AN EERIE SILENCE descended over the Paris Chanel had left behind. French ministries had burned their codebooks, locked their offices, and joined the stream of refugees fleeing south. Clouds of oily black smoke drifted over the slate-gray Seine; churches, monuments, and parks were deserted; cafe life was extinguished. All communications had been cut—as if some dreadful cataclysmic event had suspended life.

William C. Bullitt, the American ambassador in Paris, cabled President Franklin D. Roosevelt: “The airplane has proved to be the decisive weapon of war … the French had nothing to oppose [the Germans] but their courage … It was certain that Italy would enter the war and Marshal Philippe Pétain would do his utmost to come to terms immediately with Germany.”

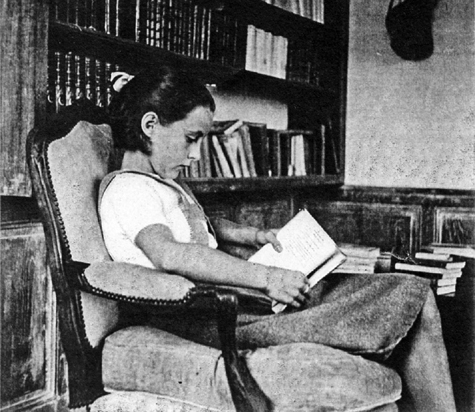

Seven weeks after German troops first entered France, the Nazi swastika flew from the Eiffel Tower. A few days later, Adolf Hitler was in Paris as his Wehrmacht troopers goose-stepped triumphantly down the Champs-Élysées. CBS correspondent William L. Shirer reported from Paris:

The streets are utterly deserted, the stores closed, the protective shutters down tight over all the windows—the emptiness of the city got to you … I have the feeling that what I have seen here is the complete breakdown of French society: a collapse of the French Army, of Government, of the morale of the people. It is almost too tremendous to believe … Petain surrendering! What does it mean? And no one appeared to have the heart for an answer.

CHANEL’S TRIP from Paris to Corbère, located near Pau, was laborious and sometimes hair-raising as her chauffeur, Larcher, drove south—inching from town to town, seeking safe passage. Hitler’s Panzer tanks were already in the French heartland, and dive-bombers strafed columns of refugees seeking shelter along the narrow tree-lined roads. The advancing German forces had forced millions of desperate citizens to take to the roads of northern France on foot in overloaded autos, trucks, and horse-drawn wagons. Their baggage, spare tires, and mattresses were piled every which way.

At Corbère, André Palasse’s wife, Katharina, and children waited anxiously for news from Auntie Coco. The family had had no information from soldier Palasse for weeks. As the tragic hours of France’s defeat slipped by, they feared the worst. For Chanel, the Palasse château would be a temporary haven, isolated in the foothills of the Pyrenees. It was near Doumy, the home of Étienne Balsan, and she could count on his help.

No one knew where the Germans would stop. French radio correspondents continued to tell how British and French troops were fleeing French soil at Dunkirk, headed for refuge in England. From Paris, CBS radio correspondent Eric Sevareid reported, “No American after tonight will be broadcasting directly to America, unless it is under supervision of men other than the French.” A French government had assembled in Bordeaux from where Prime Minister Paul Reynaud and Charles de Gaulle hoped to fight on. But they failed. Eighty-four-year-old Marshal Philippe Pétain wanted the war stopped, and Reynaud resigned. General de Gaulle fled to London. Marshal Pétain now took over what was left of France and its vast overseas empire. By mid-June 1940, the hero of the World War I battle at Verdun had asked the Germans for an armistice. Soon he would establish a regime at Vichy bent on collaboration with the Nazis. “Collaborator,” a mundane term, would become the most highly charged word in the political vocabulary of occupied France. A Time magazine correspondent observed: “The best the French could hope for was to be allowed to live in peace in Adolf Hitler’s Europe.”

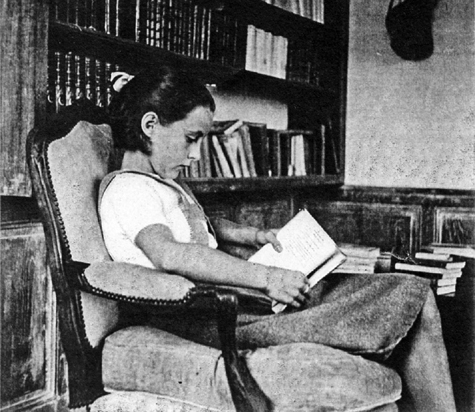

AFTER CHANEL AND LARCHER crossed the river Garonne at Agen, they found the roads less encumbered. In the foothills of the Pyrenees, at Doumy, they turned east onto country roads to find the Palasse château at Corbère. Katharina (Dutch-born Katharina Palasse, née Vanderzee), Étienne Balsan and his wife, and Chanel’s grand-nieces, fourteen-year-old Gabrielle and Hélène, twelve, were “wildly relieved” to see Chanel—their benefactor for years. Grand-niece Gabrielle was Chanel’s favorite, a vivacious child with a mind of her own. “Uncle Benny,” the Duke of Westminster, had nicknamed her “Tiny” because she was so petite. The name stuck.

