“Struggling with the devil … who wears the deceitful face of hope and despair.”

—T. S. ELIOT, “ASH WEDNESDAY”

RETURNING FROM HOLLYWOOD, Chanel craved an immediate change of scenery and went to London for “a bath of nobility.” Bendor, still under her spell, lent Chanel, rent free, a nine-bedroom eighteenth-century house with ornate plaster ceilings, cornices, and pine paneling at 9 Audley Street to be the headquarters for her growing business in the United Kingdom. He spent more than £8,000 to redecorate the house to her taste, and lent her 39 Grosvenor Square for an exhibition of her designs to raise money for the Royal British Legion. Five to six hundred people came every day to see Chanel’s dresses, even though none were for sale. She was welcomed by the Churchills, including debonair young Randolph, who escorted her to the opening of the Legion’s exhibition.

Chanel was beginning to show her age. Her face had hardened, her neck was taut; overwork and incessant Camel cigarettes along with middle age left their mark. Vain and slightly cross-eyed, she refused to wear glasses in public. (In a rare photograph by Roger Shall, we see Chanel wearing spectacles while watching one of her fashion shows from the steps of rue Cambon, sometime in the 1930s.) Yet fashion icon Diana Vreeland thought Chanel in the 1930s was “bright, a dark golden color—wide face with a snorting nose, just like a little bull, and deep Dubonnet red cheeks.” No matter her looks, Chanel was now a queen enjoying her power; aggressive in speech, chattering, and scoffing: “I am timid. Timid people talk a great deal because they can’t stand silence. I am always ready to bring out any idiocy at all just to fill up silence. I go on, I go on from one thing to another so that there will be no chance for silence. I talk vehemently. I know I can be unbearable.”

Age had not weakened Chanel’s taste for making money. In 1931, Janet Flanner wrote in a New Yorker profile how “each year [Chanel] tries not only to beat her competitors but to beat herself … Her last annual chiffre d’affaires [turnover] was publicly quoted [not by her] as being one hundred and twenty million Francs, or close to four and a half million dollars” ($60 million now). Flanner’s reporting encountered obstacles: “Because she sensibly never talks, never gives interviews, or admits anything, and because she cannily distributes her money in a variety of banks in several countries, it is impossible accurately to approximate the fortune Chanel has amassed. But London City rumors it at some three millions of pounds [around $230 million in today’s money] which in France, and for a woman, is enormous.”

More definite figures lacking, perhaps the closest estimate of her financial genius is contained in a statement accredited to the banking house of Rothschild, a European establishment discerning enough to have made a fortune even out of the battle of Waterloo. “Mademoiselle Chanel,” they are reported as solemnly saying, “knows how to make a safe twenty-percent.”

CHANEL COULDN’T COUNT without using her fingers, but she was sure the Wertheimer brothers were cheating her out of her share of profits from the sale of her perfumes. She increasingly resented the deal she had made in 1924, when the Wertheimers took control of Société des Parfums Chanel—the company that owned her fragrance and cosmetic businesses. For the next twenty-five or so years her litany became: “I signed something in 1924. I let myself be swindled.” Her accountants tried to assure her that the accounts of Société des Parfums Chanel were in order and that the penury of dividends was not due to chicanery but rather to the massive investment necessary to make Chanel No. 5 a world brand. But she was convinced that she was being robbed by pirates—Jewish pirates.

Suzanne and Otto Abetz with René de Chambrun (in the middle), seen here walking away from a hospital in Versailles in September 1941 after visiting Pierre Laval when the minister was recovering from the attempt on his life. (illustration credit 5.1)

She hired a young French-American attorney, René de Chambrun, to fight the Wertheimers. A direct descendant of the Lafayette family, Chambrun had dual U.S.-French citizenship. In 1930, Chanel asked him to initiate a series of lawsuits aimed at harassing the Wertheimers—a feeble effort to regain control of the company. The trials would drag on for years, and Chanel would lose. Chambrun would be her friend and attorney for the next fifteen years and throughout World War II. An accused Nazi collaborator, Chambrun would play a major role in Chanel’s wartime adventures during the German occupation.

