September 23, 1806 was the day that the Lewis and Clark Expedition arrived back in St. Louis to a heroes’ welcome. Sergeant Ordway wrote when they had arrived at the settlements two days earlier, the people “were Surprized to See us as they Said we have given out for dead above a year ago.” A St. Louis resident said they “really had the appearance of Robinson Crusoes—dressed entirely in buckskins.” Upon arriving at St. Louis they got quarters in town and began celebrating. The captains ordered new clothes from a tailor and began to pay formal calls. Dressed in buckskins, they were entertained at a dinner and a ball that evening.584

Meriwether Lewis had no idea he would be returning to St. Louis as Governor of Louisiana Territory in 1808. St. Louis was in the midst of the Burr Conspiracy and the threatening war with Spain in September, 1806. The Governor of Louisiana Territory, General Wilkinson, had gone with his troops to meet the Mexican army on the Sabine. Captain Zebulon Pike and the general’s son, Lieutenant James Biddle Wilkinson, were exploring the route to Mexico. Aaron Burr’s brother-in-law, territorial secretary Dr. Joseph Browne, was serving as acting governor, while the conspirators in St. Louis were preparing to bring 12,000 pounds of lead down the Mississippi to Burr. The arrival of the Lewis and Clark Expedition only added to the excitement.

The captains wrote their letters the next day. Lewis wrote a long letter to the president, and Clark copied a draft of Lewis’s letter to send to his brother, General Jonathan Clark, in Louisville. The letter to his brother would serve as the public account of their journey and safe return, and it would be reprinted widely in newspapers across the country. Lewis would spend the next weeks writing out pay warrants and discharging the men.

The captains were asked to examine evidence of land claim frauds by Rufus Easton, the U. S. Postmaster and U. S. Attorney for St. Louis. Easton wrote to Jefferson on December 1, 1806:

… the Books & Records of Soulard have been personally inspected by Captains Lewis & Clark, who will be the faithful messengers of their state & condition, and that they contain innumerable alterarations & forgeries! 585

Silas Bent, the U. S. Deputy Surveyor in St. Louis, who had replaced Antoine Soulard in mid September, wrote to the Surveyor General on October 5th that the records had pages cut out and others inserted, names erased and others inserted, and that—

… the Conduct of some of the commissioners appears rather extraordinary—they do but little Bussiness lately—the large Claims of from a League square to one million of acres I believe are generally fraudulent, Yet the Combination in favor of them is strong and Powerful and by their Opulence and influence may perhaps be able to bear down all those who dare to come forward and state facts respecting them.586

The three federally appointed land claims commissioners had begun meeting in December, 1805 to establish the legitimacy of Spanish land titles. Two of the commissioners were Wilkinson’s men: Clement Biddle Penrose, a nephew of General Wilkinson, and James Lowry Donaldson, a member of a prominent Baltimore family. The third was Judge J. B. Lucas, a French emigrant and friend of Albert Gallatin, Secretary of the Treasury. Lucas opposed the efforts of Wilkinson’s two commissioners to confirm the suspect titles held by the large land claimants. A great deal of money was at stake, and Wilkinson had favored the wealthy French families of St. Louis.

The Americans arriving in St. Louis resented the old residents’ preferential treatment and fraudulent claims, and wanted to invest in these lands themselves. On January 4th, 1807, after Meriwether Lewis arrived in Washington with evidence of the commissioners’ misconduct, President Jefferson wrote to Secretary Gallatin, “I have never seen such a perversion of duty as by Donaldson & Penrose.” He fired Donaldson and replaced him with Frederick Bates.587

The Lead Belt District in southeastern Missouri contains the highest concentration of lead in the world. The area was also a center of gun powder manufacture, which is made from saltpetre (potassium nitrate), sulfur, and charcoal. Lead is used to make bullets.

Many of the disputed land claims centered on the incredibly rich lead mine district. All land containing lead, salt, and salt petre was reserved for the federal government unless it had been previously acquired by a valid Spanish land grant. Moses Austin—the Virginia entrepenur who brought new mining techniques to the lead mine district in 1798—had become a Spanish citizen in order to acquire title to one league of land at Mine a Breton (Potosi). Moses Austin was the father of Stephen Austin, one of the founders of the Texas Republic.

When the United States established Louisiana Territory, John Smith T moved to Ste. (Sainte) Genevieve to enter into competition with Moses Austin in the lead mine district. John Smith had added a “T” to his name to distinguish himself from other John Smiths. The “T” stood for Tennessee. In Kentucky, Smith T had established Smithland near the junction of the Cumberland and Ohio Rivers in a partnership with Zachariah Cox in the 1790’s. At one time, Smith T claimed to own the “north half of the state of Alabama” in the Muscle Shoals area of the Great Bend of the Tennessee River, in what became known as the Yazoo land fraud.

Smith T was the most prominent “Burrite” in the St. Louis area. He was born in Essex County Virginia around 1770. His mother’s maiden name was Lucy Wilkinson. Smith family tradition is their family is related to General Wilkinson, and the general and the Smith brothers thought they were related.

Smith T’s brothers, Thomas and Reuben, were both West Point graduates. Thomas Smith became a respected brigadier general in the U. S. Army. For many years he and Smith T were not on speaking terms, as Tom Smith was the courier used by General Wilkinson to deliver Aaron Burr’s cipher message and other letters to President Jefferson in Washington. The papers were concealed in his boot.

Two days after reviewing the contents of Lieutenant Smith’s boot, on November 27, 1806, Jefferson issued his Proclamation on Spanish Territory forbidding citizens to plot against foreign governments, and calling for all participants to be arrested and their supplies confiscated. This directly affected John Smith T, who would soon be going down the Mississippi River with 12,000 pounds of lead for Aaron Burr.588

When Burr arrived at Smithland on the Cumberland River in late December, he sent word to Smith T at Ste. Genevieve. Smith T had purchased some $5200 worth of supplies from Andrew Jackson which were stored at Smithland for the filibuster. Jackson later sued him to recover the money he was owed.589

In January, 1807, Smith T set off from Ste. Genevieve with a flotilla of canoes to bring men, lead, munitions, and other supplies down the Mississippi to Burr at Natchez. His companions were Andrew Steele, Henry Dodge, and Robert Westcott. Westcott was the son-in-law of Dr. Joseph Browne, territorial secretary and acting governor in the absence of Wilkinson. Browne was the brother-in-law of Aaron Burr; he had married Theodosia’s half sister in a double wedding ceremony with Burr and Theodosia in 1782.

When Smith T and his associates arrived at New Madrid near the junction of the Ohio and Mississippi they learned of President Jefferson’s proclamation against the filibuster. Smith T sold the boats, lead, and supplies, and they returned on horseback to Ste. Genevieve. When they got back, they discovered a grand jury in Ste. Genevieve had indicted Dodge and Smith T for treason. After he posted bail, the 24 year old Henry Dodge, who was over six feet tall and strong, “whipped nine of the grand jurors,” according to John F. Darby, and “the rest ran away.”

Darby, who was Mayor of St. Louis in 1835, did law work for John Smith T. Darby wrote about him—

Col. Jack Smith T always went armed. He had two pistols under his coat in a belt around his body, generally two pocket pistols in his side-coat pocket, and a dirk in his bosom.

Darby reported that when the coroner Otho Schrader came with a writ to arrest Smith T at his house, Smith T said to him:

Mr. Schrader, dinner is just ready—get down and come in and take dinner; but, mark, if you attempt to move a finger, or make a motion to arrest me, you are a dead man.

They ate dinner together, with Smith T’s pistol cocked and loaded, laid on the table beside his plate pointing at Schrader. He was never arrested on the indictment.590

The travel writer Henry Marie Brackenridge visited Smith T and described him as a small man, of delicate frame, and somewhat effeminate in his appearance. Brackenridge called his gunsmith shop an “arsenal.” Smith T employed two slaves full-time to make and repair guns. His guns were famous for their accuracy. John F. Darby wrote—

It was said he killed fifteen men, mostly in duels, where his own life was in danger…. He was as polished and courteous a gentleman as ever lived in the State of Missouri, and “as mild-mannered man as ever put a bullet into the human body.” 591

Smith T had a fearsome reputation as a duelist, and employed a private army in his Mineral Wars with Moses Austin over the choicest claims in the lead mine district. The Mineral Wars raged for years in the Lead Mine District.

