3

Roots of a Network

Theodoret on the Antiochene Clerical Heritage

By all rights the spring of 448 should have been joyous for Theodoret. The season marked his twenty-fifth year as bishop and the eighth of relative calm in the church. Theodoret had recently completed a commentary on Paul's Epistles and a Christological dialogue. He could look forward to preaching in Antioch on these topics during his usual visit. The news of the season, however, put a damper on his routine. First came old accusations against allies, then an imperial letter relegating him to his diocese.1 By the summer he was being called a crypto-Nestorian tyrant, with worse to come.

As confrontations intensified, other bishops of Syria reported to Theodoret to ask for advice. Domnus of Antioch, Theodoret's protege, mentioned one source of hope: the emperor had called an ecumenical council. Theodoret, however, knew about past church struggles, when synods were no panacea. “Even at the great Council of Nicaea,” he recalled, “the Arians voted with the Orthodox and swore by the apostolic creed.” Emperors, in particular, had not always been reliable. Constantius II and Valens had compelled church leaders to compromise, deepening schisms and hindering proper faith. Luckily, the old struggles left another source of hope: crafty Syrian bishops. In the fourth century, he suggested, their ingenuity had saved Christian orthodoxy. Theodoret advised Domnus to gather “the most God-friendly, like-minded bishops,” for a prolonged fight.2 While his allies organized, however, Theodoret looked to the past for grounding. By the end of 449 he had turned his reflections into five books of church history.3

In the study of the Antiochene network, Theodoret's Church History (Historia ecclesiastica or HE) represents an inescapable text, for his narrative confronts the figures and events that shaped the fifth-century clerical world. His work was (most likely) the third church history written in the 440s. Socrates (between 438 and 443) and Sozomen (in 443 or 444) had already given their (Constantinople-centered) takes on the triumph of Nicene Orthodoxy.4 Prior work by Rufinus of Aquileia and non-Nicene historians5 had also found distribution. But Theodoret was unsatisfied; he needed to cover the “episodes of church history hitherto omitted.” Theodoret played off existing historical and doctrinal writings.6 He continually referenced his own History of the Friends of God (Historia religiosa, or HR) so that it would be read alongside the HE. He furnished prosopographic detail as he anointed new (mostly Syrian) honorees.7 But more than an addendum, he offered a narrative thesis. Amid Trinitarian conflicts in Syria, especially in Antioch, Theodoret found the roots of his Nicene community. He sketched out its founders, supporters of Bishop Meletius, as they built a clerical party. He related how this party forged alliances and took the church back from heresy. Nicene victory owed something to emperors, he claimed, but it depended on past Syrian bishops.

This chapter evaluates the heritage that Theodoret depicted for his network. It traces Theodoret's account of his heroic predecessors and compares it to other historical sources. Theodoret wrote his narratives with definite purposes. He extolled Syria's orthodox pedigree, as he defended the symbols of his network. Theodoret's account is coherent and well informed. It helps to make sense of two important developments—the formation of Antiochene doctrine and the transformation of Syrian monasticism—as well as of traditions of informal clerical leadership. Other sources add (unpleasant) nuances to Theodoret's account without challenging its basic claims. In context, this history reveals some of the roots of the Antiochene scene.

THEODORET ON THE TROUBLES OF THE

FOURTH-CENTURY CLERGY

Theodoret's account of the origins of his network began with a cry of sympathy. From the vantage point of the 440s, bishops of the fourth century seemed uncomfortably constrained. Part of this perception stemmed from decades of Christian growth. Theodoret was writing about bishops with smaller congregations and fewer resources. Part also came from changes in clerical authority. Theodoret and his peers expected life-long tenure, but fourth-century bishops were frequently unable to control their sees.

Theodoret's Church History, like the narratives of his contemporaries, centered on the Trinitarian controversy. And by the 360s, for a Nicene, the tale was getting depressing. Churches of the Roman East were growing more divided. Disputes and factions had been fluid until the 350s, but after 360, those with Nicene leanings were marginalized. Theodoret, of course, understood the phenomenon of doctrinal parties, the unstable coalitions that signed to common-denominator formulas and labeled one another as heretical. In the fourth century, the emperors' push for compromise helped to distinguish at least four such parties: the “Homoians” (who claimed that the Son was “similar” to the Father), the “Homoiousians” (who asserted that the Son was “similar in substance” to the Father), and the “Anomoians” (who held that the Son was “dissimilar” from the Father), as well as the “Nicenes.” The Homoians took up most of Theodoret's annoyance, for they claimed imperial favor and controlled the most churches. They also taunted Nicene Christians for having a creed that was supposedly un-scriptural.8 Late in his reign, Constantius II enforced his preferences by exiling recalcitrant bishops. After 368 Valens did likewise.9 But court favor was not the only problem. For no imperial meddling caused the split in Laodicea between two circles of Nicenes.10 In any case, Theodoret recorded the frustrating implications. By the 370s every major town in Syria hosted multiple claimants to episcopal office, unable to exercise their full charge.

Theodoret's HE did not hide the troubles of fourth-century clerics. In fact, it used these troubles to showcase church heroes who somehow, when faced with adversity, kept their nerve. One of Theodoret's favorites was Eusebius of Samosata, who defied emperors in the 360s to consecrate Nicene bishops. When Valens exiled him in 369, he supposedly told his flock not to resist, since “the apostolic law clearly instructs us to be subject to [civil] powers and authorities.” So beloved was Eusebius by his congregants, we are told, that two replacements failed to pacify them.11 But even Theodoret knew that such honor was cold comfort to the exiled.

It was in this context that Theodoret turned to Antioch. All the troubles that plagued the church in the 360s piled up there. One bishop, Euzoius, usually had the support of the imperial court. A former priest from Egypt elected in 361, he clearly leaned Homoian. Meanwhile, two figures claimed the office under a Nicene banner: Paulinus and Meletius. Meletius had been a bishop in Roman Armenia. He was transferred to Antioch in 360 under a compromise between Homoian and Nicene bishops.12 He was then deposed a few months later when his own (cryptic) doctrinal views came to light.13 In 363 he declared his support for the Council of Nicaea, though Theodoret found signs of his prior loyalty.14 Nevertheless, he had risen with the help of known anti-Nicenes. These links, coupled with his hesitancy to dogmatize, raised suspicions.15 Paulinus, meanwhile, was an aged priest, who had been ordained by Eustathius of Antioch, the heroic Nicene confessor. Longtime leader of a separate “Eustathian” faction, Paulinus secured consecration in 363 from Roman Westerners who had come to survey the local Nicenes.16 Eventually a fourth candidate was added. Vitalis, a priest under Meletius, was induced to break away and then consecrated by Apollinarius, the theologian-bishop of Laodicea.17 Thus, Theodoret presents a confused competition for episcopal authority, in which most of the claimants considered themselves Nicene. As scholars have noted before, the result was instability.18 Under Emperors Julian and Jovian, and initially under Valens, each of the three (not yet four) bishops controlled a subset of the personnel and churches. Each claimed external allies. None commanded universal regard within Syria or beyond. When Valens moved to Antioch in 370, Meletius was forced into exile (Vitalis was not yet consecrated, and Paulinus, not worth the bother).19 Nonetheless, all claimants maintained local followings. Some even benefited from exile. After all, it was exile that bound Meletius to his biggest booster, Basil of Caesarea.20