The family reunion at Corbère was full of drama and pathos. News of André arrived via the International Committee of the Red Cross: he was alive, captured in one of the Maginot Line forts along with some 300,000 other French troops who had been sent to prisoner-of-war camps in Germany. The Palasse family was relieved. Surely he would be home soon, Gabrielle Palasse Labrunie remembers thinking. “The war would be over, Papa would come home.” A few days later Angèle Aubert, Manon, and some ten other Chanel employees arrived from Paris, joining a group of Chanel’s friends, all refugees from the City of Light. Later, Marie-Louise Bousquet, an intimate friend of Misia Sert, arrived from nearby Pau. Life at the château was a break from the chaos of Paris. Food was plentiful, the property’s vineyards produced delightful amber white vin du pays, and Marie, the Pal asses’ cook, served the family’s table well. From time to time a small group gathered. Katharina, Chanel, the Balsans, and Marie-Louise Bousquet dined together. The children ate earlier. Gabrielle Palasse Labrunie remembers: “At home, children were to be seen and not heard.” Madame Aubert, Manon, and the other Chanel employees lived and dined in an annex to the château. But Tiny, Chanel’s favorite, had breakfast with Auntie Coco in her room.

Chanel’s favorite grand-niece, Gabrielle Palasse, seen here at eleven or twelve years of age in the library of the Palasse home at Corbère on the eve of World War II. During the war, Mlle Palasse met Baron von Dincklage in Paris. (illustration credit 7.1)

Just after noon on June 17, French radio interrupted its usual broadcast. At the Palasse château that Monday and all over Europe and Britain, people listened as Marshal Pétain announced France was surrendering—asking Hitler for armistice terms. “You, the French people, must follow me without reservation on the paths of honor and national interest. I make a gift of myself to France to lessen her misfortune. I think of the unhappy refugees on our roads … for them I have only compassion … it is with a heavy heart that I tell you that today we must stop fighting.”

Chanel was aghast. She went to her room and wept. Gabrielle remembered, “When she learned France had been defeated, Auntie Coco was inconsolable for days. She called it a betrayal.” After the debacle of May–June 1940 and with the occupation of France it was common for French men and women to believe they were betrayed by corrupt politicians and military leaders. That feeling would give way to confidence in French hero Marshal Philippe Pétain when he took over the Vichy government.

In the weeks that followed, the family learned that General de Gaulle had made a broadcast to France from the London BBC. Slowly and often clandestinely via pamphlets distributed by anti-Nazis, French men and women heard of de Gaulle’s June 18, 1940, appeal to French citizens everywhere: “France has lost a battle but not a war. The flame of resistance must not die, will not die …” But in 1940 few in France knew who the fifty-year-old general was. Only later, through BBC broadcasts from London, would they come to know of a Free French movement headed by de Gaulle and based in London. In 1940 only a handful of French officers joined de Gaulle’s resistance movement. De Gaulle made few friends when he tagged Marshal Pétain “the shipwreck of France.” A French soldier listening to de Gaulle’s broadcast in a cafe remarked, “This guy is breaking our balls.”

André Palasse, Chanel’s nephew, in Paris before World War II. He was captured on the Maginot Line in 1940 and interned in a German stalag. Chanel managed to secure André’s freedom by cooperating with the German Abwehr spy organization. (illustration credit 7.2)

Marshal Pétain stripped General de Gaulle, his former protégé, of all rank, removing him from the rolls of the army he had served his entire adult life. De Gaulle was then sentenced to death for treason. For many French men and women the surrender was a relief; France would be spared the bloodletting of 1914–1918. With Pétain in power most French and European politicians believed “Better Hitler than Stalin”—and they hoped that Hitler would turn against the Soviet Union.

As the summer wound down, Chanel wanted to return to Paris where her perfume business needed her attention; after all, she said later, “The Germans weren’t all gangsters.”