Lewis and Clark set out for the east coast on October 21st, amidst rumors of war with Spain and the Burr filibuster in progress. They had waited at St. Louis for Indian Agent Pierre Chouteau to arrive with a group of six Arkansas Big Osage chiefs who were going to visit the president. The travel group consisted of Lewis and his dog Seaman; Clark and his slave York; the Mandan chief Big White, his wife Yellow Corn, and their small son; the interpreter René Jessaume, his wife and their two small children; Pierre Chouteau and the six Osage chiefs; and former corps members, the mulatto François Labiche, who would serve as the French interpreter for Big White’s Mandan interpreter, and John Ordway, who was traveling with them on his way home to New Hampshire. Pierre Provenchere accompanied Chouteau.592

They traveled overland by way of Cahokia to Indiana Territory, where Governor William Henry Harrison entertained them at his Grouseland home in Vincennes. Lewis wrote a letter from Vincennes on October 30th. They arrived at the Falls of the Ohio on November 5th. They must have had a great time telling George Rogers Clark about their adventures. He was still living at his home overlooking the Falls in Clarksville, Indiana.

Clark’s sister, Lucy, who was married to William Croghan, gave a party at their home, Locust Grove, in Louisville on November 8th. William Clark Kennerly, a nephew of William Clark, recounted Clark family stories in Persimmon Hill. First of all, he says Clark said Big White was really big—that he was six foot ten inches tall. He related—

At Louisville, bonfires burned in their honor, and banquets and balls were given….The whole family gathered at Locust Grove, his sister’s house… York was in the quarters unpacking his Indian trophies to the “oh’s” and “ah’s” and prideful joy of his parents Old York and Nancy [actually his sister who was Croghan’s slave], the cook….York recited his adventures with dramatic pose. He took much pleasure, too, in the fact of the buckskins’ being abolished and in seeing his master again in ruffled shirt, silken hose and buckled pumps.593

The travelers split into three groups. Chouteau and the Osage delegation and Lewis and Big White’s entourage went to Frankfort, Kentucky, arriving there on November 13th. After that, Chouteau and the Osages went east from Lexington to Pittsburgh, and from there to Washington, while Lewis and Big White’s group went south to the Cumberland Gap.594

Clark remained in Louisville until December 15th. Clark’s arrival home coincided with major events in the Burr Conspiracy. The leader of the Burrites at the Falls of the Ohio, Davis Floyd, was the older brother of Sergeant Charles Floyd—who was the only man to die on the expedition. Davis Floyd was Burr’s quartermaster, and he had men armed with muskets and ammunition and boats loaded with supplies ready to join Burr.

Aaron Burr visited the Falls on November 27th, but there is no record of Burr meeting with Clark. Undoubtedly, some members of Clark’s family were involved in the conspiracy. Thirteen years earlier, in 1793–94, George Rogers Clark, as commander of the French Revolutionary Army, had recruited over 1,000 Kentuckians to join him in a similiar, failed invasion of Spanish territory during President Washington’s administration.

Later, Davis Floyd was one of the seven Burr associates who were indicted for treason and violating the Neutrality Act by the grand jury in Richmond in June of 1807. In fact, Floyd became the only person in the conspiracy ever to be convicted of anything—he was convicted of violating the Neutrality Act by an Indiana court, and jailed for three hours. Soon after that, he was appointed Clerk of the Indiana Territorial Assembly.595

On December 16th, Harmon Blennerhassett and his men arrived at the Falls after fleeing from Blennerhassett Island on December 11th. William Clark may have still be in the area, as he wrote on December 14th to his brother-in-law William Croghan at Locust Grove that he was going to visit Colonel Richard C. Anderson, who lived east of Louisville. When Blennerhassett arrived, Davis Floyd and his men joined him, and they left on the same day to join Burr at their meeting place on the Cumberland River near Smithland, Kentucky. About 100 men in ten boats arrived in Natchez where the filibuster was eventually stopped. When and where these boats joined together is uncertain.596

During November and early December, 1806, Burr had been involved in legal proceedings in Kentucky. He stood trial for treason in Lexington on December 5th, defended by Henry Clay. The charges were brought by U. S. District Attorney Joseph Hamilton Daviess, who had been sending warnings all year to President Jefferson about Burr’s activities.

It was fortunate for Burr he was brought to trial in Kentucky, as it ultimately allowed him to escape conviction for treason in Richmond, Virginia in the fall of 1807. The grand jury indictment at Richmond charged that Burr was the leader of the group of men who left Blennerhassett Island on December 11th, but Burr was in Kentucky with his court case. The charge of treason in the Kentucky court was dismissed for lack of evidence, and Burr and John Adair rode south to Nashville around December 10th. Andrew Jackson—who had changed his mind about Burr—gave him a cool reception, but he did supply him with two of the five boats he had ordered.

When William Clark left Louisville, York accompanied him on his journey east. York’s family was in Louisville. His father and mother, Old York and Rose, were owned by William Clark’s parents. Apparently York’s mother had died, but his sister Nancy was an enslaved cook of the Croghan family. York was married and his wife was owned by someone not related to the Clark family. It is not known whether they had children.597

William Clark had no official responsibilities for the expedition after it ended. He could do as he wished, and he went to Fincastle, Virginia to visit his prospective bride, Julia Hancock, and her family. He took the same route Lewis had taken a few weeks earlier through the Cumberland Gap in the Appalachian Mountains, and then rode north on the Great Valley Road.

Lewis and his party had stopped at the Cumberland Gap in order for Lewis to make a survey of the boundary line between Virginia and North Carolina. The original survey, Walker’s Line, had been done by Thomas Walker, who was married to Lewis’s great aunt. Around November 20th, Lewis spent two days taking new measurements, which resulted in the state of Virginia gaining an additional nine miles and 1,077 yards of land along its border with North Carolina. It must have given Lewis a great deal of satisfaction, no matter how eager he was to return home.598

Lewis and the Mandan party arrived at his mother’s home, Locust Hill, in Albemarle County on December 13th. Jefferson had written to Lewis urging him to take Big White over to Monticello to see the Indian artifacts displayed in his Great Hall—some of which the Mandans had given to the president. After spending Christmas in Albemarle, they arrived at the President’s House in Washington on December 28th. Chouteau and the Osage chiefs had arrived a week earlier, on December 20th.599

Clark arrived at Fincastle in late December. He may have attended the wedding of Harriet Kennerly on December 23rd. The 18 year old Harriet married John Radford. She was a cousin of 15 year old Julia Hancock, the girl Clark would marry a year later in 1808. Clark named the Judith River in Montana for Julia—Judith was her given name, but she was always called Julia. Clark had met Julia and Harriet in 1803 when Julia was 11 years old. He was 21 years older. Years later, in 1821, William Clark and Harriet would marry, after both of their spouses had died.

On January 8th, the citizens of Fincastle honored Captains Lewis and Clark.600 Clark then went to Washington, arriving on January 21st. He was too late to attend an affair held in their honor on January 14th, which had already been postponed once, waiting for his arrival. Clark’s position was now of an ambiguous nature. Even though the country referred to it as the Lewis and Clark Expedition, it was Lewis’s responsibility and he still had many matters to take care of—the financial accounting; managing the distribution of scientific and geographical information; and writing an account of their travel and discoveries for publication, which would be published under both of their names.

“Donation Land” was given to members of the Corps of Discovery as a reward for their services. Secretary of War Dearborn wanted to give 1,500 acres to Captain Lewis, 1,000 acres to Lieutenant Clark, and 320 acres to the non-commissioned officers and privates. Everyone on the expedition was to get double pay. However, Captain Lewis requested equal grants of land be made to himself and Lieutenant Clark, as he didn’t want to call attention to the distinction in rank between them.601

On March 3th, 1807, Congress authorized warrants for 1,600 acres of land each to be given to Lewis and Clark, and warrants for 320 acres to the others. Double pay was authorized. By this accounting, Lewis received $2,776.22 and Clark received $2,113.74. The men averaged $333.33 each. Drouillard earned $1,666.66 and Charbonneau, $818.32 as civilians.

