The hospital in Arles

On the evening of 23 December 1888, Van Gogh suffered an acute mental breakdown and cut off his ear. The police found him at home the next morning and had him admitted to hospital, where he was treated by Dr Félix Rey. Gauguin sent a telegram to Theo, who immediately took the night train to Arles. Theo and Gauguin returned to Paris on Christmas Day. Although they resumed their correspondence, Van Gogh and Gauguin would never see one another again.

Vincent’s collapse marked the first of a series of attacks of mental illness: at intervals of one to several weeks, he repeatedly spent a few days in complete confusion, plagued by unbearable fears and hallucinations, not knowing what he was doing. During most of his hospital stay he was under strict surveillance; the people near the Yellow House no longer wanted him near them, and had even submitted a petition to that effect to the mayor. Van Gogh felt betrayed by his neighbours, but, powerless to act, he was forced to resign himself to the situation. Gauguin, too, had betrayed him, not only by departing so hastily from Arles, but also by refusing to visit Van Gogh in the hospital on the day after the incident, when he was still in town, even though his friend had expressly requested it.

Van Gogh frequently quoted Pangloss, the pseudo-philosopher from Voltaire’s Candide, saying that everything always turned out for the best in this best of all possible worlds. At times he joked about his condition: having already contracted his insanity, at least he could not catch it again. He explained away things he could have blamed on others, and tried to cling to more positive thoughts.

The hospital in Arles

The asylum Saint-Paul de Mausole, Saint-Rémy

Vincent expressed deep respect for the medical profession and was filled with feelings of both gratitude and guilt towards Theo, who had invested so much money in him and now could only fear that the ‘undertaking’ would never pay off. No matter how hard Theo tried in his letters to assuage his brother’s guilty feelings, they pressed down on Vincent like a lead weight. Moreover, he was worried that everything would change for the worse in April 1889, when Theo was to marry Jo Bonger, for Theo would then have less money available, especially if he gave up his job at Boussod, Valadon & Cie – a possibility the brothers had discussed.

Van Gogh had always placed great demands on himself in order to give his utmost to his art, but now that both his mind and his body had let him down, he no longer had any faith in the future. Now he feared that he would never produce anything of importance and would remain, at best, a second-rate painter. He resigned himself to defeat.

The deterioration of his health had caused a decline in Van Gogh’s artistic production in these months. He made repetitions of canvases he thought important, such as La Berceuse and Sunflowers. Direct references to his unfortunate situation are two self-portraits with bandaged ear, a portrait of Dr Félix Rey, and two paintings of the hospital in Arles: one of a ward and the other of the garden in the inner courtyard. Most of these works are undiminished in strength and betray no sign of suffering – but given the great effort it cost him to make them, it is no wonder that he was less productive in this period.

His neighbours kept their distance, but Vincent also encountered support. Roulin helped with practical matters, and occasionally informed Theo of Vincent’s condition. He had good talks with Dr Rey. Paul Signac visited him and wrote to him. The Reverend Frédéric Salles, a Protestant clergyman living in Arles, acted as a go-between, took care of anything to do with the authorities and arranged Van Gogh’s admission to the clinic for the mentally ill of Saint-Paul de Mausole in nearby Saint-Rémy. Van Gogh realized that he was not capable of living on his own. At the beginning of May he sent Theo more than thirty paintings and one drawing, and on 8 May he let the ever-helpful Salles accompany him to the asylum.

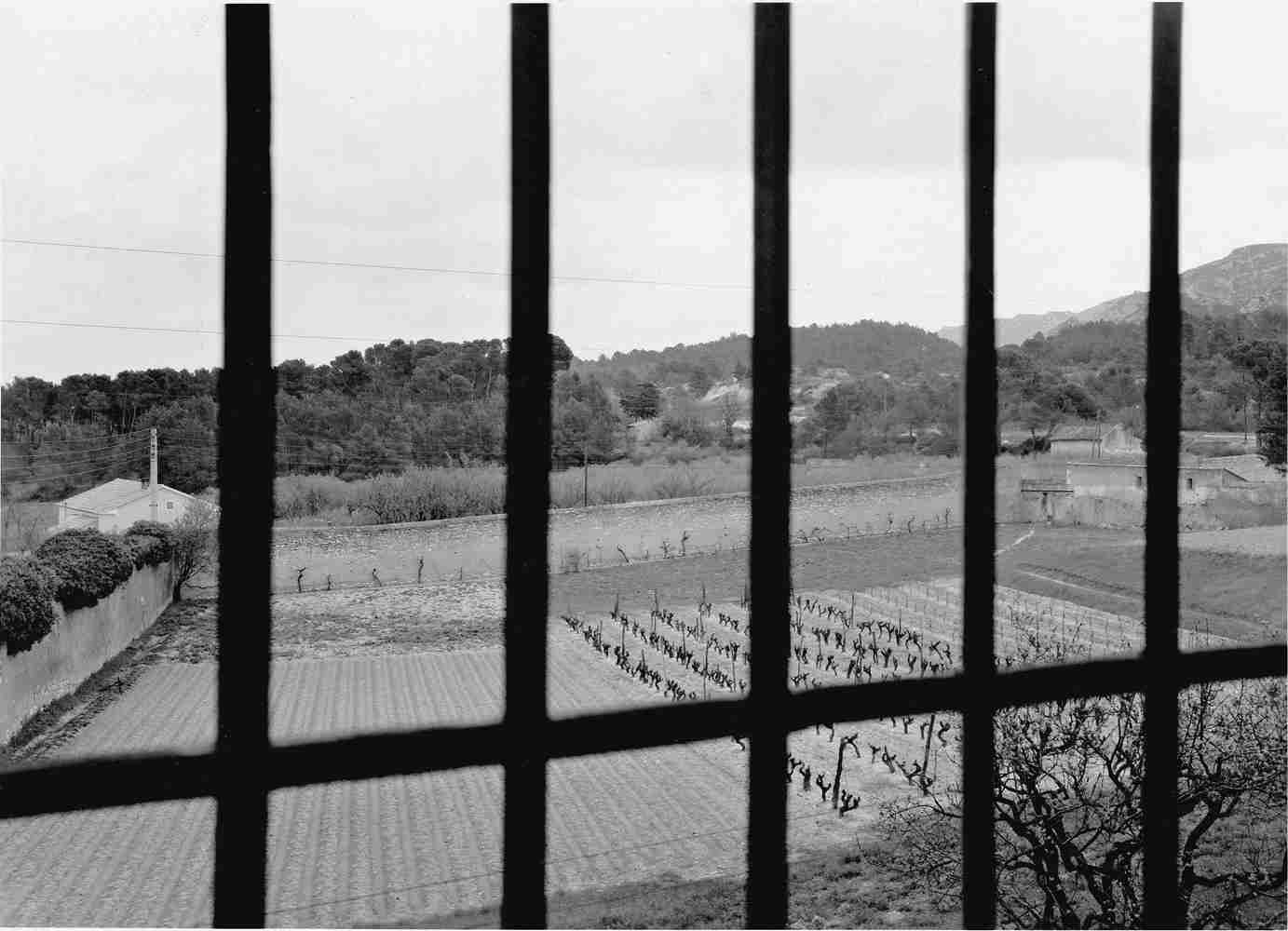

The village of Saint-Rémy-de-Provence is twenty-five kilometres northeast of Arles. The asylum where Van Gogh would spend a year of his life was originally a twelfth-century convent, and the nursing staff still included a number of nuns. Van Gogh was given a small room with a barred window and an extra room in which to work. The treatment consisted of a two-hour bath twice a week, and moderation in eating, smoking and drinking. He had little contact with his fellow sufferers, most of whom seemed to be in considerably worse shape than he was.

The view from Van Gogh’s room in Saint-Paul de Mausole

The very first letters Van Gogh wrote from the asylum make it clear that he felt safer there, and that this had a calming effect on him. He now found himself in an environment where he was no longer a danger to himself or anyone else. The severe cases all around him helped him put his own condition in perspective, and he began ‘to consider madness as being an illness like any other’ (772). Dr Théophile Peyron, the attending physician, wrote: ‘I consider that Mr van Gogh is subject to attacks of epilepsy, separated by long intervals, and that it is advisable to place him under long-term observation in the institution.’ The real cause of his illness has been the subject of much speculation; we will probably never know how he would be diagnosed today, since the necessary details are lacking. Vincent’s illness meant that he would suddenly suffer an ‘attack’ that lasted days or even weeks. Between May 1889 and May 1890, he had four such attacks, which left him in a state of complete mental derangement. He had no idea what he was doing and had self-destructive tendencies (such as eating dirt and paint), and religious delusions. After these episodes he was downcast and lacked the will to live, and it took a long time for him to find his balance.

In spite of his shaky mental health and his limited field of action, Van Gogh made a number of astonishingly strong works during his first months in Saint-Rémy. Abandoning extremes of colour, he was now preoccupied with the phenomenon of ‘style’: ‘when the thing depicted and the manner of depicting it are in accord, the thing has style and quality’ (779). A picture dating from this period, Starry Night, was one of his most thoroughgoing experiments in this respect, although later he admitted that he had gone too far in his striving for stylization. He realized that an overly systematic approach to line and brushstroke jarred with the demand he placed on all art, namely that the artist had to empathize with his subject, to feel it through and through, in order to endow the artwork with a deeply personal quality.

In the autumn of 1889 a remarkable exchange of letters developed between Van Gogh, Gauguin and Bernard. The main issue was religious art. Van Gogh’s friends had arrived at a synthetic notion of the image, which combined elements in ways and proportions that were not always ‘realistic’. They created, for example, modern biblical scenes, based in part on the religious painting of previous centuries. Van Gogh had nothing good to say about it. He found it impersonal and unsound. ‘Because I adore the true, the possible’ (822): reality was the starting point; the art of today should not rely on an outdated idiom, but invent a new one. Heated discussions of this kind put Van Gogh in great danger of losing himself.

Meanwhile a lot had changed in Theo’s life. Soon after he married Jo, in April 1889, she became pregnant. For Vincent this news was both joyful and worrying, because Theo now bore an even greater burden, and might begin to think of Vincent as a millstone around his neck. It was precisely at this time that Vincent tried to strengthen the ties with his family in the Netherlands. Since leaving Paris, he had been corresponding with his sister Willemien, but now he occasionally wrote to his mother as well. He fell back on old values and certainties, and reread William Shakespeare and Charles Dickens.

In January 1890, while working on Almond Blossom, intended as a present for his future nephew, Van Gogh had another attack of his illness (the third in Saint-Rémy). Afterwards, as he began to recover, he received in the mail the birth announcement of Vincent Willem van Gogh, who had been born on 31 January 1890. He was not particularly pleased that the baby was named after him, and suggested – too late – that the boy should be named Theo anyway, after his father and grandfather.

Van Gogh suffered another attack, between February and March; in March Theo met Paul Gachet, a doctor who lived in Auvers-sur-Oise, near Paris, whom Pissarro had recommended. Theo believed he could help Vincent, and encouraged his brother to see him.

Vincent van Gogh and Félix Rey to Theo van Gogh (letter 728)

Arles, 2 January 1889

My dear Theo,

In order to reassure you completely on my account I’m writing you these few words in the office of Mr Rey, the house physician, whom you saw yourself. I’ll stay here at the hospital for another few days — then I dare plan to return home very calmly. Now I ask just one thing of you, not to worry, for that would cause me one worry TOO MANY.

Now let’s talk about our friend Gauguin, did I terrify him? In short, why doesn’t he give me a sign of life? He must have left with you.

Besides, he needed to see Paris again, and perhaps he’ll feel more at home in Paris than here. Tell Gauguin to write to me, and that I’m still thinking of him.

