The parsonage in Nuenen. The studio was located at the lower right.

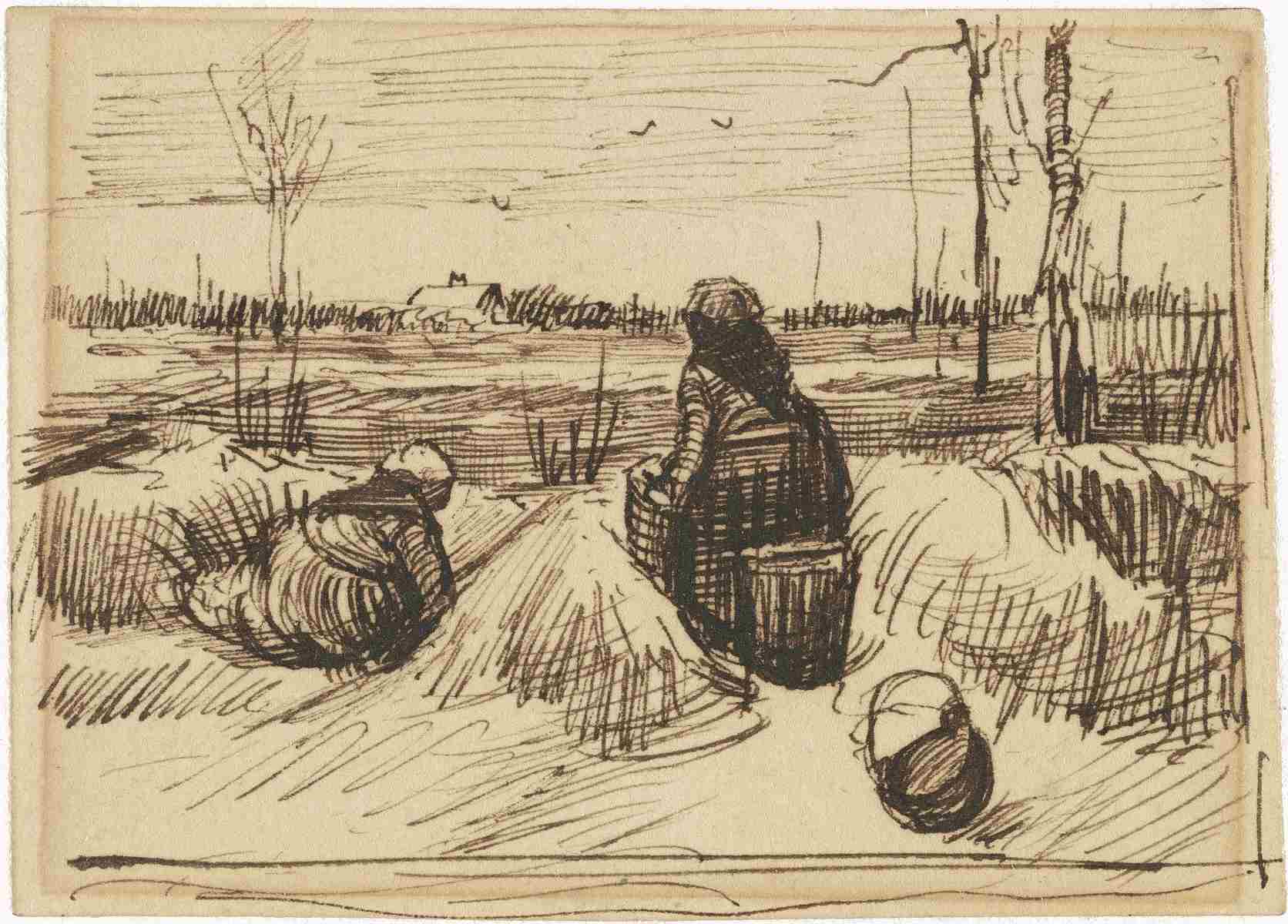

In September 1883 Vincent set off for rural Drenthe, taking with him a minimum of artists’ materials. The choice of this northern province must have been prompted by what his fellow artists Mauve, Van Rappard and Breitner had told him about its unspoiled nature. He stayed for a while in Hoogeveen before travelling in early October via passenger barge to Nieuw-Amsterdam/Veenoord, where he found lodgings in a boarding house. From this base he explored the surrounding area for suitable subjects, which resulted in a series of evocative landscapes with dilapidated huts, women working in the peat bogs, a man burning weeds at dusk and workers by a peat barge. He described an excursion to Zweeloo in lyrical terms (402), and wrote to Theo that the beauty of the countryside ‘absorbs and fulfils me so utterly’ (405). Vincent had an ulterior motive in praising the landscape so highly to Theo: his brother’s relations with his superiors at Goupil had become difficult and Vincent tried to persuade him to leave the art trade and city life behind, and become a painter. Theo, understandably, did not take his brother’s suggestion seriously.

However impressed he was by the landscape, loneliness bore down heavily on Vincent during these cold and rainy months. It was difficult to work outdoors, there were no models to be had, and he was running out of painting materials. The evenings were long, and this is reflected in the length of his letters. Theo’s mention of his uncertain financial situation prompted Vincent to leave Drenthe. He set off for Hoogeveen on foot – a walk that took him more than six hours – where he caught a train to his parents’ home in Nuenen, near Eindhoven.

On 5 December 1883 Van Gogh first set foot in the austere but respectably furnished parsonage where his parents had been living for over a year. He was to remain in the village for two years. His homecoming and welcome were, to his mind, anything but cordial: ‘There’s a similar reluctance about taking me into the house as there would be about having a large, shaggy dog in the house’ (413). The mangle room behind the house was converted into a studio for him, but he found its location and arrangement far from ideal, and there was not enough room for models to sit for him.

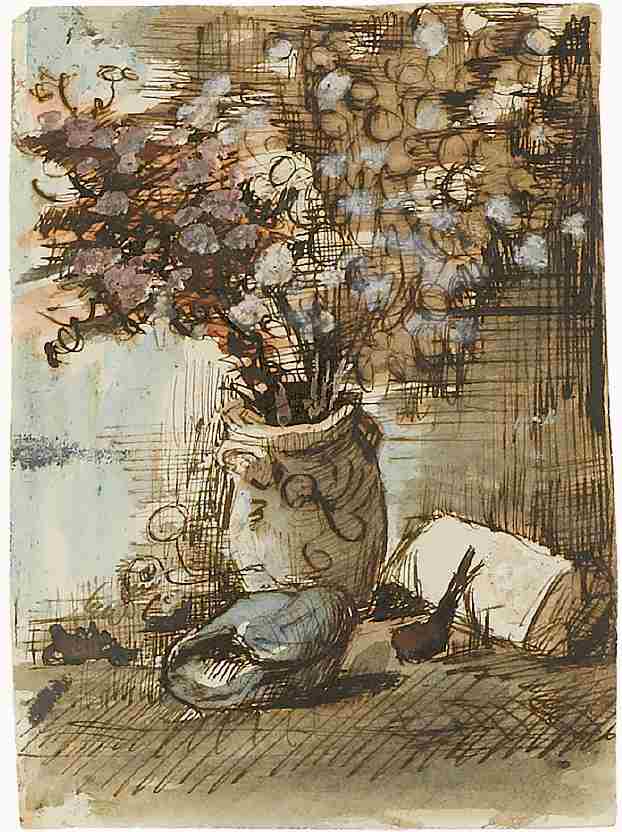

Inspired by Jean-François Millet, Van Gogh’s new mission was to paint peasants and labourers at work. His first subjects were weavers: between December 1883 and July 1884 he made a series of drawings and paintings of weavers at their looms. In the months when it was difficult to work out of doors, he painted whole series of still lifes. From May 1884 he rented from the Catholic sacristan a reasonably large studio: two rooms en suite, which gave him enough room to work comfortably. He was still in frequent contact with Van Rappard: they painted together and discussed technique, and Van Rappard came to respect his friend’s talent for drawing. The fact that Van Gogh frequently gave lessons to amateur painters in the area testifies to his growing self-confidence.

In his first years as an artist, Van Gogh had primarily occupied himself with drawing, and his chief considerations were of a technical nature: questions of composition, the handling of line, and the effects produced by the materials. Colour played a secondary role. This changed in Nuenen, when he decided to devote himself completely to painting and immersed himself in colour theory. His letters from this period include quotations and paraphrases about art, artists and theories on colour taken from books by Bracquemond, Silvestre, De Goncourt, Sensier, Gigoux, Blanc and Bürger, which he read intently.

In early 1884 had Vincent decided that, in exchange for the money Theo sent, his brother should do as he saw fit with his artworks, ideally finding buyers for them. Evidently Van Gogh struggled with his dependence on Theo. The tone of Vincent’s letters is more defensive in the Dutch period, or he tries to vindicate the choices he has made. As yet he had no saleable work to justify Theo’s support, and it is a fact that Theo saw little chance of selling any of it before Vincent left the Netherlands at the end of 1885. Their relations were often strained in this period; Theo found that Vincent was making their parents’ lives difficult, and Vincent was often disappointed in his brother for his supposed lack of understanding and moral support.