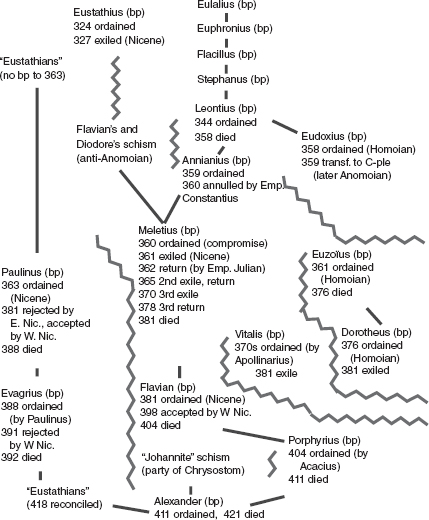

At the same time, as Theodoret's account makes clear, the party balance could not erase the fear of factional disintegration. A few years earlier, in 358, the death of Bishop Leontius had turned the local clergy upside down. At that time, Eudoxius, hitherto bishop of Germanicea, came to claim Antioch for himself. He then ordained Aetius and Eunomius, who advanced an Anomoian doctrine that the other clerics reviled. The situation grew more confusing when repeated councils failed to choose a candidate acceptable to the emperor. In fact, it was because of this overall upheaval that Meletius had been chosen in the first place.21 A kind of equilibrium returned under Emperor Julian, who had equal disregard for all clerical parties.22 Still, one death had upended the factional balance, and a second one could do it again (see figure 7).

What Theodoret found lacking in Antioch and Syria of the 360s was a system of inter-see cooperation. Factionalism and rivalry hobbled church leadership. In some places (like Egypt) disputes were centralized, thanks to one bishop's primacy. But Syria lacked such a tradition, as Theodoret knew.23 This absence of oversight created a more open episcopate. Any would-be bishop could find the two or three consecrators he effectively needed.24 Once bishops were chosen, however, this openness held no benefit. For no bishop-claimant could ensure a heritable episcopate.

THEODORET ON THE TRIUMPH OF

MELETIUS'S NICENE PARTISANS

Then something changed. Starting in the 360s Theodoret found an assembling Nicene network, even in Antioch. Most leaders of this coalition were known from other histories. But Theodoret had his own tale to tell. In his judgment, it was the following of Meletius that led the Nicene triumph by taking over the Syrian episcopate.

At first this sort of triumph looked unlikely. By the 370s Meletius's authority was weakening. The Homoian party held Valens's support. They controlled the urban churches, relegating the Nicenes to an “army training ground.”25 The Homoians even managed an orderly succession when Euzoius passed away.26 As Meletius languished in exile, only his close supporters paid him attention.27 However, according to Theodoret, Meletius had a hidden advantage: two gifted partisans named Flavian and Diodore.

FIGURE 7. Episcopal factions in Antioch, 325-421, according to Theodoret's HE. Solid lines = partisan episcopal succession, broken lines = schisms.

By the 360s Flavian and Diodore had already made names for themselves as lay patrons of the church. Even before Meletius arrived, both had demonstrated Nicene ardor, protesting Bishop Leontius and his “attacks against the faith.”28 Famously they excelled in preaching and argument, a talent nourished through rhetorical education. Similarly they claimed crowd-control skills. Theodoret credited the pair with inventing the antiphonal chant, which they let loose in prayer meetings, on the streets, and even in Leontius's churches.29 So strong was their following, we hear, that Leontius “did not think it safe to get in their way.”30 In 360 Meletius ordained Flavian and Diodore, but it was after his first exile that they came into their own. By 370 Flavian was serving as a proxy prelate, with Diodore at his side. Diodore researched arguments, we are told, while Flavian preached them to the crowds. This cooperation reportedly proved successful, despite Diodore's own departure (probably in 372).31 Paulinus and Apollinarius were reportedly out-argued, and the “blasphemy of Arius” started to lose ground.32

Still, Flavian and Diodore succeeded, in Theodoret's judgment, as much because of their holy connections as their talents. Unlike other church historians, Theodoret drew no new attention to the asketerion, Diodore's schoolhouse for scriptural study and disciplined living.33 Rather, he showcased Flavian and Diodore's ties to hermits and archimandrites. Such friends made good agents of persuasion at court. Theodoret noted, for example, how the hermit Aphraates rebuked an emperor face to face “for having cast these flames [of Arianism] upon the divine house.”34 Hermits also supplied their marvelous reputations. Julian Saba, we hear, won over the Nicenes with well-timed miracles of healing, including one for the count of the East.35 This was “proof” of divine support that no party could deny. By the 370s, Theodoret claimed, Meletius's partisans were assembling a legion of ascetic allies.36 This marked a turn of the tide.

According to Theodoret, this ascetic alliance was led by a new partisan, Acacius. A monk from a village near Antioch, Acacius was recognized for his ascetic regimen. While some monks treasured isolation, Acacius was more hospitable, accepting visitors with an open door.37 But Theodoret cared less about his manners than his connections—to the monastic circle of Julian Saba.38 According to Theodoret, Acacius befriended Flavian and Diodore in the 360s. Then he touted Meletius's cause to Julian Saba and his followers as “a way to serve God much more so than” in their caves.39 Thanks to Acacius's travels Julian Saba, Aphraates, and their admirers filled the city. Needless to say, this made Meletius's partisans harder to ignore. Theodoret even suggests that cooperation proceeded with Ephrem, the Syriac hymn-writing deacon of Edessa, known to Greek-readers as a monastic leader.40 Thus Theodoret depicted a monastic legion that spanned Syria's physical and linguistic landscape (see figure 8).

Between Flavian's preaching, Diodore's teaching, and Acacius's holy friends, Theodoret found his regional forebears gaining in popularity. He presented Meletius's faction as victorious, even before the court sided with the Nicenes. The new emperors Gratian and Theodosius, of course, did approve Meletius's return.41 By Theodoret's account, the choice was providential: Theodosius had a dream in which Meletius crowned him and gave him the imperial robes.42 In the Church History, this was a unique note of triumph. Many bishops were perseverant, but only Meletius appeared in imperial dreams.

