The Corporate University and Alternative Corporealities

Most teachers and students of writing experience the cultural practice of composition as a difficult, messy, disorienting affair—the encounter between a writer and the blank page or computer screen, like any encounter between two bodies, can leave one, as Tina Turner suggests in “What’s Love Got to Do with It?”, dazed and confused:

It may seem to you

That I’m acting confused

When you’re close to me.

If I tend to look dazed,

I read it someplace

I got cause to be.

Turner’s claim to have “read someplace” about the disconcerting effects of the more general encounter between self and other, moreover, is amply borne out by anti-identitarian theories of the past few decades that document the impossibility—given the ways all identities are continually shaped and reshaped in and through multiple communities and discourses—of composing, or writing into existence, a coherent and individual self.

More than fifty years ago Kenneth Burke argued that composition is a cultural practice that would seem to be inescapably—even inevitably—connected to order.1Webster’s Dictionary authoritatively defines “composition” as a process that reduces difference, forms many ingredients into one substance, or even calms, settles, or frees from agitation:

compose vb composed; composing [MF composer, fr. L componere (perf. indic. composui)] vt (15c) 1 a : to form by putting together : FASHION <a committee composed of three representatives—Current Biog> b : to form the substance of : CONSTITUTE < composed of many ingredients> c : to produce (as columns or pages of type) by composition 2 a : to create by mental or artistic labor : PRODUCE <~a sonnet sequence> b (1) : to formulate and write (a piece of music) (2) : to compose music for 3 : to deal with or act on so as to reduce to a minimum <~their differences> 4 : to arrange in proper or orderly form @~her clothing: 5 : to free from agitation : CALM, SETTLE <~a patient> ~vi : to practice composition

In his study of the uses of language and strategies of resistance in an urban Chicano/a community, Ralph Cintron describes composition or writing as a “discourse of measurement” that is, especially in the exclusionary institutional forms it usually takes within the academy, “highly routinized” and controlled by an “ordering agent” (210, 229):

Writing is the making of an order and the blank surface is that space or servant that bears the order. Typically, writing catches the eye, but the surface that receives the writing does not. In this sense, writing contains the stronger presence, and the surface that receives the writing is defined by that presence. The surface, then, is an ordered, limited space cleared of obstacles and ready to be acted upon by an ordering agent wielding a highly routinized tool.

How, then, to acknowledge and affirm the experiences we draw from multiple academic and nonacademic communities where composing (in all senses of the word) is clearly an unruly, disorderly cultural practice? Can composition theory work against the simplistic formulation of that which is proper, orderly, and harmonious? If, as the dictionary definition suggests, composing is somehow connected to labor, is it possible to resist the impulse to focus on finished products (the highly routinized, “well-made” essay; the sonnet sequence; the supposedly secure masculine or heterosexual identity) and to keep that labor in mind as we inquire into what composition means and into what it might mean in the future? To adapt Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, what vital role might contemporary composition have in the production of producers (Empire 32)? What would happen if, true to our experiences in and out of the classroom, we continually attempted to reconceive composing as that which produced agitation—to reconceive it, paradoxically, as what it is? In what ways might that agitation be generative?2

Although it is by no means universally acknowledged (to judge by how little or how slowly pedagogical and institutional practices have changed), there is nonetheless widespread critical recognition at this point that composition, as it is currently conceptualized and taught in most U.S. colleges and universities, serves a corporate model of efficiency and flexibility.3 What we might call the current “corpo-reality” of composition guarantees that instruction is often streamlined across dozens of classes at a given institution, with standardized texts (handbooks, guides to the writing and research process, essay collections) required or strongly encouraged (either by campus or departmental administrators or by publishing houses). Inside and outside the university, corporate elites demand that composition courses focus on demonstrable professional-managerial skills rather than critical thought—or, more insidiously, “critical thought” is reconceptualized through a skills-based model ultimately grounded in measurement and marketability, or measurement for marketability. The most troubling feature of our current corpo-reality is that composition at most institutions is routinely taught by adjunct or graduate student employees who receive low pay and few (if any) benefits: the composition work force, at the corporate university, is highly contingent and replaceable, and instructors are thus often forced to piece together multiple appointments at various schools in a region.

I find these arguments that composition serves a corporate model of efficiency convincing, and it is vitally important for teachers and scholars of composition and composition theory to remain attentive to the ways we are positioned to serve professional-managerial interests. In many ways, however, despite the material base of these critiques, they remain strangely incorporeal—in other words, these critiques are not yet especially concerned with theorizing embodiment and/in the corporate university. Perhaps this is because corporate processes seem to privilege, imagine, and produce only one kind of body on either side of the desk: on one side, the flexible body of the contingent, replaceable instructor; on the other, the flexible body of the student dutifully mastering marketable skills and producing clear, orderly, efficient prose.

Chapters 2 and 3 focused on highly charged institutional and institutionalized sites where cultural signs of queerness and disability appear and where, in many ways, they are made to disappear to shore up dominant forms of domesticity and rehabilitation, respectively. In this chapter, I turn to another institutional site, the contemporary university, where anxieties about disability and queerness are likewise legible. In particular, I extend the critical dialogue on composition and the contemporary university by arguing for alternative, and multiple, corporealities. I contend that recentering our attention on the composing bodies in our classrooms can inaugurate and work to sustain a process of “de-composition”—that is, a process that provides an ongoing critique of both the corporate models into which we, as students and teachers of composition, are interpellated and the concomitant disciplinary compulsion to produce only disembodied, efficient writers. Most important, I make the somewhat polemical claim that bringing back in composing bodies means, inevitably, placing queer theory and disability studies at the center of composition theory.4

