5

Forging Community

Theodoret's Network and Its Fall

It was probably the summer of 448 when Theodoret received a key surveillance brief from his confidant, Basil of Seleucia in Isauria. For several months Theodoret had confronted shadowy opponents attacking Antiochene doctrine. Rumor had it that someone in Cilicia was preaching that God suffered—a red flag for altered allegiance. Theodoret had alerted the bishops of Cilicia,1 but Basil was a more reliable spy. When Basil reported no sign of this heresy, Theodoret took joy at the “heartening news.” Then he made a new request. Alexandria had sent a prelate to the capital to run an anti-Theodoret campaign. “Let your piety deign to show [this Egyptian] the proper goodwill, as usual,” he said with a wink, “and to array against falsehood the truth.”2

Over the next year Basil proved Theodoret's best ally, until his defection. For months he organized in the capital. In the fall he helped to condemn Eutyches, the Egyptians' monastic ally.3 It was thus startling when, two or three months later, Basil ceased writing letters. “No one familiar with our affinity,” Theodoret wrote, “would believe it.” Theodoret exhorted him “not to follow a multitude into evil (Exodus 23:2).” But he knew that Basil had joined the accusers. “I have for all other reasons feared this tribunal [of the Lord],” Theodoret stated, “but amid the words spoken against me I have reasons for consolation from the thought of it.”4

Theodoret's relationship with Basil captures both the achievement and the paradox of his term of leadership. After the Nestorian crisis Theodoret took the initiative. His writings suggest that he restored the Antiochene network. Theodoret's instructions to Basil seem to underscore his success. A core of followers carried out his plans. Theodoret's writings, however, hide seeds of opposition that were germinating. In 448 and 449 he watched his network disintegrate—faster apparently than he could imagine.

This chapter sketches Theodoret's performance as Antiochene leader and puts it to the test. In the late 430s the Antiochene network faced several mini-crises, to which Theodoret responded. He reinforced core Antiochene relations. He expanded contacts with distant clerics and lay officials. He reached out to non-Greek speakers and monastic groups. At the same time, Theodoret offered a new sense of Antiochene identity. He interwove doctrine, history, and social experience in ways that validated his own performance as leader. Still, none of this guaranteed a successful community. In the “Eutychean” controversy (447-451), opponents attacked Antiochene traditions and overthrew the Antiochenes. It is difficult to tell if Theodoret's network was robust or illusory. It may well have been robust and yet more vulnerable than Theodoret could see.

LOOMING DISASTER: SYRIAN DOCTRINAL

CONFRONTATIONS, 435-440

Theodoret's leadership started in the late 430s amid frustration. Antiochenes remained vulnerable, despite their agreements with Cyril of Alexandria and the imperial court. Cyril and his allies made new demands of Syrian clerics, to guarantee their orthodoxy. Each demand threatened Theodoret's bonds with peers and protectors and could have unraveled his network. This time, however, confrontations strengthened the Antiochene community. Such success is difficult to explain. But one factor was surely Theodoret's performance as leader.

The situation that greeted Theodoret and his reunited associates was unappealing. By 435 the Nestorian dispute had permeated clerical and monastic communities. Most Antiochene bishops had settled their internal arguments. Some had condemned Nestorius, while others had said nothing. But everyone (except the exiled holdouts) had rejoined communion.5 The result was, more or less, the social arrangement mapped in chapter 2. Official reconciliations, however, did not end Cyril's suspicion toward the Syrian clergy. Nor did they quell the ill will between Antiochene loyalists and defectors. In Edessa, Rabbula's followers cohabited uneasily with his critics. Each group prepared translations and canvassed for allies.6 In Antioch, at least seven priests and archimandrites enrolled as Cyril's proxenoi. They informed against John and his allies. A few even rejected his communion. John and his colleagues tried to enforce discipline, but with every attempt the priests or monks sent Cyril a new appeal.7

Dissension in Syria, in fact, incubated new controversy. By 435, dissident clerics and monks were reporting “Nestorianism” to Cyril,8 who informed the court. So the emperor sent Aristolaus back to Syria. He ordered bishops either to condemn Nestorius explicitly or to join him in exile. Worse, the emperor told the bishops to send statements to Cyril for inspection.9 Cyril wrote new treatises to sway wavering bishops. His reports to the court kept the Antiochenes under a cloud of suspicion.

Dissension combined with cross-cultural tensions to cause the Antiochenes deeper problems. When Rabbula defected in 432, he denounced Theodore of Mopsuestia as Nestorius's mentor.10 In late 434, he renewed this attack. He compiled a list of Theodore's objectionable teachings, which he correlated to statements of Nestorius. He sent the list to Acacius of Melitene, who enlarged it into a whole anti-Theodore dossier.11 The controversy expanded when the two anti-Antiochenes linked up with Sahak, the katholikos of Persian Armenia. Sahak was already feuding with “Syrian” clerics in Armenia. When the Sassanid court deposed him in 435, he sought allies across the Roman frontier.12 With Acacius of Melitene's help he sent envoys to Constantinople, asking for a denunciation of the “Syrian heresy.”13 Bishop Proclus replied with his Tome to the Armenians, a middle ground Christological summary that condemned some older Antiochene positions but did not name Theodore as their author.14 Rabbula and Acacius were not satisfied. When Rabbula died in 436, the Antiochenes recirculated translations of Theodore.15 So Acacius turned to Cyril, who denounced “Nestorius's teacher” far and wide. By 43816 Cyril and Proclus were collaborating with some imperial support. The court sent Syrians the Tome (to affirm) and Theodore's statements (to condemn). Again, Cyril denounced their “Nestorian” heresy.17 The stakes were high. Theodore (unlike Nestorius) was “held foremost among those who came before us [in the East].”18 To condemn him was to destroy a key source of Antio-chene solidarity.19

Between rumors of Nestorianism and denunciations of Theodore, the Antio-chenes faced another confrontation. But this time, the network responded with solidarity. First, the Antiochenes denounced Nestorius. Some (e.g., John of Antioch and Helladius of Tarsus) did so explicitly; others (e.g., John of Germanicea and Theodoret) equivocated.20 Even so, they maintained mutual support, despite pressure from Cyril and his friends.21 Then the Antiochenes dealt with the dispute over Theodore. They affirmed Proclus's Tome but refused to condemn their hero.22 Cyril persisted with polemics,23 but seventy-five Syrian bishops gathered to defy him, and to ask the emperor for peace.24 By 440, Acacius of Melitene was gone. And the court granted the petition from the Syrian bishops.25 Proclus insisted he meant to condemn no one but Nestorius. And Cyril dropped his campaign against the dead.26

Why, in the late 430s, could the Antiochenes now defend themselves? One reason seems to involve Theodoret. Scholars sometimes credit Proclus and Cyril with the moderation to end the dispute. Or they claim that the feud was quashed by Theodosius II's court.27 These “moderates,” however, and even the emperor, were responding to Syrian bishops, united by renewed Antiochene leadership. John of

Antioch played an important part in the effort, calling councils and managing correspondence. He was aided by translators, ambassadors, and coordinators. But Theodoret proved essential. Not only did he write (the now fragmentary) In Defense of Diodore and Theodore. He led a whole program of community building, which continued after the conflict subsided.

