Mengele’s Brazilian savior, Wolfgang Gerhard, was as fanatical a Nazi as they come. Each Christmas he adorned his tree with a swastika. “You always have to take good care of swastikas,” he used to say. He told friends he dreamed of “putting a steel cable to the leg of Simon Wiesenthal [the Vienna-based Nazi-hunter] and dragging him to death behind my car.” His Brazilian-born wife, Ruth, was just as unhinged. She once gave her landlady two bars of soap, in their original 1943 wrappers, made from the corpses of Auschwitz inmates.1

After his wartime service as a Hitler Youth leader in Graz, Austria, Gerhard remained a Fascist for the rest of his life. He even christened his son “Adolf.” “Wolfgang made no bones about being 150 percent Nazi,” a former workmate recalled. In Brazil he was vague about what he did, having variously owned a small textile printing plant and worked in a publicity agency and as a welder. But what made Gerhard useful to Mengele was that he dabbled in real estate.

As a small-time property owner, Gerhard knew people with farms and estates that were far off the beaten track, ideal for a man like Mengele, now desperately seeking a Brazilian sanctuary. Gerhard had been introduced to Mengele in Paraguay, through Hans Rudel, the Luftwaffe ace. Rudel asked Gerhard to help his friend find a new refuge in Brazil and Gerhard jumped at the opportunity. Too young to have played an important role during the war, Gerhard relished the chance to protect one of the Third Reich’s most notorious war criminals. Initially, Gerhard let Mengele stay on his farm at Itapecerica about forty-three miles from the center of São Paulo. After several months, Gerhard introduced Mengele to the family he had chosen to act as his next protectors. Their name was Stammer, a Hungarian couple who had moved to Brazil in 1948 to escape the Iron Curtain being drawn across Europe. Mengele was to spend the next thirteen years with them.

Gerhard had met Geza Stammer and his wife, Gitta, in 1959 at a special evening for Austrian-Hungarian expatriates. “You could say that we were firm anti-communists,” said Gitta, “but we weren’t Nazis.” Even so, the Stammers shared with Gerhard some unpalatable revisionist views. “I think some things about the Holocaust may have been invented,” Gitta said. “It’s hard for people to believe all these things are really true.”2

According to the Stammers, Gerhard introduced Mengele to them—as “Peter Hochbichler,” a Swiss—as a suitable manager for a thirty-seven-acre farm in which they were planning to invest. It produced coffee, rice, fruit, and dairy cattle in a remote German community near Nova Europa, two hundred miles northwest of São Paulo. “Gerhard said he had a friend, an acquaintance, a lonely man who liked the country life far away from towns,” said Gitta Stammer. “He said he could be of much help to us.”* Gerhard told the Stammers that not only was “Hochbichler” an experienced cattle breeder but he had also recently inherited some money which he wanted to invest in Brazilian real estate. To the Stammers it was an attractive proposition, particularly since an extra pair of hands would fill the gap left by Geza Stammer when his job as a surveyor took him away for several weeks at a time.

One weekend, Gerhard brought Mengele to meet the Stammers, as Gitta Stammer explained:

The first impression that I got from him was that he was a simple man, clean and tidy, but nothing exceptional. His hands showed that he was used to working hard because they were full of calluses.3

For Mengele, the arrangements to move took a nerve-wrackingly long time. But as would so often be the case in years to come, it was Gerhard who smoothed his path. From that period on, Wolfgang Gerhard was there, counseling, protecting, encouraging. Even though he could sometimes barely feed his own children, Gerhard somehow always found the time and money to help Mengele when it was necessary.

As Mengele waited anxiously for Gerhard’s plan to materialize, he occupied himself with a temporary job in São Paulo. His diary suggests he was helping Gerhard with his textile business:

I have had a very busy week behind me. The work isn’t very enjoyable and comes right after sticking down paper bags. But it’s important for my host because it earns him a fortune.4

The grinding routine of the job and anxiety about his uncertain future had begun to wear Mengele down:

My life here is difficult, not only because of all the work (I have had to work a lot harder at times) but because of the entire situation: cramped conditions, monotony, primitiveness, noise and formlessness and which in the end, despite all this negativity, does not guarantee me any safety. I have only one aim and that is to change this, but unfortunately we haven’t come up with a good idea. “One” also isn’t in any great hurry because of all the other constantly unsolved problems. So I will persevere and continue to believe in my lucky star.5

Much to his irritation, Mengele also learned that further allegations—that he had dissected prisoners at the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp—had appeared in the press:

As you can see, my present mood is pretty bad, especially since I have had to deal these last weeks with this nonsense about attempting to strip bodies in B. . . . In this mood one finds no joy in a radiant sunny sky. One is reduced to being a miserable creature without love for life or substance.6

Eventually agreement with the Stammers was reached and “Peter” moved in with them to manage the farm at Nova Europa. But he declined any payment. According to Gitta Stammer, Mengele arrived at the farm looking thin and pale:

. . . he seemed to be ill. . . . Gerhard said he suffered from a certain disease, and his stay with us would help him recover. He showed us a document, a simple paper with no photograph, that had allowed him to cross the border from Austria to Italy. This was the only identification document I saw with this name. But we were not suspicious about him. He seemed simple enough as he just wanted his food and laundry.7

In their attempt to convince skeptics that they were just innocent dupes, the Stammers insist that at first there was nothing suspicious about “Peter Hochbichler” or his refusal to take a salary. Nor did his parcels of letters and newspapers from Germany strike them as strange. But the farmhands who suddenly found themselves in Mengele’s charge realized something was amiss. They noted that “Peter” read philosophy and history and loved classical music, especially Mozart. They also found that their new boss had a sharp temper which exploded as he struggled to make his orders understood in Portuguese, an alien language. “I didn’t like him, but I couldn’t do anything about it,” said Francisco de Souza, who was working for the Stammers when Mengele arrived. “He loved giving orders and kept saying that we should work more and harder. The worst of it was that he didn’t seem to understand much about farming or heavy work.”8

Try as he would, Mengele failed to earn the respect of his workers. They were amused when one of his experiments with farm gadgetry flopped badly:

He was determined to build a machine to deal with the problem of hookworm and white ants that were spread all over the farm. He made me mount a hook on a cart. On the end of the hook he suspended a 175-pound weight, and with this crazy machine he accompanied me around the farm to destroy these enormous anthills, some of them three feet high. He just stared while I had to pull the weight up and release the rope. The weight smashed the mound, but within a few hours the ants were making a new home for themselves. We thought it was a crazy idea; it took hours and hours to prepare.9

Mengele did have one skill, however, that impressed the farmhands. He operated on a calf suffering from a hernia. “He reached for some instruments,” said de Souza, who held the animal, “and cut its belly open quite expertly. He corrected the hernia and sewed up the cut. He said he could guarantee that the calf would get better, and it did. I noticed that he did everything with a high degree of dexterity.”10

Although the farmhands did not care for “Peter,” Gitta Stammer liked him. According to the farmhands in Nova Europa, from the moment “Peter” arrived, he and Gitta Stammer got on well together. They spoke in German, and she appreciated having a man on the premises since her husband was often away. But today Gitta Stammer tries to put a distance between herself and Mengele. She claims she mostly felt uneasy. “I don’t even want to remember those thirteen years that he lived with us,” she said. “He tried to order us—he was very authoritarian. Once he almost hit me.”11

Unbeknownst to the Stammers and the farmhands, Mengele was difficult initially because he did not like the farm or his work. In this first phase of his Brazilian exile, Mengele found it hard to come to terms with his new lowly status. And despite his greater security at remote Nova Europa, his fear of capture by the Israelis plagued him. It revived his insecurity over his prominent forehead, which he nearly had had altered by plastic surgery in Argentina. As he went about his work on the farm, Mengele always wore a hat, even in the heat of summer. “Whenever I got near him, he pulled the hat down over his face and dug his hands into his pockets,” said Enercio de Oliveira, who harvested corn with Mengele. Zaire Chile, a maid, said that Mengele usually wore a shirt buttoned at the collar and a raincoat. “I never saw anyone on a farm dress like that,” she said.12

Mengele’s fear of an Israeli strike was well founded. Since the beginning of 1961, following the failed kidnap attempt in Buenos Aires, a formidable task force of Mossad agents had been assembled to track him down. Indeed, many members of the new Mengele task force had also been on Operation Eichmann.

The team was headed by Zvi Aharoni, the agent who had provided the crucial confirmation that Eichmann was living in Buenos Aires under the name Klement, pinpointed his house, and interrogated him after his abduction. The headquarters of Aharoni’s operation was Paris. One team concentrated on Mengele’s friends and family in Europe, the other turned to South America.

The Mossad’s starting point was Paraguay, and their strategy was to try to establish links with those who knew Mengele well, so that there was ready access to reliable information on his location at any given time. Only when that was accomplished could the Israelis give serious thought to actually kidnapping Mengele. “It was not our intention at any stage to kill him,” said Isser Harel, head of the Mossad at the time. “That would have defeated the whole purpose of the exercise. We wanted him back in Israel for a public trial. That was more important than anything.”

According to Harel and another senior Mossad agent, Rafi Eitan,* who was code-named “Gabi” in Operation Eichmann, Mengele felt so at risk that he occasionally traveled to another farm near São Paulo and went across the border to Paraguay. Gitta Stammer said that when Mengele first came to live with them, he “never ventured out.” But Eitan insisted that Mengele hid at Alban Krug’s farmhouse in Hohenau on several occasions in 1961 and 1962.

For the Paraguayan end of their operation, the Israelis resorted to a ruse to penetrate the Krug family and their circle of neo-Nazi friends. An Englishman working for the Mossad was asked to strike up a love affair with one of Krug’s daughters. He was not very successful. But Eitan, who spoke no German or Spanish, claimed he once got close enough to Krug to catch sight of Mengele. “I saw him with my own eyes,” he said. A Mossad colleague was more skeptical of Eitan’s claim. “I’m surprised Rafi should say this,” the Mossad man said. “How the hell he got that close I don’t know. He couldn’t even say gracias in Spanish.”13

Zvi Aharoni, coordinating the Mengele hunt from Paris, said he was certain no Mossad agent ever saw Mengele in Paraguay. “I made several trips to Paraguay in 1961,” he said. “I can tell you that we got nothing, not a thing from Paraguay.” But it was not for want of trying. Aharoni’s team adopted a variety of cover identities in the country. One agent was a financial consultant; another was a historian writing a book on the SS. He got as far as seeing the former Gauleiter of the Nazi party in Paraguay. “It was clear the man knew nothing about Mengele,” said Aharoni.

Even to this day, Mossad agents disagree about exactly how close they got to Mengele in Paraguay, and about his degree of protection. Harel said his men became convinced in 1961 that Mengele was in Paraguay and was being sheltered by Alban Krug. “By the end of the year, we knew that he was moving between Paraguay and Brazil,” said Harel. “He was completely panicked by the Eichmann abduction.” Harel also claimed that Mengele was protected by armed guards and dogs on Krug’s farm, though his agents in the field say they saw neither guns nor dogs. Harel did admit, however, that none of his agents actually saw or photographed Mengele in Paraguay.

The conflicting statements about Mengele’s movements in the early 1960s reflects the soul-searching that surfaced within Israel’s intelligence community after Mengele’s death was disclosed. The discovery in June 1985 that Mengele had lived in Brazil for most of his fugitive life raised questions as to why the Israelis had never found him, much less apprehended him.