Interrogating but not resolving one of the paradoxes at the heart of composition (whereby composing is defined as the production of order and experienced as the opposite), I argue for the desirability of a loss of composure, since it is only in such a state that heteronormativity might be questioned or resisted and that new (queer/disabled) identities and communities might be imagined.5 In the sections that follow, then, I first sketch out more thoroughly the paradox in which composing bodies find themselves, locating specifically the ways in which composition undergirds heteronormativity and heteronormativity undergirds composition. Next, in order to challenge such understandings of composition, I argue for what I call the “contingent universalization” of queerness and disability. Finally, I briefly consider two composition courses at George Washington University, along with the institutional context that both enabled and endangered them, in order to materialize the processes of decomposition that I advocate. The institutional machinery that I critique most pointedly in the coda to this chapter largely concerns itself with managing difference, with producing what Stuart Hall calls “the difference that may not make a difference” (“What Is This ‘Black’?” 467). Conversely (and perversely), the cultural studies pedagogy that has been accessed, continuously and collectively, at GWU has insisted on materializing the difference that makes a difference, even if and as that difference is “by definition contradictory and … impure, threatened by incorporation or exclusion” (471). Writing at GWU—as well as writing in and around the corporate university more generally—remains a critical process, regardless of attempts to generate, and manage, the desire for finished products (finished products marked particularly, as I will demonstrate, by the GWU brand). Ultimately, ongoing writing processes in the corporate university make clear that composition can, as David Halperin writes about queerness, “open a social space for the construction of different identities, for the elaboration of various types of relationships, for the development of new cultural forms” (66–67). This chapter sketches some of the ways in which that queer process proceeds.

As I suggest in chapter 1, feminists and queer theorists have demonstrated for more than three decades that heterosexuality, particularly for women, is not a choice but a compulsory identity that secures a dominant patriarchal system. Compulsory femininity (for women), masculinity (for men), and heterosexuality are (re)produced in and through a wide variety of cultural institutions. Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick has famously (and wryly) observed: “Advice on how to help your kids turn out gay, not to mention your students, your parishioners, your therapy clients, or your military subordinates, is less ubiquitous than you might think. On the other hand, the scope of institutions whose programmatic undertaking is to prevent the development of gay people is unimaginably large” (Tendencies 161). The finished product that emerges from this “unimaginably large” institutional matrix is the supposedly secure masculine or feminine heterosexual identity; the institutions that Sedgwick nods toward here are highly invested in a process we might describe as “composing straightness”—compulsory heterosexuality, with its correctly gendered and embodied participants, is continually produced from the disorderly array of possible human desires and embodiments.

But composing straightness is no easy affair. As Judith Butler’s body of work makes clear, the compulsory nature of gendered positions ensures that those subjected to the system (all of us) are catapulted into endless attempts to get it right—into repetitions (of masculinity, femininity, heterosexuality) that, in their proliferation, ironically threaten to destabilize the very identifications that any given performance would purport to fix. The fact that heterosexuality is destined to fail and always in process, however, does not change the fact that most people understand it as wholly natural. Although heterosexuality is without question a product of complex cultural, economic, and historical processes, it is by no means experienced as such. The finished heterosexual product is so fetishized that the composition process cannot be acknowledged; the institutions that compose straightness thus simultaneously produce ideologies that render the process itself virtually unthinkable.

The institutions in our culture that produce and secure a heterosexual identity also work to secure an able-bodied identity. Fundamentally structured in ways that limit access for people with disabilities, such institutions perpetuate able-bodied hegemony, figuratively and literally constructing a world that always and everywhere privileges very narrow (and ever-narrowing) conceptions of ability. Advice on how to help your kids turn out disabled, not to mention your students, your parishioners, your therapy clients, or your military subordinates, is less ubiquitous than you might think. Certainly there are innumerable institutions devoted to a medical model of disability; indeed, the scope of institutions designed to secure a medical model of disability (i.e., designed to proffer advice on how to help your kids turn out pathologized) is unimaginably large. The disability rights movement and disability studies, however, are the only forces shaping locations where the cultural model of how to turn out disabled is available, and the scope of these cultural and political movements currently pales in comparison with the scope of institutions that (re)produce dominant understandings of able-bodiedness.

I will talk more about queer/disabled responses to this state of affairs in the next two sections of this chapter. The main reason I underscore the ways in which a disavowed composing process undergirds compulsory able-bodiedness and heterosexuality, however, is to consider how similar normative processes are at work in our current understandings of composition. My contention is that “straight composition”—that is, common sense or currently hegemonic understandings of composition—requires similar compulsory identifications and engages in similar disavowals. Despite the best efforts of many individual composition theorists and instructors, and despite a decades-long conversation about process and revision, composition in the corporate university remains a practice that is focused on a fetishized final product, whether it is the final paper, the final grade, or the student body with measurable skills. If this emphasis is not necessarily (or even often) pronounced in a given individual classroom, it is nonetheless pronounced at the level of administrative (or governmental, or corporate) surveillance of those classrooms. Individual instructors—and even institutions—may focus on process, in other words, but corporate elites nonetheless want to see a return on their investment. Contemporary composition is a highly monitored cultural practice, and those doing the monitoring (on some level, all of us involved) are intent on producing order and efficiency where there was none and, ultimately, on forgetting the messy composing process and the composing bodies that experience it.

The contemporary cultural and socioeconomic contexts in which writing studies is located are what most concern me in this chapter. In order to understand these contemporary circumstances better, however, it’s worth pointing out briefly that the much more general linkages I am making here are not entirely new, even if the particular convergence of composition, heterosexuality, and able-bodied identity has not been detailed. The composition of a coherent and disciplined self in modernity has, in fact, often been linked to the composition of orderly written texts. In 1690, for instance, in his Essay Concerning Human Understanding, John Locke wrote: “Let us suppose the mind to be, as we say, white paper void of all characters.” Tamar Plakins Thornton begins her study Handwriting in America: A Cultural History with this dictum, describing it as Locke’s “now-famous notion of the human being as a tabula rasa, who acquires reason and knowledge through experience” (3). Although Handwriting in America is not focused on the history of composition in the United States per se, Thornton similarly links the formation of subjectivities to the ways in which writing has been conceptualized. “How could the development of the human self and the acquisition of writing skills,” she asks, “have anything to do with each other?” (3). With Locke’s dictum as a backdrop, Thornton proceeds to answer her own question by tracing ideas about handwriting that emerged and developed in the eighteenth century alongside opposing ideas about print. Thornton contends that the filling of the blank page—the composition of a handwritten text—simultaneously composed a self with a recognizable location in a social order hierarchically arranged according to class, gender, and occupation. The self written into existence by men of commerce, for instance, was meant to be distinguishable from that written into existence by gentlemen and ladies, who in turn composed selves that could be properly distinguished from each other.

