General Wilkinson paid a secret visit to Aaron Burr in New York City on May 23rd, 1804. The general was on his way to Washington to report to the president, bringing the American version of his Louisiana report and 28 maps of the Southwest made by Philip Nolan. Wilkinson sent Burr a note:

To save time of which I need much and have little, I propose to take a bed with you this night, if it may be done without observation or intrusion—Answer me and if the affirmative I will be with [you] at 30 after the 8th hour.537

This was the start of the renewed conspiracy of Wilkinson and Burr to invade Spanish territory. Historian Thomas Fleming in his book, Duel: Alexander Hamilton, Aaron Burr and the Future of America, proposes that Burr killed Hamilton over this issue in the famous duel, held on July 11th, 1804.

Aaron Burr, while still Vice President of the United States, had run for the office of Governor of New York in the preceding months. He ran as a Republican with the support of Federalists, but lost the election. Alexander Hamilton had worked strenuously to defeat him. Hamilton, the founder of the Federalist Party, supported Jefferson’s Louisiana Purchase because he believed in American expansionism, but most Federalists opposed the purchase.

Federalists argued the purchase was unconstitutional, but really feared it would increase the number of slave states and end their chances of regaining national power. The 3/5’s Compromise, brokered between slave and northern states at the Constitutional Convention in 1787, established that a slave counted for 3/5’s of person, increasing the slave states’ representation in the House of Representatives. All of the Louisiana Purchase states formed between 1803–1845 became slave-holdng states.

Map of the Northern Confederacy

There was open talk of seceding from the union among the Federalist congressmen from northern states, who advocated forming a Northern Confederacy consisting of New Jersey, New York, the New England states of Massachusetts, Connecticut, New Hampshire, Vermont and Rhode Island, and the British provinces in Canada and Nova Scotia. Hamilton opposed the election of Burr for governor of New York because if Burr became governor, he would lead the break away from the union. After Jefferson’s anticipated reelection in the fall, a secessionist meeting was going to be held in Boston.538

What were Wilkinson’s true feelings regarding Republicans and Federalists? When Meriwether Lewis made out his coded review of army officers, five out of six of the general’s staff were “opposed most violently to the administration and still active in its vilification,” and the sixth was “opposed more decisively.” Although Lewis left the general’s evalutation blank, Wilkinson was a staunch Federalist in his sympathies. When the general ap proached Aaron Burr in May, he must have been willing to cooperate with the Federalists planning to secede from the union, and willing to support the establishment of a Northern Confederacy with close ties to Great Britain.

The general and Burr had been planning an invasion of Texas during the election of 1800. The inconvenient truth, however, was that—if the Northern Confederacy succeeded in taking over Spanish territories—they would allow slavery. It was simply that Federalists and the British would be in control, rather than the French-loving Republicans.

Wilkinson had written to Alexander Hamilton from New Orleans on March 26, 1804, in response to a letter from Hamilton. Hamilton had asked the general to use his influence in aiding two young men who were moving to New Orleans. Wilkinson replied to Hamilton—with whom he had planned the establishment of the cantonment on the Ohio in 1799 when Hamilton was commanding general of the U. S. Army—

I would give a Spanish Province for an Interview with you. My Topographical information of the So. West is compleat. The infernal designs of France are obvious to me, & the destinies of Spain are in the Hands of the U. S. Name me if you please to G. Morris.

Gouvernour Morris, a firm supporter of George Washington, had cast the deciding vote during the Conway Cabal to keep Washington as Commander in Chief of the Revolutionary Army. He was also a supporter of taking Louisiana and the Floridas by force.539

Wilkinson believed the time was ripe to stage an invasion of Mexico. The geographical boundaries of the Louisiana Purchase were disputed by Spain, and a filibuster expedition to seize control of Sante Fe would settle the matter. It would also prevent any “infernal designs” of Napoleon to take back Louisiana and invade Mexico. Privately financed invasions of foreign territory by armed expeditions were popular during the first half of the 1800’s. Filibusters were associated with Free Masonry, and thousands of young Americans were ready to invade the Spanish countries surrounding the Gulf of Mexico, in order to aid their fellow masons in fighting for independence from Spain.540

After Wilkinson’s overnight interview with Burr, he left New York within the week. The general and his wife visited their son Joseph Biddle at Princeton, and arrived in Washington on June 25th. It was three weeks before the duel which ended Alexander Hamilton’s life.

It seems likely that another visitor to Burr’s home stimulated his plan to force a duel with his arch enemy Alexander Hamilton. The visitor was Charles Williamson, a Scottish-born American citizen who had acted as land agent for one million acres of land in western New York owned by British investors. Aaron Burr had done legal work for Williamson and was a speculator in New York’s western lands himself. Williamson, after ending his employment as land agent, had gone to England where he associated with high ranking government officials, and was now back in the U. S. promoting a new project.

He was planning a filibuster, which he called “The Levy.” On May 16th he wrote to Burr that he expected to see him in one month’s time, when he would be in New York City before returning to England. His plan for “The Levy” involved using young Englishmen who had recently arrived in the U. S. to serve as a corps of volunteers to invade the French West Indies and Spanish possessions on behalf of Great Britain.541

Aaron Burr had strong connections to a prominent British family, the Prevosts. His wife Theodosia was first married to Jacques Marc Prevost, a British military officer. She was a widow with five children when she married the 26 year old Burr in 1782. Theodosia died in 1794, leaving him to bring up their only child, also named Theodosia, born in 1783. His wife’s first husband was the uncle of George Prevost, who was serving as Governor of the British island of Dominica in the West Indies in 1802–05. Sir George became the Lieutenant Governor of Nova Scotia in 1808, and then served as Commander in Chief of British North America during the War of 1812.

Thomas Jefferson had a bust of Alexander Hamilton placed in the entrance hall of Monticello opposite his own portrait bust. (www.monticello.org)

Williamson may have brought Burr a copy of an upstate New York newspaper, which contained a letter in which the writer said that he heard Hamilton speak of Burr as a “dangerous man and [who]ought not to be trusted.” After the letter was published, the writer defended his comments by saying, “I could detail you a still more despicable opinion which Gen. Hamilton has expressed of Mr. Burr.” Since newspapers of New York State had been filled with outrageous remarks during Burr’s run for governorship, by Burr taking offense at the word “despicable,” it was Burr’s means of challenging Hamilton to a duel.

Burr sent a letter to Hamilton on June 18th asking him to deny the allegations. Hamilton replied it was “too indefinite to discuss.” The situation continued to escalate until it ended in a duel which took place across the Hudson River in New Jersey, because New Jersey was more lenient in prosecuting duelists.

It appears that Hamilton had decided to end his life in order to destroy his rival’s chance of breaking up the union. On June 27th Hamilton wrote he had decided “to reserve and throw away my first fire,” but he was not going to tell Burr. In his last letter to his wife he said he was unwilling to take the life of another, and would rather “die innocent than live guilty.” On his last night, Hamilton wrote to Thomas Sedgewick of Massachusetts:

I will here express but one sentiment that Dismembrement of our Empire will be a clear sacrifice of great positive advantages without any counterbalancing good.