Good handshake, I’ve read and re-read your letter about the meeting with the Bongers. It’s perfect. As for me, I’m content to remain as I am. Once again, good handshake to you and Gauguin.

Ever yours

Vincent

Write to me, still same address, 2 place Lamartine.

[Continued by Félix Rey]

Sir –

I shall add a few words to your brother’s letter to reassure you, in my turn, on his account.

I am happy to tell you that my predictions have been borne out, and that this over-excitement was only fleeting. I strongly believe that he will have recovered in a few days’ time.

I very much wanted him to write to you himself, to give you a better account of his condition.

I have had him brought down to my office to talk a little. It will entertain me and do him good.

With my sincerest regards.

Rey F.

To Paul Gauguin (letter 730)

My dear friend Gauguin

I’m taking advantage of my first trip out of the hospital to write you a few most sincere and profound words of friendship.

I have thought of you a great deal in the hospital, and even in the midst of fever and relative weakness.

Tell me. Was my brother Theo’s journey really necessary – my friend? Now at least reassure him completely, and yourself, please. Trust that in fact no evil exists in this best of worlds, where everything is always for the best.

So I want you to give my warm regards to good Schuffenecker –

to refrain from saying bad things about our poor little yellow house until more mature reflection on either side –

to give my regards to the painters I saw in Paris.

I wish you prosperity in Paris. With a good handshake

Ever yours,

Vincent

Roulin has been really kind to me, it was he who had the presence of mind to get me out of there before the others were convinced.

Please reply.

To Paul Gauguin (letter 739)

My dear friend Gauguin,

Thanks for your letter. Left behind alone on board my little yellow house — as it was perhaps my duty to be the last to remain here anyway — I’m not a little plagued by the friends’ departure.

Roulin has had his transfer to Marseille and has just left. It has been touching to see him these last days with little Marcelle, when he made her laugh and bounce on his knees.

His transfer necessitates his separation from his family, and you won’t be surprised that as a result the man you and I simultaneously nicknamed ‘the passer-by’ one evening had a very heavy heart. Now so did I, witnessing that and other heart-breaking things.

His voice as he sang for his child took on a strange timbre in which there was a hint of a woman rocking a cradle or a distressed wet-nurse, and then another sound of bronze, like a clarion from France.

Now I feel remorse at having perhaps, I who so insisted that you should stay here to await events and gave you so many good reasons for doing so, now I feel remorse at having indeed perhaps prompted your departure — unless, however, that departure was premeditated beforehand? And that then it was perhaps up to me to show that I still had the right to be kept frankly au courant.

Whatever the case, I hope we like each other enough to be able to begin again if need be, if penury, alas ever-present for us artists without capital, should necessitate such a measure.

You talk to me in your letter about a canvas of mine, the sunflowers with a yellow background — to say that it would give you some pleasure to receive it. I don’t think that you’ve made a bad choice – if Jeannin has the peony, Quost the hollyhock, I indeed, before others, have taken the sunflower.

I think that I’ll begin by returning what belongs to you, making it plain that it’s my intention, after what has happened, to contest categorically your right to the canvas in question. But as I commend your intelligence in the choice of that canvas I’ll make an effort to paint two of them, exactly the same. In which case it might be done once and for all and thus settled amicably, so that you could have your own all the same.

Today I made a fresh start on the canvas I had painted of Mrs Roulin, the one which had remained in a vague state as regards the hands because of my accident. As an arrangement of colours: the reds moving through to pure oranges, intensifying even more in the flesh tones up to the chromes, passing into the pinks and marrying with the olive and Veronese greens. As an Impressionist arrangement of colours, I’ve never devised anything better.

And I believe that if one placed this canvas just as it is in a boat, even one of Icelandic fishermen, there would be some who would feel the lullaby in it. Ah! my dear friend, to make of painting what the music of Berlioz and Wagner has been before us… a consolatory art for distressed hearts! There are as yet only a few who feel it as you and I do!!!

My brother understands you well, and when he tells me that you’re a kind of unfortunate like me, then that indeed proves that he understands us.

I’ll send you your things, but at times weakness overcomes me again, and then I can’t even make the gesture of sending you back your things. I’ll pluck up the courage in a few days. And the ‘fencing masks and gloves’ (make the very least possible use of less childish engines of war), those terrible engines of war will wait until then. I now write to you very calmly, but I haven’t yet been able to pack up all the rest.

In my mental or nervous fever or madness, I don’t know quite what to say or how to name it, my thoughts sailed over many seas. I even dreamed of the Dutch ghost ship and the Horla, and it seems that I sang then, I who can’t sing on other occasions, to be precise an old wet-nurse’s song while thinking of what the cradle-rocker sang as she rocked the sailors and whom I had sought in an arrangement of colours before falling ill. Not knowing the music of Berlioz. A heartfelt handshake.

Ever yours,

Vincent

It will please me greatly if you write to me again before long. Have you read Tartarin in full by now? The imagination of the south creates pals, doesn’t it, and between us we always have friendship.

Have you yet read and re-read Uncle Tom’s cabin by Beecher Stowe? It’s perhaps not very well written in the literary sense. Have you read Germinie Lacerteux yet?

To Theo van Gogh (letter 743)

My dear Theo,

Just a few words to tell you that I’m getting along so-so as regards my health and work.

Which I already find astonishing when I compare my state today with that of a month ago. I well knew that one could break one’s arms and legs before, and that then afterwards that could get better but I didn’t know that one could break one’s brain and that afterwards that got better too.

I still have a certain ‘what’s the good of getting better’ feeling in the astonishment that an ongoing recovery causes me, which I wasn’t in a state to dare rely upon.

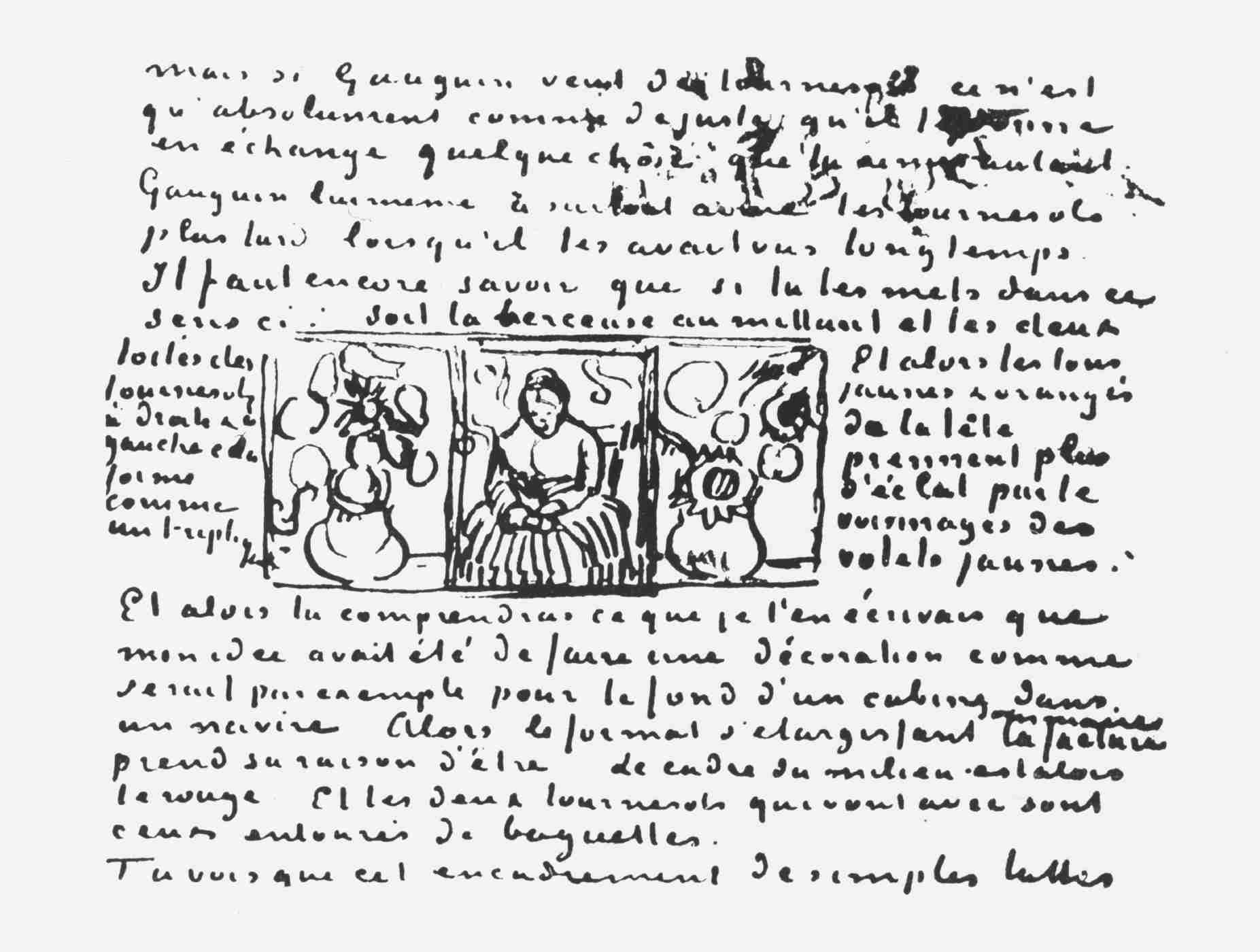

When you visited I think you must have noticed in Gauguin’s room the two no. 30 canvases of the sunflowers. I’ve just put the finishing touches to the absolutely equivalent and identical repetitions. I think I’ve already told you that in addition I have a canvas of a Berceuse, the very same one I was working on when my illness came and interrupted me. Today I also have 2 versions of this one.

On the subject of that canvas, I’ve just said to Gauguin that as he and I talked about the Icelandic fishermen and their melancholy isolation, exposed to all the dangers, alone on the sad sea, I’ve just said to Gauguin about it that, following these intimate conversations, the idea came to me to paint such a picture that sailors, at once children and martyrs, seeing it in the cabin of a boat of Icelandic fishermen, would experience a feeling of being rocked, reminding them of their own lullabies. Now it looks, you could say, like a chromolithograph from a penny bazaar. A woman dressed in green with orange hair stands out against a green background with pink flowers. Now these discordant sharps of garish pink, garish orange, garish green, are toned down by flats of reds and greens. I can imagine these canvases precisely between those of the sunflowers – which thus form standard lamps or candelabra at the sides, of the same size; and thus the whole is composed of 7 or 9 canvases.

(I’d like to make another repetition for Holland if I can get the model again.)

As it’s still winter, listen. Let me quietly continue my work, if it’s that of a madman, well, too bad. Then I can’t do anything about it.

However, the unbearable hallucinations have stopped for now, reducing themselves to a simple nightmare on account of taking potassium bromide, I think.

It’s still impossible for me to deal with this question of money in detail, but I want to deal with it in detail all the same, and I’m working furiously from morning till night to prove to you (unless my work is yet another hallucination), to prove to you that really, truly, we’re following in Monticelli’s track here and, what’s more, that we have a light on our way and a lamp before our feet in the powerful work of Bruyas of Montpellier, who has done so much to create a school in the south.

Only don’t be absolutely too amazed if, in the course of the coming month, I would be obliged to ask you for the month in full, and even the relative extra included.

After all, it’s only right if in these productive times when I expend all my vital warmth I should insist on what is necessary to take a few precautions. The difference in expenditure is certainly not excessive on my part, not even in cases like that. And once again, either lock me up in a madhouse straightaway, I won’t resist if I’m wrong, or let me work with all my strength, while taking the precautions I mention.