Thornton’s history could be understood as diametrically opposed to the points I am making about contemporary composition, subjectivity, and postmodernity, especially since the (printed) finished products of most composition courses have very little to do with handwriting. As Thornton demonstrates, in the eighteenth century, the perceived close link between handwriting and subjectivity contrasted to the perceived distance between print and subjectivity: “As men and women exploited the impersonality of print to its fullest, they came to understand handwriting in contradistinction to print and to make handwriting function in contradistinction to the press, as the medium of the self” (30). I would argue, however, that contemporary ideas about composition more properly descend from the ideas about handwriting that Thornton excavates than from the ideas about print that were dominant in the early days of a print culture.6 Certainly in the nineteenth century when composition became compulsory in American universities, handwriting would have been the medium of choice, but this is not the only reason I would place composition in such a line of descent. As queer and disability studies have repeatedly shown, the bourgeois culture of the past few centuries has only become more obsessed with the composed, self-possessed, “normal” subject, properly located in a hierarchical social order. If some of the disciplinary practices shaping such a self can be clearly tied to handwriting in the eighteenth century, when a normalized, bourgeois culture was still emergent, they have undoubtedly become unmoored from such a specific location in the centuries since then. Even though Thornton tucks Michel Foucault away in only one endnote in her study (204–205 n.16), some of his general insights in Discipline and Punish could more thoroughly extend her own. Discipline and Punish purports to examine “the birth of the prison” but of course ends up demonstrating that docile bodies are produced in a range of cultural locations: the schoolroom, the clinic, the asylum, the workplace.7 Similarly, the composed self that emerges in Thornton’s history of handwriting has ultimately come to be produced in other locations, which are centrally concerned with the acquisition of writing skills.

Although we could thus be said to inherit in contemporary composition studies the legacy Thornton traces, that legacy is now compounded by the postmodernizing urgency that characterizes this particular moment in the history of capitalism and the history of the university. For those administering composition inside and outside the university, it often seems that there is perpetual panic about students’ perceived lack of the basic (professional-managerial) communication skills they supposedly need. We may inherit an Enlightenment legacy where the production of writing and production of the self converge, but the corporate university also extends that legacy in its eagerness to intervene in, and thereby vouchsafe, the kinds of selves produced. The call to produce orderly and efficient writing/docile subjects thus takes on a heightened urgency in our particular moment.

Through my linkage of two varieties of composition in this section, however, my desire in the end is to keep in play the critical possibilities that are inherent in Butler’s theory of gender trouble. That is, if composing straightness and able-bodiedness is always on some level impossible, then perhaps the same could be said about straight composition. The perpetual panic over what is supposedly not happening in composition classrooms and what supposedly needs to be happening there guarantees that our identities are indeed compulsory, even if—or precisely because—we are not getting those identities exactly right. If we are thus catapulted into cycles of repetition as students and scholars of composition, following Butler we could argue that the repetition ensures that straight composition is inevitably comedic, impossible to perform dutifully, and without incoherence. De-composition and disorder always haunt the composition classroom intent on the production of order and efficiency.

There is, however, nothing comedic about certain material cycles of repetition that are part of the scenario I describe—the cycle of repetition, for example, whereby a given instructor, year after year, pieces together numerous teaching positions in composition but receives neither a living wage nor security in return. If all of our classrooms are virtually decomposed, they are not necessarily “critically de-composed”—that is, actively involved in resisting the corporate university and disordering straight composition. And, indeed, critical de-composition is impossible on an individual level, impossible without what Butler labels “collective disidentifications” with the efficient identities we are compelled to corporealize (Bodies That Matter 4).

In the conclusion to his ethnography of the Chicano/a community he calls “Angelstown,” Cintron reflects on the composing process, which encourages students “to shape language in school-appropriate ways … reinforcing what is standard and conventional and sloughing off the dialectical and disruptive” (231). Cintron finds a “saving grace” even within such rigidity, a saving grace which he describes as “the sweetness of critique that always finds the remainder, the forgotten, the hidden, and thereby, exposes as illusion that sense of control, that sense of a ruling self in control” (231). There is a certain pathos in Cintron’s conclusion, however, that would be less pronounced if “the saving grace of critique” were not so seemingly individual and if it could be more clearly articulated to collective political projects specifically concerned with embracing the disruptive.8 For Cintron, a certain kind of order is inevitable:

Call it a vicious pleasure: written language seems to offer a ruling self, whether author or reader, the special opportunity of reducing language and experience to something manageable and, thus, to create an order. Even if the order sought is that of disorder, as in certain kinds of poetry, what gets created is a domesticated version of disorder, in short, the appearance of disorder, rather than the being of disorder. (229)

We might perpetually lament this conservative impulse at the center of composition, but—for Cintron—we cannot eradicate it. We can, instead, simply take solace in the sweetness of critique that finds the remainder, the forgotten, the hidden.

The sweetness of critique seems to me less infused with pathos when imagined through collective disidentifications, however. All writing, even writing committed to disorder, may reduce language and experience to something manageable, but surely there is a difference between the “school-appropriate” writing Cintron cites—writing that helps to maintain a hegemonic social and economic system—and the collective writing practices that would speak back to the particular institutional circumstances in which we find ourselves, even if, without question, the resistant writing in turn can and should still be subject to the sweetness of critique.

