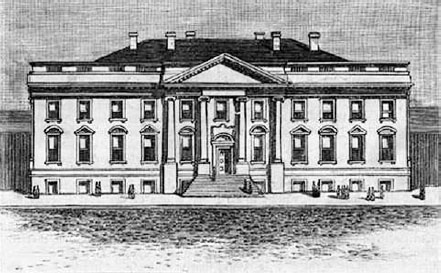

During the two and a half years Meriwether Lewis lived with Jefferson in the President’s House—as the White House was first called—the building was unfinished. The huge East Room measured about 80 by 37 feet with a 20 foot ceiling. Its walls and ceiling were still unplastered, and the ceiling leaked. Next to the private dining room, two rooms with canvas walls were erected for Lewis on the south corner which served as his office and living quarters. The East Room also housed Jefferson’s collection of mounted animals and Indian artifacts, which were later moved to the entrance hall.

A temporary wooden walkway and staircase led to the entrance on the north side of the building (shown above). The Adams’s had used the Oval Room as an entrance during their brief stay, but Jefferson shut off the entryway and followed the original architectural plans for a north entrance. It was the largest house in the United States until the end of the Civil War.270

Margaret Bayard Smith, a frequent visitor and friend, whose husband Samuel Harrison Smith was the publisher of The National Intelligencer, wrote the following description of the room where Jefferson’s cabinet officers met, which was located on the southwest corner with a view of the Potomac River:

It was a spacious room. In the centre was a long table, with drawers on each side, in which were deposited not only articles appropriate to the place, but a set of carpenter’s tools in one and small garden implements in another from the use of which he derived much amusement. Around the walls were maps, globes, charts, books &c. In the window recesses were stands for the flowers and plants which was his delight to attend and among his roses and geraniums was suspended the cage of his favorite mocking-bird, which he cherished with particular fondess, not only for its melodious powers, but for its uncommon intelligence and affectionate disposition, of which qualities he gave surprising instances. It was the constant companion of his solitary and studious hours. Whenever he was alone he opened the cage and let the bird fly about the room. After flitting for a while from one object to another, it would alight on his table and regale him with its sweetest notes, or perch on his shoulder and take its food from his lips. Often when he retired to his chamber it would hop up the stairs after him and while he took his siesta, would sit on his couch and pour forth his melodious strains. How he loved this bird! How he loved his flowers! He could not live without something to love, and in the absence of his darling grandchildren, his bird and his flowers became the object of his tender care.271

Meriwether Lewis’s salary was paid by Jefferson, $500 and then $600, annually.272 He worked as an aide de camp, and courier for the president, and liked to hunt for game in the early morning hours to serve at the dinner table. He did not serve as a secretary for Jefferson, despite his title. Someone else did the secretarial work. Instead, he was there as a protégé for Jefferson, being trained in the sciences to lead the expedition to the Pacific.273

Jefferson and Lewis lived alone in the White House with a small staff of servants. For a few months in the spring of 1801, James and Dolly Madison lived with them before moving into their own house. Jefferson wrote to his daughter:

Mrs. Madison left us two days ago to commence housekeeping, so that Capt. Lewis and myself are like two mice in a church.274

Jefferson had a unique style of political influence and promoting harmony. He hosted dinner parties up to five times a week in his private dining room, which had a large, oval-shaped, dining table which could seat 15 guests when it was expanded. When he hosted small dinner parties of not more than four people, he used “dumbwaiters”—serving shelves on casters which held all the dishes required for the entire meal, and told no tales of private conversation.275

He followed a policy of pêle-mêle in seating arrangements. There was no hierarchy or social pecking order. British Foreign Minister Anthony Merry and his wife Elizabeth were shocked by the lack of protocol, and after their first experience, refused to attend any more dinners. Jefferson wrote:

They [the British minister and his wife] claim at private dinners (for of public dinners we have none) to be first conducted to dinner and placed at the head of the table above all other persons, citizens or foreigners, in or out of office. We say to them no; the principle of society with us, as well as of our political constitution, is the equal rights of all; and if there be an occasion where this equality ought to prevail preeminently, it is in social circles collected for conviviality. Nobody shall be above you, nor you above anybody; pêle-mêle is our law.276

Lewis would have sometimes served as a substitute host at the dinner table, according to William Seale, author of The President’s House. Later records indicate Jefferson’s family, his secretary, and house guests were automatically included in the dinners.277 Mrs. Smith wrote about his dinner parties:

While Congress was in session, his invitations were limited to members of this body, to official characters and to strangers of distinction. But during its recess, the respectable citizens of Alexandria, Georgetown and Washington were generally and frequently invited to his table.

The whole of Mr. Jefferson’s domestic establishment at the President’s House exhibited good taste and good judgement. He employed none but the best and most respectable persons in his service. His maitre-d’hotel had served in some of the first families abroad, and understood his business to perfection. The excellence and superior skills of his French cook was acknowledged by all who frequented his table, for never before had such dinners been given in the President’s House, nor such a variety of the finest and most costly wines. In his entertainment, republican simplicity was united with Epicurean delicacy; while the absence of splendour ornament and profusion was more than compensated by the neatness, order and elegant sufficiency that pervaded the whole establishment.278

No dinner lists have been found for 1801–1803, but records for 1804–1808 show Jefferson carefully noted who was invited and how often they attended. Women were rarely invited. The dinners were Jefferson’s means of exerting political influence and guests were invited according to party affiliation. In rotation, only Republican or only Federalist congressmen attended the dinners, generally eight at a time.279

This was an amazing opportunity for Lewis to participate in the inner workings of government. If he had lived beyond the age of 35, he could well have become one of the Virginia dynasty of presidents.

One of Lewis’s duties was to help “Republicanize” the army. Jefferson’s invitation to join him said Captain Lewis was being recruited—

… to aid in the private concerns of the household, but also to contribute to the mass of information which is interesting to the administration to acquire, your knoledge of the Western country, of the army and of all it’s interests & relations has rendered it desirable for public as well as private purposes that you should be engaged in that office.280

As soon as Jefferson became president, efforts began in earnest to establish an academy for training officers—something Hamilton and Adams hadn’t been able to accomplish during Adams’s administration. Within the month, Secretary of War Henry Dearborn appointed Jonathan Williams to become the head of the new West Point Military Academy on the Hudson River. The school would recruit and train a corps of young Republican officers.281

In July, 1801 the War Department supplied a list of 269 commissioned officers to the President. Using a set of secret signs—circles, crosses, symbols, and dot combinations—Meriwether Lewis evaluated officers in the following manner:

(1) “1st Class, so esteemed from a superiority of genius and military proficiency.”

(2) “Second Class, respectable as officers, but not altogether entitled to the first grade.”

(3) “Unworthy of the commissions they bear.”

(4) “Republican.”

(5) “Opposed to the administration, otherwise respectable officers.”

(6) “Opposed to the administration more decisively.”

(7) “Opposed most violently to the administration and still activte in its vilification.”

(8) “Professionally the soldier without any political creed.”

(10) “Officers whose political opinions are not positively ascertained.”

(11) “Unknown to us.”282

Lewis made no evaluation of General Wilkinson, whose name was the only one left blank in the evaluation column. Of the six officers assigned to Wilkinson’s General Staff, five received the ranking of “opposed most violently to the administration and still active in its vilification,” and the sixth was “opposed to the administration more decisively.” Three were discharged and one was reassigned. Their positions were filled by civilians, because there were not enough high ranking Republicans to replace them.

The reduction of the army as a cost-cutting measure allowed for the removal of officers who were either incompetent and/or opposed to the administration. Enlisted men were retained. Captain Lewis knew all but 25 of the 269 officers listed. He was unable to identify the politics of 139 officers (10 & 11), but could offer an opinion on the remaining 130.283 By creating a new grade, that of ensign, below the rank of 2nd lieutenant, twenty new Republican officers were added. Altogether, 88 officers were dismissed and the reorganized corps of about 162 officers now contained at least 29 Republicans.284

Where was General Wilkinson while all this was happening? In March, 1801, he had applied to become Governor of Mississippi Territory at Natchez, but his request was denied. The general was absent from Washington during the reorganization of the army. He and his friend, Major Jonathan Williams, spent the spring of 1801 on an inspection tour of the northeastern frontier. At Fort Niagara, they made plans to build a military road between Lakes Erie and Ontario, and then went on to army headquarters in Pittsburgh.