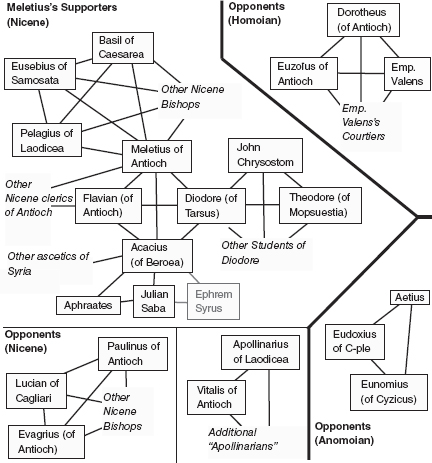

FIGURE 8. Meletius of Antioch's supporters and opponents, 360-378, according to Theodoret's HE. Note: Ephrem Syrus's link to the Antiochenes is only implied.

At this point, we are told, Meletius chose to show magnanimity. In 380 Theodosius declared his support for the Council of Nicaea. He sent a delegation to Antioch to endorse one Nicene claimant.43 Hence Meletius approached his rival Paulinus with a proposal. He offered to treat Paulinus as a colleague and link congregations, if it was agreed that whichever claimant died first would bequeath sole episcopacy to the other.44 Reports vary as to the response. Socrates and Sozomen asserted that the offer was accepted.45 Theodoret claimed that Paulinus refused. But even Theodoret could not deny the detente.46 Meletius took hold of his old churches but respected Paulinus's following. Readers of Socrates would know that Meletius left for Constantinople, “because of the state of the church in Antioch,”47 and Theodoret did not refute the point. But as Theodoret explained, what Meletius got in return was grand: deference to his leadership in Nicene councils48 and acceptance of his ordinations in sees left “vacated” by the conflict. By 379 Meletius had placed Diodore in Tarsus and Acacius in Beroea. With imperial permission and help from Eusebius of Samosata, he put up candidates in Chalcis, Hierapolis, Apamea, Edessa, Carrhae, Doliche, and Cyrrhus.49 These actions built up a Nicene presence in Syria. They also allowed Meletius's party to perpetuate itself.

When Meletius died in 381,50 he had just started as president of the Council of Constantinople, and it was this gathering that began a second phase in the triumph of his party. For months Meletius had been preparing for the gathering; his passing brought disarray. First, the presidency was accorded to Gregory of Nazianzus. Gregory may have wanted to declare Paulinus the recognized episcopal heir. But luckily for Meletius's partisans he was persuaded to leave his position.51 The next president, Nectarius, proved more pliant. A longtime friend to Diodore and Meletius anyway,52 Nectarius accepted a request for delay. Then, after the council the Meletian bishops gathered in Antioch, where they put up Flavian for election. Consecrated by Diodore and Acacius, he soon received Nectarius's blessing.53 Paulinus was upset, as were critics of Nectarius. Together they complained to western bishops, who took the message to the emperors.54 Theodosius I called a new meeting in the capital. To Paulinus's disappointment, however, it confirmed both Nectarius and Flavian (it was, after all, filled with Meletius's friends).55 This episode did not flatter Meletius's followers. Theodoret minimized the embarrassment by distancing his account of Flavian's ordination from his treatment of the council. Nevertheless, he acknowledged that Meletius's partisans pushed their rivals aside (see figure 9).

Still, the dispute with Paulinus continued and could not be ignored. After the councils Paulinus convinced the bishops of Italy and Egypt that he was the rightful prelate. In 388 he chose his own successor, Evagrius. And despite this non-traditional election Evagrius was embraced by the same set of colleagues. Theodoret seized upon Evagrius's ordination as a point of polemic. “[The apostles] did not allow a dying bishop to ordain another to take his place,” he declared, “and they ordered all the bishops of the province to convene.”56 Even at the time supporters of Paulinus's party questioned Evagrius's status. In 391, a council of Italian bishops sided against Evagrius's claim. The dispute, however, had left an impression. Many Nicene bishops gave Flavian the cold shoulder, and the court threatened to intervene. It was only in 398 that he won belated acceptance. Even this took the support of the court, the oratory of John Chrysostom, and more visits by Acacius.57 Theodoret could not deny this opposition, so he turned the affair into a test of character. According to Theodoret, Flavian met criticism by offering to abdicate in front of the emperor, a show of selflessness that impressed his majesty. In any case, Theodoret noted that Flavian was held in high regard within Syria (not surprising given Meletius's appointments).58 Paulinus's followers held out until the 410s,59 but Theodoret made it clear that Syria was in the hands of the proper Nicene party.

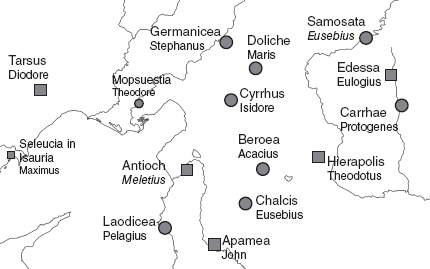

FIGURE 9. Map of Meletius's episcopal appointments, 378-381, according to Theodoret's HE, including appointments made by Meletius's ally, Eusebius of Samosata. Smaller shapes = additional appointments by Meletius's main allies, 381-393.

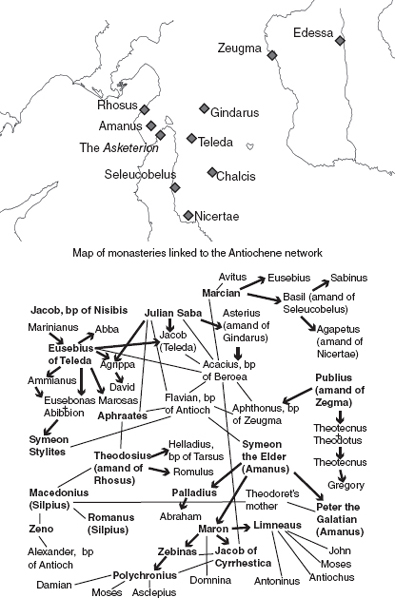

As to the significance of these episodes, Theodoret left little doubt: Meletius had launched a coup in the churches of Syria, extended by the machinations of his followers. It was, however, the long-term impact of these events that most concerned Theodoret. First, the rise of the Meletian party led to a more cooperative regional episcopate. Thanks to Meletius and Eusebius many Syrian bishops of the 380s claimed the same spiritual fathers. Theodoret credited these associates with unusual fidelity. Second, according to Theodoret, Meletius and his partisans stabilized episcopal selection. Like other church historians, Theodoret mentioned Diodore's students who became bishops, in particular John Chrysostom and Theodore of Mopsuestia.60 He then listed many more bishops tied to Meletius and his following.61 Third, according to Theodoret, Meletius and his proteges turned ascetic links to their advantage. As ascetics aided bishops in various causes,62 bishops encouraged ascetics to found monasteries. In the HR Theodoret cited monastic groups that owed goodwill to Flavian, Diodore, and Acacius (see figure 10). Together these arrangements constituted a potent “Antiochene” legacy. For by the 420s they had fostered a network of clerics and ascetics, headed by a clique of bishops.63

FIGURE 10. Ascetics and monasteries linked to the Antiochenes, 381-423, according to Theodoret's HE and HR. Thick arrows = mentorship links, thin lines = informal links, names in boldface = subjects of chapters of the HR.