Historian Arlen Large, however, discovered that later in the same year, Lewis and Clark received ample bonuses, resulting in a total pay of $4,932 to Lewis, and $4,538 to Clark. Part of Clark’s pay was a subsistence ration for his “black waiter.” Officers were entitled to have subsistence rations for at least one servant—slave or free. York had been Clark’s slave since their early boyhood together.602

Clark turned back his army commission to Secretary Dearborn after he arrived in St. Louis, saying it had “answered the purpose for which it was intended.” 603 He was still upset about not getting the captain’s commission promised by Jefferson. On February 28th Jefferson nominated Lewis as Governor of Louisiana Territory and Clark for promotion from first lieutenant to lieutenant colonel of the 2nd Infantry Regiment. The Senate approved Lewis’s nomination and rejected Clark’s promotion. The promotion was denied on grounds that several officers had greater seniority.

On March 12th, Secretary Dearborn nominated Clark to become the Brigadier General of the Territorial Militia in Louisiana, an appointment which was confirmed by the Senate. Clark had already been appointed “Agent for Indian Affairs to the Several Nations of Indians within the Territory of Louisiana excepting the Great and little Osages and their several divisions, and detachments.” The Chouteau family had been trading with the Osage for years, and after the U. S. acquired Louisiana, Pierre Chouteau was appointed U. S. Agent for the Osages. The Osage lived in western Missouri, Arkansas and Kansas.

Lewis was appointed superintendent of Indian affairs, as well as governor. After Lewis’s death Clark became the superintendent in 1813, a position he held until his death in 1838.604

William Clark, the day after he arrived in Washington, on January 22nd, wrote to his brother Jonathan that he had shared Jonathan’s recent letter reporting on Burr’s activities with the president. He wrote:

… the Expedition of Mr. B. has excted the greatest allarm and his views as are maid known the Exctve (and which will be laid before Congress tomorrow or the next day) are of the most desperate and violent nature aspect … Genl. Wilkinson has been giveing information to the Government for Some time …605

Clark would soon be directly involved with the Burrites, as he was going to St. Louis in his capacity as Indian Agent. Lewis would remain in the east for another year taking care of responsibilities regarding the expedition, and on special assignment for the president during Aaron Burr’s trial for treason.

Lewis wrote Clark a letter on March 13th, after Clark had set out from Washington to St. Louis via Fincastle:

Robert Frazier arrived here yesterday and from information which he brings with respect to Burrism in Louisiana the government have thought proper to avail themselves of your services should it be necessary for you to act by placing you at the head of the Militia of that Territory, and for that purpose have placed in my hands a commission for you as Brigadier General…. I shall write to Secretary Bates and request him to consult with you and take such measures in relation to the territory as will be best calculated to destroy the influence and wily machinations of the adherents of Col. Burr. It is my wish that every person who holds an appointment of profit or honor in that territory and against whom sufficient proof of the infection of Burrites can be aduced, should be immediately dismissed from office, without partiality, favor, or affection, as I can never make any terms with traitors. Mr. Robert Waistcoat [Wescott] son in law to Secretary Brown, Col. John T Smith and Mr. Dodge sherif of the district of St. Genevieve are highly implicated and there is good reason for believing that Mr. Brown himself might be sensured without injustice—Frazier will give you a more detailed account of those transactions than leisure permits me to give you at this moment.

I must subjoin a wish that you would make your dissertations on the subject of___to Miss___as short as is consonate with your amorous desires—for god’s sake do not whisper my attach to Miss___or I am undone.606

Adieu and believe me your sincere friend,

Meriwether Lewis

Governor of the Territory of Louisiana

Robert Frazier was bringing Lewis’s letter and his commission as brigadier general to Clark. Frazier, a former member of the expedition to the Pacific, was going to testify against Wescott in a trial for treason scheduled to be held in St. Louis in May.607 Robert Frazier himself wrote to President Jefferson on April 16th from Henderson County, Kentucky. In this letter he states that he is worried he will be assassinated by Smith T and his “junto” while traveling to St. Louis. Frazier was bringing incriminating documents with him that apparently would implicate them in the Burr Conspiracy.

… At Breckinridge court house I was informed of a number of inquiries that some of the party (dispached to overtake & wrest from me my papers) had been making relative to my business at Washington. I shall take proper measures to bring these sub-traitors if not to condign punishment, at least to a full exposure at the tribunal of my country. I also learned from a gentleman of high respectability, directly from St. Louis that Col. John Smith (T) will not suffer himself to be taken by the civil authority; but has threatened and reviled me with the harshest and most bitter epithets.

From this man’s character as a desperado & from the servility of a vile and desperate junto of which he is the head, I really think I am in no small danger of assassination, or some other means of taking me off. If they would face me fairly and openly, I would boldly confront them, and set them at defiance; but this is not their method of attack. I advised with several gentlemen on the subject of my personal safety before I arrived here, whom I knew were friends of the government, and who referred me to Gen. Hopkins. He advises me to travel by way of Vincennes; there being but few houses between there and St. Louis and the country chiefly prairie. That it is the safest I have not a doubt & have consequently adopted it.608

Frazier reached St. Louis safely, and both Smith T and Westcott were removed from the offices they held by Frederick Bates, the new territorial secretary and acting governor.

Frederick Bates (1777–1825) became the second governor of the State of Missouri in 1824. His home, Thornhill, is part of a historic village located in Faust Park, Chesterfield, MO, which is open for group tours. www.stlouisco.com (Wikimedia Commons)

Frederick Bates arrived in St. Louis on April 1st, replacing Joseph Browne, Burr’s brother in law, as acting governor and territorial secretary. Browne and his son, Robert, joined John Smith T and W. H. Ashley in the lead mining business.609 On April 28th, Bates wrote to Governor Lewis:

Nothing but the actual experience could have fully informed me of the extent of those duties and responsibilities, which in your absence, it will be necessary for me to take upon myself…. I have not yet experienced so much ill natured opposition as I had expected: Yet the minds of the factions are by no means tranquil…. all from contrary motives of hostility and friendship anxious for your arrival: For contrary to my first expectation you must expect to have some enemies.610

Bates made a tour of the lead mine district, visiting Moses Austin, during his first month. He wrote to his uncle he was planning to buy a farm in the lead mine district along with a few slaves, whom he would employ in digging for lead on the off season. A slave with a pick and shovel could make back his purchase price, $400, in a season. He couldn’t buy land immediately because land titles and lead mine leases were still uncertain.610

Bates received two additional federal appointments as the recorder of land titles, and as a member of the three man board of land commissioners. He was doing five jobs at once in Louisiana Territory—serving as territorial secretary, acting governor and superintendent of Indian affairs, recorder of land titles, and land claims commissioner.

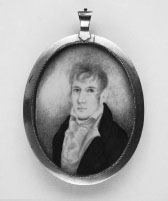

John Smith T (c. 1770–1836) in a miniature portrait. (Missouri History Museum, St. Louis)

The brother in law of Moses Austin was Moses Bates, a relative of Frederick Bates. The two Moses’s—Austin and Bates—had come from Connecticut to Spanish Louisiana in 1798 as partners in the lead mining business.611 Frederick Bates became associated with the Austin-Bates faction in the Mineral Wars, just as Wilkinson joined with Smith T’s faction. There were family connections in both cases.

Lead was found over a region of hundreds of square miles.The lead mining district had been declared public land in an 1804 act of Congress, but the law was not enforced. On March 3rd, 1807, Congress passed the Lead and Salt Leasing Act. Conflicts over this policy developed immediately. Existing large mining claims, such as Austin’s, would continue until the land commissioners decided their fate at a later time. All new mines opened since 1804 and all those digging for lead under the traditional rights of usage (“prescriptive rights”) were to cease operation and obtain leases from the federal government.

Leasing on public land was allowed for small tracts of land, from 40 to 320 acres, for up to three years. Bates, as recorder of land titles, was put in charge of granting leases. The newly appointed federal land agent, Will C. Carr, took over this responsibility in 1808. Those who got leases found their lands were still being illegally mined by others. John Smith T was notorious. He had purchased an original Spanish “floating land concession” from a French resident in 1806, giving him the supposed right to claim land wherever he wanted. It was a “wild card,” which he enforced with his private army. Austin had a private army of his own to battle him, but small mine operators were simply driven off their land.