The next year, after Congress passed the Military Peace Establishment Act of March 16,1802, Williams would become the first Superintendent and Chief Engineer of the United States Military Academy at West Point. He had received an army commission in November, 1800 upon the recommendation of General Wilkinson, although he had no prior military experience. He was an expert on artillery and fortifications, a member of the American Philosophical Society, and the grandnephew of its founder, Benjamin Franklin.

Jonathan Williams (Wikimedia Commons)

The two friends would then go onto to the semi-secret military base on the Ohio. Major Williams traveled to Cantonment Wilkinsonville in July in advance of Wilkinson. On July 2nd, the day of his departure from Pittsburgh, Wilkinson instructed Williams, who was traveling with the general’s musicians—

Silence your music in passing & while at all villages …. the hills resound and the vallies ring—but give no occasion for those who listen with invidious pleasure to fasten upon us the foul imputations of Ostentatious Pomp & parade at the public expense—a word to the wise—hasten or I shall overtake you before you reach the falls.285

Wilkinson and Major Williams arrived together at the cantonment on July 29, 1801. Wilkinsonville had reached its maximum strength of about 1,500 men, or almost half of the troops of the U. S. Army during that summer. 21 units of the army were stationed there, and a large amount of artillery and ammunition was sent to the cantonment before the Major’s arrival.286 It was obviously planned as a training exercise for the army in anticipation of a French invasion of Louisiana or a slave revolt—both real possibilities in 1801–1803. The general remained at the cantonment until August 4th, when he left to conduct treaty negotiations with the Indians. Major Williams stayed behind, in charge of the artillery units.287

Lieutenant Colonel David Strong was commander of the cantonment. He was a Revolutionary War veteran, who had served at the Battle of Lexington and wintered at Valley Forge in 1777 and 1778. He served as Commander of the Second Sub-Legion at the Battle of Fallen Timbers. He was commander of Fort Wayne in 1796–98, and of Fort Lernoult (Detroit), before assuming command of Wilkinsonville. He had undoubtedly known General Wilkinson since the early days of the Revolutionary War, and they must have been enemies, because he was highly regarded by General Wayne.

Colonel Strong, died suddenly after a fall from his horse on August 19, 1801. The question is—was he another victim of an assassination by Wilkinson?288 What are the indications, and what would be the motive?

Colonel Strong arrived with the first troops on January 1, 1801. The camp was struck by a tornado on March 13th, killing one man and injuring several. By late April, surrounded by wetlands, as many as three or four men were dying daily from fever and dysentery.289 The camp lacked medicine and hospital supplies. In June, newspaper stories caused the new Secretary of War to order the cantonment abandoned.The cantonment had been built near the Grand Chain of Rocks, a six mile stretch of rocks in the middle of the Ohio River. Low lying river land was associated with malarial fevers, but it was not suspected the bites of infected mosquitoes caused the fevers during the “sickly season.”

When the general heard the news of Colonel Strong’s death from Major Williams, he reported to Secretary of War Henry Dearborn on September 8th, that the colonel had died from:

an acute nervous affection which rendered an almost immediate insensibility … [different from that] ascribed from the climate or to the causes which have affected [the other soldiers at the cantonment].290

The Western Spy newspaper in Cincinnati announced the death of Colonel Strong in its October 10th issue:

Died at Wilkinsonville on Wednesday, the 19th of August, after an illness of only 40 hours, as universally regretted as known, DAVID STRONG, lieutenant colonel commander of the 2nd United States’ regiment of infantry.291

The Strong Family Papers cite a letter from the Inspector General of the Army, dated October 9, 1801:

I have just heard of the death of Col. Strong. He fell from his his horse on the anniversary of the day when he bravely fought in that memorable battle under the gallant Wayne in the Maumee Valley in August, 1794. 292

So it would seem, based on the three accounts, that the colonel was sick for 40 hours; that it was not malarial fevers or dysentery, but a “nervous affection;” and that he fell from his horse and died. As an assassination theory, an associate of Wilkinson could have administered arsenic to Colonel Strong. Arsenic can cause death within a matter of hours or a few days. Wilkinson was always careful to keep one step removed from any wrong doing, and he always had an alibi.

What would have been his motive in arranging for an assassination? Strong must have known of a Burr-Wilkinson conspiracy to create a military base for an invasion of Spanish territory. Such information would have ended the general’s army career, as he already was widely accused of being a Spanish agent. This is what all of his possible victims of assassination have in common—they were his rivals in the army, and/or they could have jeopardized his career by revealing damaging information.

There is a very odd letter written by General Wilkinson in reply to a letter written by Major Williams announcing the death of Colonel Strong at the cantonment. On September 6th, General Wilkinson replied to Williams from the Indian Commissioners’s camp at Southwest Point, Tennessee:

I the last evening at 9 oclock received your affecting detail of the Death of our friend & Brother Soldier Col Strong, which produced a twinge of anguish I have seldom experienced, but a moments reflecion dissapated my concern for the Dead and excited all my cares & anxieties for the living. The good widow has all my sympathies & I have given orders for whatever she may need….

Having submitted to my discretion, your Eulogium over our gracious, noble minded, brave Friends remains; I obey the obligations of Candor & affection when I observe to you that, in my judgement, it has been too hastily conceived to be submitted to the press—it has been written under the strongest impulses of the affections & does Honor to your Heart, but the colourings are too strong for the cool examiner and an ardent imagination has overleaped the bounds of congruity & obscured essential distinctions—I shall offer no apology for this liberty, being assured I shall find one in your own Bosom.293

Either Major Williams had already sent the eulogy to The Western Spy newspaper in Cincinnati, or he disregarded the general’s request to not publish it in the press. It appeared in the newspaper on November 7th. The eulogy began:

That robust body of which health had appeared to have firm possession; that piercing eye, expressive of military ardor, and that attentive ear, hitherto open to every just complaint, now appears before you, a lump of lifeless clay, and you will soon see it mixed with its mother earth….Take, my fellow soldiers, your last look, see where he lies—the sad but faithful picture of human frailty! Alas! His body moves not…. But two days ago you saw him mounted on yonder steed; from that (now vacant) seat he gave his orders; and when he spoke you heard the dignity of command combined with the mildness of affection. He loved you all—himself a veteran, he could not fail to be the soldiers friend. His heart was by nature kind, the blood that runned from it through all its various channels, was the very milk of humanity.294

The eulogy continued to extoll the virtues of the colonel. General Wilkinson may not have wanted to have on record in a newspaper article, “That robust body of which health appeared to have firm possession; that piercing eye …,” rather than jealousy over whether Williams was praising Colonel Strong too highly.

The other odd thing about Wilkinson’s letter is his use of a cipher code over the word “Dead.” Wilkinson used a cipher in corresponding with Aaron Burr and Spanish officials.These markings—a series of three symbols—appear to be a cipher, but what it means is unknown. It could have something to do with the scratched out word above the cipher, where the words “moments reflecion” are found. For whatever reasons, it definitely appears to be a cipher. The discolorations are due to writing showing through from the back side of the paper.

I leave it to the reader to decide whether the death of Colonel Strong should be added to the list of possible assassinations by General Wilkinson. Admittedly, it is speculative. The colonel was 57 years old when he died. What qualifies it, in my opinion, is Wilkinson’s attempt to minimize his death by telling Williams not to publish his eulogy; the odd cipher marks in his letter; the contradictory reports of how Strong died; and that he might have revealed a conspiracy to invade Spanish territory under a Burr presidency. The colonel’s log books for Wilkinsonville are missing.

Major Williams served as commander of the cantonment until he returned to the east coast in late October. He supervised the cleaning up of the camp and the care of the men who were too sick to be moved. Most of the troops were moved to new camps, but the artillerists and engineers remained at Wilkinsonville in addition to a company of the 2nd Infantry. On October 13th, General Wilkinson returned to conduct military exercises with the assembled troops.

Major Williams had selected a new site, six miles west of the cantonment, where two companies of artillerists were stationed after his departure. Troops were scattered along the Ohio from the Cumberland and Tennessee Rivers to the new camp, 13 miles east of the Mississippi and Ohio confluence. The cantonment was still being used as a “customs house,” or port of entry, for the United States in April, 1802 when a small contingent of troops were stationed there. When the Lewis and Clark Expedition headed west in the fall of 1803, at least five members who had been stationed at Wilkinsonville were recruited for the expedition at Kaskaskia, Illinois.295

With the western side of the Mississippi under the control of Spain, the army could not rely on moving troops and supplies on the Mississippi River in the event of a war with France. As soon as possible, treaties needed to be signed with Indian tribes, military roads built through Indian territories, and forts established.

