There are squashes coming up in the 12ˇ x 12ˇ plot in which the pigs used to dig and fertilize the soil. Those vegetables are the herds’ growing legacy since they left for the slaughterhouse last fall. Two small hoop houses are abuzz with bees, pollinating the tomato plants. Sweet pea tendrils spiral up and out the deer fencing that encloses this garden. Some will become deer’s graze, but that’s the way it is. Every creature has to eat, and Daniele Dominick, the owner of this garden/mini-farm behind the Scottish Bakehouse restaurant in Vineyard Haven, Massachusetts, knows this very well.

Years ago, this land used to be the restaurant’s back parking lot. But Daniele built it up slowly, starting by composting organic material such as coffee grounds and eggshells, which reduced her waste management costs and now provides nutrients to the soil for the restaurant’s kale, carrots, onions, and herbs that were planted for the cooks. This garden is also a surrogate for people like me who can’t, or don’t, garden. A few picnic tables line the perimeter, providing peace and sanctuary. If and when people want to dig in, get their hands dirty, or soak in some of that transformative calm that is gardening, the gate is always open.

To grow is to change — a strange and wonderful perpetual impermanence in our daily and seasonal rhythms — yet this remains largely invisible in the big picture of the circumstances and chain of events that it takes to get a seed from harvest to plate. My hope is to shed some light and hope on growing food we get to eat — or, as is the case for the 26.5 million Americans who live in food deserts, not to eat.

Ron Finley, a guerrilla gardener in South Central Los Angeles, poetically said, “To change the community, you have to change the composition of the soil. We are the soil.” Finley’s legacy is in a city that owns 26 square miles of vacant lots and where, he said in a 2013 TED talk, “the drive-thrus are killing more people than the drive-bys” because people are dying from diseases like obesity and diabetes that grow out of terrible diets.

What we grow and how we grow impacts us today and for generations to come. What if we grew as if seven generations of life depended on it?

Save farmland by developing a succession plan. Diversify the crops you plant. Grow lightly with great returns, as in aquaponics. Plan community gardens. Grow free food for more people, as does the eloquent Finley. Think very local and create a kitchen garden. Every day, we grow a little bit. Some days — if and when we’re lucky — we grow more than others.

It took 16 years for Krishana Collins to be able to unpack, settle down, and have a farm she could call her own. Now she has a 75-year lease on Tea Lane Farm in Chilmark, Massachusetts. “When I tell people about it, they’re like, ‘The town sold you the buildings for one dollar and gave you the land to farm for how long?’

“Yes,” this sprightly nymph answers. “And I hope other towns will look around and see if this is a solution for their farming community one day.”

Tea Lane Farm, an old dairy farm located in the agricultural heart of Martha’s Vineyard, had fallen into disrepair. The town and the family who owned the farm agreed on a selling price; the town and the Martha’s Vineyard Land Bank (a conservation organization established in 1986 by the voters) then split the responsibilities of use and caretaking between themselves, signing an agreement that would allow for a “tenant farmer” who could lease three acres to farm for a one-time payment of $20,000 for a 75-year lease. The town also sold the four buildings (a 1755 house and three outbuildings) to the farmer for $1. In exchange, the farmer committed to living on the property for at least 11 months a year and submitting to an annual performance review. The town of Chilmark put out a request for proposals for use of the Active Farming Area, and interested parties submitted their farm plans for the buildings and land, which were reviewed by the town’s special Farm Committee.

Chilmark received at least six proposals from area farmers. As a bystander, I found it gut wrenching to watch, because we live in a small community where farms are scarce and land values extraordinarily high. To have friends and neighbors compete for such high stakes was trying for me, but I know not as difficult as for the farmers who were competing against each other. Because this particular property evoked so much emotion from the community, people had very strong opinions and a sense of ownership about it.

But what ultimately kept the community together was that no one wanted the property to be developed. The town and the MV Land Bank collaboration protected the land from being developed into another McMansion, a second or third or fourth vacation home.

Krishana won the bid with a solid business plan, her established flower business, and a livestock proposal to raise sheep and cattle herds in the effort to improve the farm’s soil. A committee member was quoted in the local press as saying, “She seemed like she was determined, that’s what sold me.” At her presentation in front of the town’s Farm Committee, Krishana said, “I’ve been farming for 20 years and I’ve never given up and I’ve persevered on borrowed land and . . . I know I can carry it to Tea Lane Farm. I want people to drive by and be proud.” Krishana has finally unpacked, and she is going to be farming for a while now.

When I drive south out of my hometown, Madison, Wisconsin, on U.S. 151 through Fitchburg to Verona, I cuss a lot. Because along that old familiar route, there used to be acres of fertile farmland. Working open spaces, dairy farms, local life, and culture. Now it’s housing developments. Suburban sprawl. One municipality dissolves into the next in rote houses, slick tarmac roads, and mini strip malls. I know people need and deserve decent houses to live in, and we also need land to farm for food security and food sovereignty. Smart development includes wise and thoughtful farm transfers, the succession of farmland from one generation to the next, whether it stays in the family or not. A farm succession plan helps current landowners plan for their retirement. Land For Good (landforgood.org) has several useful, free downloadable guides. Here’s a summary of its Farm Succession Guide. Start here to save farmland.

Farm owners: What are your hopes and dreams? Your goals? What do you want your farm legacy to be?

Who has a stake in the farm? Identify family, nonfamily, CSA members, and neighbors.

If you know whom to transfer the farm to, identify advisers such as a lawyer, accountant, lender, and Extension agent, and prepare the documents for the transfer.

What do you need to consider regarding financial needs, time lines, heirs, successor, tax implications, and affordability for the next owner?

Estimate retirement needs; inventory farm assets; talk to family members; update business plan; learn about easements, leases, and other creative transfer tools.

— Excerpted with permission from Land For Good

Asset transfer: Spell out how farmland, buildings, and other assets are conveyed from one party to another.

Goal setting & Family Communication: Set forth personal, family, and business goals, as well as ways to ensure constructive communication among all involved.

Management transfer: Lay out how management tasks, responsibilities, and income shift over time from one farm operator to another.

Business plan: Set out strategies for farm operations, personnel, marketing, finance, and business entity formation.

Estate: Direct the eventual transfer of assets, usually with the goal of preserving as much of the estate value as possible for the beneficiaries.

Land use: Map out land use options that address agriculture, forestry, and recreation uses as well as conservation and development.

Retirement: Address how and where the retiring person(s) want to live, their anticipated income, and health-care costs.

“Two out of three farms will likely change hands in the next 20 years. Ninety percent do not have an exit plan.”

— Land For Good (landforgood.org)

Land For Good (landforgood.org), whose slogan is “Gaining Ground for Farmers,” is a nonprofit that connects land and farmers in New England. It offers help for farmers like Krishana who need land, landowners who are seeking to transfer and preserve land for agricultural use, farm families who are interested in turning over farms to the next generation, and concerned communities.

Kathryn Z. Ruhf, the executive director, said in an informational YouTube video about her organization that it “is one of the few organizations nationally that focuses on the issues of land access, farm transfer, management of working lands, land tenure, and really helping at a project level, including individual clients. So it is a very unique niche.” Farm seekers, farm families, landowners, and communities are the recipients of the organization’s help. But truly, that is all of us, because we’re all part of a community somewhere, and we all have to eat. Though this organization is based in New England, the information and advice it provides are important and applicable across the country.

Town, village, and city decision makers, public officials and civic leaders — here are some suggestions about how to support farmers in your community.

Do you live in a city with vacant lots, boarded buildings, and stretches of urban wasteland? Perhaps no American city more than Detroit has seen itself so gutted by the boom and bust cycles of capitalism. That ravaging included a drastic reduction of the city’s trees, too. According to the website of the nonprofit Greening of Detroit (greeningofdetroit.com), in the three decades between 1950 and 1980, approximately 500,000 trees in the city were lost to urban expansion, attrition, and Dutch elm disease. By the end of the 1980s, the city was losing “an average of four trees for every one planted.”

The Greening of Detroit set out to reverse this trend and make good use of the city’s abundance of vacant land, which was estimated to be about 20 square miles. Its mission is to inspire “sustainable growth of a healthy urban community through trees, green spaces, food, education, training and job opportunities.” Look to their experience for ideas of your own, in your own place.

