The rich, the clever and well connected escaped punishment—they returned after the storm …

—FRENCH RESISTANT GASTON DEFFERRE

EARLY ON THE MORNING of Tuesday, June 6, 1944, the French-language BBC broadcasts to France told of the Allied D-Day landings at Normandy and proclaimed Paris would soon be freed. Thousands of American, British, French, and other Allied troops had landed on the beaches, parachuted onto roofs and treetops, and glided in on planes only 73 miles (123 kilometers) from the center of Paris. France was startled. The news was soon confirmed by radio and press reports. Le Matin headlined: “France Is a Battlefield Again!”

It was a grim moment for Chanel and other Nazi collaborators. She and Jean Cocteau, Serge Lifar, and Paul Morand were among hundreds whose names could be found on the blacklist kept by the French Resistance. If the Germans were forced to abandon Paris, Chanel and her friends faced trial and punishment at the hands of men and women who had suffered humiliation and worse under the Nazis. In the days that followed, Parisians kept their eyes on the flagpoles atop nearly every public building in Paris. Were the swastikas still there? If so, the Germans were still around. For Parisians, an unadorned flagpole might mean that the Germans had fled.

On the English coast at Portsmouth, Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Commander of the Overlord D-Day operations, seemed to wear a perpetual grin on his face. Whereas, in Berlin, Hitler threw a tantrum. His once-favorite commanders, General Gerd von Rundstedt and General Erwin Rommel, the Desert Fox, had bluntly warned their master to “end this war while considerable parts of the German Army are still in being.” Von Rundstedt was sacked; Rommel committed suicide, to save his family from Hitler’s wrath.

At the Hôtel Lutetia, Dincklage, Momm, and their fellow Abwehr officers began packing their files or burning them. As they made preparations to leave Paris for Germany, Allied warplanes commenced bombing the Paris region. Slowly the Ritz emptied. Its German guests were going home to seek safety.

DINCKLAGE FLED sometime after the July 20 plot to assassinate Hitler had failed. Chanel, age sixty-one (though she could pass for fifty), soon moved into her rue Cambon apartment across from the Ritz in the breathless heat of August when bits of ash once again covered everything. As Allied bombers struck Paris suburbs, the Germans burned documents day and night just as the French had four years earlier when Paris was evacuated. Chanel wasn’t totally alone; she had her butler, Léon, and her faithful maid, Germaine, at her side.

In Berlin, Schellenberg renewed efforts to meet with neutral arbitrators. He finally connected with Count Folke Bernadotte, a Swedish diplomat, and asked him to try to mediate a truce via British diplomats stationed in Stockholm. As a sign of sincerity, Schellenberg ordered his SS agents to free and turn over some American, French, and English prisoners being held at the SS camps of Ravensbruck and Neuengamme. It was his signal to the British that he and Himmler were no longer Nazi die-hards. It would later save Schellenberg’s life.

As the Allied armies approached Paris, Chanel contacted Pierre Reverdy, her on-again, off-again lover of the past twenty years. In the very early days of the occupation Reverdy had made a trip to Paris to see Chanel before he joined a French resistance group to fight Germans. Chanel was not there. She was still with the Palasse family at Corbère. Now at Chanel’s urging he set out to find and arrest Vaufreland. Chanel must have hoped that Vaufreland, the one Frenchman who could prove her connections to the Nazis, would disappear permanently.

With his partisan fighters, Reverdy located Vaufreland hiding at the Paris apartment of the Count Jean-René de Gaigneron. The baron was seized and hauled off with other collabos to a Resistance prison. Later he would be held at the Drancy camp on the outskirts of Paris—the very facility that had so recently housed Jewish families awaiting deportation to Nazi camps. All Vaufreland would say later about Reverdy’s strange intervention was: “He had something against me.”

Chanel’s friend Serge Lifar had been rehearsing the Chota Roustavelli ballet at the Paris Opéra throughout June under opera masters Arthur Honegger and Charles Munch. Now, as Allied forces approached Paris, Lifar turned down an offer to be flown to neutral Switzerland in a private aircraft owned by Austrian conductor Herbert von Karajan. Instead, Lifar slipped into Chanel’s apartment at the rue Cambon to hide. Chanel told a friend, “I couldn’t walk around the apartment even half undressed because Serge might be hiding in a closet.” Later, Lifar gave himself up to the purge committee of the Opéra, and was made to retire for one year—a slap-on-the-wrist punishment for his collaboration with the Nazis. Many of Coco’s close friends had good reason to go into hiding. “Feelings of hatred and revenge permeated French society … there had been so much suffering, humiliation, and shame, so many victims of betrayal, torture, and deportation.” Most Frenchmen had lived through four long years as prisoners, watched over and humiliated by a million or so Germans. People had sought to survive—some honorably; others, like Chanel, Vaufreland, Cocteau, and Lifar would soon be accused as collabos.

THE LAST TRAINLOAD of Jewish prisoners left France on their way to Auschwitz on August 17—days later desperate street fighting between German troops and Free French and Communist partisans broke out. The insurrection to free Paris of the hated Boche invader was under way as General Charles de Gaulle landed in Normandy. Meanwhile, General Philippe Leclerc’s Free French troopers were advancing on the city.

