3

Bourbon Drives the Development of Trademark and Brand Name Rights

Bourbon’s imprint on commercial rights begins with the origin of a phrase uttered every day around the world: brand name. Many people want to wear only “brand-name clothes,” while generic or store brand clothes are considered inferior. Companies spend billions of dollars to develop and promote their “brand identity.” Forbes reported that Lego was named the most powerful brand name in the world in 2017, and we all recognize brands such as Google, Nike, Apple, and Coca-Cola. We also have certain expectations of high quality with these famous brands, and we use them to distinguish companies and products from their rivals.

But how did a product or company name come to be known as a brand? Bourbon has the answer. Beginning in the 1800s, federal law required that “the name of the distiller shall be stamped or burned upon the head of every package of distilled spirits put into bonded warehouses, and this must not be erased until the package is empty.”1 The phrase brand name was born from this federal law and the branding of barrels by distillers, and then it spread to other manufactured goods.

Because whiskey was often sold by the barrel, the brand on the barrelhead was important. (Selling by the barrel created its own problems, like refilling with lesser-quality bourbon or blending with lesser-quality bourbon or watering it down to make it last longer. Those issues were addressed by the innovation of bottling with signed seals over the closure.) A barrel branded with Old Crow could be sold for a higher price, whether sold in bulk or upon resale. So, just as brand names today are highly sought after and protected, early distillers fought hard to protect their brand names.

Bourbon litigation helped define the parameters of brand name protection, including by limiting the use of one’s own family name. The Labrot & Graham Distillery is what Brown-Forman called its distillery in Woodford County, Kentucky, when it began producing Woodford Reserve, although it has since renamed the distillery the Woodford Reserve Distillery. The original name of the distillery, however, plowed new ground for brand name rights.

In October 1880 the grandson of the original owner of the earliest distillery on the Woodford Reserve property sued a partnership of French wine producer Leopold Labrot and Kentucky businessman James H. Graham. The ruling from this lawsuit provides an invaluable outline of some of the earliest distilling operations in Kentucky and the perfection of the bourbon distilling process by James Crow.

According to Brown-Forman’s National Historic Landmark Application for the Labrot & Graham’s Old Oscar Pepper Distillery, it described the property as a “bourbon whiskey manufacturing complex in Woodford County, Kentucky, standing on a site that has been used for the conversion of grain into alcohol since 1812, when Elijah Pepper, a farmer-distiller, established his 350 acre farm.”2

Elijah Pepper, a Virginian who moved to Kentucky in 1797, established his first distillery behind the Woodford County Courthouse in Versailles around 1810.3 By 1812, however, Elijah Pepper had acquired hundreds of acres along Glenn’s Creek, where he built his homestead, a gristmill, and a distillery and where he established his family farm.4 Elijah Pepper died in early 1831, and the distillery was then operated by his son, Oscar N. Pepper.5 After Oscar completed a new limestone distillery building in 1838, the distillery became known as the “Old Oscar Pepper Distillery.”6 By 1833, and through 1855 (except for two years), Oscar Pepper employed the venerable James Crow as his distiller, and the distillery was renowned for its bourbon and for refining and defining what we know as bourbon today.7

James Crow died in April 1856, but because of the fame gained by the Crow brand, Old Crow bourbon continued to be produced at the Old Oscar Pepper distillery by W. F. Mitchell, who had worked with and then succeeded James Crow as distiller.8 Oscar Pepper died in June 1865, and it appears that the property containing the distillery was transferred by the estate to Oscar’s youngest of seven children, O’Bannon Pepper.9 O’Bannon was still a minor, which meant that Oscar’s wife, Nannie, controlled the distillery. She leased the distillery property in 1870 to Gaines, Berry & Company of Frankfort, although James E. Pepper—Oscar’s eldest son—may have managed the distillery.10 Gaines, Berry & Company produced “Old Crow Whiskey,” called the distillery the “Old Crow Distillery,” and continued to employ W. F. Mitchell as their distiller.11

