A woman who doesn’t wear perfume has no future.

—PAUL VALÉRY

MARIE SOPHIE OLGA ZÉNAÏDE GODEBSKA—“Misia” to the Paris Bohemian elite—was, like Chanel, banished at age ten to a Catholic convent. As a child, her skill at the piano delighted composers Franz Liszt and Gabriel Fauré. Tutored by stern nuns, Misia over time became an accomplished pianist. “Neglect taught Misia independence and loneliness taught her courage.”

Unhappy and oppressed by convent life, Misia escaped to Victorian London at eighteen and engaged in a series of trysts with older men. Eventually, she rejoined her family in Belgium where, barely twenty, she inherited a large sum of money from a rich uncle. A year later, Misia married twenty-five-year-old Thadée Natanson. The couple moved to Paris, where her beauty combined with a tart’s “above-it-all iconoclast attitude” brought her full sail into the free and easy Bohemian lifestyle at the turn of the century. For the next few years, Misia lived a rough-and-ready life with “speech peppered with four-letter words,” seducing some of the most creative talent in Paris. Marcel Proust portrayed her as Princess Yourbeletieff, whom he found as dazzling and seductive as the Ballets Russes itself. Misia and husband Thadée quickly joined a band of what were then considered unconventional artists. She became a favorite model for Vuillard, Bonnard, Toulouse-Lautrec, and Renoir. Each artist painted her many times over. Today, portraits of Misia at the piano, at a table, and at the theater hang in some of the world’s most important museums. Attracted to the performing arts, Misia entered the world of theater and ballet, becoming the close friend of ballet impresario Serge Diaghilev. Misia’s biographers describe her as “enthroned at his [Diaghilev’s] side, the eminence rose of the Ballets Russes.”

The face that would fascinate world-renowned French painters: Misia Godebska, 1905. (illustration credit 2.1)

To know Misia was to be admitted to Diaghilev’s exclusive circle and the post–World War I elite of Paris. But Misia was not the princess drawn by Proust. In her three marriages, she was Madame Thadée Natanson; Madame Alfred Edwards (a very rich businessman and notorious coprophiliac who forced Natanson to relinquish Misia in payment for a debt); and, finally, wife of Spanish painter José-Maria Sert.

Chanel met Misia when they were guests at a dinner offered by renowned Comédie-Française actress Cécile Sorel. Years later Misia remembered their first meeting and described the event in an unpublished memoir:

[I] was drawn to a very dark-haired young woman … she did not say a word [but] radiated a charm I found irresistible … she was called Mademoiselle Chanel. She seemed to me gifted with infinite grace … when I admired her ravishing fur—she put it on my shoulders, saying with charming spontaneity she would be only too happy to give it to me … her gesture had been so pretty that I found her completely bewitching and thought of nothing but her.

When I visited her boutique on the rue Cambon, two women were there talking about her, calling her “Coco” … this name upset me … my heart sank … I had the impression my idol was being smashed. Why trick out someone so exceptional with so vulgar a name? [Suddenly] the woman I had been thinking about since the night before appeared … magically the hours sped by … it was I who did most of the talking, for she hardly spoke. The thought of parting from her seemed unbearable … that same evening Sert and I dined at her apartment … in the midst of countless Coromandel screens, we found Boy Capel.

Sert was really scandalized by the astonishing infatuation I felt for my new friend. I was not in the habit of being carried away like this … Then [on the death of Boy Capel] Coco felt [the loss] so deeply that she sank into a neurasthenic state; and I tried desperately to think of ways to distract her … Sert and I took her to Venice the following summer …

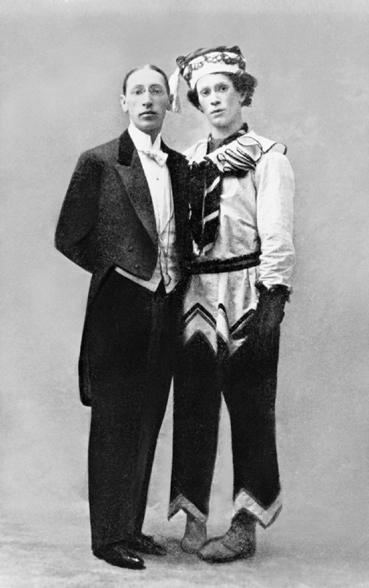

Igor Stravinsky and Vaslav Nijinsky, at the Théâtre du Châtelet, Paris, attending the premiere of the 1911 ballet Petrushka, produced by Diaghilev. (illustration credit 2.2)

Something had clicked between these two beautiful women. Gabrielle Chanel and Misia Sert’s atoms had hooked, as the French say. Of Misia, Chanel would remember: “I remained forever a mystery to Misia—and therefore interesting. She was a rare being who knew how to be pleasing to women and artists. She was and is to Paris what the goddess Kali is to the Hindu pantheon—at once the goddess of destruction and creation.”

Misia’s biographers, Arthur Gold and Robert Fizdale, summed up how they believe she valued Chanel in those early years of their intimate friendship:

Chanel’s designs imposed an expensive simplicity—an almost poor look on rich women—and she made millions in the process. Her genius, her generosity, her madness combined with her lethal wit, her sarcasm, and her maniacal destructiveness intrigued and appalled everyone.