Late in the evening of August 24, Leclerc’s advanced column arrived in Paris. The next day Leclerc tankers clad in GI khakis donated by the Americans, and French sailors, with their distinctive caps topped with a red pompom, invested key points of the city. All of France would be freed in the few months to come.

By August 25, Leclerc’s army had taken Paris, German general Dietrich von Choltitz surrendered, and General Charles de Gaulle, head of the Provisional French Government, entered Paris to meet with Leclerc and other senior officers and aides.

The following day de Gaulle led his famous march down the Champs Élysées to Notre Dame for a solemn mass. Earlier, at the Hôtel de Ville he proclaimed, “Paris! Paris outragé! Paris brisé! Paris martyrisé! Mais Paris libéré”—words that made Parisians cry with joy. They were recorded in English history as: “Paris! Paris ravaged! Paris broken! Paris martyred! But Paris free!”

But for some, the words were ominous—meaning retribution was at hand.

To watch de Gaulle march down the Champs-Élysées to the Place de la Concorde, Chanel, Lifar, and a host of invited guests had gathered at the apartment of the Serts, which overlooked the Place de la Concorde. If their biographers are to be believed, many of them, including Chanel, her friend the Count de Beaumont, and Lifar, were anxious about their highly visible roles as German collabos. They hoped José-Marie Sert, the wartime Spanish ambassador to the Vatican (but living in Paris), might shield them from the vengeance that would be meted out by de Gaulle’s resistance fighters.

Humiliated German officers fallen into the hands of soldiers of the Second French Armored Division, Paris, August 1944. (illustration credit 11.1)

German collaborators were hunted down in liberated France; women who had fallen in with the German invader were humiliated. Seen here are two women bearing Nazi swastikas on their shorn heads. (illustration credit 11.2)

Two weeks later, Chanel was arrested.

AFTER THE LIBERATION, French writer Robert Aron calculated that between thirty and forty thousand collaborators were summarily executed.

To end this drumhead justice, de Gaulle’s Provisional Government established special courts in mid-September 1944 to deal with collaboration. Those found guilty faced execution, others guilty of lesser forms of collaboration—the newly invented crime of national unworthiness (indignité nationale)—were punished by the loss of the right to vote, to stand for election and hold public office, and to practice certain professions.

All over France the arrival of French and Allied troops released powerful forces. In Paris, amid wild celebration, German-language street signs around the Opéra and elsewhere were ripped down with bare hands. Many toasted freedom; others spewed revenge. For known collaborators, there was flight or death; if found, they risked being shot on sight. Handsome women, “horizontal collaborators,” were dragged nude from their homes and had their heads shaved in public. Twelve thousand German troopers, officials, and hangers-on didn’t make it out of Paris. Many would be imprisoned in French camps.

Among them was Dincklage’s former wife, Catsy, suspected by the Free French intelligence officers of being a German intelligence agent. Just before the occupation she had been interned at Gurs, a French camp for German civilians. During the occupation she was released and then returned to Paris. After the war Catsy’s half sister, Sybille Bedford, in a book about the period, claimed Catsy had suffered deprivation during the occupation because she was Jewish.

A secret postwar French intelligence report tells a different story, describing how Catsy worked with the Germans all during the occupation—protected by Dincklage and a host of Nazi friends. The file reveals that after the liberation, Catsy, terrified she might be caught by French resistance fighters, reported to the Paris police. She hoped to find protection but was immediately interned with other German nationals at the former SS holding camp for Jews at Drancy. Later she was held at a camp in Noisy-le-Sec, a Paris suburb. She was finally transported to a detention camp in Basse-Normandie, where she would remain a prisoner for eighteen months.

Catsy was released after repeated efforts by her lawyer. To free her, he presented the authorities with a recommendation for release written by the wife of a senior French officer. But secret French counterintelligence reports reveal that far from being a victim during the German occupation, Catsy was a collaborator, a black market dealer, and a spy for the Nazi regime. She had not lived in hiding as a Jew; instead, she “lived [the four years of the occupation] on the best of terms with the Germans … people she now pretends she abominated.”

To gain her release, “Catsy collected letters from friends who were accomplices in her black market operations selling fine women’s intimate apparel. She used these to try to prove [to liberation authorities] her loathing of the German occupation forces.” The French secret report states: “Despite her testimony to French authorities, Catsy frequently received her ex-husband Hans Günther Dincklage at her rue des Sablons apartment.” They were, after all, fellow Abwehr agents and friends. The report does not spare Dincklage: “Dincklage was an active and dangerous propaganda agent. He employed Mme Chasnel [sic] to obtain intelligence for his service.” The report noted that as Allied forces approached Paris, “Catsy’s friend SS Standartenführer Otto Abetz advised her to leave France.” It concluded, “Maximiliane von Schoenebeck [Catsy] is an agent of the German intelligence service, and her presence in France is a danger to national security. We must assume she received orders to stay in France for the purpose of one day beginning to work again as a spy. She must be considered as undesirable in France.”