CHANEL’S CREATIVITY never waned. She abandoned the tweeds, the sportswear, and the garçonne look, championing feminine dresses for afternoon wear. She appeared at her sumptuous evening parties in vaporous combinations of tulle and lace. Despite the world economic crisis, Chanel launched a collection of costume jewelry inspired by Bendor’s gifts of real jewels. It was a tribute to her ingenuity, the good taste of Étienne de Beaumont, Count Fulco della Verdura, and Parisian artisans she hired. Years earlier, Beaumont, a French aristocrat of the highest order, had invited her to come to his opulent Paris soirees, but some of the high-society women in attendance had slighted her. Later, she told the painter Marie Laurencin: “All those bluebloods, they turned their noses up at me, but I’ll have them groveling at my feet.” In fact, while ridiculing these women, she envied them.

Beaumont and Fulco della Verdura soon launched a line of dazzling Chanel costume jewelry. Out of the vault came some of her lovers’ glittering gifts. The gems were removed from their settings and used to design a line of Chanel jewelry, including a copy of a Russian antique necklace with multiple strands of pearls set off with a rhinestone star medallion; clusters of sapphire-blue glass and turquoise studs attached to gold metallic chains; an enamel cuff in black or white studded with glass stones; and an Indian bib of red beehives, green glass balls, green leaves, and pearls imitating the rare rubies and emeralds of a Bendor gift. The line was a smashing success. Chanel now instructed wealthy society women: “It’s disgusting to walk around with millions around the neck because one happens to be rich. I only like fake jewelry … because it’s provocative.” When the costume jewelry sold well, she brought out a line of real jewels in diamonds, diamond broaches, necklaces, bracelets, and hair clips.

ADOLF HITLER, founder and leader of Germany’s Nazi Party, became German chancellor in January 1933. He moved swiftly to consolidate his power, to become “dictator” in March of that year, and to fill key posts with devoted Nazi Party followers. Hermann Göring, on the führer’s orders, created a Nazi secret police, the Gestapo, and later a modern German air force, the Luftwaffe. Germany’s next most powerful man was a thirty-six-year-old “relentless Jew baiter and burner of books” Joseph Goebbels—the master propagandist for the Nazi Party. Goebbels now became the Reich Minister for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda, giving one man control of the communications media: radio, press, publishing, cinema, and other arts.

In early 1935, Hitler appointed Admiral Wilhelm Canaris to head the Abwehr, the German military espionage service. Canaris cooperated with his Nazi bosses—proposing that Jews be forced to wear a yellow star as a means of identification. Later, Himmler’s SS organization under Walter Schellenberg swallowed the Abwehr.

One of the first appointments Goebbels made was to name Abwehr master spy Baron Hans Günther von Dincklage as a “special attaché” at the German Embassy in Paris. Operating under diplomatic immunity, Dincklage set about building a Nazi propaganda and espionage network in France. He would retain his diplomatic status until after World War II.

The French intelligence and police establishments knew about Dincklage and had been collecting information since 1919 about his work as Abwehr agent F-8680, operating on the Riviera since 1929. Their reports told of how Dincklage, returning from Warsaw, Poland, joined Catsy to employ their good looks and charm in recruiting new agents to penetrate the French naval establishment at Toulon, France, and Bizerte, Tunisia. By 1932 the Dincklages were settled at “La Petite Casa” in Sanary-sur-Mer.

Writing about Dincklage’s power of attraction, Catsy’s half sister Sybille Bedford ventured, “Spatz Dincklage’s secret charm appeared nonchalant … and he had a beauty that pleased both women and men.” Catsy soon seduced Spatz’s tennis partner, French naval officer Charles Coton, into a long-term intimate relationship. Later she would set her sights on French naval engineer Pierre Gaillard, who spied for the Dincklages at the strategic French naval base at Cap Blanc, Bizerte, Tunisia. The two naval officers became the backbone of the Dincklage espionage network in the Mediterranean, and Coton became the Dincklages’ secret courier between Sanary-sur-Mer, Toulon, and Paris.

WITH HITLER INSTALLED as Reich chancellor, Dincklage took up official duties at the German Embassy in October 1933—he was now driving a gray two-seater Chrysler roadster, and he and Catsy were settled in an apartment in one of Paris’s chic neighborhoods. It was a new adventure for Dincklage. He now had offices at the German Embassy on the rue Huysmans. Under diplomatic cover, Dincklage went about building a black propaganda campaign and espionage operation financed by Berlin. The embassy provided direct and protected communication to and from his masters in Berlin, and the diplomatic courier service handled the voluminous reports and news clippings that all spies must pouch to headquarters. It didn’t take long for the Dincklages to settle in. Within weeks of arriving in Paris, two Berlin moving vans delivered furniture to an apartment. Their German maid (an Abwehr-trained agent), Lucie Braun, joined the couple. She was issued a French identity card stating that she worked for an accredited diplomat at the German Embassy.

