Meriwether Lewis set off for the Pacific Coast on July 5th, 1803. He would return to the President’s House on December 28th, 1806. Against all odds he had reached the mouth of the Columbia River on the Pacific Ocean, reinforcing the U.S. claim to the Pacific Northwest under the Doctrine of Discovery. It would establish the United States as a continental nation from “sea to shining sea.”

History is a twice told tale and every generation tells its own tale. In honor of the 200th anniversary of the expedition in 2003–2006, its peaceful nature and contact with Indian nations was emphasized. The story of Lewis’s supposed suicide in 1809 was presented as a fact, which distorted all interpretations of his character. That his death was immediately labeled a suicide has unintentially colored the assessment of who he was and what he accomplished for over two centuries.

He celebrated his 29th birthday at Pittsburgh on August 18, 1803, while he was living in the officer quarters at Fort Fayette, (Fort Lafayette) waiting for his boat to be built by a drunken contractor. Lewis himself had arrived at Pittsburgh on July 15th, only ten days after leaving the capitol. If William Clark was unable to go, Lieutenant Moses Hooke, commander of Fort Fayette, was going to be his replacement. Hooke would serve as second in command, not as co-commander. But by the 29th of July, Lewis had received a reply from Clark:

I will cheerfully join you in an “official Charrector” as mentioned in your letter, and partake of the dangers, difficulties, and fatigues, and I anticipate the honors & rewards of the re sult of such an enterprise, should we be successful in accomplishing it. This is an undertaking fraited with many difeculties, but My friend I do assure you that no man lives whith whome I would perfur to undertake Such a Trip &c. as yourself, and I shall arrange my matters as well as I can against your arrival here.367

On July 22nd, Lewis wrote to Jefferson that the goods had safely arrived from Harpers Ferry and the army volunteers who would take the boat down the Ohio had arrived from Carlisle. The boat would be ready by August 5th. The water on the Ohio River was exceedingly low and getting lower. No matter how low the river got he was—

determined to go forward though I should not be able to make a greater distance than a mile pr. day.368

By the time he wrote to William Clark on August 3rd, he was going to do it, even if he could make no more than a “boat’s length pr. day.” He wrote the boat would be ready by mid August and he would be at the Falls by the end of the month.

He cautioned Clark he was pleased to hear he had engaged some men for the expedition, but they should be told it was conditional on Lewis’s approval. He was “well pleased” that Clark had rejected the young gentlemen who were applying, as “they will not answer our purposes.” They needed hunters, who were willing to share in the general duties of the party.369

Lewis had successfully managed things so far. The purveyor’s summary of his purchases for the journey listed the following categories and took many pages to describe in detail—mathematical instruments; arms, ammunition and accoutrements; medicine &c; clothing; provisions &c; Indian presents; and camp equipage. Altogether his purchases totaled $2,160.14, and were based on the estimate of 12–15 soldiers making up the party.370

The expedition was expanding. His original plan had been to use volunteers from Southwest Point, an army post in Tennessee, and to purchase a boat at Nashville. However, Lewis learned there were not enough good men stationed at Southwest Point for his purposes and no boat was available at Nashville. Building a boat at Pittsburgh was a substitute plan. The use of recruits from Carlisle to take the boat down the Ohio was also improvised. The soldiers would be traveling to their first assignment at Fort Adams in Mississippi Territory, and would leave the boat once it reached Fort Massac near the Mississippi River.371

A portrait of the original breed of Newfoundland dogs, circa 1790.

On July 2nd, Secretary of War Henry Dearborn authorized the commander at Kaskaskia in Illinois Territory to supply eight men and a sergeant who understood how to row a boat and to provide the best boat at the post to accompany Lewis up the Missouri. The soldiers were expected to return to Illinois before the river iced over.372

Dearborn also instructed Captain Lewis that he should have no more than 12 non-commissioned officers and privates under his command. Another officer (Clark) and a hired interpreter, would bring the total to 15.373 Lewis interpreted these orders to mean that he could hire as many civilians as he needed when he wrote to Clark.

Lewis made a decision that was important for the safety of the party, and certainly for its morale. He purchased a Newfoundland dog for $20 at Pittsburgh which he named Seaman. The big dogs originally came from Newfoundland and were famous for their swimming ability. Newfoundlands were working dogs used by fishermen to retrieve lines and nets of fish. They had short, thick coats and were very strong.374

Keelboat at Lewis and Clark State Park, Onawa, Iowa. (Photo by Kira Gale)

Finally the boat was completed. Lewis sent two wagons loaded with goods down to Wheeling on the Virginia side of the Ohio River. The Ohio was the lowest it had ever been in the memory of the “oldest settler in this country.” The boat had to be unloaded and lifted by hand over bars of stones and driftwood in the river, or dragged by horses and oxen over the bars. The water level at many bars was six inches or less. Lewis left Pittsburgh on August 31, 1803. When he reached Wheeling on September 8th, he wrote Jefferson that he had been “most shamefully detained by the unpardonable negligence of my boat-builder,” and that he had averaged about 12 miles a day to Wheeling, but some days it was 5 miles or less.375

At Wheeling he purchased the red pirogue—a large row boat manned by seven oars and equipped with two sails—to haul some of the goods brought by the wagons. The water level was deeper from Wheeling on down the Ohio to its mouth on the Mississippi River.

One of Lewis’s prize possessions was his newly purchased airgun. When the boat left Pittsburgh he stopped at Brunot’s Island, five miles down river, to say goodbye to his fellow Masons who had gathered to bid him farewell. He demonstrated the airgun, firing it seven times on one charge before giving it to a friend to try out. The friend accidentally shot a woman bystander, standing about 40 yards away. The .46 caliber (nearly half an inch) lead ball passed through her hat and cut her temple. She fell to the ground, bleeding. Lewis wrote in the first day’s entry in his journal:

… we were all in the greatest consternation supposed she was dead [but] by a minute she revived to our enespressable satisfaction, and by examination we found the wound by no means mortal or even dangerous; called the hands aboard and proceeded. & 376

The next account of the airgun comes from the journal of another traveler, Thomas Rodney, who was going down the Ohio to become a judge and land commissioner in Mississippi Territory. Rodney had traveled by horseback to Wheeling and was going by flatboat the rest of the way. On September 8th he wrote:

Visited Captain Lewess barge. He shewed us his air gun which fired 22 times at one charge…. It is a curious peice of workmanship not easily discribed and therefore I omit attempting it.377

Rodney did not actually witness the gun fire 22 times on one charge. Lewis was having trouble with the firing mechanism, but he could manage to fire it seven times on a charge. If you were 50 yards away, the airgun would appear to fire silently. Closer to the firing, a “whack” sound was heard. The gun was a Girandoni airgun, a military weapon made in Austria and was one of only one or two repeating airguns in the U. S.378

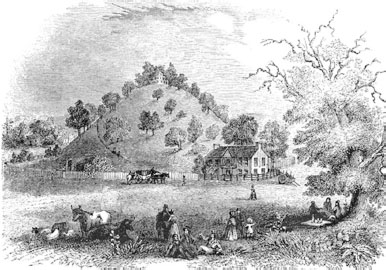

The Grave Creek Mound, from an 1847 engraving.379

After leaving Wheeling, Lewis visited the Grave Creek burial mound at Moundsville, West Virginia. He estimated the “remarkable mound of earth” to be 65 feet high, ending in a blunt point of 30 feet in diameter. He wrote:

near the summet of this mound grows a white oak tree whose girth is 13 ½ feet, from the aged appeance of this tree I think it’s age might resonably be calculated at 300 years.380

The Ohio Valley was covered with Indian burial mounds and ceremonial and astronomical observation earthworks, built by prehistoric Indians who moved countless tons of earth in constructing them. Lewis wrote that some brass beads found near two skeletons excavated from the site had been sent to Mr. Peale’s museum in Philadelphia. The Grave Creek Mound dates back to 250–150 B. C. and is now a National Historic Landmark.

Two days later he arrived at Marietta, Ohio, established by veterans of the American Revolution as the first settlement in Northwest Territory. Located at the junction of the Muskingum and Ohio Rivers, Marietta is the site of an ancient complex of platform mounds. There he visited with the postmaster, an “excalent republican,” and wrote another letter to Jefferson.

Seaman was having a great time, catching black squirrels who were swimming across the Ohio, from the west to the east shore. Lewis wrote the squirrels were fat and he found them “when fryed a pleasant food.”

