Information for Healthcare Professionals

Current Interim Guidance

• Interim Guidance for Public Health Personnel Evaluating Persons Under Investigation (PUIs) and Asymptomatic Close Contacts of Confirmed Cases at Their Home or Non-Home Residential Settings

• Interim Guidance for Collection and Submission of Postmortem Specimens from Deceased Persons Under Investigation (PUI) for COVID-19, February 2020

• Evaluating and Reporting Persons Under Investigation (PUI)

• Healthcare Infection Control Guidance

• Clinical Care Guidance

• Home Care Guidance

• Guidance for EMS

• Healthcare Personnel with Potential Exposure Guidance

• Inpatient Obstetric Healthcare Guidance

Persons Under Investigation (PUI)

• Interim Guidance for Public Health Personnel Evaluating Persons Under Investigation (PUIs) and Asymptomatic Close Contacts of Confirmed Cases at Their Home or Non-Home Residential Settings

• Evaluating and Reporting PUI Guidance

• Reporting a PUI or Laboratory-Confirmed Case for COVID-19

• Clinical Care Guidance

• Disposition of Hospitalized Patients with COVID-2019

• Inpatient Obstetric Healthcare Guidance

Supply of Personal Protective Equipment

• Implementing Home Care of People Not Requiring Hospitalization

• Preventing COVID-19 from Spreading in Homes and Communities Disposition of Non-Hospitalized Patients with COVID-19

Webinar for Healthcare Professionals

Strategies for Healthcare Systems Preparedness and Optimizing N95 Supplies.

Find more information on supplies of personal protective equipment

View presentation slides

Evaluating and Testing Persons for Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)

Summary of Recent Changes

Revisions were made on March 9, 2020, to reflect the following:

• Reorganized the Criteria to Guide Evaluation and Laboratory Testing for COVID-19 section

Revisions were made on March 4, 2020, to reflect the following:

• Criteria for evaluation of persons for testing for COVID-19 were expanded to include a wider group of symptomatic patients.

Limited information is available to characterize the spectrum of clinical illness associated with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). No vaccine or specific treatment for COVID-19 is available; care is supportive.

The CDC clinical criteria for considering testing for COVID-19 have been developed based on what is known about COVID-19 and are subject to change as additional information becomes available.

This is an official CDC Health Update

Update and Interim Guidance on Outbreak of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)

CDC continues to closely monitor an outbreak of respiratory illness caused by COVID-19 that was initially detected in Wuhan City, Hubei Province, China. This HAN Update provides a situational update and guidance to state and local health departments and health care providers.

Contact your local or state health department

Healthcare providers should immediately notify their local or state health department in the event of the identification of a PUI for COVID-19. When working with your local or state health department check their available hours.

Criteria to Guide Evaluation and Laboratory Testing for COVID-19

Clinicians should continue to work with their local and state health departments to coordinate testing through public health laboratories. In addition, COVID-19 diagnostic testing, authorized by the Food and Drug Administration under an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA), is becoming available in clinical laboratories. This additional testing capacity will allow clinicians to consider COVID-19 testing for a wider group of symptomatic patients.

Clinicians should use their judgment to determine if a patient has signs and symptoms compatible with COVID-19 and whether the patient should be tested. Most patients with confirmed COVID-19 have developed fever1 and/or symptoms of acute respiratory illness (e.g., cough, difficulty breathing). Priorities for testing may include:

1. Hospitalized patients who have signs and symptoms compatible with COVID-19 in order to inform decisions related to infection control.

2. Other symptomatic individuals such as, older adults and individuals with chronic medical conditions and/or an immunocompromised state that may put them at higher risk for poor outcomes (e.g., diabetes, heart disease, receiving immunosuppressive medications, chronic lung disease, chronic kidney disease).

3. Any persons including healthcare personnel2, who within 14 days of symptom onset had close contact3 with a suspect or laboratory-confirmed4 COVID-19 patient, or who have a history of travel from affected geographic areas5 (see below) within 14 days of their symptom onset.

There are epidemiologic factors that may also help guide decisions about COVID-19 testing. Documented COVID-19 infections in a jurisdiction and known community transmission may contribute to an epidemiologic risk assessment to inform testing decisions. Clinicians are strongly encouraged to test for other causes of respiratory illness (e.g., influenza).

Mildly ill patients should be encouraged to stay home and contact their healthcare provider by phone for guidance about clinical management. Patients who have severe symptoms, such as difficulty breathing, should seek care immediately. Older patients and individuals who have underlying medical conditions or are immunocompromised should contact their physician early in the course of even mild illness.

Recommendations for Reporting, Testing, and Specimen Collection

Clini1cians should immediately implement recommended infection prevention and control practices if a patient is suspected of having COVID-19. They should also notify infection control personnel at their healthcare facility and their state or local health department if a patient is classified as a PUI for COVID-19. State health departments that have identified a PUI or a laboratory-confirmed case should complete a PUI and Case Report form through the processes identified on CDC’s Coronavirus Disease 2019 website. State and local health departments can contact CDC’s Emergency Operations Center (EOC) at 770-488-7100 for assistance with obtaining, storing, and shipping appropriate specimens to CDC for testing, including after hours or on weekends or holidays.

For initial diagnostic testing for COVID-19, CDC recommends collecting and testing upper respiratory tract specimens (nasopharyngeal AND oropharyngeal swabs). CDC also recommends testing lower respiratory tract specimens, if available. For patients who develop a productive cough, sputum should be collected and tested for COVID-19. The induction of sputum is not recommended. For patients for whom it is clinically indicated (e.g., those receiving invasive mechanical ventilation), a lower respiratory tract aspirate or bronchoalveolar lavage sample should be collected and tested as a lower respiratory tract specimen. Specimens should be collected as soon as possible once a PUI is identified, regardless of the time of symptom onset. See Interim Guidelines for Collecting, Handling, and Testing Clinical Specimens from Patients Under Investigation (PUIs) for COVID-19 and Biosafety FAQs for handling and processing specimens from suspected cases and PUIs.

Interim Guidance for Collection and Submission of Postmortem Specimens from Deceased Persons Under Investigation (PUI) for COVID-19, February 2020

State and local health departments who have identified a Persons Under Investigation (PUI) should immediately notify CDC’s Emergency Operations Center (EOC) at 770-488-7100 to report a deceased PUI and determine whether testing for SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, at CDC is indicated. The EOC will assist local/state health departments to collect, store, and ship specimens appropriately to CDC, including during afterhours or on weekends/holidays.

CDC is available for urgent consultation in the event that an autopsy on a COVID-19 PUI is being considered. CDC can be reached for urgent consultation by calling the EOC at 770-488-7100.

This interim guidance is based on what is currently known about COVID-19. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) will update this interim guidance as needed and as additional information becomes available.

The CDC is closely monitoring an outbreak of respiratory illness caused by a novel (new) coronavirus (named SARS-CoV-2); this illness is now called coronavirus disease 2019 or COVID-19. This virus was first identified in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China and it continues to spread. CDC is working across the Department of Health and Human Services and other parts of the U.S. government in the public health response to COVID-19.

Much is unknown about COVID-19. Current knowledge is largely based on what is known about similar coronaviruses. Coronaviruses are a large family of viruses that are common in many different species of animals, including camels, cattle, cats, and bats. Rarely, animal coronaviruses can infect people and then spread between people such as with MERS-CoV, SARS-CoV, and now with SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. Most often, spread from a living person happens with close contact (i.e., within about 6 feet) via respiratory droplets produced when an infected person coughs or sneezes, similar to how influenza and other respiratory pathogens spread. This route of transmission is not a concern when handling human remains or performing postmortem procedures. Postmortem activities should be conducted with a focus on avoiding aerosol generating procedures, and ensuring that if aerosol generation is likely (e.g., when using an oscillating saw) that appropriate engineering controls and personal protective equipment (PPE) are used. These precautions and the use of Standard Precautions should ensure that appropriate work practices are used to prevent direct contact with infectious material, percutaneous injury, and hazards related to moving heavy remains and handling embalming chemicals.