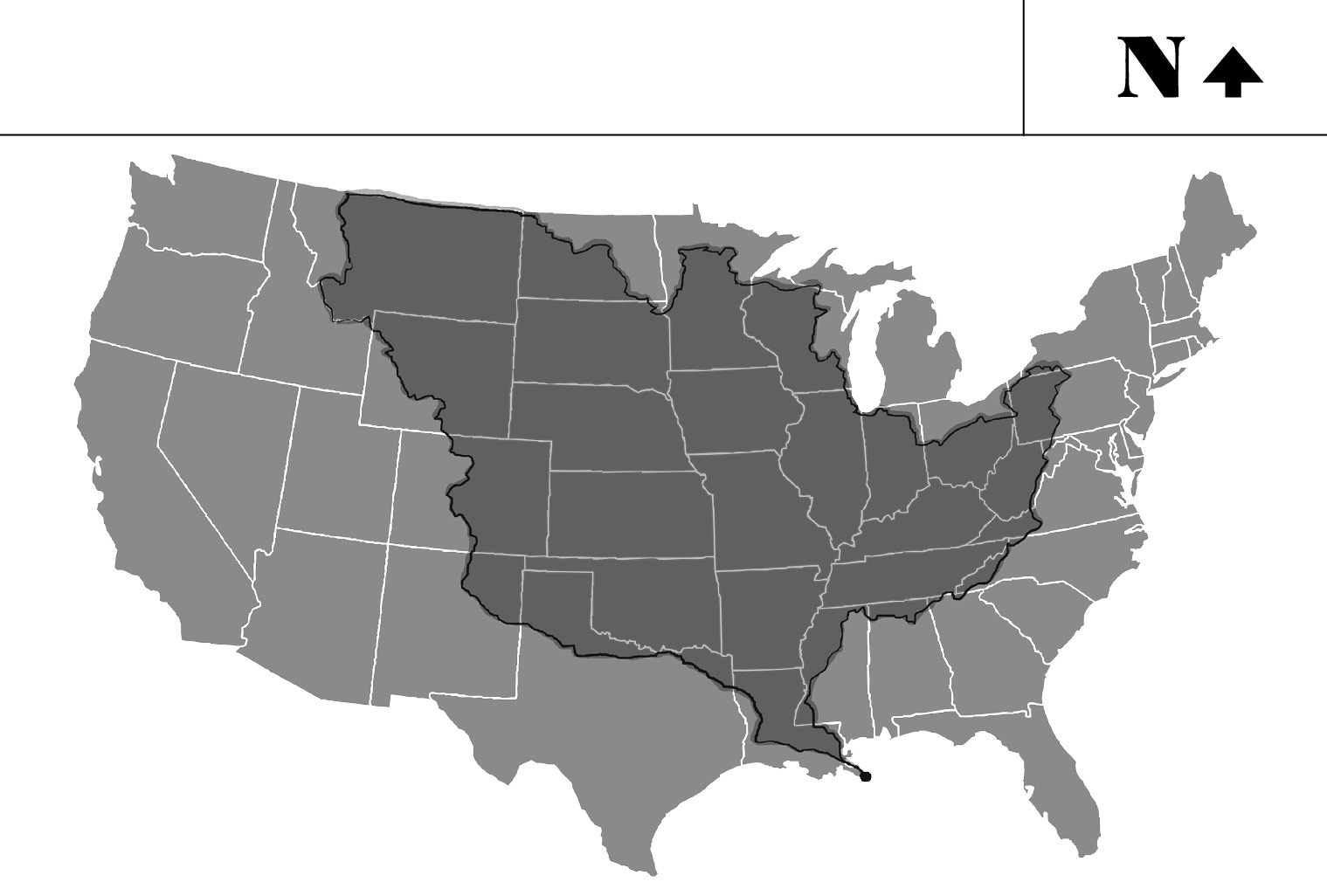

Local growing practices have implications beyond the farm, as a group of Iowa farmers fishing in the warm waters of the Gulf of Mexico discovered. Their vacation fishing showed them that their own pollution was deadening the miles and depths of the formerly most fertile waters in North America, and they returned home determined to figure out how to send clean water down the Mississippi River and into the delta. This story is covered in Green Fire Productions’ series of films, Ocean Frontiers (ocean-frontiers.org). The series seeks to address the question of how to “meet our ever-expanding demands on the ocean without destroying it.” Watch these films; screen them in your communities, and see how collaboration between states, farmers, and fishermen works in this massive effort to fix an environmental disaster, both on the land and in the sea.

Imagine growing up in the United States, then moving to a place where you couldn’t grow sweet corn. Or tomatoes. Or collards. Now imagine that you are from the region of Minas Gerais, in southeastern Brazil, and have moved to the United States; you’d miss taioba (Xanthosoma sagittifolium) the way an American would miss the common vegetables grown here.

There were big smiles and lots of gesticulating when I popped open my trunk to display the taioba plants I was driving to different gardeners. The guys in the van next to me were on their way to work when I pointed to the plants in my car. “Taioba!” I said, but they shook their heads. “Not here!” It turns out, taioba can grow in Massachusetts, just not year-round. Though this staple grows in a rainforest, during the summer on Martha’s Vineyard, the climate is similar enough.

Island Grown Initiative collaborated with the UMass Ethnic Crops Program to support local farmers in diversifying their crops to meet the demands of a growing local immigrant population of Brazilians. In 2006, there were an estimated 3,000 Brazilians living and working on Martha’s Vineyard. That’s a big potential market for farmers, and especially for a crop that evokes home for so many.

UMass did the science in figuring out how to grow crops from Brazil (as well as Honduras and Ecuador, because of additional large immigrant populations in Massachusetts from those countries) in New England. Island Grown Initiative did community outreach in both English and Portuguese with help from the Vineyard Health Care Access Program. Elio Silva, a local Brazilian businessman, helped connect the crops, the visiting UMass graduate students, and the farmers to eaters. Taste tests were held at the local grocery store, and a few chefs incorporated the produce in their menus. If you can get people to taste something new and show them how to cook with it, you will help drive the market. Best of all: to see the joy on people’s faces when they saw their beloved taioba again.

In the summer of 2008, taioba (along with jiló and maxixe) found its way onto the Martha’s Vineyard Agricultural Fair’s list for the first time in its 130-plus-year history, and local growers scooped up some red, white, and blue ribbons.

The number of immigrants in the United States — in 2009, 12.5 percent of the total U.S. population, or 38.5 million people — provides an opportunity for farmers to diversify their crops. Many crops grown in other parts of the world can also be grown in the United States; it just takes research to figure out how. Farmers in communities with large populations of immigrant groups, be they Hmong, Iraqi, or Jamaican, can profit from providing something for these varied culinary preferences.

The National Agricultural Library of the U.S. Department of Agriculture coordinates the Alternative Farming Systems Information Center (afsic.nal.usda.gov), which gathers information about growing ethnic vegetables. In addition to the University of Massachusetts Ethnic Crops Program, the University of Kentucky, the University of Maryland World Farmers, and Rutgers all address the burgeoning popularity of ethnic vegetables.

Flats Mentor Farm is a program of the nonprofit World Farmers (worldfarmers.org). Their CSA pledges to its members “an array of ethnic vegetables that would otherwise not be found . . . without traveling to Laos, Kenya, and Brazil.” Flats Mentor Farm supports immigrant farmers with land, infrastructure, and technical and marketing assistance. In July of 2014, Fabiola Nizigiyimana, a refugee from Burundi, a single mother of five, and a farmer at the Flats, was honored as one of America’s Champions of Change in Agriculture at the White House, for her efforts in founding a farmer co-op for 230 farmers (from countries including Tanzania, Nigeria, Uganda, Kenya, Laos, and Haiti) on the 40 acres of river bottom that is the farm. It’s like a United Nations of small, sustainable agriculture.

Moreira, as the executive director of World Farmers, has particular insight and expertise in working with immigrants. She is herself from the Azores, and a farmer as well. At Flats Mentor Farm, she started a CSA as a transitional mode to help build the capacity of the farmers, while they met and worked on developing a co-op for themselves. The CSA, supported by mentoring, helped farmers at Flats learn about harvesting, quality control, food safety, and marketing. And it fed people. Here’s her advice.

