7

The Irreplaceable Theodoret

Patronage Performance and Social Strategy

At some point amid the doctrinal feuding of 434, Theodoret accepted a (non-doctrinal) request from a friend. Palladius, a philosopher, had legally contracted for a soldier to protect him. But “barbarians,” had “tossed this [soldier] to the denouncers,” probably to try him for desertion. Theodoret penned two letters to deal with the situation. First, he wrote to Titus, the general overseeing the proceedings. “Justice has many enemies,” Theodoret noted, “but injustice yields if the lovers of justice join the contest.” The bishop praised the fairness of his military correspondent as he asked for an “unbribed decision.” He encouraged the general to sympathize with the defendant.1 Meanwhile, Theodoret wrote Palladius about the case. After musing on the wretchedness of this life, he pointed to a source of solace, “the instructions of God.” The bishop quoted Thucydides that “one must bear courageously what comes from one's enemies.” But such words, he said, were “cheap casings,” which Palladius would recognize if he studied Christian truth.2 As a bishop, Theodoret was well placed to mediate patronage. To the soldier and philosopher he offered both spiritual guidance and judicial advocacy. These letters cannot tell us if Theodoret's client won his case, but they reveal methods and strategies employed on his behalf. Through these letters Theodoret had to cast a good light on his clients, his contacts, and himself. Even in this simple scenario he had to manage several relationships and to pursue multiple goals.

This chapter looks at the process of mediating patronage: the methods by which Theodoret sought favors, established relationships, and created community. As we noted in the introduction, Theodoret's written appeals can be treated as social performances. Theodoret employed various theatrical techniques to present himself and his clients to selected audiences. He tried to win readers’ sympathy for his clients. To this end, he offered symbolic phrases and references that demonstrated common ground. At the same time, he tried to make favors look feasible and necessary. This he did with cues that distanced him from the audience and then invited actions to restore rapport. Theodoret had to coordinate some large coalitions, and to manage relationships for the long term. He also had to deal with the chance of failure—a negative audience response. Theodoret's patronage letters are hardly sui generis, but when compared to other late Roman collections, they feature some distinctive performance techniques.

Theodoret performed to win clients immediate favors, but he also aimed at long-term social goals, above all elite inclusion. Theodoret's patronage might seem unrelated to his doctrinal contentions. In fact, the two pursuits were intertwined. During the Nestorian controversy, he augmented his elite network. He courted neutral officials and onetime opponents as potential benefactors. During the Eutychean dispute, he lost many contacts, as foes challenged his theology and his behavior as a patron. His performances were insufficient defense against a hostile imperial court. Theodoret took advantage of an imperial transition to restore his social standing. By then, however, he was cast less as the patronage advocate than as the confessor, a more isolating role.

PATRONAGE EXCHANGE AND PATRONAGE

“PERFORMANCE”: TWO CASE STUDIES

FROM THEODORET'S LETTERS

Theodoret's letters have long served as a source for social history. Scholars have used the collection to investigate imperial administration, taxation, rural economic conditions, the fate of cities, and the development of the church.3 And they have scanned the letters for evidence of patronage exchange. Recent scholars have cautioned against positivist interpretations of patronage letters.4 Few, however, have looked closely at the social interactions revealed in written appeals. One way to explore these interactions is to treat them as performances, to use theatrical metaphors to illuminate the appeals process. Theatrical terms are an imperfect fit for written communication. They do, however, work well with the notion of networks, for advocates like Theodoret performed in order to pursue their larger social goals.

To explore the methodological issues raised by written appeals, consider two case studies. Twice in his extant collection Theodoret took up a larger patronage project, which required many coordinated appeals. The first project involved the settlement of refugees. In 439, Vandal forces completed their capture of Proconsular Africa. Many elite Romans fled for safer ground. By 443, some of these refugees had reached Syria. And Theodoret offered to help. He sent fleeing clerics to stay with his colleagues. He helped an orphan girl to search for her kin.5 He apparently gave one case special attention. The decurion Celestiacus had exhausted all his funds dragging his family to Cyrrhus, before asking help from God. “And I was struck with fear,” wrote the bishop, “for as is said in Scripture: I do not know what tomorrow may bring” (Proverbs 27:1).6

The case of Celestiacus (and other refugees) is intriguing for several reasons. It demonstrates the slight impact of Western Roman problems on the Eastern Empire. It reveals the significance of social rank across the Mediterranean. Theodoret's appeals show us people who might sympathize with an impoverished notable family, including bishops, sophists, decurions, and honorati. Above all, these letters showcase the rhetorical skills of Theodoret. For in various recommendations, he turned a desperate decurion into a philosopher, a devout Christian, and a paragon of gentility.7

Theodoret's second large patronage project concerned taxation. Between 445 and 447, the government was scheduled to perform the indiction census, the reassessment of each city's taxable assets (Latin: iugatio) that took place every fifteen years.8 After the previous census (430-432) the decurions of Cyrrhus had complained, along with those of other towns, that tax demands were unfair. In 435 the complaint was answered with a “visitation” (Greek: epopsia; Latin: peraequatio). The investigators would not lower Cyrrhus's total assessment, but reportedly they agreed to redistribute the burden between free holdings and imperial lands.9 Now, in the mid 440s, accounts would be reexamined, and potential disaster loomed. Someone in the capital was denouncing the decurions of Cyrrhus for falsifying their records. The perpetrator, we hear, was a deposed bishop, probably Athanasius of Perrha.10 If the bureaucrats believed this “enemy of Cyrrhus,” the town might be penalized. In 445 and 446, Theodoret met with local civic leaders to craft a response. They contacted allies and sent at least twelve letters. “Some [taxpayers] are living as beggars, while others run away,” Theodoret pleaded. “The shape of the city is reduced to one man, and he will not hold out, unless a remedy is applied.”11 The case of Cyrrhus's taxes has drawn attention from scholars. Theodoret's appeals constitute the best literary evidence for tax assessment in the fifth century. They paint a picture of economic trouble. Scholars have challenged this dark financial portrait.12 Still, this episode reveals intriguing facets of late Roman society, including the cooperation of clerics and curiales, the influence of officials and ex-officials, and the intersection of church affairs with imperial bureaucracy. Again the letters showcase the rhetoric of Theodoret, for the bishop knew when to cite numbers, when to decry injustice, when to recall past favors, and when to mention holy friends.13

These episodes represent the best-documented patronage efforts of Theodoret's career, but both dossiers have limitations as sources. The letters do not enumerate refugees in Syria or measure their condition. They present a partial account of Cyrrhus's taxable assets (in both senses of the term).14 Theodoret never tells us who, if anyone, hosted Celestiacus. He never clearly states if Cyrrhus had to pay penalties. Occasionally Libanius's collection hints at his success.15 Theodoret never records if favors were fully exchanged. The letters tell us more about late Roman culture. As Theodoret wrote, he used various tropes to construct social authority—to build a model of the proper patron. Theodoret's rhetorical constructions, however, vary greatly depending on who was involved. Theodoret's letters produce limited general information, because they are socially embedded; they were designed to send certain signals to specific people.

