Lewis and Clark decided they wouldn’t send back a return party from the headwaters, as they could use the manpower, and it would have demoralized the men to have any of them sent back. They were a team. Lewis wrote on July 4th, 1805, while they were still dealing with the iron boat:

… we all beleive that we are now about to enter on the most perilous and difficult part of our voyage, yet I see no one repining; all appear ready to met those difficulties which wait us with resolution and becoming fortitude.466

He described the mountains they were about to cross as the shining mountains for their “glittering appearance” with the sun shining on the snow. July 4th was also the end of their alcohol. They gave the men the last of the “sperits” and the men danced to the fiddle until heavy rain ended the dancing and they continued with songs and jokes.

By July 8th the buffalo were on the move. Lewis observed that wherever they saw buffalo, if they were undisturbed, they were moving in the same direction. The great migration south was beginning. They buried the iron frame boat and the truck wheels in a cache at Upper Portage Camp on July 10th. Clark had taken a crew of men ahead to find suitable trees to make two more canoes, replacing the white pirogue. The new canoes were 25 feet and 33 feet in length and about 3 feet wide. On the morning of July 15th, they set out for the headwaters region of the Missouri with eight canoes, all heavily laden. Lewis wrote:

we find it extreemly difficult to keep the baggage of many of our men within reasonable bounds; they will be adding bulky articles of but little use or value to them.467

The canoes weren’t big enough to carry all the men and their baggage—the captains and the men who weren’t navigating the boats walked along the shore. The prickly pear and sunflowers were in full bloom, and the mosquitoes and gnats were as troublesome as always. Lewis went ahead with several men to discover where the river entered the mountains. Unfortunately, he forgot to bring along his mosquito netting, and wrote that he—

… of course suffered considerably, and promised in my wrath that I never will be guilty of a similar peice of negligence while on this voyage.

Lewis described their “musquetoe biers” as being made of “duck or gauze like a trunk—to get under.” He wrote that without their “natural rest,” it would have been impossible for the men to endure the fatigue of their daily life.468

They were now in Piegan Blackfeet territory. The Blackfeet were a confederacy of three Blackfeet nations, extending across the border of the United States and Canada east of the mountains. The Blackfeet obtained guns from British traders on the Saskatchewan River in Canada and were a nomadic, warlike people like the Sioux. They were enemies of the Shoshone and Flathead (or Salish) Indians, who had been forced to retreat into the mountains because they lacked guns and ammunition.

Lewis and his men had rejoined the boats, when on the morning of July 18th, Clark, York, J. Fields, and Joseph Potts set off to find the Shoshone, taking an Indian road over the mountains. Meanwhile the boats were going through a “dark and gloomy” place which Lewis named the “gates of the rocky mountains”—dark cliffs, about 1200 feet high, enclosing both sides of the river for 5 3/4 miles. Clark and his party walked 30 miles over two mountains on an old Indian road. Clark wrote:

my feet is verry much brused & cut walking over the flint, & constantly Stuck full Prickley pear thorns, I puled out 17 by the light of the fire to night… Musquotrs verry troublesom.469

On July 20th, the plains were set on fire by the Shoshone to warn others of their approach. They later learned that the Indians, hearing gun shots from Clark’s party, had fled into the mountains thinking they were a Blackfeet war party. Clark left signs along the road to indicate they were white men.

By July 22nd, Sacagawea was recognizing the country and assuring them they would soon reach the Three Forks of the Missouri headwaters. It was 80 degrees, the warmest day they had experienced that summer, except for one. They met up with Clark’s land party, and even though his feet were terribly bruised and sore, Clark insisted on continuing despite Lewis’s offer to switch places. Clark, the two Field brothers, Frazier, and Charbonneau set off to find the Shoshone, or Snake Indians, as they called them. Lewis ordered the canoes to hoist their small flags to announce to the Indians they were not their enemies. He did name his own enemies, however—“Musquitoes, eye knats and prickley pears.” Lewis was also assisting the men in their labor, and said he had “learned to push a tolerable good pole.” 470

Clark arrived first at the Three Forks of the Missouri River and left a note on a pole telling Lewis they were taking the north fork (the southwest river or Jefferson). They went 25 miles up the river. Clark’s feet gave out, and Charbonneau hurt his ankle. When they limped back to Three Forks, Charbonneau—who could not swim—was swept away by the strong current, and had to be rescued by Clark as they were crossing the river to reach the middle fork (the Madison). They explored the middle fork for eight miles, and then returned to the junction, where they found Lewis and the others waiting for them. Clark was sick with a high fever, body aches, and infected feet. They decided to rest for a couple of days. The next day, on July 28th, they named the three forks the Jefferson, Madison and Gallatin, in honor of President Thomas Jefferson, Secretary of State James Madison, and Secretary of Treasury Albert Gallatin. Lewis called them all “noble streams” and recommended a fort be established there.

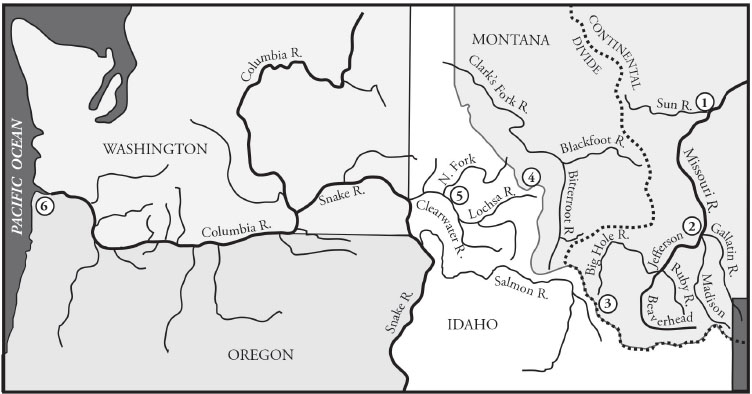

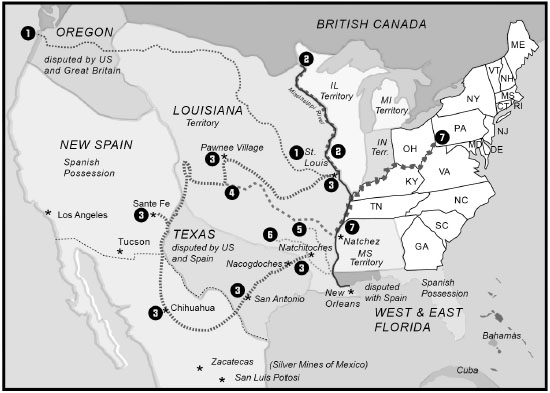

Finding a navigable water route to the Pacific Ocean: 1. Great Falls Missouri River 2. Three Forks Jefferson & Beaverhead Rivers 3. Lemhi Pass 4. Lolo Pass Lochsa River 5. Canoe Camp Clearwater, Snake & Columbia Rivers 6. Fort Clatsop.

They were becoming increasingly anxious about locating the Snake Indians, as they called the Shoshone. They had left the buffalo country and game was becoming scarce. Their headwaters campsite was the exact place where Sacagawea’s people had been camping when they were attacked by the Minataree from the Hidatsa villages on the Knife River. The Shoshone fled about 4½ miles up the Jefferson, where the Minatarees killed 4 men and 4 women and a number of boys, and made prisoners of the rest of the females and 4 boys. Lewis wrote that Sacagawea showed no emotion at returning there, or of the prospect of being reunited with her people. He commented:

… if she had enough to eat and a few trinkets to wear I beleive she would be perfectly content anywhere.471

But he would soon find out he was mistaken.

They had a “lame crew” just then. Two had tumors or bad boils, one had a bad stone bruise, one had his arm dislocated but it had been well replaced, and the fifth, Sergeant Gass, had hurt his back in a fall. Lewis decided to set out with Gass, Drouillard, and Charbonneau, who insisted his ankle was healed enough to go with him, and go in search of the Shoshone. Gass could walk, but couldn’t do boat work. Lewis wrote the heat was intense during the day, but they needed more than two blankets in the night. They were traveling through a large valley when they came to the forks of the Jefferson River. He wrote a note to Clark saying that he should take the middle fork, or the Beaverhead River, and left the note on a pole. Lewis and Drouillard then climbed to a high point and confirmed the middle fork was the right choice.