Lewis passed Blennerhassett Island without comment in his journal. The island was the home of one of the largest mansions in the United States, built by a wealthy and eccentric Irish couple, Harmon and Margaret Blennerhassett, who emigrated to America in the 1790’s. Blennerhassett Island would become an important part of the Aaron Burr treason trial in 1807.

After Lewis reached Letart Falls on September 18th, he quit writing in his journal for almost two months. The Falls were near the bend of the Ohio, where the river heads west to join the Mississippi. During this time he visited Cincinnati and Big Bone Lick to collect bones for Jefferson, and then spent almost two weeks at the Falls of the Ohio.

When he reached Cincinnati on September 28th he wrote to Clark that he had conditionally engaged two young men. They were George Shannon and John Colter. Shannon would become the youngest member of expedition at age 16. Shannon is often said to have been 18 years old in 1803, but it seems more likely he was two years younger. Perhaps Lewis was remembering how disappointed he had been when he wasn’t allowed to join Michaux’s expedition at the age of 18.381

In his letter to Jefferson on October 3rd, Lewis described mastodon bones (which he called “mammoth” bones) that he examined in the collection of Dr. William Goforth of Cincinnati. He then went to Big Bone Lick, 17 miles southwest of Cincinnati, to collect bones for the president—which unfortunately were lost in a boat accident on their way to Monticello. Mastodons roamed North America until 10,000 to 11,000 years ago. The salt licks and a sulphur springs at Big Bone Lick had supplied salt and minerals to animals living in the Pleistocene era and for many years afterwards. The mastodons were the animals, the “American Incognitum,” which they hoped to find were still living in the unexplored regions of the West.

Lewis included some alarming news in his letter. He had decided to explore the country south of the Missouri on horseback over the winter, perhaps going by the route of the Kansas River to Sante Fe. He added that if Clark could be spared from other duties, he could explore the area in another direction. Jefferson wrote back to Lewis on November 16th—

We are strongly of the opinion here that you had better not enter the Missouri till the spring …. One thing however we are decided in: you must not take the winter excursion which you propose … Such an expedition will be more dangerous than the main expedition up the Missouri & would by an accident to you, hazard our main object, which since the acquisition of Louisiana interests every body in the highest degree….The object of your mission is single, the direct water communication from sea to sea formed by the bed of the Missouri & perhaps the Oregon [Columbia]. By having Mr. Clarke with you we consider the expedition double manned & therefore the less liable to failure, for which reason neither of you should be exposed to risques by going off of your line.382

Jefferson also advised him to spend the winter in Illinois Territory at Kaskaskia or Cahokia in order to avoid all danger of Spanish opposition. He gave Lewis the news that he expected congress would authorize $10–12,000 in additional funding for three more expeditions to explore the principal waters of the Mississippi and Missouri. Lewis received this letter after he arrived at Cahokia in December.

William Clark was waiting for Lewis when he reached the Falls of the Ohio on October 14th. The boat was piloted through the Falls on the 15th and moored at Mill Creek near George Rogers Clark’s home on Clark’s Point overlooking the falls. William had moved across the river from Louisville in March to live with his brother in Clarksville, Indiana. His brother’s home was a two room log cabin with an upstairs sleeping loft. Due to his brother’s financial entanglements, William owned the land adjacent to Mill Creek, and had entered into an agreement with the town trustees in March to build a boat canal and waterworks on the land.383

Lewis and the two Clark brothers must have immediately agreed that the seven men William Clark had recruited, and the two recruits with Lewis, needed to be enlisted in the army rather than hired as civilians. These became the expedition members known as “The Nine Young Men from Kentucky.” In addition, Clark informed Lewis he was bringing his slave York along on the journey, making it a total of ten men who joined at the Falls.

William Clark and the two Field brothers, Reuben and Joseph, have the date of August 1, 1803 for their army enlistments. Clark must have recruited them and secured their commitment very soon after receiving Lewis’s letter. At the end of the expedition, Lewis would recommend bonus pay for the Field brothers, describing them as—

… two of the most active and enterprising young men who accompanied us. It was their peculiar fate to have been engaged in all the most dangerous and difficult scenes of the voyage, in which they uniformly acquitted themselves with much honor.

The other men enlisted between October 15–20th. Charles Floyd and Nathaniel Pryor, who were cousins, were appointed sergeants by the captains after the expedition set out. Another of Clark’s recruits, John Shields, was praised by Lewis who wrote at the end of the expedition—

Nothing was more peculiarly useful to us, in various situations, than the skill and ingenuity of this man as an artist, in repairing our guns, accoutrements, &c.

Lewis had written to Clark that “much must depend upon the judicious scelection of our men” and of the seven men chosen by Clark five received special recognition. His ability to recruit the right men was essential to the expedition’s success. The other two men who joined the party were William Bratton and George Gibson who also became members of the permanent party. Bratton was a blacksmith and Gibson was a fiddle player among their other accomplishments. The expedition left the Falls on October 26th.

Lewis resumed writing in his journal on November 11, when they reached Fort Massac, where he hired the services of a civilian, George Drouillard (pronounced “Drewyer”), a sign language interpreter and hunter of mixed Shawnee and French Canadian descent. Lewis urged additional pay for “Drulyard” at the end of the expedition, writing—

A man of much merit; he has been peculiarly usefull from his knowledge of the common language of gesticulation, and his uncommon skill as a hunter and woodsman….It was his fate also to have encountered on various occasions, with either Captain Clark or myself, all of the most dangerous and trying scenes of the voyage, in which he uniformly acquited himself with honor.384

The soldiers who had manned the boat from Pittsburgh were dropped off at Fort Massac. They passed Wilkinsonville on November 14th with just a brief mention in Lewis’s journal. Lewis had been stricken with malarial fevers the day before, and Clark was ill with violent stomach and bowel pains from November 16th until reaching Kaskaskia on November 27th.

Seven of the soldiers who volunteered at Kaskaskia became members of the permanent party—John Collins, Patrick Gass, John Ordway, Peter Weiser, Joseph Whitehouse, Alexander Willard and Richard Windsor. The others were part of the military escort who brought the barge back to St. Louis. The white pirogue, the larger of the two rowboats with sails, was acquired at Kaskaskia.

Lewis left Kaskaskia on November 5th, traveling on horseback to Cahokia. There he met with postmaster John Hay and French fur trader and land speculator Nicholas Jarrot, who agreed to serve as translators at his meeting with the Spanish Lieutenant Governor of Louisiana, the Marqués Carlos Delassus in St. Louis. At the meeting, Lewis informed Delassus that twenty five men would be accompanying him on the expedition to the Pacific, and that Louisiana would soon be formally acquired by the United States. On December 9th, Delassus wrote to the military governor of Louisiana, the Marqués de Casa Calvo, and to Governor Juan Manuel de Salcedo, that—

Mr. Merryweather Lewis, Captain of the United States army and former secretary of the President of them has presented himself at this post….I should inform Your Excellencies that according to advices, I believe that his mission has no other object than to discover the Pacific Ocean, following the Missouri, and to make intelligent observations, because he has the reputation of being a very well educated man and of many talents.386

On November 30th in New Orleans, Casa de Calvo and Manuel Salcedo had presided over the transfer of Spanish Louisiana to France. Twenty days later, Pierre de Laussat—the bureaucrat sent by Napoleon to govern Louisiana after the planned invasion by the French army—unhappily presided over the peaceful surrender of Louisiana to the United States.

General Wilkinson was prepared to enforce the transfer of power from France to the U. S. with about 350 regular troops and volunteer militia who accompanied him to New Orleans. The general and the new Governor of Louisiana Territory, William Claiborne, were given the keys to the city at the ceremonies on December 20th and the American flag rose over the Cabildo and Place d’Armes on the city’s waterfront. The eight to ten thousand citizens of New Orleans—who almost all spoke French as their native language—were not happy. Most of their quarrels started over French or American style of dancing at public balls, and the songs and music played at them. Wilkinson, with the small number of troops under his command, managed to maintain order during this time of government and cultural transition.

In February, 1804, the general met in secret with Vincent Folch, Governor of Spanish Florida, and the Marqués de Casa Calvo, the newly appointed Spanish boundary commissioner. Casa de Calvo was in charge of determining the extent of the land Spain had ceded to France. Wilkinson wanted to resume his career as Agent Number 13 at a pay scale of $4,000 per year; to receive $20,000 in back pay; and to sell 16,000 barrels of flour in Havana. In return he would write a report, “Reflections on Louisiana.” After negotiations he was paid $12,000, which the general invested in sugar to be shipped to the east coast.

