7

Bourbon Leads the Nation to Consumer Protection

Long before the consumer protection craze that caused obviously hot coffee to now be labeled “HOT,” toasters to be labeled to remind us not to use them in the tub, and labels for irons to warn us to not iron clothes while wearing them, product warnings were rare or even nonexistent. Early manufacturers often made false claims about their product attributes or contents. Essentially, there was no legal accountability for making false claims about a product and no protection to assure consumers that they received safe, genuine products. Whiskey was no exception, but it was Kentucky bourbon that led the way to consumer protection. Ultimately, consumers were protected from bad whiskey before they were protected from tainted food, dangerous products, and misleading advertising.

Kentucky bourbon may be less well-known for advancing other noble causes, such as environmental protection and workplace safety, but it influenced the development of those laws too. Environmental protection evolved into a necessary consideration for bourbon producers because the process of converting grain into distilled spirits requires a tremendous amount of grain and, therefore, creates a significant volume of “slop”—the material remaining after fermented mash has been distilled—as a by-product. Although most of the starch is removed from the grains, practically all of the protein, fat, and fiber remain in the slop. Slop from a traditional bourbon mash bill will have a higher fat content because of the corn; hence, slop from early Kentucky distillers became recognized as a valuable source of livestock feed.

However, as America and distilleries continued to grow together, and as the pace of distillation increased with larger stills and the introduction of column stills, the production of slop outstripped the immediate needs of the distiller and sometimes of the local community. Slop was often piped into waterways or sewers, or retention ponds overflowed into waterways, polluting rivers, killing fish, and creating an awful stench. This put bourbon on the front line of conservation and preservation efforts in the early 1900s.

As early as 1904, in addressing slop from the Peacock Distillery in Bourbon County that polluted Stoner Creek, the Court of Appeals of Kentucky ruled that “every person must use his own property and conduct his business with regard to certain rights of his neighbors.”1 Theories of land use rights in the United States had previously stressed the right of landowners to use their land and resources however they saw fit; Peacock Distillery Co. v. Commonwealth shows the emerging trend that balanced individual rights with the common good.

Kentucky Peerless Distilling Company, which was recently reborn in Louisville, gave its original home of Henderson, Kentucky, its share of water problems in the early 1900s. As explained in a trio of cases,2 Kentucky Peerless and its owner, Henry Kraver, were accused of polluting Canoe Creek with distillery slop so severely that “the waters of the creek were thereby made so impure as to render them unfit for use as stock water, cause them to emit foul odors, and so poison the atmosphere surrounding the creek as to endanger the lives of each of the [plaintiffs], his family and stock, make their houses at times uninhabitable, and depreciate the value and use of the real estate along and contiguous to the stream on which each resides.”3 Similar lawsuits were brought against the Eminence Distilling Company in Henry County, where a boy’s death was blamed on falling into and accidentally swallowing water from Fox Run Creek, the Commonwealth Distillery in Fayette County, and the Walsh Distillery in Bourbon County.4

In addition to environmental concerns, due to their unsafe working conditions, bourbon distilleries also helped the nation recognize a need for workplace safety reform. While mines, railroads, and textile factories rightfully take their place in history as some of the most dangerous places to work, whiskey was not necessarily produced at the bucolic distilleries projected today by many brands and marketers. Distilleries and warehouses were dangerous places, with plenty of opportunities to fall down warehouse shafts, to be crushed by milling equipment, or to be burned in explosions or scalded by boiling hot liquid. Making matters even more dangerous, the distilleries were factories, but they combined the risks of emerging industrial farms and milling operations with the mechanization of “modern” industry. There were plenty of ways to die in these old distilleries.

Lawsuits from the late 1800s and early 1900s paint a vivid picture of distillery working conditions as they describe the inner workings of distilleries and warehouses and then how gruesome accidents occurred. In Trumbo’s Adm’x v. W. A. Gaines & Co., for example, a worker stepped through an uncovered hole in a dark warehouse elevator platform at the Old Crow Distillery, where his leg was caught in a thirty-five-inch flywheel and “ground in pieces.”5 The court described in detail the elevator shaft and machinery, how the accident happened, and how “after his injury Trumbo was given large quantities of whisky to drink in order to enable him to endure the pain he was suffering until medical assistance was obtained.”6 The worker soon died from his injuries, but his estate recovered nothing in court.