The men on the river were having great difficulty. Many of them had feet so swollen and painful they could scarcely walk as they pushed and pulled and lifted the canoes through the turbulent waters. Clark had a tumor on his ankle which was extremely painful. When they got to the three forks of the Jefferson, they didn’t find the note Lewis had left on the pole. A beaver had chewed the pole down, and Clark chose to go up the Big Hole River instead of the middle fork, the Beaverhead.

They had a boat accident on the Big Hole and the baggage got wet. Whitehouse almost lost his life when he was run over by a canoe. On August 6th they returned to the forks, where they reunited with Lewis and dried out their goods. Lewis had taken the precaution to secure their powder in small lead kegs sealed with cork and wax. The lead containers were melted down to make bullets and the powder was used to discharge the bullets from their guns. It was an ingenious way to keep their powder dry.

They called three forks the Wisdom River (Big Hole River), the Philanthropy River (Ruby River), and the middle fork, they continued to call the Jefferson River. They were right that it was leading to the ultimate source of the Missouri River. Lewis wrote these were the “cardinal virtues, which have so eiminently marked that deservedly selibrated character through life.” 472 The middle fork, the Jefferson, is now called the Beaverhead River.

It happened their two objectives—to obtain horses from the Shoshone and to find the source of the Missouri River—both were fulfilled by continuing to ascend the middle fork. It was not the best route over the mountains. The Blackfoot River, which Lewis explored on his return journey, was the most direct connection to Lolo Pass and the Clearwater and Snake Rivers leading to the Pacific Ocean.

A mountain pass is a low route through the mountains. They would use Lemhi Pass (7,373 ft elevation) after obtaining horses from the Shoshone, but they had to then go back north through the Beaverhead Mountains (which are part of the Bitterroot Mountain Range) and follow the Bitterroot River to reach Lolo Pass (5,233 ft elevation) in the Bitterroot Mountains.

At Lolo Pass, they would cross over the Continental Divide into Idaho. A Continental Divide is a high point on a continent from which waters flow into the ocean on one side and flow into another ocean (if possible) on the other side. They had been going against the current of the Missouri River since leaving St. Louis in May, 1804. Contrary to popular belief, it is the Missouri River which enters the gulf waters at New Orleans, not the Mississippi. The Mississippi is a tributary of the Missouri River.

Once they crossed over the divide at the Bitterroots, they would be going with river currents all the way to the ocean. A look at the map will clarify their route decisions. Naturally, they hoped to use the Salmon River after going over Lemhi Pass, but the Indians told them it was impossible to navigate. They had to travel back north to reach Lolo Pass and find the rivers leading to the Columbia River and the Pacific.

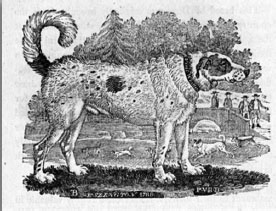

Beaverhead Rock, a National Historic Landmark, resembles a beaver swimming through water. (Photo by Rick Blond)

But this was all in the future. On August 6th, at the forks of the Jefferson (Beaverhead) River, George Shannon got separated while hunting on the Big Hole, but turned up three days later. Since goods had been lost in the boat accident on the Big Hole, and others used up, they decided to leave one small canoe concealed in the cottonwood trees for their return trip. They needed hunters on the ground, not men on the river.

On August 8th, Sacagawea recognized Beaverhead Rock as a landmark, and said the summer camp of the Shoshone was on the other side of the mountains through Lemhi Pass. The next day, Lewis slung his pack on his shoulders and set out with Drouillard, Shields and McNeal to find the Shoshones, vowing he would find them—or some other source for horses—if it took a month. It was “now all important with us to meet with those people as soon as possible.” Clark wrote regretfully that he should have taken this trip, except for the “rageing fury of the tumer on my anckle musle.”473

Lewis followed an Indian road and when he reached the forks of the Beaverhead River he left notes for Clark to camp there. Lewis’s men explored both forks of the Beaverhead, the Red Rock River and Horsetail Creek. The 70 mile Red Rock River, bending towards the east, is the ultimate source of the Missouri River, at Hell Roaring Creek and Brower’s Spring (9,100 ft elevation). Lewis believed Horsetail Creek, going west towards Lemhi Pass, was the source of the Missouri, instead of the Red Rock. The Red Rock River and Horsetail Creek are now part of the Clark Canyon Reservoir. Their confluence became the site of their later “Camp Fortunate.”

On August 11th, as they were following Horsetail Creek towards Lemhi Pass, Lewis saw an Indian on horseback about two miles away coming towards them. He used his spyglass to discover he was dressed in a way unlike he had seen before, riding an “eligant” horse, and concluded he was Shoshone. Lewis continued to walk towards him, and at one mile tried to make contact.

The Indian, however, became alarmed at the sight of Drouillard and Shields approaching Lewis on his path. Lewis tried to signal them to halt. Drouillard saw it and stopped, but Shields didn’t see the signal. Lewis was about 150 paces away, saying in a loud voice, “tab-ba-bone,” which he thought meant “white man.” Instead it meant “stranger.” He was holding trinkets, and rolling up the sleeve of his shirt to show he was a white man, when the Indian suddenly turned around, whipping his horse, and left.

Lewis decided it would be best not to follow him, as they were probably being observed from the hills. So they made a fire and had breakfast. He tied a bundle of assorted gifts to a pole and left it there. When they set out, McNeal carried a pole with a small American flag attached to it.

On August 12th, Lewis wrote they had reached the end of Horsetail Creek, which he called—

the most distant fountains of the waters of the mighty Missouri in surch of which we have spent so many toilsom days and wristless nights. thus far I had accomplished one of these great objects on which my mind had been unalterably fixed for many years, judge then of the pleasure I felt in allying my thirst with this pure and ice cold water which issues from the base of a low mountain…. two miles below McNeal had exultingly stood with a foot on each side of this little rivelut and thanked his god that he had lived to bestride the mighty & heretofore deemed endless Missouri.

They were soon at Lemhi Pass, from which he “discovered immence ranges of high mountains still to the West of us with their tops partially covered with snow.” They began their descent on the western side of the mountain, and when they reached the Lemhi River, Lewis tasted it and declared it was the water of the great Columbia River. 474

The Shoshone summer camp was located on the Lemhi River near today’s Tendoy, Idaho. On August 13th they were following the Indian road when they saw two women, a man and some dogs. Lewis walked alone towards them, holding the flag pole. The Indians disappeared around a hill. Lewis, joined again by his companions, proceeded along the dusty road with twists and turns for another mile, where they suddenly encountered three women. The young woman immediately fled, but the old woman and a girl of about 12 sat down on the ground awaiting their fate and expecting to be killed.

Lewis repeated “ta-ba-bone” and rolled up his sleeve to show his white skin. His face and hands were as dark as their own. He gave them some trinkets—mocassin awls (to punch holes in leather), pewter looking glasses (mirrors), and vermillion face paint. They called to the girl who had fled and she came back to receive her presents. He then painted their cheeks with vermillion, which he had learned from Sacagawea was a sign of peace.

By means of signs, he indicated they wanted to go with them to their camp. Two miles down the road, about 60 mounted warriors on “excellent” horses, came at them at nearly full speed. Lewis left his gun with his men, and holding the flag he went alone to speak with the chief. The chief spoke with the women first, and then gave Lewis his first “national hug.” He put his left arm around Lewis, hugging his back, and his left cheek against Lewis’s cheek, saying “I am much pleased. I am much rejoiced.” in the Shoshone language. 475

They held a pipe council, seated in a circle and passing the pipe around. The Shoshone had a custom of pulling off their mocassins when doing this. Lewis commented that smoking a pipe with a stranger and going “bearfoot” was to indicate they were sincere, because going barefoot in this country was a pretty heavy penalty to pay if they were not sincere. He gave the principal chief, Ca-me-ah-wait, a flag as an emblem of peace and friendship. He later learned the warriors had expected to meet their enemies, the Minatarees of Canada. They were armed with bows, arrows and shields, and three small trade guns.

When they arrived at the camp, they were given an old tipi for their use, and a more elaborate pipe ceremony was held. They had eaten nothing since the evening before, and it wasn’t until late on this evening they were offered dried cakes of serviceberries and chokecherries—the only food the Shoshones had. After dinner Lewis walked to the river and learned from the chief that the Lemhi River did not lead to “the great lake where the white men lived.” He still hoped it wasn’t true. He learned the Shoshone had been attacked by the Minataree of Canada in the spring, and about 20 had been killed or taken prisoner. They had lost a great part of their horses and their leather tipis. They were now living in willow brush huts. He saw enough horses that he thought some could be spared for them, or at least enough to carry their goods across the mountains. Then an Indian called Lewis to his lodge and gave him a small piece of antelope roasted and a piece of fresh salmon roasted. The salmon convinced Lewis they were on their way to the Pacific.

