The Leoganger Steinberge, seen from the Spielberghorn (Kitzbüheler Alps, Route 54)

At four o’clock on a June morning in 1967 I gazed breathless with wonder as the sun rose out of a distant valley, and flooded its glow across a sea of mountains whose snowfields and glaciers turned pink with the new day. My companions and I had spent the night with neither tent nor sleeping bag for comfort on a summit modest in altitude but generous in outlook, and greeted the dawn with smiles of delight. Then we descended as fast as we could. As we did we won a second sunrise, then another, and another, racing for pre-dawn shadows while the sun hastened to spread its goodness over all the Eastern Alps.

I was young then, leading walking groups in Austria’s mountains, and loving every moment, every trail, every summit, valley, lake and meadow starred with flowers. Loving the pure alpine air, the cleanliness of the villages, the punctuality of bus and train, the certainty of a waymarked path, the smiles of each hut warden amused by my poor attempts to speak German. Loving life.

Forty years on I no longer race to beat the sunrise. Instead, I linger, sprawl on an alm pasture and dream. A klettersteig can still set my pulse racing, and trails continue to seduce me into wonderland, but now I take my time to get there. I’ll sit for ages and listen to the birds, a stream, or the brush-strokes of the wind against a rock. But the sight of chamois or marmot thrills me even more than it did four decades ago, while a pass is as good as a summit, a mattress in a hut as welcome as any hotel bed, a night under a blanket of stars as enriching as ever.

Austria’s Alps still draw me back, and repay every visit a thousandfold.

With more than 40,000km of well-maintained, waymarked footpaths; with countless attractive villages, hospitable hotels, inns and restaurants, pristine campsites, the world’s finest chain of mountain huts, an integrated public transport system, and breathtaking scenic variety, Austria must surely count as one of Europe’s most walker-friendly countries.

It’s a country of great diversity, whose mountains range from gentle grass-covered ‘hills’ of around 2000m, to rugged limestone spires and turrets erupting from a fan of scree, or snow-draped, glacier-clad peaks whose reflections are cast in crystal-clear lakes. In their valleys some of the continent’s loveliest villages are hung about with flowers in summer. On mid-height hillsides centuries-old timber haybarns and stone-built chalets squat among the pastures; these are the alms which add an historic dimension to the landscape. Elsewhere, heavy-eaved farmhouses double as restaurants; some provide accommodation in a rustic setting, and complement the hundreds of mountain huts built in remote locations, virtually every one of which exploits a viewpoint of bewitching beauty.

The Leoganger Steinberge, seen from the Spielberghorn (Kitzbüheler Alps, Route 54)

The Eastern Alps of Austria extend from west to east in two distinct but roughly parallel chains of around 400km each, before subsiding in the wooded hills of the Wienerwald. The chain which carries the German border is known as the Mittelgebirge (the rocky Northern Limestone Alps), while its southern and higher counterpart, the Hochgebirge, is distinguished by such snow-draped and glacier-clad groups as the Silvretta, Ötztal, Stubai and Zillertal Alps. In the heart of the country Austria’s highest mountain, the elegant Grossglockner, reaches 3798m and casts its benediction over the surrounding valleys.

This is a guide to ten mountain districts stretching eastward from the Rätikon Alps on the borders of Liechtenstein and Switzerland, to the little-known Karawanken, shared with Slovenia, in the sunny province of Carinthia. Each district has its own distinctive appeal, with fine scenery, plenty of accommodation, and numerous walking opportunities. There’ll be something to suit every taste and all degrees of commitment. And you’ll no doubt be left wanting more.

In Vorarlberg, Austria’s westernmost province, the Rätikon Alps spread along the borders of Liechtenstein and Switzerland on the southwest side of the Montafon valley. These are limestone mountains, ragged and rugged, with a choice of valleys flowing from them down to the Montafon trench, from which access is most easily gained. The highest summit is that of the 2965m Schesaplana, a walker’s peak at the head of the Brandnertal, whose main resort village, Brand, is on a bus route from the railway station at Bludenz. Schruns, Tschagguns and Gargellen also make useful valley bases, but with several well-situated mountain huts built in the high country below attention-grabbing peaks, some of the best walks either start from particular huts or make tours from one hut to another.

At the 2354m Plasseggenpass limestone gives way to crystalline rock, which continues into and throughout the Silvretta Alps, and takes the Hochgebirge and the border with Switzerland further east. The Silvretta mountains have their fair share of glaciers and snowfields, and elegant peaks such as Piz Buin and the Dreiländerspitze. More huts offer accommodation for walkers and climbers in remote locations, and some of the finest walks cross cols leading from one valley to another. Access is from both the Montafon and Paznaun valleys, the two linked by the Silvretta Hochalpenstrasse which crosses the 2036m Bielerhöhe, overlooking an attractive dammed lake. The main resorts are St Gallenkirch and Gaschurn in the Montafon valley, and Galtür and Ischgl in Paznaun, while accommodation can also be found at the Bielerhöhe itself.