The Old Crow Distillery’s “dry house” was also described in detail because of another injury case, W. A. Gaines & Co. v. Johnson.7 The court described the sixty-foot-long shafting system with pulleys, sprocket wheels, run belts, and chains and how Johnson was caught up in a twelve-inch sprocket wheel that was spinning at one hundred revolutions per minute and was permanently injured.8 Although the worker won at trial, the court of appeals reversed the decision, telling the trial court to revisit the possibility that Johnson had been negligent himself.9

Poorly lit working conditions seem to be a recurrent factor in these early cases. The Pogue Distillery was one of the most popular and prolific distilleries of the time, and it needed to run an overnight shift to keep up with demand. The worker in Dryden v. H. E. Pogue Distillery Co. was assigned to the milling room, where “he was put to work by Will Hays [the miller] in raking the meal from what he calls the ‘shaker’ into rollers, by which it was ground, and which were about five inches below the shaker.”10 The problem was that it was 3:30 a.m. and there were no lights, and Dryden was unfamiliar with this particular job or the danger of the rollers.11 As might be expected, Dryden’s hand was caught and crushed by a grain roller, requiring amputation.12

Crushing injuries were just one of many ways to be maimed and scarred while working at a distillery. The J. & J. M. Saffell Distillery operated just south of Frankfort on the Kentucky River. When the distillery superintendent asked a thirteen-year-old boy, who had come to the distillery with friends to pick up loads of slop, to help wash out a vat filled with scalding hot slop, catastrophe could have been expected. He asked the boy to climb to the top of the vat to help guide a hose, and the boy fell in, suffering third-degree burns to his waist and “rendering him a cripple for life.”13

A worker at the Nelson Distillery Company who was normally assigned to the meal room had been assigned to the mash room on his fateful day. The court in Kentucky Distilleries & Warehouse Co. v. Schreiber described the size of the mash room and the mash tub and the precise location and operation of the pipes leading into the mash tub.14 Specifically, the cold water pipe was turned on by reaching over the mash tub, but the scalding hot water was turned on out of sight in an adjoining room. Schreiber was instructed to open the cold water valve, but as he leaned in to do so, another employee opened the hot water valve, which soaked Schreiber’s head, neck, body, and arms, causing severe burns.15

Explosions and fires were not uncommon either. In Kentucky Distilleries & Warehouse Co. v. Johnson the distillery was operating its bottling line overnight.16 The foreman called an employee back in after the end of the workday, at 8:00 p.m., to dump ten barrels of bourbon because the holding tank was empty, so that “the girls” on the bottling line would have work for the night.17 Noting that federal regulations prohibited the distillery from blending bourbon from different seasons (meaning that the whiskey was bottled in bond), the court explained that the foreman had instructed Johnson to look into the holding tank to ensure that it was empty.18

The holding tank was covered with a lid, and the foreman knew that alcohol vapors would collect in the tank and could be ignited by a flame.19 Johnson, however, had never checked the tank before and did not know about the dangers of using an open flame near the tank.20 Still, the foreman told Johnson to use his own lantern—which was “an ordinary railroad lantern” with an open flame—when checking the tank.21 Johnson testified that when he opened the lid and leaned in with his lantern, “it just caught me afire. When the lantern exploded it just flashed out, popped about like a cannon. . . . I was burned on my face and head; burned my hair all off; and both hands burned, too, there nearly to the elbow.”22 The medical evidence was gruesome. Johnson’s burns were so bad that his bones were exposed; the membranes of his nose, mouth, and throat were burned; and his hands were permanently deformed.23

Other distillery workers suffered horrific injuries or died in countless ways, such as falling into holes while walking through dark distilleries, for example, when mash tubs were removed for maintenance but no temporary guardrails had been installed; suffering broken bones or “mashed” legs when barrels of whiskey fell down an elevator shaft; getting thrown from roofs while raising equipment on block and tackle; falling down elevator shafts along with full barrels because the ropes used were “old and rotten, and the pulleys out of order”; getting hands caught in grain mills, necessitating amputation; falling down open aisles in warehouses because upper levels often did not have walkways, instead requiring workers to climb on the rick structure itself; being violently dragged up a corn conveyor; and falling down elevator shafts, in the dark, where there were no guardrails around the opening.24

While pollution and gruesome injuries helped build a demand for environmental protection and workplace safety reform, consumer protection was bourbon’s crowning achievement and an area in which Kentucky straight bourbon whiskey led the charge. In fact, Col. E. H. Taylor Jr. was the driving force behind the nation’s first consumer protection law. Whereas Colonel Taylor, members of the Wathen family, and many other Kentucky distillers were making true straight bourbon whiskey, rectifiers, blenders, and charlatans were blending neutral spirits (sometimes including bourbon or other whiskey) with additives and passing off these much cheaper spirits as bourbon.