Butler writes: “It is important to resist that theoretical gesture of pathos in which exclusions are simply affirmed as sad necessities of signification. The task is to refigure this necessary ‘outside’ as a future horizon, one in which the violence of exclusion is perpetually in the process of being overcome” (Bodies That Matter 53). Queer and crip theory, if conceptualized as indissolubly linked to collective queer/disabled movements outside the university, are sites for continually imagining the collective disidentifications that make possible the refiguring Butler describes. Positioned to critique the finished products heteronormativity demands, queer/crip perspectives can help to keep our attention on disruptive, inappropriate, composing bodies—bodies that invoke the future horizon beyond straight composition.

If the fetishized finished product in the composition classroom has affinities with the composed heterosexual or able-bodied self, I would argue that the composing body, in contrast, is in some ways inevitably queer/disabled. Sedgwick, after considering the features that characterize the composed heterosexual self, particularly listing (for more than a page) “the number and difference of the dimensions that ‘sexual identity’ is supposed to organize into a seamless and univocal whole,” contends that queerness refers to “the open mesh of possibilities, gaps, overlaps, dissonances and resonances, lapses and excesses of meaning when the constituent elements of anyone’s gender, of anyone’s sexuality aren’t made (or can’t be made) to signify monolithically” (Tendencies 8). Able-bodied identity, similarly, emerges from disparate features that are supposed to be organized into a seamless and univocal whole: a standard (and “working”) number of limbs and digits that are used in appropriate ways (i.e., feet are not used for eating or performing other tasks besides walking; hands are not used as the primary vehicle for language); eyes that see and ears that hear (both consistently and “accurately”); proper dimensions of height and weight (generally determined according to Euro-American standards of beauty); genitalia and other bodily features that are deemed gender-appropriate (i.e., aligned with one of only two possible sexes, and in such a way that sex and gender correspond); an HIV-negative serostatus; high energy and freedom from chronic conditions that might in fact impact energy, mobility, and the potential to be awake and “functional” for a standard number of hours each day; freedom from illness or infection (ideally, freedom from the likelihood of either illness or infection, particularly HIV infection or sexually transmitted diseases); acceptable and meaurable mental functioning; behaviors that are not disruptive, unfocused, or “addictive”; thoughts that are not unusual or disturbing. Optimally these features are not only aligned but are consistent over time—regeneration is privileged over degeneration (read: the effects of aging, which should be resisted, particularly for women). If the alignment of all these features guarantee the composed able-bodied self, then—following Sedgwick on queerness—we might say that disability refers to the open mesh of possibilities, gaps, overlaps, dissonances and resonances, lapses and excesses of meaning when the constituent elements of bodily, mental, or behavioral functioning aren’t made (or can’t be made) to signify monolithically.

One could easily conclude from these circumstances that we are all disabled/queer, since all of us (at some point and to some degree—or to some degree at most points) inhabit composing bodies that exist prior to the successful alignment of all of these features. I want to both resist and advance this conclusion. Obviously, definitional issues have been central to both queer and disability rights movements—who counts as queer, who counts as disabled? As Simi Linton points out, following Carol Gill: “The problem gets stickier when the distinction between disabled and nondisabled is challenged by people who say, ‘Actually, we’re all disabled in some way, aren’t we?’” (Linton 12–13; Gill 46). Similar complacent assertions are made about queerness—“actually, we’re all queer in some way, aren’t we?”—and I believe it is important to resist such assertions, recognizing them as able-bodied/heterosexual containments: an able-bodied/heterosexual society doesn’t have to take seriously disabled/queer claims to rights and recognition if it can diffuse or universalize what activists and scholars are saying as really nothing new and as really about all of us. In other words, the question “aren’t we all queer/disabled?” can be an indirect way of saying, “you don’t need to be taken seriously, do you?”

In some very important ways, we are in fact not all queer/disabled. The fact that some of us get beaten and left for dead tied to deer fences or that others of us die virtually unnoticed in underfunded and unsanitary group homes should be enough to highlight that the heterosexual/queer and able-bodied/disabled binaries produce real and material distinctions.9However, recognizing that the question “aren’t we all queer/disabled?” can be an attempt at containment and affirming that I resist that containment, I nonetheless argue that there are moments when we are all queer/disabled, and that those disabled/queer moments are desirable. In particular, a crip theory of composition argues for the desirability and extension of those moments when we are all queer/disabled, since it is those moments that provide us with a means of speaking back to straight composition in all its guises. Instead of a banal, humanistic universalization of queerness/disability, a crip theory of composition advocates for the temporary or contingent universalization of queerness/disability.10

The flip side of the fact that there are moments when all of us are queer/disabled is the fact that no one (unfortunately) is queer/disabled all of the time—that would be impossible to sustain in a cultural order that privileges heterosexuality/able-bodied identity and that compels all of us, no matter how distant we might be from the ideal, into repetitions that approximate those norms.11 Critical de-composition, however, results from reorienting ourselves away from those compulsory ideals and onto the composing process and the composing bodies—the alternative, and multiple, corporealities—that continually ensure that things can turn out otherwise. Put differently, critical de-composition results from actively and collectively desiring not virtual but critical disability and queerness. Instead of solely and repeatedly asking the questions Cintron rightly cites as central to “school-appropriate” writing instruction—“‘Have you chosen the right word?’ ‘Can this be made clearer?’ ‘Your argument here is inconsistent.’ ‘Are you being contradictory?’” (231)—we might ask questions designed to dismantle our current corpo-reality: How can we queer this? How can we crip it? What ideologies or norms that are at work in this text, discourse, program need to be cripped? How can this system be de-composed?

