Meriwether Lewis left St. Louis on September 4th, 1809. His departure had been delayed by treaty making with the Osage Indians. William Clark wrote to his brother Jonathan on August 26th, that he expected Lewis to set out the next day for Philadelphia to “write our book.” The Indians must have shown up unexpectedly. Clark wrote that he was concerned about Lewis—

Govr. L. I may Say is r—d by Some of his Bills being protested for a Considerable Sum, which was for moneys paid for Printing the Laws and expences in Carrying the mandan home all of which he has vouchers for. if they Serve me in this way what___I have Sent on my accounts to the 1st of July with vouchers for all to about $1800 ….

… his Crediters all flocking in near the time of his Setting out distressed him much, which he expressed to me in Such terms as to Cause a Cempothy which is not yet off—I do not believe there was ever an honester man in Louisiana nor one who has purer motives than Govr. Lewis. if his mind had been at ease I should have parted Cherefully. he has given all his landed property into the hands of Judge Steward Mr. Carre & myself to pay his debts. with which we have Settled the most of them at this place. Some yet remains and Some property yet remains—his property in this Country will—pay his—by a Considerable amount, tho’ I think all will be right and he will return with flying Colours to this Country …692

The source of written information about Lewis’s death has to be carefully analyzed. Many false stories and documents were created to support the death by suicide story. False documents for the historic record were a trademark of General Wilkinson, who understood the value of a paper trail. However, cover ups can go both ways. They are sometimes the only evidence linking someone to a crime. In the case of Meriwether Lewis, there are not only historic cover ups, there are also contemporary distortions of the historic record to support the suicide theory. Of necessity, this chapter will be dealing with both historic and contemporary inaccuracies in trying to puzzle out what might have really happened.

On September 11th, Lewis was at New Madrid. He went to the courthouse with John Pernier to make out a will. The will was later recorded at the Albemarle courthouse. Lewis wrote:

I bequeath all my estate real and personal to my Mother Lucy Marks of the County of Albemarle and the State of Virginia after my private debts are paid of which a statement will be found in a small minute book deposited with Pernier my Servant.

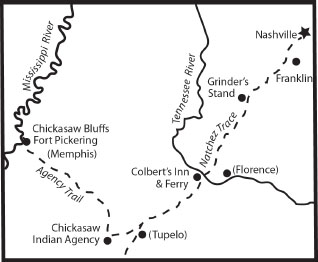

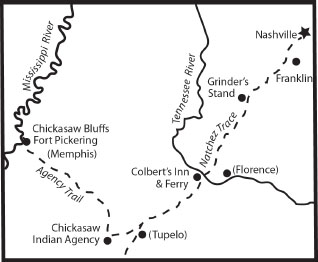

By September 15th, they had arrived at Fort Pickering at Chickasaw Bluffs. Lewis was sick with malarial fevers, and stayed at the fort for two weeks, leaving on September 29th. While he was ill, Lewis was cared for by Captain Gilbert C. Russell, the commander of the fort. Russell wrote two letters to Jefferson reporting on Lewis’s 14 day stay at the fort, and what he knew about the 14 days after Lewis left the fort before his death. Russell’s letters were in the nature of an official report to the president and Lewis’s family and friends. There never was an investigation of his death.

According to a false story—that was told by an unnamed person to Captain Amos Stoddard, who then reported it to Captain James House—Lewis tried to commit suicide several times while he was on the boat. Captain House, the former commander of Camp Belle Fontaine in St. Louis, wrote to Frederick Bates from Nashville on September 28th:

I arrived here two days ago on my way to Maryland—yesterday Maj. Stoddart of the army arrived here from Fort Adams, and informs me that his passage through the indian nation, in the vicinity of Chickasaw Bluffs he saw a person, immediately from the Bluffs, who informed him, that the Governor had arrived there (sometime previous to his leaving it) in a state of mental derangement, that he had made several attempts to put an end to his own existence, which this person had prevented, and that Capt. Russell, the commanding officer at the Bluffs had taken him into his own quarters where he was obliged to keep strict watch over him to prevent his committing violence on himself and has caused his boat to be unloaded and the key to be secured in his stores.693

The most interesting point about this letter is that Captain House doesn’t identify the person who told Major Stoddard he had “several” times prevented Lewis from committing suicide while traveling on the boat between St. Louis and Fort Pickering. This is the first evidence of a conspiracy with “talking points.” It appears that House and Bates were at least on the edges of the conspiracy. Captain House is the first person to use the attempted suicide story. If it was only gossip, House would have identified the person who saved the mentally deranged Lewis from killing himself. Instead, he is laying the paper trail for the suicide story. “Mr. X,” (see note 699, page 508) who told Amos Stoddard about saving Lewis’s life, was undoubtedly traveling in the vicinity of Chickasaw Bluffs to make new arrangements for murdering Lewis on the Natchez Trace—the assassination which happened at Grinder’s Stand on October 11th, 1809.

Captain Gilbert C. Russell wrote two letters to Jefferson, on January 4th and January 31st, 1810. There are also two false documents written in his name, one of which William Clark reported receiving shortly after Lewis’s death, which is lost, and another created during General Wilkinson’s court martial in 1811, known as the “Russell Statement.” Donald Jackson published the “Russell Statement” in his Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition for the first time in 1962. The “Russell Statement” was examined by two handwriting analysts testifying at the Coroner’s Inquest held at Lewis County, Tennessee in 1996. They both concluded that Russell did not write and he did not sign the so called “Russell Statement.” 694

The day after Lewis arrived at Fort Pickering, on September 16th, he wrote a letter to President Madison:

I arrived here yesterday about 2 Ock P. M. very much exhausted from the heat of the climate, but having taken medicine feel much better this morning. My apprehension from the heat of the lower country and my fear of the original papers of the voyage falling into the hands of the British has induced me to change my rout and proceed by land through the state of Tennisee to the city of Washington. I bring with me duplicates of my vouchers for public expenditures &c. which when fully explained, or rather the general view of the circumstances under which they were made I flatter myself that they will receive both sanction & approbation-and sanction.

Provided my health permits no time shall be lost in reaching Washington. My anxiety to pursue and to fulfill the duties in-cedent to the international arrangements incedent to the government of Louisiana has prevented my writing you as more frequently. Mr. Bates is left in charge. Inclosed I herewith transmit you a copy of the laws of the territory of Louisiana. I have the honour to be with the most sincere esteem your Obt. and very humble Obt. and very humble servt. Meriwether Lewis 695

This signed letter appears to have been a draft. A final version of the letter could have accompanied the book of Territorial Laws sent to Madison. This is the only known version, in the collection of the Missouri History Museum. The letter is obviously written in poor health, but its meaning is entirely clear. Suicide theorists view it as evidence of Lewis’s mental instability.