Over the years Misia and Chanel’s friendship would ebb and rise with time; nevertheless, they maintained a twosome sharing innumerable secrets, including the morphine they used to keep going, not to live but to hold on.

AS THE OLD WORLD of privileged aristocracy drew to a close, Chanel became a symbol of a new age. At thirty-five Chanel began inventing Coco—a woman of the Roaring Twenties. She launched her casual or “poor look” line of expensive women’s wear: traveling suits of wool jersey with a tailored blouse, sports dresses, and low-heeled shoes.

The magazines of the day reproduced her creations. It was all about jersey as America discovered Chanel. In 1918, she could afford to pay 300,000 gold francs to purchase a sumptuous villa at Biarritz—the headquarters of her business in the south of France. As early as 1915, Harper’s Bazaar declared, “The woman who hasn’t at least one Chanel is hopelessly out of fashion … This season the name of Chanel is on the lips of every buyer.”

Misia, ca. 1910. (illustration credit 2.3)

If Chanel was on the lips of fashion editors, victory against the Boche was on the minds of the Allies: English, French, Italians, and a host of others. U.S. president Woodrow Wilson entered his second term in office in March 1917 and persuaded the Congress to declare war on Germany in April. The Teddies, as the French called the Yanks, led by General John J. “Black Jack” Pershing, sailed to France as rich Parisians fled to Deauville and Biarritz, flocking to Chanel’s boutiques to try on her women’s wear.

Momentous events rocked Europe. The October 1917 revolution brought Lenin and Trotsky’s Bolsheviks to power; Turkey surrendered to the Allies; and at home, Germans were starving. By 1918 the Allies, reinforced by American troops, stopped the Kaiser’s spring offensive on the Western Front. On November 11, 1918, the Allies signed an armistice with Austria-Hungary and Germany. World War I had come to an end.

As demobilized German troops began the long slog back to their homes, Champagne corks popped in Paris. Chanel was wearing “big loose jerseys that were as simple as a boarding school girl’s frock, and extraordinarily chic.” She was also being driven about in a Rolls-Royce limo while her customers were paying 7,000 francs for a gown—the equivalent of $3,600 in today’s money.

But in Europe inflation was beginning to haunt the Continent’s financial institutions. In simple terms the cost of a loaf of bread in Germany, expressed in U.S. dollars, had doubled from 13 cents a loaf in 1914 to 26 cents in 1919. Thereafter the cost doubled, tripled, and reached an inconceivable level. The German economy was headed for a devastating crash.

TWO GERMAN CAVALRY OFFICERS, thousands of miles from Paris, were struggling to return home. Lieutenants Baron Hans Günther von Dincklage and Theodor Momm, fellow officers and friends serving in Hannover’s elite Königs-Ulanen Regiment, were among the millions of defeated German and Austrian soldiers trying to make a new life after four years of war. Each had fought on the Eastern Front as mounted cavalry officers and later in the mud and gore of the trenches as dismounted “cavalry rifles.” They returned from the east to a defeated homeland and chaotic politics. The Bolshevik Revolution in Russia and a revolt at the German naval base at Wilhelmshaven had spread across the country and forced the abdication of Kaiser Wilhelm II. A long-standing British blockade brought widespread starvation to the country.

In June 1919, a newly formed German Republic agreed to the terms set out by Britain, France, Italy, and the United States in the Treaty of Versailles. Germans would come to believe that the reparations demanded by the terms of the treaty were the cause of the coming devastating economic and financial hardships. Adolf Hitler would tear up the treaty when he came to power over a Germany scorched by defeat; a nation that hungered for the restoration of German greatness. “A people continually torn by inner contradictions which make them uncertain, unsatisfied, frustrated and anxious to be released from the strain of individual decision and choice. Their greatest luxury is to have someone else make the decisions and take the risks.”

Lieutenant Hans Günther von Dincklage (center) and fellow officers on the Russian front, ca. 1917. (illustration credit 2.4)

Theodor Momm’s wealthy family had owned a successful textile business in Germany and Belgium before the war. Returning to civilian life in early 1919 he took over the firm in Bavaria. Over the years Momm prospered with business ventures in Germany, Holland, and Italy. With the coming to power of Hitler, Momm joined the National Socialist Party of Germany (NSPD)—the Nazi party—and became a supporting member of the paramilitary Schutzstaffel (SS), in 1938.

Dincklage, the aristocrat and descendant of two generations of German army officers, joined the German military intelligence service. His grandfather Lieutenant-General Georg Karl had fought in the Franco-Prussian war (1870–1871) when German armies battered the forces of Napoleon III and annexed the territories of Alsace-Lorraine. Dincklage’s father, Hermann, held the rank of major of cavalry, and both father and son fought against the Allies in World War I—Spatz on the Russian front with his Königs-Ulanen cavalry regiment. Dincklage’s English-born mother, Lorry Valeria Emily, was the sister of a senior German naval officer, Admiral William Kutter. The Dincklages shared with many Germans, and certainly the German officer corps, a sense of Völkisch—a nationalistic and racist culture of war, dramatized by the trauma of 1914–1918.

With the execution of Czar Nicholas II and his family in Soviet Russia, the German Revolutionary Communist Workers’ Party was founded in Berlin. Dincklage joined a body of German officers to fight Communists with the far-right Free Corps. In 1919, members of the Free Corps murdered the intellectual leader of the German Communists, Rosa Luxemburg. Later, Hermann Göring would label the Free Corps “the first soldiers of the Third Reich.” Years later when Heinrich Himmler became Hitler’s chief of the SS, he honored the Free Corps, claiming that its officers were spiritually united with his SS.