I recognize that the general point I am making here is one that has been central to a certain mode of composition theory for some time. Although I want to complicate the project, I in fact believe that one of the conditions of possibility for my own analysis here is precisely the collective and ongoing project, within composition theory, of arguing for the difficult but necessary work of continually resisting a pedagogy focused on finished products.12 To take just one example, William A. Covino writes:

In even the most enlightened composition class, a class blown by the winds of change through a “paradigm shift” into a student-centered, process-oriented environment replete with heuristics, sentence combining, workshopping, conferencing, and recursive revising, speculation and exploration remain subordinate to finishing.… While writing is identified exclusively with a product and purpose that contain and abbreviate it, writers let the conclusion dictate their tasks and necessarily censor whatever imagined possibilities seem irrelevant or inappropriate; they develop a trained incapacity to speculate and raise questions, to try stylistic and formal alternatives. They become unwilling and unable to fully elaborate the process of composing. (316–317)

As I asserted at the beginning of this chapter, however, such critiques remain decidedly incorporeal—composition theory has not yet recognized (or perhaps has censored the “imagined possibility”) that the demand for certain kinds of finished projects in the writing classroom is congruent with the demand for certain kinds of bodies. Not recognizing this congruence, in turn, can bring us to a point where the imagined solution is the sort of disembodied postmodernism Covino calls for. I’m suggesting that queer theory and disability studies should figure centrally into the work that we do in composition and composition theory—that, in fact, they already do in some ways figure centrally into that work, since the critical projects that we have been imagining, projects of resisting closure or containment and accessing other possibilities, are queer/crip projects. In other words, a subtext of the decades-long project in composition theory focusing on the composing process and away from the finished product is that disability and queerness are desirable.

Desiring queerness/disability means not assuming in advance that the finished state is the one worth striving for, especially the finished state demanded by the corporate university and the broader oppressive cultural and economic circumstances in which we are currently located. It means striving instead for “permanently partial identities” (Haraway 154). Indeed, through Donna J. Haraway, we might understand disability/queerness as “not the products of escape and transcendence of limits, i.e., the view from above, but the joining of partial views and halting voices into a collective subject position that promises a vision of the means of ongoing finite embodiment, of living within limits and contradictions, i.e., of views from somewhere” (196). Critical de-composition, in other words, entails recognizing and participating in the multiple and intersecting critical movements—what Haraway calls “an earth-wide network of connections” (187)—that would resist, or stare back at, the corporate “view from above.” Haraway writes: “We need the power of modern critical theories of how meanings and bodies get made, not in order to deny meaning and bodies, but in order to live in meanings and bodies that have a chance for the future” (187).

A more limited but crucial (or, perhaps more positively, precisely such a local/located) “network of connections” characterized the Writing Program at George Washington University for most of the past decade. This program was responsible for English 10 and 11, the two-semester composition sequence that fulfilled a literacy requirement for almost all first-year students. In contrast to more streamlined, “efficient” writing programs, the courses taught at GWU did not employ standardized texts, nor did they necessarily share, across sections, a conception of the kinds of writing projects students should be working on (although we discussed our varying conceptions continually). The courses were organized as writing-intensive seminars, and many or most were semester-long explorations of specific cultural studies topics such as international feminisms, rhetoric and technology, or contemporary youth cultures. The rhizomatic program was nurtured by the work of an openly Marxist director, Dan Moshenberg. Over time, faculty in the program (including Moshenberg) instituted movement of the discussions in our classroom out in public: the second semester concluded with an annual “Composition and Cultural Studies Conference” involving close to one thousand students presenting their work, or attending to and debating others’ work, in Deaf studies, disability studies, queer studies, postcolonial studies, rhetoric and democracy, and a host of other topics.13

In this section, I describe some of the courses I was able to shape within this critically de-composing context, where cultural studies perspectives and pedagogies were actively and collectively at work. These descriptions, however, should not be read merely as culminating the theories I developed in previous sections, if culmination (or even a simple example), by bringing the discussion to a particular, fixed point, generates a manageable order, reduces difference, and calms, settles, or frees from agitation. Indeed, at least some of those observing the Writing Program at GWU—described variously by the English department and others as “stakeholders”—perceived it to be unmanageable, and composed a less unruly alternative. In May 2002, at an “Academic Excellence” management forum, the English department at GWU learned that our Writing Program was being dismantled, that a new program would be instituted outside the department, that it would be staffed entirely by non-tenure-track professors, and that it would more directly focus on skills acquisition and measurable achievement. This proposal had been in development for almost a year, although faculty teaching in neither the Writing Program nor the English department more broadly were consulted. Thus, after describing in this section some of the classes I taught in GWU’s Writing Program, I will insist in my coda that de-composition is a process that is always commencing; the fact that specters of queerness and disability are conjured away suggests, in fact, that the struggle never culminates but is and must be ongoing.

The English 10 and 11 courses I shaped were centered on disability studies and/or queer studies and had titles such as “Reading and Writing a Crisis: Rhetoric, AIDS, and the Media” and “Critical Bodies: Disability Studies and American Culture.” I taught the “Critical Bodies” course, a composition course organized as an introduction to disability studies, for the first time in the fall of 1999 (I repeated the course in the fall of 2000). I followed that course, in the spring of 2000, with a composition course organized around lesbian, gay, and bisexual studies and called “Out in Public: Contemporary Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Movements.”14

As the “Critical Bodies” course began, many students expected its structure to fit the structure they were coming to recognize from most college classes, with a body of material to be mastered and writing assignments that would be successful if they competently reflected that mastery back to the instructor. This general structure in fact dovetailed with many students’ preconceived notions of disability, which tends to be understood in Western cultures according to a subject/object model—that is, what can “we” (a group assumed to be able-bodied) do for or about “them” (the disabled or “handicapped”)? Several things quickly helped to shift this professional-managerial ethos, not the least a classroom atmosphere where students felt comfortable about “coming out” in relation to disability. Since disability studies in the humanities specifically rejects the objectifying/pathologizing model that would position people with disabilities as always talked about by others and instead produces spaces where people with disabilities speak in their own voices, the material we were reading encouraged students with disabilities to position themselves as subjects. In fact, coming-out stories (stories students were telling about themselves or their families) proliferated more in and around this particular course than in any of the numerous LGBT studies courses I have taught. Most disabilities are not readily apparent, so able-bodied students in the class could initially proceed with the efficient model intent on mastery of an already-composed body of material. The material we were actually reading, however (especially theoretical pieces early in the semester that located disability within a larger history of “normalcy”), as well as the alternative corporealities that were being claimed or cited by other students (around, for instance, diabetes, or learning disabilities, or hard-of-hearing identitis), quickly challenged this mindset.