RECRUITING AND REROOTING: THEODORET'S

NETWORKING PROGRAM

Theodoret's organizational efforts took many forms. One was social initiative. In chapter 2, we noted the segmented state of Antiochene social relations. As opponents probed for Antiochene weaknesses, Theodoret sought to reinforce and grow his network. On one front Theodoret crafted a new central clique, including familiar prelates and those newly ordained. At the same time, he canvassed bishops in Armenia, Anatolia, and Constantinople. Theodoret backed up his clerical network with new contacts at court. He also sought support from Syria's lay elite. It is difficult to measure these efforts, but we can follow the strategy. As Cyril tried to marginalize the Antiochene network, Theodoret worked to broaden and deepen its social roots.

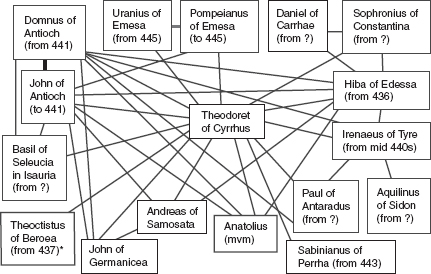

Theodoret's earliest initiatives aimed at the old core network. One target was Andreas of Samosata. By 436, Andreas had restored an “intimate” link with Theodoret and was greeted as a familiar companion.28 Another target was John of Germanicea. After 436 the two men collaborated doctrinally, even in pressing circumstances.29 Theodoret reforged a bond with John of Antioch. Not only did the primate defend Theodoret against outside critics. He must have trusted Theodoret to guide his nephew Domnus, a monk in Palestine,30 who in 441 became bishop of Antioch. Other core players in the Nestorian crisis disappear in later sources. Most passed away in the late 430s or early 440s. Theodoret's scale-free network could absorb these steady losses, so long as he recruited their replacements.

Not surprisingly, Theodoret's initiatives extended to bringing in new bishops and confidants. Sometimes Theodoret helped to replace existing allies, like Dexianus of Seleucia in Isauria (who died after 435). Little is known about the first successor, John. But next, Basil became Theodoret's incomparable (if temporary) friend.31 Sometimes Theodoret recruited on less friendly ground. Paul of Emesa and Acacius of Beroea had troubled Theodoret during the controversy. In the mid 430s they were succeeded by Pompeianus and Theoctistus, who joined him in tighter bonds.32 By the mid 440s Theodoret had enough support in Emesa to advance Uranius over a local rival.33 The most important efforts, however, emerged in Osrhoene, which had been marginalized from the network. When Rabbula of Edessa died in 436, Theodoret's allies there elected Hiba, whom Rabbula had once mistreated.34 While Hiba faced protests, he reconnected suffragan sees to the network, often by ordaining his relatives.35 Interventions then proceeded in Phoenicia I. There Theodoret and Domnus engineered the election of Paul of Antaradus over a local candidate.36 When the bishop of Tyre died in the mid-440s, they consecrated Irenaeus, the familiar exiled count, who also recruited to fill vacancies.37 Most of the new bishops proved close allies of Theodoret. Most became at least sectional hubs, restoring Antiochene influence to every Syrian province.

FIGURE 15. Theodoret's new inner circle, 435-448, according to letters and Syrian conciliar documents. Mvm = master of soldiers.

* Acacius of Beroea's death is here assumed to date to 437. See start of chapter 1.

Beyond the episcopate, Theodoret worked to restore relations with lower clerics and monasteries, to bring the threat of riots to an end. This effort meant restoring clerical discipline. He toured his diocese in search of “heretics.” He surveyed regional clerics for doctrinal precision and pastoral diligence.38 Just as important was social maintenance. He tended to local hermits, including Symeon Stylites, Jacob of Cyrrhestica, and Baradatus.39 He contacted affiliated monasteries, praising their leaders while looking for new ordinees.40 None of these tasks was unusual for a bishop in his own diocese. Theodoret simply extended his oversight to a broader area.

Theodoret aimed further social efforts at clerics outside the region, where he tried to rebuild sympathy. One target was Constantinople. Since the early 430s Bishop Proclus had sometimes been inimical. Still Theodoret strove for a functional friendship. Doctrinally the two never fully aligned but could still cooperate.41 Meanwhile, Theodoret courted Constantinople's clerics and monks, once so hostile to Nestorius. He connected with a few priests and visiting bishops, as well as the oikonomoi. And he sought sympathy from archimandrites, including Marcellus, head of the (once Syrian) “Sleepless” monks (Greek: Akoimetoi)42 Another target was the Anatolian corridor leading to the capital. In a region of anti-Antio-chenes, Theodoret approached younger bishops, like Eusebius of Ancyra.43 At the least he hoped to find churchmen who could offer hospitality. Theodoret and his confidants sought out clerics in the Syrian-Armenian borderlands. Despite the growing anti-Antiochene sentiment, Hiba supplied allies with further translations.44 When the Sassanid court launched an anti-Christian persecution in the mid-440s, Theodoret offered encouragement and advice.45 He even nursed hopes of better relations with Cyril.46 Theodoret knew he could not count on doctrinal agreement beyond his home region, so he sought cooperation, sympathy, and maybe new friends.

Finally, Theodoret looked beyond the clergy and monasteries to the political elite. The Nestorian crisis had already given him key allies. Irenaeus and Candidianus had lost imperial favor, but Anatolius grew in stature. Meanwhile, Theodoret turned to former foes. He sent letters to nearly every court figure except Theodosius—even to Empress Pulcheria.47 Closer to home, he courted officials who had played minor roles in the dispute: the count of the East, provincial governors, former office-holders, and bureaucrats. Most of these officials had shown no sympathy for Antiochene doctrine. Theodoret had to relate on general terms (patronage, friendship, and pastoral care).48 But even general relations could reduce the chance of doctrinal hostilities.