Captain Russell wrote on January 4th, 1810 to Jefferson:

Considering it a duty incumbant upon me to give the friends of the late Meriwether Lewis such information relative to his arrival here, his stay and departure, and also of his pecuniary matters as came within my knowledge which they otherwise might not obtain, and presuming that as you were once his patron, you still remain’d his friend, I beg leave to communicate it to you and thro’ you to his mother and such other of his friends as may be interested.

He came here on the 15th of September last from whence he set off intending to go to Washington by way of New Orleans. His situation rendered it necessary that he should be stoped until he would recover, which I done & in a short time by proper attention a change was perceptible and in about six days he was perfectly restored in every respect & able to travel. Being placed then myself in a similar situation with him by having my Bills protested to a considerable amount I had made application to the General [Wilkinson] & expected leave of absence every day to go to Washington on the same business with Governor Lewis. In consequence of which he waited six or eight days expecting I would go with him, but in this we were disappointed & he set off with a Major Neely who was going to Nashville.

At the request of Governor Lewis I enclosed the land warrant granted to him in consideration of his services to the Pacific Ocean to Bowling Robinson Esq Sec’y of the T’y [Treasury] of Orleans with instructions to dispose of it at any price above two dollars per acre & to lodge the money in the Bank of the United States or any of the branch banks subject to his order.

He left with me two Trunks a case and a bundle which will now remain here subject at any time subject to your order or that of his legal representatives. Enclosed is his memo respecting them but before the Boat in which he directed they might be sent got to this place I rec’d a verbal message from him after he left here to keep them until I should hear from him again. [italics emphasis added].

He set off with two Trunks which contain’d all his papers relative to his expedition to the Pacific Ocean. Gen’l Clark’s Land Warrant, a Port-Folio, pocket Book, and Note Book together with many other papers of both a public & private nature, two horses, two saddles & bridles, a Rifle, gun, pistols, pipe, tomahawk & dirks, all ellegant & perhaps about two hundred and twenty dollars, of which $99.58 was a Treasury Check on the U. S. branch Bank of Orleans endorsed by me. The horses, one saddle, and the check I let him have. Where or what has become of his effects I do not know but presume they must be in the care of Major Neely near Nashville.

As an individual I verry much regret the untimely death of Governor Lewis whose loss will be great to his country & surely felt by his friends….696

Russell’s letter of January 4th is important for several reasons. If Lewis had tried to commit suicide before he got to the fort, Russell would have said so. If he had written a second will at the fort, Russell would have said so. William Clark believed that he received a letter from Russell shortly after Lewis’s death telling him Lewis had made a second will at the fort naming William Meriwether and himself as the executors of the will, and saying that Clark was to take charge of his papers. Clark expected to find this will, and have it sent to him, but it never materialized. The letter Clark received has also never been found. This is one of the tricks of which General Wilkinson was a master. The letter was written in the name of Captain Russell to make certain William Clark believed the suicide story and the story was reinforced with the mention of a new will. The general had played the same kind of tricks twenty years earlier, when he destroyed the reputation of Clark’s older brother, George Rogers Clark in Kentucky politics.697

In Russell’s authentic letter to Jefferson he states that Lewis was fully restored to health in six days time and was waiting at the fort for another 6–8 days hoping Russell would receive permission to go to Washington, so that they could travel together. Russell must have requested a leave of absence from General Wilkinson weeks earlier. It is the only reason Lewis would have delayed his travels.

The other important detail is that Russell said he received a “verbal message” from Lewis to hold Lewis’s trunks and other items at the fort rather than follow the instructions in the memorandum that Lewis had Russell sign. The memo strongly suggests Lewis feared assassination.There are two other possible indications that he was worried—making out his will at New Madrid, and changing his plans to go by boat to New Orleans. Both of those actions could have been just sensible precautions, but the memorandum is a different story—

Fort Pickering, Chickasaw Bluff’s

September 28th 1809

Captain Russell will much oblige his friend Meriwether Lewis by forwarding to the care of William Brown Collector of the port of New Orleans, a Trunk belonging to Capt. James Huse addressed to McDonald and Ridgely Merchants in Baltimore. Mr. Brown will be requested to forward this trunk to its place of destination. Captain R. will also send two trunks a package and a case addressed to Mr. William C. Carr of St. Louis unless otherwise instructed by M. L. by letter from Nashville.

M. Lewis would thank Capt. R. to be particular to whom he confides these trunks &c a Mr. Cabboni [Jeane Pierre Cabanné] of St. Louis may be expected to pass this place in the course of the next month, to him they may be safely confided. [italics emphasis added]

[on reverse side] Sent Capt. Hous’s Trunk by Benjamin Wilkinson on the 29th Sept. 1809. Gov’r Lewis left here on the morning of the 29th Sept. Russell 698

The two trunks are what his assassins wanted to get possession of. This is shown by the so-called “verbal message” from Lewis to hold the trunks at the fort. Will Carr was the federal land agent in St. Louis. The trunk’s contents must have been land records. Lewis tried to protect the contents by leaving the trunks at the fort, and saying they should be sent to him in Nashville, only if he wrote a letter requesting they be sent. It mattered enough for him to leave a written memorandum with Russell.

If he didn’t write a letter, the meaning seems clear—Lewis would no longer be alive and the trunks should be sent back to Will Carr in St. Louis. Russell should be “particular” about who took them to Carr, and they could “safely be confided” in the care of Jean Pierre Cabanné, a wealthy St. Louis merchant. The contents were something Lewis wanted to protect. Russell was only to follow his written instructions, not any verbal message.

Who brought the “verbal message” from Lewis to Captain Russell saying Russell should hold the trunks at the fort? Was it Mr. X, the man Major Stoddard encountered around the Chickasaw Bluffs, who said he had saved Lewis from several attempts at suicide on the boat? Or was it someone else?

The original plan of the conspirators must have been to kill Lewis on the boat and blame it on suicide. Lewis knew by September 16th, the day after his arrival at the Bluffs, that he was going to travel on the Natchez Trace. He probably decided that while he was still on the river. Was he consciously trying to get away from his assassins? How did the conspirators change their-plans in order to assassinate him, and still call it a suicide?

Fort Pickering to Chickasaw Agency to Nashville.

The premise of this book is that General Wilkinson and Smith T planned to have Lewis assassinated. Benjamin Wilkinson, the general’s nephew, was a storekeeper in St. Louis. He traveled on the same boat with Lewis, and was going to Baltimore from New Orleans. He took charge of Captain House’s trunk, the one Lewis had agreed to bring to New Orleans for Captain House. Wilkinson left the fort by boat on September 29th for New Orleans, on the same day after Lewis left for Nashville. Benjamin Wilkinson must have been a conspirator.