Theodoret ended his HE in the late 420s with the deaths of Theodore and Theodotus of Antioch, as well as Polychronius of Apamea (Theodore's brother). Thus he confined his story to the rise of his Antiochene mentors. Theodoret's account, of course, cannot be simply accepted at face value. Nevertheless, it opens a window on the origins of his clerical community. Not only does it supply prosopography; it contextualizes several developments in Syrian Christianity. One of these has received limited attention: the peculiar distribution of authority among Syrian bishops. Another has been treated as part of a general trend: the establishment of coenobitic monasteries. This chapter will discuss both of these issues. First, however, let us consider a development that has long fascinated scholars: the formation of a “school” of doctrine.

“ARROWS OF INTELLIGENCE”: ANTIOCHENE

DOCTRINE IN CONTEXT

Theodoret's HE reserved a special place for his favorite teachers. Diodore he called “a great clear river,” which overwhelmed the heretics of his day. Like many Nicene leaders, “He thought nothing of the brilliance of his birth, gladly enduring difficulty on behalf of the faith.” But Diodore was no mere confessor. “At that time, he did not speak publicly in church gatherings, but provided an abundance of arguments and scriptural thoughts to the preachers. They in turn aimed their bows at the blasphemy of Arius, while he brought forth arrows from his intelligence as if from a quiver.” His skills were such that he tore through heretical arguments as if they were “mere spider's webs.”64 Theodoret's affirmation of Theodore was just as pronounced. The final chapter of the HE called Theodore a “doctor of the whole church,” who, after receiving the “spiritual streams” of Diodore, spent his episcopacy “battling the phalanx of Arius and Eunomius and struggling against the pirate-band of Apollinarius.”65 For Theodoret to praise these two men was hardly unexpected. He had already published In Defense of Diodore and Theodore, an apology for their orthodoxy. The HE, however, gave context to the work of these two authors. It assigned them the role of a theological research operation, a veritable “school of Antioch.”

Theodoret's descriptions of Diodore and Theodore are intriguing because they give flesh to a hotly debated scholarly construct. The “School of Antioch,” we recall, refers to the nexus of religious learning marked by four tropes: the “literal-historical” method of exegesis, the rejection of “allegory,” the citing of “types” and “realities,” and the distinction of Christ's divinity and humanity.66 Scholars have differed over the meaning of these tropes. Many have searched for a system of thought behind Antiochene teachings.67 Others, frustrated by shifting terms and lost texts, settled for Antiochene “tendencies.”68 Some looked for a lineage of teachers. 69 Others proposed broad cultural influences, from Aristotelian or Platonic philosophy to Jewish or Syriac modes of reading.70 Thus scholars wrote many studies of doctrinal texts but they gave only vague explanations for the overall trend.

Recent research has reevaluated the Antiochene doctrinal phenomenon. Scholars now emphasize the similarity of Antiochene and Alexandrian exegesis.71 They also challenge the notion of an Antiochene system, though most still acknowledge common concerns.72 Some have situated Antiochene doctrine within a narrow cultural context: Greek sophistic education in Antioch.73 Others have found inconsistencies between Greek and Syriac versions of Antiochene texts, enough to cast doubt on Diodore's and Theodore's positions.74 Much of this reevaluation has been persuasive. Diodore, Theodore, and Theodoret did not share a coherent doctrinal system. The effect of recent studies, though, has been to minimize the Antiochene “school.”75 Diodore and Theodore did have influence in Syria; in the 430s seventy-five bishops risked exile to defend them.76 Perhaps the deconstruction of the school of Antioch has gone too far.

At this stage Theodoret's account comes in handy; for his HE envisions a different kind of school. It does not present a doctrinal abstraction or an autonomous institution. It describes a loose educational circle, led by Diodore and then Theodore, which formed part of the larger partisan effort. What we know of early Antiochene doctrine fits within the context that Theodoret provides. Not only do these teachings reflect the culture of late-fourth-century Antioch; they seem custom-made to reinforce the participants' friendships and enmities.

At the widest level, Antiochene teaching fit well with the mix of doctrinal parties that Theodoret highlighted in Syria during the later fourth century. By the 360s Christians had been openly feuding about the Trinity for half a century. The fluidity of prior debates (of which Meletius, Flavian, and Diodore had partaken)77 was passing; positions were becoming better articulated. In the Nicene party the Cappadocian fathers offered their vocabulary of hypostases and ousiai, for which they slowly won support. (Meletius, in fact, embraced their terminology early on and, as Theodoret noted, well before Paulinus).78 The Cappadocian vocabulary scarcely ended the controversy, but for Nicenes it drew clearer lines between orthodoxy and heresy. Yet settling one question opened others. Nicenes had to deal with inconsistent past authorities. The third-century scholar Origen, for instance, had faced prior controversy, but the new terminology sharpened concerns about his orthodoxy. More pressing than Origen, though, was the Nicenes' basic evidentiary problem: ousia and hypostasis had no scriptural precedent. In fact, biblical quotations could more easily undercut the Nicene position than defend it. Homoians hit upon this, chanting gospel lines, such as “My Father is greater than I” (John 14:28). Nicenes labeled the Homoians as “Arian,” but they still had to meet these challenges with a public response.

In the 360s Diodore took up the defense of Nicaea against the Homoians. The fragments attributed to him show that he traced out an immense doctrinal project: the creation of harmony between Scripture, Cappadocian terminology, and Nicaea's supporting authors. This task involved cross-referencing, lexical analysis, etymological research, and narrative summation, all familiar activities to former students of sophists. It was as part of this project that Diodore employed those tropes associated with the school of Antioch. When it came to describing Christ, he spoke of two “voices,” a human and a divine, to which passages of Scripture might refer.79 Initially he called the two aspects by the biblical epithets, “Son of David” and “Son of God,”80 or the “Word” (logos) and the “flesh”(sarx).81 His students abandoned “sons” and “logos-sarx” in favor of “natures,” but they still stressed the distinction between divinity and humanity.82 Inspiration for this terminology has been variously located, but whatever the roots, the proximate cause was public controversy. By assigning some scriptural lines to the human and some to the divine, Diodore found an answer to the Homoians' taunts.

It was exegetical tropes, however, that seem to have marked Diodore's firmest response. By building up from the “literal” to the “historical,” he aimed to approach the hypothesis of biblical texts—their moral and narrative significance.83 Diodore's rejection of certain tropes as “allegory” was the natural extension of discerning what fell outside Scripture's underlying message. This approach may have proved too limiting for some contemporaries, but it gave Diodore a rhetorical edge. Homoians might claim the words of Scripture, but Diodore claimed a deeper connection to the narrative.

