and surely, a good understanding may be re-established with this person and that.

In the first place, then, I’d like to see this good understanding, to say no more, re-established between my father and me, and I would also be very keen that it be re-established between the two of us. Good understanding is infinitely better than misunderstanding.

I must now bore you with certain abstract things; however, I’d like you to listen to them patiently.

I, for one, am a man of passions, capable of and liable to do rather foolish things for which I sometimes feel rather sorry. I do often find myself speaking or acting somewhat too quickly when it would be better to wait more patiently. I think that other people may also sometimes do similar foolish things. Now that being so, what’s to be done, must one consider oneself a dangerous man, incapable of anything at all? I don’t think so. But it’s a matter of trying by every means to turn even these passions to good account. For example, to name one passion among others, I have a more or less irresistible passion for books, and I have a need continually to educate myself, to study, if you like, precisely as I need to eat my bread. You’ll be able to understand that yourself. When I was in different surroundings, in surroundings of paintings and works of art, you well know that I then took a violent passion for those surroundings that went as far as enthusiasm. And I don’t repent it, and now, far from the country again, I often feel homesick for the country of paintings.

You may perhaps clearly remember that I knew very well (and it may well be that I still know) what Rembrandt was or what Millet was, or Jules Dupré or Delacroix or Millais or M. Maris.

Good — now I no longer have those surroundings — however, that something that’s called soul, they claim that it never dies and that it lives for ever and seeks for ever and for ever and for evermore.

So instead of succumbing to homesickness, I said to myself, one’s country or native land is everywhere. So instead of giving way to despair, I took the way of active melancholy as long as I had strength for activity, or in other words, I preferred the melancholy that hopes and aspires and searches to the one that despairs, mournful and stagnant. So I studied the books I had to hand rather seriously, such as the Bible and Michelet’s La révolution Française, and then last winter, Shakespeare and a little V. Hugo and Dickens and Beecher Stowe, and then recently Aeschylus, and then several other less classic authors, several good minor masters. You well know that one who is ranked among the minor (?) masters is called Fabritius or Bida.

Now the man who is absorbed in all that is sometimes shocking, to others, and without wishing to, offends to a greater or lesser degree against certain forms and customs and social conventions. It’s a pity, though, when people take that in bad part. For example, you well know that I’ve frequently neglected my appearance, I admit it, and I admit that it’s shocking. But look, money troubles and poverty have something to do with it, and then a profound discouragement also has something to do with it, and then it’s sometimes a good means of ensuring for oneself the solitude needed to be able to go somewhat more deeply into this or that field of study with which one is preoccupied. One very necessary field of study is medicine; there’s hardly a man who doesn’t try to know a little bit about it, who doesn’t try to understand at least what it’s about, and here I still don’t know anything at all about it. But all of that absorbs you, but all of that preoccupies you, but all of that makes you dream, ponder, think.

And now for as much as 5 years, perhaps, I don’t know exactly, I’ve been more or less without a position, wandering hither and thither. Now you say, from such and such a time you’ve been going downhill, you’ve faded away, you’ve done nothing. Is that entirely true?

It’s true that sometimes I’ve earned my crust of bread, sometimes some friend has given me it as a favour; I’ve lived as best I could, better or worse, as things went; it’s true that I’ve lost several people’s trust, it’s true that my financial affairs are in a sorry state, it’s true that the future’s not a little dark, it’s true that I could have done better, it’s true that just in terms of earning my living I’ve lost time, it’s true that my studies themselves are in a rather sorry and disheartening state, and that I lack more, infinitely more than I have. But is that called going downhill, and is that called doing nothing?

Perhaps you’ll say, but why didn’t you continue as people would have wished you to continue, along the university road?

To that I’d say only this, it costs too much and then, that future was no better than the present one, on the road that I’m on. But on the road that I’m on I must continue; if I do nothing, if I don’t study, if I don’t keep on trying, then I’m lost, then woe betide me. That’s how I see this, to keep on, keep on, that’s what’s needed.

But what’s your ultimate goal, you’ll say. That goal will become clearer, will take shape slowly and surely, as the croquis becomes a sketch and the sketch a painting, as one works more seriously, as one digs deeper into the originally vague idea, the first fugitive, passing thought, unless it becomes firm.