Making the simplest assumption, there had to be at least one more member of the conspiracy. Benjamin Wilkinson stayed at the fort watching Lewis, while someone else—probably the unknown man Major Stoddard met in the vicinity of Chickasaw Bluffs, “Mr. X”—left immediately to recruit Indian Agent James Neelly at his Indian agency near Pontotoc; tavern owner and inn keeper Robert Grinder at Grinder’s Stand on the Natchez Trace; and army officer Captain John Brahan in Nashville. All three men play leading roles in the mysterious circumstances surrounding Lewis’s death.

It seems likely Mr. X would have been a trusted friend of General Wilkinson, and that he knew both James Neelly and Captain Brahan. Robert Grinder was just the means of committing the murder. Neelly would have suggested Grinder, if Mr. X didn’t already know him. It was Agent Neelly who told Lewis to go to Grinder’s Stand and wait for him there.699

General Wilkinson was in charge of developing the old Indian Trace into a military and postal service road in 1801–1803. The Natchez Trace was heavily traveled. It was used by boatmen who traveled down to Natchez with the Mississippi River current, and then walked back to Nashville on the Trace. Because travelers had money, robbery was commonplace. Slaves in chains were brought down the Trace to be sold at auction in Natchez. There were slaves working in the adjoining fields. The Chickasaw Indians controlled much of the Trace and had the exclusive right to run a ferry across the Tennessee River, and to operate traveler’s inns (stands) in Chickasaw territory.

The War Department was in charge of Indian Affairs. The Chickasaw Indian agent Neelly would have owed his job to Wilkinson, or would at least have known him. Mr. X was probably an army officer who served with Wilkinson during his tours of duty in the southwest frontier, and knew the country.

The unknown conspirator, “Mr. X,” would have left Fort Pickering as soon as they arrived and gone down the Agency Trail to confer with James Neelly, the newly appointed Indian Agent. Lewis wrote that his boat had arrived at Fort Pickering in the afternoon of September 15th. The distance was about 120 miles from the fort to the agency. “Mr. X” could have reached the Indian agency on the 18th. Neelly could have started to Fort Pickering on September 19th and arrived there late on the 21st. The timeline could be extended by several days. All we know is that the letter which forms the basis of the suicide story says that Neelly arrived at the fort “on or about” the 18th of September.

Agent James Neelly is a key player in both the suicide and the assassination theories. His account of the death of Lewis by suicide has formed the basis of the suicide theory. However, his so-called letter to Jefferson, describing events which he had not-witnessed, was neither written nor signed by him, so all information contained in the letter is part of the cover up.

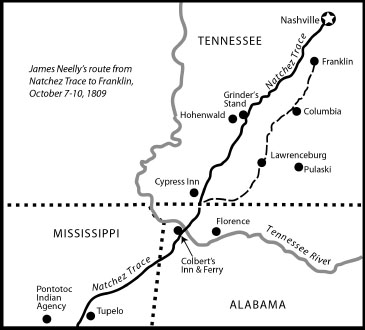

After leaving the Chickasaw Agency, Lewis and Neelly traveled to Cypress Inn on the Natchez Trace, where Neelly took the road to Franklin. Lewis went on to Grinder’s Stand.

When “Mr. X” arrived at Neelly’s Indian Agency at Pontotoc, he found Neelly willing to cooperate, but Neelly had a highly important obligation. Neelly had to appear in court in Franklin, Tennessee on October 11th, where he was being sued for a debt of $103.44. This court appearance had been arranged a year earlier, and if he didn’t appear he would forfeit his bond and face jail as a debtor. Neelly, in fact, did appear in court. So October 11th became a convenient alibi date. If he was ever accused of the murder of Governor Lewis, he had the best of all possible alibis—he was in court on that date.700

It was arranged that Neelly would go to Fort Pickering and volunteer to escort Lewis on the Natchez Trace to Nashville, but Neelly would leave the party after they crossed the Tennessee River and take the alternate shorter route to Franklin. He would tell Lewis to go on ahead and wait for him at Grinder’s Stand, the first traveler’s inn and tavern owned by a white man after leaving Chickasaw territory. Robert Grinder would arrange the murder of Meriwether Lewis, and make it appear a suicide. Agent Neelly would return to his agency at Pontotoc, and Captain John Brahan in Nashville would manage the cover up. Neelly’s job was to travel with Lewis and tell him to go on to Grinder’s Stand alone, saying that he would join him later.

Captain Brahan would write and sign a letter in the name of Neelly to report Lewis’s death by suicide to Thomas Jefferson at Monticello. “Mr. X” would be in the vicinity of Grinder’s Stand to bring the news of the assassination to Brahan at Nashville. The conspiracy had several well planned parts. James Neelly and John Brahan would be far away from the scene of the murder. “Mr. X,” the agent of General Wilkinson and John Smith T, was not connected to it publicly. The general was at Natchez, and Smith T was at St. Louis. Benjamin Wilkinson was on his way down the Mississippi. Only Robert Grinder and his associates were vulnerable, and local residents could be intimidated into silence.

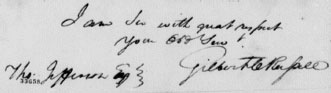

Gilbert C. Russell wrote a second letter to Jefferson describing what he knew of events after Lewis left the fort. This is his signature from his letter of January 31, 1810. What is important about his signature is that he invariably wrote it as one consecutive name. The C stands for Christian and it joins together the names of Gilbert and Russell. That is why his contemporaries often referred to him as “Gilbert C. Russell.” The Russell Statement which General Wilkinson created in 1811 forgot that important detail and his forged signature simply reads “Gilbert Russell.” On January 31st, Captain Russell wrote to Jefferson about James Neelly and the role he played in Lewis’s suicide:

I have lately been informed that James Neely the Agt. to the Chickasaws with whom Gov Lewis set off from this place has detained his pistols & perhaps some other of his effects for some claims he pretends to have on his estate. He can have no more just claim for any thing more than the expenses of his interment unless he makes a charge for packing his two Trunks from the nation. And for that he cannot have the audicity to make a charge after tendering the use of a loose horse or two which he said he had to take from the nation & also the aid of his servant. He seemed happy to have it in his power to serve the Govr & but for making the offer which I accepted I should have employ’d the man who packed the trunks to the Nation to have them taken to Nashville & accompany the Govr. Unfortunately for him this arrangement did not take place, or I hesitate not to say he would this day be living. The fact is that his untimely death may be attributed to the free use of liquor which after he recovered & expressed a firm determination to never drink any more spirits or use snuff again both of which I deprived him of for several days & confined him to claret & a little white wine. But after leaving this place by some means or other his resolution left him & this Agt. being extremely fond of liquor, instead or preventing the Govr from drinking or keeping him under any restraint advised him to it & from everything I can learn gave the man every chance to seek an opportunity to destroy himself. Also from the statement of Grinder’s wife where he killed himself I cannot help to believe that Purney was rather aiding & abeting the murder than otherwise.

