2

Shape of a Network

Antiochene Relational Patterns

It was probably in 433 that Andreas of Samosata realized the full social cost of participating in doctrinal conflict. For three years this bishop had contributed to the debates. He wrote insistently against Cyril's Twelve Anathemas against Nestorius. Despite missing the council of Ephesus, he joined his colleagues' excommunication of the Egyptians. Meanwhile, he maintained key Syrian alliances, especially with Alexander of Hierapolis, John of Antioch, and Theodoret.1 By late 432, it was clear that this trio was going to split. Alexander, John, and Theodoret argued over negotiating positions, while Andreas did shuttle diplomacy. He meddled enough to offend all three allies, and a neighbor who tried to oust him.2 Still, Andreas pressed for reconciliations, with John and then Theodoret. Through them he won support from certain imperial officials, and he rebuilt links to bishops, lower clerics, and lay notables.3 But Alexander refused to restore relations. “Consider the power of God,” Andreas begged, “who reconciled…the heavens and the earth, who may join the divided limbs of the church, and who will give satisfaction to Your Holiness.” It was to no avail. By 436, Andreas had settled into the core of his doctrinal network, but Alexander had been sent to the mines.4

The efforts of Andreas showcase the specific social context in which Syrian bishops worked and communicated. Andreas, like his colleagues, was enveloped by relationships. Belief and behavior depended on ephemeral arrangements of bonds. The pursuit of orthodox doctrine mattered to Antiochene bishops. But it was not abstractions that motivated Andreas to mediate; it was the pull of personal affections.

This second chapter is devoted to tracing out the Antiochene coalition in which Andreas and Theodoret were embedded. The exchange of social cues, noted in the first chapter, can be mapped, synchronically, to approximate an Antiochene network, as it was circa 436. This network map can then be analyzed and compared to scholarly models. The analysis offered here has limitations. It is constrained by the evidence, which is, at best, valid for a brief period of time. Network analysis, however, can help us to make sense of the social data, to contextualize individuals' actions (explored in subsequent chapters).

In fact, mapping the Antiochene coalition reveals some recognizable patterns. The mostly clerical network featured central hubs surrounded by a loose periphery, in a shape known to network analysts as the modular scale-free topology. This shape is hardly unusual; any group that recruits freely tends toward the same basic template. More noteworthy is the specific arrangement of Antiochene social links. At the center we find a tight clique of four bishops and one lay notable. On the periphery we find members stretched unevenly across Syria. These features prove little on their own, but they do furnish hypotheses, which can be tested against other evidence. The core structure suggests an informal but palpable order of leadership. The periphery suggests a group that, while claiming to represent the East, left room for opponents to arise.

METHODS FOR MAPPING ANTIOCHENE RELATIONS

We begin the mapping process with some methodology. Letters and conciliar transcripts record thousands of social interactions, interpersonal and collective. Mapping a network requires us to figure out which interactions signal meaningful relationships, and to decide which relationshps were “Antiochene.” Any system of classification imposes on the evidence. Still, we must choose how to arrange the data and how to set thresholds for identifying a bond.

The first step to prepare for network analysis is to organize the social information. The simplest method would be to classify subjects by ecclesiastical rank: bishops, lower clerics, monks, and laypeople. This taxonomy fits with surviving church records, which understandably focus on bishops. It also fits with the institutional structure of the late Roman church. Lower clerics, monastic leaders, and lay figures all played roles in these disputes (as did the emperor). But it was bishops who laid claim to ritual and doctrinal authority—at least in sources that they controlled. Thus, this chapter will work in layers, expanding from purely episcopal interactions to bishops' dealings with lower clerics and monks, then to their contacts with laypeople.

Next, mapping social relations requires criteria for identifying personal bonds. Here we turn to the sorts of cues outlined in the first chapter. Nearly every extant letter features some nod to emotional attachment. Most include signals of shared orthodoxy. Individual instances of cue-giving tell us little about relationships. But the exchange of multiple cues and the recalling of past interactions do suggest an intersubjective bond. Throughout this process, we must remember the incompleteness of our evidence. A lack of cue-giving between people does not prove that a link did not exist. Nevertheless, by combining all the signals sent within six years of 436, we can get an approximation of this one portion of the late Roman social fabric.