A handsome Baron von Dincklage, ca. 1935, at the German Embassy in Paris when he worked with the Gestapo. (illustration credit 5.2)

French police and military intelligence observed the Dincklages’ new lifestyle: two apartments located in very chic and expensive sections of Paris—hardly affordable to the Austrian refugee that Dincklage sometimes claimed to be. In 1934 the Sûreté of the Ministry of the Interior labeled Dincklage a Nazi propagandist with agents buried in the German office of tourism (located on the avenue de l’Opéra). Dincklage had also planted German engineers as technicians in French factories in Paris suburbs to collect industrial intelligence.

By 1934 the Berlin Nazi machine issued orders to have Abwehr units work hand in hand with the Gestapo and the SS. Abwehr agents, like the Dincklages, were commanded to maintain close relations with all Nazi organizations involved in espionage and counterespionage. In a final order, demanding cooperation between Hitler’s police and intelligence services, Abwehr agents were told to recruit and train individuals who would collaborate with the Gestapo in espionage activities. As part of this consolidation, German citizens of the Reich living overseas were commanded by Berlin and local consulates to join Nazi cells. In Paris, Dincklage, now labeled by French police as “directing a German police service,” was also involved with the first Nazi cell in France. His group met every week at 9 p.m. at 53, boulevard Malesherbes. In 1934 the Dincklages’ maid, Lucie Braun, was listed as the 239th member of the Paris cell, among 441 members.

The French military counterintelligence service (Deuxième Bureau) had by now accumulated a background file on Dincklage and his wife. The agency was informed of the couple’s living habits and operations in Paris and at Sanary-sur-Mer. “Dincklage’s wife, Maximiliane, [was] the daughter of ex-Colonel of German cavalry von Schoenebeck and Melanie Herz. The couple lived at 64, rue Pergolèse, rented for 18,000 Francs a month [the equivalent of $19,000 in 2010].” The report supplies endless detail: “Dincklage is traveling continually; his wife is often in Sanary at the villa La Petite Casa. In Paris the couple is visited at all hours of the day and night by Charles Coton and Georges Gaillard” as the Dincklages “continually seek out the company of French naval officers.”

French authorities now decided to damage the Dincklage operations. Rather than outraging Hitler by expelling a German couple with diplomatic accreditation on grounds of espionage, French counterintelligence turned to the press. On November 27, 1934, Inter Press (a newswire service) issued a startling report about Dincklage and his underground network. The story was released about the same time Winston Churchill was warning the British Parliament about the “menace” of Hermann Göring’s Luftwaffe air force. The Inter Press dispatch revealed how: “Baron von Dincklage, Hitler’s agent in Paris, has been replaced … he was denounced in his own embassy as a member of the Hitler secret police … now he is involved in special missions in Tunisia—then under French mandate. One of Dincklage’s close friends (Charles Coton) is an administrator of a French naval unit stationed at the French naval base at Bizerte, Tunisia. Coton comes frequently to Paris. On the 16–17 November [1934] Coton came to the Dincklage apartment with three suitcases which he claimed belonged to the Dincklage couple … Then a few days later the Vietnamese valet of the Dincklages’ friend Georges Gaillard came to the Dincklage apartment with a box of keys to open the suitcases; when the Dincklages returned to their apartment they took two of the suitcases away—[they may have then traveled to London].” It turned out that French official Pierre Gaillard was one of Maximiliane’s lovers. The report named other members of the Dincklage espionage network in France: Madame Christa von Bodenhausen (her lover was a French naval officer); German newsman Hanck; and Krug von Nidda, a notorious Nazi and later German ambassador at Vichy during the occupation. Ernest Dehnicks of the German Consulate General was also a Dincklage agent. Finally, the report confirmed “the German tourist office at 50, avenue de l’Opéra, Paris is suspected of acting against the national interest”—a French government euphemism for spying.

