General Wilkinson had an alibi. He published a warrant for his own arrest in his book, Burr’s Conspiracy Exposed and General Wilkinson Vindicated Against the Slander of His Enemies. The warrant was issued on October 9th, 1809 in Natchez, Mississippi, two days before Lewis’s death.

Wilkinson was being sued by John Adair, the former Senator from Kentucky, on charges of trespass, assault and battery, and false imprisonment, for $20,000 in damages. John Adair was one of the Burr conspirators whom Wilkinson had arrested in New Orleans in January, 1807. Wilkinson showed that he posted bail of $7,000 on October 25th, 1809. It is doubtful the general spent any time in a jail cell in Natchez, but the court records are missing. The only evidence this happened is found in footnotes in his own book, published in 1811.

Where he actually was at this time remains a mystery. There is a letter written by him dated September 25, 1809 in New Orleans, and there is a letter written by him dated November 15, 1809 in Natchez.726 Since he was courting a young woman, Celestine Trudeau, the cousin of William Claiborne’s wife, it is safe to assume he stayed in New Orleans as long as possible.

In 1809, there were two competing conspiracies to participate in the first Mexican Revolution, which was being organized by a Catholic priest, Father Manuel Hildago. The date of the first Mexican War for Independence is September 16, 1810, which is still celebrated in Mexico on September 16th every year as El Grito Dolores, or the “Cry of Dolores.” Father Hildago was a priest in the town of Dolores at the center of the silver mine district in the Sierre Madre Mountains.

Apparently—for those who had been conspiring to invade Mexico for many years—there was advance knowledge of Hildago’s plan to start a revolution. Both Aaron Burr and James Wilkinson were preparing for action and organizing separate invasion plans in 1809. Wilkinson, as usual, was doing several things at once. He was defending New Orleans; sending out his own reconnaissance mission to Mexico; and organizing the assassination of Meriwether Lewis. Burr was over in Europe trying to persuade the British government/Napoleon/a group of international associates to support his invasion plans.

In December, 1808, Jefferson ordered 2,000 American troops to New Orleans to defend the city against a potential British invasion. After making diplomatic visits to Cuba and Spanish Florida, General Wilkinson arrived at New Orleans in April, 1809 to take charge. He found the new recruits in deplorable condition. His enemies in New Orleans—Aaron Burr’s allies—the Mexican Association, did their best to ridicule Wilkinson, calling him “his Serene Highness,” and the “the Grand Pensioner de Godoy.” Manuel Godoy was the former prime minister of Spain.

Napoleon had overthrown King Ferdinand VII in 1808 and placed his brother, Joseph Bonaparte, on the throne of Spain. The Pennisular War between the French empire and a coalition of British regular forces and Spanish and Portuguese guerilla fighters started in 1808. The Spanish War for Independence lasted from 1808–1814 on the Iberian Pennisula. With a French king on the Spanish throne, the desire for independence on both the Spanish mainland and its far flung colonial empire rapidly gained strength. In 1809–1811 there were revolutions in Bolivia, Ecuador, Argentina, Columbia, Chile, Paraguay, Uruguay, and Mexico, as various factions fought to either restore the rule of King Ferdinand or to achieve some form of democratic rule.

In 1809, the Spanish colony of Cuba, fearing a revolution, expelled the French speaking Ste. Domingue refugees who had fled to Cuba during the Haitian revolution to start new lives under Spanish rule. More than 10,000 Ste. Domingue refugees arrived in New Orleans from May through December of 1809, doubling the size of the population of New Orleans. Another 7,000 refugees would arrive in 1810. They were a mix of whites, free persons of color, and slaves.727

It severely strained the resources of the area. The 2,000 American troops stationed there were already living and dying in miserable conditions in the city of New Orleans. General Wilkinson arranged for the removal of the troops to farm land east of the city, Terre aux Boeufs, or “Land of the Cattle.” It was the land where beef was raised for the city and vegetable crops were grown. It was also the site where the great Battle of New Orleans was fought in January, 1815, the Chalmette Battlefield of Saint Bernard Parish. As evident from its later fame in defending the city from British attack, Wilkinson had chosen the single best location for his troops.