You must know that it’s the same with evangelists as with artists. There’s an old, often detestable, tyrannical academic school, the abomination of desolation, in fact — men having, so to speak, a suit of armour, a steel breastplate of prejudices and conventions. Those men, when they’re in charge of things, have positions at their disposal, and by a system of circumlocution seek to support their protégés, and to exclude the natural man from among them.

Their God is like the God of Shakespeare’s drunkard, Falstaff, ‘the inside of a church’; in truth, certain evangelical (???) gentlemen find themselves, by a strange conjunction (perhaps they themselves, if they were capable of human feeling, would be somewhat surprised) find themselves holding the very same point of view as the drunkard in spiritual matters. But there’s little fear that their blindness will ever turn into clear-sightedness on the subject.

This state of affairs has its bad side for someone who doesn’t agree with all that, and who protests against it with all his heart and with all his soul and with all the indignation of which he is capable.

Myself, I respect academicians who are not like those academicians, but the respectable ones are more thinly scattered than one would believe at first glance. Now one of the reasons why I’m now without a position, why I’ve been without a position for years, it’s quite simply because I have different ideas from these gentlemen who give positions to individuals who think like them.

It’s not a simple matter of appearance, as people have hypocritically held it against me, it’s something more serious than that, I assure you.

Why am I telling you all this? — not to grumble, not to apologize for things in which I may be more or less wrong, but quite simply to tell you this: on your last visit, last summer, when we walked together near the disused mine they call La Sorcière, you reminded me that there was a time when we also walked together near the old canal and mill of Rijswijk, and then, you said, we were in agreement on many things, but, you added — you’ve really changed since then, you’re not the same any more. Well, that’s not quite how it is; what has changed is that my life was less difficult then and my future less dark, but as far as my inner self, as far as my way of seeing and thinking are concerned, they haven’t changed. But if in fact there were a change, it’s that now I think and I believe and I love more seriously what then, too, I already thought, I believed and I loved.

So it would be a misunderstanding if you were to persist in believing that, for example, I would be less warm now towards Rembrandt or Millet or Delacroix, or whomever or whatever, because it’s the opposite. But you see, there are several things that are to be believed and to be loved; there’s something of Rembrandt in Shakespeare and something of Correggio or Sarto in Michelet, and something of Delacroix in V. Hugo, and in Beecher Stowe there’s something of Ary Scheffer. And in Bunyan there’s something of M. Maris or of Millet, a reality more real than reality, so to speak, but you have to know how to read him; then there are extraordinary things in him, and he knows how to say inexpressible things; and then there’s something of Rembrandt in the Gospels or of the Gospels in Rembrandt, as you wish, it comes to more or less the same, provided that one understands it rightly, without trying to twist it in the wrong direction, and if one bears in mind the equivalents of the comparisons, which make no claim to diminish the merits of the original figures.

If now you can forgive a man for going more deeply into paintings, admit also that the love of books is as holy as that of Rembrandt, and I even think that the two complement each other.

I really love the portrait of a man by Fabritius, which one day, also while taking a walk together, we looked at for a long time in the Haarlem museum. Good, but I love Dickens’s ‘Richard Cartone’ in his Paris et Londres en 1793 just as much, and I could show you other strangely vivid figures in yet other books, with more or less striking resemblance. And I think that Kent, a man in Shakespeare’s King Lear, is just as noble and distinguished a character as any figure of Th. de Keyser, although Kent and King Lear are supposed to have lived a long time earlier. To put it no higher, my God, how beautiful that is. Shakespeare — who is as mysterious as he? — his language and his way of doing things are surely the equal of any brush trembling with fever and emotion. But one has to learn to read, as one has to learn to see and learn to live.

