CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT: Anton Mauve, date of photograph unknown; Kee Vos-Stricker and her son Jan, c. 1881; Anthon van Rappard, c. 1880

During his time in the Borinage, Vincent had become estranged not only from Theo, but also from his parents. As early as 1875 they had discussed Vincent’s ‘otherness’ and worried about his religious fanaticism. When he was rejected for the training course to become an evangelist, they urged him to take a different path and try a practical occupation. In their eyes he remained ‘obstinate and pigheaded’, however, and refused to take their advice. Vincent dreaded returning home, but he nevertheless paid two short visits to his parents. They found his behaviour so alarming that his father talked openly about having him committed to the hospital for the mentally ill in Geel in Belgium, but this idea met with fierce resistance from Vincent.

Now that their eldest son had been found wanting, it was Theo’s responsibility to uphold the family honour. In November 1879 he had been given a permanent position with Goupil & Cie in Paris, so he was now able to contribute to his brother’s upkeep. Vincent received his first allowance from Theo in March 1880. He had been doing more drawing, and Theo began urging him to make art his profession. Vincent decided to give it a try; this choice proved definitive.

Vincent threw himself passionately into a self-devised programme of study. Hoping to earn a living as an illustrator, he turned his full attention to drawing. Because he knew that he had to start from scratch, learning as much as possible about materials, perspective, proportion and anatomy, he read handbooks and worked from morning to night, making copies after prints by famous masters, such as Jean-François Millet, and from the examples in the drawing course Theo had sent him.

CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT: Anton Mauve, date of photograph unknown; Kee Vos-Stricker and her son Jan, c. 1881; Anthon van Rappard, c. 1880

Vincent was living with a miner’s family in Cuesmes, and in July 1880 he rented a small atelier in the house next door where he could work. This was far from ideal as a studio, however. The lack of space and a growing need to be near museums and artists prompted him to move to Brussels, where he found lodgings at 72 boulevard du Midi. Among the artists he met in Brussels was an acquaintance of Theo’s, Anthon van Rappard, a Dutch artist who allowed Van Gogh to work in his spacious studio. It was the beginning of a friendship that would last throughout Van Gogh’s stay in the Netherlands and which fulfilled his longing to exchange ideas with a fellow artist.

On the advice of the painter Willem Roelofs – whom Theo had advised him to visit – Van Gogh enrolled as a student at the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts for the course ‘Drawing from the Antique’. After a month he had had enough: no doubt he had been forced to endure much criticism of his under-developed technique and limited knowledge of anatomy and perspective. As a result of that experience, Vincent was filled with loathing for academic instruction – a subject that would crop up often in his letters – and believed even more strongly that an artist’s means of expression was more important than technique.

On 1 February 1881 Theo was appointed manager of Goupil’s branch on the boulevard Montmartre in Paris (later taken over by Boussod, Valadon & Cie), and from then on he decided to shoulder all Vincent’s living expenses.

Lack of money and of a convenient studio space forced Van Gogh to return at the end of April 1881 to his parents’ house in Etten, where he would remain until Christmas. He worked and slept in a room in the annex beside the house. In these months he worked increasingly on figure studies, often out of doors, modelled on locals who posed for him. Anthon van Rappard visited him in mid-June, and they spent almost a fortnight there painting and drawing landscapes.

During a short stay in The Hague, Van Gogh visited museums and exhibitions – not for the first time, but now as an artist – and received welcome advice from Anton Mauve, a successful painter of The Hague School who was married to Van Gogh’s cousin, Jet Carbentus. Vincent was in his element; upon his return to Etten he went back to drawing peasant figures with renewed energy, and quoting a phrase used by Mauve, he observed with satisfaction that ‘the factory is in full swing’ (172).

In the summer of 1881, Kee Vos, the widowed daughter of Uncle Stricker, came to stay with the family at the parsonage. Van Gogh fell passionately in love with her, although he did not mention this in his letters to his brother until November. She was adamant from the beginning that she could never return his feelings, yet Van Gogh persisted relentlessly in his pursuit of her, unshakable in his conviction that she could, and would, come to love him; he even made her a proposal of marriage. His reckless desire for her deeply embarrassed his parents, who considered him to be shaming the family, and his father warned Vincent that he risked breaking family ties with his ‘indelicate and untimely’ behaviour. Vincent, however, grew ever more hostile to his family’s opinions and sensitivities. By the end of the year the situation reached breaking point.

At Christmas, after an angry row during which he told his clergy-man father he wanted nothing more to do with religion, Vincent was asked to leave the house. Furious, he left that same day for The Hague.

Van Gogh set himself up in a modest studio at Schenkweg 138, at the edge of the city. He was still suffering from the negative reactions to his love for Kee, and abhorred his family’s shortsightedness. Although Theo accused Vincent of making their parents’ lives ‘miserable and nearly impossible’, he continued to support him. Theo, who made a good living throughout Vincent’s artistic career, gave some fifteen per cent of his income to his brother. Vincent’s tendency to spend money too easily was a habit inseparable from his unrelenting passion for work: he was always running out of drawing and painting materials; he needed models, who had to be paid to pose; and he was determined to find adequate living and working quarters every time he moved house.

His early days in The Hague, then the cultural capital of the Netherlands, started off well: he received advice and support from Tersteeg, his former boss at Goupil’s, and Mauve, who introduced him at the painters’ society Pulchri Studio, the ideal place to draw from a model and meet other artists. Within just a few months, however, relations between Van Gogh and both these men begun to sour as their disapproval of his lifestyle and attitudes mounted. They disapproved in particular of Van Gogh’s relations with Sien Hoornik, a pregnant former prostitute who became his regular model. Sien’s mother and daughter also posed for him frequently, at first for a fee, and later, when he and Sien became lovers, for free.

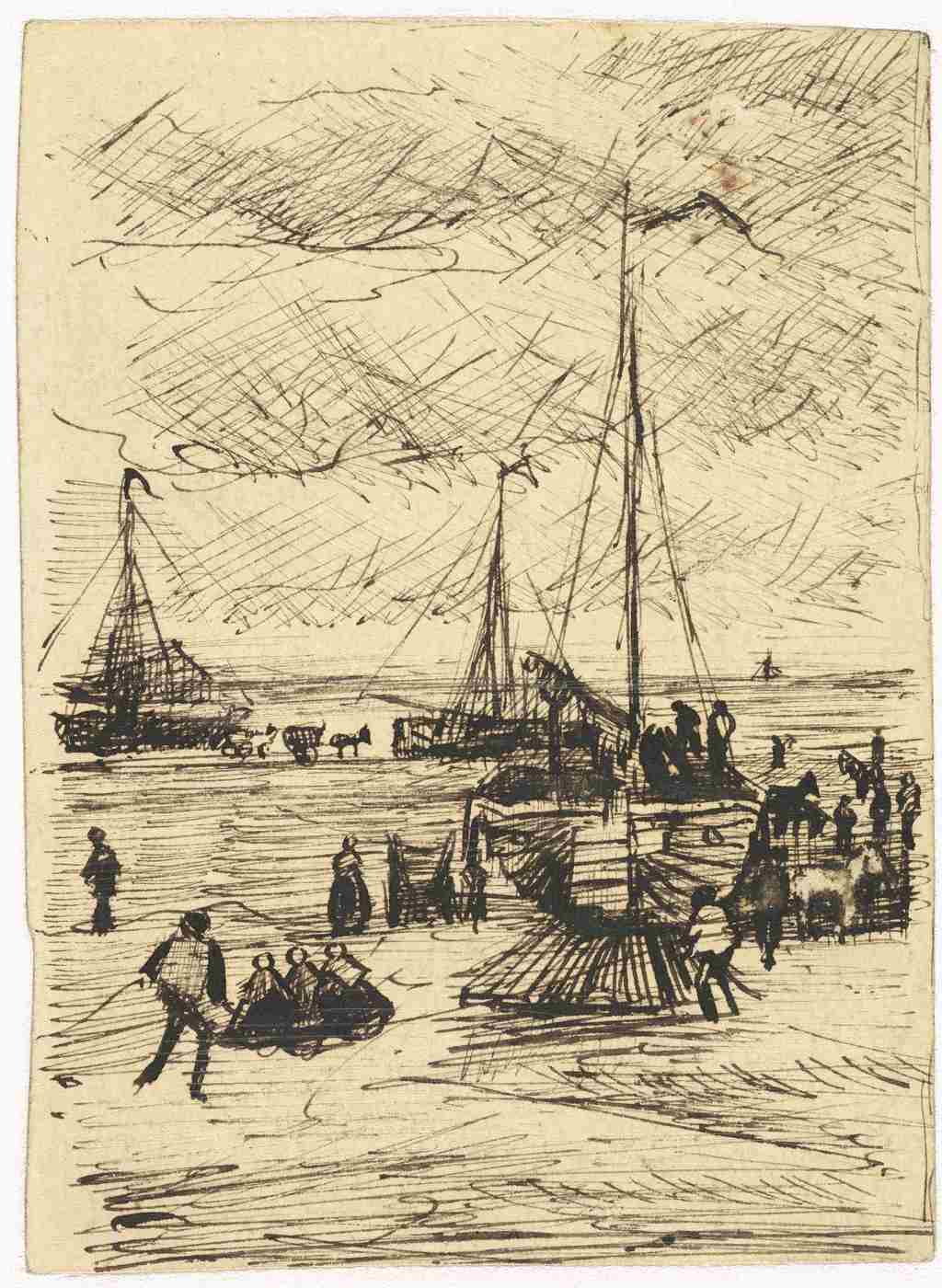

Vincent made contact with other artists in The Hague, among them George Breitner, and produced many drawings, as well as two series of cityscapes for his Uncle Cor. His favourite subjects were workers and impoverished people. He hoped that his art would reach ordinary folk; he wanted to make figures ‘from the people for the people’ (294). Still thinking of becoming an illustrator, he collected hundreds of illustrated magazines. The prints in these magazines – wood engravings made by professional engravers after drawings by well-known artists – moved him with their realism, immediacy and unpolished technique.

Vincent exchanged prints with Van Rappard, and their letters contained long discussions about artistic and technical questions. At this time he also read Alfred Sensier’s La vie et l’oeuvre de Jean-François Millet (published in English as Jean-François Millet, Peasant and Painter), a highly romanticized biography of the Barbizon painter who led a simple life among peasants which would become of crucial importance to his views about the role of the artist.