Theodoret's social efforts can be seen as responses to the assaults of his foes. Cyril sought to cast the Antiochene network as a vestige of Nestorianism. The more he presented the Antiochenes as regionally diminutive, the more he could paint his side as “universal.”49 Meanwhile, he looked for dissident Syrian clerics and archimandrites. If Syrian bishops distrusted their subordinates, they would have a hard time perpetuating their party. To protect his associates Theodoret needed to solidify his base. Surveillance of subordinates and recruitment of bishops kept Cyril's agents in check. At the same time, Theodoret had to reach beyond the Syrian clergy. Distant bishops and officials were less likely to condemn a familiar client or friend. A multi-front social strategy carried liabilities. The doctrinal tropes that brought network solidarity could prove troublesome in external relations, as we have seen. But well managed, these efforts countered hostile rhetoric and forestalled local opposition.

Ultimately Theodoret's greatest tool was the perception of social connectedness. It is not clear how much Theodoret won over churchmen or lay officials beyond his inner circle. His correspondence is one-sided and his list of contacts far from comprehensive. The best Theodoret could do was portray his efforts in letters. Showcasing his Antiochene attachments made Theodoret look like a good representative, encouraging external contacts. Likewise, displaying external relationships made him look like a good social mediator, tightening his network bonds. These virtual relationships, of course, had to be the right ones. For decades the best way to prove orthodoxy was to have orthodox companions. It was no accident that when Theodoret came under attack in 448, he began reading off names of famous friends.50

PREACHING IN TONGUES: A NEW

MULTILINGUAL DYNAMIC

One mark of Theodoret's success was thus the accumulation of allies. Building relations, however, was complicated in Syria by linguistic divides, as we saw in chapter 1. After 436 Theodoret and his confidants remained eager to reach non-Greek speakers. They expanded doctrinal translation in Syriac and Armenian. They also encouraged education in Greek and celebrated the multiple Christian languages. The translators still met resistance. By seeking cross-cultural communication, however, the Antiochenes laid the groundwork for a more multilingual church community.

The Antiochenes' new multilingual efforts grew out of prior generations' experience. Any clerical network that hoped to span Syria needed a multilingual alliance. As we have noted, however, translation was trouble. New terminology might be greeted hostilely. When successful it could still divide adherents from their wider linguistic community. Translation might also clash with cultural ideology. Greek stereotypes still cast Aramaic and Armenian-speakers as simpletons.51 Early Antiochene translations ran afoul of these problems. Syriac and Armenian versions of Theodore's work inspired fiery counterreactions, led by Rabbula and Sahak respectively. Meanwhile, the translations scared paternalistic Greeks—Nestorianism might infect the defenseless.52 Linguistic difference did not create the conflict over Theodore, but it intensified the dispute.

It was in the late 430s that the Antiochenes renewed efforts to bridge the linguistic divides, led by Hiba of Edessa. With Rabbula dead, Hiba again translated works of Theodore into Syriac, and circulated some of this material. As Acacius of Melitene spread around Greek lists of Theodore's “heresies,” Hiba countered, with Syriac lists of his orthodox teachings.53 Beyond textual work, Hiba involved himself in broader circles of education. There is little independent support for the sixth-century accusation that he organized a pro-Antiochene “School of the Persians.” But he did deal with Armenian and Syriac teachers in Edessa, some of whom may have collaborated as Antiochenes.54

Theodoret's multilingual involvements were less direct but important. So far as we know, Theodoret wrote only in Greek, though he showed Aramaic knowledge.55 But he must have heard of Hiba's activities and probably approved. Theodoret spread Antiochene knowledge in his own way. He urged students to master Greek sophistic learning before specialized doctrine.56 His traditional approach did not undercut Hiba's labors; it might even create new expert translators. Theodoret intervened more directly regarding textual circulation. Older Syriac gospel texts, for instance, were replaced with “more accurate” renderings. More generally, he listened in on preachers, in Aramaic and Greek.57 Perhaps Theodoret's largest contribution was rhetorical. His writings celebrated the multilingual nature of Syrian churches and monasteries. He praised Ephrem Syrus (Syriac writer par excellence), and advertised Greek versions of his writings.58 While hardly the first Greek writer to mention a Syriac work, Theodoret made cross-linguistic contact into a virtue.

The multilingual efforts of Theodoret and Hiba bespeak a goal of broadening their network. In the early 430s connections were weak enough that Rabbula could command most of his subordinates to defect. Hiba and Theodoret worked to prevent such reversals. Translating and circulating texts spread specialized Antiochene knowledge. So did higher education. Censorship, meanwhile, removed alternative tropes. Theodoret and Hiba performed different tasks with a common goal. By broadening textual access and encouraging multilingual education, they could better integrate clerics of all tongues.

The new Antiochene multilingual programs met with divergent reactions. Some Syrian clerics were better integrated into the network. The seventy-five bishops who defended Theodore in 440 must have included men whose first language was Aramaic. Translation efforts probably aided connections across the Sassanid frontier, though the actual breadth of these links remains elusive.59 Translations also enraged some opponents. In Armenia, Antiochene allies lost ground. Even in Osrhoene, Hiba offended local clerics, including bishop Uranius of Himerium (who spoke little Greek).60 Meanwhile, Theodoret found objections to his push for sophistic learning. One cleric complained that he had been ordered to “expound on…Plato and Aristotle,” and to sign a creedal statement, before interpreting Scripture.61 Neither Theodoret nor Hiba could quell fears that they were infecting a helpless East. Broader specialized knowledge may have cemented some bonds. But it disturbed ambiguities that helped to preserve a sense of shared orthodoxy.

Antiochene multilingual efforts yielded mixed results in the 430s and 440s but played an ongoing part in Theodoret's program. Hiba's translations continued. Texts circulated, allowing broad sharing of equivalent cues. Theodoret's advocacy of Greek education remained important, while relations with Syriac/Aramaic teachers deepened over time. Theodoret even tempered his sense of Greek superiority with encouragement of cultural exchange.62 Again, perceptions mattered. Theodoret's network was harder to marginalize if it seemed to bridge linguistic lines. Theodoret and Hiba thus fostered a new dynamic in multilingual clerical relations, which would grow beyond their lifetimes.

