When Meriwether Lewis was an infant, his father was away from home fighting as a Patriot. His father served as an unpaid volunteer in the Revolutionary War. Because he received no pay and paid his own expenses, there are few military records for William Lewis. He died in 1779, while on military leave in Albemarle, when Meriwether was only five years old.

William Lewis joined the First Independent Company of Albemarle County in April, 1775. The “gentlemen soldiers” pledged to muster four times a year—or oftener if necessary; to provide their own gun, shot-pouch and powder horn; and to appear on duty in a hunting shirt. Lewis, and 26 others of the Albemarle volunteers rode to Williamsburg in May, in response to the “Gun Powder Affair.” 21

Lord Dunmore, the Royal Governor of Virginia—reacting to Patrick Henry’s “Give me liberty or give me death” speech—seized the gun powder stored at Williamsburg. It marked the beginning of the end of British rule over Virginia. In June, Lord Dunmore and his family fled to the safety of a British naval ship; and George Washington was appointed Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army by the United Colonies.

In September, William Lewis became a lieutenant in the Albemarle Minutemen under the command of his older brother, Captain Nicholas Lewis, who was a close friend of Thomas Jefferson. The Minutemen were an elite force, ready to go into battle in a “minute.” 22 Lewis may have remained a lieutenant in the Albemarle Minutemen, and never officially joined the First Virginia Regiment of the Continental Line because he was serving at his own expense.

The Albemarle Company fought Dunmore’s loyalist troops in December, and became part of the First Virginia Regiment of the Continental Line in February, 1776.23 They fought the Loyalists until the British abandoned Virginia in August. They were at Morristown in the winter of 1776–77; fought at Brandywine and Germantown in 1777; wintered at Valley Forge in 1777–78; and fought at Monmouth in 1778.

Meriwether’s mother, Lucy Meriwether Lewis, was a well-known “yarb doctor.” She was famous for her herb-doctoring, tending to the sick, including the slaves, of the Albemarle community. While her husband was away at war, she managed their tobacco plantation and its 24 slaves. George Gilmer, a neighbor both in Virginia and Georgia, wrote:

Her person was perfect and her activity beyond her sex. She was sincere, truthful, industrious, and kind without limit.24

Lucy Meriwether Lewis Marks in her old age. (Wikimedia Commons)

Gilmer wrote about the Meriwether clan, who had emigrated from Wales:

They brought more wealth with them to Virginia than was usual for emigrants in the seventeenth century. Most of them were peculiar in manners and habits; low and stout in stature, with round heads, dark complexion, and bright hazel eyes. They were very industrious and economical, and yet ever ready to serve the sick, and those who needed their assistance. They were too proud to be vain. They looked to their own thoughts and conduct rather than to what others might be thinking of them… No one ever looked at, or talked with one of them, but he heard or saw something which made him listen, or look again. They were slow in forming opinions, and obstinate in adhering to them. They were very knowing. But their investigations were minute and accurate rather than speculative and profound. Mr. Jefferson said of Col. Nicholas Meriwether that he was most sensible man he ever knew.25

Nicholas, the oldest son of Thomas Meriwether, was brave in danger and self-possessed in the most difficult situations. He was one of four Americans who bore the wounded Braddock from the field of battle at his disastrous defeat. A gold-laced, embroidered coat sent him from Ireland, by General Braddock’s sister, remained for a long time a curiosity in his plain household.26

In January, 1779, there was more than a British general’s coat hanging on the wall at Clover Fields, there were 4,200 British and German prisoners of war living in Albemarle County. They were called the “Convention Army” because General John Burgoyne, their commander, had been allowed to sign a “treaty of convention” rather than a treaty of unconditional surrender. The terms of the treaty were that officers would sign an agreement “on the condition of not serving again in North America during the present contest.” The troops were to exit America from Boston. However, George Washington opposed these terms, objecting that they would ship right back to America again. The Continental Congress decided they would remain in America, and they were moved to a series of different POW camps.

