Major General Anthony Wayne arrived in Pittsburgh to take command of the American army in June, 1792. After St. Clair’s Defeat, congress expanded and reorganized the army, and gave it a new name, the Legion of the United States. Four sub-legions were created, and Wilkinson was appointed one of the commanders.

“Mad Anthony Wayne”—a nickname gained for his bold leadership during the Revolutionary War—was a seasoned commander, who knew the value of strict discipline. He began turning new recruits into trained soldiers who would avenge the American defeats in the Indian Wars. The legion remained in Pittsburgh until November, and then moved to a new headquarters, 22 miles south of Pittsburgh on the Ohio River. Legionville would become the first basic training camp of the United States military.

At the same time, 13,000 nationalized state militia troops were arriving in western Pennsylvania to put an end to the Whiskey Rebellion. The government’s show of force was meant to intimidate more than Pennsylvania rebels. The state militias got a chance to see the Ohio River Valley. The newly created Northwest Territory lay across the river—bounded by the Ohio River on the east and south, the Great Lakes on the north, and the Mississippi River on the west—the territory which would become open for settlement at the close of the Indian Wars.

Meriwether Lewis was among those who decided to stay on in the west after his militia duties were finished. He enlisted in the Legion of the United States in 1795. But before we continue with his story, the events of the next three years need to be told.

James Wilkinson was made a brigadier-general in March, 1792. He commanded 200 soldiers at Fort Washington in Cincinnati, the largest military post in Northwest Territory. The fort’s roof and fences were painted red, and gardens of vegetables and flowers were planted nearby. Cincinnati consisted of about 900 residents, taverns, vice, and a surplus of merchants.98

Fort Washington. (Wikimedia Commons)

The Wilkinsons were now the parents of three boys, ages 12, 9 and 7. Ann left in the summer to bring the two older boys to Philadelphia to attend school, and to visit relatives. A two story frame house was built for General Wilkinson at Fort Hamilton, where he could enjoy fishing and hunting.

President Washington was determined to give peace talks with the Indians of the Northwest a chance to succeed. He sent peace commissioners throughout the region in 1792, but to no one’s surprise, they were unsuccessful. The Indians, victorious in battle, were in no mood to compromise.

When General Rufus Putnam met with the Illinois and Wabash tribes at Vincennes in September, the chiefs declared the north side of the Ohio River was Indian territory and they had signed no treaties. They wanted American traders—but no American settlements and no forts. They told General Putnam:

… that wherever the Virginians go, they cause trouble in some way.99

Under British rule, it had been Indian territory since the end of the French and Indian Wars in 1763. Despite the terms of the Treaty of Paris at the end of the Revolutionary War, the British still had forts in Northwest Territory and continued to supply arms and ammunition to the Indians.

Wilkinson chose two men to carry Washington’s message of peace under white flags of truce to the Wyandot and Miami Indians. The General wrote to Colonel John Armstrong, commander of Fort Hamilton on May 24th, 1792, predicting their deaths—

Hardin and Trueman left us day before yesterday, the former for Sandusky, the latter for the Maumee, I think it is equivocal what may be the event, but do not expect they will return.100

John Hardin, a Kentucky militia general, and Major Alexander Trueman of the First Infantry Regiment of the United States were highly regarded military leaders. Wilkinson had written to Hardin urging him to undertake the mission, saying:

… you are better qualified for it than any man of my acquaintance, and because I think it will lead to something of advantage to you.101

Hardin had served under Wilkinson at the Battle of Saratoga in 1777. Often sent out on dangerous reconnaissance missions, Hardin was one of Daniel Morgan’s best Virginia sharpshooters. An early biographer of Wilkinson says tradition had come down through the years that it was Hardin who actually discovered Burgoyne’s army was advancing towards Saratoga, rather than Wilkinson who took credit for it. The biographer, Royal Ornan Shreve, points to a suspicious comment made by Wilkinson in his Memoirs:

… where I found Hardin who had made no discovery …

and Wilkinson’s fulsome praise for Hardin in a footnote—

* Afterwards General Hardin of Kentucky, an excellent officer and most valuable citizen, who having encountered a thousand dangers in the service of his country, was treacherously murdered in 1791 [sic] by a party of Indians, as he approached Sandusky with a flag of truce and a talk from General Washington. A braver soldier never lived—a better man has rarely died.102

Humphrey Marshall, a contemporary, and an enemy of Wilkinson’s, wrote in his History of Kentucky, published in 1812:

Whether the general, was really the friend of Hardin, and candid in his expressions of a desire to serve him—and thought such employment conducive to that end: or viewing him as a rival in fame, who might afterwards be in his way, if not seasonably put out of it … as by some was strongly suspected; there is no means possessed of knowing. Certain it is that Wilkinson persuaded, and pressed Hardin, to the undertaking—as he did Major Trueman, an officer of great merit, under his command; and with whom he was known to be at variance, to undertake a like commission….They were both called and they were both cut off.

Hardin and Trueman and their companions were killed by Indians who appeared friendly and who volunteered to camp with them. In each case, the Indians suddenly murdered them without warning. Marshall said that:

… when the news was carried to the [Indian] town, “that a white man with a peace talk had been killed at the camp,” that it excited great ferment; and that the murderers were much censured.103

Hardin and Trueman would never have camped with anyone they suspected of intending to harm them. These were planned and premeditated assassinations. Their deaths are also the first time that Wilkinson is accused of assassinations.

The author of these charges, Humphrey Marshall, believed he was also the target of an assassination attempt by Wilkinson. Marshall was a Federalist, a U. S. senator, and a cousin of John Marshall, Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. Humphrey Marshall was an outspoken, relentless critic of James Wilkinson and the “Spanish Conspiracy” in Kentucky politics. In 1788, Marshall survived an assassination attempt by a man he called:

… an ignorant catspaw of craftier but more prudent men.

Members of the Spanish Conspiracy included Wilkinson and his friends Harry Innes, a federal judge, John Brown, a U. S. senator, and Benjamin Sebastian, who received a pension from Spain.104

Fort Greene Ville (www.shelbycountyhistory.org)

General Wayne moved about 1,500 troops from Legionville to a camp one mile south of Fort Washington at Cincinnati in May, 1792. General St. Clair had built Forts Washington, Hamilton and Jefferson. Wayne would leave nothing to chance and build seven more forts before going into battle. The chain of forts would ensure that army horses would have hay, and the men would have provisions and protection as they marched north.

