George Rogers Clark—who was called the “Conqueror of the Northwest”—was born in Albemarle County in 1752. He was an older brother of William Clark, the youngest son of the Clark family’s ten children. William Clark’s five older brothers fought in the Revolutionary War, and two became generals: George Rogers and Jonathan. The Clark family lived near the Rivanna River in Albemarle County until they inherited property in 1756 and moved back east to Caroline County, where William was born in 1770.

In the 20th Century, William Clark would become famous as Meriwether Lewis’s partner in the expedition to the Pacific Coast, which was then called the “New Northwest.” But during the 19th Century, his older brother, George Rogers, was much more famous for winning the “Old Northwest” for the United States during the Revolutionary War.

Meriwether Lewis and William Clark were children during the Revolutionary War. Their families were “Patriots” or revolutionaries, rather than “Loyalists.” The country was about evenly split on this—about 1/3 Patriots, 1/3 Loyalists, and 1/3 undecided. It was natural for those who lived on Virginia’s frontier in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains to be Patriots. They wanted to cross over the Appalachian Mountains and settle in the lands claimed by Virginia, which extended all the way to the Mississippi River on both sides of the Ohio River.

The British had reserved the land west of the mountains for Indians at the end of the Seven Years War (1756–1763). Colonial militias, supported by troops from Great Britain, had won control of “New France,” in what was called the “French and Indian War” by Americans, but was actually an international war fought for control of the North American continent. New France stretched from Hudson Bay in Canada to the gulf waters of Louisiana.

The struggle for control of the lands west of the Appalachians is the story of the early American Republic. It starts with the French and Indian Wars between Britain and France and their colonies in the new world; and includes Spain as the third great power in the conflict. Indians fought on all sides—where ever they thought they had the best chance of holding onto their lands. Everyone believed they had a legitimate claim to the land. They were uneasy partners in shifting alliances, conspiracies, land speculation, wars, and filibuster expeditions during the American Revolution and for many years afterwards.

George Rogers Clark, computer generated image. George Rogers Clark National Historical Park (www.nps.gov/gero)

In 1772, 20 year old George Rogers moved to the Ohio River Valley, where he worked as a surveyor for the Ohio Company. Two years later, Clark served in the Virginia militia during Lord Dunmore’s War against the Shawnee and Mingo Indians. In 1776, when he was living at Harrodstown, Kentucky, he was elected as a representative of Kentucky County to the first Virginia General Assembly, the newly created legislative body replacing the House of Burgesses. After a journey of 700 miles to Williamsburg, he discovered the legislature had met and gone home. Clark then sought out the new Governor of Virginia, Patrick Henry, and obtained 500 pounds of gun powder for the defense of Kentucky against Indian attacks.

The British were supplying arms and ammunition to the Indians of the Ohio River Valley. The tribes had a combined force of about 8,000 warriors.6 Clark returned to Kentucky with the gunpowder in the early spring of 1777. Henry Hamilton, Lieutenant Governor of Canada and Commander of Fort Detroit—who was called the “Hair-buyer General”—was paying Indians for the scalps of Americans. In the summer of 1777 Hamilton employed fifteen bands of Indians to raid the isolated settlements of Kentucky, killing or capturing men, women and children, taking scalps, torturing, and burning their homes.7

Clark decided the best defense against the British and their Indian allies would be to capture the British forts at Kaskaskia and Vincennes in Illinois country, the land between the Mississippi, Wabash, Ohio and Illinois Rivers. Four French villages were located here, with a population of about 900–1,000 whites and over 600 black slaves.8

Though French residents had lived in the Mississippi Valley for generations, they were now under foreign rule. When France lost the Seven Years War in 1763, the vast lands of “New France,” were acquired by the British. The British then ceded Louisiana, the land west of the Mississippi River, to Spain in exchange for East and West Florida. French residents in the Mississippi Valley were governed by the British on the east bank, and by the Spanish on the west bank.

