Chapter 21

Ten Ways to Improve Your Attention with Mindfulness

IN THIS CHAPTER

Reducing mind wandering

Practicing formal mindfulness exercises to train your brain

Checking out simple everyday mindfulness to improve your attention

This chapter brings together a number of useful mindfulness techniques that will help you improve your focus and attention. The best way to train your attention is via formal mindfulness exercises as we outline in Chapters 8 through 13. These exercises can feel repetitive (your mind wanders, you notice and bring it back, and then your mind wanders again …). This is intentional because the repetition helps you get better at managing your wandering mind and hardwires new pathways in your brain that strengthen attention.

Many leaders we’ve worked with find it difficult to practice formal mindfulness exercises while at work, which is why the WorkplaceMT mindfulness training we teach includes informal everyday mindfulness exercises that are easy to slip into your day.

In this chapter, you find both formal and informal everyday mindfulness exercises, which help you to hardwire the ability to manage your attention over time. The only difference is that formal mindfulness exercises are like taking your brain to the gym for an intensive workout, while everyday mindfulness takes less time and is less intensive.

Noticing When Your Mind Wanders

Harvard research suggests that, on average, the human mind wanders for around 50 per cent of the day. Each time your mind wanders, a period of time elapses before you recognise that it’s no longer where you had intended it to be. Only when you recognise that your mind has wandered can you bring it back to where you want it to be.

Formal mindfulness exercises, such as mindfulness of breath (Chapter 8) or body scan (Chapter 9), require you to focus your attention on one thing. Doing this helps you notice more quickly when your mind has wandered and bring your attention back. Over time this improves your ability to remain focused.

For example, if you’re focusing your attention on your breath and you find yourself thinking about the report you have to write, a family excursion, or that promotion you hope to gain, your mind has wandered. You then kindly and gently focus your full attention back on your breath. Why kindly and gently? Because blaming yourself or beating yourself up for your inability to remain focused doesn’t help – it only makes things worse.

Negative emotions like anger can trigger your threat response, releasing the stress hormone cortisol into your bloodstream, making it even harder to focus your attention. By making light of the fact that your mind has wandered, accepting that you’re only human and this is what human brains do, or even congratulating yourself on having noticed your mind has wandered, makes it much easier to regain and maintain your focus.

Noticing that your mind has wandered and accepting it are critically important to improving your focus and attention.

Noticing that your mind has wandered and accepting it are critically important to improving your focus and attention.

Focusing on Breath

This formal exercise isn’t about controlling your breath. There is no right or wrong way to breathe. Simply observe, without judgment, the natural rhythm and sensations of breathing, from moment to moment. Newcomers to mindfulness usually find it easier to use the guided MP3 provided (Track 1A or 1B). (If you want more information about this exercise, see Chapter 8.)

This formal exercise isn’t about controlling your breath. There is no right or wrong way to breathe. Simply observe, without judgment, the natural rhythm and sensations of breathing, from moment to moment. Newcomers to mindfulness usually find it easier to use the guided MP3 provided (Track 1A or 1B). (If you want more information about this exercise, see Chapter 8.)

- Settle yourself in a chair where you can sit in a comfortable upright position.

-

Plant both feet firmly on the floor, relax your shoulders with the chest open and your head facing forward with the chin dipped slightly to your chest.

Your upper body should feel confident and self-supporting, embodying a sense of wakefulness and alertness. Close your eyes.

-

Direct your attention to the contact points between your body and the chair and floor.

Spend a few minutes exploring how your feet, legs, bottom and any other areas in contact with the chair and floor feel in this moment in time. Briefly scan each area of your body in turn, starting at the feet and finishing at the crown of your head. If you detect any tension, experiment with breathing into the area on the in breath and imagine releasing the tension on the out breath.

-

Focus your attention on the breath.

Notice how the chest and abdomen feel as the breath enters and leaves the body. If this is difficult, focus first on wherever your feel the breath most vividly.

- Place your hand on your abdomen and focus your attention on the sensations of the abdomen rising and falling in its own natural rhythm.

- Allow your hand to gently return to your side and shift the focus of your attention to the short pause that occurs naturally between the in breath and out breath.

-

Refocus your attention to the tip of your nostrils.