This document provides specific guidance for the collection and submission of postmortem specimens from deceased persons under investigation (PUI) for COVID-19. This document also provides recommendations for biosafety and infection control practices during specimen collection and handling, including during autopsy procedures. The guidance can be utilized by medical examiners, coroners, pathologists, other workers involved in the postmortem care of deceased PUI, and local and state health departments.

The following factors should be considered when determining if an autopsy will be performed for a deceased PUI: medicolegal jurisdiction, facility environmental controls, availability of recommended personal protective equipment (PPE), and family and cultural wishes.

If an autopsy is performed, collection of the following postmortem specimens is recommended:

• Postmortem clinical specimens for testing for SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19:

○ Upper respiratory tract swabs: Nasopharyngeal Swab AND Oropharyngeal Swab (NP swab and OP swab)

○ Lower respiratory tract swab: Lung swab from each lung

• Separate clinical specimens for testing of other respiratory pathogens and other postmortem testing as indicated

• Formalin-fixed autopsy tissues from lung, upper airway, and other major organs

If an autopsy is NOT performed, collection of the following postmortem specimens is recommended:

• Postmortem clinical specimens for testing for SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, to include only upper respiratory tract swabs: Nasopharyngeal Swab AND Oropharyngeal Swab (NP swab and OP swab)

• Separate NP swab and OP swab specimens for testing of other respiratory pathogens

Detailed guidance for postmortem specimen collection can be found in the section: Collection of Postmortem Clinical and Pathologic Specimens.

In addition to postmortem specimens, submission of any remaining clinical specimens (e.g., NP swab, OP swab, sputum, serum, stool) that may have been collected prior to death is recommended. Please refer to Interim Guidelines for Collecting, Handling, and Testing Clinical Specimens from Persons Under Investigation (PUIs) for Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) for more information.

Recommended Biosafety and Infection Control Practices

Collection of Postmortem Upper Respiratory Tract Swab Specimens

Individuals in the room during the procedure should be limited to healthcare personnel (HCP) obtaining the specimen. If HCP are not performing an autopsy or conducting aerosol generating procedures (AGPs), follow Standard Precautions.

Engineering Control Recommendations:

Since collection of nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swab specimens from deceased persons will not induce coughing or sneezing, a negative pressure room is not required. Personnel should adhere to Standard Precautions as described above.

PPE Recommendations:

The following PPE should be worn at a minimum:

• Wear nonsterile, nitrile gloves when handling potentially infectious materials.

• If there is a risk of cuts, puncture wounds, or other injuries that break the skin, wear heavy-duty gloves over the nitrile gloves.

• Wear a clean, long-sleeved fluid-resistant or impermeable gown to protect skin and clothing.

• Use a plastic face shield or a face mask and goggles to protect the face, eyes, nose, and mouth from splashes of potentially infectious bodily fluids.

Autopsy Procedures

Standard Precautions, Contact Precautions, and Airborne Precautions with eye protection (e.g., goggles or a face shield) should be followed during autopsy. Many of the following procedures are consistent with existing guidelines for safe work practices in the autopsy setting; see Guidelines for Safe Work Practices in Human and Animal Medical Diagnostic Laboratories.

• AGPs such as use of an oscillating bone saw should be avoided for confirmed or suspected cases of COVID-19. Consider using hand shears as an alternative cutting tool. If an oscillating saw is used, attach a vacuum shroud to contain aerosols.

• Allow only one person to cut at a given time.

• Limit the number of personnel working in the autopsy suite at any given time to the minimum number of people necessary to safely conduct the autopsy.

• Limit the number of personnel working on the human body at any given time.

• Use a biosafety cabinet for the handling and examination of smaller specimens and other containment equipment whenever possible.

• Use caution when handling needles or other sharps, and dispose of contaminated sharps in puncture-proof, labeled, closable sharps containers.

• A logbook including names, dates, and activities of all workers participating in the postmortem and cleaning of the autopsy suite should be kept to assist in future follow up, if necessary. Include custodian staff entering after hours or during the day.

Engineering Control Recommendations

Autopsies on decedents with known or suspected COVID-19 should be conducted in Airborne Infection Isolation Rooms (AIIRs). These rooms are at negative pressure to surrounding areas, have a minimum of 6 air changes per hour (ACH) for existing structures and 12 ACH for renovated or new structures, and have air exhausted directly outside or through a HEPA filter. Doors to the room should be kept closed except during entry and egress. If an AIIR is not available, ensure the room is negative pressure with no air recirculation to adjacent spaces. A portable HEPA recirculation unit could be placed in the room to provide further reduction in aerosols. Local airflow control (i.e., laminar flow systems) can be used to direct aerosols away from personnel. If use of an AIIR or HEPA unit is not possible, the procedure should be performed in the most protective environment possible. Air should never be returned to the building interior, but should be exhausted outdoors, away from areas of human traffic or gathering spaces and away from other air intake systems.

PPE Recommendations:

The following PPE should be worn during autopsy procedures:

• Double surgical gloves interposed with a layer of cut-proof synthetic mesh gloves

• Fluid-resistant or impermeable gown

• Waterproof apron

• Goggles or face shield

• NIOSH-certified disposable N-95 respirator or higher

○ Powered, air-purifying respirators (PAPRs) with HEPA filters may provide increased worker comfort during extended autopsy procedures.

○ When respirators are necessary to protect workers, employers must implement a comprehensive respiratory protection program in accordance with the OSHA Respiratory Protection standard (29 CFR 1910.134) that includes medical exams, fit-testing, and training.

Surgical scrubs, shoe covers, and surgical cap should be used per routine protocols. Doff (take off) PPE carefully to avoid contaminating yourself and before leaving the autopsy suite or adjacent anteroom (https://www.cdc.gov/hai/pdfs/ppe/ppe-sequence.pdf).

After removing PPE, discard the PPE in the appropriate laundry or waste receptacle. Reusable PPE (e.g., goggles, face shields, and PAPRs) must be cleaned and disinfected according to the manufacturer’s recommendations before reuse. Immediately after doffing PPE, wash hands with soap and water for 20 seconds. If hands are not visibly dirty and soap and water are not available, an alcohol-based hand sanitizer that contains 60%-95% alcohol may be used. However, if hands are visibly dirty, always wash hands with soap and water before using alcohol-based hand sanitizer. Avoid touching the face with gloved or unwashed hands. Ensure that hand hygiene facilities are readily available at the point of use (e.g., at or adjacent to the PPE doffing area).

Additional safety and health guidance is available for workers handling deceased persons under investigation (PUI) for COVID-19 at the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), COVID-19 website.

Collection of Postmortem Clinical and Pathologic Specimens

Implementing proper biosafety and infection control practices is critical when collecting specimens. Please refer to Interim Laboratory Biosafety Guidelines for Handling and Processing Specimens Associated with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) for additional information.

Collection of Postmortem Clinical Specimens for SARS-CoV-2 Testing

CDC recommends collecting and testing postmortem upper respiratory specimens (nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swabs) and, if an autopsy is performed, lower respiratory specimens (lung swabs).

Use only synthetic fiber swabs with plastic shafts. Do not use calcium alginate swabs or swabs with wooden shafts, as they may contain substances that inactivate some viruses and inhibit PCR testing. Place swabs immediately into sterile tubes containing 2-3 ml of viral transport media. NP, OP, and lung swab specimens should be kept in separate vials. Refrigerate specimen at 2-8°C and ship overnight to CDC on ice pack.

Upper Respiratory Tract Specimen Collection: Nasopharyngeal Swab AND Oropharyngeal Swabs (NP swab, OP swab)

• Nasopharyngeal swab: Insert a swab into the nostril parallel to the palate. Leave the swab in place for a few seconds to absorb secretions. Swab both nasopharyngeal areas with the same swab.

• Oropharyngeal swab (e.g., throat swab): Swab the posterior pharynx, avoiding the tongue.

Lower respiratory tract: Lung swabs

• Collect one swab from each lung.

Collection of Postmortem Clinical Specimens for Other Routine Diagnostic Testing

Separate clinical specimens (e.g., NP swab, OP swab, lung swabs) should be collected for routine testing of respiratory pathogens at either clinical or public health labs. Note that clinical laboratories should NOT attempt viral isolation from specimens collected from COVID-19 PUIs.

