4

Old Crow Provides the Most Comprehensive Trade Name Case Study

Bourbon distillers have proven themselves to be a competitive bunch, and taking advantage of another’s name recognition is probably as old as commercial distilling itself. Col. E. H. Taylor Jr., George T. Stagg, James E. Pepper, Country Distillers, Maker’s Mark, and countless others have all sued to protect their trade names or trademarks. One brand rises above the rest, however, both in sheer number of lawsuits and in telling the American story: Old Crow.

The Old Crow brand is named after Dr. James Crow, the Scottish immigrant who many claim invented or perfected the sour mash method of distilling bourbon at the Old Oscar Pepper Distillery (now Woodford Reserve). From the 1830s through his death in 1855, the Old Oscar Pepper Distillery was renowned for Dr. Crow’s bourbon, which became known as “Old Crow.” Old Crow continued in production after 1855 by W. F. Mitchell (who had worked with and then succeeded Dr. Crow as distiller) and beyond. Solomon C. Herbst, the Prussian-born wholesaler who bought the Old Judge Distillery and is the origin of the John E. Fitzgerald legend, testified that Old Crow was the best and most expensive whiskey.1

Old Crow is perhaps the most celebrated historical brand, but in more recent decades it has transitioned to the bottom shelf. 2 While the stories about Dr. Crow have largely morphed into marketing legends, numerous cases from the late 1800s and early 1900s preserve the true story of the brand, shine light on the corporate appropriation of an abandoned brand name, and show that litigiousness is an old American trait.

More than a decade after Dr. Crow died, Gaines, Berry & Company was formed as a partnership by Hiram Berry, William A. Gaines, and Col. E. H. Taylor Jr. Later it was reconstituted as W. A. Gaines & Company when it added New York investors and management Sherman Paris, Marshall J. Allen, and Frank S. Stevens. They built the Hermitage Distillery in Frankfort, Kentucky, in 1868, and reportedly became the largest producer of sour mash whiskies in the world. Colonel Taylor withdrew in 1870 to pursue his own distillery ambitions, and new New York money and management continued to be added.

As might be expected, the Civil War had curtailed whiskey production dramatically. But after the end of the war production across Kentucky ramped up quickly and producers began using more sophisticated and scientific methods, such as those used by Dr. Crow before the war. The Old Crow brand had received some notoriety during the war, and Colonel Taylor and his partners saw an opportunity with the death of Oscar Pepper. Gaines, Berry & Company leased the Old Oscar Pepper Distillery and employed Dr. Crow’s apprentice, and the company immediately began branding its barrel-heads “Old Crow.” Upon the expiration of its lease, the company moved to a new distillery a few miles down Glenn’s Creek toward Frankfort, naming it the “Old Crow Distillery.”

Eleven published court opinions between 1898 and 1918 tell the story of Dr. Crow, the Old Oscar Pepper Distillery, the new Old Crow Distillery, and the ongoing efforts of Gaines, Berry & Company to protect the brand name that it had acquired. In addition to the factual historical value of these cases, they also show the fierce tenacity that today is more commonplace in brand name protection. In fact, as marketing hit its modern stride in the 1950s, Old Crow took great pride in its history of lawsuits and wore courtroom battles as a badge of pride (fig. 8).3

To set the stage, the Old Oscar Pepper Distillery is situated on Glenn’s Creek in Woodford County, Kentucky. Only a few miles downstream toward the Kentucky River and Frankfort are the famous Old Taylor Distillery and the Old Crow Distillery. This stretch of Glenn’s Creek might be one of the “sweet spots” for bourbon production, as noted by the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit in 1915: “Woodford County, Ky., is not far from Bourbon County, and is in the heart of the limestone formation, ‘blue grass’ country. This general region has always been and is the center of the distilling business for the best known Kentucky whiskies. The water from the limestone springs—whether or not it is really better than other waters for making whisky—in the early days was thought to be of unique purity and essential to the highest grade of the distilled product. Three brands, among the most advertised and so most widely known now for a generation, are made within a few miles of each other, in Woodford County, along Glenn’s creek—‘Taylor,’ ‘Pepper,’ and ‘Crow.’”4

Fig. 8. Old Crow 1954 advertisement. LIFE, September 15, 1952. Author’s collection.