ON JUNE 22, 1940, the Nazi propaganda machine offered radio listeners a minute-by-minute humiliating description of France’s defeat, broadcasting the details of the signing of the armistice agreement. Indeed, twenty-two years earlier, at the same railroad siding in the Compiègne forest clearing at Rethondes, the French had taken Germany’s surrender. On a breezy Saturday morning French General Charles Huntziger signed France’s capitulation in front of ranking German officers, making France a vassal of Germany. Hitler, Göring, Ribbentrop, and Rudolf Hess were there as was Dincklage’s mentor General Walther von Brauchitsch. William L. Shirer, covering the event for CBS News, told listeners in America of Hitler’s look of “scorn, anger, hate, revenge, triumph.”

In thirty-eight days, the leader of the Third Reich had achieved what the kaiser’s German army had failed to gain in the four years of bloody war in 1914–1918 that had cost millions of lives. Hitler had realized a German dream: Paris was at his feet.

After the signing of the armistice at Rethondes Hitler drove to Paris. There, the world’s newsreels captured the führer strutting up the steps of the Palais de Chaillot at the Trocadéro. The movie cameras panned slowly over the German conquests: the Eiffel Tower with its Nazi swastika floating in the breeze, the gardens of the Champ de Mars, and the nearly eight-hundred-year-old twin towers of Notre Dame Cathedral. If one could believe Nazi propaganda, Great Britain was to be next on the Reich führer’s menu.

THE ARMISTICE DIVIDED France into la zone occupée and zone non occupée (or zone libre), terms the French would soon label zone O and zone nono. France’s new masters created a line of demarcation between north and south—an absolute foreign boundary, a major barrier to the movement of people, and an impediment to business and commerce. Beginning in June 1940, French citizens would have to apply for a laissez-passer or ausweis to travel between zones. Laissez-passer were never issued automatically; they were a privilege closely supervised by the Gestapo. Even Pétain’s ministers had to ask German permission to travel from Vichy to Paris. For the French people, the line of demarcation was a humiliating nightmare.

Sixteen days after France capitulated, Prime Minister Churchill, fearing the French fleet would fall into German hands, ordered a British fleet to sink French warships based at Mers-el-Kébir in Algeria where masses of French vessels lay at anchor. Thirteen hundred French sailors perished; scores were wounded. It was a national dishonor—seen as a treacherous act by a former ally. For Marshal Pétain and his Anglophobic ministers, it was an excuse to end diplomatic relations with Britain. Pétain now declared that the nation was to have a “National Revolution” dedicated to “Work, Family and Fatherland.” Britain blockaded French ports as Hitler’s war staff planned to cross the English Channel and crush England. The Battle for Britain had begun.

Vichy, Marshal Pétain’s new headquarters, was now in the hands of men who wanted to share in a European “New Order” under Hitler. They were convinced that Germany would defeat Britain and create a powerful force against Communism and international Jewry. Soon, the Nazis forced Pétain to appoint the rabid anti-Communist and anti-Semite Pierre Laval as deputy prime minister. Barely three months after Pétain signed an armistice agreement with the Nazis, his Vichy ministers had prepared a first “Statute on Jews.” Pétain not only approved the law but in his own hand added restrictions on Jews in unoccupied France: defining who were Jews and banning Jews from high public service positions (physicians and lawyers, for example) that might influence public opinion. The Statute became law on October 3, 1940, three weeks before the Germans issued a similar law in Paris and the occupied zone. The thesis that Pétain was manipulated by his anti-Semitic Vichy entourage was a myth.

If Vichy was now the seat of French power in the unoccupied zone, Chanel wanted to go there. She was determined to return to Paris by way of Vichy. She knew Pierre Laval, now Pétain’s senior minister, through his daughter, Josée Laval de Chambrun (the wife of Chanel’s lawyer, René de Chambrun), and a handful of Vichy ministers’ wives—former clients and friends in Paris and Deauville.

Near Corbère Chanel’s chauffeur Larcher managed to find enough petrol to feed the gas-guzzling Cadillac, and what fuel the tank couldn’t hold was poured into tin cans and stored in the trunk of the car. Accompanied by Marie-Louise Bousquet, Chanel set out for Vichy. Then fourteen, Gabrielle Palasse Labrunie recalled years later and with sadness Auntie Coco’s departure in the limousine. She was struck by Marie-Louise, a chic Parisian society lady who nearly fell off her platform shoes as she walked along the château’s cobblestone courtyard to the car. It would be more than a year before Tiny would receive a pass to travel to join Chanel in Paris. The Palasse family would now live out the next months without ever seeing a German. News from André finally arrived via a Swiss Red Cross postcard: he was alive but ill.