Other postmortem specimen collection and evaluations should be directed by the decedent’s clinical and exposure history, scene investigation, and gross autopsy findings, and may include routine bacterial cultures, toxicology, and other studies as indicated.

Collection of Fixed Autopsy Tissue Specimens

The preferred specimens would be a minimum of eight blocks and fixed tissue specimens representing samples from the respiratory sites listed below in addition to specimens from major organs (including liver, spleen, kidney, heart, GI tract) and any other tissues showing significant gross pathology.

The recommended respiratory sites include:

1. Trachea (proximal and distal)

2. Central (hilar) lung with segmental bronchi, right and left primary bronchi

3. Representative pulmonary parenchyma from right and left lung

Viral antigens and nucleic acid may be focal or sparsely distributed in patients with respiratory viral infections and are most frequently detected in respiratory epithelium of large airways. For example, larger airways (particularly primary and segmental bronchi) have the highest yield for detection of respiratory viruses by molecular testing and immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining. Performance of specific immunohistochemical, molecular, or other assays will be determined using clinical and epidemiologic information provided by the submitter and the histopathologic features identified in the submitted tissue specimens.

Collection of tissue samples roughly 4-5 mm in thickness (i.e., sample would fit in a tissue cassette) is recommended for optimal fixation. The volume of formalin used to fix tissues should be 10x the volume of tissue. Place tissue in 10% buffered formalin for three days (72 hours) for optimal fixation.

Safely Preparing the Specimens for Shipment

After collecting and properly securing and labeling specimens in primary containers with the appropriate media/solution, they must be transferred from the autopsy suite in a safe manner to laboratory staff who can process them for shipping.

1. Within the autopsy suite, primary containers should be placed into a larger secondary container.

2. If possible, the secondary container should then be placed into a resealable plastic bag that was not in the autopsy suite when the specimens were collected.

3. The resealable plastic bag should then be placed into a biological specimen bag with absorbent material; and then can be transferred outside of the autopsy suite.

a. Workers receiving the biological specimen bag outside the autopsy suite or anteroom should wear disposable nitrile gloves.

Submission of Specimens to CDC

State and local health departments who have identified a PUI should immediately notify CDC’s Emergency Operations Center (EOC) at 770-488-7100 to report a deceased PUI and determine whether SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, testing at CDC is indicated. The EOC will assist local/state health departments to collect, store, and ship specimens appropriately to CDC, including during afterhours or on weekends/holidays.

Submission of Postmortem Clinical Specimens for SARS-CoV-2 Testing

This section applies to submission of postmortem NP swab, OP swab, and lung swabs

• Store specimens at 2-8°C and ship overnight to CDC on ice pack.

• Label each specimen container with the patient’s ID number (e.g., medical record number), unique specimen ID (e.g., laboratory requisition number), specimen type (e.g., tissue), and the date the sample was collected.

• Complete a CDC Form 50.34 for each specimen submitted.

• In the upper left box of the form provide the following: (1) for test requested select “Respiratory virus molecular detection (non-influenza) CDC-10401” and (2) for At CDC, bring to the attention of enter “Stephen Lindstrom: 2019-nCoV PUI – Autopsy specimens”.

Clinical specimens from COVD-19 PUIs must be packaged, shipped, and transported according to the current edition of the International Air Transport Association (IATA) Dangerous Goods Regulations. Store specimens at 2-8°C and ship overnight to CDC on ice pack. If a specimen is frozen at -70°C ship overnight to CDC on dry ice. Additional useful and detailed information on packing, shipping, and transporting specimens can be found at Interim Laboratory Biosafety Guidelines for Handling and Processing Specimens Associated with Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19).

Submission of Fixed Autopsy Tissue Specimens

CDC’s Infectious Diseases Pathology Branch will perform histopathologic evaluation; testing for SARS-CoV-2, as well as other respiratory viral pathogens (e.g., influenza); and bacterial and other infections, as indicated.

Paraffin-embedded tissue blocks

In general, this is the preferred specimen and is especially important to submit in cases where tissues have been in formalin for a significant time. Prolonged fixation (>2 weeks) may interfere with some immunohistochemical and molecular diagnostic assays.

Wet tissue

If available, we highly recommend that unprocessed tissues in 10% neutral buffered formalin be submitted in addition to paraffin blocks.

Requirements for submitting fixed tissues to CDC

A. Contact CDC’s Infectious Diseases Pathology Branch at pathology@cdc.gov who will provide a pre-populated CDC Form 50.34 for your convenience. Include in the email:

1. A brief clinical history

2. A description of gross or histopathologic findings in the tissues to be submitted

B. After you receive email approval from pathology@cdc.gov:

1. Electronically fill, save, and print both pages of the CDC Form 50.34.

2. In the upper left box of the form, Select Test Order Code CDC-10365 (“Pathologic Evaluation of Tissues for Possible Infectious Etiologies”)

3. Enter “COVID-19 PUI” and provide any applicable CDC and State Case ID numbers in the Comments section on Page 2 of the CDC 50.34 form.

4. In addition to the CDC 50.34 form, enclose the following in the specimen submission package:

1. Surgical pathology, autopsy report (preliminary is acceptable), or both

2. Relevant clinical notes, including admission History and Physical (H&P), discharge summary, if applicable

C. Mailing/Contact Info:

1. Formalin-fixed wet tissues and/or formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue blocks should be shipped in suitable packaging at ambient temperature. Do not freeze fixed tissues.

2. Ship to: Dr. Sherif Zaki, CDC, IDPB, 1600 Clifton Rd NE, MS: H18-SB, Atlanta, GA 30329-4027

3. Send tracking number to pathology@cdc.gov

4. Tel: 404-639-3132, Fax: 404-639-3043, Email: pathology@cdc.gov

Cleaning and Waste Disposal Recommendations

The following are general guidelines for cleaning and waste disposal following an autopsy of a decedent with confirmed or suspected COVID-19. The surface persistence of SARS-CoV-2 is uncertain at this time. Other coronaviruses such as those that cause MERS and SARS can persist on nonporous surfaces for 24 hours or more.

Routine cleaning and disinfection procedures (e.g., using cleaners and water to pre-clean surfaces prior to applying an Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)-registered, hospital-grade disinfectant for appropriate contact times as indicated on the product’s label) are appropriate for COVID-19 in these settings.

After an autopsy of a decedent with confirmed or suspected COVID-19, the following recommendations apply for the autopsy room (and anteroom if applicable):

• Keep ventilation systems active while cleaning is conducted.

• Wear disposable gloves recommended by the manufacturer of the cleaner or disinfectant while cleaning and when handling cleaning or disinfecting solutions.

○ Dispose of gloves if they become damaged or soiled and when cleaning is completed, as described below. Never wash or reuse gloves.

• Use eye protection, such as a faceshield or goggles, if splashing of water, cleaner/disinfectant, or other fluids, is expected.

• Use respiratory protection if required on cleaner or disinfectant label.

• Ensure workers are trained on OSHA’s Hazard Communication standard, 29 CFR 1910.1200, to communicate with workers about the hazardous chemicals used in the workplace.

• Wear a clean, long-sleeved fluid-resistant gown to protect skin and clothing.

• Use disinfectants with EPA-approved products with label claims against human coronaviruses. All products should be used according to label instructions.

○ Clean the surface first, and then apply the disinfectant as instructed on the disinfectant manufacturer’s label. Ensure adequate contact time for effective disinfection.

○ Adhere to any safety precautions or other label recommendations as directed (e.g., allowing adequate ventilation in confined areas and proper disposal of unused product or used containers).

○ Avoid using product application methods that cause splashing or generate aerosols.

○ Cleaning activities should be supervised and inspected periodically to ensure correct procedures are followed.

• Do not use compressed air and/or water under pressure for cleaning, or any other methods that can cause splashing or might re-aerosolize infectious material.

• Gross contamination and liquids should be collected with absorbent materials, such as towels, by staff conducting the autopsy wearing designated PPE. Gross contamination and liquids should then be disposed of as described below:

○ Use of tongs and other utensils can minimize the need for personal contact with soiled absorbent materials.

○ Large areas contaminated with body fluids should be treated with disinfectant following removal of the fluid with absorbent material. The area should then be cleaned and given a final disinfection.