The cases then describe how Dr. Crow “had a secret formula for the making of whisky” and “was employed in 1833 by Oscar Pepper, the owner and operator of a distillery, for whom he made whisky according to his formula until 1855.”5 After Dr. Crow died, his apprentice, William F. Mitchell, “who had worked with Crow and had learned his formula, took Crow’s place and continued to make whisky at the Pepper distillery” until 1865, when Oscar Pepper died.6 Gaines, Berry & Company leased the Pepper Distillery after Pepper died, until July 1869, at which time Gaines, Berry & Company moved to a new distillery about three miles away down Glenn’s Creek.7 Gaines, Berry & Company (and its successor, W. A. Gaines & Co.) employed Mitchell as its distiller both while leasing the Oscar Pepper Distillery and at its new distillery, all the while using Dr. Crow’s secret formula.8 In order to ensure the link to Dr. Crow and his secret formula, Gaines hired Mitchell’s apprentice, Van Johnson, who learned the secret formula from Mitchell, as its distiller in 1872.9 Gaines, therefore, was able to tie its use of the Old Crow formula and the Old Crow name directly back to Dr. Crow himself.

The Old Crow brand—whether distilled by Crow, Mitchell, or Johnson—was highly regarded as “a whisky of superior excellence and quality” and was “sold at a higher price than any other whisky of equal age produced in the United States.”10 Despite having first used the Old Crow name in 1867, for some unknown reason Gaines claimed in an 1882 trademark application that his company had used the name continuously only since January 1870, when it built the Old Crow Distillery.11 Then, in June 1904, Gaines tried to back-date its usage when the company filed another trademark application asserting that the Old Crow trademark “has been continuously used by the said W. A. Gaines & Company and its predecessors since the year AD 1835.”12 Gaines filed yet another trademark registration in 1909 for Old Crow—but this time specifying that the name applied only to “straight bourbon and rye whisky.”13

The lawsuits all dealt with perceived or actual efforts by others to profit from using the name Old Crow, or arguably similar names, often for rectified whiskey. Gaines initially won its lawsuits, but then, as happens so often with American stories of hubris, Gaines overreached and started losing cases, setting up a decisive final battle.

In the earliest case, in 1898, Gaines won a trademark case in New York against a brand using the name White Crow.14 Four years later Gaines won another lawsuit against a grocer that had bottled Old Crow as an authorized retailer but who then started using the Crow name for bottling other whiskey.15 This case helped refine public policy that “the public had the right to presume that the bottles on which defendant had placed the ‘Old Crow’ labels contained whisky of plaintiff’s production,” perhaps being a forebear of the Pure Food and Drug Act that would be passed two years later.16 More specifically, this bourbon lawsuit established ground rules for competition: “Rival manufacturers may lawfully compete for the patronage of the public in the quality and price of their goods, in the beauty and tastefulness of their inclosing packages, in the extent of their advertisements, and in the employment of agents; but they have no right by imitative devices to beguile the public into buying their wares under the impression they are buying those of their rivals.”17

After these important victories, however, Gaines lost cases when it made tenuous claims of trademark infringement against brands like Raven Valley and Old Jay. These bourbon lawsuits helped put important limits on trademark rights; just because Gaines had rights in Old Crow did not mean that it could stifle legitimate competition or prevent other producers from using a bird name or image.18 Raven Valley and Old Jay, although referring to birds, were not close enough to Old Crow to cause any confusion, so Gaines lost those cases.

Next, in a series of six cases spanning the period between 1904 and 1918, Gaines took aim at I. & L. M. Hellman Company, a St. Louis rectifier that used the brand name Old Crow along with other versions of the Crow name. To make the obvious trademark implications even more interesting, Hellman was a rectifier that concocted blended whiskey, thus pitting the two arch enemies against each other: a genuine straight whiskey producer against a rectifier.