If I’m not mad the time will come when I’ll send you what I’ve promised you from the beginning. Now, these paintings may perhaps be fated for dispersal, but when you, for one, see the whole of what I want, you will, I dare hope, receive a consolatory impression from it.

You saw, as I did, a part of the Faure collection file past in the little window of a framer’s shop in rue Lafitte, didn’t you? You saw, as I did, that this slow procession of canvases that were previously despised was strangely interesting.

Good. My great desire would be that sooner or later you should have a series of canvases from me that could also file past in that exact same shop window.

Now, in continuing the furious work this February and March I hope I’ll have finished the calm repetitions of a number of studies I did last year. And these, together with certain canvases of mine that you already have, such as the harvest and the white orchard, will form quite a firm base. During this same time, so no later than March, we can settle what has to be settled on the occasion of your marriage.

But although I’ll work during February and March, I’ll consider myself to be still ill, and I tell you in advance that in these two months I may have to take 250 a month from the year’s allowance.

You’ll perhaps understand that what would reassure me in some way regarding my illness and the possibility of a relapse would be to see that Gauguin and I didn’t exhaust our brains for nothing at least, but that good canvases result from it. And I dare hope that one day you’ll see that in remaining upright and calm now, precisely on the question of money – it will be impossible later on to have acted badly towards the Goupils. If indirectly I’ve eaten some of their bread, certainly through you as an intermediary –

Directly I will then retain my integrity.

So, far from still remaining awkward with each other almost all the time because of that, we can feel like brothers again after that has been sorted out. You’ll have been poor all the time to feed me, but I’ll return the money or turn up my toes.

Now your wife will come, who has a good heart, to make us old fellows feel a bit younger again.

But this I believe, that you and I will have successors in business, and that precisely at the moment when the family abandoned us to our own resources, financially speaking, it will again be we who haven’t flinched.

My word, may the crisis come after that… Am I wrong about that, then?

Come on, as long as the present earth lasts there will be artists and picture dealers, especially those who are apostles at the same time, like you. And if ever we’re comfortably off, even while perhaps being old Jewish smokers, at least we’ll have worked by forging straight ahead and won’t have forgotten the things of the heart that much, even though we have calculated a little.

What I tell you is true: if it isn’t absolutely necessary to shut me away in a madhouse then I’m still good for paying what I can be considered to owe, at least in goods.

Then, my dear brother, we have 89. The whole of France shivered at it and so did we old Dutchmen, with the same heart.

Beware of 93, you may perhaps tell me.

Alas there’s some truth in that, and that being the case let’s stay with the paintings.

In conclusion I must also tell you that the chief inspector of police came yesterday to see me, in a very friendly way. He told me as he shook my hand that if ever I had need of him I could consult him as a friend. To which I’m a long way from saying no, and I may soon be in precisely that case if difficulties were to arise for the house. I’m waiting for the moment to come to pay my month’s rent to interrogate the manager or the owner face to face.

But to chuck me out they’d more likely get a kick in the backside, on this occasion at least. What can you say, we’ve gone all-out for the Impressionists, now as regards myself I’m trying to finish the canvases which will indubitably guarantee my little place that I’ve taken among them.

Ah, the future of that… but from the moment when père Pangloss assures us that everything is always for the best in the best of worlds – can we doubt it?

My letter has become longer than I intended, it matters little – the main thing is that I ask categorically for two months’ work before settling what will need to be settled at the time of your marriage.

Afterwards, you and your wife will set up a commercial firm for several generations in the renewal. You won’t have it easy. And once that’s sorted out I ask only a place as an employed painter as long as there’s enough to pay for one.

As a matter of fact, work distracts me. And I must have distractions – yesterday I went to the Folies Arlésiennes, the budding theatre here — it was the first time I’ve slept without a serious nightmare. They were performing — (it was a Provençal literary society) what they call a Noel or Pastourale, a remnant of Christian theatre of the Middle Ages. It was very studied and it must have cost them some money.

Naturally it depicted the birth of Christ, intermingled with the burlesque story of a family of astounded Provençal peasants. Good — what was amazing, like a Rembrandt etching — was the old peasant woman, just the sort of woman Mrs Tanguy would be, with a head of flint or gun flint, false, treacherous, mad, all that could be seen previously in the play. Now that woman, in the play, brought before the mystic crib — in her quavering voice began to sing and then her voice changed, changed from witch to angel and from the voice of an angel into the voice of a child and then the answer by another voice, this one firm and warmly vibrant, a woman’s voice, behind the scenes.

That was amazing, amazing. I tell you, the so-called ‘Félibres’ had anyway spared themselves neither trouble nor expense.

As for me, with this little country here I have no need at all to go to the tropics.

I believe and will always believe in the art to be created in the tropics, and I believe it will be marvellous, but well, personally I’m too old and (especially if I get myself a papier-mâché ear) too jerry-built to go there.

Will Gauguin do it? It isn’t necessary. For if it must be done it will be done all on its own.

We are merely links in the chain.

At the bottom of our hearts good old Gauguin and I understand each other, and if we’re a bit mad, so be it, aren’t we also a little sufficiently deeply artistic to contradict anxieties in that regard by what we say with the brush?

Perhaps everyone will one day have neurosis, the Horla, St Vitus’s Dance or something else.

But doesn’t the antidote exist? In Delacroix, in Berlioz and Wagner? And really, our artistic madness which all the rest of us have, I don’t say that I especially haven’t been struck to the marrow by it. But I say and will maintain that our antidotes and consolations can, with a little good will, be considered as amply prevalent. See Puvis de Chavannes’ Hope.

Ever yours,

Vincent

To Paul Signac (letter 756)

My dear friend Signac,

Thanks very much for your postcard, which gives me news of you. As for my brother not having replied to your letter yet, I’m inclined to believe that it’s not his fault. I’ve also been without news of him for a fortnight. It’s because he’s in Holland, where he’s getting married one of these days. Now, while not denying the advantages of a marriage in the very least, once it has been done and one is quietly set up in one’s home, the funereal pomp of the reception &c., the lamentable congratulations of two families (even civilized) at the same time, not to mention the fortuitous appearances in those pharmacist’s jars where antediluvian civil or religious magistrates sit – my word – isn’t there good reason to pity the poor unfortunate obliged to present himself armed with the requisite papers in the places where, with a ferocity unequalled by the cruellest cannibals, you’re married alive on the low heat of the aforementioned funereal receptions.

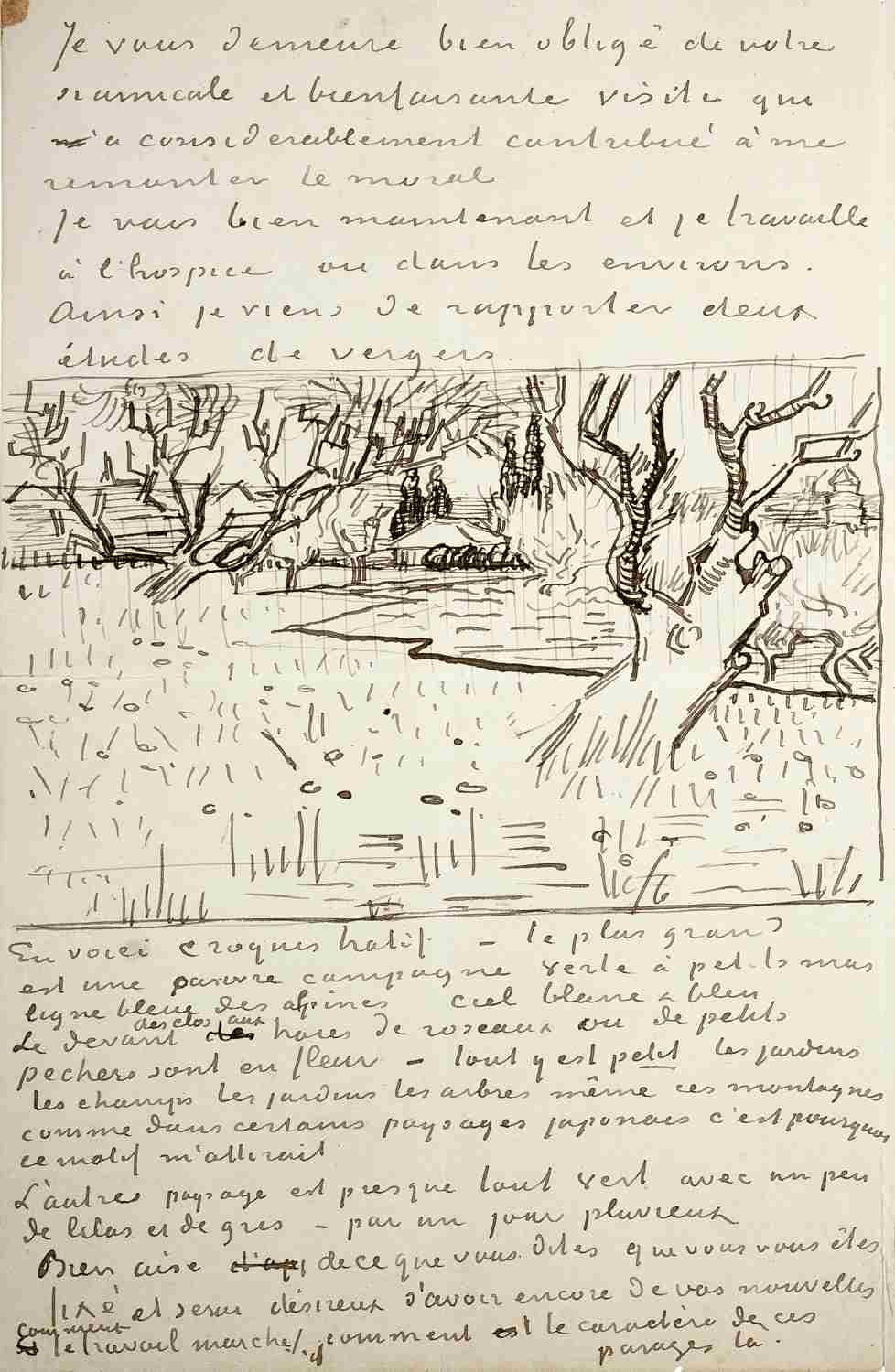

I remain much obliged to you for your most friendly and beneficial visit, which considerably contributed to cheering me up.

I am well now and I’m working in the hospital or its surroundings. Thus I’ve just brought back two studies of orchards.

[sketch A] Here’s a hasty croquis of them – the largest is a poor green countryside with little cottages, blue line of the Alpilles, white and blue sky. The foreground, enclosures with reed hedges where little peach trees are in blossom – everything there is small, the gardens, the fields, the gardens, the trees, even those mountains, as in certain Japanese landscapes, that’s why this subject attracted me.

756A. Orchard in blossom with a view of Arles

The other landscape is almost all green with a little lilac and grey – on a rainy day.

Very pleased to hear you say that you’ve settled down, and will very much wish to have more news of you. How is work going, what is the character of those parts? [sketch B]

756B. La Crau with peach trees in blossom

Since then my mind has returned yet more to the normal state, for the time being I don’t ask for better, provided it lasts. That will depend above all on a very sober regime.

For the first few months, at least, I plan to go on staying here. I’ve rented an apartment consisting of two very small rooms. But at times it isn’t completely convenient for me to start living again, for I still have inner despairs of quite a large calibre.

My word, these anxieties… who can live in modern life without catching his share of them?

The best consolation, if not the only remedy, is, it still seems to me, profound friendships, even if these have the disadvantage of anchoring us in life more solidly than may appear desirable to us in the days of great suffering.

Thank you again for your visit, which gave me so much pleasure.