Despite the fact that Catsy and Dincklage were officially expelled from France by ministerial decree dated July 5, 1947, Catsy managed to remain in France until her death at Nice in 1978 at age seventy-nine. The Schoenebeck family, in an interview at their home in Austria in the summer of 2010, stated that after the war Catsy was employed by Chanel, but they could offer no proof of this.

SINCE 1942 Chanel had been on an official FFI blacklist. Now, in the first week of September 1944, a handful of young FFI resistance fighters—Fifis as Chanel called them, the strong arm of the Free French purge committee—took Chanel to the office of the committee for questioning.

Chanel’s biographers report that she scorned the armed youths with their sandals and rolled-up sleeves. However, the group that interrogated Chanel had no record of her secret work; they did not know the details of her collaboration with the Abwehr or her 1941 mission with Vaufreland in Madrid. Above all, they had no idea she had been the key figure in the Modellhut peace mission financed by Schellenberg in 1944.

By all accounts, Chanel was more insulted by the truculence and bad manners of the Fifis than by her arrest. After a few hours of interrogation by the épuration committee, she was back in her rue Cambon apartment. Her grand-niece, Gabrielle Palasse Labrunie, recalls that when Chanel returned home, she told her maid, Germaine: “Churchill had me freed.”

Though there is no proof, Labrunie and some of Chanel’s biographers believe that it was Prime Minister Churchill who intervened via Duff Cooper, the British ambassador to de Gaulle’s provisional government, to have Chanel released. Biographer Paul Morand wrote that Churchill had instructed Duff Cooper to “protect Chanel.”

Chanel’s maid Germaine told Labrunie that soon after Chanel “left her rue Cambon apartment abruptly … she had received an urgent message from [the Duke of] Westminster” through some unknown person telling her: “Don’t lose a minute … get out of France.” Within hours, Chanel left Paris in her chauffeured Cadillac limousine headed for the safety of Lausanne, Switzerland.

Churchill’s intervention to shield Chanel from prosecution has been the subject of speculation by biographers. One theory has it that Chanel knew Churchill had violated his own Trading with the Enemy Act (enacted in 1939, which made it a criminal offense to conduct business with the enemy during wartime) by secretly paying the Germans to protect the Duke of Windsor’s property in Paris. The duke’s apartment in the Sixteenth Arrondissement of Paris was never touched when the Windsors were exiled in the Bahamas, where the duke was governor. A Windsor biographer claimed “had Chanel been made to stand trial for collaboration with the enemy in wartime she might have exposed as Nazi collaborators the Windsors and a number of other highly placed in society. The royal family would not easily tolerate an exposé of a family member.”

The royal family was so touchy about the duke’s collaboration that Anthony Blunt, the royal historian, was sent to Europe in the final days of the war. Blunt, who was later exposed as a Russian spy, traveled secretly to the German town of Schloss Friedrichshof in 1945 to retrieve sensitive letters between the Duke of Windsor, Adolf Hitler, and other prominent figures. (The duke’s correspondence with Hitler and the Nazis remains secret.)

Chanel certainly knew of the duke and his wife’s pro-Nazi attitudes; she may have known about his correspondence with Hitler. MI6 agent Malcolm Muggeridge was in Paris at the liberation as a British liaison officer with the French sécurité militaire. He marveled at the way Chanel had escaped the purges: “By one of those majestically simple strokes which made Napoleon so successful a general, she just put an announcement in the window of her emporium that her perfume was available free for GIs, who thereupon queued up to get free bottles of Chanel No. 5, and would have been outraged if the French police had touched a hair on her head.” Chanel managed to put off testifying before a court that decided the fate of Maurice Chevalier, Jean Cocteau, Sacha Guitry, and Serge Lifar.”

CHANEL WOULD MAKE LAUSANNE one of her homes from 1944 onward. Dincklage was hidden by friends from the Allied occupation forces in Germany or Austria. Later, he joined Chanel at the four-star Beau Rivage hotel on Lake Leman, where Chanel resided before buying a house in the heights above the lake and forest of Sauvabelin, Lausanne.

With the end of World War II, Chanel made frequent trips to Paris. From there, she and Misia Sert traveled to Monaco and returned to Lausanne to buy drugs. As obtaining controlled substances was dangerous, the pair went to cooperative pharmacies outside France for their drugs, according to Misia Sert’s biographers. They took for granted that their “powerful friends” would protect them.

Misia was “reckless and impatient. She made no attempt to hide what she was doing. Chatting at dinner parties or wandering through the flea market she would pause to jab a needle right through her skirt. Once in Monte Carlo she walked into a pharmacy and asked for morphine while a terrified Chanel pleaded with her to be more careful.”

In Switzerland Chanel had privileged relations with a pharmacy in Lausanne, and she and Misia visited there to buy their drugs. “The two old friends had changed over the years: Chanel’s gamine beauty had turned into simian chic, her shrewdness to vindictiveness. Misia, once full blown and radiant, had wasted away.” On train trips to Lausanne “they sat deep in talk and laughter, distinguished and elegant. Habit—that weaver of old friendships—had made them indispensable to each other.”

Misia Sert’s biographers claimed that when Chanel was with “her fellow collaborationist Paul Morand, Chanel still criticized Misia’s relations with Jews and homosexuals; and she complained that Misia was a perfidious devourer of people, a parasite of the heart. But despite her hatred, she told Morand, whenever she needed someone she turned to Misia, for Misia was all women and all women were in Misia.”