This Neely says he lent the Govr money which cannot be so as he had none himself & the Govr had more than one hund. $ in notes & species besides a check which I let him have of 99.58 none of which it is said could be found. I have wrote the Cashier of the branch bank at Orleans as to whom the check was drawn in favor of myself on order to to stop payt. when presented. I have this day authorized a gentlemean to pay the pretended claim of s & take the pistols which will be held sacred to the order of any of the friends of M. Lewis free of encumbrance.

I am Sir with great respect

Your Obt Servt [Obedient Servant]

Gilbert C. Russell

Tho. Jefferson Esq. [Esquire]701

From the letter we learn Captain Russell sent his own man with Lewis to manage the two pack horses carrying Lewis’s trunks with the expedition papers and other items. Neelly insisted that after they arrived at the Pontotoc Agency, he would employ his own servant and use horses taken from the Chickasaw nation to transport Lewis’s trunks to Nashville. Captain Russell blamed Neelly for causing Lewis’s death, saying that Neelly encouraged his drinking, and that it was the cause of Lewis committing suicide.

When they left Fort Pickering on September 29th, the party would have consisted of Lewis and John Pernier, riding on two horses that Russell had provided, Seaman the dog, James Neelly and one man, probably an enlisted army man, from the fort. Russell would have learned about the drinking when his man returned to the fort, and he believed that his man would have prevented Lewis from committing suicide. He also somehow thought Pernier was involved in the suicide.

Russell says Neelly was lying when Neelly said he lent Lewis money. In addition, Neelly wanted Captain Russell to pay him money before he would relinquish Lewis’s two pistols and other possessions. Neelly told Russell Lewis had no money, so the more than $100 Lewis was carrying had disappeared. Russell stopped payment on the endorsed check for $99.58 he had given Lewis. Russell was going to pay Neelly the money so that he could get back Lewis’s pistols. However, that didn’t happen.

In December, 1811, Lewis’s stepbrother John Marks went to Tennessee to retrieve Lewis’s two pistols, rifle, horse, dirk [a small sharp weapon] and watch from Neelly. He wrote to his stepbrother Reuben Lewis, that he visited Neelly’s farm at the Duck River (near Franklin) and had gotten Lewis’s rifle and horse from Mrs. Neelly. Neelly was living at the Chickasaw Agency and Marks was “informed that Nealy carries the dirk and pistols constantly with him.” Neelly had Lewis’s gold watch as well as his pistols.702

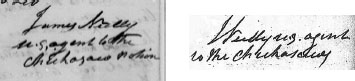

Suicide theorists depend on Neelly’s letter reporting Lewis’s death to Thomas Jefferson. Thomas Danisi acknowledges the Neelly letter was written by John Brahan at Nashville, as Brahan wrote an almost identical letter to Jefferson signed by himself. Both letters are dated October 18, 1809 and were delivered to Jefferson by Pernier.702 When he signed for Neelly, Brahan didn’t get Neelly’s signature block correct. Neelly always signed “J Neelly, u.s. agent” with the J and N joined together on one line and on the second line, “to the Chickasaws.” Brahan made it a three line signature block, used Neelly’s first name, “James” and put “u.s. agent to the” on the second line and “Chickasaw Nation” on the third line. The signature on the right is from the real letter that James Neelly wrote on the same day, October 18, 1809 to Secretary of War Eustis from the Chickasaw Agency near Pontotoc.703

Neelly wrote to Eustis on October 18th requesting reimbursement for the $90 he had given to Jeremiah K. Love for transporting a prisoner from the Indian agency to jail at Nashville. $90 was a month’s salary for Neelly. The prisoner, George Lanehart had stolen two saddlebags containing $621 silver dollars belonging to Joseph Van Meter, a guest at James Colbert’s Inn at Pontotoc. The saddlebags of money were in the safekeeping of Colbert. The theft occurred on September 20th, 1809.

The theft happened while Neelly was at Fort Pickering, but he would have been quickly informed about it, because it was a major crime committed in Chickasaw territory. It was a very large sum of money, and Colonel Van Meter was a personal friend and neighbor of President James Madison. It almost certainly had to do with the public lands sale of former Chickasaw territory at the Great Bend of the Tennessee River (near today’s Huntsville, Alabama). Investors were swarming in from all over the country, to purchase the prime land for growing cotton.

When Neelly and Lewis arrived at the Chickasaw Agency, Neelly took extreme measures in dealing with the crisis. It was vital to restore public confidence in the Colbert family, the half Scotch-half Chickasaw family, which ran the Chickasaw Nation for many years.

On October 3rd, Neelly assembled eight leading men of the area to sign a statement with him that announced:

James Colbert, at whose house the money was lost … has always conducted himself, and has been reputed an honest man, and we conceive no blame is, or ought to be attached to the character of Colbert or his family—let malicious characters report what they may.

This statement was published in the same issue of the Nashville Democratic-Clarion newspaper which reported the death of Governor Lewis on October 20th. Neelly at the bottom of the paid announcement, added the statement: “the printers at Natchez and New Orleans will insert this and forward their accounts to me.” Publication in the three leading newspapers of the south shows how important the matter was to Neelly. The fact that he waited at the fort to escort Lewis rather than returning to the agency to take care of it sooner demonstrates his determination to be Lewis’s escort.

Sept. 15: Lewis arrives at Fort Pickering.

September 20: Saddlebags of Colonel Joseph Van Meter of Virginia are stolen at James Colbert’s Inn at the Tennessee River containing $621 silver dollars.

September 29: Lewis and Neelly leave Fort Pickering.

October 3: Neelly assembles local leaders at the Chickasaw Agency to endorse honest reputation of the Colbert family.

October 11: Lewis dies at Grinder’s Stand.

October 11: Neelly appears in court at Franklin.

October 18: John Brahan at Nashville writes two letters to Jefferson—one in his name, and the other in the name of James Neelly—reporting the death of Lewis by suicide.

October 18: Neelly at the Chickasaw Agency at Pontotoc writes to Eustis requesting $90 reimbursement for paying Jeremiah K. Love to deliver the prisoner to Nashville. Delivering the prisoner would have been Neelly’s duty.