Good handshake in thought.

Yours truly,

Vincent

Address until end of April, place Lamartine 2, Arles.

To Willemien van Gogh (letter 764)

My dear sister,

Your kind letter really touched me, especially since it tells me that you’ve returned to care for Mrs du Quesne.

Certainly cancer is a terrible illness, as for me, I always shiver when I see a case – and it isn’t rare in the south, although often it’s not the real incurable, mortal cancer but cancerous abscesses from which one sometimes recovers. Whatever the case, you’re very brave, my sister, not to recoil before these Gethsemanes. And I feel less brave than you when I think of these things, feeling awkward, heavy and clumsy in them. We have, if my memory serves, a Dutch proverb to this effect: they aren’t the worst fruits that wasps gnaw at…

This leads me straight to what I wanted to say, ivy loves the old lopped willows each spring, ivy loves the trunk of the old oak tree – and so cancer, that mysterious plant, attaches itself so often to people whose lives were nothing but ardent love and devotion. So, however terrible the mystery of these pains may be, the horror of them is sacred, and in them there might indeed be a gentle, heartbreaking thing, just as we see the green moss in abundance on the old thatched roof. However, I don’t know anything about it – I have no right to assert anything.

Not very far from here there’s a very, very, very ancient tomb, more ancient than Christ, on which this is inscribed, ‘Blessed be Thebe, daughter of Telhui, priestess of Osiris, who never complained about anyone.’ I couldn’t help thinking of that when you told me in your previous letter that the sick lady you’re caring for didn’t complain.

Mother must be pleased with Theo’s marriage, and he writes to me that she looks as if she’s getting younger. That pleases me greatly. Now he too is very pleased with his matrimonial experiences, and is considerably reassured.

He has so few illusions about it, having to a rare degree the strength of character to take things as they are without making pronouncements about good and evil. In which he’s quite right, for what do we know of what we do?

As for me, I’m going for at least 3 months into an asylum at St-Rémy, not far from here.

In all I’ve had 4 big crises in which I hadn’t the slightest idea of what I said, wanted, did.

Not counting that I fainted 3 times previously without plausible reason, and not retaining the least memory of what I felt then.

Ah well, that’s quite serious, although I’m much calmer since then, and physically I’m perfectly well. And I still feel incapable of taking a studio again. I’m working though, and have just done two paintings of the hospital. One is a ward, a very long ward with the rows of beds with white curtains where a few figures of patients are moving.

The walls, the ceiling with the large beams, everything is white in a lilac white or green white. Here and there a window with a pink or bright green curtain.

The floor tiled with red bricks. At the far end a door surmounted by a crucifix.

It’s very, very simple. And then, as a pendant, the inner courtyard. It’s an arcaded gallery like in Arab buildings, whitewashed. In front of these galleries an ancient garden with a pond in the middle and 8 beds of flowers, forget-me-nots, Christmas roses, anemones, buttercups, wallflowers, daisies &c.

And beneath the gallery, orange trees and oleanders. So it’s a painting chock-full of flowers and springtime greenery. However, three black, sad tree-trunks cross it like snakes, and in the foreground four large sad, dark box bushes.

The people here probably don’t see much in it, but however it has always been so much my desire to paint for those who don’t know the artistic side of a painting.

What shall I say to you, you don’t know the reasonings of good père Pangloss in Voltaire’s Candide, nor Flaubert’s Bouvard et Pécuchet. These are books from man to man, and I don’t know if women understand that. But the memory of that often sustains me in the uncomfortable and unenviable hours and days or nights.

I’ve re-read Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom with EXTREME attention precisely because it’s a woman’s book, written, she says, while making soup for her children, and then also with extreme attention C. Dickens’s Christmas Tales.

I read little so as to think about it more. It’s very likely that I have a lot more to suffer. And that doesn’t suit me at all, to tell you the truth, for I wouldn’t wish for a martyr’s career in any circumstances.

For I’ve always sought something other than the heroism I don’t have, which I certainly admire in others but which, I repeat, I do not believe to be my duty or my ideal.

I haven’t re-read those excellent books by Renan but how often I think of them here, where we have the olive trees and other characteristic plants and the blue sky. Ah, how right Renan is and what a fine work his is, to speak to us in a French like no other person speaks. A French in which, in the sound of the words, there’s the blue sky and the gentle rustling of the olive trees and a thousand true and explanatory things in short that turn his history into a resurrection. It’s one of the saddest things I know, the prejudices of people who through bias oppose so many good and beautiful things that have been created in our time. Ah, the eternal ‘ignorance’, the eternal ‘misunderstandings’, and how much good it then does to happen upon words that are truly Serene… Blessed be Thebe – daughter of Telhui – priestess of Osiris – who never complained about anyone.

For myself, I quite often worry that my life hasn’t been calm enough, all these disappointments, annoyances, changes mean that I don’t develop naturally and in full in my artistic career.

‘A rolling stone gathers no moss’

they say, don’t they?

But what does that matter if, as rightly the above-mentioned père Pangloss alone proves, ‘everything is always for the best in the best of worlds’.

Last year I did about ten or a dozen orchards in blossom and this year I have only four, so work isn’t going with much gusto.

If you have the Drône book you speak of I’d very much like to read it, but do me the pleasure of not buying it especially for me at the moment. I’ve seen some very interesting nuns here, the majority of the priests seem to me to be in a sad state. Religion has frightened me so much for so many years now. For example, do you happen to know that love perhaps doesn’t exist exactly as one imagines it – the junior doctor here, the worthiest man one could possibly imagine, the most dedicated, the most valiant, a warm, manly heart, sometimes amuses himself mystifying the little women by telling them that love is also a microbe. Although then the little women, and even a few men, let out loud shouts, he doesn’t care at all and is imperturbable on that point.

As for kissing and all the rest that it pleases us to add to it, that’s just a natural kind of act like drinking a glass of water or eating a piece of bread. Certainly it’s quite indispensable to kiss, otherwise serious disorders arise.

Now must cerebral sympathies always go with or without what precedes. Why regulate all that, eh, what’s the use?

For myself I’m not opposed to love being a microbe, and even so that wouldn’t prevent me at all from feeling things such as respect before the pains of cancer for example.

And do you see, the doctors of whom you say, sometimes they can’t do very much (which I leave you free to say as much as you consider right) – very well – do you know what they can do all the same – they give you a more cordial handshake, gentler than many other hands, and their presence can really be very pleasant and reassuring sometimes.

There you are, I’m letting myself go on and on. Yet often I can’t write two lines, and I really fear that my ideas may be futile or incoherent this time too.

Only I wanted to write to you in any case while you were there. I can’t precisely describe what the thing I have is like, there are terrible fits of anxiety sometimes – without any apparent cause – or then again a feeling of emptiness and fatigue in the mind. I consider the whole rather as a simple accident, no doubt a large part of it is my fault, and from time to time I have fits of melancholy, atrocious remorse, but you see, when that’s going to discourage me completely and make me gloomy, I’m not exactly embarrassed to say that remorse and fault are possibly microbes too, just like love.

Every day I take the remedy that the incomparable Dickens prescribes against suicide. It consists of a glass of wine, a piece of bread and cheese and a pipe of tobacco. It isn’t complicated, you’ll tell me, and you don’t think that my melancholy comes close to that place, however at moments – ah but…

Anyway, it isn’t always pleasant, but I try not to forget completely how to jest, I try to avoid everything that might relate to heroism and martyrdom, in short I try not to take lugubrious things lugubriously.

Now I wish you good-night, and my respects to your patient, although I don’t know her.

Ever yours,

Vincent

I don’t know if Lies is in Soesterberg at the moment, if she’s there, kind regards from me.

To Theo van Gogh (letter 776)

My dear Theo,

Your letter which I’ve just received gives me great pleasure. You tell me that J.H. Weissenbruch has two paintings in the exhibition — but I thought he was dead — am I mistaken? He certainly is one hell of an artist and a good man, with a big heart too.

What you say about the Berceuse gives me pleasure; it’s very true that the common people, who buy themselves chromos and listen with sentimentality to barrel organs, are vaguely in the right and perhaps more sincere than certain men-about-town who go to the Salon.

Gauguin, if he’ll accept it, you shall give him a version of the Berceuse that wasn’t mounted on a stretching frame, and to Bernard too, as a token of friendship.

But if Gauguin wants sunflowers it’s only absolutely fair that he gives you something that you like as much in exchange. Gauguin himself above all liked the sunflowers later, when he had seen them for a long time.

You must know, too, that if you put them in this order: [sketch A] that is, the Berceuse in the middle and the two canvases of the sunflowers to the right and the left, this forms a sort of triptych. And then the yellow and orange tones of the head take on more brilliance through the proximity of the yellow shutters. And then you will understand that what I was writing to you about it, that my idea had been to make a decoration like one for the far end of a cabin on a ship, for example. Then as the size gets bigger, the summary execution gets its raison d’être. The middle frame is then the red one. And the two sunflowers that go with it are those surrounded by strips of wood.

776A. Triptych with La Berceuse and two versions of Sunflowers in a vase

You see that this framing of simple laths does quite well, and a frame like that costs only very little. It would be perhaps good to frame the green and red vineyards, the sower and the furrows and the interior of the bedroom with them too.

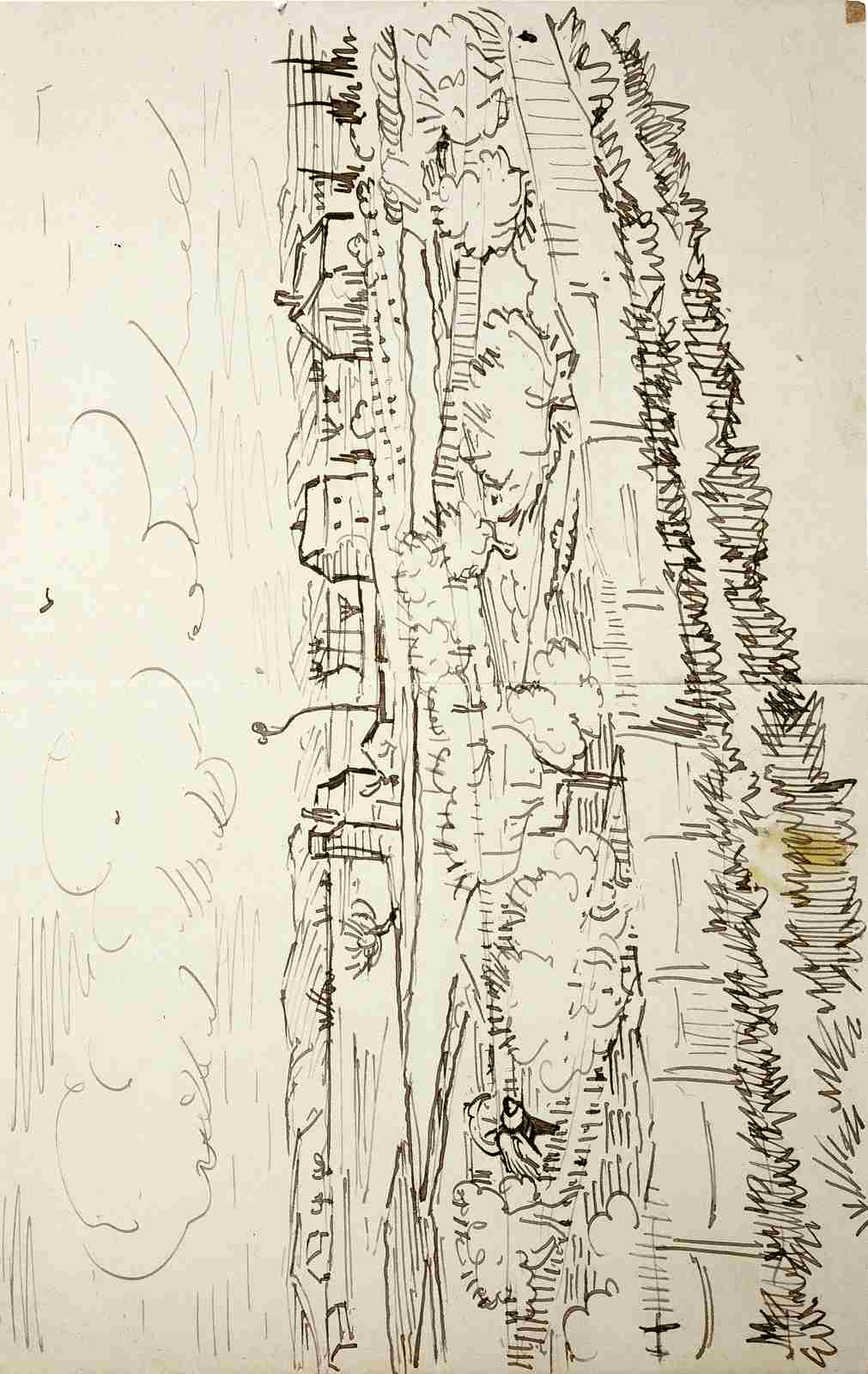

[sketch B] Here’s a new no. 30 canvas, commonplace again, like one of those chromos from a penny bazaar that depict eternal nests of greenery for lovers.