James Pepper sued his mother in 1872 to gain control of the distillery property, and after succeeding in taking control of the distillery, he then partnered with Col. E. H. Taylor Jr., who had parted ways with Gaines, Berry & Company, to make improvements to the distillery and continue operations.12 The case of Pepper v. Labrot picks up where the National Historical Landmark Application leaves off.13 In 1874 Gaines, Berry & Company took the Old Crow trademark along to another of its distillery operations, leaving James Pepper with the Old Oscar Pepper brand, also known as O.O.P. “bourbon.”14

James Pepper experienced financial hardships and was declared bankrupt in 1877.15 Through the bankruptcy Colonel Taylor took sole ownership of the Old Oscar Pepper Distillery.16 But Colonel Taylor—who owned many other distilleries—experienced his own financial ruin shortly thereafter, even having to leave Kentucky to avoid his creditors.17 This led to the transfer of the Old Oscar Pepper Distillery to George T. Stagg.18 In 1878 it was sold to Labrot & Graham.19

James Pepper’s financial fortunes seemed to have reversed, and he built a new distillery on Old Frankfort Pike in Lexington, Kentucky.20 There he hoped to continue to trade on his father’s name and the tremendous reputation achieved by his father and James Crow.21 The problem was that Labrot & Graham was using the Old Oscar Pepper brand and was still calling the distillery the “Old Oscar Pepper Distillery.”22 James believed that only he should be able to use the Pepper name, and in 1880 he filed a lawsuit in federal court to gain back part of what he had lost in bankruptcy.23

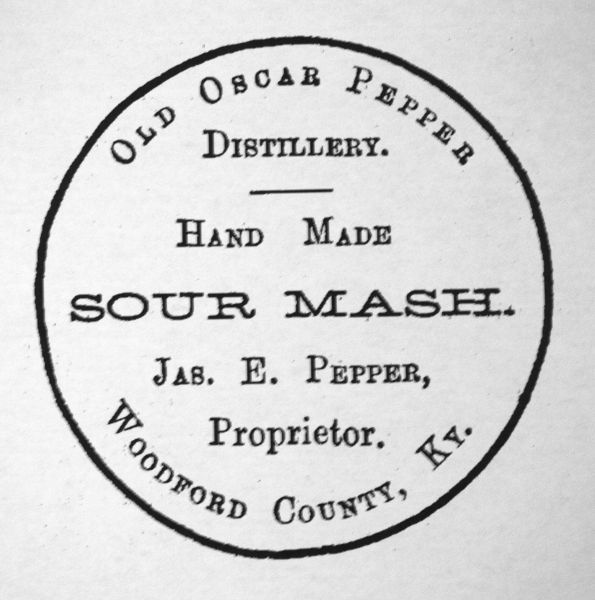

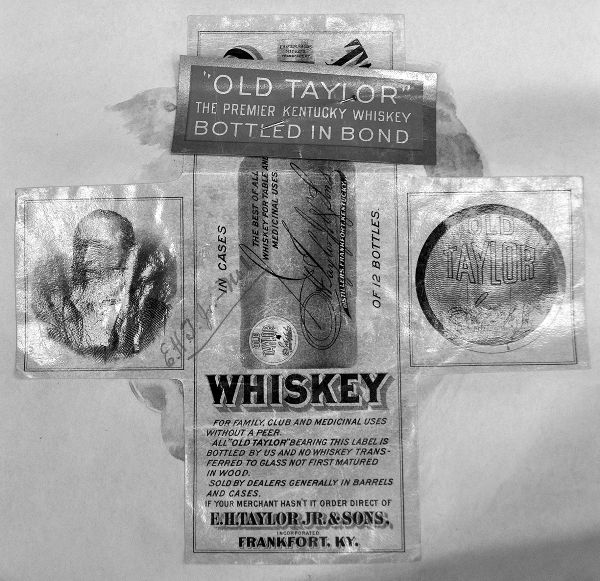

Fig. 1. Old Oscar Pepper Barrelhead–James Pepper. Pepper v. Labrot, 1881.

