The case will be made in this book that General James Wilkinson was responsible for the assassination of Meriwether Lewis and others. For this reason, the story of Wilkinson’s activities—before he meets Meriwether Lewis in 1795—needs to be told.

Wilkinson dominated the western frontier from the time of his arrival in Kentucky in 1783 until his death in Mexico City in 1825. He is one of the most complex and intriguing figures in American history. No less a historian than Frederick Jackson Turner called Wilkinson, “the most consummate artist in treason the nation has ever produced.” However, a study of his career has convinced me that he was a double agent, a scapegoat, and a patriot—as well as an assassin. I call him a “patriotic sociopath.” There have always been mixed sentiments among historians about Wilkinson. With access to historic documents and the use of search functions on the internet, it is much easier to construct a nuanced version of his life.

Wilkinson wrote a massive three volume set of books called Memoirs of My Own Times, published in 1815. Much of it was material he assembled in his own defense during a series of congressional investigations and military courts-martial—all of which ended with his acquittal. On the title page of his books, he provided a quote from the English poet Richard Savage:

For patriots still must fall for statesmen’s safety,

And perish by the country they preserve.

The implication is that he has been scapegoated to protect higher ups and feels victimized, although he is still a “patriot.”

General Wilkinson entered Lewis’s life after Lewis joined the Legion of the United States in 1795. (The Legion would be come the United States Army the next year.) In 1795, Wilkinson was 38 years old and second in command to General Anthony Wayne, commanding general of the legion. Wilkinson was Wayne’s mortal enemy and a mortal enemy to George Rogers Clark—although apparently Clark didn’t know it. From this time on, he is a pivotal figure in Lewis’s life and he would become his mortal enemy also.

Wilkinson was smart, manipulative, and intent on achieving power. He was vain, charming, and lied easily. He knew how to throw a good party and loved music and dancing. Although he drove his superiors to distraction with lengthy and verbose reports, he was a responsible army officer, who didn’t shirk hard work and frontier assignments. He was interested in science, exploration, horticulture and maps, and was elected to the American Philosophical Society.

He had been born in 1757 on a plantation near Benedict, Maryland, forty miles southeast of Washington, D. C. When he was six years old his father died. As the second son, James was not entitled to inherit any property, and at 14 he was apprenticed to a family relative to begin the study of medicine. At 17 he went to Philadelphia to finish his medical studies, and it was there that he met his future wife, Ann Biddle, the daughter of a prominent Quaker family. After a few months of practicing medicine in Maryland, he enlisted in the American army in 1776.

Wilkinson rose to power during the Revolutionary War, serving as an aide to Generals Nathaniel Greene, Benedict Arnold, Arthur St. Clair, and Horatio Gates in 1776–1777, when he was 19 and 20 years old. After the Battle of Saratoga, General Gates allowed Wilkinson to conduct the surrender negotiations with British General John Burgoyne. Gates sent Wilkinson with a copy of the surrender terms to the Continental Congress and recommended that he be promoted from the rank of lieutenant-colonel to brevet brigadier-general for his services, calling him a “military genius.” 65

Wilkinson was accused of shamefully delaying his travels (taking 11 days to travel 285 miles) to reach Congress, which was meeting at York, Pennsylvania. News of the surrender reached York before he did. En route to York, he visited “his beloved” Ann Biddle at Easton, and met with Major-General William Alexander (Lord Stirling) and his aides Major James Monroe and Colonel William McWilliams at Reading. As he traveled, Wilkinson discussed General Gates and the “Conway Cabal” with several more high ranking officials.66

Thomas Conway (Wikimedia Commons)

General Horatio Gates (Wikimedia Commons)

Thomas Conway was a French army officer and a native of Ireland. He came over with the young Marquis de Lafayette and other volunteers to serve in the American army. Given a commission as a major general, Conway joined in a conspiracy to have General Gates replace George Washington as commanding officer of the army. There was also a plan for the army to invade Canada under French leadership. Many members of Congress supported the removal of Washington and the invasion of Canada, without realizing the French officers planned to betray the American army and take control of Canada for France.