776B. Trees with ivy in the garden of the asylum

Thick tree-trunks covered with ivy, the ground also covered with ivy and periwinkle, a stone bench and a bush of roses, blanched in the cold shadow. In the foreground a few plants with white calyxes. It’s green, violet and pink.

It’s just a question — which is unfortunately lacking in chromos from a penny bazaar and barrel organs — of putting in some style.

Since I’ve been here, the neglected garden planted with tall pines under which grows tall and badly tended grass intermingled with various weeds, has provided me with enough work, and I haven’t yet gone outside.

However, the landscape of St-Rémy is very beautiful, and little by little I’m probably going to make trips into it. But staying here as I am, the doctor has naturally been in a better position to see what was wrong, and will, I dare hope, be more reassured that he can let me paint.

I assure you that I’m very well here, and that for the time being I see no reason at all to come and board in Paris or its surroundings. I have a little room with grey-green paper with two water-green curtains with designs of very pale roses enlivened with thin lines of blood-red. These curtains, probably the leftovers of a ruined, deceased rich man, are very pretty in design. Probably from the same source comes a very worn armchair covered with a tapestry flecked in the manner of a Diaz or a Monticelli, red-brown, pink, creamy white, black, forget-me-not blue and bottle green.

Through the iron-barred window I can make out a square of wheat in an enclosure, a perspective in the manner of Van Goyen, above which in the morning I see the sun rise in its glory.

With this — as there are more than 30 empty rooms — I have another room in which to work.

The food is so-so. It smells naturally a little musty, as in a cockroach-ridden restaurant in Paris or a boarding school. As these unfortunates do absolutely nothing (not a book, nothing to distract them but a game of boules and a game of draughts) they have no other daily distraction than to stuff themselves with chickpeas, haricot beans, lentils and other groceries and colonial foodstuffs by the regulated quantities and at fixed times.

As the digestion of these commodities presents certain difficulties, they thus fill their days in a manner as inoffensive as it’s cheap. But joking apart, the fear of madness passes from me considerably upon seeing from close at hand those who are affected with it, as I may very easily be in the future.

Before I had some repulsion for these beings, and it was something distressing for me to have to reflect that so many people of our profession, Troyon, Marchal, Meryon, Jundt, M. Maris, Monticelli, a host of others, had ended up like that. I wasn’t even able to picture them in the least in that state.

Well, now I think of all this without fear, i.e. I find it no more atrocious than if these people had snuffed it of something else, of consumption or syphilis, for example.

These artists, I see them take on their serene bearing again, and do you think it’s a small thing to rediscover ancient members of the profession.

Joking apart, that’s what I’m profoundly grateful for.

For although there are some who howl or usually rave, here there is much true friendship that they have for each other. They say, one must suffer others for the others to suffer us, and other very true reasonings that they thus put into practice. And between ourselves we understand each other very well, I can, for example, chat sometimes with one who doesn’t reply except in incoherent sounds, because he isn’t afraid of me.

If someone has some crisis the others look after him, and intervene so that he doesn’t harm himself.

The same for those who have the mania of often getting angry. Old regulars of the menagerie run up and separate the fighters, if there is a fight.

It’s true that there are some who are in a more serious condition, whether they be filthy, or dangerous. These are in another courtyard. Now I take a bath twice a week, and stay in it for 2 hours, then my stomach is infinitely better than a year ago, so I only have to continue, as far as I know. I think I’ll spend less here than elsewhere, since here I still have work on my plate, for nature is beautiful.

My hope would be that at the end of a year I’ll know better than now what I can do and what I want. Then, little by little, an idea will come to me for beginning again. Coming back to Paris or anywhere at the moment doesn’t appeal to me at all, I feel that I’m in the right place here. In my opinion, what most of those who have been here for years are suffering from is an extreme sluggishness. Now, my work will preserve me from that to a certain extent.

The room where we stay on rainy days is like a 3rd-class waiting room in some stagnant village, all the more so since there are honourable madmen who always wear a hat, spectacles and travelling clothes and carry a cane, almost like at the seaside, and who represent the passengers there.

I’m obliged to ask you for some more colours, and especially some canvas. When I send you the 4 canvases of the garden I have on the go you’ll see that, considering that life happens above all in the garden, it isn’t so sad. Yesterday I drew a very large, rather rare night moth there which is called the death’s head, its coloration astonishingly distinguished: black, grey, white, shaded, and with glints of carmine or vaguely tending towards olive green; it’s very big. [sketch C] To paint it I would have had to kill it, and that would have been a shame since the animal was so beautiful. I’ll send you the drawing of it with a few other drawings of plants.

776C. Giant peacock moth

You could take the canvases which are dry enough at Tanguy’s or at your place off the stretching frames and then put the new ones you consider worthy of it onto these stretching frames. Gauguin must be able to give you the address of a liner for the Bedroom who won’t be expensive. This I imagine must be a 5-franc restoration, if it’s more then don’t have it done, I don’t think that Gauguin paid more when he quite often had canvases of his own, Cézanne or Pissarro lined.

Speaking of my condition, I’m still so grateful for yet another thing. I observe in others that, like me, they too have heard sounds and strange voices during their crises, that things also appeared to change before their eyes. And that softens the horror that I retained at first of the crisis I had, and which when it comes to you unexpectedly, cannot but frighten you beyond measure. Once one knows that it’s part of the illness one takes it like other things. Had I not seen other mad people at close hand I wouldn’t have been able to rid myself of thinking about it all the time. For the sufferings of anguish aren’t funny when you’re caught in a crisis. Most epileptics bite their tongues and injure them. Rey told me that he had known a case where someone had injured his ear as I did, and I believe I’ve heard a doctor here who came to see me with the director say that he too had seen it before. I dare to believe that once one knows what it is, once one is aware of one’s state and of possibly being subject to crises, that then one can do something about it oneself so as not to be caught so much unawares by the anguish or the terror. Now, this has been diminishing for 5 months, I have good hope of getting over it, or at least of not having crises of such force. There’s one person here who has been shouting and always talking, like me, for a fortnight, he thinks he hears voices and words in the echo of the corridors, probably because the auditory nerve is sick and too sensitive, and with me it was both the sight and the hearing at the same time which, according to what Rey said one day, is usual at the beginning of epilepsy.

Now the shock had been such that it disgusted me even to move, and nothing would have been so agreeable to me as never to wake up again. At present this horror of life is already less pronounced, and the melancholy less acute. But I still have absolutely no will, hardly any desires or none, and everything that has to do with ordinary life, the desire for example to see friends again, about whom I think however, almost nil. That’s why I’m not yet at the point where I ought to leave here soon, I would still have melancholy for everything. And it’s even only in these very last days that the repulsion for life has changed quite radically. There’s still a way to go from there to will and action.

It’s a shame that you yourself are still condemned to Paris, and that you never see the countryside other than that around Paris.

I think that it’s no more unfortunate for me to be in the company where I am than for you always the fateful things at Goupil & Cie. From that point of view we’re quite equal. For only in part can you act in accordance with your ideas. Since, however, we have once got used to these inconveniences, it becomes second nature.

I think that although the paintings cost canvas, paint &c., at the end of the month, however, it’s more advantageous to spend a little more thus, and to make them with what I’ve learned in total, than to abandon them while one would have to pay for board and lodging all the same anyway. And that’s why I’m making them. So this month I have 4 no. 30 canvases and two or three drawings.

But no matter what one does, the question of money is always there like the enemy before the troops, and one can’t deny it or forget it.

I retain my duties in that respect as much as anyone. And perhaps some day I’ll be in a position to repay all that I’ve spent, because I consider that what I’ve spent is, if not taken from you at least taken from the family, so consequently I’ve produced paintings and I’ll do more. That is to act as you too act yourself. If I had private means, perhaps my mind would be freer to do art for art’s sake, now I content myself with believing that in working assiduously even so, without thinking of it one perhaps makes some progress.

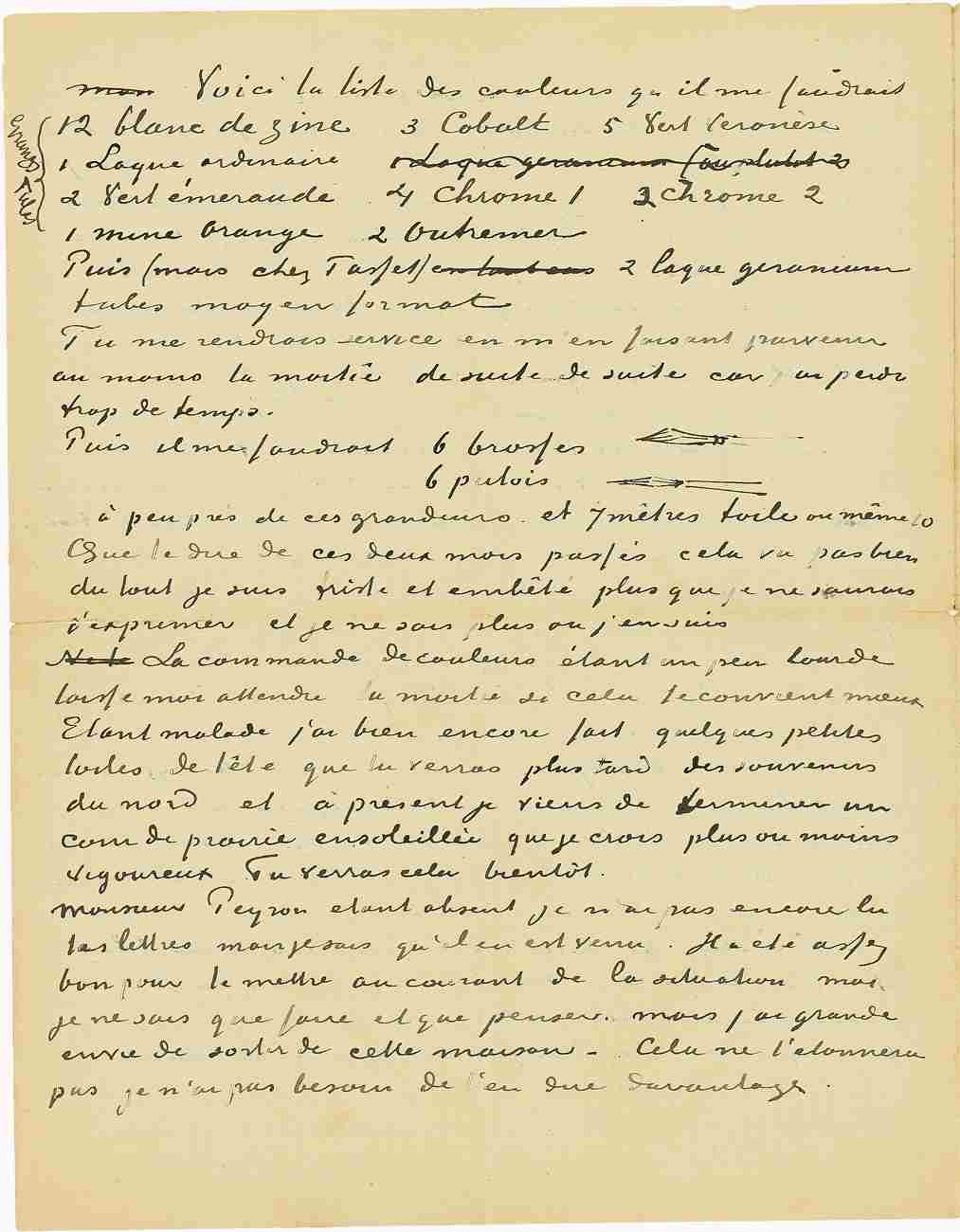

Here are the colours I would need

3 emerald green |

|

large tubes. |

Thanking you for your kind letter, I shake your hand warmly, as well as your wife’s.