Over the next month Wilkinson wrote a long report, which Governor Folch translated into Spanish and sent under his own name to his superior in Cuba. The report urged that the Lewis and Clark expedition be arrested or forced to retire from the Upper Missouri country. On March 5th, Casa de Calvo and Manuel Salcedo wrote a letter to Salcedo’s brother, Nemesio Salcedo, Governor of Spanish Texas, advising him that it was “absolutely necessary for reasons of state” to carry out the arrest of Captain Merry Weather and his party.387

After writing his “Reflections,” Wilkinson rewrote it for an American audience and brought it to President Jefferson. This version described the country between the Mississippi and the Rio Grande and was accompanied by 28 maps made by the late Philip Nolan. Wilkinson did not provide any maps to the Spanish government. Essentially, his report on the western frontier served at least two purposes for the general, and he was paid handsomely for it by the Spanish government.388

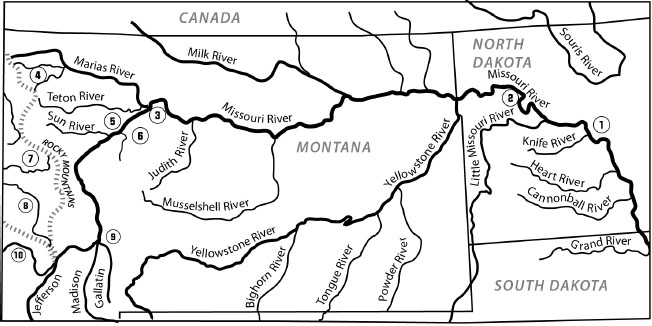

Wilkinson’s Spanish report explains why Lewis and Clark’s original mission—to find a direct water route from the Missouri to the Pacific Ocean—was expanded to include discovering the source of the Missouri. Finding the source of the Missouri River would establish America’s claim for the northern boundary of the Louisiana Purchase. The Spanish insisted the northern boundary was based on the boundary between French Louisiana and New Spain in the 1700’s, when the Arroyo Hondo (the Calcesieu River in today’s state of Louisiana) served as the boundary line between the two colonial empires. The United States’s position was that the Louisiana Purchase included the mouth of the Missouri River at St. Louis, and all of the land whose waters drained into the Missouri from its source in the western mountains.

Wilkinson’s report, signed by Folch, stated:

If anyone should doubt the dispositions of the American government with respect to the western boundaries of Louisiana it will be necessary to refer those incredulous ones to the doctrines uttered in full Congress and published in the ministerial gazettes of the city of Washington, and those of this capitol [Pensacola,West Florida]. To these proofs may be added the following interesting facts: that the president of the United States has commissioned his astronomer, who is at this very moment in the province of Louisiana, with the duty of determining by all practical investigations the relative positions of the mouth of the Rio Bravo or Rio Grande, and the source of the Missouri River; that, as an aid to this end, orders have been given to the presidents’s private secretary and the Infantry Captain Lewis to ascend the Missouri River with a military command, and supplied with the articles necessary to make the proper observations at different points, and if circumstances favor the extension of the enterprise, they are to proceed as far as the Pacific Ocean; while wagers of consideration have been laid that the United States will have a seaport on said ocean before five years roll by.389

Wilkinson accompanied his sugar cargo back to the east coast, amidst much speculation in New Orleans about the source of his new found wealth. Upon his arrival in New York City in May of 1804, the general met in secret with Aaron Burr, which will be the subject of the next chapter.390

The Spanish authorites did send four expeditions out to capture “Captain Merry” as they called him, and in their last attempt they almost succeeded. It happened in September, 1806 as the Lewis and Clark expedition was returning to St. Louis on the Missouri River. About 300 Spanish soldiers were 140 miles west of the expedition when it passed the mouth of the Platte River on September 9th. The soldiers, commanded by Lieutenant Facundo Melgares, were being detained at the Pawnee Indian village on the Republican River near Red Cloud, Nebraska. The Pawnee chief had refused to allow the soldiers to continue on their march to the Missouri, where they almost certainly would have caught Captain Merry and his men.

It seems quite likely the detention of the Spanish force had been prearranged by General Wilkinson with the Pawnee chief. It would have been a major international incident if the Spanish had arrested Lewis and Clark. Only a few weeks later, in October, 1806, Captain Zebulon Pike and his men arrived at the same village and were allowed to continue on a reconnaissance mission into Spanish Texas. Wilkinson’s son, Lieutenant James Biddle Wilkinson, was a member of Pike’s expedition. After leaving the Pawnee village, Pike and Wilkinson split up and Wilkinson’s son and his exploring party returned safely to St. Louis before Pike’s party was captured by the Spanish.391

The general organized three exploring expeditions into the former Spanish Louisiana during this time—the Pike and Wilkinson, Dunbar and Allis, and Freeman and Custis expeditons. These were the expeditions for which the president requested funding of $10–12,000 from Congress.

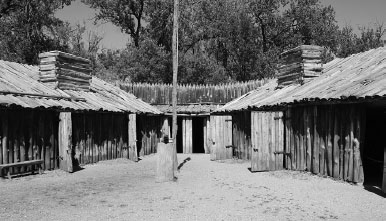

The expedition wintered at Wood River in Illinois Territory at a place they called Camp Dubois. (“Bois,” pronounced bwa, means wood in French.) Wood River was 18 miles north of St. Louis, northeast of the junction of the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers. Clark was in charge of the camp while Lewis spent much of his time at Cahokia and St. Louis. The men arrived at Wood River on December 12th and the next day began clearing land and cutting logs for their huts. Clark’s cabin was ready by December 30th. The weather was sleety with mixed rain and snow and the Mississippi was covered with running ice.

The reconstructed Camp Dubois, an Illinois State Historic Site in Hartford, IL. Although the historic site is enclosed like a fort, the name “Camp” indicates the original site had no walls. www.campdubois.org (Photo by Rick Blond)

George Drouillard arrived with eight soldiers from the Tennessee army post on the 16th. Some were unsuitable, but Hugh Hall, Thomas Howard, and John Potts became members of the permanent party. Drouillard was satisfied by what he saw at the camp, and on Christmas Day announced he would return to Fort Massac to settle his affairs and join the expedition.

The days were a routine of completing the living quarters and hunting for deer and turkeys. Clark had to deal with drunkenness, fighting, insubordination and going AWOL (absent without leave). Matters of discipline would occupy the captains until the men settled down into the tight knit group that became the permanent party going to the Pacific Coast.

Storage lockers were built for keelboat, lining both sides of the boat. Their lids could be raised to provide a shield in case of attack. The men practiced target shooting, competing against local men in the neighborhood. At first the locals won the matches, but by April 27th, Clark was able to report:

Several Country men Came to win my mens money, in doing So lost all they had, with them.393

Meanwhile, Lewis was busy getting to know the St. Louis leaders. The Louisiana Purchase would soon take effect, and the United States needed information about the people living there. After unsuccessful attempts to obtain census data and maps from Spanish officials, Lewis wrote to Jefferson that the government officials and residents of St. Louis feared Colonel Delaussus more than God because—

… he has for very slight offences put some of the most wealthy among them into the Carraboose; this has produced a general dread of him among all classes of the people.

He had no doubt that once Americans came into power that many of the best informed people would be coming forward with information, but until then “every thing must be obtained by stealth.” Nevertheless Lewis had already managed to learn a great deal about the country and its inhabitants which he passed along to Jefferson. 394

Lewis stayed in Cahokia as a guest of John Hay, the Cahokia postmaster. Hay, who served in a variety of government posts, was called “the generalissimo of the pen” for his ability to help people with contracts and deeds. He had come to Cahokia as a merchant representing the British Canadian trading company of Todd & Hay, and he advised Lewis and Clark on their Indian goods—what additional goods to purchase, and how to select the gifts for the individual tribes.

Hay was the son of Jehu Hay, second in command to the “Hair Buyer” General Henry Hamilton who had surrendered to George Rogers Clark at Vincennes in 1789. Both men had been imprisoned in Virginia by Thomas Jefferson. After his release in 1781, Jehu Hay served as Lieutenant Governor of Detroit. In 1785, when John Hay was 16 years old, his father died.395

How would John Hay deal with Clark, the brother of the man who had captured his father, and Lewis, who worked for Jefferson, who imprisoned him? The answer is treacherously, as historian Thomas Danisi has documented. Lewis, who became Governor of Louisiana Territory in 1807 after his return from the expedition, had great difficulties with the postal service.396 This was the world of Louisiana and Illinois Territories—the loyalty of its residents to the new American government could not be taken for granted.