Lewis and his men had to wait four days for Clark and the men to reach the forks of the Beaverhead. Drouillard and Shields were loaned horses and went out on a hunt. Forty to fifty young men would chase the antelopes for half a day, and finally succeed in killing two or three with bows and arrows. Lewis was able to watch most of the chase from his tent. On this day, they didn’t kill any.

Cameahwait gave Lewis a geography lesson, using a stick to draw on the earth and making mountains out of dirt. He explained the Salmon River was impossible to navigate. Lewis didn’t want to believe it. The chief introduced Lewis to an old man who knew the route to the “persed nosed Indians” who lived west of the mountains. The Nez Perce lived on a river which joined other rivers which led to the “stinking lake,” the Pacific Ocean. The old man said the route through the mountains was very bad—there was no game, and they would almost starve to death while crossing the Continental Divide.

Lewis learned the Shoshone traded with the Spanish, whom they could reach by way of the Yellowstone River within ten days. The Spanish, however, would not provide guns and ammunition. This left them at the mercy of their enemies who had guns and ammunition supplied by British traders in Canada. Their enemies would murder all ages and sexes and take their horses. It was for this reason they had retreated into the mountains.

Lewis said they had received promises from the Indians of the Upper Missouri—the Minataree, Mandan and Arikara—they would stop making war on the Shoshone, and the United States would supply the Shoshone with arms and ammunition in abundance, along with articles for their comfort, on reasonable terms in exchange for beaver skins. The chief replied they had long wished to meet white men who traded guns.

The Indians were very reluctant to accompany Lewis to the forks of the Beaverhead. They feared it was a plot by the Minatarees of Canada to kill them. Lewis said he realized they were not acquainted with white men, and hoped there were some men brave enough to accompany him to meet the white men who were arriving at the forks. Cameahwait said he would go and he was not afraid to die. For a third time he “haranged his village” urging them to accompany Lewis. Six or eight men joined him and Lewis smoked a pipe with them and set out before they could change their minds. As they began to travel, others joined them and before long all the men of the village and some of the women were accompanying them.

they were now very cheerfull and gay, and two hours ago they looked as sirly as so many imps of satturn.476

They stopped at Shoshone Cove to camp, and Lewis had the remaining pound of flour cooked in some boiling water for their dinner. Drouillard had been out hunting, but was unsuccessful. The next morning, on August 16th, Drouillard and Shields went out early to find game. Neither the Americans nor Indians had anything to eat. They asked the young Indian hunters to remain in camp to avoid their “hooping and noise” which would alarm the game, but this alarmed the Indians. So two parties of Indians set out to watch the hunters to ensure they weren’t in contact with the Minatarees.

As the main group set out on their march, one Indian arrived whipping his horse to announce that one of the white men had killed a deer. In an instant they all gave their horses the whip and set out to feast on the deer. When Lewis arrived at the site, he found them devouring the raw intestines which Drouillard had discarded. He described them as a “parcel of famished dogs.” He wrote, “I viewed these poor starving divils with pity and compassion” and told McNeal to skin the deer and give 3/4 of it to the Shoshone, who proceeded to eat it “nearly without cooking.” After that, Drouillard killed two more deer which they distributed to the Indians, reserving only a small portion for themselves.

After the deer feed, they were deserted by most of the Indians, and only 28 men and 3 women remained as they approached the Beaverhead, where they would meet Clark. Before arriving, the chief halted their march and gave Lewis and his three companions tippets of fur, such as they themselves wore. A tippet was a fur collar consisting of 100–250 skins of white ermine. Lewis realized it was intended to disguise the white men as Shoshone. Lewis said he was a brown as an Indian himself and wearing an Indian overshirt, so he looked like an Indian with the addition of the tippet. His men followed his example, and they were soon “completely metamorphosed.” Lewis gave his cocked hat with a feather to the chief, and assured him that Clark and his party would be at the forks, or soon arriving.

He had an Indian carry the flag, but when they arrived at the forks, he discovered to his “mortification” that Clark wasn’t there. He feared at any moment the Indians would leave and spread the alarm among other Indian bands, ruining all their chances to obtain horses that season. He now—

determined to restore their confidence cost what it might and gave the Chief my gun and told him that if his enimies wre in those bushes before him he could defend himself with that gun, that for my own part I was not affraid to die, and if I deceived him he might make what uce of the gun he thought proper or in other words he might shoot me. the men also gave their guns to the other indians which seemed to inspire them with more confidence…. I thought of the notes which I had left and directed Drewyer to go with an Indian man and bring them to me which he did.477

Lewis read the notes (which he had earlier written to Clark), and told the chief Clark had sent a man ahead to leave a message saying they should wait for them at the forks. He said he would send one of his men to locate them and the chief should send one of his, which was done. Lewis and the others slept around a campfire that evening. He wrote—

my mind was in reallity quite as gloomy all this evening as the most affrighted indian but I affected cheerfullness to keep the Indians so who were about me… I slept but little as might be well expected, my mind dwelling on the state of the expedition which I have ever held in equal estimation with my own existence, and the fait of which appeared at this moment to depend in a great measure upon the caprice of a few savages who are ever as fickle as the wind.478

On the morning of August 17th, Lewis wrote that Captain Clark arrived with Charbonneau and Sacagawea, who—

proved to be a sister of the chief Camahwait. the meeting of those people was really quite affecting, particularly between Sah-cah-gar-we-ah and an Indian woman who had been taken prisoner at the same time with her, and who had afterwards escaped from the Minatarees and rejoined her nation.479

Clark wrote Sacagawea danced for joy upon seeing her people.

The canoes arrived at noon, and the party was reunited at the place they named “Camp Fortunate.” They held a council and gave out presents and medals, and promised to supply the Shoshone with firearms and other merchandise after they completed their mission to the Pacific. In return they needed horses and a pilot to guide them through the mountains. Clark wrote that Chief Cameahwait was a man of—

Influence, Sence & easey & reserved manners, appears to possess a great deel of Cincerity… everything appeared to astonish those people. the appearance of the men, their arms, the Canoes, the Clothing my black Servent & the Segassity of Capt Lewis’s dog.

The next morning, Clark set out in advance with the Charbonneau family and eleven men to make canoes if the Columbia River (in other words, the Lemhi and Salmon Rivers) proved feasible. They were accompanied by Indians who sang all the way back escorting Sacagawea to the village.

It was August 18th, Lewis’s birthday. He wrote:

This day I completed my thirty first year, and conceived that I had in all human probability now existed about half the period which I am to remain in this Sublunary world. I reflected that I had as yet done but little, very little indeed, to further the happiness of the human race, or to advance the information of the succeeding generation. I viewed with regret the many hours I have spent in indolence, and now soarly feel the want of that information which those hours would have given me had they been judiciously expended. but since they are past and cannot be recalled, I dash from me the gloomy thought and resolved in the future, to redouble my exertions and at least indeavour to promote those two primary objects of human existence, by giving them the aid of that portion of talents which nature and fortune have bestoed on me; or in the future, to live for mankind, as I have heretofore lived for myself.480

Lewis had just experienced the most crucial time of the whole expedition. They absolutely needed to obtain horses from the Shoshone. He had found the Indians to be starving and frightened, and had shown great skill and courage in dealing with them. They were now faced with the daunting prospect of traveling over the Continental Divide to the Pacific Ocean. On his 31st birthday, he fervently wished he was better prepared—intellectually and spiritually—for what lay ahead.

Lewis described the character of the Shoshone—that even in extreme poverty they were gay, fond of gaudy dress, and games of risk. The were frank, communicative, fair and generous, extremely honest and “by no means beggarly.” Each individual acted from the dictates of his own mind. They would only follow the chief if he had their confidence. There were about 100 warriors and about 300 women and children living in the village. They seldom whipped their boys, as it broke their spirit and destroyed their independence of mind. The women did all the routine work. The men hunted and fished and rode the best horses.

Sacagawea was promised in marriage to a man when she was a child. The man was more than twice her age and had two other wives. He said because she had a child with Charbonneau, he did not want her. She was free to leave with her husband.