IN 1934 Chanel moved into a suite at the Ritz with a wood-burning fireplace and an austere bedroom. The Ritz was synonymous with good taste, refinement, and comfort, and renowned for offering a fine menu of French haute cuisine. Chanel’s Ritz apartment overlooked the Place Vendôme, around the corner from the rue Cambon, where she created a four-room apartment above her workrooms. The space was decorated with objects and furniture she treasured: the Coromandel screens from Boy Capel, crystal chandeliers, Oriental tables, and a pair of bronze animals. From the Ritz’s back entrance Chanel could cross the street to her salon and apartment, which allowed her to avoid the despised Schiaparelli’s boutique on the Place Vendôme.

Chanel was in love with a dark, handsome Basque: the exceptionally creative illustrator and designer Paul Iribe, her same age. Born Paul Iribarnegaray, Iribe had made a hit in Hollywood directing one film and as an art director for Cecil B. DeMille. In France he was the popular illustrator of a book of erotica based on Paul Poiret’s fashions. A writer and illustrator for Vogue, a designer of fabrics, furniture, and rugs, and an interior designer for wealthy clients, Iribe attracted Chanel with his provocative wit and multiple talents.

Using Chanel’s money, Iribe revived a monthly newssheet, Le Témoin, and turned it into a violent ultranationalist weekly. According to one biographer, Iribe was an elitist bourgeois supercharged with an irrational fear of foreigners. Reading his issues of Le Témoin, one would think France was the eternal victim of some vast international conspiracy. The magazine was a timid echo of France’s Fascist and anti-Semitic press, publications that supported French storm troopers named the “hooded ones”—La Cagoule—and groups promoting law and order in Italy and Germany. Biographer Charles-Roux believed Chanel’s launching of Le Témoin with Iribe as editor and art director marked her transition from political indifference to a view of the future modeled on the opinions of Iribe—mixed in with ideas and prejudices absorbed during her peasant and Catholic upbringing. In the February 24, 1933, edition of the magazine, Iribe had the brass to draw Chanel as a martyred Marianne in her Phrygian bonnet—her naked body held by a collection of evil-looking men with obvious Jewish features. France, according to Iribe in Le Témoin, was suffering from a conspiracy managed by “enemies within” called “Samuel,” or “Levy,” the “alien” like Léon Blum, and “Judeo-Masonic Mafia,” the USSR, and “red rabbles.” His extreme political views aside, however, Iribe’s artwork in Le Témoin was breathtaking.

No man before Iribe had raised Chanel’s political awareness, and she brought him into her professional life to share the power she had always guarded assiduously for herself. Chanel was once again “happy” and in love. Iribe had become her confidential agent, her “knight,” and Chanel asked him to work in conjunction with René de Chambrun on the Wertheimer case. Rumors of a marriage swirled about the city.

In August 1935, Chanel and Iribe invited a houseful of guests to La Pausa. Photographs of the event show a glorious summer afternoon, one of those golden days on the Riviera when a light breeze from the hills above joined with the salt air of the Mediterranean to create an intoxicating atmosphere. Chanel’s guests that afternoon looked as if they had stepped out of a sketch printed in a fashion magazine featuring her summer modes: espadrilles, a French sailor’s horizontally striped T-shirt, and casual pants made of jersey fabrics—an idea borrowed from the Duke of Westminster’s crew on the Flying Cloud. Iribe, whom French writer Colette depicted as a “very interesting demon,” arrived at La Pausa from Paris.

With Hitler in power, violent Nazi persecutions of Jews raged in Germany. In 1935 the anti-Semitic Paul Iribe, Chanel’s lover, published in Le Témoin this prostrate Marianne (representing France) with Chanel’s features. Hitler holds Chanel (searching for a heartbeat) as men and a woman with Jewish traits look on. The caption reads: “Wait, she still lives.” The publication, edited by Iribe, was financed by Chanel. (illustration credit 5.3)

The next day—a splendid September afternoon—Chanel relaxed in the shadows of an ancient olive tree, its green leaves ruffled by a breeze. She watched Paul Iribe play an informal match on her tennis court, delighting in her lover’s athletic prowess. Her Great Dane, Gigot, lolled beside her. Suddenly, Chanel’s world came crashing down. Suddenly, Iribe collapsed on the court before her eyes, his face ashen. Later, horrified, she watched stretcher bearers carry his body away. Paul Iribe, another “man of her life” whom the gossip columnists were sure would wed Chanel, was dead. She was “devastated.”

A long winter of grief followed. From that moment on and until the end of her life, Chanel injected herself with a dose of morphine-based sedol before going to bed. “I need it to hold on,” she would say. As she had after Boy Capel’s death, she sank into a void, using the sedative to calm her nerves.