One way to account for the social facets of these appeals is to approach them as performances. Following recent sociologists, we may use theatrical metaphors to illuminate the transactional process.16 Whenever Theodoret wrote appeals, he assumed a stage persona. He directed an ensemble of clients and mediators. These “players” then tried to connect with an intended audience and inspire it to respond. Theodoret employed existing cultural elements as scripts in his performances. His troupe, however, usually had to improvise based on how audiences received them. Now any link in a social network, we have noted, may be viewed as a performance. Appeals for refugees, taxpayers, or criminal defendants are simply dramatic examples. Theatrical analogies do not capture every aspect of the patronage process. But they work well within a network-based perspective on society.17 For appeals are not just about winning favors; they are about forging relationships and building communities.

Theodoret's letters offer glimpses of a bishop using his office to stage appeals. They provide limited insight into the level of taxation or the plight of refugees. Rather they show us how an advocate made local taxpayers look sympathetic to administrators and refugees look appealing to hosts. Perhaps most importantly, the letters show us how Theodoret cast himself as a mediator and made himself look irreplaceable. As we shall see, this effort had implications for Theodoret's doctrinal pursuits and his social stature.

DEMONSTRATING COMMON GROUND

Requests for patronage are almost always plays for sympathy. And sympathy usually begins from a sense of common ground. Advocates must find connections between their clients and their contacts and present their clients accordingly. Theodoret had many ways to build a feeling of commonality. He might appeal to shared culture or religion. He might turn to mutual knowledge or experience. He could play to local pride or even Roman identity. Each time, Theodoret had to display the right terms and symbols to hide differences, and to bind participants as a single, if temporary, community.

Theodoret began his approach to performing appeals by accepting some realities of the late Roman social hierarchy. Most of the time, Theodoret wrote appeals to wealthy, educated audiences. So he discussed common features of elite Roman life (such as the role of pedagogues as familial enforcers).18 He also endorsed elite social perspectives; peasants, he wrote, were a “divine gift” to their landlords, a chance to show nobility.19 Theodoret wrote in the tones of panegyric, which Romans used to signal social status. He praised sophists for their “Attic” language and officials for their “gentleness.”20 He even turned praises into a source of common ground. To an honoratus he once recommended an orator who “pleases me all the more for being a warm lover of Your Magnificence. I contend with him in proclaiming your deeds and by my praises I am the conqueror.”21 Omnipresent in Theodoret's appeals were references to the role of patron. Theodoret knew that his contacts were “zealous to provide…favors.”22 All of these phrases pointed to the Roman social hierarchy, which served as a basic common ground.

Beyond the social context, Theodoret appealed to his audience by displaying cultural commonality. Not surprisingly, he often turned to Christian faith. Shared faith was a powerful motivator for generosity in the Christianizing Roman east. It presented an opening to rare audiences. “Since you…illuminate the purple by your faith,” he once wrote to Empress Pulcheria, “we are so bold as to write you a letter.”23 Evoking shared religion, however, was complicated, even dangerous. It could inspire grand favors and enduring loyalties or remind people of cultural conflict.

Sometimes Theodoret pointed to shared Christian teachings, a risky approach. Theodoret signaled doctrinal agreement with known allies. He mentioned “exact (akrib s) knowledge of divine matters” when he asked Anatolius to help with Cyrrhus's taxes.24 In semi-public writings, however, his words had to remain ambiguous. Outside his doctrinal party, even basic symbols were problematic; some powerful people still did not share the Nicene Creed.25 All he could discuss in these situations was “providence,” “God's mercy,” or other generalities.26 Theodoret also sought common ground in Christian moral teachings. Yet here, too, he faced challenges. Some Christians heeded tenets to give generously, while others hoarded wealth. Some “converted” to asceticism, while others sneered at monks. When Theodoret dealt with other clerics, he could point to requisites of office, such as the command to welcome visitors.27 When he dealt with other ascetics, he could point to their shared “toils of virtue.”28 But most of Theodoret's clients were neither monks nor clerics. So, again, he wrote ambiguously. He cited “philosophy” instead of asceticism. He spoke of exchanging “impiety” for “the wealth of faith.”29 Anything more specific would highlight differences rather than commonalities.

s) knowledge of divine matters” when he asked Anatolius to help with Cyrrhus's taxes.24 In semi-public writings, however, his words had to remain ambiguous. Outside his doctrinal party, even basic symbols were problematic; some powerful people still did not share the Nicene Creed.25 All he could discuss in these situations was “providence,” “God's mercy,” or other generalities.26 Theodoret also sought common ground in Christian moral teachings. Yet here, too, he faced challenges. Some Christians heeded tenets to give generously, while others hoarded wealth. Some “converted” to asceticism, while others sneered at monks. When Theodoret dealt with other clerics, he could point to requisites of office, such as the command to welcome visitors.27 When he dealt with other ascetics, he could point to their shared “toils of virtue.”28 But most of Theodoret's clients were neither monks nor clerics. So, again, he wrote ambiguously. He cited “philosophy” instead of asceticism. He spoke of exchanging “impiety” for “the wealth of faith.”29 Anything more specific would highlight differences rather than commonalities.

For a safer source of common ground, Theodoret turned to Christian Scripture. A well-chosen Biblical allusion could signal shared learning without causing offense.30 Theodoret could interweave countless quotations. One letter to an Armenian bishop went from Paul's praises of pastor Timothy (I Corinthians 4:17) to Jacob's care of his flocks (Genesis 31:38) to Ezekiel's attack on “bad shepherds” (Ezekiel 34:2) to Jesus's parable of the talents (Matthew 25:26-27), and so on for page after page.31 But his appeals were usually simpler. He asked correspondents to show to visitors “the kindliness of Abraham” (Genesis 18:1-15).32 He quoted obvious passages—“When one limb suffers, all limbs suffer with it” (I Corinthians 12:26)—to remind landowners and peasants what they shared.33 Even the words of Scripture had to be fitted to the audience.

Appeals based on Christian faith thus required careful scripting, lest they prove troublesome.34 So perhaps just as often, Theodoret turned to shared classical culture. For centuries the East Roman elite had treasured pre-Christian Greek literature. Pagans, Jews, and Christians studied with grammarians and sophists to maintain social standing. Whenever Theodoret dealt with pagans he turned to this corpus of learning.35 Even with many clerics, he returned to pre-Christian paideia.36 Theodoret cited the classics to showcase his learnedness, but also to signal shared values, such as humanity and self-control. Reliance on classical culture, however, brought its own dilemmas. Greek learning meant different things in different situations.

Sometimes Theodoret performed shared paideia through displays of literary knowledge. The right classical allusion could inspire generosity as readily as the Bible. Of course, not every Greek knew the same canon. Theodoret could plumb the depths of philosophy, as he did in his Treatment of Hellenic Maladies.37 His appeals were usually simpler. To Palladius the philosopher, he offered a Thucydides-style lament about the “shamelessness” of the present age (Historiae 2.53), then an unmarked quotation from Demosthenes, to “endure magnanimously whatever the god gives you” (De corona 97).38 If Theodoret chose a philosophic reference for an appeal, it was almost always Plato.39 More commonly, Theodoret turned to epic and tragedy. To one local official he referred to Euripides; fortune, he said, “has not wished to stay with the same people, but hastens to pass to others” (Troades 1204–6). And he asked one notable for the “Hospitality of Alcinous” (Odyssey 7),40 which nearly any Greek-speaker could understand.