Finally, mapping the Antiochene network demands a test for distinguishing internal from external bonds. Here we must make a stronger interpretive intervention. The previous chapter noted an “Antiochene” set of cues, including terms of emotional attachment (such as philia and agape), doctrinal watchwords (such as “exactness,” “Apollinarian” and “two natures”), oblique signals of intimacy, and modes of translation. Chapter 1 also noted an “Antiochene” set of practices, including communal rituals (during visits and councils), epistolary habits (during composition and collection), mutual recommendation, and even surveillance. (Please note, it is the set, not the individual cues, which are labeled as Antiochene). So, for purposes of drawing a map, let us set a reasonable threshold for inclusion. For a relationship to be considered Antiochene, a sender and recipient must share (that is, either personally exchange, collaboratively produce, or recall past instances when they exchanged or co-produced) at least three different cues or habits out of those listed in the first chapter, on more than one occasion, including at least one specifically doctrinal cue.

We could go further with this approach. We could grade bonds on the basis of numbers of attested interactions. We could also mark links that show special “intimacy” or distinguish personal contacts from communal ones. Occasionally this study will refer to such distinctions. For the sake of simplicity, they will not be visually represented.

A NETWORK OF BISHOPS

With interpretive methods set, we may now map and analyze the first layer of our network, relations among bishops. From the perspective of our sources, at least, bishops formed the backbone of the Antiochene network. Nearly all Nicene bishops could claim some official friendship and shared orthodoxy. Of the approximately six hundred letters in our archives, just over half were sent by bishops to other bishops. The communications, however, tend to involve a few repeated names. When sifted via the methods just mentioned, these records showcase a small core of noted Antiochenes reaching out to a regionally limited network.

Studying episcopal contacts involves the largest set of social data, and thus the fullest analytical process. We start with some prosopography, which comes mostly from conciliar acta. Records of the First Council of Ephesus in 431 list about 250 prelates, about 30 from between the Taurus mountains and the Sea of Galilee.5 Regional and provincial councils in Syria add 24 more. The Acts of the Second Council of Ephesus in 449 name at least 135 bishops, with just 22 from Syria.6 But the list from Chalcedon (in 451) of more than 500 bishops includes about 128 Syrians.7 Together, these acta trace the succession of bishops for hundreds of towns in the 430s and 440s, including about 50 Syrian sees.8 Next we must identify the social links recorded in our archives. Here the conciliar documents and the personal letters each provide a set of data, which can be explored separately before the full pool is assembled. We start with the simpler of the two data sets, from Theodoret's collected correspondence.9

Theodoret's personal letter collection showcases two key features of Antiochene relations. On the one hand, it traces network links with a regional focus. Theodoret's friendly letters went to bishops in Anatolia, the Balkans, Constantinople, and Egypt. A few went to Persia and the city of Rome.10 Relations that meet “Antiochene” criteria, however, fall almost entirely within the region of Syria. It was only with Syrians that Theodoret both acknowledged past exchanges of key signals and offered new cues. On the other hand, Theodoret's collection locates “intimate” bonds within a tighter area. The fullest sets of Antiochene social signals connect Theodoret with a handful of his neighboring peers. This collection is, of course, centered on one correspondent. It tells us little about the links among Theodoret's contacts. But we can compare its basic features to the larger data set from conciliar records (especially from Ireneaus's Tragedy).

In fact, conciliar letters and transcripts reinforce the impressions of Theodoret's correspondence. A few bishops (including Theodoret) are shown to have connections across the Mediterranean.11 But for “Antiochene” bonds, the picture again centers on one region. Just six non-Syrian bishops gave or received Antiochene cues—and by 436 none of them still held a see. Meanwhile, the richest exchanges involve a small group of bishops. Theodoret's list of “intimate” contacts is slightly augmented by the conciliar documents. More importantly, these contacts are shown to form interlocking clusters. Conciliar records focus on several individuals. Still, they echo the basic pattern of Theodoret's collection: a network focused on Syria, with a smaller, densely woven core.