October 20: The Nashville Democratic Clarion publishes an article on the death of Governor Lewis by suicide, and the paid public announcement by Neelly.

November 30: George Laneheart is convicted of stealing Colonel Van Meter’s saddlebags and money and is sentenced to two months in the debtors room of the jail in Nashville.704

When Neelly, Lewis, Pernier, Neelly’s servant, and Seaman left the agency, they crossed the Tennessee River on George Colbert’s Ferry. They would have stayed at Chief Tuscomby’s Stand, sixteen miles from the river, near the junction of the trail to Lawrenceburg. The stand later became known as Cypress Inn.705

This is where the so-called letter from Neelly to Jefferson claimed that at “one day’s journey” from the river they lost two of their horses, and Neelly stayed behind to look for them, telling Lewis to go on ahead and wait for him at the first house inhabited by white people, Robert Grinder’s Stand.

Lewis, Pernier, Neelly’s servant and Seaman traveled on the Natchez Trace, and Neelly went to Lawrenceburg and from there he went north to Franklin. Neelly owned a large farm outside of Franklin. On October 10th, Lewis and his party reached Grinder’s stand, which was just off the Natchez Trace. It was a two room cabin, with one room reserved for travelers. Robert Grinder supposedly was absent from the stand. His wife Priscilla was there. Their household consisted of three children, two slaves and a cook. The stand had a bad reputation because Grinder sold whiskey to the Indians.706

Mrs. Grinder stories play an important role in the account of Lewis’s death by suicide. The first account is found in the so called Neelly letter to Jefferson written by John Brahan in Nashville. It is entirely crafted by the conspirators to support the suicide story.

There are two more Mrs. Grinder stories. The second story she told to Lewis’s friend, Alexander Wilson, on May 10th, 1810. Wilson was the ornithologist from Philadelphia who was going to provide bird illustrations for Lewis’s books. Wilson was traveling on the Natchez Trace in search of more birds.

The third story Mrs. Grinder told to a schoolteacher who taught in the Cherokee nation, first printed in the North Arkansas newspaper, and then reprinted in the New York Dispatch newspaper in 1845. Robert Grinder died in 1827, so the third Mrs. Grinder story may be more truthful.

Mrs. Grinder’s husband is the prime suspect in the murder of Meriwether Lewis, and all of her stories may be considered cover ups, while perhaps containing some elements of truth. Many people have puzzled over these stories. The first story was supposedly told to Brahan by Neelly, who wasn’t present at Grinder’s Stand at the time of Lewis’s death, and who, in fact, wasn’t present at Nashville to tell Brahan the story of what Mrs. Grinder says happened. It might have been the mysterious “Mr. X” who was near the Stand at the time of Lewis’s death, saw him buried, and then went to Nashville to meet Brahan where they concocted the letters to Jefferson. In any event, this is the version that has come down in history. My earlier book, The Death of Meriwether Lewis: A Historic Crime Scene Investigation, contains all three versions of the story, and many other documents.

Any lawyer looking at this account would declare it inadmissible as evidence. The Neelly/Brahan letter says:

… he reached the house of a Mr. Grinder about sunset, the man of the house being from home, and no person there but a woman who discovering the governor to be deranged gave him up the house & slept herself in one near it. His servant and mine slept in the stable loft some distance from the other houses. The woman reports that about three o’clock she heard two pistols fire off in the Governors Room; the servants being awakined by her, came in too late to save him. He had shot himself in the head with one pistol & a little below the breast with another. when his servant came in he says: I have done the business my good servant give me some water. He gave him some water, he survived but a short time, I came up some time after, & had him as decently Buried as I could in that place. if there is anything wished by his friends to be done to his grave I will attend to their Instructions.707

The Alexander Wilson account says:

I took down from Mrs. Grinder the particulars of that melancholy event, which affected me extremely. This house or cabin is seventy-two miles from Nashville, and is the last white man’s as you enter Indian country. Governor Lewis, she said, came hither about sunset, alone, and inquired if he could stay for the night; and alighting brought the saddle into the house. He was dressed in a loose gown, white striped with blue. On being asked if he came alone, he replied there were two servants behind, who would soon be up. He called for some spirits and drank very little. When the servants arrived one of whom was a negro, he inquired for his powder, saying he was sure he had some powder in a cannister. The servant gave no distinct reply, and Lewis, in the meanwhile, walked backwards and forwards before the door talking to himself. Sometimes, she said, he would seem as if he were walking up to her; and would suddenly wheel round, and walk back as fast as he could. Supper being ready he sat down, but had eaten only a few mouthfuls when he started up, speaking to himself in a violent manner. At these times, she says, she observed his face to flush as if it had come on him in a fit. He lighted his pipe, and drawing a chair to the door sat down, saying to Mrs. Grinder, in a kind tone of voice, “Madame this is a very pleasant evening.” He smoked for some time, but quitted his seat and traversed the yard as before. He again sat down to his pipe, seemed again composed, and casting his eyes wistfully towards the west, observed what a sweet evening it was. Mrs. Grinder was preparing a bed for him; but he said he would sleep on the floor, at dusk, the woman went off to the kitchen, and the two men to the barn, which stands about two hundred yards off. The kitchen is only a few paces from the room where Lewis was, and the woman being considerably alarmed by the behaviour of her guest could not sleep, but listened to him walking backwards and forwards, she thinks, for several hours, and talking aloud, as she said, “like a lawyer.” She then heard him at her door calling out “Oh madam! Give me some water, and heal my wounds.” The logs being open, and unplastered, she saw him stagger back and fall against a stump that stands between the kitchen and room. He crawled for some distance, and raised himself by the side of a tree, where he sat about a minute. He once more got to the room; afterwards he came to the kitchen-door, but did not speak; she then heard him scraping the bucket with a gourd for water; but it soon appeared that this cooling element was denied the dying man! As soon as the day broke and not before—the terror of the woman having permitted him to remain for two hours in this most deplorable situation—she sent two of her children to the barn, her husband not being home, to bring the servants; and on going in they found him lying on the bed; he uncovered his side, and showed them where the bullet had entered; a piece of the forehead had blown off, and had exposed the brains, without having bled much. He begged they would take his rifle and blow out his brains, and he would give them all the money he had in his trunk. He often said, “I am no coward; but I am so strong, so hard to die.” He begged the servant not to be afraid of him, for that he would not hurt him. He expired in about two hours, or just as the sun rose above the trees. He lies buried close by the common path, with a few loose rails thrown over his grave. I gave Grinder money to put a post fence round it to shelter it from the hogs, and from the wolves; and he gave me his written promise he would do it. I left this place in a very melancholy mood, which was not much allayed by the prospect of the gloomy and savage wilderness which I was just entering alone…. 708