At other times, Theodoret performed shared paideia through refined Greek language. This meant Attic grammar and rhetoric, which Roman educators taught as a mark of self-control. It also meant stock metaphors, which served as reminders for elite behavioral codes.41 Theodoret's appeals featured polysyndeton (emphasis via multiple adjectives), paronomasia (the naming of objects by their attributes), and other rhetorical figures. They included familiar comparisons to athletics, seafaring, and medicine.42 But not all linguistic tricks guaranteed a commonality of values. Some learned audiences expected a high style. Firmus met such expectations when he returned a borrowed hunting dog (named Helen) with a panegyric to canine beauty.43 Others expected the direct style of Libanius, which featured compelling visual scenes.44 Theodoret produced highly rhetorical sentences, when friends might expect them. Usually, to inspire generosity, he followed the direct visual style. Thus he vividly related the “tragic saga” of decurions and refugees.45

Christian faith and classical culture were rich sources of common ground. But some audiences required an additional approach, which recognized “broader” bonds of community. One such approach was to appeal to civic identity. Since the early empire, eastern Roman elites had championed the splendor and virtue of their home cities.46 Theodoret rallied notables of Cyrrhus to show some local pride and not to “diminish the city.”47 He appealed to residents of other towns by encouraging municipal competition. “If our city, which has but a few poor inhabitants, consoles the [refugees] who have arrived here,” he wrote to a nearby bishop, “how much more fitting it is for Beroea, raised in piety, to do so!”48 Another approach was to appeal to Roman identity. By the fourth century, nearly all imperial residents were citizens and potentially full Romans.49 Theodoret appealed to “shared” Roman history. When recommending refugees from North Africa, he recounted the last time Carthage had been conquered (in 146 B.C. by the Roman Republic).50 Theodoret also acknowledged the importance of Roman political boundaries. When he spoke of “Syrians,” “Cilicians,” or “Easterners,” he was not spouting separatism but affirming governmental jurisdictions (and the authority of those who drew them).51 Theodoret celebrated Roman virtues, which he contrasted with the Persians’ supposedly scandalous ways.52 He also used well-worn Roman stereotypes of freeborn citizens and slaves.53 These appeals to Roman or civic identity might seem hopelessly broad, like appealing to common humanity, but they were multivalent enough to reinforce both classical culture and Christian faith. And they were vague enough to work where culture or faith might offend.

Neither paideia, nor Christian faith, neither local pride, nor Roman identity, could guarantee connections between clients and contacts. Every appeal required a fresh performance, suited to the audience and the situation. Sometimes the resulting piece was straightforward. Such was the case when Theodoret wrote the sophist Aerius to recommend refugees. He compared the fleeing Africans to Athenians imprisoned in Sicily in the 410s B.C. (Thucydides, Historiae 7.82–87). He described “tempests” and “shipwrecks” and again asked for the “hospitality of Alcinous.”54 His request was simple; his contact's preferences, familiar. So he went with classical allusions.

Other situations required more elaborate displays of commonality. Such was the case when Theodoret pleaded for a taxpayer to Constantine, the former prefect. He started with vaguely Christian philosophy. “The God of the Universe established the nature of humans by his Word (log i)” he wrote. “Because of this, human nature figures out what it needs of its own accord.” Then he praised paideia, which, if used selectively, augmented nature with “admirable art-pieces of virtue.” Theodoret compared philosophers and writers to bees. He praised the prefect for his “rationality” (logon), which allowed him to swim the sea of passions and navigate a political life. To introduce his client, Theodoret offered this rhetorical flourish: “I beg that you take joy in your solicitude for the illustrious and most amazing Dionysius, who holds a position of leadership against his will, cohabiting with poverty, maintaining a modest and wise way of life, pressed for funds which he could not give over even if he were to become a slave instead of a free man.” He offered no details but claimed that the “tragic tale” would move anyone to sympathy, especially a compassionate former prefect. By the end, he had interwoven philosophy with Christian theology. He had linked the troubles of political leadership to the burdens of servitude.55 The favor he asked was probably annoying. So he bathed his request in shared experience, status, paideia, and faith.

i)” he wrote. “Because of this, human nature figures out what it needs of its own accord.” Then he praised paideia, which, if used selectively, augmented nature with “admirable art-pieces of virtue.” Theodoret compared philosophers and writers to bees. He praised the prefect for his “rationality” (logon), which allowed him to swim the sea of passions and navigate a political life. To introduce his client, Theodoret offered this rhetorical flourish: “I beg that you take joy in your solicitude for the illustrious and most amazing Dionysius, who holds a position of leadership against his will, cohabiting with poverty, maintaining a modest and wise way of life, pressed for funds which he could not give over even if he were to become a slave instead of a free man.” He offered no details but claimed that the “tragic tale” would move anyone to sympathy, especially a compassionate former prefect. By the end, he had interwoven philosophy with Christian theology. He had linked the troubles of political leadership to the burdens of servitude.55 The favor he asked was probably annoying. So he bathed his request in shared experience, status, paideia, and faith.

Performances of common ground thus required considerable tailoring. They also required clever ambiguity. Theodoret had to choose the right elements of shared culture and experience. The sense of commonality had to be specific enough to create sympathy but vague enough to hide cultural differences. Sometimes Theodoret could simply state all the memberships shared by his clients and contacts. Mostly, he relied on symbols open to multiple interpretations. When he wrote about “mimicking the bee,” he might mean a full Attic education, or the selective learning once advised by Basil.56 When he mentioned “philosophy” he might mean asceticism or intellectual debate. The right ambiguity could bridge divides. The refugee Celestiacus was neither a master of paideia nor a committed cleric. But Theodoret could still commend him to sophists for his noble virtue, and to bishops for his “wealth of faith.”57

Ultimately, every demonstration of common ground was an attempt to define a sense of community. Allusions and rhetoric were useless unless they bound performers to audience members. Theodoret did build on social similarities, but the challenge was to encourage moral identification. Luckily, Theodoret was there to demonstrate the right course. He performed the commonality that he was seeking, by writing.

MARKING SOCIAL DISTANCE

Theodoret's performance of appeals displayed common ground, but shared culture or experience was rarely enough to get audiences to respond. A mediator like Theodoret was only needed when something separated the generous from the needy. Advocates, therefore, had to point out the differences that necessitated their involvement. And they had to position themselves as honest brokers, who shared enough with clients, and enough with would-be patrons, to bridge the divide. Theodoret found many ways to stage social and cultural divisions. He used these techniques to position himself as a concerned outsider. He used the same techniques to create rhetorical foils—divisions that would be overcome if the audience properly responded.

Theodoret began most appeals by distinguishing his clients, usually by describing their plight. When advocating for peasants, for instance, he emphasized the disparity between them and their landlords. Some tenant farmers may have been nearly self-sufficient, but in appeals they were cast as perpetual suppliants. They were also presented collectively, without names.58 When advocating for notables, Theodoret stressed their descent into deprivation. Refugees “who once decorated [Carthage's] famous curia,” he wrote, “now wander all over the world, getting from the hands of strangers the means of survival.” Taxpaying estates near Cyrrhus were now supposedly “abandoned by their owners.”59 Appeals, it seems, required casting clients in lowly roles.