In the summer of 1884, Van Gogh again caused consternation by beginning a relationship with a neighbour, Margot Begemann, who was mentally unstable. Both of their families did everything they could to put an end to the affair, the low point of which was Margot’s attempted suicide by swallowing strychnine. Van Gogh was alone with her when the poison took effect, and got her to a doctor. While she was convalescing in Utrecht, he remained loyal to her and even contemplated marriage, but eventually abandoned the idea. It was at times such as these that he felt how deep the differences were between himself and those around him.

On 26 March 1885 Van Gogh’s father died of a heart attack. Shortly afterwards, Vincent’s sister Anna asked Vincent to leave the parsonage, believing that his moods were putting further strain on their grieving mother, and he went to live in his studio.

Van Gogh had a growing conviction in his abilities as an artist, although he still considered many of his works as experiments, referring to them as ‘studies’. He painted dozens of peasants’ heads in preparation for an important figure composition, resulting in May 1885 in The Potato Eaters, which in his eyes was the first fully fledged painting he had ever made. The frankly negative reactions to this great test of his workmanship made Van Gogh realize that in many respects he was in a rut. His work was apparently unsellable, his objectionable behaviour made models unwilling to pose for him, and he missed the necessary contact with the art world. Theo tried to make Vincent understand that his approach was not in step with the ‘modern art’ in Paris. Feeling the need for new stimuli and further study, Van Gogh set out in November 1885 to study at the art academy in Antwerp. He also hoped that the city would offer him a larger choice of subject matter and opportunities to sell his work.

The parsonage in Nuenen. The studio was located at the lower right.

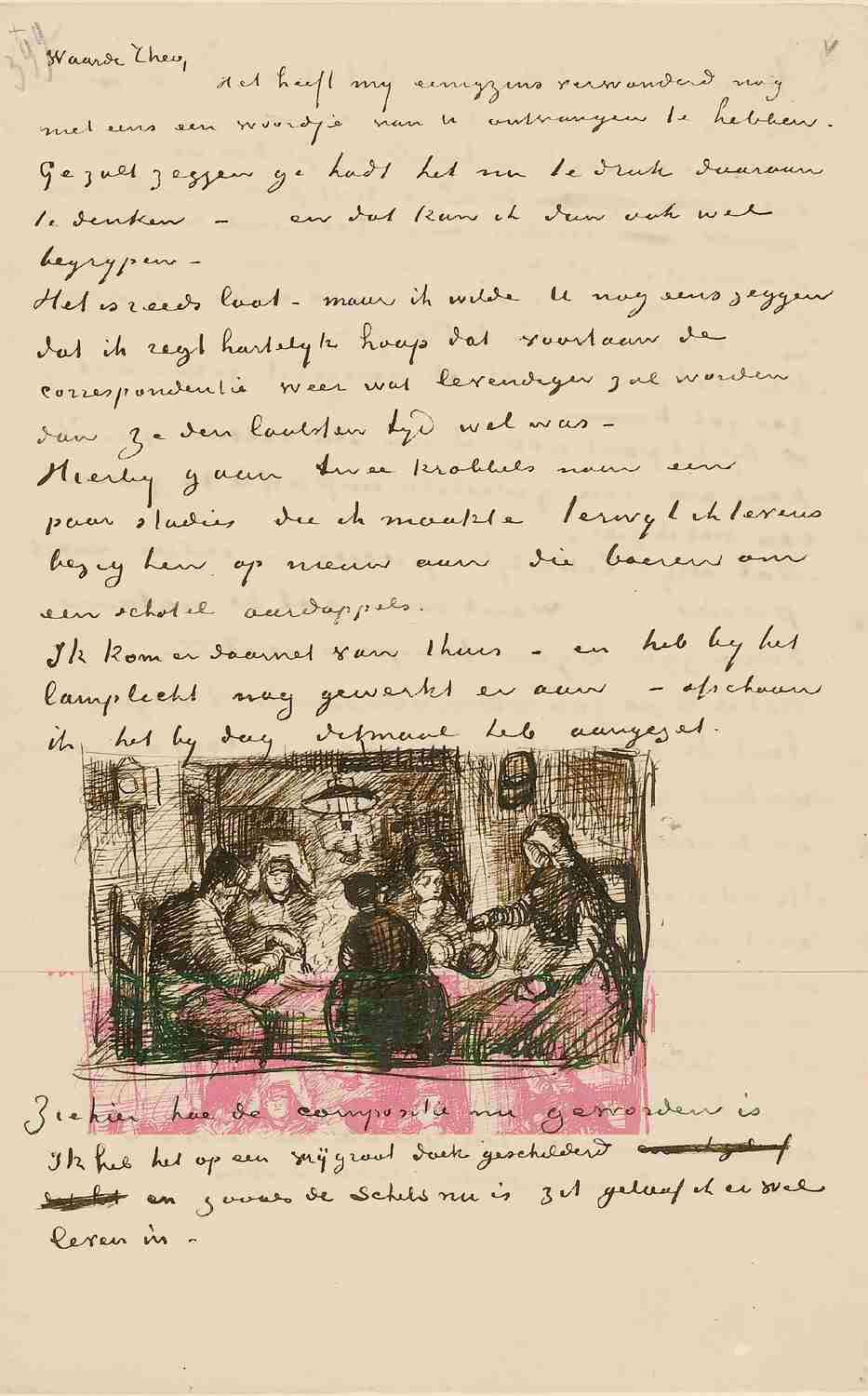

To Theo van Gogh (letter 386)

My dear Theo,

Now that I’ve been here for a few days and have walked around a good deal in different directions, I can tell you more about the region I’ve fetched up in.

I enclose a scratch after my first painted study from this part of the world, a hut on the heath. A hut made of nothing but sods of turf and sticks. I’ve also seen inside about 6 of this type, and more studies of them will follow.

I can’t more accurately describe the way the exterior looks in the twilight or just after sunset than by reminding you of a particular painting by Jules Dupré which I think belongs to Mesdag, with two huts in it on which the mossy roofs stand out surprisingly deep in tone against a hazy, dusty evening sky.

That is here.

Well, it’s very beautiful inside these huts, dark as a cave. Drawings by certain English artists who have worked on the moors in Ireland most realistically convey what I observe. A. Neuhuys does the same with somewhat more poetry than strikes one at first, but he makes nothing that isn’t also fundamentally true.

I saw superb figures out in the country — striking in their expression of soberness. A woman’s breast, for example, has that heaving motion that is the exact opposite of voluptuousness, and sometimes, if the creature is old or sickly, arouses compassion or else respect. And the melancholy which things in general have is of a healthy kind, as in Millet’s drawings.

Happily, the men here wear breeches; it shows off the shape of the leg, makes the movements more expressive.

To mention one of the many things that gave me something new to see and to feel during my explorations, I’ll tell you how here one sees, for example, barges pulled by men, women, children, white or black horses, loaded with peat, in the middle of the heath, just like the ones in Holland, on the Trekweg at Rijswijk, for instance.

The heathland is rich. I saw sheepfolds and shepherds that were more attractive than those in Brabant.

The ovens are more or less like the ones in T. Rousseau’s Communal oven; stand in the gardens under old apple trees or among the celery and cabbages.

Beehives, too, in many places.

One can see that many of the people have something wrong with them — it isn’t exactly healthy here, I think — perhaps because of unclean drinking water. I’ve seen some girls of, I would say, 17 or younger who still had something very beautiful and youthful, in their features too, but generally it fades very early. Yet this doesn’t detract from the fine, noble bearing of the figure that some of them have, who prove to be very withered when seen close to.

There are 4 or 5 canals in the village, to Meppel, to Dedemsvaart, to Coevorden, to Hollandscheveld.

If you follow them, you see here and there a curious old mill, farmhouse, shipyard or lock. And always the peat barges coming and going.

To give you an example of the authentic character of this region: while I was sitting painting that hut, two sheep and a goat came up and started grazing on the roof of the house. The goat climbed onto the ridge and looked down the chimney.

The woman, who heard something on the roof, shot outside and threw her broom at the said goat, which leapt down like a chamois.

The two hamlets on the heath where I’ve been and where this incident took place are called Stuifzand and Zwartschaap. I’ve also been in various other places, and now you can imagine how unchanged it still is here, since Hoogeveen is a town after all, and yet nearby there are shepherds, those ovens, those turf huts &c.

I sometimes think with great melancholy about the woman and the children, if only they were looked after — oh, it’s the woman’s own fault, one could say, and it would be true, but I fear that her misfortune will be greater than her guilt. I knew from the outset that her character is a ruined character, but I had hopes of her finding her feet and now, precisely when I don’t see her any more and think about the things I saw in her, I increasingly come to realize that she was already too far gone to find her feet.