The difficulties confronting the Mossad were certainly daunting. By the end of 1961, Operation Mengele was a large and expensive venture, more costly than even the Eichmann capture. But according to Zvi Aharoni, despite the grand effort, his men had made little headway by the end of 1961. Attempts to follow Hans Rudel to South America to see if he was meeting Mengele had failed. Rudel wrote to his friend Wolfgang Gerhard in February 1961 that he had become aware that he was being watched.14 It proved impossible to keep tabs on him once he arrived in Paraguay. Agents in Europe had fared no better in their efforts to intercept mail going to Mengele’s estranged wife, Martha, who was living in Merano, in northern Italy. Another major problem for the Mossad was how to spirit Mengele out of a landlocked country like Paraguay or from the interior of Brazil. Harel explained:

There were several major difficulties with Mengele which made the task of capturing him much harder than Eichmann. First, we had to be exactly sure where he was, and that information was proving hard to get. We thought we knew but since no one had actually seen him, we couldn’t plan a commando operation. We had to be 100 percent sure before that stage could be seriously considered. Even if all that had been achieved, we still had to get him out of the country. There was no question of shooting him. The priority was always getting him back to Israel for a trial.15

Meanwhile, the more sedentary West German hunt was now progressing on three fronts. In February 1961, Bonn extended its extradition request from Argentina to Brazil. Word had reached Fritz Bauer, prosecutor for the state of Hesse, that Mengele might have fled to Brazil. But Bauer’s information was more of a hunch than solidly based, perhaps nothing more tangible than what was available to the CIA station in Asunción at the time. The CIA reported that Mengele was “rumored to have gone to the Mato Grosso, Brazil.”16 In Asunción, Peter Bensch, the chargé d’affaires at the West German embassy, also continued to make inquiries. He had managed to procure a copy of Mengele’s citizenship document. But the embassy’s attempts to take evidence from Paraguayans who might have seen Mengele soon ran into trouble. “They told us that we had no right to mount what they said was a semi-judicial inquiry,” said Dr. Bensch. Bensch’s inquiries to the supreme court on the prospects of extradition were not very encouraging either:

My own view was that Mengele was moving between Paraguay and Brazil at this time, but we had no precise information on him. The supreme court did tell me that if he was found in Paraguay it would not be possible to extradite a Paraguayan citizen. I personally did not talk to President Stroessner about the matter, but we did tell Bonn that as long as Mengele was a Paraguayan citizen, extradition from Paraguay would probably be impossible.17

In Argentina, meanwhile, a legend was being born. Mengele, it seemed, had almost superhuman powers of escape. He was wealthy; he had an army of agents; he was one step ahead of the Israeli secret service; and he was armed and extremely dangerous. The evidence lay at the foot of the Andes mountains near the Argentine resort town of Bariloche, where an Israeli woman had mysteriously fallen to her death. Argentine newspapers asked if she might not have been a Mossad agent sent to seduce Mengele and kill him, but instead Mengele had killed her.

The entire fiction was based on nothing more than a climbing accident that indeed had involved a woman tourist who had once lived in Palestine. She was Norit Eldad, an attractive, blonde, middle-aged woman, born in Frankfurt. She was reported missing in March I960, only two months before the Eichmann kidnapping, after she went for a walk on the footpath of Cerro Catedral, the tallest mountain in the region. The leader of the search team, Professor Esquerra, president of the local ski club, was quoted as saying that when the body was finally found, he “immediately thought it was a strange place for a hiker to have a fatal accident. If it was a natural death, fate had done an excellent job in hiding the body from view.” The body was deep in a crevasse, the result of an accidental fall from a precipice. Perhaps the “Angel of Death” had showed his hand? A simple spelling mistake in the hotel register had listed Norit Eldad as “Eldoc.” Investigators mistook the error to be the pseudonym of an Israeli agent. The theory certainly appealed to local police inspector Victor Gatica, who said:

The apparent motive now is that she was searching for Josef Mengele, the Nazi doctor. Now it is considered that Dr. Mengele may have been staying in Bariloche.18

No one proved that Mengele had stayed there. But neither could they prove that he had not. Thus Mengele was reported as having accompanied Norit Eldad on her fatal walk. They had become lovers, according to the story, she with the purpose of setting him up for an ambush by a team of Israeli hit men waiting in a nearby hotel. A false-bottomed suitcase had been found by Mengele’s bodyguards while the couple were out: they had rushed out to tell Mengele; she was pushed over a precipice; Mengele had fled town. Now everything fit. The South American newspapers banner-headlined this news of Mengele’s mountaintop encounter with an Israeli assassin.

On March 21, 1961, the Israeli embassy in Buenos Aires vainly tried to convince the newspapers that Norit Eldad was not a Mossad agent, saying she was known as a “timid and nervous person. Certainly it is not possible that she was an agent involved in a mission as difficult as finding Mengele.” But after the cloak-and-dagger kidnapping of Eichmann, no one believed the Israelis. And when Simon Wiesenthal published his book, The Murderers Among Us, in 1967, claiming that Miss Eldad had been in a concentration camp, the story was accepted as fact. Wiesenthal even added one more touch of drama: Miss Eldad had been sterilized by Mengele, who recognized her while she was staying at the hotel. He had spotted her camp tattoo at a hotel dinner dance and had her killed because he feared she would betray him. Here was the genesis of Marathon Man and The Boys from Brazil.

The real hunt was a lot more hit-and-miss than that. Early in March 1961, the Argentine police followed up á tip from the West German embassy, a letter from a Señora Silvia Caballero de Costa. It claimed that Mengele was living under a false name and was engaged to a wealthy young woman in Santiago del Estero, the northern provincial capital of Argentina. Interviewed by the police, Señora de Costa proved to be illiterate; she could not possibly have been the author of the mysterious letter. The author was soon revealed to be a wealthy merchant whose only daughter was engaged to a man he was convinced was Mengele because he claimed to be a German doctor. The fiancé turned out to be a New York con man, Willy Delaney, twenty-five years older than Mengele, without the slightest resemblance to him, and with prior convictions for assault, bribery, and practicing medicine illegally.19

The Delaney case was followed by numerous press reports that the Mossad was back on Mengele’s trail. The most spectacular, in the London Sunday Dispatch, quoted “reliable sources” who claimed that the Israelis had been given orders to “liquidate Mengele before the start of the Adolf Eichmann trial,” scheduled to start on April 11. One of the five Mossad agents, code-named “David,” had been relentlessly tracking Mengele for two years according to this story.