After the duel on July 11th, it was disputed whether Burr or Hamilton fired the first shot. Burr’s shot hit Hamilton in his liver and diaphragm. Hamilton’s gun discharged, but it was a wild shot which hit a tree 12½ feet from the ground. His comment that he was going to reserve fire was reported to the doctor in attendance and others. Hamilton died the next day, leaving behind a widow and seven children. She was the daughter of General Philip Schuyler of upstate New York, and he wrote he trusted her father would save her from “indigence.” Unfortunately, her father was also deeply in debt.542

After the death of Hamilton, Burr was indicted for murder by a coroner’s jury. Before the jury handed down its verdict on August 2nd, Burr fled to Philadelphia where he met with Charles Williamson who promised to enlist British government support for an invasion of Texas and Mexico. The British Ambassador Anthony Merry was in Philadelphia for medical treatment. On August 6th, the ambassador wrote a “Most Secret” letter to the British foreign secretary, Lord Harrowby:

My Lord,

I have just received an offer from Mr. Burr the actual vice president of the United States (which Situation he is about to resign) to lend his assistance to His Majesty’s Government in any Manner in which they see fit to employ him, particularly in endeavoring to effect a Separation of the Western Part of the United States from that which between the Atlantick and the Mountains, in it’s whole Extent.—His proposition on this and other Subjects will be fully detailed to your Lordship by Col. Williamson who has been the Bearer of them to me, and who will embark for England in a few Days….543

On August 11th, Burr left Philadelphia to visit Saint Simeon’s Island in South Carolina, the home of politician Pierce Butler. For ten days in September the two men explored Spanish Florida by horseback and canoe. When he returned north, Burr took his place in the Senate on November 5, 1804. His house in New York City had been auctioned off and sold to John Jacob Astor to satisfy his creditors. He was ruined politically in the East, but the rest of the country looked more favorably on dueling and was anti-Federalist in its sympathies.

It was during the winter of 1804–05 that General Wilkinson and Vice President Burr poured over maps of the Southwest together in Washington. Jefferson and Wilkinson must have thought Hamilton’s death had ended Burr’s role in heading up a Northern Confederacy, and that—in the event of war with Spain over the boundary disputes—Burr and his followers could be employed in an American filibuster to invade Texas and Mexico. Burr’s term as vice president came to an end in March.

Wilkinson’s life style was recorded by a neighbor, who lived next door to him in Washington—

Genl. Wilkinson was an elegant Gentln in person & manner. He was of medium size, probably 5 feet 8 or 9 inch…. He was sumptuous & hospitable in his living; not very nicely balancing his means & ends—He appeared much abroad with his aide [his eldest son, James Biddle Wilkinson] both in full uniform, and generally on horseback. His array was splendid; he having gold stirrups & spurs, & gold leopards claws to his leopard saddle cloth. 544

In March, 1805, Jefferson appointed Wilkinson to the post of Governor of Louisiana Territory, based in St. Louis, while retaining his military command, a combination which many considered a dictatorship. Jefferson appointed Aaron Burr’s relatives to other government posts. Burr’s brother-in-law, Dr. Joseph Browne, became Secretary of Louisiana Territory under Wilkinson, and his stepson, James Prevost, became a Superior Court Judge in New Orleans Territory. After receiving his appointment, Wilkinson wrote to Charles Biddle, his wife’s cousin—

I can only say the country is a healthy one, and I shall be on the high road to Mexico.545

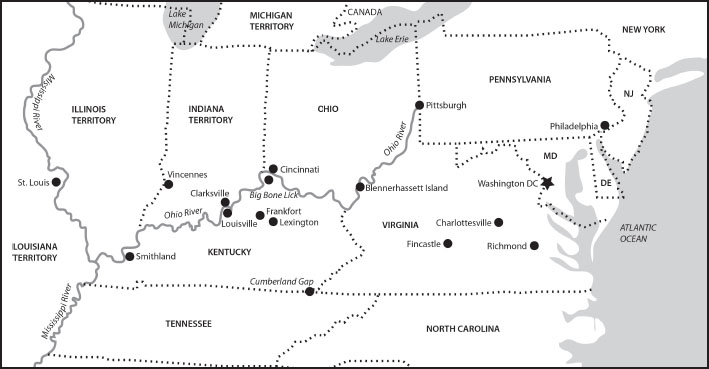

Wilkinson and Burr were supposed to journey together down the Ohio River, but the general was delayed with family matters. Burr, who was setting out on a 3,000 mile tour to explore the western country, had a “floating house” built for him at Pittsburgh. He stopped at Marietta to inspect the boatyards and tour the Indian mounds, and then visited Blennerhassett Island in early May. The island was the site of a magnificent mansion, built by an ecentric and radical Irish aristocrat and his wife, Harmon and Margaret Blennerhassett. The island location would become the focus of Aaron Burr’s treason trial in 1807.

Burr abandoned his boat in Louisville and began a tour of Kentucky and Tennessee by horseback, making friends and being introduced to men of consequence everywhere. At Nashville he was a guest of Andrew Jackson, who provided a boat for him to return to the Ohio River. Burr arrived at Fort Massac near the junction of the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers on June 6th, where he met with General Wilkinson. They spent four days together, before the general went to St. Louis to assume his post as governor, and Burr went to New Orleans with a military escort provided by Wilkinson. At New Orleans, he met with the Mexican Association, a secret society of about 300 Americans who were planning to “liberate” Mexico.

The leaders of the association were Edward Livingston and Daniel Clark. Edward Livingston was Aaron Burr’s long time friend. Livingston had served as both the Mayor and U. S. District Attorney for the City of New York in 1801–03. A confidential clerk stole or mismanaged money from the district attorney’s office and Livingston was responsible for the loss. He resigned his positions and moved to New Orleans early in 1804. The choice of New Orleans was more than a coincidence—his brother, Robert R. Livingston, had negotiated the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, and there was said to be a Mexican Association in New York City on which the New Orleans association was modeled.546

Daniel Clark, the Irish-born nephew of a wealthy New Orleans merchant, was Wilkinson’s business partner. Clark, after the Burr Conspiracy collapsed in 1807, wrote a book called Proofs of the Corruption of General James Wilkinson and of His Connexion to Aaror Burr, published in 1810. The next year Wilkinson published a rebuttal, Burr’s Conspiracy Exposed and General Wilkinson Vindicated Against the Slander of His Enemies on That Important Occasion. Daniel Clark fought a duel with Governor William Claiborne in 1807, while serving as the congressman from Orleans Territory in 1806–09.547

Daniel Clark tried several times to expose Wilkinson as a Spanish agent, but the general successfully defended himself. He was found not guilty by a military court of inquiry in 1808. Congressional investigations in 1808–10 were inconclusive, and the general demanded a military court-martial in 1811, which again found him not guilty. Of course he was guilty of being a Spanish agent, but his activities in defending New Orleans against the Mexican Association, Burrites, and the French and British were the real reasons he escaped censure.

Burr stayed in New Orleans for 17 days as a guest of Edward Livingston. The Catholic Bishop designated three Jesuits to aid him in revolutionizing Mexico and the Ursuline Mother Superior gave her support. Daniel Clark pledged $50,000 ($2 million in today’s money). The army of liberation would consist of 8,000 militia from Louisiana, 10,000 militia from Kentucky, 3,000 regular troops and 5,000 slaves who would be promised their freedom. There were already fifty five cannons left behind by the French from their short-lived occupation of Louisiana which would be used.547

Burr was no slacker. He chose to travel by horseback along the Natchez Trace for his 400 mile return journey to Nashville. He wrote he found the road almost non-existent, and where it did exist, it was overgrown with bushes. General Jackson gave Burr a public banquet and ball, and everywhere he went he renewed his friendships with westerners. From Nashville Burr returned to Louisville and took a boat to St. Louis, arriving for a reunion with Wilkinson on September 12th.

It is at this point that divergent paths occur. Members of the Mexican Association wanted to capture Baton Rouge and the American Fort Adams, and then take control of the banks and shipping of New Orleans. The British fleet in the Bahamas would be utilized in an invasion of Mexico. The plan was based on a proposal by Burr’s rival, General Francisco de Miranda, a Venezulean Freemason who had plotted for many years with the British government to revolutionize the Spanish colonies in the Americas. New Orleans would serve as capitol of a new country.