And that just makes my feelings of pity even greater, and it’s a melancholy feeling because it isn’t in my power to do anything about it. Theo, when I see some poor woman on the heath with a child in her arms or at her breast my eyes become moist. I see her in them; her weakness and slovenliness, too, only serve to intensify the likeness. I know that she isn’t good, that I have every right to do what I’m doing, that to stay with her there WASN’T POSSIBLE, that bringing her with me really wasn’t possible either, that what I did was even sensible, wise, what you will, but that doesn’t alter the fact that it goes right through me when I see some poor little creature, feverish and miserable, and that then my heart melts. How much sadness there is in life. Well, one may not become melancholy, one must look elsewhere, and to work is the right thing, only there are moments when one only finds peace in the realization: misfortune won’t spare me either. Adieu, write soon, and believe me

Ever yours,

Vincent

To Theo van Gogh (letter 394)

Dear brother,

I just received your letter. I read and re-read it with interest, and something that I’ve already thought about sometimes, without knowing what to do about it, is becoming clear to me. It’s that you and I have in common a time of quietly drawing impossible windmills &c., where the drawings are in a singular rapport with the storm of thoughts and aspirations — in vain, because no one who can shed light is concerned about them (only a painter would then be able to help one along the right path, and their thoughts are elsewhere). This is a great inner struggle, and it ends in discouragement or in throwing those thoughts overboard as impractical, and precisely when one is 20 or so, one is passionate to do that. Whatever the truth of the matter that I said something then that unwittingly contributed to throwing those things overboard; at that moment my thoughts were perhaps the same as yours, that’s to say that I saw it as something impossible, but as regards that desperate struggle without seeing any light, I know it too, how awful it is. With all one’s energy one can do nothing and thinks oneself mad, and I don’t know what else. When I was in London, how often I would stand on the Thames Embankment and draw as I made my way home from Southampton Street in the evening, and it looked terrible. If only there had been someone then who had told me what perspective was, how much misery I would have been spared, how much further along I would be now. Well, fait accompli is fait accompli. It didn’t happen then — I did talk to Thijs Maris occasionally (I didn’t dare speak to Boughton, because I felt such great respect in his presence) but I didn’t find it there either, that helping me with the first things, with the ABC.

Let me now repeat that I believe in you as an artist, and that you can still become one, indeed that you should very soon think calmly about whether you are one or not, whether you would be able to produce something or not if you learned to spell the aforementioned ABC, and then also spent some time walking through the wheatfield and the heath, in order to renew once more what you yourself say, ‘I used to be part of that nature, now I don’t feel that any more’. Let me tell you, brother, that I myself have felt so deeply, deeply that which you say there. That I’ve had a time of nervous, barren stress when I had days when I couldn’t find the most beautiful countryside beautiful, precisely because I didn’t feel myself part of it. That’s what pavements and the office — and care — and nerves — do.

Don’t take it amiss if I say now that your soul is sick at this moment — it really is — it isn’t good that you aren’t part of nature — and I think that No. 1 now is for you to make that normal again. I think it’s very good that you yourself feel the difference between your state of mind now and in other years. And don’t doubt that you will agree with me that you must work on it to put it right.

I now have to look back into my own past to see what the matter was, spending years in that stony, barren state of mind and trying to emerge from it, and yet it got worse and worse instead of better.

Not only did I feel indifferent instead of responsive to nature but also, which was much worse, I felt exactly the same about people.

People said that I was going mad; I myself felt that I wasn’t, if only because I felt my own malady very deep inside myself and tried to get over it again. I made all sorts of forlorn attempts that led to nothing, so be it, but because of that idée fixe of getting back to a normal position I never confused my own desperate doings, scrambling and squirmings with I myself. At least I always felt ‘let me just do something, be somewhere, it must get better, I’ll get over it, let me have the patience to recover’.

I don’t believe that someone like Boks, for instance, who really turned out to be mad, thought like that — so I say again, I’ve thought about it a lot since, about my years of all sorts of scrambling, and I don’t see that, given my circumstances, I could be other than I have been.

Here is the ground that sank beneath my feet — here is the ground which, if it sinks, must make a person miserable, whoever he may be. I was with G&Cie for 6 years — I had put down roots in G&Cie and I thought that, although I left, I could look back on 6 years of good work, and that if I presented myself somewhere I could refer to my past with equanimity.

But by no means; things are done so hurriedly that little consideration is given, little is questioned or reasoned. People act on the most random, most superficial impressions. And once one is out of G&Cie no one knows who G&Cie is. It’s a name like X&Co., without meaning — and so one is simply ‘a person without a situation’. All at once — suddenly — fatally — everywhere — there you have it. Of course, precisely because one has a certain respectability one doesn’t say I’m so-and-so, I’m this or that. One presents oneself for a new situation serious in all respects, without saying much, with a view to putting one’s hand to the plough. Very well, but then, that ‘person without a situation’, the man from anywhere, gradually becomes suspect.

Suppose that your new employer is a man whose affairs are very mysterious, and suppose that he has just one goal, ‘money’. With all your energy, can you really immediately, at once, help him a very great deal in that? Perhaps not, eh? And yet he wants money, money come what may; you want to know something more about the business, and what you see or hear is pretty disgusting.

And soon it’s: ‘someone without a situation’, I don’t need you any more. See, now that’s what you increasingly become: someone without a situation. Go to England, go to America, it doesn’t help at all, you’re an uprooted tree everywhere. G&Cie, where your roots are from an early age — G&Cie, although indirectly they cause you this misery because in your youth you regarded them as the finest, the best, the biggest in the world — G&Cie, were you to return to them — I didn’t do that then — I couldn’t — my heart was too full, much too full — G&Cie, they’d give you the cold shoulder, say it was no longer their concern or something. With all this one has been uprooted, and the world turns it around and says that you’ve uprooted yourself. Fact — your place no longer acknowledges you. I felt too melancholy to do anything about it — and I don’t remember ever having been in the mood to talk to someone about it as I’m talking to you now. Because, and actually to my surprise, for I thought that even if they did it to me they would, however, certainly not have dared to do it to you, I read in your letter the words ‘when I spoke to them this week the gentlemen made it almost impossible for me’. Old chap, you know how it is with me, but if you’re miserable about one thing and another, do not feel you are ALONE. It’s too much to bear alone, and to some extent I can sympathize with you the way it is. Now, stand your ground and don’t let your pain throw you off balance — if the gentlemen behave like this, stand on your dignity and don’t accept your dismissal except on terms that guarantee you’ll get a new situation. They aren’t worth your losing your temper, don’t do that, even if they provoke you. I lost my temper and walked straight out. Now in my position it was different again from yours; I was one of the least, you are one of the first, but what I say about being uprooted, I’m afraid that you would feel the same if you were out of it, so look at that, too, cold-bloodedly, stand up to them and don’t let them push you out without being a little prepared for that difficult situation of beginning again. And know this — given an uprooting, given not making headway again, don’t despair.

Then, in the worst case, do NOT go to America, because it’s exactly the same there as in Paris. No, beware of reaching that point where one says: I’ll make myself scarce; I had that myself, I hope that you won’t have it. If you had it, I say again, beware of it, resist it with great coolness, say to yourself, this point proves to me that I’m running into a brick wall. This is a wall for bulls to run into; I am a bull too, but an intelligent one, I am a bull about becoming an artist. Anyway, get out before you smash your head to pieces, that’s all. I’m not saying that that’s what will happen; I hope that there will be no question whatever of running into a wall. But suppose after all that there was a whirlpool with accompanying sharp-edged rocky promontories, well, I would just think that you might avoid it, wouldn’t you? Perhaps you’ll admit that those rocks might be there, since you yourself pulled me out of that whirlpool when I had no more hope of getting out of it and was powerless to fight against it any more.

I mean, give those waters a very wide berth. They’re beginning to drag you down in that one thing — I say no more nor less than I’m sure of — that you aren’t part of nature. Do you think it strange of me that I dare to say as much as this: now, at the very beginning, change course now and no later than now in so far as you work at restoring the bond between yourself and nature? The more you remain in the frame of mind of not being part of nature, the more you play into the hands of your eternal enemy (and mine too), Nerves. I have more experience than you of the sort of tricks they could play on you. You’re now beginning to enter waters that are throwing you off balance, inasmuch as the rapport with nature seems to be broken. Take that very coolly as a sign of aberration; say, oh no, not that way if you please. Seek a new passion, an interest in something; think, for example, after all perspective must fundamentally be the simplest of all things and chiaroscuro a simple, not a complicated matter. It must be something that speaks for itself, otherwise I don’t much care for it. Try to get back to nature in this way.

Will you now, old chap, simply take it from me when I say that as I write to you I’ve got something back of what I had years ago. That I’m again taking pleasure in windmills, for example, that particularly here in Drenthe I feel much as I did then, at the time when I first began to see the beauty in art. You’d be prepared to call that a normal mood, wouldn’t you? — finding the outdoor things beautiful, being calm enough to draw them, to paint them. And suppose you were to come up against a brick wall somewhere, wouldn’t you find someone in my present mood composed enough to want to take a little walk with him, precisely in order to have a distraction from thoughts if, through nervousness, these thoughts start to acquire a certain despairing element? You are yourself and not fundamentally changed, but your nerves are beginning to be unstrung by strain. Now, look after your nerves, and don’t take them lightly, because they cause quick-tempered manoeuvres — well, you know a thing or two about that yourself.