The 2965m summit of Schesaplana (Rätikon Alps, Route 3)

An impressive district of 3000m mountains, whose highest summit is the 3772m Wildspitze, the Ötztal Alps contain the largest number of glaciers in the Eastern Alps. Rising east and south of the Inn river, the massif spreads over the border into Italy, but from its glacial heartland, three major valley systems drain northward to the Inn: the Kaunertal, Pitztal and the valley from which it takes its name, the Ötztal, with the neighbouring Stubai Alps immediately to the east of that. The latter valley is fed by the Ventertal and, its upper tributary, the Gurglertal, famed for the winter and summer resort of Obergurgl which, at 1927m, is Tyrol’s highest parish. Other resort villages worth considering for a walking holiday are Sölden, Längenfeld, Mandarfen, Plangeross and Feichten.

This complex district, like its neighbours to east and west, has a glacial core and some very fine valleys worth exploring, most of which are easily accessible from Innsbruck. Although primarily a crystalline range, the limestone Kalkkogel, flanking the lower Stubaital, is a Dolomite lookalike across whose southern flank one of Austria’s finest hut tours picks its way towards its close. Numerous huts located at the head of tributary valleys make obvious destinations for walks, while the Stubaier Höhenweg links no less than eight of them in an understandably popular circuit. Of the many resort villages, both Längenfeld and Sölden lie in the Ötztal, Kühtai and Gries im Sellrain give access from the north, while Neustift is the best developed for exploring the mountains above the Stubaital.

East of the Brenner Pass the Zillertal Alps are known as much for their skiing potential as for their summer walking possibilities, especially around Mayrhofen, with the nearby slopes of the Tuxertal being developed with ski tows and cableways. The Zillertal itself pushes deep into the mountains, with a choice of tributaries cutting off herring-bone fashion from it. As with the Stubai Alps most, if not all, of these tributaries have mountain huts at their head from which both climbing and walking routes can be enjoyed. With a covering of either snow or ice, the massif’s highest summits capture the imagination and make a photogenic backdrop to a wonderland of walks. Of the valley bases, perhaps the best are those that lie in a line along the Zillertal: Zell am Ziller, Mayrhofen and Finkenberg.

All the previously mentioned groups spill across international borders, but the Kitzbüheler Alps lie ‘inland’ so to speak, and have no frontiers. North of the Zillertal Alps and the Venediger group, these are grass-covered mountains of modest proportions. But on them will be found some of Austria’s best routes for the walker of moderate ability and ambition. A wealth of trails strike across hillsides and over summits with long views north to the limestone ranges, south to the crystalline border mountains, or southeast to snowy giants of the Hohe Tauern. Söll, Scheffau and Ellmau lie in a glorious valley between the grassy Kitzbüheler Alps and the abrupt wall of the Wilder Kaiser. Westendorf and Brixen lie in a parallel valley to the south, with Kitzbühel, one of Austria’s premier ski resorts and the hub of the range, at its eastern end, while Saalbach and Hinterglemm lie in the Glemmtal easily accessible from the lovely ‘Lakes and Mountains’ resort of Zell am See, and offer some of the best walking of the whole district.

A small, compact group of limestone mountains of the Mittelgebirge lying north of the Kitzbüheler Alps and bordered on the west by the Inn river shortly before it flows into Germany, the Kaisergebirge is divided into two main ridges: the Zahmer, or ‘tame’ Kaiser, and the Wilder (wild) Kaiser. Between the two lie the charming valleys of the Kaisertal and Kaiserbachtal, with a linking ridge at the Stripsenjoch. The scenery is dramatic, the climbing awesome, the walking first class, with some exciting klettersteig (via ferrata) routes to consider, and several fine huts too. On the south side of the Wilder Kaiser, Söll, Scheffau, Ellmau and Going make good valley bases. St Johann in Tirol lies to the southeast, while Kufstein on the west has the Kaisertal close by.

The 3497m Schrankogel dominates the upper Sulztal (Stubai Alps, Route 21)

The extensive south face of the Dachstein (Dachsteingebirge, Route 76)

Another limestone group, this is topped by the glacier-clad Hoher Dachstein (2995m), while the outlying crest of the Gosaukamm contrasts the main block of mountains with its finely-shaped individual turrets, pinnacles and peaks such as the Bischofsmütze giving character to the whole district. The Dachstein lies southeast of Salzburg on the edge of the Salzkammergut lake region, rising above the Hallstätter See and Gosausee, with the Ramsau terrace and Enns valley to the south. Filzmoos and Ramsau are good walking centres for routes on the south side of the mountains, with Hallstatt a romantic lakeside base on the north.