BEFRIENDING THE FRIENDS OF GOD: NEW ASCETIC RELATIONS

Theodoret's networking efforts stretched across linguistic boundaries. They particularly reached out to Syria's ascetics. Theodoret's prominence has rested heavily on his relations with famous hermits, publicized by his History of the Friends of God (a.k.a. Historia religiosa or HR). This text so enhanced his reputation that the sixth-century miaphysite Severus of Antioch tried to actively reclaim Symeon Stylites from his clutches.63 The Historia religiosa includes a “historical” part on fourth-century ascetics, which we discussed in chapter 3. More than half of the HR, however, deals with Theodoret's contacts circa 440.64 The HR can be imaginative, not least when the author discusses himself. Other texts by Theodoret, however, note his ascetic connections and provide context. The HR served as a rhetorical means to reinforce the Antiochene network. Not only did it claim holiness by association; it presented ascetics to clerics and lay elites in ways that bridged cultural divides.

One of Theodoret's plainest assertions in the HR was that he had befriended the friends of God. Writing about hermits and archimandrites, he touted his reciprocated companionship and exclusive access. He was the only bishop, he tells us, allowed into Marana's enclosure. He gave the Eucharist to Maris by special request. When Jacob of Cyrrhestica was deathly ill, Theodoret rescued him from the crowds. Naturally the holy man “immediately opened his eyes.”65 Throughout the text, Theodoret advises ascetics. He protects them from excesses and gives them the imprimatur of orthodoxy. Even when he depended on ascetics, he presents himself as chosen. It was a hermit, we are told, who enabled his birth.66 Recent research has stressed the tendentious nature of Theodoret's assertions. He may exaggerate his intimacy with the ascetics. And he describes subjects using classical terms not shared by other Syrian sources.67 In our skepticism, however, we should not lose sight of the social context. Letters and other documents reveal links to key monastic figures that were not pure invention.

In fact, Theodoret's letters provide a different perspective on his courting of the monastic community. In some ways the letters support the HR's picture. Theodoret wrote to instruct monks in Antiochene orthodoxy. He wrote to ask for leading ascetics' personal attention and touted their cooperation.68 Meanwhile, he visited ascetics locally and regionally. And he conducted oversight through an “exarch of the monasteries,” not unlike Rabbula.69 Theodoret's letters differ from the HR in their tone of mutuality. His doctrinal instruction was given as a service to “fellow mariners” on the ship of God.70 Friendly letters stressed how much ascetics helped the author. “We are inactive and prone to laziness,” he told one archimandrite, “and stand in great need of your prayers.”71 Most strikingly the letters reveal how ascetics influenced Theodoret. When Symeon, Jacob, and Baradatus pressed him to compromise in 434, they “afflicted [him] with a deep sadness,” and he heeded their call.72 This influence extended to less famous figures. Theodoret turned to one archimandrite to comment on new doctrinal writings.73 And, of course, he sought to recruit new bishops from monasteries: Domnus of Antioch, Sabinianus of Perrha, and probably others.74 Clearly he wanted to show his inclusion of worthy monks.

Theodoret's interactions with ascetics grew out of prior Antiochene experience. Theodoret's forebears had sought monastic help since the 360s. Doctrinal oversight and cooperation led to recruitment, as we saw in chapter 3. But not every relationship went smoothly. The diverse monastic movement had internal cultural clashes, and some groups (Messalians, Sleepless ones) ran into trouble with the urban clergy.75 Then came the disputes of the 430s. Monastic leaders who once showed zeal against Jews and pagans (e.g., Barsauma) now did so against “Nestorians.” By the mid 440s, Antiochenes were uncertain of their ascetic backing. So Theodoret wrote his letters, calling for closer alliances by stressing inclusion, doctrinal and otherwise.

It is in light of this social initiative that we must view Theodoret's hagiography, for the HR rhetorically reinforced his networking plans. The HR presented ascetics as part of an idealized community. While it reveled in their diverse self-deprivations, it emphasized their bonds across linguistic, geographic, and gender lines. Parts of the HR drew a lineage of mentorship from founding fathers (like Marcian and Julian Saba) to contemporaries. Other sections stressed the role of clerical ambassadors, who not only worked with monastic leaders, but also connected circles of disciples.76 All of this served as an apologetic to outsiders. By displaying Syria's holy people, Theodoret lent support to their clerical associates. Indirectly he countered suspicions of heresy.77 Just as important, the HR reinforced relationships within the Antiochene network. He featured cooperative ascetics, which made them more attractive to clerics. And he featured ascetic-minded clerics, which made them more attractive to the monks.

Most crucially, Theodoret approached ascetics with a common explanatory language. In letters, he praised ascetics for their “toils of virtue” in pursuit of “victory.” The HR extended these metaphors. Monasteries become “exercise grounds (palaistrai),” and monks, “athletes of virtue.”78 Practices are justified by philosophic argument and biblical typology. Theodoret's explanations differ from those of Syriac writers. But his work had the goal of creating new social cues. By mixing sophistic language with regional practice, these signals could work across the cultural breadth of his network.

In his ascetic networking, Theodoret again relied on creating good impressions. It is difficult to measure his success at winning over monks. Some supported his doctrines and allies; others remained neutral or hostile. Theodoret's HR, however, circulated widely, in Greek and in Syriac.79 His work presented a rich web of clerical-ascetic relations. Not only did this make the network look well rooted, it encouraged further bonding between himself, his colleagues, and his holy friends.

CRAFTING COHERENCE: DOCTRINE, HISTORY,

LEADERSHIP, COMMUNITY

Theodoret's social initiatives thus proceeded on multiple fronts. In each case, new relationships coincided with rhetorical efforts to modify social cues. Besides canvassing, Theodoret worked culturally to represent his community. Between 436 and 450, he wrote half of his doctrinal works, most of his exegesis, and his Church History (as well as the HR). Generally this corpus has been carefully studied.80 What has not always been recognized is how well these writings fit together within a social context. His exegesis and treatises offered a new doctrinal handbook, to give the Antiochenes a shared line of reasoning. His historical work provided a basic narrative to supply the Antiochenes with a renewed sense of community. When Theodoret achieved prominence in the mid-430s, his network was held together by scattered social signals. Over fifteen years of perpetual persuasion he outlined a coherent Antiochene identity.