○ Small amounts of liquid waste (e.g., body fluids) can be flushed or washed down ordinary sanitary drains without special procedures.

○ Hard, nonporous surfaces may then be cleaned and disinfected as described above.

• Follow standard operating procedures for the containment and disposal of used PPE and regulated medical waste. SARS-CoV-2 is not considered a Category A infectious substance. State and local governments should be consulted for appropriate disposal decisions.

• Dispose of human tissues according to routine procedures for pathological waste.

• Clean and disinfect or autoclave non-disposable instruments using routine procedures, taking appropriate precautions with sharp objects.

• Materials or clothing that will be laundered can be removed from the autopsy suite (or anteroom, if applicable) in a sturdy, leak-proof biohazard bag that is tied shut and not reopened. These materials should then be sent for laundering according to routine procedures.

• Wash reusable, non-launderable items (e.g., aprons) with detergent solution, decontaminate using disinfectant, rinse with water, and allow items to dry before next use.

• Keep camera, telephones, computer keyboards, and other items that remain in the autopsy suite (or anteroom, if applicable) as clean as possible, but treat as if they are contaminated and handle with gloves. Wipe the items with appropriate disinfectant after use. If being removed from the autopsy suite, ensure complete decontamination with appropriate disinfectant according to the manufacturer’s recommendations prior to removal and reuse.

• When cleaning is complete and PPE has been removed, wash hands immediately with soap and water for 20 seconds. If hands are not visibly dirty and soap and water are not available, an alcohol-based hand sanitizer that contains 60%-95% alcohol may be used. However, if hands are visibly dirty, always wash hands with soap and water before using alcohol-based hand sanitizer. Avoid touching the face with gloved or unwashed hands. Ensure that hand hygiene facilities are readily available at the point of use (e.g., at or adjacent to the PPE doffing area).

Transportation of Human Remains

Follow standard routine procedures when transporting the body after specimens have been collected and the body has been bagged. Disinfect the outside of the bag with an EPA-registered hospital disinfectant applied according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Wear disposable nitrile gloves when handling the body bag.

Interim Guidance for Emergency Medical Services (EMS) Systems and 911 Public Safety Answering Points (PSAPs) for COVID-19 in the United States

This guidance applies to all first responders, including law enforcement, fire services, emergency medical services, and emergency management officials, who anticipate close contact with persons with confirmed or possible COVID-19 in the course of their work.

Summary of Key Changes for the EMS Guidance:

• Updated PPE recommendations for the care of patients with known or suspected COVID-19:

○ Facemasks are an acceptable alternative until the supply chain is restored. Respirators should be prioritized for procedures that are likely to generate respiratory aerosols, which would pose the highest exposure risk to HCP.

○ Eye protection, gown, and gloves continue to be recommended.

■ If there are shortages of gowns, they should be prioritized for aerosol-generating procedures, care activities where splashes and sprays are anticipated, and high-contact patient care activities that provide opportunities for transfer of pathogens to the hands and clothing of HCP.

○ When the supply chain is restored, fit-tested EMS clinicians should return to use of respirators for patients with known or suspected COVID-19.

• Updated guidance about recommended EPA-registered disinfectants to include reference to a list now posted on the EPA website.

Background

Emergency medical services (EMS) play a vital role in responding to requests for assistance, triaging patients, and providing emergency medical treatment and transport for ill persons. However, unlike patient care in the controlled environment of a healthcare facility, care and transports by EMS present unique challenges because of the nature of the setting, enclosed space during transport, frequent need for rapid medical decision-making, interventions with limited information, and a varying range of patient acuity and jurisdictional healthcare resources.

When preparing for and responding to patients with confirmed or possible coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), close coordination and effective communications are important among 911 Public Safety Answering Points (PSAPs)— commonly known as 911 call centers, the EMS system, healthcare facilities, and the public health system. Each PSAP and EMS system should seek the involvement of an EMS medical director to provide appropriate medical oversight. For the purposes of this guidance, “EMS clinician” means prehospital EMS and medical first responders. When COVID-19 is suspected in a patient needing emergency transport, prehospital care providers and healthcare facilities should be notified in advance that they may be caring for, transporting, or receiving a patient who may have COVID-19 infection.

Updated information about COVID-19 may be accessed at https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/index.html. Infection prevention and control recommendations can be found here: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-nCoV/hcp/infection-control.html. Additional information for healthcare personnel can be found at https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-nCoV/guidance-hcp.html.

Case Definition for COVID-19

CDC’s most current case definition for a person under investigation (PUI) for COVID-19 may be accessed at https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-nCoV/clinical-criteria.html.

Recommendations for 911 PSAPs

Municipalities and local EMS authorities should coordinate with state and local public health, PSAPs, and other emergency call centers to determine need for modified caller queries about COVID-19, outlined below.

Development of these modified caller queries should be closely coordinated with an EMS medical director and informed by local, state, and federal public health authorities, including the city or county health department(s), state health department(s), and CDC.

Modified Caller Queries

PSAPs or Emergency Medical Dispatch (EMD) centers (as appropriate) should question callers and determine the possibility that this call concerns a person who may have signs or symptoms and risk factors for COVID-19. The query process should never supersede the provision of pre-arrival instructions to the caller when immediate lifesaving interventions (e.g., CPR or the Heimlich maneuver) are indicated. Patients in the United States who meet the appropriate criteria should be evaluated and transported as a PUI. Information on COVID-19 will be updated as the public health response proceeds. PSAPs and medical directors can access CDC’s PUI definitions here.

Information on a possible PUI should be communicated immediately to EMS clinicians before arrival on scene in order to allow use of appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE). PSAPs should utilize medical dispatch procedures that are coordinated with their EMS medical director and with the local or state public health department.

PSAPs and EMS units that respond to ill travelers at US international airports or other ports of entry to the United States (maritime ports or border crossings) should be in contact with the CDC quarantine station of jurisdiction for the port of entry (see: CDC Quarantine Station Contact List) for planning guidance. They should notify the quarantine station when responding to that location if a communicable disease is suspected in a traveler. CDC has provided job aids for this purpose to EMS units operating routinely at US ports of entry. The PSAP or EMS unit can also call CDC’s Emergency Operations Center at (770) 488-7100 to be connected with the appropriate CDC quarantine station.

Recommendations for EMS Clinicians and Medical First Responders

EMS clinician practices should be based on the most up-to-date COVID-19 clinical recommendations and information from appropriate public health authorities and EMS medical direction.

State and local EMS authorities may direct EMS clinicians to modify their practices as described below.

Patient assessment

• If PSAP call takers advise that the patient is suspected of having COVID-19, EMS clinicians should put on appropriate PPE before entering the scene. EMS clinicians should consider the signs, symptoms, and risk factors of COVID-19 (https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-nCoV/clinical-criteria.html).

• If information about potential for COVID-19 has not been provided by the PSAP, EMS clinicians should exercise appropriate precautions when responding to any patient with signs or symptoms of a respiratory infection. Initial assessment should begin from a distance of at least 6 feet from the patient, if possible. Patient contact should be minimized to the extent possible until a facemask is on the patient. If COVID-19 is suspected, all PPE as described below should be used. If COVID-19 is not suspected, EMS clinicians should follow standard procedures and use appropriate PPE for evaluating a patient with a potential respiratory infection.

• A facemask should be worn by the patient for source control. If a nasal cannula is in place, a facemask should be worn over the nasal cannula. Alternatively, an oxygen mask can be used if clinically indicated. If the patient requires intubation, see below for additional precautions for aerosol-generating procedures.

• During transport, limit the number of providers in the patient compartment to essential personnel to minimize possible exposures.

Recommended Personal Protective Equipment (PPE)

• EMS clinicians who will directly care for a patient with possible COVID-19 infection or who will be in the compartment with the patient should follow Standard, Precautions and use the PPE as described below. Recommended PPE includes:

○ N-95 or higher-level respirator or facemask (if a respirator is not available),

■ N95 respirators or respirators that offer a higher level of protection should be used instead of a facemask when performing or present for an aerosol-generating procedure

○ Eye protection (i.e., goggles or disposable face shield that fully covers the front and sides of the face). Personal eyeglasses and contact lenses are NOT considered adequate eye protection.