The girls continued being tutored by Madame Lefebvre, a French refugee from the north. Their days were spent studying for the French national diploma, the brevet élémentaire. Bedtime was 8 p.m. French country people rose with the sun and went to bed early. Later, agents for the German troops, garrisoned at Pau, would come to the château to requisition foodstuffs, rabbits, pigs, and chickens.

CHANEL REACHED VICHY in late July. Her chauffeur covered the 270 miles (434 kilometers) driving over country roads along the river Allier without event. With the French surrender, the area was now occupied by German tank battalions and infantry. Refugees were returning home, and German troops had orders to be on their best behavior.

VICHY HAD ONCE BEEN a sleepy watering place on the river Allier. Until the war old men came to gamble at the casino, drink the curative waters, and ogle the pretty hostesses and buy their favors. By July when Chanel arrived, the town swarmed with some 130,000 politicians, diplomats, prostitutes, and secret agents installed in hastily built cubicles in former gambling rooms or in unheated hotel rooms transformed into offices. Their archives, brought from Paris, were stuffed into bathtubs. And everywhere the walls were graced with the likeness of Marshal Pétain, sternly glaring down at the bureaucrats at work.

When Chanel and Marie-Louise arrived, the town had the air of a tawdry commercial fair, pulsing with energy—sexual and otherwise—where life went on in cabarets, nightclubs, and brothels that served the needs of the civil servants, politicians, and professional hangers-on. A friend of Chanel’s from Paris, André-Louis Dubois, a senior French official, claimed Chanel met Misia Sert in Vichy. Dubois recalled that all three of the ladies lodged in his Vichy hotel room—and not in an attic chamber, as some of Chanel’s biographers have reported. (As it happened his rooms were free because Dubois had just been told to leave Vichy when it was discovered that he had helped Jews obtain visas to travel to America.)

At Vichy, the ladies took their meals at the Hôtel du Parc. Chanel’s biographers tell how she was shocked by the behavior of a woman dining nearby—laughing and drinking Champagne under a huge hat. For Chanel—and perhaps Misia, too—the merriment was out of place as the French mourned their defeat at the hands of their age-old enemy across the Rhine River. Chanel made a caustic remark: “Well it is the height of the season here!” Hearing this, a gentleman nearby took umbrage; he exclaimed, “What do you insinuate, Madame?” Chanel then backed away with, “I mean everyone is very gay here.” The man’s wife calmed him.

Chanel had a reason for stopping at Vichy, now the seat of French power. She was determined to move heaven and earth to get her nephew André back from captivity—if she didn’t see Laval personally, she certainly sought the advice of powerful Vichy leaders.

It must have been heartbreaking for Chanel to learn that André was only one of millions of French soldiers being held in German prisoner-of-war camps called stalags, and as early as 1940 people in the know were sure the Nazis would use those prisoners as bargaining tools. If she were to get André back, it would have to be done through a powerful German official—and she returned to Paris determined to act.

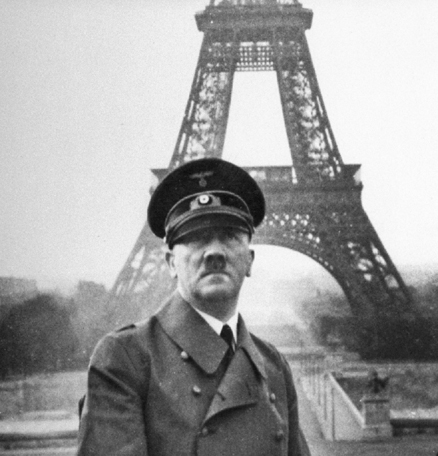

THE PARIS CHANEL returned to was awash in black-and-red swastika banners strung on the Arc de Triomphe, the Eiffel Tower, above the Parliament and ministries, and above the Élysée Palace. For the next four years Parisians would endure the sights and sounds of the German invader. Daily, Wehrmacht troopers goose-stepped to martial music down the Champs-Élysées to the Place de la Concorde. The Ritz was now a sandbagged fortress. Its entrance was guarded by elite German troopers in gray-green feld-grau uniforms presenting arms to arriving Nazi dignitaries while officers shouted lusty “Heil Hitler”s with outstretched arms.

Crueler still was the huge banner the Nazis had stuck to the upper façade of the French National Assembly and hung on the Eiffel Tower. In bold, black Gothic letters it read: Deutschland siegt an allen Fronten (Germany everywhere victorious). The Nazi masters piled insults on injuries. They ordered a bust of Adolf Hitler placed front and center of the rostrum, where the president of the French Parliament presided.

