9

Bourbon Law Reins in Fake Distillers and Secret Sourcing

The proliferation of new bourbon brands over the past decade has included many brands distilled and aged by existing distilleries but sold under new, often historic (or historic-sounding) names. Of course, a truly new brand seeking to capitalize on the bourgeoning bourbon market does not have time to build a distillery, create a recipe, and age the whiskey long enough to make it palatable, let alone for the ten or more years offered by some new brands, so these “merchant bottlers” must purchase bulk whiskey from distilleries or brokers. That reality makes “sourcing” bourbon common today, and it gives bourbon enthusiasts a chance to play detective when the new brands are not being upfront. Many merchant bottlers are upfront about sourcing.

Some merchant bottlers have been distilling and releasing younger bourbon and rye whiskies, along with continuing to source the vast majority of their offerings. Other well-known brands that traditionally did not distill their own bourbon, like Diageo and Luxco, Inc., have embarked on massive construction projects in order to distill Kentucky bourbon. In 2014 Diageo broke ground on its own new distillery in Shelby County, Kentucky, the next year it began small-scale distilling at Stitzel-Weller in Louisville, and in March 2017 it opened its new distillery to much fanfare. Until early 2015 Bulleit labels claimed to be a product of the “Bulleit Distilling Company, Lawrenceburg, Kentucky” (popularly believed to have been sourced from Four Roses), whereas now the label simply reflects that Bulleit is “bottled” in Louisville, Kentucky. Similarly, Luxco broke ground in May 2016 on its distillery project in Bardstown, Kentucky—called Lux Row Distillers. Its forty-three-foot tall Vendome copper column still was installed in March 2017, and by spring 2018 it was operating at full steam. In the meantime new brands using sourced bourbon seem to be announced regularly, with some commanding premium prices despite their unknown provenance.

Sourcing is not a new practice, however. Litigation between an Ohio wholesaler and the H. E. Pogue Distillery in the early 1900s provides an example of an early sourcing contract. The court in H. E. Pogue Distillery Co. v. Paxton Bros. Co. was faced with claims by Pogue that Paxton Brothers had breached its contract to purchase a large quantity of Pogue bourbon, which Paxton had planned to label as its own.1

Paxton Brothers was a Cincinnati-based spirits wholesaler.2 By the late 1800s the company had found success with its Edgewood Whiskey brand, and there was wide recognition of its trademark rotund, tuxedo-and-fez-wearing man, known simply as the “Edgewood Man.” Pogue, of course, is one of the more significant historical names in Kentucky bourbon. After suspensions in operations during Prohibition and changes in ownership and closure after World War II, the Pogue family reclaimed the brand in 2003, relaunched with a sourced bourbon in 2004, and is now distilling again. Located in Maysville, Kentucky, near the legendary site where many say bourbon was born—the old Bourbon County, with its port on the Ohio River ready for shipping whiskey to New Orleans—the Pogue distillery was one of the top bourbon distilleries in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

The Wine and Spirit Bulletin reported in its April 1, 1906, edition that Pogue had sued Paxton Brothers for thirty thousand dollars because of the alleged breach of contract by Paxton. The district court’s 1913 opinion by Judge Andrew McConnell January Cochran (who, like the Pogues, was a Maysville native) recites that Paxton Brothers contracted to purchase 12,500 barrels of bourbon from Pogue, which Pogue was to distill and then age in its warehouse.3

These 12,500 barrels were to be labeled not with the Pogue name but, instead, as having been distilled by Paxton Brothers or possibly under its Edgewood trade name.4 The parties tried to find a way under their contract for bottling the bourbon under the Paxton or Edgewood name, which certainly would have been difficult given the tight government regulations of the time. In fact, federal law at the time would not have allowed the distillery to be operated as the H. E. Pogue Distillery and at the same time stamp and label the bottles showing another’s name.5 Recognizing this dilemma, Pogue and Paxton apparently agreed that even though Pogue was in fact going to produce the bourbon and sell it to Paxton, the Pogue distillery would be leased to its namesake, H. E. Pogue, who would operate it as “H. E. Pogue as the Paxton Bros. Company.”6

This maneuver, they believed, would allow the bourbon to be labeled as having been distilled by Paxton.7 Judge Cochran found this arrangement to be “the perpetuation of fraud on the public” by representing that Paxton “had made the whisky, which in fact [Pogue] had made.”8 Because of this “fraudulent” purpose, the court held that the contract was void, and it dismissed Pogue’s claims.9