So you mustn’t think that I’m rejecting this or that; in my unbelief I’m a believer, in a way, and though having changed I am the same, and my torment is none other than this, what could I be good for, couldn’t I serve and be useful in some way, how could I come to know more thoroughly, and go more deeply into this subject or that? Do you see, it continually torments me, and then you feel a prisoner in penury, excluded from participating in this work or that, and such and such necessary things are beyond your reach. Because of that, you’re not without melancholy, and you feel emptiness where there could be friendship and high and serious affections, and you feel a terrible discouragement gnawing at your psychic energy itself, and fate seems able to put a barrier against the instincts for affection, or a tide of revulsion that overcomes you. And then you say, How long, O Lord! Well, then, what can I say; does what goes on inside show on the outside? Someone has a great fire in his soul and nobody ever comes to warm themselves at it, and passers-by see nothing but a little smoke at the top of the chimney and then go on their way. So now what are we to do, keep this fire alive inside, have salt in ourselves, wait patiently, but with how much impatience, await the hour, I say, when whoever wants to, will come and sit down there, will stay there, for all I know? May whoever believes in God await the hour, which will come sooner or later.

Now for the moment all my affairs are going badly, so it would seem, and that has been so for a not so inconsiderable period of time, and it may stay that way for a future of longer or shorter duration, but it may be that after everything has seemed to go wrong, it may then all go better. I’m not counting on it, perhaps it won’t happen, but supposing there were to come some change for the better, I would count that as so much gained; I’d be pleased about it, I’d say, well then, there you are, there was something, after all.

But you’ll say, though, you’re an execrable creature since you have impossible ideas on religion and childish scruples of conscience. If I have any that are impossible or childish, may I be freed from them; I’d like nothing better. But here’s where I am on this subject, more or less. You’ll find in Souvestre’s Le philosophe sous les toits how a man of the people, a simple workman, very wretched, if you will, imagined his mother country, ‘Perhaps you have never thought about what your mother country is, he continued, putting a hand on my shoulder; it’s everything that surrounds you, everything that raised and nourished you, everything you have loved. This countryside that you see, these houses, these trees, these young girls, laughing as they pass by over there, that’s your mother country! The laws that protect you, the bread that is the reward of your labour, the words that you exchange, the joy and sadness that come to you from the men and the things among which you live, that’s your mother country! The little room where you once used to see your mother, the memories she left you, the earth in which she rests, that’s your mother country! You see it, you breathe it everywhere! Just think, your rights and your duties, your attachments and your needs, your memories and your gratitude, put all that together under a single name, and that name will be your mother country.’

Now likewise, everything in men and in their works that is truly good, and beautiful with an inner moral, spiritual and sublime beauty, I think that that comes from God, and that everything that is bad and wicked in the works of men and in men, that’s not from God, and God doesn’t find it good, either. But without intending it, I’m always inclined to believe that the best way of knowing God is to love a great deal. Love that friend, that person, that thing, whatever you like, you’ll be on the right path to knowing more thoroughly, afterwards; that’s what I say to myself. But you must love with a high, serious intimate sympathy, with a will, with intelligence, and you must always seek to know more thoroughly, better, and more. That leads to God, that leads to unshakeable faith.

Someone, to give an example, will love Rembrandt, but seriously, that man will know there is a God, he’ll believe firmly in Him.

Someone will make a deep study of the history of the French Revolution — he will not be an unbeliever, he will see that in great things, too, there is a sovereign power that manifests itself.

Someone will have attended, for a time only, the free course at the great university of poverty, and will have paid attention to the things he sees with his eyes and hears with his ears, and will have thought about it; he too, will come to believe, and will perhaps learn more about it than he could say.

Try to understand the last word of what the great artists, the serious masters, say in their masterpieces; there will be God in it. Someone has written or said it in a book, someone in a painting.

And quite simply read the Bible, and the Gospels, because that will give you something to think about, and a great deal to think about and everything to think about, well then, think about this great deal, think about this everything, it raises your thinking above the ordinary level, despite yourself. Since we know how to read, let’s read, then!

Now, afterwards, we may well at times be a little absent-minded, a little dreamy; there are those who become a little too absent-minded, a little too dreamy; that happens to me, perhaps, but it’s my own fault. And after all, who knows, wasn’t there some cause; it was for this or that reason that I was absorbed, preoccupied, anxious, but you get over that. The dreamer sometimes falls into a pit, but they say that afterwards he comes up out of it again.