General Wilkinson and the two other Indian Commissioners, Benjamin Hawkins and Andrew Pickens—who were both highly respected Indian agents—first met with the chiefs of the Cherokee on September 4, 1801 at Southwest Point.The chiefs had gone to Washington in June, where they had met with Secretary of War Dearborn. They refused to sell any of their land or allow roads to be built.

The commissioners next met with the high chiefs and principal men of the Chickasaw Nation at Chickasaw Bluffs on October 21–24, 1801. The commissioners asked permission to improve the path from the white settlements at Natchez to settlements on the Cumberland River. This is the road that became known as the Natchez Trace.

After a day’s discussion, Major Colbert, a mixed blood chief of the Chickasaw, replied they were very glad to hear they would not be required to cede any land. They agreed to the building of a wagon road through the nation, but refused to allow building houses for travelers. They wanted time to consider how they could benefit from it, but in the meantime they would always supply provisions to travelers. It was agreed that the ferries over the rivers would be the property of the Chickasaw. They were given $702 in goods in return for their permission to build the road. On October 27th, Wilkinson reported to Secretary of War Dearborn he had ordered eight companies of the 2nd Infantry to begin work on the road.

The commissioners next met with the Choctaw Nation at Fort Adams, whose chiefs agreed to a road being built between Fort Adams near Natchez to Walnut Hills on the Yazoo River (present day Vicksburg). In addition, the Choctaw gave up possession of almost two million acres of land in return for $2,000. The land acquired from the nation was bounded by the 31st parallel on the south and the Yazoo River on the north, establishing the United States as the owner of that most desirable piece of property. The Treaty of Fort Adams was signed on December 21, 1801.

The commissioners then met with the Creeks who agreed to give up valuable agricultural land in exchange for a $3,000 annual payment and $25,000 in trade goods. The Treaty of Fort Wilkinson was signed on June 16, 1802. Fort Wilkinson was a trading house located on the Oconee River on Georgia’s Indian boundary line.296

Wilkinson separately negotiated another treaty with the Choctaw, signed on October 7, 1802 at Fort Confederation (Fort Tombecbe), located about 270 miles north of Mobile on the Tombigbee River. A new boundary line survey, road construction, and the establishment of a trading house were supervised by the general in 1803.297

The tribes were the “Five Civilized Tribes”—the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek and Seminole nations—who were descendants of the Mississippian culture whose towns had been inhabited by thousands of people before the arrival of Europeans in 1500. They had adopted many ways of Euro-American culture and were generally peaceful.

General Wilkinson, in summing up his experiences as an Indian Commissioner in 1802–03, wrote that he had:

… traversed a trackless wilderness four times, from the borders of Louisiana to the frontiers of Georgia, through the Choctaw and Creek nations; having traveled on public service in the years 1802–3, through forests, and by inland navigation, more than 16,000 miles.298

He reported he spent six months in which he had not slept under a roof and suffered from severe malarial fevers and other illnesses during his travels.299

The years of 1802–03 clearly indicate that General Wilkinson was willing to sacrifice personal comfort for the safety of the nation. He was not “in exile” from the seat of power, he was the power in the interior of the continent. In discussing the conspiracies he was involved in, it is challenging to follow his devious activities. But his years of treaty making with the Indians and road building through the early Southwest prove that he was indeed a patriot—even if, an unhappy one.

President Jefferson sent Meriwether Lewis to Capitol Hill with two copies of his State of the Union address on December 8, 1801. It broke precedent, as both George Washington and John Adams had delivered their messages orally before the joint session of Congress. On the same day, the text was published in Smith’s newspaper, The National Intelligencer.300

On New Year’s Day 1802, there was an open house at the President’s House. To the dismay of the ladies of Washington, Jefferson had abolished the weekly receptions of his predecessors. He chose instead to hold open houses on New Year’s Day and the Fourth of July, where he shook hands with all who wanted to attend, ending the custom of formal bowing.301

At this open house Jefferson was given a 1,235 pound Mammoth Cheese from the citizens of Cheshire, Massachusetts. The cheese bore the inscription: Rebellion to Tyrants is Obedience to God. It was the idea of a Baptist minister who wanted to emphasize the message of religious liberty in Calvinist New England and Baptist support for the new president. Over 900 Republican cows provided the milk to make the cheese. No Federalist cows were allowed.

The Mammoth Cheese was about four feet in diameter and 15 inches tall. It was kept in the East Room, where Meriwether Lewis’s canvas room was located. Finally at the open house on July 4th, 1803, in celebration of the Louisiana Purchase, the cheese was broken open and served to guests. Federalists said it was wretched, while Republicans raved about it.302

The president was generally accessible to visitors in the morning. He rose before dawn. For a couple of hours in the afternoon, he went for a solitary ride around Washington or out in the countryside where he visited farmers. Dinner invitations were for 3:30, when the daily session of Congress ended. The guests were gone by 8:00, and after that Jefferson could devote himself to his personal studies and correspondence.303

As his aide and secretary, Meriwether Lewis issued the dinner invitations, using printed cards that only needed the guest’s name and date of the dinner. The invitations were used after the chore of writing them became too burdensome.304 There would have been an endless series of tasks for the 27 year old, exposing him to the entire range of Jefferson’s multifaceted life.

Meriwether Lewis by St. Memin (1802), Library of Congress. Compare this St. Memin portrait with the frontispiece, which would have been made in 1807, after the expedition.

On April 19th, 1802, a young lawyer from Philadelphia, Mahlon Dickerson, was a dinner guest at the President’s House. He wrote to his brother about meeting the president:

He is accused of being very slovely in his dress, & to be sure is not very particular in that respect, but however he may neglect his person he takes good care of his table. No man in American keeps a better.305

Dickerson was four years older than Lewis. The two young men struck up a friendship, and the next month after Congress ended its session, Lewis traveled to Philadelphia while Jefferson was taking a two week vacation at Monticello.

Philosophical Society Hall in 1800. (Wikimedia Commons)

The two friends spent several evenings visiting with Pennsylvania Governor Thomas McKean. One evening they went with a group of friends to see a magician’s performance. They also visited Dr. George Logan, a founder of the American Philosophical Society, and attended a party at Alexander Dallas’s home.

They had their portraits made. On May 18th, Dickerson wrote that he “sat to St. Memin for my profile.” It’s likely Lewis sat for his profile on the same day.306 The artist, Charles Balthazar Julien Fevret de Saint-Memin, was a refugee from the French Revolution. During his exile in Philadelphia, he created portraits using a physiognotrace, a gadget invented by a French artist in 1783–4. A physiognotrace used a metal arm to trace the edge of a person’s profile while he was seated behind the instrument; the arm produced an image on paper using an identical movement. It took a skilled artist to effectively utilize it. The physiognotrace was similiar to the polygraph instrument that Jefferson would begin using in 1804 to make mechanical copies of his letters. Within the year, Charles Willson Peale would begin selling physiognotrace silhouettes at his new museum in the State House (Independence Hall).307

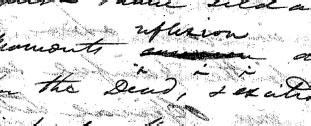

Peale’s Mammoth by de Montule (www.common-place.org)

Meriwether Lewis must have gone almost immediately to see the mastodon skeleton at the American Philosophical Society’s museum. In 1801, the society had sponsored Charles Willson Peale’s excavation of the prehistoric bones of the American incognitum in the Hudson River Valley. The skeleton, described as the “carniverous elephant of the north,” had gone on display on December 24, 1801. A national mammoth craze began while the excavation was taking place—including the making of the Mammoth Cheese. Admission was 50 cents to view the skeleton in the Mammoth Room at the Philosophical Hall. Lewis met with Peale during his visit and they talked about a skull Jefferson was sending to him.308

The assembled skeleton stood 11 feet tall at the shoulder, and was 15 feet from the chin to its rump. The tusks were 11 feet long. The tusks had been mounted upside down in the belief that the creature was a meat eater, and they remained that way until at least 1816 when a French traveler, Edouard de Montule, sketched the mastodon.309