The story was that Wilkinson had gotten drunk and told Colonel McWilliams about a letter written by Conway to Gates, in which Conway had written disparagingly of Washington:

Heaven has been determined to save your country, or a weak General and bad counsellors would have ruined it. 67

McWilliams was treasurer of George Washington’s Masonic lodge in Fredericksburg.68 Excerpts of the letter reached George Washington quickly, and Washington used the information to discredit his opponents.

Conway resigned from the army, and the invasion of Canada was halted, due to Lafayette’s loyalty to General Washington. The young Lafayette had agreed to lead the army in the Canadian campaign, not realizing that his own French officers were part of a cabal to overthrow Washington. He insisted he would take orders only from Washington, and he appointed officers loyal to Washington, breaking up the conspiracy.69

Wilkinson acted as a secret agent in conferring with the Biddle family and army officers loyal to Washington as he traveled to York. Although General Gates had allowed him to conduct the surrender negotiations with Burgoyne’s army, it had not blinded Wilkinson to Gates’s disloyalty to Washington, and he became a pivotal figure in exposing the French cabal and Gates’ involvement with it.

The idea that Wilkinson was actively supporting Washington is a controversial one, as historians have said that he unintentially revealed the plans of Conway and Gates because he was drunk. However, the clue is that he met with the Biddle family before his so-called drunken revelations. Clement Biddle, Ann’s older brother, was a close friend of George Washington.

As a reward for negotiating the British surrender, the twenty year old Wilkinson received his commission as brevet brigadiergeneral. However, his irregular promotion made Wilkinson a target for officers and congressmen who were opposed to General Washington, and Wilkinson decided to resign from the army in March, 1778.

He and Ann Biddle were married in November, 1778. She was 36 years old and he was 21.The Biddles were Patriots. Ann’s two army officer brothers, Clement and Owen, had been expelled from Quaker meeting because of violating their religion’s belief in pacifism and Ann was expelled because she married outside her faith. Their marriage took place at the Anglican Christ Church in Philadelphia.70 Fifteen signers of the Declaration of Independence worshipped at this church.

James Wilkinson (1757–1825)

Ann Biddle Wilkinson (1742–1807)

from Tarnished Warrior: Major-General James Wilkinson by James Ripley Jacobs

In July, 1779, the 22 year old Wilkinson was appointed Clothier-General of the U.S. Army. He took the job, even though it needed a drastic overhaul in its procedures and he had little interest or experience in business. The next month, he purchased Trevose Manor, an “attainted estate” confiscated from a Loyalist, located 18 miles northeast of Philadelphia.

He joined the Masons and became Master of the Dancing Assembly in Philadelphia. General Washington was not pleased that his new Clothier-General preferred the social life of Philadelphia to his army duties. Wilkinson resigned his post in March,1781 after making recommendations for improving the department. Their first child, John Biddle, was born in 1781; their second, James Biddle, in 1783. Wilkinson became a brigadier general in the Pennsylvania militia and entered politics, serving in the Pennsylvania state assembly for two years. At the end of the war in 1783, he made his first trip to Kentucky where he purchased land.71

The family moved to Lexington in the heart of Kentucky’s blue grass country in 1784. Wilkinson entered business selling general merchandise for a large Philadelphia firm, Barclay, Moylan & Company. He speculated in land, buying land for himself and others. He traveled widely, and said he knew more about “western lands than any Christian in America,” purchasing everything from town lots to tracts of 60,000 acres.72

They had moved to one of the most dangerous places in the country—Kentucky. More than one third of the Kentucky militia had lost their lives in the “Last Battle of the Revolution” at Blue Licks in August, 1782. Nearby Bryan’s Station at Lexington had been the Indians’ original target, but was so stoutly defended that the Indians retreated. The militia followed the Indians, and at least 77 militia men were killed in an ambush by 400–600 British-led Indians. It was the worst American defeat during the Revolutionary War on the frontier.