When Burr entered into discussions with the association, he brought new energy and new plans to the table. Because of his ties to Wilkinson, he could claim he had the secret support of the United States government. War between the U. S. and Spain was widely expected in 1805, and General Wilkinson would lead the army in an invasion of Mexico in support of Mexican independence. The army would travel from St. Louis to Sante Fe.

At the same time, Burr’s volunteers and the Mexican Association, could take over New Orleans, and—while the U. S. Army was too busy fighting in Mexico to oppose it—they would establish a new independent country headquartered in New Orleans. Burr’s schemes had many moving parts which could be altered to suit any audience he was talking to, but they depended upon a war with Spain.548

Historian Thomas Crackel, author of Mr. Jefferson’s Army, points to a letter that Secretary of War Henry Dearborn wrote to General Wilkinson on August 24th, 1805.

There is a strong rumor that you, Burr, etc., are too intimate … You ought to keep every suspicious person at arm’s length, and be as wise as a serpent and as harmless as a dove.549

Daniel Clark warned Wilkinson, writing on September 7th:

Many absurd and wild reports are circulated here…. You are spoken of as [Burr’s] right hand man…. The tale is a horrid one, if well told. Kentucky, Tennessee, the State of Ohio, with part of Georgia and part of Carolina, are to be bribed with plunder of the Spanish countries west of us to separate from the union…. Amuse Mr. Burr with an account of it.550

On September 8th, Wilkinson wrote to Secretary of War Dearborn describing his plans for an invasion of Sante Fe. Some excerpts from his detailed report are—

Should we be involved in a War (which Heaven avert) and it should be judged expedient to take possession of New Mexico …. These dispositions with judicious order and rapid movements attended by the Cross for your Banner, and a band of Irish Priests who have been educated in Spain (of whom I have a dozen) and we should take possession of the Northern Provinces without opposition, after which we might increase our force according to our means and at our discretion—The uncertainty of human life and the instability of political affairs, induce me to lodge this information with you in its present crude State … 551

The Gazette of the United States, published on August 2nd in Philadelphia, an article headlined “Queries,” which accused Burr of plotting a revolution with a series of inflammatory questions, including—

How soon will the forts and magazines in all the military ports of New Orleans and on the Mississippi be in the hands of Col. Burr’s revolution party? How soon will Col. Burr engage in the reduction of Mexico, by granting liberty to its inhabitants, and seizing on its treasures, aided by British ships and forces?

Newspapers across the country quickly republished “Queries” and it was even published in the Lexington Kentucky Gazette while Burr was in town on his return journey. The most likely author of the anonymous article was Spanish ambassador, Marqués de Casa Yrujo, married to Sally McKean, daughter of the governor of Pennsylvania, Thomas McKean.552

From August, 1805 onward there were widespread rumors across the country of revolutionary intrigues against Mexico linked to Aaron Burr. Wilkinson reacted by keeping his distance, but Burr appeared not to notice it. Finally on April 6th, 1806 Burr wrote to Wilkinson saying, Nothing has been heard from brigadier since October.553 It still didn’t seem to raise any doubt in Burr’s mind as to whether he had the general’s support.

When Burr returned to Washington in November, he met with British Ambassador Anthony Merry and learned Merry’s letter written in August, 1804 regarding Burr’s proposals had never reached London due to a boat accident. Merry reported in a letter to Lord Mulgrave on November 25, 1805 that Burr planned to launch his operation four months later, in March, 1806. Burr wanted British ships of war at New Orleans by April 10th, and a loan of 110,000 pounds stirling. He warned Merry if his demands were not met, France would regain the country and annex the Floridas. Merry believed Burr’s statements that once Louisiana and the western country became independent, the northern states would separate from the southern states and a new country would be formed.554

Burr’s friend, Jonathan Dayton, met with the Marqués de Casa Yrujo, the Spanish Ambassador, the next month in Philadelphia. Dayton, a former congressman and senator from New Jersey, told Yrujo the British were supporting Burr and that, after New Orleans and the Floridas fell, Mexico would be invaded. After several meetings, Dayton revealed a new plan, saying he had lied about British support. Dayton told Irujo that Burr planned to take control of the government in Washington with armed adventurers, seize control of the banks, take the best ships and burn the rest, and sail to New Orleans, where they would leave the Floridas alone and make a satisfactory border settlement with Spain. Yrujo paid Dayton $2,500 towards this project.555

Burr was having trouble raising money in New York because General Francisco de Miranda had arrived there with his ship, the Leander, for a filibuster expedition to invade Venezuela and South America. Burr’s supporter in London, Charles Williamson, had become involved in Miranda’s plan. President Adams’s son-in-law, William S. Smith, was a supporter of Miranda, along with Ogden family members who would later support Burr. The Leander became an embarassment to Jefferson when it sailed from New York in February and was captured by the Spanish. William S. Smith and Samuel G. Ogden stood trial in July, 1806 in a U. S. Circuit Court, charged with violating the Neutrality Act of 1794; both men were found not guilty.556

Meanwhile President Jefferson was trying to negotiate a deal with Spain to buy West Florida, with an agreement to recognize the Rio Grande River as the boundary of Louisiana. He received a secret appropriation from Congress of two million dollars in February, 1806 to be used for this purpose.557

The Mexican government was taking no chances. In October, 1805, they established two small outposts east of the Sabine River (“Say-bean”) on ground claimed by both nations. When news of this was received in Washington, Wilkinson was ordered to begin reconnaissance missions. The president in his annual message to Congress in December, 1805 announced he had ordered troops to be in readiness to protect U. S. citizens in Orleans and Mississippi Territories, and there were upwards of “300,000 able-bodied men between the ages of 18 and 26 years,” who could be used for “offense or defense” if they were needed.558

Previously, in 1804, the president had authorized William Dunbar to lead a expedition to explore the Ouachita River. Dunbar was a Scottish-born surveyor with whom he had carried on a scientific correspondence for years. The Dunbar-Hunter Expedition of 1804 was cut short by hostile Osage Indians and Spanish officials.

General Wilkinson, after arriving in St. Louis to serve as governor of Upper Louisiana, sent Lieutenant Zebulon Pike up the Mississippi River on July 30, 1805. Pike’s mission was very similiar to the Lewis and Clark expedition, but his assignment was limited to one season of exploration. Wilkinson had other plans in mind for the young officer. When he returned on April 30th, 1806, he was assigned to exploring the Southwest.

In 1806, Dunbar organized the Freeman-Custis Expedition to explore the Red River. The mission of the expedition, led by surveyor Thomas Freeman and botanist Dr. Peter Custis, was to map the Red River and discover whether it was a suitable water route to Sante Fe. Freeman was the surveyor who had been fired by Andrew Ellicott and hired by Wilkinson to construct Fort Adams. The Freeman-Custis Expedition was halted by Spanish troops 615 miles up the Red River in northeastern Texas, and forced to turn back in late July, 1806. The expedition had a military escort of 45 soldiers.

On July 15th, 1806, Captain Zebulon Pike, Jr. accompanied by Wilkinson’s son, Lieutenant James Biddle Wilkinson, set out from St. Louis on a multifaceted mission. They escorted Indians back to the Osage village on the Osage River in Kansas and to the Pawnee village on the Republican River in Nebraska, where the Spanish army expedition had been halted a few weeks earlier by the Pawnee chief. The Spanish expedition was hunting for Pike’s party, which arrived a few weeks after the Spanish left.

Pike’s party headed south to the Arkansas River, and split into two groups. Lt. Wilkinson followed the Arkansas back east to the Mississippi, and Pike followed the Arkansas west to the mountains; Pike’s Peak near Colorado Springs is named for his exploits. After making a large circle, Pike returned to the Arkansas and dropped south to the headwaters region of Rio Grande, where he built a fort near Alamosa, Colorado. They stayed there from January 31-February 26, 1806. Pike claimed he mistakenly thought the Rio Grande was the Red River.