Each side claimed that its own whiskey was pure and that the other side practically produced deadly poison. For its part Gaines alleged that Hellman “sold a spurious compounded liquor” and complained that Hellman was “fraudulent[ly] . . . imposing upon the public a blended whisky, impure and deleterious.”19 Hellman countered that barrel-aged whiskey “contain[ed] a large and dangerous percentage of fusel oil, a deadly poison, and a large percentage of other dangerous and deleterious impurities,” that it was “unwholesome and impure,” that Gaines failed to remove “dangerous and deleterious impurities” by a “process of rectification, blending, or vatting,” and that, therefore, Gaines was “guilty of fraud upon the public.”20

More was on the line than “just” a trademark. Despite the victories for producers of straight whiskey with the Bottled-in-Bond Act of 1897, the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, and the Taft Decision of 1909, rectifiers were still challenging straight whiskey producers. This made the lawsuits between Hellman and Gaines a true heavyweight battle, involving back-and-forth victories, numerous appeals, reversals, and efforts by Gaines to game the legal system.

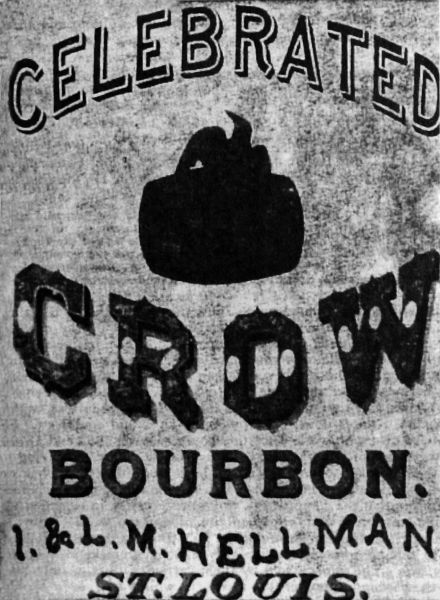

The trademark aspect of the fight seemed clear: Hellman used the brand names Old Crow, Celebrated Old Crow, J. W. Crow, and P. Crow, which would cause obvious confusion with Old Crow produced by Gaines. If Hellman’s use of the same and similar names was not enough, Hellman also used a logo depicting a crow perched on a whiskey barrel (fig. 9).21 With its litigation success against “White Crow” (in Leslie) and “Crow” (in Whyte Grocery), Gaines must have thought that a trademark lawsuit against Hellman would result in a quick, decisive victory.

The first of many court decisions would have supported any such preconceived notions. In W. A. Gaines & Co. v. Kahn Gaines won the critical first battle.22 Although the court recognized that Hellman had used versions of the Crow name since 1863 for its blended whiskey,23 the court ruled that Hellman had done so fraudulently and to deceive its customers: “I am satisfied that this was done by them for the purpose of deceiving their customers as to the character of the whisky offered by them. They marked the barrels ‘Crow,’ and also used a picture of the bird on some of the packages. It was an attempt to palm off on the trade an inferior whisky, made under the name of ‘Crow’; they well knowing at the time the superior quality of the whisky manufactured on Glenn’s Creek, in Woodford county, Ky. It was unfair competition, in that they sought to make others believe that they were selling the genuine ‘Old Crow’ whisky, when, in fact, they were offering an inferior production of their own.”24

The court also scoffed at Hellman’s argument that it should be allowed to use the varieties of J. W. Crow and P. Crow because those names are not identical to Old Crow.25 No person by those names or initials had ever worked for Hellman, so the court would not allow Hellman to so easily skirt the trademarked name owned by Gaines.26

Fig. 9. Celebrated Old Crow advertisement, I. & L. M. Hellman Co. Kahn v. W. A. Gaines & Co., 1908.