This large area boasts Austria’s largest national park, its highest mountain, the Grossglockner, and the spectacular ice-covered Venediger group, the latter rising to the east of the Zillertal Alps. Several distinctive groups make up the Hohe Tauern region, the main crest of which lies south of the Salzach river valley; a great block of mountains breached by three major north-south roads, two of which have tunnels, the third being the famous Grossglockner Hochalpenstrasse. On the northern side, Badgastein and Kaprun are recommended centres, while Matrei in Osttirol and Kals am Grossglockner serve the southern valleys. Tremendous high mountain scenery and exhilarating walks make this an excellent region in which to base a holiday.

Surprisingly little-known to mountain walkers from the UK, the Karawanken is a narrow range of mountains along whose crest runs the Austro–Slovenian border south of Klagenfurt. Carinthia, the province in which the range lies, is noted for its lakes and sunshine, but the Karawanken receives little publicity. However, these sun-bleached limestone mountains of modest altitude (the highest, Hochstuhl, is only 2237m), are both dramatic and accessible, and form a scenic background to walks that lead through woodland and meadow. There are longer, more demanding routes, and much to explore from such unassuming centres as Ferlach and Bad Eisenkappel.

A cushion of moss campion (Silene acaulis) in the Zillertal Alps

A botanist with remarkable powers of observation was among a group of walkers I was leading in the Alps a few summers ago. When quizzed about the apparent anomaly of a tiny group of plants flowering in a confined site surrounded by an entirely different species, he explained ‘there are no accidents in nature; this particular plant grows in this precise location because here and here alone, conditions are perfect for it to flourish. A few centimetres away, and one or more of those essential conditions may be missing or dominated by others that deny its growth.’

The yellow Turkscap lily

(From left): the spring gentian (Gentiana verna); the fringed pink, or ragged dianthus, a lime-loving plant seen in the Karawanken; alpenroses in the Rätikon Alps.

In Austria’s Alps, as elsewhere, the range, diversity and distribution of mountain plants is enormous. Grouped by habitat, soil, climate and altitude, they are also limited by competition, by grazing or cultivation. And as we have seen, conditions that favour some plants on a given site may be absent elsewhere. Those conditions may not be obvious except to the trained botanist, but happily it is not essential to have a botanical background to enjoy the wealth of alpine flowers that add so much to a mountain walking holiday, for there will always be surprises.

Many of the best-known alpines such as gentians, anemones, soldanellas and primulas flower early in the lower valleys shortly after winter’s snow has melted – on occasion as the snow melts, with exposed islands of turf bursting into flower in the midst of a mottled snowfield. But as the snowline recedes up the hillside, these same flowers appear higher up, while those of the lower valleys may have faded or disappeared completely. By the middle of July grazing cattle will have cleared the upper pastures of most of the flowers, but above those pastures rock faces and screes that are inaccessible to domestic animals will give a sometimes startling display of alpines, often luxuriant but slow-growing cushion plants that exploit what may seem to the untrained eye to be an entirely hostile environment.

In the west, in Vorarlberg with its mix of lime and granite formations, a rich variety of flowers is there to be enjoyed, among the most common being arnica, edelweiss and saxifrage. Adjacent to the Lindauer Hut in the Rätikon Alps there’s a noted alpine garden in which visitors can identify specific plants that are likely to be in flower at any given time and place.

In neighbouring Tyrol, a province that claims to be ‘nature’s own alpine garden’, early summer meadows can seem bewitchingly colourful and fragrant. Here too both limestone and crystalline mountains provide a range of habitats and the full gamut of alpine landscapes ranging from green wooded hills to glacier-draped peaks and dolomitic fingers of rock. Each has its own specific flora. In the highest valleys of the Ötztal Alps, for example, the deep blue-violet Primula glutinosa is worth noting, as is the pink-flowered creeping azalea Loiseleuria procumbens which is known to grow up to 3000m. Also found at a similar altitude on scree or rocky ridges, is the rare Mont Cenis bellfower, Campanula cenisia, a dwarf plant with tiny slaty-blue flowers. Among other surprises is a reported sighting of a fringe of martagon lilies (Lilium martagon) near the top of a cliff face at around 2235m by the Riffelsee. This plant with its pendulous Turkscap flowers is usually confined to woods or meadows.

The Hohe Tauern rewards botanist, walker and climber in equal measure. Around Austria’s highest peak, the Grossglockner, turf dampened by snowmelt produces a mass of Primula minima, its colour ranging from blue-mauve to magenta-pink. The wonderfully fragrant Daphne striata is also here. A straggling or prostrate bush 15–20cm tall, it has clusters of reddish purple flowers with a ruff of down-pointing leaves at its best in June. Among the gentians to be seen is the common but very lovely spring gentian, Gentiana verna, as well as Gentiana nivalis, the so-called snow gentian, and the biennial Gentianella ciliata, a brilliant blue flower with fringed lobes.