During the summer months, the Shoshone lived on the waters of the Columbia west of the mountains and fished for salmon. It was a safe place, where their enemies did not come. When the salmon left, they returned to the mountain valleys of the Upper Missouri. In the fall, Shoshone and Flathead bands would join together and enter the plains east of the mountains to hunt for buffalo. They alternated between risking their lives and retreating back into the mountains. The Blackfeet and Minataree would kill them if they encountered them.

The tribe was about to start on their journey to the buffalo country. Cameahwait was deeply concerned about delaying his starving people’s travel to help the expedition. Lewis challenged him to keep his word. The Shoshone women hauled the expedition’s baggage on their backs and on pack horses over Lemhi Pass. One woman gave birth, and was seen carrying her newborn baby along the road. If the women hadn’t carried their baggage, the expedition would not have been able to cross the mountains in the fall of 1805.

Woman power played another role—Sacagawea stayed with the expedition. Pompey was now six months old. Their presence safeguarded their encounters with Indians, and it must have helped greatly with the morale of the men. The presence of a woman, baby and dog were a welcome reminder of home and a distraction from their own troubles.

The Shoshone lacked horses and mules because of the Minataree raid. Lewis said their mules were the finest he had ever seen, and when Clark set out to explore the river route, he traded a waistcoat for a mule. Tobe (“Toby”), an elderly Shoshone chief, was Clark’s guide as they explored the area of the Salmon River for four days (August 21–24, 1805). Clark discovered the Salmon River was indeed impassible, and saw in the distance the loftiest mountains he had ever seen, entirely covered with snow.

Tobe would guide the expedition north through the mountains to Lolo Pass, and then west through the pass to the Nez Perce villages on the Clearwater River. On the 31st of August, they begin their journey over the mountains with 29 horses and one mule. It would take over three weeks to reach the Nez Perce.

“Lewis and Clark Meeting the Flatheads at Ross’ Hole, September 5, 1805,” a 12 x 26 foot mural by Charlie Russell at the Montana State Capitol in Helena. (Wikimedia Commons)

On September 4th they encountered the Flathead, or Salish Indians. The Flatheads of the Bitterroot Valley did not have flattened heads. Their name came from the Coastal Salish, who lived near the ocean and who flattened the heads of their infants by binding their foreheads in cradleboards. A sloping, pointed head was considered attractive.

Patrick Gass wrote “They are the whitest Indians I ever saw.” They wondered if the Flatheads might be the fabled Welsh Indians. They spoke a guttural, harsh-sounding language unlike any Indian language they had heard. Whitehouse said they spoke with a “burr” or speech impediment, and wrote—

we take these Savages to be the Welch Indians, if their be any Such from the Language. So Capt. Lewis took down the Names of everrything in their language …

The translation chain involved five people—Salish to Shoshone by Tobe; Shoshone to Hidatsa by Sacagawea; Hidatsa to French by Charbonneau; and French to English by Labiche. There were at least seven people engaged in making the vocabulary, counting Lewis and the Salish language speakers.481

The Flatheads had lived in the Bitterroot Valley for thousands of years. Their oral history dates back to the end of the last Ice Age. Their history of Lewis and Clark relates they felt pity for them because they were white and had beards. They were the first white people they had ever seen. Because York had black skin they thought they were a war party, as warriors painted themselves black. Their hair was cut short, a sign of mourning among Indians. They had never seen men wear pants, and they gave them buffalo robes because they were men without blankets.482

Clark wrote they possessed “ellegant horses.” They traded for eleven horses and exchanged seven more. The tribe consisted of about 400 people, with 80 warriors. They had about 500 horses and were on their way to hunt buffalo when the expedition left on September 6th. The expedition now had 40 pack horses, and three colts which they intended to eat when they ran short of provisions.

They named the Salmon River for Lewis and the Bitterroot River for Clark. Neither name has endured, except for the river they named the Clark Fork River, thinking it was a fork of the Clark (Bitterroot) River. In fact, the Clark Fork River was a tributary of the Columbia River, with The Clark Fork’s own tributaries being the Bitterroot, Blackfoot and Flathead Rivers. Tobe told them the Clark Fork would take them east over the route of today’s Interstate 90 through Hell’s Gate Canyon to the Three Forks Headwaters. Both the Clark Fork and Blackfoot Rivers were much easier routes through the mountains, but they were also prime territory for Blackfoot ambushes.

They arrived at a creek they named “Traveler’s Rest” in the Bitterroot River Valley near Lolo Pass on September 9th, where they rested for a day and made lat-long readings. They would travel 120 miles west through the Pass, over steep and rugged terrain, during the next 16 days.

On the morning of September 13th, Lewis’s horse ran away with her colt. The colt was being used by Tobe’s son. The horse and colt were never located. They visited the famous Lolo Hot Springs on the 13th, but didn’t have time for a hot bath.

Tobe chose the wrong trail among several trails at the springs, and they descended into the valley of the Lochsa River near today’s Powell Ranger Station, where they killed a colt and ate it. The main trail followed the mountain ridges. On September 15th, they climbed back over 3,000 feet to camp on Wendover Ridge (6,692 ft. elevation).483 Several horses slipped and rolled down the mountains. Clark’s writing desk was broken, but the horse survived unhurt. They melted snow to drink and cooked the remaining horseflesh to eat.

It began to snow on September 16th, and 6–8 inches of snow fell during the day. Clark wrote:

… we are continually covered with Snow, I have been wet and as cold in every part as I ever was in my life, indeed I was at one time fearfull my feet would freeze in the thin mockersons which I wore.484

On the 18th they decided that Clark should take six hunters and go on ahead to hunt on level ground.

Lewis and the rest of the party dined on a “skant proportion of portable soupe” of which they still had a few cannisters. They also had a little bear oil and about 20 pounds of candles. They had been eating portable soup twice a day since the 14th. Lewis had purchased 193 pounds of the soup in Philadelphia, packed in 32 tin cannisters. The “portable soup” was a chunk of concentrated beef stock to be heated in water. Its nutritional content was about 360 calories per serving. On September 19th, the remaining soup would run out in two days. Tallow candles were a high calorie fat, as was bear oil. Research has revealed they did not eat their candles, instead they used about one candle a day to write by candlelight. Lewis mentioned them only as a last resort. Their average daily caloric intake on a working day would have been about six pounds of meat (about 5,100 calories.)485

Clark and his men killed a horse which they found on September 19th. After breakfasting on their portion, they left the rest for Lewis and his party, who on the next day, “ate a hearty meal … much to the comfort of our hungry stomachs.” Clark, on September 20th, met up with three Nez Perce boys after arriving at a level open plain, the Weippe (“WEE-eyep”) Prairie of the Nez Perce village.

The arrival of Clark and his hunters caused “great confusion” at the Indian camp. About 100 men, women and children accompanied them back to their village, located about two miles away. They passed fields of camas roots being harvested and gathered in heaps. Camas (“Quamash”) roots are small onion-like bulbs, tasting something like baked sweet potato. After being roasted in deep earth pits they could be pounded into flour, or raw bulbs could be boiled. It was a main food of the Nez Perce. Their other main food was dried salmon.

The camp consisted mostly of women and children because three days earlier, the Nez Perce warriors had ridden off to make war against the Lemhi Shoshone. The Shoshone had recently killed three peace emissaries sent by the Nez Perce. Most of the able bodied men were away. The Nez Perce, contrary to their name, “pierced noses,” did not routinely wear ornaments in their noses, but Clark does record one young woman doing this.

The boys who met Clark remembered their first impressions. He had red hair, a red beard covering his face, and a red braid hanging down the back of his neck. His hands were covered with red hairs. He wore a strange head dress on top of his head. All of the men had different colored hair and hair on their faces like buffalo hair. They wore clothes made of cloth and skin and their horses were skinny. On their saddles they carried “sticks-that-shoot-black-sand-with-thunder.” Others described some men as “upside down men” because they had hair on their chins and none on their heads. Five teenagers tackled York when he was alone and scrubbed his skin until he bled to determined whether his skin was really black. The men with buffalo hair on their faces, when they met the men of the tribe, put their right hand in the right hand of the man and moved it up and down. The captain’s dog followed behind him and was as big as a black bear. These are some of the Nez Perce stories handed down and found in two fine books, Do Them No Harm! and Lewis and Clark Among the Nez Perce.486

Upon their arrival, Clark and his men ate heartily of dried salmon and camas roots and then suffered from diarrhea and abdominal cramping. When Lewis and his men arrived on the 22nd, Lewis became seriously ill. He was “Scercely able to ride” on the 24th. Several men were so unwell they just lay on the side of the road. On the 29th Clark wrote that Lewis was still very sick and most of the men were “complaining very much of ther bowels & Stomach.” On October 4th, Lewis was able to “walk about a little.” The Corps of Discovery finally set out for the coast on October 7th, while Lewis was still recuperating.