ACCORDING TO FRENCH COUNTERINTELLIGENCE, sometime after 1919 Dincklage was recruited by German military intelligence as agent No. 8680F, working for the Weimar Republic. This parliamentary regime would last until March 1933, when the newly elected Nazi-run government put an end to the Republic.

Dincklage was the perfect candidate for a career in military intelligence and work as a clandestine agent. He was fluent in English and French, had the impeccable good manners of the old school, used men and seduced women without mercy, and turned his recruits into informers and agents. Blond, blue-eyed, of medium height (five foot eight), graceful in manner, and urbane, Spatz Dincklage had brooding good looks and a warm, outgoing personality that appealed to both sexes. But Spatz was certainly no Aryan playboy, as some biographers have cast him. He was trained by his masters in Berlin to be what every spy must be: resourceful, observant, cool, sensitive, empathetic, and able to blend in with his surroundings. He hid his end game, attracting useful targets to betray their countries by collecting strategic and tactical information and documents useful to German military and naval intelligence.

Although a spy, Dincklage was never really in danger in pre–World War II France or later, in Poland or Switzerland. Operating as a German diplomat, he was shielded by the cloak of diplomatic immunity. The worst thing that could have happened to him in peacetime was expulsion. But neither the French nor the Swiss saw much benefit to be gained from creating a fuss with the prickly Nazi regime by expelling one of its diplomats.

IN THE WINTER-SPRING of 1919–1920, the splendor of Venice cast a spell over Chanel. With its serpentine canals and alleyways opening onto grandiose, often sunny piazze and campi, Venice was a magical place in every season. Misia and José-Maria Sert would recall how Chanel prayed and wept, torn by the sorrow and humiliation of knowing that she had not been alone in Boy Capel’s affections—just as surely as the Italian countess must have wept at the news. Isabelle Fiemeyer described how Chanel prayed under the dome of the seventeenth-century church, the Santa Maria della Salute, while a thousand candles burned and flickered in the gloom under the watchful eyes of Titian’s five saints.

As winter gave way to spring, Chanel’s spirit returned. Under the spell of the Serts’ good humor and the city’s charm Chanel came out of the dark and brooding mood that had possessed her.

IN THE TURBULENT TRANSITION from war to peace, the automobile became an affordable toy of the rich and a danger for pedestrians. As President Woodrow Wilson was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, prohibition was enacted in the United States; hordes of wealthy Americans bore down on Paris; Benito Mussolini entered Italian politics; and Communism and the Soviet revolution infected Europe, terrifying the middle and upper classes. Meanwhile, at a German military hospital in Pomerania, a little man with a toothbrush mustache was recuperating from wounds to his eyes suffered in an English gas attack at Ypres on the Western Front. His name was Adolf Hitler.

Paris was at the epicenter of the postwar cultural earthquake—a period that the French would call Les Années folles. F. Scott Fitzgerald called it the Jazz Age; Gertrude Stein and Ernest Hemingway, the Lost Generation. Chanel biographer Pierre Galante called this moment in time “The Crazy Years: when artists hungered for glory; and the man on the street sought pleasure; and the joy of being alive after the terrors of the war to end all wars.”

By 1920, Paris was a Mecca for all those who wrote, painted, composed, and sculpted. Artists, musicians, composers, and writers were drawn to this now-jubilant city. They sought to be part of a new era—to drink and taste a life brimming with joy, amusements, and creative inventions. Parisian society met in street cafes, ateliers, and at soirees animated by brilliant conversation, music, and a passion for the arts. The city had “forgotten the black years.” Natives and expats such as Hemingway begged for something new. In painting, sculpture, discourse, and literature, there was a hunger for original work. Painters such as Picasso, Modigliani, Braque, and Marie Laurencin were the rising stars. Le Corbusier offered something brand new in dwellings; Ravel and Stravinsky in music; Diaghilev and Nijinsky in dance; Gide, Cocteau, Mauriac in literature. Jazz symbolized the heedless gaiety of the Années folles; and with the birth of mass industries, automobiles, flapper dancers, radio, and popular sports, utopia was in the air. Rich Europeans developed a credo of progress, unchained individualism, and extravagance. Money jingled and jangled in bourgeois pockets, begging to be spent. In Paris’s Montmartre and Montparnasse neighborhoods, Hemingway drank and dined with fellow expat writer Henry Miller, soaking up the ambience and plugging snapshots of the moment into their work. The F. Scott Fitzgeralds got to France in 1921 and were bored by it all. They never learned to speak but a few words of French, and Zelda and Scott returned home so their baby could be born in America in October 1921. The couple returned to France in April 1924. A year later Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby was published, and the couple settled in Paris, where they would meet Ernest Hemingway in May 1925.

The decade brought joy to some and terror to others. For Chanel, the twenties began with a family tragedy. In a letter from Canada, her younger sister, Antoinette, poured out her distress over a souring marriage to a handsome Canadian officer. The man had brought Antoinette from France to a miserable existence in the hinterland of Ontario. Adored by Chanel, the lovely and fragile Antoinette had helped launch the Chanel boutiques. But now she was begging Chanel for money to return to Paris. Despite Antoinette’s obvious unhappiness, Chanel urged her younger sister to stick with the marriage.