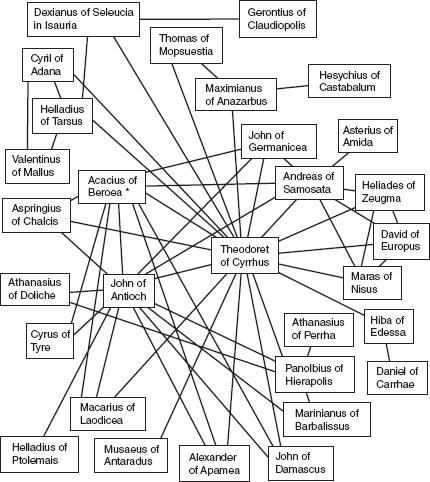

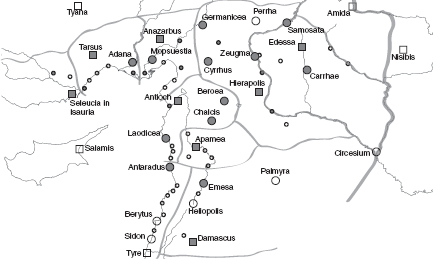

These two archives combine with other sources12 to approximate an Antiochene episcopal network. Forty bishops meet our standards for attachment to this network; 34 of them had sees in Syria, and 30 (all Syrians) were running bishoprics in 436 (see figure 2). The network is dense (boasting 57 links and an overall density of 0.131). It is also tight (with an average path distance, or degree, of about three links). Areas of higher density alternate with “holes,” which create a number of cliques and clusters. Individual members cut a range in terms of their connectivity. The majority had 1–3 links; several bishops had 4–5 links, with higher numbers of bonds reached by four prelates. These men (Acacius of Beroea, John of Antioch, Andreas, and Theodoret) are not only the most well connected members, but also the most central, with quickest access to the rest. Thus we can discern a shape to the core members of this network, with an unambiguous center and a set of clusters leading outward to the periphery.

FIGURE 2. The Antiochene episcopal network, circa 436, according to letters and conciliar documents. Links approximate evident or implied exchange of 3 or more Antiochene social cues (including at least one doctrinal cue) within 7 years of 436 (more links may have existed).

Network statistics: nodes = 30, links = 58, density = 0.133, diameter = 4. Connectivity: Theodoret = 19, John of Antioch = 13, Acacius = 9, Andreas = 8, all others = 5 or fewer. Centrality: Theodoret = 39, John of Antioch = 43, Acacius = 50, Andreas = 55, all others = 60 or higher.

* Acacius of Beroea's death is here assumed to date to 437. See start of Chapter 1.

The basic shape of this network holds even if we speculate about links that the evidence may leave out. Records and methods are focused on the core membership. They have assuredly missed relationships and people, especially on the periphery. It is likely, for instance, that metropolitans (such as Helladius of Tarsus and Maximianus of Anazarbus) had links to additional bishops in their provinces. It is probable that central figures had further connections. Missing links might actually bridge some of the gaps that appear between cliques, or they might reveal whole new clusters that are barely attatched. But our map does make for a valid approximation, so long as our focus is the core itself. The smattering of missing figures is not likely to perturb the main pattern of relations surrounding the hubs.

The shape of this network matters because it conforms to a known relational architecture: the modular scale-free topology13 “Modular” refers to the clustering of members. “Scale-free” refers to the distribution of connectivity, with many ill-connected members and a few “hubs.” Modular scale-free networks have certain properties. The structure allows for rapid communication, growth without central direction, and persistence despite localized losses. As we shall see, the modular scale-free pattern makes suggestions about the dynamics of network leadership and membership. Before we analyze further, however, we need to include other figures who joined in the network.

PARTICIPATION OF OTHER CLERICS AND ASCETICS

Surviving sources trace an Antiochene network centered on bishops, but these bishops were never alone. Their social position was defined, in part, by their relations with lower clerics (especially priests, deacons, deaconesses, country bishops, and oikonomoi) and monastic leaders (many of whom were also ordained). Just over one-eighth of the extant letters were addressed to lower clerics or ascetics. This count does not include clerics who served as envoys. Nor does it capture the constant interactions of bishops with their subordinates in liturgical, charitable, and personal settings. Our records cannot support a full network analysis of the Syrian clergy. But they do spotlight some additions to the Antiochene party. On the periphery they reveal a large pool of clergymen and monks; at the core they illuminate a few of the bishops' favorites.

Our treatment of broader clerical links must proceed differently from coverage of bishops because it starts from thinner prosopography. Syria's clergy included thousands of people—a hundred or more in each major city.14 Quasi-normative sources list duties for each rank of the clergy, as well as for archimandrites, monks, and semi-ascetics (e.g., “covenanters”).15 Surviving documents, however, name just a few clerics and leading ascetics, not even one-hundredth of the likely total. What data do exist mostly come from Theodoret's collection. They cannot support conclusions about the region's clergy. But they do showcase where some priests and monks fit in the network.