Chanel’s grand-niece, Gabrielle Palasse Labrunie, remembers a song her aunt repeatedly sang in heavily accented English during one summer’s visit to La Pausa. The words were, “My baby has a heart of stone … not human, but she’s my own … To the day I die I’ll be loving my woman.” Madame Labrunie thought the sad poetry was a cameo of Chanel’s life.

Coco had lost her drive and energy. Without Iribe, she had no emotional attachment; she was entering her years of discontent. She longed to get away from the Parisian carousel. In London, always a refuge, she attended the Royal Ascot annual race with Randolph Churchill. The London Daily Mail quoted her: “Your Queen succeeds in a very difficult task. In an age where successive bizarre and extravagant fashions—not always in perfect taste—are sweeping the world, she maintains a queenly grace and distinction which are conservative without being old-fashioned.”

BY THE SUMMER OF 1934, Hitler’s campaign of terror seemed to know no end. In Austria, Nazis had murdered Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss; in Berlin and Bavaria, Hitler personally supervised the murder of Ernst Röhm’s Brown Shirt thugs—now his political opponents. To celebrate his gaining total power, Hitler’s organizers brought two hundred thousand party officials with twenty-one thousand flags to a packed Nuremberg Nazi rally. A frenzied crowd heard their führer shout, “We are strong and will get stronger.”

That same year, Hitler turned his attention to the anti-Nazi, Swiss-educated, liberal king of Yugoslavia, Alexander—a staunch ally of France and a thorn in Hitler’s grand plan for Europe. In the summer of 1934, Dincklage traveled to Yugoslavia. He was tracked by the French Deuxième Bureau to the capital city of Belgrade, barely three months before a Bulgarian nationalist shot King Alexander dead as he landed at Marseille port to begin a state visit to France. French intelligence agents then revealed: “Dincklage … former attaché at German Embassy Paris was this summer in Yugoslavia for business.” Dincklage wrote his former Paris Embassy colleagues, “Business in Yugoslavia is tough like everywhere else.”

Three months later, André François-Poncet, French ambassador to Berlin, wrote to Sir Eric Phipps at the British Embassy in Berlin: “The Germans are by no means as innocent in this assassination business as they would have us believe” and that Göring was somehow involved while he was visiting Belgrade.

In March 1935, Hitler brushed aside the Versailles Treaty. Repudiating it two years later, he ordered compulsory military services—trebling the numerical strength of the German military machine. French intelligence services now received permission to strike at the growing German espionage and black propaganda operation, which was spreading false and deceiving information in France. Dincklage was singled out as the principal target.

“Gestapo über alles” (Gestapo above all) were the words used for a dramatic headline in the September 4, 1935, issue of the Paris weekly Vendémiaire. The exposé (obviously the work of French counterintelligence) was spread over three columns. An additional long report followed in the September 11 issue of the paper. Both stories featured Dincklage’s work as a Gestapo agent (at the time, the French did not differentiate between Abwehr and Gestapo) and as a special attaché at the German Embassy. In five thousand words, Vendémiaire unmasked the work of Nazi and Gestapo agents in France. The editors revealed that Dincklage was a Gestapo officer somehow linked to the assassination of King Alexander of Yugoslavia and that he had visited the Berlin Gestapo in September 1934 and delivered to “a Gestapo officer named Diehls a list containing the addresses of German exiles in France.” Further, he had offered to provide the Nazis lists of former German Communists in France. Later, it was revealed that Rudolph Diehls was a close friend of Hermann Göring, who appointed him to a high Nazi post after he was dismissed as head of the Gestapo and replaced by Himmler.

The newspaper story is a close copy of an October 1934 report authored by French Army Headquarters. It notes that Dincklage received 100,000 francs a month (equivalent to about $105,000 today) to finance “his corrupt activities.” Vendémiaire went on to document Dincklage’s movements as a German agent on special missions to the Côte d’Azur, in Paris, and in the Balkans. In a mission to Tunis, Dincklage employed dissident Muslims to launch a violent propaganda attack on the French colonial regime.