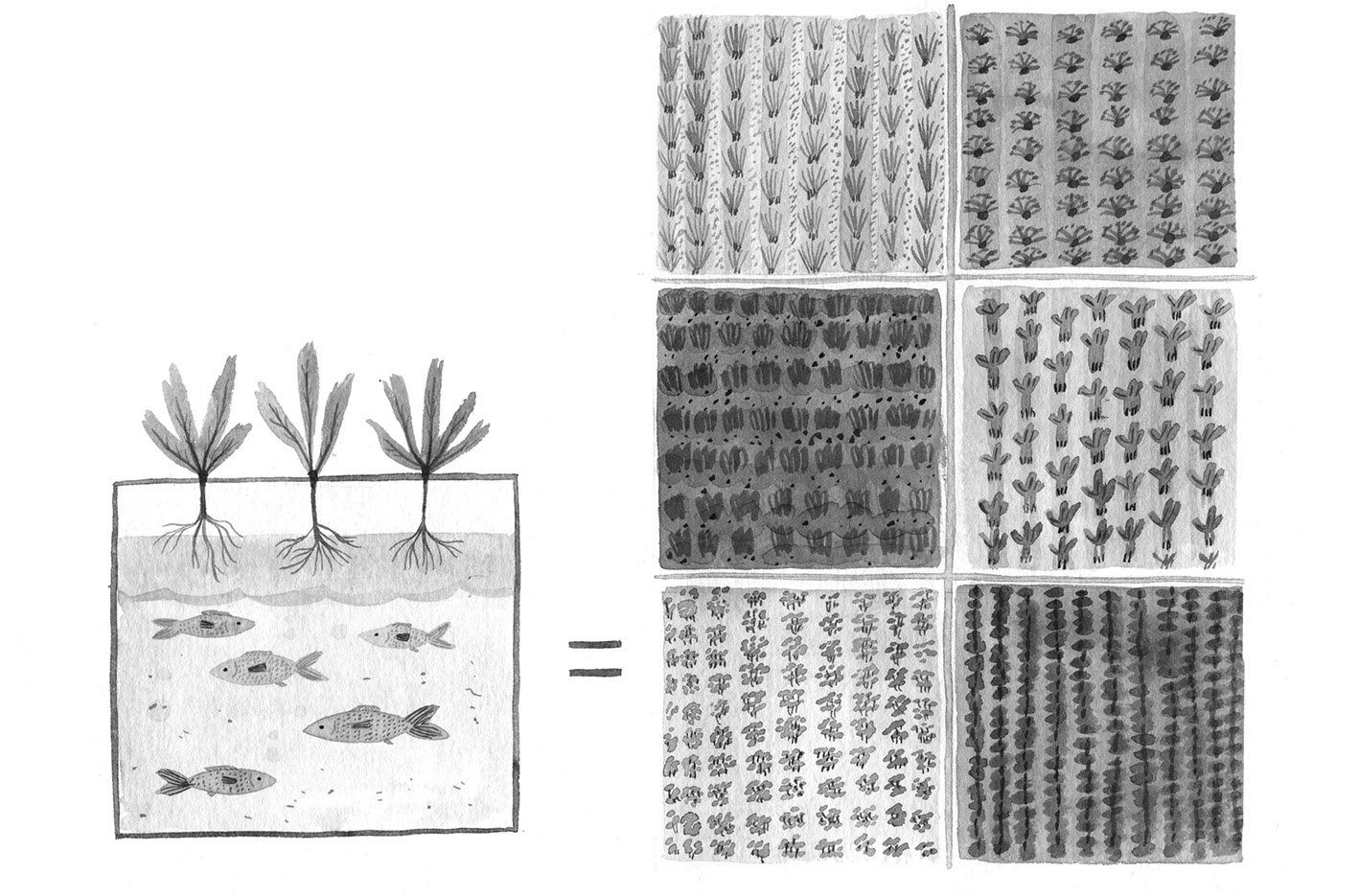

John Pade, a fourth-generation dairy farmer and the cofounder and owner, with Rebecca Nelson, of Nelson and Pade Inc., remembers picking rocks out of the fields with his grandfather and father on their Wisconsin dairy farm. “Every spring they’d look up at the sky and say, ‘If only we could control the weather we could make a living farming.’ That’s why I got so interested in aquaponics. For the last 20 years, we’ve been working to reinvent the family farm. One where you can grow good food for your family and community and put your kids through college.”

All year long, it is a perfect summer-solstice day in Nelson and Pade’s aquaponic greenhouse in Montello, Wisconsin. And every day of the year, clean, fresh food is harvested from their greenhouse and sold at a price they determine — to schools, restaurants, and grocery stores as well as direct from their farm stand. Dinosaur kale, Swiss chard, heirloom tomatoes, beets, carrots, herbs, brussels spouts, onions, salad greens, sweet corn, even dwarf fruit trees such as lemon, banana, and pomegranate — just about anything can grow in an aquaponics system. It mostly depends on what you’re trying to do. And then there’s the protein: freshwater fish, in this case tilapia.

There’s no dirt under an aquaponics farmer’s fingernails, yet the food is as organic as organic gets. The fish and plants are about the least stressed around because they live and grow in ideal conditions. Moreover, there’s minimal potential for E. coli and other foodborne pathogens because in this system, E. coli doesn’t exist. It’s not there because fish, unlike warm-blooded livestock, don’t carry the bacteria in their guts.

Clean and alive, this farm is permeated by a Zen calm. It smells healthy but not stagnant or fishy. It’s warm but not too hot or sweaty. This is no test-tube sterile chemistry lab with weird clones and Frankenfish. The tilapia swim against an unpolluted current and are fed a healthy diet three times a day. Unlike farmed salmon, tilapia require very little protein in their diet, since they’re primarily herbivores.

The plants’ root systems, compared to that of their soil-sisters, are small because the plants don’t need to search for nutrients to photosynthesize. The roots are constantly bathed in aerated nutrients, and once they’ve taken up what they need, which is effectively everything, the naturally cleaned water is circulated back into the fish tanks. You couldn’t spray the plants with pesticides if you wanted to, or you’d kill your fish crop. Everything is interconnected, in the most efficient ways possible.

Aquaponics is an example of controlled-environment agriculture (CEA), in which the grower establishes an ideal environment for the chosen crops. In CEA, every living thing grows at its optimal level, from the fish population density to the temperature of the water. Nothing is exposed to pollutants such as acid rain or oil spills. The “fields” where the crops grow and “streams” where the fish thrive do not fall to the mercy of unpredictable or severe weather patterns and events such as hail, unseasonable cold or hot spells, drought, and flooding. And the farmers get to enjoy ambient growing weather year-round, whether it’s a blowing 30-degrees-below-zero Wisconsin winter or a humid Midwestern summer day. Rebecca planted a patch of sweet corn in February, to harvest in March for fun and to accompany the Nelson and Pade’s staff feast, because, well, she could. “Harvesting and eating sweet corn in March. That was pretty cool,” she said.

“When people walk in here they can’t believe how clean it is. They can see themselves living in their greenhouse. For a developing country or an NGO, the fish and vegetable combination seals the deal for communities and governments interested in food sovereignty and biosecurity,” explained Pade the day we walked through their 5,000-square-foot greenhouse.

Indeed, Nelson and Pade work all over the world, in 40 countries, including various locations in the United States and countries with vastly different challenges: Haiti, Costa Rica, Australia, Botswana, and Thailand. As arable land and clean water are diminishing and weather patterns are changing dramatically due to climate change, highly tuned agricultural innovations are an excellent alternative. “When you can control the environment, and not use any mined or manufactured inputs like fertilizers, it’s a highly desirable way for a community, a town, a government, to secure food for its people,” explained Pade.

There are three key points Rebecca Nelson wants you to know about science-based commercial food production in aquaponics:

Give guided tours of your greenhouse. Hold them on a regular day and time, so it’s easier for schools, hospitals, locals, or anyone else to come and learn what you are doing and how.