Jefferson was president of the American Philosophical Society from 1797 to 1814. The giant mastodon became part of the national identity of the United States. It was America’s answer to European theories of “American degeneracy.” A French naturalist, the author of a 36 volume encyclopedia, the Comte de Buffon, asserted that the animals and people of the New World were inferior to the Old World—that they were smaller and less virile than their counterparts in Euope and Asia. Buffon’s encyclopedia was the first attempt to deal with a large number of evolutionary problems and his theory of “American degeneracy” was widely accepted in Europe.310

Jefferson had challenged Buffon’s theory in his book Notes on the State of Virginia, published in 1787. He made a chart, “A Comparative View of the Quadrupeds of Europe and of America,” and included the mammoth in his chart, writing:

It may be asked, why I insert the Mammoth as if it still existed? I ask in return, why I should omit it, as if it did not exist? Such is the oeconomy of nature, that no instance can be produced or her having permitted any one race of her animals to become extinct; of her having formed any link in her great work so weak as to be broken. To add to this, the traditionary testimony of the Indians, that this animal still exists in the northern and western parts of America … Those parts still remain their aboriginal state, unexplored and undisturbed by us, or by others for us. He may as well exist there now, as he did formerly where we find his bones.311

Did Meriwether Lewis think that he might be sent on a mission to discover whether mammoths still roamed in West? Perhaps he did. Within the year he would be back in Philadelphia making preparations to lead an army expedition called “The Corps of Volunteers for North Western Discovery.”

Jefferson had been alerted by a letter from a member of the American Philosophical Society to the American publication of Alexander MacKenzie’s Voyages from Montreal, on the River St. Laurence, through the Continent of North America, to the Frozen and Pacific Oceans; In the Years 1788 and 1793. The book had been published in England in 1801.312 Mackenzie’s Tour, as it was called, was an account of two expeditions across Canada to reach the Pacific Ocean.

“Alex MacKenzie from Canada by land, 22 July 1793,”a Canadian National Historic Site near Bella Coosa, British Columbia. The MacKenzie Rock inscription was engraved by surveyors from its original paint. (Wikimedia Commons)

His first expedition in 1788 had reached the Arctic Ocean in 1789, and his second reached the Pacific Ocean in 1793. MacKenzie, a Scottish fur trader and partner in the North West Company, traveled in a 25 foot long birchbark canoe with nine others: his cousin and second-in-command, Alexander MacKay; two Indian hunters/interpreters; six French voyageurs, and a dog.

Jefferson ordered MacKenzie’s book in June, along with a 1795 map by the English cartographer, Aaron Arrowsmith, “Exhibiting All the New Discoveries in the Interior Parts of North America.”313 Jefferson spent the months of August and September at Monticello in Albemarle County, avoiding the “sickly season” on the Tidewater and Lewis stayed nearby at the home of Dr. William Bache, located on the road to his mother’s home at Locust Hill.

They must have started talking about Lewis leading an expedition across the continent that summer. Jefferson had been attempting for twenty years to organize an expedition to the Pacific Coast—beginning with George Rogers Clark in 1783, then John Ledyard in 1785, and André Michaux in 1793. The 18 year old Lewis had applied to Jefferson to join Michaux’s expedition, but Jefferson turned him down.

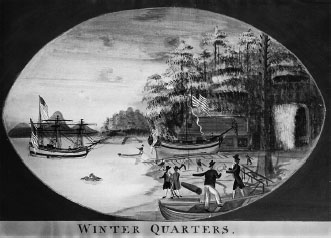

Winter Quarters of the Columbia Redidivia on the Pacific Coast in early 1792. (Wikimedia Commons)

All of these plans had the same objective: to discover the location of a navigable water route from the west side of the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific Ocean.

On May 11, 1792 an American sea captain from Rhode Island, Robert Gray, discovered the mouth of the “Great River of the West” and named it the Columbia River for his ship the Columbia Redidivia. For years, ships had unsuccessfully searched for the river mouth, concealed by rain and mist and a barrier of sand and gravel six miles long and three miles wide known as the Columbia Bar. The entire region is called the “Graveyard of the Pacific” for the thousands of ships which have been wrecked along its coast.

Alexander MacKenzie wrote that George Vancouver had discovered that the Columbia River was the only navigable river along the entire coastline, and that it was the key to a globe-circling trade in furs and fish. He wrote in possessing the Columbia—

… the entire command of the fur trade of North America might be obtained from latitude 48 North to the pole, except that portion of it which the Russians have in the Pacific. To this may be added the fishing in both seas, and the markets of the four quarters of the globe.314

MacKenzie had crossed the continent, but failed to find the Columbia. Gray had found the mouth of the river and named it, but had not traveled more than 15 miles up it. Under international law, discovering and claiming the mouth of a river established a nation’s right to claim ownership of all the land drained by the river and its tributaries. Gray’s discovery established the United States claim to the entire watershed of the Columbia River.

The Doctrine of Discovery dated back to 1455, when the Pope authorized European nations to claim lands inhabited by non-Christians who were not already the subjects of Christian monarchs. The right of first discovery allowed indigenous people to occupy their land, but they could only sell the land to the nation claiming first discovery. They could not sell their land to individuals or to other nations. The nation also had sovereign and commercial rights over the indigenous people.

The second stage of the Doctrine of Discovery required a nation to establish possession of the land by proving they had been there—burying coins in a bottle, lead plates in the ground, marking rocks and trees, planting flags and crosses, keeping journals and records, making charts and maps. The best way to confirm possession was to establish a settlement.315

Britain, Spain, Russia and the United States all had merchant ships on the Northwest Coast trading for sea otter skins to bring to China. Britain and Spain had almost gone to war in 1789 over their competing claims.The Nootka Sound Conventions of 1790–94 established San Francisco Bay as the northern boundary of Spanish control and that the Northwest Coast would be open to both Britain and Spain. It became increasingly clear that the right of first discovery had to be backed up by actual occupancy of the land.

After the Nootka Sound Conventions, Spain realized the interior had to be mapped in order to guard against intrusion into their silver mines region, and a chain of forts needed to be established to reinforce their claims to the Upper Missouri. It was feared that Britain and the United States might find an easy access route to the Spanish silver mines in New Mexico when they explored the Upper Missouri.316

The “Commercial Company for Discovery of the Nations of the Upper Missouri” was formed in 1794 under the direction of a wealthy St. Louis merchant, Jacques Clamorgan. The first expedition of ten men in a pirogue, led by Jean Baptiste Trudeau, ended in failure, having been robbed of their cargo by Indians. Another expedition sent out to aid Trudeau was also robbed. The two expeditions cost the company a total of $104,000. To encourage another effort, King Carlos IV of Spain offered a reward of $3,000 to the first Spanish subject to reach the Pacific by travel on the Missouri, and to pay the salaries of up to 100 men to guard the forts to be established on the Upper Missouri.317

The Missouri Company sent out a third expedition led by James Mackay in 1795. Mackay was a Scotch trader who had become a Spanish citizen. He was accompanied by John Evans, a young Welshman, whose passage to America had been paid by a radical Welsh society seeking to determine whether the Mandan Indians were the “Welsh Indians” of legend.

In 1792, Zenon Trudeau, Lieutenant-Governor of Upper Louisiana, wrote to his superior, Baron De Carondelet, Governor of Louisiana and West Florida, that a Frenchman, Jacques D’Eglise, had gone up the Missouri to trade in 1790:

… and although the commandant has forbidden all trading with the nations we know, he has dared to make his way in his hunting more than eight hundred leagues up the Missouri. There he found eight villages of a nation about which there was some knowledge under the name of Mandan, but to which no one had ever gone in this direction and by this river. All were provided with English arms. A Frenchman [Menard] … told de la Iglesia that the Mandans trade directly with the English. This nation received the said man, dela Iglesia, well and welcomed him. They [Mandans] are white like Europeans, much more civilized than any other Indians, and always live in tribes fortified against the numerous nations of Ciux [Sioux] with whom they are perpetually at war. It seems that these Mandans also have communications with the Spaniards, or with nations that know them, because they have saddles and bridles in the Mexican style for their horses, as well as other articles which this same de la Iglesia saw.318

John Evans came from Wales in October, 1792 to discover whether the Mandan Indians were the Welsh Indians of legend. He was 22 years old. While spending a few months in Baltimore and Philadelphia, he initially planned to travel through British Canada to the Mandan villages, which were located in present day North Dakota on the Missouri River.319

Changing his mind, he made a fateful decision to go to St. Louis in Spanish territory and travel on the Missouri River to reach the Mandan. While enroute to St. Louis, he stopped at Cincinnati and met General Wilkinson who advised him to go to New Madrid, where George Morgan had established an American colony in Spanish territory, rather than attempt to enter St. Louis.320

Evans arrived in New Madrid in the spring of 1793. At New Madrid, he took an oath of allegiance to the Spanish government. Stricken with malarial fevers, he was cared for by a Welsh family in New Madrid, and then by a fellow countryman in Kaskasia, Illinois, John Rice Jones, who introduced him to William Arundel, a court clerk and merchant in Cahokia, Illinois. Evans stayed with Arundel during his months in Illinois territory.