IN THE LAST FEW MONTHS of the war, Winston Churchill was desperately busy with the political aftermath of the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt, the Soviets grabbing Berlin, and the German surrender in May 1945. Yet he still found time to be involved in the affairs of Chanel and Vera Lombardi; the latter was, after all, a member of the British aristocracy and a personal friend of Churchill, the Duke of Windsor, and the Duke of Westminster, as well as close to members of the royal family.

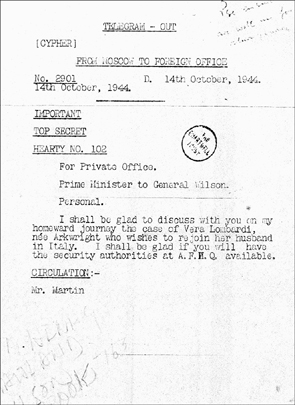

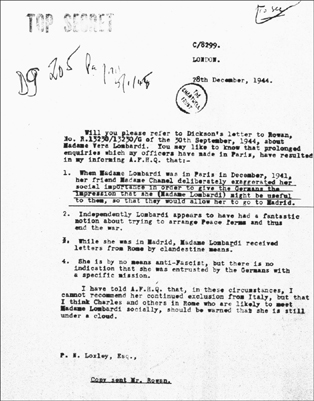

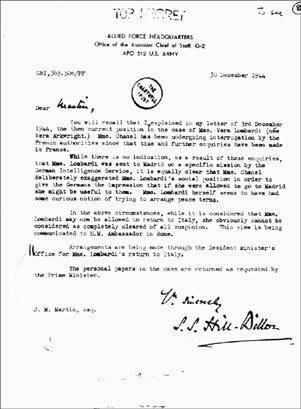

From the winter of 1944 through the spring of 1945, Colonel S. S. Hill-Dillon at Allied Force Headquarters in Paris sent a number of messages to Churchill at 10 Downing Street. In one dispatch, he informed the prime minister that investigators wanted to know why Vera Lombardi had been “sent to Madrid on a specific mission by the German intelligence service.” On December 28, 1944, P. N. Loxley, a senior officer of SIS-MI6 and the principal private secretary to Lord Alexander Cadogan, the permanent undersecretary of the Foreign Office, sent the following top secret dispatch to British Armed Forces Headquarters (AFHQ) in Rome. A copy was sent to Churchill’s secretary at 10 Downing Street, Sir Leslie Rowan. (It contains a wrong date.):

When Madame Lombardi was in Paris in December 1941 [sic], her friend Madame Chanel deliberately exaggerated her social importance in order to give the Germans the impression that she [Madame Lombardi] might be useful to them, so that they would allow her to go to Madrid.

Independently, Lombardi appears to have had a fantastic notion about trying to arrange Peace Terms and thus end the war. While she was in Madrid, Madame Lombardi received letters from Rome by clandestine means. She is by no means anti-Fascist, but there is no indication that she was entrusted by the Germans with a specific mission.

I have told A.F.H.Q. that, in these circumstances, I cannot recommend her continued exclusion from Italy … I think [those] in Rome who are likely to meet Madame Lombardi socially should be warned that she is still under a cloud.

While negotiating with Stalin in Moscow, Churchill found time, on October 14, 1944, to send this top secret personal telegram to General Wilson in Rome: “FROM MOSCOW TO FOREIGN OFFICE: I shall be glad to discuss with you on my homeward journey the case of Vera Lombardi née Arkwright who wishes to rejoin her husband in Italy. I shall be glad if you will have the security authorities at A.F.H.Q available.” (illustration credit 11.3)

Previously Churchill’s office at 10 Downing Street had been informed by a British official at the Foreign office:

from the outset [Vera Lombardi] was regarded with suspicion by our people in Madrid who found her story of her journey through Germany and German occupied territory unconvincing and contradictory. There was also conclusive evidence that she was directly assisted by the Sicherheitsdienst [Schellenberg’s SS Intelligence service].

In Madrid, in the waning days of 1944, Vera’s efforts to return to Rome seemed in vain. Then, just after the New Year of 1945, the British Foreign Office advised the Madrid Embassy in cipher: “Allied Forces Headquarters have withdrawn their objection and the lady is free to return to Italy. Prior notification of place and date of arrival will be necessary.” Churchill had intervened.

Four days later, Downing Street sent a top secret note to Colonel Hill-Dillon at Allied Force Headquarters in Paris: “I have shown the Prime Minister your letter of December 30 … about the case of Madame Lombardi; and Mr. Churchill asked me to thank you very much indeed for the enquiries made and all the trouble that had been taken in this matter.” (The signature on the note is illegible.)

December 1944 top secret dispatch from British diplomat reporting how Chanel “exaggerated [Vera’s] social importance in order to give the Germans the impression that she (Madame Lombardi) might be useful to them, so that they would allow her to go to Madrid …” (1941 date is an error.) (illustration credit 11.4)

Vera was finally reunited with her husband, Alberto, in April or May 1945, as her thank-you letter to Churchill makes clear:

Rome, 9 May 1945

My Dear Winston,

Thank you with all my heart for what you found time to do for me and forgive me what I can’t forgive myself. That you should have been obliged to give such a useless person a thought in a time when you certainly were saving the world. Randolph has been a great joy to us here and I shall sadly miss him. His English character and great big heart are the breath of life to me after being cooped up in these stifling countries five years.