As France was preparing for war with Germany, French authorities—most likely the Deuxième Bureau—allowed author Paul Allard to publish almost the same story as the one that appeared in the weekly Vendémiaire. Allard’s postwar book, How Hitler Spied on France, told how Goebbels’s propaganda agent in Paris, Dincklage, urged his Berlin masters to supply him with favorable anecdotes about the domestic life of the families of SS officers. Dincklage explained to his bosses that the stories could be placed in French publications sympathetic to the Nazis.

DURING HITLER’S 1935 NUREMBERG RALLY, the Nazis enacted the Nuremberg Laws, a series of laws aimed at Jews. Overnight, Maximiliane von Dincklage, now considered a Jew under Nazi law, was deprived of her citizenship. It was the fulfillment of Nazi racial philosopher Alfred Rosenberg’s wish that Germany’s “master race,” which he labeled as a homogeneous Aryan-Nordic civilization, be protected against supposed “racial threats” from the “Jewish-Semitic race.” Among other things, the law prohibited marriage between Jews and Aryans. Dincklage must have known the decree was imminent. Three months earlier he had divorced his wife of fifteen years at Düsseldorf.

The newly single Dincklage spent the summer near Toulon in the apartment of his English mistress and her sister. With the release of the Vendémiaire news articles, Dincklage hurriedly moved to London. There, in a temporary haven at a Mayfair Court apartment on Strasson Street, he wrote to the German ambassador in Paris. The letter makes a feeble attempt to get the ambassador to protest to French authorities about the publication of the Vendémiaire series. His appeal didn’t work, and the ambassador asked his aide-de-camp to reply to his former attaché. Here are excerpts from the exchange of letters:

To the Honorable Ambassador,

I have just now obtained from a French business … the Vendemiaire 4. Sept. 35. In my estimation, the author of the enclosed document … must certainly be paid by anti-German sources … The day before the assassination of the King of Yugoslavia [I was] in Tunis … [you] must write … the authorities that [the information is presented] is untrue and completely unfounded. I am currently in the process of building a … [illegible] and this announcement could be a disadvantage to me. I faithfully request that Herr Koester … [tell] the French authorities in a truthful manner [in order] to clarify the errors … Much of my work, my many trips to France, and … my time at the embassy … have produced … good results for Germany and France. I express my respect and high regard, Mr. Ambassador, and remain your loyal …

[signed] Dincklage

The German Embassy in Paris responded:

Paris, the 13 September 1935

Dear Mr. Dincklage,

The Ambassador instructed me to thank you for your kind words. He doesn’t believe an intervention in the matter which you explained is currently [illegible]: the rumors that were spreading earlier have abated, and undertaking measures to correct the rumors, whether in Quai d’Orsay [location of the French Foreign Ministry] or among the local press, would only cause old legends to take on new meanings and concern to spread. However, should the rumors emerge again[,] the Ambassador will take the opportunity to raise the issue of your concerns with the local foreign office.

With many greetings I am, Ever your loyal correspondent.

[signed] Fühn

PRIOR TO DINCKLAGE’S DEPARTURE for England, a 1935 secret Deuxième Bureau report revealed how his maid, a member of a Nazi cell in Paris, was now operating from the Dincklage base in Sanary-sur-Mer: “A woman whom Dincklage claims to be his secretary named Lucie Braun, also of the personnel of the German Embassy in Paris … [is] suspected of working against the national interest.” The bureau believed that prior to Dincklage’s departure for London, Lucie Braun lived near Toulon at Sanary where there was a large German community. The report adds that on February 9, 1935, Dincklage was visited by his seventy-two-year-old uncle William Kutter, a rear admiral of the German navy living at Darmstadt. Kutter arrived directly from Strasbourg (France) and remained in Sanary at La Petite Casa until the end of February 1935. The admiral was questioned at the Toulon rail station as to the reason for his visit. He told French agents he had come to Toulon as a tourist, but he did not reveal he was going to the Dincklage villa at Sanary.

NEWLY REELECTED PRESIDENT Franklin Roosevelt now proclaimed American neutrality and appealed to Hitler and Mussolini to settle European problems amicably. Still, Winston Churchill found time to cable Chanel. On December 2, 1935, he wrote from London: “I fear I shall not be an evening in Paris when I pass through on the 10th of December, but I shall be returning towards the end of January, and look forward indeed to seeing you then. I will give you two or three days notice by telegram from Majorca where I propose to winter. How delightful to see you again. Herewith my debt.”