On March 9th, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark attended the ceremonies in St. Louis in which Louisiana was transferred from Spain to France. The flag of France flew over St. Louis for one day. The next day, Upper Louisiana was transferred to the United States. Captain Amos Stoddard, the Kaskaskia commander, was named military commandant for Upper Louisiana and acting governor. A year later in March, 1805, General Wilkinson was named the first governor of Louisiana Territory, while retaining his position as commanding general of the United States Army. Three years later, in March, 1807, Meriwether Lewis would become the second governor.

On the 26th of March, the Secretary of War wrote to Lewis notifying him that William Clark could receive no appointment higher than second lieutenant in the Corps of Artillerists, and enclosed his commission. He assured Lewis that Clark’s military grade would have no effect on his compensation, which would be as Lewis requested.

After the expedition, Nicholas Biddle, the editor of the journals, asked Clark to clarify the matter of his rank, and Clark wrote that when he received his appointment as second lieutenant instead of the captain’s rank he was promised—

My feelings on this Occasion was as might be expected. I wished the expidetion suckcess, and from the assurence of Capt. Lewis, that in every respect my situation Command &c. &c. should be equal to his viewing the Commission as mearly Calculated to autherise punishment to the soldiers, if necessary, I proceeded…. Be so good as to place me on equal footing with Cap. Lewis in every point of view without exposeing any thing … 397

Clark was extremely hurt by this action, and viewed his commission as simply authorizing his ability to discipline the men. He returned the commission as soon as the expedition ended. Lewis and Clark never revealed that Clark had not received a captain’s commission. In 2001, President William Jefferson Clinton promoted William Clark to the rank of captain posthumously.

The expedition set out from Wood River on May 14th, going only as far as St. Charles, where they waited for Lewis to join them from St. Louis. At St. Charles, a small riverfront village on the Missouri River, they were joined by two experienced boatmen, Pierre Cruzatte and François Labiche, who had earlier been enrolled as privates in the U. S. Army. Cruzatte was half French-half Omaha Indian. Labiche was half French-half African American, or “mulatto.”398

Cruzatte was a fiddle player, as most bowmen were. (“Bow” is pronounced like “cow.”) The bowman stayed at the bow, or front of the boat, and directed the course of the boat through the water, paddling with the bow oar. With his fiddle playing and singing, he set the pace for the men rowing with oars or pushing the boat along with iron-tipped poles. Cruzatte would have taken the lead in call and response songs.

In today’s world we can scarcely imagine the importance of singing in performing manual labor—particularly timed and coordinated labor. So as we imagine the three boats going up the Missouri, we should include their music. In the evening the men often danced. They would have danced contra dances (similiar to square dancing) and jigs and reels. It was a chance to get moving after a day in the cramped conditions of the boats.

Labiche served as an interpreter for the expedition, as he spoke both French and English. Like Cruzatte, he was an experienced river man and Indian trader. Labiche and Cruzatte alternated between the larboard oar (left side of the ship, or port) and the bow oar in their duties. Cruzatte, however, was the better navigator and was called upon for the more challenging navigation problems.

The boat was a keelboat, but of an unusual design. It was similiar to the Spanish war vessels that Clark had observed on the Mississippi. The keel is a piece of sturdy wood running underneath the entire length of the boat, to which the rest of the boat frame is attached. Lewis and Clark usually referred to their boat as a barge, rather than a keelboat. A keelboat was generally a long narrow boat with a cabin the middle, used for hauling goods. With a keel, you could go up river against the current. Flat boats, without a keel, could only travel downriver. Their barge had a captains’ cabin at the stern.

Keelboat replica built by Butch Bouvier at Lewis and Clark State Park, Onawa, Iowa. The rudder tiller is seen at the rear, on top of the cabin. The men rowed with single oars standing up, in the center deck. There would have been oarlocks to hold the oars in position. It was a 22 oar boat, 11 men on a side. The boat measured 55 x 8 feet. The cabin and foredeck were 10 feet each; the main deck was 35 feet. It drew three feet of water.399 (Photo by Kira Gale)

The three sergeants, Charles Floyd, John Ordway, and Nathaniel Pryor, were assigned to the front, center, and rear of the boat. The bow sergeant used a setting pole to help the bowman navigate. He kept a look out for all danger, enemies, Indian camps, and obstructions and notified the sergeant at the center, who notified the commanders. The sergeant at the center managed the sail and all matters relating to the crew—rowing, break times, spiritous liquors, and guard duties at the campsites. He was to keep a look out for all notable places, such as rivers, creeks and islands, and notify the captains immediately. The sergeant at the rear, or helmsman, steered the boat, and saw that all baggage on the quarterdeck was stowed away with no loose articles. He was also to “attend to the compass when necessary.”

The sergeants were in charge of the messes, in which the privates were divided into three squads of 8–9 men each. Each mess camped together and had its own cook. The French engagés in the red pirogue and the American soldiers on loan from Kaskaskia in the white pirogue formed their own messes. Altogether there were at least 46 men on the expedition going up river to the Mandan villages in today’s North Dakota. The exact number is unknown as the engages also went by their “dit” names, or nicknames. Pierre Cruzatte, for example, was called “St. Peter.”400

William Clark had the responsibility of map-making and maintaining course and distance records. He most likely used a slate during the day and transferred his notes to his field journal and maps in the evening. He recorded compass directions, distance between points, landmarks, and miles traveled each day. The notes appeared like this for June 4th:

| N. 30° W. | 4 | ms. a pt. on S. Sd. psd. a C & 2 Isd. |

| N. 25° W. | 3 | ms. to a pt. on S. Sd. psd. Seeder C. |

| N. 58° W. | 7½ | ms. to pt. on L.S. a Creek on L. S. |

| N. 75° W. | 3 | Ms. to a pt. on S. Sd. opsd. Mine Hill |

| 17½ |

S. Sd. was Starboard Side, or right. L. S. was Larboard or left side, looking towards the front of the boat. The miles would be measured from landmarks or “points.” Geographer John Logan Allen has written that Clark’s—

coordinate positions are accurate to within 5%, an accuracy level that would not be matched by many cartographers until the advent of mapping aided by aerial photography in the early 20th centry.

Clark calculated the miles from the mouth of the Missouri River to the mouth of the Columbia River at 4,142 miles. Today’s National Historic Lewis and Clark Trail is 3,700 miles long.

The Missouri has been channelized by the Corps of Engineers, so it is no longer the river they experienced. Lewis wrote to his mother—when he was 1609 miles up river at Fort Mandan—that the Missouri River was more dangerous than any Indians they encountered. He described the force of the river as being so strong from the mouth of the great river Platte to the mouth of the Missouri at St. Louis, that they couldn’t use oars or poles to travel in the center’s fast current and had to stay close to the river banks. The banks were often collapsing and bringing trees down with them. Floating trees were hazards, but others anchored in the river bed were hidden from sight in the muddy waters. Sawyers were trees which bobbed up and down and planters were firmly fixed in the river bed. Both could destroy a boat. Sandbars and quick sands could overturn a boat.

On June 9th, William Clark wrote that—

the Sturn of the boat Struck a log which was not proceiveable the Curt. [current] Struck her bow and turn the boat against some drift & Snags which [were] below with great force; This was a disagreeable and Dangerous Situation, particularly as immense large trees were Drifting down and we lay immediately in their Course,—Some of our men being prepared for all Situations leaped into the water Swam ashore with a roap, and fixed themselves in Such Situations, that the boat was off in a few minits, I can Say with Confidence that our party is not inferior to any that was ever on the waters of the Missopie

On June 15th, he described the “worst part” of the river—

we wheeled on a sawyer which was near injuring us Verry much … passed between two Islands a verry bad place, Moveing Sands, we were nearly being Swallowed up by the roleing Sands over which the Current was so Strong that we Could not Stem it with our Sales under a Stiff breese in addition to our ores, we were compelled to pass under a bank which was falling in, and use the Toe rope occasionally.401

They stopped to rest for a couple of days and to make oars and a tow rope from cable Lewis had purchased in Pittsburgh. Two thirds of the men were suffering from boils and ulcers, caused by bacterial infections from the dirty water. Some had 8 or 10 of these “tumers.” The “Mesquetors verry bad.” Despite this, the men were in “Spirits.” The journals are filled with interesting descriptions of their daily lives. Always some men were out hunting. George Drouillard was on permanent duty as a hunter, and exempt from camp duties. He brought in a bear, deer, and turkeys. 402