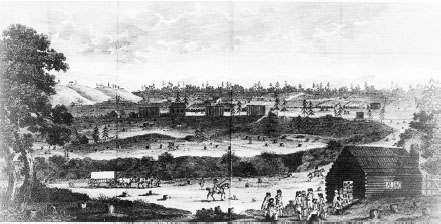

Almost 4,000 POW’s arrived at Albemarle in January, 1779. Their arrival was unexpected; but by March, Jefferson was writing their living conditions were much improved—their camp was on a high hill, with convenient access to spring waters and several nearby flour mills. The officers were renting and renovating homes in the area, and the soldiers had laid out hundreds of fenced garden areas at the Barracks. They had chickens and pigeons. The Germans were provided with 200 pounds of vegetable seeds by General Riedesel, their commanding officer, who had rented a vinyard estate for his family near Monticello.27

In April, Albemarle citizens signed a “Declaration of Independence,” renouncing King George III and pledging their allegiance to the Commonwealth of Virginia. William Lewis was the third signer on the document. Albemarle’s population had almost doubled with the arrival of the Convention Army, and—with their officers and families living in the community—they felt a need to reaffirm their loyalty to the Patriots.

In May, the First Virginia Regiment was consolidated with other Virginia regiments, and in the summer they fought under General Anthony Wayne at the Battle of Stony Point. In November, Lieutenant Lewis was in Albemarle on military leave.

Lewis was returning to his unit based in Yorktown when his horse drowned in the flooded Rivanna River. He was able to swim across the river, but caught a chill. He went to his wife’s old family home, Clover Fields, where he died of pneumonia on November 14th, 1779. Because of the flooded river he was buried at Clover Fields. On his death bed, he advised his wife that if Captain John Marks should come courting, she should marry him.28

Captain Marks, who had commanded a company at Valley Forge,29 did come courting and on May 13, 1780, he married Lucy and became stepfather to Meriwether, age five; Jane age nine; and Reuben, age two.30

A few months later, the Convention Army was forced to leave Albemarle. The American military command was worried that the British army was going to invade Virginia. The coastal town of Yorktown—where Lieutenant Lewis had been based—guarded the entrance to Chesapeake Bay, the key to Baltimore and Washington D.C. as well as Virginia. In 1779 there were several British raids at Yorktown.31

Major Thomas Asbury, a British POW, wrote to friends on November 20, 1780:

About six weeks ago we marched from Charlottesville barracks, Congress being apprehensive that Cornwallis in overrunning the Carolinas might by forced marches retake the prisoners. The officers murmured greatly at the step, having been given to understand they were to remain until exchanged. Many had laid out considerable sums to render their huts comfortable, particularly by replacing the wood chimneys with stone, and to promote association, they had erected a coffee house, a theatre, a cold bath, &c. 32

The Surrender of General Burgoyne at Saratoga by John Trumbull. A Virginia “shirt man,” Colonel Daniel Morgan is given the place of honor in the painting. Morgan’s Riflemen were crucial in winning the battles of Freeman’s Farm and Bemis Heights, a turning point in the war. Burgoyne is shown surrendering his sword to General Horatio Gates. A young James Wilkinson may be seen behind Gates’s outstretched hand. Wilkinson, age 20, actually conducted the negotiations with Burgoyne. (Wikimedia Commons)

The Barracks: The Convention Army encampment at Albemarle. (Wikimedia Commons)

A few weeks later, on January 5, 1781, Brigadier General Benedict Arnold—who had switched sides and joined the British Army—led 1,600 American Loyalists in a raid on the new state capitol at Richmond. They burned buildings and destroyed government papers. For many years, it was believed George Rogers Clark’s expense records from the Illinois campaign were destroyed in this attack.33

Arnold continued to lead raids in the Richmond area over the next months, joined by troops under the command of Major General Phillips, who had recently been a prisoner of war at Albemarle. In late May, Lord Cornwallis, commander of British forces in the South, arrived with his troops. There were now 7,200 British and Loyalist soldiers in Virginia.

Jefferson—who served for two years as Governor of Virginia—and the Virginia General Assembly met for the last time on May 10th in Richmond, and then fled to the safety of Charlottesville, where they convened again on May 24th.34 They were pursued by Lieutenant Colonel Banastre Tarleton, known as “Bloody Ban” for his terror tactics. Tartleton had been ordered to go to Charlottesville and capture the notables assembled there, especially those who had signed the Declaration of Independence—Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Harrison, Richard Henry Lee and Thomas Nelson, Jr.35

Tarleton moved quickly with a force of 250 soldiers, including 180 American Loyalists wearing green coats called the “Green Dragoons.” On June 3rd, when Tarleton’s men stopped at Cuckoo’s tavern in Louisa County, Jack Jouett, an Albemarle militia man, realized what was about to happen, and made a ride that rivals Paul Revere’s ride in American history. Jouett, a giant of a man at 6’4,” took the fastest horse in seven counties, and rode 40 miles through the night to warn Jefferson of Tar leton’s impending arrival. He reached Monticello before dawn on June 4th and then went to Charlottesville to warn the assemblymen.36 Charlottesville consisted of about 12 houses, a tavern and courthouse along Three Notched Road.37 The assemblymen agreed to meet again in three days time at the town of Staunton on the other side of the Blue Ridge Mountains.