Please God I’ll get home soon and come up to breathe for a brief space.

Affectionately and gratefully,

(Sgd.) VERA

In the meantime, Alberto Lombardi had managed to bury his past connections with Mussolini. He went on to serve the Allies as he had the Fascist dictator. Vera Lombardi died from a severe illness in Rome a year after her return from Madrid.

A FEW MONTHS after Paris was liberated, French general Philippe Leclerc’s armored division liberated the French city of Strasbourg and American troops broke out of the German trap at the Battle of the Bulge. Two months later, Soviet troops entered Auschwitz, the SS-run Polish death camp. Meanwhile, Dincklage had arranged through the Berlin Abwehr—now controlled by General Schellenberg—to have a German firm open negotiations with Swiss authorities with the aim of obtaining a permit for him to visit Switzerland. According to the Swiss Alien Police, a German firm—United Silk-Weaving Mill, Ltd., Berlin—sought permission for Dincklage to travel to Zurich for talks with the company’s Swiss subsidiary and the German industrial commission in the Swiss capital of Bern. The company maintained that Dincklage was to negotiate the import of silk and the export of tools. In actuality, the transaction involved swapping Swiss-made artificial silk for German cast-steel tools. According to the United Silk-Weaving Mill, the deal was worth 1.2 million Swiss francs.

The Swiss authorities saw through the subterfuge. They denied Dincklage’s entry permit in December 1944. The Swiss report is succinct: “The German citizen of the Reich, Hans Günther von Dincklage, resident of Berlin, is refused an entry permit into neutral Switzerland.”

Later, Dincklage used a Swiss attorney to apply to become a naturalized citizen of Liechtenstein—which would automatically allow him to enter Switzerland. The Swiss Department of Justice and Police now advised Liechtenstein authorities that Dincklage was an unwelcome person. His application for citizenship was refused.

Bern had not forgotten how, in 1939, Dincklage had been on an Abwehr espionage mission in their country. The Liechtenstein authorities were told: “Information on Dincklage is negative, and he was banished from France in 1947.” It would not be the last time Dincklage would try to get a legitimate permit to live in Liechtenstein or Switzerland.

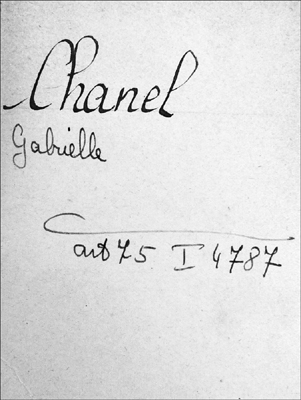

IN PARIS, those in the know were wondering if Chanel’s luck could hold out. In May 1946 at the Paris Cour de Justice, Judge Roger Serre opened a case against her. The case dossier on Chanel for this period has disappeared from national archives of the French Justice Department. All that remains is an index card with her name handwritten on it and the notation “art 75 I4787”—signifying that the file was related to a French article of the penal code dealing with espionage. According to the chief conservator of French twentieth-century archives, the card is a clear indication that “the special French court concerned with collaboration had opened a case under the French penal code concerning Chanel’s dealing with the enemy in wartime.”

By 1946 Judge Serre was eager to question Chanel. His French intelligence sources in Berlin turned up documents describing her as Abwehr agent F-7124, code name Westminster—the nom de guerre drawn from her lifelong friend and lover, Bendor, the Duke of Westminster. Serre’s intelligence team also found that Vaufreland had written a number of reports for the Abwehr. However, they could find nothing written by Chanel. For this reason and because investigators never made the connection to Chanel’s Modellhut mission for the SS, she was never formally arrested. Nevertheless, court orders were issued to bring her before Judge Serre.

December 30, 1944, top secret letter from S. S. Hill-Dixon a senior officer at Allied Force Headquarters in Paris. Letter states “… Mme. Chanel has been undergoing interrogations by French authorities … it is clear that Mme. Chanel deliberately exaggerated Mme. Lombardi’s social position in order to give the Germans the impression that if she were allowed to go to Madrid she might be useful to them. Mme. Lombardi herself seems to have had some curious notion of trying to arrange peace terms …” (illustration credit 11.5)

Chanel knew how vulnerable she had become. She believed she was threatened—not only by Vaufreland—but by Theodor Momm and Walter Schellenberg. The main actors in the Modellhut mission clearly compromised her future in France. And Dincklage, too—what might he reveal under questioning? An astute observer later wrote, “Spatz … was her living hell.” She was “like an angry sea captain walking the deck of a sinking ship.” Pierre Reverdy knew of Chanel’s treason and would later forgive her.