Clark was pretty much in charge throughout this stay because Lewis was so ill. Clark was giving Dr. Rush’s Bilious Pills—laxatives called “Thunderbolts”—to the men and also cathartic salts to induce vomiting. Dr. David Peck in his book, Or Perish in the Attempt, says it is “unclear whether the men were more sick from the diet or from the medical treatment.” He writes the sun-dried salmon could have harbored Staphyloccucus bacteria causing food poisoning, and the fish could have been carrying tapeworms and other worms inducing peritonitis.487

They were with the Nez Perce for 17 days. At first, the Indians considered killing them. As sick as they were, it would have been easy to do. An old Nez Perce woman, Wat-ku-ese. who had known white men in her youth, saved their lives. As a girl, she had been captured by the Blackfeet and was eventually sold to a white trader living in the Great Lakes area. He treated her well, and they had a son together. He wanted to take her and the baby across the “Big Water” back to his home, but she fled with the baby back to her homelands. The child died along the way. Now, when she heard them plotting to kill the men of the expedition, she told them:

These men are So-yap-pos! [white men] Good men! Men like these were good to me. Do not kill them! Do them no harm! Do them no harm! 488

These words lived on in the stories and councils of the Nez Perce, who entered into a formal alliance with the United States on May 12th, 1806 when the corps returned to the villages.

The Nez Perce had acquired six guns in trade with the Minataree of the Missouri (Hidatsa), but they no longer had any ammunition. They may have been trading at the Mandan-Hidatsa villages while Lewis and Clark were there. A hatchet made by John Shields preceded the corps’s arrival at the Nez Perce villages. The tribe may have sent peace emissaries to the Shoshone in response to the United States’s message of peace between tribes. It would be to the advantage of the Shoshone, Flatheads and Nez Perce if they stopped making war against each other, and instead concentrated on their mutual defense against the Blackfeet and Minataree of Fort de Prairie in Canada. 489

From September 26th until their departure on October 7th, they were busy making five dugout canoes and oars at “Canoe Camp” on the Clearwater River west of Weippe Prairie. The Nez Perce showed them how to use fire to hollow out the center of the giant Ponderosa Pines they cut down, which speeded up the work. They made four large canoes, as long as 50 feet in length, and a small canoe which would serve as lead canoe. Several men were unable to work at all, and the rest were so “weak and feeble” that the work proceeded slowly. The Indians helped them.

The 38 horses and one mule were branded using a “stirrup iron” and a piece of hair was cut off of their forelocks. The herd was left in the safekeeping of Chief Twisted Hair’s family. Twisted Hair and his younger brother, Tetoharsky, would act as the expedition’s guides to Celilo Falls on the Columbia River.490

The war party against the Shoshone returned, but only Patrick Gass mentioned it in his journal, noting the captains gave out medals to 3 or 4 chiefs. Any victory celebrations would have been held at another village. It was obviously not politic to celebrate in front of Americans, with their message of peace, and the presence of their Shoshone guides, old Tobe and his son.

On the second day after their departure from Canoe Camp, they were joined by the two Nez Perce chiefs who had gone ahead to another village without telling them. After they were safely in the care of their new guides, Tobe and his son left without saying goodby or receiving his pay. When the captains asked Twisted Hair to send a messenger after them with Tobe’s pay, the chief advised against it, saying “his nation would take his things from him before he passed their camps.” 491

In order to understand the corps’s different relationships with the tribes they encountered, geopolitics has to be considered. A primary goal of the United States was to enter into the fur trade of the Upper Missouri. The Upper Missouri trade had already been established by British traders in Canada who supplied the Indians with guns and other articles in exchange for furs. The Teton Sioux dominated the region between the Yellowstone and Platte tributaries of the Missouri. They simply were more numerous, and used force to obtain what they wanted. But all the tribes had guns supplied by the British. The Mandan-Hidatsa villages were the major trade center for the northern plains.

The Blackfeet and the Minataree of Fort de Prairie in Canada had been supplied with guns by traders on the Saskatchewan River since the 1750’s, and they terrorized the tribes who had no guns. This was the balance of power that Lewis was proposing to correct by supplying the Shoshone, Flatheads and Nez Perce with guns and ammunition. The mountain tribes traded for horses with the Spanish in the Southwest, but the Spanish would not trade for guns. The situation was particularly awful because there were literally millions of buffalo on the Great Plains. The Blackfeet and Minataree (Gros Ventre) were representing British interests and protecting their special trade relationship. But the consequences were that the Shoshone, Flatheads and Nez Perce hunted with bows and arrows and lived in near starvation for many months of the year out of fear of enemy attacks.

Entering into the fur trade of the Upper Missouri had a larger, global, geopolitical significance for the United States. It meant the establishment of a world wide trading empire. Jefferson’s instructions to Lewis said:

Should you reach the Pacific Ocean inform yourself of the circumstances which may decide whether the furs of those parts may not be collected as advantageously at the head of the Missouri (convenient as is supposed to the waters of the Colorado & Oregan or Columbia) as at Nootka sound, or any other point on that coast; and that trade be consequently conducted through the Missouri & U.S. more beneficially than the circumnavigation now practised.492

In other words, Jefferson proposed collecting furs on the Upper Missouri and bringing them through the mountains to the mouth of the Columbia River to be shipped to China, and then bringing articles from China back to the United States by transporting them on the Missouri River.

Captain Robert Gray, who discovered the mouth of the Columbia in 1792, was the captain of the first American ship to circumnavigate the globe in 1790. His ship, the Columbia, traveled almost 42,000 miles after leaving Boston harbor in 1787. The Columbia delivered furs from the Pacific Northwest to China and brought back almost 22,000 pounds of tea to Boston. It was the beginning of the Boston triangular trade with the Pacific Northwest. Articles from Boston were traded to coastal Indians for sea otter pelts and seal fur skins, which were then traded in China for silks, porcelain and tea, and the Chinese goods were brought back to Boston to be sold.

In 1801, of the 23 ships which sailed to the Northwest Coast, 21 were American, 2 were British, and 1 was Russian. The coastal Indians called all Americans “Boston Men.” Profits ranged between 300 to 500%, and went as as high as 2,200%. Nearly18,000 otter and seal pelts were carried to Canton annually until the animals were almost extinct by the 1830’s.493

Immediately upon his return to St. Louis, Lewis wrote to Jefferson on September 23, 1806 about the possibilities of the fur trade:

The Missouri and all it’s branches from the Cheyenne upwards abound more in beaver and Common Otter, than any other streams on earth … The furs of all this immence tract of country … may be conveyed to the mouth of the Columbia by the 1st of August in each year and from thence be shiped to, and arrive in Canton earlier than the furs at present shiped from Montreal annually arrive in London.494

He proposed that a fort be built at the mouth of the Columbia for the purpose of collecting furs. An American trading fort was subsequently built at Astoria near the mouth of the Columbia by John Jacob Astor’s Pacific Fur Company in 1811, but the enterprise was halted by the War of 1812.

The contest between the United States and Great Britain for control of the Pacific Northwest would go on for many years, and would not be resolved until the Oregon Treaty was signed in 1846. This treaty set the boundary line between the United States and Canada at the 49th parallel, with the exception of Vancouver Island being retained by the British.

There were three territorial missions for Captain Lewis and his army Corps of Volunteers for Northwest Discovery—

(1) to find a navigable water route from the Missouri to the Columbia and Pacific Ocean. Regardless of whether an all-water route was discovered, it was necessary to establish a fort at the mouth of the Columbia in order to reinforce the United States’ claim to the Pacific Northwest under the Doctrine of Discovery.

(2) to determine the source of the headwaters of the Missouri, which would be used to establish America’s claim to the northern boundary of the Louisiana Purchase.