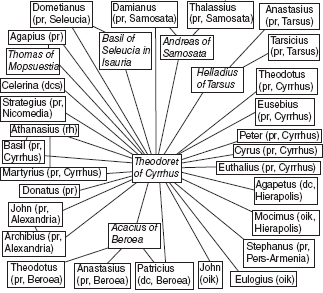

FIGURE 3. Subordinate clerics in the Antiochene network, circa 436, according to letters and conciliar documents. Links approximate evident or implied exchange of at least 1 Antiochene social cue within 7 years of 436 (more links may have existed). dc = deacon, dcs = deaconess, exm = exarch of the monasteries, oik = oikonomos, pr = priest, rh = orator.

Letters and acta reveal select clerics in significant Antiochene roles. Some of Theodoret's letters addressed priests like Agapius, engaged in tasks of recruitment.16 Other letters gave clerics special missions; the oikonomos Mocimus, for instance, was asked to persuade his bishop (Alexander) to change positions in a dispute.17 Many clerics only appear as couriers, but these envoys receive more signals of intimate friendship than almost anyone else.18 Records place at least 23 clerics in an Antiochene relationship with Theodoret circa 436, (2 deacons, 1 deaconess, 3 oikonomoi, 15 priests, and a church orator). A few others are linked in similar fashion to other bishops (see figure 3). These clerics never rivaled bishops in numbers of links, but often they linked key members to one another, giving them some centrality.

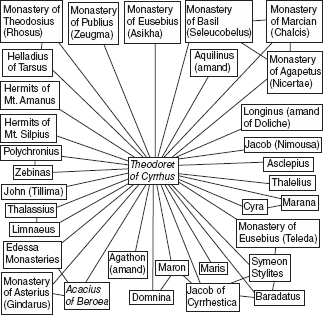

The records offer a slightly different picture for inclusion of ascetics. Several archimandrites received attention from Theodoret, most in Syrian communities. Generally the letters signaled support; a few asked for specific cooperation.19 Conciliar documents augment the picture: three famous ascetics, Baradatus, Jacob of Cyrrhestica, and Symeon Stylites, were asked to mediate in multiple episodes of church conflict.20 Hagiography also adds information. Theodoret's History of the Friends of God records 7 monasteries and 14 clusters of hermits with whom he had a relationship (see figure 4). The purpose of these connections is not instantly clear, but two quick possibilities arise: mobilization for charity or public protest, and recruitment to the priesthood and episcopate. Both possibilities find indirect support (see below, Chapter 3 and 4). In any case, select monastic leaders won inclusion as mediating agents in the bishops' network.

FIGURE 4. Ascetics and monasteries in the Antiochene network, circa 436, according to letters, the HR, and conciliar documents. Links approximate evident or implied exchange of at least 1 Antiochene social cue within 7 years of 436 (more links may have existed). amand = archimandrite.

Clerics and ascetics thus fill out the Antiochene social map, without altering its basic shape. Yet we must realize that the clerics and monks named in our records are not the rank and file on regular duty. Theodoret and his peers sometimes addressed groups of clerics and monks. They sent guidelines for doctrinal instruction and exhortations to “take greater care” of the flock.21 But just one cleric is noted for service in the liturgy.22 Just one monk is recorded as aiding in pastoral care.23 No clerics are singled out for their management of finances or charity. The prayers of clerics and monks were treasured, but their labor may have been taken for granted.

Clerical and monastic records are too thin for broad conclusions, but they offer some suggestions. They posit at least two tiers of network participation. On the periphery stood ordinary clerics and monks. Performing basic duties, they leave little trace in the records. Closer to the core stood the bishops' favorites. They appear regularly as social mediators. It is not clear what portion of the clergy or leading monks found such favor. But from our (admittedly bishop-centric) sources, no clerics or monks seem to have rivaled the bishops as hubs.

PARTICIPATION OF THE LAITY

Theodoret and his associates constituted a clerical network, but not exclusively so. As church leaders they had to deal with sizable lay congregations. And they relied on specific lay notables, for loyalty, donations, and physical protection. About one-third of the extant letters in our archives were sent by or to non-clerics. Most of these involve imperial and local elites, not average members of lay congregations. Nevertheless, even these sparse records show certain patterns. Congregations clearly received cordial statements from bishops and reports on the conflict. Local notables were often called friends. Just a few laypeople appear involved in core Antiochene business. But one layman seems so involved that he represents a fifth hub of the network.