However, on April 30th—less than two months after assuming his new office—Secretary of War William Eustis ordered the removal of troops from the unhealthy climate of New Orleans to high ground near the vicinity of Natchez, Mississippi, some 300 miles up river. Since General Wilkinson’s orders from the previous Secretary of War, Henry Dearborn, had been to defend New Orleans, Wilkinson chose to disregard Eustis’s orders. The troops arrived at Terre aux Boeufs on June 10th. They would leave the camp on September 14th.

William Claiborne, the territorial governor of New Orleans, wrote to his superior, Secretary of State Robert Smith on July 29th, defending Wilkinson’s choice of Terre aux Boeufs:

You will have heard no doubt, many rumours of the dreadful mortality among the Troops of the U. States stationed in this vicinity. But you may be assured, they are greatly exagerated.—This climate is, in truth, unfavorable to strangers, and it could not be expected, that the troops would have been exempted from the diseases common to the Country.—The number of deaths have not been considerable, and the sick List not unusually numerous.—I was a few days since at the Camp on a visit to General Wilkinson;—I found it in excellent order and every possible exertion appeared to have been used to render the men comfortable.—The position is an eligible one; it is situated about 12 miles below New Orleans and is represented by several of the old Inhabitants to be as healthy as any point on the Mississippi…. I have understood that an order has been issued for the immediate removal of the Troops by water from hence to Natchez or Fort Adams.—

I regret the circumstance, because a voyage up river, at this time of year, will be hazardous to the health of the men, and because I consider the presence of a respectable detachment of Troops near to New Orleans as being at this period absolutely necessary.728

Why did Governor Claiborne write, “I consider the presence of a respectable detachment of Troops near to New Orleans as being at this period absolutely necessary,” in the summer of 1809? A new crisis involving Aaron Burr was happening. Aaron Burr was organizing his “X affairs”—the invasion of Mexico—in Britain when he was expelled from Britain in April, 1809. The British government arranged for Burr’s passage to Helgoland, a British-held island in the North Sea which was a center of smuggling and intrigue against Napoleon. Burr’s expulsion was a sham on the part of the British government, as Burr’s friends told Governor Claiborne’s investigator later that year.729

There were British ships in the Caribbean. Burr’s relative, Sir George Prevost, commanded an invasion force of 10,000 British troops, which captured the French islands of Martinique and Guadelupe in January, 1809-February,1810. American officials were worried that British troops would invade New Orleans and West Florida.

American volunteers invaded Baton Rouge in 1810 and established the short lived Republic of West Florida, which was annexed by the United States in October, 1810 as part of the Territory of Orleans.

Francis Newman, a 23 year old American army officer, wrote to his wife’s cousin in New Orleans on May 1st, 1809. He was no ordinary army officer. Newman was the illegitimate child of an English nobleman and an American woman—who were both married to others at the time—who later settled in the Baltimore area. The young officer had married into a distinguished Spanish Creole family in New Orleans, a leading family in the sugar cane industry.

Newman’s wife was pregnant, and he wrote to her cousin Joseph Solis from Natchitoches, the American army outpost on the edge of Louisiana Territory, 100 miles west of New Orleans.

… My dear cousin, I am afraid to give you the details on a plan which is not yet clear to me. I would simply advise you to tell my father-in-law, to try to sell and leave the country, and your father, too. Tell them to avoid getting caught up in the horrible disaster that I see as inevitable.

The next letter followed quickly, on May 19th. Newman told his cousin that Manuel Salcedo—the Governor of Texas from 1808 until his execution in 1813—was conspiring with American army officers to declare Mexican independence from Spain. The letter stated the French emigres from Cuba in New Orleans were going to support the revolution.

The final letter concerning the conspiracy was dated July 20th. Newman reported he heard Governor Salcedo at a dinner say that he had 15,000 men at his disposal and more were joining the independence movement every day. Newman was worried his life was in danger if his part in revealing the conspiracy was known, and told his cousin to keep his identity hidden.