But around Christmas, 1794 he crossed over to St. Louis, having learned about James Mackay’s proposed expedition to the Upper Missouri. Evans realized he was taking a great risk, and wrote:

Now or never as I thought, it was my time to make application, so I went over the Mississippi. I thought within myself that it was rather a ridiculous busyness as it was a Critical time on the Spanish side on account of the report of Clark’s armie [George Rogers Clark’s French army in Kentucky] and I not able to speak one word with anybody, they speaking French. However, I went and was taken for a Spy, Imprisoned, loaded with iron and put in the Stoks besides, in the dead of winter. Here I suffered very much for several days till my friends from the American side came and proved to the Contrary and I was released.321

Evans biographer, Gwynn A. Williams, a Welsh historian, writes:

It was members of Wilkinson’s Conspiracy who got John Evans out of trouble in his early days in Spanish St. Louis …322

After James Mackay arrived in St. Louis in the summer of 1795 he hired Evans as his second in command and field operator. It appears that John Evans was a Freemason, or became a Freemason during his stay with William Arundel in Cahokia. Before his departure, Arundel wrote to Evans on August 28th, 1795:

Your intended journey will separate us for a long time, but altho’ at a Distance we may find ways and means of communicating and giving intelligence one to the other. Which I am in hope will always be in your memory. My Level & your Square must strike the necessary Ballance and Best Rules in the World be the guide among friends.323

John Evans had started out on a mission sponsored by a Welsh radical society to discover whether the white-skinned Mandans were the “Welsh Indians” of legend. It had been a subject of general interest for centuries, but it was also of enormous geopolitical significance for Britain, Spain and the United States. When Evans abandoned his original goal and joined the Missouri Company’s expedition to the Pacific, his silence on the question of Welsh Indians was effectively bought by the Spanish government.

The Welsh Indians were thought to be descendants of Prince Madoc of Wales and his men who visited Mobile Bay in 1170. After returning to Wales, they made a second voyage from which they never returned.324 If a Welsh prince and his men had discovered the New World in 1170, and through the centuries their descendants had become “White Indians,” then the Spanish right of first discovery, based on Columbus’s voyage of 1492, was no longer valid.

In the 1580’s, during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, the queen’s advisor John Dee had argued for the priority of British claims to the New World based on the story of Prince Madoc. Now in 1795, the poet laureate of England Robert Southey was writing an epic poem, Madoc.325 Whatever the truth of the matter, it was in the best interests of both Spain and the United States to deny the existence of Welsh Indians in order to discredit any British claim to the right of first discovery. For Welsh radicals, however, the idea of Welsh Indians had inspired an “America fever” with the goal of planting a Welsh colony in America and preaching the gospel to Indians.326

Evans’s mission had changed since joining the Missouri Company. After they wintered on the Missouri River, he was going to lead a detachment across the Rocky Mountains to find a navigable water route to the Pacific Ocean. The Mackay-Evans expedition consisted of 32 men in four pirogues carrying merchandise worth $50,000. One pirogue was loaded with merchandise for the Arikara. Another had merchandise for “buying their way” past the Sioux. A third was intended for the Mandans and the fourth was for the Indians of the Far West. The expedition was supposed to last for six years.

At the mouth of the Platte River, Mackay left a few men with merchandise and built a small trading post to obtain the goodwill of the Otoe Indians. Near the Omaha village of Chief Blackbird he built a stockaded trading post, Fort Charles, named for the Spanish king. While at Fort Charles, Mackay introduced the seeds of the watermelon, musk melon and other vegetables to the Omaha, which “succeeded very well.” In 1804, the Otoe chiefs would bring a gift of “Water Millions” to the council Lewis and Clark held with the Otoe at Council Bluffs. The watermelons most likely originated from Mackay’s initial gift of seeds to the Omaha.327

The problem in ascending the river was that the tribes wanted to keep all the merchandise for themselves, and prevent tribes living further up the river from receiving any merchandise. British traders—illegally operating in Spanish territory and wanting to keep the trade for themselves—encouraged the tribes to rob and plunder the traders from St. Louis.

Evans wrote about his first attempt to travel to the Pacific Coast, when his party was discovered by the Sioux in the vicinity of the White River in South Dakota—

In February 1796 started on my voyage to the West but at a distance of 300 miles from the Mahas [Omahas] was discovered by the Enemy the Sioux and obliged to retreat and return to the Mahas.328

Mackay wrote to Evans on February 19, 1796 that if he found a suitable river route to the west that was lower down the Missouri than the Mandan villages, he should take that route.329 But when Evans set off for the Pacific for the second time in June, he was instructed to visit the Mandan villages in North Dakota and take possession of them for the Spanish government.330

Mackay gave John Evans instructions for his journey to the Pacific that were remarkably similar to the instructions that Jefferson would give to Lewis in 1803. He was to keep journals noting the latitude, longitude, weather, winds, minerals, vegetables, plants, animals and provide detailed information about Indian tribes. He was to take possession of all the land he traveled in the names of King Charles IV and the Missouri Company by carving both of their names and the day, month, and year in large letters on stones or trees near river junctions.331 Mackay commanded him to—

Reveal your Plans & projects to no one whatever, not even to Mr. Truteau except what is necessary to forward your expedition & your information … you will at all events try to see the white people on the coast if it should answer no other purpose than that of corresponding by letters it will be of great service as it will open a way for a further discovery.332

Evans set off on his voyage to the Pacific on June 8th, 1796, having received “the necessary Instructions, as well as men, Provisions, and Merchandizes” from Mackay. When his detachment arrived at the Arikara Village on August 8th, they were forced to surrender most of their merchandise before they were allowed to continue.

When they arrived at the Mandan Village on September 23rd, the British traders were not at the village. Evans gave the Mandan chiefs flags and medals and hoisted a Spanish flag over the stockaded North West Company trading post, renaming it “Fort Mackay.” The trading post belonged to René Jessaume, a French trader employed by the British North West Company.

On October 8th some North West traders returned to the village, but within days Evans had forced them to leave, sending them back to their headquarters with a document provided by Mackay. It was a declaration—

“forbidding all strangers whatever to enter any part of his Catholic Majesty’s Dominions in this Quarter under any pretext whatever.”

On March 13, 1797, Evans received an answer. Jesseaume arrived with several engagés and merchandise to distribute as gifts to the Mandans in order to counteract the Spanish takeover. Jessaume had an Indian wife and children at the village, and it was his trading post that Evans was occupying. Evans reported that Jessaume urged the Indians:

… to enter into my house under the Mask of Friendship, then to kill me and my men and pillage my property.

Friendly chiefs intervened and guarded Evans and his men. But Evans reported that some days later:

Jussom came to my house with a number of his Men, and seizing the moment that my Back was turned to him, tried to discharge a Pistol at my head loaded with Deer Shot but my Interpreter having perceived his design hindered the Execution—the Indians immediately dragged him out of my house and would have killed him, had I not prevented them—this man having refused me Satisfaction for all the Insults he had given me.