There is a misconception perpetuated online that you can start an aquaponics business without a significant monetary investment. Yes, you can build a system in your basement for a few hundred bucks and you will harvest some lettuce and veggies and some fish. For home food production, this is a great setup. But a basement or hobby system will not scale up to the needs of a commercial grower. Commercial growers need proven efficiencies, consistent and high-quality products, repeatable systems and processes, and, most important, food safety protocols and biosecurity procedures.

If you want to grow on a commercial scale, you need to treat an aquaponics business like any other start-up. You need a well-thought-out, well-written business plan; adequate start-up and first-year operational funding; proven equipment; a properly designed controlled-environment greenhouse or other structure; proper training and long-term support; and good management and marketing. And of course, there is a cost to all of this. Most commercial projects that we see move forward are funded by someone who has the means to do it as opposed to someone who is seeking grants.

The good news is that as awareness of aquaponics grows, so does the number of successful models out there, which increases the number of farms that will get funded from more traditional sources like banks and private investors.

We have growers who have gotten low-interest loans and USDA-backed loans from the state and federal government, economic development groups, and other agencies that are supportive of sustainable agriculture and local food.

There have been some aquaponic farms that have failed, and if you look back, they typically had a design that just didn’t work, a lack of proper environmental control, and/or insufficient funding.

The successful aquaponic farms emulate the path of other successes, treating a commercial aquaponic farm as a business and not as an overgrown hobby.

Aquaponic growers fall under all kinds of regulatory umbrellas that were never intended to prohibit aquaponic farming, but often they do. Or at least, getting started is complicated and costly.

Departments of health, agriculture, fisheries, and natural resources of cities, counties, states, and the federal government all can have regulations that might affect an aquaponic grower. And the regulations vary in each location, so there is no clear road map we can provide showing where to go for what permits. And then there are zoning and building permits that have to do with establishing and running your business in a particular location.

It sounds intimidating, but growers find their way through it every day by educating the decision makers about what aquaponics is and how an aquaponic farm benefits a community. As an example, when we moved back to Wisconsin, there were nine permits/licenses that we needed to build our first greenhouse, and it took about six months to get it all done. Over the years, we have spent a great deal of time working with state officials, regulators, and representatives of the Department of Agriculture Trade and Consumer Protection (DATCP) and the Department of Natural Resources (DNR). We have also collaborated with the Wisconsin Aquaculture Association and University of Wisconsin system to help get the word out. Now, it takes two to four weeks and half the number of permits to start an aquaponics business in Wisconsin. In fact, the DNR has hired someone specifically to help businesses like ours get through any regulatory hurdles. As a note, most of the regulation you deal with has to do with either building the greenhouse or moving and holding live fish.

For prospective aquaponic growers, it is important to do your homework, both on the funding and business planning side and the regulatory side. There are excellent resources out there that can help, and likely someone nearby has already been through the process who might be able to offer some guidance.

—Rebecca Nelson, of Nelson and Pade Inc., adjunct instructor at University of Wisconsin–Stevens Point

There is a lot of talk about urban agriculture. With Greens & Gills (greensandgills.com), it is more than talk. This organization runs a profitable urban farm without government help or grants. It produces fresh fish and veggies efficiently and supplies local markets in Chicago. At the time its founders were planning their business, it was illegal to do aquaponics within the Chicago city limits because no livestock was allowed in the city, and fish were considered livestock. A few years ago Mayor Rahm Emanuel signed a law allowing aquaponics, and then it took another year to get through all of the other regulations related to growing and selling food in the city. Through great persistence and determination, Greens & Gills became the first legally operating commercial aquaponics farm in Chicago.

The founders of Northstar Homestead Farms (northstarhomestead.com/farm-aquaponics.php) are three of the hardest-working, most creative, and most innovative women I know. They have embraced aquaponics and have integrated the operation and production of their aquaponics greenhouse with that of their all-natural farm. The aquaponics allows them to provide year-round fresh veggies and fish to their CSA customers.

As traditional farmers, the members of the Hafner family were seeking alternative methods of agriculture that were more environmentally friendly and easier than what they had been doing. In 2000, the Hafners transitioned their farmland and cattle to organic and continued pursuing new and innovative methods that they could use on their farm, Early Morning Harvest (earlymorningharvest.com). Adding aquaponics was a way to keep the farm interesting and profitable, and something that would help keep the next generation interested in farming. Keeping the next generation on the farm is a very important component to keep farms farming, especially the good ones!

Food security is foundational to a country’s national security. When people have access to healthy food and their nutritional needs are met, they can learn, work, function, and be productive members of any society. This is what it means to feed human capital in a secure and affordable way. “Someone asked Rebecca what the goal of our aquaponics system is,” recounted John Pade. “She answered, ‘I want to see aquaponics feeding people around the world.’ They thought she was joking, but she’s not.”

Rebecca Nelson is serious when she says aquaponics done properly can “feed the world,” and she’s also not chiming in for Monsanto or Big Ag when she says it. “What kind of seeds people plant in their aquaponics greenhouse is up to them,” she explains. “It’s the same deal as any farm. What we show here, season in and season out — because it’s all really just one long continuous season — is the optimization of science-based food production that doesn’t beholden any farmer to any one input from any one specific company, over and over again. You can grow what you want and it’s beyond organic, naturally. Because if it’s not good for the fish, you can forget about enjoying your Friday Night Fry.”

Aquaponics is a natural system, like a lake system, just optimized. “The Aztecs built rafts, put their crops into them, drifted them out on lakes, brought them back, and harvested the food,” Rebecca says. “We didn’t invent aquaponics, but we perfected it.” While this may sound like hubris, the efficiencies of energy inputs to pounds of food are undeniable.

“In the field in Arizona, one of the biggest lettuce-producing areas in the United States, they typically plant two lettuce crops per year and grow 60,000 to 80,000 heads per acre combined in those two crops. In our aquaponic systems, we grow about 500,000 heads per year per acre, plus about 40,000 pounds of fish, with continuous production and substantially less water. So, we are growing six times more lettuce per acre using one-sixth of the water. Though this production is from our science-based, highly efficient systems and is not typical of all aquaponic systems.

“When you look at energy inputs for that field production, you need to consider: energy for irrigation pumps (lots), fuel for the tractors, plows, transportation of farmworkers and the energy used in manufacturing those tractors, plows, etc., and then include the fuel for moving that lettuce to markets across the United States.

“What aquaponics can do is provide both a protein crop [the fish] and a variety of fresh vegetables. From a nutritional standpoint, that is about as good as it gets, and this makes aquaponics an excellent method of making nutritious food accessible to people around the world. Plus, there are no pesticides, herbicides, or chemical fertilizers used on the plants and no antibiotics or growth hormones used on the fish. From a global perspective, I think there is great potential for aquaponics to have an impact on hunger and improve the availability of fresh and nutritional food choices to people, even in the most remote areas and regions that do not have arable farmland.

“So, even though we have heat and electrical usage in a concentrated space, we’re still using less energy per head of lettuce that goes to a consumer’s plate because we continuously grow so much in a small space.

“Another factor to consider is that modern greenhouses are much more energy efficient than they used to be. We incorporate dual-layer plastics which provide insulation; energy shields to reduce solar radiation in the summer and maintain heat in the winter; energy-efficient heaters; and, often in cold climates, heat sources that include wood, wood waste, or waste heat. Our greenhouse here in Wisconsin uses about half the total energy as those we had in California, even though it is a much colder climate. This is due to improvements in energy efficiency.”

Saving seeds is a revolutionary act. As chemical companies buy up seed stock, it’s vitally important to maintain genetic diversity in food crops. Moreover, saving seeds is a crucial aspect of food sovereignty. When we practice seed saving, we are practicing independence from corporate control. And when we choose open-pollinated seeds — seeds that pollinate naturally by wind or water, by animals like birds and insects and humans — those seeds adapt to changes in the environment and climate and locale, over time. That’s genetic diversity and resiliency, in a seed. When saving seeds, it’s wise to keep an eye on quality. Below are some basic guidelines suggested by Native Seeds/SEARCH (Southwestern Endangered Aridland Resources Clearing House, nativeseeds.org) to consider when saving seeds.

“When you plant a seed, you choose an entire agricultural system.”