The interrogation of Baron Louis de Vaufreland began with his arrest by Reverdy and his résistance partisans. It would take five years for Vaufreland to be brought to trial at the Palais de Justice, the Paris court where Marie-Antoinette had been tried and sentenced to the guillotine during the horrors of France’s revolutionary purges. On July 12 and 13, 1949, some 160 years later, Vaufreland stood accused of multiple crimes of aiding the enemy in wartime. He faced a single, solemnly robed judge and a four-member civilian jury.

AFTER BEING REPEATEDLY summoned by Judge Serre, Chanel finally appeared before Judge Fernand Paul Leclercq. Her interrogation by Leclercq was based on voluminous court records containing Vaufreland’s testimony about her work for the Abwehr. An excerpt of the court stenographer’s record of her testimony follows. It seems certain Chanel had been carefully coached by her lawyers:

Chanel began by telling Judge Leclercq she had met Vaufreland in 1941 at the Hôtel Ritz and through the Count and Countess Gabriel de la Rochefoucauld.

She added that Vaufreland gave the impression of being “a frivolous young man speaking a lot of nonsense. He was visibly of abnormal morals and everything in his manner of dressing and of perfuming himself revealed what he was. I didn’t trust him. If he was in relations with certain Germans, they could only be of a sexual nature …” However, “he was an amiable boy and always ready to render service.”

Chanel admitted that at the time of their first meeting, Vaufreland knew all about her nephew, André Palasse, who was a prisoner of war in Germany at the time.

Leclercq didn’t press Chanel as to how Vaufreland knew André was a prisoner in Germany or how he came to meet Chanel. In any case, according to Chanel’s testimony, “Vaufreland claimed he could bring him [André] back. I accepted the offer Vaufreland spontaneously made …

“In fact my nephew was repatriated some months later, and I cannot personally say if this was due or not to an intervention by the Germans at the request of Vaufreland. He assured me that he had personally arranged [Palasse’s] freedom, and I continue to believe it.… He seemed very desirous to please me … and I offered Vaufreland money but he refused, only asking me to loan him some furniture.”

As Allied troops threatened to liberate Paris, Dincklage returned to Nazi Germany. In December 1944 he applied for permission to enter Switzerland—one of many efforts he made to join Chanel, who had fled to Lausanne. The Swiss refused his appeal. (illustration credit 11.6)

THE TEXT OF CHANEL’S TESTIMONY does not include Judge Leclercq’s questions to Chanel as the judge went about the process of discovery. However, he pressed her to determine if she was in contact with German officials when meeting Vaufreland. To this Chanel volunteered, “Vaufreland had come to see me on several occasions under the pretext of giving me news of his efforts. Never did he come to my home, at least not into my personal dwelling, in the company of a German. It is possible he came into the store where I was never present and where indeed some Germans came to buy perfume. He never introduced me to any German, and the only German I knew during the Occupation was the Baron Dinchlage [sic], established in France before the war and married to an Israelite.”

Index card from French archives with Chanel’s name handwritten above the inscription “Art 75 I 4787,” referring to a French Ministry of Justice file (never found) and related to Chanel’s suspected collusion with the Germans in wartime. (illustration credit 11.7)

JUDGE LECLERCQ MUST HAVE studied the Vaufreland testimony to Judge Serre. Leclercq pressed Chanel to explain how it came about that she traveled to Madrid with Vaufreland.

Chanel stated,

I met de Vaufreland in the train I had taken around the month of August 1941 to go to Spain. I obtained a passport through regular channels from the Police Préfecture … to obtain it and the visa I personally made the necessary arrangements with the German service … without any intervention on the part of Vaufreland. It was completely by accident that we met on the train. However, I was happy to find myself with him in Madrid because being born of a Spanish mother and speaking the language fluently, he rendered me service in a country where there had recently been a revolution and where police formalities were very strict … He never had an attitude I might suspect. After my nephew’s return, I asked de Vaufreland to put some distance between his visits. In fact my nephew, whom I had asked to be friendly to de Vaufreland … didn’t hide that after a year of captivity he couldn’t bear that sort of person [homosexuals] … And as my nephew was living with me and to prevent any incidents between them—I believed it my duty to warn de Vaufreland.

Judge Leclercq put a series of questions to Chanel based on documents supplied by police and intelligence officers. When asked about her relations with Vaufreland’s Abwehr masters Chanel replied: “I never knew any Germans by the names of Neubauer or Niebuhr … de Vaufreland did not present me to the Germans with whom he had relations.”

Leclercq now questioned Chanel based on sworn testimony made by Vaufreland’s Abwehr boss, German lieutenant Niebuhr, and Sonderführer Notterman (both men were now working for the U.S. Army counterintelligence service [CIC] in Germany).

When Chanel was told of Niebuhr’s and Notterman’s statements about their meetings, their relationships, and Chanel’s trip to Spain, she replied: “I maintain I never asked anything from Vaufreland, neither for my nephew, nor for the trip I wanted to make to Spain.”

Vaufreland had testified before Judge Serre that he helped Chanel get in touch with the Nazi authorities in charge of the Aryanization of property or businesses owned by Jews—in particular about the Wertheimer ownership of 90 percent of the Chanel perfume business. When questioned about this Chanel volunteered, “I never asked Vaufreland to be involved with the re-opening of my perfume business.” Then, with reference to her use of Nazi laws to Aryanize Jewish businesses, Chanel dodged the question, saying, “The Chanel establishments were never sequestrated. There was a temporary administrator for around three weeks; and the business ‘Aryanized’ thanks to a scheme of the Wertheimer brothers with one of their friends … It is possible that Vaufreland overheard a conversation on this subject but I didn’t ask anything of him.”