Chanel, 1920, the year her younger sister, Antoinette, died of the Spanish flu. (illustration credit 2.5)

Instead, Antoinette escaped with a young, good-looking Argentinean—of all people, a man Chanel knew in Paris and recommended to Antoinette’s Canadian family. They had taken the man in, and Antoinette fled with him to Buenos Aires in 1920. That same year, Antoinette died in Buenos Aires of the Spanish flu that would eventually kill more than 50 million people worldwide.

Back from Venice with Misia in the autumn of 1920, Chanel soon became a locomotive for Jazz Age fashion, determined to revolutionize women’s wear. She was bent on turning ladies from powdered objects of glamour to lithe silhouettes wearing her little black dresses and a wardrobe of flexible tubular wear like the boa. She would make a fortune as the beacon of women’s ambitions and emancipation: free to earn, to love, to live as they wished; not under the thumb of any man—“liberated from prejudices; and not disdaining homosexual adventures.” Her designer clothes inspired flappers to wear sheer short-sleeved and sometimes sleeveless dresses and to roll down their stockings to just below their knees. French and American fashion magazines such as Mademoiselle, Femina, and Minerva celebrated her creations: “Chanel launches the ravishing dark green sports suit.… Lady Fellowes sports a Chanel raw silk dress at the Ritz … Chanel launches the black tulle dress.… Chanel’s creation for evening: a white satin sheath covered over with an embroidered and beaded cloak.” Still, critics could be ferocious: “Women were no longer to exist … all that’s left are the boys created by Chanel.”

Harper’s Bazaar featured Chanel in a mass of pearls (a gift from Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich) and clad in a short, dark tunic and pleated skirt. In another photograph, she sports black silk pajamas and is biting a pearl on her necklace; and in another, she is running the pearls through her sensuous lips while reclining in the exotic setting she loved: the Coromandel screens, the leather, the silks and satins, all the while watched by a Chinese fawn and bronze lion.

Ever on the prowl for male conquests, Chanel set her sights on Igor Stravinsky, Pablo Picasso, the Russian Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich, and the man she would love and be loved by for a lifetime, Pierre Reverdy. It’s a shame that Chanel and Ernest Hemingway never got together. Her fingernails might have popped Papa’s inflated macho ego. For however independent, Chanel, the creative dynamo, needed admiration and to be loved. She had to have a man at her side, always seeking love yet never finding satisfaction. In one of her maxims she wrote: “not to feel loved is to feel rejected regardless of age.”

Misia Sert viewed her friend as an enigma: “For the wealthy woman she imposed an expensive simplicity … and made millions doing it. Chanel’s genius, her generosity, the façade of the self-made woman, her devastating sarcasm, and her ferocious capacity for destruction terrified and intrigued everyone.”

Terrified or not, Paris celebrated her genius for creating women’s high fashion, costumes for ballet and amusements, decorations, and jewelry. Ever the innovator, Chanel created a feminine personage not seen before on the stage of Paris society.

She mastered the art of social climbing—and Parisians delighted in it. “An orphan denied a home, without love, without either father or mother … my solitude gave me a superiority complex; the meanness of life gave me strength, pride; the drive to win and a passion to greatness … and when life brought me lavish elegance and the friendship of a Stravinsky or a Picasso I never felt stupid or inferior. Why? Because I knew it was with such people that one succeeds.” Such was the self-made image Coco had of herself and the legend she wanted the outside world to believe—that of a heroic Marianne audaciously battling daunting odds to achieve fame, wealth, power, and acceptance by the elite.

By the early 1920s Chanel was no longer a well-known trades-person—she was now a celebrated patron of the arts. She underwrote Le Sacre du Printemps, a ballet choreographed and produced by Serge de Diaghilev, and took into her new house, Bel Respiro in the Paris suburb of Garches, the family of Igor Stravinsky, the Russian composer and pianist. When Chanel wasn’t dallying with Misia at her new apartment, a stone’s throw from the Champs-Élysées, she enjoyed flirting with Stravinsky. The swank flat at 29, rue du Faubourg-Saint-Honoré was decorated by Chanel and Misia in tones of “beige, white and chocolate brown.” In her designer residence with gardens stretching to the avenue Gabriel, Chanel created a center for Parisian cultural life—quite a step up from her days as just a clever playgirl in the Royallieu follies staged by Étienne Balsan. The crème de la crème of Paris—artists, aristocrats, the very rich and often notorious characters from the demimonde—mixed at her lunches, dinners, and soirees. Chanel’s set often began the evening imbibing at the Boeuf sur le Toit (Ox on the Roof), a Right Bank night spot located on the rue Boissy-d’Anglas, just a few hundred meters from Chanel’s residence. From the moment the Boeuf opened in 1922, it was “the place,” boasting the smallest stage, “but the greatest concentration of personalities per square meter.” The Boeuf became a Mecca for the Parisian creative elite, “a place where people threw their arms about each other to say hello while glancing over each other’s shoulders to see who else was there … and where wit was as compulsory as Champagne: ‘One cocktail and two Cocteau’s.’ ” Later, Chanel and her entourage headed for supper chez Chanel or to dance at the Count de Beaumont’s. “Love affairs between writers and artists (real or fake) and millionaires started and ended during those evenings. They drank, they danced, and loved.” And Chanel held her own among them, including the Serts, the Beaumonts, Stravinsky, Picasso, Cocteau, Diaghilev, and Pierre Reverdy, a down-and-out modern poet of the day admired by artists and writers Jean Cocteau, Max Jacob, Juan Gris, Braque, and Modigliani. Chanel’s newfound friends appreciated her “talent, wit and intelligence … her minimalist approach to fashion was not far from their abstract ideas of art.”