Relations between clerics and the laity require yet another study method because the prosopographical evidence varies. The majority of Syrian laypeople are personally hidden. A typical diocese hosted tens of thousands of ordinary congregants, some highly involved, some barely connected. The local notable class is less obscure. Decurions, professionals, and bureaucrats inevitably had dealings with bishops. Our sources, however, are constrained. In Syria, they name only a few notables from Cyrrhus, Edessa, and Antioch, and none from other towns. It is only at the level of senators and officials that we find detailed information to match the coverage of bishops.

Evidence for bishops' lay connections conforms to these gradations of social rank. For the majority of congregants we have only a general picture. Theodoret wrote (a few preserved) sermons. So did colleagues (notably Basil of Seleucia). The bishops also wrote letters to the people (laoi or populus) of various towns. Such collective communication was important. It allowed bishops to build community through shared reactions.24 Collective address, however, had its limits. Preaching and liturgy were unlikely to bring whole congregations beyond the outer periphery of a doctrinal network.

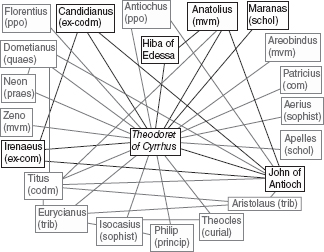

Theodoret dealt more personally with notables, by offering pastoral care. He issued moral rebukes and wrote notes of consolation, locally and to other dioceses.25 For most laypeople, Theodoret did his ministry orally. But letters brought the notable laity a sense of attachment. And pastoral care often led to greater cooperation.26 Still, even prominent laypeople were kept at a distance. Only a few received multiple cues, and none the main signals of doctrinal affinity (see figure 5).27 Many notables had personal ties to the bishops, but most were marginal to the doctrinal network.

FIGURE 5. Lay notables in the Antiochene network, circa 436, according to letters and conciliar documents. Black links approximate evident or implied exchange of 3 or more Antiochene social cues within 7 years of 436 (more links may have existed). Grey links approximate evident or implied exchange of 2, or of non-Antiochene, cues (only those linked to multiple Antiochene associates are included). codm = count of the Domestici, com = count, curial = curialis, mvm = master of soldiers, ppo = praetorian prefect of the East, praes = provincial governor, princip = principalis, quaes = quaestor, schol = scholasticus, trib = imperial tribune.

The situation changes with regard to imperial officials and senators, a few of whom counted as Antiochene allies. Some contact with the political elite was required. Provincial governors had to be invited to festivals.28 Grieving officials had to be comforted.29 Prefects received updates on church business, personally and for the court. During doctrinal disputes some envoys were forced upon the bishops.30 Still, a few connections went beyond obvious formalities. At least four high officials show signs of Antiochene affinity: Candidianus the count of the Domestici, Titus the count of the Domestici, Irenaeus the count (and future bishop), and Anatolius the master of soldiers. In fact, Anatolius won special inclusion. By 436 he had defended Theodoret's allies for six years. With his clerical contacts, and his brokering of further court contacts, he could be considered the fifth hub.

Laypeople clearly augmented the Antiochene network. Letters and council documents reveal a peripheral role for most congregants, whose precise involvement lies beyond view. But they establish personal links between bishops and many local notables. And they place a handful of powerful laymen within the core network. Lay participation does affect the shape of the network. It adds new mediating figures and another hub. As with clerics, the records have no doubt left out important lay participants, particularly notables from towns besides Cyrrhus. The overall network, however, retains a similar tightness and density and a modular scale-free form.

CENTRALITY AND INFLUENCE: THEODORET

AND HIS INNER CIRCLE

So far, this chapter has traced basic membership patterns within the Antiochene network. Now we can go further, to analyze internal dynamics, starting with the distribution of influence. Influence was of serious concern to the bishops. Theodoret once worried to a colleague (sarcastically) that he was “looked down on rather than looking down on [others]” and “guided rather than guiding.”31 As we have noted, the network included five hubs. Network theorists stress the influence of these central figures, even if they lack institutional power. Late Roman Christian culture provided several models for assertion of authority. Theodoret's network followed none of them exclusively. Records reveal many figures acting as leaders—primates and metropolitans but also elders, ascetics, authors, and proteges. Even as these figures competed for influence, the relational pattern pushed them to cooperate.