Ironically, alternative corporealities often emerged in what would seem at first to be an entirely “disembodied” medium.15 Students were required to participate all semester in a discussion on a listserv that linked all three of the sections I was teaching. This was certainly one of the kinds of writing which students were required to “produce” in the course, but it encouraged de-composition and directed attention to (individual and nonindividual) composing bodies in that the important feature of this writing assignment was not the product but the ongoing critical conversation that would never be completely finished or orderly (especially since students reported that it spilled over into other venues, into conversations they were having with friends or in other classes). At various points in the semester, some of the authors we were reading—Abby L. Wilkerson, Michael Bérubé, and Ralph Cintron—either joined the listserv briefly or responded to questions students had written (after distributing the questions to the authors, I later posted their answers to the listserv). Certainly the texts we were reading by these authors initially appeared to students as finished products, but the class eventually had good reasons for questioning such an appearance, as the seemingly authoritative voices that had composed those texts were called back to rethink them.16

In the spring, although I had taught the course on lesbian, gay, and bisexual movements before, the issues I have been discussing throughout this chapter were particularly pronounced, given that the semester was going to end right after the controversial Millennium March on Washington (MMOW) for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgendered rights. In fact, the MMOW, which was held on April 30, 2000, strikes me as a quintessentially “composed” event that was nonetheless haunted from the beginning by disorder and de-composition, by queerness and disability. In 1998, leaders of the Human Rights Campaign (HRC) and the Universal Fellowship of Metropolitan Community Churches (MCC) called for the march. From the beginning, the leadership of the march was top-down, with the leaders alone defining which issues were to be central to the event. Grassroots organizers around the country were critical of the fact that they were not consulted, of the consistent lack of attention to anything more than token diversity throughout the planning process and of the monolithic focus by march leaders (and HRC more generally) on “normalizing” issues such as marriage rights as opposed to more sweeping calls for social justice and for a critique of the multiple systems of power (including corporate capitalism) that sustain injustice.17 Far from critiquing corporate capitalism, HRC was and is understood by many critics as craving corporate sponsorship (and, in fact, corporate logos were so ubiquitous at the march, alongside HRC symbols, that one was left with the sense that the march represented something like “the gay movement, brought to you by AT&T and other sponsors”). Earlier marches had been organized at a grassroots level and had in fact centrally included a larger, systemic critique, and many activists in communities around the country, as well as most queer theorists working in the academy, felt that this march had thus been organized without an adequate awareness of either queer politics or history. By the time of the march, even mainstream media such as the Washington Post and the Nation had covered the controversy.18

As an openly gay professor teaching both queer cultural studies and disability studies in Washington, D.C., it was important to me to take advantage of this highly charged moment. From the beginning of the class, students had been reading about historical splits within the gay movement, particularly the ongoing tension in twentieth-century lesbian and gay history between radical liberationist and liberal reformist politics. Students had read extensive selections from the work of John D’Emilio (and, as in the disability studies class, had in fact been in conversation, via our class listserv, with D’Emilio), who traces these historical tensions from the 1950s through the 1980s in his Sexual Politics, Sexual Communities: The Making of a Homosexual Minority in the United States 1940–1970 and Making Trouble: Essays on Gay History, Politics, and the University. As I emphasize in chapter 5, a radical liberationist tradition places an emphasis on difference and distinction: not necessarily on essential difference but, rather, on how queers are made different by an oppressive society and how a minority identity emerges precisely because of the positions gay men and lesbians occupy within a larger, dominant structure (similar analyses have of course emerged within the disability rights movement over the last few decades). Since oppression according to this tradition is structural and not just a matter of individual prejudice, collective action is needed: sexual minorities need to speak in their own voices, and alongside multiple others. In contrast, a liberal reformist tradition emphasizes sameness; the catch phrase of this tradition is the perennial “gays and lesbians are just like everyone else.” Individuality and individual prejudice are stressed more than structural oppression or collective action, and, over the past fifty years, liberal reformists have often appealed or even deferred to “experts” (doctors, ministers, and, more recently, celebrities).

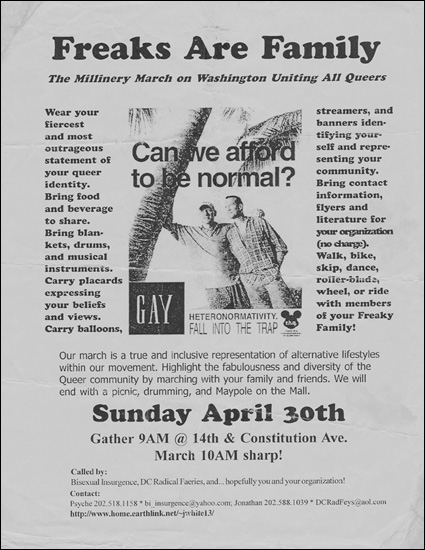

“Walk, bike, skip, dance, roller-blade, wheel, or ride with members of your Freaky Family!” Flyer calling for opposition to the Millennium March on Washington, April 30, 2000. Author’s personal collection.