Nazi führer Adolf Hitler on his only visit to Paris after France capitulated, June 1940. (illustration credit 7.3)

To humiliate the French, the Germans raised the Nazi swastika above the building of the French Interior Ministry in occupied Paris, January 1940. (illustration credit 7.4)

Parisian streets were crowded with Wehrmacht soldiers and Kriegsmarine sailors. They strolled along the Champs-Élysées, the rue de Rivoli, and rue Royale, gawking in shop windows at luxury goods that they had never seen in their lives. They snatched up souvenirs, paid in French francs bought with inflated reichsmarks. “Thanks to the artificial exchange rate everything was cheaper for the invader.” Formally correct, they would mumble a polite “danke schön, Fräulein” to the shop tenders and wink at passing demoiselles—some all too ready to flirt with the handsome Aryan lads homesick and desperate for female company.

By the autumn of 1940 some 300,000 German officials and soldiers occupied Paris and towns around the city. They took over villas and apartments, evicting French tenants and owners, opened their own whorehouses, and earmarked their preferred hotels, restaurants, and cafes. Most Parisians came to terms with the occupation. Many would hang Pétain’s portrait on the walls of their offices and homes. The Germans owned France: the grand boulevards, the monuments, even the street kiosks on the city’s corners were festooned with Nazi signage and posters, warning the locals in German and French to obey occupation edicts, rationing laws, and the rigorous curfews—or face punishment.

Everywhere, Mercedes saloon cars, bumper pennants flapping in the wind, and camouflaged Wehrmacht squad cars scooted about the nearly empty city streets. Nonofficial Parisians put their automobiles in storage, as rationing made it impossible to get fuel, whether to heat homes or drive cars.

A gathering of German officers, possibly at the Paris Opéra ca. 1940, shows a man who may be Dincklage (top row, second from the left) dressed as a Wehrmacht officer. (illustration credit 7.5)

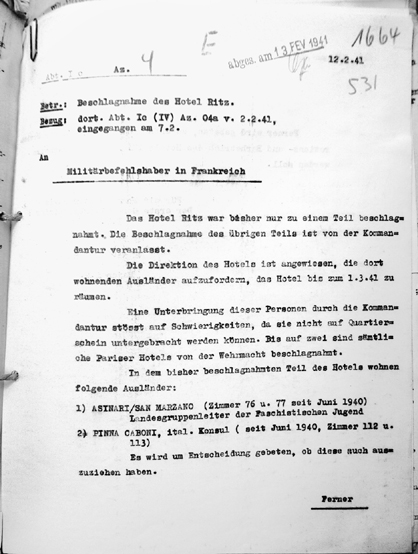

Correspondence from German Military Headquarters, Paris, stating the Hôtel Ritz was reserved for senior German officials. Among the foreigners allowed to reside there is “Chanel Melle.” (illustration credit 7.6)

FOR DINCKLAGE, a German cavalry officer at age seventeen, a veteran of the bloody campaigns on the World War I Russian front, and a German military intelligence officer for over twenty years, World War II was the realization of the German dream for lebensraum—“the space Germany was entitled to by the laws of history … [which] space would have to be taken from others.”

On a crisp fall morning in 1940 bystanders on the avenue Kléber might have noticed how a German Mercedes military staff car abruptly pulled to the curb. A German officer exited and hailed an old friend he had seen walking along the chic avenue. The uniformed German was forty-four-year-old Baron Hans Günther von Dincklage. He rushed to greet Madame Tatiana du Plessix, who with her husband had known Dincklage from his days on the Côte d’Azur and at the German Embassy in Warsaw. In that split second, Madame du Plessix discovered that the friendly Spatz was not the broken-down journalist he had pretended to be after he left Poland, but a seasoned German intelligence officer.

A list of the few civilian occupants the Nazis allowed to room at the Hôtel Ritz. Chanel’s name, room 227–228 is on line two: CHANEL Melle, (FRANZ.) 227.228. (illustration credit 7.7)

Spatz’s presence startled Tatiana. “What are you doing here?” she asked.

“I am doing my work,” he answered.

“And what is the nature of your work now?” Tatiana snapped.

“I’m in army intelligence.”

“Tu es un vrai salaud [you are a real bastard]!” Tatiana burst out. “You posed as a down-and-out journalist; you won all our sympathy, you seduced my best friend, and now you tell me you were spying on us all the time!”

“À la guerre comme à la guerre,” Spatz answered, and proceeded to ask her to dinner.