— Ken Greene, cofounder of the Hudson Valley Seed Library

According to the Richmond Grows Seed Lending Library in Richmond, California, there are over 300 seed-lending libraries across the United States and in 15 other countries. Seed libraries operate on basic shared principles, encouraging people to grow food, preserve genetic diversity, and develop and support food sovereignty. Seed libraries can also provide the impetus to share and preserve local history and stories.

Community food gardens provide land to people who don’t have access to it otherwise. They are no small undertaking, but the payoffs are big in terms of bringing people together, saving money on food expenses, and sharing costs for infrastructure items such as tools and fencing. Start small, and be well organized, engaging families right from the start as you plan for the long term. This detailed checklist was developed in part by University of California master gardener volunteers under the auspices of the UC Cooperative Extension. You’ll find some of the steps particularly relevant to urban areas. As with everything else in this book, adapt it to your place as needed.

There is a lot of work involved in starting a new garden. Make sure you have several people who will help you. Over the years, our experience indicates that there should be at least ten interested families to create and sustain a garden project. Survey the residents of your neighborhood to see if they are interested and would participate. Hold monthly meetings of the interested group to develop and initiate plans, keep people posted on the garden’s progress, and keep them involved in the process from day one.

A garden club is a way of formally organizing your new group. It helps you make decisions and divide up the work effectively. It also ensures that everyone has a vested interest in the garden and can contribute to its design, development, and maintenance.

It can be formed at any time during the process of starting a community garden; however, it’s wise to do so early on. This way, club members can share in the many tasks of establishing the new garden.

The typical garden club will have many functions, including:

The typical garden club has at least two officers: a president and a treasurer, although your garden club may have more if necessary. Elections for garden officers usually are held annually.

Look around your neighborhood for a vacant lot that gets plenty of sun (at least six to eight hours each day). A garden site should be relatively flat (although slight slopes can be terraced). It should be relatively free of large pieces of concrete left behind from demolition of structures. Any rubble or debris should be manageable: that is, it can be removed by volunteers clearing the lot with trash bags, wheelbarrows, and pickup trucks. Ideally, it should have a fence around it with a gate wide enough for a vehicle to enter. It is possible to work with a site that is paved with concrete or asphalt by building raised beds that sit on the surface or by using containers. You can also remove the asphalt or concrete to create areas for gardens, but such a garden will be much more difficult, expensive, and time-consuming to start. A site without paving, and soil relatively free of trash and debris, is best.

The potential garden site should be within walking distance, or no more than a short drive from you and the neighbors who have expressed interest in participating. If the lot is not already being used, make sure the community supports establishing a garden there. It’s best to select three potential sites in your neighborhood and write down their address and nearest cross streets. If you don’t know the address of a vacant lot, get the addresses of the properties on both sides of the lot; this will give you the ability to make an educated guess on the address of the site.

It is illegal to use land without obtaining the owner’s permission. In order to obtain permission, you must first find out who owns the land. Take the information you have written down about the location of the sites in step 3 to your county’s tax assessor’s office. Or go to a branch office listed in the white pages of the telephone directory. At this office, you will look through the map books to get the names and addresses of the owners of the sites you are interested in.

While you are researching site ownership, contact the water service provider in your area to find out if your potential site has an existing water meter to hook in to. Call your water provider’s customer service department, and ask them to conduct a site investigation. They will need the same location information that you took with you to the tax assessor’s office. Existing access to water will make a critical difference in the expense of getting your project started.

Depending on the size of your garden site, you will need a 1⁄2-inch to 1-inch water meter. If there has been water service to the site in the past, it is relatively inexpensive to get a new water meter installed, if necessary. If there has never been water service to that site, it might cost much more for your water provider to install a lateral line from the street main to the site and install your new meter.

Once you have determined that your potential site is feasible, write a letter to the landowner asking for permission to use the property for a community garden. Be sure to mention to the landowner the value of the garden to the community and the fact that the gardeners will be responsible for keeping the site clean and weed-free (this saves landowners from maintaining the site or paying city weed abatement fees). Establish a term for use of the site, and prepare and negotiate a lease. Typically, groups lease garden sites from landowners for $1 per year. You should attempt to negotiate a lease for at least three years (or longer if the property owner is agreeable). Many landowners are worried about their liability for injuries that might occur at the garden. Therefore, you should include a simple “hold harmless” waiver in the lease and in gardener agreement forms. For more information on the lease, and the hold harmless waiver, see step 7, Leases and Liability.

Be prepared to purchase liability insurance to protect further the property owner (and yourself) should an accident occur at the garden. For more information on the liability insurance, see step 7.

It might be advisable to have the soil at the site tested for fertility pH and presence of heavy metals. Unfortunately there’s no national database of soil testing labs. (Want to start one?) So it’s best to contact your state’s agricultural Extension office for information about getting it done.

Landowners of potential garden sites might be concerned about their liability should someone be injured while working in the garden. Your group should be prepared to offer the landowner a lease with a “hold harmless” waiver. This “hold harmless” waiver can simply state that should one of the gardeners be injured as a result of negligence on the part of another gardener, the landowner is “held harmless” and will not be sued. Each gardener should be made aware of this waiver and should be required to sign an agreement in order to obtain a plot in the community garden. Landowners may also require that your group purchase liability insurance. (Note: if you affiliated with an organization, explore the opportunity of getting insurance through them.)

Community members should be involved in the planning, design, and setup of the garden. Before the design process begins, you should measure your site and make a simple, to-scale site map. Hold two or three garden design meetings at times when interested participants can attend. Make sure that group decisions are recorded in official minutes, or that someone takes accurate notes. This ensures that decisions made can be communicated to others, and progress will not be slowed. A great way to generate ideas and visualize the design is to use simple drawings or photos cut from garden magazines representing the different garden components — flower beds, compost bins, pathways, arbors, and so on —that can be moved around on the map as the group discusses layout.

Although there are exceptions to every rule, community gardens should almost always include:

While some start-up funds will be needed, you can also obtain donations of materials for your project. Community businesses might assist and provide anything from fencing to lumber to plants. The important thing is to ask.

Develop a letter that tells merchants about your project and why it’s important to the community. Attach your wish list, but be reasonable. Try to personalize this letter for each business you approach. Drop it off personally with the store manager, preferably with a couple of cute gardening kids in tow! Then, follow up by phone. Be patient, persistent, and polite. Your efforts will pay off with at least some of the businesses you approach.

Be sure to thank these key supporters and recognize them on your garden sign, at a garden grand opening, or other special event.

Money can be obtained through community fund-raisers such as car washes, craft and rummage sales, pancake breakfasts, and bake sales. They can also be obtained by writing grants, but be aware grant-writing efforts can take six months or longer to yield results, and you must have a fiscal sponsor or agent with tax-exempt 501(c)(3) status (such as a church or nonprofit corporation) that agrees to administer the funds.

If you have not yet formed a garden club, now is the time to do so. It’s also time to establish garden rules, develop a garden application form for those who wish to participate, set up a bank account, and determine what garden dues will be if these things have not already been done. This is also the time to begin having monthly meetings if you have not already done so. Also, if you haven’t already contacted your city councilperson, he or she can be helpful in many ways, including helping your group obtain city services such as trash pickup. Their staff can also help you with community organizing and soliciting for material donations.

Many new garden groups make the mistake of remaining in the planning, design, and fund-raising stage for an extended period of time. There is a fine line between planning well and overplanning. After several months of the initial research, designing, planning, and outreach efforts, group members will very likely be feeling frustrated and will begin to wonder if all their efforts will ever result in a garden. That’s why it’s important to plant something on your site as soon as possible. People need to see visible results or they will begin to lose interest. To keep the momentum going, initiate the following steps even if you are still seeking donations and funds for your project (but not until you have signed a lease and obtained insurance).

Clean up the Site. Schedule community workdays to clean up the site. How many workdays you need will depend on the size of the site and how much and what kind of debris are on-site.

Install the Irrigation System. Without water, you can’t grow anything. So get this key element in place as soon as possible. There are plenty of opportunities for community involvement, from digging trenches to laying PVC pipes.