That same day another report came thundering over the wire services from Hamburg, where a German businessman, Peter Sosna, said he was sure he had met Mengele on a recent trip to Brazil. Sosna said that while he was in the Mato Grosso, in the town of Corumbá, a group of unidentified Germans introduced him to a doctor. Sosna reported that the doctor had Indian bodyguards and the meeting was held in great secrecy. On his return to Hamburg, Sosna went straight to the German prosecutor’s office and after being shown photographs of Mengele, positively identified him as the man he had seen. Much credibility was given to the sighting. Sosna worked for a marine chandler supply company and seemed a reliable witness. The idea of Mengele living in a vast, virtually unexplored rain forest the size of Texas added a touch of drama to the reputation of the man fast becoming the world’s most elusive fugitive.

In response to Sosna’s report, the Brazilian police launched one of its biggest manhunts. Corumbá swarmed with policemen, who established blockades at all points crossing the Rio Paraguay. On March 18, the police received a tip that Mengele was staying at a hotel in Corumbá and had registered in the name of “Juan Lechin”—yet another of the multitudinous aliases he was now said to be using. Brandishing guns, more than thirty officers stormed the hotel, where they found no one resembling Mengele but detained the hapless owner. “He seemed suspicious,” said the police inspector who led the raid.

On March 23 farce turned to tragedy, however, with the story that Mengele had at last been captured. This time there was no doubt, said the reports. He had been hiding in the province of Buenos Aires all along. It was a fact.

The man the police arrested had lived in the town of Coronel Suárez for seven years, and three newspaper journalists claimed credit for his arrest. They were Alfred Senadom of La Mañana and Juan Vessey Camben and Geoffrey Thursby of the London Daily Express. The suspect’s name was Lothar Hermann. By one of the strangest twists of fate, this was the same man who three years before had tipped off the Israelis that Eichmann was living in Buenos Aires. Hermann had suffered a complete nervous breakdown because he believed that the Israelis had ignored his contribution to that case. He had some cause for his grievance. Isser Harel wrote in his account of Operation Eichmann that he allowed the Mossad’s contact with Hermann to lapse because of inconsistencies in Hermann’s reports to Tel Aviv. In the end, of course, Hermann had been proved absolutely right.

At the La Plata police station, Hermann was almost incoherent. When asked if he was Mengele, he said he was. The poor man was in such a distraught state that he had no idea what he was saying. But it is difficult to understand how the police and the reporters seriously imagined they had got the right man since he was blind and bore no physical resemblance to Mengele.

Fortunately for Hermann, the police did take the trouble to check his fingerprints against a set of Mengele’s, which they had taken when issuing Mengele an identity card in 1956. On March 25, a chastened provincial police chief announced that they had “determined that Josef Mengele is not the same person that we have detained.” Hermann was released from custody and appeared quite mad when he gave a rambling interview to a group of reporters, threatening to sue the Daily Express, which he said had engaged in “yellow journalism.”

The Hermann story did illustrate, however, the lack of urgency and the failure of coordination with which the West Germans were then conducting the hunt for Mengele. One year after the Argentine arrest warrant was issued, the West Germans still did not have a copy of Mengele’s fingerprints for distribution to other German embassies in South America. On July 24, 1961, the West German embassy wrote to the Argentine foreign office:

According to statements in the press, the police have Mengele’s fingerprints in their possession, since it was possible to prove that the fingerprints of Lothar Hermann were not identical to those of Josef Mengele. As there is a possibility that Mengele may be in another country, a record of his prints is of singular importance in helping to facilitate the competent German authorities in the continuing investigation.20

For four months the Argentine police simply ignored the request. On November 20, the West Germans sent a reminder to the foreign office, asking them to “please give attention to the request, which is urgent due to the character of the case.” Finally, in December, the prints were sent.21

Little of the chaos and indifference surrounding the hunt filtered through to the public. They were treated instead to an almost weekly diet of new sightings and follow-up police operations. It was precisely because Mengele was portrayed as being able to elude such “dragnets” that his reputation flourished as a wily fugitive with superhuman powers of evasion.

On the farm at Nova Europa, meanwhile, Mengele remained unaware of many of the more imaginative press reports. According to Gitta Stammer, they rarely received newspapers. The irony was that although they did not know he was on their soil, the most active police hunts were conducted by the Brazilians.

On January 23, 1962, the Brazilian papers carried the headline that Mengele had been captured in the small border town of Pozos de Caldos. The prisoner was using the name “Solomon Schuller.” He was German and he worked for Bayer, the German multinational conglomerate. He was said to be “definitely pro-Nazi, quiet and mysterious.” The area Interpol director, Amoroso Neto, ordered Schuller’s detention and was so confident he was Mengele that he released the story before fingerprint verification had been completed. Two days later the police withdrew the allegation. Fingerprints had arrived from the Germans and showed that Schuller was in fact Hans Epfenger, a former member of the Waffen SS who was not wanted for war crimes but used an alias nevertheless.

Twenty-five-year-old Josef Mengele, at the time of his state medical examinations in Munich, 1936.

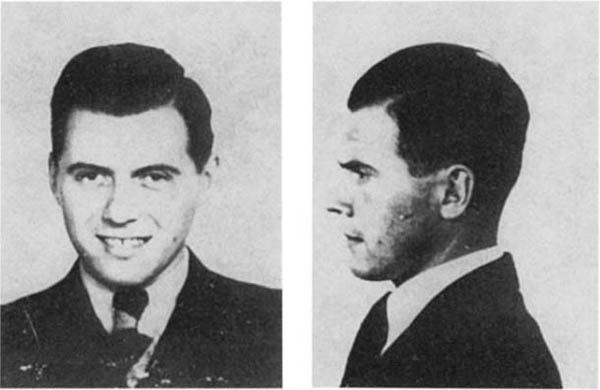

Mengele’s official SS photographs, stapled onto the front of his Nazi party file.

Shortly after receiving his medical degree in 1938, Mengele relaxes with his parents-in-law (seated) and a school friend, Dr. Kurt Lambertz.

The lavish wedding party in July 1938. Walburga and Karl Mengele are on their son’s left.

Adolf Hitler during a 1932 visit to Günzburg and the Mengele factory. Karl Mengele is on Hitler’s left.

Mengele conducting a “racial purity” interview with an elderly Polish couple. This picture, taken in Posen in September 1940, is the only known photograph of Mengele performing one of his SS medical duties.