And the absent-minded man, at times he too has his presence of mind, as if in compensation. He’s sometimes a character who has his raison d’être for one reason or another which one doesn’t always see right away, or which one forgets through being absent-minded, mostly unintentionally. One who has been rolling along for ages as if tossed on a stormy sea arrives at his destination at last; one who has seemed good for nothing and incapable of filling any position, any role, finds one in the end, and, active and capable of action, shows himself entirely different from what he had seemed at first sight.

I’m writing you somewhat at random whatever comes into my pen; I would be very happy if you could somehow see in me something other than some sort of idler.

Because there are idlers and idlers, who form a contrast.

There’s the one who’s an idler through laziness and weakness of character, through the baseness of his nature; you may, if you think fit, take me for such a one. Then there’s the other idler, the idler truly despite himself, who is gnawed inwardly by a great desire for action, who does nothing because he finds it impossible to do anything since he’s imprisoned in something, so to speak, because he doesn’t have what he would need to be productive, because the inevitability of circumstances is reducing him to this point. Such a person doesn’t always know himself what he could do, but he feels by instinct, I’m good for something, even so! I feel I have a raison d’être! I know that I could be a quite different man! For what then could I be of use, for what could I serve! There’s something within me, so what is it! That’s an entirely different idler; you may, if you think fit, take me for such a one.

In the springtime a bird in a cage knows very well that there’s something he’d be good for; he feels very clearly that there’s something to be done but he can’t do it; what it is he can’t clearly remember, and he has vague ideas and says to himself, ‘the others are building their nests and making their little ones and raising the brood’, and he bangs his head against the bars of his cage. And then the cage stays there and the bird is mad with suffering. ‘Look, there’s an idler’, says another passing bird — that fellow’s a sort of man of leisure. And yet the prisoner lives and doesn’t die; nothing of what’s going on within shows outside, he’s in good health, he’s rather cheerful in the sunshine. But then comes the season of migration. A bout of melancholy — but, say the children who look after him, he’s got everything that he needs in his cage, after all — but he looks at the sky outside, heavy with storm clouds, and within himself feels a rebellion against fate. I’m in a cage, I’m in a cage, and so I lack for nothing, you fools! Me, I have everything I need! Ah, for pity’s sake, freedom, to be a bird like other birds!

An idle man like that resembles an idle bird like that.

And it’s often impossible for men to do anything, prisoners in I don’t know what kind of horrible, horrible, very horrible cage. There is also, I know, release, belated release. A reputation ruined rightly or wrongly, poverty, inevitability of circumstances, misfortune; that creates prisoners.

You may not always be able to say what it is that confines, that immures, that seems to bury, and yet you feel I know not what bars, I know not what gates — walls.

Is all that imaginary, a fantasy? I don’t think so; and then you ask yourself, Dear God, is this for long, is this for ever, is this for eternity?

You know, what makes the prison disappear is every deep, serious attachment. To be friends, to be brothers, to love; that opens the prison through sovereign power, through a most powerful spell. But he who doesn’t have that remains in death. But where sympathy springs up again, life springs up again.

And the prison is sometimes called Prejudice, misunderstanding, fatal ignorance of this or that, mistrust, false shame.

But to speak of something else, if I’ve come down in the world, you, on the other hand, have gone up. And while I may have lost friendships, you have won them. That’s what I’m happy about, I say it in truth, and that will always make me glad. If you were not very serious and not very profound, I might fear that it won’t last, but since I think you are very serious and very profound, I’m inclined to believe that it will last.

But if it became possible for you to see in me something other than an idler of the bad kind, I would be very pleased about that.

And if I could ever do something for you, be useful to you in some way, know that I am at your service. Since I’ve accepted what you gave me, you could equally ask me for something if I could be of service to you in some way or another; it would make me happy and I would consider it a sign of trust. We’re quite distant from one another, and in certain respects we may have different ways of seeing, but nevertheless, sometime or some day one of us might be able to be of use to the other. For today, I shake your hand, thanking you again for the kindness you’ve shown me.

Now if you’d like to write to me one of these days, my address is care of C. Decrucq, rue du Pavillon 8, Cuesmes, near Mons, and know that by writing you’ll do me good.

Yours truly,

Vincent