Evans summed up what he had learned about the British traders among the Mandan, writing that they intended—

… to spare no trouble or Expence to maintain a Fort at the Mandaine Village. Not that they see the last appearance of a Benefit with the Mandanes, but carry their views further, they wished to open a trade by the Missouri with the Nations who inhabit the Rocky Mountains, a Trade, that at this Moment is Supposed to the best of the Continent of America.333

Mackay and Evans returned to St. Louis in the summer of 1797 due to lack of merchandise. Despite their planning, they had been forced to give up almost all of their merchandise to the Indian tribes they encountered before Evans reached the Mandan villages. When Mackay was at Fort Charles he may have gone up north to meet with Evans, because historian Abraham Nasatir writes:

Mackay himself says that he explored up to the Mandan; however this may be, he was back in St. Louis in May, 1797.334

When he returned to St Louis in May, Mackay was said to have “definite information” that Evans was on his way to the Rocky Mountains. However, Evans returned to St. Louis by July 15th, reporting that his travel down river had taken 68 days.335

A lasting benefit of Mackay’s and Evans’s expedition was the map of 1800 river miles of the Missouri from St. Louis to the White River that Mackay produced from John Evans’s charts and journal entries, and from Mackay’s own travels. Mackay was a skilled cartographer and his map circulated widely. Lewis and Clark carried a copy of the map and relied on it during their travels. It was the best map of the region until William Clark’s map replaced it in 1810.336

James Mackay was rewarded by the Spanish government, being appointed commandant of St. Charles and St. André, a district west of St. Charles. He also received several large land grants totalling about 46,000 acres (72 square miles).337 In Mackay’s report to the Spanish government he claimed exclusive credit for Evans’s discoveries, writing:

I also found means to drive the English out of His Majesty’s Territories & took possession of a Fort which they built at the mandan nation … I also took a Chart of the Missouri from its mouth to the wanutaries nation, which following the windings of the river is little short of 1800 miles.338

On July 15, 1797, John Evans wrote to Samuel Jones, his Welsh friend in Philadelphia, giving him a lengthy report of his activities since leaving Philadelphia in 1793. All he ever had to say in writing about the Welsh Indians was contained in a very brief statement at the end of the letter:

Thus having explored and charted the Missourie for 1800 miles and by Communications with the Indians this side of the Pacific Ocean from 35 to 49 Degrees of Latitude, I am able to inform you that there is no such People as the Welsh Indians, and you will be so kind as to satisfie my friends as to that doubtfull Question.339

In November, 1797 John Evans was appointed an assistant surveyor and assigned to the Cape Girardeau district, an American settlement in Spanish territory near the junction of the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers.340 On June 18, 1798 Evans wrote to Zenon Trudeau, Lieutenant Governor at St. Louis. Trudeau had told Evans to look out for a piece of land for himself and Evans had found 50–55 acres at a beautiful elevation, on a creek well suited for a mill. Evans then became philosophical about his life and wrote to Trudeau—

A reflection upon the shortness of life & the frowns of Delusive fortune—Convince me dayly of my duty to Live a retired life as soon as I can. For we can scarcly mount the stage of Life. Before we ought to prepare to leave it to make room for the next actors. In a solitary life a man is allowed a few moments to converse with himself—While in the crowd we are continualy Busy conversing with others untill unsensibly snatched away by death.

He reported he had heard General Wilkinson was expected shortly at Fort Massac on his way to either Natchez or Illinois and there were rumors America and France had declared war. 341

Welsh historian Gwyn A. Williams writes that an American, Jabez Halliday, who was researching Welsh Indians in 1803, said he had known John Evans and that—

In his cups, Halliday alleged, Evans used to boast that he knew more about Welsh Indians than anyone would ever know because he had been paid to keep his mouth shut. In any case, time and distance would soon remove any trace of their Welsh ancestry.342

Evans was known to be an alcholic and a troubled young man after he returned from the expedition. Author Richard Deacon says that Evans was offered a down payment of “the equivalent of two thousand dollars in cash” by the Spanish officials.343

Gayoso, the Governor-General of Louisiana, wrote to the Spanish court in 1797 about the Mandan question—

It is in the interest of his Catholic Majesty that the reports of British Indians in the Mandan country be denied once and for all.344

By May, 1799, John Evans had come to live as a guest in Governor Gayoso’s household in New Orleans. He would die there by the end of the month. In June, General Wilkinson came to stay with Gayoso on his way to the east coast. Wilkinson and Gayoso were close friends. Wilkinson’s wife Ann was living in Gayoso’s mansion in Natchez while the general traveled to New York to confer with Alexander Hamilton about plans for a cantonment on the Ohio.

The known dates are very close in time—within three weeks of each other. Wilkinson wrote to Andrew Ellicott from Gayoso’s home in New Orleans on June 12, 1799.345 Gayoso wrote to Mackay about John Evans on May 20, 1799:

Poor Evans is very ill; between us I have perceived that he deranged himself when out of my sight, but I have perceived it too late; the strength of liquor has deranged his head; he has been out of his senses for several days, but with care he is doing better, and I hope he will get well enough to send him to his own country.346

John Evans would die by the end of the month of May, according to James Mackay, who described Evans in words almost identical to the words Thomas Jefferson would use in describing Meriwether Lewis after his death in 1809:

Mr. Evans was a virtuous young man of promising talents, undaunted courage and perserverance.347

A young adventurer from Wales of “undaunted courage and perserverance,”arrived in America full of dreams about a 12th century Welsh prince and Welsh Indians. He wanted to visit the Mandans and didn’t care whether he traveled through British or Spanish territory. He obviously didn’t understand the geopolitical significance of his mission, or the danger he was placing himself in by joining a Spanish expedition. The only explanation for why Spanish authorities allowed Evans to become part of Mackay’s expedition is that a Welsh investigator could report “there is no such people as the Welsh Indians,” and, as Gayosoa wrote, the British claim to the right of first discovery would be “denied once and for all.”

When did Evans realize he could never talk about what he had learned at the Mandan villages or share his opinions? It was probably after he returned to St. Louis and met with Spanish authorities. He couldn’t talk about it—not because he was paid to keep silent, but because his silence might keep him alive. Unfortunately, death was the only way to ensure he wouldn’t talk. Evans’s letter to Trudeau is a plea to allow him to retire quietly to the countryside where he will lead a solitary life:

In a solitary life a man is allowed a few moments to converse with himself—While in the crowd we are continualy Busy conversing with others untill unsensibly snatched away by death.

Was John Evans another victim of an assassination organized by James Wilkinson? It seems quite possible. It would have been easy to add arsenic to his drinks. Arsenic was odorless and tasteless and in common use as a poison at the time. There were no means of detecting its presence in a body by forensic examination until the 1830’s.

As Evans said, life was short and “we ought to prepare to leave it to make room for the next actors.” Lewis and Clark would make use of Evans’s discoveries on their expedition to the Pacific Coast in 1803–1806; they would also spend a winter at the Mandan villages, and they would be silent on the question of Welsh Indians.

Thomas Jefferson was fascinated by American geography and western expansion—subjects on which his father, Peter Jefferson, had been a leading authority. His father was a surveyor and partner in the Loyal Land Company, which in 1748 received a grant of 800,000 acres of land in Kentucky from the Virginia House of Burgesses. In 1751, Peter Jefferson collaborated with Joshua Fry in publishing a famous map of Virginia based on actual land surveys. The Loyal Land Company even planned to undertake an expedition to the Pacific in 1753, but the project was halted because of the coming war between France and Britain for control of the North American continent, the “French and Indian War” of 1754–63. All of his childhood, Thomas Jefferson was surrounded by maps and plans for western expansion.

Fifty years after Peter Jefferson and his partners planned an expedition to the Pacific, President Thomas Jefferson was going to make it happen. But at the same time, the United States was facing a potential French invasion of the Mississippi Valley which would lead to all-out war with France.

Jefferson was warned by Robert Livingston, the American minister to France, in December, 1801 that Napoleon was planning to invade Louisiana. In cipher, Livingston wrote:

12,000 of the men sent to st domingo are destined for louisianna in case tousaint makes no opposition.348

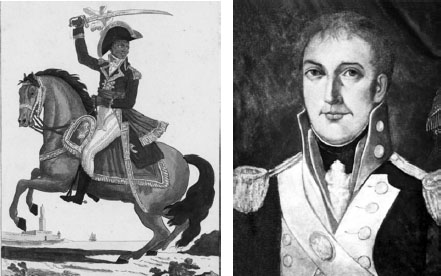

Toussaint L’Ouveture, called the “Black Napoleon,” was the leader of the slave revolution in Saint Domingue. Slaves, free blacks and mulattoes, inspired by the French Revolution, had been fighting for their independence since 1791. It became the only successful slave revolt in history when in January, 1804 Saint Domingue became the nation of Haiti.