The sergeants had been ordered to keep journals. Ordway’s and Floyd’s journals are available, but Pryor’s journal hasn’t been found. Ordway was the most faithful journal keeper. He made entries for all 863 days of the expedition from St. Louis to the coast and back (May 14, 1803 to September 23, 1806). Four privates also kept journals. Robert Frazier’s journal is lost, but Patrick Gass’s and Joseph Whitehouse’s journals are published. Gass’s journal—the first to be published in 1807—was edited and his original journal entries are lost. The fourth writer is unknown.403

How did these journal keepers see the dramatic events of June 9th? Ordway wrote: “we got fast on a log Detained us half a hour.” Floyd wrote: “this is a butifull Contry of Land the River at this place is 300 yards. wide the current Strong.” Gass wrote: “This day going round some drift wood the stern of the boat became fast, when she immediately swung round, and was in great danger; but we got her off without much injury.” Whitehouse wrote: “The day proving stormy, we were obliged to waite for our hunters who were on the opposite side of the River, and it being unsafe to venture across in the Pettiauger [pirogue] for them.” Their journals are online at the University of Nebraska Press, with daily journal entries grouped together for readers who like to read original sources. (www.lewisandclarkjournals.unl.edu).

Lewis wrote he was sending journals by separate routes—

in order as much as possible to multiply the chances of saving something. We have encouraged our men to keep journals, and seven of them do so, to whom in this respect we give every assistance in our power.404

When the men sat around the camp at night writing up their accounts of the day’s happenings, was Lewis—the president’s former secretary—also writing his daily account, or was he working on his scientific observations?

There are no daily journal entries by Lewis for the journey from St. Louis to the Mandan villages, except for fragments, dated May 15 and May 20 and September 13 &14, 16 & 17, 1804. They were pages torn from a journal that were found fastened to a later journal with sealing wax. Historian Donald Jackson described the paper as being “worn and discolored.” Jackson, the editor of Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, has suggested that Lewis’s journal was lost in a boating accident on May 14th, 1805, five weeks after they left Fort Mandan. By then the keelboat was on its way back to St. Louis and the captains were traveling in the white pirogue westward towards the mountains.405

Both captains were on shore hunting buffalo when a violent gust of wind turned the pirogue on its side, filling it with water. Only the boat’s awning and sail prevented it from turning over. Sacagawea, who was in the rear of the boat, managed to retrieve “nearly all” of the articles as they floated by. Lewis wrote:

in this perigue were embarked, our papers, Instruments, books medicine, a great part of our merchandize and in short almost every article indispensibly necessary to further the views, or insure the success of the enterprize …

He was preparing to jump in the water and swim to the boat when he realized he would almost certainly lose his life in the attempt. The boat was 300 yards distant, the waves exceedingly high and the water very cold. Private Whitehouse wrote:

We found that most part of her loading was wet, the Medicine damaj’d, & part of it Spoiled—We also found that some of the papers and books had got wet, but not so much as to be spoiled.

Gass wrote: “we found a great part of the medicine, and other articles spoiled.” Ordway wrote: “we opened the goods &c. to get them dry before we packed them up.” Clark simply copied Lewis’s account as he often did. If Lewis’s journal was spoiled in the boat accident, no one was going to reveal it.

When they left Fort Mandan on April 7, 1805 Lewis wrote a letter to Jefferson, sending it back with the keelboat. The keelboat was starting on its return journey to St. Louis bearing articles and specimens for Jefferson and the American Philosophical Society, including live magpies—large and noisy birds—and a live “barking squirrel” (prairie dog). Both arrived safely at the President’s House and then were sent to Philadelphia where they were put on exhibit at Peale’s museum.406

Lewis wrote that he was sending Clark’s journal to Jefferson, which would “serve to give you the daily detales of our progress,” but before copies were distributed to others, Clark wanted his spelling and grammer errors corrected. Lewis wrote that he planned to send a canoe back from the “extreem navigable point of the Missouri” with three or four men, and at that time would send his own journal back with one or two of the best journals being kept by the men.407

Since this letter predates the boat accident, it appears to confirm that Lewis kept a journal en route to Fort Mandan—certainly the pages for six days of entries support this idea. Donald Jackson offers one final bit of evidence in support of his theory. After the boat accident, Clark, who had been simplifying Lewis’s scientific descriptions of plants and animals, began copying the descriptions word for word in his own journal.

The captains split the science duties. Clark had the task of recording course and distance so he could make his maps, which required his steady attention throughout the day. Lewis was responsible for daily weather records and writing descriptions of noteworthy features of the landscape—mineralogy, geology, soil, seasonal changes, etc. He collected plants new to the United States and described them using a botanical text for reference. He did the same for animals and preserved specimens to be sent back to Peale’s Museum. He created a chart of rivers and creeks on the Missouri. They had a library of travel journals, scientific references, and maps in their boat cabin, including the Mackay-Evans map and Evans’s Indian notes.

The captains collaborated on the task of making celestial observations in order to determine the latitude and longitude of river junctions and other points. The position of the North Star at night was used to determine their latitude by measuring its angle to the horizon with a sextant. The position of the sun at its high point was used to compare the local noon hour with the time on the chronometer clock to find their longitude. The chronometer’s time had been set at Pittsburgh. Their latitude readings were accurate, but when their chronometer clock ran down and had to be recalibrated by guesswork, errors crept it. These observations required the mathematical calculations that Lewis had been trained in before leaving on the expedition.

As they encountered Indian tribes they sought answers to the questions proposed by Jefferson and others—the tribe’s life style, population, geography, number of warriors, enemies, cultural traditions, health practices, and trade networks. The commercial fur trade was a major focus. What kinds of furs were available, what were the best places to build trading forts, and what were the most desirable articles to exchange for furs? During the winter at Fort Mandan, Lewis and Clark prepared an elaborate chart, which they called “Estimate of Eastern Indians.” The chart provided data on nearly 50 tribes and bands from information they had obtained either first hand, or from reports by other Indians and fur traders.

Jefferson and his fellow American Philosophical Society members were fascinated with comparing Indian languages to European and Asian languages, believing it might hold the key to discovering common ancestries. Lewis recorded the vocabularies of twenty three different Indian tribes on blank vocabulary sheets with 250 English words printed on them. Lewis intended to publish his scientific information and the Indian vocabularies in the third volume of his planned three volume account of the expedition. Unfortunately, these vocabulary sheets were lost after his death and the third volume was never published.408

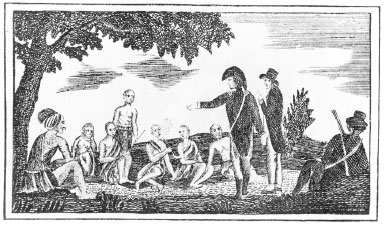

First Council with the Otoe and Missouria, woodcut from Patrick Gass’s published journal.

Their first council with Indians was held with the Otoe and Missouria Indians at Council Bluffs on August 3rd, 1804. The Otoe lived near the junction of the Platte and Elkhorn Rivers in an earth lodge village. Their kinfolk, the Missouria had joined them there, after warfare and disease had driven them from their home on the Grand River in Missouri. The two tribes had gone off on their annual summer buffalo hunt, leaving the village deserted.

Cruzatte and Drouillard had been sent to invite them to come in for a council. Cruzatte was half Omaha and knew the area well. He had operated a trading post for the Omaha near Council Bluffs for two years. It seems likely that he had accompanied MacKay’s expedition up river in 1796–97 and decided to remain. Some days after finding the village deserted, Drouillard heard gun shots and encountered a group of Missouria out hunting elk. Messengers were sent to find the Otoe and bring them in for the council.

The Otoe chiefs arrived bringing gifts of “water millions.” Speeches were made and medals, a flag, and presents given out. The French trader who came with them said the Otoe traded with the Spanish at Sante Fe, a journey of 25 days. The captains recommended that a trading post be built at Council Bluffs and Fort Atkinson was established there in 1819.

The expedition traveled much more easily on the Missouri River after passing the mouth of the Platte. The river no longer rushed downstream at a rate of 5–6 miles per hour, but moved along at a leisurely 3 miles per hour. However, the bends of the river could make it a frustrating day’s travel. One bend measured a little more than half a mile (973 yards) by land, but it was a day’s journey, 18 3/4 miles, by water.