Pike had written to Wilkinson shortly after setting out from St Louis, on July 22, 1806 that he expected to be in the vicinity of “St. Afee,” and if they should encounter the Spanish, he would—

… give them to understand that we were bound to join our Troops near Natchitoches but have been uncertain about the Head Waters of the Rivers over which we passd—but now if the Commandt. desired it we would pay him a visit of politness—either by Deputation, or the whole party—but if he refused; signify our intention of pursuing our Direct route to the posts below—this if aceded would gratify our most sanguine expectations; but if not I flatter myself, secure us an unmolested retreat to Natchitoches. 559

If they were made “prisoners of War—(in time of peace)” he trusted their release would be secured by the United States.

The 27 year old Pike was accompanied by Dr. John Hamilton Robinson, a 24 year old medical doctor who for many years was involved in filibusters for the liberation of Mexico.560 Dr. Robinson set out for Sante Fe on February 7th, 1807, leaving Pike and five soldiers struggling for survival and suffering from frostbite in the small fort on the Rio Grande. When Robinson arrived at Sante Fe, a detachment of 100 soldiers was sent to bring Pike and his men back to Sante Fe. Altogether, Pike’s party numbered 16 men, some of whom were scattered at other locations.

Governor Alencastar at Sante Fe hosted Zebulon Pike at a splendid dinner on March 3rd, and in parting asked Pike to—“remember Allencaster in peace or war.” Pike and his men were escorted to Albuquerque where they met up with John Robinson and Pike learned that Captain Falcundo Melgares would escort them to Chihauhau. Melgares had been the leader of the 300 man expedition which had gone to the Pawnee Village to capture Pike. They were entertained with fandangos (dances) with beautiful women and parties along the way, reaching Chihauhau on April 3rd.

For over three weeks they remained at Chihauhau, headquarters of General Nemesio Salcedo, Commanding General of the Internal Provinces. His nephew Manuel Maria de Salcedo became Governor of Spanish Texas in 1808. Manuel de Salcedo’s father, Juan Manuel de Salcedo, had been governor of Spanish Louisiana in 1801–03, based in New Orleans.

On leaving Chihauhau, Pike found that he was forbidden to take notes. He secretly wrote detailed notes of the people and places along their travel route and hid them in his men’s gun barrels and under their shirts. Along the way Pike encountered many priests and community leaders who supported independence.

On June 7th they reached San Antonio, in Spanish Texas, where they were greeted by Governor Antonio Cordero of Texas and Governor Simon de Herrera of Nuevo Leon. Pike wrote “we were received like their children,” and were offered any means of leaving Mexico they desired. Pike and Robinson were guests in Governor Cordero’s home for five days before leaving for Natchitoches and the United States.

Pike wrote a most interesting description of the two governors, and the conversations he had with them:

The two friends agreed perfectly in one point, their hatred to tyranny of every kind; and in a secret determination never to see that flourishing part of the New World, subject to any other European lord, except him [King Charles IV of Spain], whom they think their honor and loyalty bound to defend with their lives and fortunes. But should Bonaparte seize on European Spain, I risque nothing in asserting, those two gentlemen would be the first to throw off the yoke, draw their swords, and assert the independence of their country.561

In regards to the Neutral Ground Agreement that Governor Herrera had reached with General Wilkinson seven months earlier, on November 6, 1806, Pike recorded an anecdote told by Herrera, who was in command of 1,300 troops at the Sabine River when he met with Wilkinson. His superior, General Nemisio Salcedo, had ordered Herrera to attack the U.S. forces if they should cross the Arroyo Hondo (“Deep Stream,” now known as the Calcasieu River). Herrera told Pike, that—

… he called a council of war on the question to attack or not; when it was given as their opinion, that he should immediately commence a predatory warfare, but avoid a general engagement; yet notwithstanding the orders of the viceroy, the commandant general, governor Cordero’s and the opinion of his officers, he had the firmness (or termerity) to enter into the agreement with general Wilkinson, which at present exist relative to our boundaries on that frontier. On his return he was received with coolness by Cordero, and they both made their communication to their superiors. Until an answer was received, said Herrera, “I experienced the most unhappy period of my life, conscious I had served my country faithfully, at the same time I had violated every principle of military duty.” At length the answer arrived, and what was it, but thanks of the viceroy and commandant general, for having pointedly disobeyed their orders, with assurances that they would represent his services in exalted terms to the king. What could have produced this change of sentiment to me [Zebulon Pike] is unknown, but the letter was published to the army, and confidence again restored between the two chiefs and the troops.562

The change in sentiment was no doubt facilitated by the large amount of money—$16,883.12—that General Wilkinson received from the federal government while on the Sabine. The War Department’s accountant, William Simmons, wanted to know more about this irregular transaction, and why it was not being charged to Wilkinson’s account for secret service money. Captain Moses Hooke delivered amounts of $2,500 and $1,196 for secret service expenses in January, 1807 while Wilkinson was at New Orleans, but this expense money was different. Captain Hooke delivered this money in three installments to the general in October and November, 1806 and January, 1807. Simmons complained that Wilkinson had appointed Hooke as “quartermaster general to the expedition on the Sabine,” but—

… no such appointment as quarter-master general is authorized by law, neither is there any particular appropriation, or head of expenditure, to which such payments are chargeable. I have repeatedly called upon Captain Hooke to produce vouchers for the expenditures of the above sum, which he has never done. In conversation with him, not long since, he observed, that a considerable sum of money had been drawn out of his hands by General Wilkinson on account of secret services, and for which he only had the general’s receipt. Captain Hooke is now out of service, and his account has been reported to the Treasury for a suit.

Captain Moses Hooke (1777–1821) was Lewis’s choice of a second in command if William Clark couldn’t join him. Hooke was the commander of Fort Fayette in Pittsburgh. He resigned from the army on January 20, 1808, married a wealthy widow, and settled down in Mississippi.

(franceshunter.wordpress.com)

In short, the accountant wanted to know under which column of expenditures he should list the $16,883.12.563 The logical explanation is the money was used to bribe Mexican officials, and given the timing, it must have been arranged between Jefferson and Wilkinson months earlier.

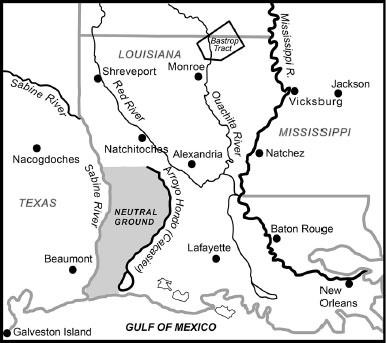

The Neutral Ground Agreement between the two generals, Wilkinson and Herrera, established a “no man’s land” which was inhabited by renegades, outlaws, filibusterers, escaped slaves, and its original inhabitants, the Attakapas Indians. It became the center of the slave trading operations of the Lafitte pirate brothers—whose headquarters were on Galveston Island—after the War of 1812. The Neutral Ground (approximately 55 miles at its widest point, and 110 miles in length) endured until the Adams-Onis Treaty of 1821 fixed the boundary line between Lousiana and Texas at the Sabine River. This pragmatic solution to the boundary dispute was desired by both the United States and Spain, as a war would have allowed Aaron Burr and his followers the opportunity to seize New Orleans and invade Mexico by way of Vera Cruz, a seaport on the Gulf of Mexico.

Neutral Ground and Bastrop Tract areas

In 1806 Burr entered into a contract to buy a piece of land known as the “Bastrop Tract” on the Ouachita River. The 350,000 acre tract had been acquired by American speculators from the “Baron De Bastrop,” a Dutch con artist. The “Baron” had no title to the land owned by the Spanish government, but was acting as their agent in selling land to settlers. He was to earn his profits from the exclusive right to mill the settlers’ wheat and sell the flour in Havana and Cuba.564 The fraudulent real estate deal provided Burr with a reason to bring a large group of men to Louisiana, who were promised free land.

