The BBC has found a story: ‘“Threefold variation” in UK bowel cancer rates’. The average death rate across the UK from bowel cancer is 17.9 per 100,000 people, but in some places it’s as low as nine, and in some places it’s as high as thirty. What can be causing this?

Journalists tend to find imaginary patterns in statistical noise, which we’ve covered many times before. But this case is particularly silly, as you will see, and it has a heartwarming, nerdy twist.

Paul Barden is a quantitative analyst. He saw the story, and decided to download the data and analyse it himself. The claims come from a press release by the charity Beating Bowel Cancer: they’ve built a map where you can find your own local authority’s bowel cancer mortality rate and get worried, or reassured. Using a ‘scraping’ program, Barden brought up the page for each area in turn, and downloaded the figures. By doing this he could make a spreadsheet showing the death rate in each region, and its population. From here things get slightly complicated, but very rewarding.

We know that there will be random variation around the average mortality rate, and also that this will be different in different regions: local authorities with larger populations will have less random variation than areas with smaller populations, because the variation from chance events gets evened out more when there are more people.

You can show this formally. The random variation for this kind of mortality rate will follow the Poisson distribution (a bit like the bell-shaped curve you’ll be familiar with). This bell-shaped curve gets narrower – less random variation – for areas with a large population.

So, Barden ran a series of simulations in Excel, where he took the UK average bowel cancer mortality rate and a series of typical population sizes, and then used the Poisson distribution to generate figures for the bowel cancer death rate that varied with the randomness you would expect from chance.

This random variation predicted by the Poisson distribution – before you even look at the real variations between areas – shows that you would expect some areas to have a death rate of seven, and some areas to have a death rate of thirty-two. So it turns out that the real UK variation, from nine to thirty-one, may actually be less than you’d expect from chance.

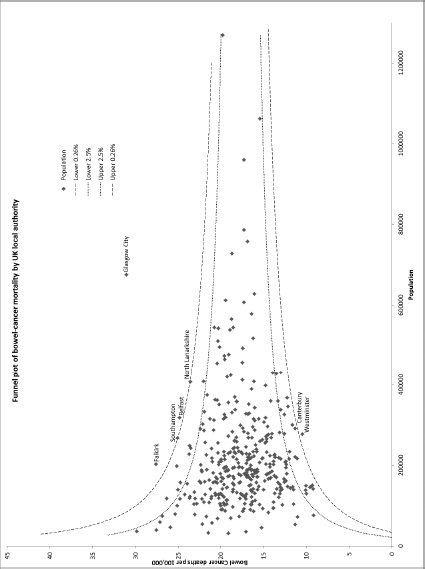

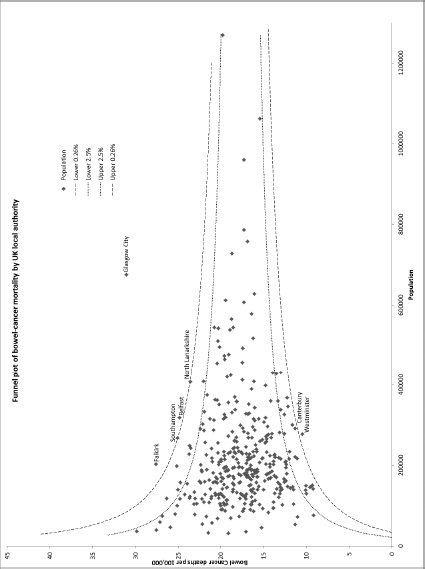

Then Barden sent his blog to David Spiegelhalter, a Professor of Statistics at Cambridge, who runs the excellent website Understanding Uncertainty. Spiegelhalter suggested that Barden could present the real cancer figures as a funnel plot, and that’s what you see opposite.

I cannot begin to tell you how happy it makes me that Spiegelhalter, author of Funnel Plots for Comparing Institutional Performance – the citation classic from 2005 – can be found by a random blogger online, and then collaborate to make an informative graph of some data that’s been over-interpreted by the BBC.

But back to the picture. Each dot is a local authority. The dots higher up show areas with more deaths. The dots further to the right show ones with larger populations. As you can see, areas with larger populations are more tightly clustered around the UK average death rate, because there’s less random variation in bigger populations. Lastly, the dotted lines show you the amount of random variation you would expect to see, from the Poisson distribution, and there are very few outliers (well, one main one, really).

Excitingly, you can also do this yourself online. The Public Health Observatories provide several neat tools for analysing data, and one will draw a funnel plot for you, from exactly this kind of mortality data. The bowel cancer numbers are in the table above. You can paste them into the Observatories’ tool, click ‘calculate’, and experience the thrill of touching real data.

In fact, if you’re a journalist, and you find yourself wanting to claim one region is worse than another, for any similar set of death rate figures, then do feel free to use this tool on those figures yourself. It might take five minutes.

The week after this column came out, a letter was published from Gary Smith, UK News Editor at the BBC. It said: ‘The BBC stands by this report as an accurate representation of the figures, which were provided by the reputable charity Beating Bowel Cancer. Dr Goldacre suggests the difference between the best- and worst-performing authorities falls within a range that could be expected through change [I don’t suggest this: I demonstrate it to be true]. But that does not change the fact that there is a threefold difference between the best and worst local authorities.’ This is a good example of the Kruger-Dunning effect: the phenomenon of being too stupid to know how stupid you’re being (discussed, if you’re keen to know more, in Bad Science, here).