The Otoe chiefs had asked the captains for help in arranging a peace between themselves and the Omaha, and it was agreed they would come up for another council at the Omaha village, some eighty miles up the Missouri. As they left Council Bluff, Private Moses Reed deserted the expedition, and Joseph Barter, “La Liberte,” a French engagé, also deserted. Drouillard was sent with three men to find them, with orders to kill Reed if he didn’t come in peaceably and to bring back La Liberte from the Otoe village, where it was presumed he had gone.

As they neared the Omaha village they stopped to climb the hill where Omaha Chief Blackbird was buried, and planted a white flag at his gravesite. Blackbird and 400 members of his tribe had perished in a small pox epidemic four years earlier. The next day they passed the location of MacKay’s old trading post, Fort Charles, and formed a camp 5 miles further up river. They called it “Fish Camp” because they caught about 1,100 fish, using a brush barrier dam on a creek, while waiting there.

The Omaha village, like the Otoe village, was deserted. The Omaha were away on their summer buffalo hunt. When the three Otoe chiefs, accompanied by 8 lesser chiefs and warriors, arrived with Drouillard at the camp on August 18th, there was no chance to arrange a peace with the Omaha. Drouillard and his party had found both Moses Reed and La Liberte. However, en route to the Omaha village, La Liberte had escaped again.

August 18th was a memorable day. It was Meriwether Lewis’s 30th birthday. William Clark had celebrated his 34th birthday at Council Bluffs on August 1st with a feast of game and ripe fruit. Lewis’s birthday, however, was definitely mixed. The deserter Reed was ordered to run the gauntlet four times, and received about 500 lashes from the men. Clark wrote that they were “as favorable to him as they could be, consistent with their oaths.”409 Before his punishment, the Otoe chiefs requested his pardon. After the captains “explained the customs of their country,” the chiefs were satisfied. Reed was dismissed from the permanent party, and would return with the soldiers from Kaskaskia to St. Louis in the spring. After the court martial and punishment, they held a dance. The dance, celebrating Lewis’s birthday, lasted until 11 that night.

The next day it became obvious that Sergeant Charles Floyd was seriously ill. The captains were still meeting with the chiefs counseling with them about their altercations with the Omaha and Pawnee. Clark wrote:

Sergt. Floyd was taken violently bad with the Beliose Cholick and is dangerously ill … nature appear exosting fast in him every man is attentive to him (york prlly) [York, primarily].410

Floyd, apparently, was suffering from a ruptured appendix and peritonitis. He had not been feeling well for more than a month. He wrote on July 31st:

I am verry sick and Has ben for Somtime but have Recovered my helth again.411

If he was treated with Dr. Rush’s Bilious Pills—laxatives called “Thunderclappers”—it could have irritated an already inflamed appendix in the days before his death. They may have bled him, another treatment promoted by Dr. Rush, who urged removal of blood, from a few ounces to 80 ounces (about half the blood in the body), as a cure for illness.412

Sergeant Floyd was only 21 years old when he died. As they proceeded up river the next day, they stopped to make a warm bath for him. But, before they could get him into the bath, he died. Clark wrote:

Serj. Floyd Died with a great deel of Composure, before his death he Said to me, “I am going away” I want you to write me a letter”—We buried him on top of the bluff ½ Miles below a Small river without a name to which we Gave his name, he was buried with the honors of War much lamented; a Seeder post with the name Sergt. C. Floyd died here 20th of August 1804 was fixed at the head of his grave—This man at all times gave us proofs of his firmness and Deturmined resolution to doe Service to his Countrey and honor to himself after paying all the honor to our Decesed brother we Camped in the mouth of floyds river about 30 yards wide, a butifull evening.—413

The Sergeant Floyd Monument at Sioux City, Iowa on Sergeant Floyd’s Bluff. It became America’s first National Historic Landmark in 1960. (photo by Kira Gale)

Captain Lewis read the funeral service, and the bluff was named Sergeant Floyd’s Bluff. He was the only man to die on the expedition. On August 26th, by a vote of a large majority of the men, Patrick Gass was chosen to replace Floyd. In his orders appointing Sergeant Gass, Lewis used the term “the corps of volunteers for North Western Discovery” for the first time in the journals.

On the very same day, August 26th, a new crisis was about to develop. Drouillard and George Shannon were sent out to look for lost horses. The expedition had a small number of horses accompanying them, used by the men in hunting game. There were now ripened grapes, and three kinds of plums of “delicious flavor” in the fields ready to eat. They had been checking out the fruit as hungrily as birds for weeks.

It was fortunate for George Shannon that the fruit was ripe, because he became lost after separating from Drouillard. Shannon believed he was behind the boats and hurried to catch up with them—but, instead, he was in front of the boats. Shannon was lost for 16 days until the boats finally caught up with him on September 11th. He had eaten only grapes and one rabbit—which he shot with a hard stick from his gun—for twelve days. He still had his horse, which he would have killed and eaten as a last resort.They saw from his horse tracks that he was ahead of the boats, but the men sent after him couldn’t overtake him. During Shannon’s absence he missed some big events—the election of Patrick Gass, the council with the Yankton Sioux, and catching a live prairie dog.

The council with the Yankton Sioux took place at Calumet Buffs on August 30–31. Coming up river they had acquired the services of Pierre Dorion, Sr. a long time trader with the Yankton Sioux. They realized they needed someone who could interpret for them with the Sioux. However, once they met in council with the Yankton, they decided Dorion could be more usefully employed in escorting a delegation of Sioux chiefs to Washington in the spring of 1805. Dorion remained with the Yankton, and it meant they would be without the services of a skilled interpreter when they encountered the more hostile Teton Sioux up river.

They spent most of September 7th trying to catch a prairie dog. The village of underground tunnels of the “barking squirrels” covered three acres. First they dug through six feet of hard clay in an attempt to reach their lodges. Then they resorted to a bucket brigade, pouring gallons of water down a hole, to flush one out. Seaman, the dog, must have been eager to help. The little creature was put in a cage and lived with the captains for months before it was sent to Washington.

They were seeing a great many buffalo by now. Clark killed a male pronghorn, which they called an antelope or wild goat, on September 14th. On the same day, John Shields killed a prairie hare, or jack rabbit. Lewis measured the leap of one hare at 21 feet, noting “the ground was a little descending.” They stuffed the pronghorn and hare to send back to Peale’s Museum. Among the pages of Lewis’s notes that were found for September 13 & 14, 16&17, was this observation by Lewis on September 16th—

… these extensive planes had lately been birnt and the grass had sprung up and was about three inches high. vast herds of Buffaloe deer Elk and Antilopes were seen feeding in every direction as far as the eye of the observer could reach.414

The Indians practiced fire burning in the spring to create new grass for the animal herds. They also set the prairies on fire as signals—to bring in other tribes, to warn of danger, or to announce the presence of a buffalo herd. The prairies were not naturally treeless—regular burning destroyed all trees except those near creeks and rivers.415

On the 17th, Lewis killed a female pronghorn to send back. These animals were new to science. The pronghorn is the fastest quadruped in America; it can run up to 60 miles per hour and Lewis said it could smell a hunter at a distance of three miles. He estimated he saw 3,000 buffalo in one view that day.

Naturalist Paul Cutright wrote that zoologically this area was the “most important and most exciting of the entire trip.” From the Niobrara River in Nebraska to the Bad River in South Dakota, a distance of 263 miles, they discovered and named nine animals for science—the pronghorn, coyote, plains gray wolf, prairie dog, mule deer, white-tailed jack rabbit, black-billed magpie, sharp-tailed grouse and desert cottontail.416

On September 20th, they arrived at the Big Bend of the Missouri River—30 miles by water and 1¼ miles by land. The next day, the bank of the sand bar on which they were camping began to give way during the night and would have swallowed their boats within minutes. They rushed to the boats and the bank caved in before they reached the opposite shore. They passed Loisel’s trading post on Cedar Island with a number of Indian camps around it on the 22nd. No one was there.

On the 23rd, three Sioux boys swam the river and informed them the Brulé Sioux (Teton or Lakota Sioux) were camped a short distance above. Some Sioux stole Colter’s horse while he was out hunting on the 24th. Two thirds of their party stayed on board the boats that night, and the rest stayed with the guard on shore. On the morning of the 25th they raised a flag on a staff, and set up the sail for a shade awning to council with the Brulé chiefs.