Theodoret's effort to represent the Antiochenes centered on Christological doctrine. In 439 he wrote In Defense of Diodore and Theodore; in 447, the Eranistes. All along he reshaped the tropes of prior theologians to fit his situation. He began from a firm Antiochene base. He showed concern for “exact” terminology and emphasized the distinctness of God. He cited the soteriological role of Jesus' humanity, and defended “two natures in one Christ.”81 Theodoret avoided certain controversial Antiochene tropes, such as “assuming God” and “assumed man.” Instead, he wrote of abstract natures, or the Cyrillian-sounding “divine Word” and “Word incarnate.”82 Theodoret gave advice for how to stay orthodox: Christological balance. Between the extremes of two sons and one nature sat his dyophysite position.83 For him the Formula of Reunion captured this balance, if read correctly. Theodoret worked with Antiochene cues under a new sensibility.84

Theodoret also represented Antiochenes through exegesis. Between 436 and 450 he commented on nearly every corner of Scripture. Again, he retained an Antiochene foundation. He kept some of Theodore's emphasis on grammar, vocabulary, and narrative integrity.85 He distinguished his exegesis, however, by his style of typology. While Theodore had limited types of Christ to a few symbols, Theodoret expanded the list by loosening the need for an exact match.86 Theodoret, like his predecessor, read Scripture as having “literal” (Greek: kata ten lexin), metaphorical, and typological meaning. Except with some texts (like the Song of Songs) he looked past the “literal” to a “spiritual” truth. This deeper search sometimes looks more like the work of Origen than the work of Theodore.87 By expanding the use of types and accepting a spiritual subtext, Theodoret blurred the limitations that Theodore had once drawn.

Theodoret's doctrinal and exegetical presentation accorded well with his efforts to expand and reinforce his network. Traditional formulas and interpretive tropes affirmed core Antiochene alliances. His spiritual readings of Scripture spoke to a wider audience. The notion of doctrinal balance not only affirmed Antiochene orthodoxy; it made sense of the choice to endorse Proclus's Tome while resisting other formulations. Even Theodoret's literary stylings supported the renewed network. Outwardly the Eranistes was dialogue, a form used by philosophers and Christian writers, including Cyril, for doctrinal argument. But while many dialogues featured staid agreement, the Eranistes depicted a vital debate.88 This simulated conversation affirmed the Antiochene practice of deliberations. It even indirectly blessed the schisms of the early 430s, because the argument had led to doctrinal balance. Theodoret's writings did more than modify old doctrinal tropes. They modeled and celebrated Antiochene theological discourse.

As Theodoret represented Antiochene doctrine, he also retold Antiochene history. His Church History was probably written in 449, during renewed controversy. From his hagiography and letters, however, it is clear that he had long pondered the Antiochene clerical heritage in light of his own experience. As noted in chapter 3, the Church History told heroic tales of Syria's Nicene bishops, especially Meletius of Antioch and his followers (Flavian, Diodore, Theodore, and Acacius). Theodoret's information seems accurate enough, but that did not prevent him from narrating in a pro-Antiochene fashion. We have already noted how Theodoret defended the honor of his forbears, while covering over troubling episodes. Understandably he celebrated Syrian heroes with his colleagues. At the same time Theodoret's narrative offered moral exemplars, men who resisted imperial pressure as they held to orthodoxy.89 He probably hoped to edify his core allies, and maybe to draw in figures on the periphery. Theodoret's history served as a practical resource. It suggested ways to maintain solidarity, from public protests to regional recruitment. And, as we noted, his writings promoted the role of non-Greek speakers and ascetics in settling past controversies. Thus he aimed his moral models and practical advice toward a wider audience. The Church History used real people and events to create an idealized Antiochene heritage. By 449, and probably before, Theodoret was working on narratives in which he could find a place as part of the community.

Theodoret's teachings and stories were well suited to his social environment, but they did not sell themselves. The author had to support them with a performance of leadership. As a leading figure Theodoret had assets: his experience, his doctrinal acumen, his asceticism, and his record of mediation. Above all he had elite connections and centrality within his network. Rarely in his letters did Theodoret brag about his abilities.90 Instead he left hints, by praising similar attributes in others.91 Theodoret remained a suffragan ill positioned to command his colleagues. All he could do was display persistent persuasion: “Even if your religiosity persecuted, chased, and used invective against us,” he told Alexander in 435, “I would not cease prostrating to beg at the feet of your holiness.”92 Theodoret was not always gentle. He threatened dissident clerics and probably had a colleague deposed.93 In his writings, however, he hid any coercion behind a welcoming tone.

Theodoret's main performance of leadership lay in his writing. Through doctrinal and exegetical work Theodoret laid claim to Antiochene orthodoxy. His polished texts showed mastery of Scripture and dialectic. His prolific pen (more than one book per year) left little room for other voices of authority.94 Through his historical narrative Theodoret linked himself to past mentors. He claimed the mantle of Theodore, for his doctrinal mastery, and the legacy of Acacius of Beroea for his mix of strictness (akribeia) and flexibility (oikonomia).95 Whenever he wrote, Theodoret drew principles from his own experience. It should not surprise us that he praised mixing asceticism with clerical life, or seeking balanced doctrine. He was, after all, an ascetic turned bishop, who had brokered compromise. Theodoret wove himself into doctrinal discourse and church history. Thus he made his leadership seem natural.

Beyond self-affirmation, Theodoret's literary efforts outlined what it meant to be an Antiochene. His doctrinal syntheses resonated with his picture of Antiochene heritage. Both lent support to his social initiatives and backed up his claim to authority. By mixing communal narrative with personal performance, Theodoret supported his theology. He also supported his relationships and those of his allies. Narratives and authorial performances interlinked scattered social cues, and thus forged an Antiochene identity.

The coherence of Theodoret's writings, however, leads us into a dilemma. It is difficult to unravel Antiochene traditions from Theodoret's own concerns. Theodoret spoke for the Antiochene community, but his views may not have been widely shared. Though he tried to look inextricable, others may have been willing to dispense with him. The source of our trouble is Theodoret's control of the sources. Between 436 and 447, most extant social records come from his pen. After 447, the fuller mix of sources casts his network in a rather different light.

FRAGILE FELLOWSHIP: THE COLLAPSE

OF THEODORET'S NETWORK

From the vantage point of hostile outsiders, the Antiochene community proved more fragile than Theodoret's writings imply. From 447 clerics entered the “Eutychean” controversy. The network, which Theodoret presented as a coherent community, disintegrated at the hands of its adversaries, backed by the imperial court. The process is recorded in Theodoret's letters, but also in conciliar acta (from Ephesus in 449 and Chalcedon in 451). Some editors were sympathetic to Theodoret; others were hostile.96 Together they reveal from multiple angles the undoing of Theodoret's efforts.