“I was vaguely tempted to accept,” Tatiana admitted later. She added, “He had posed as a victim of Hitler’s racism, he had worn rags, he had ridden in a beat-up third-hand car … He had seduced Hélène Dessoffy into an affair because she had a house near France’s biggest naval base, Toulon, and we had all fallen for the bastard’s line.”

Dincklage was back in France. The French Sûreté and Deuxième Bureau knew of his movements in and out of Switzerland. They knew he had returned to Paris with the German occupation authorities. For the next four years French counterintelligence agents in France and de Gaulle’s Free French in London would be watching and reporting on their old adversary.

AT AGE FIFTY-SEVEN, Chanel was ready to fall in love again, and in 1940, a great romance unfolded as Dincklage, now a senior officer of the German occupation forces, stepped into her life to play the willing cavalier. It would be Chanel’s last great love affair. There remains only one living eyewitness with intimate knowledge of the Chanel-Dincklage romance in the war years. Gabrielle Palasse Labrunie met Dincklage in occupied Paris in late 1941, when she was fifteen years old and visiting her Auntie Coco. She recalls, “Spatz was sympa, attractive, intelligent, well dressed, and congenial—smiled a lot and spoke fluent French and English … a handsome, well-bred man who became a friend.” She saw how he captivated Chanel: “He was the pair of shoulders she needed to lean on and a man willing to help Chanel get André home.”

For the next few years, Dincklage would manage Chanel’s relations with Nazi officialdom in Paris and Berlin, and he would be involved in arranging for the German High Command in Paris to grant Chanel permission to live in rooms on the seventh floor of the Cambon wing of the Hôtel Ritz. It was a convenient location, as the back entrance and exit of the hotel gave onto the rue Cambon—a few yards from her boutique and the luxurious apartment she set up at 31, rue Cambon. The bizarre story of how, upon returning to Paris, a German general saw a distressed Chanel in the Ritz lobby and spontaneously ordered that she should be lodged at the hotel could only be another charming Chanel myth. Only Dincklage or some other senior German official could have made the complicated arrangements for her to have rooms in the Ritz’s Privatgast section, reserved for friends of the Reich. One only needs to read the German diktat: “On orders from Berlin the Ritz was reserved exclusively for the temporary accommodation of high-ranking personalities. The Ritz Hotel occupies a supreme and exceptional place among the hotels requisitioned.” In fact, only certain non-Germans (Ausländer) were privileged to stay at the Ritz during the occupation. Chanel’s rooms (227–228) were near German collaborator Fern Bedaux (243, 244, 245); the pro-Nazi Dubonnet family (263) and Mme Marie-Louise Ritz (266, 268), wife of the hotel’s founder, César Ritz, lodged on the same floor.

Everyone entering or leaving the Ritz had to be identified to sentries posted day and night at sandbagged entrances. Hitler’s heir apparent and commander in chief of the Luftwaffe and head of all occupied territories, Hermann Göring, was installed in the Royal Suite. Other luxurious rooms were reserved for Nazi Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop; Albert Speer, Reich Minister of Armaments and War Production; Reich Minister of the Interior Dr. Wilhelm Frick; and a host of senior German generals.

For those allowed entry into the Ritz, the German High Command had “strict” orders about the dress of their compatriots: “No weapons of any sort were allowed inside the establishment” (an area near the entrance was set aside for depositing arms), and “manners had to be perfectly correct and no subaltern officer was allowed.” Non-Germans had to be invited before entering the hotel.

What was it like in 1940 at the Ritz? A printed decorative menu for June 14, the day German officials occupied the hotel, survives. In this desperate moment for the French as hundreds of thousands of French families fled the German onslaught, the Ritz’s first wartime Nazi guests were offered a sumptuous menu. Lunch included grapefruit—in wartime, a rare treat—and a main course of either filet de sole au vin du Rhin (sole cooked in a dry German wine, and an obvious flattering choice from the vanquished to the conqueror) or poularde rôtie, accompanied by potatoes rissolées, fresh peas, and asparagus with a hollandaise sauce. For dessert, there was an assortment of fresh fruit.

Later, when French families were near starvation, senior German officials and their guests would go on dining at the Ritz restaurant. One German officer in the early days of the occupation wrote: “In times like these, to eat well and eat a lot gives a feeling of power.”