After reciting the history of the property and the claims and counterclaims being asserted, the court noted and relied upon an advertisement used by James Pepper from the period when he owned the Old Oscar Pepper Distillery. James credited his bourbon’s quality to his father’s distillery and the terroir: “Having put in the most thorough running order the old distillery premises of my father, the late Oscar Pepper (now owned by me), I offer to the first-class trade of this country a hand-made, sour-mash, pure copper whisky of perfect excellence. The celebrity attained by the whisky made by my father was ascribable to the excellent water used (a very superior spring), and the grain grown on the farm adjoining by himself, and to the process observed by James Crow, after his death by William F. Mitchell, his distillers. I am now running the distillery with the same distiller, the same water, the same formulas, and grain grown upon the same farm.”24

Despite Oscar Pepper’s much earlier ownership of the distillery, James alleged that the name Old Oscar Pepper had not been used until 1874.25 He claimed that the brand that he burned on barrel-heads was his trademark (fig. 1).26

As might be expected, evidence was presented to the court proving that between 1838 and 1865, while Oscar Pepper operated the distillery, it was already commonly known as the “Oscar Pepper Distillery.”27 Additionally, because of the fame of James Crow and his bourbon—known as “Old Crow”—the distillery was also known as the “Old Crow Distillery,” a name that continued in use after James Crow died in 1856 and after Oscar Pepper died in 1865.28 Even Gaines, Berry & Company marketed themselves as “Lessees of Oscar Pepper’s ‘Old Crow’ Distillery.”29

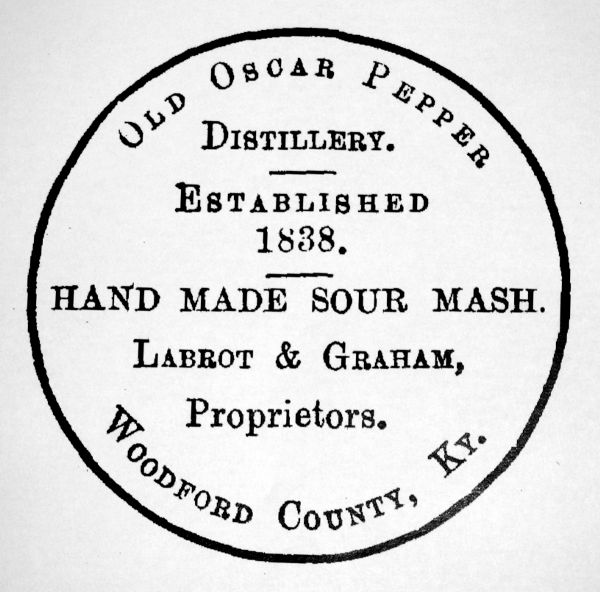

After James Pepper lost the property and after the eventual acquisition by Labrot & Graham, Labrot & Graham used a similar brand for its barrel-heads and specifically used the name Old Oscar Pepper Distillery (fig. 2).30 Labrot & Graham responded to the lawsuit by explaining that it was using the name Old Oscar Pepper Distillery properly because the distillery it now owned was called the “Old Oscar Pepper Distillery.”31 The court posed two questions: should Labrot & Graham be forced to change the name of a distillery that it purchased and denied the right to call the distillery by its name, and, conversely, should James Pepper be allowed to continue to use the name of his father’s former distillery, when his new bourbon was not distilled there?32

As might be expected by the way the court presented these questions, Labrot & Graham won the case.33 The court ruled that reference to Old Oscar Pepper’s Distillery meant the place of production and was not a trademark.34 Moreover, James could not truthfully use the phrase since he no longer owned the Old Oscar Pepper Distillery.35

Fig. 2. Old Oscar Pepper Barrelhead–Labrot & Graham. Pepper v. Labrot, 1881.