On September 3rd, 1809, Governor Wilkinson sent copies of the three letters, which had been given to him by the Mayor of New Orleans, to Secretary of War Eustis. The general said the letters were supposedly written by Francis Newman, a young artillery officer, who was “an Englishman by birth, [and who] was foisted onto the service I know not how.” Wilkinson said the letters were fabricated and Newman’s name was forged.730

Newman’s father-in-law and his brother, the father of Joseph Solis, had given Newman’s letters to the Mayor. The two men were arrested and jailed on a $50,000 bond. Eventually, a Grand Jury declared the letters were forgeries and they were acquitted and released from jail in December.731

In November, after swearing the letters were forgeries, Francis Newman received a promotion to captain. Captain Newman later commanded the strategic Fort Petit Coquilles (the site of the later Fort Pike) during the attempted British invasion of New Orleans in 1815.732

Governor Claiborne thought the letters were genuine, and he reported to Secretary of State Robert Smith on November 12th that he had heard Governor Salcedo had been arrested and the province of Texas was “much agitated.” Claiborne was also trying to secure the release of two American schooners out of New Orleans, which were being held in Yucatan on the suspicion they were engaged in activities against the Spanish government.

Claiborne sent his Adjutant General, Colonel Henry Hopkins, out in the field to investigate. On December 31st, at the close of the tumultuous year of 1809, Governor Claiborne wrote to Secretary of State Robert Smith telling him what Colonel Hopkins had discovered:

In a Letter which Colo Hopkins had addressed me, dated La Fourche [The Forks], November 23, 1809 he says—“I have had a nocturnal interview with two persons residing in this place, one by the name of Hopkins, a Kinsman of C. Taylor and reported to the natural son of Colonel Burr;—and the other Doctor Savage the Brother in Law of Edward Livingston [Auguste Davezac]. From these men I obtained the following information,—Burr was never ordered from England—Burr would have received an appointment in the Revolutionary Army of Spain, if his want of the knowledge of the Language had not been an obstacle;—Burr among other enterprises in person, was to encamp in the Spanish Dominions, and before the feeble Government of Spain could remove them, they would be joined by twenty thousand of the most brave and enterprising men of the United States.

We have in this Territory many persons of similar characters to Hopkins and Savage; and whose frequent conversations as to the facility of revolutionizing Mexico are calculated to excite the people to Jealousy of our neighbors.

Claiborne went on to report that the Solis brothers had been acquitted of libel by a Grand Jury, and that Francis Newman had sworn his letters were forgeries.733

Wilkinson had sent Francis Newman’s three letters, written in French, to Secretary of War Eustis on September 3rd. Dr. Eustis was not only Aaron Burr’s closest friend, he was the physician to both Burr and his daughter Theodosia. The wonder is that Eustis had been appointed Secretary of War, with no military experience beyond that of serving as a physician in the Revolutionary War. President James Madison had appointed him to the cabinet in the interest of party unity.

Eustis was also from Massachusetts, the center of the secessionist movement of the Northern Confederacy. It seems reasonable to assume that Secretary of War Eustis was trying to get American troops out of New Orleans in order to facilitate the secret goals of Aaron Burr and the Northern Confederacy working with Great Britain to invade Mexico. General Wilkinson, on his way to New Orleans, had been entertained at Norfolk and Charleston, where he had publicly called Madison’s new Secretary of War a “black mouthed Federalist,” and had proposed a toast to—

The New World, governed by itself and independent of the Old.734

This is the heart of the matter—the struggle between Burr and his British connections and Wilkinson and his American connections to revolutionize Mexico. Burr’s way would lead to the establishment of a new country, and the break away of the Northern Confederacy from the United States. Wilkinson’s way would lead to what eventually happened—the establishment of independent republics in Spanish territories which later joined the United States of America.

It was after the letters by Francis Newman became public knowledge that Wilkinson finally obeyed Eustis’s orders to start moving the troops 300 miles up river to the Natchez area. As Governor Claiborne had predicted, it was hazardous to the health of the men. Wilkinson provided a table of official army records in his Memoirs. A total of 794 men died and 166 men deserted of the about 2,000 troops sent to defend New Orleans against British attack in 1809. Of those deaths, 590, or 74%, occurred after the troops left Terre aux Boeufs.735 It took weeks for the troops to move upriver to Natchez, in the heat of summer during the malarial season.