The dismemberment of Theodoret's network began from scattered wellsprings of hostility. The most obvious was Alexandria. By 440, Theodoret and Cyril had struck a truce. They had both endorsed the Formula of Reunion and Proclus's Tome. But they remained mutually suspicious. Cyril's death in 444 led to the succession of Dioscorus, and this former archdeacon under Cyril placed less value on his compromises. Dioscorus reconnected with Cyril's allies, including Juvenal of Jerusalem and the bishops of Cappadocia. He also approached Theodosius's court, where the loose support won by Cyril carried over to his successor.97 It is not clear if Dioscorus had any offensive plans; he was simply managing an existing (anti-Antiochene) coalition.

Another source of hostility was Constantinople. Here the problem was not bishops (Proclus and, after 446, Flavian), but courtiers and monasteries. Eutyches may have been more a simple archimandrite than a scheming mastermind. But he did have allies in the monasteries and at least one at court (the eunuch Chrys-aphius).98 In fact, the court remained suspicious of Theodoret and his (known) networking activities. By 444 it had barred the bishop of Cyrrhus from meddling in church appeals hearings.99 It would not take much to convince Theodosius that Theodoret meant trouble.

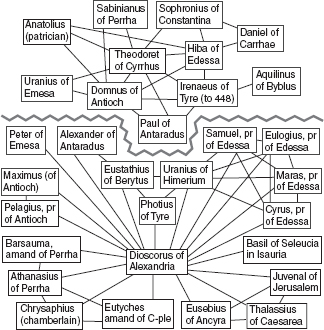

Extraregional hostilities thus awaited Theodoret. Further hostilities involved resentful clerics within Syria. The first troublesome figure was Athanasius of Perrha, a former bishop in Euphratensis. In 443 Athanasius had been accused of stealing church property. A council in Hierapolis was called to investigate. When Athanasius failed to appear, he was deposed. He appealed to Cyril and Proclus, who interceded with Domnus of Antioch. But the appeals hearing also sided against him.100 Convinced (justifiably) that Theodoret had organized his downfall, Athanasius traveled to the capital and plotted revenge (see chapter 7 for details). Another source of opposition was clergymen from Osrhoene, loyal to the memory of Rabbula. In Edessa four priests (Samuel, Eulogius, Maras, and Cyrus) ran into trouble with Bishop Hiba. They found sanctuary nearby with Uranius of Himerium. In 445, the quartet petitioned Domnus, denouncing their bishop as a heretical tyrant. When Domnus let the matter drop, the four blamed Theodoret and sought new avenues of appeal.101 The third party came from Phoenicia I: opponents of Irenaeus of Tyre. Before Irenaeus most of the province had been aligned with Cyril. The arrival of this reputed Nestorian must have inspired dissent, which grew as he appointed loyal Antiochenes (e.g., Aquilinus of Byblus). The dissenters assembled under Eustathius of Berytus. When their appeals went nowhere, they understood why.102 Individually, these were local disputes, which did not always concern doctrine. But other dissenters existed: Cyril's old proxenoi (e.g., Maximus, Thalassius, and John) and Rabbula's rioters. By 447, a new Syrian clerical coalition was forming (see figure 16).

FIGURE 16. The opposition to Theodoret's network in 449, according to letters and conciliar records. amand = archimandrite, pr = priest.

The spark of new conflict was apparently Theodoret's own writing. In 447, he published his Eranistes, as noted. This dialogue criticized some of Cyril's formulas (“out of two natures”) and qualified others (“one nature incarnate”). Provocatively, it called these positions a heretical pastiche, held by simpletons.103 Somewhere this argument touched a nerve. The opposition set forth to counter Theodoret's doctrines. This time, however, they made no direct demands, just back-channel accusations. Theodoret did not acknowledge the reach of his foes until he was already under threat.

From late 447 to early 448, Theodoret's network was repeatedly attacked; each time the imperial court got involved. First came a move against Irenaeus. In late 447, his local critics circulated accusations in the capital. The charges included Nestorianism, nepotism, tyranny, and escape from exile. But their firmest argument concerned episcopal eligibility: Irenaeus had been consecrated while married to his second wife, violating a (rarely observed) canon.104 Theodoret defended Irenaeus's rectitude, orthodoxy, and legitimacy. But Theodoret was unsure of the emperor's opinion, until March 448, when the court deposed Irenaeus and confined him.105 Meanwhile, opponents started new attacks on Hiba. Imperial officials were presented with eighteen charges against him, ranging from embezzlement and nepotism to heresy. Pressed by the court, Domnus called a hearing for after Easter 448. Eleven bishops (including Theodoret) dismissed the financial charges (the other charges were not presented by the insecure plaintiffs).106 So the quartet turned to Constantinople. By fall the court had vacated the tribunal's ruling.107 It was a third assault, however, which caused the most worry. Theodoret was in Antioch in the spring of 448 when he read an edict against himself. Accusing him of conniving to disturb the orthodox, it confined him to his diocese. Theodoret tapped his contacts to learn what was going on.108 Soon he understood. By summer Dioscorus was denouncing him and eight of his colleagues as heretics.109 The accusations had become a conspiracy to destroy the Antiochenes, with the court ready to go along.

Between April 448 and May 449, Theodoret wrote repeatedly to bishops and courtiers, defending his behavior and teachings. At first, he touted his record of leadership: his asceticism, his benefaction, and his pursuit of heretics.110 He denied wild doctrinal rumors and recited his (orthodox) reading list.111 Later Theodoret produced some full doctrinal arguments. He denounced “one nature” and a “passable divinity.”112 To Disocorus, he made a (seemingly) unequivocal statement: “That I subscribed twice to the Tomes about Nestorius…my own hands bear witness.”113 He also touted his friendship with Cyril and asked colleagues for agape.114 To make countermoves he enlisted Basil of Seleucia and Domnus of Antioch. From others he simply demanded a fair hearing, where he was sure he would prevail.115

Yet by the fall of 448, Theodoret found he was losing ground. Some contacts promised help, above all Anatolius. With the emperor's hostility now clear, most refused to reply. “I have already written two or three letters…without a response,” Theodoret wrote to the Consul Nomus. “Really, I do not know what offense I caused to your Magnificence.”116 Dioscorus sent what Domnus called “a letter that ought never have been written,” threatening Theodoret and all his associates.117 What probably hurt most was colleagues' passivity. Even Domnus merely pleaded with Dioscorus for a return to the status quo ante.118 Theodoret must have realized that he was unlikely to find relief.