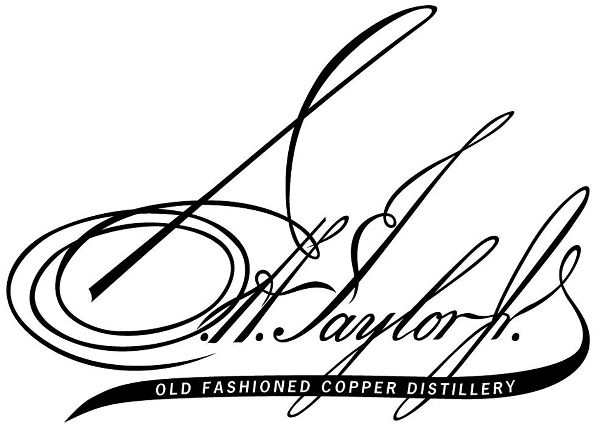

While Col. E. H. Taylor Jr. was only tangentially involved in Pepper v. Labrot, he made his mark on bourbon law through several of his own cases. In fact, a series of cases from the late 1800s and early 1900s helped establish the boundaries for trademark protection in a name, as illustrated through Colonel Taylor’s fanciful script signature (a trademark still used today).

Colonel Taylor acquired his first distillery on the banks of the Kentucky River in 1869, on property that is now known as “Buffalo Trace.” Colonel Taylor christened his distillery the “O.F.C.” (Old Fire Copper or Old Fashioned Copper) Distillery, and there he produced the famous O.F.C. whiskey brand. While O.F.C. was the focus, Colonel Taylor adopted a script signature as part of his branding (fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Edmund H. Taylor Jr. script signature. Geo T. Stagg Co. v. Taylor, 1894.

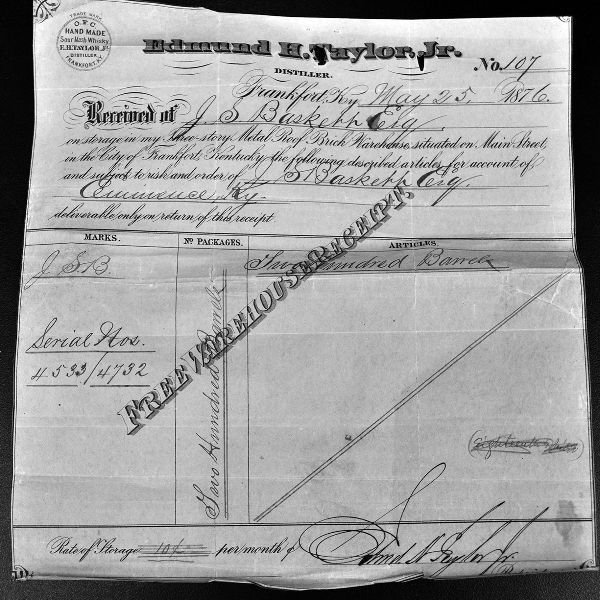

As described in Newcomb-Buchanan Co. v. Baskett, Colonel Taylor’s troubles were brewing at least by the spring of 1875.36 Just months before the running of the first Kentucky Derby, Taylor sold 150 barrels to J. S. Baskett, a Henry County farmer who raised Hereford cattle and was a banker—both passions he shared with Colonel Taylor.37 Baskett paid for the bourbon and paid the taxes, so the barrels were to be moved from the bonded warehouse at the O.F.C. to a free warehouse (fig. 4).38

Instead of honoring his sale to Baskett, Colonel Taylor sold the same 150 barrels to Newcomb-Buchanan Company (one of the largest distillery groups in Kentucky at the time) to cover debts Colonel Taylor owed.39 Newcomb-Buchanan, in turn, sold 25 of Baskett’s barrels and credited Taylor’s account, shipped another 101 of Baskett’s barrels to George T. Stagg in St. Louis to cover debt Colonel Taylor owed to Stagg, and still had the remaining barrels when Baskett came looking for his bourbon during the summer of 1877.40

Fig. 4. Free warehouse receipt from E. H. Taylor Jr. to J. S. Baskett. Newcomb-Buchanan Co. v. Baskett, Oldham Circuit Court, 1879. Kentucky State Archives.