Observe the sensation of the breath entering and leaving the body through the nostrils. Notice any subtle differences between the temperature of the air as it enters and leaves your nostrils.

-

Refocus your attention back to the body.

Tune in to your body and notice how it feels in this moment in time.

- At the end of the practice session, gently stretch your fingers and toes and open your eyes.

If your mind wanders away from focusing on your breath, it’s okay – you are human after all! Simply kindly and gently bring your attention back to where you want it to be.

If your mind wanders away from focusing on your breath, it’s okay – you are human after all! Simply kindly and gently bring your attention back to where you want it to be.

Focusing on Your Body

It’s recommended that you practice the body scan formal exercise somewhere you’re sure not to be disturbed for around 15 minutes. Newcomers to mindfulness usually find it easier to use the guided MP3 provided (Track 2A or 2B) rather than attempting to guide themselves.

If you’re practicing this at home, you may like to try this lying on a bed, but beware – doing so may send you to sleep. If it does, no problem – you probably needed the sleep, but try it in a chair the next day.

If you want more information about this exercise, check out Chapter 9.

If you want more information about this exercise, check out Chapter 9.

If at any point during the exercise you feel any discomfort, treat it as an opportunity to explore what’s going on. Approach the discomfort with kindness and curiosity. What does it feel like? What sensations arise? What thoughts enter your mind? What emotions are you experiencing? Then try letting go of the discomfort as you breathe out.

If at any point during the exercise you feel any discomfort, treat it as an opportunity to explore what’s going on. Approach the discomfort with kindness and curiosity. What does it feel like? What sensations arise? What thoughts enter your mind? What emotions are you experiencing? Then try letting go of the discomfort as you breathe out.

-

Sit on a comfortable chair, with your feet firmly on the floor.

Sit with your back upright, your knees slightly lower than your hips, and your arms supported and resting comfortably. Make sure your whole body feels balanced and supported. Close your eyes, and try to remain aware of your posture throughout the exercise, and realign yourself if you notice that you’re slouching.

-

Focus your attention on your breath.

Feel the sensations of your breath coming in and your breath going out. Do so for approximately ten breaths.

-

Focus your attention on your toes.

Start with your right foot, and identify whether you can feel any sensations in your toes, such as hot, cold or tingling. See whether you can feel your toes in contact with your socks or shoes. Spend a few moments exploring your toes, and then repeat the process with your left foot. Don’t try to create any sensations or make it be any different from how it is; just notice what is there in that moment. If you can’t feel any sensation at all, just notice the lack of sensation – that’s absolutely fine. Compare your right and left toes. Do they feel any different?

-

Focus your attention on the soles of your feet.

Start with your right sole, and identify what you feel. Repeat the process with your left sole, and then compare the sensations you experienced with your right and left soles.

-

Focus on your lower legs.

Spend time exploring the right lower leg then the left, and then compare the two.

-

Focus on your knees.

Examine the sensations in your right knee then your left knee, and then compare the two.

-

Focus on your thighs and bottom.

Explore how they feel when in contact with the chair.

-

Explore the sensations in your internal organs.

Focus on your liver, kidneys, stomach, lungs and heart. You may not notice any sensation at all, and that’s okay – just see what you can notice.

-

Focus on your spine.

Move up your spine slowly, focusing briefly on one vertebrae at a time, noticing any or no sensations.

-

Focus on your arms.

Identify the sensations in your right arm then your left arm, and then compare the two.

-

Focus on your neck and shoulders.

If you experience any tension or discomfort, try letting it go as you breathe out.

-

Focus on your head

Notice any feelings and sensations in your jaw and facial muscles. Notice how your nose feels, how your eyes feel, how your scalp feels.

- Expand your attention to gain a sense of how your whole body feels at this moment in time.

- Open your eyes and return to your day.

Focusing on Sounds

This formal exercise is a shortened variation of the sounds and thoughts exercise in Chapter 11.

- Settle yourself into your chair, sitting in a comfortable upright position that embodies the intention to practice mindfulness.

- Close your eyes, or hold them in soft focus gazing downwards.

-

Gently direct your attention inwards towards your breath.

Tune in to the sensations of the breath entering and leaving your body. Allow your breathing to fall into its own natural rhythm. You don’t need to change your breathing in any way – your body knows exactly how to breathe. Focus on the sensations of breathing for around two minutes.