Sergei Diaghilev with Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971) in Seville during their Ballets Russes collaboration, ca. 1923. (illustration credit 2.6)

Between 1921 and 1926 Chanel began an on-again off-again love affair with Pierre Reverdy. In time their relations matured into deep friendship that would endure more than forty years. She often served as the poet’s inspiration: “You do not know dear Chanel how shadows reflect light; and it is from the shadows that I nourish such tenderness for you. P.”

But Reverdy the aesthetic, the poets’ poet who enchanted Chanel with phrases like “What would become of dreams if people were happy,” couldn’t swallow the everyday terrestrial world of Chanel. On May 30, 1926, after burning a number of manuscripts in front of a few friends, he retired to a little house just outside the Benedictine abbey at Solesmes, where he lived for thirty years with his wife, Henriette.

Chanel loved him and he loved her. Biographer Edmonde Charles-Roux believed that Reverdy, who had converted to Catholicism the same year, went into exile seeking inspiration and God. His separation from Chanel was inevitable.

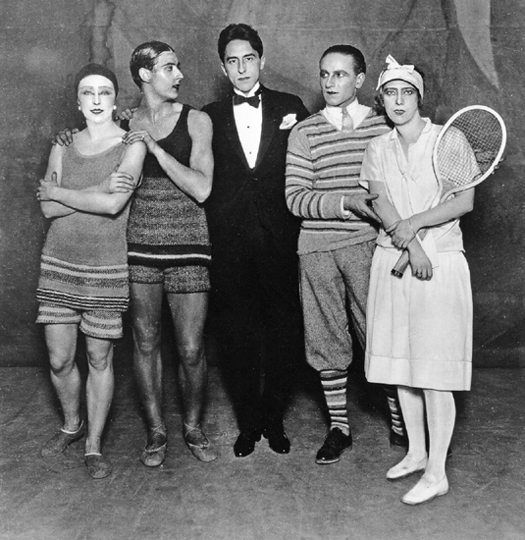

French poet, playwright, and film director Jean Cocteau (center) with (from left) Lydia Sokolova (born Hilda Munnings), English dancer and choreographer Anton Dolin, Leon Woizikowsky, and Bronislava Nijinska after the first performance of Le Train bleu in Britain, at the Coliseum Theatre, London. Costumes designed by Chanel. (illustration credit 2.7)

Though she was hurt at first, Chanel eventually accepted fate. Nevertheless she never really lost Reverdy. He would visit Paris from time to time and somehow be available.

Over their long years of friendship Chanel gave Reverdy strength, confidence in his creative ability, and material assistance. She was generous and tactful, secretly buying up his manuscripts, financing him through his publisher, and underwriting his work. Despite her own success, Reverdy’s darkest fears and somber view of life struck a melancholy chord in Chanel—a remembrance of her childhood. For Reverdy, son of a winegrower, was someone of her breed. Even though he had adopted a quasi-monastic lifestyle, their affair never seemed to end.

WHEN REVERDY WAS NOT available the handsome Russian Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich was. He had fallen out of favor in 1916 at the court of his first cousin, Nicholas II, emperor of all Russia. Nicholas was not amused when the twenty-one-year-old guardsman had a drawn-out homosexual love affair with his handsome, cross-dressing, and bisexual cousin, Prince Felix Yusupov. (Prince Felix chose Dmitri to help carry out the murder of Grigori Rasputin, the Russian monk whose influence on the Czarina was feared in court circles and the Russian parliament.) Dmitri was banished to the Persian front in the early days of World War I—an act of grace as it turned out, because it spared him the ravages of the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 and probably saved his life. Dmitri eventually fled to France with few belongings but his stock of precious jewels, including strings of fabulous pearls. Some would end up draped around Chanel’s neck, launching another Chanel fashion creation: costume jewelry.

Once in France, and a pretender to the Russian throne, the tall, elegant, and alcoholic Dmitri Pavlovich grieved with other Russian exiles over the annihilation of the Romanov family. But Dmitri could be lively and fun loving. His good looks, green eyes, long Romanov legs, and charm seduced Chanel. It was just what she needed after the intensity of Reverdy and a brief tryst with Stravinsky.

In late 1920, when the Grand Duke entered Chanel’s intimate life, Paris wags dubbed her new adventure “Chanel’s Slavic period.” In homage to her new paramour, Coco wanted to create an authentic Russian line. She hired Dmitri’s sister, the Grand Duchess Marie, and her exiled Russian royal friends. The Czarina’s former ladies-in-waiting delivered embroidery and beadwork at far less cost than demanded by French artisans. They fashioned stunning combinations of needlework and fur, such as Chanel’s own white coat embroidered and trimmed in Russian sable featured in a 1920 issue of Vogue magazine.