Diodore's doctrinal and exegetical tropes thus make sense as an effort to distinguish his party from its rivals, the Homoians. They similarly aimed for separation from another set of foes, the Anomoians. Theodoret informs us that Diodore had been particularly hostile to “dissimilar” formulas, even before joining Meletius's following.84 Aetius and Eunomius lost episcopal sponsorship in Antioch in 360, but they maintained a Syrian following. This group developed its own style of doctrinal production, based on Scripture and on dialectical reasoning. By the 380s its members were challenging Nicenes such as Chrysostom to take up their favorite lines of argument.85 Evidence suggests a general disdain for the Anomoians within the clergy, but the Anomoians' claim to exact reasoning caused problems for all the other clerical parties.

The Antiochenes' response to the Anomoians was as thorough as their response to the Homoians: they outdid their opponents' claims to systematic logic. Diodore was famous for his efforts to create a consistent language of theology, linking the words of Jesus, biblical narrative, and common parlance. Theodore extended this drive, even rejecting some of his teacher's favored terms. And yet, Diodore and Theodore claimed to avoid un-scriptural speculation. This they did by displaying long years of scriptural learning, to contrast with the supposedly ill-grounded reasoning of Aetius and Eunomius.86 In other words, they claimed superior paideia, like the sophists who had trained them. The assertion of deeper learning was more rhetorical than substantive. Nonetheless, the Antiochenes took it seriously. They seem to have levied this claim against Paulinus, whom Theodoret, at least, viewed as a simpleton.87 They may also have levied it against Nicenes in Egypt. Antiochenes worried about Alexandria-style allegory partly because it opened scriptural interpretation to any logician's schemes.

By the 380s, it was not Homoians or Anomoians who most troubled Diodore and Theodore; it was the (Nicene) followers of Apollinarius. Son of a grammarian turned priest in Laodicea, Apollinarius distinguished himself by writing dialogues in defense of the Christian faith. By all accounts he had a fondness for Neoplatonic philosophers. Yet it was apparently Apollinarius's friendship to the Nicene hero Athanasius that inspired the bishop of Laodicea to excommunicate him in the 360s.88 By Sozomen's reckoning, Apollinarius began crafting his defense of Nicene doctrine at this time,89 contemporary with Diodore's efforts. Indeed, he responded to many of the same opponents. Apollinarius's doctrinal solutions differed from Diodore's. His Christology asserted that God the Word had united with Jesus's humanity by taking the place of the “mind” (Greek: nous). Yet much like Diodore, he sought a quick response to rhetorical challenges. He thus compiled a set of reduced formulas to signal orthodoxy, such as “one nature of the divine incarnate Word.”90 Until the mid 370s Apollinarius and Diodore seem to have tolerated each other. Then a rivalry developed, resulting in the ordination of Vitalis. Apollinarius was condemned and deposed in 381, in part at the urging of Meletius. According to Theodoret, however, Apollinarius claimed secret followers for at least another forty years, infiltrating the Nicene church with their hidden “unsoundness.”91

The Antiochene response to Apollinarius was more than a mere rhetorical targeting. Diodore and Theodore turned Apollinarians into their favorite bete noire. Like the Cappadocians, Theodore took aim at the “incomplete humanity” of Apollinarius's Christ. But he was also troubled by the phrase “one nature.”92 His “two natures” was probably a response to the Laodicean bishop's formulation. By the early fifth century, Apollinarius's formulas had receded from the discourse; it was enough to label someone as Apollinarian. A follower of Theodore's, Alexander of Hierapolis, later recalled how he and several colleagues threatened to resign unless suspected Apollinarians were excluded from the clergy.93 In a sense, nothing came to mark Antiochene inclusion more than the exclusion of “Apollinarians.”

The doctrinal tropes of Diodore's circle can thus be seen as a response to the rivalries that formed around them during the 360s and 370s. Theodoret suggested that his forebears were more concerned with Homoians, Anomoians, and Apollinarians than they were with Egyptians. His suggestion makes sense given the Antiochenes' social circumstances. Meletius's following needed to distinguish itself from opponents and build a sense of certainty. So Diodore provided socio-doctrinal cues to mark out orthodoxy, first in contrast to Anomoians and Homoians, and then in opposition to Apollinarius. It was the need for sequential triangulation that in part led clerics to assemble the most familiar Antiochene doctrines.

And yet, early Antiochene teaching (insofar as we can discern it) did more than trace out the boundaries of orthodoxy. It also affirmed the friendships and patronage ties which, according to Theodoret, formed Meletius's network. As the Trinitarian feuds developed in the 360s and 370s, all parties organized alliances. Nicenes across the empire communicated and, in some cases, coordinated efforts. Yet building such alliances was not easy. Not only did clerics compete for authority, they also faced the prospect of doctrinal disharmony. Where some Nicenes favored “eternal generation of the Son,” for instance, others preferred God's “begetting before all time.”94 The more clerics scrutinized one another's teachings, the more they risked disagreement. To avoid these dangers Nicenes tended to seek general formulas on which they could agree: the equal trinity, or later one ousia in three hypostases. But this broad alliance depended on distance. For closer cooperation clerics needed more specific terms of agreement. According to Theodoret, Meletius's following included preachers, teachers, lay leaders, and noted ascetics. Whatever Diodore taught would have to meet their general approval.

Diodore's teachings appear custom-made to affirm the social attachments that, according to Theodoret, were developing around him. One such affirmation involved the collaboration of preachers and teachers. According to Theodoret, Diodore worked in the background, providing “scriptural thoughts,” to support Flavian's public presentations. In fact, Diodore's efforts could help greatly. His commentaries formed sourcebooks of quotations and observations, geared to counter the Homoians and other foes. Flavian could turn to these commentaries to craft stirring sermons and dramatic demonstrations. Meanwhile, the continuing public confrontation spurred on Diodore's research. Doctrinal production could thus resonate with Flavian's and Diodore's relations.

Another affirmation concerned the collaboration with ascetics. According to Theodoret, Flavian and Diodore worked with Acacius's monastic friends, benefiting from their reputation for miracles. Again Diodore's teachings supported these cooperative ventures. Not only did he offer his own ascetic instruction in conjunction with scriptural training.95 He also provided Acacius a way to recruit monastic help. Miracles “attested even by the enemies of truth”96 had long been cited as evidence of God's favor. But Diodore and his students were able to explain the powers of ascetics by presenting them as types of the prophets or Christ. Thus Julian Saba could “strengthen the proclamation of truth,” directly through his deeds.97 The glory of Julian's following then reflected back on the asketerion. According to Chrysostom, it was the “simpler life” that attracted Libanius's pupils to Diodore's foundation in the first place.98 Doctrinal production could thus also resonate with relations between ascetics and doctrinal masters.