An even earlier case of secret sourcing was ruled upon by William Howard Taft, Sixth Circuit judge from 1892 to 1900, before his single term as president (1908–12) and eventual service as United States Supreme Court chief justice (1921–30). Whiskey fans most likely know him for his “Taft Decision” in 1909, which clarified the Pure Food and Drug Act and finally answered the question “What is whisky?” by defining “straight,” “blended,” and “imitation” whiskey.10 The events described in Krauss v. Jos. R. Peebles’ Sons Co. all take place after James Pepper went bankrupt in 1877 and lost his father’s distillery in Versailles, Kentucky11—the famed Old Oscar Pepper Distillery, where Old Crow was born—to Labrot & Graham. They also take place after Pepper unsuccessfully sued Labrot & Graham.12

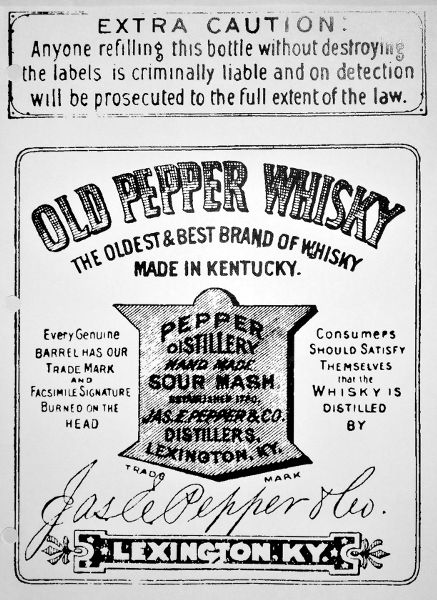

After losing his father’s distillery and losing the right to use the Old Oscar Pepper name, James Pepper built a new distillery in Lexington, Kentucky, and eventually he gained great fame. Pepper started distilling there in May 1880 and designed a new shield trademark, which he printed on gold paper for labels (fig. 23).13 As many new whiskey distillers know, starting a new distillery has high front-end expenses with a long wait before any whiskey is fit to sell. Perhaps to account for this reality, Pepper sold newly filled barrels to the Jos. R. Peebles’ Sons Company, a large Cincinnati grocer and liquor dealer, for aging and bottling, and kept other barrels in his own warehouse.14

In 1886 Pepper was ready to sell his first run of bourbon, after it had aged for six years. Peebles was also selling (and had been selling) this bourbon under the Old Pepper brand, but after Pepper got into the bottling business, he supplied the gold shield labels to Peebles and other bottlers.15 Pepper also continued bulk barrel sales to Peebles after 1886, through 1893, when Pepper decided to make Otto Krauss his sole distributor and contracted with Krauss to sell him thirty thousand cases per year, plus one thousand barrels of bourbon and five hundred barrels of rye per year.16

Fig. 23. Old Pepper Whiskey label. Krauss v. Jos. R. Peebles’ Sons Co., 1893.

Peebles still had a large supply of Old Pepper bourbon, so the company continued to bottle and sell it, using the same labeling it had always used.17 Krauss took exception and sued Peebles in the spring of 1893, asking for an injunction to prohibit Peebles from labeling its bottles as “Old Pepper,” even though Peebles was undisputedly bottling and selling Old Pepper bourbon distilled by James Pepper.

Circuit Judge Taft found some disturbing evidence in the case that might have influenced his famous decision sixteen years later. Evidence was presented showing that, at least since December 1891, James Pepper had been buying bourbon from other distilleries and blending it with his own bourbon—all the while still guaranteeing to the public that it had been distilled by him, as genuine and unadulterated Old Pepper.18

The percentages varied each month, but Judge Taft recited the exact percentage of “foreign” whiskey that Pepper had blended into his bottles of Old Pepper on a monthly basis over the course of nineteen months.19 It was often more than 50 percent foreign whiskey, spiked to 66 percent foreign whiskey in one month, and on average more than 33 percent of every bottle was foreign whiskey over that period.20 Judge Taft took Pepper and Krauss to task. He recited all of the express guarantees blanketing the Old Pepper label that it was pure and unmixed with other whiskey and that the bottle contained nothing but Old Pepper bourbon distilled at the James E. Pepper Distillery in Lexington, by James Pepper himself.21 Judge Taft ruled that this was “a false representation, and a fraud upon the purchasing public” and that “the public are entitled to a true statement as to the origin of the whisky, if any statement is made at all.”22