Mengele, now a member of the Waffen SS, just prior to his 1942 departure for the eastern front.

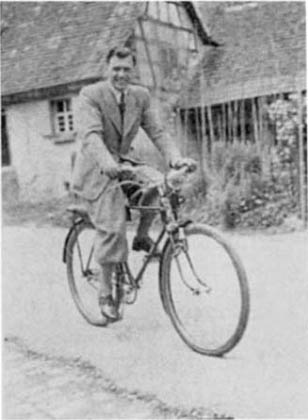

On leave during 1942, a relaxed Mengele bicycling outside Günzburg.

A rare picture of Mengele (left) at Auschwitz. At the time this photo was taken, he had been at the concentration camp for four months.

Mengele on leave during October 1943, only months after his Auschwitz posting. His Iron Cross is prominently displayed on the breast pocket of his uniform.

This is one of the few SS photographs of the selection ramp at Auschwitz. The inmates have been separated into groups of men and women, and the SS doctors are waiting to select which will live and which will die. The officer with the soft cap at the far right has been identified by camp survivors as Mengele. He has a cigarette in his hand, not unusual for the chain-smoker.

A rare photograph from the period when Mengele was in hiding in Germany. This photo of her husband and their son, Rolf, was taken by Irene Mengele during one of their secret rendezvous near Rosenheim in 1947.

The first known photograph of Mengele after his successful flight to South America, taken in December 1949, three months after his arrival in Buenos Aires.

A 1950 Christmas photograph of Mengele and a pet cat at his first permanent address in Buenos Aires, 2460 Calle Arenales, in the posh Florida suburb of the Argentine capital.

The only known photograph of Mengele’s two wives socializing, taken in Günzburg in 1950. Martha, who would marry Josef eight years later, is on the left; Irene, on the right. The two women are not friendly today.

Hans Sedlmeier, Mengele’s longtime protector and friend, in Günzburg with one of his children in the early 1950s.

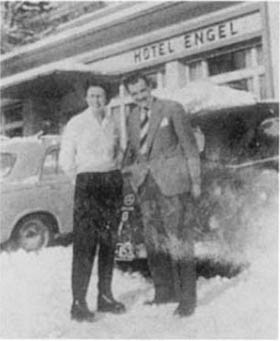

Josef and Martha meeting in the Swiss Alps in 1956, during Mengele’s first trip to Europe since his 1949 flight to South America. This photograph was taken by Hans Sedlmeier.

Mengele in Switzerland, posing as “Uncle Fritz,” holding his twelve-year-old son, Rolf.

Karl Heinz, Mengele’s stepson, and Martha, Mengele’s second wife, in a rare photograph taken in Argentina in 1958. Mengele’s dog was renamed Heinrich in order to maintain an Aryan tradition.

Colonel Hans Ulrich Rudel, Hitler’s ace of aces and Mengele’s postwar friend and protector (far left), relaxing after water-skiing with Captain Alejandro von Eckstein (far right), one of Mengele’s co-sponsors for citizenship in Paraguay. The boat driver (center) is a politician in Paraguay today. This 1963 photograph, taken at the Paraguayan resort of San Bernardino, was given to the authors by von Eckstein, from his personal scrapbook.

Dr. Eckart Briest, the West German ambassador to Paraguay during the early 1960s. This photograph was taken in Asunción during the time when Briest, unaware that Mengele had already fled to Brazil, continued to pressure the Stroessner government to surrender him.

The most widely circulated postwar photograph of a man believed to be Mengele. It helped to mislead Mengele’s pursuers for nearly twenty years.

Gitta Stammer, in a photograph taken shortly after Mengele began working on the Stammer farm.

Mengele showing Sabine and Andreas Bossert his workshop in Caieiras, Brazil.

Mengele between his two Brazilian protectors, Wolfgang Gerhard, on Mengele’s right, and Wolfram Bossert, on his left.

Hans Sedlmeier, Mengele’s courier and German mail drop, in West Germany, near the end of the Mengele hunt.

Alois Mengele, Josef’s youngest brother and chief of the Mengele farm machinery firm in Günzburg.

Karl Heinz, Mengele’s stepson, as a Mengele company executive and co-owner during the 1970s.

Rolf and Josef Mengele in Sāo Paulo during Rolf’s 1977 visit to Brazil. It was the first time the two had met as adults.

Josef and Rolf Mengele, together with Liselotte Bossert and her children, Sabine and Andreas, during the 1977 meeting of father and son.

Elsa Gulpian de Oliveira, Mengele’s housemaid, wrapped in a wool shawl he gave her. Mengele fell in love with her, and became depressed after she rebuffed his offer to move in with him.

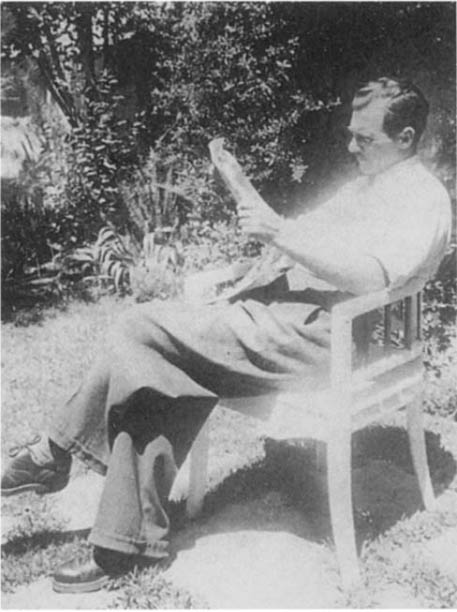

Mengele at Bertioga, the beach where he would drown in 1979. This picture was taken by Rolf Mengele during his 1977 visit with his father.

Wolfgang Gerhard’s Brazilian identity card. Mengele covered Gerhard’s photo with one of his own and then sealed the card in a plastic sleeve.