Make no mistake, Theo, at this moment Pa, Ma, Wil, Marie, and I above all, are supported by you; it seems to you that you have to go on for our sakes, and believe me I fully understand that, or at least can understand it to a very great extent. Just think about this for a moment. What is your goal and Pa’s, Ma’s, Wil’s, Marie’s and mine? What do we all want? We want, acting decently, to keep our heads above water, we all want to arrive at a clear position, not a false position, don’t we? This is what we all want, unanimously and sincerely, however much we differ or don’t differ among ourselves. What are we all prepared to do against fate? All, all of us without exception to work quietly, calmness. Am I wrong in regarding the general situation in this way? Very well, what are we facing now? We’re confronting a calamity which, touching you, touches us all. Fine. A storm is brewing. We see it brewing. That lightning might well strike us. Fine. What do we do now? Do we reach our wit’s end? I don’t think that we’re inclined that way — even if certain nerves that we all have in our bodies, even if certain fibres of the heart, finer than nerves, are shocked or experience pain.

We are today what we were yesterday, even if the lightning strikes or even, perhaps, should it thunder. Are we or are we not the sort who can look at things calmly? That, simply, is the question, and I see no reason why we should not be so. What I also see is the following — that our position towards one another is also straight at this moment. That for the purposes of keeping straight it’s desirable to have a closer connection, and in my view there are a few things in ourselves that we’ll have to work out between us.

In the first place, I would be very pleased if your relationship with Marie were to be put on a firmer footing; in other words a formal engagement if possible.

Secondly, I would consider it desirable that we all understood that circumstances urgently require that Brabant no longer be closed to me. I myself think it better that I do not go there unless there’s no other choice, but in the event of an emergency the rent that I’m obliged to pay could be saved, because Pa has a house there rent-free.

I’m at a point where there will probably be some income from my work soon. And if we could now reduce expenditure to a minimum, even below what it is at present, perhaps I could earn instead of consume, become positive instead of negative.

If it’s a question of our having to earn, I can see a chance in this way — if there’s patience at home, a realization of the necessities, if above all, when it comes to models for me, even the family cooperates. As to the question of models, they’d definitely have to do what I wanted, have to trust that I had my reasons for it. If I were to say to Ma or to Wil or Lies, pose for me, it would have to happen.

I wouldn’t make any unreasonable demands, of course. You know how it came about that I left; the fundamental cause was misunderstanding one another, actually in all things. So can we live together? Yes, for a time, if we have to and people on both sides understand that everything has to be subordinated to what the force majeure of circumstances dictates. I had hoped that that was understood at the time, and I didn’t take the initiative to leave — when I was told to go away, though, I went.

Anyway, I broach this because I see that perhaps things will come to pass such that you must have your hands free, and if it might help for me to live at home for a while, I think that Pa and I would both have to reconcile ourselves to that immediately. Although if it isn’t necessary — so much the better. But I’m not saying that I absolutely must be in Drenthe; where isn’t the most important thing.

So be aware of this, that in that respect I would of course do whatever you thought advisable.

Well, I’ll write to Pa today, without more ado, simply this: if Theo were to think it advisable that my expenses should be reduced to a minimum and I should live at home for a while, I hope that both you and I will have the sense not to put a spoke in the wheel through mutual discord, but keeping silent about everything that has passed will reconcile ourselves to what circumstances bring. Nothing more about you or about business nor, should I have to live at home, would I talk about you other than in general terms. And for the time being I would certainly not mention Marie.

Theo, if you had said perhaps a year ago that you would certainly not become a painter, would certainly stay in your present profession, I would have had to accede; now I don’t accede so readily, I still see that repeated occurrence in the history of art of the phenomenon of two brothers who are painters. I know that the future is unpredictable, at least I tell you that I don’t know how things will turn out. However, it’s definitely the case that I believe in you as an artist, and this is actually reinforced by some of the things in your last letter.

Mind now, I advise you of one thing that’s urgently necessary — beware of your nerves — use all means to keep your constitution calm. Consult a doctor daily if you possibly can, not so much because a doctor can do anything about it, as much as would be needed, but because the very fact of going to a doctor to talk about it &c. will show you, this is nerves, that is me.

It’s a question here of self-knowledge, of serenity, despite all the tricks that the nerves must play. I consider the whole idea that it could come to your making yourself scarce to be the effect of nerves. You would do wisely and well to regard it in this way yourself. I hope that you will not bring off a coup, I hope that you will not make a financial invention — I hope that you will become a painter. If, through cool aplomb, you can let the crisis now deliberately being created by the gentlemen run off you like water off a duck’s back, can say to them ‘I am certainly not leaving in this way, certainly not now, never like this’ — if you say to them, I have plans but they aren’t even of a commercial nature, and as soon as they can be put into effect I’ll retire in all tranquillity; until that time, as long as you can’t find fault with what I do, leave things as they are, but know that you’re very much mistaken in me if you think that I would leave because you make things impossible for me, or would part from you in any unreasonable way. If you want to be rid of me, very well, I also want to be rid of you, but amicably and in good order, and it goes without saying that I must keep going. Anyhow, try to make them understand that you’re dead cool and calm and will remain so, however that you have absolutely no desire whatsoever to stay — but that you won’t leave until you see a favourable moment. This seems to me to be the way to counter what they’re now trying to do, to make it impossible for you to stay. Perhaps they suspect that you’ve already established relations elsewhere, and in such a case making it impossible for someone to stay can sometimes be very nasty. If they turn nasty now, there’s nothing for it, cut it short — perhaps the best thing might be to explain calmly that you would retire on certain conditions.

In the meantime, let me know if I should go home for a while so that you have your hands free. And again, Pa, Ma, Wil, Marie, I, in a word all of us, think much more of you yourself than of your money. Making yourself scarce is nothing but sheer nerves.

But — restore — try to restore, even if it doesn’t happen all at once — the rapport between you and nature and people. And if the only way to do this is to become a painter, well then become one, even if you see ever so many objections and impossibilities.

Now listen — write to me very soon — be sure to do that. With a handshake.

Ever yours,

Vincent.

To Theo van Gogh (letter 402)

Dear brother,

Just wanted to tell you about a trip to Zweeloo, the village where Liebermann stayed for a long time and made studies for his painting of the washerwomen at the last Salon.

Where Ter Meulen and Jules Bakhuyzen also spent some time.

Imagine a trip across the heath at 3 o’clock in the morning in an open cart (I went with the man where I lodge, who had to go to the market in Assen). Along a road, or ‘diek’ as they say here, which they’d put mud on to raise it instead of sand. It was much nicer even than the barge. When it was only just starting to get a little lighter and the cocks were crowing everywhere by the huts scattered over the heath, the few cottages we passed — surrounded by slender poplars whose yellow leaves one could hear falling — an old squat tower in a little churchyard with earth bank and beech hedge, the flat landscapes of heath or wheatfields, everything, everything became just exactly like the most beautiful Corots. A silence, a mystery, a peace as only he has painted.

It was still very dark, though, when we got to Zweeloo at 6 o’clock in the morning — I saw the real Corots even earlier in the morning. The ride into the village was really so beautiful. Huge mossy roofs on houses, barns, sheepfolds, sheds. The dwellings here are very wide, among oak trees of a superb bronze. Tones of golden green in the moss, of reddish or bluish or yellowish dark lilac greys in the soil, tones of inexpressible purity in the green of the little wheatfields. Tones of black in the wet trunks, standing out against golden showers of whirling, swirling autumn leaves, which still hang in loose tufts, as if they were blown there, loosely and with the sky shining through them, on poplars, birches, limes, apple trees. The sky unbroken, clear, illuminating, not white but a lilac that cannot be deciphered, white in which one sees swirling red, blue, yellow, which reflects everything and one feels above one everywhere, which is vaporous and unites with the thin mist below. Brings everything together in a spectrum of delicate greys.

I didn’t find a single painter in Zweeloo, though, and the people said they never come there in the winter. It’s precisely in the winter that I hope to be there. Since there were no painters, I decided to walk back and do some drawing on the way instead of waiting for my landlord’s return.

So I started to make a sketch of the very apple orchard where Liebermann made his large painting. And then back along the road we had driven down early on. At the moment that area around Zweeloo is entirely given over to young wheat — vast, sometimes, that most tender of tender greens that I know. With above it a sky of a delicate lilac white that gives an effect — I don’t think it can be painted, but for me it’s the basic tone that one must know in order to know what the basis of other effects is.

A black earth, flat — infinite — a clear sky of delicate lilac white. That earth brings forth that young wheat — it’s as if that wheat is a growth of mould. That’s what the good, fertile fields of Drenthe are, au fond — everything in a vaporous atmosphere. Think of the Last day of creation by BRION — well, yesterday I felt that I understood the meaning of that painting.

