5 Mobility: Transport Is a Real Estate Issue—The Design of Urban Roads and Transport Systems

The Need for Mobility

Cities are primarily large labor and consumer markets. These markets work best when the possibility of contact increases between workers and firms, among firms themselves, and between consumers and commercial and cultural amenities. The term “mobility,” in the context of this book, defines the ability to multiply these contacts with a minimum of time and friction.

A worker’s ability to choose among many jobs and a firm’s ability to select the most qualified workers depends on mobility. Mobility is not defined by the ability to get to one’s current job quickly, but by the ability to choose among all jobs and amenities offered in a metropolitan area while spending less than 1 hour commuting. Mobility increases when the number of jobs and amenities that can be reached within a specific amount of time increases. Because of the impact of mobility on the welfare of a city, it is important to measure it and monitor its variations—up or down—as a city’s population increases, its land use changes, and its transport system improves or deteriorates. I will propose ways to measure and compare mobility in different cities in the section “Mobility and Transport Modes” later in this chapter.

The objective of an urban transport strategy should be to minimize the time required to reach the largest possible number of people, jobs, and amenities. Unfortunately, many strategies, such as “compact cities,” only aim to minimize the distance traveled by inhabitants. These strategies reduce the income of the poor, for whom employment opportunities are reduced to jobs located within a narrow radius of their homes.

Cities thrive on changes, possibilities, and innovations. Therefore, an urban transport system that would solely minimize travel time between home and current jobs for all workers would result in poor mobility, as in the future, workers might not be able to reach many alternative jobs that would improve their job satisfaction or salary.

Mobility and Recent Immigrants

During a recent visit to the Tenement Museum in New York, a docent told us that in the 1850s, immigrants who were “fresh off the boat” would typically stay only a few months in a tenement; they would then keep moving as their employment and financial circumstances changed. A typical length of stay in the same tenement would be about 6–8 months. My wife and I then looked at each other, remembering that this was exactly what we did when—in January 1968—we were also “fresh off the boat” in New York. We changed apartments three times in 30 months. We moved from a flophouse on the Upper East Side that was soon going to be demolished, to a studio apartment in an “old law tenement” on the Upper East Side, and then to an entire floor in a townhouse in Brooklyn Heights. I also changed job three times. Each time, I changed for a more interesting job and a higher salary. This is the type of mobility that we will discuss in this chapter: the ability to move from job to job and from dwelling to dwelling made possible by a transport infrastructure that gives access to millions of potential jobs in less than 1 hour of commuting time.

This mobility was made possible by a buoyant housing and job market, ensuring a low transaction cost of changing jobs and location. By contrast, in Paris (where we came from), housing mobility was hampered by 2-year leases that could not be broken without penalties. Additionally, job mobility was frowned on as a sign of instability—changing jobs three times in 30 months would have resulted in a resume that raised a lot of eyebrows.

When—after just 6 months with my first employer in New York—I found a job that was a better fit with my long-term interests, I was terribly embarrassed by the prospect of telling my employer that I was quitting. My colleagues at work reassured me that this was done all the time in New York, and that a higher salary was a very honorable reason to change jobs. Indeed, my employer gave me a good luck party when I quit!

This is mobility. A flexible labor market, an open housing market—the flophouse with its low standards but very low rent was essential to getting us started—and a transport system that is fast, affordable, and extensive enough to allow individuals to look for jobs in an entire metropolitan area rather than just in limited locations.

The benefits of urban mobility are not limited to saving on commuting time. Mobility is also necessary to facilitate random face-to-face encounters between individuals of different cultures and fields of knowledge. These serendipitous encounters increase cities’ creativity and productivity. The multiplicity of easily accessible meeting places available outside the work setting increases the possibilities of chance encounters and therefore increases the spillover effects found in large cities. The agora of ancient Greek cities or the forum of Roman cities were precisely fulfilling these needs. Agoras and forums were places where people assembled to conduct business, to meet friends, to attend religious ceremonies and political meetings, to receive justice, and to frequent public baths. Modern cities have many of these functions in separate locations. Unfortunately, rigid zoning regulations often constrain the existence and location of these multifunction places.

When transport systems provide adequate mobility, then the large concentration of people in metropolitan areas increases productivity and stimulates creativity. Empirical data confirm the link between large human concentrations and productivity. Physicists from the Santa Fe Institute have shown that, on average, when the population of a city doubles, its economic productivity per capita increases by 15 percent.1

The interesting findings of the Santa Fe Institute’s scientists should be qualified, though. Their database included 360 US metropolitan areas with, by world standards, a very good transport infrastructure network that ensures mobility together with spatial concentration. In a way, these scientists’ use of the word “cities” assumes the availability of transportation. It would be wrong to interpret their work as demonstrating that human concentration alone increases productivity.

Mobility explains the link between city size and productivity. Human concentration alone does not increase productivity. Some rural areas in Asia have gross densities that are higher than the density of some North American cities like Atlanta or Houston, for instance. However, in these rural areas, mobility is poor to nonexistent between villages. In absence of mobility, there is no increase in productivity despite the high density. The productivity of cities therefore requires both concentration of people and high mobility.

When the time and cost required to move across a city increase, mobility decreases. When this happens, workers have fewer choices among the potential jobs available in a city, and firms have fewer choices when recruiting workers. In these conditions, metropolitan labor markets tend to fragment into smaller, less productive ones; salaries tend to decrease, while consumer prices increase because of lack of competition. In practical terms, labor market fragmentation means that a worker might not find the job for which she is qualified, because she cannot commute in less than 1 hour to the firm who could employ her. Conversely, the firm looking for a worker with specialized knowledge cannot find him because he cannot reach the firm in less than a 1-hour commute. Workers having to commute for more than 1 hour each way are penalized by a social cost that progressively destroys their personal life. Poor mobility may also result in high transport overhead cost for firms having to exchange goods and services in an urban area. Increasing mobility in urban metropolitan areas is therefore indispensable to the welfare of urban households as well as to the creativity and prosperity of firms.

In a city, a worker’s mobility often depends on his income. In some large Indian cities, for instance, the poorest workers can only afford to walk to work. Even a very long walk of 90 minutes would give them access to a very small number of possible jobs, decreasing their potential earnings. Planners should measure separately the mobility of different income groups, accounting for the modes of transport that each group can afford.

Mobility generates not only benefits but also costs, including congestion, pollution, noise, and accidents. To reduce those nuisances, many urban planners advocate limiting or at least discouraging mobility. They dream of creating cleverly planned land use arrangements that would require only short trips easily covered by walking or bicycling, even in megacities. These utopian land use arrangements usually rely on complex land use regulations2 that would enable planners to match employers’ locations with employees’ residences.

Mobility is an urban necessity that must be encouraged, not curtailed. Poor mobility keeps much of the economic potential of existing large cities from being realized. Unfortunately, in many cities, the lowest-income households suffer the most from poor mobility. They would enormously benefit if their mobility increased, so that they could look for jobs as well as cultural and commercial amenities throughout an entire metropolitan area. Instead, they are limited to the small area around their homes, circumscribed by their limited mobility.

As urban metropolitan areas increase in size and population, their potential large labor markets may fragment into smaller markets because of the lack of mobility. It is therefore necessary to differentiate between the potential and actual size of the labor market. The potential size is equal to the number of workers and jobs in a city. Its real size equals the average number of jobs that a worker can reach in a 1-hour commute.

Commuting Trips and Other Trips

Throughout this chapter, we will examine mobility in the context of commuting trips (trips from home to work and back), even though commuting trips are only a fraction of urban trips. In the United States in 2013, commuting trips represented only 20 percent of weekday urban trips, 28 percent of vehicle kilometers traveled, and 39 percent of public transport passenger-kilometers traveled.3

Households and firms generate many types of trips that have different purposes (e.g., trips to work, to school, to visit friends, to shop). Many trips have multiple purposes. Transport engineers call such excursions chained trips or linked trips. On a chained trip, a person might drop a child off at school, go to work, and shop, for instance. Chained trips are both convenient for the commuter and efficient in terms of transportation, as they save time and reduce the distance traveled compared with the same trips done separately. For the United States, the Pisarski and Polzin study indicates that 19 percent of all women’s trips are chained trips compared to 14 percent for men. While chained trips are transport efficient, they are nearly incompatible with public transport and carpooling.

Despite commuting trips representing only a fraction of all trips, I will continue to use them to measure mobility. For the economic viability of a city, the most important trips are those to and from work—the commuting trips—as the labor market generates the wealth that makes the other trips possible. In addition, the timing of commuting trips is usually not chosen by the traveler. Instead, they often occur at peak hours, and they are the ones causing most congestion and pollution. Therefore, the transport infrastructure capacity needs to be calibrated on the demand during peak hours, largely determined by commuting trips.

Some elective trips, like holiday shopping or leisure trips on summer weekends, may also cause heavy congestion, but they are seasonal and therefore do not have such high annualized costs as the daily congestion caused by commuting trips.

Improving Mobility Is Not As Simple As Making Cities Denser

Ideally, the closer people and firms are to each other, the shorter the trips required to meet and transact business would be. In an urban area with a given population, people, firms, and amenities are closer to one another when population and job densities are higher. It may seem, therefore, that for a given population, mobility simply increases when density also increases due to the shorter distances between households and firms. Similarly, it would seem that mobility would decrease as the distance between firms and employees increases.

Unfortunately, things are not that simple. Let us consider the average distance d of commuting trips between random points A and B selected in a city built-up area. For a given population, the distance d will indeed be shorter if the city’s density is higher. However, mobility increases when the time t needed to cover the trip distance d from A to B decreases, and not necessarily when d alone decreases. Therefore, mobility increases not only when the trip distance d decreases but also when the trip travel speed v increases (t = d/v). The trip’s speed v depends on the mode of transport and the area devoted to roads. Therefore, increasing densities may decrease the average distance d between people and jobs, but it may also increase congestion and therefore decrease travel speed v.

Let’s make this come alive through an example. Nineteen-century London, with its sweatshops and slums, was extremely compact. In 1830, according to Shlomo Angel and colleagues,4 London’s population density had reached a very high density of 325 people per hectare. By 2005, however, the density of London had decreased to only 44 people per hectare. The large decrease in London’s density since the Industrial Revolution has not caused a corresponding decrease in mobility. On the contrary, transport modes in London in 1830, largely walking and horse carriages, were much slower than those available in 2015 London with its choice of various motorized transport modes. In 2015, commuters can reach the city center from the suburbs as far as 26 kilometers away in less than 1 hour by public transport. In contrast, in 1830, commutes from the edge of London, about 7 kilometers from its center, would have taken about 1.5 hours. In this case, a seven fold decrease in density did not result in a decrease in mobility; on the contrary, an improvement in transport technology generated an increase in mobility despite the sharp fall in population density.

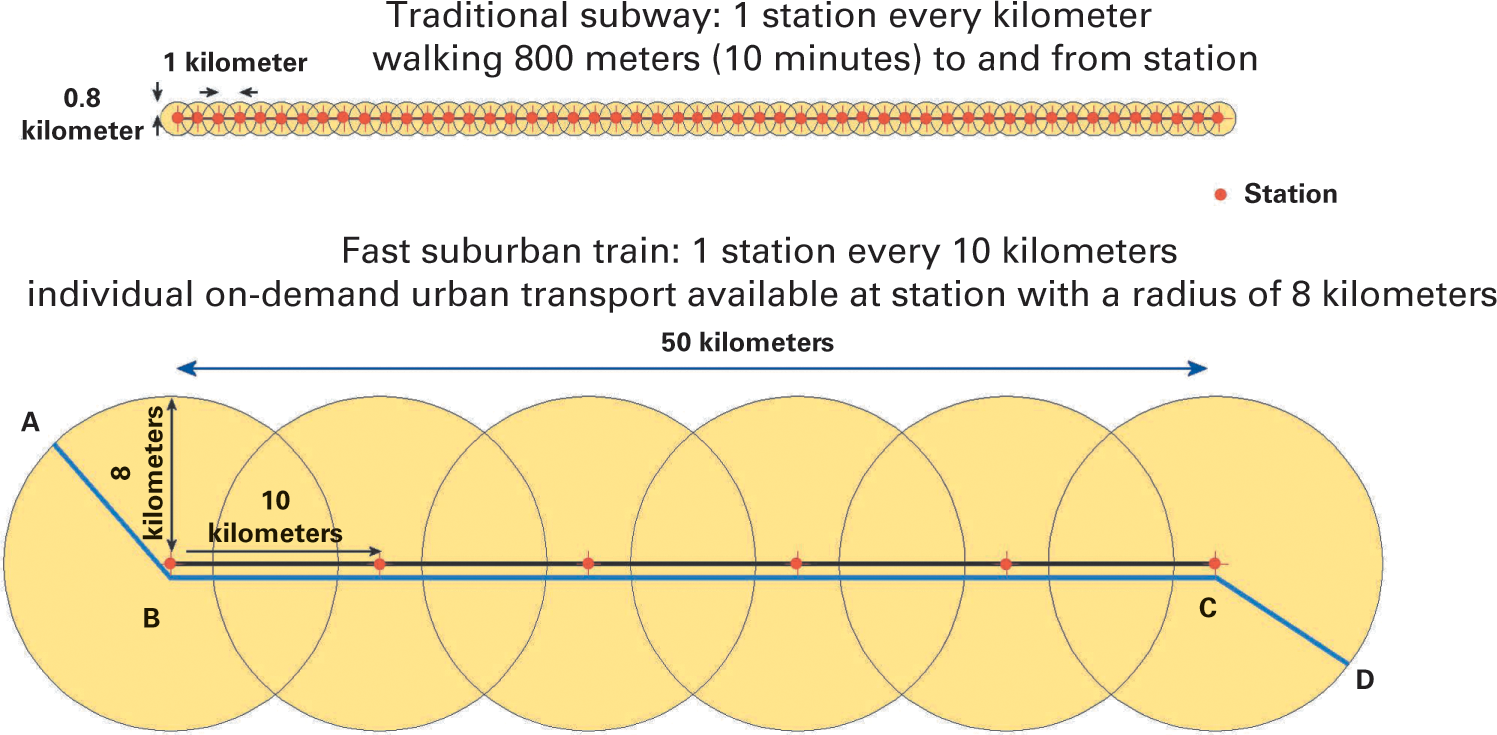

The goal is to reduce the time spent traveling and the cost of transport, not necessarily to reduce the distance between trip origin and destination. The mode of transport and the design of the transport network will have a much more impact on mobility than distance traveled.

How to Increase Mobility as Cities Expand

The population of successful cities is constantly increasing because of the economic advantages provided by large labor markets. To maintain mobility as city populations increase, urban transport systems must adapt to the new size of cities. In relatively small cities—around 200,000 people, like Oxford or Aix-en-Provence—a combination of transport modes like walking, bicycles, and city buses provide adequate means of transport in the downtown area, while individual cars and motorcycles are used for trips in the periphery. However, when a city’s population increases above 1 million, these means of transport become inadequate, and new means of faster transport must be built. Because the land in the center of large cities becomes more expensive, new transport must not only be faster but also should use less of the expensive urban land, hence the necessity to develop underground or elevated transport systems.