George Rogers Clark—now a brigadier-general in the Virginia militia—was in charge of defending Kentucky and the Illinois Country. He was blamed for the defeat, even though he wasn’t at Blue Licks. He was at Fort Nelson at the Falls of the Ohio, which he had built as the key defensive post for the western country. Militia leaders accused Clark of being drunk and incompetent, to shift the focus from their own refusal to heed his advice and their own poor judgement in allowing themselves to be trapped in an ambush.73

In 1784, Jefferson succeeded in having Clark appointed as one of five Commissioners for Indian Affairs to treaty with the Indians of the Northwest.74 Clark also supervised the surveying of bounty lands granted to veterans of the Illinois Regiment and Virginia State Line. Clark made his home at Clarksville, at the Falls of the Ohio on his own bounty lands grant.75

The Indian attacks continued. A report to the Secretary of War in 1790 stated that in the six years between 1784–1790, 1,500 residents of Kentucky were killed by Indians; and 20,000 horses and property worth 15,000 pounds of sterling had been stolen or destroyed by the Indians.76

Reenactors on the front porch of George Rogers Clark’s reconstructed log cabin overlooking the Falls of the Ohio at Clark’s Point in Clarksville, Indiana

In early 1786, 400 American residents at Vincennes—located on the Wabash River in Illinois Country—appealed to General Clark and Patrick Henry, the Governor of Virginia, to come to their aid in defending Vincennes against Indian attacks. Vincennes had been the scene of Clark’s victory over the British in 1779. The governor authorized the counties in Kentucky to draft militia to attack the Shawnee Indian towns near Vincennes. Shawnee warriors had been terrorizing Kentucky settlements as well as Vincennes.77

General Clark and Colonel Benjamin Logan were each to command half the militia draftees raised in Kentucky. Clark, led an army of 1,200 men from Clarksville. As they marched towards Vincennes, 200 men mutinied over food supplies. The militia were not required to serve out of state, and there were no federal troops accompanying Clark.

The Indian villages on the Wabash River had been left unprotected when the Shawnee warriors went out to oppose Clark. During their absence, 800 militia under the command of Colonel Logan burned ten of their villages and destroyed an estimated 15,000 bushels of corn.78 Logan’s men also destroyed Louis Lorimier’s trading post on the Great Miami River, which was providing arms and ammunition to the Indians. The next year, Lorimier obtained a Spanish land grant and moved west to Cape Girardeau on the Mississippi with a group of Shawnee and Delaware Indians.79 (Lorimier’s nephew was George Drouillard, who accompanied Lewis and William Clark on their expedition to the Pacific a few years later.)

Clark established a garrison of 140 men at Vincennes to protect the town. Because of low water on the Wabash, they were unable to receive food, clothing and other supplies. Clark seized $20,000 worth of goods and a boat belonging to three Spanish merchants who had come to Vincennes to trade. The merchants lacked the necessary trading permits from their own government; and American boats and goods were being seized by Spanish officials at Natchez. Clark called a court martial of his officers who decided the property of the merchants could be confiscated under military law.80 This action by Clark was later used against him by Wilkinson in a wildly inflated charge of wanting to start a war with Spain.

Wilkinson saw George Rogers Clark as his rival for power when he arrived in Kentucky and devised an intricate plan to destroy his career. It counted on the fact that easterners,—unaware of the circumstances—would believe his lies about Clark’s seizure of the Spanish boat and supplies at Vincennes and Clark’s troubles with the militia.

Kentuckians held ten statehood conventions between 1784–1792, seeking independence from Virginia, free navigation on the Mississippi, and recognition as a state. Wilkinson played a leading role in the conventions, shaping policy and creating controversy.

He also bought land north of the Kentucky River and established the town of Frankfort in 1786, naming streets for himself and his friends. His wife Ann, however, after a short stay in Frankfort, decided they would move back to Lexington. In 1792, Frankfort became the capitol of the new state of Kentucky.