In June Van Gogh spent several weeks in hospital being treated for venereal disease. During this time a reconciliation came about between him and his parents. Learning of Vincent’s condition, his father travelled to The Hague to visit him. On leaving hospital, Vincent moved to a better and more spacious studio farther down the street. Two weeks later he was joined by Sien, her five-year-old daughter, Maria and her newborn son, Willem. When he broke this news to Theo, Vincent tried to deflect criticism by citing Michelet’s ethical and didactic books about women, love and marriage, and went on to defend his relationship with Sien repeatedly and vehemently in the face of strong condemnation, especially from Tersteeg and the conservative Van Gogh family. Vincent’s letters reveal his version of reality: a man is duty-bound to help a fallen woman, and it stands to reason that this will cost money. His idea of respectability was obviously very different from that of most people of his social background. He dressed like a member of the working class, to the dismay of Theo and the rest of the family.

Once Vincent was established in his new studio, he settled into a rare period of relative calm that enabled him to focus more intently on his art. He made landscape studies in watercolours and oils and many drawings of working men and women, and also started to experiment with lithography and a large variety of drawing materials. He sent Theo drawings of folk types, town views and landscapes; his letters are full of exuberant and lyrical descriptions of colour.

In August 1883, Vincent began making plans to leave for the rural province of Drenthe, recommended to him by his artist friends for the beauty of its countryside. He was anxious to leave as soon as possible to capture the autumn colours and to start work on rustic scenes in the vein of the Barbizon and Hague School artists. In an atmosphere of growing mistrust, his relationship with Sien ended, but he worried about leaving her since he was sure that her family would lead her back into prostitution.

To Theo van Gogh (letter 160)

Brussels, 1 Nov.

72 blvd du Midi

My dear Theo,

I want to tell you a few things in reply to your letter.

First of all, that I went to see Mr Roelofs the day after I received your letter, and he told me that his opinion was that from now on I should concentrate on drawing from nature, i.e. whether plaster or model, but not without guidance from someone who understands it well. And he, and others too, seriously advised me definitely to go and work at a drawing academy, at least for a while, here or in Antwerp or anywhere I could, so I think I should in fact do something about getting admitted to that drawing academy, although I don’t particularly like the idea. Tuition is free here in Brussels, I hear that in Amsterdam, for example, it costs 100 guilders a year, and one can work in an adequately heated and lighted room, which is worth thinking about, especially for the winter.

I’m making headway with the examples of Bargue, and things are progressing. Moreover, I’ve recently drawn something that was a lot of work but I’m glad to have done it. Made, in fact, a pen drawing of a skeleton, rather large at that, on 5 sheets of Ingres paper.

1 sheet the head, skeleton and muscles

1 ,, torso, skeleton

1 ,, hand from the front, skeleton and muscles

1 ,, ,, from the back, ,, ,,

1 ,, pelvis and legs, skeleton.

I was prompted to do it by a manual written by Zahn, Esquisses anatomiques à l’usage des artistes. And it includes a number of other illustrations which seem to me very effective and clear. Of the hand, foot &c. &c.

And what I’m now going to do is complete the drawing of the muscles, i.e. that of the torso and legs, which will form the whole of the human body with what’s already made. Then there’s still the body seen from the back and from the side.

So you see that I’m pushing ahead with a vengeance, those things aren’t so very easy, and require time and moreover quite a bit of patience.

To be admitted to the drawing academy one must have permission from the mayor and be registered. I’m waiting for an answer to my request.

I know, of course, that no matter how frugally, how poorly even, one lives, it will turn out to be more expensive in Brussels than in Cuesmes, for instance, but I shan’t succeed without any guidance, and I think it possible — if I only work hard, which I certainly do — that either Uncle Cent or Uncle Cor will do something, if not as a concession to me at least as a concession to Pa.

It’s my plan to get hold of the anatomical illustrations of a horse, cow and sheep, for example, from the veterinary school, and to draw them in the same way as the anatomy of a person.

There are laws of proportion, of light and shadow, of perspective, that one must know in order to be able to draw anything at all. If one lacks that knowledge, it will always remain a fruitless struggle and one will never give birth to anything.

That’s why I believe I’m steering a straight course by taking matters in hand in this way, and want to try and acquire a wealth of anatomy here this winter, it won’t do to wait longer and would ultimately prove to be more expensive because it would be a waste of time.

I believe that this will also be your point of view.

Drawing is a hard and difficult struggle.

If I should be able to find some steady work here, all the better, but I don’t dare count on it yet, because I must first learn a great many things.

Also went to see Mr Van Rappard, who now lives at rue Traversière 64, and have spoken to him. He has a fine appearance, I’ve not seen anything of his work other than a couple of small pen drawings of landscapes. But he lives rather sumptuously and, for financial reasons, I don’t know whether he’s the person with whom, for instance, I could live and work. But in any case I’ll go and see him again. But the impression I got of him was that there appears to be seriousness in him.

In Cuesmes, old boy, I couldn’t have stood it a month longer without falling ill with misery. You mustn’t think that I live in luxury here, for my food consists mainly of dry bread and some potatoes or chestnuts which people sell on the street corners, but I’ll manage very well with a slightly better room and by eating a slightly better meal from time to time in a restaurant if that were possible. But for nearly 2 years I endured one thing and another in the Borinage, that’s no pleasure trip. But it will easily amount to something more than 60 francs and really can’t be otherwise. Drawing materials and examples, for instance, for anatomy, it all costs money, and those are certainly essentials, and only in this way can it pay off later, otherwise I’ll never succeed.

I had great pleasure lately in reading an extract from the work by Lavater and Gall. Physiognomie et phrénologie. Namely character as it is expressed in facial characteristics and the shape of the skull.

Drew The diggers by Millet after a photo by Braun that I found at Schmidt’s and which he lent me with that of The evening angelus. I sent both those drawings to Pa so that he could see that I’m doing something.

Write to me again soon. Address 72 blvd du Midi. I’m staying in a small boarding-house for 50 francs a month and have my bread and a cup of coffee here, morning, afternoon and evening. That isn’t very cheap but it’s expensive everywhere here.

The Holbeins from the Modèles d’apres les maitres are splendid, I notice that now, drawing them, much more than before. But they aren’t easy, I assure you.

That Mr Schmidt was entangled in a money matter which would involve the Van Gogh family and for which he, namely Mr S., would be justly prosecuted, I knew not the slightest thing about all that when I went to see him, and I first learned of it from your letter. So that was rather unfortunate, though Mr Schmidt received me quite cordially all the same. Knowing it now, though, and matters being as they are, it would perhaps be wise not to go there often, without it being necessary deliberately to avoid meeting him.

I would have written to you sooner but was too busy with my skeleton.

I believe that the longer you think about it the more you’ll see the definite necessity of more artistic surroundings for me, for how is one supposed to learn to draw unless someone shows you? With the best will in the world one cannot succeed without also coming into and remaining in contact with artists who are already further along. Good will is of no avail if there’s absolutely no opportunity for development. As regards mediocre artists, to whose ranks you think I should not want to belong, what shall I say? That depends on what one calls mediocre. I’ll do what I can, but in no way do I despise the mediocre in its simple sense. And one certainly doesn’t rise above that level by despising that which is mediocre, in my opinion one must at least begin by having some respect for the mediocre as well, and by knowing that that, too, already means something and that one doesn’t achieve even that without much effort. Adieu for today, I shake your hand in thought. Write again soon if you can.

Vincent

To Theo van Gogh (letter 172)

My dear Theo,

Even though I wrote to you only a short while ago, this time I have something more to say to you.

Namely that a change has come about in my drawing, both in my manner of doing it and in the result.

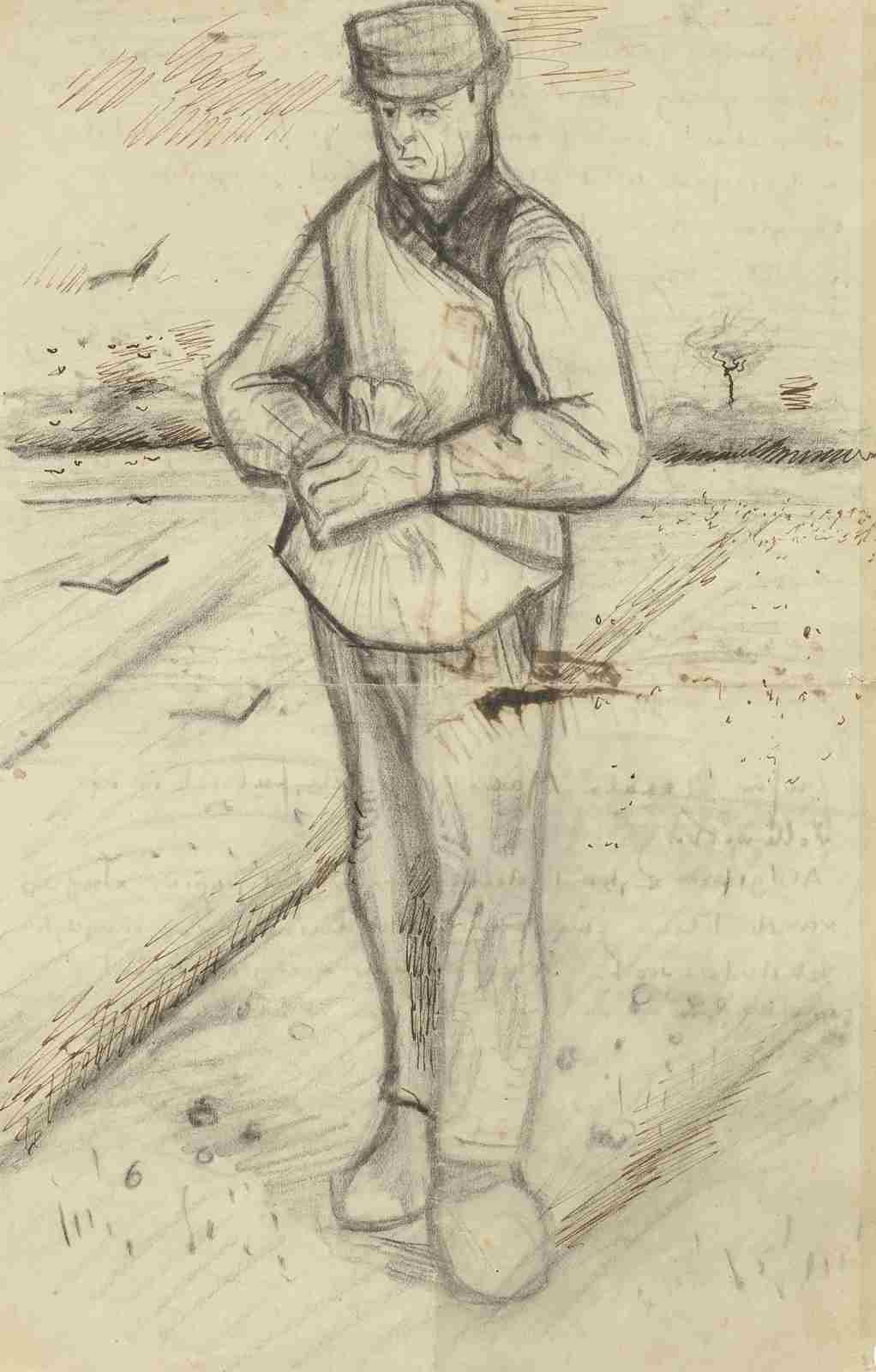

Prompted as well by a thing or two that Mauve said to me, I’ve started working again from a live model. I’ve been able to get various people here to do it, fortunately, one being Piet Kaufmann the labourer.