Theodoret appeals also set his clients apart by showing what they had to offer. Theodoret recommended refugees as props for preaching. “Some people [God] punishes,” Theodoret wrote to a colleague, “others He teaches by the punishments of [those who have suffered]”—a lesson suitable for any Christian congregation.60 He also promised less tangible benefits. It was “the poor,” he said, who made good “advocates” before the “frightful [heavenly] tribunal.”61

Theodoret stressed such distinctions to make patronage relations seem necessary and profitable. This was mostly a prelude, however, to his casting himself in the role of trustworthy mediator. This role required a sense of connection to clients and contacts. It also required a sense of separation from the interests of either side. Thoeodoret showed himself ready for this role by highlighting his episcopal office. In some appeals, he directly noted how “God ordered that…[he] shepherd souls.”62 In others, he chose an indirect tack. When he castigated a former bishop for actions “unworthy of manual laborers,” “slaves” or (ironically) “stage actors,” he revealed by contrast his own professional virtue.63 Sometimes Theodoret suggested that his appeals required a bishop like himself. The holy man Jacob of Cyrrhestica, we are told, wanted to defend the taxpayers, but he “holds silence in such regard that he cannot be convinced to write.”64 In other words, Jacob needed a trusted spokesperson, namely the bishop of Cyrrhus.

Theodoret also distinguished himself by displaying his learnedness and his strict lifestyle. He never bragged about his education, but he revealed his scriptural skills in allusion-rich sermons and occasionally in appeals.65 He displayed his classical learning even more rarely.66 Occasionally he spoke of “poets, orators, and philosophers,” although he swore that “the sacred writings suffice.”67 Theodoret hinted at his ascetic lifestyle by denigrating the present world. But he rarely made direct mention of his personal regimen (he did so more often when fending off charges of heresy).68 For him, the role of bishop required a humble persona. So personal qualifications had to be demonstrated indirectly.

Marking social distance thus helped to set the scene within Theodoret's appeals. The same basic techniques supported his most distinctive tactic: the staging of foils. By foils, I mean performance elements that create a temporary distance, but which are then used to inspire renewed commonality in the longer term. Like many advocates, Theodoret presented vice, or vicious people, as foils, evoking the morality that most people supposedly shared. By decrying the “hatred” and “lies” of his foe in the tax-fraud case, he signaled the rectitude of nearly everyone else.69 More surprisingly, Theodoret often distanced himself from his actual target audience, in order to invite them to join in a deeper connection. Consider his reply to a notable who had sent a gift of wine from Lesbos. Theodoret praised the “clarity of [the wine's] appearance,” in accord with elite conventions. But then he redirected. “For me, this wine is totally useless if indeed, as you say, it makes the drinker long-lived; for I am no lover of long life,” he wrote, “since the waves of this life are numerous and troublesome.”70 Thus high-class finery served as a foil for a Stoic mindset, which he hoped his correspondent would embrace.

Theodoret staged various foils in his appeals. Sometimes he used classical culture as a foil for encouraging Christian faith. When recommending refugees to a sophist, he celebrated paideia, then shifted to the mystery “which words cannot fathom, nor the mind comprehend.”71 At other times Theodoret used customs of panegyric as a foil for building faith. Hoping to baptize the courtier Zeno, he praised the general's mix of “courage, gentleness, and softness,” which amounted to a “wealth of virtue.” But this, he wrote, paled in comparison to the “garb that is indescribable and divine.”72 Theodoret's rhetorical pieces could be obvious. Appealing for Cyrrhus's taxpayers, he jokingly asked Anatolius, “Why have you shown hate to those that love you?” before shifting back to panegyric.73 Or his pieces could be almost satirical, such as when a governor wanted to attend a festival and Theodoret hoped to keep him away. “The Hideous She-Monster (morm ) is a fright to children, as are the pedagogues and teachers to young boys,” Theodoret began, “the biggest fear for high-born men is the judge…and the collection of dues. Yet the fear of these…is doubled for those in poverty.” Normally a bishop would labor mightily, he said, “so that you may partake of the festive assembly, decorate the city [with your presence] and play chorus-leader.” But the citizens were afraid of the governor's “mask of authority” (arch

) is a fright to children, as are the pedagogues and teachers to young boys,” Theodoret began, “the biggest fear for high-born men is the judge…and the collection of dues. Yet the fear of these…is doubled for those in poverty.” Normally a bishop would labor mightily, he said, “so that you may partake of the festive assembly, decorate the city [with your presence] and play chorus-leader.” But the citizens were afraid of the governor's “mask of authority” (arch s pros

s pros peion). Besides, he wrote, “even in being absent, you will be associated with the festive assembly, honoring the apostles and prophets by your rest and truce.”74 Here elite experiences served as a foil for shared faith. Thus Theodoret protected his congregants by writing a disinvitation.

peion). Besides, he wrote, “even in being absent, you will be associated with the festive assembly, honoring the apostles and prophets by your rest and truce.”74 Here elite experiences served as a foil for shared faith. Thus Theodoret protected his congregants by writing a disinvitation.

Foils were not unique to Theodoret,75 but they were important to his appeals because they created a moral tension that the audience was empowered to resolve. Theodoret created tension when he described the sufferings of refugees. He added to it when he shamed clerics for their lackluster charity, or when he told sophists to “prove the utility of fancy words.”76 Theodoret created tension when he noted the deprivations of taxpayers. He augmented it by describing their informant as a hate-filled denouncer. In each case, Theodoret offered his audience a way to relieve the tension. By defending taxpayers, they could align themselves with the forces of righteousness. By helping refugees, they could share in divine mercy.

Displays of distance were as central to Theodoret's social performance as displays of commonality. An effective mediator had to do more than find some shared virtue. He had to position himself to bridge social gaps and to motivate people to reach across divides. Different situations called for different acts of repositioning. Sometimes Theodoret distanced himself from the audience while embracing his clients. Sometimes, he separated from clients while embracing the audience. Other advocates had their own formulas for signaling distance and commonality.77 Theodoret usually sought a balance, sharing just enough with clients and with providers to mediate between them.

DIRECTING ENSEMBLES

Advocates performed complicated maneuvers to motivate generosity. But appeals were never solo performances. Nearly every late Roman letter involved letter-bearers and observers. Large-scale appeals featured agents performing before multiple audiences. Somehow advocates had to direct these ensembles of performers and texts. Theodoret took up this task when defending taxpayers and when pleading for refugees, as well as in simpler scenarios. Each situation called for its own directorial approach.

When preparing appeals, Theodoret's first consideration had to be the coalition of participants. Each problem afflicted specific clients, seeking help from some set of patrons. In every situation, Theodoret considered whom to employ as agents and brokers, before which audiences. He also decided which opposing forces had to be overcome. For every appeal Theodoret chose envoys to fit with the message and its intended recipients. But it was Theodoret's grand appeals that demanded the most stage-direction. His approaches to the two extant cases differed as sharply as the problems themselves.