Plant Something. Once you have water, there are many options for in-garden action. Stake out beds and pathways by marking them with stakes and twine. Mulch pathways. If your fence isn’t in yet, some people might still want to accept the risk of vandalism and get their plots started. You can also plant shade and fruit trees and begin to landscape the site. If you do not yet have a source of donated plants, or don’t wish to risk having them vandalized, plant annual flower seeds that will grow quickly and can be replaced later. (Note: Seeds for community and school gardens may be obtained through local gardening programs, feed stores, gardening stores. Look for heirloom varieties. Check with seedsavers.org.)

Continue to Build. Continually improve the garden as materials and funds become available.

Have a grand opening, barbecue, or some other fun event to give everyone who helped to make this happen a special thank-you. This is the time to give all those who gave donated materials or time a special certificate, bouquet, or other form of recognition.

All community gardens will experience problems somewhere along the way. Don’t get discouraged — get organized. The key to success for community gardens is not only preventing problems from ever occurring, but also working together to solve them when they do inevitably occur. In our experience, these are some of the most common problems that crop up in community gardens.

Vandalism. Most gardens experience occasional vandalism. The best action you can take is to replant immediately. Generally the vandals become bored after a while and stop. Good community outreach, especially to youth and the garden’s immediate neighbors, is also important. Don’t get too discouraged. It happens. Get over it and keep going. What about barbed wire or razor wire to make the garden more secure? Our advice: don’t. It’s bad for community relations, looks awful, and is sometimes illegal to install without a permit. If you need more physical deterrents to keep vandals out, plant bougainvillea or pyracantha along your fence and let their thorns do the trick!

Security. Invite the community officer from your local precinct to a garden meeting to get his or her suggestions on making the garden more secure. Community officers can also be a great help in solving problems with garden vandalism and dealing with drug dealers and gang members in the area.

Communication. Clear and well-enforced garden rules and a strong garden president can go a long way toward minimizing misunderstandings in the garden. But communication problems do arise. It’s the job of the garden club to resolve those issues. If something is not clearly spelled out in the rules, the membership can take a vote to add new rules or make modifications to existing rules. Language barriers are a very common source of misunderstandings. Garden club leadership should make every effort to have a translator at garden meetings where participants are bilingual. Perhaps a family member of one of the garden members who speaks the language will offer to help.

Trash. It’s important to get your compost system going right away and get some training for gardeners on how to use it. If gardeners don’t compost, large quantities of waste will begin to build up and create an eyesore and could hurt your relationships with neighbors and the property owner. Waste can also become a fire hazard. Make sure gardeners know how to sort trash properly, what to compost, and what to recycle. Trash cans placed in accessible areas are helpful to keep a neat and tidy garden.

Gardener DropOut. There has been, and probably always will be, a high rate of turnover in community gardens. Often, people sign up for plots, then don’t follow through. Remember, gardening is hard work for some people, especially in the heat of summer. Have a clause in your gardener agreement that states gardeners forfeit their right to their plot if they don’t plant it within one month, or if they don’t maintain it. While gardeners should be given every opportunity to follow through, if after several reminders nothing changes, it is time for the club to reassign the plot. Every year, the leadership should conduct a renewed community outreach campaign by contacting churches and other groups in the neighborhood to let them know about the garden and plots available.

Weeds. Gardeners tend to visit their plots less during the wintertime, and lower participation, combined with rain, tends to create a huge weed problem in January, February, and March. [Author note: Bear in mind that these suggestions were gleaned from a Los Angeles community garden group! Take this occasion to think about the geography-dependent seasonal challenges your garden might face.] Remember, part of your agreement with the landowner is that you will maintain the lot and keep weeds from taking over. In the late summer/early fall, provide gardeners with a workshop or printed material about what can be grown in a fall and winter garden. Also, schedule well in advance garden workdays for early spring, since you know you’ll need them at the end of winter. If you anticipate that plots will be untended during the winter, apply a thick layer of mulch or hay to the beds and paths.

Good luck with your community garden project!

— These steps were inspired by and adapted with permission from Community Garden Start-Up Guide, by Rachel Surls, University of California Cooperative Extension (UCCE) County Director, with the help of Chris Braswell and Laura Harris, Los Angeles Conservation Corps, updated March 2001 by Yvonne Savio, Common Ground Garden Program Manager, UCCE, © Regents of the University of California. Used by permission.

Community composting at a community garden is one aspect to reducing waste and costs at a garden. But what if you’re throwing organic waste into your household or business trash cans? Waste removal costs money, and it really is the definition of waste because all that potential is lost when that organic material is thrown into a landfill.

Some local food system entrepreneurs are digging the potential and making a buck doing it. Compost Community of Tallahassee is doing just that. According to its website (compostcommunity.org), for a nominal monthly fee, this organization will pick up organic waste from households or businesses; cultivate it into “the microbial life that will make it what it will be,” as Sundiata Ameh El, the owner/operator of Community Compost, puts it; and about six months later, nutrient-rich, beautiful compost is returned to those who participate. A win-win!

Check out the sketch below of the proposed East Feast Festival Beach Food Forest pilot project in Austin, Texas. Modeled after the Beacon Food Forest in Seattle, the proposal would see a little over two acres of land turned into an edible landscape, with fruit trees, a butterfly garden, kids’ play structures, a stormwater wetland filtration system, and other features.

Be a guerrilla gardener. Plant food in public spaces. A row of kale along the library. Climbing peas at the base of trees along the sidewalk. Grow food in that narrow piece of sad ground that’s between your lawn and the street, called the parkway, usually owned by the city. An act of art and rebellion, guerrilla gardening is not just about food to harvest. It’s about people. Community. Transform food and farming from the ordinary into the extraordinary.

Plant food gardens and fruit or nut trees in front of public buildings such as libraries, fire stations, and school administration buildings. Or work with local businesses to convert their grassy yards into rows of edible food. Food, not lawns (foodnotlawns.com).

“Gardening is the most therapeutic and defiant act you can do, especially in the inner city. Plus you get strawberries.”

Miguel A. Altieri, of the University of California, Berkeley, Department of Environmental Science, Policy, and Management (ESPM), gives the following definition:

Agroecology is a scientific discipline that uses ecological theory to study, design, manage and evaluate agricultural systems that are productive but also resource conserving. Agroecological research considers interactions of all important biophysical, technical and socioeconomic components of farming systems and regards these systems as the fundamental units of study, where mineral cycles, energy transformations, biological processes and socioeconomic relationships are analyzed as a whole in an interdisciplinary fashion.

— “What Is Agroecology?,” Agroecology in Action (agroeco.org)

With some salvaged building materials from the dump, a bunch of volunteers built a pilot shellfish aquaculture site in the late 1970s on the brackish shore of Lagoon Pond on Martha’s Vineyard. The innovation — to hire a biologist who would provide technical support to manage local shellfish stocks and develop shellfish aquaculture — was rallied around by the local shellfish constables. The nonprofit MV Shellfish Group (mvshellfishgroup.org) became the first public solar shellfish hatchery in the country in 1980 and has since spawned gazillions of shellfish, from oysters to sea scallops, quahogs, mussels, and the coveted bay scallop.

Shellfish, the “Vacuum Cleaners of the Sea” (to quote one of the group’s older posters), help clean the brackish waters of the degradations of development such as fertilizers, pesticides, and bacterial containments. And we eaters love our fresh oysters, steamers, and fried clams. Farming the sea, shellfish aquaculture, is an outstanding green local industry, providing jobs, cleaner water, and a culturally appropriate, delicious, fresh, whole food to the region. The MV Shellfish Group has also provided retraining for fishermen to transition into shellfishing and has worked on developing projects in other regions of the world, such as Zanzibar. And whenever the MV Shellfish Group holds a fund-raiser, there are lines out the door. These folks bring the best raw bar, and you’ll never beat them in a shucking contest.

For one out of every three bites of food we eat, we have pollinators such as honeybees to thank. And now more than ever we need healthy honeybee colonies.

Hold a honeybee community meeting. Invite beekeepers and want-to-be beekeepers. In every group of beekeepers there’s probably at least three answers to every question, but it’s important to share info about your specific locale.

Invest in an observation hive. It’s a great demonstration tool that can be, with care, taken to living local fests, agricultural fairs, and school classrooms.

Start a pollination program to complete a community garden, a farm, or a school garden, or just because you want good local, raw honey to eat. See Hold a Potluck with a Purpose for tips on finding your people and gathering to organize.