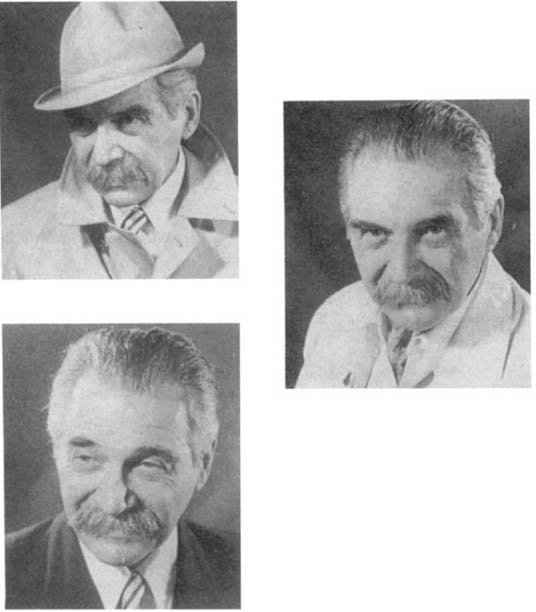

Wolfram Bossert, an amateur photographer, took these three pictures of Mengele in order to find an appropriate one for the identity card.

The gravedigger reopening Mengele’s grave on June 6, 1985. Sāo Paulo police chief Romeu Tuma is in a dark suit on the right. On Tuma’s left are Wolfram and Liselotte Bossert, brought to the scene in order to identify the correct grave.

The Sāo Paulo assistant coroner, José Antonio de Mello, holding Mengele’s skull for the assembled reporters.

Mengele’s skull, complete with reconstructed dental work, as assembled for the forensics examination in Brazil during the summer of 1985.

One of the more than 5,000 pages of Josef Mengele’s personal writings made available to the authors. Handwritten, loose-leaf and in bound notebooks, they constitute the largest literary cache left by a Nazi war criminal.

The following month a hotel manager, Elias Cardoso, told the police that a suspicious foreign visitor had checked in to his hotel in the frontier town of Auto Posto. He was German. Once when he got drunk, Cardoso heard a friend call him “doctor.” Later the mystery guest, in a drunken stupor, told Cardoso that he was a former member of the Gestapo and could not return home because the Germans “would slit my throat.” Cardoso told the police he thought his guest looked like Mengele. The local police called in the Brazilian federal police.

At dawn on February 28, 1962, twenty-five armed militiamen stormed into the room where the Mengele suspect was staying. The room was empty. The guest had checked out during the night without paying his bill. It was the sixth Brazilian alert in less than a year. Surely, said the newspapers, this was Mengele’s closest call?*

Midway through 1962, while several South American governments pursued a ghostlike fugitive, the real Mengele moved with the Stammers to a 111-acre coffee and cattle farm. Called “Santa Luzia,” the farm was in Serra Negra, 93 miles north of São Paulo. The dry heat at Nova Europa, said Gitta Stammer, had become oppressive. “We wanted cooler weather,” she recalls. Serra Negra is renowned for its rich soil, cool climate, and thermal springs amid gentle sloping mountains and woods. Once again Mengele provided capital, one half the purchase price of the farm.22

Although he had been against the move, once he arrived in Serra Negra Mengele began to relax for the first time in two years. He was involved in woodworking and construction on the farmhouse, work which he noted in his diary was “pleasing.” In his first diary entries after arriving at Serra Negra, Mengele wrote enthusiastically about the “beautiful landscape,” the “wondrous eucalyptus forests,” and the “high plateau that fills my soul with awe.” A month after his arrival, on August 19, 1962, Mengele summarized his feelings about his new hideout:

Now I have been here for four weeks already and I am splendidly settled. As much as I was opposed to the move, I now feel comfortable in this spot. No wonder—it has all that is necessary to provide home and solace to a peaceless man.23

Mengele may have felt more settled in Serra Negra, but his hosts did not. The Stammers became increasingly uneasy about their new farm manager. Something, said Gitta Stammer, was not “quite right.” He avoided meeting people; he was prone to quarreling with the farmhands, and would humiliate them. “His behavior,” she said, “was very unpleasant. We were used to getting on well with the farmhands. I called his attention to the fact that we were living in Brazil and that we shouldn’t be aggressive.”

Most tiresome were Mengele’s violent mood swings. One day he would be silent, brooding, a solitary man walking for hours. The next day, he was talkative, genial, captivating the Stammers with a sharp sense of humor. To them, it was clear that their guest was under great strain. They began to wonder who exactly was the man that Wolfgang Gerhard had brought into their lives. Their thoughts focused on the glaring inconsistencies in his background. Ultimately it was this that really aroused their suspicion. Whoever “Peter” was, his origins were not, as he had claimed, those of a man who had been farming all his life, as Gitta Stammer explained:

He used to say that his family were farmers, but as time passed we began to realize that he was an intelligent man and educated as well. For example, we, the family, used to read a lot. . . . When we made certain comments about books or radio programs, he sometimes forgot and gave an opinion well above the level of a farmer. This was a sign that something was wrong, something wasn’t true.

Then we began to realize that he was afraid of everybody. When somebody came to the farm he would always disappear. Sometimes we had visitors from São Paulo, friends or acquaintances. When this happened he looked very upset and started asking questions: “Who are these people? Are they real friends?”

You know, all this was very strange and we began to wonder why he behaved so strangely. We realized that something was wrong.24

Gitta soon discovered what was wrong. She claims it was in Serra Negra, on one of the rare occasions when there was a newspaper in the house, that she learned the true identity of “Peter Hochbichler”:

A businessman buying our fruit came to the farm and left a newspaper there. There was a piece of news about the Nazi executioners, as they said. I saw this photo there; he was a young man, about thirty or thirty-three years old. Then I thought that this face was very familiar to me, and his smile with gaps between his teeth. At that time he had such teeth. I showed him the photograph and told him that the man resembled him very much.

I told him, “You are so mysterious, you live here with us, so please be honest and tell us whether it’s you or not.” He was very upset after that, but he didn’t say anything and left. In the evening, after dinner, he sat very quiet. Suddenly he said, “Well, you’re right. I live here with you and therefore you have the right to know that unfortunately I am that person.”25

Geza Stammer was at the farm the weekend when Mengele admitted his true identity. He claims he was “very nervous, very upset,” that he wanted to immediately contact Wolfgang Gerhard and arrange to move Mengele. But since there was no telephone at Serra Negra, Geza had to wait for his next trip to São Paulo, nearly a week later. Gitta recalls, “We didn’t want to take any risks; we weren’t interested in politics; we didn’t want any confusions; we wanted to live our life without problems.”