The poor soil of Drenthe is the same, only the black earth is even blacker — like soot — not a lilac black like the furrows, and melancholically overgrown with eternally rotting heather and peat. I see that everywhere — the chance effects on that infinite background: in the peat bogs the sod huts, in the fertile areas, really primitive hulks of farmhouses and sheepfolds with low, very low walls, and huge mossy roofs. Oaks around them. When one travels for hours and hours through the region, one feels as if there’s actually nothing but that infinite earth, that mould of wheat or heather, that infinite sky. Horses, people seem as small as fleas then. One feels nothing any more, however big it may be in itself, one only knows that there is land and sky.

However, in one’s capacity as a tiny speck watching other tiny specks — leaving aside the infinite — one discovers that every tiny speck is a Millet. I passed a little old church, just exactly, just exactly the church at Gréville in Millet’s little painting in the Luxembourg; but here, instead of the little peasant with the spade in that painting, a shepherd with a flock of sheep came along the hedge. One didn’t see through to the sea in the background but only to the sea of young wheat, the sea of furrows instead of that of the waves. The effect produced: the same. I saw ploughmen, very busy now, a sand-cart, shepherds, road workers, dung-carts. In a little inn along the way drew a little old woman at the spinning wheel, little dark silhouette — like something out of a fairy tale — little dark silhouette against a bright window through which one saw the bright sky and a path through the delicate green and a few geese cropping the grass.

And then, when dusk fell — imagine the silence, the peace of that moment! Imagine, right then, an avenue of tall poplars with the autumn leaves, imagine a broad muddy road, all black mud with the endless heath on the right, the endless heath on the left, a few black, triangular silhouettes of sod huts, with the red glow of the fire shining through the tiny windows, with a few pools of dirty, yellowish water that reflect the sky, where bogwood trunks lie rotting. Imagine this muddy mess in the evening twilight with a whitish sky above, so everything black on white. And in this muddy mess a rough figure — the shepherd — a throng of oval masses, half wool, half mud, that bump into one another, jostle one another — the flock. You see it coming — you stand in the midst of it — you turn round and follow them.

With difficulty and reluctantly they progress along the muddy road. Still, there’s the farm in the distance — a few mossy roofs and piles of straw and peat between the poplars. Again the sheepfold is like a triangle in silhouette. Dark.

The door stands wide open like the entrance to a dark cave. The light from the sky behind shines through the cracks in the boards at the back. The whole caravan of masses of wool and mud disappears into this cave — the shepherd and a woman with a lantern shut the doors behind them.

That return of the flock in the dusk was the finale of the symphony that I heard yesterday. That day passed like a dream, I had been so immersed in that heart-rending music all day that I had literally forgotten even to eat and drink — I took a slice of coarse peasant bread and a cup of coffee at the little inn where I drew the spinning wheel. The day was over, and from dawn to dusk, or rather from one night to the other night, I had forgotten myself in that symphony. I came home and, sitting by the fire, it occurred to me that I was hungry, and I found I was terribly hungry. But that’s how it is here. One feels exactly as if one had been at an exhibition of one hundred masterpieces, for example. What does one get out of a day like that? Just a few scratches. And yet one gets something else out of it, too — a calm passion for work.

Above all, do write to me soon. It’s Friday today but your letter isn’t here yet; I’m looking forward to it eagerly. It takes time to get it changed, since it has to go back to Hoogeveen again and then back here again. We don’t know how it will work out, but apart from that I would now say — the simplest thing perhaps would be to send money once a month. In any event write again soon. With a handshake.

Ever yours,

Vincent.

To Theo van Gogh (letter 410)

My dear Theo,

I lay awake half the night, Theo, after I’d written to you yesterday evening.

I’m heartbroken about the fact that when I come back now, after an absence of two years, the reception at home was as friendly and kind as could be, yet at bottom nothing, nothing, nothing has changed in what I have to call blindness and stupidity to the point of desperation when it comes to understanding the situation. Which was that we were going along in the very best of ways until the moment when Pa banned me from the house — not just in a passion but also ‘because he was tired of it’. It should have been understood then that this was something so important to my succeeding or not succeeding that it was made ten times more difficult for me because of it — almost intolerable.

If I hadn’t felt the same then as I feel again now, that despite all the good intentions, despite all the friendliness of the reception, despite whatever you will, there’s a certain steely hardness and icy coldness, something in Pa that grates like dry sand, glass or tin — despite all his outward mildness — if I hadn’t already, I say, felt it then as I do now, I wouldn’t have taken it so badly then. Now I’m once again in almost unbearable indecision and inner conflict.

You understand that I wouldn’t write as I write — having undertaken the journey here of my own volition, having been the first to swallow my pride — if there wasn’t really something I’m running up against.

If I had now seen that there was any WILLINGNESS to do as the Rappards did with the best results and as we began here, also with good results, if I had now seen that Pa had also realized that he should not have barred the house to me, I would have been reassured about the future.

Nothing, nothing of all that. There wasn’t then, nor is there now any trace, any hint of a shadow of a doubt in Pa as to whether he did the right thing then.

Pa doesn’t know remorse as you and I and everyone who is human does. Pa believes in his own righteousness while you, I and other human beings are permeated with the feeling that we consist of mistakes and forlorn attempts.

I pity people like Pa, I can’t find it in my heart to be angry with them because I believe that they’re unhappier than I am myself. Why do I think they’re unhappier? Because they use even the good in them wrongly so that it works as evil — because the light that’s in them is black — spreads darkness, gloom around them. Their friendly reception desolates me — to me, the way they make the best of it, without recognizing the mistake, is even worse, if possible, than the mistake itself.

Instead of readily understanding and consequently promoting both my and indirectly their own well-being with a degree of fervour, I sense a procrastination and hesitancy in everything, which paralyzes my own passion and energy like a leaden atmosphere.

My intellect as a man tells me that I have to regard it as an unalterable fact of fate that Pa and I are irreconcilable down to the deepest depths. My compassion both for Pa and for myself tells me ‘irreconcilable? never’ — until eternity there’s a chance, one has to believe in the chance of an ultimate reconciliation. But the latter, oh why is it sadly probably ‘an illusion’?

Will you think that I’m making too much of things? Our life is an awful reality and we ourselves go on into eternity, what is — is — and our view, weighty or less weighty, takes nothing from and adds nothing to the essence of things.

That’s how I think about it when I’m lying awake at night, for instance, or that’s how I think about it in the storm in the sad twilight in the evening on the heath.

Perhaps I sometimes appear as insensitive as a wild pig during the day in everyday life, and I can readily understand that people find me coarse. When I was younger I used to think much more than now that the problem lay in coincidences or little things or misunderstandings that were groundless. But as I get older I draw back from that more and more, and I see deeper grounds. Life’s ‘an odd thing’, brother.

You can see how up and down my letters are, first I think it’s possible, then again it’s impossible. One thing is clear to me, that it doesn’t happen readily, as I said, that there’s no ‘willingness’. I’ve decided to go to Rappard and tell him that I would like it too if I could be at home, but that against all the advantages that this would have there’s a je ne sais quoi with Pa that I’m afraid I’m beginning to think is incurable, and that makes me apathetic and powerless.

Yesterday evening it’s decided that I’ll be here for a while, the next morning, despite everything, we’re back to — let’s think about it again. Go ahead, sleep on it, think about it!!! As if they HADN’T HAD 2 YEARS to think about it, OUGHT to have thought about it as a matter of course, as the natural thing.

Two years, every day a day of worry for me, for them — normal life — as if nothing had happened or nothing would happen. The burden didn’t weigh on them. You say, they don’t express it but they feel it. I DON’T BELIEVE THAT. I’ve sometimes thought it myself, but it’s not right.

People act AS they FEEL. Our ACTIONS, our swift readiness or our hesitation, that’s how we can be recognized — not by what we say with our lips — friendly or unfriendly. Good intentions, opinions, in fact that’s less than nothing.

You may think of me what you will, Theo, but I tell you it’s not my imagination, I tell you, Pa is not willing.

I see now what I saw then, I spoke out four-square AGAINST Pa then, I speak now in any event, whatever may come of it, AGAINST PA again, as being UNwilling, as making it IMPOSSIBLE. It’s damned sad, brother, the Rappards acted intelligently, but here!!!!!! And everything you did and do about it, 3/4 of it is rendered fruitless by them. It’s wretched, brother. With a handshake.

Ever yours,

Vincent.

I don’t care so much about a friendly or unfriendly reception, what grieves me is that they aren’t sorry for what they did then. They think that THEY DIDN’T DO ANYTHING then, and for me that’s going too far.

To Theo van Gogh (letter 413)

Dear brother,

I feel what Pa and Ma instinctively think about me (I don’t say reasonably).

There’s a similar reluctance about taking me into the house as there would be about having a large, shaggy dog in the house. He’ll come into the room with wet paws — and then, he’s so shaggy. He’ll get in everyone’s way. And he barks so loudly.