A second act, also passed by Congress on March 3rd, 1807, instructed the commissioners to make no decisions about land containing a lead mine or salt springs which had no prior claims on it. The government was stalling for time as it tried to figure out what to do with the valuable mineral lands. The commissioners had to first determine whether the land in question did contain lead or salt, in order to exclude it from sale. It was obviously to the benefit of land purchasers to have their titles approved and any minerals on their lands ignored.613

The situation led to highly charged conflicts of interest, involving large potential profits in land speculation and mining. Since lead was used for making bullets, the lead lands were the focus of both the government and private filibusterers. Salt petre in caves also fell under this act. Salt petre (the excrement of bats, also known as potassium nitrate or fertilizer) was used for making gun powder. The lead district contained the highest concentration of lead in the world, and was also a center of gun powder production.

The land commissioners began the task of sorting out the complicated land claims of the original French inhabitants. The residents followed the traditional French Canadian custom of living in villages with homes and vegetable gardens surrounded by high fences to keep the pigs out. They farmed on long, narrow plots of land located next to each other in an agricultural commons area, and shared a common pasture for livestock. Land was shared in common for timber, maple sugar, and lead. In the off season for agriculture, they dug for lead ore and smelted it in open fire pits to pay their bills at the local store. This system had worked well for generations, and they settled any issues among themselves. The Spanish government had seen little need to sort out their land claims.614

William Clark, after spending time in Fincastle and obtaining permission to marry his young sweetheart, arrived in St. Louis in May, 1807. He would spend the summer in St. Louis performing his duties as Indian agent, and then take on a new assignment for Jefferson on his return trip east—excavating mastodon fossil bones from Big Bone Lick near Cincinnati for the American Philosophical Society. In January, Clark and Julia would marry at Fincastle. They would make St. Louis their new home in July, 1808.

During the summer of 1807—following the return of Lewis and Clark’s expedition the previous year with its news of the rich fur country on the Upper Missouri—several expeditions left St. Louis bound for the headwaters. Two of these expeditions employed former members of the Corps of Discovery.

The first was a joint military-trading expedition authorized by Secretary of War Henry Dearborn, who ordered Nathaniel Pryor to escort Big White and his Mandan party back home to their villages on the Knife River. Pryor, now an ensign (the lowest rank of commissioned officer), was to have “one careful, sober searjeant and ten good sober privates” assigned to him from Camp Bellefontaine. A private trading expedition of the Chouteau family was accompanying Pryor, which was authorized by Dearborn to trade with Indians from the Arikara Indian villages on the Missouri upwards. The U. S. would supply ammunition to the trading expedition.

On May 18th, Clark wrote to Dearborn that Pryor’s party would have 14 men, and young Auguste Chouteau was bringing 22 men to trade with the Mandan. However, a group of fifteen Sioux chiefs and warriors, from the “most numerous and vicious bands” had arrived in St. Louis recently, escorted by Pierre Dorion, who was intending to bring them to Washington. After several days of deliberation, the Sioux chiefs decided not to go to Washington. They wanted to return home with the nearly $1,500 worth of merchandise Clark had given them.615

Big White suggested the Sioux delegation should accompany them back up river. The combined expeditions now numbered either 106 or 108 people. There were 18 Indian men, 8 Indian women, and 6 children in the party, including Big White and his wife and child, and the wife and two children of interpreter René Jessaume.616

On June 1st, Clark reported to Dearborn that the expedition had left St. Louis and started up river. After the Sioux left them and the soldiers escorting them started back, Clark wrote there would still be 48 men in Ensign Pryor’s party, “fully sufficient to pass any hostile band which he may meet with.” 617

Clark’s optimism proved false—when on September 9th, Pryor and Chouteau faced some very angry Arikara Indians. The Sioux chiefs and their military escort had already left them. The Arikara had recently learned that their beloved chief had died the year before while on his visit to Washington, and they were also at war with the Mandan Indians.

The other expedition going up the Missouri with members of the Corps of Discovery was under the command of St. Louis trader Manuel Lisa. Lisa had started up river ahead of Pryor and Chouteau in April. When Lisa’s expedition of 42 men encountered the Arikara, they were allowed to continue only after they were forced to surrender half their trade goods.

When the Pryor-Chouteau expedition reached the Arikara villages, a Mandan woman, held captive by the Arikara, told Big White that Manuel Lisa had informed the Arikara that two boats were following his boat bringing the Mandan chief back home, and they were loaded with merchandise for the Arikara. The woman captive also told them that the Arikara intended to kill Big White and his escort, and planned to kill Manuel Lisa and his men on their return journey.

There were 650 Arikara warriors on the shore as the two boats of Pryor and Chouteau tried to pass by the Arikara’s two stockaded villages on opposite sides of the Missouri River. Dorion and Jessaume were on shore, essentially held hostage by the Arikara, as the boats traveled up to the second village. Pryor told Big White to barricade himself and his party with trunks and boxes in the boat cabin. Negotiations with a chief who had been friendly with Lewis and Clark proved futile.

The Arikara seized the cable of Auguste Chouteau’s boat, which was loaded with merchandise and had no soldiers on it. They indicated to Pryor that he could continue up river, but he didn’t believe them. The commander of the trading expedition, young Auguste Chouteau, was only fifteen years old. He and several of his men had gone on shore to negotiate with the Indians. Pryor told Auguste to “make them an offer.” Pryor wrote:

He at last did make them an offer, which, had they not been determined on plunder and blood, ought to have satisfied them. He proposed to leave half his goods with a man to trade them—

A battle then took place in which they were forced to retreat, and as they retreated down river they encountered gun fire from both sides of the river for about an hour. Sioux warriors were fighting alongside the Arikara. None of Pryor’s men were killed, but three were wounded. Four men of Chouteau’s party were killed and six were badly wounded. One of Pryor’s men was 22 year old George Shannon, the youngest member of the Corps of Discovery. Shannon, wounded in the battle, would eventually have his leg amputated in 1816. He used a peg leg for the rest of his life and became known as “Peg-Leg Shannon.”

Pryor told Big White he would escort him by land to his village, but Big White refused, because of the women and children accompanying him, and because René Jessaume had been badly wounded and needed medical attention in St. Louis.

The expedition returned to St. Louis in defeat. Nathaniel Pryor concluded at the end of his report to William Clark—

If my opinion were asked ‘what number of men would be necessary to escort this unhappy Chief to his nation,’ I would be compelled to say, from my own knowledge of the association of the upper band of the Sioux with the Ricaras that a force of not less than 400 men ought not to attempt such an enterprize—and surely it is possible than even One Thousand men might fail in the attempt.618

Meriwether Lewis spent the entire year of 1807 out east. He was a returning hero, and yet—in thinking about the remaining 34 months of his life—what about Seaman, his dog? Where was he? He was an important part of Lewis’s life. Seaman was a very special dog, a “sagacious dog,” the size of a black bear, who was always following Lewis around, according to the Nez Perce traditional stories. During the expedition there is no question where Seaman was—he was traveling with Lewis.

We know that he survived the expedition and wore a collar inscribed with these words:

The greatest traveller of my species. My name is SEAMAN, the dog of captain Meriwether Lewis, whom I accompanied to the Pacifick ocean through the interior of the continent of North America.

The inscription was included in American Epitaphs and Inscriptions, a book written by Congregational minister and historian Timothy Alden, and published in 1814. Alden copied the inscription from Seaman’s collar on display at the Masonic Museum in Alexandria, Virginia. Alden wrote that Seaman died of grief on Lewis’s grave in 1809, establishing that the dog continued to be Lewis’s companion.619

Meriwether Lewis traveled by horseback—Seaman could have accompanied him wherever he went. Did he go everywhere with him? It’s possible, but there is another possibility, because Lewis added a servant to his household when he moved to St. Louis, a servant from the President’s House named John Pernier.

We know nothing of John Pernier’s background, but his last name is associated with the beginnings of the Haitian revolution. The wealthy Pernier plantation north of Port au Prince was the scene of an early battle in which black fighters for independence achieved a victory in 1791.620 John Pernier could have been a “free man of color,” who came to the United States after that time. He was working as a servant for Jefferson in 1804–05, and paid wages as a “free mulatto.” 621 Since Jefferson employed only very highly qualified people at the President’s House, it seems likely Pernier could have been one of the many refugees fleeing Saint Domingue, who would have been employed as a servant at a plantation on the island. He spoke French. His language skills would have been helpful to Governor Lewis in St. Louis.