In São Paulo Geza Stammer told Gerhard that he considered hiding Mengele “very dangerous.” “My husband told Gerhard that we were afraid, scared to keep a man hunted all over the world,” Gitta said. “Gerhard tried to calm us down by saying that no one would find out. He said we ought to be happy because before Mengele lived with us we were nothing. ‘Now there is something important in your life,’ he told us.”26 Gerhard urged the Stammers to be patient. He promised to contact the Mengele family directly, arrange to move Mengele, and then come back to the Stammers when everything was resolved.

Mengele’s younger brother, Alois, who was running the family firm in Günzburg, dispatched his old schoolfriend and most trusted confidant, Hans Sedlmeier, to Brazil to act as peacemaker. Gitta remembers what happened next: “One month later he [Gerhard] came over, by car, and brought an old man with him. This man was introduced to us as Mr. Hans, who came directly from Germany. Gerhard said the less we knew about him, the better.”

Sedlmeier brought with him  2000, which Geza Stammer changed into Brazilian cruzeiros. He stayed with the Stammers in Serra Negra for two days. According to Gitta, although at first resistant, Hans eventually “promised to do everything to find another place for him [Mengele].”

2000, which Geza Stammer changed into Brazilian cruzeiros. He stayed with the Stammers in Serra Negra for two days. According to Gitta, although at first resistant, Hans eventually “promised to do everything to find another place for him [Mengele].”

Yet Sedlmeier did not keep his promise. Mengele stayed with the Stammers and “the problems got worse.” Gitta recalls the deteriorating situation:

During this period of time, Peter was very upset, very nervous. Actually, it was very difficult to deal with him. Whenever we asked something he gave us an aggressive answer. He used to say, “What do you think? This isn’t a simple matter. There are many things at stake.” He almost accused us of being the cause of his misfortune.27

Once more, the Stammers turned to Gerhard to find a way out, this time saying they were considering betraying him to the authorities. Gerhard’s response was blunt, one that sounded to the Stammers like a threat. Gitta recalls:

Gerhard said, “Do you really think it might be better that way? You should be very careful, because if you do anything against him, you’ll have to take the consequences because he lives here with you. You should think about the future of your children. This is not so simple as you imagine. There are many obstacles, much difficulty.”28

The sudden decline in their relationship caused by the revelation of his identity plunged Mengele into anxiety over his future:

Again, outside flowers and trees give joy to that tired old heart. The cold wind whistles around the house and in my heart there is no sunshine either.29

For solace, Mengele immersed himself in studying flowers and trees and writing what he called his “childhood opus”:

That might be interesting later, looking back on them, on how everything came to be. I write them for my sons, R and K [Rolf and Karl Heinz], who will get to know much less about the past of the family than D [Dieter].30*

He became more and more self-obsessed, devoting no less than forty pages of this “childhood opus” to his own birth, including one and a half pages about the placenta, a phenomenon that caused Professor Norman Stone, the Oxford historian, to remark that Mengele’s diaries were marked by “isolation, vanity, narcissism and nastiness.”31

Yet despite the confrontation created by the revelation of Mengele’s true identity, the Stammers remained loyal to him. Despite the risks they took in harboring Mengele and the abuse they endured from him, the Stammers stayed true to him for the rest of his life. They never breathed a word to the police, even after relations became so bad between them in 1975 that they went their separate ways. Nor did they consider going to the police after Wolfgang Gerhard had left Brazil in 1971 and was no longer a threat. Furthermore, the Stammers helped Mengele in his property deals right up to his death.†

The Stammer loyalty at first seems illogical. During the years they knew him, Mengele never threatened the Stammers. Nor were they paid direct protection money by the Mengele family in Günzburg. “If we had considered this necessity with G and G [Geza and Gitta Stammer] you might still have been together,” Hans Sedlmeier wrote to Mengele years later, after he and the Stammers had split.32 But the mystery of why the Stammers never gave Mengele up has several explanations. First, Mengele had become their business partner. He provided substantial capital that allowed the greedy Stammers to buy larger and better farms. They became financially dependent on him. Second, although a difficult person, Mengele’s views were not so alien to their own. Gitta Stammer herself betrayed her own brutal historical perspective of the Holocaust when she tried to rationalize Nazi crimes. “The Germans thought that the Jews were working against Germany, so they had to get rid of them,” she said. And she accepted Mengele’s word that he had never conducted experiments.

Finally, and maybe most important, Gitta’s unswerving loyalty to Mengele appears to be the result of a love affair between them. José Osmar Siloto, who helped harvest the coffee crop, said Mengele and she were “always together. They walked everywhere together and were always sitting and talking to each other.” Ferdinando Beletatti, who worked on the farm, said:

Mr. Stammer seldom came to the farm. Their children once told me that Peter and Gitta locked themselves in the bedroom to be by themselves, making it clear they had a romance.33

Wolfram Bossert, who sheltered Mengele later, says there was an “erotic relationship between Gitta and him [Mengele].” Evidence of the relationship is also scattered throughout Mengele’s diaries. He wrote of the “beautiful” Gitta, and dedicated love poems to her:

Quiet Love

We only met so late,

When we both had experienced how bitter life could be.

Your love is never loud,

And quiet your words and gestures,

A fine smile, our secret knowledge.

Yet Gitta tearfully denies she ever had an affair with Mengele. She claims he “satisfied his sexual desires by having brief affairs with almost every young female farmhand we hired.”34 But Gitta’s assertion that Mengele’s only sexual outlet was with local farm girls is contradicted by an episode recalled by Wolfram Bossert:

On one of my visits to the villa, I saw that a few girls had been invited to celebrate the coffee harvest, and one of them was a very pretty morena—that is to say, a dark girl. And Gerhard teased him [Mengele] later, saying that he had, surely, had a fling with her. Mengele got very cross and replied that he, as a race scientist, would never have an affair with a colored woman. You see, that’s how persistent and stubborn he was in pursuing his course. Once he had made up his mind on something, he would pursue the matter without compromise.35

Despite Gitta’s denials, the evidence is that Mengele and Gitta had an affair, which lasted until 1974, when she lost interest, according to Bossert, during her menopause.