Augmenting her Slavic collection, Chanel included a component never before seen on the continent: Russian-inspired peasant dresses worn with a draping of pearls, some with squareneck tunic tops and elbow-length sleeves, Oriental embroideries, chenille knitted cloches, and stunning waterfall gowns of crystals and lignite jet. And for those wanting something more classic, she brought out a line of modern garb: wool knits, dresses cut from fine French muslin cotton, tulle for day wear and lamé or metallic lace for an evening out. It was all very grand. Like her jersey line before it, Chanel’s “Russian look” was a great success. It sold so well that she was soon employing fifty Russian seamstresses in addition to designers and technicians, all working at an expanded atelier on the rue Cambon under her critical eye.

Grand Duke Dimitri, Chanel’s lover—who helped Chanel launch her successful Chanel No. 5 perfume, 1910. (illustration credit 2.8)

The Grand Duke brought Chanel something rare and more precious than a few strings of pearls. Just as Boy Capel’s English knit sweaters had inspired her to copy that mode for women, Pavlovich helped to inspire her to create the Russian-Slavic collection—and to venture into perfume.

During WWI, women were wedded to their grandmothers’ lye soap for personal hygiene. Later, they used scents extracted from a combination of flowers—violets, roses, orange blossoms, jasmine—or scents from animal sources. For a night out, more sophisticated women applied powder and sprayed their bodies with floral mists. Men favored Bay Rum or Roger & Gallet cologne, liberally splashed about to mask unpleasant odors. Rumors now spread that Chanel was about to launch a “secret, marvelous eau Chanel.” The secret, according to Paris gossip, was known to the fifteenth-century Medici family of Florence. Women thought the perfumed liquid preserved their skin while men used it to cure razor burns.

The hallmark Chanel No. 5 flacon, illustrated by French artist SEM (Georges Goursat), ca. 1921. The bottle entered the New York Museum of Modern Art in 1959. (illustration credit 2.9)

By this time, the younger set in France was already beginning to wear Chanel’s little black dresses, sweaters, and short, pleated skirts. So why not marry a new fragrance to what was already fashionable? When it came to daubing a pearl of scent behind a feminine ear, on a wrist, or at the hollow of a shoulder curve, it was all about the sweet smell of success; it embodied poet Paul Valéry’s statement: “A woman who doesn’t wear perfume has no future.” It was about knowing how to dress and having the thousand-dollar allure of a Parisian hostess.

Chanel set out with the help of Dmitri and a Russian chemist friend to devise a scent that would become part of the folklore of the interwar years: a fragrant emblem for les garçonnes, the boyish emancipated females sporting a unisex allure who danced the tango and Charleston, sometimes smoked opium, and embraced the art of Cocteau and Picasso. These women boasted short, manly haircuts, men’s suit jackets and ties, culottes, and shift dresses shockingly cut to the knee, without sleeves but with Charleston fringes. Indeed, the right perfume would go along perfectly with makeup, fast cars, sports, travel, and the Charleston.

When Dmitri introduced Chanel to his Russian émigré friend, Ernest Beaux, the ex-czar’s official perfumer, a new fashion venture was launched. The Moscow-born Beaux had fled St. Petersburg after the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution to fight the “Reds.” He joined the anti-Bolsheviks’ White Russian armies and landed in the far north, near the Arctic Circle where the sun shone at midnight and where lakes and rivers give off a refreshing perfume. In France, where he quickly became a respected chemist and specialist in concocting exotic perfumes, Beaux was just then experimenting with using synthetic compounds to enhance various natural mixtures. At his laboratory in the south of France at Grasse, known as the perfume center of the world, Beaux, under Chanel’s watchful eye and delicate sense of smell, worked his magic. He insisted that he could capture the freshness of a sunny Arctic day in his test tubes.

Chanel found the perfumes of the day, extracted from violets, roses, and orange blossoms and put up in extravagant bottles banal. She told Beaux she wanted everything in the perfume—a scent that would evoke the femininity of a woman. Beaux’s genius was then to add synthetic chemical components to enhance the natural scents and stabilize the perfume so that the scent lingered on the skin—unlike the natural scents.

In 1921, Beaux presented Chanel with a series of concoctions, numbered from 1 to 5 and 20 to 24. At first, she chose the twenty-second one and offered it for sale. But it was No. 5 that delighted Chanel, and she decided it must be introduced in 1921 along with her collection. She would call the new fragrance Chanel No. 5.

Except to a handful of the initiated, the formula for making Chanel No. 5 remains secret. It is known to be exceptionally complicated. The perfume was, and still is, constructed of approximately eighty ingredients. The most important one is high-quality jasmine found only in Grasse.

Chanel banished the idea of a baroque bottle design her competitors used—no sculpted cupids or flowers. Rather, Chanel chose a geometric cube minimalist bottle—her modern concept of packaging.

The name she chose, her fetish number 5, was a revolution. It was serpentine, recalling the divine five heads of Hinduism or the five visions of Buddha. (Chanel would celebrate the number 5 time and again. Her collections were invariably offered to the public on February 5 and August 5 of every year.)

To promote her new invention, Chanel—like the shrewd peasant she was—believed in “word of mouth.” She tested Chanel No. 5 by inviting friends to dine with her at a posh restaurant near Grasse; there she furtively sprayed guests passing by her table—they reacted with surprise and pleasure. Pleased with the results, Chanel returned to Paris and quietly launched her new venture. She didn’t announce its arrival in the press. She wore it herself and sprayed the shop’s dressing rooms with it, giving bottles to a few of her high-society friends. Her perfume soon became the talk of Paris.