Peace negotiations with the Indians ended in failure in September, 1793 and the army was now authorized to prepare for war. In November, Wayne began building a fort six miles north of Fort Jefferson, capable of serving as a winter camp for 2,000 soldiers. He named the post Fort Greene Ville after his friend, Nathaniel Greene, a Revolutionary War general. Fort Greene Ville was a small city, and both Wayne and Wilkinson had houses built there. The fort, was one of the largest wooden forts ever built: 900 feet by 1,800 feet enclosing 55 acres within its walls.105

The reconstructed Fort Recovery is now the site of an Ohio State Museum in Fort Recovery, Ohio.

Fort Recovery was built on the site of St. Clair’s battlefield near the Wabash River. Wayne arrived there on Christmas Eve with a special detachment. They found 500 tomahawked skulls on the battlefield, and buried the remains of their comrades in a common grave. They also began to locate the cannons from St. Clair’s army that had been hidden under logs and buried by the Indians after the battle in 1791.106

Fort Adams was built in the summer of 1794 near St. Mary’s River to control the river traffic. Fort Defiance was built in August on a high bank overlooking the confluence of the Maumee and Auglaize Rivers. It was reinforced to defend against artillery attacks by the regular British troops stationed at Fort Miamis. Fort Deposit was just what it name implies: a small fort where their excess baggage was deposited before the Battle of Fallen Timbers.

Throughout this all, Wayne had to deal with the disloyalty and troublemaking mischief of General Wilkinson, his second in command. Wilkinson went over his head, writing directly to Secretary of War Henry Knox, criticizing Wayne’s leadership. However, Knox, a friend of Wayne’s, promised to protect Wayne against Wilkinson’s misrepresentations as long as he was in office.107 The officers of the legion split into two factions, with the Wilkinson faction resenting Wayne’s disciplinary measures, his abrupt manner, his restrictions on alcohol use, and the slow progress towards war. Wilkinson was doing all he could to en courage discord, hoping to take over Wayne’s command. His easy manner and skill at manipulating people won him many friends.

Wayne was actually waging war by building forts and training his soldiers. It was slow and methodical, and in the end, successful. Additional forts signalled the absolute determination of the United States to take control of the Northwest. The British rebuilt an old, abandoned fort, Fort Miamis, on what was now American soil, claiming it was a “dependency” of Fort Detroit. Fort Miamis was located two miles from Colonel Alexander McKee’s trading post, which was supplying arms and ammunition to the Indians.108

The crucial question was—would war break out between the United States and Great Britain over Northwest Territory, or would it remain a war fought between the Indians and Americans? The British promised the Indians that Great Britain would soon be going to war against America.109

In June, the Indian confederacy began assembling at the Auglaize River for an attack on Fort Recovery at St. Clair’s old battlefield. 1,250–1,500 warriors from all the northwestern tribes, including the Lake and Canadian Indians, participated.110 General Wayne wrote to Secretary of War Henry Knox that the Chickasaw and Choctaw Indian scouts he employed as spies had told him that:

… there were a considerable Number of armed white men in the rear, who they frequently heard talking in our language & encouraging the Savages to perservere in the assault, that their faces were Generally blacked except three British Officers who were dressed in scarlet & appeared to be men of great distinction, from being surrounded by a large party of White men & Indians who were very attentive to them, these kept a distance in the rear of those who were engaged.111

On June 30th the Indians attacked a supply convoy leaving Fort Recovery. Because Wayne had insisted the cannons which the Indians had hidden after St. Clair’s defeat be located, the Indians searched in vain for them. They had come to the fort with ammunition to use in the cannons. Undoubtedly the British offi cers planned to help with the artillery—but instead the cannons were used to defend the fort.112 The battle at Fort Recovery was a significant turning point in the Indian Wars, because the Indians—who had been so confident of another victory—retreated after two days.

Lieutenant William Clark, who had fought under Wilkinson in two earlier campaigns in 1790, was strongly attached to the general. He had no idea that Wilkinson had destroyed his older brother’s career.

Two years earlier, in June, 1792, the 22 year old lieutenant had been sent on a special mission to the Chickasaw Bluffs in Tennessee. Clark commanded a unit of 24 men who travelled down the Mississippi and managed to pass successfully by the Spanish fort at Natchez. They brought trade goods, corn, and arms to the Chickasaw, and returned with a Chickasaw chief and 8 warriors who would act as scouts and spies for the legion. Clark received high praise for this mission: General Wayne wrote to Secretary Henry Knox—

This young Gentleman has executed his orders … with a promptitude & address which does him honor & which merits my highest approbation.”113

Despite this high praise, Clark continued to remain a member of Wilkinson’s faction in the army.

After almost two years of preparation, some 2,000 members of the legion were joined by 1,500 mounted Kentucky volunteers and the army set off to fight the Indians in late July, 1794. This would mark the beginning of the end of the Indian Wars in the Ohio Valley, until they were resumed during the War of 1812.

Clark began keeping a journal when they left Fort Greene Ville on July 28th, apparently intending to document the errors of General Wayne’s command, perhaps in anticipation of a later congressional investigation or military court martial. Wilkinson most likely had asked Clark to keep a journal.

On August 3rd, Clark recorded what appears to have been attempt on General Wayne’s life. Wayne called Wilkinson “that vile assassin” in a letter to Secretary of War Knox a few months later. Whether Wayne was referring to this incident or something else is not known, but it seems the most likely reason he would have accused Wilkinson of being an assassin.114

The incident happened on the afternoon of August 3rd. It was very hot and General Wayne and his aide de camp, Captain Henry DeButts, were napping in a marquee tent. Outside, the troops were chopping down big trees to use in constructing the new fort near the St Mary’s River, to be named Fort Adams. William Clark’s journals records what happened next:

—This day fortune in one of her unaccountable pranks, (I say unaccountable for [no] one will pretend to know why She Should at this juncture, at this critical moment, but an illtimed, prank perturb the minds of Hundreds & create for a moment in theire Breast such unthought of Sensations & open So large a field for Speculation) had nearly deprived the Legion of its Leader, had nearly deprived ‘Certain individuals of theire A. W. [Anthony Wayne] & Particular persons of their consequence—the downfall of Some would have been equale to the tumble our Chief occasion’d by the fall of a large Beech Tree, which fell about his Marquee [tent], had fortune directed its course a few feet more to the right or left—but (Fav’d Fort’n) His Excellency’cy was more Sceared then hurt. All ended well, though there was considerable concorse—115

An anonymous journal writer of the campaign wrote:

About 3 O’Clk this afternoon a tree fell upon the tent of the C in C and that of his A D C. Capt. De Butts, both being in their beds—the escape of each was miraculous, the Bed of the aid being crushed to pieces and the C in C escaped, by about six inches being mashed to Death by the Body of the tree—he was dragged out of the tent, having received a severe stroke on his left leg & ankle—his pulse was gone.—but by the application of a few volatile drops he was soon restored to good spirits and comfort.116

Wayne wrote to his son Isaac Wayne that he was:

…almost deprived of life… by the falling of a tree … & was only preserved by an old trunk near where I was struck down—which supported the body of the tree from crushing me to attoms.117

Beech trees can reach a height of a hundred feet or more. Wayne’s life was saved because a tree trunk near the tent broke the impact of the falling tree. The falling tree wasn’t chopped down. It had been set on fire by a fire kindled near its base—which made it almost impossible to prove it was deliberate.