Satisfactory though the carnal side of life might have been, Mengele’s prospects for a more fulfilling lifestyle looked distinctly dim. On June 1, 1962, he learned that his colleague Adolf Eichmann had been hanged at Israel’s Ramale jail. Most of Mengele’s invective was directed at postwar Germany, which he saw as the real villain in Eichmann’s fate:

The event which I learned of days later didn’t surprise me, but I was deeply affected. One is tempted to draw comparisons, then one drops it again because one is startled by the reality of the path of history over the last 2000 years. His people have betrayed him miserably. As a human this has been the most difficult and upsetting part. Herein lies the core of the problem of the case! One day the German people will be very ashamed of themselves! Otherwise they will never feel shame.36

Determined that Eichmann’s fate should not befall him, Mengele became obsessed with his own security. Whenever Mengele went for a walk he took a large number of dogs with him. “He had about fifteen strays,” Ferdinando Beletatti, the ex-farmhand, said, “but he never went far from the farm.” Beletatti was also ordered to build an eighteen-foot wooden watchtower. When he asked Gitta Stammer why, she said that she and her husband wanted it for bird-watching, but he never saw them use it. The construction was fastidiously supervised by Mengele. “He was very abrupt,” said Beletatti. “He spoke to me only when he was giving me orders on how to build it.”

For hours on end Mengele scanned the countryside from the watchtower. Perched on top of a hill, the farm afforded him a perfect view of the surrounding fields and dirt tracks. He also had a clear sight of Lindonia, the nearest town, five miles away. There were no guns, no dogs or electrified fences, no praetorian guard—just a middle-aged man with a pair of binoculars anxiously surveying the scene. “A lot of people find it strange that Mengele managed to survive for so long without the aid of an organization or security,” said Wolfram Bossert, who became one of Mengele’s few friends. “I think he managed that exactly because he had no security apparatus.”37

Mengele’s obsession with security weighed on his mind and cast him into deep depressions. At such times, he believed his capture was inevitable, as his diary showed: “Out of the beautiful house of our ideal plans, one stone after the other breaks down, and the final collapse comes nearer and nearer.” He even dreamed of death: “Occasionally, I dream of a double-headed guillotine.”

Yet Mengele need not have worried. Certainly by the summer of 1962, he had fooled the West Germans, who thought he was probably still in Paraguay. On August 11 the ambassador in Asunción, Eckart Briest, formally requested Mengele’s extradition. In November Judge Vincente Ricciardi of the Paraguayan Fourth Judicial Court issued a warrant for Mengele’s arrest after the West German embassy said that their information placed “Josef Mengele as either visiting Asunción or in the Alto Parana region.”38 The Paraguayans knew, however, that the bird had already flown. Stroessner himself had actually responded quite helpfully to Briest. According to one reliable source in the interior ministry, Stroessner told the ambassador, “I don’t know about extradition, but I can arrest him.” Stroessner then telephoned the interior minister, Edgar Ynsfran, and ordered that Mengele be arrested. Ynsfran, recalling that he had expedited Mengele’s citizenship at Rudel’s request, telephoned the ex-Luftwaffe ace, who told him, “Forget it, he’s gone to Brazil.” As a precaution, the warrant was issued all the same.39

The warrant put an end to any idea Mengele may have had of using Paraguay as a sanctuary had his luck run out in Brazil. Even his friend Alban Krug was powerless to help. Although Krug was an influential man, he did not have an open door to Stroessner’s palace; in fact he found the president quite intimidating. Once when Krug was summoned to the palace for a friendly chat, he mistakenly felt the atmosphere had relaxed enough for him to tell the president that many people in southern Paraguay felt the government was too remote. He also ventured to say that some of Stroessner’s ministers were “assholes.” When Krug realized he had gone too far, he began to feel uneasy and indicated that he would like to leave. But Stroessner kept him there for hours. Finally, when the president had finished, he walked Krug to the door, put his hand across Krug’s broad back, and warned him, “If these intriguers ever make a revolt against me I will resist until not a stone is left in Asunción.”

Since Stroessner seemed prepared, for the moment anyway, to have Mengele arrested, Krug could not risk giving him shelter, particularly since he was unaware that the president had ruled out extradition.

As for the Israelis, by the end of 1962, their hunt for Mengele had virtually ground to a halt, a casualty of competing priorities in a fast changing world. Once again the survival of Israel was threatened by President Gamal Nasser of Egypt. The cruel irony is that the hunt came to an end just as the Mossad made a spectacular breakthrough—one which in hindsight may well have ended in Mengele’s capture.

* According to papers in the local property registration office, the Stammers never owned the farm at Nova Europa. It was purchased by an Austrian couple, Anton and Edeltraud Wladeger, on May 20, 1953. When it was “sold” by the Stammers to Jorge Miguel Marum in 1962, the deed was transferred directly from the Wladegers, and the Stammers appeared nowhere on the ownership records.

* Rafi Eitan became the subject of headlines in the United States during November 1985, but not for his work on Mengele. Instead, he was identified as the chief of the Israeli intelligence unit that had spied on the United States government. The resulting investigation ended in the arrest of U.S. military officer, Jonathan J. Pollard, and a public apology from Israel.

* The South American press was riddled with sensational but false Mengele stories for the remainder of 1962. The most imaginative claimed that Mengele had been kidnapped by Israeli agents and was on a banana boat steaming for Haifa. The boat docked in Israel in front of a full complement of the press corps. It was filled with exotic fruit but, alas, no Mengele.

* Dieter Mengele, the son of Mengele’s younger brother, Alois, was at that time the only Mengele son living with his father.

† In 1985, when Gitta Stammer was asked if she would again provide shelter to Mengele, knowing what she does now, she said “I think . . . yes . . . politically speaking, in general, we help everybody.”