They gave out medals and presents and invited the 3 chiefs and a warrior to come on board the keelboat to view the “many Curiossites.” After a small drink of whiskey the 2nd chief, Partisan, became troublesome, pretending he was drunk. He was a rival to the 1st chief, Black Buffalo, and resented the more splendid presents he had been given. Clark got them into a pirogue to take them back to shore. At the shore they were met by three young Sioux, who seized the cable rope of the pirogue, while one warrior held fast to the boat mast. Partisan was insulting and threatening, saying he wouldn’t get off the boat until he received more presents. Clark wrote: “I felt my Self warm & Spoke in verry positive terms.”

Clark drew his sword and the men in the pirogue took up arms, while Captain Lewis and his men took up arms and loaded the 3 swivel guns on the boats for action. The Indians on shore had their bows and arrows and guns ready to fire. At this point, the 1st chief of the Brulé Sioux, Black Buffalo, took hold of the rope from the young men and defused the situation. After some time on shore, Black Buffalo, two of his warriors, and the 3rd chief, came on board the keelboat to escort them to a new campsite, which the captains named “bad humered Island as we were in a bad humer.” This is how the Bad River in South Dakota got its name.

The next day Black Buffalo and his entourage stayed with the keelboat as it proceeded five miles up river to his own camp, with Indians lining the shore to observe the boats progress. Black Buffalo’s camp had about 100 tipis, all made of white colored buffalo hides, arranged in a circle around a large council tipi. Captains Lewis and Clark were carried into the village on white buffalo robes, a mark of great esteem. There was feasting and a dance that evening, with food sent out to the men in the boats. A council was held in the central lodge with about 70 elders and warriors. An elder and Black Buffalo “spoke approvingly of what we had done.” That evening Black Buffalo slept on the boat with them.

The Sioux had lately been at war with the Omaha and had killed 75 men. They had also captured 48 women and boys, held captive in two villages. Pierre Cruzatte, who spoke Omaha, learned from them that the Sioux intended to stop the expedition. At the council, the chiefs had promised to deliver the Omaha captives to Pierre Dorion, the Yankton trader.

The Indians wanted the expedition to stay for several more days, as they expected the arrival of more Sioux to see the Americans. After another night of feasting and dancing, Partisan and one principal man were accompanying William Clark in the pirogue, going back to the keelboat. Through bad steering, the pirogue cut the cable holding the keelboat anchor. The keelboat anchor sunk and the pirogue sprung a leak. All of this alarmed the Indians. Black Buffalo and about 200 warriors came down to the river bank, armed for action. Seeing that it was a false alarm, they left, but about 20 warriors remained on shore and Black Buffalo came on board again.

The next day, after searching in vain for the anchor, the captains decided it was time to leave.There were theatrics. The 2nd chief, Partisan, wanted tobacco and a flag, which they refused to give him, and some young men held the keelboat cable, demanding tobacco. The captains reluctantly gave Black Buffalo two twists of tobacco, which he gave to the men, and took the cable from them. It was a face saving maneuver. Tempers were frayed on both sides. As they continued up river, Black Buffalo stayed with the boat for two more days until announcing that all things were clear for them and they would not see any more Tetons.

The Sioux were a roving tribe, the warriors of the plains. They were the tribe that Jefferson most wanted to conciliate and establish trade relationships with. They had a long connection with British traders. Jefferson had enclosed excerpts from the journal of Jean-Batiste Truteau in a letter to Lewis. Truteau, who traded with the Upper Missouri tribes, had written:

The Sioux inhabit the Northern part of the Mississipi, and are hostile to the Ricaras, Mendanes, big-bellies and others. Others of them live on the river St. Pierre. They have from 30 to 60,000 (?) men and abound in fire-arms. They are the greatest beaver hunters; and could furnish more beavers than all the other nations besides, and could bring them to a depot on the Missouri, rather than to St. Pierre, or any other place. Their beaver is worth double of the Canadian for its fineness of it’s fur and parchment.417

The rivalry between the two chiefs had complicated matters, but it allowed Black Buffalo to establish a relationship with the Americans which would later have a great impact on the War of 1812. In 1813, after Lewis’s death, William Clark was serving as both the Governor of Missouri Territory and Superintendent of Indian Affairs. At the start of the war, he appointed Manuel Lisa a sub-agent for Indian Affairs, and provided trade goods to send up to Lisa’s new post on Cedar Island to keep the Brulé Sioux out of the war.

Black Buffalo sent a messenger to the Santee Sioux of the Minnesota River (St. Pierre River) to stop fighting for the British in Michigan and come home, or he would burn their villages. The Santee had been recruited by the British trader Robert Dickson. After the war, at a British court of inquiry, Dickson blamed the Sioux defection for the American victory on Lake Erie, the loss of Amherst and Detroit, and the subseqent capture of General Proctor’s army. About 2,000 warriors returned to their homes after the Siege of Fort Meigs, reducing Tecumseh’s Indian army to about half its size.418

Lewis and Clark’s diplomacy with the Indians of the Missouri was continued by Manuel Lisa, who employed former members of the Lewis and Clark expedition in his fur trading empire. Lisa observed at the end of the war:

The Indians of the Missouri are of those to the Upper Mississippi as four to one. Their weight would be great, if thrown into the scale against us. They did not arm against the Republic; on the contrary, they armed against Great Britain, and struck the Ioways, the allies of that power.

Lisa arranged for both Yankton Sioux and Omaha war parties to attack the Ioway. The Ioway didn’t care about a peace treaty ending the war and were continuing to attack settlers.

At the end of the War of 1812 in the summer of 1815, Manuel Lisa brought 33 chiefs and important men of the Missouri tribes to William Clark’s treaties council at Portage des Sioux at the junction of the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers near St. Louis. Over 2,000 Indians attended and at least 19 tribes signed peace treaties with the United States.

Both Partisan and Black Buffalo came with Lisa’s delegation. Black Buffalo died suddenly of an unknown cause at the council. Was he assassinated? He was surrounded by Indians who had fought for the British; he was a known collaborator; and Partisan was his enemy. His death was marked by great ceremonies.

Omaha Chief Big Elk delivered the funeral oration. Big Elk’s daughter was married to Manuel Lisa. The English translation of his speech, “Big Elk’s Funeral Oration on the Death of Black Buffalo,” was immediately published in books by John Bradbury and Henry Brackenridge and it remains a classic of Indian oratory. It begins—“Do not grieve—misfortunes will happen to the wisest and best men …” and eloquently described the ceremonies honoring Black Buffalo: “a noble grave with a flag raised over it, a grand procession, rolling music, and a thundering cannon—”.419

On October 1st, near the Cheyenne River, they visited with Jean Valle at his trading post for the Sioux. He came on board and stayed with them for a day. It was turning cold and the geese were flying south in large flocks. Small groups of Teton Sioux were still following them, begging for tobacco. On October 6th, near the Grand River, they saw a deserted Arikara village of about 80 lodges made of earth, each lodge 20–60 feet in diameter. They were packed closely together and surrounded by a picketed stockade fence. Squashes of three different kinds were growing at the village. On the 8th they passed another deserted village of about 60 lodges, which apparently had been used the last winter.

Finally they came to an inhabited Arikara village on an island three miles long, where they were growing corn, beans, squash and tobacco. They met the trader, Joseph Gravelines, who had lived with the Arikara for over 20 years, and Pierre Tabeau, a trader from St. Louis. They saw their first bull boats in the water—bowl-shaped boats made from buffalo skins. Clark remarked:

I saw at Several times to day 3 squars [women] in single Buffalow Skin Canoes loaded with meat Cross the River, at times the waves were as high as I ever Saw them in the Missouri—

On October 10th, they raised the flag and set up the awning to hold a council with the Arikara chiefs. They designated three chiefs, one for each village. and gave medals to them. A Sioux attended the council and they were told he had come to the Arikara to persuade them to stop the expedition.

York was the first black man the Arikara had ever seen. They called him “the big medison.” York took great delight in his new celebrity. Clark wrote:

the Inds. much astonished at my black Servent, who made himself more turrible in thier view that I wished him to Doe as I am told telling them that before I cought him he was wild & lived upon people, young children was verry good eating Showed them his Strength &c. &c.

The next day they took on board the two chiefs whose villages were up river from the island. These villages—surrounded by picketed stockade fences and located across the river from each other—would prove the downfall of the Missouri River fur trade in the years to come. Any expedition attempting to come up river was completely vulnerable to an Arikara attack.