○ A single pair of disposable patient examination gloves. Change gloves if they become torn or heavily contaminated, and isolation gown.,

■ If there are shortages of gowns, they should be prioritized for aerosol-generating procedures, care activities where splashes and sprays are anticipated, and high-contact patient care activities that provide opportunities for transfer of pathogens to the hands and clothing of EMS clinicians (e.g., moving patient onto a stretcher).

• When the supply chain is restored, fit-tested EMS clinicians should return to use of respirators for patients with known or suspected COVID-19.

• Drivers, if they provide direct patient care (e.g., moving patients onto stretchers), should wear all recommended PPE. After completing patient care and before entering an isolated driver’s compartment, the driver should remove and dispose of PPE and perform hand hygiene to avoid soiling the compartment.

○ If the transport vehicle does not have an isolated driver’s compartment, the driver should remove the face shield or goggles, gown and gloves and perform hand hygiene. A respirator or facemask should continue to be used during transport.

• All personnel should avoid touching their face while working.

• On arrival, after the patient is released to the facility, EMS clinicians should remove and discard PPE and perform hand hygiene. Used PPE should be discarded in accordance with routine procedures.

• Other required aspects of Standard Precautions (e.g., injection safety, hand hygiene) are not emphasized in this document but can be found in the guideline titled Guideline for Isolation Precautions: Preventing Transmission of Infectious Agents in Healthcare Settings.

Precautions for Aerosol-Generating Procedures

• If possible, consult with medical control before performing aerosol-generating procedures for specific guidance.

• An N-95 or higher-level respirator, instead of a facemask, should be worn in addition to the other PPE described above, for EMS clinicians present for or performing aerosol-generating procedures.,

• EMS clinicians should exercise caution if an aerosol-generating procedure (e.g., bag valve mask (BVM) ventilation, oropharyngeal suctioning, endotracheal intubation, nebulizer treatment, continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), bi-phasic positive airway pressure (biPAP), or resuscitation involving emergency intubation or cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR)) is necessary.

○ BVMs, and other ventilatory equipment, should be equipped with HEPA filtration to filter expired air.

○ EMS organizations should consult their ventilator equipment manufacturer to confirm appropriate filtration capability and the effect of filtration on positive-pressure ventilation.

• If possible, the rear doors of the transport vehicle should be opened and the HVAC system should be activated during aerosol-generating procedures. This should be done away from pedestrian traffic.

EMS Transport of a PUI or Patient with Confirmed COVID-19 to a Healthcare Facility (including interfacility transport)

If a patient with an exposure history and signs and symptoms suggestive of COVID-19 requires transport to a healthcare facility for further evaluation and management (subject to EMS medical direction), the following actions should occur during transport:

• EMS clinicians should notify the receiving healthcare facility that the patient has an exposure history and signs and symptoms suggestive of COVID-19 so that appropriate infection control precautions may be taken prior to patient arrival.

• Keep the patient separated from other people as much as possible.

• Family members and other contacts of patients with possible COVID-19 should not ride in the transport vehicle, if possible. If riding in the transport vehicle, they should wear a facemask.

• Isolate the ambulance driver from the patient compartment and keep pass-through doors and windows tightly shut.

• When possible, use vehicles that have isolated driver and patient compartments that can provide separate ventilation to each area.

○ Close the door/window between these compartments before bringing the patient on board.

○ During transport, vehicle ventilation in both compartments should be on non-recirculated mode to maximize air changes that reduce potentially infectious particles in the vehicle.

○ If the vehicle has a rear exhaust fan, use it to draw air away from the cab, toward the patient-care area, and out the back end of the vehicle.

○ Some vehicles are equipped with a supplemental recirculating ventilation unit that passes air through HEPA filters before returning it to the vehicle. Such a unit can be used to increase the number of air changes per hour (ACH) (https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/hhe/reports/pdfs/1995-0031-2601.pdf).

• If a vehicle without an isolated driver compartment and ventilation must be used, open the outside air vents in the driver area and turn on the rear exhaust ventilation fans to the highest setting. This will create a negative pressure gradient in the patient area.

• Follow routine procedures for a transfer of the patient to the receiving healthcare facility (e.g., wheel the patient directly into an examination room).

Documentation of patient care

• Documentation of patient care should be done after EMS clinicians have completed transport, removed their PPE, and performed hand hygiene.

○ Any written documentation should match the verbal communication given to the emergency department providers at the time patient care was transferred.

• EMS documentation should include a listing of EMS clinicians and public safety providers involved in the response and level of contact with the patient (for example, no contact with patient, provided direct patient care). This documentation may need to be shared with local public health authorities.

Cleaning EMS Transport Vehicles after Transporting a PUI or Patient with Confirmed COVID-19

The following are general guidelines for cleaning or maintaining EMS transport vehicles and equipment after transporting a PUI:

• After transporting the patient, leave the rear doors of the transport vehicle open to allow for sufficient air changes to remove potentially infectious particles.

○ The time to complete transfer of the patient to the receiving facility and complete all documentation should provide sufficient air changes.

• When cleaning the vehicle, EMS clinicians should wear a disposable gown and gloves. A face shield or facemask and goggles should also be worn if splashes or sprays during cleaning are anticipated.

• Ensure that environmental cleaning and disinfection procedures are followed consistently and correctly, to include the provision of adequate ventilation when chemicals are in use. Doors should remain open when cleaning the vehicle.

• Routine cleaning and disinfection procedures (e.g., using cleaners and water to pre-clean surfaces prior to applying an EPA-registered, hospital-grade disinfectant to frequently touched surfaces or objects for appropriate contact times as indicated on the product’s label) are appropriate for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in healthcare settings, including those patient-care areas in which aerosol-generating procedures are performed.

• Products with EPA-approved emerging viral pathogens claims are recommended for use against SARS-CoV-2. Refer to List N on the EPA website for EPA-registered disinfectants that have qualified under EPA’s emerging viral pathogens program for use against SARS-CoV-2.

• Clean and disinfect the vehicle in accordance with standard operating procedures. All surfaces that may have come in contact with the patient or materials contaminated during patient care (e.g., stretcher, rails, control panels, floors, walls, work surfaces) should be thoroughly cleaned and disinfected using an EPA-registered hospital grade disinfectant in accordance with the product label.

• Clean and disinfect reusable patient-care equipment before use on another patient, according to manufacturer’s instructions.

• Follow standard operating procedures for the containment and disposal of used PPE and regulated medical waste.

• Follow standard operating procedures for containing and laundering used linen. Avoid shaking the linen.

Follow-up and/or Reporting Measures by EMS Clinicians After Caring for a PUI or Patient with Confirmed COVID-19

EMS clinicians should be aware of the follow-up and/or reporting measures they should take after caring for a PUI or patient with confirmed COVID-19:

• State or local public health authorities should be notified about the patient so appropriate follow-up monitoring can occur.

• EMS agencies should develop policies for assessing exposure risk and management of EMS personnel potentially exposed to SARS-CoV-2 in coordination with state or local public health authorities. Decisions for monitoring, excluding from work, or other public health actions for HCP with potential exposure to SARS-CoV-2 should be made in consultation with state or local public health authorities. Refer to the Interim U.S. Guidance for Risk Assessment and Public Health Management of Healthcare Personnel with Potential Exposure in a Healthcare Setting to Patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) for additional information.

• EMS agencies should develop sick-leave policies for EMS personnel that are nonpunitive, flexible, and consistent with public health guidance. Ensure all EMS personnel, including staff who are not directly employed by the healthcare facility but provide essential daily services, are aware of the sick-leave policies.

• EMS personnel who have been exposed to a patient with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 should notify their chain of command to ensure appropriate follow-up.

○ Any unprotected exposure (e.g., not wearing recommended PPE) should be reported to occupational health services, a supervisor, or a designated infection control officer for evaluation.

○ EMS clinicians should be alert for fever or respiratory symptoms (e.g., cough, shortness of breath, sore throat). If symptoms develop, they should self-isolate and notify occupational health services and/or their public health authority to arrange for appropriate evaluation.