Theodoret's narrative offers a consistent perspective on the social dynamics of early Antiochene doctrine. By Theodoret's account, Antiochene exegesis and theology coalesced inside a clique of partisans: a group of ascetics, clerics, and laymen discovering its alliances and its enmities. Resonating with preaching and ascetic behavior, Antiochene doctrine affirmed these new relationships. Conversely, the relationships fostered the Antiochene doctrinal project. It is not clear how far Diodore's teachings were shared, even within Meletius's coalition. Most likely, his doctrinal tropes spread in a graduated fashion, more densely among star pupils than among nonlocal allies. Whether doctrine proceeded canvassing or vice versa, Theodoret does not say. He sheds little light on the doctrines' cultural roots. But before Meletius's partisans achieved episcopal rank, some were shaping Antiochene cues for their network, including dyophysite Christology, typological asceticism, monastic education, and anti-Arian (or anti-Apollinarian) taunting.

“CONFORMING TO HIS POLITEIA”:

MONASTIC RECRUITMENT

A striking feature of Theodoret's account is the extent to which he traced a continuous chain of episcopal recruitment. Theodoret relished naming bishops like Elpidius of Laodicea, who “conformed to [Meletius's] way of life (politeian) more fully than wax does to the type of a seal ring.” He noted their orderly successions: how Elpidius “succeeded the great Pelagius,” just as “the divine Marcellus was followed by the illustrious Agapetus,” a disciple of the ascetic Marcian.99 These were minor characters in his HE, but Theodoret included them, along with dozens of new prelates linked to Meletius's offspring. Such order in succession was rare in the fourth century. Any recruitment scheme signaled an innovation. But the most surprising part of this account was the supposed involvement of a (volatile) ascetic scene. Monks could make fine bishops. But for reliable recruitment, the monastic community had to be organized, instructed, and transformed. If Meletius's party staged coups, this would be a revolution.

The reshaping of Syrian asceticism has been recognized as a key shift in Christian culture. In the fourth century Aramaic-speaking Christians already had a full tradition of self-deprivation, self-transformation, and self-control. Some ascetics lived within the larger church community. “Single ones” (Syriac: ihidaye) and “covenanters” (Syriac: bnay/bnath qyama) reaped praise from the clergy for their celibacy, their poverty, and their liturgical roles. A few even became bishops. Other ascetics separated from the main community. Also called “single ones,” they wandered and preached in imitation of the apostles.100 Between 350 and 425, asceticism in Syria spread and diversified. Some “single ones” remained in towns. Others (like Julian Saba) took to remote wanderings or various forms of seclusion.101 Most famous was the new extreme, theatrical asceticism. Theodoret spoke of men donning iron underwear or sleeping in leaky wooden boxes.102 Then there were the confrontational ascetics, decamping to pagan shrines in search of martyrdom.103 Big numerical change came with communal asceticism. Ascetic masters collected disciples, while coenobitic monasteries formed in towns and villages.104 But categories of ascetic life remained fluid.105 By the 420s Syrian monasticism defied easy classification. It also defied cultural geography. It spread to Armenian and Arabic speakers. And it permeated the Greek-speaking world, such that “single ones” were equated to “monks” (Greek: monachoi).

Causes of this transformation are variously located, but one factor was the involvement of the clergy. While most innovations probably took place independently, Syrian bishops supported new forms of asceticism, with financing, public praise, advice, oversight, ordination, and coercion. Usually scholars have treated this involvement as part of a larger Mediterranean trend.106 In fact, each region fostered its own pattern of relations between monks and clerics—much depended on the people involved.

Early links between Syrian clerics and ascetics usually had to do with education. For generations virgins and covenanters had served as moral examples in preaching. By the 360s early hermits (such as Julian Saba) were cast in a similar role.107 Meanwhile, clerics began pushing ascetic practice as educationally useful. Diodore's asketerion was touted for its three-year curriculum of discipline and study (similar to a sophist's school). Soon hermits also attracted Christians seeking formal guidance. And by the 380s Chrysostom (a failed hermit) was advising congregants to take their children to the monks for moral instruction.108 Clerics may have been responding to the ascetics' (competing) popularity, but they also appreciated the monks' teaching capacity. Both hermits and archimandrites offered a model way of life (Greek: politeia) from which followers could build a sense of self within a community.109

Meletius and his allies, however, sought more from the monks than moral guidance. According to Theodoret, they wanted clerics imprinted with Meletius's politeia. Initially, they found new bishops through Diodore's asketerion, while most ascetic allies seem to have filled supporting roles. As the party grew, however, the bishops had to expand recruitment. They needed a permanent schooling apparatus, including curricula and reliable faculty. They also needed some way to sift pupils and place candidates in clerical vacancies. At the same time, the partisans had to extend the loyalties that had brought them success. This meant socializing clerical recruits. It also meant maintaining the cooperation of monastic leaders, in case they had to mobilize.

It was for these reasons that Syrian bishops got involved in monastic organizing, which according to Theodoret took off after 390. Part of this effort took the form of new individual contacts. Flavian and Acacius, we are told, visited with leading hermits. Some failed to meet their doctrinal standards—especially the “Messalians.”110 Others (such as Marcian and Macedonius) were certified as orthodox and ordained. Theodoret claimed that they expected no new labor from these monk-clerics, but his examples show how the mere title changed expectations.111 In any case, Theodoret traced each master's disciples, revealing multigenerational “monastic families”112 (again, see figure 10). Another part of the organizing effort involved encouraging coenobites. The HR pointed to seven new monasteries linked to ascetic allies (the HE added an eighth, in Edessa), listing their archimandrites up to the author's own day. But Theodoret was interested in more than new hermits and new houses. He named six bishops who emerged from this monastic following.113 Such bishops, we are told, continued ascetic lives, while other bishops praised ascetics and enriched the clerical-monastic alliance.

Theodoret's (filtered) picture of Syrian monasticism fits well with the regional trend of ascetic-clerical cooperation. It also makes sense of Antiochene doctrinal development, particularly the works of Theodore. Theodore's writings survive in fragments or later translations, which sometimes mutually disagree. What is clear is that he wrote on nearly every biblical and doctrinal topic, revising Diodore's teachings. His exegesis extended the “literal, historical” trope with new definitions and explanations. He developed a wider list of biblical types and clearer typological reasoning. He also refined Diodore's doctrinal conclusions, turning from “two sons” to dyophysitism. And he extended the doctrinal logic to Mary, suggesting the parallel appellations (theotokos and anthropotokos) that would bedevil Nestorius.114 These were not isolated speculations; they constituted a nearly comprehensive exegetical and anti-heretical corpus. Theodore was explicit about his aim to educate Christians in divine learning, stage by stage.115 His works may have been written for various immediate purposes, but they could all be used as teaching texts for new network members. Commentaries served as a basic public discourse, inculcating habits of Christian reading.116 The Catechetical Homilies then helped initiates to learn basic formulas. More detailed works like (the fragmentary) On the Incarnation probably served confidants, later in their curriculum. Such a corpus would work well with a graduated network of clerical recruitment.