Lewis lived at the President’s House during his time in Washington. Did Seaman travel with Lewis to Philadelphia? It doesn’t seem likely he would have gone with him to Richmond for the Aaron Burr treason trial. Perhaps the dog was sometimes left in Pernier’s, or another servant’s care, in Washington.

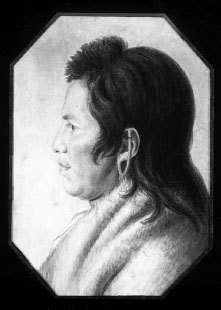

On December 30th, the Mandan chief Big White was formally welcomed by President Jefferson. On New Year’s Day the Indians attended the president’s Open House. In the evening of January 1st, the Indians themselves were a featured attraction at The Theatre in Washington. Big White and his wife Yellow Corn remained in the audience for most of the evening, viewing tumblers, acrobats and comedians. But when the Indians performed onstage, Big White, as “King of the Mandans,” sat on a throne and watched the Osage chiefs dance. He also attended the dinner given in Lewis and Clark’s honor on January 14th. After that, the Mandan chief’s party left with Pierre Chouteau and the Osage chiefs to return to Louisiana Territory. They visited Philadelphia where Big White and Yellow Corn had their portraits done by St. Memin before returning to St. Louis, and they probably visited Baltimore and New York.

There is no record about what Jefferson—who was of Welsh descent—thought about the Mandan-Welsh connection.622

Lewis was planning to write a series of books called Lewis and Clark’s Tour to the Pacific Ocean Through the Interior of the Continent of North America. A wall map of North America would be sold separately. The first part of the publication would consist of two volumes at a combined price of $10; the second part, one volume at $11; and the map, at $10. In April, 1807 his publisher in Philadelphia, John Conrad, issued a prospectus seeking subscribers to Lewis’s publications.

The prospectus announced that Part One’s first volume—

WILL contain a narrative of the voyage, with a description of some of the most remarkable places in those hiterto unknown wilds of America, accompanied by a map of good size, a large chart of the entrance of the Columbia river, embracing the adjacent country, coasts and harbours, and embellished with views of two beautiful cataracts of the Missouri; the plan, on a large scale, of the connected falls of the river, and also of those falls, narrows, and great rapids of the Columbia, with their several portages. For the information of future voyagers, there will be added in the sequel to this volume, some observations and remarks on the navigation of the Columbia and Missouri rivers, pointing out the precautions which necessarily must be taken, in order to ensure success, together with an itinerary of the most direct route across the continent of North America, from the confluence of the Missouri and Mississippi rivers to the discharge of the Columbia into the Pacific Ocean.

Part One’s second volume would contain—

WHATEVER properly appertains to geography, embracing a description of the rivers, mountains, climate, soil and face of the country, a view of the Indian nations distributed over that vast region, showing their traditions, habits, manners, customs, national character, stature, complexions, dress, dwellings, arms, and domestic utensils, with many other interesting particulars in relation to them: also observations and reflections on the subjects of civilizing, governing and maintaining a friendly intercourse with those nations. A view of the fur trade of North America, setting forth a plan for its extension, and showing the immense advantages which would accrue to the mercantile interests of the United States, by combining the same with a direct trade to the East Indies through the continent of North America. This volume will be embellished with twenty plates illustrative of the dress and general appearance of such Indian nations as differ materially from each other; of their habitations; their weapons and habiliments used in war; their hunting and fishing apparatus; domestic utensils, &c. In an appendix there will also be given a diary of the weather, kept with great attention throughout the whole of the voyage, showing also the daily rise and fall of the principal water courses which were navigated in the course of the same.

Part Two’s description of the third volume stated—

THIS part of the work will be confined exclusively to scientific research, and principally to the natural history of those hitherto unknown regions. It will contain a full dissertation on such subjects as have fallen within the notice of the author, and which may properly be distributed under the heads of Botany, Mineralogy, and Zoology, together with some strictures on the origin of Prairies, the cause of the muddiness of the Missouri, of volcanic appearances, and other natural phenomena which were met with in the course of this interesting tour. This volume will also contain a comparative view of twenty three vocabularies of distinct Indian languages, procured by Captains Lewis and Clark on the voyage, and will be ornamented and embellished with a much greater number of plates than will be bestowed on the first part of the work, as it is intended that every subject of natural history which is entirely new, and of which there are a considerable number, shall be accompanied by an appropriate engraving.

Lewis and Clark’s Map of North America would measure 5 feet 8 inches by 3 feet 10 inches, and be published separately. The three books would be 400–500 pages each, and along with the map, would be printed in Philadelphia and available for sale around the country at specified locations.

Meriwether Lewis informed his potential subscribers that no payment would be required of them until the books and map were available for delivery, and explained that he was setting a moderate price. He was asking for subscriptions mainly so he could make an estimate of how many copies to print. He cautioned the price of the second part might have to be increased, depending on the number of engravings. Subscribers soon began responding from around the country. 623

Rumors of the impending publication of Sergeant Patrick Gass’s unauthorized account of the journey infuriated Lewis and Jefferson. Gass’s book was going to sell for $1. Gass’s text was highly edited, or “expurgated” by his publisher, and his original journal has never been found. The woodcuts which appeared in its second edition were almost certainly created by Gass.624

Lewis wrote an open letter which appeared in a Washington newspaper on March 14th. Historian Paul Cutright in his History of the Lewis and Clark Journals says Jefferson had a hand in writing the letter, as some words were not part of Lewis’s vocabulary (i.e., “promulgation” and “subjoined”) and there were other indications of Jefferson’s style.625 Unfortunately, in his public letter, Lewis promised to have his first volume ready for sale in January, 1808, and the large map ready for sale by the end of October, 1807. It was a highly unrealistic plan, and the projected dates were undoubtedly influenced by the publication of Gass’s book, which did come out in the summer of 1807.

Meriwether Lewis had been elected to membership in the American Philosophical Society before setting out on the expedition. Thomas Jefferson was the president of the American Philosophical Society from 1797 to 1814. There is no question that both of them considered the announced publication would become the premiere work of American scholarship, and that they were very proud of it. On March 22nd, Jefferson wrote to a fellow botanist, praising Lewis’s accomplishments in the field of botany, and sharing some of the seeds that Lewis had brought back for the development of “useful or agreeable varieties.” He wrote about Lewis’s other accomplishments—

He will equally add to the Natural history of our country. On the whole, the result confirms me in my first opinion that he was the fittest person in the world for such an expedition.626

In October, 1806, Lewis had authorized the publication of Robert Frazier’s journal. But upon examining Frazier’s proposal, he took back his promise that he could include certain information about natural history. In his letter to the public, Lewis said Frazier could not possibly give accurate information about the celestial observations, mineralogy, botany, or zoology of the expedition, and what could be expected from his journal was “merely a limited detail of our daily transactions.” 627 Lewis’s criticism must have persuaded Frazier to drop the project, because his journal was never published, and is lost to history.

Although Lewis was going to author the three volumes, he was going to share equally in its “honors and rewards” with Clark. Clark would handle the making of the large map. The two men split the cost of buying Sergeant John Ordway’s journal from him for $300, and intended to split the profits. Ordway’s journal was an important reference, as he was the only writer to make entries for every one of the 863 days of the expedition.628

As time has gone by—and as one great editor after another has tackled the task of working on the materials of the expedition—it is easy to understand Lewis’s reluctance to work on it part time. When he began assembling materials, he must have realized it would require his full attention for a number of years and he would need to live in Philadelphia. It was very different in concept than simply publishing the journal entries.

Jefferson had put an impossible obstacle in Lewis’s way by appointing him governor of Louisiana Territory, superintendent of Indian affairs, and commander of the militia in St. Louis. When he finally did depart for the east coast in 1809, after his 18 month stay in St. Louis, he intended to stay out east and focus on getting the books and map ready for publication.