Before attending the statehood convention at Danville in December,1786, Wilkinson sent anonymous letters and forged documents to Edmund Randolph, the new governor of Virginia, and to members of the Confederation Congress. In the letters he spread lies about Clark being drunk and incompetent. They were ingeniously constructed so that the letters had to be shared among the recipients to learn the “full story.” In that way, the contents seemed more believable.81

This set the stage for the letters which followed. On December 20th, Wilkinson wrote to Francisco Cruzat, the Spanish Governor at St. Louis, apologizing for Clark seizing the boat and supplies at Vincennes and warning the Spanish governor that an attack on Natchez by “desperate adventurers” would take place in the spring of 1787.82

He wrote two letters on the 22nd to Virginia Governor Randolph. The first letter, skillfully written, was signed by Wilkinson and endorsed with the signatures of high level friends attending the convention. It referred to “testimonials,” which were copies of documents enclosed with the letter. His friends saw one set of “testimonials,” but—before sending the letter—Wilkinson substituted another set of forged documents purporting to show that Clark was assembling a great army to invade Louisiana and seize it from the Spanish. The second letter, signed only by his friends, asked that Wilkinson be appointed Indian Commissioner in place of Clark.

This trickery was discovered by historians Temple Bodley and Lyman Draper, and an analysis of his byzantine methods was published in a lengthy appendix to Bodley’s Life of George Rogers Clark in 1926.83 Bodley was a Kentucky historian and descendant of the Clark family.

Wilkinson succeeded in his plan: Governor Randolph condemned Clark’s actions at Vincennes and appointed Wilkinson as Indian Commissioner. However, the attorney general refused to indict Clark on technical grounds, which resulted in Clark not being able to clear himself in court, and Wilkinson’s deceptions remained undiscovered.

Wilkinson was to employ these tactics over and over again. The consummate bureaucrat, he understood the value of a “paper trail” and created and destroyed documents to suit his purposes. In an era when letters took weeks to deliver, it was easy for him to remain undiscovered. Everything was written by hand and copies were routinely made by others. Wilkinson was ingenious in constructing complicated chains of false evidence—but he was not infallible, once the documents are examined carefully. In 1809–1811, he used the same methods to create a false trail of evidence concerning the death of Meriwether Lewis.

The Cabildo is now a museum located on Jackson Square in New Orleans. It was once the seat of Spanish government. This building replaced an earlier building which was destroyed in the Great Fire of 1788. (photo by Kira Gale)

Wilkinson boldly set out for New Orleans in June, 1787 to arrange a contract for himself with the Spanish government to be given the exclusive right to bring Kentucky goods down the Mississippi to New Orleans. Spain had closed navigation on the Mississippi River to Americans at the end of the Revolutionary War.

Rivers were the interstate highways of the time period. There were no modern roads. Economic development depended on the ability to ship bulky goods by water instead of hauling them across the Appalachian Mountains.

New Orleans was the hot spot at the mouth of the Mississippi River on the Gulf Coast. Whoever controlled the city controlled the region. The Spanish government had acquired New Orleans at the end of the Seven Years War. It was a French city; its 5,000 residents were French speaking creoles, African slaves, and a free population of mixed bloods. It was the most cosmopolitan city on the continent.

Wilkinson paved the way for his adventure when he wrote to Cruzat, the Spanish Governor of St Louis, in December. His letter, warning about the attack on Natchez—which didn’t happen because it was imaginary—, made his name known to Spanish officials and they allowed him to travel down the Mississippi without stopping him.

Don Estavan Miró, Governor of Louisiana and West Florida.

(Wikimedia Commons)

Wilkinson arrived in New Orleans on July 2nd with flatboats of flour, butter, bacon and tobacco. He met with Don Estevan Miro, the Governor of Louisiana and West Florida, and told him Kentuckians were concerned the United States would cede the right of free navigation on the Mississippi to Spain for a period of twenty years, and because of that they were considering declaring their independence—and they were also talking about invading Louisiana by joining a British military expedition that would come down from Canada.

By these means, he persuaded Miro that the best policy would be to allow westerners to ship their goods to market through New Orleans and to grant Wilkinson the exclusive right to the shipping business. In return, he would encourage Americans to settle in Louisiana and become Spanish citizens, and Kentuckians to become independent. Miro bought the arguments, although he wrote the next year:

I am aware that it is possible that it is his intention to enrich himself by means of inflating us with hopes and advantages, knowing that they will be in vain.84