Find each other! Urban, rural, suburban farmers and beekeepers: you need each other. Farmers need healthy pollinators for crops, and beekeepers need land to set up hives or expand territories. To search, start with your nearest and dearest Extension agent(s). Go to the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s website (usda.gov). Search “Cooperative Extension System Office,” then search their map. Every state and territory has an Extension agent.

Plant your garden with medicinal and culinary herbs, edible flowers, and produce that bees will love. Here’s a list to get you curious. Grow in succession to keep bees happy all season long. Grow what you like to eat and what works in your plant zone.

Alethea is the author, with her husband, Mars, of Homegrown Honey Bees. Here is some of her excellent advice for would-be home-hivers. (For more, read the whole book!)

— Excerpted with permission from Homegrown Honey Bees (Storey Publishing, 2012) by Alethea Morrison and Mars Vilaubi

Before you even think about keeping bees in a densely populated neighborhood, determine your zoning district and ordinances and permitting requirements. These vary widely from town, to city, to state, so it’s really up to you to determine what you can and cannot do. If the cannots overwhelm, maybe you’ll be inspired to join a planning board to try to change things!

According to an article by Kristen M. Ploetz, Esq., in Modern Farmer magazine, some or all of the following are regulated by many zoning ordinances:

— Excerpted with permission from Modern Farmer, “Dear Modern Farmer, How Do I Legally Start an Urban Bee Hive?”

Laura Stewart, Max Wong, Sue Talbot, and Roberta Kato are friends, neighbors, and fellow associates in Backwards Beekeepers, an organization committed to taking beekeeping back to basics. Renouncing treatments of any kind and most management practices, such as feeding, requeening, and using foundation instead of letting the bees build natural comb, their motto is “Let the bees be bees!” This maxim expresses a strategy of letting colonies alone and the strongest will survive.

A key to the group’s success is that they capture native colonies of feral bees, which they’ve found to be more disease- and pest-resistant than commercial packages. Their bee-rescue hotline offers local residents and businesses a welcome service for capturing swarms that land on their property, and it provides an ample resource of free bees for people who want to start beekeeping or expand their apiaries.

— Excerpted with permission from Homegrown Honey Bees (Storey Publishing, 2012) by Alethea Morrison and Mars Vilaubi

Melinda Rabbitt DeFeo is an agriculture educator extraordinaire. She helped usher in Island Grown Schools from its inception and was the first IGS school coordinator to make the crucial leap from the nonprofit sector into the public school system as a paid educator — an outstanding sign that farm to school education had come a long way. She organizes and hosts the Edgartown School’s annual Garden Celebration Day, where she’s found that the observation beehive is the most requested activity by both kids and teachers.

I asked Melinda to share her advice and experience about how to introduce a live honeybee observation hive in the classroom. Here, in her own words, is her advice.

— Melinda Rabbitt DeFeo, sustainable agriculture educator

For more information about keeping an observation hive in a classroom, visit this nonprofit, Classroom Hives (classroomhives.org), formed by a group of educators who were so inspired by the Museum of Science’s observation hive that they not only introduced these types of hives into their classrooms but went on to develop this site to share their passion and experiences to inspire you to go out and safely introduce the fascinating world of beekeeping into schools. One of their best resources? The FAQ section that includes costs and how to maintain a hive in the summer vacation months. A must-read before you go to your administrators!

“Avoid insecticides that contain neonicotinoids, which potentially negatively affect honeybees and other pollinators.”

— Recommendation from A Review of Research into the Effects of Neonicotinoid Insecticides on Bees, with Recommendations for Action by Jennifer Hopwood, Mace Vaughan, Matthew Shepherd, David Biddinger, Eric Mader, Scott Hoffman Black, and Celeste Mazzacano

The nonprofit Xerces Society protects wildlife through the conservation of invertebrates and their habitat. Established in 1971, the society is at the forefront of invertebrate protection worldwide, harnessing the knowledge of scientists and the enthusiasm of citizens to implement conservation programs. Its resources include information about how to manage pesticides to protect bees, plant lists, and the Pollinator Conservation Resource Center — an interactive map to help you find resources specific to your geographic region.

Pollinators are essential to our environment. The ecological service they provide is necessary for the reproduction of over 85 percent of the world’s flowering plants, including more than two-thirds of the world’s crop species. The United States alone grows more than one hundred crops that either need or benefit from pollinators, and the economic value of these native pollinators is estimated at $3 billion per year.

— The Xerces Society (xerces.org)

Chicago’s O’Hare Airport planted a towerlike aeroponic system. Greens, herbs, and berries grow supported in towers, similarly to hydroponically grown plants except that the roots are misted rather than bathed in nutrient-rich water.

Roger Doiron is the founder and director of Kitchen Gardeners International (KGI), a Maine-based nonprofit network of over 30,000 individuals from 100 countries who are taking a hands-on approach to relocalizing the food supply. Here, Doiron goes through the basics of starting a kitchen garden of your own.

In its simplest form, a kitchen garden produces fresh fruits, vegetables, and herbs for delicious, healthy meals. A kitchen garden doesn’t have to be right outside the kitchen door, but the closer it is, the better. Think about it this way: the easier it is for you to get into the garden, the more likely it is that you will get tasty things out of it. Did you forget to add the chopped dill on your boiled red-skinned potatoes? No problem — it’s just steps away.

If you have to choose between a sunny spot or a close one, pick the sunny one. The best location for a new garden is one receiving full sun (at least six hours of direct sunlight per day), and one where the soil drains well. If no puddles remain a few hours after a good rain, you know your site drains well.

After you’ve figured out where the sun shines longest and strongest, your next task will be to define your kitchen garden goals. My first recommendation for new gardeners is to start small, tuck a few successes under your belt in year one, and scale up little by little.

But what if you’re really fired up about it? Even in year one, you may be able to meet a big chunk of your family’s produce needs. In the case of my garden in Scarborough, Maine, we have 1,500 square feet under cultivation, which yields enough to meet nearly half of my family of five’s produce needs for the year. When you do the garden math, it comes out to 300 square feet per person. More talented gardeners with more generous soils and climates are able to produce more food in less space, but maximizing production is not our only goal. We’re also trying to maximize pleasure and health, both our own and that of the garden. Kitchen gardens and gardeners thrive because of positive feedback loops. If your garden harvests taste good and make you feel good, you will feel more motivated to keep on growing.

If you’re starting your kitchen garden on a patch of lawn, you can build up from the ground with raised beds, or plant directly in the ground. Building raised beds is a good idea if your soil is poor or doesn’t drain well, and you like the look of containers made from wood, stone, or corrugated metal. This approach is usually more expensive, however, and requires more initial work than planting in the ground.

Whether you’re going with raised beds or planting directly in the ground, you’ll need to decide what to do with the sod. You can remove it and compost it, which is hard work, but ensures that you won’t have grass and weeds coming up in your garden. If you’re looking to start a small or medium-sized garden, it’s possible to cut and remove sod in neat strips using nothing more than a sharp spade and some back muscle. For removing grass from a larger area, consider renting a sod cutter.

The most important recommendation after “start small” is “start with what you like to eat.” This may go without saying, but I have seen first-year gardens that don’t reflect the eating habits of their growers — a recipe for disappointment. That said, I believe in experimenting with one or two new crops per year that aren’t necessarily favorites for the sake of having diversity in the garden and on our plates.

One of the easiest and most rewarding kitchen gardens is a simple salad garden. Lettuces and other greens don’t require much space or maintenance, and grow quickly. Consequently, they can produce multiple harvests in most parts of the country. If you plant a “cut-and-come-again” salad mix, you can grow 5 to 10 different salad varieties in a single row. And if you construct a cold frame (which can be cheap and easy if you use salvaged storm windows), you can grow some hearty salad greens year-round.

When it comes to natural flavor enhancers, nothing beats culinary herbs. Every year I grow standbys such as parsley, chives, sage, basil, tarragon, mint, rosemary, and thyme, but I also make an effort to try one or two new ones. One consequence of this approach is that I end up expanding my garden a little bit each year, but that’s okay, because my skills and gastronomy are expanding in equal measure, as are my sense of satisfaction and food security.