Blenders and rectifiers could make their product in hours or days, compared to the years of aging required for bourbon. Lower distillation costs, zero barreling and aging costs, and the speed of getting their product to the market gave blenders and rectifiers a tremendous competitive advantage. To make matters worse, no law prevented them from calling their adulterated spirits “bourbon,” “whisky,” or even “pure.”

The real bourbon distillers needed to protect their brands and profits, and the politically acceptable way to accomplish this was to sell it as a consumer protection law. Not all blenders and rectifiers were bad, but there were reports of hazardous additives, and consumers had a right to know what was in their bottles. So, Colonel Taylor—who was himself an extremely well-connected politician—helped push through the Bottled-in-Bond Act of 1897,25 with the help of then U.S. secretary of the Treasury, John G. Carlisle (a former U.S. congressman and senator from northern Kentucky).

The Bottled-in-Bond Act of 1897 was designed to protect the public, to give assurances about the actual spirits contained in a bottle and to identify the actual distiller of the spirits. Among other requirements the act mandated that any spirit labeled as “bottled in bond” follow these rules:

- It must be “produced at the same distillery by the same distiller”;

- Mingling of different products, or even “the same products of different distilling seasons,” is prohibited;

- The addition or subtraction of any substance or material, or alteration of the “original condition or character of the product,” is prohibited;

- It must be aged in a federally bonded warehouse under federal governmental supervision for at least four years; and

- Producers must affix an engraved tax stamp over the bottle closure and must label all cases, both of which identifying “the proof of the spirits, the registered distillery number, the State and district in which the distillery is located, the real name of the actual bona fide distiller, the year and distilling season, whether spring or fall, of original inspection or entry into bond, and the date of bottling.”26

The bottled in bond restrictions have been loosened since 1897, but it took over eighty years. In the de-regulation climate of the 1980s, bottled in bond no longer required a tax stamp with the season and year made and bottled, so now brands no longer have to disclose the age of their product. The current restrictions are found in the federal regulations, requiring the contents to be a single type of spirit, produced in the same distilling season by the same distiller at the same distillery, aged at least four years, unaltered (except that filtration and proofing is permitted), proofed with pure water to exactly 100 proof, and labeled with the registered distillery number and either with the real name of the distillery or a trade name.27

Nevertheless, especially in 1897, this law was groundbreaking. As described in W. A. Gaines & Co. v. Turner-Looker Co., a key element of the act was that it prohibited “any mingling of different products,” which of course was to differentiate bottled in bond whiskey from rectified whiskey.28 The House of Representatives draft committee summarized the purpose of the act as providing assurances of purity to consumers: “The obvious purpose of the measure is to allow the distilling of spirits under such circumstances and supervision as will give assurance to all purchasers of the purity of the article purchased, and the machinery devised for accomplishing this makes it apparent that this object will certainly be accomplished.”29 Accordingly, courts allowed bottled in bond whiskey to be labeled and advertised as “pure.”30

As an added benefit to bourbon distillers, they retained their tax break. “Bonded” whiskey and “bonded warehouses” were nothing new in 1897 because they already existed for purposes of taxation. As explained in Wathen v. Kentucky Distilleries & Warehouse Co., the process addressed storage, shrinkage, and taxation: “When whisky is manufactured, it is at once placed in barrels, and these barrels immediately put in a United States government bonded warehouse, and the government tax on each barrel is computed according to the number of gallons of whisky put into the barrel less the allowance for shrinkage. When the bonded period expires—that is, the period fixed when the whisky must be removed from the warehouse by the owner—he must pay the government tax.”31 The deferment of taxes and the avoidance of taxes for a pre-set, assumed amount of shrinkage were both important incentives for distillers of straight whiskey.