On August 22nd, 1787 Wilkinson signed an oath of allegiance to the Spanish monarchy, becoming Spanish agent #13, and then presented a lengthy memorial (report) to Miro on the subject of western dissatisfaction with their federal government. He argued Spain should continue to deny free navigation rights on the Mississippi to westerners, because it would induce them to form an alliance with Spain; and that the Spanish government should offer financial benefits to men of real influence—in other words, to Wilkinson and his friends. He later wrote:

… nor will it be denied, when my enemies are forgotten, that the projects for which I am now charged with traitorous designs, had a direct tendency to accelerate, the annexation of Louisiana to the United States…. I have ample and undeniable testimony to show that I omitted on no occasion, to employ my ascendancy over the officers of Spanish Louisiana, to render them subservient to the interest, and accommodation of the United States.85

In his report to Miro Wilkinson requested permission to bring fifty or sixty thousands dollars worth of Kentucky goods annually to New Orleans, duty-free. In return he would keep the Spanish government constantly informed about all matters concerning them. He was relying on their discretion to keep this matter entirely secret and—

“to bury these communications in eternal oblivion.”86

Calling himself “a good Spaniard,” Wilkinson wrote to the Spanish diplomat Don Diego Gardoqui on January 1, 1789:

It is not necessary to suggest to a gentleman of your knowledge and experience that the human race, in all parts of the world, is governed by its own interest, although variously modified. Some men are sordid, some vain, others ambitious. To detect the predominant passion, to lay hold of it, and to derive advantages from it, is the most profound part of the political sciences. 87

Wilkinson very skillfully played both ends against the middle—expansionist, intriguing, Americans on one end, foreign powers on the other end, and the future of the United States in the middle.

Wilkinson, after visiting the east coast, returned to Kentucky as a hero in February, 1788. He advertised as a wholesaler for products to sell at New Orleans and sent out buying agents. It was the first time that there was a market and cash payment for produce, and it brought prosperity to the back country. No one had ever managed to distribute so many silver dollars before. Tobacco was the main product brought to market, and it was potentially very profitable. Miro—who had been bribed by Wilkinson—said that if the business had been better conducted, or had better luck, he would have profited greatly.88

The opening of trade with New Orleans brought enormous benefits to farmers in Kentucky. It also hastened the admission of Kentucky to the union as it demonstrated the commercial potential of the region. It gave Kentuckians a chance to determine their own future, regardless of the wishes of easterners who opposed free navigation on the Mississippi River as injurious to their own trade.

At statehood conventions, Wilkinson advocated that Kentucky first become independent, and then seek admission to the United States. It was how he accelerated the admission of Kentucky to statehood. If Kentucky became independent, any one of the three foreign countries competing for control of the Mississippi Valley—Spain, Britain or France—could take Kentucky over, or form an alliance with it. It was just the push that was needed, and Kentucky became the 15th state in 1792.

George Rogers Clark knew that he had been used in this affair. He wrote:

The real motive of my accusers [in Kentucky] was that wishing to trade with New Orleans, they thought that by pretending to take the side of the Spanish vassals, they might hope to be favored in their projected commerce.

A few years later, George Roger’s younger brother, William Clark, became a supporter of Wilkinson in the frontier army—obviously unaware of the role Wilkinson had played in destroying his brother’s reputation.

In 1787, George Rogers Clark was asked by the governor to supply an account of his expenses in capturing Kaskaskia and Vincennes in 1778–1779. Clark had sent more than 20,000 expense vouchers to the state auditor in 1781. After Benedict Arnold burned the capitol at Richmond, Clark had supplied (as best he could) a duplicate set in 1783. Now he was being asked again. He said it was impossible unless the duplicates were returned to him. The original vouchers were eventually found in a storeroom in the state auditor’s office in 1913, and revealed both his careful accounting and that his ability to reconstruct them a second time was remarkable.89

In 1789 a British agent, Colonel John Connolly, came to the Falls of the Ohio from Detroit with an offer from Lord Dorchester, the Governor-General of Canada, to provide pay, clothing and equipment for 10,000 men if they would join with the British army in an invasion of Louisiana. Wilkinson relayed the news to Governor Miro in New Orleans and told him that he had sent a reputed assassin after Connolly, and that Connolly had fled the territory with an armed escort—also provided by Wilkinson. He earned the gratitude of both Spain and Britain with this maneuver.90

Wilkinson was promised he would receive payments from Miro for “secret and indirect agencies” in 1789. While he was in New Orleans he told Miro that General Washington had spies watching him during his visit. He wrote in code to Spanish officials, using an English pocket dictionary as the key, and they wrote back using the same code.