Cocteau, Serge Lifar (the Ukrainian-born ballet artist), and René de Chambrun were permitted by the Nazis to dine at the Ritz. They enjoyed a regular lunch and dinner there, often as Chanel’s guest at “her” table—rubbing shoulders with the Nazi elite including frequent visitors from Berlin: Joseph Goebbels, Dincklage’s former chief, and Hermann Göring, Lifar’s patron and admirer. Lifar, the former lover of Sergei Diaghilev, founder of the Ballets Russes, lived part-time at the Ritz. Hitler had met Lifar on the führer’s only trip to Paris, immediately after France’s defeat. Göring then appointed Lifar head of the Paris Opéra corps de ballet. Chanel believed “the Germans are more cultivated than the French—they didn’t give a damn what [men such as] Cocteau did because they knew that his work was a sham.”

Another guest was Dincklage’s protégé, Baron Louis de Vaufreland Piscatory.

The winter of 1940–1941 was bitterly cold—but not so at the Ritz. Chanel “was seen everywhere with … Spatz Dincklage.” Writer Marcel Haedrich claims that Chanel told him, “I never saw the Germans, and it displeased them that a woman still not bad looking completely ignored them.” Haedrich repeats yet another myth: “Chanel took the Metro. It didn’t smell bad, the Germans feared epidemics and saw to it that Crésyl [a strong antiseptic] was spread everywhere.” (Hardly possible; as the mistress of a German senior officer, Chanel would have had an automobile at her disposal.)

For the privileged few, Chanel and her entourage, wartime Paris was really no different than in peacetime. High society went on much as before: nightclubs and cabarets thrived. Dincklage dined often at Maxim’s, where German officers and officials nightly enjoyed the best of French haute cuisine. Chanel and Dincklage were guests at Serge Lifar’s opera and at his Nazi-sponsored black-tie-and-tails evenings there. Lifar, Cocteau, and Chanel were frequent guests at candlelight dinners (because of the power shortages) at the Serts’ apartment at 252, rue de Rivoli. Jojo (Sert) amused his guests with tales of British and American spies in Madrid. Sert was a frequent visitor to Madrid. In 1940 he had arranged to acquire from the Franco government a diplomatic post as the Spanish ambassador to the Vatican, but based in Paris. The Serts and their friends relished the array of food shipped to them via the diplomatic pouch from neutral Spain.

Dining room of the Hôtel Ritz, 1939. During the “Phoney War” the Paris elite dined in luxury from gourmet menus prepared by the hotel’s chefs. (illustration credit 7.8)

Chanel preferred hosting intimate dinners at her apartment on the rue Cambon, where her treasured objects and her precious Coromandel screens were displayed. Meals were prepared by her cook and served by her faithful maid Germaine, who had returned to Paris. On those evenings with beau Dincklage, Chanel would sing and play the piano for her friends. Then, as the guests amused themselves, she and Dincklage would cross the rue Cambon to the back entrance of the Ritz to her third-floor apartment with its whitewashed Aubazine-like starkness.

A common sight during the Nazi occupation—starving Parisians searching in the garbage for food and scraps, September 1942. (illustration credit 7.9)

Nazi collaborator Fern Bedaux, Chanel’s neighbor at the Ritz, reported to Count Joseph Ledebur-Wicheln, her Abwehr contact, how Dincklage (who Bedaux may not have known was an Abwehr agent, too) visited Chanel every day. Bedaux also told Ledebur that Chanel was a drug abuser.

Chanel’s close friend, Paul Morand, who would dub her “the exterminating angel of the nineteenth-century style,” was an important Vichy official during the occupation. He and his “pro-German” wife, Hélène, hosted Parisian soirees where Chanel dined with her small circle of friends: the omnipresent Cocteau, writer Marcel Jouhandeau, and his once-beautiful, eccentric, and erotic ballet dancer wife, Caryathis. Chanel’s old friend and dance instructor prior to World War I, Caryathis was now an aged but intimate friend of André Gide.

But for a truly amusing evening, Chanel would dine with Dincklage’s onetime intimate friend, Francophile Reich ambassador in Paris, Otto Abetz, and his beautiful French wife, Suzanne. Their sumptuous dinners at the ambassador’s residence, the Hôtel de Beauharnais, 78, rue de Lille in Paris (behind what was then the Gare d’Orsay) were the envy of the crème de la crème of Paris and Nazi-occupation society. Abetz’s salons were furnished with handsome paintings stolen from the Rothschild family apartments.