-

Shift your attention to the sounds that surround you.

As you notice each sound, let go of the habit of naming and judging it. Treat everything you hear as equal – beyond being pleasant or unpleasant. See if you can notice more subtle sounds or sounds within sounds.

If your mind wanders, kindly guide it back to focusing your full attention on the sounds that surround you. Simply allow sounds to enter and exit your conscious awareness. Practice this for around five minutes.

If your mind wanders, kindly guide it back to focusing your full attention on the sounds that surround you. Simply allow sounds to enter and exit your conscious awareness. Practice this for around five minutes.

-

Gently move your attention back to your breath.

Remember: you don’t need to change your breathing in any way. Focus on the sensations of breathing for around two minutes.

- Shift your attention back to your body, spending the last two minutes observing (and if you wish, releasing tension), working from the tips of your toes to the crown of your head.

- When you’re ready to do so, open your eyes. Have a stretch if you wish to, and reconnect with your day.

Using Your Body as an Early Warning System

People commonly hold tension in areas of their body. Where they hold that tension varies from person to person. I (Juliet) tend to clench my jaw when under pressure, closely followed by hunching my shoulders. Some people clench their hands; others feel a knot on their stomach.

Which areas of your body do you feel tension when working under pressure? After you identify the one or two areas of your body where you commonly hold tension, you can use it as an early warning system.

By checking in with these areas on a regular basis, you can detect and release tension before it impacts your performance. You can also use the presence of tension as an indicator that your performance is dropping off and you need to do something to bring yourself back to peak performance.

Avoiding Falling into the Zone of Delusion

At some point each day, you reach a state of flow. You’re in a state of flow when you’re completely immersed in an activity. Time flies. Every action, movement, and thought follows inevitably from the previous one. You’re using your skills to the utmost.

If you experience excessive pressure, you may fall out of this state of flow and enter the zone of delusion. The zone of delusion is that state where you’re working hard but achieving little. Your ability to focus diminishes, and you repeat work because you’re making mistakes. Your mind may be telling you to work harder and push on to get things done, but despite your hard work, you actually achieve very little.

Although it may sound counterintuitive, the best thing to do when you enter the zone of delusion is to stop what you’re doing and do something that takes your mind away from the task. Take a short walk. Drink something hot or cold slowly and mindfully, enjoying every mouthful.

Although it may sound counterintuitive, the best thing to do when you enter the zone of delusion is to stop what you’re doing and do something that takes your mind away from the task. Take a short walk. Drink something hot or cold slowly and mindfully, enjoying every mouthful.

To avoid entering the zone of delusion, use your body as an early warning system, and take action at the first sign that you have fallen out of flow and into delusion. A few minutes of informal mindfulness at this point can bring you straight back to a state of flow.

To avoid entering the zone of delusion, use your body as an early warning system, and take action at the first sign that you have fallen out of flow and into delusion. A few minutes of informal mindfulness at this point can bring you straight back to a state of flow.

Minding the Gap

Your mind can easily wander into focusing on the coulds, shoulds and oughts. To maintain focus and attention, you need to ‘mind the gap’. Mind the gap between the stories that your mind creates about how things ‘should’ or ‘ought’ or ‘could’ be and how things really are in any given moment in time. Doing so will help you keep focused for longer, or get back on track. For more on minding the gap, see Chapter 10.

Enjoying Mindful Coffee and Chocolate

Pausing to fully appreciate the present-moment experience of eating or drinking can be a great way to regain your focus. Eating is something that many busy people do on autopilot. People bite, chew and swallow often without noticing the texture or flavour of what they’re eating.

Try paying mindful attention to that next cup of coffee or square of chocolate that you eat. Notice its colour, appearance, and aroma. Notice your body’s response – does your mouth salivate? Notice how it feels to chew or swallow.

You can treat anything you eat or drink in this way – for a few bites, sips or for the whole snack bar, meal or cup. Being fully immersed in doing so can help you to refocus your attention. It can also make the experience of eating a more pleasurable one. You can find out more about this in Chapter 8.