In the Karawanken mountains of Carinthia which spread into Slovenia, many native plants are reminiscent of those found in the Dolomites, which would suggest that strands of dolomitic rock appear in the Carinthian limestone. Aster bellidiastrum, a tall perennial that resembles a large common daisy has taken on a rosy-pink tinge. There are purple coloured aquilegias, and the aptly-named Schneerose (Snow rose) hellebore, Helleborus niger. Cyclamen grace the pinewoods, lemon-yellow poppies bring colour to white screes and, of course, a great splash of pink or scarlet on the hillsides betrays the presence of the ubiquitous alpenrose almost everywhere.

Alpine flowers may be a colourful adornment to the mountains, but the sighting of wildlife can be a highlight of any walk. In the Austrian Alps there should be plenty of opportunities to study birds and animals in their natural environment, but since most of the mammals are notoriously shy, you’ll need to walk quietly and remain alert to be rewarded. On some of our trips we’ve studied ibex on an exposed ridge above the Braunschweiger Hut, had young marmots play round our stationary boots, watched roe deer watching us, and been impressed by the grace and speed of a small herd of chamois racing across a near-vertical scree. Each of these experiences served to enrich our day and remains imprinted on memory long after.

Ibex (Steinbock in German) must count among the most striking to observe in the wild. The male, with its large, knobbly, swept-back curving horns and stub of a beard, is the king of the mountains. It has fairly short legs and a stocky body, but its powerful muscles enable it to spring onto narrow ledges of rock with surprising ease, or race away from danger with an unexpected turn of speed. The female is smaller and less showy than the male. With a grey or coffee-coloured coat and much shorter horns, she spends most of the year away from adult males, and when sighted could be mistaken for a chamois. It is only in the autumn-to-winter mating season that males seek out the females. First, they fight for the right to mate, and then the hills echo to the sound of clashing horns. Some hut wardens spread salt near their huts to entice ibex to graze nearby, and this is often the best way to observe them.

Less stocky than the ibex, the chamois (Gemse) is distinguished by short, sickle-shaped horns and a white rump. Its thick winter coat moults during May or June, and in summer it takes on a dark reddish-brown colour with a black stripe along the spine, and a white lower jaw. Like the ibex, the chamois is well adapted to the severity of its habitat, and is more resistant to the harsh winter weather than the roe deer, with whom it shares the forests when snow covers its normal high altitude territory. It’s a graceful and extremely agile animal, but also a very shy one with a keen sense of smell and acute hearing which makes it difficult to approach undetected. When startled the chamois makes a sharp wheezing snort as warning.

In the early summer, young marmots may be seen in the alpine meadows

Of all alpine mammals the marmot is the most endearing and most often seen. These sociable furry rodents live in colonies below the snowline and can be observed in many regions covered by this book. Growing to the size of a large hare and weighing up to 10kg, the marmot spends from 5–6 months each winter in hibernation, emerging rather lean in springtime, but soon fattening up on the summer grasses. Towards late September, having accumulated a good reserve of fat during the summer, the adults prepare their nests in readiness for winter, with dried grasses scythed with their sharp teeth. The famous warning whistle is emitted from the back of the throat by an alert adult sitting up on its haunches; its main enemies being the fox and eagle.

Among other mammals that may be seen by chance in these mountains is the carnivorous stoat which sometimes attacks young birds in ground-sited nests, but favours voles or even young mountain hares. In summer its coat is a russet-fawn which changes to white in winter, and it invariably makes its nest beneath a rock or a pile of stones.

Both the dainty roe deer and more powerful red deer inhabit the wooded areas, of which Austria has so many. Having a nervous disposition and exceptional hearing, neither are easy to catch unawares. The red squirrel, on the other hand, can often be detected scampering along a forest path, or scrabbling up a tree, its almost black coat and tufted ears being recognisable features.

Coniferous woods are home to the nutcracker who, with a kre kre kre alarm call, rivals the jay as policeman of the woods. With large head, strong beak, tawny speckled breast and swooping flight, the nutcracker is adept at breaking open pine cones in order to access the fatty seeds which it hides to feed on in winter. Capercaillie and black grouse are also present in wooded valleys and the lower mountain slopes.

The alpine chough is among the most common of birds to be met on trips into the higher mountain regions. The unmistakable yellow beak and coral-red feet distinguish it from other members of the crow family, and it will often hop around popular summits and vantage points to gather crumbs left by visiting walkers and climbers.

The pastoral idyll of the summer Alps

A number of airports in Austria and neighbouring Germany have regular flights from the UK, although some of the services mentioned below are charters only. All airports listed have good onward train and/or coach connections, and most areas organise local taxi pick-up services. Readers are warned, however, that air travel information is especially vulnerable to change, so you are advised to check carefully in advance.

Zürich airport in Switzerland is linked to the main rail network with a number of daily Austria-bound trains, and provides another option worth considering – especially for destinations in western Austria, as the airport is only 120km from Bregenz.