General Wilkinson was relieved of his command in October and ordered to report to Washington for congressional investigations. He married the daughter of the surveyor general of Louisiana, Celestine Trudeau, on March 5th, 1810 before leaving for the federal city. Twin daughters were born to the general and his wife in 1816. In his retirement, the general and his new family lived on a plantation in Plaquemines Parish, where he grew sugar and cotton in the rich delta lands at the very tip of the New Orleans pennisula.

General Wilkinson and John Smith T had their own filibuster plans for the invasion of Mexico in 1810. This was the true reason for their assassination of Meriwether Lewis. Lewis may not have even realized they were planning another filibuster. They would have wanted Lewis killed if they believed—or knew—that he was carrying evidence to Washington implicating them in major land claims fraud. The land claims of the large land holders were going to be examined by Judge Lucas and the other two commissioners in 1810. Wilkinson had set up many of these deals when he served as first governor of the territory and Smith T was heavily invested in the lead mine district. Meriwether Lewis was simply too honest to remain the Governor of Louisiana Territory. Any resulting actions concerning land fraud would seriously interfere with their time-dependent plans to participate in the first revolution for Mexican Independence.

As soon as Lewis’s death was reported in St. Louis, an expedition to Sante Fe set out on a reconnaissance mission. On December 28th, 1809, Joseph Charless, editor and publisher of the newly renamed Louisiana Gazette, reported that:

We are informed that about the 20th Ult. [November 20th] Capt. R. Smith, Mr. McLanahan and a Mr. Patterson set out from the district of St. Genevieve upon a journey to St. A Fee, accompanied by Emmanuel Blanco, a native of Mexico. We presume their object are mercantile; the enterprise must be toilsome and perilous the distance computed at 5 to 800 miles, altogether thru a wilderness heretofore unexplored.736

“Capt. R. Smith” was Reuben Smith, the brother of John Smith T. “Mr. McLanahan” was Josiah McLanahan who served as Sheriff of St. Louis when Wilkinson was governor of the territory. “Mr. Patterson” was 25 year old James Patterson of the town of Pulaski, in Giles County, Tennessee.

Patterson went to the lead mine district of Missouri in the spring of 1809 with three slaves. His father was a prominent leader in Giles County. The Pattersons must have known Smith T. The “T” of Smith T stood for Tennessee and Smith T had once claimed ownership of the northern half of Alabama under fraudulent land titles in the massive Yazoo land scandal. John Smith T had deep connections to the area.

The Early History of Giles County, Tennessee says that James-Patterson and his associates were arrested when they reached Sante Fe on charges of being spies for the French government. They were imprisoned in Chihauhau for 9 months under heavy irons, and in jail for another 9 months after they were released from the irons. They suffered greatly. The history relates:

He [Patterson] was a Mason and the priest who visited him was also a Mason, and through his influence, as he supposed their condition was rendered more tolerable. At the end of eighteen months they were turned out of prison but not allowed to leave the city. Smith was a gun-smith and a very ingenious mechanic. He repaired gun-locks, etc., and invented a machine to mill their silver coin in moulding the metal, which he turned to some profit. The Revolution which finally resulted in the independence of Mexico, commenced after they were arrrested.

Don Miguel Hildago the first leader of the revolution, was captured with others of the insurgents and taken to Chihauhau, whilst Mr. Patterson and his party were there; and [Hildago] was there shot in July, 1811. Mr. Patterson witnessed the execution….

Colonel Nelson Patterson (the father of Jas. Patterson) saw in a newspaper an extract from a Vera Cruz paper, published in the City of Mexico, an account of their capture and imprisonment, and wrote to the authorities in Washington. The U. S. Government demanded their release from Spain. After having been nearly three years prisoners they were permitted to leave, the three negroes and Indians declined to return with them…. The Governor’s Secretary was a Mason, and he told Mr. Patterson privately not to take the route the Governor designated; that the Governor had posted a band of Indians at a certain watering place, on the way where they were to stop, with strict instructions to kill all of them …

The Nashville Democratic Clarion newspaper reported their arrival in Natchez in a story dated May 6, 1812. They were reported to have said:

That the country is in a complete state of civil war, and that nothing but arms are wanted to shake off the trammels of the old Spanish government….The country, according to their account, abounds in gold, silver and iron ores—the climate salubrious and pleasant, and the land, considering the great droughts, that are experienced there, very productive.737