After that, Wayne ordered all of his off duty officers to report to duty and help get the fort finished, because they were leaving the next day. The next morning General Wayne continued on with his army, despite being in severe pain. He already suffered from gout in his leg. From that time on, he had to be helped onto his horse.118

Wayne surprised his own officers, the Indians, and the British, by taking an unexpected route of attack. He had intentionally misled them. The attack was expected on Kekionga, a group of Miami Indian villages at the junction of the Maumee, St Joseph’s and St Mary’s Rivers. Instead he headed north along the Auglaize River to its junction with the Maumee, where they stopped for eight days and built Fort Defiance on the site of a deserted Shawnee village of log cabins and huts. Fort Defiance was in between the Miami Indian villages and Fort Miamis on the Maumee River.119

An army deserter, Robert Newman, warned the village that the army was coming and its residents fled the day before the troops arrived. It is thought that Newman was acting as an agent of Wayne’s in alerting the village.120 The general was out to fight a war to end the Indian Wars, not to harm those who were left behind in the villages. A lieutenant wrote about arriving at the Auglaize village:

This place far exceeds in beauty any in the western country… Here are vegetables of every kind in abundance, and we have marched four or five miles in cornfields down the Oglaize, and there is not less than one thousand acres of corn round the town.

Nearby villages were the homes of the Shawnee leader Blue Jacket and Miami Chief Little Turtle, who had been leaders of the confederation that defeated St. Clair’s army in 1791.121

Lieutenant Clark wrote that when the army was within 12 or 14 miles of the Indian settlements, their spies returned with the news that the settlements were being evacuated:

everybody was flushed with the Idea of Supprising them in the moment of providing for theire Wives & Children the Scheeme was perposed & certain Suckcess insued if attempted—General Wilkinson Suggested the plan to the Comdr in Chief but it was not his plan, nor perhaps his wish to Embrace So probable a means for Ending the War by compelling them to peace—this was not the first occasion or oppertunity, which itself to our observent Genl. for Some grand stroke of Enterprise, but the Comdr in Chief rejected all & every one of his plans—122

A Shawnee captured by spies told Wayne:

the Indians talked on stepping to one side and letting the army go on to the British or that if the British did not now come forward to assist them they would join the Americans.

Wayne sent the Shawnee captive back to the confederation on August 13th with a message urging that the hostile tribes meet with him and establish the preliminaries of a lasting peace with the United States which would—

…eventually and soon restore to you … your late grounds and possessions, and to preserve you and your distressed and hapless women and children from danger and famine during the present fall and ensuing winter. 123

The battle was about to begin. All the sick and the lame of the regular troops were left behind at Fort Defiance. About 70 Chickasaw and Choctaw warrior scouts refused to advance and stayed at the fort.124 The army left the fort on August 15th, and the next day a messenger brought the Shawnee’s answer—they wanted a 10 days halt to the army’s advance in order to consult with other nations. It was agreed they were stalling for time, and the army continued to advance.

The British had sent additional troops to Fort Miamis under a new commander. It was uncertain what role the British would play in the battle and whether the fort would be attacked by the Americans. Thousands of women and children were in refuge camps north of the fort.

On August 18th, Wayne built one last temporary fort to hold excess gear. The soldiers carried only a blanket and two days of rations into battle—traveling light was one of his key strategies. Fort Deposit was similar to what Wayne’s army built every day while on the march: grounds marked off for tents for the four sub-legions; the whole enclosed with a breastwork of logs; and smaller outposts beyond the breastworks for protection of the sentries. If necessary, it would serve as a retreat.125

Lieutenant William Henry Harrison, one of Wayne’s aides, wrote that Wayne’s strategy and tactics:

… united with the apparently opposite qualities of compactness and flexibility, and a facility of expansion under any circumstances, and in any situation, which rendered utterly abortive the peculiar tact of the Indians in assailing the flanks of their adversaries. 126

The Battle of Fallen Timbers took place on August 20th. The battlefield was covered with trees struck down by a tornado. It was just five miles south of Fort Miamis, giving the British every opportunity to participate in the battle—although it was not really a battle but a skirmish which lasted for 60–85 minutes.127 The total casualties were 27 killed and 87 wounded of the estimated 1,000 American troops who participated. An estimated 1,300 warriors were in the area, but about 400 Indians and 60 Cana dian militia were active in the battle.128 The Indian casualties are unknown; however, 30–40 Indians were found dead who had not been carried away by their comrades.129 The Indian tribes who participated were Wyandotte, Mingo, Delaware, Shawnee, Potawatomi, Ottawa, Chippewa, Miami and Mohawk.130 A Frenchman who fought on the Indian side explained their defeat by saying that the soldiers—

would give them no time to reload their pieces but kept them constantly on the run.131

The gates of the British fort were kept tightly shut, not allowing the Indians or Canadian militia to enter the fort as they retreated. The Indians never forgot this and it did more to ensure peace between the Indians and Americans than anything else. The British refusal to help—after all their promises—broke the confederacy. Wayne and the fort commander wrote belligerent letters back and forth, and Wayne thought about laying siege to the fort, but he didn’t have enough provisions or artillery for it, and the army went back to Fort Defiance.132

After the victory, Wilkinson renewed his attacks on Wayne. Wilkinson commanded the right wing of the troops during the battle. William Clark served under Colonel John Hamtramck, who commanded the left wing. Wilkinson wrote to his friend Judge Harry Innes in November with this opinion of Wayne’s campaign:

The whole operation presents to us a tissue of improvidence, disarray, precipitancy, Error & Ignorance, of thoughtless termerity, unseasonable Cautions, and shameful omissions, which I may safely pronounce, was never before presented to the view of mankind; yet under the favor of fortune, and the paucity & injudicious Conduct of the enemy, we have prospered beyond calculation, and the wreath is prepared for the brow of a Blockhead.133

Before the battle, Wilkinson had asked for a military court of inquiry covering his own conduct and made five charges against Wayne in letters he sent to Secretary of War Knox in June and July. In December he received a reply from Knox who had forwarded Wilkinson’s charges to Wayne. Knox asked Wilkinson to be more specific. Wayne wrote to a friend that if he was guilty of Wilkinson’s charges, he “ought to be hanged.” In January, 1795 Wilkinson backed down publicly, yet continued to write to Knox. Wayne could not afford to get involved in a fight with a subordinate while negotiating peace treaties with the tribes, and so he ignored Wilkinson’s charges until the treaties were accomplished.134

Wilkinson continued to agitate—the army would soon be reduced and either Major General Wayne’s position or Brigadier General Wilkinson’s position would be abolished. He had more to worry about than his job, however—Wayne was charging Wilkinson with being a British agent. In December, 1794 Robert Newman had returned to Fort Greene Ville, and said he had direct proof that Wilkinson was intriguing with Canadians for a union of Kentucky with Canada.