When Tarleton and his troops reached Albemarle, they demanded breakfast at Castle Hill, a plantation owned by Dr. Thomas Walker. The Walkers delayed the British as long as possible. When the dragoons got to Charlottesville, they encountered Daniel Boone, loading records from the courthouse into a wagon. Boone was serving as Kentucky’s representative at the assembly. They didn’t realize who he was because he was dressed in a hunting shirt—until Jouett forgot and called him “Colonel.” Jouett escaped, but Boone was captured. Boone spent the night of June 4th locked in a coal shed at “The Farm,” where Tarleton was staying.38

The Farm was the home of Meriwether’s uncle, Nicholas Lewis, who was away fighting in the war. Why Boone was released the next day is a matter of speculation, but it may have been that a relative of Boone’s wife, serving in Tarleton’s regiment, secured his release. Tarleton’s men took all of the Lewis family’s flock of ducks except one. After they left, Mrs. Lewis sent a servant with the one remaining duck to Tarleton.39

Tarleton’s men treated Monticello respectfully, perhaps in recognition of the good treatment the Convention Army had received. Jefferson sent his family and several important guests away from Monticello, but took his own time in safeguarding his papers and getting his favorite horse shod. After he spied green coats with his telescope, he left Monticello with only a few minutes to spare before they arrived.40

Patrick Henry was another one of the assemblymen who escaped to Staunton ahead of Tarleton. The story is told that when he and two others stopped at a house to get some food, the woman scolded them and said if Patrick Henry had been there, he never would have run away. His friends laughed, and revealed his identity.41

Jefferson’s term of office was up in June, and he refused to serve again, saying that Thomas Nelson, Jr., a militia general from Yorktown was better suited to govern Virginia. The final, decisive battles of the Revolutionary War, took place in Virginia, ending with the surrender of Cornwallis at Yorktown on October 19, 1781.

How did all of this affect Meriwether Lewis? He grew up in wartime and lived at one of its centers, due to the presence of Thomas Jefferson. His father had died and was buried at Clover Fields; there was a prisoner of war camp at the other end of Ivy Creek, and he had a stepfather serving in the war. But he was—after all—a Meriwether and a Lewis, and he was surrounded by a close knit family of relatives.

There are several stories about his mother that have come down to us. One story is that Lucy used a gun to scare off some drunken British officers from the POW camp when they came to Locust Hill. Another story is that a party of deer hunters went out from Locust Hill to get some deer, but had no luck. When they got back, they found Lucy had shot a deer in her back yard, skinned and dressed it, and had it cooked and waiting for them. Her hams were famous, and Jefferson bought several a year from her, although he smoked his own hams at Monticello.42

Jefferson wrote about Meriwether Lewis, as a young boy:

At first [he] went to common day schools, learning to read, to write & Arithmetic with ordinary facility, he was early remarkable for intrepidity, liberality & hardihood, at eight years of ago going alone with his dogs at midnight in the depth of winter, hunting wading creeks when the banks were covered with ice & snow. He might be tracked through the snow to his traps by the blood which trickled from his bare feet.43

Meriwether would have been eight years old in the winter of 1782–83 when he was hunting raccoons at night. The peace treaty with Great Britain was signed in 1783, and war veterans began to make plans for the future.

John Marks, Lucy, and Lucy’s youngest son Reuben moved to Georgia in 1785. The year before some Albemarle men had gone to Georgia to look at land in the Piedmont area of North Georgia. Marks was elected Sheriff of Albemarle County in 1785, but he decided to move to Georgia, leaving the post vacant.44 He purchased land near the other families from Albemarle along the Broad River in Wilkes County.