Clark wrote to Governor Patrick Henry:

We must either take the town of Kuskuskies or in less than twelve month send an army against the Indians on Wabash, which will cost ten times as much and not be of half the service.9

Kaskaskia was located on the east bank of the Mississippi near its junction with the Ohio. Clark sent spies, disguised as hunters, to the Illinois country, who reported the British did not suspect an attack by Kentuckians and the French were not happy with British rule.

Clark once again journeyed to Williamsburg where he received permission from Governor Patrick Henry to mount a secret expedition to capture Kaskaskia.10 He was appointed a lieutenant colonel with instructions to raise seven companies (50 men each) of militia for the defense of Kentucky. In May, 1778 Clark set out from Pittsburgh with about 150 militia volunteers, some private adventurers, and twenty families in a flotilla of flat boats bound for the Falls of the Ohio near present day Louisville, Kentucky.

The Falls of the Ohio were a strategic location, as boats were unloaded there to pass through the 20 foot drop of the rapids. Clark established a settlement on Corn Island, a 70 acre island in the middle of the rapids, where he revealed his secret plan to capture Kaskaskia. The island was to serve as a communications post during their expedition into Illinois country. The families, consisting of 60 civilians, were to raise corn on the island. A blockhouse was built for their defense. Corn Island was the founding settlement of Louisville, Kentucky.

In June, 1778 a messenger from Pittsburgh arrived with the news that France had joined in an alliance with the United States, and Clark set off to capture Kaskaskia with 175 men, chosen for their hardiness.

When they reached the Tennessee River they left the Ohio River and traveled overland, thus escaping discovery by the British and their Indian allies. Marching in single file like Indians and dressed in buckskins and hunting shirts, they arrived at the Kaskaskia River opposite the village of Kaskaskia on the evening of July 4th. Crossing the river in boats, they captured the British commander at his home without firing a shot. The fort had been destroyed by fire some years earlier.

The town of Kaskaskia, founded by Jesuits in 1703, was the capitol of Upper Louisiana during the French colonial administration. Its residents were mixed blood descendants of French traders who married women of the Illinois and other tribes. Black slaves, originally from Saint Domingue (Haiti), worked in the lead mines across the river. The men were voyageurs who traded for furs in Indian country, and farmers who grew corn and wheat for Lower Louisiana, shipping tons of flour to New Orleans annually. In 1763, at the close of Seven Years War between Britain and France, the residents of Kaskaskia became the subjects of Great Britain. Many had moved across the river to live in French towns under Spanish rule.

Clark met with the village leaders and explained they would be free under American rule, telling them the news that France had become an ally of America in the Revolutionary War. He assured Father Gibrault, the village priest, that the Catholic Church would be protected under Virginia’s laws of religious freedom. Clark wrote:

In a few Minutes the scean of mourning and distress was turned to an excess of Joy, nothing else seen or heard—Adorning the Streets with flowers and Pavilians of different colours, compleating their happiness by singing etc.11

The King of France had given them a bronze bell for their church in 1743. The bell was rung on July 4th to celebrate their liberation from British rule, and it became famous as the “Liberty Bell of the West.”12 The residents of Cahokia and Prairie de Roche, the French towns north of Kaskaskia, also took oaths of loyalty to the United States.

Pierre Gibault, S. J., the “Patriot Priest,” and the Liberty Bell of the West at Kaskaskia, Illinois. ( Indiana.gov and photo by Rick Blond).

Father Gibault went east to Vincennes on the Wabash River to persuade its residents to join the American cause. The local militia—Vincennes residents who were guarding the fort in the absence of British troops—switched sides and hoisted a new, homemade American flag over Fort Sackville.

Clark visited Fernando de Leyba, the Spanish Governor in St. Louis. The governor, newly arrived from Spain, agreed to support the Americans and French in the event of Indian attacks. Spain joined the war against Britain in June, 1779, in order to regain its possession of the two Floridas.