Historian Thomas Abernethy, in his classic book, The Burr Conspiracy, says the purchase was “sheer speculation” and “Burr did not expect to make his claim good under the government of the United States.” In October, 1806 Burr wrote to a friend enclosing a map, showing where a 30 mile road was to be built from the Bastrop Tract to the Mississippi River and a longer one to Natchitoches. Burr’s men were given tools for clearing roads, but no farm implements or seed, and women were not allowed on the expedition.565

Land speculation was going on everywhere, as investors anticipated the acquisition of Spanish territory by the United States, and/or the separation of the western states from the union. The possession of a land title and the occupation of the land were the two factors to be considered, no matter how circumstances played out. Spanish officials and Americans were both engaged in land speculation.

General Wilkinson was careful not to have his name on any Louisiana titles, but he was speculating in claims registered in the names of Daniel Clark and other friends. Wilkinson openly acquired land in West Florida—the title to Dauphin Island at the mouth of Mobile Bay—through the English trading firm, John Forbes and Company of Pensacola, Florida on March 6, 1806.566 Dauphin Island was one of the most strategic locations on the Gulf. It was a major trading port, the former home of a French fort established in 1702, and later, the home of the American Fort Gaines established in 1821. During the War of 1812, General Wilkinson seized Dauphin Island for the United States after the Spanish garrison at Mobile Bay surrendered peacefully.

Historian James Ripley Jacobs, author of the classic biography of Wilkinson, Tarnished Warrior, says that how he acquired Dauphin Island is not clear, but it was probably in payment for keeping the Spanish informed about Burr’s movements. Ironically, in 1813, after Dauphin Island became the property of the United States, Wilkinson’s claim to ownership was disallowed on the grounds that he was not a “Spanish citizen.” 567

The Aaron Burr Expedition of 1806–07 has been the subject of many full length books. Though the title of this chapter is “The Burr-Wilkinson Conspiracy, 1804–07,” Wilkinson was actively working against Burr during the latter half of the conspiracy—mostly likely from the time of their meeting in St. Louis in September, 1805, after Burr had visited New Orleans and met with the Mexican Association. The general, however, continued to lead Burr on, in order to learn his plans, and because the president wanted to make certain that a charge of treason would stick when Burr was eventually brought to trial.

In the summer of 1805, Burr had met with the Mexican Association leaders—Edward Livingston, Daniel Clark, and Burr’s stepson, J. B. Prevost—in New Orleans. The semi-secret society, whose goal was the liberation of Mexico, had about 300 American members who moved to New Orleans after the Louisiana Purchase. They were intending to work with Burr’s rival, the Venezuelan revolutionary, Francisco de Miranda. Now they were also working with Aaron Burr.

Earlier that year, in March, 1805, President Jefferson had appointed Wilkinson, Governor of Louisiana Territory; Burr’s brother-in-law, Joseph Browne, Secretary of Louisiana Territory; and his stepson, J. B. Prevost, Judge of Superior Court in Orleans Territory. Burr could create a new career for himself by being elected to congress from one of the western territories or states. Jefferson intended that Burr’s filibusterers would join with Wilkinson’s army if a war with Spain broke out, but when Burr met with the Mexican Association, it became clear that Jefferson’s peace offering wasn’t going to be accepted.

When Burr returned to the east coast in late 1805, he found everyone—including President Adam’s son-in-law, William S. Smith—was supporting Miranda’s filibuster to liberate Venezuela. Miranda had arrived in New York in November and hired a ship, the Leander, from Samuel Ogden. The Leander was captured by the Spanish on its way to Venezuela. Miranda later accused Burr of betraying him, and the Spanish Ambassador, the Marqués de Casa Yrujo, reported to his superior that he had paid Burr and his associates $2,500 for revealing Miranda’s plans, among other things.568

At this time, Burr’s associate, Jonathan Dayton, the former senator from New Jersey, was often seen meeting with Yrujo and another Burr associate, Dr. Erich Bollman, in a tavern where Burr was staying. Bollman was a German adventurer who had attempted to liberate the Marquis de Lafayette from an Austrian prison in 1794. With Bollman’s help, Lafayette had managed to escape, but he was quickly recaptured. (Lafayette was released from prison in 1797.) Bollman was imprisoned for eight months, and came to the United States after this adventure.569

In 1805, Erich Bollman became involved in the Burr Conspiracy. General Victor Moreau, a French general banished by Napoleon, had arrived in United States in September, 1805 and was living at Morrisville, Pennsylvania near Philadelphia, and across the Delaware River from Trenton, New Jersey. In June, 1806, Burr vacationed near Morrisville with his daughter and her family, and met with Bollman and General Moreau frequently. By the end of July, Burr was ready to set his plans in motion.570

Dr. Bollman and other associates were sent by sea to New Orleans. Dayton wrote to Wilkinson on July 24th that it was well know Jefferson was going to replace Wilkinson as commanding general of the army in the next session of Congress—“Are you ready? Are your numerous associates ready? Wealth and Glory! Louisiana and Mexico!”

Burr wrote to Wilkinson in cipher on July 29th. The famous cipher letter told Wilkinson he had received funds and was starting operations. He promised there would be British and American naval support. He would bring 500–1,000 men in light boats to “seize on or pass by Baton Rouge,” and would meet Wilkinson in mid-December at Natchez. He wrote:

It will be a host of choice spirits. Wilkinson shall be second to Burr only; Wilkinson shall dictate the rank and promotion of his officers. Burr will proceed westward first August never to return. With him goes his daughter; her husband will follow in October, with a corps of worthies…. The people of the country to which we are going are prepared to receive us; their agents now with Burr, say that if we will protect their religion, and will not subject them to a foreign Power, that in three weeks all will be settled. The gods invite us to glory and fortune; it remains to be seen whether we deserve the boon.571

Burr set out in late August accompanied by his German secretary, Charles Willie, and his chief-of-staff, Colonel Julien De Pestre, a French military officer who had served in both the French and British armies. Pittsburgh was a main rendezvous place for the small groups of men who began traveling to join them. At Blennerhassett Island in the Ohio River near Marietta they began assembling boats and supplies. Burr went to Kentucky, joining Theodosia and her family at Lexington. There were large sums of money being spent on supplies. Burr had promised six months of provisions to Wilkinson. A contractor said Burr and his wealthy New York friends purchased $200,000 worth of provisions in Kentucky, enough for an army of 25,000.572

The United States District Attorney for Kentucky, Joseph Hamilton Daviess, a brother-in-law of Chief Justice John Marshall, had been alerting President Jefferson of the dangers posed by both Wilkinson and Burr, sending him information as he received it. Daviess’s objective was to stop the expedition before it got started. On the 5th of November, Daviess made out a warrant for the arrest of Aaron Burr on the charge of preparing a military expedition against Mexico. Burr stood trial in Frankfort in early December. The grand jury exonerated Burr, who proceeded on to another meeting with Andrew Jackson in Nashville.

There were reports of 1,000 young men on the river in December, 1806 traveling between Pittsburgh and Marietta. Historian Thomas Abernethy writes:

Judging by the quantity of supplies contracted for and the number of boats built, a total force of at least 1500 men must have been contemplated.573

Burr’s eastern supporters were described as Federalists and Royalists who opposed the Louisiana Purchase—but many intended to settle there. It is no wonder there are countless, conflicting stories of what Burr was planning—separating the western states, starting a colony at Bastrop, invading the Floridas and Mexico, seizing New Orleans. He told different stories to everyone, but they all thought it was going to be a Grand Adventure.