The next month, in June, 1812 a joint Mexican-American filibuster expedition, called the Gutiérrez-Magee Expedition, began rendezvousing near the Sabine River and Natchitoches. Bernardo Gutiérrez de Lara, a leader in Father Hildago’s revolution, visited Washington in December, 1811 seeking aid from Secretary of State James Monroe. A 24 year old army officer, a protegé of General Wilkinson, Lieutenant Augustus Magee, resigned his commission in the U. S. Army in June, 1812 and joined with Gutiérrez to lead the filibuster into Mexico. James Patterson, Josiah McLanahan, and Reuben Smith were leaders of one of the three groups assembling on the Neutral Ground. The general’s son, Joseph Biddle Wilkinson, participated in the expedition.738

The Gutiérrez-Magee Expedition ultimately ended in failure after many twists and turns and perhaps the murder of Magee by arsenic. As this book is a biography of Meriwether Lewis—and the story of the conspiracies and filibusters to invade Mexico is as lengthy and complex as any of the topics in this book—the story, regretfully, has to end here.

Mexico would finally achieve its independence in 1821. In 1823, General Wilkinson presented his Gilbert Stuart painting of President George Washington to the Congress of Mexico. The general died in 1825 in Mexico at the age of 68, while he was waiting to receive a Texas land grant from the Mexican government. He was buried in a Catholic Cemetery in Mexico City.739

These attempts to invade Mexico in 1809–1812 form the basis of the evidence of why I believe Meriwether Lewis was assassinated in October, 1809 by General Wilkinson and John Smith T. Their underlying motives were the lure of the fabulous wealth of the silver mines and other mineral resources of Mexico, and their desire to benefit through land speculation and commercial trade with a newly-formed independent government of Mexico.

In 1811, during his court martial at Frederick Town, Maryland, the general created a false document called the “Russell Statement.” He would have been very pleased to know that his forgery would cause trouble in the Twentieth Century.

Editor Donald Jackson discovered the “Russell Statement” in the Jonathan Williams Archives of the University of Indiana’s Lilly Library, and decided to publish it in the first edition of his Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. The authenticity of the document was questioned by Vardis Fisher, author of Suicide or Murder?: The Strange Death of Governor Meriwether Lewis. Jackson’s and Fisher’s books were both published in 1962.

Fisher discussed the Russell Statement in his book, and wrote:

But for us there is something strangely unlike Russell in his manner of writing this account of Lewis’s death. In his two letters to Jefferson his friendship and his feeling for Lewis shone through at every point. Here he says that Lewis killed himself in “the most cool desperate and Barbarian-like manner”—strange words from an army man whose profession was killing with guns.740

In 1996, James E. Starrs organized the Coroner’s Inquest which was held in Lewis County, Tennessee where the Meriwether Lewis National Monument & Gravesite is located. The Russell Statement was examined by two document examiners, Gerald B. Richards, former head of the F. B. I. Documents Operations, and Dr. Duayne Dillon, former Acting Director of the San Francisco Police Department Crime Lab. The two experts examined the Russell Statement independently of each other and concluded it was a forgery.741

Their testimonies are recorded in The Death of Meriwether Lewis: A Historic Crime Scene Investigation, which I co-authored with Professor Starrs, and which was first published in 2009, the 200th anniversary of the death of Lewis. A second “New Evidence Edition” was published in 2012. The “Russell Statement” is an interesting document for several reasons—how it was constructed as a cover up; why it was created during a court martial seemingly entirely unrelated to the question of Lewis’s death, and who did the actual writing of it.

[26 November 1811]

Governor Lewis left St. Louis late in August, or early in September 1809, intending to go by the route of the Mississippi and the Ocean, to the City of Washington, taking with him all the papers relative to his expedition to the pacific Ocean, for the purpose of preparing and putting them to the press, and to have some drafts paid which had been drawn by him on the Government and protested. On the morning of the 15th of September, the Boat in which he was a passenger landed him at Fort pickering in a state of mental derangement, which appeared to have been produced as much by indisposition as other causes. The Subscriber being then the Commanding Officer of the Fort on discovering from the crew that he had made two attempts to Kill himself, in one of which he had nearly succeeded, resolved at once to take possession of him and his papers, and detain them there untill he recovered, or some friend might arrive in whose hands he could depart in Safety.