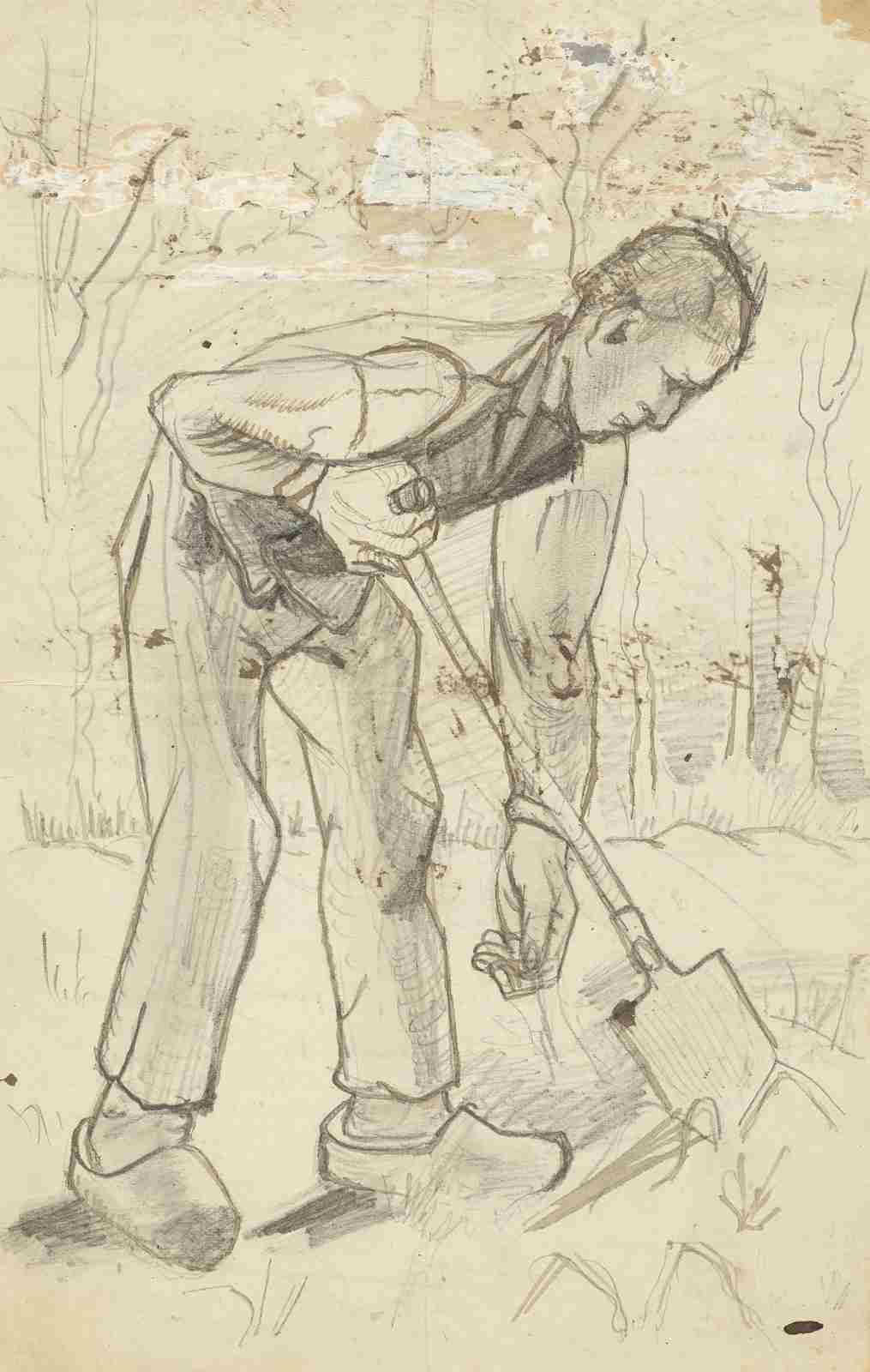

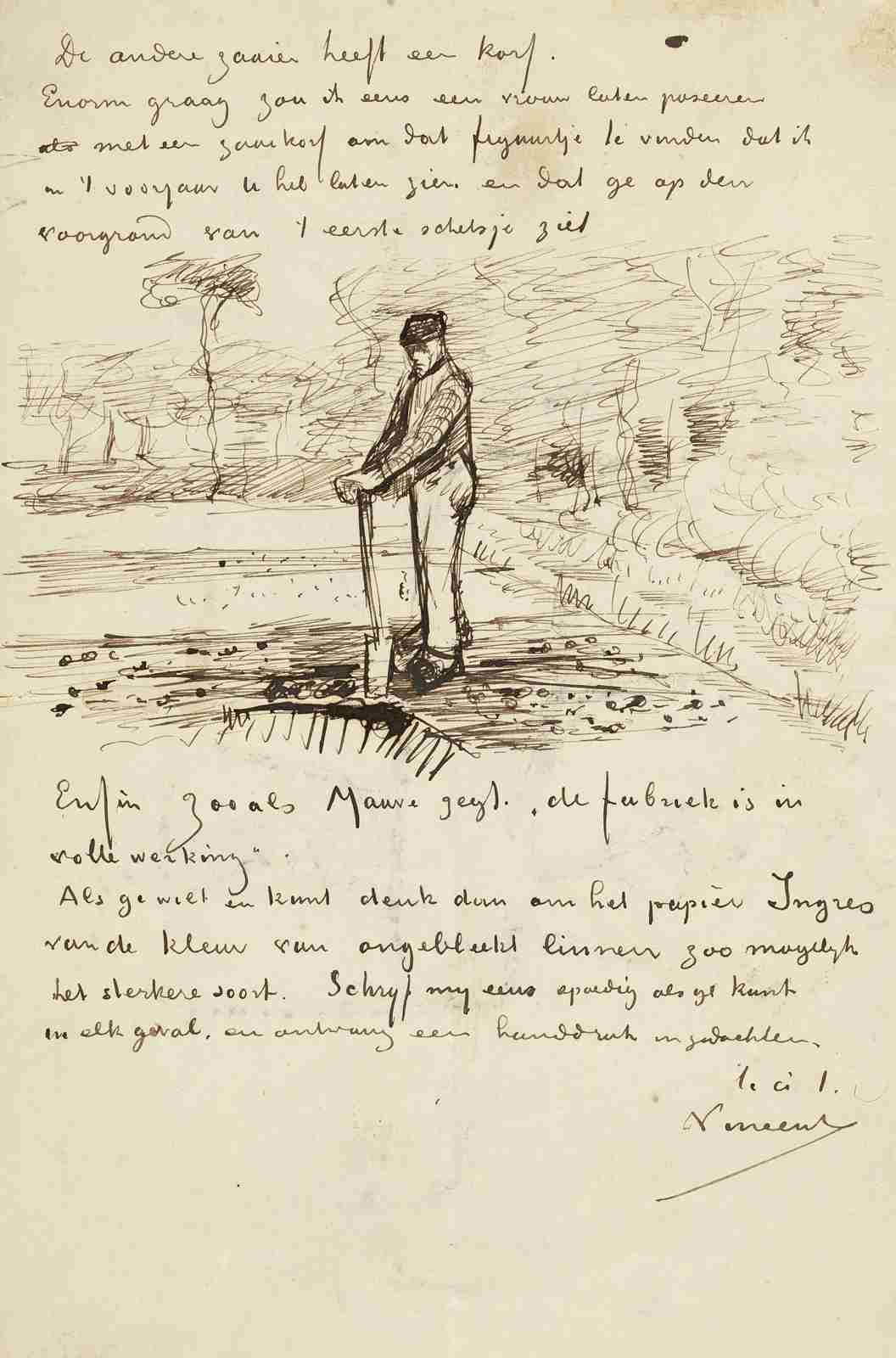

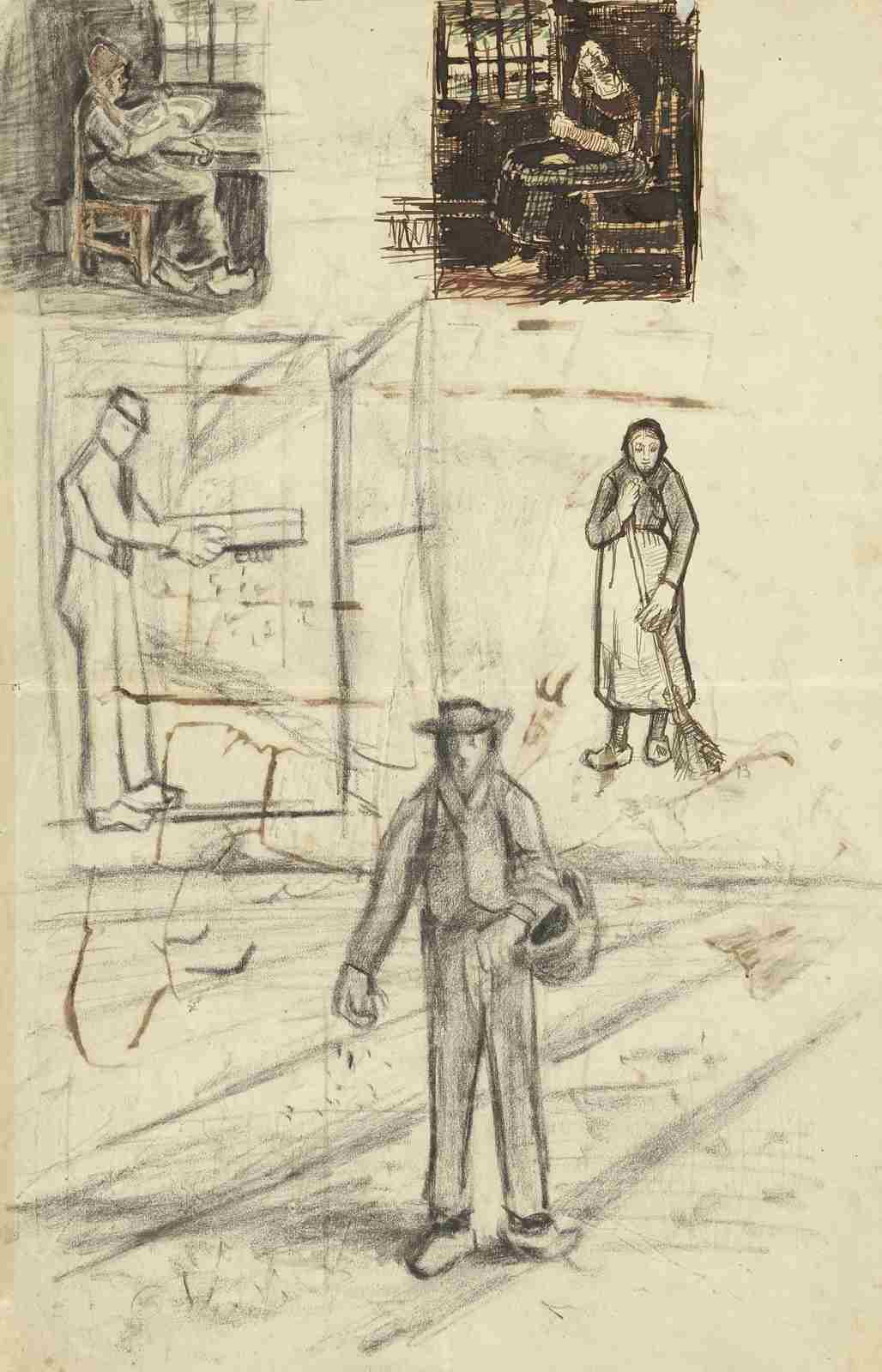

The careful study, the constant and repeated drawing of Bargue’s Exercices au fusain has given me more insight into figure drawing. I’ve learned to measure and to see and to attempt the broad outlines &c. So that what used to seem to me to be desperately impossible is now gradually becoming possible, thank God. I’ve drawn a peasant with a spade no fewer than 5 times, ‘a digger’ in fact, in all kinds of poses, twice a sower, twice a girl with a broom. Also a woman with a white cap who’s peeling potatoes, and a shepherd leaning on his crook, and finally an old, sick peasant sitting on a chair by the fireplace with his head in his hands and his elbows on his knees.

And it won’t stop there, of course, once a couple of sheep have crossed the bridge the whole flock follows.

Diggers, sowers, ploughers, men and women I must now draw constantly. Examine and draw everything that’s part of a peasant’s life. Just as many others have done and are doing. I’m no longer so powerless in the face of nature as I used to be.

I brought Conté in wood (and pencils as well) from The Hague, and am now working a lot with it.

I’m also starting to work with the brush and the stump. With a little sepia or indian ink, and now and then with a bit of colour.

It’s quite certain that the drawings I’ve been making lately don’t much resemble anything I’ve made up till now.

The size of the figures is more or less that of one of the Exercices au fusain.

As regards landscape, I maintain that that should by no means have to suffer on account of it. On the contrary, it will gain by it. Herewith a couple of little sketches to give you an idea of them.

Of course I have to pay the people who pose. Not very much, but because it’s an everyday occurrence it will be one more expense as long as I fail to sell any drawings.

But because it’s only rarely that a figure is a total failure, it seems to me that the cost of models will be completely recouped fairly soon already.

For there’s also something to be earned in this day and age for someone who has learned to seize a figure and hold on to it until it stands firmly on the paper. I needn’t tell you that I’m only sending you these sketches to give you an idea of the pose. I scribbled them today quickly and see that the proportions leave much to be desired, certainly more so than in the actual drawings at any rate. I’ve had a good letter from Rappard who seems to be hard at work, he sent me some very nice sketches of landscapes. I’d really like him to come here again for a few days.

[sketch A] This is a field or stubble field which is being ploughed and sown, I have a rather large sketch of it with a storm brewing.

[sketch B] The other two sketches are poses of diggers. I hope to make several more of these.

[sketches C, D] The other sower has a basket.

It would give me tremendous pleasure to have a woman pose with a seed basket in order to find that figure that I showed you last spring and which you see in the foreground of the first sketch.

172A–C (top to bottom). Storm clouds over a field; Digger; Figure of a woman

172D. Digger

[sketch E] In short, ‘the factory is in full swing’, as Mauve says.

Remember that Ingres paper, if you will, of the colour of unbleached linen, the stronger kind if possible. In any case, write to me soon if you can, and accept a handshake in thought.

172E. Man leaning on his spade

Ever yours,

Vincent

[sketches F–L]

172F. Man sitting by the fireplace (‘Worn out’)

172G–K (LEFT TO RIGHT, TOP TO BOTTOM). Woman near a window; Woman near a window; Man with a winnow; Woman with a broom; Sower

172L. Sower with a sack

To Theo van Gogh (letter 186)

Friday evening.

Dear Brother,

When I sent my letter to you this morning, meaning when I put it in the post-box, I had a feeling of relief. For a moment I’d hesitated, should I tell him or not? But thinking it over later it seemed to me that it really wasn’t unwarranted. I’m writing to you here in the little room that’s now my studio because the other is so damp. When I look round it’s full of all kinds of studies that all relate to one and the same thing, ‘Brabant types’.