Hellman appealed, however, and the Circuit Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit sided with Hellman. In Kahn v. W. A. Gaines & Co. the court of appeals fixated on Hellman’s use of the Crow name in 1863 and an initial 1882 trademark filing by Gaines that inexplicably identified its first use of the Crow name as 1870.27 More specifically, the court of appeals was troubled by a second trademark registration filed by Gaines in June 1904—after the controversy had arisen between Gaines and Hellman but just before Gaines actually sued Hellman—in which Gaines backdated its use of the Crow name.28 In that second trademark filing Gaines swore that its Crow trademark had actually been used continuously since 1835, not 1870, as previously asserted to the Trademark and Patent Office.

Focusing on this singular detail, the court of appeals ruled that “no unprejudiced mind can read the evidence in this case without the impression that the conception of a trade-mark in the words ‘Crow,’ or ‘Old Crow,’ did not enter the minds of Gaines, Berry & Co. prior to 1870.”29 Never mind that Gaines had actually used the Old Crow name before 1870, while it leased the Old Oscar Pepper Distillery; never mind that the 1882 trademark application related only to the name of the new distillery just built by Gaines (the Old Crow Distillery); and never mind that the 1904 trademark application, for the first time, referred to the predecessors to Gaines, from which Gaines had acquired rights to the Old Crow name.

In addition to the disappointingly myopic approach taken by the court of appeals, it also serves as an example of the evolution of trademark law and inconsistencies of the courts. The court of appeals was stuck in an old frame of mind that required proof of actual confusion to support this type of trademark claim, and therefore it was important to the court that Hellman had never represented that its whiskey was made on Glenn’s Creek and never claimed to use “Kentucky corn, water, or air in the composition of their blended whisky.”30 Similarly, the court of appeals considered that no customer of Hellman had ever complained about being confused or about being deceived regarding whose whiskey was being sold.31 Unfortunately for Gaines, the Eighth Circuit was behind the times. An earlier bourbon lawsuit out of the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals, Kentucky Distilleries & Warehouse Co. v. Wathen,32 had already held that actual confusion was not required in this type of trademark claim, but it was too late for Gaines.

When the Supreme Court of the United States refused to hear an appeal of the Missouri case, Gaines did the next best thing: it sued Hellman’s Kentucky agent and distiller in Kentucky (outside of the unfriendly Eighth Circuit), the Rock Spring Distilling Company, again alleging trademark infringement. Hellman tried to impose itself as a party in the new Kentucky lawsuit, in order to argue that the issue had already been decided in Missouri, but the court rejected that effort.33

Gaines also filed a new trademark application in July 1909 (after losing in the Eighth Circuit), this time limiting its use of the Old Crow name to “Straight Bourbon and Rye Whisky.”34 Substantively, though, the Kentucky court ultimately ruled that the trademark issue had been decided by the Eighth Circuit court of appeals and the slightly revised trademark application could not be used to override the Eighth Circuit’s decision.35 The court also found it “altogether incorrect” for Gaines to have asserted, in its 1909 trademark application, that it had used the Old Crow name since 1835 because the actual year of first use was 1867.36 Similarly, the court ruled that it was “altogether incorrect” for Gaines to have asserted that no other similar trademark had been used by anyone else, when Gaines—at the very least because of the Missouri lawsuit—knew that Hellman had been using the Crow name since 1863.37 Therefore, the court dismissed the new Kentucky lawsuit.

Still not deterred, Gaines appealed to the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals, and this time Gaines won.38 The Sixth Circuit held that the new trademark registration applied only to “straight” bourbon and rye whiskey, and therefore it was proper and enforceable by Gaines.39 The court also ruled that there was no conflict with the 1908 ruling of the Eighth Circuit because that court did not award any affirmative trademark rights to Hellman, instead ruling simply that Hellman had a valid defense to the claims of infringement by Gaines.40

The Sixth Circuit was clearly troubled by the deceptive use by Hellman of the names J. W. Crow and P. Crow because, by 1863, the real Dr. Crow “Old Crow” had been produced since 1835 and was “considerably known on the market.”41 Either the initials meant nothing, posed the Sixth Circuit, or they were intended to deceive: “Witnesses for the defense frankly stated that in those years it was nothing unusual for jobbers or blenders of whisky to use well-known brands belonging to others, and that, if the initial of a proper name was changed, this was thought sufficient in morals to remove any objection to the appropriation. This may be the genesis of the otherwise unexplained use of ‘P.’ and ‘J. W.’”42

The deception by Hellman, and the new limited use of the Old Crow name by Gaines to apply only to straight bourbon and rye whiskey, satisfied the Sixth Circuit that Rock Spring (and therefore Hellman) should be prevented from using the Crow name for any straight whiskies.43 This was not the last chapter, however, because the Supreme Court of the United States decided to hear an appeal of this Sixth Circuit decision.