His finances were in terrible shape—business expenses, boat accidents and the suicide of a partner had resulted in massive debt rather than profit. Wilkinson asked for a loan from Miro. 91 On December 26, 1789, 7,000 silver dollars arrived in Frankfort in heavy leather saddle bags carried by two mules. Each silver dollar weighed one ounce; 2,000 dollars weighed 125 pounds. Wilkinson boasted that his young assistant, Philip Nolan, could carry a bag with one hand.92

Silver dollar or peso, depicting Charles III of Spain, 1776. (Wikimedia Commons)

The coins, minted in Mexico, were international currency. Millions of silver dollars were stored at the fortress at Vera Cruz and shipped through the Gulf of Mexico to world markets. Spanish Texas guarded the silver mines of the Sierra Madre Mountains. Spanish Government policy dictated that Texas serve as a barrier state. It was sparsely settled and commercially undeveloped in order to protect the silver mines.

The Spanish monarchy failed to become a modern state and to develop other commercial enterprises because it controlled so much silver and gold in the Americas. In the age of revolution, its colonial empire was ripe for a takeover, and everyone knew it. That is the real reason why Spanish-owned New Orleans and the Gulf Coast were such sought after prizes—the region not only would provide access to international shipping, but it could also become the site of a new country incorporating the silver mines of Mexico.

As Americans tried to force their way into new lands, Spanish authorities had to perform a delicate juggling act in the two Floridas, New Orleans, Louisiana and Texas to avoid war and hold onto their lands. The United States couldn’t provide protection and services on the frontier, so Americans were told to wait—but westerners hated the Spanish dons, who supplied arms and ammunitions to the Indians, and they didn’t think much of the federal government.

Thomas Jefferson wrote from Paris on January 25, 1786:

I fear … that the people of Kentucke think of separating, not only from Virginia (in which they are right) but also from the confederacy. I own I should think this a calamitous event, and such as one as every good citizen on both sides should set himself against, our present federal limits are not too large for good government, nor the increase of votes in Congress produce any ill effect. On the contrary it will drown the little divisions at present existing there. our confederacy must be viewed as the nest from which all America North & South is to be peopled. we should take care to not to think it for the interest of that great continent to people it too soon on the Spaniards. these countries cannot be in better hands. my fear is that are too feeble to hold them till our population can be sufficiently advanced to gain it from them piece by piece. the navigation of the Mississippi we must have. this is all we are yet ready to receive. 93

Wilkinson soon faced competition from rivals in the Mississippi River trade. His monopoly was short lived. He continued in the trade for two more years with disastrous results. He had to sell his lands, carriages, horses and oxen to satisfy his creditors in 1791.

In the summer of 1790, General Josiah Harmar led a campaign against the Miami Indians on the Ohio frontier with frontier militia. It was a failure. The next year Wilkinson served as second in command under General Charles Scott in raids against the Indians, and then led a raid under his own command. Young William Clark served under Wilkinson.

Wilkinson wasn’t present at General Arthur St. Clair’s Defeat on November 4, 1791. More than a thousand Shawnee, Miami, Delaware and Potawatomi warriors won the battle on the Wabash River under the leadership of Miami Chief Little Turtle and Shawnee Chief Blue Jacket. It was the worst defeat of the America military in the Northwest Indian Wars, with more than 600 soldiers killed and 300 wounded out of a total force of about 1,400. Indian casualties were about 61, with 21 dead.94

On November 5th, 1791, Wilkinson was sworn in as Lieutenant Colonel Commandant of the 2nd Infantry in the Legion of the United States. His connection with Spanish officials may have been a factor in his appointment. James Ripley Jacobs, the leading biographer of Wilkinson, says he probably became “sort of a federal stool pigeon.”95

George Washington appears to have trusted Wilkinson because of his actions in exposing the Conway Cabal during the Revolutionary War. When Wilkinson informed Miro that General Washington had spies watching him during his second visit to New Orleans in 1789, he may have been explaining why he was seen in the company of American secret agents. Washington later wrote to Alexander Hamilton that he had appointed Wilkinson because he felt it would:

… feed his ambition, soothe his vanity and by arresting discontent produce a good effect.