EMS Employer Responsibilities

The responsibilities described in this section are not specific for the care and transport of PUIs or patients with confirmed COVID-19. However, this interim guidance presents an opportunity to assess current practices and verify that training and procedures are up-to-date.

• EMS units should have infection control policies and procedures in place, including describing a recommended sequence for safely donning and doffing PPE.

• Provide all EMS clinicians with job- or task-specific education and training on preventing transmission of infectious agents, including refresher training.

• Ensure that EMS clinicians are educated, trained, and have practiced the appropriate use of PPE prior to caring for a patient, including attention to correct use of PPE and prevention of contamination of clothing, skin, and environment during the process of removing such equipment.

• Ensure EMS clinicians are medically cleared, trained, and fit tested for respiratory protection device use (e.g., N95 filtering facepiece respirators), or medically cleared and trained in the use of an alternative respiratory protection device (e.g., Powered Air-Purifying Respirator, PAPR) whenever respirators are required. OSHA has a number of respiratory training videos.

• EMS units should have an adequate supply of PPE.

• Ensure an adequate supply of or access to EPA-registered hospital grade disinfectants (see above for more information) for adequate decontamination of EMS transport vehicles and their contents.

• Ensure that EMS clinicians and biohazard cleaners contracted by the EMS employer tasked to the decontamination process are educated, trained, and have practiced the process according to the manufacturer’s recommendations or the EMS agency’s standard operating procedures.

Infection Control

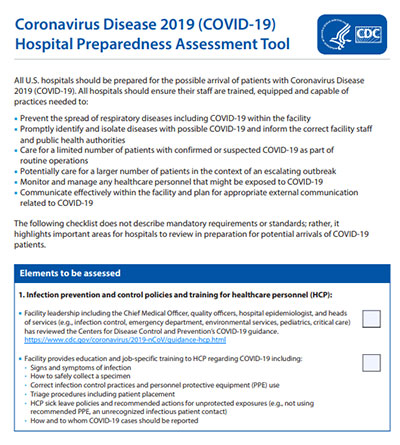

• Interim Infection Prevention and Control Recommendations for Patients with Confirmed Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) or Persons Under Investigation for COVID-19 in Healthcare Settings

• Interim Guidance for Collection and Submission of Postmortem Specimens from Deceased Persons Under Investigation (PUI) for COVID-19 (Recommended Biosafety and Infection Control Practices)

Frequently Asked Questions: Healthcare Infection Prevention and Control

Frequently Asked Questions about Personal Protective Equipment

Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) Supply Resources

• Strategies for Optimizing Supply of N95 Respirators

• Healthcare Supply of Personal Protective Equipment

• Checklist for Healthcare Facilities: Strategies for Optimizing the Supply of N95 Respirators

• Release of Stockpiled N95 Filtering Facepiece Respirators Beyond the Manufacturer-Designated Shelf Life

Interim Infection Prevention and Control Recommendations for Patients with Suspected or Confirmed Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Healthcare Settings

Summary of Changes to the Guidance:

• Updated PPE recommendations for the care of patients with known or suspected COVID-19:

○ Based on local and regional situational analysis of PPE supplies, facemasks are an acceptable alternative when the supply chain of respirators cannot meet the demand. During this time, available respirators should be prioritized for procedures that are likely to generate respiratory aerosols, which would pose the highest exposure risk to HCP.

■ Facemasks protect the wearer from splashes and sprays.

■ Respirators, which filter inspired air, offer respiratory protection.

○ When the supply chain is restored, facilities with a respiratory protection program should return to use of respirators for patients with known or suspected COVID-19. Facilities that do not currently have a respiratory protection program, but care for patients infected with pathogens for which a respirator is recommended, should implement a respiratory protection program.

○ Eye protection, gown, and gloves continue to be recommended.

■ If there are shortages of gowns, they should be prioritized for aerosol-generating procedures, care activities where splashes and sprays are anticipated, and high-contact patient care activities that provide opportunities for transfer of pathogens to the hands and clothing of HCP.

• Included are considerations for designating entire units within the facility, with dedicated HCP, to care for known or suspected COVID-19 patients and options for extended use of respirators, facemasks, and eye protection on such units. Updated recommendations regarding need for an airborne infection isolation room (AIIR).

○ Patients with known or suspected COVID-19 should be cared for in a single-person room with the door closed. Airborne Infection Isolation Rooms (AIIRs) (See definition of AIIR in appendix) should be reserved for patients undergoing aerosol-generating procedures (See Aerosol-Generating Procedures Section)

• Updated information in the background is based on currently available information about COVID-19 and the current situation in the United States, which includes reports of cases of community transmission, infections identified in healthcare personnel (HCP), and shortages of facemasks, N95 filtering facepiece respirators (FFRs) (commonly known as N95 respirators), and gowns.

○ Increased emphasis on early identification and implementation of source control (i.e., putting a face mask on patients presenting with symptoms of respiratory infection).

Healthcare Personnel (HCP)

For the purposes of this document, HCP refers to all paid and unpaid persons serving in healthcare settings who have the potential for direct or indirect exposure to patients or infectious materials, including:

• body substances

• contaminated medical supplies, devices, and equipment

• contaminated environmental surfaces

• contaminated air

Frequently Asked Questions: Healthcare Infection Prevention and Control

Background

This interim guidance has been updated based on currently available information about COVID-19 and the current situation in the United States, which includes reports of cases of community transmission, infections identified in healthcare personnel (HCP), and shortages of facemasks, N95 filtering facepiece respirators (FFRs) (commonly known as N95 respirators), and gowns. Here is what is currently known:

This guidance is applicable to all U.S. healthcare settings. This guidance is not intended for non-healthcare settings (e.g., schools) OR for persons outside of healthcare settings. For recommendations regarding clinical management, air or ground medical transport, or laboratory settings, refer to the main CDC COVID-19 website.

Mode of transmission: Early reports suggest person-to-person transmission most commonly happens during close exposure to a person infected with COVID-19, primarily via respiratory droplets produced when the infected person coughs or sneezes. Droplets can land in the mouths, noses, or eyes of people who are nearby or possibly be inhaled into the lungs of those within close proximity. The contribution of small respirable particles, sometimes called aerosols or droplet nuclei, to close proximity transmission is currently uncertain. However, airborne transmission from person-to-person over long distances is unlikely.

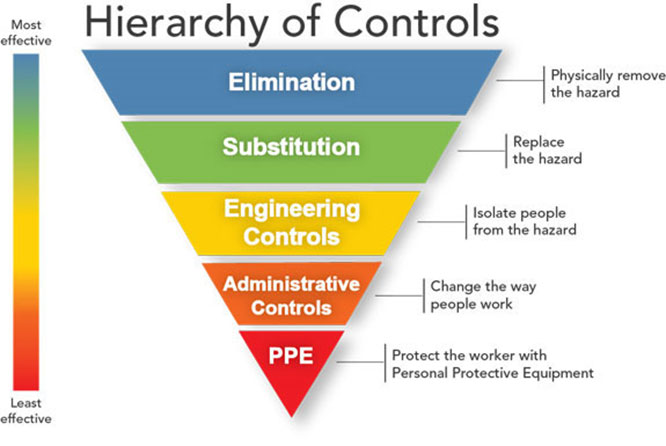

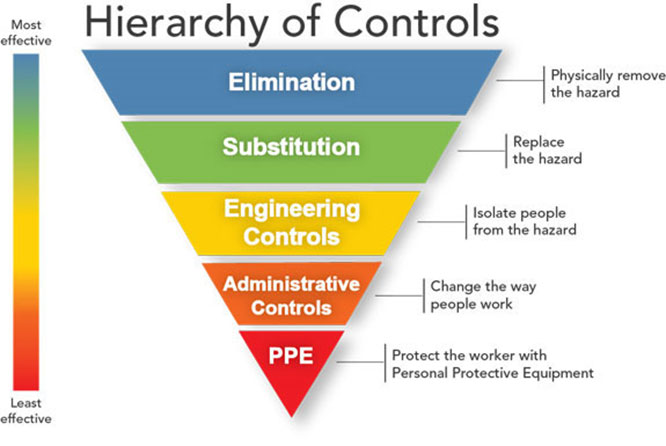

Shortage of personal protective equipment: Controlling exposures to occupational infections is a fundamental method of protecting HCP. Traditionally, a hierarchy of controls has been used as a means of determining how to implement feasible and effective control solutions. The hierarchy ranks controls according to their reliability and effectiveness and includes such controls as engineering controls, administrative controls, and ends with personal protective equipment (PPE). PPE is the least effective control because it involves a high level of worker involvement and is highly dependent on proper fit and correct, consistent use.