Without money to pay for his expedition, Clark was signing bills of credit, payable by the state of Virginia. These bills were honored by Oliver Pollock in New Orleans, who paid $8,500 in silver to Illinois merchants. By January, 1779 Clark had received an additional $30,000 worth of supplies from Pollock, who was instructed by the Commercial Committee of Congress to give all possible support to Clark. At the end of the Revolutionary War, these bills would be disastrous for both men.13

For five weeks, in August and September, 1778, Clark held an Indian council at Cahokia, the French town across the river from St. Louis. Ten or twelve tribes from 500 miles around attended the gathering. During the council, two Winnebago Indians attempted to kidnap Clark, but instead they were seized and imprisoned. The French rallied to support the Americans—which impressed the Indians—and while the tribes were deciding how to proceed, Clark wrote that he:

… assembled a number of Gentlemen and Ladies and danced nearly the whole night.

After that, he declared to the Indians that he came as a warrior not as a counselor, and peace or war would be their choice. They chose peace, and Clark allowed the two prisoners to go free. For years afterwards the tribes preferred to deal with Clark.14

In December, 1778, the British “Hair-buyer General” Henry Hamilton—upon learning of the surrender of the fort at Vincennes—marched from Detroit with a force of over 200 British regulars and French militia, and about 300 Indians to retake the fort.15 When they arrived, the residents of Vincennes switched sides again. Four Americans at the fort were captured. Most of Hamilton’s French militia returned to their homes in Detroit and Hamilton sent the Indians out to raid Kentucky settlements. He planned to winter at the fort and renew his campaign against the Americans in the spring.

Francis Vigo, a St. Louis merchant sent out by Clark to provision the fort, was at Vincennes when it was recaptured by the British. Not suspecting that Vigo was a friend of the Americans, Hamilton allowed him to return to St. Louis.

On January 29th, Vigo met with Clark at Kaskaskia and gave him detailed intelligence. Clark decided to risk everything and retake Fort Sackville in the dead of winter. If he didn’t, Hamilton’s spring campaign, utilizing large numbers of Indians, would destroy the Kentucky settlements.

On February 5th, Clark sent a gunboat with 46 men down the Mississippi and up the Ohio and Wabash Rivers with orders to wait for them near Vincennes. The boat carried heavy artillery and armaments.

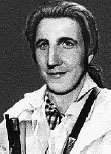

March to Vincennes by F. C. Yohn (Wikimedia Commons)

On February 6th, Clark set out with 130 men—sixty of them French volunteers—from Kaskaskia to march to Vincennes.16 The men traveled 180 miles across icy flood plains, often in rain, through mud and water several inches deep. What they endured is the stuff of legends. Clark wrote about their journey through the “drowned lands”—

It was difficult and very fatiguing marching. My object now was to keep the men in spirits. I suffered them to shoot game on all occasions and feast on it like Indian war-dancers—each company, by turns, inviting the others to the feasts….myself and principal officers … running as much through the mud and water as any of them. 17

As they neared Vincennes, they went two days without food. Game had fled the flooded area of the Wabash River and its streams. On February 23rd, six miles from Vincennes, Clark led the way into a shallow lake, four miles wide. He placed an officer with 25 men at the rear, with orders to shoot anyone who refused to march. In a wooded area, the water reached the shoulders of the tallest men, and they clung to trees and logs waiting to be rescued by two canoes.

After reaching dry land, large fires were built and soup was made from buffalo meat, corn, and tallow—the food and kettles appropriated from Indian women and children passing by in canoes. Camped within two miles of the fort, they took prisoners of five French hunters. The hunters were friendly and reported their presence was unsuspected.

Clark sent the hunters—who were unaware of how few men he had—back to the village with a letter. Clark’s letter, read in the public square, warned the villagers to keep off the streets that night as the fort was going to be attacked. No one told Hamilton, but the American prisoners at the fort were alerted.