But perhaps that wasn’t the whole story.

Wilkinson said that he had returned to military service, because he had been:

… disgusted by disappointment and misfortunes. My views in entering the Military Line are Bread & Fame—uncertain of either, I shall deserve both.96

On February 1, 1792, the new Spanish governor, Francisco de Carondelet, wrote to Wilkinson that he was finally going to receive the $2,000 annual pension he had been promised, and it would be retroactive to January 1,1789. He received the $4,000 that summer, supposedly as payments for tobacco sales. The Spanish government felt he was now a good investment.

The United States republic and Spanish officials in the two Floridas, Louisiana and Mexico shared a common goal—to maintain the status quo as long as possible. As Jefferson said, “these countries could not be in better hands.” His only worry was whether Spain was “too feeble” to hold onto them. The real concern was whether Britain or France might manage to establish a new country in the west before the United States was ready to “receive” the territories from Spain.

The American Revolution had spread to France in 1789, and the Napoleonic Wars would begin in 1803. The United States adopted a neutral policy during the European conflicts. It was too weak to do anything else. The wars actually protected the new country, as Britain and France fought each other from 1793–1815, and had limited resources to devote to regaining their old territories in America.

Seen in this light, Wilkinson’s role as a double agent can be understood. The strategies he suggested to the Spanish government were obvious. He enticed them with stories of Kentucky’s independence, but it led to Kentucky’s statehood. His biggest accomplishment was in opening the Mississippi River to Kentucky trade, which eliminated the primary reason why westerners would want to enter into a union with Spain.

Since it was widely rumored that Wilkinson was a Spanish agent, and he was always considered to be an intriguer, he found it easy to infiltrate American groups plotting to establish new countries with either British or French military support, or with disloyal Spanish officials. He sabotaged their plots, and they never seemed to realize he was behind their failures. He thwarted efforts by rivals to establish new colonies in Spanish territory. And he kept the lines of communication open with Spanish officials. He was busy.

Baron Joseph de Pontalba of New Orleans, who later moved to France, advised Napoleon to employ Wilkinson in his secret service. He wrote:

Four times, from 1786 to 1792, preparations were made in Kentucky and Cumberland to attack Louisiana, and every time this same individual caused them to fail through his influence over his countrymen. I make these facts known to show that France must not neglect to enlist this individual in her service. 97

In building his first relationship with Spanish officials and gaining his own career advancement, Wilkinson ruined George Rogers Clark’s army career and took his place as Indian Com missioner. But he only attempted “character assassination” with Clark. He will have another encounter with Clark in the next few years.

The assassinations and attempted assassinations associated with Wilkinson will be discussed in the next chapter.

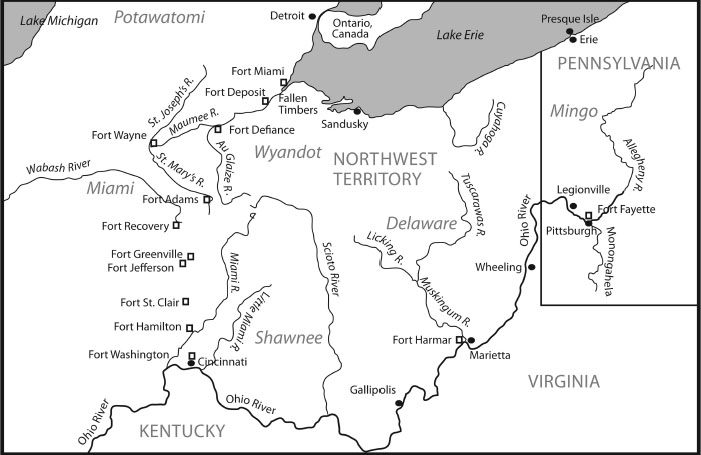

Map of the Legion of the United States, Ohio Valley1792–1796.