Transport systems that may be adequate for a given city size soon become deficient in a larger city. Transport systems cannot just be scaled up but need to be entirely redesigned when cities grow larger. It is futile to use Amsterdam’s or Copenhagen’s transport system as a model for much larger cities like Mumbai or Shanghai.

As the size of cities increases and traditional land use patterns keep changing, it is imperative to keep monitoring mobility, the direct cost borne by commuters, and the negative impact it creates on the city environment.

Mobility Creates Friction

Urban mobility creates friction. The larger the city, the more severe the frictions caused by mobility will become. These frictions include the time and cost required to go from one part of a city to another and the congestion and pollution created by doing so.

The frictions caused by urban transport are not new. Urban congestion did not begin with the advent of cars. A golden age when cities were congestion free never existed. The Latin poet Juvenal, in his Satire III, mentioned the difficulties of moving around ancient Rome in the first century. Traffic congestion in the Roman Empire is even the subject of a recently published book!5 In the seventeenth century, the poet Boileau wrote a satirical poem about les embarras de Paris (the gridlocks of Paris).

At the end of the nineteenth century, pollution due to transport was such a concern that some saw it as a limiting factor in the growth of cities. London was at the time the largest city in the world, with 6 million people. The pollution so reviled then was the enormous quantity of horse manure produced daily by horse-drawn buses and cabs. Indeed, it was a major health concern. Acknowledging London’s future increase in population, scientists projected that the quantity of horse manure produced by transport would soon bury the city like a modern Pompeii! With hindsight, we know that the introduction of the automobile saved London from submersion in manure, but congestion and pollution remain a major constraint in urban transport today.

Various frictions caused by urban transport have been a constant concern since the dawn of urbanization. They cannot be eliminated, at least with current technology, but they can be decreased. These frictions will be discussed separately below: they include direct travel cost, time spent traveling, congestion, pollution, and other indirect costs. Any city that can significantly decrease frictions due to transport will see a corresponding increase in productivity and the welfare of its citizens because more time will be left for work and leisure.

A primary task of city managers should be to minimize the frictions caused by urban transport. This job is never done—as a city expands, the distance covered by commuting trips becomes longer. A city structure and its transport system must adapt continuously to its changing scale. As a city expands from 1 million to 10 million (e.g., as Seoul Municipality did between 1950 and 2015), the original transport system cannot simply be expanded; it must change in nature and technology to reflect the new scale of the labor market being served. The goal is to maintain mobility such that the majority of commuting trips stay below 1 hour, in spite of the much longer distances involved.

The unfortunate tendency of many current traffic managers is to restrict trips to avoid congestion. Instead they should better manage the road space available or adopt new technology to allow even more and faster trips.

The Death of Distance Has Been Greatly Exaggerated

In the “Star Trek” television series, the words “beam me up” were all that was needed to transport people and goods anywhere instantly through the teleportation machine. This imaginary technology allowed universal frictionless mobility. Unfortunately, it was fictional.

If frictionless mobility were possible, the dense concentration of people in cities would not be required. I could start the morning in a small town in New Jersey, a few minutes later have coffee and a croissant in a café in Paris, and a few seconds after finishing my coffee, I could start working in an office in Mumbai, or anywhere else in the world. In a world allowing frictionless mobility, location would no longer matter. Most of us have already replaced some physical trips by virtual ones. For instance, I used to visit bookstores on a regular basis; I now buy my books online, and they are delivered to me electronically. The visit to the bookstore was a face-to-face encounter that has been replaced by a “beam me up” operation, except that it is the book that is being beamed up, not a person.

While the teleportation machine from Star Trek is likely to remain fiction, would communication technology—in particular, increasingly realistic teleconferencing—make location obsolete, providing a substitute for frictionless mobility? Or, in simpler terms, could communication technology replace the face-to-face contacts that generate most of our commuting trips? Indeed, it is much cheaper to move data than to move people. This is precisely the main argument developed by Frances Cairncross in her book The Death of Distance (2001). Cairncross suggests that the Internet and the global spread of wireless technology are increasingly making distance irrelevant. Communication technology would make face-to-face contact obsolete, and, in this sense, we would be getting closer to a Star Trek–like frictionless mobility, replacing the mobility of individuals by that of data. Virtual reality encounters would replace the necessity of “in the flesh” face-to-face encounters.

Work-at-Home Individuals

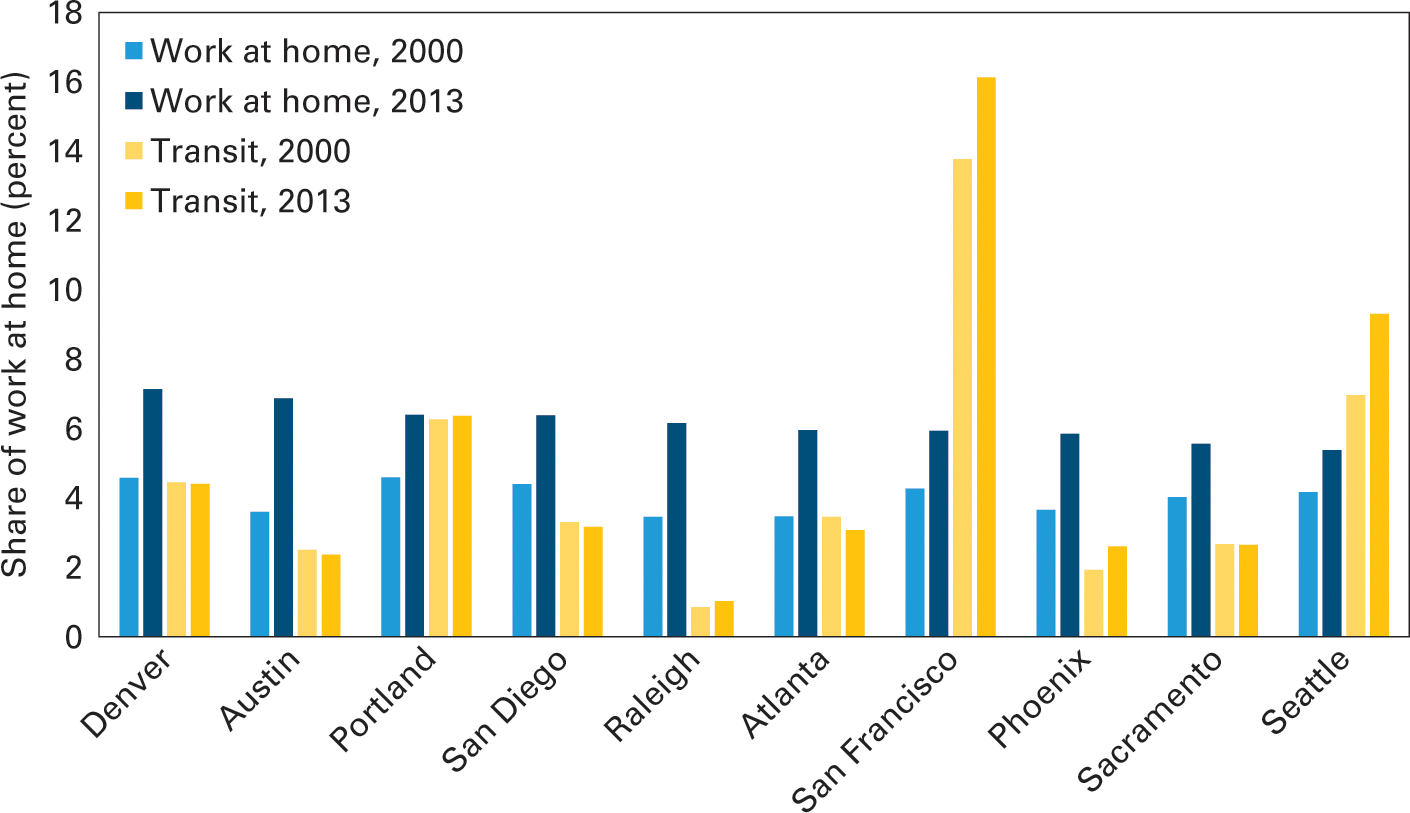

The increasing share of people working at home but constantly connected to a front office seems to confirm Cairncross’ prediction. Among eight of the ten US cities with the largest number of work-at-home individuals (figure 5.1), the share of people working at home is larger than the share of workers using public transport. In all nine cities, the increase of work-at-home individuals has been larger than the increase in public transport users. However, with the exception of San Francisco, all the cities shown on figure 5.1 have rather low densities by world standards. This may explain the low proportion of growth of urban transport compared to the growth of work at home. In addition, many workers commute only a few days a week and are only working at home part-time. If this trend continues, could the home become the main place of work, rendering commuting obsolete and resulting in trips mostly for leisure or personal reasons?

Mode share work at home versus public transport in some US cities. Source: Wendell Cox, NewGeography, May 30, 2015.

Working from home is not new, of course. Up to the early twentieth century, artisans and service workers were often working from home, delivering their finished work to their employers weekly. These included washerwomen and lace makers, but also Swiss farmers making watch mechanical parts. What is new, however, is that clerical and technical workers, who traditionally worked in large office pools, have replaced these manual workers working from home. But is it likely that a very large part of the workforce—say, more than 25 percent—will start working from home full time, significantly reducing peak hour traffic? So far, this possibility seems limited.

A recent Yahoo human resource department’s memo requested employees working from home to resume working at the office, arguing, “Some of the best decisions and insights come from hallway and cafeteria discussions, meeting new people and impromptu team meetings. Speed and quality are often sacrificed when we work from home.” In Silicon Valley, the most successful firms, like Google and Facebook, are building very large headquarters in addition to the large office buildings they recently acquired in downtown San Francisco. These large and costly real estate acquisitions suggest that they do not anticipate that a large part of their workforce will be working full time from home in the future.

The design of the largest Silicon Valley offices, offering their employees an unusual environment with gourmet food cafeterias, gyms, and kindergarten, demonstrates the intention of management to encourage their employees to work in their office and to interact with one another socially as well as professionally. In a way, it seems that Silicon Valley firms are trying to intensify within their offices the knowledge spillovers that are known to happen in large cities. For these reasons, I believe that the number of work-at-home individuals might soon reach a peak and may not affect commuting flow significantly in the future.

If Cairncross had been right in 2001, by 2015 we should have already seen large changes in the price of urban land across the world. The most environmentally attractive but remote rural areas of the world would have higher prices, while the least environmentally attractive, highest-density areas would have lost value. This is not happening. Real estate prices in New York, London, Delhi, and Shanghai are still climbing, proving that the death of distance might have been greatly exaggerated. High real estate prices demonstrate that even in cities where mobility causes severe friction—as in New York, London, or Shanghai—being physically close to a large concentration of people, jobs, and amenities is still worth a very high price.

Measuring a City’s Mobility

A Decrease in Congestion and Pollution Is Not a Measure of Mobility

The objective of urban transport is to increase mobility to maximize the effective size of labor markets. Congestion and pollution are very important constraints on the mobility objective, but they are only constraints. Confusing objectives and constraints when solving problems can lead to false solutions. Urban managers too often try to solve transport problems by focusing exclusively on reducing congestion and pollution without giving much consideration to mobility, as if the objective of urban transport was limited to decreasing the nuisances it causes.

Some policies rely on reducing trip length, others on forcing more commuters into slower transport modes. None of these policies effectively reduces pollution or congestion, but they reduce mobility.

Planners who think that decreasing pollution and congestion is the main objective of urban transport might logically try to fragment a large metropolitan labor market into smaller ones. For instance, some planners suggest that matching the number of jobs with the size of the working population in every neighborhood would significantly decrease trip length to the point where walking and bicycling could provide access to all the jobs in a neighborhood.

Of course, there is nothing wrong with having mixed-use neighborhoods, provided that demand from households and firms drives the land use mix. Even where planners can achieve a perfect match between the number of jobs and housing units, as in satellite towns, experience has shown that workers prefer access to wider labor markets and that there is no decrease in trip length. This has been shown in Seoul’s well-planned satellite towns.6 After an exhaustive survey of land use and trip length in California, the transport economist G. Giuliano concludes that “regulatory policies aimed at improving jobs-housing balance are thus unlikely to have any measurable impact on commuting behavior, and therefore cannot be justified as a traffic mitigation strategy.”7

Understanding why job-housing balance does not reduce trip length is easy. If it did, it would imply that at least one of the following propositions is true:

• All workers within a household only look for jobs within a short distance from their home.

• When workers change jobs, they also change homes, and moving from one home to another has a negligible transaction cost.

• Proximity to work is the only consideration when selecting a home.

Obviously, common sense shows that none of these propositions is true for the majority of households. If any of these propositions were true, then we would observe a fragmentation of labor markets and a decrease in mobility, and therefore a decrease in urban productivity.

The job-housing balance policy is, of course, not implementable in a market economy. This is because the number of jobs and the number of workers is always fluid, and no government, however authoritarian, can force people to live and work in a specific location. Even in the Soviet Union and in pre-reform China, where large state-owned enterprises provided housing for their workers, who often spent their entire career working for the same enterprise, planners could not achieve a spatial match. As I was working on housing issues in China in the 1980s and in Russia in the 1990s, I was surprised to see that, even in command economies, the utopian dream of matching jobs and housing location could not be achieved. Large enterprises had to expand in locations distant from their workers’ housing, and they had to build new workers’ residential estates in areas where they could find the land, which was not necessarily close to their factories. As soon as labor markets opened in both countries, the job-housing balance deteriorated further. A fluid labor market (which is what makes large cities so attractive) and a job-housing balance are incompatible.

However, despite these negative experiences, planners still devise land use regulations aimed at matching people with jobs. For instance, a regulation in Stockholm requires developers to match the number of jobs and the number of dwelling units in new suburban locations. Allowing mixed-use development is a good land use policy, as it allows households and firms to select locations that best meet their needs without the rigidity of arbitrary top-down land use zoning. Requiring a perfect match between population and jobs in each neighborhood in order to reduce trip length is an unattainable utopia.

Other policies also eagerly sacrifice mobility to reduce pollution and congestion. For example, several Latin American cities (e.g., Bogotá, Santiago, and Mexico City) have instituted a vehicle rationing system called “pico y plata” that restricts the circulation of vehicles on 2 days per week, depending on the last number of the vehicle’s license plate. This policy reduces mobility.8 It forces drivers either to switch to public transport or to carpool for 2 days per week. The change of transport mode is likely to require a longer commute time during the days drivers are obliged to switch. If public transport were faster, they would have used it before the restriction on driving was put in place.

Studies show that drivers circumvent “pico y plata” regulations by buying a second car with a different last number on the license plate. Traffic and congestion initially decreases after this regulation is implemented, but then increases again when the second cars join the traffic. The result is more pollution, because there are more cars on the road and because the second car bought is usually an older, more polluting model. Many studies across cities in different countries and incomes have confirmed this result. However, the regulation, which restricts mobility in order to reduce pollution and congestion, is still popular among city managers. This stance is counterproductive.