In short — it’s a dirty animal.

Very well — but the animal has a human history and, although it’s a dog, a human soul, and one with finer feelings at that, able to feel what people think about him, which an ordinary dog can’t do.

And I, admitting that I am a sort of dog, accept them as they are.

This home is also too good for me, and Pa and Ma and the family are so unduly fine (no feelings, though) and — and — they are ministers — many ministers. So the dog recognizes that if they were to keep him it would be too much a question of putting up with him, of tolerating him ‘IN THIS HOUSE’, so he’ll see about finding himself a kennel somewhere else.

The dog may actually have been Pa’s son at one time, and Pa himself really left him out in the street rather too much, where he inevitably became rougher, but since Pa himself forgot that years ago and actually never thought profoundly about what a bond between father and son meant, there’s nothing to be said.

Then — the dog might perhaps bite — if he were to go mad — and the village constable would have to come round and shoot him dead. Very well — yes, all that, most certainly, it is true.

On the other hand, dogs are guards. But there’s no need for that, it’s peace, and there’s no danger, there are no problems, they say. So then I keep silent.

The dog is just sorry that he didn’t stay away, because it wasn’t as lonely on the heath as it is in this house — despite all the friendliness. The animal’s visit was a weakness that I hope people will forget, and one that he’ll avoid lapsing into again.

Since I’ve had no expenses in the time I’ve been here, and because I received money from you twice here, I paid for the journey myself and also paid myself for the clothes that Pa bought because mine weren’t good enough, yet at the same time I’ve repaid the 25 guilders from friend Rappard.

I think you’ll be pleased that this has been done, it looked so careless.

Dear Theo,

Enclosed is the letter I was engaged in writing when I received your letter. To which, having read what you say attentively, I want to reply. I’ll start by saying that I think it noble of you, believing that I’m making it difficult for Pa, to take his part and give me a brisk telling-off.

I regard this as something that I value in you, even though you’re taking up arms against someone who is neither Pa’s enemy nor yours, but who definitely does, however, give Pa and you some serious questions to consider. Telling you what I tell you, that being what I feel, and asking: why is this so?

In many respects, moreover, your answers to various passages in my letter make me see sides to the questions that aren’t unfamiliar to me either. Your objections are in part my own objections, but not sufficiently. So I see once more your good will, your desire at the same time to achieve reconciliation and peace — which indeed I don’t doubt. But brother, I could also raise very many objections to your tips, only I think that would be a long-drawn-out way and that there’s a shorter way.

There’s a desire for peace and for reconciliation in Pa and in you and in me. And yet we don’t seem to be able to bring peace about. I now believe that I’m the stumbling block, and so I must try to work something out so that I don’t ‘make it difficult’ for you or for Pa any more.

I’m now prepared to make it as easy as possible, as tranquil as possible, for both Pa and you.

So you also think that it’s I who make it difficult for Pa and that I’m cowardly. So — well then, I’ll try to keep everything shut up inside me, away from Pa and from you. What’s more, I won’t visit Pa again, and I’ll stick to my proposal (for the sake of mutual freedom of thought, for the sake of not making it DIFFICULT for you either, which I fear is already inadvertently starting to be your opinion) to put an end to our agreement about the money by March, if you approve.

I’m deliberately leaving an interval for the sake of order and so that I’ll have time to take some steps that really have very little chance of success, but which my conscience won’t allow me to postpone in the circumstances.

You must accept this calmly and accept it with good grace, brother — it isn’t giving you an ultimatum. But if our feelings diverge too far, well then, we mustn’t force ourselves to act as if nothing is happening. Isn’t this your opinion too, to some extent?

You know very well, don’t you, that I consider that you’ve saved my life, that I shall NEVER forget, I’m not only your brother, your friend, even after we put an end to relations that I fear would create a false position, but at the same time I have an infinite obligation of loyalty for what you did in the past by stretching out your hand to me and by continuing to help me.

Money can be repaid, not kindness such as yours.

So let me get on with it — only I’m disappointed that a thoroughgoing reconciliation hasn’t come about now — and I’d wish that it still could, only you people don’t understand me and I fear that perhaps you never will. Send me the usual by return, if you can, then I won’t have to ask Pa for anything when I leave, which I ought to do as soon as possible.

I gave the whole of the 23.80 guilders of 1 Dec. to Pa

(having borrowed 14 guilders, and shoes and trousers came to 9 guilders)

,, ,, ,, ,, ,, ,, 25 ,, ,, 10 ,, ,, Rappard.

I only have a quarter and a few cents in my pocket. So that is the account, which you will now understand when, in addition, you know that from the 20 Nov. money, which came 1 Dec., I paid for the lodgings in Drenthe for a long period, because there had been some hitch then that was later put right, and from the 14 guilders (which I borrowed from Pa and have since given back) I paid for my journey etc.

I’m going from here to Rappard’s.

And from Rappard’s perhaps to Mauve’s. My plan, then, is to try to do everything in calmness, in order.

There’s too much in my frankly expressed opinion about Pa that I cannot take back in the circumstances. I appreciate your objections, but many of them I cannot regard as sufficient, others I already thought of myself, even though I wrote what I wrote.

I set out my feelings in strong words, and of course they’re modified by appreciation of very much that’s good in Pa — of course that modification is considerable.

Let me tell you that I didn’t know that someone aged 30 was ‘a boy’, particularly not when he may have experienced more than just anyone in those 30 years. Regard my words as the words of a boy if you wish, though.

I am not liable for your interpretation of what I say, am I? That is your business.

As to Pa, I’ll also take the liberty of putting what he thinks out of my mind as soon as we part company.

It may be politic to keep what one thinks to oneself, however it has always seemed to me that a painter, above all, had a duty to be sincere — you yourself once pointed out to me that whether people understand what I say, whether people judge me rightly or wrongly, didn’t alter the truth about me.

Well brother, know that, even if there’s any sort of a separation, I am, perhaps much more even than you know or feel, your friend and even Pa’s friend. With a handshake.

Ever yours,

Vincent.

In any event I’m not an enemy of Pa’s or yours, nor shall ever be that.

I’ve thought again about your remarks since I wrote the enclosed letter, and I’ve also spoken to Pa again. I had as good as definitely made up my mind not to stay here — regardless of how it would be taken or what might come of it — when, though, the conversation took a turn because I said: I’ve been here for a fortnight now and I don’t feel any further forward than in the first half hour. If only we’d understood each other better we’d have got all sorts of things sorted out and settled by now — I can’t waste time and I have to decide.

A door has to be open or shut. I don’t understand anything in between, and in fact it can’t exist. It has now ended up that the little room at home where the mangle is now will be at my disposal as a storeroom for my bits and pieces, as a studio too, should circumstances make this desirable. And that they’ve now started emptying the room, which wasn’t the case at first, when the case was still pending then.

I do want to tell you something that I’ve since understood better than when I wrote to you about what I thought of Pa. I’ve softened my opinion, partly because I believe I detect in Pa (and one of your tips would support this to some extent) signs that, indeed, he can’t follow me when I try to explain something. Gets stuck in part of what I say, which becomes wrong when it’s taken out of context. There may well be more than one reason for this, but old age is certainly to blame for a large part of it. Now, I respect old age and its weaknesses too, as you do, even though it may not seem so to you or you may not believe it of me. I mean that I probably humour Pa in some things that I would take amiss in a man with his full faculties — for the aforementioned reason.

I also thought of Michelet’s saying (which he had from a zoologist), ‘the male is very wild’. And because now, at this stage in my life, I know that I have strong passions, and so I should have, in my opinion — looking at myself I see that perhaps I am ‘very wild’. And yet, my passion abates when I’m faced with one who is weaker; then I don’t fight.

Although, for that matter, taking issue in words or about principles with a man who, mark you, occupies a position in society concerned with guiding people’s spiritual lives is, to be sure, not only permitted but cannot in any way be cowardly. For after all, our weapons are equal. Give this some thought, if you will, particularly since I tell you that, for many reasons, I want to give up even the battle of words because I sometimes think that Pa is no longer able to concentrate the full force of his thoughts on a single point.

In some cases, after all, a man’s age may be an added strength.

Going to the heart of the matter, I take this opportunity to tell you that I believe that it’s precisely because of Pa’s influence that you’ve concentrated more on business than was in your nature.

And that I believe that, even though you’re now so sure of your case that you must remain a dealer, a certain something in your original nature will still keep on working and perhaps react more than you expect.

Since I know that our thoughts crossed each other in our first years with G&Cie, that is that both you and I thought then about becoming painters, but so deeply that we didn’t dare to say it straight out then, even to each other, it could well be that in these later years we draw closer together. All the more so because of the effect of circumstances and conditions in the trade itself, which in the meantime has already changed compared with our early days and, in my view, will go on changing more and more.