The 1845 account by the schoolteacher says:

The writer says the remains of Captain Lewis are “deposited in the southwest corner of Maury county, Tennessee, near Grinder’s old stand, on the Natchez trace where Lawrence, Maury, and Hickman counties corner together.” He visited the grave in 1838, found it almost concealed by brambles, without a stone or monument of any kind, and several miles from any house. An old tavern stand, known as Grinder’s, once stood near by, but was long since burned. The writer gave the following narrative of the incidents attending the death of Capt. Lewis, as he received them from Mrs. Grinder, the landlady of the house where he died in so savage a manner. She said that Mr. Lewis was on his way to the city of Washington, accompanied by a Mr. Pyrna and a servant belonging to a Mr. Neely. One evening, a little before sundown, Mr. Lewis called at her house and asked for lodgings. Mr. Grinder not being at home, she hesitated to take him in. Mr. Lewis informed her two other men would be along presently, who also wished to spend the night at her house, and as they were all civil men, he did not think there would be any impropriety in her giving them accommodations for the night. Mr. Lewis dismounted, fastened his horses, took a seat by the side of the house, and appeared quite sociable. In a few minutes Mr. Pyrna and the servants rode up, and seeing Mr. Lewis, they also dismounted and put up their horses. About dark two or three other men rode up and called for lodging. Mr. Lewis immediately drew a brace of pistols, stepped towards them and challenged them to fight a duel. They not liking this salutation, rode on to the next house, five miles. This alarmed Mrs. Grinder. Supper, however, was ready in a few minutes. Mr. Lewis ate but little. He would stop eating, and sit as if in a deep study, and several times exclaimed, “If they do prove any thing on me, they will have to do it by letter.” Supper being over, and Mrs. Grinder seeing that Mr. Lewis was mentally deranged, requested Mr. Pyrna to get his pistols from him. Mr. P. replied, “He has no ammunition, and if he does any mischief it will be to himself, and not to you or any body else.” In a short time all retired to bed; the travellers in one room as Mrs. G. thought, and she and her children in another. Two or three hours before day, Mrs. G. was alarmed by the report of a pistol, and quickly after two other reports, in the room where the travellers were. At the report of the third, she heard some one fall and exclaim, “O Lord! Congress relieve me!” In a few minutes she heard some person at the door of the room where she lay. She inquired,, “Who is there?” Mr. Lewis spoke and said, “Dear Madam, be so good as to give me a little water.” Being afraid to open the door, she did not give him any. Presently she heard him fall, and soon after, looking through a crack in the wall, she saw him scrambling across the road on his hands and knees.

After daylight Mr. Pyrna and the servant made their appearance, and it appeared they had not slept in the house, but in the stable. Mr. P. had on the clothes Mr. L. wore when they came to Mrs. Grinder’s the evening before, and Mr. L.’s gold watch in his pocket. Mrs. G. asked what he was doing with Mr. L.’s clothes on; Mr. P. replied “He gave them to me.” Mr. P. and the servant then searched for Mr. L., found him and brought him to the house, and though he had on a full suit of clothes, they were old and tattered, and not the same as he had on the evening before, and though Mr. P. had said that Lewis had no ammunition, Mrs. G. found several balls and a considerable quantity of powder scattered over the floor of the room occupied by Lewis; also a canister with several pounds in it. 709

My own preference is to believe some of the third account. It seems probable that three men rode up to the stand and that Lewis drove them off with his pistols. On the assumption that Lewis’s assassins wanted to prevent him from bringing incrimating documents to Washington, they would have offered him an opportunity to save himself by surrendering the documents, but he refused to deal with them.

It seems probable that Pernier switched clothes with Lewis and was going to ride off as a decoy at sunrise. Mrs. Grinder blamed Pernier for the gold watch that Neelly took when he arrived. Pernier was made to appear a suspect, with robbery as a motive. It seems likely Lewis was dressed in old and tattered clothes when he was found on the road. It seems likely Pernier, “Mr. P.,” appeared like a white person to her, and the negro accompanying Lewis was Neelly’s slave.

A local account may be found on the Tennessee Geneaology website about the burial of Lewis and a coroner’s inquest that was held in 1809. Robert Smith was a postal employee, who discovered Lewis’s body on the road in the early morning of October 11th. Since Lewis was a very big man, they made his coffin from a huge chestnut oak, and forged large square iron nails to close it.710

It was those nails that established the identity of Lewis’s remains when his burial site at Grinder’s Stand was developed into a Tennessee State Monument in 1850. The Tennessee State Monument Committee had a medical doctor on its commission. When they identified Lewis’s remains, they declared:

The impression has long prevailed that under the influence of disease of body and mind—of hopes based upon long and valuable services—not merely deferred but wholly disappointed—Governor Lewis perished by his own hands. It seems to be more probable that he died at the hands of an assassin.711

Local residents believed that Robert Grinder and his accomplices killed Lewis. There was a coroner’s inquest, and the record was kept in a docket book by the jury foreman, Samuel Whiteside. The docket book was known to exist in the early 1900’s, but has since vanished. It was said that all six members of the coroner’s jury believed Grinder was guilty but were afraid to convict him. It was said Thomas Runnions was an accomplice in the murder, and that his mocassin imprint was seen around the murder scene, which took place near the stables.712

There is also the question of the bloodstained Masonic Apron known to have belonged to Meriwether Lewis, which remains a mystery. Why didn’t Lewis receive a proper Masonic burial at the time of his death? The gravesite is still located on the property that once was Grinder’s Stand, and is now a National Park Service site. Two hundred years later, in 2009, his National Monument & Gravesite was the scene of a public and Masonic ceremony honoring Lewis, attended by over 2,000 people.713

Historian Jay Buckley points out the similarity of the Freemason story of Hiram Abiff, builder of Solomon’s temple and a widow’s son, who was killed by three men for refusing to reveal masonic secrets. Like Hiram Abiff, Lewis was buried in a shallow grave, and later reburied with a broken shaft monument.714

Meriwether Lewis Gravesite at National Monument, Hohenwald, Tennessee.

Grinder’s Stand replica cabin at Meriwether Lewis National Monument & Gravesite.