The bonding period and the amount of allowable shrinkage were adjusted over time. In 1880 the bonding period was three years, with 7.5 gallons per barrel allowed for shrinkage.32 However, distillers bore the risk of leaky barrels or that shrinkage would exceed the tax-free level: “If a barrel of whisky contained when it was put in the warehouse 50 gallons, the owner at the end of three years would only be required to pay tax on 42½ gallons, but he must pay on this quantity, although the barrel might have in it only 30 gallons.”33

In 1894 the bonding period was extended to a maximum of eight years, and allowable shrinkage was increased to 9 gallons over the first four years only.34 Understandably, this effectively created a four-year bonding period, which remained the standard in 1897, when the Bottled-in-Bond Act was passed. In 1899 the amount of allowable shrinkage was increased again, this time to 13.5 gallons for the first seven years of the eight-year bonding period.35 It was a constant challenge for distillers to monitor their aging whiskey and pay only the tax required.

Consumers, of course, benefited tremendously from the act if they were willing and able to purchase bourbon that was bottled in bond. Consumers who purchased bottled in bond whiskey received the government’s solemn guarantee that the contents of the bottle was exactly as stated on the label and that there were no additives. As explained by the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals in W.A. Gaines & Co. v. Turner-Looker Co., this was not necessarily a guarantee of quality, but it was a guarantee of the authenticity of the contents.36 Additionally, bottled in bond producers were allowed to state on labels that the law meant their bourbon’s “purity” was guaranteed by the United States government, even though “guarantee” is not 100 percent accurate, thus giving Colonel Taylor and other distillers even more marketing leverage.37

Despite the assurances of purity provided by the Bottled-in-Bond Act of 1897, however, price still seemed to drive consumer choice. Even courts noted that straight whiskey was better, but it was also more expensive, which might explain why 50 to 75 percent of the whiskey sold in the United States was blended whiskey.38 Price continued to rule the day.

In addition to the lower price of blended whiskey driving demand, the Bottled-in-Bond Act of 1897 did nothing to curb production of imitation whiskey, to prevent producers from deceiving consumers with false labels claiming spirits to be “whisky” or “bourbon,” or to prevent con artists from fabricating fanciful health claims to promote their brands. Once again, whiskey provided both the villain (the Duffy Malt Whiskey Co.) and the hero (the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906).

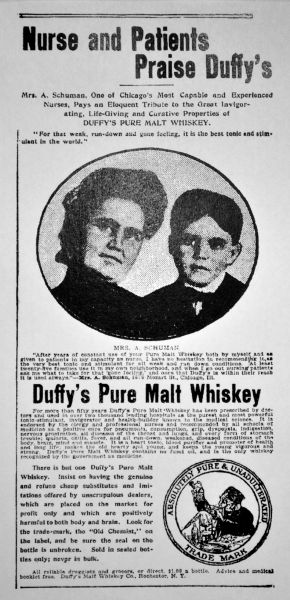

Walter Duffy took over his family’s distillery, the Rochester Distilling Company, in the 1870s. By the early 1880s Duffy was advertising his Duffy’s Malt Whiskey not only as a tonic that “Makes the Weak Strong” but also as a cure for all sorts of diseases. Consumption, influenza, bronchitis, indigestion, and practically old age itself were claimed to be no match for Duffy’s Malt Whiskey. According to false advertising, Duffy’s was endorsed by clergymen, doctors, and nurses alike. Duffy bought some of those testimonials, and he falsified others. When one nurse learned that she was featured in one testimonial, she sued for libel (fig. 18).39

Fig. 18. Duffy’s Malt Whiskey false advertisement. Peck v. Tribune Co., 1907.

Based upon these false claims, the company grew strong enough to withstand and prosper during the Panic of 1893, and by 1900 Duffy had formed the New York and Kentucky Company, which acquired the George T. Stagg Company and the Kentucky River Distillery (previously, and better, known as the O.F.C. and Carlisle Distilleries) in Frankfort, Kentucky.