Before examining social patterns, let us consider a more common way to explore the distribution of authority: rhetorical models. By models, I mean both the hierarchies of rank outlined in canons, and the rationales that bishops employed to get others to pay heed. The most obvious model of Christian authority was clerical rank. The Apostolic Constitutions repeatedly instructed laypeople and monks to join the clergy in obeying bishops.32 Fifth-century bishops used this model whenever they commanded a priest or congregant, or patronizingly called one a friend.33 Our network map clearly reflects the clerical hierarchy; the sources allow for nothing else. But clerical ranks could not help when it came to relations among bishops, or with powerful lay officials.

Regarding bishops, the late Roman church offered several models for deciding which should lead. One familiar model is primacy, the “customary privileges” accorded to “apostolic foundations” and other important cities.34 In Egypt and Southern Italy, bishops accepted one form of primacy: regional directorship. Alexandria and Rome made appointments and dogmatic statements with little room for dissent. In other places, see-based rankings took a less decisive form.35 Syrian bishops accepted the primacy of Antioch: the right to preside at regional meetings and to consecrate bishops of important sees.36 But when John of Antioch tried to assert supreme doctrinal authority, his efforts were rebuffed.37 His successor Domnus accepted a more limited claim; though he spoke proudly of his “throne of Saint Peter,” he also advocated “apostolic humility.”38

More universal than regional primacy were the privileges tied to metropolitan sees (Seleucia in Isauria, Tarsus, Anazarbus, Hierapolis, Edessa, Amida, Apamea, Damascus, Bostra, and Tyre, as well as Antioch). The Council of Nicaea held that metropolitans were to call provincial synods and either to consecrate new bishops or to give written consent.39 Theodoret reaffirmed this principle; he spoke of some actions as “ordered” by his metropolitan.40 Yet Syrian metropolitan authority also had limits. The Apostolic Constitutions told metropolitans to “do nothing without the consent of all.”41 And Theodoret's discussion of orders was ironic, for he was talking about a meeting where suffragans had defied their superior. Like primacy, metropolitan privileges represented just one component of claims to authority.

Other rationales for leadership were connected with the person rather than the see. One was seniority. Throughout the Christian community, elderly bishops were treated with honor. Syria hosted an extreme example in the 430s, the centenarian Acacius of Beroea, who received deference from fellow bishops and even solicitation from the emperor.42 Yet others also claimed years of experience and longer prospects. Another rationale was asceticism and monastic leadership. Here, too, Acacius had an advantage. But by the 430s his colleagues included several former monks and archimandrites.43 A third rationale was evident doctrinal expertise.44 In the 420s, Theodore of Mopsuestia had the longest list of treatises. By the late 430s, this honor went to Theodoret and Andreas in Greek, and possibly Hiba of Edessa in Syriac. A fourth rationale was connection to past heroes. Thus relative novices could claim the mantle of their mentors. And finally there was patronage. A number of bishops owed their positions to the hope that they would benefit those in their charge.45 Many people could use at least one of these rationales to claim leadership. But mere claims cannot tell us who actually exercised authority.

It is here that our network map helps by charting the centrality of would-be leaders. Our Antiochene map presents multiple figures in positions of local centrality. With links to all the members of a cluster, they were placed well to manage communication. Four bishops (Theodoret, John of Antioch, Acacius of Beroea, and Andreas) are presented in positions of highest centrality, along with one layman (Anatolius). They had the greatest capacity to reshape social connections by adding or altering social cues. All scale-free networks have a few high-centrality hubs. The number and identity of the hubs, however, are matters of historical contingency. In this case, processes of growth and development put several people in favorable positions.

Our network map also helps to probe the distribution of influence by charting irreplaceability—the extent to which network relations rely on particular members. For this task we observe the hypothetical impact of selectively removing members. In our social map irreplaceability is fairly low. Single members or hubs could disappear without disrupting the network. Nonetheless certain losses would affect group tightness. Without John of Antioch, some members would grow distant. Without Theodoret nearly everyone would have a harder time communicating. Combination losses would mean greater changes. Without Andreas and Theodoret two clusters would be left hanging by a thread. Still, it would take the loss of four of the five hubs to collapse the network entirely. None of the members is thus truly irreplaceable; all of them faced limits in the quest for influence.