Ever yours,

Vincent.

To Theo van Gogh (letter 782)

My dear Theo,

Thanks for your letter of yesterday. I too cannot write as I would wish, but anyway we live in such a disturbed age that there can be no question of having opinions that are firm enough to judge things.

I would have very much liked to know if you now still eat together at the restaurant or if you live at home more. I hope so, for in the long run that must be the best.

As for me, it’s going well – you’ll understand that after almost half a year now of absolute sobriety in eating, drinking, smoking, with two two-hour baths a week recently, this must clearly calm one down a great deal. So it’s going very well, and as regards work, it occupies and distracts me – which I need very much – far from wearing me out.

It gives me great pleasure that Isaäcson found things in my consignment that please him. He and De Haan appear very faithful, which is sufficiently rare these days for it to be worthy of appreciation. And that, as you say, there was another who found something in the yellow and black figure of a woman, that doesn’t surprise me, although I think that its merit lies in the model and not in my painting.

I despair of ever finding models. Ah, if I had some from time to time like that one, or like the woman who posed for the Berceuse, I’d do something quite different.

I think you did the right thing by not exhibiting paintings of mine at the exhibition by Gauguin and others. There’s reason enough for me to abstain from doing so without offending them as long as I’m not cured myself.

For me it’s beyond doubt that Gauguin and Bernard have great and real merit.

It’s still perfectly understandable, though, that for beings like them, really alive and young, who must live and try to carve out their path, it’s impossible to turn all their canvases to the wall until it pleases people to admit them somewhere in the official pickle. One causes a stir by exhibiting in the cafés, which I don’t say isn’t in bad taste. But for myself, I have that crime on my conscience, and to the point of doing it twice, having exhibited at the Tambourin and at avenue de Clichy. Not counting the disturbance caused to 81 virtuous cannibals of the good town of Arles and to their excellent mayor.

So in any case, I am worse and more blameworthy than they are in that regard (causing a stir quite involuntarily, my word).

Young Bernard – according to me – has already made a few absolutely astonishing canvases in which there’s a gentleness and something essentially French and candid, of rare quality.

Anyway, neither he nor Gauguin are artists who could look as if they were trying to go to the World Exhibition by the back stairs. You can be sure of that. It’s understandable that they couldn’t keep silent. That the Impressionists’ movement has had no unity is what proves that they’re less skilled fighters than other artists like Delacroix and Courbet.

At last I have a landscape with olive trees, and also a new study of a starry sky.

Although I haven’t seen the latest canvases either by Gauguin or Bernard, I’m fairly sure that these two studies I speak of are comparable in sentiment. When you’ve seen these two studies for a while, as well as the one of the ivy, I’ll perhaps be able to give you, better than in words, an idea of the things Gauguin, Bernard and I sometimes chatted about and that preoccupied us. It’s not a return to the romantic or to religious ideas, no. However, by going the way of Delacroix, more than it seems, by colour and a more determined drawing than trompe-l’oeil precision, one might express a country nature that is purer than the suburbs, the bars of Paris. One might try to paint human beings who are also more serene and purer than Daumier had before him. But of course following Daumier in the drawing of it. We’ll leave aside whether that exists or doesn’t exist, but we believe that nature extends beyond St-Ouen.

Perhaps, while reading Zola, we are moved by the sound of the pure French of Renan, for example.

And after all, while Le Chat Noir draws women for us after its own fashion, and above all Forain does so in a masterly way, we do some of our own, less Parisian but no less fond of Paris and its elegances, we try to prove that something else quite different exists.

Gauguin, Bernard or I will all remain there perhaps, and won’t overcome but neither will we be overcome. We’re perhaps not there for one thing or the other, being there to console or to prepare for more consolatory painting. Isaäcson and De Haan may not succeed either, but in Holland they’ve felt the need to state that Rembrandt did great painting and not trompe l’oeil, they also felt something different.

If you can get the Bedroom lined it’s better to have it done before sending it to me.

I have no more white at all at all.

You’ll give me a lot of pleasure if you write to me again soon. I so often think that after a while you’ll find in marriage, I hope, the means to gain new strength, and that a year from now your health will have improved.

What I’d very much like to have here to read from time to time would be a Shakespeare. There’s one priced at one shilling, Dicks’ Shilling Shakespeare, which is complete. There’s no shortage of editions, and I think the cheap ones have been changed less than the more expensive ones. In any case I wouldn’t want one that cost more than three francs.

Now, whatever is too bad in the consignment, put it completely to one side, pointless to have stuff like that; it may be of use to me later to remind me of things. Whatever is good will show up better by being part of a smaller number of canvases. The rest, if you put them in a corner, flat between two sheets of cardboard with old newspapers between the studies, that’s all they’re worth.

I’m sending you a roll of drawings.

Handshakes to you, to Jo and to our friends.

Ever yours,

Vincent

The drawings Hospital in Arles, the weeping tree in the grass, the fields and the olive trees, are a continuation of those from Montmajour from back then. The others are hasty studies done in the garden.

There’s no hurry for the Shakespeare, if they don’t have an edition like that, it won’t take an eternity to have one sent.

Don’t be afraid that I would ever venture onto dizzy heights of my own free will, unfortunately, whether we like it or not, we’re subject to circumstances and to the illnesses of our time. But with all the precautions I’m now taking, it will be difficult for me to relapse, and I hope that the attacks won’t start again.

To Theo van Gogh (letter 790)

My dear Theo,

If I’m writing to you again today it’s because I’m enclosing a few words that I’ve written to our friend Gauguin, feeling sufficient calm return to me these last few days for my letter not to be absolutely absurd, it seemed to me. Besides, there’s no proof that by over-refining one’s scruples of respect or feeling one thereby gains respectfulness or good sense. That being so, it does me good to talk with the pals again, even if at a distance. And you – my dear fellow – how are things, and so write me a few words one of these days – for I can imagine that the emotions which must move the forthcoming father of a family, emotions of which our good father so loved to speak, must be great and of sterling worth in you, as in him, but for the moment are almost impossible for you to express in the rather incoherent mixture of the petty vexations of Paris. Realities of this sort must anyway be like a good gust of the mistral, not very soothing, but health-giving. As for me, it gives me very great pleasure I can assure you, and will contribute greatly to bringing me out of my moral fatigue and perhaps from my listlessness.

Anyway, there’s enough to bring back the taste for life a little when I think that I myself am going to be promoted uncle of this boy planned by your wife. I find it quite funny that she’s so convinced that it’s a boy, but anyway, we’ll see.

Anyway, in the meantime I can do nothing but fiddle with my paintings a little. I have one on the go of a moonrise over the same field as the croquis in the Gauguin letter, but in which stacks replace the wheat. It’s dull ochre-yellow and violet. Anyway, you’ll see in a while from now.

I also have a new one with ivy on the go. Above all, dear fellow, I beg of you, don’t fret or worry or be melancholy on my account, the idea that you would do so, certainly in this necessary and salutary quarantine, would have little justification when we need a slow and patient recovery. If we manage to grasp that, we spare our forces for this winter. I imagine that winter must be quite dismal here, anyway will however have to try and occupy myself. I often imagine that I could retouch a lot of last year’s studies from Arles this winter.

Thus, having kept back these past few days a large study of an orchard which was very difficult (it’s the same orchard of which you’ll find a variation in the consignment, but quite a vague one), I’ve set to reworking it from memory, and have found a way better to express the harmony of the tones.

Tell me, have you received any drawings from me? I sent you some once, by parcel post, half a dozen, and then later ten or so. If by chance you haven’t received them, they must have been at the railway station for days and weeks.

The doctor was telling me about Monticelli, that he had always considered him eccentric, but as for mad, he had only been a little that way towards the end. Considering all the miseries of M’s last years, is it any surprise that he bowed beneath a weight that was too heavy, and is one right in trying to deduce from that that he failed in his work, artistically speaking? I dare to believe not. There was some very logical calculation about him, and an originality as a painter, so it remains regrettable that one wasn’t able to sustain it so as to make its blossoming more complete.