Lewis’s bloodstained Masonic Apron is on display at the Masonic Lodge in Helena, Montana. (Photos by Rick Blond)

Why was his body buried in a primitive inn and tavern yard, without even a fence to guard it from the pigs and wolves? Why weren’t his remains returned to the family graveyard in Charlottesville? Why was Alexander Wilson the only one of his friends and family to visit his gravesite? Why didn’t Jefferson investigate the death of his friend? The answer has to be that if his remains were moved, or his death was investigated, it would become obvious he was assassinated. Suicides didn’t have to be investigated. An assassination couldn’t be proven, and nothing was going to bring Lewis back. There were powerful people behind Lewis’s assassination, and the deed was done. Jefferson kept silent.

What happened to Seaman? It is more likely that Seaman was shot and died defending Lewis, rather than the story he died of grief at his gravesite. What happened to Pernier, who witnessed what really happened that night?

Did James Neelly witness Lewis’s burial? It was a day and half’s travel from Franklin to Grinder’s Stand. He might have been there, but it is likely he arrived soon after the burial. “Mr. X” would have conferred with Neelly at Grinder’s Stand, and then gone north with Pernier to Nashville, bringing Lewis’s possessions with them.

“Mr. X” and Captain John Brahan composed the letters to Jefferson. It would have made a much better cover up if Brahan hadn’t sent his own letter to Jefferson, duplicating the content of the so-called Neelly letter. There was no need for it. It was an odd admission that he had actually written the Neelly letter. Crimes get revealed by subsequent cover ups. The letters to Jefferson were dated October 18, 1809, one week after Lewis’s death. The news story and Neelly’s paid announcement defending the reputation of the Colbert family were published in the Nashville newspaper on October 20th.

On November 23rd, 1809, Lewis’s possessions, inventoried and neatly bundled, were to be “safely conveyed to Washington City” by Thomas Freeman. They were received by Isaac Coles, who had replaced Lewis as private secretary to both Jefferson and Madison. Isaac Coles wrote on January 10, 1810:

The bundles of Papers referred to in the above memorandum were so badly assorted that no idea could be given them by any terms of general description. Many of the bundles containing at once Papers of a public nature—Papers intirely private, some important & some otherwise, with accts. Receipts, &c. They were all carefully looked over and put in separate bundles.

Coles attempted to reassemble the jumbled materials to match the descriptions of the list, and he and William Clark noted on the list the persons or departments receiving the materials. W. C. means William Clark.

One small bundle of Letters & Vouchers of consequence (Depts.)

One Plan & View of Fort Madison (Dept. War)

Two books of Laws of Upper Louisiana (Dept. War)

One Book an Estimate of the western Indians (W. C.)

One small package containing the last will & testament of Govr.

Lewis Deceas’d & one check on the Bank of New Orleans for 99 58/100 dollars (T. Jefferson)

One memorandum book (Th. Jefferson)

A transcript of Records &c. (President)

Nine Memorandum Books (W. C.)

Sixteen notebooks bound in red morocco with clasps (W. C.)

One bundle of Miscelans. paprs. (Th. Jefferson)

No 2 Returns of Militia—papers not acted on (War Dept.)

One bundle papers indorsed—“From the Drawer of my Poligt. [Lewis’s own polygraph duplicate writing instrument](Th. Jefferson)

One do. [do. means ditto, in this case, “bundle”] papers relative to the Mines (P. U. S. [President of the U. S.]

One do. Public Vouchers (War Dept.)

Six notebooks unbound (W. C.)

One bundle of Indorsed Letters &c. (Th. J.)

One do. of McFarlane’s acct. for the outfit of Salt Petre expend. (War Dept.)

One journal of do. (War Dept.)

One bundle of Maps &c (W. C.)

One do. “Ideas on the Western expedition” (W. C.)

One bundle of Musterrolls (War Dept.)

One do. Vouchers for expenditures in the War Departmt.

One do. Vocabulary (W. C.)

One do. Maps & Charts (W. C.)

One bundle of papers marked A (Th. Jefferson)

One Sketch of the River St. Francis with a small Letter Book (W. C.)

One do. Containg. Commisn. and Diploma (Th. Jefferson)

One. do. Sketches for the President of the U. States (P. U. S.)

Thomas Freeman was in charge of taking Lewis’s trunks to Washington. The inventory list was signed by Freeman, Captain Boote and Captain Brahan of the U. S. Army, and William P. Anderson of Nashville on November 23, 1809.715

Thomas Freeman was employed by General Wilkinson to build Fort Adams in 1799, after Andrew Ellicott fired him for being an “idle, lying, troublesome, discontented, michief-making man” while making the southwest boundary survey in 1798. Freeman was then employed by Wilkinson to explore the Red River in 1806.

In 1809, he was the Deputy U. S. Surveyor in charge of surveying the public lands of former Chickasaw territory that were being offered for sale at the Great Bend of the Tennessee River. Freeman was acting as a land speculator as well as a surveyor. Freeman was the single biggest purchaser of land, acquiring almost 8,500 acres of land for $18,000 in Madison County, where Huntsville, Alabama was established in 1809. Freeman lived in Nashville. His friend Captain John Brahan was the leader of a group of influential Nashville residents who benefitted from insider knowledge in purchasing the land. Freeman was obviously acting as a purchaser for anonymous buyers. 716

John Brahan had received a federal appointment as the Receiver of Public Money for the land sales. Six weeks of public auctions were held in Nashville to discourage purchases by the squatters who were living on the land and farming it. After the auctions in the summer and fall of 1809, private sales continued. Captain Brahan resigned from the army in January, 1810 and married the daughter of Tennessee Congressman Robert Weakley in June.

Brahan was among the Huntsville elite who became as “rich as princes” from the sale and development of the cotton lands in northern Alabama. While acting as Receiver of Public Money at the Huntsville land office in 1817–19, Brahan used federal money to speculate in land. He purchased 44,647 acres for $318,579, intending to repay the money from reselling the land. However, he came up $80,000 short. Brahan was also a director of the Huntsville Planters and Merchants Bank. He was dismissed from his federal position, and resigned as bank director in 1819.717

The men who assumed responsibility for notifying Jefferson of Lewis’s death, and taking his possessions to Washington were both deeply involved as speculators and as federal officials in the great land sales going on in the fall of 1809. The fact that Lewis’s possessions arrived in Washington in a completely disorganized condition, meant that someone went through the papers looking for material they wanted removed. Someone also wanted Lewis’s two trunks held at Fort Pickering rather than being sent back to Will Carr in St. Louis. Did they find what they were looking for? We don’t know. In any event, Lewis was no longer alive to disclose any information they wanted to keep hidden.

John Smith T went to Washington in the winter, and delivered his petition to Congress, asking for the removal of Judge Lucas from office and requesting second stage status in territorial government. Congress reappointed Lucas, and deferred action on the territorial status of Louisiana.