During the spring of 2000, this tension was being played out just beyond the walls of my composition class. We had also read Michael Warner (The Trouble with Normal) and Sarah Schulman (Stagestruck) on the contemporary commodification and normalization of the movement, and I had examined with students a series of ads directed at gay consumers. The ads that evoked the most discussion were intended to work as a set: a colorful ad for “Equality Rocks,” HRC’s April 29 concert to celebrate the MMOW (the ad featured corporate logos and pictures of Ellen DeGeneres, Melissa Etheridge, and other celebrities who had become overnight “leaders” of the movement simply by coming out) and a flyer from “Freaks Are Family,” a local group that had been formed by members of the D.C. Radical Faeries and Bi Insurgence to protest the homogenization of the movement generally and the MMOW particularly. HRC’s message that gays and lesbians are “just like everyone else” had definite appeal for many, and some students resisted, even angrily, both my own and other students’ critique of HRC and the suggestion that the construction of gays and lesbians as a “niche market” might be problematic. Other students, however, found themselves completely compelled by the alternative corporealities offered by the Freaks Are Family contingent and sought the group out on April 30 in order to demonstrate their support.

My use of “alternative corporealities” to describe what Freaks Are Family offered is meant quite literally: without question, the small group of about fifty protesters was more diverse than the MMOW more generally. The Freaks Are Family contingent included a range of body types, as well as clearly identifiable members of trans, leather, bear, bi, and faerie communities. Diverse and perverse erotic proclivities (decidedly not the homogenous and domesticated married identity sought after by the MMOW), multiple genders, and various disabilities were also represented—and these could be read both on protesters’ bodies and through the signs that we carried (which differed sharply from the mass-produced signs displaying HRC’s ever-cryptic blue and gold equals sign). In contrast to this proliferation of corporealities, HRC and the MMOW—like the straight composition I have been critiquing throughout this chapter—offered only an orderly and singular corpo-reality.

With the image of my students searching for the freaks, I intend to put my students’ work and the (queer/disabled) composing bodies that were at the center of our composition class in conversation with at least part of the earth-wide network of (de-composing) connections outside the walls of our classroom. In the end, however, this chapter is not offered as a specific “nuts and bolts” way to conceptualize the kinds of classroom practices that will compose queerness or disability (that is, the classroom practices that will participate in critical de-composition), and not only because most composition instructors aren’t likely to have the MMOW on hand when they construct their syllabus. De-composition ultimately is inimical to “nuts and bolts” approaches that somehow streamline the process of composition instruction through manuals, teaching “strategies” exchanged like recipes, and the like. Such streamlining removes composition and composition theory from the realm of critical thought and secures its place in the well-run corporate university. De-composition does result, however, from ongoing attentiveness to how a given composition class will intersect with local or national issues such as the MMOW.

The well-run corporate university, in turn, will invariably work to fix de-composing processes. To call back Hardt and Negri, the production of not simply products but student and faculty producers will exacerbate crises that the corporate university will always attempt to transcend. Although many in the English department objected, the May 2002 management forum that reconceptualized writing instruction at GWU eventually led to the formation of a new and autonomous program, the University Writing Program. The literacy requirement for students was also revised: students must now take University Writing 20 (UW20), a one-semester composition course, during their first year, and then must follow this with two Writing in the Disciplines (WID) courses. In contrast to what was often explicitly antidisciplinary in the old program (and to what will remain antidisciplinary in the writing program to come), the new University Writing Program, with its mandate to produce a student body that will go on to write first within very particular boundaries and second—marked by the GWU brand—within neoliberal professional-managerial contexts, is literally disciplining.

Teachers in the new program are required to order one handbook from among five or six possibilities and they must address in the classroom issues of grammar and punctuation (though faculty members continue to insist that they will make the determination as to how this requirement is met). Certain requirements are now attached to the first-year writing course, regarding both the number of pages of student writing that will be generated over the course of the semester (twenty-five to thirty pages of finished writing spread over three papers, at least one of which must involve research) and, with a little more leeway, what will count as effective “outcomes” of the course (there was no agreement but rather continual debate on these particular issues in the old program, though students in the old program generally wrote well over thirty pages each semester). Both UW20 faculty and WID instructors are explicitly charged with incorporating revision into the classes they teach. Certain structural factors, however, are working to ensure that revision in relation to writing at GWU will ultimately vouchsafe particular kinds of finished products and docile bodies.

Although initially the administration insisted that the new program would be staffed solely by (non-tenure-track) full-time assistant professors, as early as fall 2004 graduate teaching assistants and part-time faculty on several tiers (some with benefits, and some without) began teaching in the program. At that time, most part-time faculty at GWU were paid $2,700 a course and received no benefits, although a selection of “regular part-time” faculty hired in the new program received a little more than twice this amount, with some benefits. Regular part-time faculty in the University Writing Program were teaching three courses during the school year; their full-time counterparts, at well over twice the salary with full benefits, were teaching four. “Regular,” of course, implies some continuity; as of this writing, there was no continuity for regular part-time faculty members from year to year. Some of those teaching on regular part-time lines, moreover, explicitly needed disability-related health care coverage.

The University Writing Program was phased in over three years, with incoming students initially tracked randomly into either the new program or the old program. By the 2005–2006 school year, all incoming students were in the new program. Especially during this period, when the program was in its infancy, faculty members were evaluated repeatedly over the course of the semester; “oversight” and “assessment” are among the keywords of the new program. Part of this assessment includes the collection of sample student essays (for every student in UW20) from the beginning and the end of the semester (though it is still not entirely clear who will read the hundreds of essays collected, nor is it yet clear what will exactly mark improvement).