Nicholas Biddle in Philadelphia took over the task of preparing an account of their travels after Lewis’s death, consulting with William Clark and George Shannon as he worked. Biddle used Gass’s model of daily entries, with no attempt to present a larger overview. The Biddle edition(1814) and Gass’s journal, (1807), remained the only published accounts of the expedition until Elliot Coues’s edition was published in 1893. Coues was the first editor to include natural history information.

William Clark had completed the large map by December, 1810, which was also published in 1814. Clark offered Biddle one half share of the profits, and later arranged that Lewis’s share (now one quarter) would go to his mother. The first publisher, Conrad, went out of business. Nicholas Biddle, who was beginning a political career, turned over the project to another editor, Paul Allen, and paid him $500 for his work. Biddle told Clark he would not accept pay for his own work. Less than 1,500 copies of the two volume History of the Expedition Under the Command of Captains Lewis and Clark were printed and they sold poorly in 1814. The second publisher, who also went out of business, explained that there were no profits to be had from the sale of the books.629

The scientific information was omitted by Nicholas Biddle, because it was going to be published in a separate volume authored by Philadelphia physician, Dr. Benjamin Smith Barton, who had trained Lewis in botany before the expedition. Lewis discussed his natural history material with Barton after the expedition, and intended for Barton to assist him in writing the third volume devoted to scientific research. Dr. Barton, who was in failing health, died in 1815.

The science material was never was fully published until the Moulton edition was published almost 200 years later. Editor Gary Moulton has written that Biddle’s omission of the scientific data “established a view of the expedition, common to this day, as primarily a romantic adventure.” It is a great popular story, but the lack of understanding of its scientific mission is another factor affecting the reputation of Meriwether Lewis.

Many suicide theorists point to Lewis’s supposed inability to publish his account of their travels as an indication of depression, and as a reason why they believe that he committed suicide. But they are overlooking the complex nature of his project and how long it would take to complete it. It took over twenty years for Moulton and his team of research associates to do justice to the entire body of material, including all of the known journals. The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, were published in a series of thirteen volumes in 1982–2001 by the University of Nebraska Press.630

Meriwether Lewis set off for Philadelphia in April of 1807. Over the next few months he must have enjoyed himself greatly. He sat for his portraits with Charles Willson Peale and Saint-Memin. He attended meetings of the American Philosophical Society with his friend Mahlon Dickerson. He made a new friend, the bird artist, Alexander Wilson, and met with him and other members of the scientific and artistic community in arranging for the publication of his materials.631

He tried to find a woman who would marry him and move to St. Louis. Lewis was 32 years old. He needed a wife who would be comfortable in the social circles in which he moved, a good Republican wife. He was an extraordinary young man—a celebrity, with a bright future ahead of him. He had just returned from three years of exploration, and was absorbed in preparing an account of his experiences for publication.

What kind of future could a young woman expect with him? In a few months time he would be assuming the responsibilities of governing Louisiana Territory. St. Louis was very far away. The Aaron Burr Conspiracy was just coming to its end, and threats of war with Britain and Indian attacks were a constant worry. Philadelphia was one of the most sophisticated cities in the United States. It would have taken an equally extraordinary woman to marry him under these circumstances, based on an acquaintance of a few months. It was much more reasonable to wait until his life had settled down before he found a wife.

In any event, Jefferson assigned him another responsibility—attending the Aaron Burr treason trial in Richmond, Virginia. Lewis had expected to be in St. Louis by October 1st. He had written to Auguste Chouteau to have Gratiot’s house prepared for his arrival by that date, or to help him find another house to rent if he couldn’t afford Gratiot’s house.632 Under that timeline, Lewis would have been traveling to St. Louis in early August.

On July 31st, the accountant for the war department, William Simmons, asked Lewis to explain in writing if any of the provisions for the expedition should be charged personally to Lewis or to Clark. Simmons asked for an explanation of more than 30 ledgers of expense records. On August 5th, Lewis submitted his account of expedition expenses totalling $38,722.25. These records place Lewis in Washington at this time. 633

Lewis attended the treason trial of Aaron Burr in Richmond, which began on August 3rd. He must have left immediately after submitting his financial accounting to Simmons. He stayed in Richmond until Burr’s second trial for high misdemeanor ended on September 14th.

The trial had several phases. It was presided over by Jefferson’s enemy—who was also his distant cousin—the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, John Marshall. Burr arrived at Richmond, under arrest, on March 26th, 1807. On April 1st, Judge Marshall, after hearing evidence, scheduled a trial for a crime of “high misdeameanor” rather than “treason.” Jefferson took offense at this, and sent inquiries around the country, asking people to supply evidence of treason.

The initial evidence of treason was based on Wilkinson’s account of Burr’s plotting western secession and civil war, and Jefferson’s own declaration that Burr had committed treason. The critical point was whether there was an “open assemblage of men” for the purpose of moving against a territory of the United States. Filibusters against a foreign power did not constitute treason. The charge of “high misdemeanor” was for organizing a military action against Spain in violation of the Neutrality Act of 1794—that is, the filibuster planned against Mexico.

Enough of Wilkinson’s actions were questionable that the charges against Bollman and Swartwout—the conspirators he had arrested in New Orleans—had been dismissed in previous hearings held by the high court. Justice Marshall was now acting in his capacity as a Virginia circuit court judge when a grand jury was convened in Richmond. A Virginia court was necessary in order to establish a location for where the act of treason had occurred, in this case, Blennerhassett Island on the Ohio River.

The grand jury, on June 24th, indicted Aaron Burr for both treason and high misdemeanor, setting the framework for one of the most famous trials in American history. The jury interrogated 29 witnesses, including the main government witness, General Wilkinson. The general himself was almost indicted, for misprision (concealment) of treason and high misdemeanor. The vote was 7 for his indictment and 9 against. Jefferson was subpoenaed to appear in court and turn over letters in his possession, but he refused on the grounds of separation of powers—the court could not compel a sitting president to appear.

Jefferson remained at Monticello in Albemarle County. The population of Richmond, 6,000, nearly doubled in size during the trial. According to one estimate there were “no less than two hundred persons in Richmond”—witnesses, jurymen, and lawyers—who had some official connection to the trial.634 The trial for treason began on August 3rd. The charge of treason was limited to what occurred on December 11th on Blennerhassett Island, and as to whether its participants were overtly acting to start war against the United States. The other issue was whether Burr, who was not present on the island, could be convicted of treason. Justice Marshall delivered an opinion that what happened on the island was not an overt act of war against the United States.

This was an important legal opinion, because it established that under American law, a conspiracy to commit treason was not enough to bring charges. There had to be an actual overt act. On September 1st, the jury after deliberating 25 minutes, delivered its qualified verdict—

We of the jury say that Aaron Burr is not proved to be guilty under this indictment by any evidence submitted to us. We therefore find him not guilty. Aaron Burr was outraged and demanded he be judged “guilty” or “not guilty.” However, Marshall let the jury’s verdict remain on record, while entering it as “not guilty.”

Jefferson was even more outraged. He instructed his lawyers that no witnesses be paid or allowed to depart until their testimony was put into writing. A second trial for Burr, on the charge of violating the Neutrality Act began on September 9th, with a new jury. The trial fizzled out, with a verdict of “not guilty” delivered within a week. The government tried once more, accusing Burr of treason at the Cumberland River, and asked Marshall, as chief justice to arraign Burr and others for a new trial in a western circuit court. Burr complained this was the sixth trial he had had to endure on the same charge (two in Kentucky, one in Mississippi, and three in Virginia). The trials at Richmond ended on October 30th. The trial in a federal court in Ohio was finally abandoned by the government.

In June of 1808 Aaron Burr left the country bound for Europe, to try his luck again.635

Sometime during this period of time, Lewis wrote a lengthy paper he entitled, Observations and reflections on the present and future state of Upper Louisiana, in relation to the government of the Indian nations inhabiting that country, and the trade and intercourse with same. By Captain Lewis.