Major distributors in the United States have reported shortages of PPE, specifically N95 respirators, facemasks, and gowns. Healthcare facilities are responsible for protecting their HCP from exposure to pathogens, including by providing appropriate PPE.

In times of shortages, alternatives to N95s should be considered, including other classes of FFRs, elastomeric half-mask and full facepiece air purifying respirators, and powered air purifying respirators (PAPRs) where feasible. Special care should be taken to ensure that respirators are reserved for situations where respiratory protection is most important, such as performance of aerosol-generating procedures on suspected or confirmed COVID-19 patients or provision of care to patients with other infections for which respiratory protection is strongly indicated (e.g., tuberculosis, measles, varicella).

The anticipated timeline for return to routine levels of PPE is not yet known. Information about strategies to optimize the current supply of N95 respirators, including the use of devices that provide higher levels of respiratory protection (e.g., powered air purifying respirators [PAPRs]) when N95s are in limited supply and a companion checklist to help healthcare facilities prioritize the implementation of the strategies, is available.

Capacity across the healthcare continuum: Use of N95 or higher-level respirators are recommended for HCP who have been medically cleared, trained, and fit-tested, in the context of a facility’s respiratory protection program. The majority of nursing homes and outpatient clinics, including hemodialysis facilities, do not have respiratory protection programs nor have they fit-tested HCP, hampering implementation of recommendations in the previous version of this guidance. This can lead to unnecessary transfer of patients with known or suspected COVID-19 to another facility (e.g., acute care hospital) for evaluation and care. In areas with community transmission, acute care facilities will be quickly overwhelmed by transfers of patients who have only mild illness and do not require hospitalization.

Many of the recommendations described in this guidance (e.g., triage procedures, source control) should already be part of an infection control program designed to prevent transmission of seasonal respiratory infections. As it will be challenging to distinguish COVID-19 from other respiratory infections, interventions will need to be applied broadly and not limited to patients with confirmed COVID-19.

This guidance is applicable to all U.S. healthcare settings. This guidance is not intended for non-healthcare settings (e.g., schools) OR for persons outside of healthcare settings. For recommendations regarding clinical management, air or ground medical transport, or laboratory settings, refer to the main CDC COVID-19 website.

Definition of Healthcare Personnel (HCP) –For the purposes of this document, HCP refers to all paid and unpaid persons serving in healthcare settings who have the potential for direct or indirect exposure to patients or infectious materials, including body substances; contaminated medical supplies, devices, and equipment; contaminated environmental surfaces; or contaminated air.

Recommendations

1. Minimize Chance for Exposures

Ensure facility policies and practices are in place to minimize exposures to respiratory pathogens including SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. Measures should be implemented before patient arrival, upon arrival, throughout the duration of the patient’s visit, and until the patient’s room is cleaned and disinfected. It is particularly important to protect individuals at increased risk for adverse outcomes from COVID-19 (e.g. older individuals with comorbid conditions), including HCP who are in a recognized risk category.

• Before Arrival

○ When scheduling appointments for routine medical care (e.g., annual physical, elective surgery), instruct patients to call ahead and discuss the need to reschedule their appointment if they develop symptoms of a respiratory infection (e.g., cough, sore throat, fever1) on the day they are scheduled to be seen.

○ When scheduling appointments for patients requesting evaluation for a respiratory infection, use nurse-directed triage protocols to determine if an appointment is necessary or if the patient can be managed from home.

■ If the patient must come in for an appointment, instruct them to call beforehand to inform triage personnel that they have symptoms of a respiratory infection (e.g., cough, sore throat, fever1) and to take appropriate preventive actions (e.g., follow triage procedures, wear a facemask upon entry and throughout their visit or, if a facemask cannot be tolerated, use a tissue to contain respiratory secretions).

○ If a patient is arriving via transport by emergency medical services (EMS), EMS personnel should contact the receiving emergency department (ED) or healthcare facility and follow previously agreed upon local or regional transport protocols. This will allow the healthcare facility to prepare for receipt of the patient.

• Upon Arrival and During the Visit

○ Consider limiting points of entry to the facility.

○ Take steps to ensure all persons with symptoms of COVID-19 or other respiratory infection (e.g., fever, cough) adhere to respiratory hygiene and cough etiquette (see appendix), hand hygiene, and triage procedures throughout the duration of the visit.

■ Post visual alerts (e.g., signs, posters) at the entrance and in strategic places (e.g., waiting areas, elevators, cafeterias) to provide patients and HCP with instructions (in appropriate languages) about hand hygiene, respiratory hygiene, and cough etiquette. Instructions should include how to use tissues to cover nose and mouth when coughing or sneezing, to dispose of tissues and contaminated items in waste receptacles, and how and when to perform hand hygiene.

■ Provide supplies for respiratory hygiene and cough etiquette, including alcohol-based hand rub (ABHR) with 60-95% alcohol, tissues, and no-touch receptacles for disposal, at healthcare facility entrances, waiting rooms, and patient check-ins.

■ Install physical barriers (e.g., glass or plastic windows) at reception areas to limit close contact between triage personnel and potentially infectious patients.

■ Consider establishing triage stations outside the facility to screen patients before they enter.

○ Ensure rapid safe triage and isolation of patients with symptoms of suspected COVID-19 or other respiratory infection (e.g., fever, cough).

■ Prioritize triage of patients with respiratory symptoms.

■ Triage personnel should have a supply of facemasks and tissues for patients with symptoms of respiratory infection. These should be provided to patients with symptoms of respiratory infection at check-in. Source control (putting a facemask over the mouth and nose of a symptomatic patient) can help to prevent transmission to others.

■ Ensure that, at the time of patient check-in, all patients are asked about the presence of symptoms of a respiratory infection and history of travel to areas experiencing transmission of COVID-19 or contact with possible COVID-19 patients.

■ Isolate the patient in an examination room with the door closed. If an examination room is not readily available ensure the patient is not allowed to wait among other patients seeking care.

■ Identify a separate, well-ventilated space that allows waiting patients to be separated by 6 or more feet, with easy access to respiratory hygiene supplies.

■ In some settings, patients might opt to wait in a personal vehicle or outside the healthcare facility where they can be contacted by mobile phone when it is their turn to be evaluated.

○ Incorporate questions about new onset of respiratory symptoms into daily assessments of all admitted patients. Monitor for and evaluate all new fevers and respiratory illnesses among patients. Place any patient with unexplained fever or respiratory symptoms on appropriate Transmission-Based Precautions and evaluate.

Additional considerations during periods of community transmission:

○ Explore alternatives to face-to-face triage and visits.

○ Learn more about how healthcare facilities can Prepare for Community Transmission

○ Designate an area at the facility (e.g., an ancillary building or temporary structure) or identify a location in the area to be a “respiratory virus evaluation center” where patients with fever or respiratory symptoms can seek evaluation and care.

○ Cancel group healthcare activities (e.g., group therapy, recreational activities).

○ Postpone elective procedures, surgeries, and non-urgent outpatient visits.

2. Adhere to Standard and Transmission-Based Precautions

Standard Precautions assume that every person is potentially infected or colonized with a pathogen that could be transmitted in the healthcare setting. Elements of Standard Precautions that apply to patients with respiratory infections, including COVID-19, are summarized below. Attention should be paid to training and proper donning (putting on), doffing (taking off), and disposal of any PPE. This document does not emphasize all aspects of Standard Precautions (e.g., injection safety) that are required for all patient care; the full description is provided in the Guideline for Isolation Precautions: Preventing Transmission of Infectious Agents in Healthcare Settings.