Theodoret's account also helps to make sense of another development in the Syrian clergy, the new interest in translation. Meletius's original partisans were Greek-speakers.117 Neither Diodore nor Theodore wrote in any other language. But from the start they claimed Syriac-speaking ascetic allies. By the 410s these favorite ascetics had developed multilingual hermit circles and either mixed or parallel monasteries. Interestingly, it was around the same time that Antiochene clerics in Edessa (under Bishop Rabbula) started translating their doctrinal writings.118 Edessa also hosted Armenian translations. Armenian sources describe how Sahak, Katholikos of Persian Armenia, sent agents there, led by Mashdotz, to acquire important Christian writings.119 Theodore likely knew of these translation efforts. It was probably Mashdotz to whom he dedicated his Against the Magi.120 Theodoret's account ignores these efforts. But multilingual monasteries provide a probable context for early translations. These groups would need not only rules and prayers, but also teaching texts, in multiple languages.

Perhaps most significantly, Theodoret's account helps to explain why the early Antiochenes may have taken such interest in monasteries. Recruitment, after all, is only one part of network building; members must create a sense of solidarity. This was hard enough in a local partisan following, let alone across a large region. Signals of shared orthodoxy must have helped. Everyone could join in the hostility to Arians and Apollinarians, while the inner circle of experts worked with more detailed formulas. Theodoret, however, returned repeatedly to the sharing of a politeia, a way of living. Monasticism was celebrated in the late fourth century for its “brotherhood” of shared habits and values.121 It is understandable how clerics wanted to apply the same brotherhood to the clergy. Monastic origins would provide a common bond among Antiochene recruits. Praise of asceticism could enrich the exchange of cues among bishops, priests, hermits, and archimandrites, as well as their followers.

Theodoret's account thus helps to explain Antiochene involvement in the monastic community. Moreover, it makes sense of the continuity of the network. By the early fifth century, Meletius's partisans were linking up with hermits and archimandrites across the region. No doubt they hoped to gain from ascetics' holy reputations. But Theodoret suggests more practical purposes: to organize new partisans, to train new clerics, and to consecrate loyal bishops. Clerics did not control the monastic community; Theodoret may overstate their role. But certain developments, he suggests, were due to specific Syrian bishops, working to perpetuate the Antiochene network.

“DOCTOR OF THE WHOLE CHURCH”:

INFORMAL CLERICAL LEADERSHIP

Few concerns pervade Theodoret's HE as much as proper church leadership. Since the early fourth century, church historians had sought to highlight the virtues of their favorite leading bishops. Socrates celebrated Proclus of Constantinople, a genteel peacemaker. Sozomen took to Chrysostom, a rigorous reformer. Theodoret touted several, mostly Syrian figures: Eusebius the calm confessor, Meletius the patient party-builder, Flavian the courageous communicator, and Acacius the active ambassador, as well as Diodore the resourceful researcher and Theodore the doctor of orthodoxy.122 The purpose of his portraits was more than hero veneration. Collectively they outlined a model for episcopal authority. The model contained standard elements: personal piety, good oratory, interpretive skill, ascetic discipline, generosity, and precise orthodoxy. But there were unusual features. Theodoret's favorites received mixed treatment from other historians. Half of his heroes held minor sees. Nearly all made a mark before taking episcopal office, some before becoming clerics. Most important, Theodoret's favorites showed a cooperative sensibility. His ideal was not one leading bishop, but an informal leading group. This perspective is surprising because it runs counter to trends in church governance. If Theodoret was correct, the Antiochenes maintained a distributed sort of authority from Meletius's day to his own.

One of scholars' favorite topics has been the development of episcopal hierarchy. Since at least the second century, each bishop had asserted control over his own see.123 While bishops established a loose mutual oversight, autonomous prelates remained the norm. The fourth century, however, began a deepening of church hierarchy. The Council of Nicaea gave special status to the metropolitan of every province (except in Egypt and parts of North Africa). It assigned higher honors to three primates (Rome, Alexandria and Antioch), to which a later council (in 381) added a fourth (Constantinople).124 Often scholars have treated the canons as grants of legal power. These statements, however, were deliberately vague. Councils claimed to be reaffirming traditional privileges, which varied between regions.125 Fifth-century Christians still had to define what metropolitan status meant in practice. For primates even more was left to local tradition, or to the church leaders themselves.

In fourth-century Syria, most observers have found a broad distribution of clerical authority. Scholars have noted the rise of the bishop of Alexandria to directorship in Egypt.126 The bishop of Antioch, by contrast, has seemed like a “first among equals.”127 Syrian metropolitans presided at provincial councils and consecrated new suffragans, but “irregular” ordinations were common. This looser hierarchy was recognized by the broader church. According to Socrates, the Council of Constantinople in 381 named two bishops (metropolitan Diodore of Tarsus and suffragan Pelagius of Laodicea) as superintendents of the East, all without “violating the rights of the see of Antioch.”128

Theodoret's account suggests another factor in Syrian exceptionalism: the troubles of the original Antiochenes. The HE described multiple figures in roles of partisan leadership. Meletius claimed the highest office, but because of his exile he relied on agents and proxies. The three lieutenants then appear in complementary roles: Diodore as brain trust, Flavian as public agitant, and Acacius as universal liaison. Talent, devotion, and learning gave these partisans as much influence as any office did. And all of them needed the help of ascetics and other bishops (e.g., Eusebius of Samosata and Basil of Caesarea), not to mention the emperor, to take over the region's key sees. After Meletius's death, problems continued, as did cooperation. Flavian relied on Diodore and Acacius (his consecrators), as well as Nectarius of Constantinople. Again, it took the skills of multiple figures to maintain the network's influence. Theodoret paid honor to the bishop of Antioch and to metropolitans. But his narrative showed no Syrian bishop exerting coercive authority. What most of his leading figures claimed was centrality: connections to those inside and outside their network.

By the 410s and 420s, Antiochene bishops were more secure in their influence, but according to Theodoret, they remained interdependent. Bishops of Antioch were presented as solid (if imperfect) leaders. Neither Porphyrius, nor Alexander, nor Theodotus, however, ran the see for more than eight years. Acacius of Beroea lived on as the last original partisan, without a monopoly on authority. If Theodoret assigned anyone higher leadership it was Theodore. His writings won him the author's moniker “doctor of the whole church.”129 Still, the HE hints at (suffragan) Theodore's dependence on others. His commemoration, after all, appeared alongside that of Theodotus and Polychronius.

Thus Theodoret helps to explain the limited authority of Syrian metropolitans and primates. According to the HE, looser leadership was required for Meletius and his partisans, and remained essential for his successors. After two generations it could easily have become entrenched. Informal leadership may have older roots than Theodoret suggests. And it may not have been accepted by every Syrian bishop—his presentation omits some troubling episodes, as we shall see. Nevertheless, Theodoret suggests that the broader distribution of authority among Syrian bishops be seen as an Antiochene legacy.