In this condition he continued without any material change for five days, during which time the most proper and efficatious means that could be devised to restore him was administered, and on the sixth or seventh day all symptoms of derangement disappeared and he was completely in his senses and thus continued for ten or twelve days. On the 29th of the same month he left Bluffs, with the Chickasaw agent the interpreter and some of the Chiefs, intending to proceed the usual route thro’ the Indian Country, Tennissee and Virginia to his place of distination, with his papers well secured and packed on horses. By much severe depletion during his illness he had been considerably reduced and debilitated, from which he had not entirely recovered when he set off, and the weather in that country being yet excessively hot and the exercise of traveling too severe for him; in three or four days he was again affected with the same mental disease. He had no person with him who could manage or controul him in his propensities and he daily grew worse untill he arrived at the house of a Mr. Grinder within the Jurisdiction of Tennissee and only Seventy miles from Nashville, where in the apprehension of being destroyed by enemies which had no existence but in his wild immagination, he destroyed himself, in the most cool desperate and Barbarian-like manner, having been left in the house intirely to himself. The night preceeding this one of his Horses and one of the Chickasaw agents with whom he was traveling Strayed off from the Camp and in the Morning could not be found. The agent with some of the Indians stayed to search for the horses, and Governor Lewis with their two servants and the baggage horses proceeded to Mr. Grinders where he was to halt untill the agent got up.

After he arrived there and refreshed himself with a little Meal & drink he went to bed in a cabin by himself and ordered the servants to go to the stables and take care of the Horses, least they might loose some that night; Some time in the night he got his pistols which he loaded, after every body had retired in a Separate Building and discharged one against his forehead not making much effect—the ball not penetrating the skull but only making a furrow over it. He then discharged the other against his breast where the ball entered and passing downward thro’ his body came out low down near his back bone. After some time he got up and went to the house where Mrs. Grinder and her children were lying and asked for water, but her husband being absent and having heard the report of the pistols she was greatly allarmed and made him no answer. He then in returning got his razors from a port folio which happened to contain them and Seting up in his bed was found about day light, by one of the Servants, busily engaged in cutting himself from head to foot. He again beged for water, which was given to him and as soon as he drank, he lay down and died with the declaration to the Boy that he had killed himself to deprive his enemies of the pleasure and honour of doing it. His death was greatly lamented. And that a fame so dearly earned as his should be clouded by such an act of desperation was to his friends still greater cause of regret.

(Signed) Gilbert Russell

The above was received by me from Major Gilbert Russell of the [blank] Regiment of Infantry U. S. on Tuesday the 26th of November 1811 at Frederick-town in Maryland.

J. Williams

The phrase in the document that is the most loathesome and offensive is—

… he lay down and died with the declaration to the Boy that he had killed himself to deprive his enemies of the pleasure and honour of doing it.742

It is the wicked statement of a sociopath. Wilkinson was confessing he took pleasure in killing Meriwether Lewis and considered it an “honour” to have committed the crime.

The general had good reason to fear Lewis—in 1796, Lewis was General Wayne’s trusted courier in the last days of Wayne’s life; in 1801, Lewis provided Jefferson with the names of officers who were close associates of Wilkinson and who were dismissed from the service; in 1807, Lewis replaced Wilkinson as Governor of Louisiana Territory; and in 1809, when the general’s enemies were clamouring for his dismissal, Lewis was bringing damaging information to Washington that undoubtedly would have brought the general’s career to an end.

General Wilkinson had asked for a military court-martial to clear his name. He was being harassed by his enemies in Congress and wanted to end their investigations. The charges brought against him in 1811 were:

(1) that he received pay as a secret agent of the government of Spain from 1793–1804, with ten specific accusations.

(2) that he engaged in treasonable correspondence with Spanish officials in 1795 regarding the dismemberment of the union, with five specific accusations.

(3) that he conspired with Aaron Burr and his associates in 1805–06 to set up an independent empire of western states and territories.

(4) that while commanding the army of the United States in 1805–06, he participated in the conspiracy of Aaron Burr and his associates, and he did not make “any timely discovery of their pernicious designs.”

(5) that he conspired with Aaron Burr and his associates to “set on foot a military expedition against the territories of a nation then at peace with the United States.”