Observations and Reflections has the same name and content that he proposed to publish in his second volume. There is no manuscript known to exist. It was published by Nicholas Biddle as an appendix to the Lewis and Clark Journals in 1814. Lewis used some of its material in a letter he wrote to Secretary of War Dearborn in 1808 when he was in St. Louis, and used parts of it in a newspaper article that appeared in the Missouri Gazette in August, 1808 signed “Clatsop.” 636

At the end of the second trial, Lewis left for Albemarle. General Wilkinson wrote a letter to Jefferson on September 15th, saying he had intended to send Captain Zebulon Pike’s report to the president by Lewis, but he had been “too occupied” to get it ready.637

By October 8th, Lewis had returned again to Richmond. The hearing, as to whether there should be a trial in a western circuit court, was still going on. Lewis stayed in Richmond through October 20th, settling financial matters, which were negotiated by William Wirt, the government’s chief prosecutor. Lewis’s account book is his private record of money, dates of transactions, and names. The reason for the transactions is rarely stated. It seems likely he was settling accounts for the president. He then returned to Albemarle. It was only two or three days journey from Richmond to Albemarle on Three Notched Road. 638

Lewis was able to support the education of his 22 year old stepbrother, John Hastings Marks, who was going to Philadelphia to study medicine. On November 3rd, Lewis wrote to his friend Mahlon Dickerson in Philadelphia, asking him to cover John Marks’s expenses as Lewis was temporarily short of funds. He would pay Dickerson back, and reimburse him for any future expenses for Marks.

Lewis then gossiped about his love life, writing—

… [I] am now a perfect widower with rispect to love. I feel all that restlessness, that inquietude, that indiscribable something common to old bachelors … Whence it comes from I know not, but certain it is, that I never felt less like a heroe than at the present moment. What may be my next adventure god knows, but on this I am determined, to get a wife. 639

Lewis and his 30 year old brother Reuben Lewis set off for St. Louis soon after making arrangements for John Marks. Reuben was relocating to St. Louis, where he would enter the fur trade. The two brothers were accompanied by John Pernier, who was entering employment with Meriwether Lewis as his servant, and Lewis’s dog, Seaman.

The Lewis brothers stopped in Fincastle in November. Clark had written to Lewis in April about a “most lovly girl Butifule rich possessing those accomplishments which is calculated to make a man happy.” Her name was Letitia Baldridge, but she was already in love with another man and she left Fincastle two days after the Lewis brothers arrived, not wanting to give Meriwether false hopes. In July of 1808, Lewis learned from his friend William Preston that Letitia was “off the hooks” and had married Robert Gamble, Jr., in Richmond. Lewis had known Gamble since he was a boy. Lewis wrote that her new husband, was—

a good tempered, easy honest fellow … both his means and his disposition well fit him for sluming away life with his fair one in the fashionable rounds of a large City. such is the life she has celected.640

On February 15th, 1808, Lewis wrote to their mother from Louisville, Kentucky. He said he had been “near two months traversing this state” locating and surveying the land claims belonging to himself, his stepbrother John Marks and stepsister Mary Marks. On February 10th, Reuben had set out by flatboat with Pernier, bringing Lewis’s baggage and his carriage to St. Louis. Reuben and Pernier would go part of the way by boat and then go overland. Lewis himself was setting out the next day and expected to arrive in St. Louis about the same time.641

While Lewis was in Louisville, he engaged the services of Joseph Charless, a printer. After they both arrived in St. Louis, on April 29th, he loaned Charless $100, and advanced him another $125 he had obtained as newspaper subscriptions for the soon to be published Missouri Gazette.

The printing press arrived with William and Julia Clark in early July. Meriwether Lewis had almost certainly bought the press in Philadelphia from Adam Ramage, the leading manufacturer of printing presses in America.642

Charless set up the printing press, and published the first issue of the Gazette on July 12th. On July 22nd, Lewis, who had appointed Charless the Printer to the Territory, made out a draft on the Secretary of State for $500 to purchase paper for printing the Laws of the Territory of Louisiana (250 copies in English and 100 copies in French). Charless returned to Louisville to buy the paper and look after his printing business there. His young assistant, Jacob Hinkle, did the printing in St. Louis.

The first fifteen issues of the Missouri Gazette list Joseph Charless as the printer—not the publisher—of the newspaper. On September 21st, issue number 16, listed him as publisher. Meriwether Lewis was actually serving, anonymously, as the editor and publisher of the first newspaper published in Louisiana Territory. Two issues were combined in September, due to the “serious illness of its editor.” Lewis was suffering from malaria.

A strong indication of Lewis’s silent partnership in the newspaper business is that Charless changed the name of the newspaper to the Louisiana Gazette, shortly after learning of Meriwether Lewis’s death. It began publication under its new name on November 30th, 1809.643

For several years Charless’s newspaper in Louisville ran an ad seeking subscribers for the Missouri Gazette. The ad stated:

A capable Editor is employed, and a number of Gentlemen have volunteered to devote their leasure hours in writing on such subjects as will enrich its columns. Essays on indian antiquity, Mines, Minerals, and an account of the Furtrade, with Topographical Scetches will be diligently sought after.644

Jacob Hinkle supposedly edited and published the issues of the Missouri Gazette during this time. In November, 1808, one week after Charless had returned to St. Louis, Hinkle ran off with $200 worth of goods and $600 collected for newspaper subscriptions. To aid in his capture, Charless wrote the following description of his young printer—

This hopeful Sprig is about 24 years old, 5 feet 9 or 10 inches high; he shuffles as he walks; has a shallow complexion, black and curled hair, is cross eyed and very near sighted; in short, Dame Nature never formed his countenance to deceive [tho’ sad experience proves that he has outwitted even her in that respect’ for she plainly stamped The Villain in every lineament thereof. 645

Lewis had rented one of the nicest houses in St. Louis, which he offered to share with William and Julia Clark. Their first child, Meriwether Lewis Clark, was born here on January 10, 1809.

The house was located at South Main and Spruce Streets across the street from the Government House. It was quite a large and modern residence for its time, 40 x 20 feet, having two chimneys, glass windows, and rooms decorated with wall paper and oil paint—the first residence in St. Louis known to use wallpaper. It had four rooms on the ground floor, a large cellar, and an attic room for slaves to sleep in. There was a kitchen building and a smokehouse in the back yard. The yard had an excellent water well, fruit trees, and a vegetable garden. The well was a special feature. Most residents hauled water from the river because the town was built on limestone rock, and large cellars were a rarity.

On the double lot there was a stone warehouse, 16 x 60 feet, which became the first Masonic Lodge in St. Louis. The lodge, founded and presided over by Meriwether Lewis, met here from 1808–1811. The warehouse would have also been used as a gathering place for the militia and as an Indian Council House. Clark stored mercantile goods here.646

William and Julia had brought a number of slaves with them. He wrote to his brother Jonathan about his troubles with them on July 21st, 1808, three weeks after arriving in St. Louis:

I have hired out Sillo, nancy, Aleck, Tenar & Juba,—Ben is makeing hay, York employed in prunng wood, attendng the garden, Horses &c. &c. Venus the Cook and a very good wench Since She had about fifty [lashes], indeed I have been obliged [to] whip almost all my people, and they are now beginning to think that it is best to do better and not Cry hard when I am compelled to use the whip. they have been troublesom but are not at all so now—647

The Clarks were accompanied by his 18 year old niece, Ann Anderson, when they arrived in St. Louis. The bachelors in St. Louis flocked around Ann, but by October, she wanted to return home to Louisville. Clark was upset about her going because 16 year old Julia was pregnant and homesick herself. He wrote to his brother Jonathan on November 9th that Nancy [Ann] was about to return to Louisville.648

He also wrote—

Govr. Lewis leaves us Shortly and we Shall then be alone, without any white person in the house except our Selves. I shall Send york with nancy, and promit him to Stay a fiew weeks with his wife, he wishes to Stay there altogether and hire himself which I have refused. he prefurs being Sold to return [ing] here, he is Serviceable to me at this place, and I am deturmined not to Sell him, to gratify him … if any attempt is made by york to run off, or refuse to provorm his duty as a Slave, I wish him Sent to New Orleans and Sold, or hired out to Some Severe master until he thinks better of such Conduct I do not wish him to know my deturmination if he conduct[s] [himself] well This Choice I must request you to make if his Conduct deservs Suverity.649

On November 24th, he wrote to Jonathan:

Govr. Lewis is here and talks of going to philadelphia to finish our books this winter, he has put it off So long that I fear they will [not] bring [?] us much. I wrote to you the other day about york, I do not wish him Sold if he behaves himself well …—he does not like to Stay here on account of his wife being there. he is Serviceable to me here and perhaps he will See his Situation there more unfavourable than he expected & will after a while prefur returning to this place….