(3) to see how far a tributary river of the Missouri flowed down from the north, as the latitude of that river could be used to determine the boundary line between the United States and Canada. If Lewis had followed the Milk River instead of the Marias, the United States might have gained 17 additional miles.495

The expansion of the fur trade into the Upper Missouri and the building of trading forts were necessary to secure America’s continental empire. For this reason, Lewis was determined to break the hold that Britain’s Indian allies had over the region. There were enormous commercial profits to be made, but the underlying issue was America’s Manifest Destiny. The support of the Shoshone, Flatheads and Nez Perce was needed against the Indians supported by the British. The Montana buffalo plains and rivers teeming with beaver and otter were the scene of conflicts between Americans and Indian allies of British traders for many years to come.

Another picture of a Newfoundland, from Thomas Bewick’s A General History of Quadrupeds (1800). Discovering Lewis and Clark website, www.lewis-clark.org

The expedition was now traveling with river currents instead of against them. They would arrive at the Pacific Ocean on November 18th, after a journey of 500 miles from Canoe Camp. Traveling on the Clearwater and Snake Rivers, they reached the Columbia River on October 18th.

They were buying dried salmon and dogs to eat from the natives, whose fishing camps lined the river shores. Clark and the Nez Perce chiefs were the only ones who didn’t like to eat dogs. He said all the rest of the party had a great advantage as they “relished the flesh of dogs.” According to journal entries, the expedition ate 193 dogs. The salmon weren’t counted. Journal entries total 1,048 deer, 382 elk, 259 buffalo, 28 bear, and 111 beaver among the animals killed and eaten.496 The slaughter of animals to eat was a major occupation of the corps. Seaman must have taken it for granted.

They were being observed by Indians all along the Columbia River Plateau, who lined the shores watching the passing of their canoes. Clark wrote

“the woman of Shabono our interpetr we find reconsiles all the Indians as to our friendly intentions a woman with a party of men is a token of peace.” 497

They were taking chances on the river because the season was so far advanced and they were unwilling to take the time to portage around the falls and rapids. On October 14th, they had a canoe accident at a rapids on the Snake in which they lost all the roots acquired from the Nez Perce and half of their goods. They had been following a strict rule of taking nothing from the Indians without permission—stores of dried fish and firewood were left untouched—but now they took firewood found on an island to dry out their remaining goods.

On October 16th, at the confluence of the Snake and Columbia, 200 men of the Wanapum tribe came to their camp drumming, singing, and dancing to greet them. The Nez Perce chiefs had gone ahead to prepare the way. The Wanapam were one of the Sahaptin language speaking tribes who lived along the Snake and Columbia Rivers—now known as the Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation. They met the Yakama tribe at the confluence of the Yakima and Columbia Rivers. Lewis took a vocabulary, and held a council on the 18th. On the 19th, they met with the great chief of all their tribes, the Walla Walla Chief Yel-lep-pit, who urged them to stay so his tribe could meet them. They promised on their return trip to stay a day or two, but now they were in a hurry to reach the coast.

They were catching occasional glimpses of Mount Hood in the distance, the highest volcano in the Cascade Mountain Range at 11,000 feet. They were leaving the treeless region of the Columbia Plateau, a lava plain of basaltic rock created by the eruption of ancient volcanoes, to enter the mountain ranges of the Pacific Northwest.

Clark wrote that John Collins made “Some verry good beer” out of the last of the camas root bread that had become “wet molded & Sowered.” It must not have been a very great quantity, because none of the other journal keepers mention beer.498

Indians fishing at Celilo Falls in the 1950’s, before The Dalles dam was built. (Wikimedia Commons)

On October 22nd they reached Celilo Falls and hired Indians to take their heavy articles around the falls by horseback. The Celilo Falls, inhabited for at least 11,000 years, was the oldest continuously inhabited settlement in North America until The Dalles Dam destroyed it in 1957. The waterfalls stretched for about 12 miles. Historically, an estimated 15–20 million salmon passed through the falls every year, making it one of the great fishing sites on the continent.

The villages at the falls were the great trading mart of the West Coast. The expedition arrived late in the season after the trading fair was almost over. At its peak, 3,000 Indians would be in attendance. The Nez Perce brought horses, buffalo meat, and skin clothing from the mountains. The Chinooks brought European goods from coastal traders and wapato roots. The locals supplied dried salmon, roots and berries.499

Every man of the expedition stripped naked to portage the canoes around Celilo Falls, in order to brush fleas off of their legs and bodies as they carried the canoes. While on the water they were not bothered by fleas, but on land the fleas, which were part of the salmon industry, were as bad as the dreaded mosquitoes and gnats of the plains.

At the end of the portage day, Twisted Hair, the Nez Perce chief, informed them they had learned the Chinook Indians below the falls were plotting to kill the Americans. They put their arms in order and prepared a 100 rounds of ammunition. On the same day, Lewis traded the small lead canoe for a beautiful Chinook canoe, wide in the middle, tapering at both ends, and decorated with carved figures. The next day, the Nez Perce chiefs said they were at war with the Chinook, who would kill them if they continued. The captains persuaded them to stay two more days, in the hopes of brokering a peace for them.

They had to take the boats through the Short and the Long Narrows. The series of falls were among the largest in North America, dropping 82 feet at high water over the course of 12 miles. The Columbia River, a mile wide on the plateau, was confined to narrow gorges, creating turbulent, boiling whirlpools. Clark wrote that the Short Narrows squeezed down to 45 yards wide and that he—

thought (as also our principal watermen Peter Crusat) by good Stearing we could pass down Safe, accordingly I deturmined to pass through this place not withstanding the horrid appearance of this agitated gut Swelling, boiling & whorling in every direction (which from the top of the rock did not appear as bad as when I was in it) however we passed Safe to the astonishment of all the Inds of the last Lodges who viewed us from the top of the rock.500

The men portaged the guns and papers and other valuables around the narrows, and the best swimmers and watermen handled the boats. It wasn’t possible to portage the large canoes.

The plank houses of the Chinooks were the first wood houses they had seen since leaving the St. Louis area. Scaffolds outside the houses contained dried, pounded, salmon wrapped in reed packaging. Clark counted 107 packages and estimated their weight at 10,000 pounds. They held a council between the chiefs of the Wishram and Wasco villages and the Nez Perce chiefs and arranged a peace. The natives were delighted when Cruzatte played the violin and the men danced in the evening.

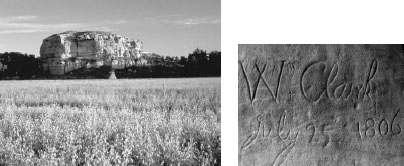

On October 25–27, they camped at Fort Rock, an ancient fortification overlooking the Dalles. Archeological investigations have found evidence of tools and campfires going back 10,000–13,000 years; and seventy five sandals were discovered here dating back 9,000 years. Clark wrote about Fort Rock—

our Situation well Calculated to defend (us) our Selves from any designs of the natives, Should They be enclined to attack us.501

Fort Rock is one of the few places we know for certain that the expedition camped. A riverfront trail and signage mark the site, the most historic Lewis and Clark campsite in the country.

The two chiefs of the Nez Perce left the party. They had served the Corps of Discovery for five weeks, since the making of the canoes at Canoe Camp, and had done what they promised, guiding the expedition through the lands of the Sahaptin peoples to The Dalles. The Nez Perce spoke a Sahaptin language, and after the falls, the Chinooks had their own language.

They were now meeting the Coastal Salish, the people who really did flatten their heads. They spoke with the same “clicking tone” as the Flatheads of the Bitterroot Valley. Lewis took a Chinookan vocabulary at the Wishram village. They may have also been encountering the “Chinook Jargon,” of coastal Indians. Clark wrote “maney words of those people are the Same.”

People who speak different languages often develop a simplifed version of one of the languages, mixed in with words from different languages, which is called “pidgin” or “jargon.” Members of the corps most likely used some variations of English and French pidgins themselves. Different languages played a part in the daily life of the corps. They were a traveling group of linguists engaging in trade with all the people they encountered.

Pacific Northwest Indian canoe (Wikimedia Commons). The canoes they saw had carved figurines in the bow and stern, as tall as five feet in height.

They were finding brass tea kettles in the Chinook homes. The Indians were friendly. They passed “Sepulchar Island,” where their dead were buried in vaults. They were now in the Columbia Gorge, a land of mountains and timber, of clouds, mist and rain, and of cascading waterfalls.

On October 31st they observed their first tidal waters at Beacon Rock, an 848 foot landmark named by Lewis and Clark. The massive rock made out of basalt was purchased by Henry Biddle, a descendant of the Philadelphia Biddles, who donated it to the state of Oregon. A 3/4 mile hiking trail lead to its top today.