(6) that he disobeyed orders and instructions from the War Department, dated April 30, 1809, to remove the troops from New Orleans to the “high ground in the rear of Fort Adams and to the high ground in the rear of Natches in Mississippi Territory” and instead removed the troops to a station called Terre aux Boeufs below New Orleans, and remained there until September.

(7) that he had neglected his duty in regard to the supply of provisions during the summer and autumn of 1809, with three specific accusations.

(8) that there was misapplication and waste of public monies and supplies, with three specific accusations.

To all of these charges, the general pled “not guilty.”

The question remains—what motivated the general to prepare a false statement in the name of Major Russell regarding the death of Lewis? It had absolutely nothing to do with the charges brought against him in 1811. It has taken seven years of research for me to construct an answer as to why the “Russell Statement” was created. First I learned from Jim Starrs that the original was in the Jonathan Williams Collection of Lilly Library at the University of Indiana, and obtained a copy of the handwritten document.

Then I realized the statement coincided with the general’s court martial in Frederick-town and that it was created during the trial proceedings. I found the hand written records of the court martial in a confusing jumble on microfilm prepared by the National Archives. Eventually I got very lucky and found a typed transcript of the court-martial at the Historical Society of Frederick County, prepared by a researcher in 1976. Even in typed transcript, I didn’t seriously review the proceedings.

Meanwhile, I acquired a colleague and friend in my investigations, Earl Weidner of Baton Rouge. Earl had his own interests in General Wilkinson and proved to be a diligent investigator on the trail of who actually wrote the forgery for the general. After several years of obtaining handwriting samples of various suspects, Weidner found the answer. It was a clerk in the War Department named Lewis Edwards. It makes sense because the general employed him as a scribe during the court martial and his preparations for congressional investigations. Edwards wasn’t mentioned by name. It can’t be proved except by the kind of professional handwriting analysis done at Coroner’s Inquest in 1996, but it seems very likely.

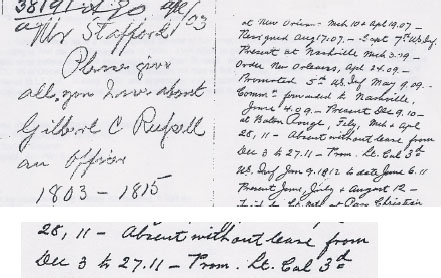

The next stages of research took years for me to comprehend the implications of what I discovered. I found records concerning Russell at the Alabama State Archives which revealed that Major Russell—who was testifying at the court-martial—went Absent With Out Leave (AWOL) from December 3rd through December 27th, 1811. The court-martial judges delivered their verdict of “not guilty” on December 25th. The so-called “Russell Statement” was composed on November 26th.

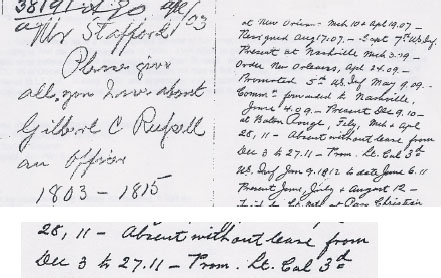

This is the information on file at the Alabama State Archives concerning Gilbert C. Russell going AWOL and his promotion.

Major Russell disappeared shortly after the statement was written, and reappeared after the general was declared not guilty. Russell was afraid of being another victim of an assassination by the general, because the only way the statement would have any validity was if Russell was no longer around to dispute the information contained in the statement. That was the final piece of the puzzle for me—that the “Russell Statement” was prepared in advance of another planned assassination. Major Russell was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel in the 3rd U. S. Infantry two weeks after the trial ended, on January 9th, 1812. From his going AWOL and then receiving a promotion, we may safely assume that others in the government realized the general was an assassin.