While owning these Frankfort distilleries, Duffy continued to market his Duffy’s Malt Whiskey for its claimed medicinal benefits. Through the early 1900s the challenge to Duffy’s false advertising was building. Samuel Hopkins Adams wrote an exposé of so-called patent medicines—elixirs sold as medical cures but without any actual curative benefit—in 1905 entitled “The Great American Fraud” in Collier’s Weekly.40

While Adams stated that it was “impossible” for him to name all of the patent medicine frauds and that he could “touch on only a few,” Duffy’s Malt Whiskey was egregious enough that he identified it by name: “Duffy’s Malt Whiskey is a fraud, for it pretends to be a medicine and to cure all kinds of lung and throat diseases.”41 Adams acknowledged that “from its very name one would naturally absolve Duffy’s Malt Whiskey from fraudulent pretense” because at the time the word malt conveyed medicinal qualities, so he was sure to reference a ruling by the Supreme Court of New York that Duffy’s Malt Whiskey was not a medicine.42

A New York court had been considering whether or not Duffy’s was a medicine or a whiskey due to certain tax issues, and in Cullinan ex rel. New York v. Paxson, it heard expert testimony on that issue.43 Experts noted the alcoholic content of Duffy’s and testified that a “search was made for added medicinal ingredients with negative results.” Instead, they concluded that Duffy’s “is simply sweetened whiskey.” Accordingly, the court declared that Duffy’s Malt Whiskey was a liquor, not a medicine.44

Adams also refuted some of Duffy’s ringing endorsements. Adams uncovered that one of the featured clergymen simply ran a “Get-Married Quick Matrimonial Bureau” and was paid ten dollars for his picture; another was a “Deputy Internal Revenue Collector” and racehorse owner, whose actual photograph was not used in the advertisement; and the third clergyman was forced to resign by his congregation after they learned of his endorsement. Adams also discovered that Duffy’s employees tricked some physicians into providing testimonials—for example, by misrepresenting that they would not be used in advertising. Ultimately, “The Great American Fraud” helped lead to the passage of the Pure Food and Drug Act in 1906. The act provides that “any article of food, drug, or liquor that is adulterated or misbranded” and transported between the states is illegal and subject to confiscation.45 The act specifically—and finally—addressed false and misleading statements of any kind on labels and spelled eventual doom for Duffy’s.46

Other “whisky” producers in the 1800s and early 1900s simply tried to pass their brands as genuine whiskey (without making fanciful health claims), when, in fact, they were selling imitation or “rectified” whiskey. In addition to his instrumental role in passage of the Bottled-in-Bond Act of 1897, Col. E. H. Taylor Jr. also focused his substantial efforts against these blenders, including a prominent Louisville, Kentucky, businessman, another colonel with the same surname: Col. Marion E. Taylor.

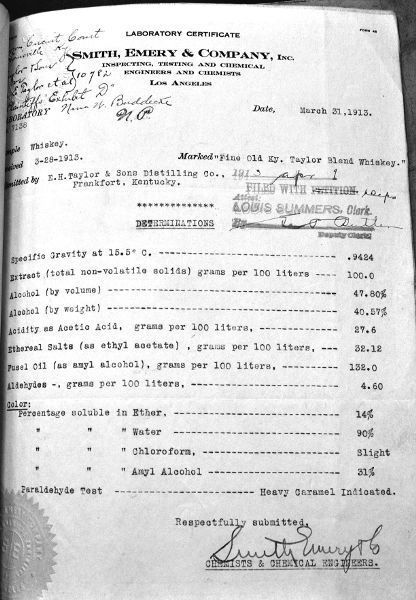

E. H. Taylor sued Marion Taylor in Louisville alleging that Marion was misrepresenting his blended whiskey as “straight” bourbon whiskey and that Marion was trying to defraud the public by using a brand name similar to that of E. H. Taylor’s bourbon.47 Marion Taylor formed Wright & Taylor with John J. Wright in 1886, and together they sold Kentucky Taylor, Pride of Louisville, and Cain Spring Whiskey; by 1892 Wright & Taylor had added Fine Old Kentucky Taylor, which became the company’s most popular brand. In 1896 Marion Taylor bought and expanded the Old Charter Distillery and brand, which allowed him to distill and sell Old Charter straight bourbon, but he also continued to sell his very popular blended Fine Old Kentucky Taylor brand.48 The purchase also allowed Marion to call himself a “distiller,” which infuriated E. H. Taylor.49 E. H. Taylor even had Marion’s Fine Old Kentucky Taylor tested by a laboratory to prove that it was rectified; the results proved E. H. Taylor was right (fig. 19).50