In Rock Spring Distilling Co. v. W. A. Gaines & Co. Gaines finally lost the Hellman lawsuit.44 Without much explanation, the United States Supreme Court ruled that separate trademarks for “straight” whiskey and “blended” whiskey could not be maintained and that Hellman—not Gaines—owned the trademark rights to the Crow name.45 In a twist of fate, however, this inauspicious end for Gaines would have spelled disaster but for Prohibition. The Supreme Court’s decision was issued on March 18, 1918, exactly three months after the Eighteenth Amendment was proposed by the Senate.46 Not even a year later, on January 16, 1919, the thirty-sixth state approved the Eighteenth Amendment, thus ratifying it, and the Volstead Act was then passed in October 1919.47 Prohibition put Hellman out of business when Gaines could not, which allowed Old Crow to survive through Gaines, as aging stock and brand rights were acquired by the American Medicinal Spirits Company.

Since those pre-Prohibition days, Old Crow has been relatively silent in litigation until recently, when its current owner sought to make the brand edgy and relevant. This recent litigation also highlights another American tradition: self-regulation to avoid expanded governmental regulation. Today brands are constrained by agreement under the advertising rules of the national trade association the Distilled Spirits Council. In addition to advocacy on legislative, regulatory, and public affairs issues, DISCUS and its members have agreed to a Code of Responsible Practices for Beverage Alcohol Advertising and Marketing.

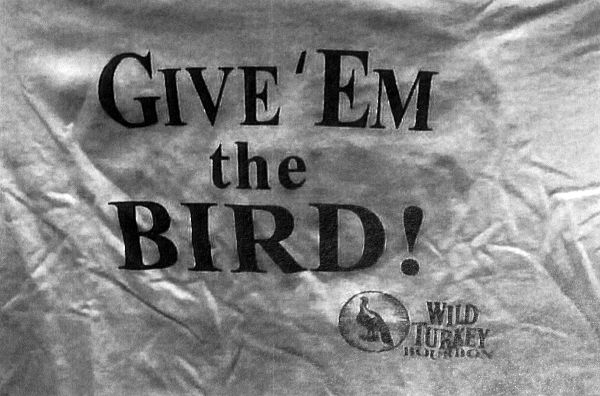

This DISCUS Code found its way into a trademark dispute between Wild Turkey (at the time using the corporate name of Rare Breed Distilling LLC) and Jim Beam (now Beam Suntory), in a case called Rare Breed Distilling LLC v. Jim Beam Brands Co.,48 in order to stop Beam from using the slogan “Give ’em the Bird” for its Old Crow brand. Wild Turkey had used the registered mark “The Bird Is the Word” since the 1970s, and “the Bird” was commonly used to identify Wild Turkey bourbon.49 Wild Turkey claimed that the public had adopted the Bird as a nickname for Wild Turkey bourbon, which gave Wild Turkey trademark rights, just like Volkswagen has rights to “the Bug” even though the official name of its iconic car is the Beetle.50 Wild Turkey used a variety of slogans in the mid-2000s, such as “The only time to give a biker the Bird,” “Give them the Bird,” “Give ’em the Bird,” and “Shoot the Bird.”51 Wild Turkey also submitted exhibits to show the prior use of “Give them the bird” and “Give ’em the Bird” (figs. 10 and 11).52