So that is work started, and if I were wrenched from this environment I’d have to start all over again doing something else and this would come to a standstill, half-finished! That mustn’t happen! I’ve now been working here since May, I’m getting to know and understand my models, my work is progressing, though it’s taken a lot of hard work to get into my stride. And now that I’ve got into my stride, should Pa say, because you’re writing letters to Kee Vos, thereby causing difficulties between us (because this is the fundamental cause, and no matter what they might say: that I don’t obey the ‘rules of decorum’ or whatever, it’s all just idle talk), so because difficulties have arisen I curse you and drive you out of the house.

That’s really too bad, after all, and it would indeed be ridiculous to stop working for such a reason on a project that’s already started and progressing well.

No, no, one can’t just let that happen. Anyway, the difficulties between Pa and Ma and myself aren’t so terrible, aren’t at all of the kind that would keep us from staying together. But Pa and Ma are getting old, and sometimes they get a little angry, and they have their prejudices and old-fashioned ideas that neither you nor I can share any more.

If, for example, Pa sees me with a French book by Michelet or V. Hugo in my hand, he thinks of arsonists and murderers and ‘immorality’. But that’s just too silly, and of course I don’t let idle talk of that kind upset me. I’ve already said so often to Pa: just read a book like this, even if only a couple of pages, and you’ll be moved by it. But Pa stubbornly refuses to do so. Just now, when this love was taking root in my heart, I read Michelet’s books L’amour and La femme again, and so many things became clear to me that would otherwise remain a mystery. I also told Pa frankly that in the circumstances I valued Michelet’s advice more than his, and had to choose which of the two I should follow. But then they come with a story about a great-uncle who had become obsessed with French ideas and had taken to drink, thus insinuating that such will be my career in life. What misery!

Pa and Ma are extremely good to me inasmuch as they do what they can to feed me well &c. I appreciate that very much, but that doesn’t alter the fact that eating and drinking and sleeping isn’t enough, that one yearns for something nobler and higher, indeed, one simply can’t do without it.

That higher thing I can’t do without is my love for Kee Vos. Pa and Ma reason, She says no, nay, never, so you must remain silent.

I can’t accept that at all, on the contrary. And if I write to her or something like that then there are ugly words like ‘coercion’ and ‘it won’t help anyway’ and ‘you’ll spoil things for yourself’. And then they’re surprised if someone doesn’t just resign himself to finding his love ‘indelicate’! No, truly not! In my opinion, Theo, I must stay here and quietly go on working and do everything in my power to win Kee Vos’s love and to melt the no, nay, never. I can’t share Pa and Ma’s view that I shouldn’t write or speak either to her or to Uncle Stricker; indeed, I feel the exact opposite. And I’d rather give up the work started and all the comforts of this house than resign myself one iota to leaving off writing to her or her parents or you. If Pa curses me for it, then I can’t prevent His Hon. from doing so. If he wants to throw me out of the house, so be it, but I’ll continue to do what my heart and mind tell me to do with respect to my love.

Be assured, Pa and Ma are actually against it, because otherwise I can’t explain why they went so far this morning, so it now seems to me that it was a mistake for me ever to think that they didn’t care one way or the other. Anyhow, I’m writing to you about it because, where my work is involved, that is definitely your concern, since you’re the one who has already spent so much money on helping me to succeed. Now I’ve got into my stride, now it’s progressing, now I’m starting to see something in it, and now I tell you, Theo, this is hanging over me. I’d like nothing better than simply to go on working, but Pa seems to want to curse me and put me out of the house, at least he said so this morning. The reason is that I write letters to Kee Vos. As long as I do that, at any rate, Pa and Ma will always find something to reproach me with, whether that I don’t obey the rules of decorum or that I have an indelicate way of expressing myself or that I’m breaking ties or something of the kind.

A forceful word from you could perhaps straighten things out. You will understand what I tell you, that to work and be an artist one needs love. At least someone who strives for feeling in his work must first feel and live with his heart.