Holidaymakers keen to reduce their carbon footprint may wish to consider rail travel. For the majority of Austria’s alpine regions, Innsbruck- or Salzburg-bound trains will take care of most needs, with easy access to regional lines that serve the rest of the country.

Travelling from London St Pancras to Paris (Gare du Nord) via Eurostar allows a speedy start to the journey, although changing trains in Paris can be time-consuming. The onward route is through France and Switzerland (Basel and Zürich), then on to Bludenz, Landeck and Innsbruck. Alternatively, consider Eurostar to Brussels, then take the Vienna-bound express through Germany, with the option of changing trains in Munich for Salzburg or Innsbruck.

Since most rail journeys to Austria will involve overnight travel, it’s a good idea to book a couchette to ensure greater comfort and the chance of an unbroken night’s sleep.

Driving to Austria from the UK is neither the fastest nor the cheapest travel option – nor is it the most relaxing. But for visitors planning to camp and walk in several different areas, it may be the most practical. Conventional car ferries operate regular services between Harwich and the Hook of Holland; and between Dover and Ostend or Calais, while the Channel Tunnel offers a quicker crossing, with peak-time journeys on Le Shuttle running every 15 minutes.

For destinations in western Austria, possibly the fastest routing is via Brussels, Köln and Stuttgart, while for Salzburg, central and eastern Austria, consider travelling via Brussels, Köln, Frankfurt and Nürnberg.

On arrival at the Austrian border drivers must purchase a vignette windscreen sticker which authorises use of the country’s autobahns. Proof of vehicle ownership (or a letter from the owner giving permission to drive the car) is necessary, as is a driving licence for British or other EU nationals. Non-EU nationals will need an International Driving Licence. A red warning triangle, first aid kit, and ‘Green Card’ third party insurance cover, are all compulsory.

Note that some of the more spectacular alpine routes are toll roads (the Silvretta and Grossglockner Hochalpenstrassen, for example), and a number of other dramatic pass roads are unsuitable for towing caravans and trailers.

Meadows adorned with ‘hairy men’ form a regular feature in Austria’s valleys

Austria has an extensive, integrated public transport system that gives especially good value for the walker. On the whole train and connecting bus schedules are dovetailed to minimise waiting times, so a local timetable obtained on arrival at your chosen base ought to be carried along with guidebook and map. Note, however, that in general services are greatly reduced on Sundays and public holidays, and that some of the more remote villages may have just one bus each day.

The Zillertalbahn between Jenbach and Mayrhofen is one of several private railways useful to walkers

The rail network operated by Austrian Federal Railways (Österreichische Bundesbahnen (ÖBB) www.oebb.at) serves the majority of towns, and their trains are clean and punctual. The Regionalzug service stops at every station and as a consequence is slow, while Eurocity international express (EC), or the Austrian Intercity express (IC) trains are the fastest. There are also several privately operated railways such as the Zillertalbahn (Jenbach to Mayrhofen) and Graz-Köflacherbahn (Graz to Köflach). Train times are clearly displayed at all stations. For departures study the yellow posters (headed Abfahrt), while the white posters give arrival times (Ankunft).

The efficient postbus service (www.postbus.at), together with the bahnbus operated by the ÖBB and departing from railway stations, visits most inhabited valleys not served by train. These are of immense importance, not only to visiting walkers but to outlying communities. Local bus timetables (Fahrpläne) are usually fixed to bus stops (Haltestelle) or displayed outside post offices. They are also often available from tourist information offices.

There should be no shortage of accommodation in any of the areas covered by this guide, for with some justification Austria prides itself on its tourist infrastructure, and almost every town and village offers a choice of hotels, pensionen, gasthöfe, gästehaus and private rooms (privatzimmer) at mostly affordable prices. Enquire at the local tourist office for their accommodation list. Some of the larger resorts also have accommodation boards fitted outside their tourist office, and many have campsites in the vicinity.

As a general rule, campsites are clean and well-managed, with immaculate washrooms and good showers. Many have laundry facilities, small shops and restaurants attached. Sites are usually open between May and September, with seasonal variations in price.

Hotels and pensionen are star-graded; one star being the most basic, leading to extravagant five-star luxury. Budget accommodation usually remains in the one- or two-star categories, with a considerable difference in price rising thereafter. But a two-star room will often have modest en-suite facilities and include a standard continental breakfast. Note that a hotel-garni provides no meals other than breakfast.

A pension is a bed-and-breakfast hotel (also known as hotel-garni). Though often fairly small and family-run, when located in towns and cities, pensionen may occupy a section of a large apartment block or other building. Most of those in mountain villages tend to be in attractive, traditional houses.

In practical terms a gasthof is a hotel in everything but name, while a gästehaus often denotes a small bed-and-breakfast hotel. A gasthaus, on the other hand, is a restaurant, although some also offer rooms, in which case look for the words ‘mit Unterkunft’.