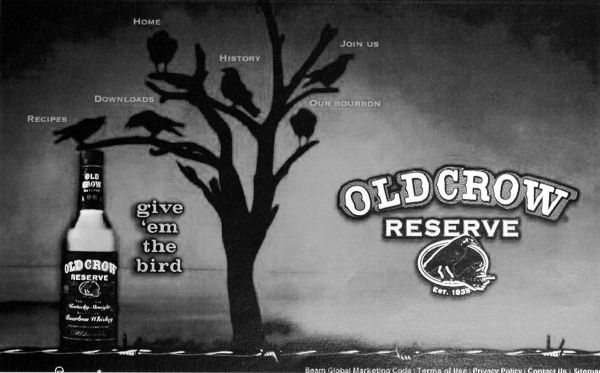

Of course, as the original iconic brand, Old Crow has a substantially longer history of association with a bird and bird imagery, so in March 2010 Beam applied to register the trademark “Give ’em the Bird.”53 Beam then rolled out a new, edgy branding campaign for Old Crow Reserve using this slogan (fig. 12).54 The press release from Beam’s marketing firm explained that Beam wanted to showcase the rich heritage of Old Crow along with “a touch of outlaw spirit” in the “rough and tumble market for bourbon whiskey.”55 In October 2010 Wild Turkey learned about the planned “outlaw spirit” campaign for Old Crow, so it sent a demand letter to Beam trying to protect its own marketing strategy, but Beam held firm on its Old Crow marketing plans.56

Fig. 10. Wild Turkey “Give Them the Bird” advertisement (2006). Rare Breed Distilling LLC v. Jim Beam Brands Co., 2011.

In the meantime Wild Turkey was in the midst of launching its own marketing campaign based on the “Give ’em the Bird” slogan, complete with Jimmy and Eddie Russell proudly extending their middle fingers for photo opportunities. As neither company backed off, in May 2011 Wild Turkey sued Beam in federal court in Louisville.57 Beam countersued in June 2011, asking the court to immediately stop Wild Turkey from infringing on Beam’s trademark because the “Give ’em the Bird” mark had just been granted registration by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office on June 7, 2011.58

Fig. 11. Wild Turkey “Give ’Em the Bird” advertisement (2007). Rare Breed Distilling LLC v. Jim Beam Brands Co., 2011.

When the parties arrived at court for an injunction hearing in July 2011, Beam relied on its trademark registration as the legal basis to rule in its favor.59 The parties presented arguments to the court about their legal positions and precedent, but ultimately, because the court wanted to hear evidence, not just legal arguments, the parties scheduled another hearing for August 10, 2011.60 Five days before the hearing, Wild Turkey filed an extensive brief supporting its position and also attached a survey that found that 24 percent of the participants recognized the Bird as a Wild Turkey name, whereas only 0.5 percent thought that it was associated with Old Crow.61

Before the hearing was conducted, however, the parties agreed to dismiss all of their respective claims.62 This agreement was probably not so much about either side conceding but, instead, the result of a ruling by DISCUS that the “Give ’em the Bird” campaign violated the Code of Responsible Practices applicable to advertising because its implicit vulgarity did not “reflect generally accepted contemporary standards of good taste” and because advertising “should not contain any lewd or indecent images or language.”63 So, the “Give ’em the Bird” campaign was abandoned by both sides, and the trademark issue was never ruled upon.

Fig. 12. Old Crow Reserve “Give ’Em the Bird” home page. Rare Breed Distilling LLC v. Jim Beam Brands Co., 2011.

This likely is not the final chapter for the once-famous Old Crow brand. Today the distilling equipment at the Old Crow Distillery (still owned by Beam Suntory) on Glenn’s Creek sits idle, while the massive warehouses provide much-needed space for aging Beam Suntory’s largest supply of bourbon in the world. And Old Crow continues to hold its spot at the bottom of Beam Suntory’s lineup, while the company focuses on its core brands like Jim Beam (the world’s best-selling bourbon), Booker’s, and Knob Creek. If bourbon’s history of resurgence provides any guidance, however, there is always a chance for rebirth. Especially in today’s climate of sourced bourbon that lacks real history, Old Crow could reclaim its title as the most famous bourbon in the world.