The fortress guarding the entrance to Vera Cruz harbor, where the gold and silver of Mexico was stored to be shipped out on Spanish treasure ships. (Wikimedia Commons)

The most logical explanation is that Burr intended to arrive at New Orleans with as many men as he could recruit, and take over New Orleans in a bloodless coup organized by the Mexican Association, seizing the banks and ships. The rumors must have been absolutely electric regarding an invasion of Mexico. There would be no war between the United States and Spain because General Wilkinson and Colonel Herrera signed the Neutral Ground Agreement on November 5th. Now Burr’s plan depended entirely upon reaching New Orleans.

This is where it gets interesting when you consider the international associates of Burr—the Marques de Yrujo, General Victor Moreau, Erich Bollman, Charles Willie, Harmon Blennerhassett, and Colonel Julien De Pestre. What would happen after they arrived in New Orleans? It appears they were working with French agents in Mexico and their Mexican collaborators. In 1807, France and Spain were allies in the war against Britain. In 1808, Napoleon would turn against Spain and put his brother on the Spanish throne, but that was in the future.

Ambassador Yrujo had been recalled by the Spanish government in February, 1806; but he remained in the United States, living in Philadelphia, the home of his wife’s family. His father-in-law, Thomas McKean, was the pro-French, Republican Governor of Pennsylvania from 1799–1808. Philadelphia was a center of French refugee revolutionaries, and there would have been ample opportunity to connect with the Spanish French party.

Vera Cruz and the silver mines of Mexico. San Luis Potosi is where some of the richest silver mines are found.

Secretary of State James Madison received an anonymous letter warning him Burr was working with Yrujo, and Madison thought there was a plan to establish Burr as the head of a subconfederate state of France in the Spanish Americas. In 1808, when Burr was in exile he worked closely again with Yrujo in London. Senator William Plumer’s noted in his diary on January 27, 1807:

Dined with the President of the United States—[he said]—he did not believe either France, Great Britain, or Spain was connected with Burr in this project, but he tho’t the marquiss de Yrujo was—That he had advanced large sums of money to Mr. Burr—& his associates. But he believed Yrujo was duped by Burr. That last winter there was scarse a single night but that, at a very late hour, those two men met & held private consultations. I have since then ascertained the fact.574

Burr spent a lot of time in private meetings with both Ambassador Yrujo and General Moreau, Napoleon’s rival who had been sent into exile by the emperor. His chief of staff was an experienced French officer, Julien De Pestre. New Orleans was a French city. Burr spoke French. It is altogether plausible that Burr was collaborating with the French party in Mexico. In fact, Burr would repeat this pattern during his European travels in 1808–12—first he approached the English, and then Napoleon with his plans for another attempt at invading Mexico.

The trap was set, and Aaron Burr was on his way to being caught. When he visited Andrew Jackson in late September, 1806 at Nashville, he told him that war with Spain was imminent. Jackson then wrote to President Jefferson telling him he had three Tennessee militia regiments ready to march against the Spanish. Jefferson replied by asking Jackson to explain his offer.

Burr and his entourage were based in Lexington, Kentucky as plans for the invasion went ahead on multiple fronts. Abernethy says “much collateral evidence” supports the idea that Burr was planning to wait with his forces at Natchez until the Mexican Association made a “declaration of independence” in New Orleans.

The liberation of Mexico made strange bedfellows, as Burr’s western supporters were Jeffersonian Republicans and his eastern supporters were Federalists and British loyalists. It would not have worked out. But, of course, he believed he was about to set himself as the leader of a new country and the past would be forgotten. Above all else, Aaron Burr was a very good salesman. The prospect of being in on the ground floor of an independent Mexico, or a “liberated” Spanish Empire, excited the greed of everyone involved and blinded them to their own obvious conflicts of interest.

On the 27th of September, Colonel Herrera pulled back his force of 600 soldiers to the west side of the Sabine, disobeying his government’s orders. General Wilkinson had arrived at Natchitoches on September 22nd. On the 26th and 28th, Wilkinson wrote to Senators John Smith of Ohio and John Adair of Kentucky urging them to join him with militia troops for an army invasion of Mexico. Both men would later be accused of participating in the Burr Conspiracy.

The general was entrapping the two senators. He wrote to his long time friend Adair—“unless you fear to join a Spanish intriguer [Wilkinson] come immediately—without your aid I can do nothing.” Wilkinson would arrest Adair when he arrived in New Orleans on January 14, 1807, and ship the senator out to Fort McHenry in Baltimore. Two years later, Adair sued Wilkinson from “wrongful arrest,” and won a judgement of $2,500. The judgement was paid by Congress on Wilkinson’s behalf. 575

Colonel Herrera, who was in charge of the Spanish forces on the Louisiana frontier, was a staunch supporter of the Spanish king. Herrera—who was married to an English wife—had met and admired George Washington when he traveled in America. He won the commendation of his superiors for disobeying orders because by withdrawing his forces to the west side of the Sabine, he defused the war situation and prevented the French faction of Mexican revolutionaries and the Burrites hastening to join them from overthrowing the royalist government.576

On October 8th, the general received Aaron Burr’s cipher letter of July 29th and the letter from Jonathan Dayton saying he would be replaced as commanding general at the next session of Congress. Wilkinson had already sent home the militia who had reached Natchitoches, on the grounds of economy. He retained a force of 100 mounted dragoons.

Burr’s messenger, Samuel Swarthout, remained at Wilkinson’s camp for ten days. Swarthout said 7,000 men were expected to join Burr from New York and the western states and territories. Orleans Territory would then be “revolutionized,” and money seized from its banks would be used to outfit ships which would sail to Vera Cruz on the 1st of February. They expected naval protection from Great Britain and officers of the American navy were ready to join them. The general believed that British naval support would be forthcoming.577

Wilkinson continued to send out misleading information in support of Burr in October, while making preparations to defend Mississippi and Orleans Territory. He sent artillery to Fort Stoddert in Alabama and ordered a blockhouse built in New Orleans. Because there are contradictory documents, historians have said Wilkinson was wavering in his support of Burr, and only began to make up his mind at this time.

On October 20th, Wilkinson wrote to the president, enclosing an anonymous document, obviously written by the general:

A numerous & powerful association, extending from New York through the Western States to Territories bordering on the Mississippi, has been formed with the design to levy & rendezvous eight or ten thousand men in New Orleans at a very near period, and from thence, with the cooperation of a Naval Arrangement, to carry an Expedition against Vera Cruz—Agents from Mexico, who were in Philadelphia at the beginning of August, are engaged in this Enterprize; those Persons have given assurances that the landing of the proposed expedition will be seconded by so general an insurrection, as to insure the subversion of the present government….578

The general was perplexed as to who was really behind this enterprise. The combination of French revolutionaries and British naval support was unlikely, but believable. War ships in the invasion force—with the implied threat of attacking the fortress at Vera Cruz if it wasn’t peacefully surrendered—would be of enormous advantage. The revolutionaries were not connected to Napoleon. General Victor Moreau, because of his fame as a military leader had escaped execution, but he had been banished to the United States by Napoleon. The Federalists and British Loyalists of the Northern Confederacy and the Mexican Association had the connections for a British “Naval Arrangement”—as Burr himself had, through the Prevost family.

The simple answer is that everyone would want to be in on the invasion from the beginning because, literally, that’s where the money was—stored in the fortress at Vera Cruz. The hard currency of international trade was entirely based on the Mexican silver peso (dollar), mined and minted in Mexico.