I forced myself so much at the time, and I was so burdened by a conviction that I was certainly not a painter that, even when I left G&Cie, I didn’t turn my thoughts to it but to something else (which was in turn a second mistake, over and above the first). Being discouraged then about the possibility, because diffident, very diffident approaches to a few painters weren’t even noticed. What I’m telling you is not because I want to force you to think like me — I force no one — I’m just telling you it in brotherly, in friendly confidence.

My views may sometimes be out of proportion; that may be so. Yet I believe that there must be some truth in the nature of them, and in the action and direction. That I myself have now worked on getting the house here open again, even to the extent of having a studio here — I’m not doing it in the first place or primarily out of self-interest.

In this I see that even though we don’t understand each other in many things, there’s always a will to cooperate between you, Pa and myself, albeit in fits and starts. Since the estrangement has already lasted so long, it can’t do any harm to try to place some weight on the other side, so that we shouldn’t appear to the world, too, as being more divided than is the case, so as not to lapse into extremes in the eyes of the world.

Rappard says to me, ‘a human being isn’t a lump of peat, in so far as a human being can’t bear to be thrown up in the loft like a lump of peat and be forgotten there’ — and he points out that he thought it a great misfortune for me that I couldn’t be at home. Give this some thought, if you will. I believe that it has been regarded a little too much as if I acted capriciously or recklessly or, well, you know it better than I do, whereas I was more or less forced into things, and could do nothing other than what they wanted to see in it.

And it was precisely the biased view of seeing base objectives &c. in me that made me very cold and fairly indifferent towards many people.

Brother, once again — think a great deal at this stage in your life; I believe that you’re in danger of taking a distorted view of many things, and I believe that you should examine your life’s aim once more, and that then your life WILL BE BETTER. I don’t say it as if I knew it and as if you didn’t know it, I say it because I’m increasingly coming to see that it’s so terribly difficult to know where one is right and where one is wrong.

To Anthon van Rappard (letter 439)

My dear friend Rappard,

Thank you for your letter — which made me happy. I was pleased that you saw something in my drawings.

I won’t go into generalities about technique, but I do foresee that, precisely when I become stronger in what I’ll call power of expression than I am at this moment, people will say, not less but in fact even more than now, that I have no technique. Consequently — I’m in complete agreement with you that I must say even more forcibly what I’m saying in my present work — and I’m toiling away to strengthen myself in this respect — but — that the general public will understand it better then — no.

All the same, in my view that doesn’t alter the fact that the reasoning of the good man who asked about your work, ‘does he paint for money?’, is the reasoning of a moaner — since this intelligent creature counts it among the axioms that originality prevents one from earning money with one’s work.

Passing this off as an AXIOM, because it can decidedly not be proved as a proposition is, as I said — the usual trick of moaners — and lazy little Jesuits.

Do you think that I don’t care about technique or am not searching for it? I do — but only to the extent that — I want to say what I have to say — and where I can’t do it yet, or not well enough, I work on it to improve myself. But I don’t give a damn whether my language squares with that of these orators — (you know you made the comparison — if someone had something useful, true — necessary to say, and said it in terms that were difficult to understand, what good would it be to either speaker or audience?).

I want to stay with this point for a moment — precisely because I’ve often come across a rather curious historical phenomenon.

Let it be clearly understood: that one must speak in the audience’s mother tongue if that audience only speaks one language — that goes without saying, and it would be absurd not to take it as read.

But now the second part of the question. Given a man who has something to say and speaks in the language that his audience is also naturally familiar with.

Then — the phenomenon that the speaker of truth has little oratorical chic will manifest itself time and time again — and does not appeal to the majority of his audience — indeed is branded a man ‘slow of speech’ and despised as such.

He may consider himself lucky if there is one, or a very few at most, who are edified by him, because these listeners weren’t concerned with oratorical tirades but precisely, effectively with — the truth, usefulness, necessity of the words, which enlightened, broadened them, made them freer or more intelligent.

And now the painters — is the purpose and non plus ultra of art those singular spots of colour — that waywardness in the drawing, that which is called distinction of technique? Certainly not. If one takes a Corot, a Daubigny, a Dupré, a Millet or an Israëls — fellows who are certainly the great forerunners — their work is BEYOND THE PAINT, it stands apart from the chic fellows, just as an oratorical tirade (by, say, a Numa Roumestan) is something very different from a prayer or — a good poem.

One MUST therefore work on technique in so far as one must say what one feels better, more accurately, more profoundly, but — with the less verbiage the better. But the rest — one needn’t occupy oneself with it.

Why I say this is because I believe I’ve observed that you sometimes think things in your own work aren’t good, which to my mind are good. In my view, your technique is better than, say, Haverman’s — because already your brushstroke often has something singular, distinctive, reasoned and deliberate about it, which in Haverman is endless convention, always redolent of the studio, not of nature.

Those sketches of yours that I saw, for instance, the little weaver and the old women of Terschelling, appeal to me — they get to the heart of things. I get little but malaise and boredom from Haverman.

I’m afraid that in the future, too — and I congratulate you on it — you will ALSO hear the same comments about technique, as well as about subject and..... everything, in fact, even when that brushstroke of yours, which already has so much character, gets even more.

There are however art lovers who do, after all, appreciate precisely those things that have been painted with emotion.

Although we’re no longer in the days of Thoré and of Théophile Gautier — alas. Just think about whether it’s wise, particularly nowadays, to talk a lot about technique — you’ll say I’m doing that here myself — actually I do regret it.

But for my part, I intend to tell people consistently that I can’t paint, even when I’ve mastered my brush much better than now. You understand? — especially then, when I really will have an individual manner, more finished and even more concise than now.

I liked what Herkomer said when he opened his own art school — for a number of people who could already paint — he kindly asked his students if they would be so good as to not want to paint like him — but according to their own nature — I am concerned, he says, with setting originality free — not with winning disciples for Herkomer’s doctrine.

Lions do not ape one another.

Well, I’ve painted quite a lot these last few days, a seated girl winding shuttles for the weavers, and the figure of the weaver separately.

I’m longing for you to see my painted studies sometime — not because I’m satisfied with them myself, but because I believe that you’ll be convinced by them that I really am exercising my hand and, when I say I care relatively little for technique, it’s not because I’m saving myself trouble or trying to avoid difficulties. Because that’s not my system.

I’m also longing for you to get to know this corner of Brabant sometime — much more beautiful than the Breda side in my view. It’s delightful here at the moment.

There’s a village here — Son en Breugel, which is amazingly like Courrières, where the Bretons live — yet the figures over there are at least as beautiful. As one starts to appreciate the form more, one sometimes takes a dislike to — ‘the Dutch traditional costumes’, as they’re called on the photograph albums that they sell to foreigners.

I’m sending you herewith a little booklet about Corot — which I think you’ll enjoy reading if you don’t know it — there are several accurate biographical details in it. I saw the exhibition at the time, for which this is the catalogue.

What’s remarkable in it is that that man ripened and matured for so long. Just look at what he did at different times in his life. I’ve seen examples of his first ACTUAL work — itself the result of years of study — honest as the day is long, thoroughly sound — but how people must have despised it! Corot’s studies were a lesson to me when I saw them, and was already struck at the time by the difference from studies by many other landscape painters.

If I didn’t see more technique in your little peasant cemetery than in Corot’s studies — I’d liken it to them. In sentiment it’s identical — an endeavour to express only the intimate and the essential.

What I’m saying in this letter amounts to this — let’s try to get the hang of the secrets of technique so well that people are taken in and swear by all that’s holy that we have no technique.

Let the work be so skilful that it seems naive and doesn’t stink of our cleverness.

I don’t believe that I have reached this desirable point yet, for I don’t even believe that you, who are further on than I am, are already there.

I believe you’ll see more in this letter than nitpicking about words.

I believe that the more one has to do with nature itself — the deeper one penetrates into it — the less attraction one sees in all these studio tricks, and yet, I do want to take them as they are and see them painting. I would really like to spend a lot of time in studios.

Not in the books have I found it

And from the ‘learned’ — oh, little learned

is in De Génestet, as you know. One might say as a variant on this,

Not in the studio have I found it

And from the painters the connoisseurs } oh, little learned.

Perhaps my inserting painters or connoisseurs as equals shocks you.

But changing the subject — it’s devilishly difficult to feel nothing, not to be affected by what such moaners as ‘does he paint for money’ say. One hears that rot day in and day out, and later one gets angry with oneself for having taken any notice of it. That’s how it is with me — and I think that it must occasionally be the same with you. One doesn’t give a damn about it, but all the same it gets on one’s nerves — like when one hears someone singing off-key or is pursued by a barrel-organ with a grudge against you. Don’t you think that’s true about the barrel-organ, and also that it seems to pick on you specifically?

For wherever one goes, it’s the same old tune everywhere.

Oh, as to me — I’m going to do what I tell you — when people say this and that to me — I’m going to finish their sentences before they do — in the same way as, when I know someone is in the habit of offering me a finger instead of a hand (I pulled it off yesterday with a venerable colleague of my father’s), I for my part also have one finger ready and, keeping a straight face, carefully touch his with it when shaking hands — in a way that the man can’t say anything about it but realizes I’m bloody well getting my own back on him.