Historians disagree as to whether Newman was working for Wilkinson or Wayne. According to Robert Newman’s brother, General Wayne had told Newman to:

become associated with such persons as might be suspected of being in favor of the Indians or British.

Newman was in fact working for Wayne, when he appeared to be working for Wilkinson. The story was that Wilkinson gave Newman a letter to carry to Alexander McKee, the trader at Fort Miamis, and Wayne read the letter. But Wayne must have substituted another letter before it was given to McKee, because both McKee and the Lieutenant Governor of Upper Canada, John Simcoe, suspected Newman was part of a “sinister plot.” Simcoe wrote that the letter contradicted information they had already received from Wilkinson—proving they were in correspondence with Wilkinson. After Newman returned to Fort Greene Ville and was interviewed by Wayne, Newman came into a possession of a large amount of money in brand new army bills, which he used to pay a debt he owed.135

Anthony Wayne (1745–1796), pastel drawing from life by James Sharples, Sr., 1796.(Wikimedia Commons and NPS Museum Collections, Independence National Historical Park, IN 11922)

James Wilkinson (1757–1825) oil painting by Charles Willson Peale, 1797. (Wikimedia Commons and Independence National Historical Park, IN 14166)

General Wayne, of course, believed that Wilkinson was genuinely working with the British. He had seen correspondence in which Wilkinson asked an army contractor to delay providing supplies to the army in 1793. The question is—was Wilkinson acting as a traitor, or as a double agent? The federal government must have believed he was acting as a double agent because they didn’t pursue the matter.

Wayne wrote privately to Secretary of War Henry Knox on January 29th, 1795 warning him of Wilkinson’s treachery. The letter which is torn in several parts (an early form of censorship) said:

I am much obliged by your [torn] it has been consistant [torn] my own honor, & the true of interest of my Country to accomodate with that vile assassin Wilkinson, I most certainly would have made an attempt in compliance with the President’s wishes But it is impossible—for I have a strong ground to believe, that this man is a principal agent, set up by the British & Demoncrats of Kentucky to dismember the Union.

N___n [Robert Newman] says that to the best of his knowledge & belief the letter to Colo McKee was in W___n’s [Wilkinson’s] hand writing & that it was put into his (N___ns) hand [torn] Indeed I have cause to beli [sic, believe] [torn] & tampering both by the British & Spaniards.136

Some “Demon-crats” in Kentucky—led by George Rogers Clark—had been actually engaging in a conspiracy to start a new country for France. Clark and his brother-in-law, Dr. James O’Fallon, wrote a letter to Edmond Genêt, the newly appointed French minister to America, volunteering to raise a force of 1,500 men to seize the Spanish posts on the Mississippi and New Orleans for France. The letter was waiting for Genêt when he arrived in Charleston, South Carolina on April 8, 1793.137

The King and Queen of France, Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette, were executed by guillotine in January, just before Genêt left the country. After their executions, the new French Republic declared war against England in February and against Spain in March. In August, it abolished slavery in its richest colony, Saint Domingue (Haiti).

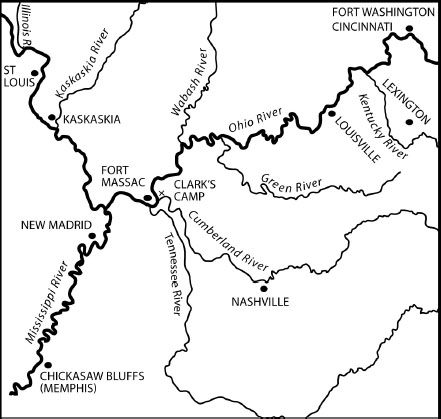

André Michaux and Edmund-Charles Genêt (Wikimedia Commons)

When Edmund Genêt arrived in Charleston, he commissioned four American ships to serve as French privateers, authorizing them to attack and capture British ships, and began making arrangements for 1,500 Georgia volunteers to seize Spanish East Florida.138 Citizen Genêt was greeted by large and enthusiastic crowds as he made his way from Charleston to Philadelphia, but on April 22nd, President Washington issued a Proclamation of Neutrality forbidding American citizens from aiding any of the nations at war with each other.

The French Republic planned to finance invasions of the Spanish Floridas, Canada and Louisiana by receiving an advance on money it was owed from loans France had made to America during the American Revolution. President Washington refused to release any money, saying the future of the French government was uncertain. It proved to be a wise move. In June the officials who had appointed Genêt were executed and the Reign of Terror began in which thousands were executed by the new Jacobin government.

André Michaux—a distinguished French botanist and explorer—was living in Charleston where he had established gar dens to study and collect American plants for the royal botanical gardens. A year earlier, in 1792, Michaux had applied to lead an expedition to the Pacific Ocean which was being organized by Thomas Jefferson and the American Philosophical Society. Meriwether Lewis also “warmly solicited” Jefferson for the chance to go to the Pacific with Michaux, but because he was 18 years old, he was turned down.139

Michaux was chosen, and Genêt also appointed Michaux a secret political agent for the French Republic. Michaux left Philadelphia in July, 1793, accompanied by two French artillery officers. Botanizing along the way, Michaux met with George Rogers Clark in Louisville on September 17th and gave him his commission as “Commander in Chief of the Independent and Revolutionary Army of the Mississippi.”140

Clark planned to live in France after he led the French Revolutionary Army. He was given blank commissions to recruit officers, and by January, 1794 it was said that over 1,000 men had joined the army. Clark published advertisements in western newspapers seeking volunteers for “the reduction of Spanish posts on the Mississippi.” He offered land grants of 1,000 acres at enrollment; 2,000 acres after one year of service; and 3,000 after two years. If they wanted, instead of land grants, enlisted men could receive one dollar a day pay. Officers would receive French army pay and share in “all lawful plunder.” Members of the army would need to expatriate themselves and become French citizens.