During the years of 1801–1803, Napoleon was determined to win back control of France’s prize colony. Though only 1/3 of the island of Hispaniola (which Saint Domingue shared with the Spanish colony of Santo Domingo), it had produced 40% of the wealth of the French colonial empire before its slave revolution. The wealth came from the production of sugar and coffee through slave labor. Napoleon was determined to regain control of Saint Domingue and then to proceed onto New Orleans and Louisiana. Louisiana would serve as a source of agricultural products for the French sugar islands in the Caribbean, whose lands were devoted to more valuable crops.

Toussaint L’Ouveture, leader of the Saint Domingue revolution, and William Claiborne, Governor of Mississippi Territory in 1801–03. (Wikimedia Commons)

In February, 1802 France sent an invasion force of 46 ships carrying 40,000 troops to Saint Domingue. More ships and troops would follow. Four fifths of Napoleon’s army perished in fighting the rebels and from yellow fever. Ultimately, as many as 60,000 French soldiers died in the attempt to retake Saint Domingue in 1802–03.349

France had acquired Louisiana from Spain in the secret Treaty of San Ildefonso signed on October 1, 1800. The French acquisition of Louisiana was rumored when Jefferson became president in March, 1801. He began at once to establish a state of military preparedness on the southwestern frontier. Jefferson appointed William C. C. Claiborne Governor of Mississippi Territory in 1801. Claiborne would go on to serve as Governor of the Territory of New Orleans from 1804–1812, and then the State of Louisiana from 1812–16. For 16 years he played a vital role in securing the New Orleans area. He was the brother of Meriwether Lewis’s friend, Ferdinand Claiborne.

Jefferson’s appointment of Claiborne ensured that the New Orleans area was preparing for military action.350 In 1801, General Wilkinson and Major Williams made plans for a military road in the Lake Erie area to defend against a British invasion, and then conducted training exercises at Cantonment Wilkinsonville on the Ohio River. After that, General Wilkinson spent two years in the Southwest negotiating Indian treaties and building military roads and forts, while Major Williams founded the West Point Military Academy.

Jefferson would write in the summer of 1803, after the Louisiana Purchase was accomplished:

These grumblers too are very uneasy lest the administration should share some little credit for the acquisition, the whole of which they subscribe to the accident of war. They would be cruelly mortified could they see our files from April 1801, the first organization of the administration, but more especially from April, 1802. They would see that tho’ we could not say when war would arise, yet we said with energy what would take place when it should arise.351

These were the years that Lewis was serving as his confidential aide. Preparations for war in the Mississippi Valley must have occupied much of their attention.

The American Ambassador to France, Robert Livingston, arrived in Paris in December, 1801. His departure for France had been delayed waiting for congress to ratify the terms of ending the Quasi-War with France. In April, 1802 Jefferson wrote to Livingston:

The cession of Louisiana & the Floridas by Spain to France works most sorely on the US….it compleatly reverses all the political relations of the US. and will form a new epoch in our political course…. there is on the globe one single spot, the possessor of which is our natural & habitual enemy. It is New Orleans, through which the produce of three eighths of our territory must pass to market, and from its fertility will ere long yield more than half of our whole produce and contain more than half of our inhabitants… the day that France takes possession of N. Orleans … from that moment we must marry outselves to the British fleet & nation.352

The next month in May, Secretary of State James Madison wrote to Livingston asking him to inquire if the cession of Spanish territory to France included New Orleans and the two Floridas. If they were included, then the United States wanted to know, what would be the price to purchase them?353

In July, 1802 Napoleon wrote to his Minister of Marine and Colonies, Denis Decres:

My intention, Citizen Minister, is that we take possession of Louisiana with the shortest possible delay, that this expedition be organized in the greatest secrecy, and that it have the appearance of being directed at St. Domingo….I should also like to have made for me a map of the coast from St. Augustine Florida to Mexico …354

It wasn’t until later in the year, however, on October 18, 1802, that Spain finally completed the cession of Louisiana to France. This procrastination cost France dearly, as Napoleon allowed it to delay his invasion of Louisiana.

At the very same time in October, a Spanish administrator in New Orleans closed the port of New Orleans to Americans, inciting a storm of outrage and demands for war from both westerners and Federalists. It was assumed that France was behind the order. In actuality, it was Carlos IV, the king of Spain, who ordered it in response to American smuggling of goods and their disregard for paying custom duties.355

Over the winter of 1802–03, Ambassador Livingston entered into talks with Joseph Bonaparte, Napoleon’s brother. The United States was seeking to acquire New Orleans and at least West Florida, if not both Floridas. In January, Napoleon—upon learning of the death from yellow fever of his brother-in-law, General Charles Le Clerc, commander of the invasion forces—had exploded, “Damn sugar, damn coffee, damn colonies!”356

In March 1803, a colonial adminstrator, Pierre de Laussat, arrived in New Orleans to take possession of Louisiana for France, expecting that an initial military force of 3,000 troops would soon arrive. The French ships on the coast of Holland had been icebound over the winter. When the weather improved, the British set up a naval blockade of the Dutch coast.

By April 10th, Napoleon had decided to sell all of Louisiana to the United States. James Monroe arrived in Paris on April 12, as a special envoy of President Jefferson. War between France and England was about to resume, and Napoleon decided to cut his losses in the Caribbean and raise money for the coming war. Monroe’s arrival coincided with news of Federalist demands for a war to take possession of New Orleans due to the closure of the Port of New Orleans. Monroe’s instructions were to make an alliance with Great Britain if he couldn’t receive satisfaction in France.357

The stage was set, and on April 11th, before Monroe arrived, Talleyrand asked Livingston if the United States “wished to have the whole of Louisiana.” On April 12th, Napoleon sent orders to stop the sailing of ships to Louisiana. The order reached the fleet two days before they were to leave for New Orleans.358 The treaty signed on May 2, 1803 was for the sale of Louisiana for $15 million. Adjusted for claims for American losses during the Quasi-War, the cost was $11.25 million. The exact amount of territory gained in this sale was unclear. It was defined as:

the Same extent that it now has in the hand of Spain & that it had when France possessed it.359

The Louisiana Purchase is now understood to have encompassed 828,000 square miles, acquired at a cost of less than three cents an acre. The United States had been willing to pay up to $10 million for New Orleans and West Florida. Whatever the size and extent of its boundaries, the purchase approximately doubled the size of the American nation. When Livingston asked Talleyrand if he could clarify the boundaries, he replied:

I can give you no direction. You have made a noble bargain for yourselves and I suppose you will make the most of it.360

In the summer of 1802 Jefferson and Lewis had begun making plans for Lewis to lead an expedition to the Pacific Coast. The expedition was fundamentally a military reconnaisance mission and a recognition of the need for haste in reinforcing the United States’ claim to the Pacific Northwest. In 1802 they had no way of anticipating that Napoleon would end up selling Louisiana to the United States.

On January 18, 1803, Meriwether Lewis acted as Jefferson’s courier in delivering a confidential message from the president to the senate and house of representatives. The message proposed a voyage of discovery, a “literary” expedition to explore the Missouri River in the interests of commerce and science, which would provide no offense to the nation [Spain] claiming possession of the territory. It would cost $2,500.

The message emphasized the great quantity of furs and peltries obtained by the British in Canada from the Indians on the Upper Missouri, and observed American traders would have a competitive advantage due to moderate climate and easy access. Jefferson wrote:

An intelligent officer with ten or twelve chosen men, fit for the enterprize and willing to undertake it, taken from our posts, where they may be spared without inconvenenience might explore the whole line, even to the Western Ocean.

Harpers Ferry, 1803. Harpers Ferry National Historical Park www.nps.gov/hafe/meriwether-lewis.htm

Jefferson attempted to keep the destination of the expedition secret, saying its mission was to explore the Mississippi. He had already informed Ambassador Irujo of the true destination, requesting a passport from the Spanish government. The Spanish passport was not forthcoming, but French and British officials provided passports.