With refugees, Theodoret faced a straightforward, if difficult, situation. Letters record five parties who asked him for assistance: two bishops, a young woman, a notable layman, and the household of Celestiacus. The parties’ needs varied from clerical employment to familial reunion. But all sought hospitality and new elite connections. Refugee relief did not require a particular provider. Indifference was the only opposing force. Indifference, however, might be enough to hinder help.

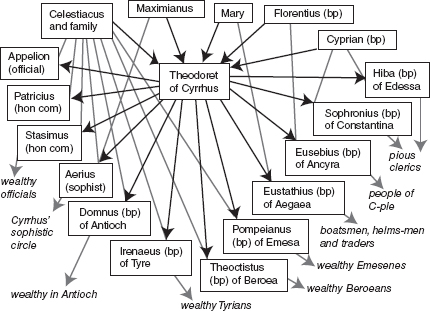

To aid the refugees, Theodoret assembled a cast of advocates, each with a target demographic. For starters, he drew in bishops from his doctrinal party, including Domnus of Antioch (ep. S 31), Hiba of Edessa (ep. S 52), and Irenaeus of Tyre (ep. S 35).78 He also tapped a miaphysite bishop (Eusebius of Ancyra, ep. P 22), who had already sent a refugee to Syria.79 Theodoret relied on his colleagues’ preaching to motivate local notables. He relied on their connections to facilitate travel. Most of all he relied on their geographical scatter to maximize his audience. In addition to bishops, Theodoret tapped an official and two honorati. Their status gave them access to “those in wealth and office,” even those who avoided sermons.80 He also tapped the sophist Aerius (epp. P 23, S 30), whose eloquent circle might reach people uninterested in the faith. No precise sequence is apparent in these letters. None was required. The goal of this troupe was to reach the widest set of potential hosts across the segments of late Roman society.81

FIGURE 18. Theodoret's patronage ensemble: African refugees, 442–444, according to his letters. Black arrows = direct appeals, grey arrows/lines = indirect links/appeals, bp = bishop, hon com = honorary count.

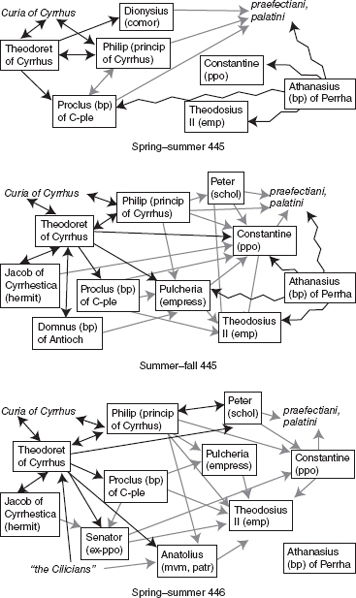

With Cyrrhus's tax woes, Theodoret faced a more complicated situation. As we noted, Cyrrhus had had its assessment last adjusted in 435. The city council sought to confirm this assessment with the administration. Constantinopolitan bureaucrats kept records of assessments (the praefectiani for free holdings, the palatini for imperial lands). Their “field agents” (tractatores and rationales) inspected accounts that were in arrears. Any of these men could influence the calculations, as could their superiors, the prefect of the East and the count of the Res privata.82 The emperor could impose his will, if he was paying attention. In fact, any courtier could influence the process. Somehow Theodoret had to find out which figures were influential and win them over via agents and letters. Meanwhile, Cyrrhus faced an active opponent, who claimed that the city council had falsified its assessment. Somehow Theodoret had to neutralize this “denouncer.” Thus Cyrrhus needed many advocates and supporters, and a coordinated plan.

To protect Cyrrhus's taxpayers Theodoret progressively built his coalition with a sequence of appeals that can be reconstructed.83 Theodoret and his local allies began in mid-445 by dealing with the central bureaucracy. Having heard something of the problem, the city sent Philip the principalis to Constantinople, to the offices of the prefecture and the Res privata. Theodoret paved the way with a recommendation to Bishop Proclus. Once in the capital, Philip probably learned in detail about the accusations. But his meeting with the bureaucrats was clearly insufficient to counter them. He reported to Theodoret, who asked the count of the East to delay extra collections (ep. P 17). Later in 445, Theodoret began a second act before an audience of higher authorities. He asked the help of Jacob of Cyrrhestica, the “friend of God,” whose name he dropped repeatedly.84 Then he sent a new envoy to the capital to meet with Philip (and Proclus, ep. P 20). They delivered letters to Constantine, the prefect of the East (ep. S 42), and Empress Pulcheria (ep. S 43). They also hired a lawyer (Peter) to speak on Cyrrhus's behalf.85 These appeals had more success. Cyrrhus was to be assessed by the old formula; Philip's entourage came home.

The antagonist, however, continued to accuse Cyrrhus of tax fraud. He made enough headway at court that Theodoret had to initiate a third act. Philip returned to Constantinople in the summer of 446, to reengage with Peter (ep. S 46) and Proclus (ep. S 47). And he delivered new appeals to courtiers, including Senator, the prefect during the last reassessment (ep. S 44), and Anatolius, the familiar general (ep. S 45). The final outcome is not known, but at each point in the drama Theodoret had a plan. Each wave of appeals built on the last. Each employed the existing cast while reaching for new members. Each targeted a new audience of decision-makers, surrounding them with advocates and texts. The goal was to inspire favorable talk, from the bureaucrats up to the courtiers, which could hold the accusations at bay.86

Theodoret worked hard to stage-manage patronage troupes such as these. But even when he did simpler appeals for clients, he had to deal with the larger social context. First, he had to fit with prior interactions with his audience. Consider his appeals to Areobindus, the wealthy general who owned estates near Cyrrhus. Tenants of Areobindus had trouble paying the rent (in this case, olive oil) when harvests were poor. They repeatedly asked Theodoret to plead for reductions. One time, Theodoret fulfilled this request with a standard appeal; the “divine gift of peasant laborers” had given the landlord a chance to show his generosity.87 When he wrote a second appeal, he began similarly. Again, the bishop said, God made poverty as a “means of usefulness;” he had given further “opportunities to the well-off for showing generosity.” But this time the performance included more symbolism. Instead of oil the peasants brought a “suppliant's olive branch,” the bishop's letter. Areobindus could then turn a bad harvest into “spiritual abundance.”88 Thus Theodoret played off prior patronage to create an expanded storyline. And he built a connection progressively across multiple appeals.89

FIGURE 19. Theodoret's patronage ensemble: Cyrrhus's taxes, 445–446, according to his letters. bp = bishop, comor=count of the East, emp = emperor, patr = patrician, ppo = praetorian prefect of the East, princip = principalis, schol = scholasticus.

Beyond individual relationships, Theodoret had to consider the wider community of mediators and patrons. Theodoret's partners in advocacy were interlinked. Consider Eurycianus the tribune. In 434, Eurycianus delivered letters from Titus the general, warning Theodoret that schismatic bishops might be deposed. Later he received a consolation letter from Theodoret.90 Like Theodoret, he was friendly with the sophist Isocasius, who once sent him to Cyrrhus in search of a good woodcarver. He probably also knew Philip the principalis through either the sophist or the bishop (or both).91 Theodoret included men like these in his ensembles, and he had to consider the interconnections.92 After all, anything he wrote or said could be passed around.