Next, sketch out a garden plan of what will be planted where, when, and how. To do this, you need to get familiar with the various edible crops and what they like in terms of space, water, soil fertility, and soil temperatures. KGI also has a new, interactive Vegetable Garden Planner that makes it super simple and fun to handle planning a kitchen garden.

When the time comes to plant your kitchen garden, you’ll need to decide which plants to start from seed and which to buy as transplants. Many gardeners choose to plant all of their crops from seed for a variety of reasons, including lower costs, greater selection, and the challenge and satisfaction of seeing a plant go from seed to soup bowl. But whether you’re a greenhorn or a green thumb, there’s no shame in buying seedlings. Doing so increases your chances of success, especially with crops such as eggplants, peppers, and tomatoes that require a long growing season.

After you’ve sown your seeds or planted your plants, introduce yourself to the kitchen gardener’s best friend, Mr. Mulch. Just about any organic matter you can get your hands on — straw, grass clippings, pine needles, shredded leaves, dead weeds that haven’t gone to seed — can be used as mulch. I bring in mulch from neighbors who would otherwise throw it away. Mulch plays three main roles: It deters weeds, helps retain moisture, and adds organic matter to the soil as it decays. I apply it to the pathways between my beds and around all of my plants.

Greene, cofounder of the Hudson Valley Seed Library, advises asking this question of your retail seed company: Can my seed dollars be traced back to biotech or pharmaceutical corporations? (Note, for example, that seeds from Seminis [seminis.com] are from Monsanto.)

Fruits and vegetables are made mostly of water, so you’ll need to make sure your plants are getting enough to drink. This is especially important for seedlings that haven’t developed a deep root structure. You’ll want to water them lightly every day or two. Once the crops are maturing, they need about an inch of water per week, and more in sandy soils or hot regions. If Mother Nature isn’t providing that amount of rain, you’ll need to water manually or with a drip irrigation system.

Sun and rain willing, fast growers such as radishes and salad greens will begin to produce crops as early as 20 to 30 days after planting. Check on them regularly so you get to harvest them before someone else does. In my garden, those “someones” include everything from the tiniest of bacteria to the largest of raccoons. Various protective barriers and organic products can deter pests and diseases, and if you have trouble with rabbits, deer, or other four-legged critters, your best defense may be a garden fence.

Getting the most pleasure and production from your garden comes from learning the beauty of succession planting. Rather than trying to “get your garden in” during one busy weekend, space your planting out over the course of several weeks by using short rows. Every time you harvest a row or pull one out that has stopped producing, try to plant a new one. Succession plantings lead to succession harvests spread out over several months — one of the key characteristics of a kitchen garden.

As you gain new confidence and skills, you can look for ways to incorporate perennials including asparagus and rhubarb into your edible landscape. And no discussion of kitchen gardens would be complete without mentioning flowers, which should be added from the start. Flowers add beauty and color to the garden and the kitchen table. They also attract beneficial insects while, in some cases, repelling undesirable ones.

— Excerpted with permission from Roger Doiron, Kitchen Gardeners International (kgi.org)

At my publisher, Storey Publishing, in North Adams, Massachusetts, employees regularly enjoy deliveries of bread, pizza, and cookies from a local bakery, as well as eggs, chickens, honey, and a variety of fruits from other producers. Workplace CSAs — in which nearby farms make an agreement to make deliveries to a workplace in exchange for a certain number of employees making a commitment to participate — can be a great deal for all involved. Farmers can have a lot of sales in one place, and employees don’t have to shop somewhere else after work.

Do you know local farmers, growers, and artisans who have goods to offer that would appeal to you and your co-workers? Usually it makes sense to take an informal poll among your co-workers, then approach the local farmer with a query. Could you bring 100 pounds of apples to our office next week? There are many ways to spin this: Maybe you’d like simply a one-off holiday pie delivery from a local bakery. Or maybe your workplace could sustain a regular weekly CSA delivery of a full range of veggies and fruits all year long.

You may want to check out these two farms, which have formal workplace CSA programs: Katchkie Farm, in Kinderhook, New York (katchkiefarm.com), and Cedarville Farm, in Bellingham, Washington (cedarvillefarm.com).

What if a state helped to offset costs for its employees to join CSAs? In 2013, building on a successful pilot project launched in three counties, Vermont expanded its Workplace Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) Program, which “enables Vermont state employees to conveniently purchase locally grown food and produce at numerous sites around Vermont.” According to the state website, nearly 75 percent of the state employees had never previously participated in a CSA, and most planned to re-enroll.

While this chapter on growing mostly focuses on small-scale farming — on backyard and community gardens and local CSAs — most of our food in this country is grown on a large industrial scale, and with the labor of unprotected migrant workers, many of whom are American citizens and school-age children.

Here are some troubling facts about the human cost behind our diet:

— Information from the film The Harvest/La Cosecha: The Story of the Children Who Feed America (theharvestfilm.com)

When you hear the words “farm” and “child,” with any luck you’ll think of a beautifully green school garden or that new farm to school program in the city down the highway. But the reality is that hundreds of thousands of children have their hands in the soil for more than 12 hours a day, in the occupation that the USDA calls the most hazardous one in existence. U. Roberto Romano’s heartrending film The Harvest/La Cosecha: The Story of the Children Who Feed America, focuses on the lives of United States citizen child migrant workers, many of whom face great health risks and barriers to an education because of the work they do. These kids drop out of school at four times the national rate. Why? Because we let them. Some facts:

— The Harvest/La Cosecha: The Story of the Children Who Feed America (theharvestfilm.com)

Screen the film The Harvest/La Cosecha. Invite high schools or college groups, politicians, business owners, and the local media. For tips on screening a film, see here.

There are many organizations dedicated to migrant farmworkers. Get involved!

We provide job training, pesticide safety education, emergency assistance, and an advocacy voice for the people who prepare and harvest our food. Many member organizations operate a variety of programs in addition to the U.S. Department of Labor’s National Farmworker Jobs Program, including Head Start, education, and housing counseling.

The AFOP also operates train the trainer pesticide safety programs for farmworkers. Funded by the United States Environmental Protection Agency, AFOP trains outreach workers in member agencies and related organizations in the Worker Protection Standard and in the latest techniques and materials. The trainers at the local level then conduct trainings for groups of farmworkers to help them understand and protect themselves from the dangers of pesticides. The program is now operational in 14 states. It is known as Project HOPE.

— The Association of Farmworker Opportunity Programs (afop.org)

The National Center for Farmworker Health (NCFH) is a private nonprofit corporation, established in 1975, located in Buda, Texas. NCFH provides information services, technical assistance, and training to more than 500 private and federally funded migrant health centers as well as other organizations and individuals serving the farmworker population.

— National Center for Farmworker Health (ncfh.org)

For more than 40 years, the Migrant Legal Action Program (MLAP) has provided legal representation and a national voice for migrant and seasonal farmworkers, the poorest group of working people in the United States.

MLAP works to enforce rights and to improve public policies affecting farmworkers’ working and housing conditions, education, health, nutrition, and general welfare. The program works with an extensive network of local service providers.

MLAP staff is actively involved in advocacy, including legislative and administrative representation. MLAP also provides extensive support to local migrant service providers through training, technical assistance, and other services.

— Migrant Legal Action Program (mlap.org)

The College Assistance Migrant Program (CAMP) is a unique federally funded educational support and scholarship program that helps more than 2,000 stu-dents annually from migrant and seasonal farmworking backgrounds to reach and succeed in college. Participants receive anywhere from $750 to $4,000 of financial support during their freshman year of college and ongoing academic support until their graduation.

— MigrantStudents.org (migrantstudents.org/scholarshipsources.html)

SAF works with farmworkers, students, and advocates in the Southeast and nationwide to create a more just agricultural system. Since 1992, we have engaged thousands of students, farmworker youth, and community members in the farmworker movement.

— Student Action with Farmworkers (saf-unite.org/node/3)

The Food Chain Workers Alliance is a coalition of worker-based organizations whose members plant, harvest, process, pack, transport, prepare, serve, and sell food, organizing to improve wages and working conditions for all workers along the food chain.

— Food Chain Workers Alliance (foodchainworkers.org)