Renting a room in a private house is a favoured holiday option. These privat zimmer can vary greatly, with facilities ranging from a basic bedroom with shared bathroom, and breakfast left on a tray outside your room, to hotel-standard accommodation. Most rooms are let on a bed-and-breakfast basis, but it is advisable to check first – tourist offices usually have details. Look for houses displaying the Zimmer frei notice.

No alpine country has a greater number or variety of mountain huts than Austria, with a network of at least 1000 hütten built in the most idyllic of locations. Of these more than half are owned and run by member groups of the Austrian and German Alpine Clubs (Österreichischer and Deutscher Alpenverein – ÖAV/DAV), the others being either privately owned or belonging to separate organisations. All are listed in what is often termed ‘the green book’ – Alpenvereinshütten Band 1: Ostalpen published by Rother, and available from the Austrian Alpine Club (see below).

The Bremer Hut, one of more than a thousand built in the Austrian Alps

Staffed from at least July to the end of September, but often with an open period which extends either side of the high summer period, accommodation on offer ranges from large mixed-sex communal dormitories (matratzenlager) to two- or four-bedded rooms suitable for couples or families. Sheet sleeping bags are obligatory, so take your own. Separate-sex washrooms with showers are the norm, although some of the older and more remote huts are still rather basic in their amenities. However, despite the name, most of Austria’s huts resemble mountain inns rather than the simple refuges of old. Wardens provide refreshments, snacks, meals and drinks (coffee, tea, hot chocolate, lemonade, beer and wine), with a choice of evening meals sometimes matching in variety the menus of local valley restaurants. (See Appendix C for a translation of menu items.) In ÖAV and DAV huts, the evening menu usually includes a Bergsteigeressen (literally, the mountaineer’s meal – available only to Alpenverein members). Low-cost and high in calories, for the hungry walker prepared to take ‘pot luck’ the Bergsteigeressen offers very good value. Since most of the income for self-employed hut wardens is derived from the sale of food and drinks (the overnight fee goes to the club owning the hut), it follows that all users ought to make some purchases. Self-catering facilities are not provided, other than in bivouac huts and winter rooms.

Walking group near Grieralm in the Tuxertal (Zillertal Alps, Route 33)

Many walks in this guide choose a mountain hut as their destination, for the majority are not only situated among exciting landscapes, but have refreshments available on arrival. Multi-day hut-to-hut tours, of which several are included in this book, are an Austrian speciality worth tackling.

Huts belonging to either the ÖAV or DAV are divided into three categories which offer discounts of varying amounts on overnight charges (not meals) for Alpenverein members – including members of the UK branch of the Austrian Alpine Club (see below).

When arriving at a mountain hut remove boots before entering, place them on a rack in the bootroom, and help yourself to a pair of hut shoes (clogs or slippers) provided. Locate the warden to book bedspace for the night, and make a note of meal times. It is often possible to purchase a litre of boiled water – Teewasser - to make tea or coffee for yourself between meals, so carry a supply of teabags and/or instant coffee with you. Make your bed as soon as you have been allocated a room, using your own sheet sleeping bag (sleeping bag liner); blankets and pillows are provided, but keep a torch handy. Lights out (Hüttenruhe) is usually 10pm. Before leaving in the morning, make sure you have entered details of your planned route and destination in the visitors’ book provided.

Holiday packages providing both accommodation and travel can offer a very useful service at competitive prices for independent walkers looking for a base in specific locations. The following tour operators are among many with packages to various Austrian resorts: Crystal Holidays (www.crystalholidays.co.uk), HF Holidays (www.hfholidays.co.uk), Inghams (www.inghams.co.uk), Inn Travel (www.inntravel.co.uk) and Thomson Lakes and Mountains (www.thomsonlakes.co.uk). There are, of course, many other UK and Irish tour companies that organise all-inclusive walking holidays in Austria.

Evening light at the Stripsenjochhaus (Kaisergebirge, Route 63)

Founded in Vienna in 1862 the Österreichischer Alpenverein is the world’s second oldest mountaineering club (Britain’s own Alpine Club began in 1857), with one of the largest memberships. In addition to the provision and maintenance of mountain huts, the club is involved in organising mountaineering courses, waymarking and maintaining footpaths and the production of maps and guidebooks.

In 1948 a UK section, officially known today as Sektion Britannia, was established to promote and facilitate visits to the Eastern Alps for UK-based enthusiasts. From its current headquarters in Dorset, the AAC produces a quarterly newsletter, organises a regular programme of lectures, walks and meets, and supports various alpine hut projects with financial donations, but its main attractions for many members must surely be reduced hut charges and mountaineering insurance. Anyone planning to undertake a mountain walking holiday in Austria is strongly recommended to join, for as the late Cecil Davies wrote in Mountain Walking in Austria (the predecessor of this guide): ‘Apart from the priorities and reductions at the huts … if you are an AV-member in an AV hut, you “belong”’.