But Pa and Ma are harder than stone on the point of ‘a means of subsistence’, as they call it.

If it were a question of marrying at once, I’d most certainly agree with them, but NOW it’s a question of melting the no, nay, never, and a means of subsistence can’t do that.

That’s an entirely different matter, an affair of the heart, for to make the no, nay, never melt, she and I must see each other, write to each other, speak to each other. That’s as clear as day and simple and reasonable. And truly (though they take me to be a weak character, ‘a man of butter’), I won’t let anything in the world deter me from this love. May God help me in this.

No putting it off from today to tomorrow, from tomorrow to the next day, no silent waiting. The lark can’t be silent as long as it can sing. It’s absurd, utterly absurd, to make someone’s life difficult for this reason. If Pa wants to curse me for it, that’s his business – my business is to try and see Kee Vos, to speak to her, to write to her, to love her with everything in me.

You’ll understand that a father shouldn’t curse his son because that son doesn’t obey the rules of decorum or expresses himself indelicately or other things, assuming this were all true, though I think it’s actually very different.

But unfortunately it’s something that happens all too often in many families, that a father curses his son because of a love the parents disapprove of.

THAT’S the rub, the other — rules of decorum &c., expressions, the tone of my words — those are just pretexts. What should we do now?

Wouldn’t it be foolish, Theo, not to go on drawing those Brabant folk types, now that I’m making progress, just because Pa and Ma are vexed by my love?

No, that mustn’t happen. Let them accept it, for God’s sake, that’s what I think. It really would be mad to expect a young man to sacrifice his energy to the prejudice of an old man. And truly, Pa and Ma are prejudiced in this.

Theo, I still haven’t heard one word of love towards her, and to tell you the truth that is what bothers me more than anything else.

I don’t think that Pa and Ma love her deep down, at any rate in the mood they’re in now they can’t think of her with love. But I hope this will change in later and better days. No, no, no, there’s something wrong with them, and it can’t be good that they curse me and want me out of the house at this very time. There are no grounds for it and it would thwart me in my work. So it can’t be allowed to happen for no good reason.

What would she think if she knew what happened this morning? How would she like it, even though she says no, nay, never, if she heard that they called my love for her indelicate and spoke of ‘breaking ties’ &c. No, Theo, if she’d heard Pa cursing me, she wouldn’t have approved of his curse. Ma once called her ‘such a poor wee thing’ in the sense of so weak, so nervous or whatever.

But be assured that lurking in ‘that poor wee thing’ is strength of mind and pride, energy and resoluteness that could change the minds of many towards her, and I maintain that sooner or later one might see things from ‘that poor wee thing’ that very few now expect! She’s so good and friendly that it pains her deeply to say one single unfriendly word, but if such as her, so gentle, so tender, so loving, rebel — piqued to the quick — then woe betide those they rebel against.

May she not rebel against me, then, dear brother. I think that she is beginning to see that I’m not an intruder or bully, but rather quieter and calmer on the inside than I seem on the surface. She didn’t realize that immediately. At first, for a time, she really had an unfavourable opinion of me, but lo and behold, I don’t know why, while the sky clouds over and darkens with difficulties and curses, light rises up on her side. Pa and Ma have always passed for such gentle, quiet people, so kindly and good. But how can I reconcile that with this morning’s scene or that matter of Geel last year?

They really are good and kindly, but even so, they have prejudices they want to impose. And if they want to act as the ‘wall of partition’ between me and her, I doubt whether it will do them any good.

Now, old chap, if you send me some ‘travelling money’ you’ll soon receive 3 drawings, ‘Mealtime’, ‘the fire-lighter’ and ‘an almsman’. So send the travelling money, if you can, for the journey won’t be completely in vain! If I have but 20 or 30 francs, at least I can see her face once again. And write a word or two, if you will, about that certain (terrible?) curse and that banishment, because I’d like so much to go on working quietly here, that’s what I’d like best. I need her and her influence to reach a higher artistic level, without her I am nothing, but with her there’s a chance. Living, working and loving are actually one and the same thing. Now, adieu with a handshake,

Ever yours,

Vincent

A word from you ‘from Paris’! That would possibly carry some weight, even against prejudices.

That matter of the asylum happened last year ‘out of a conscientious conviction’, as they call it, now it’s another ‘conscientious conviction’ that’s forbidding me to write to Kee Vos. But that’s simply a ‘conscientious conviction’ based on very slight grounds, one that doesn’t hold water. No, it can’t be allowed to happen for no good reason!

And if one asks Pa, ‘Explain to me the basis of your conviction’, he answers, ‘I don’t owe you an explanation’, ‘it’s not fitting to ask your father such a question’. That, however, is no mode of reasoning!

Another mode of reasoning that I don’t understand either is Ma’s: You know that we’ve been against it from the beginning, so stop going on about it! No, listen to me, brother, it would really be too bad if I had to leave my field of work here and waste a lot of money elsewhere, where it’s much more expensive, instead of gradually earning some ‘travelling money’!

That matter of Geel last year, when Pa wanted to have me put in an asylum against my will!!! taught me to be on the qui vive. If I didn’t watch out now, Pa would ‘feel compelled to do’ a thing or two.

To Theo van Gogh (letter 193)

Sometimes, I fear, you throw a book away because it’s too realistic. Have compassion and patience with this letter, and read it through, despite its severity.

My dear Theo,

As I already wrote to you from The Hague, I have some things to discuss with you now that I’m back here. It’s not without emotion that I look back on my trip to The Hague. When I went to see M. my heart was beating rather hard, because I was thinking to myself, will he too try and fob me off or will I find something else here? And well, what I experienced with him was that he instructed and encouraged me in all manner of kind and practical ways. Though not merely by always approving of everything I did or said, on the contrary. But if he tells me, this or that isn’t good, then it’s because he’s saying at the same time ‘but try it this way or that way’, and that’s entirely different from criticizing for the sake of criticizing. Or if someone says ‘you’re ill with this or that’, that doesn’t help much, but if someone says ‘do this or that and you’ll get better’, and his advice isn’t deceit, look, that’s the real thing, and – and – it naturally helps. Now I’ve come from him with a few painted studies and a couple of watercolours. Of course they aren’t masterpieces and yet I truly believe there’s something sound and real in them, more at least than in what I’ve made up to now. And so I now consider myself to be at the beginning of the beginning of making something serious. And because I now have a few more technical resources at my disposal, namely paint and brush, all things are made new again, as it were.

But – now we have to put it into practice. And the first thing is that I must find a room large enough to be able to take a sufficient distance. Mauve just said to me, when he saw my studies, ‘you’re too close to your model’.

In many cases this makes it next to impossible to take the necessary measurements for the proportions, so this is certainly one of the first things I have to watch out for. Now I must arrange to rent a large room somewhere, be it a room or a shed. And that won’t be so terribly expensive. A labourer’s cottage in these parts costs 30 guilders a year to rent, so it seems to me that a room twice as large as that in a labourer’s cottage would cost something like 60 guilders.

And that isn’t insurmountable. I’ve already seen a shed, though it has too many inconveniences, especially in the winter. But I’d be able to work there, at least when the weather is milder. And here in Brabant, moreover, there are models to be found, I believe, not only in Etten but also in other villages, if difficulties were to arise here.

Still, though I love Brabant very much, I also have a feeling for other figures than the Brabant peasant types. Scheveningen, for example, I again found unspeakably beautiful. But after all I’m here, and it would very probably be cheaper to stay here. However, I’ve definitely promised M. that I’ll do my utmost to find a good studio, and now I must also use better paint and better paper.

Nevertheless, Ingres paper is excellent for studies and scratches. And it’s much cheaper to make sketchbooks in all formats from it oneself than to buy ready-made sketchbooks. I still have a small supply of Ingres paper, but you’d be doing me a big favour if you could send some more of the same kind when you send back those studies. Not pure white, though, but the colour of unbleached linen, no cold shades.

Theo, what a great thing tone and colour are! And anyone who doesn’t acquire a feeling for it, how far removed from life he will remain! M. has taught me to see so many things I didn’t see before, and when I have the opportunity I’ll try and tell you about what he’s told me, because perhaps there are still one or two things that you don’t see properly either. Anyway, we’ll talk about artistic matters sometime, I hope.

And you can’t imagine the feeling of relief I’m beginning to get when I think of the things M. said to me about earning money. Just think of how I’ve slogged away for years, always in a kind of false position. And now, now there’s a glimmer of real light.

I do wish that you could see the two watercolours I’ve brought with me, because you would see that they’re watercolours just like any other watercolours. There may be many imperfections in them, be that as it may, I’d be the first to say that I’m still very dissatisfied with them, and yet, it’s different from what I’ve done up to now, and it looks fresher and sounder. All the same, it must become much fresher and sounder, but one can’t do what one wants all at once. It comes gradually. I need those couple of drawings myself, however, to compare with what I’ll be making here, because I have to do them at least as well as what I did at M.’s.

But even though Mauve tells me that if I continue to slog away here for a couple of months and then go back to him again in March, for instance, I’ll then be able to make saleable drawings on a regular basis, I’m nevertheless going through a rather difficult period. The cost of models, studio, drawing and painting materials are multiplying, and there are no earnings as yet.

Admittedly, Pa said that I needn’t be afraid of the inevitable expense, and Pa is pleased with what M. himself said to him, and also with the studies and drawings I brought back. But I do find it utterly, utterly wretched that Pa should suffer by it. Of course we hope that things will turn out well later, but still, it weighs heavily on my heart. Because since I’ve been here Pa really hasn’t profited from me, and more than once he’s bought a coat or trousers, for example, which I’d actually rather not have had, even though I really needed it, but Pa shouldn’t suffer by it. The more so if the coat and trousers in question don’t fit and are only half or not at all what I need. Anyway, still more petty vexations of human life. And, as I’ve told you before, I find it absolutely terrible not to be free at all. Because even though Pa doesn’t ask me to account for literally every penny, still, he always knows exactly how much I spend and what I spend it on. And now, although I don’t necessarily have any secrets, I don’t really like people being able to look at my cards. Even my secrets aren’t necessarily secrets to those for whom I feel sympathy.