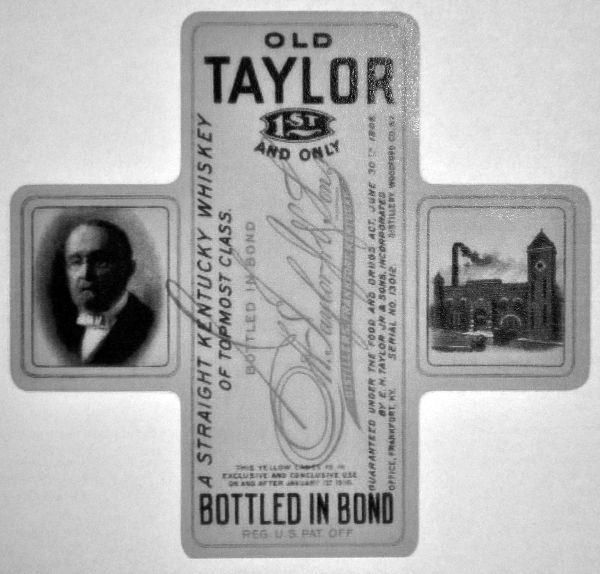

E. H. Taylor’s straight bourbon was the similarly named “Old Taylor.”51 He complained that Marion was creating confusion between the “inferior” blended whiskey and the “superior” (and much more expensive) straight bourbon whiskey and sought an injunction against Marion plus $100,000 in damages.52 After years of fighting in court and dozens of depositions from Boston to San Francisco, the Jefferson County circuit court dismissed E. H. Taylor’s claims, finding that Marion Taylor was not infringing on any trademarks nor unfairly competing.53

Fig. 19. Smith, Emery & Co., laboratory analysis of Fine Old Kentucky Taylor, March 31, 1913. E. H. Taylor, Jr. & Sons Co. v. Marion E. Taylor, 1897. Kentucky State Archives.

E. H. Taylor appealed to the Kentucky Court of Appeals, and the court ruled partially in his favor by granting an injunction that required Marion Taylor to specify in advertising that Old Kentucky Taylor was a blended whiskey.54 However, Marion Taylor did not have to pay any damages, and he was still allowed to use his brand name.55

While the court’s ultimate ruling might seem like only a slap on the wrist, the court was more critical of Marion Taylor in explaining the basis for its ruling. First, the court noted the difference between blended whiskey and straight bourbon: “Rectified or blended whisky is known to the trade as ‘single-stamp whisky,’ while bonded whisky is known as ‘double-stamp goods.’ The proof shows that the rectifiers or blenders take a barrel of whisky, and draw off a large part of it, filling it up with water, and then adding spirits or other chemicals to make it proof, and give it age, bead, etc. The proof also shows that from 50 to 75 percent of the whisky sold in the United States now is blended whisky, and that a large part of the trade prefer it to the straight goods. It is a cheaper article, and there is therefore a temptation to simulate the more expensive whisky.”56

To begin its analysis, the court compared the labels and advertisements used by E. H. Taylor and Marion Taylor (figs. 20 and 21). Additionally, Marion Taylor also used a phrase in its print advertisement that touted the slogan “Drink only the Purest Whisky” (fig. 22).57 After establishing this distinction and comparing the advertisements used by E. H. Taylor and Marion Taylor, the court concluded that consumers who were unfamiliar with the whiskey trade would think that Marion’s Old Kentucky Taylor was a straight whiskey.58 The court further concluded that Marion Taylor had intentionally misled consumers through his advertising by trying to pass off his blended product as E. H. Taylor’s straight bourbon, “which had attained a very high reputation as a pure Kentucky distilled whisky.”59

Marion Taylor’s blended whiskey “was a cheaper article, and could be sold at prices at which [E. H. Taylor] could not afford to sell his whisky,” and because his deceptive advertising could confuse consumers, the court ruled that Marion Taylor had to be truthful in his advertising: “[Marion Taylor] may properly sell his brand of ‘Old Kentucky Taylor,’ provided he so frames his advertisements as to show that it is a blended whisky, but he cannot be allowed to impose upon the public a cheaper article, and thus deprive [E. H. Taylor] of the fruits of its energy and expenditures by selling his blended whisky under labels or advertisements which conceal the true character of the article, for this would destroy the value of the [E. H. Taylor’s] trade.”60

Fig. 20. Old Taylor label. E. H. Taylor, Jr. & Sons Co. v. Marion E. Taylor, 1905.