Elsewhere actions proceeded against Theodoret's confidants, again with imperial backing. In Tyre, Irenaeus privately worked on his Tragedy. The clerics of Phoenicia I feuded in writing and in the streets, even after Dioscorus consecrated a new metropolitan, Photius of Tyre.119 Meanwhile, the court ordered a new tribunal for Hiba for February 449. For judges, they picked Eustathius of Berytus (enemy of Irenaeus) and Uranius of Himerium (critic of Hiba). As hosting judge they selected Photius of Tyre. Moved twice to avoid mob riots, the hearing took up all the charges against Hiba, and more against his nephew Daniel of Carrhae.120 Daniel “resigned” as expected. But Hiba tried to negotiate. When he promised to condemn Nestorius, restore dissidents, and leave finances to the oikonomoi, the judges accepted his offer.121 The imperial court, however, was unsatisfied. In March Hiba returned home to new riots and written clerical protests. Imperial officials imprisoned and effectively deposed him.122 Thus Dioscorus and his court allies tore at weak links within Theodoret's network.

Theodoret's remaining defenders made one successful counterattack, when court backing seemed within reach. Antiochene supporters (including Basil of Seleucia) met in Constantinople and found a target in Eutyches the archimandrite. In November, he was accused of heresy before the Resident Synod. “Reluctantly,” Bishop Flavian summoned him.123 Pronouncing “one nature after the union,” he was condemned by fifty-three bishops and archimandrites.124 Theodoret responded quickly to the verdict. Domnus led a wintertime delegation to the capital, carrying pleas for the accused.125 At last, it looked as if the court would show balance and reopen Syrian connections.

Yet this opening came to naught; the trial of Eutyches enabled Dioscorus to show the breadth of his doctrinal alliance. Eutyches may have looked theologically maladroit, but he still had clerical and monastic backers.126 They claimed the tribunal had never heard the archimandrite's defense. Flavian sent a transcript to the consistory, which Eutyches' supporters called fraudulent.127 In March, the court summoned an ecumenical council. But right away it signaled new leanings: Theodoret was forbidden to attend.128 Meanwhile, the court vacated rulings against Eutyches, casting suspicion on the judges instead.129 Back in Syria, Theodoret gave up on receiving a hearing. Basil stopped responding to letters. Irenaeus questioned Theodoret's doctrinal resolve; he sent his own agents to make the case. Domnus remained supportive, but given the court's obvious hostility, his expectations seemed naïve.130 Theodoret was not only losing arguments in the palace; he was losing control of his association.

When the Second Council of Ephesus met in August 449, its judgments proved both farcical and telling. Domnus went to Ephesus with twenty-one other Syrian bishops. He then took ill and, after the first session, sat out the proceedings. Most other Syrians were sidelined under suspicion of heresy. Flavian of Constantinople was linked to “diabolical roots,” and forbidden to speak.131 But three Syrian collaborators were given prominent roles (Photius of Tyre, Eustathius of Berytus, and Basil of Seleucia), alongside the prime instigators (Juvenal of Jerusalem and Thalassius of Caesarea). The Syrian archimandrite Barsauma was given a vote to represent “orthodox monks.”132 The first session reviewed Eutyches's trial. After a select reading of the transcripts, attendees rehabilitated Eutyches and affirmed “one nature after the union.” Next, suddenly Flavian was accused of augmenting the Nicene Creed. He could only scream “I appeal” to the papal legate before being dragged from the hall (he died en route to exile).133 Scholars have pondered why so many bishops assented to these actions. Later reports described a threatening climate: attendees told to sign blank pages, cowering from soldiers wielding clubs.134 But the extant acta preserve none of this. Dioscorus may have manipulated the records. But he had already declared his preferences and demonstrated imperial backing. The passivity of attending bishops may have been genuine.

In any case, the opening session was just a prelude to the main event: the gutting of Theodoret's network. First, witnesses reported the judgments and acclamations against Hiba. Amid murderous shouts the council condemned him and ordered his wealth seized.135 Next, Daniel of Carrhae was excommunicated for immorality and embezzlement (he had already resigned).136 Irenaeus was again condemned, along with his appointee Aquilinus.137 Sophronius of Constantina was denounced for sorcery, his fate left up to a new metropolitan of Edessa.138 Then came the attack on Theodoret. Syrian priests told stories of hidden meetings, where recruits were forced to read pagan philosophy and sign secret creeds. This was followed by a (generally accurate) synopsis of Theodoret's teaching. Dioscorus asked for his condemnation and all the Syrian attendees seem to have complied.139 The council paused to reinstate bishops purportedly deposed by Theodoret.140 Finally Domnus was himself indicted, as a collaborator in Theodoret's machinations.141 These charges may seem absurd but they show an underlying logic. Dioscorus staged a pageant of Antiochene heresy and criminality. Through guilt by association, he neutralized the core Antiochene network.

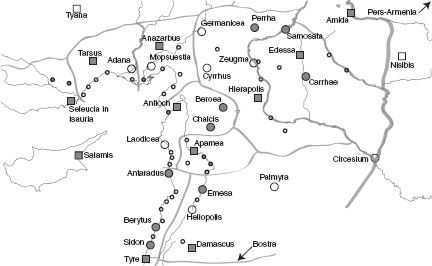

As Dioscorus attacked the Antiochenes, he crafted a replacement network. Before the council he linked dissident Syrian clerics with distant sympathizers. By the summer of 449 he had two defectors and a new metropolitan.142 In Ephesus Dioscorus showcased his new clerical allies (witnesses and plaintiffs). He found more new allies by replacing accused bishops with their local rivals. Major sees, however, he saved for his confidants. Constantinople went to Anatolius, Dioscorus's archdeacon. Antioch was given to Maximus, probably the priest who had served as Cyril's proxenos. By mid-450, most of Theodoret's inner circle was bound for exile (Theodoret to his old monastery in Nicertae). Those who remained largely acquiesced to the new setup (see figure 17). And Theodosius II expressed his support.143

Thus Dioscorus, with imperial backing, carried out a new ecclesiastical coup. Over eighteen months Theodoret's social and rhetorical efforts were undone. The anti-Antiochenes sequentially targeted Theodoret and his confidants. Some they accused and deposed, others they pressured to realign. In either case they mixed accusations of heresy with criminal charges, to reveal a dark conspiracy. The new coalition also targeted Antiochene social practices. Naming an archimandrite as voting representative altered Antiochene ascetic relations. Defending local candidates challenged Antiochene modes of recruitment. Obviously Dioscorus and his allies assaulted Antiochene doctrine. “Two natures after the incarnation” was declared Nestorian heresy. Books by Diodore, Theodore, Theodoret, and Hiba were ordered burned.144 Even Antiochene patterns of informal leadership came under attack. The Second Council of Ephesus set up orderly patriarchates. Half of Syria now officially answered to Jerusalem and half to Antioch. Most of the old Antiochene periphery probably escaped direct harm. But as patriarchs applied a new orthodoxy, they had little choice but to comply. None of this was purely Dioscorus's doing. Repeatedly officials signaled the emperor's will. Dioscorus simply built his coalition and seized the opportunity to efface Theodoret's whole network.