By February Jefferson was writing to fellow members of the American Philosophical Society requesting their aid in training Captain Lewis, who would soon be coming to Philadelphia. He asked them to prepare notes for Lewis regarding inquiries he should pursue. To them, he revealed that the mission was to explore the Missouri and find a navigable water route to the Pacific Ocean. He wrote:

Capt. Lewis is brave, prudent, habituated to the woods, & familiar with Indian manners & character. He is not regularly educated, but he possesses a great mass of accurate observations on all the subjects of nature which present themselves here, & will therefore readily select those only in his new route which shall be new.361

Andrew Ellicott’s House, Lancaster, Pennsylvania (Wikimedia Commons)

Lewis first went to Harpers Ferry, the U. S. Armory and Arsenal in West Virginia at the confluence of the Potomac and Shenandoah Rivers. He arrived there on March 16, 1803, expecting to spend a week. Instead, he spent a month working on a design for an iron boat frame which could be carried over the Rocky Mountains.The boat, called The Experiment, was built in sections and would weigh 176 pounds and carry a load of 8,000 pounds after being assembled. In addition Lewis placed orders for 15 rifles, extra gun parts, gunsmith repair tools, tomahawks and knives.362

He arrived at Lancaster, Pennsylvania on April 20th to begin training with Andrew Ellicott. The surveyor taught him how to make the astronomical observations used in determining the latitude and longitude of locations. When he arrived in Philadelphia in early May, mathematician Robert Patterson tutored him in the required mathematics, and he bought the scientific instruments needed for the observations.

At Philadelphia, Lewis met with Dr. Benjamin Rush, who advised him on medical matters. Dr. Rush’s famous “bilious pills” for constipation and headaches were nicknamed “Rush’s Thunderbolts.” Lewis obtained more than thirty kinds of drugs for the expedition, including opium and laudanum (a diluted form of opium), and an assortment of medical instruments. He was knowledgeable about herbal remedies, having been trained by his mother.

He met with Dr. Benjamin Smith Barton who tutored him on the technical language of the natural sciences, purchased his newly-published Elements of Botany, and borrowed a book, du Pratz’s History of Louisiana. He also visited the author of an anatomy book, Dr. Caspar Wistar, to discuss fossils.

Much of his time was spent shopping and placing orders with the Purveyor of Public Supplies, Israel Whelan, to whom he gave a draft of $1,000. Army goods were obtained from the Schuykill Armory. Lewis estimated the supplies and equipment would weigh 3,500 pounds and he hired a wagon with five horses and a driver to take the goods to Pittsburgh.

After spending a month in Philadelphia, Lewis returned to the President’s House in early June.363 It was decided then that Lewis needed a partner. Jefferson had been writing instructions in April. It was a question of handling the responsibilities of map making and scientific observations while on a dangerous expedition over unknown territory. A second leader would also ensure a backup plan in case Lewis lost his life.

On June 19th, Lewis wrote a long letter to William Clark at the Falls of the Ohio, describing his plans for the expedition:

… it is to descend the Ohio in a keeled boat of about ten tons burthen, from Pittsburgh to its mouth, then up the Mississippi to the mouth of the Missourie, and up that river as far as its navigation is practicable with a boat of this discription, there to prepare canoes of bark or raw-hides, and proceed to it’s source, and if practicable pass over to the waters of the Columbia or Origan river and by descending it, reach the Western Ocean; the mouth of this river lies about one hundred and forty miles South of Nootka Sound; at which place there is a considerable European Tradeing establishment and from which it will be easy to obtain a passage to the United States by way of the East-Indies in some of the tradeing vessels that visit Nootka Sound annually, provided it should be thought more expedient to do so, than to return by the rout I had pursued in my outward bound journey.

… If therefore there is anything under those circumstances, in this enterprise, which would induce you to participate with me in it’s fatiegues, it’s dangers and it’s honors, believe me there is no man on earth with whom I should feel equal pleasure in sharing them as with yourself; I make this communication to you with the privity of the President, who expresses an anxious wish that you would consent to join me in this enterprise; he has authorized me to say that in the event of your accepting this proposition he will grant you a Captain’s commission, which of course will intitle you to the pay and emolulents of that office….your situation if joined with me in this mission will in all respects be precisely such as my own.364

William Clark by St. Memin, and later as Governor of Missouri Territory ( Collection of State Capitol of Missouri)

It was a generous offer. The expedition to the Pacific has become known as the “Lewis and Clark Expedition” because of it, but in truth it was an expedition under the command of Captain Meriwether Lewis, who bore the responsibility for it from beginning to end. It was not in President Jefferson’s power to grant a captain’s commission to William Clark. The War Office authorized a second lieutenant’s commission, but members of the expedition were told he was a captain.

Jefferson instructions had been sent to Lewis and cabinet members for their comments in April. His instructions assumed Lewis would need a French passport to travel through Louisiana, and a British passport to deal with British traders.The Spanish passport had been refused on the grounds that the Upper Missouri was Spanish territory and not part of the cession of Louisiana to France.

The expedition would consist of 10–12 soldiers who would volunteer for the assignment and be recruited from western army posts. However, Lewis wrote to Clark that he was looking for civilians and wanted him to find:

… some good hunters, stout, healthy, unmarried men, accustomed to the woods, and capable of bearing bodily fatigue in a pretty considerable degree…

The men would be told that it was an expedition to explore the Mississippi River to its source and that it would last about 18 months. Before they signed on they would be told the truth and Lewis expected that none would refuse. By 1805, when the expedition left Fort Mandan for the Pacific Coast, it had grown to 26 enlisted men in the army, Lewis and Clark, four civilians, a baby and a dog, but the instructions in 1803 were based on the original budget estimate of 10–12 soldiers.

One of the most important instructions was assigned to William Clark—making careful records, mile by mile, of the river courses and routes over land. He would use these measurements to create his famous map. It was an activity that required constant attention and note-taking, whether he did it himself or del egated the work. The crucial latitude-longitude readings would be handled by war office specialists after they returned.

Information about Indian tribes was needed—every kind of information. The natives were to be treated in “the most friendly & conciliatory manner” and told the U. S. wanted to engage in commerce with them in the fur trade. They were to record vocabularies in Indian languages.

They were to note soil, vegetation, animals, fossils, minerals, and climate. The dates of seasonal changes, when plants put forth or lost their flowers and leaves, fruits ripened, and the presence of birds and insects, were to be recorded. Anything new to the U. S. was especially important.

They were to be careful to not risk their lives, and to keep two duplicate sets of records. At least seven members of the expedition kept journals. Donald Jackson, who edited the Letters of Lewis and Clark, called them—

the writingest explorers of their time. They wrote constantly and abundantly, afloat and ashore, legibly and illegibly, and always with an urgent sense of purpose.365

On July 2nd, Lewis wrote to his mother that he would start on his journey to the “Western Country” on July 4th. It would take 15–18 months, and was “by no means dangerous” as the Indian tribes were “perfectly friendly to the United States.” He would be as safe as if he were to “remain at home for the same length of time” and he hoped she would not “indulge in any anxiety for my safety.”366

However, on the evening of July 3rd, the most astonishing news reached the capitol—France had sold the entire territory of Louisiana to the United States! Lewis stayed in town one more day for what must have been one of most memorable Fourth of July celebrations in American history.

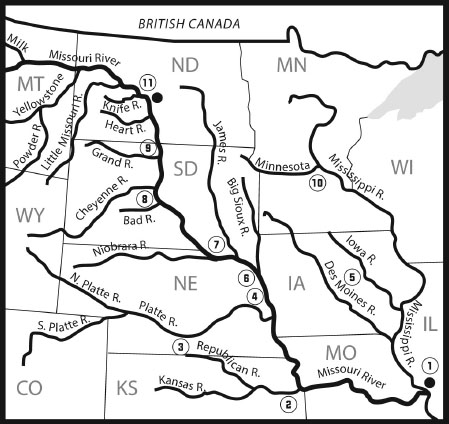

Expedition’s Winter Camps:

Wood River Camp (Dec. 12, 1803-May 14, 1804)

Wood River Camp (Dec. 12, 1803-May 14, 1804)

Fort Mandan (Nov. 2, 1804-April 7, 1805)

Fort Mandan (Nov. 2, 1804-April 7, 1805)

1. Wood River Camp and St. Louis

2. Kansas Indians

3. Pawnee village that stopped Spanish soldiers

4. Otoe and Missouria village at Platte & Elkhorn Rivers

5. Ioway Indians

6. Omaha Indians

7. Yankton Sioux

8. Teton Sioux (Brulé Sioux)

9. Arikara villages

10. Santee Sioux

11. Fort Mandan and Mandan & Hidatsa villages