In March, 1794 French embassy officials in the United States ordered a halt to the filibuster plans and Genêt was recalled by his government. Facing certain execution, Genêt was granted political asylum and later married the daughter of Governor Clinton of New York. President Washington followed up with a proclamation on March 24th, warning American citizens not to participate in the French filibuster.141

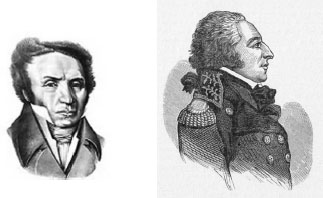

At the same time, Secretary of War Knox ordered General Wayne to “immediately” build a new fort on the site of the old French fort, Fort Massiac. Fort Massac (the American version of the name) was located on the north bank of the Ohio, eight miles downstream from its junction with the Tennessee River. On March 31st Knox sent “secret and confidential instructions” authorizing the fort commander to fire upon American citizens who were armed and equipped for war, after the commander had tried peaceful means of stopping them.142

Ohio and Mississippi Rivers, Fort Masaac.

The reconstructed Fort Massac is located in Metropolis, Illinois.

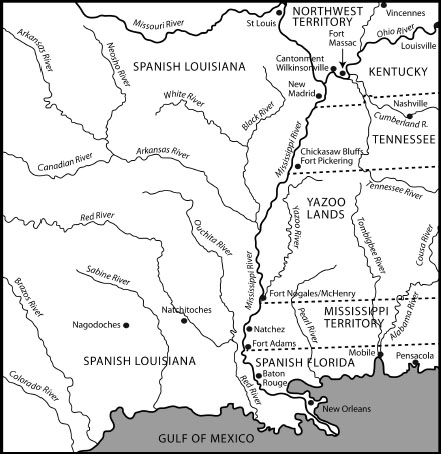

Clark had erected a fortified camp at the mouth of the Cumberland River and was in the process of building boats and securing supplies. He planned to seize New Madrid first, then St. Louis and Natchez, and take New Orleans with the assistance of army units being organized in the southeast. The Spanish took the matter seriously: their post at New Madrid was reinforced with additional troops and five galley ships, and a large group of Indians was assembled for its defense.143

After the collapse of the Genêt project, Clark, who had advanced money for it, was owed $4,680 by the French Republic. Clark was also owed money by the Virginia Assembly. He was personally liable for debts to merchants who had supplied his army during the 1778–79 invasion of Illinois Country, because he had signed notes on behalf of Virginia. The creditors came after Clark. Before making his offer to the French Republic, Clark applied to the Virginia legislature in November, 1792 for $20,500 in compensation. The assembly rejected his claim, saying he should have presented it earlier. It was an insulting reply, as his original expense receipts had been given to them in 1781 and his reconstructed receipts in 1783. The lack of gratitude embittered him and he wrote:

I have given to the United States half the territory they possess and for them to suffer me to remain in poverty in consequence of it, will not redound much to their honor later … I must look out further for my future bread.144

General Wilkinson, however, profited from this affair. It seems likely that Wilkinson may have used William Clark—who was a great admirer of Wilkinson at this time—as a source of information about his brother’s filibuster. George Rogers and James O’Fallon, their brother in law, first approached the French government in the winter of 1792–93. The 24 year old William may have revealed their plans for a French invasion army either to Wilkinson or to a fellow officer who informed the general.

It would explain why Wilkinson was colluding with army contractors in 1793 to delay the supplies and transportation needed for Wayne’s army to advance. General Wayne was eager to begin a war against the Indians in 1793, but unaccountable delays made it impossible.

George Rogers Clark didn’t receive his commission as a major general in the French army until September, 1793. The plans for a French army invasion became public knowledge in October. If Wilkinson had prior knowledge of it, he would have wanted to keep Wayne’s army in southern Ohio to prevent the invasion. Wilkinson was serving both the United States’ and the Spanish government’s interests, and making General Wayne look bad—accomplishing three things at once in his usual style. It is also likely that Alexander Hamilton, the Secretary of the Treasury, was interfering and arranging for problems with the contractors to keep the army in southern Ohio near the French Revolutionary Army.145

General Wilkinson billed the Spanish government for $12,000 on June 20, 1794. He said he had papers to prove he had spent $8,640 in breaking up Clark’s plot to invade Louisiana; and he deserved a pay increase to $4,000 annually for his secret services. He wrote he was employing an informer to learn about Clark’s plans, and $200,000 should be sent to him from Philadelphia to use as bribe money to win Kentuckians over to Spain. The general’s monthly army pay was $104, which didn’t begin to cover his expenses.

The new Governor of Louisiana, Baron de Carondelet, agreed to send $12,000 by Wilkinson’s two couriers, Henry Owens and Joseph Collins. Owens would set off first with $6,000 and Collins would follow. A Spanish vessel carried Owen and the 6,000 silver dollars from New Orleans to New Madrid where the dollars were transferred into three small barrels. At the mouth of the Ohio, Owen and the barrels were transferred to a pirogue manned by a Spanish crew of six oarsmen and a pilot. Soon afterwards, Owen was murdered and the crew fled with the money.

Three crew members were later arrested and taken to Lexington, Kentucky, where Judge Harry Innes—Wilkinson’s lawyer and his partner in the Spanish Conspiracy—interviewed them and sent them to General Wilkinson at Fort Washington, who attempted to send them back to the Spanish authorities at New Madrid. However, while en route to New Madrid, the Fort Massac commander arrested them and sent them back to Kentucky. When they were returned to Judge Innes to stand trial, he freed them for lack of evidence and the money was never recovered.146

Collins set out from New Orleans by sea in late August, but he spent much of the money on travel expenses and investing in land around Fort Pitt before he arrived in Ohio in April, 1795; Wilkinson reported to the Spanish that only $2,500 was left of the $6,334 that Collins had started out with. Wilkinson,—whatever his involvement was in destroying Clark’s French army conspiracy—had little to show for it.147

General Wayne negotiated the Treaty of Green Ville ending the Indian Wars in the Northwest, signed by 80 chiefs and agents on August 3rd, 1795. The grand council was attended by 1,130 Indians, representing the Wyandot, Shawnee, Delaware, Ottawa, Miami, Eel River Miami, Chippewa, Potawatomi, Wea, Kickapoo, Piankashaw and Kaskaskia tribes. As part of the treaty provisions, the tribes agreed to vacate the southern 2/3’s of Ohio, leaving it open for American settlement. The number of Americans on the Ohio frontier grew rapidly after that, from an estimated population of 5,000 in 1795 to 230,000 in 1810.148

Ensign Meriwether Lewis joined the 4th Sub-Legion in May, 1795. The records are fragmentary for both Lewis and William Clark during this time period, but it seems likely that Lewis and Clark first became friends during the summer of 1795. Their time together was brief, however, as Clark was gone most of the time during his final months in the legion.