In some cities, exceptional climatic events may cause extremely dangerous pollution peaks on some days. In this case, restricting individual car use is, of course, legitimate as an emergency measure—as it is legitimate to ask factories to stop operating during the emergency—but it is not efficient to use such restrictions as permanent policy.

Accessibility and Mobility: What Is the Best Way to Measure Urban Mobility?

Transport policy should aim to increase mobility while decreasing congestion and pollution. Often, reports that claim to quantify mobility in fact only measure the cost of car congestion and pollution. For instance, the “mobility report”9 prepared by Texas A&M Transportation Institute (2012) argues that a shift from car to public transport, which indeed obviously reduces road congestion, is considered an improvement in mobility. For some reason, the reduction in the time spent commuting for the drivers who keep driving is considered a benefit, while the longer commuting times for the drivers who have shifted to public transport is not considered a cost. Mobility would increase only if the commuting time of the driving commuters who have changed to public transport becomes shorter because of the shift. However, if commuting by public transport were faster than commuting by car, drivers would have switched modes already.

Congestion clearly decreases mobility, but measuring it is not a substitute for measuring mobility. For instance, imagine a person having to walk 1 hour to work because of poverty but eventually being able to afford a collective taxi to make the same trip in 30 minutes. The collective taxi will contribute to congestion; walking did not. However, the mobility and welfare of this worker shifting from walking to a collective taxi ride would have increased. We should therefore measure and monitor the variations in mobility for different income groups.

While congestion is usually measured for car traffic only, congestion can occur at bus and Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) stops and in metro stations. While attempting to use the BRT in Mexico City in 2014, I saw three buses pass the station where I was waiting without being able to board, the buses being able to take only a few passengers among the more than 100 individuals waiting on the platform. This is also congestion, which planners should measure. Trying to shift commuters from one congested transport mode to another congested mode doesn’t decrease congestion problems. To my knowledge, the Beijing Transport Research Center is the only monitoring institution measuring daily congestion in metro stations. This institution measures the time required to board a train at peak hours.

Consequently, measuring and monitoring mobility for all modes of transport at the metropolitan level is an indispensable step for improving urban transport. A quantitative index measuring mobility improvements or setbacks is necessary to provide substance to urban transport policy. Advocating “mobility” without a way of measuring it will just add a new faddish slogan similar to “sustainability” and “livability.” Both slogans are unmeasurable and are too often used by urban planners to justify whatever policies they favor. Measuring mobility is not easy. I will describe some of the methods currently used and some that are emerging thanks to new data-recording technology.

In chapter 2, I explained why large labor markets are the raison d’être of cities. Large labor markets result in higher productivity than smaller ones. However, the size of a labor market is not necessarily equal to the number of jobs in a city. If inadequate or unaffordable transport prohibits workers from accessing all of a city’s jobs within an hour’s commute, the effective size of the labor market is only a fraction of the total number of jobs in the city. The productivity of a city is proportional to the effective size of its labor market. Mobility allows workers to have access to a measurable number of jobs within a specified travel time and can therefore be measured by the effective size of a city’s labor markets given a specific travel time.

A useful measure of urban mobility would calculate the average number of jobs that workers can commute to within, say, an hour one way. We could calculate such a mobility measurement by aggregating the number of jobs accessible in less than 1 hour from every census tract, weighted by their population. A mobility index, therefore, would have to be calculated in two stages: first, by calculating the number of jobs accessible from every census tract within a selected time limit; second, by calculating the worker-weighted average of the accessibility of all census tracts to form an index reflecting the entire metropolitan area.

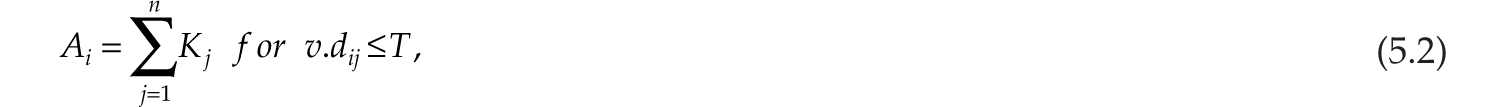

Traditionally, transport planners have measured job accessibility from different census tracts in a metropolitan area by measuring the number of jobs accessible from the census tract corrected by coefficients that reflect distance, cost, and elasticity of demand related to distance. The formulas used to measure accessibility of census tracts are usually similar to the ones I highlight in equations 5.1 and 5.2.

Equation 5.1 Job accessibility per census tract

The index of accessibility can be calculated using the equation

where Ai is the index of accessibility of census tract i, Kj is the number of jobs in census tract j, e is the base of natural logarithm, β is an elasticity coefficient, c is the unit cost of traveling the distance dij between census tract i and census tract j. While these formulas provide a way of measuring access to jobs or amenities from a specific location, the measurement they provide is an abstract index dependent on the way distances, costs and speed, and cost elasticity are calculated. Transport planners have a tendency to make accessibility measures more complex by adding more variables reflecting the complexity of commuters’ behavior. Unfortunately, this complexity renders accessibility calculations more difficult to interpret. As a result, their “black box” effect prevents their use in formulating transport policies that non specialists like mayors or city councils must approve. It is therefore indispensable to develop a much simpler accessibility index, based solely on the size of the labor market available to residents of a particular census tract based purely on travel time using existing transport modes. The advances in Geographical Information System (GIS) technology allow interactive use of maps where areas accessible within a given travel time can easily be verified, as shown by the Buenos Aires example below.

Equation 5.2 Number of jobs accessible by census tract within a set travel time

The first step in developing a mobility measurement that reflects the number of jobs accessed within a set travel time would be to change the traditional accessibility formula into the simpler and more explicit:

where Ai is the number of jobs accessible from census tract i within a commuting time lower or equal to maximum travel time T, and v is the average travel speed to cover the distance dij between tract Ai and tract Kj using the network of the mode of transport selected.

The values of v and dij are dependent on the mode of transport: public transport, bicycle, or car. Therefore, we should calculate the different value taken by Ai for each mode of transport. This accessibility index measuring the number of jobs accessed in less than a trip time T would be repeated for all census tracts in the urban area and for the major mode of transport available: public transport, cars, motorcycles, bicycles.

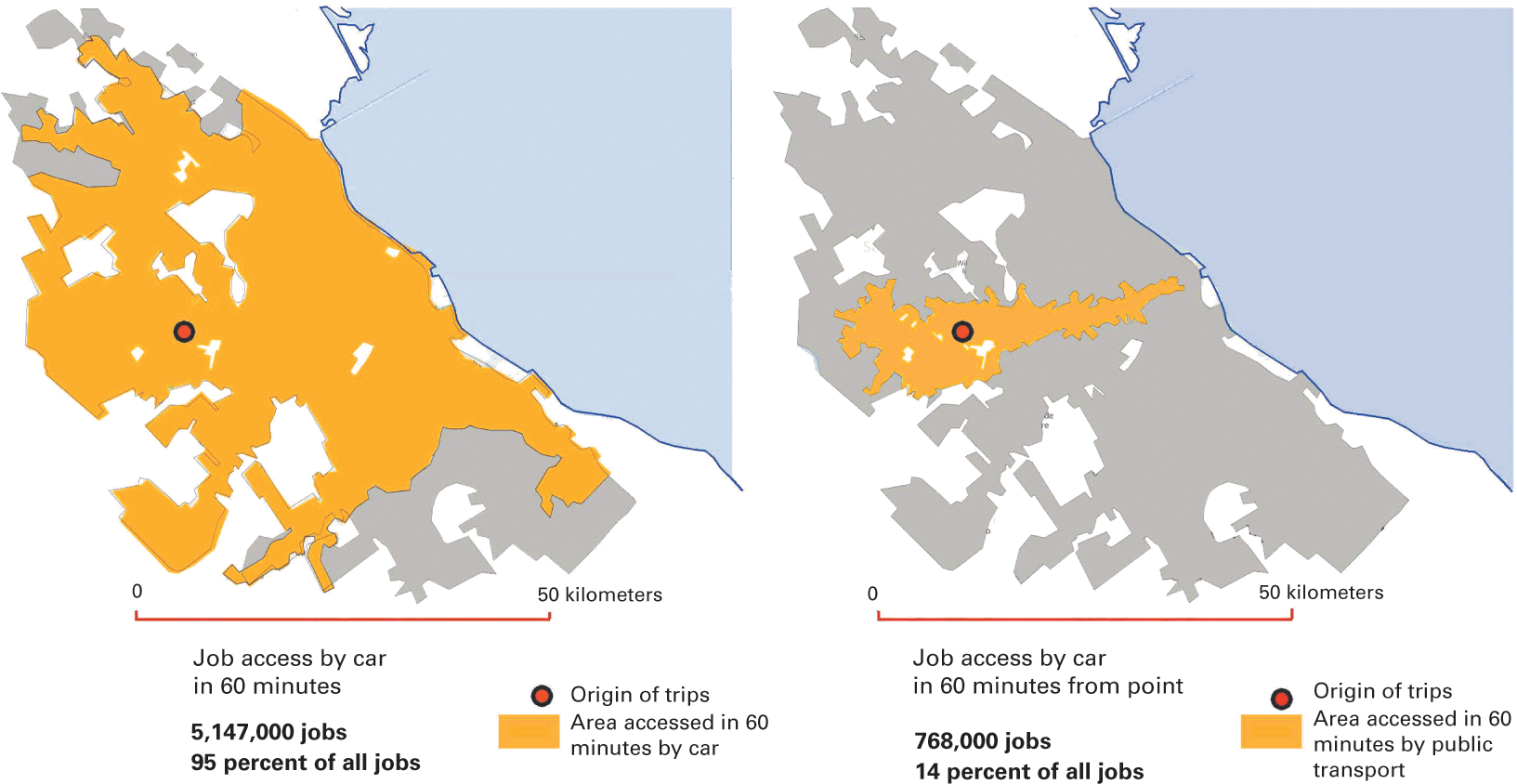

A few years ago, such calculations would have been extremely cumbersome and costly and, if performed, unlikely to be repeated for periodic monitoring. Two factors now allow for easy monitoring of an urban mobility index. First, new GIS-based technology enables the development of interactive tools accessible to any user. Second, the standardization of transport data networks (the General Transit Feed Specification, or GTFS)10 is becoming universal. This allows for the calculation of accessibility based on real transport networks and real travel times—including transfers between stations and walking times to and from stations—instead of crude “as the crow flies” distances between census tracts. In the following paragraphs, I use data extracted from research conducted by Tatiana Quirós and Shomik Mehndiratta11 for Buenos Aires.

Figure 5.2 shows the area accessible within 60 minutes by car (left) and public transport (right) from an arbitrarily selected suburban census tract (marked by a small red circle) in Buenos Aires. By overlaying the job census data with these maps, one can calculate the total number of jobs accessible in less than 60 minutes from the census tract marked by the circle. The number of jobs that can be reached in less than 60 minutes are 5.1 million jobs (95 percent of the total number of jobs in Buenos Aires) for workers commuting by individual cars and 0.7 million jobs (15 percent of the total number of jobs) for workers using public transport.12

Accessibility of a suburban location in Buenos Aires by public transport and by car. Source: Wb.BA.analyst.conveyal.com.

The difference in accessibility between the two different modes of transport is striking. However, it is not true that if every worker in Buenos Aires switched to cars, the average mobility would be increased. The commuting speed of the car users depends in large part on the number of cars on the road. An increase in car users would increase congestion and possibly cause gridlock, decreasing the speed and therefore the mobility of car users. I discuss below the necessary complementarity of various transport mode in improving mobility.

Additionally, there are two caveats for car commuting: first, the speed implied in figure 5.2 is an average speed and is not adjusted for different times of day; second, the availability of parking in different locations is not considered. In some areas, the scarcity or cost of parking might significantly decrease the practicality of commuting by car.

My purpose in showing the Buenos Aires accessibility map here is limited to providing a concrete example of the twin concepts of accessibility and mobility. The interactive map found on the website allows any Buenos Aires citizen to test its accuracy compared to their own experience. This can reduce the black box effect that habitually decreases the impact of sophisticated transport studies on urban policies.

Using this method, we could calculate a mobility index for an entire metropolitan area (equation 5.3). This global measure would be an indicator that planners should monitor regularly as a city develops.

Equation 5.3 City mobility index

After obtaining the job accessibility index of every census tract, we can calculate a city mobility index that represents the average job accessibility of all census tracts weighted by their population. The mobility index M expressed by the formula below shows the number of total jobs reachable within a commuting time T, for a given transport mode, for the average city resident,

where M is the mobility index, Ai is the number of jobs accessible from census tract i in less than T travel time, n is total number of census tracts, Pi is the active population in tract i, and P is the total active metropolitan population.

From an operational point of view, it is necessary to be able to measure mobility by location: how many jobs a worker can reach from a given location within a given time by different modes of transport. This type of data would show the most transport-deficient areas of a city. Various combined factors may explain the high unemployment rate in some urban neighborhoods. Indeed, an adequate transport system that gives easy access to jobs in the metropolitan region is often a prerequisite to decreasing local unemployment.

Measuring the Cost of Mobility

Mobility is a benefit provided by urban transport, but it has a cost. There is no point in advocating for increased mobility without also measuring the marginal cost associated with this increase. However, the economic costs of transport systems are particularly difficult to evaluate. Typically, urban commuters—whether they use public transport or individual vehicles—pay only a small fraction of the real cost of their trips.

Urban transport is different from other consumer products because its users pay only a part of its cost. Car users pay a market price for their car and the gasoline they consume (in most countries), but they are usually not paying for the public road space they use, or for the pollution, congestion, and other costs they have imposed on others. Users of publicly operated transport pay a fare that represents only a small part of the system’s operational and maintenance costs and usually pay nothing for the capital cost of the system. Obviously, car owners and public transport users eventually pay collectively all these costs through their taxes, but the cost they pay is not related to the quantity of the service they use. Because of the lack of real pricing, we can expect urban transport to be overused and undersupplied. Because of our inability to recover the cost of trips, mobility is significantly less than it could be. Therefore urban productivity could be greatly increased if we could price urban trips at their real costs.