After the Neutral Ground Agreement was signed on November 5th, Wilkinson sent his aide, Captain Walter Burling, on a mission to Mexico City. Burling brought a letter asking the Spanish government to pay Wilkinson 121,000 pesos for his efforts in defeating Burr’s expedition. The Viceroy of New Spain, José de Iturrigaray, returned the letter, thanking him and saying he was not authorized to pay it. Wilkinson’s real motive was reconnaissance. Burling traveled overland to Mexico City and returned by ship. The general wanted to know the routes and the state of military preparedness for Mexico’s capital city. Captain Burling was paid $1,500 for his travel expenses by the United States government.579

Wilkinson reached New Orleans on November 25th. Though others advised stopping Burr up river before he reached Natchez, or before he reached Baton Rouge where Spanish military supplies were stored, Wilkinson believed the story about British naval support and made his stand at New Orleans. He knew Burr was planning to take over the territorial government in a bloodless coup with the help of the Mexican Association. The leaders of the association were hostile to Governor William Claiborne and actively opposed him.

However, one of Burr’s major supporters, Daniel Clark, had deserted him. Clark was now the Territorial Delegate to Congress. In the middle of October, before leaving for Congress, Clark called together French leaders of the old establishment and told them to take no part in Burr’s plans and support the United States. Governor Claiborne assured Secretary of State James Madison of the “fidelity of the Ancient Louisianians to the U. States.”

After learning the true nature of Burr’s plans, Andrew Jackson wrote to Governor Claiborne on November 12th—

…—put your Town in a State of Defence, organize your Militia, and defend your City as well against internal enemies as external….—beware the month of December—I love my Country and Government, I hate the Dons [Spanish nobility] I would delight to see Mexico reduced, but I will die in the last ditch before I would yield a part to the Dons or see the Union disunited.580

Jefferson finally acted, issuing his Proclamation on Spanish Territory on November 27, 1806. The proclamation stated that citizens of the U. S. were unlawfully conspiring to begin a military expedition against the dominions of Spain, and warned them to withdraw from the criminal enterprise without delay. Civilian and military authorities were ordered to seize their supplies and detain all persons engaged in the enterprise.

Aaron Burr and Senator John Adair arrived in Nashville around December 12th. Although Andrew Jackson had learned enough of their plans from an unsuspecting confederate to alert Governor Claiborne in New Orleans, he still provided some help to Burr. Burr had paid for five boats to be constructed at Nashville. He got two. Jackson eventually refunded the difference. He was given a few supplies, but the 75 promised recruits failed to appear. At this time, the president’s proclamation was still unknown in the western country.

Burr and a few men, some horses, and the two flatboats arrived at the junction of the Cumberland and Ohio Rivers on the 27th of December. As Burr waited for Blennerhassett to join him, he sent messengers to nearby Fort Massac. (One of his messengers was a man named Mr. Hopkins—Mr. Hopkins would turn up again as an advance agent in Burr’s 1810 invasion plot.)581 Burr’s boats passed by the fort on December 30th, but he declined an invitation to visit, saying he was a “suspicious character” and wished to avoid causing further suspicion. He had already learned of the peace arranged by Wilkinson at the Sabine. Burr chose to believe that the general was still part of the conspiracy. Upon learning Wilkinson was in New Orleans, he thought the general was planning to start the invasion from there.

Harmon Blennerhassett and his men, and another group of men who joined them at the Falls of the Ohio, had arrived at the Cumberland with more bad news. The Ohio state militia had been called out against the conspirators on Blennerhassett Island. On December 6th, they seized ten of their eleven boats. Burr’s Kentucky treason trial and alarming stories in the newspapers were causing many to back out of the expedition. On December 10th, in the middle of the night, Blennerhassett and his men made their escape from the island on the remaining boat. The Ohio militia on the west shore and Virginia vigilantes on the east shore were preparing to stop them in the morning. The activities on Blennerhassett Island would form the basis of the federal government’s charge of treason again Burr. The island was chosen because it fell within the jurisdiction of the state of Virginia. (West Virginia didn’t become a state until 1863.)

Their combined flotilla had ten boats, with about a hundred men or more in the party. The boats were capable of carrying fifty men each. Fifteen boats had been left at Marietta and three at Nashville. Burr tried to recruit additional men as he traveled down river, and gained a few. On January 10th, they arrived at Bayou Pierre on the Mississippi River, about forty miles above Natchez (near today’s Port Gibson, Mississippi).

Burr visited his old friend Peter Bruin there. At Bruin’s home he read the latest newspapers, which carried Jefferson’s proclamation; Wilkinson’s version of Burr’s cipher letter to him; the Governor of Mississippi Territory’s statement that all conspirators should be seized; and the news that Wilkinson had arrested his co-conspirators in New Orleans. Burr was enraged. Finally he understood that Wilkinson had betrayed him.

Wilkinson had called out the militias when he arrived at New Orleans, repaired the fortifications, and impressed seamen. He arrested Erich Bollman and Samuel Swarthout for “misprision of treason,” or concealing knowledge of treason, and shipped them out on a war vessel to Baltimore. He did the same to John Adair and Peter Ogden. The city was in an uproar over this imposition of martial law.

At the same time, the general suffered a great personal tragedy. His wife Ann died of tuberculosis on February 23, 1807 and was buried in New Orleans. She had been seriously ill since the summer of 1806 in St. Louis. They had been married for 28 years. Wilkinson had been facing grave national emergencies and his wife’s terminal illness for months.

On February 3rd, the president wrote to Wilkinson, praising his activities. He wrote that they now knew Burr had ten boats; and that there were between 80 and 100 men in his party and there were 60 oarsmen, “not all of his party.” Jefferson wrote:

Although we at no time believed he could carry any formidable force out of the Ohio, yet we thought it safest that you should be prepared to receive him with all the force which could be assembled, and with that view our orders were given; and we were pleased to see that without waiting for them, you adopted the same plan yourself, and acted on it with promptitude….582

Jefferson was waiting to spring his trap, which added to the confusion as Burr traveled around the country. The $16,883.12 brought to the Sabine by Moses Hooke is the clearest indication the president wanted to avoid a war with Spain and Wilkinson was acting on advance instructions in negotiating the Neutral Ground Agreement. Jefferson originally supported Burr and Wilkinson’s filibuster activities because it was cheaper than war. Filbuster expeditions eventually did establish independent republics in West Florida in 1810, and in Texas in 1836–46, which were then annexed by the United States.

Historians have blamed the general and discounted Burr’s international intrigue in attempting to unravel the story of the conspiracy. Wilkinson was both an instigator and a collaborator, but it was an American-based conspiracy when he was involved. He was a die hard Federalist, who liked the Spanish people. He wanted to be in on the profits to be made in the revolution that would establish Mexico’s independence from Spain. He was ready to start a new country as part of the Northern Confederacy, and to lead the United States Army in an invasion of Mexico in the event of a war with Spain. He preferred seeing Burr as the leader of the country, and hoped it would happen.

What Wilkinson couldn’t abide, however, was the “infernal French.” It must have come as a shock to learn that Burr was working with the French. Jefferson was pro-French, but he was as firmly opposed to the French “revolutionizing” Mexico as his general was. It was all a question of neighborhood, and both men believed it should be an American neighborhood.

Burr surrendered to the Mississippi authorities on January 18th, 1807 and was taken to the town of Washington, just north of Natchez. Burr agreed to surrender on the condition it was to a civilian authority, rather than to the military authority of Wilkinson. Burr’s men hid their rifles under water until the boats passed inspection. They were entertained with balls and dinners in Washington, a wealthy planter’s town. The two judges hearing the case and a grand jury were Federalists and in full accord with Burr’s plan to attack Spanish territory. Their verdict, absolving him of all charges, was delivered on February 4th.

Wilkinson had offered a $5,000 reward for Burr’s capture in December. After Burr surrendered at Washington, Moses Hooke with five other men were sent to seize Burr and bring him back to New Orleans. They were dressed in civilian clothes, armed with pistols and dirks, and had no warrants. Burr escaped custody in the middle of the night on February 5th, forfeiting his bail bond of $10,000. A reward of $2,000 was offered for his capture by the Mississippi authorities.