In fact, Theodoret had to consider not just people, but texts—the way letters presented his associates and himself. Most appeals were publicized. Not only were they read aloud;93 if granted they were commemorated in ceremony and perhaps in stone.94 Appeals could also be reused for new purposes. Thus Theodoret wrote for Palladius and his hired soldier, then used the same text to encourage Palladius's faith.95 Appeals, like all letters, were collected. Clients assembled multiple appeals to deepen their sense of protection.96 Advocates assembled appeals, probably to display their record as mediators.

Whenever Theodoret directed ensembles, he sought to represent his clients and contacts as part of an attractive, face-to-face community. His letters introduced clients and contacts, agents and brokers, friends and providers. The written texts introduced supporters who could not participate directly. If Theodoret succeeded, his appeals would follow one another to create decades-long sagas of favor and loyalty.

MANAGING THE RISK OF FAILURE

Theodoret's appeals were ambitious productions. Each was a gamble that contacts would respond to the right advocates at the right time. Friendships and patronage links could endure a few misconnections, but repeated performance failures endangered these bonds. “Do not ask for great things,” Synesius once opined; “Either you may wound another or you may be wounded.”97 Every time Theodoret performed appeals, he tried to minimize the risk of refusal. Or he tried to lessen the consequences. He managed expectations in appeals by claiming inferiority. He excused ambitious requests by claiming a spiritual motive. He avoided risky tactics and sometimes refused to get involved. Thus Theodoret worked to maintain social links even when his requests failed.

Theodoret's prime method for dealing with the chance of failure was to stress his own inferiority. He declared his lack of stature to the political elite. “If I sent a letter to Your Greatness with no imposing necessity,” he wrote to one prefect, “I would have likely been found guilty of presumption;” for then he would seem “ignorant of the magnitude of your authority.”98 Theodoret also stressed his lowliness to near-equals. Writing to sophists, he called himself inarticulate. Writing to archimandrites he dubbed himself “lazy.” Even his own subordinate clerics he called “friends.”99 This practice of written self-deprecation was common among Christian ascetics.100 But in the Roman elite it was far from universal. Bishop Firmus approached some courtiers as their philos. Libanius even rebuked some officials who were not proving helpful.101 But Theodoret saw the value of playing down his capacities. By declaring his weakness, Theodoret accentuated the stature of his audience. He gave those providers a clear role to play while stressing their agency. Theodoret also minimized the chance of conflict. With near-equals he reduced the sense of rivalry. With superiors he reduced the appearance of presumption. All of this helped to preserve relations with contacts, so that he could appeal again without risking offense.

Theodoret's second method for dealing with failure was to stress his unassailable Christian motives. Sometimes he explained his advocacy as a pious duty. “After God ordered that, despite my unworthiness, I shepherd souls,” he began one appeal, “I often must take care of things that are troublesome for me but advantageous for my sins.”102 His message was clear: making unlikely requests was part of the clerical life. Sometimes Theodoret claimed that appeals were really acts of pastoral care. His contacts, he hoped, would show “generosity,” because they “longed to receive the same from God.”103 He knew that many appeals would get no immediate audience response, but if done for higher purposes, these performances were not really failures.

A third method for limiting dangers was to avoid risky settings for appeals. Theodoret preferred contacts whom he already knew. A doctrinal ally (such as Domnus or Anatolius) could always be asked to help with refugee settlement, taxes, or legal cases. But even a onetime opponent (such as Eusebius of Ancyra or Titus the general) was better than a stranger.104 Theodoret also preferred familiar institutional scenes. He knew the habits of the clergy and the civil bureaucracy. He was less familiar with military life. This may be why he defended Palladius's soldier at Titus's tribunal, rather than that of a lower officer.105 Theodoret sent his appeals in Greek, even to speakers of Latin or Syriac. He left the risk of translation to his recipients. Perhaps most striking, Theodoret chose to avoid the emperor. Once he had directly “persuaded” Theodosius II. Yet none of his later extant letters addressed the Augustus.106 To petition the emperor was to risk a final denial, and that might endanger his entire patronage network.

Finally, Theodoret could avoid the risk of failure by refusing to perform appeals. Refusal was hardly his declared preference, but there were some unsupportable causes and unsupportable people. Theodoret's letters include one outright refusal, when Apelles, a Constantinople lawyer, asked for help for a friend. “I am not ignorant of human nature, nor do I bear humanity, of which I have great need, with an ill grace,” Theodoret began. “Indeed, I know to provide for friends when they ask it, since I wish to receive [help] when I need it.” But this request went out of bounds: “I wish to ask and be asked for things that do not cause great outrage.” Theodoret never specified what was objectionable. Maybe Apelles’ friend was heterodox (the letter calls him an “instrument of the opposing power.”) Theodoret was upset, to “suffer the reputation that [he] heard insensitively.”107 But reticence and refusal might have protected everyone involved.

In dealing with the dangers of failed performances, Theodoret sought to preserve relationships. Even when refusing Apelles, he emphasized the goodwill between them. Theodoret's bonds with clients and many friends relied on a record of favor distribution. Protecting these relationships meant projecting that record into the future. The best outcome for advocacy was usually a successful transaction. But the loss of an appeal need not spell disaster, so long as his performances promised favors to come.

STRATEGIES OF INCLUSION: THE BUILDING

OF A PATRONAGE NETWORK

Theodoret's letters thus showcase methods that he employed to perform patronage appeals. For each situation, he selected a mix of tactics to secure favors (or the hope of favors at a later time). Patronage, however, meant more than momentary theatrics. Viewed together, Theodoret's letters reveal deeper social strategies. We have seen how Theodoret worked in the 430s and 440s to grow and solidify his doctrinal alliance. During the same decades, he tried to assemble a patronage network. He sought to accumulate clients, to build elite relationships, and to achieve a sense of inclusion. The appeals examined so far in this chapter appear unrelated to theological debate, but patronage performances were, in fact, linked to the Christological conflict. It was the dispute over Nestorius that gave Theodoret the chance to perform grand appeals. And it was Theodoret's patronage performance that supported his leadership of the Antiochenes.

Theodoret's social strategies aimed to accumulate relationships, and patronage performances proved essential in this regard. In chapter 1, we saw some of the ways in which Theodoret fostered friendships with fellow clerics. Outside the clergy, his friendly links extended to people who shared his curial background, his ascetic habits, his learning, or his faith. Theodoret's appeals may or may not have won clients material favors. Either way, they allowed him to cooperate with all sorts of locals: priests, monks, professionals, curiales, notable women, bureaucrats, soldiers, and honorati. They also enabled him to interact with elites that otherwise might be inaccessible: senators, generals, courtiers, empresses, clerical foes, and unfamiliar colleagues. Both locally and across the elite, appeals provided the chance to promise mutual benefit.