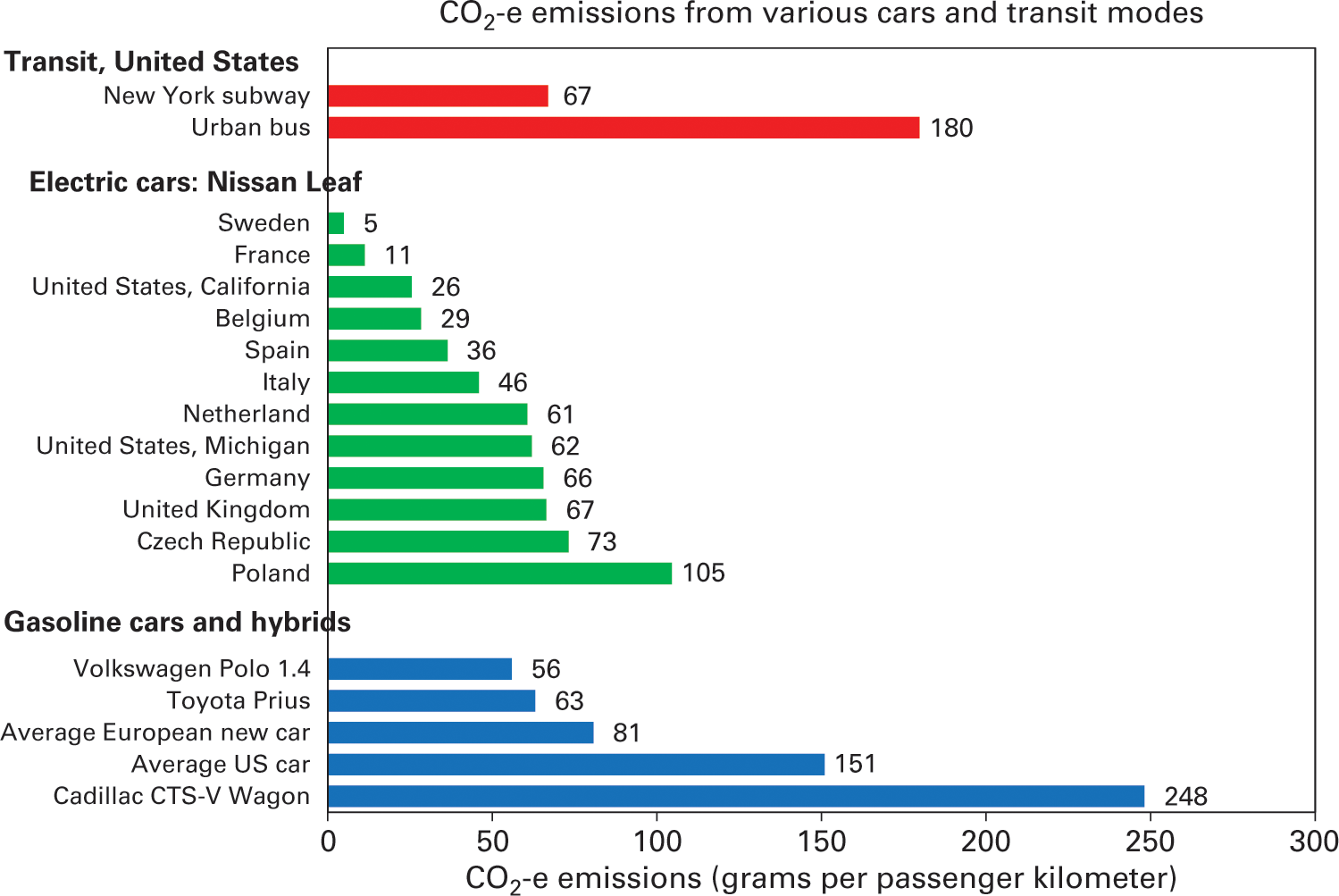

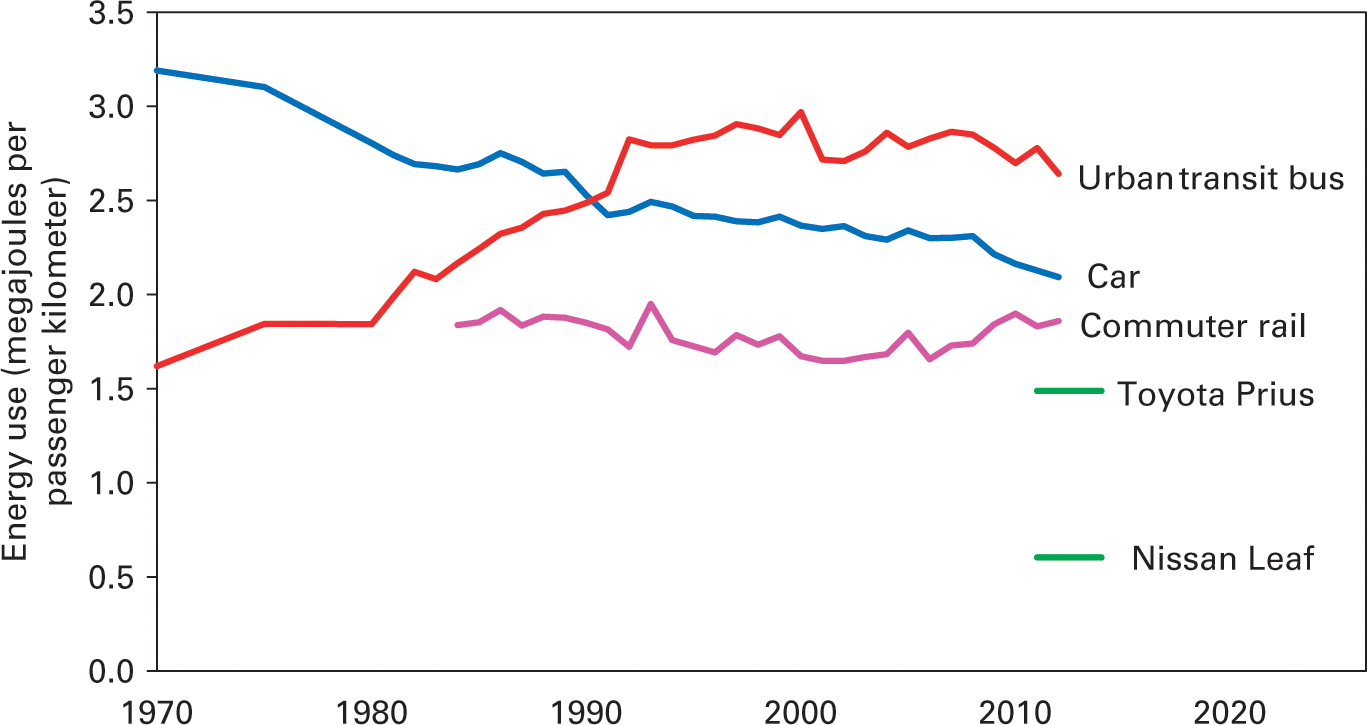

Evaluating these costs is difficult, as many subsidies are not transparent. In addition, the cost of what economists call “negative externalities” (i.e., the cost imposed on others, like congestion and pollution) is not easy to evaluate. Since the 1980s, it has become clear that we should add the cost of global warming to the other traditional externalities. A worldwide price for carbon emission should reflect the cost of global warming caused by greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. However, because of the worldwide failure to price carbon, pricing different modes of transport and comparing their price to their performance is even more difficult.

Faced with the difficulty in calculating the real cost of trips, many transport policy advocates renounce any attempt to make even an approximate calculation and just append the word “sustainable” to the mode of transport they favor. When comparing the cost and benefits of different modes of transportation, I will differentiate the transport costs that have a clear cash value (e.g., the cost of a car or of a subway ticket) from those like pollution or GHG emissions, which I will evaluate in units of gas emitted per vehicle/km or passenger/km without attempting to price it. In the same way, I will not attempt to give a cash value to the time spent commuting, but will just provide the average speed or time traveled. Transport economists attribute a dollar value to the time spent commuting based on the opportunity cost of the time of the person traveling. Using this convention, the cost of an hour of travel by a worker earning the minimum wage is lower than the cost of the same hour of travel by an executive paid a multiple of the minimum wage. Although this type of calculation is legitimate to calculate the aggregate economic cost of urban transport, it does not necessarily reflect how individuals select their choice of travel mode. Besides, the social cost of long commutes for low-income workers might be much higher than the one reflected by their hourly salary.

Mobility and Transport Modes

Classification of Urban Transport Modes

Until the middle of the Industrial Revolution—about 1860—walking was the dominant mode of urban transport. The area that workers could reach by walking less than an hour severely limited the expansion of cities. Because of the limitation on the speed of transport, urban labor markets grew primarily through the densification of the existing built-up area. Metropolitan Paris in 1800, before the Industrial Revolution,13 had a density evaluated by Angel at about 500 people per hectare compared to about 55 today. Since then, many mechanized modes of urban transport have allowed cities to grow geographically, densities to decrease, and labor markets to expand. These larger labor markets, in turn, allowed more labor specialization, which has increased the productivity of cities. Faster and better-performing urban transport modes are therefore a crucial element in the growth and prosperity of cities. In addition to increasing the size of the labor market, faster and more flexible transport modes allow urban land supply to expand and respond quickly to growing demand for new and better housing and new commercial areas.

Since the Industrial Revolution, many mechanical urban transport modes have been added to walking, among them cars, bicycles, motorcycles, buses, subways, tramways, and BRTs. Governments had an important role in allowing or funding the different modes of transport that were becoming available as technology changed.

The modes of urban mechanized transport that were already available at the beginning of the twentieth century have not changed much since then. The efficiency in using energy and the speed of cars, buses, and metros have certainly improved, but no new mode of urban transport has emerged. The invention of the BRT system in Curitiba, Brazil, in 1974 is only the application to buses of a technology applied to tramways at the end of the nineteenth century. However, it is quite possible that during the next 20 years, we will see the emergence of completely new modes of transport. The possibilities presented by the combination of vehicle sharing and autonomous vehicles could completely revolutionize urban transport as we know it today.

While no new mode of urban transport has emerged during the past 100 years, the dominant mode is often changing rapidly in emerging economies. The changes in mode reflect changes in income, city size, and the geographic coverage of public transport systems. Changes in dominant transport modes are instructive, as they reflect users’ choices and the way they adapt to the performance—speed, cost, and spatial coverage—of the various modes of transport available.

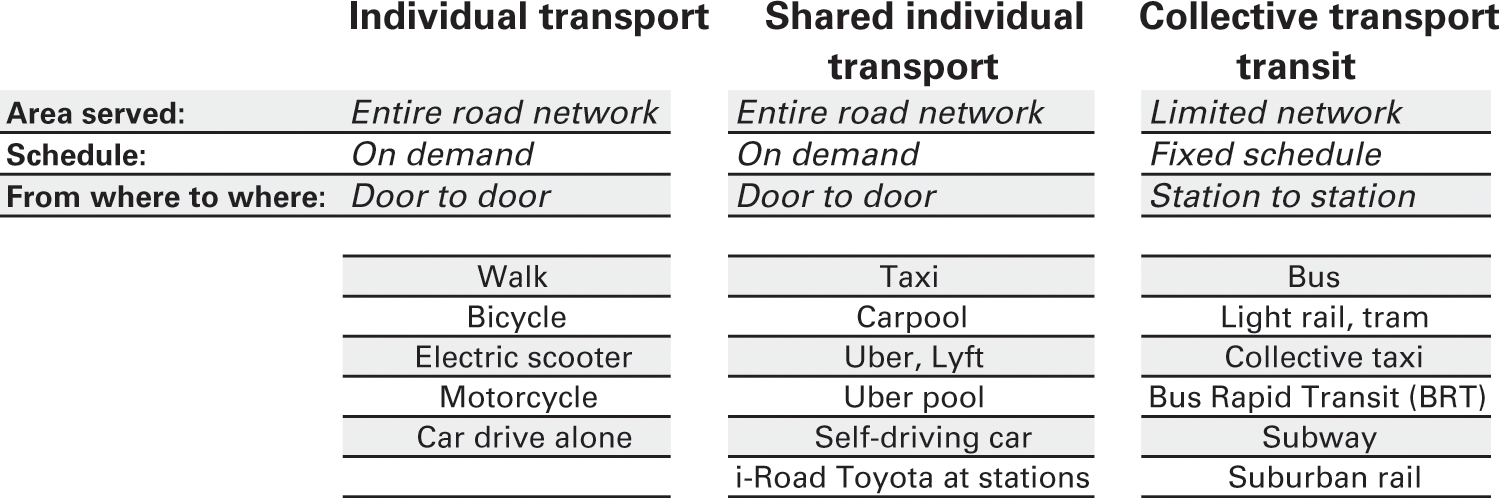

Individual Modes of Transport versus Public Transport

In a typical medium- or high-income city, commuters choose between a number of transport modes: walking, bicycling, driving, riding in a taxi, or using public transport. They select the mode of transport—or combination of modes—that is the most convenient for their trip, taking into account time of travel, direct cost, comfort, and whether their trip has to be chained with several activities (e.g., working, picking up children at school, shopping). When selecting their means of transport, travelers do not take into account the cost of the negative externalities they create—pollution, global warming, noise, and congestion.

Modes of transport are highly diverse, but they can be conveniently divided into three categories: individual transport, shared individual transport, and collective transport or public transport (figure 5.3). Individual transport and shared individual transport give access to the entire road network, while the various public transport modes are restricted to a network, which by necessity is a fraction of the entire road network. Because individual transport modes use the entire road network, they provide door-to-door travel without the need to change modes of transport on the way. Additionally, individual transport provides continuous 24/7 service, while public transport services are restricted to preset schedules with low frequencies outside peak hours.

Modes of urban transport.

Individual motorized modes of urban transport present many advantages over public transport, especially on-demand door-to-door service. Given these advantages over public transport, why did private firms and then the government provide public transport services?

Complementarity of Various Modes of Transport

In many cities, most modes of transport listed in figure 5.3 coexist. Some modes are heavily dominant, like the motorcycle in Hanoi, which represents 80 percent of commuting trips, or the car in US metropolitan areas (86 percent of all trips). However, in most cities, several transport modes coexist, and their relative share of total commuting trips varies with time. These variations reflect consumers’ choices, which respond to changing conditions in household income, urban structure, or transport mode performance.

Dominant Modes of Urban Transport May Change Rapidly

The shift in dominant modes of transport reflects an increase in population and household income. The share of passengers by transport mode reflects commuters’ preferences but also government action. This supply and demand tends to change rapidly in cities whose economies are growing fast; less so in cities where population and income are more stable. Figures 5.4 and 5.5 illustrate the rapid evolution of dominant modes of transport in cities like Beijing, Hanoi, and Mexico City compared to the relative stability found in Paris.

Changes in the dominant transport mode, Beijing (left) and Hanoi (right). Source: Beijing Transport Research Center, 2015.

Changes in the dominant transport mode, Mexico City (left) and Paris (right). Sources: Mexico City: “Gradual Takeover of Public Mass-Transit by Colectivos, 1986–2000,” Secretaria de Transito y Viabilidad (SETRAVI) Embarq—World Resources Institute; Paris: Syndicat des Transports d’Île-de-France website, www

Beijing’s transport mode underwent a radical change between 1986 and 2014. The bicycle was the main mode of transport in 1986, although the city population was already above 5 million. Many bicycle and public transport users shifted to private cars in the late 1990s. The shift from bicycle and public transport to car trips between 1994 and 2000 corresponds with the rapid increase in household income during this period of about 47 percent. It was certainly not driven by government policy. The massive investment in public transport—the tenfold increase in the distance covered by subway lines from 53 kilometers in 1990 to 527 kilometers in 2014—reversed the decline in public transport’s share of commuting trips. Car traffic congestion combined with a quota system for buying new cars stabilized the growth of car trips. Meanwhile, the share of bicycle users kept decreasing.