Burr went into hiding, and sent a message to his men to keep together, put their arms in order, and he would join them the next night. The message was discovered hidden in the lining of a coat owned by Burr and worn by a slave who was sent to deliver the note. His men were arrested temporarily, forcing Burr to abandon his plans to reunite with them.

On February 18th, Burr and a companion, Robert Ashley—who had been with Philip Nolan’s group of adventurers in Texas—were spotted by a local man near Mobile, Alabama and captured. Burr was riding a “tackey” horse, and wearing a white floppy hat and homespun clothes in an attempt to disguise himself as a river boatman, but his piercing eyes betrayed him. Ashley escaped from confinement after his arrest.

Burr remained under arrest at Fort Stoddert for two weeks, playing chess with the commander’s wife. An eight man escort brought Burr to Richmond, Virginia on March 25th, to await his trial for treason. The trial will be discussed in the next chapter, as Meriwether Lewis attended it as President Jefferson’s observer. 583

Aaron Burr (1756–1836)

James Wilkinson (1757–1825)

Thomas Jefferson (1743–1826)

What was President Jefferson’s role in the Burr-Wilkinson Conspiracy of 1804–07? The following is a review of the new interpretations offered in this book—

Jefferson was aware that Burr and Wilkinson were meeting secretly and studying maps of the gulf coast and southwest in the winter months of 1804–05 in Washington D. C. Burr was his vice-president, and Wilkinson was the commanding general of the army. Burr’s term as vice president would end in March, 1805.

For over a year, secession from the union was being openly talked about by the northern states. In 1804, Burr had been defeated in his run for Governor of New York, and then had killed the founder of the Federalist Party, Alexander Hamilton, in a duel. Hamilton had opposed the secessionists and Burr’s election to the governorship. If Burr had become Governor of New York, he would have served as the leader of the breakaway states in a union with the British provinces of Canada.

When General Wilkinson met in secret with Burr at his home in New York City in May of 1804, he must have been willing to support the Northern Confederacy. For many years he had been pursuing the goal of revolutionizing Mexico. Wilkinson was a Federalist, with loyalties to Federalists officers in the army—the same officers Jefferson was replacing with his own Republican officers. The general was ready to switch sides.

Jefferson made a strategic move in the winter of 1804–05. He offered General Wilkinson the post of Governor of Louisiana Territory, based in St. Louis. The Louisiana Purchase—whose extent was unknown—had been divided into Orleans and Louisiana Territories. He did not appoint Burr to any federal posts, but gave his relatives and friends jobs in both territories. Many people were outraged by Jefferson’s giving the top civilian post to the general, saying it was a military dictatorship.

Jefferson was co-opting, or adopting for his own purposes, the plans of the Federalist secessionist movement. Burr and Wilkinson could revolutionize Mexico with a filibuster army including Burr’s civilian volunteers, western militias, and the U. S. Army. It would be an “undeclared war”with Spain if it happened—a spontaneous eruption against the hated Spanish Dons. The result would be an independent republic established by Americans, which would then become a United States territory.

Burr was to rehabilitate himself by becoming a senator from a western territory or state, and rehabilitate his finances by land speculation. He was uninterested in this solution. Burr went on a western exploratory tour in 1805, meeting with his close friend, Edward Livingston, the former Mayor of New York City, in New Orleans. Livingston was the leader of the Mexican Association, a group of 300 Americans who had moved to New Orleans after the Louisiana Purchase for the purpose of revolutionizing Mexico and other Spanish colonies in the Americas.

After visiting New Orleans during the summer, Burr met with Wilkinson in St. Louis in September, 1805 and revealed his larger goals. This is when the general pulled away from him, but pretended to remain on his side. Secretary of War Henry Dearborn warned Wilkinson about his association with Burr, saying, “You ought to keep every suspicious person at arm’s length, and be as wise as a serpent and as harmless as a dove.” Dearborn wrote this letter to the general on August 25th. He had received word of Burr’s dealings in New Orleans.

So, at this point, what was Jefferson’s position on the proposed invasion of Mexico? He opposed it in 1804 when it was a plan of the Northern Confederacy. He supported it in 1805 when he placed Wilkinson and Burr’s people in power positions. He opposed it again in 1806, when Burr began meeting with the British and Spanish ambassadors and French revolutionary agents in what would become a filibuster to start a new country.

As plans for the invasion progressed in 1806, Jefferson and Wilkinson kept silent. However, there must have been secret instructions to Wilkinson to arrange for a Neutral Ground Agreement with Mexican officials, and secret money was sent to him for this purpose. The silence of Jefferson and Wilkinson was to entrap Burr and his followers. Jefferson wanted to make certain there was enough evidence to convict Burr on treason charges. Was Jefferson worried about the loyalty of his general? It was only natural for him to be worried. But Wilkinson came through. He didn’t start a war; he betrayed Burr; he provided a strong defense of New Orleans; and he escaped an indictment for treason.

Wilkinson by this time had a long history of being involved in conspiracies. Sometimes he started them, and sometimes he busted them. Like Burr and Jefferson, he operated behind the scenes, and tried to have as much distance as possible from any events for which he might later be questioned. All three were masters of “deniability.”

In the 1790’s Wilkinson was a “conspiracy-buster,” defeating attempts by the British, French, and disaffected Mexican officials to organize filibusters to invade Mexico with the cooperation of Americans living in the west. The European wars; the existence of Indian lands yet to be acquired by the United States; the Spanish territories on the gulf; and the location of a cosmopolitan city, New Orleans, at the mouth of the Mississippi River were all reasons to organize revolutions. Above all else, there was the lure of the silver mines of Mexico.

There was no concept of “the United States.” Instead, it was “these United States,” or “the U. States”—as if united was a questionable concept. The states had been independent colonies of Great Britain less than a generation before. No one exactly knew what the authority of the federal government was. Jefferson and Madison had first questioned federal authority with the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions. The northern states were organizing a new confederacy. It was natural to think the lands between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans would be divided into independent countries, which could then be more easily governed.

The first Burr and Wilkinson Conspiracy to invade Mexico started with President John Adams’s decision in 1799 to seek a peace with France rather than continue the Quasi-War. Without Adams being aware of it, Wilkinson established the military cantonment near the junction of the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers called “Wilkinsonville.” During the hotly contested election of 1800, between Burr and Jefferson for the presidency, troops were stationed at Wilkinsonville. If Burr had won the presidency, the troops would have invaded Mexico. Philip Nolan and his men, waiting in Texas in 1800–01, were their advance agents.

When the Louisiana Purchase unexpectedly happened in 1803, the northern states were bitterly opposed because it permanently established the slave-holding states’s control of Congress. Louisiana Territory was cotton country and would eventually enter the union as slave states. The 3/5’s compromise of the U. S. Constitution counted slaves as “3/5’s” of a person in determining the number of congressional seats in the House of Representatives.

The northern states were ready to secede and start their own country. This new country would include not only the northern states and British provinces of Canada, but also the Spanish territories of the two Floridas, Texas, and Mexico with its silver mines. Wilkinson was ready to join with his Federalist friends to establish a new country. There was always a good chance they would later reunite with the United States.

The basic difference between Burr and Wilkinson is Burr was working with international associates in an open-ended scheme of revolutionizing Spanish colonies in the Americas and starting a new country with himself as the head of it. They were empire builders. After the treason trial Burr would head for Europe and continue planning another filibuster.

Wilkinson would continue to focus on a filibuster led by Americans that would revolutionize the Spanish territories. Burr and Wilkinson were now working independently of each other.

St. Louis to Washington, circa 1806–09, via the Ohio River and overland travel.