Colonel Taylor was nowhere to be found. In the Buffalo Trace Oral History Project, Colonel Taylor’s great-great-grandson says that Colonel Taylor fled to Europe and left one of his sons behind to deal with the creditors, but the court simply noted that “in May, 1877, Taylor left the state on account of pecuniary troubles,” so Baskett sued Newcomb-Buchanan.41 The Oldham Circuit Court record shows another reason that Colonel Taylor might have disappeared: the court had issued an arrest warrant against him, as requested by Newcomb-Buchanan.42

Newcomb-Buchanan defended on the ground that it simply did not know about Baskett’s ownership of the barrels. The court of appeals ruled in favor of Baskett, reasoning that Newcomb-Buchanan never had an ownership interest in the barrels because Colonel Taylor never had the right to (re)sell the barrels in the first place, and instructed the trial court to assess damages in favor of Baskett.43 Colonel Taylor’s debt went far beyond what might be saved by a double sale, however. He needed a buyout, and he needed it fast.

In December 1877 George T. Stagg, a St. Louis whiskey merchant and a large creditor of Colonel Taylor, bought Colonel Taylor out of bankruptcy by paying twenty cents on the dollar to the creditors.44 In exchange Stagg became the owner of the O.F.C. Distillery and the O.F.C. trademark.45 Stagg leased the O.F.C. back to Colonel Taylor, and, the court noted, O.F.C. whiskey “attain[ed] a phenomenal reputation.”46 A year later the success of Colonel Taylor and Stagg allowed them to build the Carlisle Distillery next to O.F.C., and they continued to enjoy great success.47

Stagg took measures to protect the O.F.C. trade name and the business. He formed the E. H. Taylor, Jr. Company in 1879 and registered the O.F.C. trademark.48 Stagg was the president and majority shareholder of the company, and Colonel Taylor was the vice president, apparently owning just a single share.49 Importantly, the trademark registrations focused on O.F.C. and not on the use of Colonel Taylor’s name.50 In time, however, the use of Colonel Taylor’s name became more and more prominent, finally resulting in the use, in 1880, of the well-known script signature.51

The court summarized the evolution of using Colonel Taylor’s script signature on O.F.C. whiskey. Colonel Taylor (and Stagg) began by simply noting Colonel Taylor’s name, as the distiller, in normal font under the O.F.C. brand name.52 By 1881 they used what the court characterized as “the well-known and striking autograph signature of E. H. Taylor, Jr.,” using the signature to “prove” that the whiskey was genuine O.F.C. whiskey.53 But this script signature was never protected by Stagg as a trademark.54

Stagg and Colonel Taylor parted ways toward the end of 1886, and effective January 1, 1887, the split was official.55 Stagg retained the O.F.C. and Carlisle Distilleries, and Colonel Taylor acquired for himself the J. S. Taylor Distillery in Millville, Woodford County, Kentucky, which had been owned and operated by one of Colonel Taylor’s sons before becoming part of Stagg’s E. H. Taylor, Jr. Company in 1882.56

Colonel Taylor immediately formed a partnership with his sons, J. Swigert and Kenner, again using his name for the name of the business: E. H. Taylor, Jr. & Sons.57 He renamed the distillery the “Old Taylor Distillery” and immediately started using the same script signature that he had previously used with his O.F.C. bourbon, except he added & Sons.58 This is the distillery—not the O.F.C.—where Colonel Taylor solidified his legendary position in Kentucky bourbon lore. He built a castle, pioneered a new marriage between production and aesthetics, and created his namesake iconic brand (fig. 5).