In compliance with the court’s ruling, Marion Taylor made clear that his Fine Old Kentucky Taylor was a blended whiskey and distinguished it from his Old Charter brand, which was a straight whiskey. E. H. Taylor continued to pursue Marion Taylor in court, however, including trademark registration litigation in Washington DC. In re Wright involved essentially the same dispute, but more particularly, it addressed the appeal of a decision by the commissioner of patents that Wright & Taylor had not interfered with the trademark held by E. H. Taylor, Jr. & Sons.61

Fig. 21. Fine Old Kentucky Taylor label. E. H. Taylor, Jr. & Sons Co. v. Marion E. Taylor, 1905.

The Court of Appeals of the District of Columbia agreed that Wright & Taylor used Kentucky Taylor and Old Taylor deceptively by advertising “pure whisky” when it should have been labeled a blend.62 Additionally, relying on the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, the court noted that Congress sought to suppress “the manufacture and sale of adulterated foods and drugs, and also to prevent their misbranding.”63 The United States attorney general weighed in on the issue too, requiring rectified whisky to be labeled as “imitation”: “The definition of ‘whisky’ as a natural spirit involves as its corollary that there can be such a thing as ‘imitation whisky.’ If the same process were followed of which we spoke in connection with artificial wine, namely, if ethyl alcohol, either pure or mixed with distilled water, were given, by the addition of harmless coloring and flavoring substances, the appearance and flavor of whisky, it is impossible to find any other name for the product, in conformity with the pure-food law, than ‘imitation whisky.’”64 The court agreed with the attorney general and noted that “blend,” “compound,” and “imitation” whiskies were all still entitled to be called “whiskies,” so long as they contained the appropriate modifier.65 Therefore, just as the Kentucky Court of Appeals held, Wright & Taylor was entitled to use the word whisky so long as blended was also used.66

Fig. 22. Wright & Taylor advertisement. E. H. Taylor, Jr. & Sons Co. v. Marion E. Taylor, 1905.

However, because Marion Taylor had been using Kentucky Taylor and Old Taylor at the same time that E. H. Taylor had been using Old Taylor, neither of them had the exclusive right to use the name Taylor, even though it could create confusion.67 The court was clearly disappointed in its own result: “While it is, perhaps, unfortunate that one honestly complying with the law is compelled to suffer at the hands of commercial sharks, there is no relief afforded in this proceeding.”68

Despite the Bottled-in-Bond Act of 1897, the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, and court enforcement to protect consumers against false labeling, rectifying remained big business, and a dispute still raged over what could properly be called “whiskey.” Ultimately, the issue rose all the way to the White House, where President William Howard Taft took the reins to define whiskey once and for all. On December 27, 1909, President Taft published what became known as the “Taft Decision,” declaring “what is whisky,” and, remarkably, the distinctions survive today.69 President Taft reached unassailable commonsense conclusions, such as that producers cannot complain about merely being required to accurately and truthfully label their spirits, whether the spirits are “Straight Bourbon” or “Straight Rye” or whether the spirits are “rectified” or a blend of “neutral spirits.”70 Similarly, whenever straight whiskey is blended with neutral spirits, President Taft declared, it must be disclosed as a blend.71 President Taft also had to confirm that whiskey is distilled only from grain and never from molasses (which, he clarified, was rum).72

President Taft summarized that through his decision “the public will be made to know exactly the kind of whisky they buy and drink”: “If they desire straight whisky, then they can secure it by purchasing what is branded ‘straight whisky.’ If they are willing to drink whisky made of neutral spirits, then they can buy it under a brand showing it; and if they are content with a blend of flavors made by the mixture of straight whisky and whisky made of neutral spirits, the brand of the blend upon the package will enable them to buy and drink that which they desire. This was the intent of the act. It injures no man’s lawful business, because it only insists upon the statement of the truth in the label.”73

Thus, through a century of growing pains, whiskey was finally defined, and consumers were protected from harmful ingredients and false claims of contents. Unfortunately, celebration among producers of straight bourbon whiskey was short-lived, as the rising temperance movement took hold and the next chapter in bourbon history wreaked havoc on the industry.