They passed the “Great Shute” or rapids of the Cascades, where the river dropped forty feet in two miles. (The Bonneville Dam was built to control the Cascades in 1938.) They portaged their baggage around the Cascades, and moved the four large canoes through the rapids by sliding them on poles placed across rocks in the water. Three of the canoes were damaged and had to be repaired.

They were encountering Indians who had heads flattened to a point and pierced noses with white shells pushed through their noses—genuine flathead and pierced nose people. They were sharp traders who said they could get better prices from white people on the coast. They prized blue and white beads most of all. The Indian men were dressed in sailor’s jackets, trousers, shirts and hats. They were having trouble with Indians stealing things.

The weather was cool, wet, rainy, and foggy. These conditions would continue for months to come. On November 7th they were traveling through the Columbia estuary, when Clark wrote “Great joy in camp we are in View of the Ocian.” An estuary, however, is the transition area between fresh water rivers and the saltwater of an ocean. They wouldn’t reach the ocean until November 18th, but they were feeling the effects of the ocean.

Several of the men got sea sick from the high waves that came in with the tide. The winds blew hard, and driftwood trees were being tossed about in the water. Many of the trees were 200 feet long and 4–7 feet through. They managed to get the canoes out of the water and unloaded. It rained day and night, but all were cheerful, anticipating reaching the coast.

The waves were so high, however, that on November 10th they were forced to take refuge in a small cove that Clark called “this dismal nitch” on the north side of the river. They formed a camp on top of the giant drift logs and stored their goods in the rocks above tide water. He wrote on November 11th:

… we are all wet as usial and our Situation is truly a disagreeable one; the great quantites of rain which has loosened the Stones on the hill Sides, and the Small Stones fall down upon us, our canoes at one place at the mercy of the waves, our baggage in another and our Selves and party Scattered on floating logs and Such dry Spots as can be found on the hill Sides, and Crivices of the rocks.

They stayed at Dismal Nitch for six days (November 10–15). They were miserable. It was wet and cold, their bedding was wet, and their skin clothes were rotting. It rained continually. While they were there, the natives came by in their canoes and sold them salmon. The Indians traveled across the five mile wide river in the highest waves Clark had ever seen. He wrote, “Certain it is they are the best canoe navigators I ever Saw.” 502

Three of the men used their Indian canoe and entered a bay of water with a sandy beach near the ocean. A Chinook Indian village was located there, and the Indians were “thievous.” Shannon and Willard had their guns stolen while they were sleeping, but when Captain Lewis and a second exploring party arrived they got their guns back. Finally the rain stopped and the expedition’s camp was moved to a point of land at the east entrance to the bay (Baker Bay, Ilwaco, Washington). Cape Disappointment was on the west side of the bay, on the ocean.

On November 17th Lewis and his men went around Cape Disappointment to enter the ocean waters. Cape Disappointment was named by an Englishman in 1788 when he was disappointed in not finding the Columbia River. He didn’t realize that the 700 foot tall promontory of land was actually the north side of the entrance to the river. Four years later, the American ship captain Robert Gray managed to get through the Columbia River Bar and enter the river, claiming it for the United States. The bar is a treacherous place, six miles long and three miles wide, where wind, waves and current have destroyed over 2,000 vessels since 1792, giving it the name “the Graveyard of the Pacific.”

On November 18th, the captains and several of the men marked their names and the date with the words “by land 1804 & 1805” on the soft basalt rock of Cape Disappointment. On November 20th, they met with two Chinook Chiefs and gave them medals and a flag. The saw the most beautiful fur they had ever seen, a robe made out of sea otter skins. After much bartering, they persuaded Sacagawea to relinquish her belt of blue beads so they could obtain the robe. In return, they gave her a coat of blue cloth.

They were visited by natives in the evening, with women eager to “gratify the passions of the men.” The women were tatooed, and one had “J. Bowmon” on her arm. Ribbons were distributed to the men, rather than have knives and more valuable articles given to their “favorite lasses.” There was evidence of venereal disease, scabs and ulcers, among the group that accompanied the girls. A few days before they started on their return journey in March, 1806, Lewis forbade the men to have sex with women who came to the fort, because it was the same group—

that had communicated the venerial to so many of our party in November last. and of which they have finally recovered.503

Fort Clatsop replica, Lewis and Clark National Historial Park, Astoria, Oregon (Photo by Rick Blond).

On November 24th, the captains asked the members of the party to vote as to where they should spend the winter. Everyone except the captains and the baby cast a vote. “Janey”—Clark’s name for Sacagawea—voted in favor of a place in which there were plenty of wapatos (Indian potatoes). York voted in favor of examining the other side of the river. The majority opinion was to go take a look at the south side of the river where the Clatsop Indians had told them there was plenty of game. Other alternatives were to go back to Celilo Falls, or to the confluence of the Sandy River near Mount Hood. If the south side of the coast wasn’t suitable, they would go back to the Sandy.

It was “truly disagreeable” weather after they crossed over to the south side. Their tents, tipi, sails, bedding and clothing were rotting. They were continually wet and there were violent winds and rain. They were exploring the coastal area, looking for game. On December 2nd they killed an elk, the first since the Rocky Mountains. They discovered there were plenty of elk and deer and Lewis found a location to built a fort. On December 10th they started cutting down trees to built Fort Clatsop. By Christmas Eve, on December 24th, they were moving into their huts. On Christmas morning, they were awakened by a “Shout and a Song” and presents were given out after breakfast—tobacco to the men who smoked, and handkerchiefs to the others. Dinner consisted of some poor elk boiled, spoiled pounded salmon and a few roots. Their blankets were infested with fleas and the huts were filled with smoke, but they were living under a roof.

On the 27th, they set up a salt making camp at the ocean, 15 miles to the southwest. The Salt Works consisted of five kettles of ocean water boiling 24 hours a day to extract the salt from the water. Salt was necessary to preserve the meat from spoiling and for use as flavoring. For the next two months, three men tended to the salt works, producing about 20 gallons of salt. 12 gallons were put in small kegs to be used on the return journey.

Lewis resumed writing in his journal on January 1st, 1806. He abandoned writing at the Nez Perce village after he became ill, and made only a few notes in the weather records after that. On January 1st, the captains issued orders for the fort. They were concerned about safety—a sentinel was to keep watch day and night for the approach of any Indians, and a sergeant and three privates were on guard duty day and night. The natives were to be treated in a friendly manner, but the sergeant could expel any native who became troublesome. No Indians could remain in the fort after sunset and the main gate was to be locked. All tools were to be kept in the room of the commanding officers, and brought back the moment they were not being used. Only John Shields, the gunsmith, was exempt from tool regulations.

Lewis described the bargaining methods of the locals, calling them “great higlers in trade.” They always refused the first offer. He tested his theory by offering a lot of merchandise for an inferior otter skin. The seller refused, but the next day accepted a much smaller amount of merchandise for the same skin. He found them different from all other Indians he had ever dealt with, as they would trade for anything that caught their fancy.

It would appear to be a cultural conflict. The Indians were long accustomed to bargaining with white traders in the otter skin trade. They didn’t understand white men who came on an exploring expedition—white men who were hungry, and who lacked merchandise. Bargaining was a sport, and theft was a game. They would spend a whole day bargaining over a handful of roots, and steal small things if they had the opportunity.504

Two men who had helped carry kettles and supplies to the salt works returned with the news that a dead whale had washed up on the beach, and brought back some of its blubber meat. It was white and spongey, resembling the flavor of beaver and dog meat. They also brought back the first salt that had been made, which was a “great treat” for Lewis and most of the party, except for Clark who didn’t care about salt. Lewis wrote about eating all kinds of food on the expedition—

I have learned to think that if the chord be sufficiently strong, which binds the soul and boddy together, it dose not so much matter about the materials which compose it.505

Lewis had dined at Jefferson’s table for two and a half years, and now he was eating roots and spoiled salmon.

The next morning Clark set out with a party of 13 men and Sacagawea and 11 month old Jean-Baptiste in two canoes to see the whale. Lewis wrote that Sacagawea had complained—

she had traveled a long way with us to see the great waters, and that the monstrous fish was also to be seen, she thought it very hard she could not be permitted to see either (she had never yet been to the ocean).506

When the party finally reached the whale, they found it was entirely stripped of its “valuable parts.” It measured 105 feet. They went to the Tillamook village where the blubber was being boiled down for its oil. Trading all the merchandise they brought with them, they were able to obtain 300 pounds of blubber and a few gallons of oil.