“HIDEOUS DETAILS”: EVALUATING

THEODORET'S ACCOUNT

Theodoret's HE provides social context for the production of Antiochene doctrine, the reorganization of Syrian monks, and the distribution of episcopal authority. Like any narrative source, however, his account must be interpreted carefully, with an eye toward the author's situation. On the one hand, Theodoret was well-informed. He had contact with key figures and access to church archives, as well as personal experience. On the other hand, Theodoret wrote within a matrix of rhetorical aims. He wrote to encourage defenders of an embattled orthodoxy. It was sensible for him to celebrate Meletius's partisans, to recall their endurance of hardship, and to tout their solidarity. Theodoret and his friends had good reason to seek a supportive sense of heritage, or even to construct one. Thus before accepting Theodoret's representations, we must check them against other clerical sources for the late fourth and early fifth centuries.

The most obvious outside sources to check are the Church Histories of Socrates and Sozomen, who wrote about Syrian clerics with less investment than Theodoret. We have already noted Socrates' and Sozomen's unflattering treatment of the machinations of Meletius's party. In their view, his partisans conspired to set Paulinus aside.130 Acacius, in particular, was presented as ruthless and vindictive. To Socrates and especially Sozomen, Acacius was one of the main persecutors of John Chrysostom (more on this below).131 Unlike Theodoret, Socrates and Sozomen were willing to find fault with these Syrian clerics. And they did not see Diodore and Theodore as lynchpins of Nicene triumph.

When it comes to social connections, however, Socrates and Sozomen generally confirm Theodoret. Socrates noted Diodore's ascetic and educational endeavors, and his recruitment of Theodore and Chrysostom.132 Sozomen verified links between the main partisans, recalling how Diodore and Acacius worked on Flavian's behalf.133 Neither Socrates nor Sozomen dealt continuously with Syrian clerics; Theodoret may have read their unflattering statements and wished to respond. Nonetheless, both church historians offer details that support Theodoret's depiction of a tight Antiochene partisan following.

Greater troubles for Theodoret's account come from direct clerical observers, and from one episode in particular: the controversy over John Chrysostom. Scholars have debated whether Chrysostom was “Antiochene” in his doctrinal thinking. Socially, however, he was clearly linked to the early partisans.134 Theodoret recognized Chrysostom as a member of Meletius's following, a student of Diodore, and a friend to Theodore. He defended Chrysostom's actions as bishop of Constantinople, but he chose to omit the “hideous details.”135 Socrates and Sozomen had no such qualms, but they focused on Chrysostom's foes in Alexandria and Constantinople. It is mainly Palladius of Helenopolis, and Chrysostom himself, who reveal Syrian dimensions of the conflict that surrounded John's fall. Among the foes of Chrysostom Palladius included more Syrian bishops than Anatolians or Egyptians.136 Other sources mention Acacius as Chrysostom's opponent, but Palladius made him an instigator of the controversy. Not only did he place Acacius and other Syrians at the Synod of the Oak in 403, which first deposed Chrysostom; he claimed that Acacius coordinated the colloquies of Easter 404, where John was finally exiled.137 Palladius then noted the schism this inspired in Syria between Acacius's party and a “Johannite” faction. And he explained how Acacius and his allies rigged elections in Antioch to appoint their candidate, Porphyrius.138 Palladius thus presents a Syrian clergy filled not with harmony but with factionalism. He even lists supporters of John who suffered for favoring the restoration of the exiled bishop.139 Palladius's picture is partly affirmed by Chrysostom's letters written from exile. Here Chrysostom appealed to many bishops whom he counted as supporters, including Theodore.140 We can see why Theodoret wanted to “throw a veil over the ill-deeds of men who share our faith.”141 Over an issue unrelated to doctrine, the followers of Meletius had torn their camaraderie apart.

Yet even this dark episode does not contradict Theodoret's basic representations of an Antiochene network; it merely complicates the picture. For the Syrian dimension of the Chrysostom affair looks like a contest for influence gone awry. As Flavian of Antioch grew frail, John Chrysostom and Acacius were two of several clerical figures with claims to his position of influence. If Palladius is accurate, Acacius used the controversy over John to build a following, which he employed to name his own candidates to open sees. Meanwhile, Theodore and the “Johannites” attempted to build their own faction. In chapter 2, we drew a network map with multiple figures of influence. Any such network might face divisive rivalries. In any case, the Syrian split over Chrysostom was eventually resolved. Bishops of Antioch restored John's name to the diptychs, and even Acacius assented.142 Palladius saw Acacius's actions as a betrayal. But betrayal certainly plays a role in close-knit communities (see next chapter).

What most complicates Theodoret's story are stray notes about the loyalties of Syrian bishops. Theodoret's HE mentioned no opponents of his network in the Syrian clergy, apart from suspected Apollinarians. Yet his list of allies covers scarcely a sixth of the region's sees. Clearly the followers of Meletius did not completely take over the region. Some monastic groups (such as that of Alexander the Sleepless) resisted the bishops' oversight.143 Theodoret acknowledged recruitment in monasteries or through ascetic relationships, but he said nothing about other modes of picking new clergymen. Yet his letters mention married bishops—even a twice-married bishop recruited by Acacius.144 Almost all of Theodoret's examples of Syrian monk-bishops date to the 410s and 420s. Perhaps monastic recruitment was a more minor, later development than he suggested. Theodore's doctrinal influence beyond his inner circle may have been limited. His supporter-turned-critic, Rabbula of Edessa, complained that Theodore had doctrines he would only share with close confidants.145 Even Theodore's admirers acknowledged that he sometimes had to retract controversial tropes when outsiders got wind of them.146 Several letters recount contentions among the Antiochene leaders. The loose distribution of authority may have been an accident of competing claims rather than a shared tradition. Theodoret imagined a harmonious Nicene clergy from the 380s to the 420s. His actual predecessors must have seen things differently.

And yet, Theodoret's general picture cannot be dismissed. His narrative shows us glimpses of the early Antiochene network. Theodoret's prosopographic testimony remains largely uncontested. And the thicket of personal alliances that it presents finds confirmation across a spectrum of sources. The members of this network did not all share a single line of doctrinal thinking. But Theodoret suggests that they traded signals of friendship and shared orthodoxy, densely in a core group and more sparsely further afield. The late 420s furnish our earliest documents from the conciliar collections and a few personal letters. At this point we find the sort of Antiochene cues and connections discussed in chapters 1 and 2. At the start of the First Council of Ephesus (431), Antiochene clerical links stretched across Syria (see figure 11, in the next chapter). To build such an alliance need not require fifty years, but it would take some time. Theodoret's Church History offers one representation of the Antiochene heritage. His narrations were geared to inspire his contemporary allies. But they had to be plausible, to make sense of existing records. Theodoret's idealized picture of a clerical party was based, in all likelihood, on a real (i.e., intersubjective) cue-trading network. In any case, it was an Antiochene sense of heritage that grounded Theodoret and his associates during two decades of controversy. The contrast between the present (in the 430s and 440s) and the (partly constructed) past was all too obvious. The next chapter will turn from narrative analysis to documented micro-history, to follow the network through its “Nestorian” crisis and resulting transformation.