Judge Leclercq went no further. He apparently did not know that Félix Amiot—a non-Jew with connections to Hermann Göring—had taken over the Chanel perfume business in trust for the Wertheimers.

Chanel continued: “As for my Spanish trip, the official purpose of it was the purchase of primary material essential to the manufacture of perfume, and it was for this reason that I obtained my passport … It is true that I knew people in high circles in England, with whom I spoke by telephone thanks to the British Embassy in Madrid. I wanted above all to have news about the Duke of Westminster, who was very ill at the time … I personally knew Mr. Winston Churchill but I didn’t phone him about this subject, not wanting to bother him at that time.”

When confronted with Vaufreland’s sworn statements that an Abwehr officer named Hermann Niebuhr had conferred with Chanel at her office and about an Abwehr-sponsored trip to Spain in 1941, she testified, “As for the alleged visit of Niebuhr to rue Cambon, I protest strongly against this assertion of Vaufreland, who never brought a German to see me. I can even say that I only saw him one time in the company of a German and that was on the last day of the Occupation, when he came by rue Cambon in the company of a German officer …”

Neither Judge Leclercq nor Judge Serre ever referred to Chanel’s second trip to Madrid in 1944 for SS officer Walter Schellenberg. They may not have seen the documents in French intelligence files or, for political reasons, chose to ignore Chanel’s collaboration with the SS. The court never questioned Chanel about her four-year wartime relationship with senior Abwehr officer Baron Hans Günther von Dincklage.

Judge Leclercq then advised Chanel that Niebuhr had given sworn testimony, confirmed by Vaufreland, that the Vaufreland-Chanel mission to Madrid in 1941 was financed by the Abwehr.

Chanel replied: “I protest against his declarations, which are clearly implausible. I have no memory of a German that Vaufreland would have introduced me to.” Then, faced with Niebuhr’s testimony, she said, “At the Ritz, one met many people in a mixed society … Vaufreland may have introduced me to this man whom I would very much like to see; and in any event I certainly didn’t see him in uniform. He must have spoken French fluently which would have left me ignorant of his nationality.”

Continuing, she ventured, “I certainly did not esteem Vaufreland and didn’t hide it because I am in the habit of saying frankly what I think. As to the idea of sending me on a mission to England to approach the Prime Minister and the Duchess of York, Queen of England at the time, [the idea] doesn’t stand up under examination; and I never received money from such an individual … [My financial] situation is sufficiently great for that to be ridiculous. In my opinion this individual [Lieutenant Niebuhr] tried by some fanciful declarations to explain his own relations with de Vaufreland.”

Faced with the records that the Abwehr had registered her as one of their agents, Chanel argued, “I never was aware of my registration in a German service and I protest with indignation against such an absurdity … It is true I passed through the border post of Hendaye but I was never the object and neither was Vaufreland of special treatment on the part of the Germans. We spent two hours standing in a waiting room and after an hour, a German officer, seeing me very tired, had me given a chair. It is the only consideration of which I was the object.” Then, Chanel added, “I remember now … Vaufreland told me that he too was leaving [Paris]. If he believed he had to signal our departure to this Niebuhr, he did it himself without my knowing about it, to undoubtedly avoid difficulties for us at the border.”

Finally, Chanel told Judge Leclercq: “I could arrange for a declaration to come from Mr. Duff Cooper, former British Ambassador, who would be able to attest to the respect I enjoy in English society.”

There is no record that Judge Leclercq made any attempt to discover why Chanel had maintained a long relation with Vaufreland, allowing him to stay at her Roquebrune villa on the Côte d’Azur in the spring of 1942, about the same time she and Dincklage were there.

LECLERCQ HAD PREVIOUSLY interrogated André Palasse. His testimony was to the point:

Before the war, I was Director of the Chanel Silk Establishments. Made prisoner in 1940, I was repatriated in November 1941. Since it was impossible for me to resume the direction of the Chanel enterprise in Lyon, Mademoiselle Chanel … entrusted me with the post of Director of the company with headquarters at 31, rue Cambon in Paris.

I didn’t know Vaufreland before the war. I only made his acquaintance several days after I was made Director … [when] he declared that thanks to his relations with the Germans, I had been liberated. Mademoiselle Chanel also told me that she had asked Vaufreland to use all his influence to get me freed.

I met Vaufreland five or six times at Mademoiselle Chanel’s home. Then I lost sight of him from the beginning of 1942. I cannot be sure that Vaufreland had me freed; I have no proof of it. I repeat—I only knew what Vaufreland and Mademoiselle Chanel told me.

A jury trial in session in Paris’s Palais de Justice where Chanel would give testimony about her trip to Madrid with Abwehr spy Baron Louis de Vaufreland. (illustration credit 11.8)

ON JULY 13, 1949, Baron Louis de Vaufreland was found guilty on a number of counts dealing with cooperation with the enemy and sentenced to six years in prison. There is no record of whether his sentence included time already served in prison. Chanel returned to her safe haven in Switzerland, but Vaufreland’s trial judge was still unsatisfied. The trial record adds, “The answers Mademoiselle Chanel gave to the court were deceptive. The court will decide if her case should be pursued.”