Beyond the accumulation of relationships, Theodoret's strategies aimed to achieve a sense of social inclusion. Once again, patronage performances proved essential. We have noted how late Roman Syria was segmented socially and culturally. We have seen how Theodoret connected with multiple subcultures and social spheres. But he was not satisfied with serving as the link to outsiders. He strove to give disparate people a sense of connectedness, and patronage provided the opportunity. In his appeals he cast clients alongside advocates and one another and represented them favorably to elite audiences. He showcased differences of geography, culture, and social rank, and then invited audiences to bridge those gaps. The crucial aspect of these performances remained the role of mediator. Inevitably Theodoret presented himself as the man who could bring together officials with subjects, landlords with tenants, academics with clerics, (former) pagans with Christians, and everyone within the church.108 Naturally, Theodoret was concerned with his own place in the community. Relations with clients mattered to Theodoret. But these letters were less about extracting loyalty from clients than about auditioning for an elite circle of friends.

Theodoret assembled patronage contacts throughout his career, in a fashion that at first seems unconnected with doctrinal debate. A closer look, however, reveals links between Theodoret's patronage activity and the Christological dispute. We have seen how Theodoret bonded with his clerical associates via friendship and doctrinal affinity. We have also seen how doctrinal allies were drafted as fellow mediators of patronage.109 Such cooperation was probably old news in 430. It was never limited just to those within the Antiochene fold. But the process of schism and reconciliation seems to have encouraged Antiochenes to share in efforts at appeal.110 In any case, the Nestorian controversy did boost Theodoret's connections with figures of real power: not just allies but also former foes. Theodoret probably already knew Anatolius from Antioch. But protection arrangements after the First Council of Ephesus cemented this relationship.111 Theodoret may or may not have known Dometianus the quaestor, Eurycianus the tribune, Antiochus the prefect, and Titus the general before they acted to oppose the Antiochenes. By 434, all were receiving his recommendations, reading his judicial briefs, asking his advice, or serving as his envoys.112 Travels to Ephesus and Chalcedon in 431 introduced Theodoret to courtiers such as Senator, Florentius, and Taurus. All later received the bishop's appeals.113 Proclus the layman had denounced Nestorius, but as bishop he became Theodoret's perennial partner. Even Empress Pulcheria, who had shown hostility to Nestorius, was courted for the financial support of allied monasteries114 and the protection of taxpayers. It is not clear how much Theodoret served as a high-level advocate before the First Council of Ephesus; few of his letters from the 420s remain. Still, controversy clearly taught Theodoret more about the power elite. It seems unlikely that he could have hoped for favors from all these contacts without the Nestorian conflict.

However Theodoret found his elite contacts, his letters suggest that he achieved a certain kind of success. In this case success meant not a vast record of favors delivered, but a compelling, multi-front performance. Clients had to believe that Theodoret held close connections to people who could secure benefits. Elite audiences had to be persuaded that he managed a broad clientele. Partners in patronage had to be convinced of both his base of clients and his list of friends. And everyone had to trust that he was mediating responsibly, to the benefit of all involved. Theodoret's role as Antiochene leader was part of this dynamic. Clerical leadership enhanced his quest for patronage contacts by projecting a picture of broad social support. Patronage contacts enhanced his claim to clerical leadership, by projecting a picture of elite access. We have noted how Theodoret won protection during the Nestorian crisis. We have also noted how he led the Antiochenes to defend the name of Theodore in the face of opposition. Patronage links may have contributed to Theodoret's capacity to maintain the Antiochenes’ protection, and loyalty, right up to 448. Thus he could make headway with all his social strategies, so long as he played mediator and seemed irreplaceable.

STRATEGIES OF PERSEVERANCE: PATRONAGE

AND THE EUTYCHEAN CONTROVERSY

Theodoret's patronage appeals were both singular performance pieces and part of a larger strategy: to act his way to the heart of multiple social networks. Playing advocate, however, did not work in every circumstance, amid doctrinal conflict. Theodoret gained stature as both a clerical leader and a mediator of patronage during the dispute over Nestorius. The next confrontation went differently. The Eutychean controversy forced Theodoret to defend both his record of patronage and his orthodoxy. He could not maintain his social position in the face of accusations and a hostile court. Theodoret took advantage of the imperial transition to restore some contacts. But it is unclear how much he rebuilt, once he had been forced to play roles other than mediator.

The accusations that Theodoret and his allies faced in 448 and 449 provide a vivid illustration of how intertwined the role of clerical leader was with that of patronage mediator. In chapter 5, we noted the list of Theodoret's foes during the Eutychean controversy. Some of these figures had already challenged doctrines of the Antiochenes. Others held unknown theological views but were somehow sidelined by Theodoret's network. One such foe was Athanasius of Perrha, probably the cleric who accused Cyrrhus of tax fraud.115 Theodoret and his allies were eventually fingered as Nestorian heretics, as we have seen. But that is not how opponents began their attacks. First, Irenaeus of Tyre was accused of mismanagement, personal impropriety, and defiance of imperial authority. Then Hiba was charged with gross nepotism and misappropriation of finances to fancy buildings rather than the worthy poor. In the spring of 448, Theodoret was accused of neglecting his flock while conspiring to tyrannize other dioceses.116 All three, in other words, were being labeled as irresponsible patrons.

Before Theodoret knew of any doctrinal attacks, he defended his reputation as a patron. “When did we ever act offensively about anything to His Serenity [the emperor], or the high officials?” he asked Anatolius. “When were we ever obnoxious to the many illustrious landowners here?” Rather, the bishop claimed, he had “lavishly spent much of [his] church revenues on public works, building stoas and baths, repairing bridges and caring for the common needs.”117 Writing to Nomus the Consul, Theodoret further described his career. “Before I was bishop, I lived in a monastery, and then I was consecrated against my will; in my twenty-five years as bishop,” he wrote, “I was neither brought to trial by anyone, nor did I accuse anyone. Not one of my pious clergymen ever approached a court.” Meanwhile, Theodoret asserted his value as a collaborator. “No one informs you of the size of the dangers,” he declared—no one except for him.118

As Theodoret defended his reputation and then his teachings, he used performance techniques that served him in appeals. By late 448 he had written apologies to most of his (known) patronage contacts, from prefects and patricians to archimandrites and bishops. Each time, he sought common ground. To Anatolius he sent reminders of the long mutual record of protection and loyalty.119 With less familiar courtiers, he appealed to fairness: “If someone persists in accusing me of teaching something alien,” he wrote, “let him argue it to my face.”120 Theodoret tried to position himself as a “prominent teacher of evangelic dogmas.”121 He touted his willingness to hold communion with accusers and to mediate secondary disputes. Theodoret built his coalition carefully. First he consulted with close allies, such as Domnus of Antioch.122 From mid- to late 448 he wrote to familiar courtiers including Anatolius (epp. S 79, 92), Eutrechius (epp. S 80, 91), Nomus (epp. S 81, 96), Taurus (epp. S 88, 93), Antiochus (ep. S 105), Florentius (ep. S 89), and Senator (ep. S 93).123 He hired a lawyer (Eusebius) to present oral arguments.124 And he sent Basil of Seleucia to the capital to survey the clerical scene (ep. S 85). In the winter of 448–449 he and Domnus coordinated their embassy to the court, with the help of Basil, Flavian of Constantinople, Anatolius, several lower clerics, and several notable women.125 Their aim was to surround the court with an unignorable chorus of appeals. Theodoret tried to avoid causing offense; he spoke of the “boundaries” that he would never violate except out of desperation. He showed self-deprecation and defended his motives. “We have been guilty of many other sins,” he told a prefect, but “right up to today we have kept the apostolic faith untainted.”126 His best argument was probably that of Basil of Caesarea: innocence by association. “I think your Piety is well aware that Cyril of blessed memory often wrote to me,” he wrote to Dioscorus, recalling the kindnesses that they had traded.127 Thus Theodoret acted as his own advocate to maintain inclusion in the circle of orthodox friends.