There is no explanation of Churchill’s reference to “my debt.” However, it is doubtful that he ever went to Majorca that winter of 1935. In the coming months Churchill would become embroiled in the political fortunes of Great Britain. With the death of King George V of England, his son Edward, Churchill’s close friend, succeeded to the throne. Churchill would expend great political capital trying to protect his sovereign and close friend from the wrath of the British parliament, which opposed Edward’s plan to marry the American divorcée Mrs. Wallis Simpson.

AS THE GERMAN GENERAL STAFF was hard at work on a plan to invade France, including the seizure of parts of North Africa, Dincklage was organizing an espionage network at French naval bases in Tunisia and a black propaganda operation among the North African Muslims. His former agent in Toulon, Charles Coton, had already left Sanary for an assignment at the French naval base at Bizerte, where he would again act as Dincklage’s principal agent.

French authorities were eager to expel Dincklage. A 1938 Deuxième Bureau report tells, “Since leaving the German Embassy [Dincklage] has been active in anti-French propaganda in North Africa. He has been on missions to North Africa [including] Tunisia—[but] after close surveillance Dincklage has not committed a punishable crime; he is, however, a dangerous subject.”

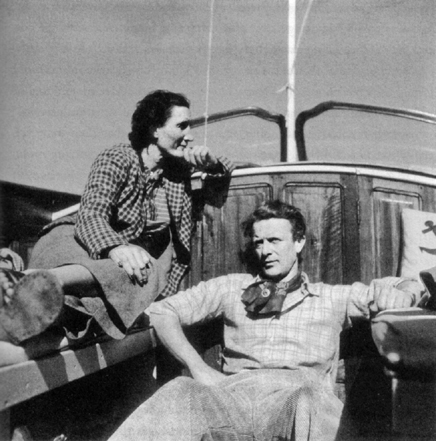

“Spatz” von Dincklage and Hélène Dessoffy, his lover, on a small boat off the French Riviera about 1938. Dessoffy was an unwitting member of Dincklage’s espionage operation at the French naval base in Toulon. (illustration credit 5.4)

By November 1938 Dincklage had taken a new lover and agent. French counterintelligence identified her as “Madame ‘Sophie’ or ‘Dessoffy’ ” (later identified as Baronne Hélène Dessoffy). A French agent in Bayonne reported, “Madame de Sophie or Dessoffy and de Dinkelake [sic] travel frequently between Paris and Toulon. She is the go-between for procuring radio sets ‘Aga Baltic’ on behalf of a certain Dinklage [sic] who is supposed to be an agent of [the company] ‘Aga Baltic’ in Toulon … The two are suspected of espionage against France.” In a report labeled “Urgent Secret,” French authorities warned all agents that “Baron Dincklage, living at villa Colibri, Antibes [one of his accommodation addresses at the time] and carrying a German diplomatic passport (000. 968 D.1880) arrived by the steamer, El Biar, at Tunis without a visa and was asked to leave the Régence [Tunisian territory] immediately. Dincklage was traveling with French Baronne Dessoffy, Hélène, born in Poitiers, 15 December 1900, domiciled at Paris, 70 avenue de Versailles … The couple is now at the Majestic Hotel in Tunis. They occupy adjoining rooms with communicating doors.” The report detailed how Dessoffy had a telephone conversation with a friend, the naval officer M. Verdaveine, stationed at the French naval base at Bizerte. Dessoffy told the man, “I want to travel in southern Tunisia.” Verdaveine then advised her not to travel—and definitely not with the German Dincklage.

Dincklage was somehow warned off. The report continues, “The couple left Tunis at 10:00 hrs on the steamer for Marseille … We have ordered the S.E.T. [unidentified French service] to determine the relations between Verdaveine and Dessoffy Hélène.”

A year before the outbreak of World War II, the French War Ministry issued a secret instruction ordering that Dincklage be put under close surveillance. The Ministry was unequivocal: “Even if no direct proof exists to indict Dincklage he should be expelled immediately from France.”

AND WHAT OF CATSY? The French reported in 1938:

Despite being separated, Dincklage and wife are on good terms with each other and he sees her in Antibes, Sanary and Toulon … Mme Dincklage [the French apparently did not know of the 1935 divorce] arrived August 9, 1938, at Antibes … she left there September 13 and returned to the villa “Huxley,” where she has stayed before. She is now the lover of Pierre Gaillard.