Lewis served in a peacetime army, coming into the legion after the fighting had ended. Four years separated the two friends in age, but William Clark had acquired a wealth of experience in the last four years—fighting Indians in three separate campaigns, leading men, and traveling widely throughout the region. During this time, he also had the unenviable distinction of having a famous older brother who was organizing a French army to invade Louisiana.

Within a few months, the 21 year old Lewis got into a quarrel which might have ended his military career. He and another ensign called at a house where a Lieutenant Devin was attending a private party. Lewis asked to speak with Devin and they went out on the porch, where a heated discussion took place. Lieutenant Elliott, who was hosting the party, spoke to Lewis about his behavior. In later court testimony Elliott said Lewis was intoxicated when he arrived, but it must not have been very serious, as he offered the young men a brandy to calm them down.

Lewis felt his honor had been insulted and challenged Lieutenant Elliott to a duel. Dueling, or “affairs of honor,” were a common practice among gentlemen of the upper classes and considered a mark of prestige.149 They were, however, illegal under military regulations, and Elliott responded with a demand for a court martial. The trial ended with Lewis being acquitted “with honor.” Anthony Wayne wrote:

The Commander in Chief confirms the foregoing sentence of the General Court Martial, and fondly hopes that this is the first, that it may also be last instance in the Legion, of convening a Court Martial for a trial of this nature.150

After the trial ended on November 7th, 1795, Lewis was reassigned to the Chosen Rifle Company, an elite group of 75 riflemen commanded by William Clark, who had just arrived back at the fort.

Clark had been sent on a mission by General Wayne to deliver a letter of protest to Spanish Governor General Manuel Gayoso de Lemos at New Madrid. The letter objected to a Spanish fort being built on American territory at the Chickasaw Bluffs, some hundred miles south of New Madrid. Clark, who had visited Chickasaw Bluffs on a special assignment in 1792, delivered the letter to Governor Gayoso under a flag of truce. Accompanied by a sergeant, a corporal and 15 privates, he was away on his mission from September 15th-November 4th.

According to information Clark received from other travelers, the fort at Chickasaw Bluffs was 2/3’s completed and had about 500 men, considerable cannon, and three galleys (warships) and one galliot (a smaller ship) attached to it. After it was completed, another fort, close to the junction of the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers, was going to be built.

William Clark delivered Wayne’s letter to Governor Gayoso, containing an extract of Knox’s secret instructions to the Fort Massac commander, which authorized the use of force to prevent American citizens from invading Louisiana—that is, George Rogers Clark’s French Revolutionary Army. He most likely was not aware of its contents. Wayne wrote to Gayoso:

… the United States are disposed to preserve peace and harmony with all the powers of Europe and with Spain especially. As a convincing proof of this fact, I take the liberty of inclosing a printed proclamation of the President of the United States of America of March 24, 1794, together with an extract from the orders given by me to the commandant of fort Massac at the same time.

Gayoso’s superior, the Spanish Governor of Louisiana and West Florida, Baron de Carondelet, reported to his superior in Spain that Wayne’s extract of Knox’s secret instructions to him said:

You know that a number of lawless people living on the shores of the Ohio, affronting the national authority, have conceived the bold design of invading the Spanish territory. The atrocity of this attempt and its effects are manifest in the enclosed Proclamation of the President of the United States.

If they should persist in the same design or desire again to attempt it, and if any party present itself in the vicinity of the garrision, if you find yourself well informed that they are armed and prepared for war with the criminal intent reported in the Presidents Proclamation, you shall send them some person in whose veracity you can trust, and if he is a justice of the peace he will be the most appropriate messenger for making them comprehend their unlawful procedure and for preventing them from passing the fort at their risk; but, if, in spite of the pacific efforts made to persuade them to abandon their criminal design, they still persist in trying to descend the Ohio, you must make use of all military means in your power to prevent them. For which these instructions will serve you as sufficient justification, provided you have beforehand employed all the pacific steps first prescribed.

Secretary of War Henry Knox ordered Fort Massac to be built on the site of the old French Fort Massaic in order to repel any advance by Clark’s army.151

Fortunately, the Treaty of San Lorenzo (Pinckney’s Treaty) signed on October 27, 1795 in Madrid, ended the conflict. The treaty opened navigation on the Mississippi to Americans, and there would be no deposit fees collected in New Orleans to transfer goods between ships. The treaty also provided for a joint boundary line commission to survey the boundary line separating Spanish West Florida and East Florida from United States territory at 31 degrees north latitude.

After he made his report to General Wayne, the 25 year old Clark requested a leave of absence to take care of business in Kentucky and Virginia. His furlough extended from December through May, 1796. Upon his return in May, he wrote to his sister Fanny in Louisville—

… my reception from the general at my arrival was more favorable then I had any reason to expect, from my inattention to his orders to return at a State time—but as he is a reasonable as well as a Galant man, and had some Idea of my Persute, he treated my inattention as all other good fathers would on the Same acasion (Galentrey is the Pride of a Soldur—and attachment followers in corse.)152

Clark’s “Persute” must have been a romantic one, as most of his letter is concerned with the young ladies of Louisville. The general who was so “Galant” was Wilkinson, because Wayne was in Philadelphia. Obviously—despite a decade of deceit—the Clark family was still unaware of Wilkinson’s treacheries.

William Clark resigned from the Legion of the United States on July 1, 1796 and returned to Louisville to begin helping George Rogers take care of his financial affairs. The time that Lewis and Clark spent together in the legion was only a “fiew months” as Clark reported to the editor of the Lewis and Clark Journals in 1811.153 Their close friendship must have developed during Clark’s visits to Washington while Lewis was serving as President Jefferson’s private secretary in 1801–03, but again there is a lack of records.

The quarrel between Generals Wayne and Wilkinson continued. General Wayne went back east first. When he arrived at Philadelphia, the seat of the federal government, on February 6, 1796, he was greeted with a triumphal arch over his parade route, fireworks displays, and banquets.154 The general remained in Philadelphia for several months. His wife had died in 1793 and he was courting Mary Vining, an old friend whom he planned to marry.

In May, Wayne received a letter from the new Secretary of War, James McHenry, warning him that President Washington had learned there were three foreign agents going west from Philadelphia: a French general, Victor Collot, his map making adjutant, Joseph Warin, and an agent of the Spanish named Thomas Power, who was suspected of being involved with Wilkinson. Wayne was urged to keep a close watch on all three. He followed them west, returning to Fort Greene Ville in July.