Chanel instructed Beaux to put No. 5 into production. “The success was beyond anything we could have imagined,” recalled Misia Sert. “It was like a winning lottery ticket.” And so Beaux’s juice, a woman’s perfume with a scent meant for a woman, was put into an Art Deco bottle and labeled “No. 5” with interlocking Cs back to back—and launched from Chanel’s rue Cambon boutique on May 5, 1921. The Chanel-Beaux creation would withstand the vicissitudes of the Great Depression and World War II. It was a fragrance that grandmothers and mothers would pay a small fortune to wear, and one that young women could hope to acquire one day.

For the next three years, with the help of Grand Duke Dmitri, Chanel successfully promoted No. 5 as a luxury perfume. Soon, she realized that to fully exploit the growing demand for No. 5, her modest enterprise would have to expand production.

On a Sunday in the early spring of 1923, Chanel dressed for a day at the Longchamp racetrack. The site was and still is today an elegant meeting place, located in the Bois de Boulogne where the Seine curves around the western extreme of Paris. It’s the place to go on a Sunday to see and be seen by Le Tout-Paris, to watch the “ponies” gallop around the oval, and to dine well after betting one’s money on some “gentleman-owner’s” horse.

But it was Pierre Wertheimer and his money that brought Chanel to Longchamp that afternoon. Théophile Bader, who kept in touch with the “world of frippery,” arranged the meeting. As a prince of the French retail trade and one of the owners of Paris’s major emporium, Les Galeries Lafayette, Bader wanted to be sure he could obtain a steady supply of the perfume from the Beaux laboratory—and in quantities to satisfy his customers. “You have a perfume that deserves a much bigger market. I want you to meet Pierre Wertheimer, who owns Bourjois perfumes and has a large factory in France and an important distribution network,” he advised Chanel. (It is unknown if Bader revealed to Chanel that the Wertheimers were his business partners.)

Chanel’s Longchamp meeting with Pierre Wertheimer was by all accounts short and to the point: “You want to produce and distribute perfumes for me?”

“Why not?” he replied. “But if you want the perfume to be made under the name of Chanel, we’ve got to incorporate.”

Within the time it took to complete the legal work, Chanel turned over to a newly formed French company Les Parfums Chanel, S.A. the ownership and rights to manufacture Chanel perfumes along with the formulas and methods to produce the fragrances developed by Beaux. In return, she became president of the new entity and held a stake of two hundred fully paid-up shares—worth 500 French francs each. Her ownership represented 10 percent of the paid-up capital. She was also granted 10 percent of the capital of all companies that manufactured her perfumes outside of France. The majority of the remaining capital, 70 percent of the outstanding shares, went to the Wertheimer clan, who would finance production and assure worldwide distribution of the perfume from their corporate headquarters in New York. Bader’s proxies (Adolphe Dreyfus and Max Grumbach) received 20 percent of the shares. One wonders if Chanel knew that Bader was in effect getting a kind of finder’s fee through these intermediaries.

Pierre Wertheimer, the younger Wertheimer brother, 1928. The Wertheimers bought a majority of Chanel’s perfume company in 1924. (illustration credit 2.10)

Chanel’s nonchalance in reaching a deal with Pierre Wertheimer—and agreeing to use the same lawyer as the Wertheimers to draw up contracts—borders on commercial recklessness. It may be that after her hopeless affair with Pierre Reverdy, and having recently parted with Grand Duke Dmitri, she was just too emotionally worked up to give the matter any serious attention. Indeed, between 1923 and 1937, Chanel was “Mademoiselle Ballet,” trapped in a whirlwind of hyperactivity. She poured her creative energy into designing costumes for Sergei Diaghilev’s ballets—Le Train bleu, Orphée, Oedipe roi—and a host of other theatrical productions, many choreographed by Diaghilev with Vaslav Nijinsky. Her costumes for Le Train bleu meshed beautifully with the subtle sexual transgressions in the dance, the characters playing with gender stereotypes, androgyny, and homosexuality—though in this case, the females were endowed with masculine characteristics. The ballet was an open exploration of avant-garde perversity—and Chanel must have been delighted to be part of the production.

The poet Pierre Reverdy, 1940—a man Chanel deeply loved. Their friendship lasted more than fifty years. (illustration credit 2.11)

BY THE LATE 1920S, thanks to the production capabilities, marketing expertise, and distribution muscle of the Wertheimers, Chanel No. 5 had become a worldwide success—and nowhere more so than across the Atlantic. The perfume would become the most profitable and long-lasting result of her volcanic career, pumping out an ever-rising river of profits that would make both Chanel and the Wertheimers fabulously wealthy. But it would take a worldwide depression and later World War II for Chanel to realize the economic significance of her new perfume and the complications of her partnership with the Wertheimers. When she first signed the deal with the family, she did not and could not have imagined how Chanel No. 5 would become a fountain of riches.

And who were these Wertheimers?