You can treat anything you eat or drink in this way – for a few bites, sips or for the whole snack bar, meal or cup. Being fully immersed in doing so can help you to refocus your attention. It can also make the experience of eating a more pleasurable one. You can find out more about this in Chapter 8.

Engaging in Mindful Walking

However desk-bound you are, there are always certain points in your day when you walk. For example, you may walk from the Underground, bus stop or car into work. You may walk from office to office or up and down stairs.

See Chapters 5 and 6 for examples of how mindful leaders Tim and Marion incorporate this mindful activity into their day.

Every step you take can be an opportunity for some mindful walking. Doing so is really easy. Simply tune in to the sensations you experience as you walk. Notice how your weight shifts from side to side as you walk. Notice which parts of the foot move with each step. Fully tune in to the experience of walking.

Every step you take can be an opportunity for some mindful walking. Doing so is really easy. Simply tune in to the sensations you experience as you walk. Notice how your weight shifts from side to side as you walk. Notice which parts of the foot move with each step. Fully tune in to the experience of walking.

If you have time, have a walk outside and connect with nature. Whether it’s a 5- or 15-minute walk, try to fully focus on the walk – the sensations of walking and the texture or the surface you’re walking on. Notice the architecture or nature surrounding you and the colours and smells you experience. Doing so can be enjoyable, release tension and improve focus thereafter.

Doing the Three-Step Body Check

This exercise is a really quick version of the body scan exercise (see Chapter 9). Many people find this exercise useful and easy to do while sitting at their desk – and appearing to be staring at their computer screen.

You can do this exercise with your eyes open in soft focus (just slightly opened and looking downwards) or closed. Sit in a comfortable, upright position with your feet firmly on the floor. Centre yourself by focusing on the sensation of taking three slow breaths.

-

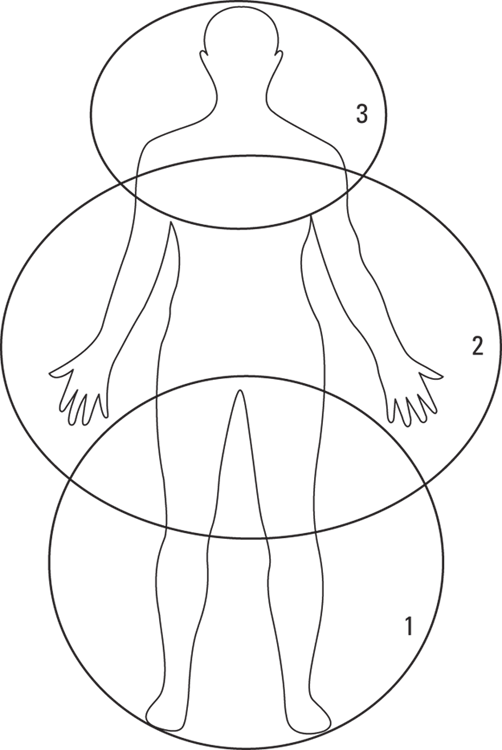

Focus on your feet, legs and lower body (area 1 in Figure 21-1).

Notice the sensations you experience, such as heat, cold or tingling, when you focus your full attention on your feet. Pause to observe, and then repeat with your legs, followed by your bottom.

- Repeat as above, focusing on your chest and internal organs, followed by your arms (area 2 in Figure 21-1).

- Repeat as above, focusing on your neck and shoulders. Follow this with your jaw, nose, facial skin and scalp (area 3 in Figure 21-1).

- Finish by centring yourself by focusing on the sensations of taking three slow breaths.

Noticing that your mind has wandered and accepting it are critically important to improving your focus and attention.

Noticing that your mind has wandered and accepting it are critically important to improving your focus and attention. This formal exercise isn’t about controlling your breath. There is no right or wrong way to breathe. Simply observe, without judgment, the natural rhythm and sensations of breathing, from moment to moment. Newcomers to mindfulness usually find it easier to use the guided MP3 provided (Track 1A or 1B). (If you want more information about this exercise, see

This formal exercise isn’t about controlling your breath. There is no right or wrong way to breathe. Simply observe, without judgment, the natural rhythm and sensations of breathing, from moment to moment. Newcomers to mindfulness usually find it easier to use the guided MP3 provided (Track 1A or 1B). (If you want more information about this exercise, see