En route, on June 27th,Wayne reported from Pittsburgh to Secretary McHenry he had learned that Collot had arrived at Fort Washington to meet General Wilkinson, with a “bushel of introductory letters” and Collot had purchased horses in order to overtake Wilkinson, who was on his way to Fort Detroit. He also learned Thomas Power was traveling incognito with Judge Sebastian (Wilkinson’s associate and a Spanish pensioner) on his way to Kentucky. General Wayne wrote:

I shall follow close in the rear of those incendiaries & doubt not of making the necessary discoveries in due season & without alarm.154

After he reached Fort Washington, on July 8th, Wayne reported to McHenry that Wilkinson had met with Power for several days at Fort Greene Ville, and an informer said that Wilkinson had promised Power a reward of $1,000 if he would either bring Robert Newman to Wilkinson, or provide Wilkinson with Newman’s answers to a set of questions—but only if Newman answered them satisfactorily. Wayne wrote that the informer told him Power had—

… shewed [him] certain instructions from Wil___son [Wilkinson] to put a suit of interrogatories to a Certain Newman & if he answered them to satisfaction, he wou’d reward him powers with One thousand Dollars either for them or the person of Newman. Powers had a number of letters for W___son and gave out that his object in visiting Greene Ville was to obtain materials for writing a history of this country &c.155

Wayne also learned General Collot had changed his mind about following Wilkinson north and instead had sent by “safe express” a “great Number of letters” to the “great & Popular Genl” and intended to wait a week or ten days for his reply at the Falls of the Ohio.156

In Philadelphia, Secretary McHenry wrote a private letter to General Wayne on July 9th, advising him:

Conciliate the good will and confidence of your officers of every rank; even of those who have shewn themselves your personal enemies. Gen. Wilkinson has entered upon a specification of his charges against you both old & new, and will press for a decision inquiry or court martial. I shall, unless I should be of opinion on reflexion that it is improper, send them to you in their condensed form, that you may prepare to meet them should it become necessary.157

Wilkinson’s offer to pay $1,000 to Thomas Power for access to Robert Newman shows that he desperately needed to know what Newman had revealed about Wilkinson’s dealings with British officials in Canada. The Governor of Canada, John Graves Simcoe, wrote that Newman “had been sent for some sinister purpose,” and Alexander McKee, who owned the trading post near Fort Miami, said “Newman was not the character he represents.”158

Newman was acting as Wayne’s secret agent. What seems evident—from Wilkinson’s distress—is that Newman had given Wayne a letter written by Wilkinson to British officials, and that Wayne had substituted another letter containing a mix of false information for Newman to deliver to the British. The British Governor Simcoe said the letter contradicted information supplied by Wilkinson in previous letters.

If Wayne had possession of Wilkinson’s original letter, Wilkinson’s career in the army would be destroyed. It seems likely Wayne did have this letter, and it would be presented as evidence during the impending military court of inquiry.

Wilkinson was able to offer Power $1,000 for information because he was about to receive money from the Spanish government. Power had come to the fort to arrange for delivery of $9,640 to Wilkinson from Governor Carondelet. It was restitution for the money he had not received in 1795, due to the murder of Owen and the dereliction of Collins. $640 of the amount was owed to Power for the delivery.

The 9,640 silver dollars were packed in barrels of coffee, sugar and tobacco at New Madrid. An informant at New Madrid warned Wayne that money was being sent by boat to Wilkinson, but a search by the commander at Fort Massac failed to reveal the contraband. Wayne fumed that he should have realized that sending tobacco to Kentucky was absurd because “it is one the principal stapel’s of that State.”159 The barrels of silver dollars were put in the care of Philip Nolan, the general’s young protege, who delivered them to a store in Frankfort where the barrels were unpacked in front of Power and Nolan.160 (This all became a matter of sworn testimony and documentary evidence during congressional investigations in 1808.)

When General Wayne returned to his command in the Ohio Valley, he had survived a political attack in Philadelphia. Wilkinson—knowing the Secretary of War supported Wayne—had lobbied Republican members of Congress to replace Wayne with himself, by establishing that a brigadier general would command the peacetime army (his own rank). The House of Representatives voted to reduce the authorized strength of the army by 60% to 2,000 men and 1,000 artillerists and engineers, and to eliminate the rank of major general. The Senate agreed to the reduction of the army, but refused to abolish Wayne’s position. The actual size of the army remained unchanged, and Wayne was guaranteed his position until the next session of congress met in early 1797.161

There was strong sentiment in favor of state militias and abolishing, or severely limiting, the national army. The federal government had been in existence for only seven years, and it was just twenty years since the colonies had declared independence from Great Britain. A standing army in peacetime was perceived as a threat to liberty. Ironically, however, the Military Act of 1796 actually marks the beginning of the peacetime regular army.162

Wilkinson renewed his attacks on Wayne by pressing for a military court of inquiry regarding Wayne’s leadership and tactics in winning the Battle of Fallen Timbers. Since only the commanding general—Wayne himself—had the power to convene a court of inquiry, President Washington and his cabinet procrastinated. Wilkinson came to Philadelphia in October, 1796 and threatened to bring the matter before Congress if the administration didn’t act. The attorney general finally ruled that Wayne could be tried if President Washington authorized the court of inquiry.163

General Wayne, who was on a tour of the forts acquired from the British, had established headquarters at Fort Detroit. By the 20th of September, he was able to announce that the United States had taken possession of all the British forts in the Northwest: Michilimackinac, Detroit, Miamis, Niagara, and Oswego. He had hoped to visit Michilimackinac, but the approaching season of winds and ice on the river made travel impossible until spring.164

On October 28, 1796 General Wayne wrote to Secretary of War McHenry charging that his impeachment trial was criminally motivated, and that Wilkinson was colluding with Thomas Power and others:

Thus Sir the three week visit to Greene Ville by P….r in June last, was not idly spent, but rather improved in maturing the plan for a seperation of the Western Country from the Atlantic States. The frequent and long interviews between W… and P….r & J. Br-wn, have not for the object the peace & happiness of the Union, in that which took place at Fort Washington the latter end of August, it was (among other necessary preparatory business) determined to remove me from the head of the Army by Impreachment, for piracy in order to make way for W … … son & thereby facilitate the accomplishment of their favorite Object, a seperation from the Union.165

General Wayne gave Ensign Meriwether Lewis a leave of absence until March 4th, 1797. On November 7th, Lewis left Fort Detroit to bring dispatches to Philadelphia containing the service records of the late Legion of the United States and Wayne’s reorganization of the infantry and dragoons in the new United States Army.166 Historian Grace Lewis Miller speculates Lewis may have carried a second set of Wayne’s papers regarding Wilkinson, as it was common practice to send duplicates by a separate route.167 It was a mark of regard for Lewis’s abilities to be given such an important assignment at 22 years of age.