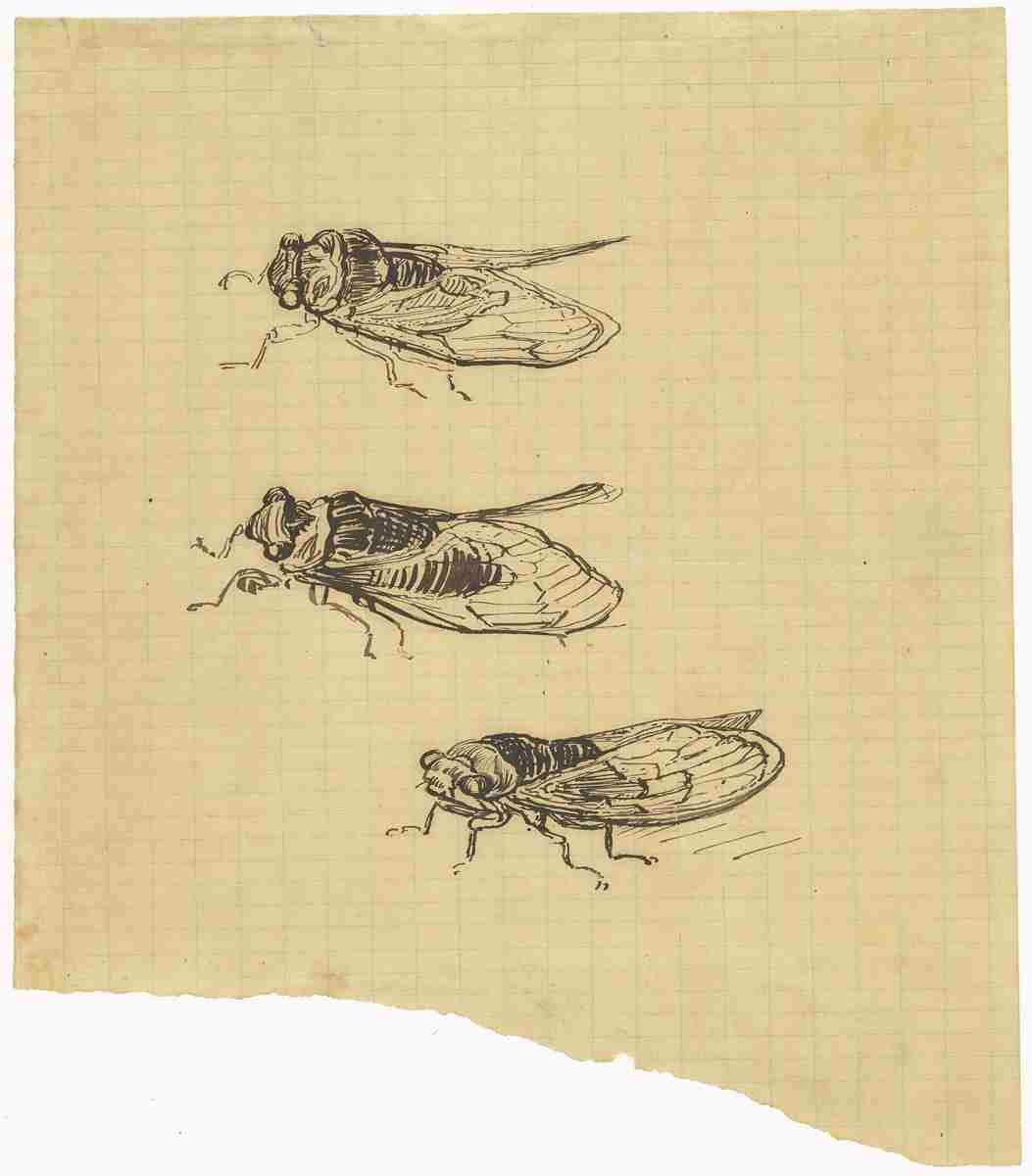

I enclose a croquis of the cicadas from here.

Their song in times of great heat holds the same charm for me as the cricket in the peasant’s hearth at home. My dear fellow – let’s not forget that small emotions are the great captains of our lives, and that these we obey without knowing it. If it’s still hard for me to regain courage over faults committed and to be committed, which would be my recovery, let’s not forget from that moment on that neither our spleens and melancholies nor our feelings of good nature and good sense are our sole guides, and above all not our final custodians, and that if you yourself also find yourself facing hard responsibilities to venture, if not to take, my word let’s not be too concerned with each other, while it so happens that life’s circumstances in situations so far removed from our youthful conceptions of the life of the artist would render us brothers after all, as being companions in fate in many respects. Things are so closely connected that here one sometimes finds cockroaches in the food as if one were really in Paris, on the other hand it can happen in Paris that you sometimes have a real thought of the fields. It’s certainly not much, but it’s reassuring anyway. So take your fatherhood as a good fellow from our old heaths would take it, those heaths that remain ineffably dear to us through all the noise, tumult, fog, anguish of the towns, however timid our tenderness may be. That’s to say, take your fatherhood there, from your nature as an exile and a foreigner and a poor man, henceforth basing himself with the poor man’s instinct on the probability of the real existence of a native country, of a real existence at least of the memory, even while we’ve forgotten every day. Thus sooner or later we find our fate. But certainly for you, as well as for me, it would be a little hypocritical to forget completely our good humour, the confident sloppiness we had as the poor devils we were as we came and went in that Paris, so strange now – and to place too much weight upon our cares.

Truly, I’m so pleased with the fact that if sometimes there are cockroaches in the food here, in your home there is wife and child.

Besides, it’s reassuring that Voltaire, for example, left us free to believe not absolutely all of what we imagine. Thus while sharing your wife’s concerns about your health I’m not going so far as to believe what momentarily I was imagining, that worries about me were the cause of your relatively rather long silence in respect of me, although this is so well explained when one thinks of how preoccupying a pregnancy must necessarily be. But it’s very good and it’s the path where everyone walks in life. More soon, and good handshake to you and to Jo.

Ever yours,

Vincent.

In haste, but didn’t want to delay sending the letter for our friend Gauguin, you must have the address.

[sketch A]

790A. Three cicadas

To Theo van Gogh (letter 798)

My dear Theo,

Since I wrote to you I’m feeling better, and whilst I don’t know if it’ll last I don’t want to wait any longer to write to you again.

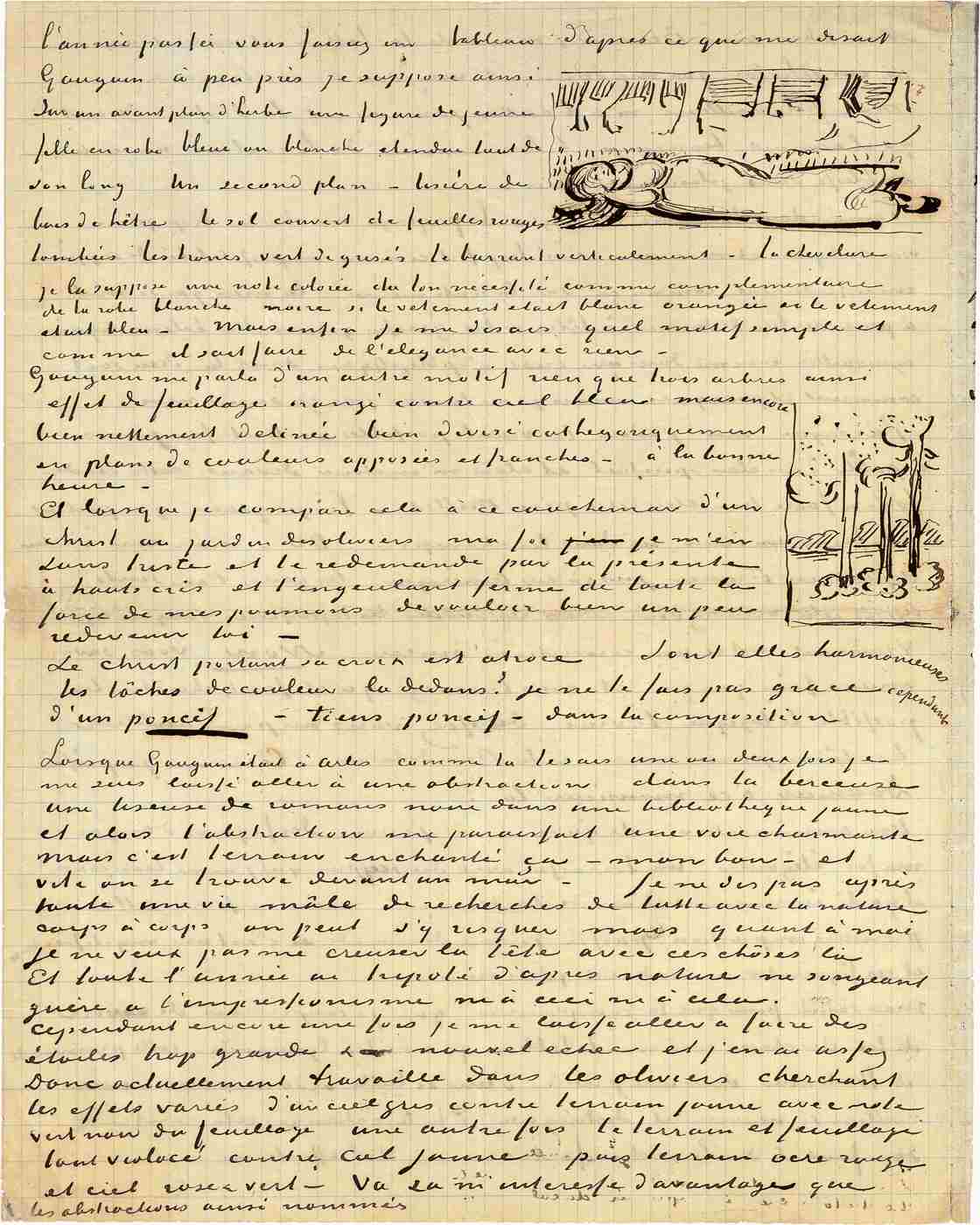

Thanks once again for that beautiful etching after Rembrandt. I’d very much like to get to know the painting and know in which period of his life he painted it. All this goes with the Rotterdam portrait of Fabritius, the traveller in the La Caze gallery, into a special category in which the portrait of a human being is transformed into something luminous and consoling.

And how very different this is from Michelangelo or Giotto, although the latter however comes close to it, and Giotto thus forms a sort of possible hyphen between the school of Rembrandt and the Italians.

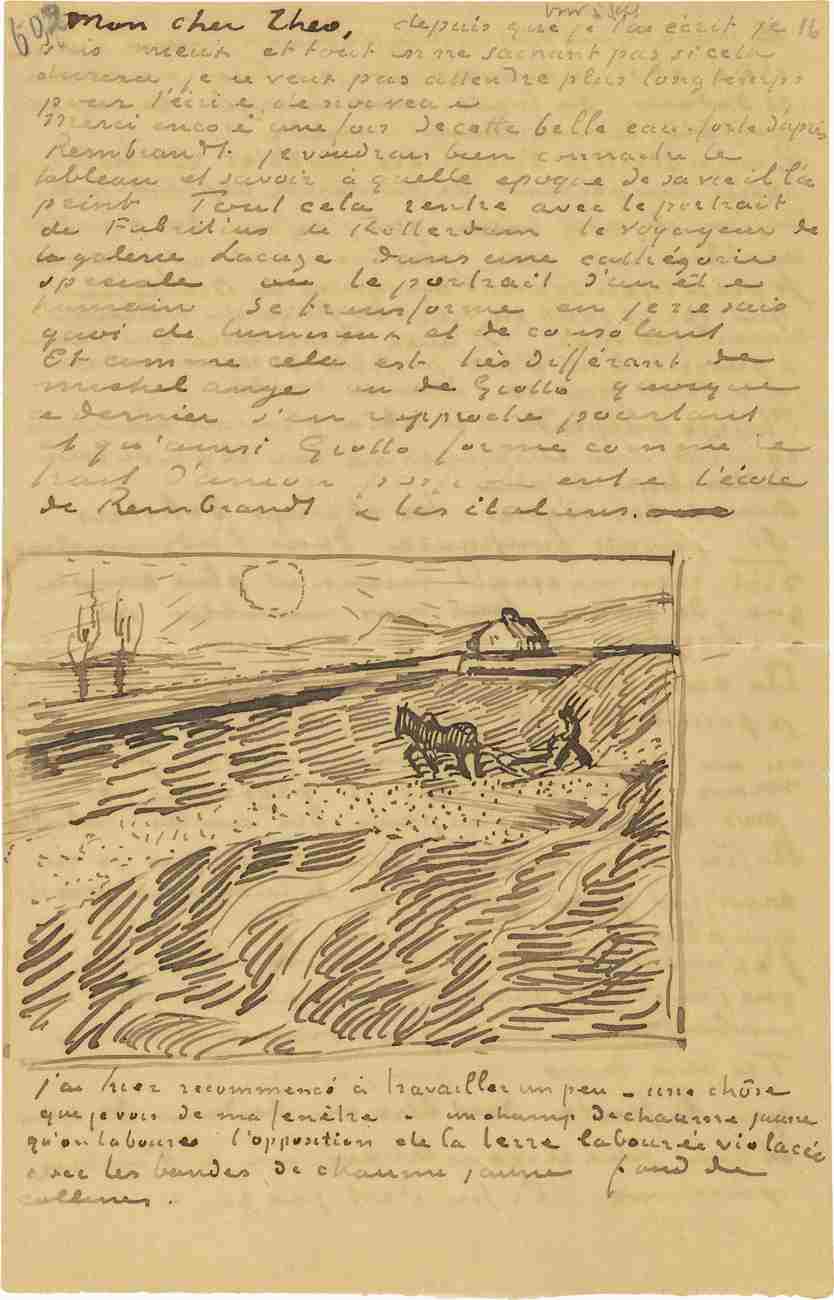

[sketch A] Yesterday I started working again a little – a thing I see from my window – a field of yellow stubble which is being ploughed, the opposition of the purplish ploughed earth with the strips of yellow stubble, background of hills.