Well, I’ve recently made somebody very angry with something of the sort — does one lose anything by it? No, for in truth these people are a hindrance, and the fact that I write to you about some expressions you use is to ask you: are you sure that those who are praising technique to the skies are in good faith? I just ask it precisely because I know that your aim is to avoid studio chic.

To Theo van Gogh (letter 442)

My dear Theo,

Because it’s possible that you didn’t properly understand what I asked you before, and so that there can’t be any question later of having misunderstood something or anything like that, I say it again.

At the end of January or beginning of February I wrote to you that, on coming home, it became all too evident to me that the money which I usually received from you was regarded firstly as something PRECARIOUS, secondly as, yes, what I’ll call a gift of charity to a poor nincompoop. While I could observe that this opinion was even imparted to people who have absolutely nothing to do with it — for instance the respectable natives of these parts — and, for example, 3 times in one week I heard people who were then complete strangers to me ask, ‘why is it that you don’t sell?’ Just how pleasant everyday life is when one sees this all the time, I leave to you.

In addition to this, I had already made up my mind this summer — on account of your letting me feel the reins then, that it was in my interests to go along with this and that — just to let you feel that, for my part, if you made it difficult for me by fiddling with those reins a lot, I would leave the reins in your hands but not be on the end of them myself — in other words — if I’m not at liberty in my private life, I decline this allowance from you. In short that my work (not my private life) should be what determined whether or not I stayed on my feet financially, at least as far as the 150 francs are concerned. Summing these things up, I said in a letter at the end of January that I didn’t want to keep it exactly as it was until today, namely without any specific agreement.

That I would like, though — would even like very much — nothing better than that — to go on in the same way, provided there’s a specific agreement about supplying work.

And that to try this out I would send one thing and another by March.

Your answer was evasive, it certainly wasn’t something forthright like: Vincent, I appreciate all these complaints and I approve of us coming to an agreement that you will send me drawings monthly which you can consider as the equivalent of the 150 francs that I usually send you, so that you can consider this money as money earned. I most certainly noticed that you simply did not write anything like the above.

Well, I thought, I’ll send one thing and another by March anyway and see how it goes. I then sent 9 watercolours and 5 pen drawings, wrote to tell you that I had a 6th pen drawing as well, and the painted study of the old tower that you had especially wished for at one time. But now that I see that your expressions remain just as vague, I can do nothing other than say to you most decidedly that this is no way to behave.

As far as my work is concerned, up to now it was indeed apparently the case that you would rather I didn’t send something than that I did.

If that’s still the case — well, then in my view either I’m not worthy of your patronage or you think only too flippantly about my drawings.

I have still not withdrawn my proposal for a regular supply of work. When I speak of the fact that I want to be able to consider the 150 francs or whatever it may be, more or less as the equivalent of what I send you, in this respect it’s still a very private affair, and we leave aside altogether the question of whether or not my work has commercial value.

But then I’m more justified in the view of Tom, Dick and Harry, whom I don’t have to anticipate accusing me of living off private means or — absolutely regarding me as ‘having NO means of support’.

At the same time, it’s a sign of confidence in my future on your part, which I most certainly won’t try to force on you, though — and I tell you again that whatever you decide in this matter won’t change the past, and that I most certainly won’t ignore your help in the past and really will appreciate it.

But you have to decide entirely of your own accord whether or not our relationship will endure in the future — for the current year, say.

I end with the assurance, though, that if you refuse to enter into my proposal to supply you with work regularly (you can do whatever you like with that work as regards whether or not you deal in it, although I do in any event insist that you show it from time to time as you already did at the very outset, and rightly to my mind) then I would go ahead with a separation. It seems to me that honour is at stake — so EITHER this change OR — finished. Regards.

Yours truly,

Vincent

What I prefer not to hear later would be that this or that agreement is more a notion of mine than the intention of the other side, namely yours. You know that you told me C.M. said something of the sort to you about me this summer. As a result I learned that it was important to dot the i’s and cross the t’s where agreements are concerned.

I believe, because I already wrote to you repeatedly about this change, that by now summing it up once again, everything has been explained plainly and clearly enough, and that for my part I may also ask for a plain yes or a plain no.

The reason I haven’t sent you the 6th pen drawing yet is because, just as I insist that you show my work now and then, I’ll also occasionally let Rappard see some of my things from now on, since he knows quite a few people — and that drawing was with R. at the time and I should have got it back, but he still has it along with two other ‘winter garden’ pen drawings.

Well then, I’ve already dropped you a line about the painted study in a previous letter, that I was discouraged from sending it because if you don’t see anything in the ones from Drenthe I don’t think you’ll like this one either. It seems to me — as I recall — that among the ones from Drenthe there are some that I would do precisely the same way if I had to do them again.

For the current month I already had the following drawings, Winter garden — Pollard birches — Avenue of poplars — the Kingfisher, which I would otherwise have sent you in April.

To Theo van Gogh (letter 456)

My dear Theo,

You’re quite right to ask why I haven’t replied to you yet. I did indeed receive your letter with 150 francs enclosed. I began a letter to you, chiefly to thank you because you seemed to have understood my letter, and also to tell you that I only count on 100 francs, but actually find it hard to manage on it as long as things don’t progress. But nevertheless, if it’s 150 francs, there’s a 50 francs windfall extra in so far as our very first agreement BEFORE The Hague was only 100 francs, and if we’re only half good friends I wouldn’t want to accept more.

However, I couldn’t finish that letter, and since then I’ve wanted to write to you but I haven’t been able to find the right words. Something has happened, Theo, which most of the people here know or suspect nothing about — nor may ever know, so keep as silent as the grave about it — but which is terrible. To tell you everything I’d have to write a book — I can’t do that. Miss Begemann has taken poison — in a moment of despair, when she’d spoken to her family and people spoke ill of her and me, and she became so upset that she did it, in my view, in a moment of definite mania. Theo, I had already consulted a doctor once about certain symptoms she had. 3 days before I’d warned her brother in confidence that I was afraid she would have a nervous breakdown, and that to my regret I had to state that I believed that the B. family had acted extremely imprudently by speaking to her as they did.

Well, this didn’t help, to the extent that the people put me off for two years, and I most definitely wouldn’t accept this since I said, if there’s a question of marriage here it would have to be very soon or not at all.

Well Theo, you’ve read Mme Bovary; do you remember the FIRST Mme Bovary, who died of a nervous fit? It was something like that here, but complicated here by taking poison. She had often said to me when we were taking a quiet walk or something, ‘I wish I could die now’ — I’d never paid attention to it.

One morning, though, she fell to the ground. I still only thought it was a little weakness. But it got worse and worse. Cramps, she lost the power of speech and mumbled all sorts of only half-comprehensible things, collapsed with all sorts of convulsions, cramps etc. It was different from a nervous fit although it was very like one, and I was suddenly suspicious and said — have you taken something by any chance? She screamed ‘Yes!’ Well, I acted boldly. She wanted me to swear I’d never tell anyone about it — I said, fine, I’ll swear anything you want, but on condition that you vomit that stuff up straightaway — stick your finger down your throat until you vomit, otherwise I’ll call the others. Anyway, you understand the rest. The vomiting only half worked and I went with her to her brother Louis, and told Louis, and got him to give her an emetic, and I went straight to Eindhoven, to Dr van de Loo. It was strychnine that she took, but the dose must have been too small, or she may have taken chloroform or laudanum with it to numb herself, which would actually be an antidote to strychnine. But, in short, she then quickly took the antidote that Van de Loo prescribed. No one knows except her herself, Louis B., you, Dr van de Loo and me — and she was rushed straight to a doctor in Utrecht, and it’s been put about that she’s on a trip for the firm, which she was about to embark on anyway. I believe it’s probable that she’ll make a full recovery, but in my view there will certainly be a long period of nervous trouble, and in what form this will manifest itself — more serious or less serious – is very much the question. But she’s in good hands now. Still, you’ll understand how depressed I am because of this event.

It was such a dreadful fright, old chap; we were alone in the field when I heard that. But fortunately at least the poison has worn off now.

But what sort of a position is it, then, and what sort of a religion is it that these respectable people subscribe to? Oh, they’re simply absurd things and they make society into a sort of madhouse, into an upside-down, wrong world. Oh, that mysticism.

You understand that in these last few days everything, everything passed through my mind, and I was absorbed in this sad story. Now she’s tried this and it has not succeeded, I think she’s had such a shock that she won’t lightly try for the second time — a failed suicide is the best remedy for suicide in the future. But if she has a nervous breakdown or brain fever or something, then — — — Still, everything’s gone fairly well with her these first few days — only I fear there’ll be repercussions. Theo — old chap — I’m so upset by it. Regards, do drop me a line, because I’m speaking to NO ONE here.

Adieu,

Vincent

Do you remember that first Mme Bovary?

To Theo van Gogh (letter 484)

My dear Theo,