Austrian Alpine Club (UK)

Unit 43, Glenmore Business Park

Holton Heath, Poole, Dorset BH16 6NL

tel 01929 556 870

website: www.aacuk.org.uk

Summit ridge of the Bielschitza (Karawanken, Route 101)

Austria’s mountains make an almost perfect destination for the first-time visitor to the Alps. Though many regions have glaciers, snowfields and abrupt rock walls, on the whole the mountains are not as intimidating as some of their larger neighbours in the Central and South-Western Alps. That is not to suggest there’s a shortage of dramatic scenery – far from it! And the routes described in this book have been chosen to make the most of Austria’s rich landscape diversity – the lakes, flower meadows, tiny hamlets, huts, and abundant vantage points that can take your breath away with surprise.

With more than 40,000km of paths to choose from, the principal objective of each walk is to enable you to enjoy a day’s exercise among some of Europe’s best-loved mountains. But to gain the most from a walking holiday in Austria, it is advisable to be reasonably fit before you go, for most routes described here involve considerable uphill effort.

If you’ve never walked in the Alps before, avoid being too ambitious in your plans for the first few days until you’ve come to terms with the scale of the terrain. A rough guide in terms of time, distance and height gain and loss is given at the head of each walk description, which should aid the planning of an itinerary.

The walks fall into three categories, graded 1–3, with the highest grade reserved for the more challenging routes. This grading system is purely subjective, but is offered to provide a rough idea of what to expect. Grade 1 walks are fairly modest and likely to appeal to most active members of the family, while the majority of routes are graded 2–3, largely because of the nature of the landscape which can be pretty challenging. The grading of walks is not an exact science and each category covers a fairly wide spectrum. Inevitably there will be overlaps and variations and, no doubt, a few anomalies which may be disputed by users, but they are offered in good faith and as a rough guide only.

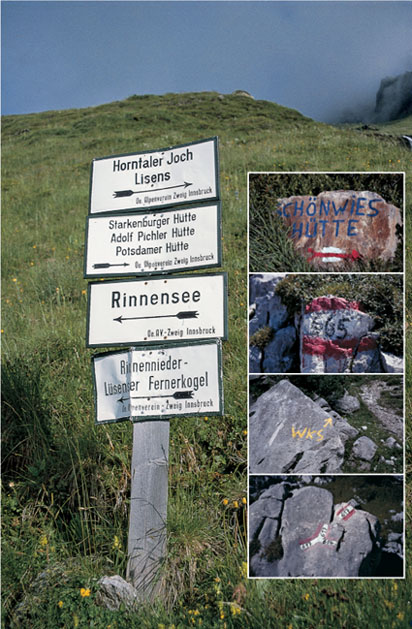

Most of the paths adopted by these routes are well maintained, signed and waymarked. These waymarks (invariably red and white bars) may be found on rocks, trees, fenceposts or other immovable wayside objects. Some of the trails are colour coded with additional numbers or letters, and this information will usually be translated onto relevant maps and signposts.

Signposts will be found at significant points (usually major path junctions) along the way, indicating not only the path’s destination, but an estimate of the time it will take to get there with Std being an abbreviation of Stunden (hours). On occasion you may come upon a sign which says Nur für Geübte, which means only for the experienced – an indication that the route ahead could be difficult, exposed, or safeguarded with fixed ropes, chains or ladders.

Main photo: Trail signing is good almost everywhere Inset photos (top to bottom): Hut keepers sometimes add direction markers on rocks along the trail; Be warned that route numbers added to waymarks do not always correspond with numbers on maps; Wilder-Kaiser-Steig waymark (Kaisergebirge, Routes 66 and 68); Waymarks below Tör (Dachsteingebirge, Routes 76, 78 and 79)

Fixed cables on the Jubilaumssteig (Kaisergebirge, Route 64)

Sections of route marked Klettersteig (the German equivalent of Italy’s famed via ferrata) often involve sustained exposure and a concentration of metal ladders, rungs and fixed ropes. To attempt such routes one needs to have scrambling experience and specialised equipment such as harnesses, slings and karabiners. A few examples of such routes are described in this guide – with adequate advanced warnings given.

Rarely do described routes stray into unpathed terrain, but where they do, cairns and/or additional waymarks often guide the way. In such places it is essential to remain vigilant to avoid becoming lost – especially in poor visibility. If in doubt about the onward route, return to the last point where you were certain of your whereabouts and try again. By consulting the map at regular intervals along the walk, it should be possible to keep abreast of your position and anticipate junctions before you reach them.

For safety’s sake never walk alone on remote trails, moraine-bank paths or glaciers. Should you prefer to walk in a group but have not made prior arrangements to join an organised walking holiday, a number of tourist authorities arrange day walks with a local guide. Enquire at the tourist office of your nearest resort.

