This week a man called Martin Gardner died, aged ninety-five. His popular maths column in Scientific American (and fifty books on the subject) spanned the decades, but in 1952 he published a book, In the Name of Science, on pseudoscience, quacks and credulous journalists. How much do you think has changed over sixty years?

Immanuel Velikovsky had just published his best-selling book Worlds in Collision, explaining how a comet which flew out of Jupiter, and zipped past the earth twice, had then caused the earth to stop spinning, so that the Red Sea would part at precisely the moment when Moses held out his hand. Cars and planes, he explained, are propelled by fuel refined from ‘remnants of the intruding star that poured fire and sticky vapour’ on the earth. Several years later the comet returned: a precipitate of carbohydrates that had formed in its tail fell to earth in the form of Manna which kept the Israelites fed for forty years.

The science editor of the New York Herald Tribune called this book ‘a magnificent piece of scholarly research’. But while the correspondents of Reader’s Digest and Harper’s Magazine heaped praise upon Velikovsky, his publishers received a flood of letters from scientists. A boycott was organised of all their academic textbooks, the editor who commissioned the book was sacked, and Velikovsky moved to Doubleday, which had no textbook imprint to worry about (and was delighted to have a best-seller).

This was an era when serious people took bullshit more seriously. While today homeopathy is taught in universities eager to serve popular demand, the most notable predecessor to Gardner’s Fads and Fallacies was Higher Foolishness, written in 1927 by David Starr Jordan, the first president of Stanford University. The American Medical Association campaigned hard against press publicity for quacks, and bullshit seemed more pressing. There were signs of a relapse into religious fundamentalism, driven in part by bizarre beliefs such as Velikovsky’s, and the indulgence of pseudoscience was playing its part, live and in colour, in some very bad situations.

The bizarre racial theories of the Nazi anthropologists were fresh in the memory, and in Russia things were little better. During the 1930s, communism had turned its back on evolution and Mendelian inheritance, preferring the theories of Trofim Lysenko on the inheritance of acquired characteristics, which sat better with its notions of heritable self-improvement. Sadly, Lysenkoism ran contrary to the experimental evidence, and could only be maintained by sending Russia’s geneticists to die in Siberian labour camps, so that by 1949 Russian children were being taught that the revolution had shattered the hereditary structure of the Soviet people, with each generation growing up finer than the last as a result.

But alongside concrete outcomes like death camps, Gardner never loses sight of the parallel tragedy. Harper’s Magazine – notable for its recent promotion of Aids denialism – was then pushing Gerald Heard’s book Is Another World Watching?, which explained that tiny flying saucers have visited earth, piloted by two-inch super-intelligent bee people from the planet Mars. At a time when the shelves were filled with magazines called things like Life, True and Doubt, a widespread passion for knowledge was being regularly derailed into nonsense.

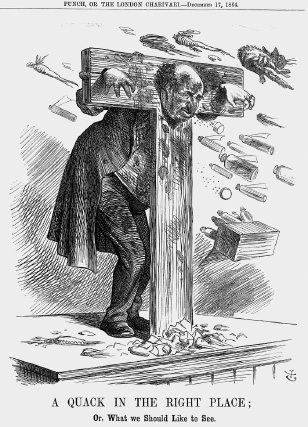

So, Gardner has the same fun we have with the homeopaths (while complaining that Marlene Dietrich is a fan), the vitamin-pill peddlers, the anti-vaccination campaigners and the chiropractors, and above all captures their character, which endures: the self-imposed isolation from the corrective of academic criticism, the persecution complex, the grandiosity, the denouncement of critics as being in the pay of darker forces, and the enjoyment of jargon like ‘electroencephaloneuromentimpograph’, a machine devised by the son of the founder of chiropractic.

I have a copy of the first edition of In the Name of Science (they’re cheap), but subsequent editions are much more desirable, because they include a supplementary introduction where Gardner takes delight in his hate mail, and especially the mutual indignation that each target expresses at being unfairly associated with the others, whom they regard as the true charlatans.1 In sixty years nothing has changed. The best we can hope for is the simple, enduring pleasure of baiting morons.