Three years later in 1807, some of Lewis and Clark’s men, who were part of a new expedition led by Nathaniel Pryor, were attacked by the Arikara. Two were wounded and one most likely lost his life. George Shannon lost a leg, George Gibson was wounded, and Joseph Fields was probably killed, as William Clark listed him as “killed” in 1807. In 1823, another battle took place between the Arikara and the Ashley-Henry expedition. After that, the fur trade avoided the Missouri River and switched to the rendezvous system, hauling goods back and forth by wagon along the Platte River to the mountain men who remained in the West year round.

Tabeau reported that the Arikara once lived in 18 villages along the Missouri, but their population had been drastically reduced by small pox epidemics and war with the Sioux. In the three villages, there were at least ten different bands of Indians and more than 42 chiefs. The bands did not all speak the same language, and intense rivalries and jealousies hindered any cooperation. They relied on trading their agricultural products with the hunting tribes of the plains for meat and hides. They also acted as middlemen—trading in horses, obtained from Indians of the Southern Plains, and trading in guns, ammunition, and manufactured goods, obtained from the Assiniboins and Sioux who got them from British traders.

The Arikara had 500 warriors and a great quantity of arms. The Sioux, while trading with them, took what they wanted, set prices, stole horses, and sometimes murdered them. The Arikara had been at war with both the Sioux and the Mandan. One of Lewis and Clark’s diplomatic goals was to arrange a peace between the Arikara and their neighbors, in order to “clear an open road” for American traders. An Arikara chief joined the expedition and accompanied them up to the Mandan villages, hoping to arrange a peace which would allow them to present a united front against the Sioux. But because of internal rivalries and the military power of the Sioux, the alliance proved unworkable. 420

The Arikara, like the Sioux and Mandan, offered their women to white men as sex partners. They encouraged sex as a way of extending hospitality, receiving presents, and building business relationships. They believed that spiritual power was transferred in the sexual act, and this power would be passed onto the husbands of the wives who engaged in it. Indian women followed the boats as they left the Sioux, and again as they left the Arikara. Patrick Gass wrote approvingly of “a great number of smart and handsome women and children” among the Arikara. As they left the Arikara, they took on board two women. Clark wrote:

a curious Custom with the Souix as well as the receres is to give handsom Sqars to those whome they to Show Some acknowledgements to—the Seauix we got Clare of without taking their Squars, they followed us with Squars 13th two days. The Rickres we put off dureing the time we were at the Towns but 2 Handsom young Squars were Sent by a man to follow us, they Came up this evening and persisted in their Civilities.421

Clark spoke more honestly about these matters in talking with Nicholas Biddle, the editor of the journals, and told him that “the men by means of interpeters found no difficulty in getting women” at the Arikara villages.422

The two young women came on board on October 12th. On October 13th Private John Newman was “Confined for mutinous expression” and a court martial was held the same day. He was charged with “having uttered repeated expressions of a highly criminal and mutinous nature.” A jury of his peers, two segeants and seven privates, unanimously judged him guilty. Two-thirds of them concurred with his sentence of 75 lashes on his bare back. It may, or may not, be relevant that at least one of the young women stayed on board the boat until October 15th.

He was discharged from the permanent party and ordered to labor on the red pirogue with the Frenchmen. Both John Newman and the deserter Moses Reed returned to St. Louis with the keelboat in the spring. The Arikara chief cried out loud as he witnessed Newman’s whipping on October 14th. Clark wrote:

I explained the Cause of the punishment and the necessity He thought examples were also necessary & he himself had made them by Death, his nation never whiped even their children, from their birth.

Later, Lewis wrote to the Secretary of War stating that Newman had performed valuable services at Fort Mandan and saved the keelboat from harm on several occasions on the return journey. He urged that Newman receive his full pay, and wrote that Newman had begged to accompany them on the journey to the coast, but he thought it “impolitic to relax from the sentence altho’ he stood acquitted in my mind.”423

The captains had devised their own, irregular, form of a court martial, as they had no access to a court composed of the required minimum of three commissioned officers. They could have administered punishments themselves, but instead chose to use a jury of enlisted men in every case except one—the captains sentenced Alexander Willard to 100 lashes for sleeping on duty on July 12, 1804. John Collins was sentenced twice to receive whippings, once for disrespect to an officer and going AWOL at St. Charles on May 17th (50 lashes); the other time for drunkeness and allowing Hugh Hall to open a barrel of whiskey on June 29th (100 lashes). Hall received 50 lashes. Clark wrote that the men were always “found verry ready to punish such crimes.” On February 9th, 1805 Thomas Howard was punished for violating security at Fort Mandan. He received a sentence of 50 lashes for climbing over the stockade fence, which was not carried out.

There were no more corporal punishments and they worked together as a team under extraordinary circumstances. At the end of the expedition Whitehouse wrote—

… the manly and soldier-like behavior; and enterprizing abilities; of both Captain Lewis and Captain Clark … and the humanity shown at all times by them, to those under their command, on this perilous and important Voyage of discovery.424

Robert Hunt, writing about crime and punishment on the expedition, raised an interesting question about the captains asking the men to decide matters by a vote. Is Patrick Gass the only sergeant in the history of the United States Army to have been elected by a vote of the men? 425

Immense herds of pronghorns were now swimming across the Missouri heading west to their winter grounds in the Black Hills. Near the mouth of the Cannonball River—named for the round stones in its waters—they met two French trappers who complained about being robbed of their beaver traps by the Mandans. The trappers joined the boat flotilla, hoping to get their traps back.

On October 19th Clark counted 52 “gangues” of buffalo and 3 of elk as he walked on shore. He also saw the ruins of an old Mandan village with a “high strong watchtower” on top of a 90 foot high hill. The Arikara chief said they would see several old Mandan villages ahead near the Heart River, which the “Troubleson Seauex” had forced them to leave.

They had their first encounter with a grizzly bear, recorded by Lewis in his natural history notes for October 20th. It was the first of many encounters to come. Lewis wrote:

Peter Crusat this day shot at a white bear he wounded him, but being alarmed at the formidable appearance of the bear he left his tomahawk and gun; but shortly after returned and found the bear had taken the opposit rout.—

Clark wrote, “I saw Several fresh tracks of that animal double the Sise of the largest track I ever saw.” 426

On the 21st, Clark saw a sacred stone boulder, the “Medicine Rock” of the Indians, marked with petroglyphs and a ceremonial oak tree on the open prairie. The chief told Clark that Mandan warriors suspended themselves from the tree, by piercing the skin of their necks and threading cords through the holes, “to make them brave.” They saw a war party of 12 naked Sioux on their way to attack the Mandans.

On October 24th they met a grand chief of the Mandans camping on an island with a hunting party. Lewis went with an interpreter and the chief to his village, located a mile up the river. The next day, the British trader Hugh McCracken greeted them and on the following day they met René Jessaume, the long time resident trader, whom they hired as an interpreter. Jessaume was the trader who had tried to kill John Evans.

The expedition remained with the Mandan and Hidatsa for over five months. They left on April 7th, 1805. The two tribes lived in five villages. There were two Mandan villages along the Missouri near the Knife River, and three Hidatsa villages along the Knife. After the Mandans were decimated by small pox and attacks by the Sioux, they had moved from their villages on the Heart River, where they had lived for two hundred years, to join forces with the Hidatsas in the 1780’s. The Hidatsa were also known as the Minatarees or the Gros Ventre of the Missouri. They were three related tribes who spoke different dialects. The Hidatsas roamed more widely than the Mandans, although both were agricultural people.

The five villages had a combined population of 3,000 to 4,000. (Washington D. C.’s population was 3,210 and St. Louis’s, 795.) Clark in his “Estimate of Eastern Indians” reported the Mandans numbered between 1,250–1,500; the Awaxawis at the first village of the Hidatsa, 200–300; and the Minetarees of the upper two villages, 2,500. The report described the Mandans as “the most friendly, well disposed Indians inhabiting the Missouri. They are brave, humane, and hospitable.”427

The villages were the trading center of the Northern Plains, with a network of trade stretching thousands of miles. They traded their corn, beans, squash and tobacco with the Cree and Assiniboin of Canada, who provided manufactured goods obtained from British and Canadian traders. The nomadic tribes of the plains, the Cheyenne, Crow, and Arapahoe, brought buffalo meat and hides to the market. The Cheyenne brought Spanish horses and mules and fancy leather clothing. The most prized trade goods were English trade guns and ammunition.428

North Dakota Lewis & Clark Interpretive Center, Fort Mandan; Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site, Knife River and Hidatsa earth lodge at Sakakawea village site (Photos by Rick Blond) www.fortmandan.com and www.nps.gov/knri