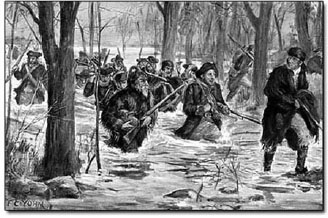

At sunset, Clark marched his men back and forth behind small hills with flags flying on tall poles, to persuade the villagers that he had a force of 1,000 men. When it was dark they approached the fort in two divisions, guided by the hunters. A few shots were fired, wounding one British soldier. It was only then that Hamilton realized he was under attack. The surprise was complete.

Sharpshooters with long rifles killed and wounded several men inside the fort during the night. At daybreak, Clark’s men had their first real meal in six days. In the morning, Hamilton sent word he wanted a three day truce. Clark demanded unconditional surrender. The British had been tricked into thinking their attackers were more numerous, by the firing, noise and shouts coming from different directions. There were about 40 British soldiers and 40 French militia from Detroit inside the fort, with provisions enough for six months and more men on their way as reinforcements. But the bluff worked.18

While Clark and Hamilton were holding talks at a nearby church, a war party of about 20 Indians and two Frenchmen, returned to the village bringing scalps and two prisoners. They had come from raiding settlements in Kentucky. The British flag was flying over the fort. Firing a salute, they shot their rifles in the air and were defenseless when Clark’s men opened fire, wounding and killing most of them. The two prisoners were released. One of the Indians, the 18 year old son of Pontiac, Chief of the Ottawa, was recognized and not harmed. The two Frenchmen were saved because the father of one of them was serving in Clark’s army, and the other had a sister living near Vincennes who begged for his life. Clark allowed a man—who had lost his family in a brutal Indian attack—to scalp and tomahawk the remaining four Indians in full sight of the men in the fort.19

General Hamilton signed an unconditional surrender agreement, effective the next day, February 25th, 1779. British supply boats approaching the fort were captured and six tons of supplies were divided among the troops. The French militia at the fort were sent back to Detroit, and General Hamilton, his hated Indian Agent Jehu Hay and 25 other British prisoners were escorted across the Kentucky settlements to a prison at Williamsburg, where the general was put in irons and treated as a common prisoner. Thomas Jefferson, now the Governor of Virginia, refused to see him.20

George Rogers Clark’s daring expedition to capture the British forts in Illinois country is credited with doubling the size of the United States, as the British ceded all their land claims west of Pittsburgh to the Mississipi River at the Treaty of Paris in 1783. After the claims of the states were settled, this land became the Northwest Territory in 1796.

Fall of Fort Sackville, 1779, by Frederick Yohn. (Wikimedia Commons)

Wabash River near George Rogers Clark Memorial in Vincennes, Indiana. (Photo by Rick Blond)

George Rogers Clark Memorial in Vincennes, Indiana.

George Rogers Clark statue.

Francis Vigo statue.

For more about the George Rogers Clark National Historical Park see www.nps.gov/gero. (Photos by Rick Blond)

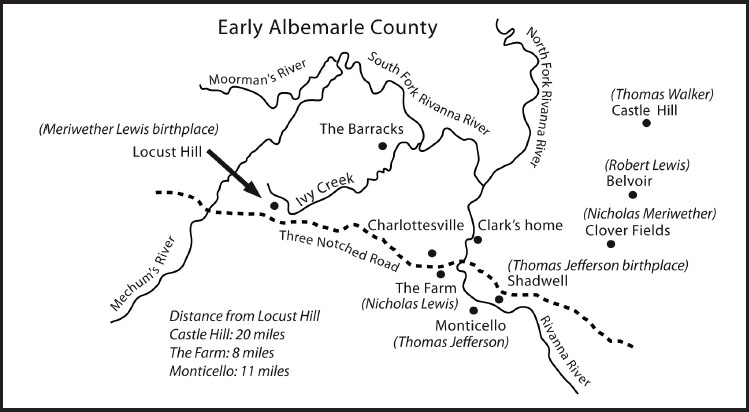

Early Albemarle County: map based on map on the “Lucy Meriwether Lewis Marks: Her Life and Her World” section of www.monticello.org website.