Fig. 5. Old Taylor Bottled in Bond label. E. H. Taylor Jr. & Sons v. Geo. T. Stagg Co., Franklin Circuit Court, March 9, 1898. Kentucky State Archives.

In the meantime Stagg, who formed the George T. Stagg Company after his split with Colonel Taylor, was in the process of making improvements to the O.F.C. and Carlisle Distilleries, which remained idle for eighteen months.59 The court had no doubt that Stagg’s “ambitious purpose” was “to substitute his own name, or that of the corporation bearing his name, as the distiller and proprietor of the famous O.F.C. and Carlisle Distilleries.”60 However, when Stagg resumed production in January 1889, he started using Colonel Taylor’s script signature instead.61

So, Colonel Taylor sued Stagg on October 16, 1889, asking for an injunction to stop Stagg from using the company name of E. H. Taylor, Jr. Company or his script signature and for monetary damages.62 The Franklin circuit court, in Frankfort, Kentucky, noted in its 1891 judgment that Colonel Taylor had named his distillery the “O.F.C.” but that the trademarks consisted only of the O.F.C. and Carlisle names; Colonel Taylor’s script signature used on the free end of barrels and on labels was not part of the trademark.63 This ruling gave Colonel Taylor the exclusive right to use his name and script signature, and the trial court ruled that it was “untruthful” for Stagg to use Colonel Taylor’s name in any way for whiskey made after January 1, 1887.64 After an appeal by Stagg, in 1894 the Kentucky Court of Appeals agreed and sided with Colonel Taylor, prohibiting Stagg from using the script signature on any bourbon distilled after January 1, 1887 (because Colonel Taylor was the distiller before that date).65

In answering the question of whether the script signature became a trademark owned by Stagg, the court of appeals looked into the origin of the script signature and noted the testimony of Colonel Taylor and Stagg: “Stagg says that on one occasion, when Taylor was in St. Louis, the latter noticed a striking script signature on packages of imported brandy, and was impressed with the idea that the signature of the company, as written by him, would be appropriate, and look well on a barrel. Taylor suggested it. Stagg agreed with him, and it was done. . . . Taylor contends that it was a mere fancy with him, and was intended to show his personal identification with the distilling operations of the company.”66

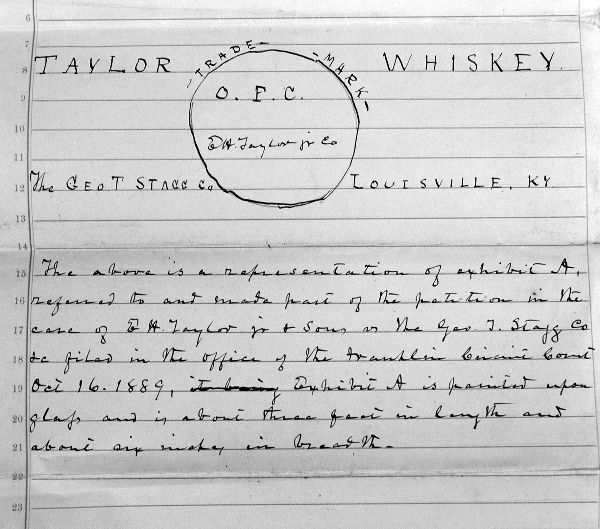

Fig. 6. O.F.C. trademark registration transferred from Colonel Taylor to Stagg, which emphasized “O.F.C.” as the essential feature. E. H. Taylor Jr. & Sons v. Geo. T. Stagg Co., Kentucky State Archives.