France’s defeat by German armies in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–1871 split the Alsatian-Jewish Wertheimer family. Émile stayed in Alsace, now part of a united Second German Reich, while Julien and Ernest Wertheimer opted, as did some 15 percent of Alsatians, for French nationality. But it was brother Ernest who had the “nose.” In 1898 he established E. Wertheimer & Cie. and, with Julien at his side, acquired a majority interest in A. Bourjois & Cie., manufacturers of poudre de riz Bourjois (ladies’ powder), soap, and other beauty products distributed worldwide. They also acquired a production facility at Pantin, close to the Paris slaughterhouses of La Villette, known as “the city of blood.” Ironically, during the Nazi occupation of Paris, it was from the Pantin rail yards that French and German police deported uncounted thousands of men, women, and children to Germany and to certain death.

Soon the brothers joined with other French Jews to invest in Galeries Lafayette, a large department store that would be run with great success by Théophile Bader, first on Paris’s boulevard Haussmann and later in other locations throughout France. On the shelves of the Galeries, Bourjois products for ladies and men found a warm welcome.

Chanel was not an astute businesswoman. The whole idea of commerce, contracts, and paperwork “bored her to death.” For her entire life, she would have a love-hate, chaotic relationship with the shrewd businessman Pierre Wertheimer. She would come to believe that she had been exploited, lamenting, “He screwed me”—yet in a typical Chanel whisper, she would add, “that darling Pierre.” Indeed, four years after inking the agreement with the temperamental couturier, the Wertheimers engaged a lawyer to deal with her while they kept an arm’s-length relationship.

Still, the impoverished pupil of the sisters of the Congregation of the Sacred Heart mined a seam of gold in forty-one-year-old Paul and thirty-six-year-old Pierre Wertheimer. Between 1905 and 1920 the brothers had established some one hundred distribution arrangements for their products worldwide.

WHILE ENJOYING her new fame and wealth, Chanel had yet to be accepted by the very top tier of French society; she had yet to be “anointed” by English “royals.” She was still an individual whose sexual promiscuity placed her outside of respectable society—despite her having “revolutionized French fashion” since 1910. Her amorous pursuits didn’t bother Pierre Wertheimer. He knew all about the gossip that swirled around her. In fact, Pierre had a crush on Gabrielle Chanel—still irresistible at forty-four and looking ten years younger. Despite their future quarrels, legal battles, and problems, Pierre would remain enamored of Chanel for the rest of his life. In the end, he would be her savior.

FOR THE HOLIDAY SEASON of 1924–1925, Chanel drove down to Monte Carlo with Sarah Gertrude Arkwright Bate. Sarah, whom everyone called Vera, had been abandoned by her mother and became the surrogate child of Margaret Cambridge, Marchioness of Cambridge, daughter of the Duke of Westminster, and related to King Edward VII and Sir Winston Churchill. Vera thus acquired from childhood solid ties with the British royal family. Her good looks, luminous skin, statuesque figure, and English connections attracted Chanel. No one was more keenly appreciated by London high society … As a young woman Vera enjoyed a host of suitors: a stream of Archies, Harolds, Winstons, and Duffs at her side. Chanel hired this thirty-five-year-old darling of English royals to handle public relations in London and Paris society for the House of Chanel.

THE CÔTE D’AZUR was an animated, bubbling place to celebrate the holiday season and the New Year. Wealthy Continentals rubbed elbows with the English elite—the Churchills and the Grosvenors, who in the 1920s boom enjoyed unheard of luxury at the watering holes of Monte Carlo, Deauville, and Biarritz in France. The Wertheimers, Pierre and Paul, preferred the racecourses of Tremblay, Ascot, and Longchamp. It had been a bonanza year for the brothers: their investment in Félix Amiot paid off when the French government nationalized Amiot’s firm, earning the Wertheimers an unexpected windfall profit of 14 million francs. (Prophetically, Amiot, a future business partner, would protect the Wertheimer fortune in the bad days ahead.)

A year before, in 1923, Adolf Hitler organized the Munich Beer Hall Putsch. When it failed, Hitler was arrested, tried, convicted of high treason, and sentenced to serve five years’ imprisonment with eligibility for parole in nine months.

In cell 7 of the Landsberg Prison fortress, Hitler dictated a part-biographical, part-political treatise to his acolytes. Mein Kampf (although often translated as “My Struggle” or “My Campaign,” its meaning could also be conveyed as “My Fight”) told of Hitler’s “Four and a Half Years [of Fighting] Against Lies, Stupidity and Cowardice.” Released in early 1925, the first volume, a bible for the NSPD, laid out the Nazi creed of nationalism, anti-Semitism, and anti-Communism. That same year Hitler reorganized the Nazi party; his often-brilliant oratory began exciting millions of Germans and Austrians—including many disaffected World War I veterans.

A few months later, Joseph Goebbels was appointed Nazi district leader of Berlin. As France and Britain celebrated joyfully the Christmas season of 1924, chaos and hyperinflation was devouring the social fabric of the Reich. Riots swept the country as people’s savings were wiped out. In 1919 a U.S. dollar bought 5.20 German marks. By December 1924 the U.S. dollar fetched 4.2 trillion German marks. A loaf of bread in 1924 was now priced, unbelievably, at 429 billion marks. A kilo of fresh butter cost 6 trillion marks. Pensions became meaningless. People began demanding to be paid daily so they wouldn’t see their wages devalued by a passing day. Thousands became homeless and German culture collapsed, destroying the German middle class.