So, Krauss and Pepper could not stop Peebles from using the Old Pepper trademarks because Krauss and Pepper were themselves engaged in fraud, and this 1893 decision must have influenced President Taft sixteen years later, when he defined the standards for labeling whiskey. In fact, in 1909 President Taft wrote that through his decision “the public will be made to know exactly the kind of whisky they buy and drink.”23

After Repeal, sourcing was a necessity for many producers that had been squeezed out of business during Prohibition. Then, due to shortages during World War II, increased consolidation in the industry, and a move away from consumer interest in knowing the provenance of their whiskey, sourcing grew even more commonplace. In fact, the distillery in Lawrenceburg, Kentucky, now known as Wild Turkey, seems to have distilled almost exclusively for the sourced market. The owner of that distillery at the time, Robert Gould, provided plenty of lawsuits to memorialize his (sometime dubious) role in bourbon history.

The property and distillery had been operated before Prohibition by Thomas Ripy and other Ripy family members. The Kentucky Distilleries and Warehouse Company and then Prohibition put a temporary end to the Ripy’s rich whiskey history in Anderson County, but in 1933 the family formed Ripy Brothers Distillers, Inc., and began distilling again.24 On April 1, 1940, Ripy Brothers entered into a sourcing agreement with the behemoth Schenley Distillers Corporation, under which Ripy Brothers sold to Schenley its 12,897 already aging barrels, along with future production between 1940 and 1944 of another 41,000 barrels.25 Ripy Brothers became nearly an exclusive contract distiller for Schenley by also agreeing to not produce any other whiskey, except 1,000 barrels per year, so long as the word Ripy was never used.26 Schenley assigned its contract to one of its wholly owned subsidiaries, Bernheim Distilling Company.27

World War II and the resultant suspension in whiskey production by the War Production Board as well as price ceilings imposed by the Office of Price Administration (OPA) made “whiskey scarce and buyers were not difficult to find.”28 This scarcity made sourcing all the more important, and fortunes could be made or lost based on the ability to secure barrels of whiskey. Gould was an entrepreneur who saw the shortage developing and who acquired distilleries and barrels wherever he could. He acquired the Ripy Brothers Distillery and its stock, and before that he acquired other stock through the equivalent of foreclosure sales, which did not always go well. In Gould v. Hiram Walker & Sons, Inc., for example, the Pennsylvania Whiskey Distributing Company had failed and its assets had been seized by the New York State Tax Commission in 1940.29 Those assets included warehouse receipts for 1,861 barrels whiskey held by Hiram Walker & Sons, which Gould won as the highest bidder.30

Unfortunately for Gould, who may have still been a novice at the time, the barrels had existing liens and were being sold subject to those liens, as stated clearly in the notice of sale.31 Nevertheless, in April 1943 the district court ruled that Gould was a bona fide purchaser without notice of the existing liens, entitling him to the 1,861 barrels.32 The court of appeals disagreed, holding that the burden to investigate and determine the actual nature of any liens at a tax sale should be on Gould, as the purchaser.33

Before the court of appeals had issued its ruling in June 1944, however, Gould appears to have been eager to turn a profit on “his” barrels, which resulted in a claim for damages against Gould and a second appeal.34 The appellate court recognized that “war conditions caused a great imbalance in demand and supply of whiskey, production of which ceased during the war years.”35 Having secured bulk whiskey, Gould was able to have it bottled and took advantage of high prices for bottled whiskey.36 In the meantime the existing lienholders were unable to buy replacement bulk barrels in the existing market and instead were forced to purchase bottled whiskey at high prices.37 The court of appeals affirmed the award of damages, requiring Gould to pay the lienholders for the losses incurred in buying replacement bottled whiskey at the then-current even higher prices.38

Gould was undeterred, and he continued to buy bulk whiskey in foreclosure sales. In Gould v. City Bank & Trust Co. Gould bought warehouse receipts in 1950 for 489 barrels of whiskey issued by the Foust Distilling Company, which had been originally issued to the Sherwood Distilling Company in 1946, then pledged to City Bank & Trust Company in 1949, and then sold by Sherwood to United Distillers of America later that year.39 Even though Sherwood appears to have sold the same receipts twice, the bank owned a priority interest over Gould because the bank had bought them first.40