But Pa isn’t the kind of man for whom I can feel what I feel for you, for example, or for Mauve. I really do love Pa and Ma, but it’s a very different feeling from what I feel for you or Mauve. Pa cannot empathize or sympathize with me, and I cannot settle in to Pa and Ma’s routine, it’s too constricting for me — it would suffocate me.

Whenever I tell Pa anything, it’s all just idle talk to him, and certainly no less so to Ma, and I also find Pa and Ma’s sermons and ideas about God, people, morality, virtue, almost complete nonsense. I also read the Bible sometimes, just as I sometimes read Michelet or Balzac or Eliot, but I see completely different things in the Bible than Pa sees, and I can’t agree at all with what Pa makes of it in his petty, academic way. Since the Rev. Ten Kate translated Goethe’s Faust, Pa and Ma have read that book, because now that a clergyman has translated it, it can’t be all that immoral (??? what is that?). Yet they don’t see anything in it but the catastrophic consequences of an unchaste love.

And they certainly understand the Bible just as little. Take Mauve, for instance, when he reads something deep he doesn’t immediately say, that man means this or that. Because poetry is so deep and intangible that one can’t simply define it all systematically, but Mauve has a refined sensibility and, you see, I find that sensibility to be worth so much more than definition and criticism. And oh, when I read, and I actually don’t read so much and even then, only one-and-a-half writers, a couple of men whom I accidentally found, then I do so because they look at things more broadly and milder and with more love than I do, and are better acquainted with reality, and because I can learn something from them. But all that drivel about good and evil, morality and immorality, I actually care so little about it. For truly, it’s impossible for me always to know what is good, what is evil, what is moral, what is immoral.

Morality or immorality coincidentally brings me to K.V. Ah! I’d written to you that it was beginning to seem less and less like eating strawberries in the spring. Well, that is of course true. If I should lapse into repetition, forgive me, I don’t know if I’ve already written to you about what happened to me in Amsterdam. I went there thinking, who knows whether the no, nay, never isn’t thawing, it’s such mild weather. And so one evening I was making my way along Keizersgracht, looking for the house, and indeed found it. And naturally I rang the bell and heard that the family were still at table. But then I heard that I could come in all the same. And there they were, including Jan, the very learned professor, all of them except Kee. And they all still had a plate in front of them, and there wasn’t a plate too many. This small detail caught my eye. They wanted to make me think that Kee wasn’t there, and had taken away her plate, but I knew she was there, I thought it so much like a comedy or game.

After a while I asked (after chatting a bit and greeting everyone), But where’s Kee? Then J.P.S. repeated my question, saying to his wife, Mother, where’s Kee? And the missus said, Kee’s out. And for the time being I didn’t pursue the matter but talked a bit with the professor about the exhibition at Arti he’d just seen. Well, the professor disappeared and little Jan Vos disappeared, and J.P.S. and the wife of the same and yours truly remained alone and got ourselves into position. J.P.S., as priest and Father, started to speak and said he’d been on the point of sending a certain letter to yours truly and he would read that letter aloud. However, first I asked again, interrupting His Hon. or the Rev., Where’s Kee? (Because I knew she was in town.) Then J.P.S. said, Kee left the house as soon as she heard you were here. Well, I know some things about her, and I must say that I didn’t know then and still don’t know with certainty whether her coldness and rudeness is a good or bad sign. This much I do know, that I’ve never seen her so seemingly or actually cool and callous and rude towards anyone but me. So I didn’t say much in reply and remained dead calm. Let me hear that letter, I said, or not, I don’t really care either way. Then came the epistle. The writing was reverent and very learned and so there wasn’t really anything in it, though it did seem to say that I was being requested to stop corresponding and I was given the advice to make vigorous attempts to forget the matter. At last the reading of the letter was over. I felt exactly as though I were hearing the minister in the church, after some raising and lowering of his voice, saying amen – it left me just as cold as an ordinary sermon. And then I began, and I said as calmly and politely as I could, well yes, I’ve already heard this line of reasoning quite often, but now go on – and after that? But then J.P.S. looked up… he even seemed to be somewhat amazed at my not being completely convinced that we’d reached the extreme limit of the human capacity to think and feel. There was, according to him, no ‘after that’ possible. We went on like this, and once in a while Aunt M. put in a very Jesuitical word, and I got quite warm and finally lost my temper. And J.P.S. lost his temper too, as much as a clergyman can lose his temper. And even though he didn’t exactly say ‘God damn you’, anyone other than a clergyman in J.P.S.’s mood would have expressed himself that way. But you know that I love both Pa and J.P.S. in my own way, despite the fact that I truly loathe their system, and I changed tack a bit and gave and took a bit, so that at the end of the evening they said to me that if I wanted to stay at their house I could. Then I said, thank you. If Kee walks out of the house when I come, then I don’t think it’s the right moment to stay here, I’m going to my boarding-house. And then they asked, where are you staying? I said, I don’t know yet, and then Uncle and Aunt insisted on bringing me themselves to a good, inexpensive boarding-house. And heavens, those two old dears came with me through the cold, misty, muddy streets, and truly, they showed me a very good boarding-house and very inexpensive. I didn’t want them to come at all but they insisted on showing me. And, you see, I thought that rather humane of them and it calmed me down somewhat. I stayed in Amsterdam two more days and talked with J.P.S. again, but I didn’t see Kee, she made herself scarce each time. And I said that they ought to know that although they wanted me to consider the matter over and done with, I couldn’t bring myself to do it. And they continued to reply firmly: ‘Later on I would understand it better’. Now and then I also saw the professor again, and I have to say he wasn’t so bad, but – but – but – what else can I say about that gentleman? I said I hoped that he might fall in love one day. Voilà. Can professors fall in love? Do clergymen know what love is?

I recently read Michelet, La femme, la religion et le prêtre. Books like that are full of reality, yet what is more real than reality itself, and what has more life than life itself? And we who do our best to live, why don’t we live even more!

I walked around aimlessly those three days in Amsterdam, I felt damned miserable, and that half-kindness on the part of Uncle and Aunt and all those arguments, I found them so tedious. Until I finally began to find myself tedious and said to myself: would you like to become despondent again? And then I said to myself, Don’t let yourself be overwhelmed. And so it was on a Sunday morning that I last went to see J.P.S. and said to him, Listen, my dear Uncle, if Kee Vos were an angel she would be too lofty for me, and I don’t think that I would stay in love with an angel. Were she a devil, I wouldn’t want to have anything to do with her. In the present case, I see in her a real woman, with womanly passions and whims, and I love her dearly, that’s just the way it is, and I’m glad of it. So long as she doesn’t become an angel or a devil, the case in question isn’t over. And J.P.S. couldn’t say very much to that, and spoke himself of womanly passions, I’m not really sure what he said about them, and then J.P.S. left for the church. No wonder one becomes hardened and numb there, I know that from my own experience. And so as far as your brother in question is concerned, he didn’t want to let himself be overwhelmed. But that didn’t alter the fact that he felt overwhelmed, that he felt as though he had been leaning against a cold, hard, whitewashed church wall for too long. Oh well, should I tell you more, old chap? It’s rather daring to remain a realist, but Theo, Theo, you too are a realist, oh bear with my realism! I told you, even my secrets aren’t necessarily secrets. Well, I won’t take those words back, think of me as you will, and whether you approve or disapprove of what I did is less important.

I’ll continue – from Amsterdam I went to Haarlem and sat very agreeably with our dear sister Willemien, and I took a walk with her, and in the evening I went to The Hague, and I landed up at M.’s around seven o’clock.

And I said: listen M., you were supposed to come to Etten to try and initiate me, more or less, into the mysteries of the palette. But I’ve been thinking that that wouldn’t be possible in only a couple of days, so now I’ve come to you and if you approve I’ll stay four weeks or so, or six weeks or so, or as long or as short as you like, and we’ll just have to see what we can do. It’s extremely impertinent of me to demand so much of you, but in short, I’m under a great deal of pressure. Well, Mauve said, do you have anything with you? Certainly, here are a couple of studies, and he said many good things about them, far too many, at the same time voicing some criticism, far too little. Well, and the next day we set up a still life and he began by saying, This is how you should hold your palette. And since then I’ve made a few painted studies and after that two watercolours.

This is a summary of my work, but there’s more to life than working with the hands and the head.

I remained chilled to the marrow, that’s to say to the marrow of my soul by that aforementioned imaginary or not-imaginary church wall. And I didn’t want to let myself be overwhelmed by that deadening feeling, I said. Then I thought to myself, I’d like to be with a woman, I can’t live without love, without a woman. I wouldn’t care a fig for life if there wasn’t something infinite, something deep, something real. But, I said to myself in reply: you say ‘She and no other’ and should you go to a woman? But surely that’s unreasonable, surely that goes against logic? And my answer to that was, Who’s the master, logic or I? Is logic there for me or am I there for logic, and is there no reason and no understanding in my unreasonableness or my stupidity? And whether I act rightly or wrongly, I can’t do otherwise, that damned wall is too cold for me, I’ll look for a woman, I cannot, I will not, I may not live without love. I’m only human, and a human with passions at that, I need a woman or I’ll freeze or turn to stone, or anyway be overwhelmed. In the circumstances, however, I struggled much within myself, and in that struggle some things concerning physical powers and health gained the upper hand, things which I believe and know more or less through bitter experience. One doesn’t live too long without a woman without going unpunished. And I don’t think that what some call God and others the supreme being and others nature is unreasonable and merciless, and, in a word, I came to the conclusion, I must see whether I can’t find a woman. And heavens, I didn’t look so very far. I found a woman, by no means young, by no means pretty, with nothing special about her, if you will. But perhaps you’re rather curious. She was fairly big and strongly built, she didn’t exactly have lady’s hands like K.V. but those of a woman who works hard. But she was not coarse and not common, and had something very feminine about her. She slightly resembled a nice figure by Chardin or Frère or possibly Jan Steen. Anyhow, that which the French call ‘a working woman’. She’d had a great many cares, one could see that, and life had given her a drubbing, oh nothing distinguished, nothing exceptional, nothing out of the ordinary.

Every woman, at every age, if she loves and if she is kind, can give a man not the infinite of the moment but the moment of the infinite.