Meriwether and his older sister Jane remained behind in Albemarle. Jane had gotten married at age 15. Meriwether was 11 years old, and near the age for advanced schooling. Jefferson wrote that he was left in the care of a family guardian:

At eleven years old he was taken from his mother and remained until thirteen with his guardian, when he was past [his 13th birthday] to Latin schools kept by Dr. Everett, Parson Maury & Parson Wardell.45

Meriwether’s guardian was his 24 year old cousin, William Douglas Meriwether, a surveyor.46 Meriwether lived at Clover Fields with his cousin, who had inherited the property from his father, Nicholas Meriwether, Lucy’s brother. His father’s brother, Nicholas Lewis, lived close by at The Farm and served as his unofficial guardian. Nicholas Lewis, whose land was adjacent to Monticello, was acting as Jefferson’s business agent while Jefferson served as Minister to France in 1784–1789.

The Locust Hill plantation had been left in the care of an overseer. Due to Virginia’s Law of Primogeniture, Meriwether, as the eldest son of his father, inherited the entire property when his father died. It would remain in the care of his mother until he came of age. Lucy, as his father’s widow, had dower rights to the use and income from one third of her husband’s estate during her lifetime.

Meriwether visited his mother and stepfather in Georgia, in 1790 when he was 16 years old. Peter McGhee, an Albemarle neighbor who moved to Georgia with the Marks family related:

In the section of the country in which they were the Indians sometimes made incursions, committed murders and carried off property. An alarm of Indians on the warpath got out creating great alarm, the neighbors met and consulted as to what they should do; they determined that they could not defend themselves, could easily be burned out, they determined the best thing, the only thing would be to take to the woods, they selected a situation made a large fire while assembled around it at night, a gun was heard not far off, a cry of Indians excited great alarm, mothers caught up their children and were weeping, when a boy in the crowd threw a bucket of water on the fire put out the light, in a moment all was quiet and a sensation of safety was felt by all, that boy was Meriwether Lewis.47

Meriwether’s half brother and sister, John Hastings and Mary, were born in Georgia. Their father, John Marks, died in 1791. After his stepfather died, Meriwether had to assume his responsibilities as head of the family. The 17 year old was in Virginia studying at a classics school run by Reverend James Waddell, a famous teacher known as the “Blind Reverend.” Patrick Henry said the minister was one of two of the greatest orators he ever heard.48 In April, 1792, Lewis quit school. The next month he went down to Georgia to escort his mother and the three children back to Locust Hill.

Meriwether had previously studied with the Reverend Matthew Maury, the son of Thomas Jefferson’s teacher, in 1788–89. In 1790 he studied with an Albemarle physician, Dr. Charles Everitt. One of Lewis’s classmates at Dr. Everitt’s school, left this description of him:

Meriwether Lewis, afterwards distinguished for his expedition up the Missouri was one of our classmates. He was always remarkable for perseverance which in the early period of his life seemed nothing more than obstinacy in pursuing the trifles that employ that age: a martial temper: a great steadiness of purpose self-possession, and undaunted courage. His person was stiff and without grace, bow legged, awkward, formal and almost entirely without flexibility: his face was comely & by many considered handsome. It bore to my vision a very Strong resemblance to Bonaparte.49

Meriwether managed the farming operations at Locust Hill, but adventure called to him, and the military life appealed. In 1794, when he was twenty years old, he joined the Virginia militia which had been called up by President Washington to put down the tax protest known as the “Whiskey Rebellion” in western Pennsylvania. The militia of four states had been called up in the first test of federal power to use state militia to put down internal rebellion.

Thomas Jefferson wrote his recollections of Lewis’s life from 1794 to 1801:

From eighteen to twenty he remained on his farm an affectionate son and assiduous and devoted farmer, observing with minute attention all plants and insects which he met with. In his twentieth year he joined a volunteer corps as a private under T. Walker against the insurgents. During the same year he was appointed lieutenant in the U.S. army. In his twenty third year he was promoted to a Captaincy and returned to Albemarle to recruit. He again joined the army and acted as paymaster until he was made private secretary to the President.50

He got his facts a little bit mixed up regarding Lewis’s military service, but the observations about Lewis’s dedication to farming and interest in nature ring true.

The center of the Whiskey Rebellion was south of Pittsburgh, in the area bounded by the Monongahela River on the east and the Ohio River on the west.

THE LIBERTY POLE

The Liberty Pole was often erected during the American Revolution. It was a pole stuck in the ground and topped with a red “liberty cap,” or a red flag. The Phrygian cap dates back to the Roman Empire, and is found on the seal of the United States Senate. Liberty poles were erected along the roads and town squares of the western counties during the Whiskey Rebellion. (Wikimedia Commons)