This morning Charless Comes with a Sour Countinonce and tells me Hinkle has run off in his debt $240….[he] has contrived to clear out about $1000 in debt…. I am a little Supprised that this fellow Should have been So Suckcessfull.650

York statue by sculptor Ed Hamilton is located near 5th & Main Sts. in Louisville, Kentucky. www.edhamiltonworks.com (Photo by Rick Blond)

On December 10th, 1808 he wrote:

I wrote to you in both of my last letters about York, I did wish to do well by him—but has he has got Such a notion about freedom and his emence Services, that I do not expect he will be of much Service to me again; I do not think with him that his Services has been So great (or my Situation would promit me to liberate him)… he could if he would be of Service to me and Save me money, but I do not expect much from him as long as he has a wife in Kenty. 651

In 1810 York was hired out as a wagon driver in Louisiville, with Clark receiving payment for his services. In November, 1815, he was working for William Clark and one of Clark’s nephews driving a wagon in Louisville. The only other mention of York is an account by the writer Washington Irving who visited William Clark in 1832. Clark told Irving that, after he finally freed him, York became an independent wagon driver in Nashville, Tennessee. He said York had failed in his business, and was planning to return to St. Louis to work for Clark when he died of cholera in Tennessee. Historian James Holmberg speculates York may have gone to Nashville because his wife was taken there by her owner, and he may have died around 1820–26 when cholera epidemics were prevalent in the region.652

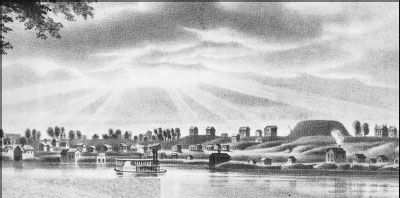

Lewis’s Great Mound is seen on the right. It was 130 x 120 feet on its flat top and about 12 feet high.

It seems unlikely that Lewis took separate quarters from the Clarks, as he was still living with them in late November, 1808. The Government House and the printing office were across the street, and the Masonic Lodge was next door.653

In 1808, there were about 1200–1400 people living in St. Louis. It was called “Mound City” because of its old Indian mounds. Cahokia Mounds, across the river in Illinois, is one of eight World Heritage Sites in the U. S. In 1050–1200 A. D., Cahokia was the center of one the largest cities in the world, with a population of 10,000–20,000. Over 120 mounds were built at Cahokia by the residents who hauled dirt in baskets to build them. They lived on the mounds and on the surrounding land. The largest mound, the 100 foot high Monks Mound, was named for Trappist monks who lived there in 1809–13. Mounds were a solution to the problem of annual river flooding.

Meriwether Lewis, as governor, was required to own at least 1,000 acres of land in the territory. Within two months of his arrival he had purchased the Great Mound in St. Louis and several more mounds lying near it, totalling 42 acres. Historian Grace Lewis Miller says Lewis probably intended to build a museum on the Great Mound. All of the mounds in St. Louis were eventually leveled.

Before the end of the year, on December 1st, 1808 he wrote to his mother he had purchased a total of 5,700 acres north of town.654 One tract was 3,000 acres and she would have 1,000 acres of it. Her tract had a comfortable three room house, an enclosed garden, a good well, horse stables and other improvements, a 40 acre enclosed field, and three springs. He proposed to give her the 1,000 acres in either a life estate or fee simple, in return for relinquishing her Dower Rights to the Ivy Creek property in Albemarle County. Lewis, as the oldest son, had inherited the property after his father’s death, but his mother had the right to use it and receive income from it during her lifetime.

Lewis had paid about $3,000 for the new property. An additonal payment of $1,500 was due in May, 1809, and a final payment of $1,200 on May 1, 1810. For this reason, he had to sell the property on Ivy Creek. Lewis was intending to put down roots in St. Louis and was planning that their mother—and perhaps their siblings—would join him and Reuben in their new home in Louisiana Territory.654

Actual hard currency was in very short supply in St. Louis. Most transactions consisted of handwritten “drafts” in which it was stated the amount one person owed to another person for supplying goods or services. These drafts would change hands several times, with stores and businesses accepting them in lieu of money. The drafts could be cashed for bank notes in other cities. St Louis’s first bank was established in 1813, with lead, fur, and skins being accepted as deposits.

Lewis’s salary as governor was $2,000 a year. When he paid for goods or services on behalf of the government, he wrote a “bill of exchange” and sent it to Washington. If the government refused to pay the debt, he was personally liable for the amount.

Fortunately, Lewis was a “master of mathematical detail,” as historian Thomas Danisi has commented in reviewing his fiscal records, because his transactions, both personal and as governor of the territory, were very complex. The penny-pinching conduct of William Simmons, the government’s chief accountant made his financial affairs even more difficult. Simmons, for example, had examined Lewis’s total of $38,722.25 in expenses for the expedition, and decided Lewis owed the government $9,685.77 because of inadequate records. Lewis was unware that a suit would be filed against him in three years time by the government. He would have discovered it when he arrived at Washington and began dealing with Simmons. After his death, his so-called debt for expedition expenses was expunged from the record in 1812.655

Simmons was challenging the expenses of all federal officials on the western frontier because the government was broke. In December, 1807, President Jefferson had imposed an embargo forbidding American ships to trade in foreign ports. His purpose was to avoid declaring war against Great Britain. Americans were outraged because British ships were impressing (taking) sailors off American ships to serve on their ships. Jefferson thought the embargo was the best alternative to war. An embargo would bring economic pressure to bear against Britain, and allow time for American ships to return home before any war might start.

The result of the embargo, however, was that smuggling by American ships flourished in 1808. It emboldened the Northern Confederacy to continue their plot to secede from the federal union. The embargo directly affected Massachusetts and the other northern states dependent upon commercial shipping. When James Madison became the fourth president of the United States in March of 1809, he sought to conciliate the factions in the northeast by appointing them to positions of power.

It was against this background of escalating tensions—and a change in administrations—that Governor Lewis was charting the destiny of his distant territory. He set logical goals, and was accomplishing them. They were based on the principles he shared with Jefferson and other founders of the Early Republic.

He brought a printing press and a printer to St. Louis so the Laws of the Territory could be printed and a newspaper could be established. He edited the paper and wrote news and analysis under assumed names (Clatsop, Enquirer, Reporter), which was standard practice in those days. It was a four page weekly. His militia orders, proclamations, and other state papers were published in the newspaper and signed by him as governor. News of foreign wars raging on the continent were reported, and articles and essays on various topics reflected his interests. Other contributors also wrote articles.

He founded the first Masonic Lodge in St. Louis in August, 1808 and served as its first grand master.

He presided over two sessions of the territorial legislature in 1808, for ten days in June and twenty days in November. The legislature consisted of four men: Governor Lewis, Judge J. B. C. Lucas, Judge Otto Schrader, and Secretary Edward Hempstead. They passed twenty acts in 1808.

Among the most important were those acts for laying out and constructing an all-weather road, capable of handling a four wheeled carriage, going south to Ste. Genevieve, Cape Girardeau, and New Madrid. The current route south of Ste. Genevieve was barely passable by horseback or foot. The only four wheeled vehicle road in St. Louis went north to Camp Bellefontaine. The road to St. Charles was for two wheeled vehicles.

Other acts concerned the incorporation of towns; dower rights of widows; and establishment of corporate bodies. Fiscal acts concerned punishment of insolvent, absent, and abscording debtors; mortgages; recovery of debts; regulating interest on money; penalty for passing counterfeit money; bail; expenses of maintaining a jail; and paying Edward Hempstead for preparing and supervising the printing of the territorial laws.

Lewis issued a proclamation dividing the district of New Madrid in half, establishing the district of Arkansas. He was beginning to outline the boundaries of Missouri, which became a territory in 1812, and the State of Missouri in 1821.656

The Secretary of War had ordered the establishment of two trading forts for the Indians, one on the Mississippi for the Sac and Fox, and the other on the Missouri for the Osage. Both forts were built in 1808. Fort Madison on the Mississippi was under almost constant Indian attacks—attacks instigated by British traders who had dominated the trade of the Upper Mississippi for years.