A four month leave of absence gave Lewis the opportunity to return home to Albemarle County for the holidays. It had been a little over two years since Lewis left home with the Virginia militia to camp at McFarlane’s farm during the Whiskey Rebellion. He had joined the Legion in May, 1795, been present at the Treaty of Greene Ville with the northwest tribes, gone through a court martial over his dueling challenge, become friends with William Clark, and now was entrusted by the commanding general to carry the army’s most important records of service.

On November 12th, General Wayne notified McHenry the dispatches were on their way, and he would be traveling by the sloop Detroit to Fort Presque Isle on Lake Erie, where he would write to him again. Wayne was planning to establish his permanent headquarters at Pittsburgh, as it was equally distant from Fort Washington at Cincinnati and Fort Detroit, and convenient to the government at Philadelphia. It was the last letter that Wayne wrote to the War Department.

The death of Anthony Wayne occurred at Fort Presque Isle on December 15th, 1796. He was 51 years old. Presque Isle which means “almost an island” in French, was the piece of land with a narrow neck which formed a harbor for the new town of Erie, Pennsylvania. The fort, located on the bluff overlooking the harbor, had originally been a French fort and then a British fort. It was now under the command of Captain Russell Bissell.

Wayne was suffering from gout in his leg, his old complaint aggravated by the injuries sustained by the falling tree, when he arrived at the fort on November 18th. On November 29th, Captain Bissell wrote to Major Isaac Craig, at Pittsburgh:

… the Gen has been exceedingly ill ever since his arrival but is now recovering. I expect in a few days he will be on his way to Pitt.

A week later, the general was suffering from violent stomach pains and high fever—and it was reported that the gout had settled in his stomach. His adjutant, Henry Debutts, wrote on December 14th:

The Gout fixed itself in the Generals stomack about a week since & continues with unabated violence—how long he continues to suffer such torture is hard to say—but it appears to me that nature must soon sink under such acute affliction.168

Wayne was attended by Dr. George Balfour, a surgeon’s mate, at the fort. Balfour, in announcing the death of the general, described the general’s illness on December 14th:

… you have heard of General Wayne’s arrival here from Detroit of his having the gout very badly. 11 days ago he was attacked with gout bilious in the stomach & bowels …

In his brief letter, he ends by requesting a quarter of a cask of wine be sent to him.169

Before a year passed, Balfour was recommended by General Wilkinson to become one of the first surgeons in the United States Navy, serving on board the frigate Constellation under Captain Thomas Truxton. Truxton wrote that General Wilkinson had recommended Dr. Balfour as “an officer of professional skill, honor, and strong sensibility.”170

General Wayne asked for his physician, Dr. J. C. Wallace, to come to Presque Isle from Fort Fayette at Pittsburgh and a messenger was also sent to Dr. Benjamin Rush in Philadelphia. Dr. Wallace arrived a few hours after Wayne died.

Gout is a painful form of arthritis that attacks the joint of the big toe, or perhaps the joints of the knees, wrists or fingers. There is no such thing as “stomach gout.” However, arsenic was the poison of choice for many centuries—called the “King of Poisons” and the “Poison of Kings.” The symptoms of acute arsenic poisoning are headaches, violent stomach pain, convulsions and diarrhea. It is odorless and tasteless, and ingesting a small amount over a few days will kill a person. There was no test to detect its presence in the body until reliable tests were developed in the 1830’s. After that, arsenic as a method of poisoning declined in use. By the middle of the 1800’s it became a standard practice to use arsenic to embalm a body.

General Wayne, at his request, was buried at the foot of the flag pole at Presque Isle in his uniform with his boots on. In 1808, his daughter, being in ill health herself, asked to have her father’s remains reburied at the family cemetery in Radnor, Pennsylvania near Philadelphia. In the spring of 1809 his son Isaac went to Presque Isle with a horse and small carriage to bring his father’s remains back home. Dr. Wallace was now practicing in Erie, and Wayne’s son asked Dr. Wallace to take care of the exhumation. He did not want to witness it himself.

Thirteen years had passed since the general died, but upon opening the grave, to everyone’s astonishment, Wayne’s body was perfectly preserved, except for his bad leg and foot, which was partially decomposed. Dr. Wallace proceeded to boil the flesh from his bones so that the bones could be packed in a small box and taken to his new burial ground. The remains of his flesh were reburied at the fort in the same grave.171

A lock of the general’s hair was saved as a souvenir, and is still part of the collection of the Erie County Historical Society. Was it arsenic poisoning? “Arsenic mummification” was believed to occur during the time when arsenic was used as a poison. According to embalming practices, the small amount needed to kill a person, would not be nearly enough for embalming. But arsenic was in common use as treatment for syphilis, as a face powder, in bullet manufacture, in paint manufacture, and as a recreational drug at that time.172

Perhaps a forensic examination of the general’s hair will reveal the presence of arsenic. The circumstantial evidence certainly supports the idea of another assassination attempt by General Wilkinson—and a successful one. There was a motive, a strong motive, and there seems to have been an agent, George Balfour, a surgeon’s mate at an obscure army post, who was rewarded with the plum assignment of becoming a naval surgeon of the United States Navy. There was also an opportunity for General Wilkinson to have arranged for the assassination at Fort Presque Isle when he traveled to Philadelphia in October.

Assassinations, if cleverly done, are meant to seem like accidents, illnesses, or random killings by deranged individuals or petty criminals. The very word, “assassination” means a killing of a prominent person, usually by a secret attack. Humphrey Marshall suspected Wilkinson of arranging the assassinations of the two army officers Hardin and Trueman, and he said that he himself had been the object of an attempted assassination by someone who was a “catspaw” of powerful individuals. General Wayne called General Wilkinson “that vile assassin” in his letter to the Secretary of War. Was Wayne referring to the tree falling on his tent?

General Wilkinson was a man under extreme pressure. He couldn’t win his court of inquiry case against Wayne which was based on the charge that General Wayne had mishandled the winning of the Battle of Fallen Timbers. Wayne would probably have produced the letter carried by Robert Newman—the one Wilkinson would pay $1,000 to learn about. However, with the death of his superior, James Wilkinson would become the Commanding General of the United States Army, and that is what happened next.

Anthony Wayne statue at Valley Forge National Historic Park looking towards his home in Paoli, Pennsylvania, 5 miles from Valley Forge. The family home was built by his grandfather in 1774. Historic Waynesborough is open to visitors. His grave is at Old St. David’s Churchyard in nearby Radnor, PA. www.historicwaynesborough.org (Wikimedia Commons)

Mississippi Valley in the 1790’s