Hanoi’s transport transformation has been even more dramatic than Beijing’s. From 1995 to 2008, the share of bicycle trips dropped from 75 percent to barely 4 percent! But unlike Beijing, the motorcycle became the only dominant mode of transport in Hanoi, accounting for 80 percent of all trips (cars and public transport together account for only about 15 percent). As in Beijing, Hanoi’s commuters reacted to changing local conditions. Increased income allowed them to replace bicycles with motorcycles, significantly lowering commuting time—the average commuting time in Hanoi was 18 minutes in 2010. Large areas of Hanoi are accessible through narrow, winding roads that are nearly inaccessible to cars and even less accessible to buses, which were the only means of public transport in 2014. Motorcycles also gave easy access to residents of suburban former villages with only rural unpaved road access, expanding the supply of housing affordable to low-income migrants.

In Mexico City between 1986 and 2007, commuters have dramatically reduced their use of public transport in favor of minibuses and private cars despite strong municipal governmental policies to discourage these private alternatives. The change in dominant mode reflects rising incomes but also a change in the city structure of Mexico. Jobs have dispersed to suburban areas, in part due to government land use restrictions in the Federal District, and traditional public transport networks are less efficient for commuting from suburb to suburb. When jobs are dispersed, minibuses and cars become more convenient. However, the congestion created by cars and minibuses considerably slows down traffic in a city as dense as Mexico City (average density is about 100 people per hectare in the metropolitan area).

In contrast with these three cities, metropolitan Paris between 1976 and 2010 (shown on the right if figure 5.5) does not show any large shift in transport mode. Paris’s population and household income have been much more stable than those of Beijing, Hanoi, or Mexico City. The relative share of car and public transport trips reflects the structure of the city: a very dense core of about 2 million people and suburbs of 8 million. Commuters use public transport for most trips within and toward the core, but they use cars for the roughly 70 percent of commuting trips that originate and end in suburbs (reflecting the same share of job distribution). The extension of fast trains in the far suburbs of Paris has somewhat increased the share of public transport since the mid-1990s. However, car travel remains the dominant mode, reflecting the spatial structure of the city with a majority of population and jobs located in suburbs and, as a consequence, trips originating and ending in suburbs.

The change in transport mode in Beijing and Paris shows that increasing the size of the public transport network impacts commuters’ transport mode preferences. However, household income and a city’s spatial structure are the main determinants of commuter choice. For instance, in Beijing, multiplying the length of subway lines tenfold between 1990 and 2014 has only increased the share of public transport trips by 12 percent. And while Hanoi is building a new subway system that could eventually increase the very low share of public transport, subway trips are unlikely to compete with the speed and spatial coverage provided by the motorcycle.

The existence of various modes of transport reflects the choice of commuters. Commuters choose transport modes based on where they live, where they work, what time they go to work, what time they return home, and what share of their income they are willing to allocate to transport. No transport mode is perfect. Unsurprisingly, residents are often dissatisfied by urban transport. Car commuters complain about congestion and pollution, while public transport users complain about crowding, schedule irregularity, and lack of geographic coverage. In the following sections, I will analyze the pros and cons of the various transport modes accounting for their speed and the various negative externalities they create: congestion, pollution, and GHG emissions. However, we must remember that in the end, the primary objective is to increase mobility while decreasing the negative externalities imposed by that mobility.

Travel Time, Speed, and Travel Mode

The Measure of Travel Time to Work (Commuting)

As already mentioned, average commuting travel time is a common proxy used for measuring mobility. Average travel time becomes a meaningful proxy for mobility if it only includes trips to work and excludes other types of trips when calculating the average. Obviously, an average between travel time to work and travel time to go shopping or to the barbershop would have no meaning as a proxy measure for mobility.

The measurement of commuting travel time should be “door-to-door.” Travel time should include the time of travel from the moment the commuter leaves home to the moment she reaches her workplace. In addition, commuting time should be disaggregated by transport mode.

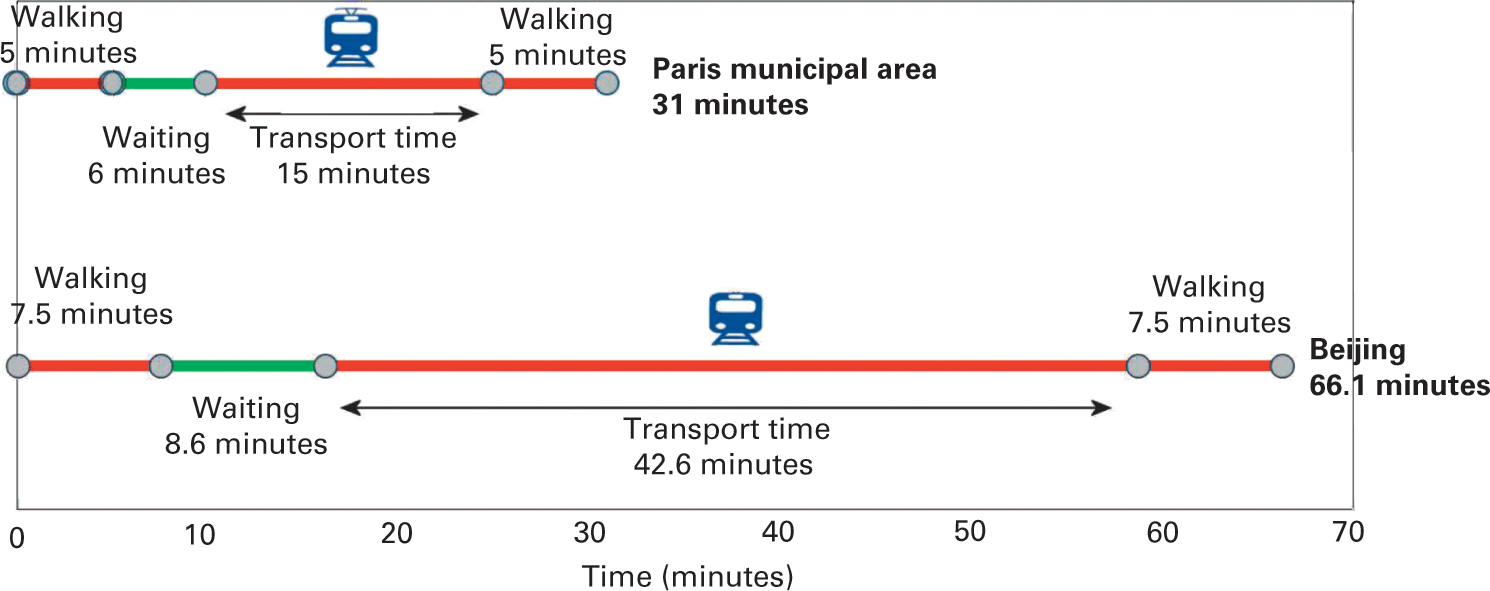

The examples of average public transport commuting time in the municipality of Paris and in Beijing’s metropolitan area illustrate the importance of door-to-door time measurement when assessing mobility (figure 5.6). The average door-to-door commuting time for trips using the subway in Paris municipality is 31 minutes, but the actual time spent on the train is only 15 minutes. The time required to go to the station and board the train, and then to walk from the station to the workplace, represents 52 percent of the door-to-door commuting time. For the longer trips in Beijing’s metropolitan area, the proportion of “access time” is lower and represents 36 percent of total commuting time.

Average door-to-door public transport travel time for commuters in the Paris municipality and Beijing metropolitan area. Sources: Data for Paris: “Etude sur les deplacements,” Regie Autonome des Transports Parisiens, 2014; Beijing: “Beijing, the 4th Comprehensive Transport Survey Summary Report,” Beijing Transportation Research Center (BTRC), Beijing Municipal Commission of Transport, Beijing, China, 2012.

We should do the same door-to-door calculation for car commuting trips, which typically start from one’s driveway in a suburban home but may end in a parking lot or underground garage, involving a sizable amount of walking time to get to the work place. I could not find statistics disaggregating travel time for car travel that include walking to and from a parking place. My own weekly car commuting from Glen Rock, New Jersey, to New York University in Greenwich Village in Manhattan takes on average 55 minutes of driving time and requires an additional 7.5 minutes walking from an underground parking garage to the university (figure 5.7). Access time is then only 12 percent of total commuting time.

Door-to-door commuting time from suburb to downtown New York (case study, no statistical significance).

Because the access time to transport is usually high, the speed of various modes of transport is a poor indicator of door-to-door commuting time. When trying to increase mobility, reducing access time to various modes of transport is as important as increasing the speed of the motorized part of transport. Table 5.1 shows the ratio between door-to-door speed and vehicle speed for Paris, Beijing, and the New York case study. As a city size increases, public transport networks become more complex and less dense, and they often require transfers between modes (e.g., buses to suburban trains). The increasing distance from home to stations and the necessity of transfers tend to increase access time. Car trips are less vulnerable to long access times, if an allocated parking lot exists at the destination. Trips by car from suburb to suburb have very little access time, because usually parking is available very close to the trip origin and destination. The lower value of suburban land explains why this availability is taken for granted.

|

Ratio between door-to-door speed and transport vehicle speed. |

||||||

|

Commuting mode |

Paris |

Beijing |

New York |

|||

|

Subway |

Bus and subway |

Car |

||||

|

Total average commuting distance (kilometers) |

9 |

19 |

38 |

|||

|

Door-to-door trip time (minutes) |

31 |

66 |

63 |

|||

|

Transport vehicle speed (km/h)a |

33 |

25 |

40 |

|||

|

Door-to-door speed (km/h) |

17 |

17 |

36 |

|||

|

Ratio of door-to-door speed to vehicle speed (percent) |

53 |

68 |

89 |

|||

|

a. For Beijing, this is an average speed for bus and subway. |

||||||

In the examples above, commuters in Paris and Beijing were walking to access the main motorized transport mode, but, of course, many other means of transport could be combined in a single commuting trip. A commuting case study in Gauteng, South Africa, describes one of the most complex and long commuting trips I have ever heard of.14 A single mother of four children commutes every weekday from her home in Tembisa, a township in Gauteng’s metropolitan area (which includes Johannesburg and Pretoria), to Brummeria, a business district of Pretoria, where she cleans offices. She leaves home at 5:00 A.M. to be at the office at 7:30 A.M. She starts her commute with a 2-kilometer walk to a collective taxi stand, where a taxi takes her to a train station. The train brings her to Pretoria, where she takes another collective taxi to a stop in Brummeria, from which she walks to her workplace (figure 5.8). The entire commute one way takes 2.5 hours, including walking and waiting for taxis and the train. Her commuting distance is 47 kilometers. Her average commuting speed is about 18 km/h, although most of the distance she covers is on a commuter train going at an average speed of 46 km/h. Because of the need to connect to the rail network to avoid the higher cost of the collective taxi, the distance she travels (47 kilometers) is much longer than the shorter road distance of 29 kilometers between her home and her workplace. If she had access to a motorcycle or even to a moped, she could commute in about 1 hour, instead of 2.5 hours. Access to a moped would allow her to gain 3 hours a day of disposable time!

Extreme commuting in Gauteng (South Africa) case study. Source: “National Development Plan Vision 2030,” President’s National Planning Commission, South Africa, 2011.

For a given home and job location, commuting time may show large variations depending on the main mode of transport, the number of transfers, and access time. In the case described here, a moped with a speed of 30 km/h would result in much higher mobility than using a suburban train with an average speed of 46 km/h.

Average Commuting Time by Transport Mode

Commuting by public transport takes longer on average than commuting by individual car. Given the amount of urban congestion plaguing most large cities in the world, this seems surprising. Urban congestion affects public buses as much as it does individual cars, but we would expect that public transport trips would be shorter in cities where many commuters are using underground public transport and dedicated bus lanes. Unfortunately, this is not the case. In a comprehensive and authoritative book,15 Robert Cervero, a fervent advocate of urban public transport, admits that faster travel time by car, even in public transport-based European and Japanese cities, is the main challenge in increasing the share of public transport over car trips all over the world. Let us try to understand why that is the case by looking at a sample of specific cities.

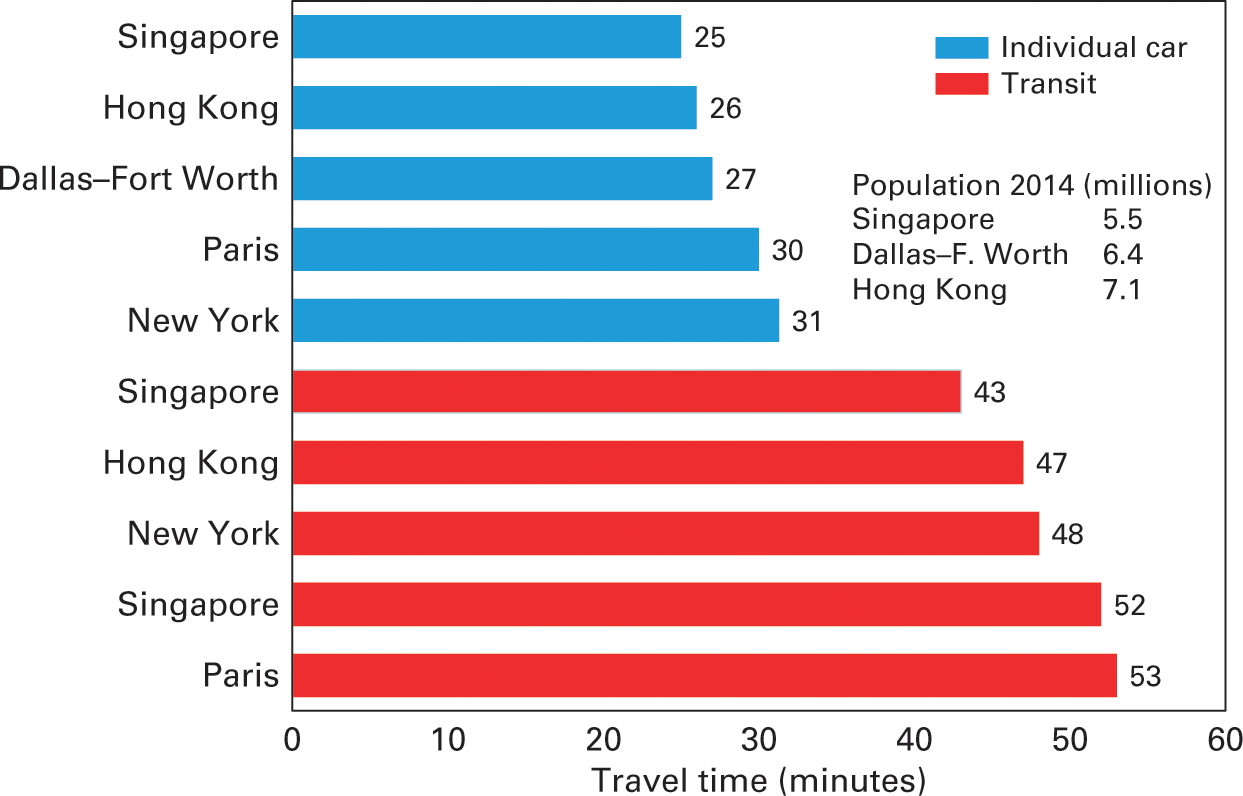

Commuting time in five large cities—Dallas–Fort Worth, Hong Kong, New York, Paris, and Singapore (figure 5.9)—confirms Cervero’s observation: commuting travel time by car is significantly shorter than by public transport in all these cities. The increase in travel time between public transport and car commuting ranges from 53 percent for New York to 100 percent in Singapore.