The court of appeals then analyzed the actual trademark registration and transfer from Colonel Taylor to Stagg, which emphasized O.F.C. as the essential feature, as shown in a handwritten exhibit from the trial (fig. 6).67

The name of Colonel Taylor, the court held, merely identified him as the distiller, and the court expected any subsequent distiller’s name to be substituted for that of Colonel Taylor.68 In fact, the court of appeals recognized that any continued use of Colonel Taylor’s name as the distiller—after a time when he ceased to actually be the distiller—would have been improper.69

But just like the Franklin circuit court, the court of appeals did not award any monetary damages, and Colonel Taylor was not satisfied with just an injunction.70 He wanted money, so he asked the court to reconsider its decision about damages.71 In 1896 the Kentucky Court of Appeals rejected the damages claim for a second time, and maybe in an effort to quiet Colonel Taylor’s complaints, the court noted that its 1894 ruling in his favor “was with some reluctance.”72 Nevertheless, the court of appeals asked the lower court to examine the issue of damages again.73

Colonel Taylor remained persistent, and he continued to push the issue of damages with the Franklin Circuit Court, where he won on the issue and was finally awarded monetary damages.74 Showing the same resolve as Colonel Taylor, the Geo. T. Stagg Company appealed to the Kentucky Court of Appeals.75 Finally, in 1902—after nearly thirteen years of litigation—Colonel Taylor lost the damages issue for good.76 His loss might have been predictable, given the court’s 1894 brushback, but this litigation story shows that persistence was certainly one of Colonel Taylor’s character traits.

Persistence, of course, remains an American trait too, and persistence was needed over one hundred years later by Maker’s Mark to fight back against a popular tequila brand and the world’s largest spirits company, over one of bourbon’s most recognizable trademarks—the dripping red wax of Maker’s Mark. Ever since Maker’s Mark began production in 1958, after Bill Samuels Sr. broke from Country Distillers and struck out on his own, Maker’s Mark has capped its bottles with a red wax seal that partially covers the neck of the bottle and drips down to the bottle’s shoulder. As noted by the district court in Maker’s Mark Distillery, Inc. v. Diageo North America, Inc., “That design was the brainchild of Margie Samuels, mother of Maker’s Mark’s current president Bill Samuels, who was still at home when his mother perfected the dripping wax in their family’s basement.”77

Maker’s Mark registered this trademark in 1985, describing it as the “wax-like coating covering the cap of the bottle and trickling down the neck of the bottle in a freeform irregular pattern.”78 This move coincided with an extensive marketing push by Maker’s Mark, and through even more marketing ($22 million annually in 2010), the company eventually reversed its ratio of selling 90 percent of its bourbon in Kentucky to selling 90 percent of its bourbon outside of Kentucky (fig. 7).79

Problems arose in 2001, when Diageo—the world’s largest spirits company—marketed Jose Cuervo Reserva de La Familia, which used a red free-form waxlike seal cap.80 After Maker’s Mark filed its complaint in 2003, Jose Cuervo started snipping the wax tendrils on the Reserva de La Familia bottles, although it continued to use a red wax seal. Diageo also used the lawsuit to go on the offensive, asking the court to cancel Maker’s Mark’s trademark on the ground that it was functional and because other alcoholic beverages were already being sealed in colorful wax.81 A six-week trial was held beginning in November 2009.82 Bill Samuels testified, along with Master Distiller Kevin Smith, company finance and marketing officers, and even experts on issues such as spirits markets and consumer recognition of brands, damages, wax composition, Maker’s Mark memorabilia, and bottle closures.83

On April 2, 2010, the district court ruled that Diageo had infringed on Maker’s Mark’s trademark, and therefore it issued an injunction in favor of Maker’s Mark.84 But the court refused to award any monetary damages because Maker’s Mark did not prove that anyone had actually been confused or that it had lost any sales, although the court still awarded nearly $67,000 to Maker’s Mark to offset its attorneys’ fees and expenses of bringing the lawsuit.

The case was far from over, however. Diageo appealed to the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit.85 On appeal Diageo argued that purchasers of Jose Cuervo Reserva de la Familia—“a $100 per bottle luxury tequila”—were unlikely to ever be confused that their prized tequila was affiliated with an inexpensive bourbon like Maker’s Mark, especially Cuervo consumers, who “generally are tequila connoisseurs who spend more than $100 for a bottle of tequila, or $16–20 for a drink in a bar.”86

Fig. 7. Maker’s Mark iconic red dripping wax trade dress. Author’s collection.