By combining network maps with rhetorical models we get a richer picture of clerical authority. Many Antiochenes had at least one viable rationale for claiming leadership. The central five had multiple rationales and various advantages. John of Antioch held the highest hierarchical title. Theodoret appears the most central (even if we ignore his personal letter collection). Anatolius had the most coercive power. But none of these men was positioned to hold ecclesiastical dominance. With so many claims to authority, we might expect conflict. Indeed, the Syrian bishops did contend for influence (see Chapter 4). But multiple would-be leaders need not bring hostility. Communications reveal that the five central hubs worked to preserve cordial relations. They formed a high-density inner circle where notes of intimacy were common. Members of the inner circle publicly praised one another (hence Theodoret's eulogy for Acacius, noted in Chapter 1). They defended one another to outsiders.46 Most important, they found ways to avoid confrontation. Each lent public support to the others' decisions, despite their differences.47 The leading positions of the five hubs were unequal and informal; but if the men stayed close, worries of confrontation might be set aside.

PERIPHERY AND FRINGE: NETWORK

INCLUSION AND EXCLUSION

Records of communication allow for an analysis of core relations in Theodoret's network, including the distribution of influence. They help in another way regarding the periphery. Core figures are named frequently in our records, but the majority of bishop members appear as minor players. Most clerics and laypeople are virtually invisible. Our map is, of course, incomplete, but it is suggestive about the effective limits of the core network. At ecumenical councils Theodoret and his associates spoke for “the East.” Some churchmen, however, remained aloof; others were excluded. And while the bishops recognized no regional rivals, they seem to have left space for an opposition to form.

Theodoret and his allies made bold assertions about their control of the churches of Syria, supported by a careful performance. During and after the First Council of Ephesus, Theodoret and his associates called themselves “the Bishops of the East.”48 No doubt they meant the civil diocese of Oriens, but they hinted at a wider oversight, extending to Persia and beyond. This claim was not total fantasy. In the 430s the Antiochenes mobilized bishops across the region, including most of the metropolitans. At key moments they claimed the support of seventyfive or more Syrian bishops (the majority of those recognized by the Nicene church).49 But more important than the numbers was how the bishops demonstrated their reach. Attendance at regional councils put geography on display. So did public correspondence. Not only did the bishops travel together to ecumenical councils; once present they tried to display unanimity. The performance had limits—it never included Cyprus or Palestine. But most allies and most opponents accepted the Antiochenes' regional label.

Our network map, however, challenges the performance of regional control. The seventy-five enumerated bishops leave out around forty or fifty (depending on when settlements gained bishoprics). Our list of member bishops includes just thirty actual names. Gaps can be found in every province, but Phoenicia I, Osrhoene, Mesopotamia, and Arabia seem especially underrepresented. None of these numbers include the thousands of clerics who never appear in correspondence. And even among the thirty stood peripheral figures whose links to the center may have been tenuous. The Antiochenes convinced some peers that they represented the East, but relational data do not support them.

One problem for the Antiochene network concerned clerics who kept their distance. Even big councils were missing bishops. Some protested their illness and named proxies.50 Others gave no explanation (see figure 6). Some of the missing bishops may have been unsympathetic to the network. One way for dissenters to avoid conflict was not to write and not to attend. Even if a bishop did participate, his subordinates may have avoided involvement. The aloofness of lower clerics is hard to measure, but it must have been substantial.

Another problem for the network involved clerics who were actively excluded. Some member bishops publicly repudiated the cues of doctrine and memory. The most famous defector, Rabbula of Edessa, had just died in 436, but others would soon follow. In the meantime the allegiance of many bishops in Osrhoene province was uncertain.51 Lower clerics and monastic leaders also defected. At least six in Antioch served as proxenoi for Cyril of Alexandria, staging protests into the 440s.52 Then there were the members who had been cast out during doctrinal confrontations. By 436, at least nine Antiochene bishops had been deposed, including Nestorius and Alexander of Hierapolis (and every non-Syrian member prelate). Several government allies now lived in exile, above all Count Irenaeus.53 Some members kept contacts with their punished brethren. What we know of these contacts make them seem tenuous or downright hostile.54

FIGURE 6. Map of Theodoret's known episcopal network, circa 436. Squares = metropolitan sees, large circles = major suffragan sees, small circles = minor suffragan sees, filled shapes = sees held by Antiochene members, empty shapes = non-members or unidentified bishops, thin lines = approximate provincial boundaries, thick line = approximate frontier of Roman Empire.