John Pernier brought the two letters written by Brahan to former president Jefferson at Monticello. First Pernier had gone to Lewis’s mother, who believed Pernier was somehow responsible for Lewis’s death. Undoubtedly, he was extremely nervous, and unwilling to tell her what he knew. It is my opinion that Pernier told Jefferson what really happened at Grinder’s Stand. John Pernier had worked for Jefferson at the President’s House in 1804–05. We don’t know—but it seems likely Jefferson knew from this time on that it was an assassination, and chose to go with the suicide story.

Pernier had arrived at Monticello by November 26th, as Jefferson wrote to Madison on that date about receiving Brahan’s letters concerning Lewis’s goods. Jefferson suggested that Isaac Coles distribute them to the proper recipients. He informed Madison that Pernier was due $240 in wages from Lewis, and he was penniless. Jefferson told Madison he had advised Pernier to sell Captain Russell’s horse that he had ridden from Tennessee and apply it to his back pay. He gave Pernier $10 towards his expenses and Pernier brought Jefferson’s letter to Madison.718

On November 30th, Jefferson rode over to Colonel James Monroe’s house in Charlottesville to talk over matters with him. He wrote to Madison:

I had an hour or two’s frank conversation with him. the catastrophe of poor Lewis served to lead us to the point intended.

Jefferson wanted James Monroe to become the Governor of Louisiana Territory. Monroe wanted a place in Madison’s cabinet, not the governorship. Monroe said in regards to a military appointment, that he would “sooner be shot than take a command under Wilkinson.” James Monroe replaced Robert Smith as Secretary of State in April, 1811, and then became the next President of the United States in 1817–25.719

Jefferson wrote to Madison using the words, “the catastrophe of poor Lewis,” instead of using “suicide,” or “death.” Catastrophe means disaster, havoc, ruin, sudden damage, a momentous tragedy—a very good description of Lewis’s situation and the circumstances of his death as he traveled towards Washington to right the wrongs inflicted on him.

William Clark visited Jefferson on the 7th of December. He wrote in his journal:

Soon after I got to Charlotsville saw Mr. Thos. Jefferson. He invited me to go and Stay at his house, &c. I went with him and remained all night, spoke much of the af [fair]s of Gov. Lewis &c. &c. &c.

On December 13th he met with William Meriwether to express concerns about the legality of Lewis’s will, as Clark was still under the illusion a second will had been written at the fort naming him and William Meriwether the executors of the estate.

This second will was never found; it was undoubtedly a falsehood create by General Wilkinson to deceive Clark about how Lewis died. Supposedly the letter was written by Captain Russell to Clark, but if Lewis had made a second will at the fort, Russell would have been a witness, and he would have informed Jefferson about it. In any event, matters were arranged so that Clark took charge of the expedition materials and John Marks became the executor of the estate.

Clark met with Secretary of War Eustis on December 17th:

… went to see the Secretary of War, had a long talk abt. Gov. Lewis, pointed out his intertentions & views for his protests, [Eustis] Declaired the Govr. had not lost the Confidence of the Govt.720

James Neelly lost his job as Chickasaw Indian Agent in 1812. Tony Turnbow, the Franklin, Tennessee lawyer who discovered Neelly’s appearance in court on October 11th, writes:

Neelly was relieved of his duties in 1812 for questions about his own loyalty or for failing to encourage the Chickasaws to properly support the American government at a time of impending war. After losing the support of the Chickasaws, Neelly was charged with attacking a man in the Chickasaw Nation, frequently becoming intoxicated and indecently exposing himself to the Chickasaws, becoming intimate with a woman other than his wife at the Agency, and self-dealing on land transactions with the Chickasaws.

Neelly never gave back Lewis’s set of pistols, his dirk, and his gold watch. It must have been a constant reminder to all who knew him of his association with Lewis’s death.721

In 1814, Robert Grinder paid $250 for a farm of 100 acres on the Duck River and left the Natchez Trace.722

On February 10, 1810 John Pernier wrote to Jefferson, signing a letter written in another hand. He explained that he was in Washington City in a “distressed situation,” and he had been employed by Lewis without receiving very much pay. He enclosed an account showing he was owed a balance of $271.50 from Lewis’s estate, after deducting the $43.50 he had received from the sale of the horse. He said that if he didn’t receive the money he would be imprisoned for debt.

Pernier was living with John Christopher Sueverman, an old, blind, and very poor former servant of Jefferson who had served in the President’s House. Sueverman was “wholly or partly of Negro ancestry” according to Donald Jackson. The next letter concerning Pernier was written on May 5th, 1810 by someone who wrote the letter for the blind Sueverman, who signed it with a crude signature. It announced:

Respectfully I wish to inform you of the Unhappy exit of Mr. Pirny. He boarded, and lodged, with us ever since his return from the Western Country. The principal part of the time he has been confined by Sickness. I believe ariseing from uneasyness of mind, not having recd. anything for his late services to Govr. Lewis. He was wretchedly poor and destitute…. Last week the poor man appeared considerably better, I believe in some respects contrary to his wishes, for unfortunately on Saturday last he procured himself a quantity of Laudenam. On Sunday morning [April 29th] under the pretence of not being so well went upstairs to lay on the bed, in which situation he was found dead, with the bottle by his Side that had contained Laudanam.723

John Pernier had no money, and was facing debtor’s prison, and he met someone who gave him a bottle of laudanum. Laudanum is a tincture of opium, a narcotic. It was a widely used medicine until early in the 20th century. The laudanum could have easily been laced with arsenic.

General Wilkinson had arrived in Washington in April to begin to prepare his defense for congressional investigations into his conduct.724 In the list of suspicious deaths associated with General Wilkinson, John Pernier’s name should be added.

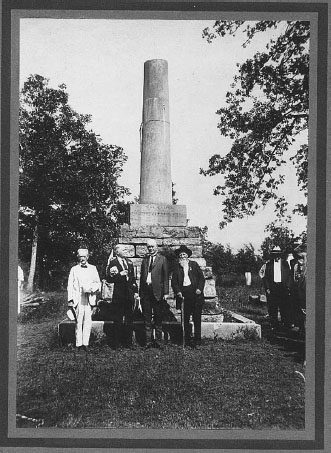

On August 18th, 1925 the Meriwether Lewis National Monument & Gravesite was dedicated at Hohenwald, Tennessee. A crowd estimated at between 7,000–10,000 attended the event. Shown here are P. E. Cox, State Archeologist, John Trotwood Moore, State Historian, Governor Austin Peay and Dr. J. N. Block. The petition to President Calvin Coolidge, requesting that it be designated a national monument, stated:

Investigations have satisfied the public that he was murdered presumably for the purpose of robbery.725

(Tennessee State Library and Archives)