Theodoret's appeals performance, however, confronted the limitations of his situation, under rhetorical assault and facing court hostility. For starters, his efforts were limited by his physical circumstance, relegated to the territory of Cyrrhus. Opponents denounced him in person in the capital; he could respond only in writing. Opponents mixed nefarious rumors with exaggerated doctrinal accusations. All he could do was deny the “slanders of his denouncers”—the sort of denials that might actually sustain suspicions.128 The bishop's foes also isolated Theodoret from most of his patronage contacts. By late 448, he was shocked to have his letters go unanswered. He could not even get the urban prefect Eutrechius to share intelligence or to announce that the bishop was protesting accusations.129 The reason for this silent treatment was the now obvious anti-Theodoret leanings of the imperial court.130 No clever performance could win much public sympathy once the emperor had signaled his displeasure.

Meanwhile Theodoret was forced to change his whole mode of performance. As foes denounced his heresy to receptive imperial audiences, Theodoret left the role of advocate for that of confessor. Before the council in 449, he started truth-telling to his remaining allies. He warned Domnus of the synod's impending doom. He wrote snidely to Anatolius about the “most righteous judges at Ephesus,” and declared himself ready for exile.131 Once condemned, Theodoret deepened his prophetic performance. With loyal allies he traded denunciations of the church's “general apostasy.” He reveled in shared suffering and promised secret refutations.132 When lay notables wrote in sympathy, he responded bluntly. “In no great length of time, those who dared these deeds will pay the penalty,” he wrote to Maranas the lawyer, “For the Lord of the Universe governs all things with a weight and a measure.”133 As Theodoret prepared for exile, he wrapped up old patronage operations. Professionals, whom the bishop had enticed to Cyrrhus, joined him in leaving town.134 The bishop had not lost all of his elite favor. With Anatolius's help, he successfully asked to be exiled to Nicertae.135 But even in this appeal Theodoret was not begging for mercy; he was waiting for divine vindication.

In late 449, Theodoret put his performance skills to work on one more apologia, to Pope Leo and his coterie. First, Theodoret wrote a long appeal directly to Leo. “If Paul…ran to the great Peter to get from him a solution to the problems of those in Antioch who were arguing about living according to the [Jewish] Law (Galatians 2.11–14),” he began, “ all the more do we, humble and small, run to your apostolic see to get a remedy for the church's wounds.” With this clever twist on Scripture, he signaled both shared Christian knowledge and deference to Leo's authority.136 Theodoret proceeded in panegyric style, praising the “exactnesss” of Leo's doctrines. Naturally, he professed full agreement, on Christology and on the scandalous recent council. When Theodoret turned to himself, he chose not to play up his sufferings. Rather he stressed his diligence as a manager of eight hundred churches, a hunter of heresies, an ascetic, and a benefactor. If Leo wanted doctrinal details, Theodoret offered his full library of writings.137 At the same time, Theodoret appealed beyond the pope. He wrote to Bishop Florentius, probably a confidant of Leo's, requesting help in defending justice. He also wrote to Renatus, the papal legate disrespected by the recent council. This letter explicitly endorsed Roman primacy as it again recalled the author's past patronage.138 Theodoret asked the archdeacon of Rome to “kindle the zeal” of the pope. And he sent all these notes with a special entourage: two of his country-bishops and a liaison to Cyrrhus's monasteries.139 Thus he surrounded Leo with living examples of his conscientiousness and with reinforcing second-hand messages. The most striking feature of these appeals, however, was Theodoret's actual request. “I supplicate and beg your Holiness to help me,” he wrote to Leo, “as I appeal to your just and righteous tribunal. Above all I beg to learn from you whether or not I should be satisfied with my unjust deposition.”140 This time, he (nearly) suppressed his “confessing.” He promised loyalty, like a client accepting subordination.

FIGURE 20. Theodoret's self-defense ensemble, 448–451, according to his letters. adc = archdeacon, amand = archimandrite, cos = consul, codm = count of the Domestici, colar = count of the sacred largesses, emp = emperor, magof = master of offices, patr = patrician, ppo = praetorian prefect of the East, pr-lg = priest-legate, puc = urban prefect of C-ple, schol = scholasticus.

It is not clear from extant letters how far Pope Leo supported Theodoret,141 But even before the death of Theodosius II, something was shifting behind the scenes. Leo made contact with the empresses Galla Placidia and Pulcheria by early 450.142 When Marcian secured the emperorship in August, Theodoret found that he had court allies. Anatolius's partiality was surely no secret. More surprising was the support of Aspar the patrician and Vincomalus the master of offices, since neither had been considered Theodoret's friend.143 In September 450, the new emperor started reversing sentences of exile. From Nicertae, Theodoret launched new appeals. To monks of the capital, he sent a public letter, detailing his Christology. To monastic allies, such as the Akoimetoi, he sent full doctrinal dossiers. He even responded to a group of soldiers with quotable arguments.144 Meanwhile, Theodoret approached colleagues who had abandoned him. He offered his forgiveness (whether or not it had been requested).145 He thanked the emperor and empress through several intermediaries.146 But he hoped not to rely only on imperial favor. His aim was to reestablish a network, which could affirm his restoration.

Theodoret did rebuild some support among clerics, monks, and courtiers. By this point, however, his claim to social leadership had been transformed. Theodoret had high-placed contacts, to whom he was now beholden. His social debts made it harder to make grand requests without seeming presumptuous. Theodoret had old clerical allies, from whom he was now separated. His presence reminded many bishops of their own uncomfortable decisions. Theodoret retained a base of clients. Some clerics, monks, and laypeople now treated him as an exemplar of resolute faith.147 Such veneration enhanced Theodoret's claim to holiness, but it also limited his social versatility. The more he played a confessor, the harder it was for him to tailor his performance of appeals. It is unclear how much Theodoret served as an advocate in the 450s, given the lack of extant letters. In any case, he faced new obstacles in performing grand appeals.

In the Eutychean controversy, we thus see an equally significant link between doctrinal conflict and patronage performance. Doctrinal foes attacked not just Theodoret's Christology, but also his career as a patron. They understood that his mediation of (non-doctrinal) favors was one key to his influence, doctrinal and otherwise. Theodoret defended all aspects of his career with a strategy of perseverance. He reached the right contacts, at a fortuitous moment, to save his episcopacy—except now he may have been typecast as the confessor, rather than the flexible mediator.

Ultimately, Theodoret's performances of patronage were inseparable from his performances of Antiochene leadership. His doctrinal influence rose or fell based on his ability to trade favors. His patronage appeals rose or fell based on his acceptance as a voice of orthodoxy. So important was patronage to Theodoret and his allies that it even affected their expressions of theology, to which the final chapter shall now turn.