It is thus startling that Theodoret and his peers acknowledged no organized resistance within the Nicene church. John of Antioch tolerated the priests who reported against him. Even the defector Rabbula was officially restored to communion before he died. The bishops did worry about heretics—the Arians, Manichaeans, and Marcionites who gathered in homes and distant villages.55 But Nicene communities were treated publicly as partakers of concord. This may be a deliberate misrepresentation. As questionable clerics died or left, the bishops sought more reliable replacements. It also may stem from misperception. Most extant records come from core members, who may not have perceived how social life differed on the network fringe.56

It is also possible that in 436 there was no organized resistance so long as the Antiochene network appeared regionally dominant. Scale-free networks tend to persist in computer simulations. Multiple clusters and hubs make a network robust, so long as the inner circle remains united. They also tend to attract new nodes, which are clustered and drawn toward the hubs.57 Such observations do not explain the rise of the Antiochene network, but they may explain its staying power. Sometimes modular scale-free networks have such success that they monopolize a social space.58 Our network map leaves some scattered space for rivals, but it would take effort to link up these “gaps.”

Yet our map of the Antiochene network does show vulnerabilities. Simulated scale-free networks can withstand losses but fail spectacularly if a force systematically eliminates the hubs. Our map reveals only minor weak points. Gaps appear between the bishops of Cilicia, for instance, and those of coastal Syria. But larger problems may loom beyond view, especially among the bishops of Osrhoene and Phoenicia I. These apparent gaps, of course, prove nothing; they may appear accidentally because of the spotty data. But they do suggest where the network reached limits, which other evidence may confirm.

If these regions were, indeed, “gaps” for the Antiochenes, then the problems could be magnified by later social developments. If one figure came to dominate the network, for instance, it would be easier to target him and thereby split the coalition. Or if disgruntled clerics could canvass thin spots in the social fabric, they might find people willing to switch sides. No synchronic social map could predict if a network would collapse. But our map shows us what it might take to overturn the Antiochenes: a coordinated attack on all the most central figures and an effort to unite people in the gaps of the network periphery (see chapter 5).

PATTERNS, IMPLICATIONS AND UNCERTAINTIES

Mapping and analyzing Antiochene relations thus yields some noteworthy results. Our data trace a singular network spanning the region. The results fit a modular scale-free template (a loose periphery, a gradation of well-connected hubs). At the same time they feature a specific social arrangement (a tight central clique that included all five hubs). This shape says something about Antiochene leadership. In place of a clear order of deference, we find informal would-be leaders. The shape also says something about network inclusion. In the Syrian clergy, we find only scattered non-Antiochene “gaps”—just enough space for opponents to potentially organize.

Such observations, of course, beg the question: how well do these patterns reflect social experience? All the elements of this map are approximations, and some are more noteworthy than others. Our maps are representations, based on limited, edited evidence. They gloss over variations in perception and processes of change. Some patterns likely arise from the selective nature of the social data. The emphasis on bishops, for instance, is hard to separate from the fact that they collected most of our sources. Other patterns are more reliable, if unsurprising. The modular scale-free form appears in both data sets. This template offers useful, but nonspecific, guidance, since it may be found in any growing network. The most important results have to do with the finer social details: the spotty reach of the Antiochene periphery and the tight core surrounding five (unequal) hubs. Strikingly, these features cut against the official claims of our sources. They also offer suggestions about the specific nature of this network.

The next three chapters shall return to our map, when its features illuminate certain social events. Here, we note just a few parameters of interpretation. Network maps do not offer certain predictions. Simulations suggest only what is possible or likely, when a similar arrangement is found. Consider the modular scale-free topology. Modular scale-free patterns arise in simulations when small networks experience steady growth. As they expand, these networks gradually become more dependent on hubs, and thus more prone to collapse. These networks may become less hub-dependent and less vulnerable, but only if they cease growing (and thus cease to be modular and scale-free).59 These simulations tell us little about the origins of the Antiochene network, or the reasons for its virtual demise. They do not explain why certain members became hubs. They do suggest what it probably took to build the Antiochene network (steady growth). And they show us some of its possible futures.

Ultimately, the maps and models noted in this chapter merely beg further questions. How did Theodoret's network really form and grow? How did its members come to join and its leaders, to achieve centrality? How did the network deal with internal rivalries and external opposition? How reliable were its relationships? How potent was its sense of community? The next three chapters will address these questions, beginning with the network's historical roots.