What provoked the general during his court-martial? It must have been that Major Russell testified on November 5th that Major Seth Hunt told him that General Wilkinson had tried to get him [Seth Hunt] killed. In 1806 Russell and Hunt had traveled together to Washington City and Russell said Hunt was bringing evidence against Wilkinson that would “remove the General from both his military and civil offices.” The general must have been afraid that, since Russell had testified about Seth Hunt’s accusation, Russell was next going to accuse the general of Meriwether Lewis’s assassination—which is why the general prepared the “Russell Statement” cover up.743

There is one final issue regarding Lewis’s death by suicide—the letter written by Thomas Jefferson for the Lewis and Clark Journals. Jefferson was asked to contribute a biography of Meriwether Lewis for the journals, which were published in 1814. He wrote about choosing Lewis to lead the expedition:

Captain Lewis, who had then been near two years with me as private secretary, immediately renewed his solicitations to have the direction of the party. I had now the opportunity of knowing him intimately. Of courage undaunted, possessing a firmness & perserverance of purpose which nothing but impossibilities could divert from it’s direction, careful as a father of those committed to his charge, yet steady in the maintenance of order & discipline, intimate with the Indian character, customs & principles, habituated to the hunting life, guarded by exact observation of the vegetables & animals of his own country, against losing time in the description of objects already possessed, honest, disinterested, liberal, of sound understanding and a fidelity to truth so scrupulous that whatever he should report would be as certain as if seen by ourselves, with all these qualifications as if selected and implanted in nature in one body, for this express purpose, I could have no hesitation in confiding the enterprize to him.

Jefferson wrote about his time as governor—

A considerable time intervened before the Governor’s arrival at St. Louis. He found the territory distracted by feuds & contentions among the officers of the government & the people themselves divided by these into factions & parties. He determined at once, to take no side with either; but to use every endeavor to conciliate and harmonize them. The even-handed justice he administered to all soon established a respect for his person & authority, and perseverance & time wore down animosities and reunited the citizens again into one family.

He wrote about Lewis’s mental state—

Governor Lewis had from early life been subject to hypocondriac affections. It was a constitutional disposition in all the nearer branches of the family of his name & was more immediately inherited by him from his father. They had not however been so strong as to give uneasiness to his family. While he lived with me in Washington I observed at times sensible depressions of mind, but knowing their constitutional source, I estimated their course by what I had seen in his family. During his Western expedition the constant exertion which that required of all the faculties of body & mind, suspended these distressing affections; but after his establishment in St. Louis in sedentary occupations they returned upon him with redoubled vigor, and began seriously to alarm his friends. He was in a paroxysm of one of these when his affairs rendered it necessary for him to go to Washington.744

This last statement should be considered as nothing more than an obligatory defense of the suicide story.

Jefferson dated the letter to the publisher, “Monticello, Aug. 18. 1813.” It was the day of Meriwether Lewis’s birthday. This book opened with the birth of Meriwether Lewis in 1774 at Locust Hill, just a few miles from Monticello, and now closes with this sad testimony from Jefferson 39 years later.

Meriwether Lewis was an extraordinary person, fully meriting Jefferson’s praise of his character and accomplishments. His life story begins with the start of the American Revolution for Independence and ends with the start of the Mexican Revolution for Independence. It was a revolutionary era, and in telling the story of his life it has been necessary to tell the story of James Wilkinson, because I believe General Wilkinson assassinated Meriwether Lewis and arranged the story of his suicide as a cover up.

The story of Wilkinson has necessarily led to a discussion of fifty years of Wilkinson’s intrigue. He was, and remains, a convenient “scape goat” for both his contemporaries and historians, who blame him for any number of sins over this period. What they can’t explain is why he was retained in power by the first four presidents, and survived numerous congressional investigations and military courts. In this book I have attempted to demonstrate that Wilkinson was both a patriot and a sociopath. His contemporaries accused him of being an assassin, but historians have concentrated on his role as Spanish Agent #13 and not explored the assassination accusation.

Meriwether Lewis’s achievements were many. The most well known is his successful mission to the Pacific—reinforcing the United States claim to the Pacific Northwest and a continental empire—and his governorship of Louisiana Territory during a troubled time. But perhaps his most lasting accomplishment is the contribution he made to the natural sciences and description of life as he saw it during his journey to the Pacific. As Jefferson wrote, he was—

honest, disinterested, liberal, of sound understanding and a fidelity to truth so scrupulous that whatever he should report would be as certain as if seen by ourselves …

Lewis’s report on Indian cultures dating back thousands of years, and his natural history observations will be remembered for all time. He also deserves to be remembered as an American hero, without the false label of suicide clouding his reputation.