FIGURE 17. Map of Dioscorus's new Syrian network, 449-450, according to letters and conciliar records. Filled shapes = bishops in Dioscorus's coalition, empty shapes = dyophysite holdouts or unknown bishops.

AN AUTOPSY OF THE ANTIOCHENE NETWORK

The collapse of Theodoret's network complicates our understanding of his leadership and community. On the one hand, Theodoret's writings present a robust association with powerful allies, an informal leadership, and a developing sense of identity. On the other hand, conciliar records depict a doctrinal clique, surrounded by hostile clerics and monks and, when challenged, liable to crumble. There are several ways to interpret the contradictory sources. One could view Theodoret's network as robust until it was overthrown. One could also view the network as a representation, which proved illusory. There is, however, a more nuanced possibility, tied to the social patterns that this book has traced. Modular scale-free networks may be robust, but still be susceptible to collapse, all while limiting core members' perception of the peril.

The records of the Eutychean controversy shine a stark light on the network that Theodoret tried to forge. Sometimes the records support his picture of relations. Most of his intimate correspondents are confirmed as close allies, when they appear as Dioscorus' targets (or as featured defectors). But often the sources do not align. The acta reveal dissenting clerics, and local tensions, that Theodoret never acknowledged. In letters, Theodoret claimed to represent a broad, orthodox clergy. Dioscorus presented him as commanding a small heretical cabal. How far did Theodoret's teachings and attitudes extend to the rest of the Syrian clergy? By 450, few stood up on his behalf. Even before the controversy his support may have been weaker than he let on.

How then, should we view the Antiochene network and Theodoret's leadership? One approach would be to try to harmonize the contrasting sources. Theodoret's network could have been as robust and popular as he suggested, until opponents tore it apart. By 440, Theodoret had proven effective as a defender and mediator. His centrality within the network gave him standing to advance his program (recruitment, doctrine, heritage, and communal identity). Theodoret's texts remained popular long after his condemnation. It seems unlikely this following was invented out of whole cloth. Theodoret's influence may be gauged from what it took to get rid of him: a year of accusations, assaults on his subordinates, a highly controlled council, and hostile signals from the emperor. When Basil of Seleucia abandoned Theodoret, the abruptness of his decision indicates a network in the process of being conquered.

A second approach would be to treat the sources as social representations. Theodoret's network could have been an illusion of his pen, which dissolves when viewed through different writings. Theodoret presented himself as an accepted clerical leader. Beyond his inner circle, however, his contacts may have been unreliable. Lay officials ignored his pleas. Some monasteries embraced his opponents. His favorite ascetics never demonstrated on his behalf. Theodoret's multilingual efforts won him few allies in Armenia. Among Syriac writers it was Rabbula who claimed the most respect. Centuries later, even the Church of the East paid little attention to Theodoret (or Hiba).145 Theodoret's leadership performance faced stark limits amid the deepening of the church hierarchy. By the 440s, patriarchs seemed useful both to courtiers (who had fewer prelates to worry about) and to clerics (who had clear lines of appeal). Theodoret had personal influence with Domnus, Hiba, and Basil. Records reveal little deference from other bishops. The number of Syrian supporters won over by Dioscorus suggests an Antiochene community that was rather hollow.

Between these two approaches, however, lies a more nuanced perspective, based on the relational patterns that this book has outlined. Theodoret's group could have seemed cohesive to its leaders but still be vulnerable to collapse. Throughout this book we have found a general Antiochene social pattern, a modular scale-free topology. Networks of this form are generally robust in computer simulations.146 They survive the loss of random members (which in our case might mean by death or by defection). Modular, scale-free networks can be dissolved, however, if some force simultaneously removes most of the hubs. In 449 and 450, we see just such a force, led by Dioscorus and his imperial backers. The result was a cascade failure, which could occur even if Theodoret's relationships were intersubjectively “real.”

In fact, Theodoret may not have understood his network's vulnerability; for the shape of social relations might have distorted his perception. In chapter 2, we mapped a tight Antiochene core surrounding five main hubs. We also mapped a segmented and spotty periphery. After 436, Theodoret worked to extend his network and maintain a tight inner circle, which reinforced this basic social arrangement. At the core, Theodoret was surrounded by Antiochene cues. It was feasible for him to assemble these signals into an Antiochene identity. Core allies probably shared enough of his stories and teachings to create the impression of a nascent community. Social experiences must have differed on the periphery. There Antiochene cues were rarer, emerging from a narrow central clique. Syrian dissidents must have felt out of the loop, and thus complained to Dioscorus. Hearing such complaints, he could easily imagine a heretical conspiracy.

This autopsy is, of course, premature. A year after the Second Council of Ephesus, Dioscorus's miaphysite order began to falter. First Pope Leo took up the cause of some victims of Ephesus (especially Flavian of Constantinople). A few courtiers may have been receptive.147 Then in July 450, Theodosius II dropped dead. The new regime of Marcian and Pulcheria vacated conciliar rulings of the previous summer.148 Theodoret and Hiba both returned to their sees. Other Syrian bishops hailed their return, including some defectors.149 By the summer of 451 it was Dioscorus facing the threat of exile.

It is, in fact, easy to lose perspective in the study of church disputes. These conflicts were largely directed by a few hundred active participants. Doctrinal networks of lay patrons, clerics, and monks could crumble under pressure, especially from the imperial court. And then, beyond the church leadership lay the rest of late Roman society, whose relations with clerics are the focus of the next few chapters. As we shall see, the course of the Christological dispute depended significantly on that outside world.