The rock wall of the Kuchelmooskar en route to the Plauener Hut (Zillertal Alps, Route 32)

Experienced hillwalkers will no doubt have their own preferences in regard to clothing and equipment, but the following list is offered to newcomers to the Alps. Some items will clearly not be needed if you envisage tackling only valley routes.

In common with 26 other European countries, Austria is home to the tick, an insect second only to the mosquito for carrying disease to humans – the primary illness in Europe being Tick-Borne Encephalitis (TBE). Ticks live in long grass, shrubs and bushes, and can survive up to 1500m, attaching themselves to humans and animals as they pass. Walkers and campers are especially vulnerable. Victims often do not realise they have been bitten, because the tick injects a toxin which anaesthetises the bite area. Since ticks prefer warm, moist, dark areas of the body, it is advisable to check for bites in those pressure points where clothing presses against the skin, at the back of the knee, armpits and groin. Should you discover a tick, remove it by firmly grasping the insect as close to the skin as possible (tweezers are best), and using a steady movement pull the tick’s body outwards without twisting or jerking. The following methods of prevention are suggested:

For further information visit www.masta-travel-health.com.

A variety of maps cover much of Austria, the best being those published by the ÖAV/DAV under the heading Alpenvereinskarten. Accurate and beautifully drawn, they have a robust quality missing on some of the commercial maps available, and are usually published at a scale of 1:25,000. However, the amount of detail included at this scale is perhaps more than most routes in this guide require. Sheets at a scale of 1:50,000 are available from Kompass, Freytag & Berndt, and Mayr, with some districts treated to 1:30,000, 1:35,000 and 1:40,000 scale.

Graukogel from the Palfnerscharte (Hohe Tauern, Route 83)

Kompass Wanderkarte sheets have huts, hotels, and paths (with numbers) clearly marked in red for ease of identification. Be warned that some of the older maps were produced on poor-quality paper which tears easily, especially on the folds, and you may find that a single sheet will not last a full week. More recently-published sheets are slightly more weatherproof. A slim booklet (in German) accompanies these maps, with local information and brief walk suggestions.

Freytag & Berndt produce sheets of a similar quality to those of Kompass, this time with huts being ringed. The accompanying booklets are perhaps less useful than those of Kompass, although the latest ones include GPS information.

Mayr maps are produced in Innsbruck and, once more, are of similar quality to F&B and Kompass sheets. The paper tears easily and wears quickly at the folds, but the associated booklets give rather more detail with their walk suggestions than those of Kompass.

Specific sheets recommended for routes in this guide are outlined at the head of each walk description, but please note that in some instances names on maps do not match those that appear on local signposts. And the altitude measurements shown on some sheets may be at variance with those quoted on maps produced by different publishers.

In this guide we begin in the west of Austria and work eastwards, exploring some of the finest valleys and their neighbouring mountains from resort bases, visiting mountain huts, lakes and viewpoints, and sampling a few multi-day hut tours.

Each mountain group is treated to a separate chapter, for which a map is provided as a locator. While individual walks are marked on the basic maps produced especially for this book, you will need a detailed topographical map to follow the route as described. The introduction to each chapter includes a note of specific map requirements, with details of the various villages or valley resorts, their access, facilities, tourist offices, huts and so on, followed by a number of walks based in the district. All the walks are listed in Appendix E at the back of this book, while an explanation of the grading system is found above.

Distances and heights are quoted throughout in kilometres and metres. This information is sourced directly from the recommended map where possible, but because of countless zigzags on some routes, it has been necessary to resort to estimates in terms of actual distance walked. Likewise times quoted for each walk are approximations only. They refer to actual walking time and make no allowances for rest stops, picnic breaks or interruptions for photography – such stops can add considerably (25 to 50 per cent) to the overall time you’re away from base, so it is important to bear this in mind when planning your day’s activity. Although such times are given as an aid to planning they are, of course, subjective, and each walker will have his or her own pace which may or may not coincide with those quoted. By comparing your times with those given here, you should soon gain a reasonable idea of the difference and be able to compensate accordingly.

Abbreviations are used sparingly, but some have been adopted through necessity. While most should be easily understood, the following list is given for clarification:

From the frontier ridge above the Tübinger Hut, the twin Seehorn summits rise above their glacier (Route 11)

| AAC | Austrian Alpine Club (UK branch) |

| ATM | Automated Teller Machine (‘hole in the wall’ cash machine) |

| AV | Alpenverein (maps) |

| DAV | Deutscher Alpenverein (German Alpine Club) |

| FB | Freytag & Berndt (maps) |

| hrs | hours |

| km | kilometres |

| m | metres |

| mins | minutes |

| ÖAV | Österreichischer Alpenverein (Austrian Alpine Club) |

| PTT | Post Office (Post, Telephone, Telegraph) |

| TVN | Touristenverein Naturfreunde |

The path to the Stüdl Hut above the Lucknerhaus, with Grossglockner ahead (Hohe Tauern, Route 98)