Average commuting travel time by transport mode, Singapore, Hong Kong, Dallas–Fort Worth, Paris, and New York. Sources: Data for United States: “Commuting in America 2013,” US DOT Census Transportation Planning Products Program, Washington, DC, 2013; Paris: “Les deplacements des Franciliens en 2001–2002,” Direction régionale de l’équipement d’Île-de-France, Paris, 2004; Hong Kong: “Travel Characteristics Survey-Final Report 2011,” Transport Department, Government of Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, Hong Kong, 2011; Singapore: “Singapore Land Transport Statistics in Brief 2010,” Land Transport Authority, Singapore Government, Singapore, 2010.

These differences measure average travel times for trips that have many different origins and destinations. The averages may mask a number of trips where the ratio between public transport and car travel time is reversed (i.e., trips that are shorter using public transport than using cars). For instance, some trips in Manhattan or in Paris Municipality are most certainly faster by public transport than by car. Suburban trips for people who live very close to a station and whose workplace is also close to a station might also be shorter using public transport than using a car. We can be confident that when this is the case, commuters choose the faster means of transport. However, average commuting time shows that in all these cities, commuters using cars spend less time commuting than those using public transport. Let us try to find out why it is so.

I did not randomly select the five cities in figure 5.9. Their characteristics are shown in table 5.2. Four of the selected cities have a significant share of public transport use, ranging from 26 percent for New York to 88 percent for Hong Kong. The fifth city, Dallas–Fort Worth, is an outlier with less than 2 percent of commuting trips using public transport. Hong Kong’s and Singapore’s public transport systems are relatively recent, and they benefit from their modernity and are known for their efficiency. The five cities selected show a large variety of densities. Hong Kong and Singapore have high densities, while New York and Paris have medium densities but high job and population densities in their core area, which favors public transport use and makes car use more difficult. Dallas–Fort Worth is the only city in the sample with a very low density (12 people per hectare) but with a population of 6.2 million, about equivalent to Hong Kong’s 6.8 million (2011). Given the very low density of Dallas–Fort Worth, car usage is predictably very high at 98 percent of commuting trips.

|

Density and share of public transport trips in five sample cities. |

||||||||

City |

Population (millions) |

Transit share of commuting trips (percent) |

Density (people per hectare) |

Built-up area (square kilometers) |

||||

|

Dallas–Fort Worth |

6.20 |

2 |

12 |

5,167 |

||||

|

New York Metropolitan Statistical Area |

20.30 |

26 |

18 |

11,278 |

||||

|

Paris (Ile De France) |

11.80 |

34 |

41 |

2,878 |

||||

|

Singapore |

5.60 |

52 |

109 |

514 |

||||

|

Hong Kong |

6.80 |

88 |

264 |

258 |

||||

|

Sources: Population: Census 2010. Density and built-up area: author’s measurements. Transit: Dallas–Fort Worth and New York, Summary of Travel Trends, 2009, National Household Travel Survey, U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration, Washington, DC; Paris, E 2008 Enquête Nationale Transports et Déplacements, Table 5.1. Commissariat général au Développement durable, Paris 2008; Singapore, Land Transport Authority Singapore Land Transport, Statistics in Brief 2010, Singapore Government, 2010; Hong Kong, “Travel Characteristics Survey-Final Report 2011,” Transport Department, Government of Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, Hong Kong, 2011. |

||||||||

However, one should not conclude that because current car trips are usually faster than public transport trips, a shift of public transport trip toward cars would decrease the average commuting time and therefore increase mobility. In the four cities with medium and high densities mentioned above, the current speed of cars depends on the proportion of commuters using public transport. Indeed, in Singapore, the government periodically adjusts the cost of using a car to decrease demand for car trips with the explicit goal of maintaining a minimum speed of car travel for those who can afford it. Most cities where public transport is an important mode of transport also try to control demand for car use, although in a manner less explicit and muscular than in Singapore. Reducing demand for car trips takes many forms. For instance, New York increases tolls for cars in bridges and tunnels, Paris reduces the number of car lanes, and Hong Kong increases taxes on car purchases. Beijing establishes yearly quotas for the purchase of new cars and uses a lottery to determine who may purchase a car. Stockholm, London, and Rome have a special charge to discourage car traffic in the core city. All cities heavily subsidize public transport operation cost to convince commuters to shift from cars to public transport because of the cost difference.

The higher speed of commuting cars in dense and moderately dense cities is due to the high number of trips using public transport. In these cities, the two modes, car and public transport, complement each other. In Dallas, by contrast, the short commuting time is entirely due to low density. As I will show later, low suburban densities provide larger road areas per households than in high-density cities. This large area of road per person allows higher speeds. As I mentioned at the beginning of this chapter, compact dense cities like Hong Kong and Singapore, while decreasing the average commuting distance, are often associated with a much longer commute than very-low-density cities like Dallas–Fort Worth. The potential advantages of shorter commuting trips in high-density cities are entirely offset by the slower speed caused by congestion, including congestion in transit.

Travel Cost

As mentioned above, I drive once a week from Glen Rock in suburban New Jersey to New York University in south Manhattan. The trip length one way is 37 kilometers. The cost of tolls amounts to $14, plus $17 for parking (of which 18.4 percent is a special municipal tax on parking), plus another $5 for about 2 gallons of gasoline, for a total of $36 for a return commuting trip by car (not counting insurance, maintenance, and capital cost). The commuting time door-to-door, one way, is about 63 minutes on average, corresponding to an average speed of 35 km/h.

The same return trip using public transport (bus plus metro) would cost only $14 but would require 102 minutes door-to-door one way, or an average speed of 22 km/h. In addition, outside peak hours, buses to and from Glen Rock leave only every hour. On a two-way commuting trip driving my car, I am spending an additional $22 to gain 78 minutes over public transport travel time, implying an opportunity cost of my time about $17 per hour. This personal case study has no statistical value, but it does explain the way many commuters select their transport mode. The transport costs that I pay for both public transport and car commuting do not reflect the real cost of providing the transport service that I am using—whether car or public transport. The fare of most public transport trips covers only a fraction of operating cost, and usually no capital cost at all. In the same way, tolls and gasoline costs may not reflect all the maintenance cost of the roads and traffic management service I use during my trip, and even less of the negative externalities on the environment and the congestion I impose on others by using my car.

So far, if we look only at the speed and duration of commuting trips, it seems that car trips have an advantage over public transport. Indeed, as jobs tend to disperse into suburbs and household income increases in many large cities of the world, it seems that the ratio of car trips over public transport trips is also increasing, to the alarm of transport planners. The congestion created by cars is a major concern. I alluded to this problem by warning that in denser parts of cities, the shorter commuting time made possible by traveling by car depended on the number of commuters using public transport. The larger the number of commuters using public transport, the higher the speed of commuters using cars will be. This trend explains the popular support for public transport investments in cities like Atlanta, where most commuters are using cars and intend to keep using cars in the future.

Speed, Congestion, and Mode of Transport

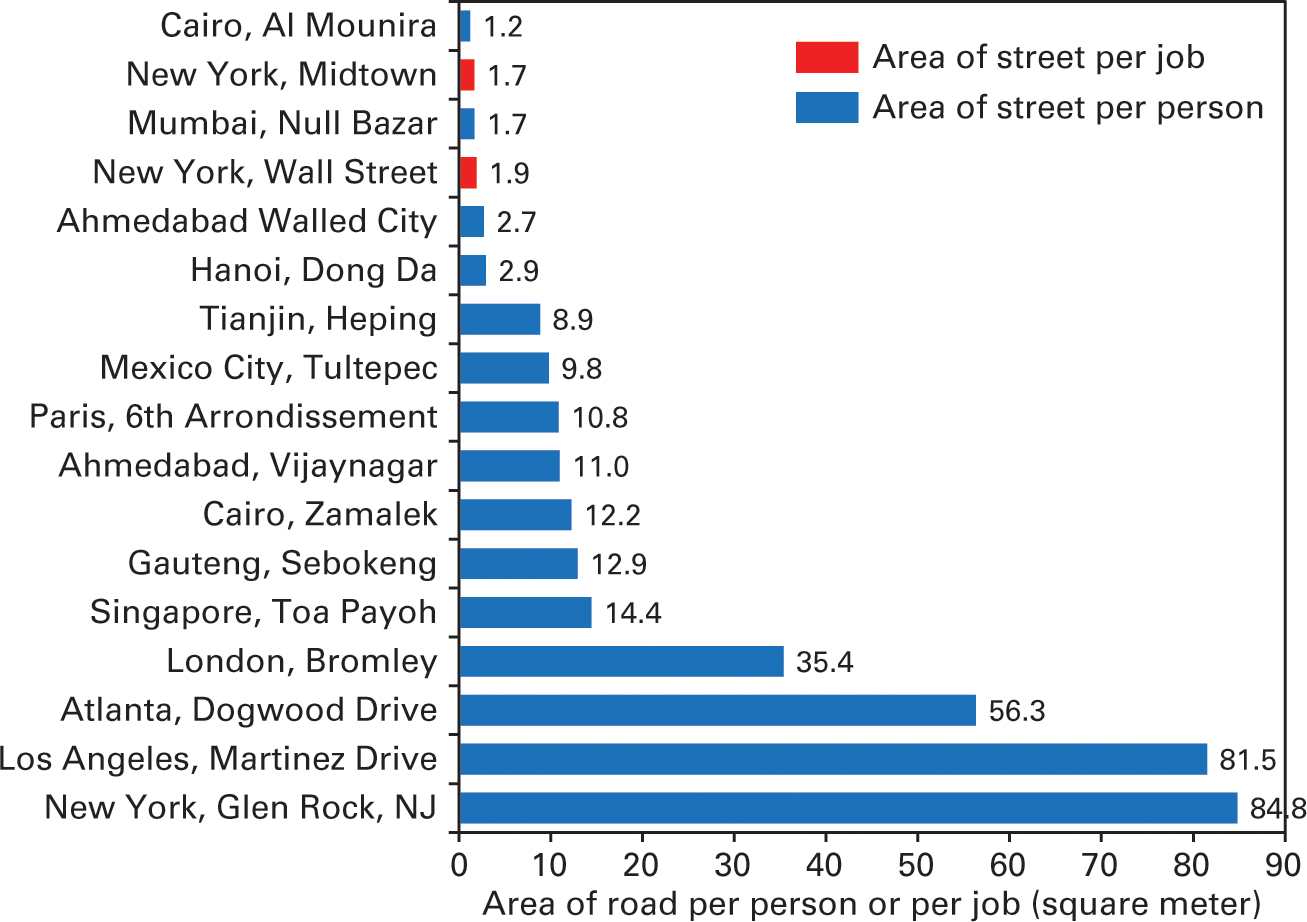

Road congestion is a real estate problem. Through regulations, planners or developers allocate portions of urban land to streets when the land is originally developed. Once a neighborhood is fully built, increasing the area allocated to streets is extremely costly financially and socially, as it requires decreasing the land allocated to uses that produce urban rents while increasing the area of street that produces no rents. It also requires the relocation of households and businesses.

In most cases, cars, buses, and trucks do not pay for the street space they consume; they have, therefore, no incentive to reduce their land consumption. The mismatch between the supply of land allocated to streets and the demand for street space creates congestion—too many users for too little street space.

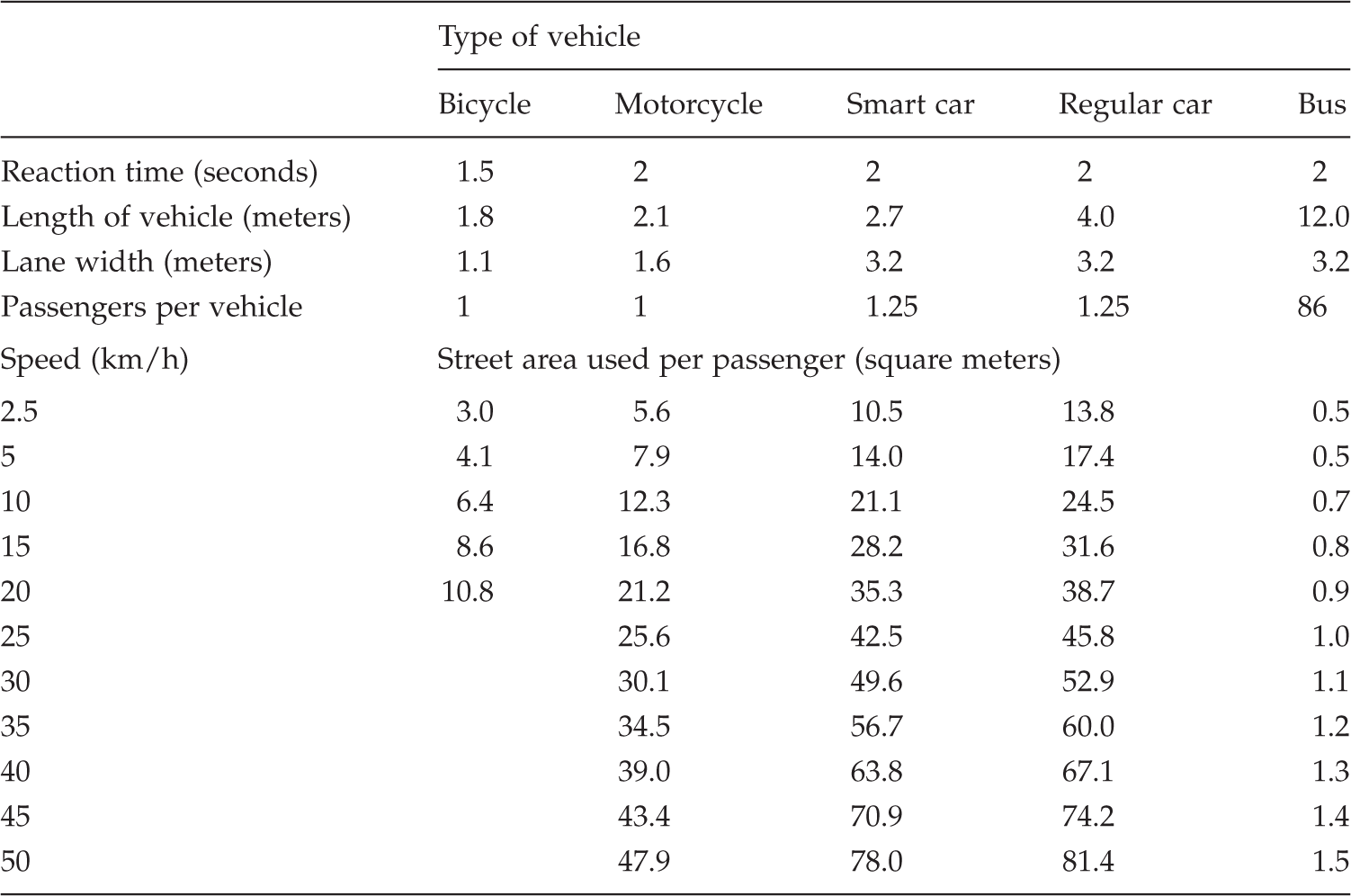

Congestion decreases travel speed and therefore decreases mobility. In our quest to increase mobility, it is important to measure the street area consumed per passenger for each mode of urban transport and eventually to price it so that users who use large road areas would pay a higher price than those who use small road areas. Being able to price congestion in term of real estate rental value would enable us to increase mobility, not so much by increasing supply as by decreasing consumption. The objective remains to increase mobility by pricing congestion, not to select or “encourage” a preferred mode of transport.