798A. Field with a ploughman

Work distracts me infinitely better than anything else, and if I could once really throw myself into it with all my energy that might possibly be the best remedy.

The impossibility of having models, a heap of other things, prevent me from managing it however. Anyway, I really must try to take things a little passively and be patient.

I often think of our pals in Brittany, who are certainly doing better work than I am. If, with the experience I’m having at present, it was possible for me to begin again, I wouldn’t go and look around the south.

Were I independent and free, I would nevertheless have retained my enthusiasm, for there are some really beautiful things to do.

Such as the vineyards, the fields of olive trees. If I had confidence in the management here, nothing would be better and simpler than to put all my furniture here at the hospital and quietly continue. If I were to recover, or in the intervals, I could sooner or later come back to Paris or Brittany for a time. But first they’re very expensive here, and then I’m afraid of the other patients at the moment. Anyway, a heap of reasons mean that I don’t think I’ve been lucky here either.

I’m perhaps exaggerating in the sadness I feel at being knocked down by illness again – but I feel a kind of fear. You’ll tell me what I tell myself too, that the fault must be inside me and not in the circumstances or other people. Anyway, it isn’t fun.

Mr Peyron has been kind to me and he has long experience, I shan’t scorn what he says or considers good.

But will he have a firm opinion, has he written anything definite to you?? And possible?

You can see that I’m still in a very bad mood, it’s because things aren’t going well. Then I consider myself imbecilic to go and ask doctors for permission to make paintings. Besides, it’s to be hoped that if I recover sooner or later, up to a certain point it’ll be because I’ve cured myself by working, which fortifies the will and consequently allows these mental weaknesses less hold.

My dear brother, I wanted to write to you better than this, but things aren’t going very well. I have a great desire to go into the mountains to paint for whole days, I hope they’ll allow me to in the coming days.

You’ll soon see a canvas of a hut in the mountains which I did under the influence of that book by Rod. It would be good for me to stay on a farm for a while, at least I might do some good work there.

I must write to Mother and to Wil in the next few days. Wil asked to be sent a painting, and I’d very much like to give one to Lies as well on the same occasion, who doesn’t have any yet as far as I know.

What do you say about Mother going to live in Leiden? I think she’s right in this sense, that I can understand that she’s pining for her grandchildren. And then there’ll be none of us left in Brabant.

Speaking of that – not very long ago in Arles I was reading a book, I can’t remember which one, by Henri Conscience. It’s excessively sentimental if you like, what with his peasants, but speaking of Impressionism do you know that it contains descriptions of landscape with colour notes of accuracy, feeling and primitiveness of the first order. And it’s always like that. Ah my dear brother, those heaths in the Kempen were something though. But anyway, that won’t come back, and onward we go.

He – Conscience – described a brand-new little house with a bright red slate roof in the full sunshine, a garden with dock and onions, potatoes with dark foliage, a beech hedge, a vineyard, and further on the pine trees, the broom all yellow. Don’t be afraid, it wasn’t like a Cazin, it was like a Claude Monet. Then there’s originality even in the excess of sentimentality.

And as for me, who feels it and can’t damned well do anything, isn’t that sickening.

If you get opportunities for lithographs of Delacroix, Rousseau, Diaz &c., ancient and modern artists, Galeries modernes &c., I can’t advise you too strongly to hold onto them, for you’ll see that they’ll become rare. Yet it was really the way to popularize beautiful things, those 1-franc sheets of those days, those etchings &c. back then. Very interesting the Rodin – Claude Monet brochure. How I’d have liked to see that. Pointless to say that nevertheless I don’t agree when he says that Meissonier is nothing and that T. Rousseau isn’t much. Meissoniers and Rousseaus are something highly interesting for those who like them and try to discover what the artist was feeling. It isn’t possible for everyone to be of that opinion, because one has to have seen and looked at them, and you don’t find that on every corner. Now a Meissonier, if you look at it for a year there’s still enough in it to look at the next year, never fear. Not to mention that he’s a man who had his days of happiness, of perfect finds. Certainly I know, Daumier, Millet, Delacroix have another way of drawing – but Meissonier’s execution, that something essentially French above all, although the old Dutchmen would find nothing to fault in it, and yet it’s something other than them and it’s modern; one has to be blind to believe that Meissonier isn’t an artist and – one of the first rank.

Have many things been done that give the note of the 19th century better than the portrait of Hetzel? When Besnard did those two very beautiful panels, primitive man and modern man, which we saw at Petit’s, in making the modern man a reader he had the same idea.

And I’ll always regret that in our times people believe in the incompatibility of the generation of, say, 48 and the present one. I myself believe that the two hold their own all the same, though I can’t prove it.

Let’s take good Bodmer for example. Was he not able to study nature as a hunter, a savage, did he not love it and know it with experience of an entire long manly life – and do you think that the first Parisian to come along who goes to the suburbs knows as much or more about it because he’ll do a landscape with harsher tones? Not that it’s bad to use pure and clashing tones, not that from the point of view of colour I’m always an admirer of Bodmer, but I admire and I like the man who knew all the forest of Fontainebleau, from the insect to the wild boar and from the stag to the lark. From the tall oak and the lump of rock to the fern and the blade of grass.

Now a thing like that, not anyone who wants to can feel it or find it.

And Brion – oh a maker of Alsatian genre paintings people will tell me. That’s fine, he has indeed done the Engagement meal, the Protestant wedding &c. which are indeed Alsatian. When no one is up to illustrating Les Misérables, he however does it in a manner unsurpassed up to now, and he isn’t mistaken in his types. Is it a small thing to know people so well, the humanity of that period, so well that one scarcely makes a mistake in expression and type?

Ah – the rest of us would have to get old working hard, and that’s why we then get despondent when things don’t go right.

I think that if you see the Bruyas museum in Montpellier one day, I think that then nothing will move you more than Bruyas himself, when one realizes from his purchases what he sought to be for artists. It’s a little disheartening when one sees from certain portraits of him how heartbroken and obviously frustrated his face is. If one doesn’t succeed in the south there still remains he who suffered all his life for that cause.

The only serene portraits are the Delacroix and the Ricard.

For example, by a great chance the one by Cabanel is accurate and most interesting as an observation, at least it gives an idea of the man.

I’m pleased that Jo’s mother has come to Paris. Next year it will perhaps be a little different and you’ll have a child, and that brings a fair few petty vexations of human life – but as certain great miseries of spleen etc. will disappear for ever, that’s certainly how it should go.

I’ll write to you again soon, I’m not writing to you as I would have wished, I hope that all is well at your place and will continue to go well. Am very, very pleased that Rivet has rid you of the cough, which really worried me a bit too.

What I had in my throat is starting to disappear, I’m still eating with some difficulty, but anyway it has got better.

Good handshake to you and to Jo.

Ever yours,

Vincent.

To Theo van Gogh (letter 801)

My dear Theo,

I think your letter is really good, what you say about Rousseau and artists like Bodmer, that they are men in any case, and of such a kind that one would wish the world populated with people like that – yes indeed, that’s what I myself feel too.

And that J.H. Weissenbruch knows and does the muddy towpaths, the stunted willows, the foreshortenings and the learned and strange perspectives of the canals ‘as Daumier does his lawyers’, I think that’s perfect. Tersteeg did well to buy some of his work from him, the fact that people like that don’t sell, according to me that’s because there are too many sellers who try to sell other things, with which they deceive the public and mislead them.

Do you know that today, still, when I read by chance the story of some energetic industrialist or above all a publisher, that the same feelings of indignation then come to me again, the same feelings of anger from the old days when I was with G.&Cie.

Life goes on like that, time doesn’t come back, but I’m working furiously, because of the very fact that I know that the opportunities to work don’t come back.

Above all, in my case, where a more violent crisis may destroy my ability to paint forever. In the crises I feel cowardly in the face of anguish and suffering – more cowardly than is justified, and it’s perhaps this very moral cowardice which, while before I had no desire whatsoever to get better, now makes me eat enough for two, work hard, take care of myself in my relations with the other patients for fear of relapsing – anyway I’m trying to get better now like someone who, having wanted to commit suicide, finding the water too cold, tries to catch hold of the bank again.

My dear brother, you know that I came to the south and threw myself into work for a thousand reasons.

To want to see another light, to believe that looking at nature under a brighter sky can give us a more accurate idea of the Japanese way of feeling and drawing. Wanting, finally, to see this stronger sun, because one feels that without knowing it one couldn’t understand the paintings of Delacroix from the point of view of execution, technique, and because one feels that the colours of the prism are veiled in mist in the north.

All of this remains somewhat true. Then when one also adds to it an inclination of the heart towards this south that Daudet did in Tartarin, and the fact that here and there I’ve also found friends and things that I love here.

Will you then understand that while finding my illness horrible I feel that all the same I’ve entered into attachments that are a little too strong here – attachments which could mean that later on the desire to work here will take hold of me again – while all the same it may well be that I’ll return to the north relatively soon.

Yes, for I don’t hide from you the fact that in the same way that I’m taking my food avidly at present, I have a terrible desire that comes to me to see my friends again and to see the northern countryside again.

Work is going very well, I’m finding things that I’ve sought in vain for years, and feeling that I always think of those words of Delacroix that you know, that he found painting when he had neither breath nor teeth left. Ah well, I myself with the mental illness I have, I think of so many other artists suffering mentally, and I tell myself that this doesn’t prevent one from practising the role of painter as if nothing had gone wrong.

When I see that crises here tend to take an absurd religious turn, I would almost dare believe that this even necessitates a return to the north. Don’t speak too much about this to the doctor when you see him – but I don’t know if this comes from living for so many months both at the hospital in Arles and here in these old cloisters. Anyway I ought not to live in surroundings like that, the street would be better then. I am not indifferent, and in the very suffering religious thoughts sometimes console me a great deal. Thus this time during my illness a misfortune happened to me – that lithograph of Delacroix, the Pietà, with other sheets had fallen into some oil and paint and got spoiled.

I was sad about it – then in the meantime I occupied myself painting it, and you’ll see it one day, on a no. 5 or 6 canvas I’ve made a copy of it which I think has feeling – besides, having not long ago seen the Daniel and the Odalisques and the Portrait of Bruyas and the Mulatto woman at Montpellier, I’m still under the impression that it had on me. This is what edifies me, as does reading a fine book like one by Beecher Stowe or Dickens. But what disturbs me is constantly seeing those good women who believe in the Virgin of Lourdes and make up things like that, and telling oneself that one is a prisoner in an administration like that, which very willingly cultivates these unhealthy religious aberrations when it ought to be a matter of curing them. So I say, it would be even better to go, if not into penal servitude then at least into the regiment.

I reproach myself for my cowardice, I ought to have defended my studio better, even if I had to fight with those gendarmes and neighbours. Others in my position would have used a revolver, and indeed, had one killed onlookers like that as an artist one would have been acquitted. I would have done better in that case then, and now I was cowardly and drunk.

Ill too, but I wasn’t brave. Then in the face of the Suffering of these crises I feel very fearful too, and so I don’t know if my zeal is something other than what I say, it’s like the man who wants to commit suicide, and finding the water too cold he struggles to catch hold of the bank again.