There was no press coverage of Vaufreland’s trial and no mention of Chanel. His sentence had come in the middle of other trials of Nazi collaborators. Judges and juries were overwhelmed with cases, and readers of the French press were inundated with reports of trials revealing Nazi war crimes.

Not the least of the trials covered in the international and French press was the trial of war criminal Otto Abetz—the Nazi general who as Berlin’s representative in Paris during the occupation gave lavish parties at the German Embassy there. In July 1949 Abetz was sentenced to twenty years of hard labor. He was released in 1954 and died four years later in a car accident. His death, the newspapers speculated, may have been a revenge killing for sentencing Jews to the gas chamber.

CHANEL’S DENIAL of her cooperation with the Abwehr and her contradictions of Vaufreland, Lieutenant Niebuhr, and Sonderführer Notterman’s testimonies were never questioned. Chanel was never confronted with a copy of the Abwehr warning to the Gestapo police post at the French-Spanish border town of Hendaye that Chanel and Vaufreland were to be assisted in crossing into Spain. Her nephew André’s slips about Vaufreland’s frequent visits to rue Cambon and his use of Chanel’s office were passed over. There is no evidence Judge Serre or Judge Leclercq pressed Chanel to explain why if Louis de Vaufreland was so odious he was a frequent visitor at her rue Cambon offices and at the Ritz. And Judge Leclercq never questioned Chanel about her relations with Dincklage and her mission to Spain for the Abwehr in 1941. Finally, the court record is void of questions about Chanel’s mission to Madrid for SS general Schellenberg. U.S. authorities didn’t learn until after the war that Chanel’s second mission to Spain for Himmler was financed by Schellenberg, or that his liaison officer in Hendaye, SS captain Walter Kutschmann, was a Nazi war criminal. They may never have been informed by U.S. intelligence sources of this crucial fact.

By 1949, few officials were interested in connecting the dots that led to Chanel’s betrayal of France. The details of her collaboration with the Nazis were hidden for years in French, German, Italian, Soviet, and U.S. archives. Indeed, during the occupation of France, the German authorities pulled documents from French intelligence files and shipped them to Berlin. Later, they would be discovered in Nazi archives by Soviet intelligence officers in Berlin and shipped to Moscow. They remained there as a reference for Soviet intelligence until circa 1985. An agreement between Russia and France finally provided for thousands of files to be repatriated to the French military archives at the Château de Vincennes.

THE VAUFRELAND INVESTIGATION in France and Germany took some five years and involved police and intelligence organizations in Berlin and Paris. Details in French intelligence files were known only to a few—and British and French intelligence services did not share information. Vaufreland’s testimony and the statements of the German Abwehr officers who had dealt with Chanel in Paris (both Niebuhr and Notterman were working for Allied intelligence services after 1945) were found in hundreds of typescript pages recently declassified by French and German authorities.

French men and women who lived through the occupation had closed their eyes to the atrocities of the Nazis. When asked about their lives during that era, many replied, “The days of the German occupation of France were hard times. During the war years, strange things happened … better to put all that behind us.”

AFTER TESTIFYING at the Vaufreland trial, Chanel quietly slipped back across the French border to a house she had bought and redecorated near Lausanne. Her four years of collaboration never really became a public issue.

Dincklage spent time hiding in postwar Germany as Allied interrogators sought out former Abwehr and SS officers. Later, he sought refuge at his aunt’s estate, Rosencrantz Manor near Schinkel in northern Germany.

In October 1945 he was on his way to Rosencrantz with an American GI named Hans Schillinger, a friend of Chanel’s former photographer Horst. Suddenly the two men were stopped by a British patrol as they crossed the Nord-Ostsee canal in the British zone of Germany. Dincklage was in trouble. He was found to be carrying more than $8,000, 1,340 Norwegian kroner, 100 Slovak koruna, and 33 gold pieces at a time when it was a crime to transport large sums of undeclared foreign currency across Allied zones. He and Schillinger were arrested and the money impounded as British authorities launched an investigation.

During questioning by British military police, Schillinger admitted “he received the money from Mademoiselle Chanel of Société des Parfums Chanel while he was on leave in Paris. Chanel had asked him to deliver the money to Dincklage.”

The British finally confiscated the money and the men were released. Much later when a British officer questioned Chanel in Paris they received the following reply to a question put to her: “Mademoiselle Chanel has stated she does not want the money back as it might involve her in trouble with the French government for being in possession of undeclared foreign currency. [S]he therefore desires that it be donated to any charity the authorities wish to name.” There is no record of how the British finally disposed of the confiscated money.

In December 1945, Dincklage reached Rosencrantz Manor, where his mother, Lorry, had been living during and since the war. Shortly thereafter, Dincklage joined Chanel in Switzerland.

The Rosencrantz estate near Kiel, Germany, where Dincklage lived for a short time while he tried to get permission to join Chanel in Switzerland. (illustration credit 11.9)