HCP (see Section 5 for measures for non-HCP visitors) who enter the room of a patient with known or suspected COVID-19 should adhere to Standard Precautions and use a respirator or facemask, gown, gloves, and eye protection. When available, respirators (instead of facemasks) are preferred; they should be prioritized for situations where respiratory protection is most important and the care of patients with pathogens requiring Airborne Precautions (e.g., tuberculosis, measles, varicella). Information about the recommended duration of Transmission-Based Precautions is available in the Interim Guidance for Discontinuation of Transmission-Based Precautions and Disposition of Hospitalized Patients with COVID-19

• Hand Hygiene

○ HCP should perform hand hygiene before and after all patient contact, contact with potentially infectious material, and before putting on and after removing PPE, including gloves. Hand hygiene after removing PPE is particularly important to remove any pathogens that might have been transferred to bare hands during the removal process.

○ HCP should perform hand hygiene by using ABHR with 60-95% alcohol or washing hands with soap and water for at least 20 seconds. If hands are visibly soiled, use soap and water before returning to ABHR.

○ Healthcare facilities should ensure that hand hygiene supplies are readily available to all personnel in every care location.

• Personal Protective Equipment

• Employers should select appropriate PPE and provide it to HCP in accordance with OSHA PPE standards (29 CFR 1910 Subpart I). HCP must receive training on and demonstrate an understanding of:

○ when to use PPE

○ what PPE is necessary

○ how to properly don, use, and doff PPE in a manner to prevent self-contamination

○ how to properly dispose of or disinfect and maintain PPE

○ the limitations of PPE.

Any reusable PPE must be properly cleaned, decontaminated, and maintained after and between uses. Facilities should have policies and procedures describing a recommended sequence for safely donning and doffing PPE. The PPE recommended when caring for a patient with known or suspected COVID-19 includes:

○ Respirator or Facemask

■ Put on a respirator or facemask (if a respirator is not available) before entry into the patient room or care area.

■ N95 respirators or respirators that offer a higher level of protection should be used instead of a facemask when performing or present for an aerosol-generating procedure (See Section 4). See appendix for respirator definition. Disposable respirators and facemasks should be removed and discarded after exiting the patient’s room or care area and closing the door. Perform hand hygiene after discarding the respirator or facemask. For guidance on extended use of respirators, refer to Strategies to Optimize the Current Supply of N95 Respirators

■ If reusable respirators (e.g., powered air purifying respirators [PAPRs]) are used, they must be cleaned and disinfected according to manufacturer’s reprocessing instructions prior to re-use.

■ When the supply chain is restored, facilities with a respiratory protection program should return to use of respirators for patients with known or suspected COVID-19. Those that do not currently have a respiratory protection program, but care for patients with pathogens for which a respirator is recommended, should implement a respiratory protection program.

• Eye Protection

○ Put on eye protection (i.e., goggles or a disposable face shield that covers the front and sides of the face) upon entry to the patient room or care area. Personal eyeglasses and contact lenses are NOT considered adequate eye protection.

○ Remove eye protection before leaving the patient room or care area.

○ Reusable eye protection (e.g., goggles) must be cleaned and disinfected according to manufacturer’s reprocessing instructions prior to re-use. Disposable eye protection should be discarded after use.

• Gloves

○ Put on clean, non-sterile gloves upon entry into the patient room or care area.

■ Change gloves if they become torn or heavily contaminated.

○ Remove and discard gloves when leaving the patient room or care area, and immediately perform hand hygiene.

• Gowns

○ Put on a clean isolation gown upon entry into the patient room or area. Change the gown if it becomes soiled. Remove and discard the gown in a dedicated container for waste or linen before leaving the patient room or care area. Disposable gowns should be discarded after use. Cloth gowns should be laundered after each use.

○ If there are shortages of gowns, they should be prioritized for:

■ aerosol-generating procedures

■ care activities where splashes and sprays are anticipated

■ high-contact patient care activities that provide opportunities for transfer of pathogens to the hands and clothing of HCP. Examples include:

■ dressing

■ bathing/showering

■ transferring

■ providing hygiene

■ changing linens

■ changing briefs or assisting with toileting

■ device care or use

■ wound care

3. Patient Placement

• For patients with COVID-19 or other respiratory infections, evaluate need for hospitalization. If hospitalization is not medically necessary, home care is preferable if the individual’s situation allows.

• If admitted, place a patient with known or suspected COVID-19 in a single-person room with the door closed. The patient should have a dedicated bathroom.

○ Airborne Infection Isolation Rooms (AIIRs) (See definition of AIIR in appendix) should be reserved for patients who will be undergoing aerosol-generating procedures (See Aerosol-Generating Procedures Section)

• As a measure to limit HCP exposure and conserve PPE, facilities could consider designating entire units within the facility, with dedicated HCP, to care for known or suspected COVID-19 patients. Dedicated means that HCP are assigned to care only for these patients during their shift.

○ Determine how staffing needs will be met as the number of patients with known or suspected COVID-19 increases and HCP become ill and are excluded from work.

○ It might not be possible to distinguish patients who have COVID-19 from patients with other respiratory viruses. As such, patients with different respiratory pathogens will likely be housed on the same unit. However, only patients with the same respiratory pathogen may be housed in the same room. For example, a patient with COVID-19 should not be housed in the same room as a patient with an undiagnosed respiratory infection.

○ During times of limited access to respirators or facemasks, facilities could consider having HCP remove only gloves and gowns (if used) and perform hand hygiene between patients with the same diagnosis (e.g., confirmed COVID-19) while continuing to wear the same eye protection and respirator or facemask (i.e., extended use). Risk of transmission from eye protection and facemasks during extended use is expected to be very low.

■ HCP must take care not to touch their eye protection and respirator or facemask.

■ Eye protection and the respirator or facemask should be removed, and hand hygiene performed if they become damaged or soiled and when leaving the unit.

○ HCP should strictly follow basic infection control practices between patients (e.g., hand hygiene, cleaning and disinfecting shared equipment).

• Limit transport and movement of the patient outside of the room to medically essential purposes.

○ Consider providing portable x-ray equipment in patient cohort areas to reduce the need for patient transport.

• To the extent possible, patients with known or suspected COVID-19 should be housed in the same room for the duration of their stay in the facility (e.g., minimize room transfers).

• Patients should wear a facemask to contain secretions during transport. If patients cannot tolerate a facemask or one is not available, they should use tissues to cover their mouth and nose.

• Personnel entering the room should use PPE as described above.

• To the extent possible, patients with known or suspected COVID-19 should be housed in the same room for the duration of their stay in the facility (e.g., minimize room transfers).

• To the extent possible, patients with known or suspected COVID-19 should be housed in the same room for the duration of their stay in the facility (e.g., minimize room transfers).

• Whenever possible, perform procedures/tests in the patient’s room.

• Once the patient has been discharged or transferred, HCP, including environmental services personnel, should refrain from entering the vacated room until sufficient time has elapsed for enough air changes to remove potentially infectious particles (more information on clearance rates under differing ventilation conditions is available). After this time has elapsed, the room should undergo appropriate cleaning and surface disinfection before it is returned to routine use (See Section 10).

4. Take Precautions When Performing Aerosol-Generating Procedures (AGPs)

• Some procedures performed on patient with known or suspected COVID-19 could generate infectious aerosols. In particular, procedures that are likely to induce coughing (e.g., sputum induction, open suctioning of airways) should be performed cautiously and avoided if possible.

• If performed, the following should occur:

○ HCP in the room should wear an N95 or higher-level respirator, eye protection, gloves, and a gown.

○ The number of HCP present during the procedure should be limited to only those essential for patient care and procedure support. Visitors should not be present for the procedure.

○ AGPs should ideally take place in an AIIR.

○ Clean and disinfect procedure room surfaces promptly as described in the section on environmental infection control below.

5. Collection of Diagnostic Respiratory Specimens

• When collecting diagnostic respiratory specimens (e.g., nasopharyngeal swab) from a possible COVID-19 patient, the following should occur:

○ HCP in the room should wear an N-95 or higher-level respirator (or facemask if a respirator is not available), eye protection, gloves, and a gown.

○ The number of HCP present during the procedure should be limited to only those essential for patient care and procedure support. Visitors should not be present for specimen collection.

○ Specimen collection should be performed in a normal examination room with the door closed.