After Abetz, former lawyer and journalist Ferdinand de Brinon, now the Vichy ambassador to the German government in Paris, was the preferred host of the Paris elite, and Chanel dined often at Brinon’s Parisian townhouse. Prize-winning author Ian Ousby, historian of the German World War II occupation, was brutal about Chanel’s comportment at mealtime: “Coco Chanel … indulged in anti-Semitic diatribes” at the Abetz and Brinon dinners. An invitation to such an event was a passport to social intimacy with top Nazis. Pierre Laval’s daughter, Josée, a longtime friend of Chanel’s, and her husband, René de Chambrun, were regular guests of Abetz at the German Embassy evenings. René, nicknamed “Bunny,” was noted for his cutting remark when his father-in-law, Laval, and Marshal Pétain came to power at Vichy, repeating Laval’s words: “That’s the way you overthrow a republic.”

Josée raved when describing an Abetz evening: “Champagne flowed, and the German officers, dressed in white tie and splendid uniforms, spoke only French. Social life had returned with friends and our new guests, the Germans.”

Josée was ebullient about a Christmas gala held in 1940—the first year of the German occupation and a tense moment for Parisians. The Germans had just executed twenty-eight-year-old Jacques Bonsergent at Mont Valérien outside the walls of Paris—the first Parisian civilian to face a German firing squad. But for Josée,

in a blacked-out Paris there was gaiety. Abetz in a uniform half-civil and half-military [Abetz held the rank of an SS lieutenant-colonel] and his wife Suzanne turned about a magnificent buffet dinner while the overweight German Consul in Paris, General Rudolf Schleier, bowed low to the ladies, kissing their hands as did Luftwaffe General Hanesse, dressed in a white uniform—his chest covered with decorations. [Presumably, General Hanesse’s decorations were awarded for killing the French.] The Champagne flowed; the German officers, particularly the pilots, in evening dress did honor to the ladies, moving like butterflies, and no one spoke German. It was a real French gala evening when speaking German was prohibited. The officers competed to be most erudite in the language of Rabelais [French sixteenth-century satirist] … No one thought about the war. We all thought that peace, a definitive peace, a German peace would win over the world with the approval of Stalin and Roosevelt … only England continued to face the Germans.

IN CONTRAST, the daily life of an average Parisian was one of hardship during the coldest winter on record—and each succeeding winter seemed colder. There would be no Champagne soirees for them. Coal for fuel was rare, gas supplies paltry, and electricity frequently cut off. Petrol for automobiles was sometimes available on the black market, but most automobile engines were converted to run on natural gas—two bottles on top of the cars. Some transformed their motorcars to burn charcoal. As the months of occupation passed, things got tighter and tighter.

Within weeks of the German arrival in Paris, everything was snatched from the marketplace to be resold later for two to three times its original price. Within months, the Germans had imposed a regime of virtual starvation on the population. Field Marshal Göring decreed that the French people would have to subsist on 1,200 calories a day—half the number of calories the average working man or woman needed to survive. The elderly were rationed to 850 calories a day. The measures were staggering.

Every commodity was rationed. It was the old folks who suffered the most and risked serious illness or death from hypothermia or undernourishment when they couldn’t keep their apartments warm in the long, cold, wet months of the war years. The American Hospital at Neuilly, still run by an American physician, and Otto Gresser, a Swiss manager, were able to supplement their patients’ diets by arranging for a wealthy French landowner to sell the hospital potatoes for a reasonable price. The foodstuffs were then transported to the hospital kitchen by ambulance. Gresser tells about bartering wine for more potatoes: “We had 250 patients … The French authorities allowed each patient one-half a liter [a pint] of wine per day and soon we had more wine than the patients could drink. The farmers, however, couldn’t get enough wine. We took 500 liters [almost a hundred gallons] of wine and bartered the wine for 5,000 kilos of fertilizer. One farmer gave us 10,000 kilos [about 22,000 pounds] of potatoes for the fertilizer … We gave 50 kilos of potatoes to each staff member and it was very important for them to feed their families.”

By late 1941, meat—desperately needed to fend off malnutrition—was almost impossible to find except at outrageous prices. Gresser remembers that when 300 kilos of beef, bought on the black market, was delivered to the hospital in a big “borrowed” German car, suspicious German authorities asked to inspect the hospital kitchen. The staff then hid the meat in the hospital’s garden.

Even the French staple, wine, was in short supply. In their book Wine and War, Don and Petie Kladstrup tell how wine production fell by half between 1939 and 1942. The Germans loved and knew about wines—particularly the wines of France. Their Weinführers managed to take away not only the best of the annual French production but also massive amounts of ordinary table wine for their armed forces. The Germans shipped more than 320 million bottles of wine to Germany each year at fixed prices.

Göring ordered the Weinführers to systematically ship even mediocre wine to Germany. The result was catastrophic. “The old and the ill needed wine,” French doctors advised German and French authorities. “It is an excellent food … it is easily digested … and a vital source of vitamins and minerals.”