Whoever ultimately bottled the bourbon that Gould and others chased, they branded it however they pleased, without regard for inconsistencies in sources. The same is true today, with reports and rumors of sourced bourbon brands coming from Kentucky distilleries like Heaven Hill, Four Roses, Wild Turkey, and Brown-Forman. On the other hand, America has made substantial progress since President Taft stated his goal of allowing consumers to know exactly the kind of whiskey they buy and drink; there no longer is any confusion between “straight” and “blended” whiskey. Instead, the current uncertainty is driven by distillation at undisclosed locations and bottling by entities pretending to be distillers and a seemingly limitless array of assumed names. One of the largest sources for merchant bottlers today, though, is not even in Kentucky.

Lawrenceburg, Indiana, is less than one hundred miles away from Louisville, close to the Ohio River across from Kentucky, and near Cincinnati, Ohio. There Kansas-based MGP Ingredients, Inc., operates a large-scale factory distillery once owned by Seagram’s, producing neutral spirits, vodka, gin, corn whiskey, rye whiskey, and bourbon whiskey. MGP does not have any regularly released standard brands of its own and instead is one of the primary sources for bourbon and rye whiskey for many merchant bottlers. Some merchant bottlers have been completely transparent about their acquisitions from MGP, but others have not, and the American legal system helped ensure full disclosure. For example, Templeton Rye Spirits LLC, based in Templeton, Iowa, was sued in 2014 and accused of misrepresenting its whiskey as “small batch” and distilled in Iowa, when in reality it was distilled in vast quantities by MGP in Indiana.41

In addition to the alleged misrepresentations concerning the size of the batches and the source of the whiskey, Templeton was also accused of misleading consumers through heavy marketing of Prohibition era Chicago gangster nostalgia, including a misrepresentation that the recipe was a “Prohibition-Era Recipe,” when in fact it was allegedly one of MGP’s standard recipes. The parties settled in July 2015. Under the settlement Templeton agreed to establish a fund of $2.5 million to pay approved class claims and to change its label and marketing by removing the phrases small batch and Prohibition-era recipe and by disclosing Indiana as the actual state of distillation.

Assumed names might also be used to create an impression that a particular brand of bourbon is made in the backwoods of Kentucky or at least somewhere other than a large-scale factory distillery. Buffalo Trace, for example, is a large factory distillery that, while experimenting with many different mash bills, uses three primary bourbon mash bills: Mash Bill #1 is a low-rye (believed to be about 10% rye) recipe; Mash Bill #2 is a higher-rye (believed to be between 12 and 15% rye) recipe; and the third mash bill uses wheat as the secondary grain. Mash Bill #1 is used for at least six brands (with multiple sub-labels), Mash Bill #2 is used for at least five brands, and the wheated mash bill is used for at least two brands (both with multiple sub-labels). However, the only brand label that admits to being distilled at the Buffalo Trace Distillery is the Buffalo Trace brand. Other brands claim on their respective labels to be distilled at the Old Rip Van Winkle Distillery, for instance, or W. L. Weller and Sons or Blanton Distilling Company. Those places only exist on paper.

Similarly, a picturesque, small distillery in Bardstown, Kentucky, that operated only as a merchant bottler in recent decades—but which began distilling again in 2012—sells some of the most sought-after bourbon that it acquired from undisclosed distilleries, mostly under assumed names. Kentucky Bourbon Distillers, Ltd., d/b/a Willett Distillery, offers Willett Family Estate bourbon and rye whiskies and Willett Pot Still Reserve bourbon but also another six brands (some with several sub-labels), carefully claiming on their respective labels to have been distilled in Kentucky and bottled by Noah’s Mill Distilling Company, for example, or Rowan’s Creek Distillery.

Sourcing whiskey and using an assumed name is perfectly legal, of course, so long as the brand does not make a false or misleading representation of fact that is likely to confuse or deceive the general public. Consumers should be able to find the state of distillation on labels, which will not narrow down the possible sources for Kentucky bourbon but allows a solid presumption of MGP whenever the state of distillation is Indiana. And with a little effort and internet access, it is easy enough to search for assumed names in records made available by the Kentucky secretary of state’s office. Part of the fun for bourbon enthusiasts is trying to uncover the actual source of whiskies used by merchant bottlers.