Theo, I find such infinite charm in that je ne sais quoi of withering, that drubbed by life quality. Ah! I found her to have a charm, I couldn’t help seeing in her something by Feyen-Perrin, by Perugino. Look, I’m not exactly as innocent as a greenhorn, let alone a child in the cradle. It’s not the first time I couldn’t resist that feeling of affection, particularly love and affection for those women whom the clergymen damn so and superciliously despise and condemn from the pulpit. I don’t damn them, I don’t condemn them, I don’t despise them. Look, I’m almost thirty years old, and do you think I’ve never felt the need for love?

K.V. is older than I am, she also has love behind her, but she’s all the dearer to me for that very reason. She’s not ignorant, but neither am I. If she wants to subsist on an old love and if she wants to know nothing of new ones, that’s her business, but the more she perseveres in that and avoids me, the more I can’t just stifle my energy and strength of mind for her sake. No, I don’t want that, I love her, but I don’t want to freeze and deaden my mind for her sake. And the stimulus, the spark of fire we need, that is love and I don’t exactly mean mystic love.

That woman didn’t cheat me – oh, anyone who thinks all those sisters are swindlers is so wrong and understands so little.

That woman was good to me, very good, very decent, very sweet. In what way? That I won’t repeat even to my brother Theo, because I strongly suspect my brother Theo of having experienced something of this himself now and then. The better for him.

Did we spend a lot together? No, because I didn’t have much and I said to her, listen, you and I don’t have to get drunk to feel something for one another, just pocket what I can afford. And I wish I could have afforded more, because she was worth it.

And we talked about all kinds of things, about her life, about her cares, about her destitution, about her health, and I had a livelier conversation with her than with my learned professorial cousin Jan Stricker, for instance.

I’ve actually told you these things because I hope you’ll see that even though I perhaps have some feeling, I don’t want to be sentimental in a senseless way. That, no matter what, I want to preserve some warmth of life and keep my mind clear and my body healthy in order to work. And that I understand my love for K.V. to be such that for her sake I don’t want to set about my work despondently or let myself get upset.

You’ll understand that, you who wrote in your letter something about the matter of health. You talk of having been not quite healthy a while back, it’s very good you’re trying to get yourself straightened out.

Clergymen call us sinners, conceived and born in sin. Bah! I think that damned nonsense. Is it a sin to love, to need love, not to be able to do without love? I consider a life without love a sinful condition and an immoral condition. If there’s anything I regret, it’s that for a time I let mystical and theological profundities seduce me into withdrawing too much inside myself. I’ve gradually stopped doing that. If you wake up in the morning and you’re not alone and you see in the twilight a fellow human being, it makes the world so much more agreeable. Much more agreeable than the edifying journals and whitewashed church walls the clergymen are in love with. It was a sober, simple little room she lived in, with a subdued, grey tone because of the plain wallpaper and yet as warm as a painting by Chardin, a wooden floor with a mat and an old piece of dark-red carpet, an ordinary kitchen stove, a chest of drawers, a large, perfectly simple bed, in short, a real working woman’s interior. She had to do the washing the next day. Just right, very good, I would have found her just as charming in a purple jacket and a black skirt as now in a brown or red-grey frock. And she was no longer young, perhaps the same age as K.V., and she had a child, yes, life had given her a drubbing and her youth was gone. Gone? – there is no such thing as an old woman. Ah, and she was strong and healthy – and yet not rough, not common. Those who value distinction so very highly, can they always tell what is distinguished? Heavens! People sometimes look for it high and low when it’s close by, as I do too now and then.

I’m glad that I did what I did, because I think that nothing in the world should keep me from my work or cause me to lose my good spirits.

When I think of K.V., I still say ‘she and no other’, and I think exactly the same as I did last summer about ‘meanwhile looking for another lass’. But it’s not only recently that I’ve grown fond of those women who are condemned and despised and cursed by clergymen, my love for them is even somewhat older than my love for Kee Vos. Whenever I walked down the street – often all alone and at loose ends, half sick and destitute, with no money in my pocket – I looked at them and envied the people who could go off with her, and I felt as though those poor girls were my sisters, as far as our circumstances and experience of life were concerned. And, you see, that feeling is old and deeply rooted in me. Even as a boy I sometimes looked up with endless sympathy and respect into a half-withered female face on which it was written, as it were: life and reality have given me a drubbing. But my feelings for K.V. are completely new and something entirely different. Without knowing it, she’s in a kind of prison. She’s also poor and can’t do everything she wants, and you see, she has a kind of resignation and I think that the Jesuitisms of clergymen and devout ladies often make more of an impression on her than on me, Jesuitisms that no longer impress me for the very reason that I’ve learned a few tricks. But she adheres to them and couldn’t bear it if the system of resignation and sin and God and whatnot appeared to be a conceit. And I don’t think it occurs to her that perhaps God only actually begins when we say those words with which Multatuli closes his prayer of an unbeliever: ‘O God, there is no God’. Look, I find the clergymen’s God as dead as a doornail. But does that make me an atheist? The clergymen think me one – be that as it may – but look, I love, and how could I feel love if I myself weren’t alive and others weren’t alive? And if we live, there’s something wondrous about it. Call it God or human nature or what you will, but there’s a certain something that I can’t define in a system, even though it’s very much alive and real, and you see, for me it’s God or just as good as God. Look, if I must die in due course in one way or another, fine, what would there be to keep me alive? Wouldn’t it be the thought of love (moral or immoral love, what do I know about it?). And heavens, I love Kee Vos for a thousand reasons, but precisely because I believe in life and in something real I no longer become distracted as I used to when I had thoughts about God and religion that were more or less similar to those Kee Vos now appears to have. I won’t give her up, but that inner crisis she’s perhaps going through will take time, and I have the patience for it, and nothing she says or does makes me angry. But as long as she goes on being attached to the past and clinging to it, I must work and keep my mind clear for painting and drawing and business. So I did what I did, from a need for warmth of life and with an eye to health. I’m also telling you these things so that you don’t get the idea again that I’m in a melancholy or distracted, pensive mood. On the contrary, I’m usually pottering about with and thinking about paint, making watercolours, looking for a studio &c. &c. Old chap, if only I could find a suitable studio.

Well, my letter has grown long, but anyway.

I sometimes wish that the three months between now and going back to M. were already over, but such as they’ll be, they’ll bring some good. Write to me, though, now and then. Are you coming again in the winter?

And listen, renting a studio &c., I’ll do it or I won’t, depending on what Mauve thinks of it. I’m sending him the floor plan as agreed, and perhaps he’ll come and have a look himself if necessary. But Pa has to stay out of it. Pa isn’t the right man to get mixed up in artistic matters. And the less I have to do with Pa in business matters, the better I’ll get along with Pa. But I have to be free and independent in many things, that goes without saying.

I sometimes shudder at the thought of K.V., seeing her dwelling on the past and clinging to old, dead notions. There’s something fatal about it, and oh, she’d be none the worse for changing her mind. I think it quite possible that her reaction will come, there’s so much in her that’s healthy and lively. And so in March I’ll go to The Hague again and – and – again to Amsterdam. But when I left Amsterdam this time, I said to myself, under no circumstances should you become melancholy and let yourself be overwhelmed so that your work suffers, especially now that it’s beginning to progress. Eating strawberries in the spring, yes, that’s part of life, but it’s only a short part of the year and it’s still a long way off.

And you should envy me because of this or that? Oh no, old chap, because what I’m seeking can be found by all, by you perhaps sooner than by me. And oh, I’m so backward and narrow-minded about so many things, if only I knew exactly why and what I should do to improve. But unfortunately we often don’t see the beams in our own eye. Do write to me soon, and you’ll just have to separate the wheat from the chaff in my letters, if sometimes there’s something good in them, something true, so much the better, but of course there’s much in them that’s wrong, more or less, or perhaps exaggerated, without my always being aware of it. I’m truly no scholar and am so extremely ignorant, oh, like many others and even more than others, but I can’t gauge that myself, and I can gauge others even less than I can gauge myself, and am often wide of the mark. But even as we stray we sometimes find the track anyway, and there’s something good in all movement (by the way, I happened to hear Jules Breton say that and have remembered that utterance of his). Tell me, have you ever heard Mauve preach?? I’ve heard him imitate several clergymen – once he gave a sermon on Peter’s barque (the sermon was divided into 3 parts: First, would he have bought it or inherited it? Second, would he have paid for it in instalments or parts? Third, did he perhaps (banish the thought) steal it?) Then he went on to preach on ‘the goodness of the Lord’ and on ‘the Tigris and the Euphrates’ and finally he did an imitation of J.P.S., how he had married A. and Lecomte.

But when I told him that I had once said in a conversation with Pa that I believed that one could say something edifying even in church, even from the pulpit, M. said, Yes. And then he did an imitation of Father Bernhard: God – God – is almighty – he created the sea, he created the earth and the sky and the stars and the sun and the moon, he can do everything – everything – everything – and yet – no, He’s not almighty, there’s one thing He cannot do. What is the one thing that God Almighty cannot do? God Almighty cannot cast away a sinner. Well, adieu, Theo, do write soon, in thought a handshake, believe me

Ever yours,

Vincent

To Theo van Gogh (letter 203)

Schenkweg 138 Thursday.

My dear Theo,

I received your letter and the 100 francs enclosed in good order, and thank you very much for both. What I feared would happen when last I wrote to you has now truly come about, namely that I fell ill and spent three days or so lying in bed with fever and anxiety. Accompanied now and then by headache and toothache. It’s a wretched condition and comes from nervous exhaustion. Mauve came to see me and we agreed again to bear up bravely through it all.

But then I loathe myself so much for not being able to do what I’d like, and at such moments one feels as though one is bound hand and foot, lying in a deep, dark pit, powerless to do anything. Now it’s over, inasmuch as I got up last night and pottered around a bit, putting one thing and another in order, and when this morning the model came of her own accord to have a look, even though I only half expected her, together with Mauve I arranged her in a pose and tried to draw a little, but I can’t yet, and this evening I felt completely weak and miserable. But if I do as little as possible for a couple of days then it will be over for a good long time, and if I’m careful I needn’t be afraid that it will recur for the time being. I’m very sorry that you’re not well either. When I was in Brussels last winter, I had baths as often as I could, 2 or 3 times a week in the bathhouse, and I felt very well and shall start doing it again here. I don’t doubt but that it would also help you a lot if you were to keep it up for a while, because one gets what they call ‘radiation’ here, namely that the pores of the skin stay open and the skin can breathe, whereas otherwise it shrivels up a bit, especially in the winter.