Plus, Diageo argued, Maker’s Mark was hardly the first company to use a dripping wax seal on a bottle.87 Wax seals have been used for centuries, and Diageo emphasized that Bill Samuels admitted that the inspiration for the Maker’s Mark free-form wax coating was old Cognac bottles with wax seals and an irregular or uneven edge.88 Maker’s Mark’s experts admitted that numerous other bourbons and other spirits have used red wax seals or dripping wax seals.89 Wines and even beers have also used wax seals, many of them red and many with tendrils.90 Nonalcoholic products such as olive oil and vinegar have also used red dripping wax seals.91 So, why should Maker’s Mark get special protection?

The answer to that question became evident by reading only the opening lines of the Sixth Circuit’s May 9, 2012, ruling, emphasizing that while bourbon has distinct economic force, it also is entitled to protect its assets in the courts: “Justice Hugo Black once wrote, ‘I was brought up to believe that Scotch whisky would need a tax preference to survive in competition with Kentucky bourbon.’ Dep’t of Revenue v. James B. Beam Distilling Co., 377 U.S. 341, 348–49 [1964] (Black, J., dissenting). While there may be some truth to Justice Black’s statement that paints Kentucky bourbon as such an economic force that its competitors need government protection or preference to compete with it, it does not mean a Kentucky bourbon distiller may not also avail itself of our laws to protect its assets.”92

The outcome became even clearer when the court gave a veritable history lesson about bourbon, discussing:

- the origin and history of bourbon;

- the difference between “whiskey” and “bourbon”;

- the different spellings of whiskey and whisky;

- bourbon mash bills and Dr. James Crow’s perfection of the sour mash method;

- early marketing of bourbon and early fans, like Ulysses S. Grant and Henry Clay;

- the rise and fall of rectifiers and President William Taft’s 1909 interpretation of the 1906 Pure Food and Drug Act;

- distiller consolidation after the repeal of National Prohibition;

- more name-dropping of bourbon fans, like President Harry S. Truman and Ian Fleming, who reportedly switched from martinis to bourbon;

- the action of Congress, in 1964, to designate bourbon as a “‘distinctive product of the United States,’ 27 C.F.R. § 5.22(l)(1), and prescribed restrictions on which distilled spirits may bear the label ‘bourbon’”;

- the Samuels family’s important role in the history of bourbon (“Maker’s Mark occupies a central place in the modern story of bourbon”), including having been distillers since the 1783; and

- Maker’s Mark’s rise, especially after the now legendary 1980 Wall Street Journal front-page article about Maker’s Mark, and craft bourbon generally, that garnered national attention for the bourbon, the red dripping wax seal, and the family behind it.93

Despite spending four pages on this significant history, the circuit court did not discuss any of the even longer history of tequila (dating back to the sixteenth century) or Jose Antonio de Cuervo’s purchase of a blue agave farm from King Ferdinand VI of Spain in 1758 and instead wrote a mere three sentences, only to reference the name of the Cuervo brand, its initial use of a straight-edged wax seal, and its transition in 2001 to a “red dripping wax seal reminiscent of the Maker’s Mark red dripping wax seal.”94 Then the circuit court went on to affirm the injunction and the award of litigation expenses to Maker’s Mark, protecting Maker’s Mark’s exclusive use of its red dripping wax seal.95

Many other bourbon brands use wax seals today, but none use red, and all are neatly trimmed. No brand seems willing to use red wax at all or free-form tendrils of any color. That seemed to be part of the district court’s reasoning for imposing an injunction: the court recognized that its ruling “also protects Maker’s Mark from other competitors or quasi-competitors in the industry, in that it may serve to discourage them from treading too closely on the mark.”96