On their way back to Fort Clatsop, they stopped at a small Chinook village to spend the night. At 10 o’clock in the evening, Clark heard screams. His local guide said someone’s throat had been cut. Hugh McNeal had gone by himself to visit a Chinook woman, “an old friend,” without telling anyone. Other Indians, who pretended friendship, planned to kill him for his blanket and clothes. His woman friend learned of the plot and started screaming for help, scaring off his attackers. Clark sent out four men to investigate, who met McNeal coming back in haste. McNeal was simply puzzled about what had happened until he learned of the plot.

Lewis wrote that the traders visiting the coast must be either English or American. The Indians knew many words of English:

musquit, powder, shot, nife, file, damned rascal, sun of a bitch, etc.

He was grateful the traders had not introduced any “sperituous liquors,” as the locals never asked for it, calling it a “very fortunate occurrence” for the natives as well as the “quiet and safety of thos whites who visit them.” 507

They lost their prized Chinook canoe. Some of the men were negligent in tying it up after using it. It was so light that four men could carry it a mile without resting. It could hold four men and 1,000–1 200 pounds of goods. They lost a large pirogue, when a tie rope broke, but fortunately it was recovered. As a precaution, they drew three of the large boats out of the water, and secured the fourth with a strong rope of elk skin.

Drouillard killed seven elk in one day. Lewis said he didn’t know how they could survive without his skill as a hunter. They dried (jerked) the meat so as to ensure the supplies would last. Otherwise, the men would eat too much when they had the chance. They used the last of their candles on January 13th, but they had candle molds and wicks, so they made new candles out of rendered elk fat.

There was “nothing worthy of notice” on many days in the journal entries. The men filled their time with hunting and making skin clothes and mocassins. Lewis wrote many pages on the Indian way of life, scientific observations, and suggestions for trade. Clark worked on maps and drawings and copied Lewis’s journal entries almost verbatim. The captains wrote two lengthy reports—an Estimate of Distances from Fort Mandan to the Pacific Coast and an Estimate of Western Indians, which was less detailed than the Estimate of Eastern Indians.

They were anxious to start the return journey, but it would be “madness” to start out before the first of April, because the snow was deep on the Columbian Plains until then and timber for firewood would be hard to find. The Nez Perce had warned them that snow was 20 foot deep in the Rocky Mountains until the first of June.

As they prepared to leave in March, Lewis praised the work of John Shields, saying that except for his skill in repairing guns, most of their guns would be entirely unfit for use. Lewis had ordered extra gun parts at Harpers Ferry, and his idea to put the gun powder in lead kegs had managed to keep their powder dry. Each lead keg contained 4 pounds of gun powder, and 8 pounds of lead when it was melted down to make bullets. They had an “abundant stock” of ammunition for the return journey, and they always took the precaution to divide the lead cannisters between the canoes. Guns and ammunition were all they had for subsistence and defense for their journey of over 4,000 miles back to St. Louis. 509

On March 17th, Lewis wrote that—despite the “winning graces” of the girls brought to the fort by their old “baud” who were camping nearby and laying “sege” to the fort—the men were living up to their promise not to engage in sex. They did not want to deal with venereal disease on their return journey.

He wrote the weather was so uncertain they were going to start on their return journey whenever the weather broke. It had rained almost every day of the 141 days they spent at Fort Clatsop. Only 12 days were without rain.511

Drouillard had traded Lewis’s uniformed laced coat and nearly half a carrot of tobacco (a carrot was 3 pounds of tobacco) for a canoe at the Cathlamet village. Lewis wrote he thought his uniform coat should be replaced by the U’ States as it was but “little woarn.”

The Clatsops refused to part with any canoe, for the small amount of merchandise they had left. Lewis decided to take a canoe from the Clatsops, “in lue of the six elk which they stole from us in the winter.” Lewis wrote about their merchandise—

… two handkercheifs would now contain all the small articles of merchandize which we possess; the ballance of the stock conists of 6 blue robes one scarlet do.[ditto meaning robe] one uniform artillerist’s coat and hat, five robes made of our large flag, and a few old cloaths trimmed with ribbon. on this stock we have wholy to depend for the purchase of horses and such portion of our subsistence from the Indians as it will be in our power to obtain. a scant dependence indeed, for a tour of the distance of that before us.512

Lewis left a list of all of their names with the Chinook chief who accompanied his wife and their “female band.” The statement was a proclamation announcing they had been sent out by the government of the U’ States in May, 1804 to explore the interior of the continent. They had reached the mouth of the Columbia River on November 14, 1805, and they were departing on___day of March, 1806 to return to the United States. They made multiple copies of the proclamation to distribute and added sketches of their route. He wrote:

… our party are also too small to think of leaving any of them to return to the U” States by sea, particularly as we shall be necessarily divided into three of four parties on our return in order to accomplish the objectives we have in view. 513

They gave Fort Clatsop and their furniture to the Clatsop chief Coboway, who had been “much more kind and hospitable to us than any other indian in this neighborhood,” and left the fort on March 23rd, homeward bound.514

They had two canoes and three pirogues to paddle against the Columbia River’s strong current, which was made more intense by the spring snow melt. After they arrived at the village of a Chinookan tribe at the Great Cascades, Lewis characterized them as the “greatest theives and scoundrels.” On April 11th, three Indians stole Seaman. They also stole an axe, but Thompson wrestled it back from them. Three men set out to recover Seaman, with orders to fire on the Indians if they made any trouble. When they discovered they were being pursued, the thieves abandoned Seaman. The chief apologized, and the captains made him a present of a small medal. Lewis said he hoped it would keep the peace, as the “men seem well disposed to kill a few of them.”

In bringing the boats up over the rapids, they were portaging the baggage around the cascades and carrying their “short rifles” to prevent theft. The boats were being hauled by the means of cords over the raging waters, when they lost one pirogue when it hit a rock. They were able to purchase two small canoes to replace it. The fleet now consisted of four small canoes and two large pirogues. They were beginning to encounter Indians with horses as they approached The Dalles, but were unable to purchase any of them. They halted at Rock Fort (Fort Rock) and Clark went out with a party to purchase horses at neighboring villages.

Lewis and his party prepared saddles and baggage cords for 12 horses and continued with the boats up to the Long Narrows. There was no possibility of river travel through the Narrows, and so the pirogues were cut up for firewood, much to the chagrin of the natives—who, however, were unwilling to pay for them. Clark returned with four horses, for which he had been forced to pay high prices. They portaged around the Narrows with the four pack horses on April 19th. On that day, the natives reported the first salmon had arrived in the river. According to custom, this first salmon was cut in pieces and given to every child. The salmon would arrive in great quantities in about five days.

They were forced to trade two kettles to acquire two more horses. They now had one kettle left for each mess of eight men. Clark was extremely provoked when one of the horses couldn’t be found. The horses were stallions, who had not been gelded, and were at their “most vicious” during this season. It turned out the horse had been taken by an Indian who had won it gambling prior to its trade to Clark. Clark took back his goods from the seller. The Indians stole six tomahawks and a knife from them during the night. After that, he wrote they slept with their merchandise under the heads and arms ready to use, “as we always have in Similar Situations.” He called the natives, “great jokies and deciptfull in trade.” 515

Meanwhile Lewis was having trouble at camp. Tomahawks were stolen and though they searched the natives they couldn’t find them. Lewis said they would kill anyone who stole any more property and ordered all the spare poles, paddles and balance of the canoe burned rather than let the Indians have it.

They now had ten horses. William Bratton rode one, as he was suffering from back trouble and was too weak to walk. He had injured his back at the Salt Works and it hadn’t yet healed. One horse broke away, losing his baggage, but retaining his saddle and robe. They found the horse and its saddle, but not the robe. The robe had been stolen by Indians who denied taking it. Lewis said he would “birn their houses.” He wrote:

they have vexed me in such a manner by such repeated acts of villany that I am quite disposed to treat them with every severyty, their defenseless state pleads forgiveness so far as rispicts their lives.

Fortunately, at this point, one of their men discovered the robe hidden in a village hut. 516

By April 22nd they had acquired 13 horses. Clark wrote the horses, 10 of which were studs (male horses) were “very troublesom.” It was mating season. Over the next days they hired horses, bought horses, traded horses, lost horses, found horses and were given a horse. On April 27th, they arrived at the Walla Walla village of Chief Yelleppit, the head chief of the region, whom they had promised to visit on their return.