In 1939, the French police would report:

Baronne Dincklage, known to the Sûreté, is living at Ollioles (Var) at a property belonging to one of her friends, the Comtesse [sic] Dessoffy; also known to the Sûreté (Fichier Central: Sûreté files). Baronne Dincklage’s lover is twenty-seven-year-old Pierre Gaillard, an engineer and son of the founder and manager of a company manufacturing cable nets (used in the national defense against enemy submarines and erected at strategic points). Gaillard is presently in Oran [an important and strategic French naval base in Algeria]. Mme Dincklage often corresponds with him; and we fear that Gaillard is constantly charmed by Mme Dincklage; and may unwillingly commit an indiscretion causing harm to the nation’s defenses …,

By late 1938, Dincklage knew war with France was imminent. Still, according to his watchers: “He is seen in Toulon … and also visits the shores of Lac Leman.” (The lake borders the French city of Thonon-les-Bains. A regular boat service connects to the Swiss cities of Lausanne and Geneva and their array of banks.) “His lifestyle at Antibes is modest … [Dincklage] receives visitors day and night. Certain [guests] come by automobile; their license plates are …” Finally, French authorities ordered all agents to “watch postal, telephone and telegraph communications made by Mme Dincklage, 12, rue des Sablons, Paris and Mme la Comtesse Dessoffy de Cserneck [sic].” The Deuxième Bureau now requested the head of the Sûreté Nationale to identify the owners of the automobiles licensed in France (autos seen in front of the Dincklage home) and to do the necessary to “immediately expel Dincklage; if it is not possible to indict him for spying.” French counterintelligence services told its agents: “Baron Hans Gunther Dincklage is considered as a very dangerous agent against France” and ordered its agents to seek information about “the relations between Dessoffy and Dincklage.” Another report added a caveat: “Despite her foreign contacts [Dessoffy] is incapable of betraying France. Nevertheless, we advise French officers to exercise great discretion in their relations with the Dessoffys and the Dincklage woman.”

WORLD WAR II was weeks away when French authorities warned of the Dincklages’ clandestine intelligence work in France. The report is a summary beginning in 1931: the Dincklage couple “had divorced; and Dincklage was supplying his masters in Berlin with information about German refugees in France and intelligence on the national defense works.” Maximiliane von Dincklage “is the daughter of a German Army Colonel in the Imperial Army of the Kaiser … she supports the monarchy” (meaning, autocratic rule).

In August 1939 France mobilized for war. Dincklage fled to Switzerland. French military intelligence ordered “Baronne Dincklage confined to a fixed residence.” In December of that year, French authorities issued a mandate: “[Maximiliane von Dincklage’s] presence in France represents a danger. [Agent] 6.000 asks [Agent] 6.610 to take all measures to intern this foreigner.”

Months before the Nazi invasion of France, Catsy, along with some other Germans living in France, was interned at Gurs, a French concentration camp located in the Basses-Pyrénées.

WHEN QUESTIONED ABOUT Dincklage at the liberation of Paris, Chanel would say, “I have known him for twenty years.” It may be another Chanel exaggeration, and there is no firsthand information about when or where Chanel first met Dincklage. Her grand-niece, Gabrielle Palasse Labrunie, who knew Dincklage well, told the author that she was sure Chanel and Dincklage met in England well before the war. Some anecdotal evidence suggests the couple met in Paris when Dincklage was at the German Embassy and was known to attend evenings hosted by a number of Chanel’s acquaintances and friends, many of whom were members of a pro-German clique in Paris in the 1930s. Among them were Marie-Louise Bousquet, Baroness Philippe de Rothschild, Duchess Antoinette d’Harcourt, and Marie-Laure de Noailles. Pierre Lazareff, who wrote about Chanel and the crème of Paris society, reported that in 1933, when Dincklage arrived at the German Embassy in Paris, this clique of bluebloods had been active in a Paris-based “führer’s social brigade” sponsored by Dincklage’s close friend, the “charming blond, blue and starry eyed” Otto Abetz, who would amuse his listeners with stories of Adolf Hitler. Abetz assured his listeners that Jews were pushing France toward war, but that France need not fear aggression.

Despite Chanel’s mythmaking and her inventions about tennis-playing, English-speaking Dincklage—whom she and her biographers cast as more English than German—Chanel and her friends knew about Dincklage’s Nazi connections and his espionage work in France. It would have been impossible to miss the gossip in elite circles based on the articles in the weekly newspaper Vendémiaire, or in the 1939 Allard book.