After initially informing faculty, during the 2003–2004 academic year, that they could no longer hold a public conference focused on student writing, the administration relented and said that the conference could be held, with three provisions: the words “cultural studies” could not be used to describe the conference, the event could not include both students tracked into the new program and students tracked into the old program, and no funding would be made available for an autonomous event that involved students in the old program. The Composition and Cultural Studies Conference has consequently folded, and, instead, as a 2004 article advertising the new program in the Association of American Colleges and Universities newsletter explains, GWU will now hold, each spring, a “University Writing and Research Symposium.” The AAC&U News article says nothing about the fact that students randomly tracked into the old Writing Program were forbidden to participate in the symposium, nor does it mention that the symposium replaced a vibrant antidisciplinary writing event with a six-year history. The article instead celebrated the fact that students, in a public forum, could demonstrate mastery of the forms of writing specific to their disciplines: “Students in the sciences might present poster sessions … students in business classes might use Power Point presentations.” In line with the administration’s requirement, the words “cultural studies” do not appear in the piece.19

The AAC&U News article is what Mike Davis might call a “booster” narrative (City of Quartz 24). Davis writes of the ways in which boosters and booster narratives, in the early part of the twentieth century, “set out to sell Los Angeles—as no city had ever been sold—to the restless but affluent babbitry of the Middle West” (25). The booster narratives generated for this marketing project essentially constructed Los Angeles as the land of eternal sunshine and quaint Spanish missions; Davis opens his section on boosters with an epigraph from Charles Fletcher Lummis insisting that “the missions are, next to our climate and its consequences, the best capital Southern California has” (24). Efficient productivity and profit were among the “consequences” that the intended audience of these narratives might expect, largely as a result of Los Angeles’s notorious antilabor “open shop.”

The ready availability of booster narratives in relation to the University Writing Program, more than anything else, demonstrates the ways in which those administering the new program only want “revision” that is safe, contained, composed; the corporate university, in other words, seeks immunity from authentic revision, from writing generated by unruly queer/crip subjectivities, from de-composition. This is evidenced by the fact that the booster narrative must not be revised; in repetitive language at times stunningly similar to the language Davis associates with efforts to sell Los Angeles, the University Writing Program’s booster narrative—always yearning for an identifiable finished product—has been made public: “Our goal is to produce the best writing program in the country.… We expect to say, with no hesitation, that when you graduate from GW, you will be able to write well and that others will recognize this capability in you—that writing competency is an essential characteristic of a GW education” (Ewald 3). There are no missions on GWU’s campus (though, ironically, one academic building is in fact located in a former church that is architecturally reminiscent of a Spanish-style mission), but it’s always sunny—and always will be—according to the new program’s (master) booster narrative. Storms are brewing, however, anywhere and everywhere that the corporate university generates contradictions like the one I am teasing out in this paragraph: revision is mandated, revision is forbidden. The production of producers within that contradictory—literally impossible and unlivable—context is bound to generate unexpected revisions. The new program will inevitably de-compose.

Although clearly the will to a finished—and marketable—product is strong, the future of writing instruction nonetheless remains contested at GWU, which is actually located (paradoxically, as far as the sunshine of boosterism is concerned) in the neighborhood of Washington, D.C., known as “Foggy Bottom.” Many of the faculty hired for the new University Writing Program formerly held positions in the old, and although they have been shut out of many key decisions (particularly around hiring and assessment), they have managed to secure some victories, most notably a small class size (fifteen students) and courses that largely remain focused on cultural studies topics, even if the language of cultural studies has been conjured away by some who are heavily invested in the new program. Specters of disability and queerness have appeared at the margins of the new program, and how those specters will affect its current corporeality remains to be seen. The faculty in the new program includes at least one nationally recognized scholar in disability studies, whose current work, notably, centers on disability movements resisting conceptions of “diagnosis.” Courses in the new program have already included one focused on freak shows and another on sexuality, identity, and anxiety.20 Such work, however, is arguably viewed with a great deal of suspicion by those invested in a particular and contained view of writing at GWU, and some candidates for positions in the new program whose work is directly in queer or disability studies have been perceived as having an “agenda” (and have, consequently, not been hired).

As I draw attention to anything positive or generative about the preservation of some queer, disability, and cultural studies content even as the program more explicitly dedicated to a cultural studies pedagogy was dismantled, it could be said that I’m fiddling as Foggy Bottom burns, or—more directly—that I’m not comprehending what Thomas Frank calls the “conquest of cool” as it operates in neoliberalism generally and in and around cultural studies in particular. Topic-based composition courses, in other words, could be read as integral to the corporate university, not as forces potentially opposing it. In my mind, however, such a conclusion (while in some ways true—the corporate university will incorporate topic-based courses, along with any other kind of course, into its strategic plans for excellence) gives up on writing and forgets what Hall argues about the ways that cultural hegemony works. According to Hall: “Cultural hegemony is never about pure victory or pure domination (that’s not what the term means); it is never a zero-sum cultural game; it is always about shifting the balance of power in relations of culture; it is always about changing the dispositions and the configurations of cultural power, not getting out of it” (“What Is This ‘Black’?” 468). Hall’s formulation suggests that processes of de-composition always pose dangers in and for the corporate university. Recognizing—and indeed teaching—that means not ceding to the right a skill worth having and sharing with others: the capacity for continually linking questions of identity to questions of political economy. This chapter (and this book) are part of a much larger and collective pedagogical effort to claim queer and crip sites where those linkages can be forged and can work against the current neoliberal order of things.

Certainly in this chapter I intend to position queer theory and disability studies at the center of composition theory, and in the interests of such a project, my highlighting of the ways in which disabled/queer questions and issues, or de-composing processes, haunt the newly composed program is intended to affirm, in the face of dangerous transitions, what Paulo Freire called “a pedagogy of freedom.” But I do not centralize disability studies and queer theory in order to offer them, somehow, as the “solution” for either a localized or more general crisis in composition; queer theory and disability studies in and of themselves will not magically revitalize a sometimes-tendentious and often-beleaguered field. I am nonetheless hopeful that disability studies and queer theory will remain locations from which we might speak back to straight composition, with its demand for composed and docile texts, skills, and bodies. Despite that hope, and with the transitions at my own institution in mind, I recognize that composition programs are currently heavily policed locations and that the demand for order and efficiency remains pronounced—mainly because that demand and the practices that result from it serve very specific material interests. Crip and queer theory, however, do provide us with ways of comprehending how our very bodies are caught up in, or even produced by, straight composition. More important, with their connection to embodied, de-composing movements both outside and inside the academy, they simultaneously continue to imagine or envision a future horizon beyond straight composition, in all its forms.