And I tell you frankly that I definitely think you mustn’t be embarrassed about going to a girl now and then, if you know one you can trust and you can feel something for, of which there are many in fact. Because for someone whose life is all hard work and exertion it’s necessary, absolutely necessary, to stay normal and to keep one’s wits about one.

One doesn’t have to overdo that kind of thing and go to excess, but nature has fixed laws and it’s fatal to struggle against them. Anyway, you know everything you need to know about it.

It would be good for you, it would be good for me, if we were married, but what can one do?

I’m sending you a little drawing, but you mustn’t conclude from it that they’re all like that, this is fairly thin and washed quickly, but that doesn’t always work, especially with larger ones, in fact it seldom does.

Yet it will perhaps prove to you that it’s not a hopeless case, that I’m beginning to get the hang of it, rather.

When Mauve was last here he asked me if I needed any money. I could put on a brave face towards him and that’s going better, but you see that in an emergency he would also do something.

And so, although there will still be worries, I do have hope that we’ll muddle through. Especially if Mr Tersteeg would be kind enough, if it’s inconvenient for you, to give me some credit if it should prove absolutely necessary.

You speak of fine promises. It’s more or less the same with me. Mauve says it will go well, but that doesn’t alter the fact that the watercolours I’m making still aren’t exactly saleable. Well, I also have hope and I’ll work myself to the bone, but one is sometimes driven to desperation when one wants to work something up a bit more and it turns out thick. It’s enough to drive one to distraction, for it’s no small difficulty. And experiments and trials with watercolours are rather costly. Paper, paint, brushes and the model and time and all the rest.

Still, I believe that the least expensive way is to persevere without losing any time.

For one must get through this miserable period. Now I must learn not to do some things which I more or less taught myself, and to look at things in a completely different way. A great effort must be made before one can look at the proportion of things with a steady eye.

It’s not exactly easy for me to get along with Mauve all the time, any more than is the reverse, because I think we’re a match for each other as regards nervous energy, and it’s a downright effort for him to give me directions, and no less for me to understand them and to attempt to put them into practice.

But I think we’re beginning to understand each other quite well, and it’s already beginning to be a deeper feeling than mere superficial sympathy. He has his hands full with his large painting that was once intended for the Salon, it will be splendid. And he’s also working on a winter scene. And some lovely drawings.

I believe he puts a little bit of his life into each painting and each drawing. Sometimes he’s dog-tired, and he said recently, ‘I’m not getting any stronger’, and anyone seeing him just then wouldn’t easily forget the expression on his face.

This is what Mauve says to console me when my drawings turn out heavy, thick, muddy, black, dead: If you were already working thinly now, it would only be being stylish and later your work would probably become thick. Now, though, you’re struggling and it becomes heavy, but later it will become quick and thin. If indeed it turns out like that, I have nothing against it. And you see it now from this small one, which took a quarter of an hour to make from beginning to end, but – after I’d made a larger one that turned out too heavy. And it was precisely because I’d struggled with that other one that, when the model happened to be standing like this for a moment, I was later able to sketch this one in an instant on a little piece of paper that was left over from a sheet of Whatman.

This model is a pretty girl, I believe she’s mainly Artz’s model, but she charges a daalder a day and that’s really too expensive for now. So I simply toil on with my old crone.

The success or failure of a drawing also has a lot to do with one’s mood and condition, I believe. And that’s why I do what I can to stay clear-headed and cheerful. But sometimes, like now, some malaise or other takes hold of me, and then it doesn’t work at all.

But then, too, the message is to keep on working – because Mauve, for instance, and Israëls and so many others who are examples know how to benefit from every mood.

Anyway, I have some hope that as soon as I’m completely better things will go well, a little better than now. If I have to rest for a while I’ll do it, but it will probably be over soon.

All things considered, though, I’m not like I was a year or so ago, when I never had to stay in bed for a day, and now there’s something thwarting me at every turn, even if it isn’t so bad.

In short, my youth is past, not my love of life or my vitality, but I mean the time when one doesn’t feel that one lives, and lives without effort. Actually I say all the better, there are now better things, after all, than there were then. Bear up, old chap – it really is rather petty and mean of Messrs G&Cie that they refused you when you wanted to have some money. You certainly didn’t deserve that, that they were so cold-hearted towards you, because you do a lot of their dirty work and don’t spare yourself. So you have a right to be treated with some respect.

Accept a handshake in thought, I hope that I’ll soon have something better to tell you than I did today and recently, but you mustn’t hold it against me, I’m very weak. Adieu.

Ever yours,

Vincent

To Theo van Gogh (letter 211)

My dear Theo,

You will have received my letters, I’m answering yours, received this afternoon. In accordance with your request, I immediately sent Tersteeg 10 guilders, lent to me this week by His Hon. I wrote to you about C.M.’s order, this is what happened. C.M. appeared to have spoken to Tersteeg before he came to see me, at any rate began talking about things like ‘earning your bread’. My answer suddenly came to me, quickly and, I believe, correctly. Here’s what I said: earn my bread, what do you mean by that? — to earn one’s bread or to deserve one’s bread — not to deserve one’s bread, that is to say, to be unworthy of one’s bread, that’s what’s a crime, every honest man being worthy of his crust — but as for not earning it at all, while at the same time deserving it, oh, that! is a misfortune and A great misfortune. So, if you’re saying to me here and now: you’re unworthy of your bread, I understand that you’re insulting me, but if you’re making the moderately fair comment to me that I don’t always earn it because sometimes I’m short of it, so be it, but what’s the use of making that comment to me? It’s scarcely useful to me if it ends there. I recently tried, I continued, to explain this to Tersteeg, but either he’s hard of hearing in that ear or my explanation was a little confused because of the pain his words caused me.

C.M. then kept quiet about earning one’s bread.

The storm threatened again because I happened to mention the name Degroux in connection with expression. C.M. suddenly asked, But surely you know there was something untoward about Degroux’s private life?

You understand that there C.M. touched a tender spot and ventured on to thin ice. I really can’t let that be said about good père Degroux. So I replied, it has always seemed to me that when an artist shows his work to people he has the right to keep to himself the inner struggle of his own private life (which is directly and inextricably connected with the singular difficulties involved in producing a work of art) – unless he unburdens himself to a very intimate friend. It is, I say, indelicate for a critic to dig up something blameworthy from the private life of someone whose work is above criticism. Degroux is a master like Millet, like Gavarni.

C.M. had certainly not viewed Gavarni, at least, as a master.

(To anyone but C.M. I could have expressed myself more succinctly by saying: an artist’s work and his private life are like a woman in childbed and her child. You may look at her child, but you may not lift up her chemise to see if there are any bloodstains on it, that would be indelicate on the occasion of a maternity visit.)

I was already beginning to fear that C.M. would hold it against me – but fortunately things took a turn for the better. As a diversion I got out my portfolio with smaller studies and sketches. At first he said nothing – until we came to a little drawing that I’d sketched once with Breitner, parading around at midnight – namely Paddemoes (that Jewish quarter near the Nieuwe Kerk), seen from Turfmarkt. I’d set to work on it again the next morning with the pen.

Jules Bakhuyzen had also looked at the thing and recognized the spot immediately.

Could you make more of those townscapes for me? said C.M. Certainly, because I amuse myself with them sometimes when I’ve worked myself to the bone with the model – here’s Vleersteeg – the Geest district – Vischmarkt. Make 12 of those for me. Certainly, I said, but that means we’re doing a bit of business, so let’s talk straightaway about the price. My price for a drawing of that size, whether with pencil or pen, I’ve fixed for myself at a rijksdaalder – does that seem unreasonable to you?

No – he simply says – if they turn out well I’ll ask for another 12 of Amsterdam, provided you let me fix the price, then you’ll earn a bit more.

Well, it seems to me that that’s not a bad way to end a visit I had rather dreaded. Because I actually made an agreement with you, Theo, simply to tell you things like this in my own way, as it flows from my pen, I’m describing these little scenes to you just as they happen. Especially because in this way, even though you’re absent, you get a glimpse of my studio anyway.

I’m longing for you to come, because then I can talk to you more seriously about things concerning home, for instance.

C.M.’s order is a bright spot! I’ll try to do those drawings carefully and put some spirit into them. And in any case you’ll see them, and I believe, old chap, that there’s more of such business. Buyers for 5-franc drawings can be found. With a bit of practice, I’ll make one every day and voilà, if they sell well, a crust of bread and a guilder a day for the model. The lovely season with long days is approaching, I’ll make the ‘soup ticket’, i.e. the bread and model drawing, either in the morning or the evening, and during the day I’ll study seriously from the model. C.M. is one buyer I found myself. Who knows whether you won’t succeed in turning up a second, and perhaps Tersteeg, when he’s recovered from his reproachful fury, a third, and then things can move along.

Tomorrow morning I’ll go and look for a subject for one of those for C.M.

I was at Pulchri this evening – Tableaux vivants and a kind of farce by Tony Offermans. I skipped the farce, because I can’t stand caricatures or the fug of an assembly hall, but I wanted to see the tableaux vivants, especially because one of them was done after an etching I gave Mauve as a present, Nicolaas Maes, the stable at Bethlehem. (The other was Rembrandt, Isaac blessing Jacob, with a superb Rebecca who watches to see if her ruse will succeed.) The Nicolaas Maes was very good in chiaroscuro and even colour – but in my opinion not worth tuppence as far as expression goes. The expression was definitely wrong. I saw it once in real life, not the birth of the baby Jesus, mind you, but the birth of a calf. And I still know exactly what its expression was like. There was a girl there, at night in that stable – in the Borinage – a brown peasant face with a white night-cap among other things, she had tears in her eyes of compassion for the poor cow when the animal went into labour and was having great difficulty. It was pure, holy, wonderfully beautiful like a Correggio, like a Millet, like an Israëls. Oh Theo – why don’t you let it all go hang and become a painter? Old chap – you could do it if you wanted to. I sometimes suspect you of keeping a great landscapist hidden inside you. It seems to me you’d be extremely good at drawing birch trunks and sketching the furrows of a field or stubble field, and painting snow and sky &c. Just between you and me. I shake your hand.

Ever yours,

Vincent

Here’s a list of Dutch paintings intended for the Salon.