In the next sections, I describe how to measure congestion and various attempts to increase road supply to manage demand.

Measuring Congestion

Congestion is the expression of a mismatch between supply and demand for street space. Traffic engineers define a road as congested when the speed of travel is lower than the free flow speed. The free flow speed of vehicles establishes the noncongestion speed, which traffic engineers use as a benchmark to measure congestion.16 Any speed below the free flow speed is indicative of congestion and is measured by the travel time index (TTI), which is the ratio of travel time in peak periods to travel time in free flow conditions. For instance, a car driving at 15 km/h on Fifth Avenue in New York at peak hours would indicate a TTI of 2.8, if we assume that the free flow speed in New York is equal to the maximum regulatory speed limit of 40 km/h. The mobility report published by Texas A&M Transportation Institute in 2012 evaluates the urban average TTI in 498 US urban areas at 1.18. Los Angeles, with 1.37, has the highest TTI among US cities. New York’s TTI is slightly lower at 1.33. The use of TTI allows us to measure the number of additional hours spent driving compared to what they would have been at free flow speed, and by extrapolation, the additional gasoline spent. From TTI, it is then possible to calculate the direct cost of congestion: the opportunity cost of the driver time plus the additional cost of gasoline compared to what it would have been under free flow conditions.

Using TTI to measure congestion is convenient, but is, of course, arbitrary. Starting November 1, 2014, New York City reduced its speed limit from 30 miles per hour (48 km/h) to 25 (40 km/h). The new regulatory limit is bound to reduce the free flow speed. If we take the new regulatory speed of 40 km/h as the free flow speed, then the TTI for a car running at 15 km/h has consequently decreased from 3.2 to 2.8 between October 31 and November 1. The reduction of the New York speed limit, aimed at reducing fatal car accidents involving pedestrians, obviously did not result in a reduction of average commuting time; it has even probably slightly increased it, in spite of the decrease in TTI implying the opposite. In the case of New York, the decrease in TTI in the fall of 2014 will be a false positive!

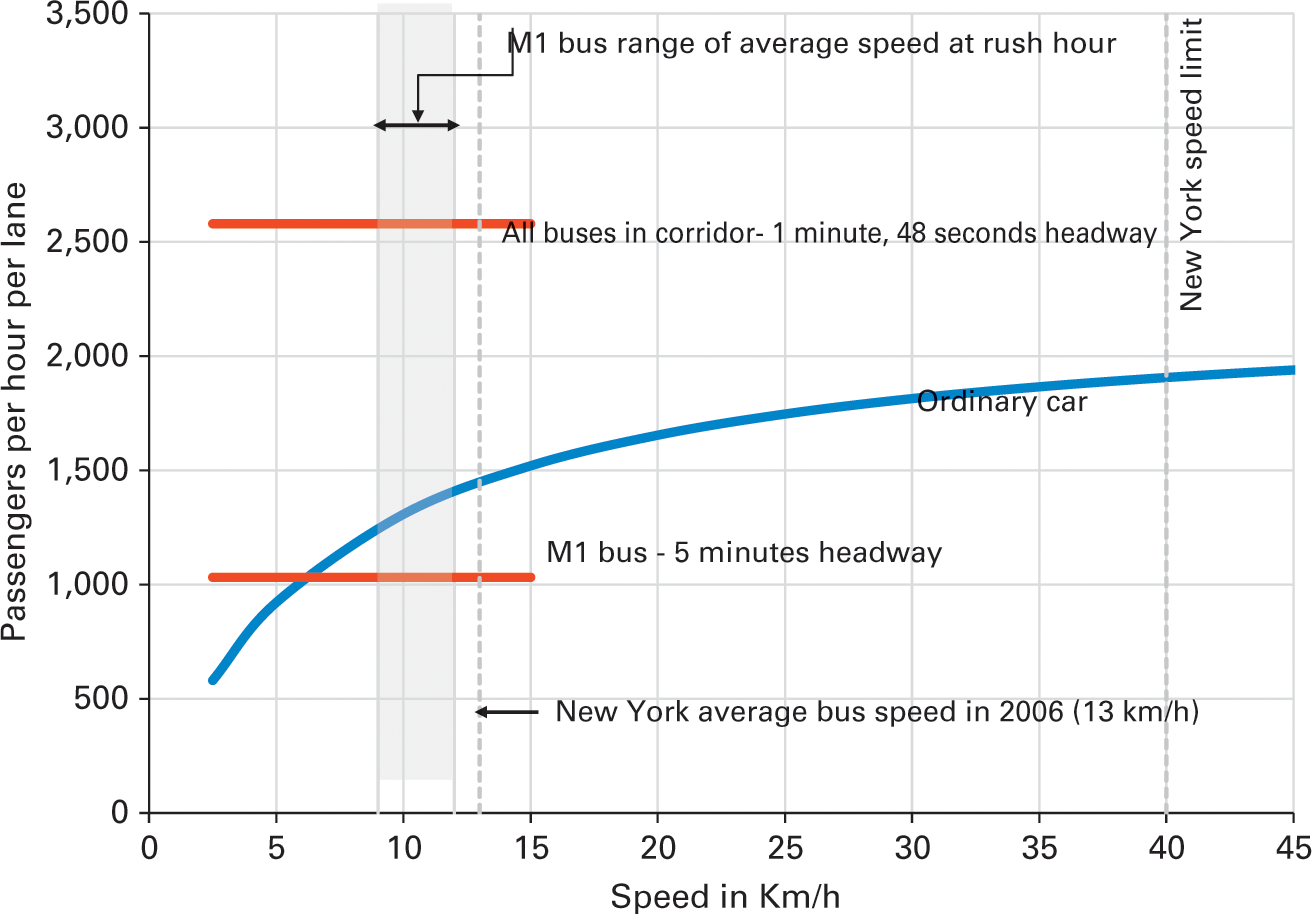

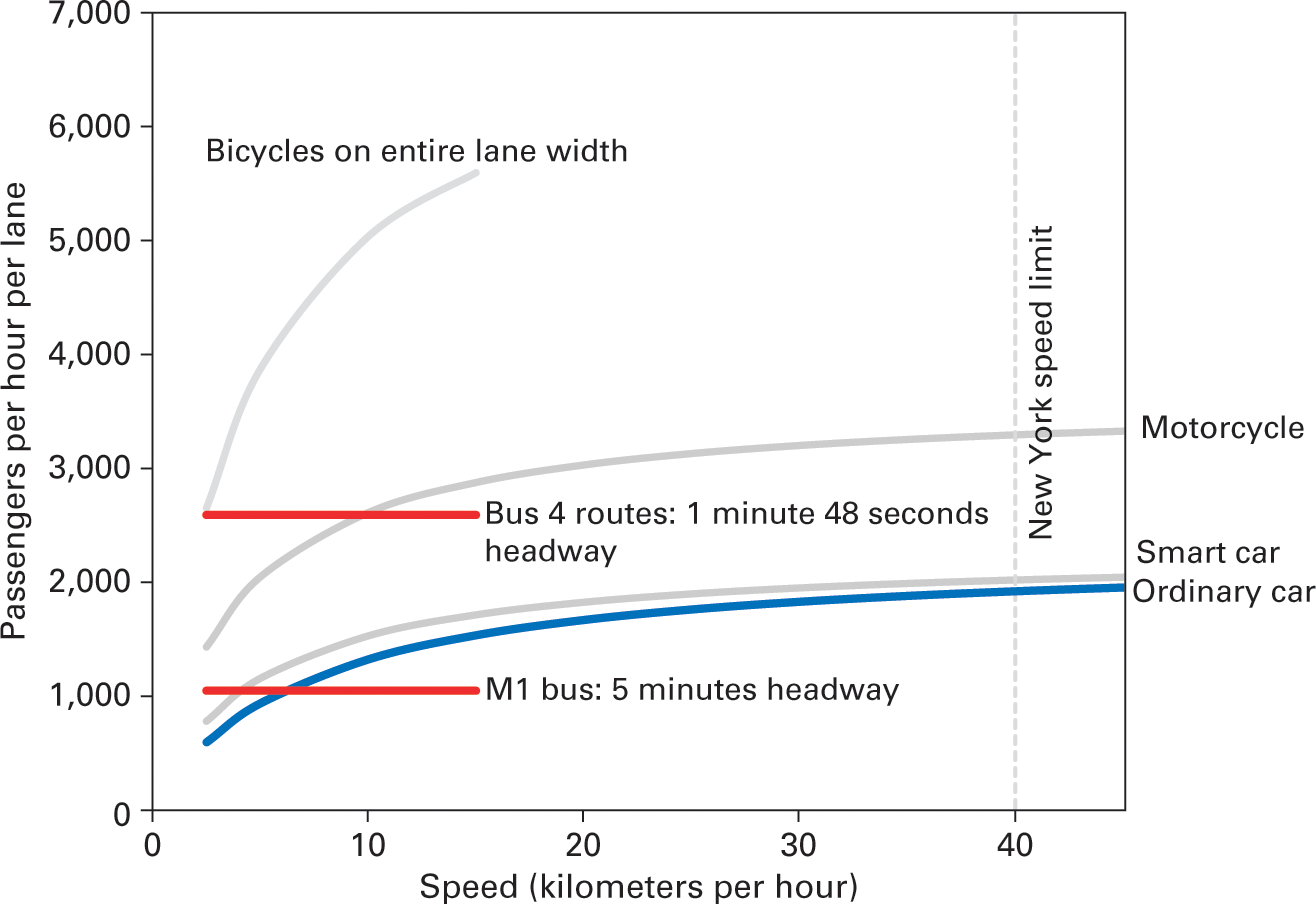

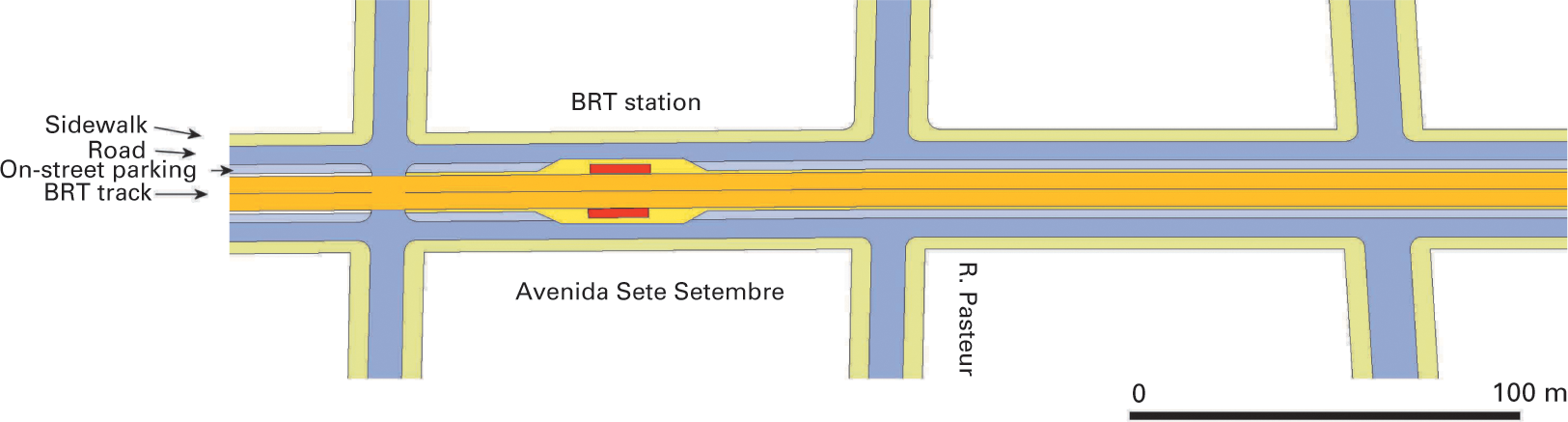

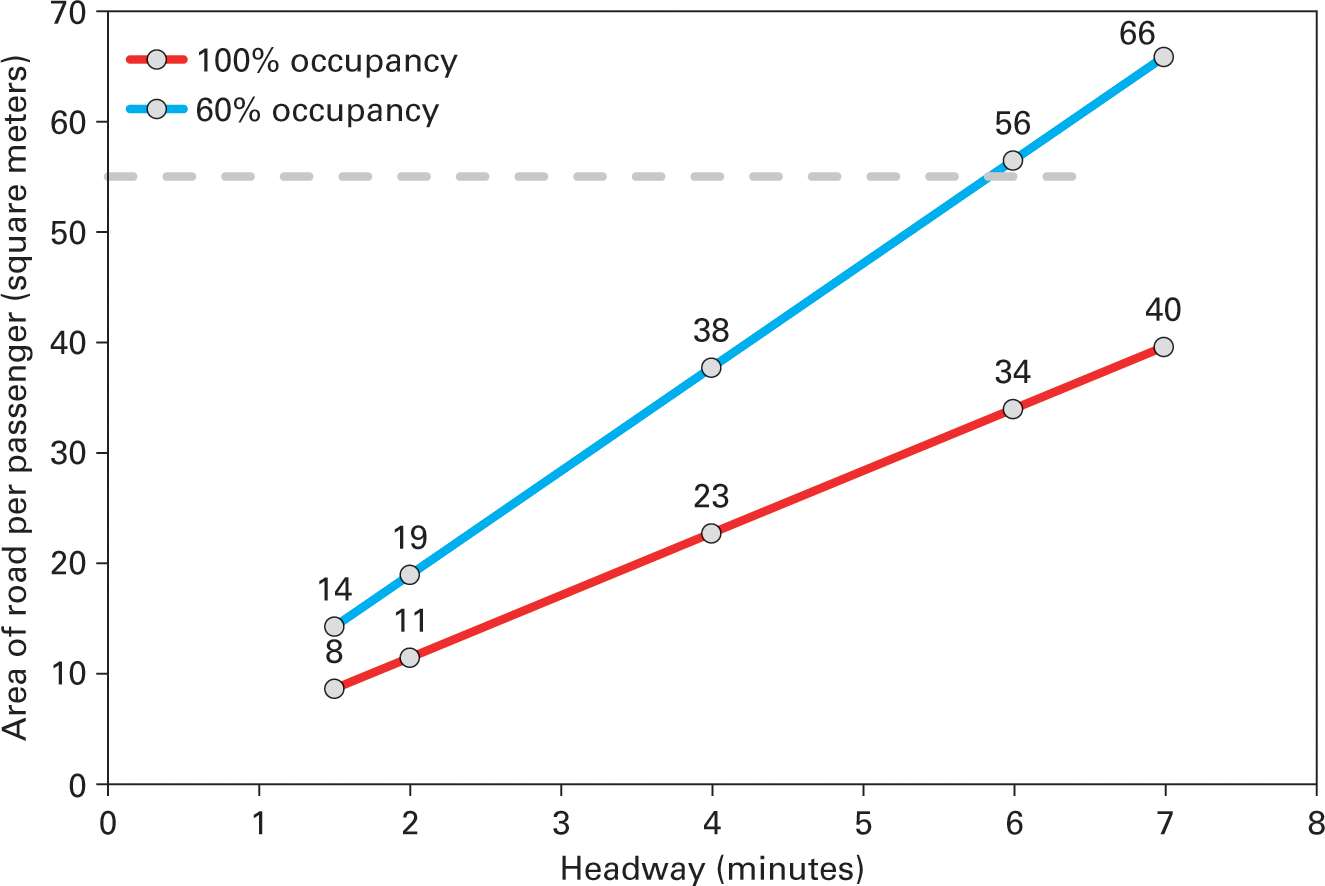

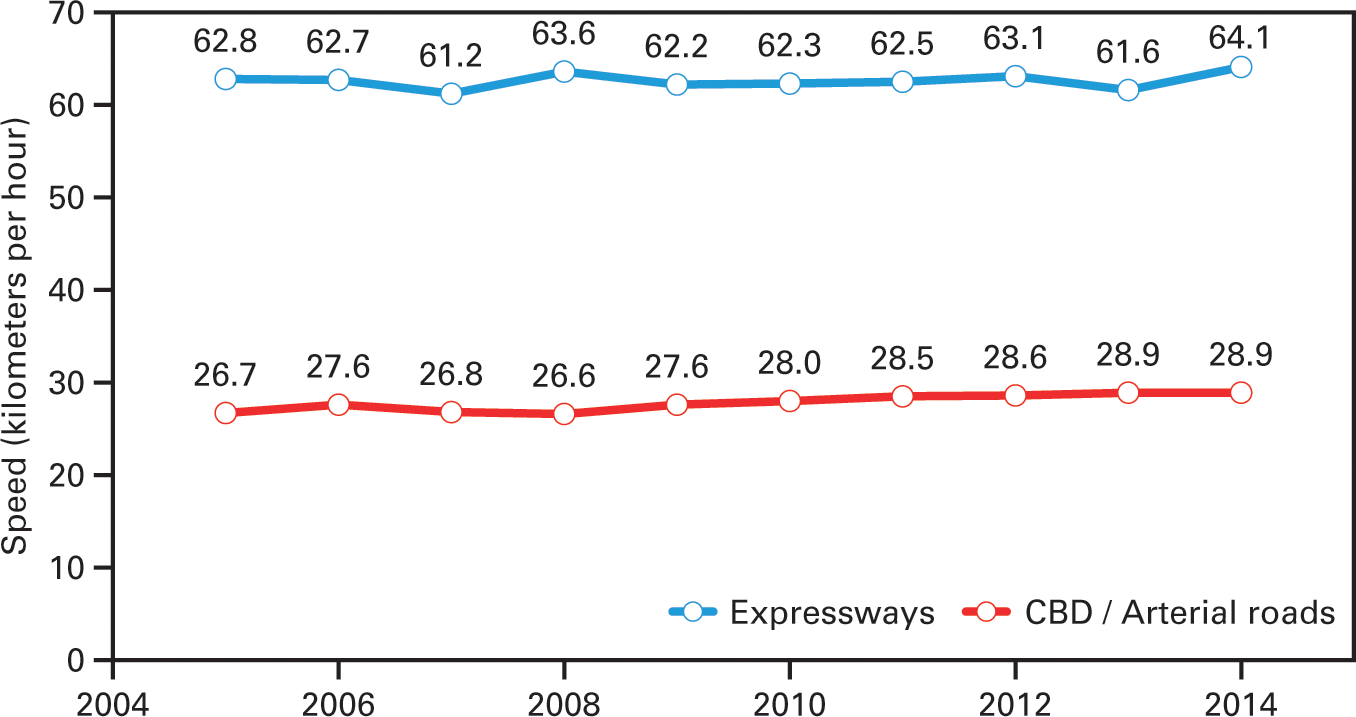

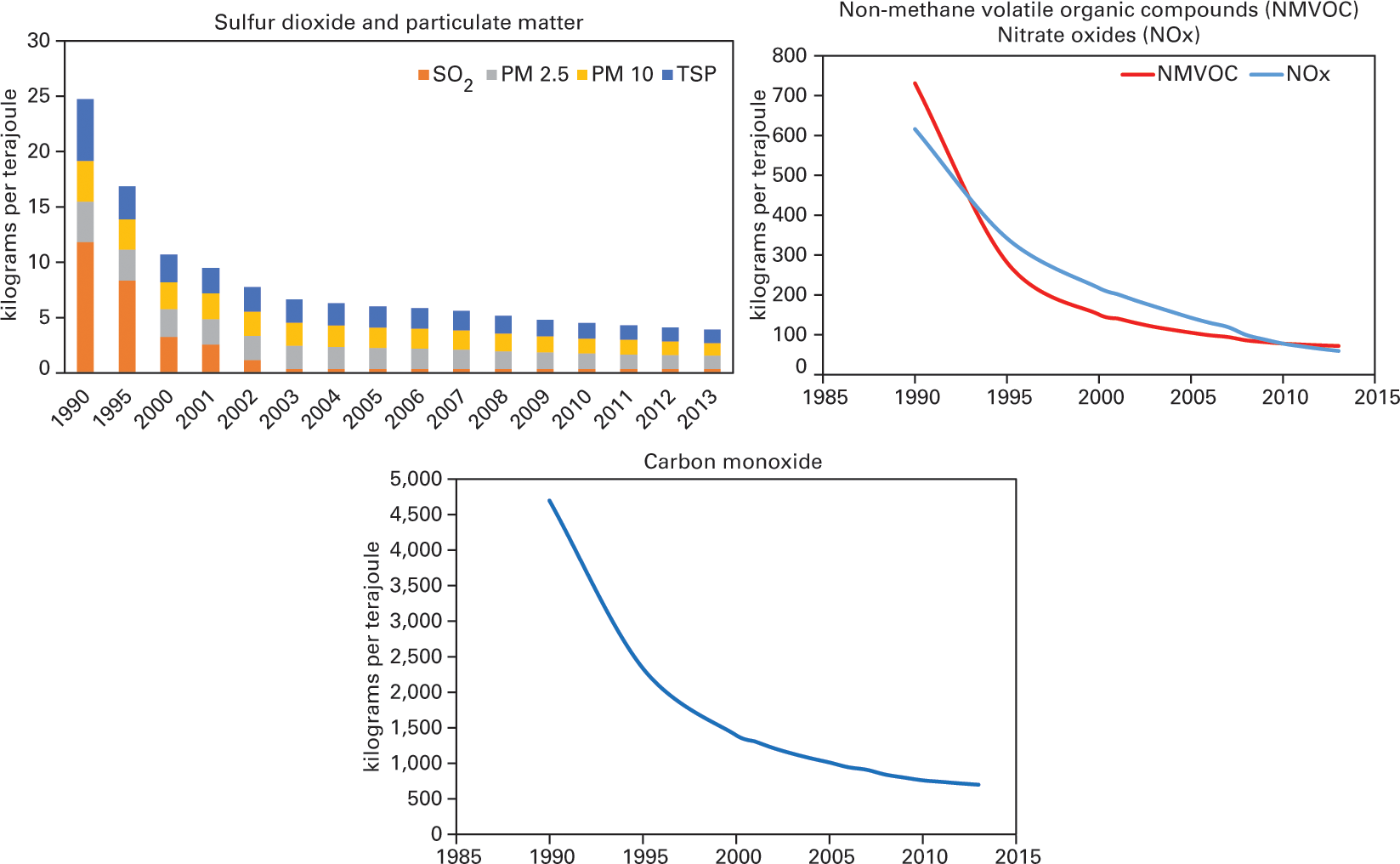

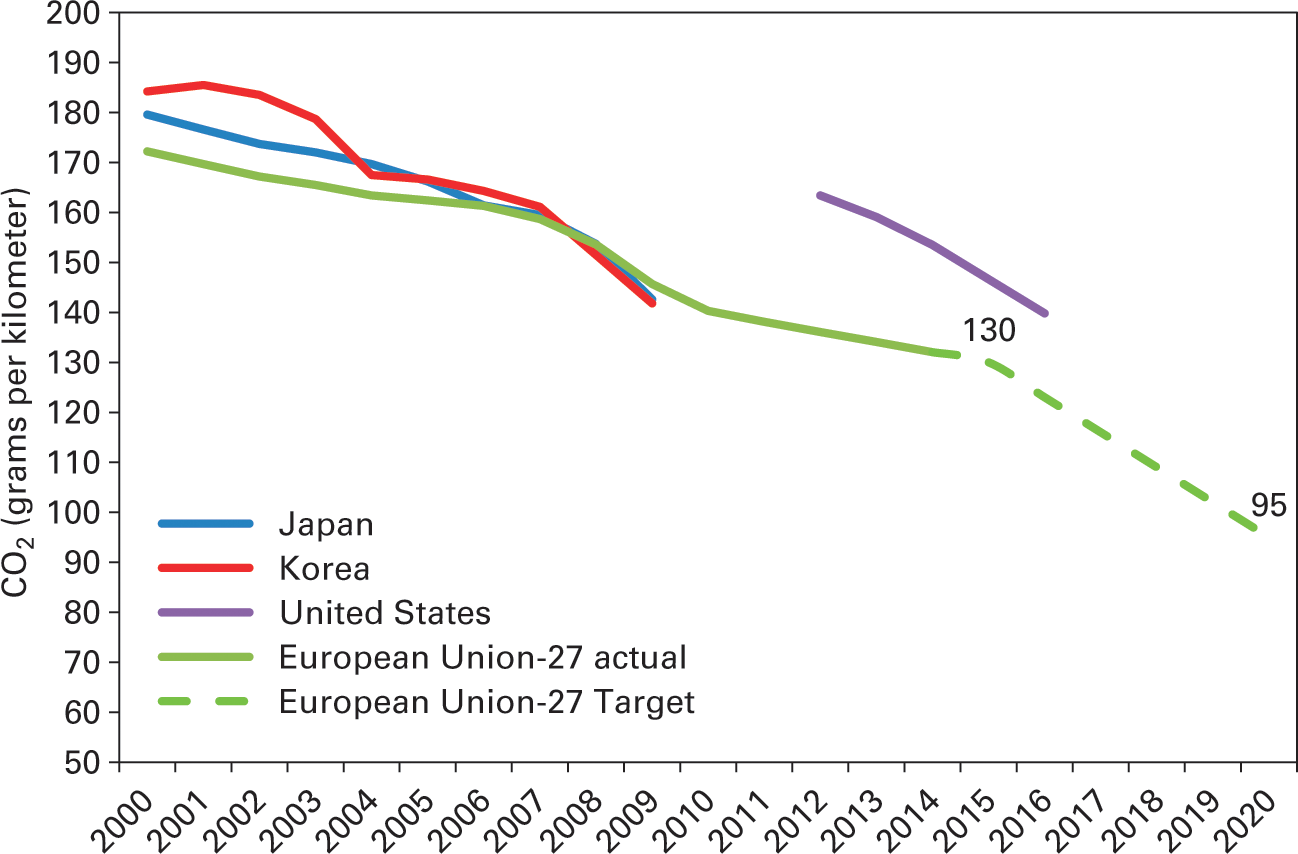

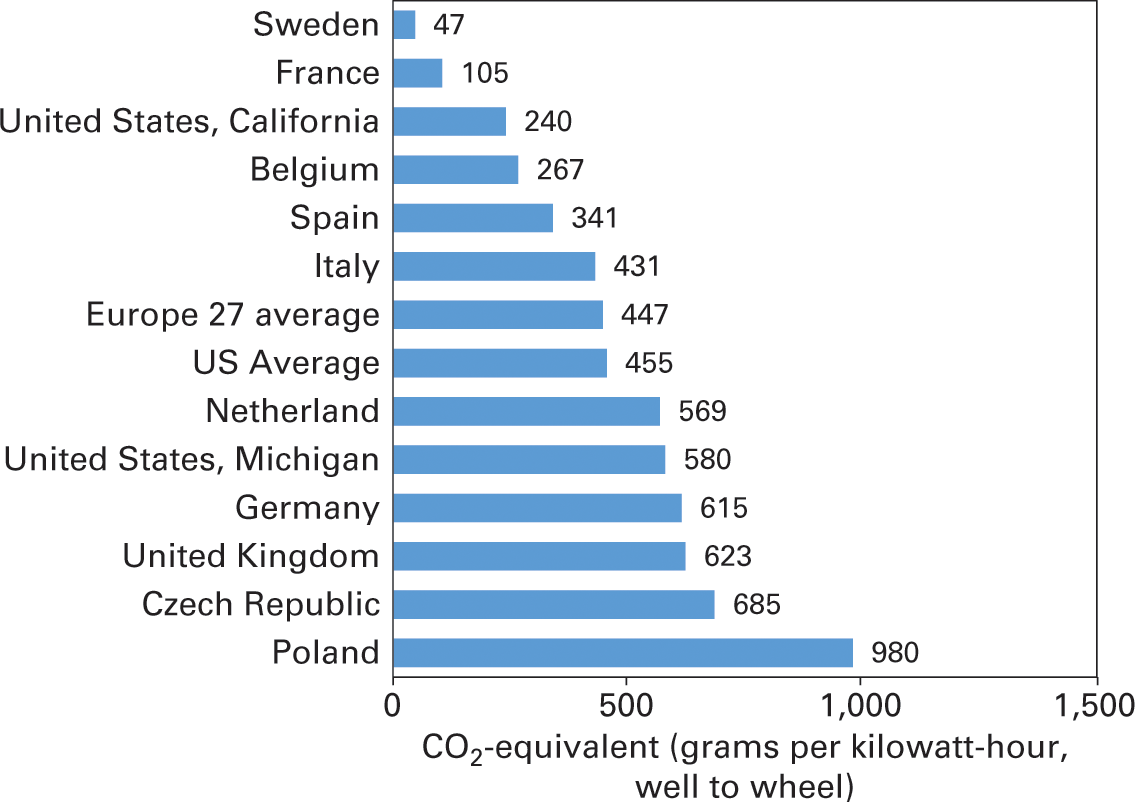

Using TTI to measure congestion is useful as a relative measure of mobility in a city (providing the benchmark free flow speed has not changed, of course, as it did in New York in 2014). It is also useful to identify streets where traffic management needs to be improved. However, TTI is not a good proxy for mobility when comparing cities. What is important for mobility is the changes in average travel time.