6

Mental Illness before Guantánamo

Shayana Kadidal

“The petitioner[1] admitted that he was at Tora Bora, Afghanistan in December of 2001,” announced the government’s executive summary of its account of why our client should be detained. “Tora Bora became Usama bin Laden’s headquarters in November of 2001. The battle for Tora Bora lasted for two months,” it added, helpfully. Surprisingly, this accusation was buried way down in paragraph 34 of 35, but as it turned out, it was the hardest of the assortment of disconnected allegations against him to deal with.

Most were incredibly stupid: that he fought with Afghan forces during the post-Soviet conflict in 1994 (this was supposed to be a bad thing, just two years after the U.S. had sent Stinger missiles to various parties fighting the Russians?), that he was seen at some flophouse by some other detainee who was tortured when he made the claims, etc., etc.

So this Tora Bora thing was the main remaining accusation against him. We had to get rid of it.

* * *

There was a single source document for this accusation. It was an interrogation report of a conversation with our client in the summer of 2002. He had been arrested in front of his wife and infant child in a house in Lahore, the most sedate of Pakistan’s large cities, a stone’s throw from India and far from the wild western part of the country. From there he was taken to the detention and interrogation facility the U.S. had set up at Bagram Airfield Military Base in Afghanistan. The place was notorious for brutal interrogations; it was not long since 9/11, and the interrogators were largely young military kids out of their depth. Everyone there recalled being asked, “Where is Osama bin Laden?” even if they had been detained a world away from the last known whereabouts of the Al Qaeda leader in the mountains of Tora Bora.

The interrogation report of our client had just one line of substance. Our client had fled the fighting in Afghanistan after the U.S. invasion, and the report said that in doing so he “WANTED TO GO TO PAKISTAN, AND [HIS FRIEND] TOOK A TAXI WITH THE DETAINEE TO BORA, AF, AND THEN ON TO PESHAWAR.” Bora, Afghanistan. It might as well have had an exclamation point for emphasis, though that might have been redundant given that the whole document was in capital letters.

It was a rather spectacular allegation given what followed immediately after: “detainee has displayed severely nervous behavior, and tenses his hands and feet so his fingers and toes stick straight in the air. . . . Detainee claims he is possessed by the devil and it enters him through a mark on his leg. The devil enters him and ‘mixes things up.’ . . . Detainee is kept awake at night because Allah and the devil are fighting in his head.” Voices in the head, somatic delusions . . . an odd person to be kept in the trusted circle around UBL at Tora Bora, for sure. In reading all of this, I always picture a probably twentysomething interrogator disinclined to take any behavior at face value—but here’s what the interrogator wrote, after noting our client’s behaviors were consistent around both guards on the cell blocks and interrogators: “If the detainee is acting, he has been very convincing since he arrived at the facility. Recommendations: Detainee should be psychologically evaluated.”

That was a good recommendation. It seems to have never really been acted upon in the eight years he was held at GTMO.

* * *

Another (normally) good recommendation: talk to your client about what the real story might be.

Yet we never managed to have a conversation with him about the substance of any of the allegations the government made, no matter how outlandish. He would suddenly be rendered completely out of it the second the conversations turned to the details of the government’s claims, but that was at some level entirely typical for detainees for a variety of reasons—most often, anxiety at answering the same questions they’d been asked during early, brutal interrogations at Bagram, Kandahar, or Guantánamo. But this client started tapping his head every time we talked about the past, and soon after the tapping started, invariably he was unable to speak or function. Was it just anxiety, a block that we’d eventually get through together? Conscious avoidance that just appeared exactly the same as mental illness? (And why was I more skeptical than the skeptic who interviewed him in Bagram?) Or was he trying to shut down another voice in his head?

I met with him in a little meeting shed at Guantánamo in May 2009, telling him that we’d have to talk in some detail about all of this on the next visit. In mid-April I went down to Guantánamo again, and he wouldn’t come out to meet me. For a whole week. So I had no choice but to look for clues in the sterile record back stateside.

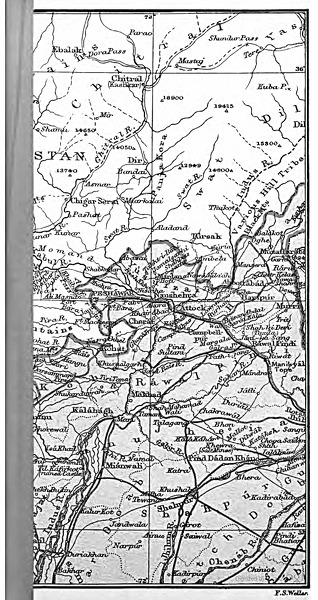

First off, it didn’t seem to make sense that anyone could take a taxi to Tora Bora, located high up in the White Mountains, a relatively impassable part of the border between Afghanistan and Pakistan, certainly way out of the way if you were heading to Peshawar. And there were references to a “Bara” (with two As, and no O) elsewhere in the early interrogation notes. So we looked for any Bara we could find. Maps were no help at first. But if our guy had taken a taxi from Jalalabad to Pakistan, the Khyber Pass was almost the only plausible route; it had been open to nonofficial traffic at various times even in the months directly after 9/11. And a straight line from Jalalabad over the pass led to Peshawar, the final destination of that cab ride. Could the Bara I was looking for be somewhere along that line? After weeks of looking, a clue—references in an old tourist book to a “Fort Bara”—led me to look on 19th-century maps. And then finally, on Google Books, there it was: Ft. Bara, built out by the British on what was then the western frontier of Imperial India. Now it was a suburb,2 long ago swallowed by the metastatic city of Peshawar, a place flush with refugees and migrants since the dictatorship of Zia ul Haq and perhaps long before then as well.

So he did indeed take a taxi from Jalalabad to Bara and then into Peshawar. But in the round of bin Laden bingo being played in all those early interrogations, “Bara” became “[Tora] Bora.”

In an opening scene of the Terry Gilliam/Tom Stoppard movie Brazil, there is a moment when a fly happens into the mechanism of a manual typewriter, causing the name of a suspected terrorist (“Tuttle”) to type out on a form as “Buttle.” A hapless cobbler, Archibald Buttle, is then detained by a party of storm troopers who raid his home, carving a hole in his ceiling, rappelling down through it, and whisking him away from his easy chair in front of the disbelieving eyes of his wife and children. In our case, the typo came after the fact, only taking on significance as the authorities tried to justify holding him for eight years. And the police, Pakistanis, probably didn’t drop out of a hole in the ceiling. But they did take him away in front of his wife and infant daughter. More on them later.

* * *

Unlike poor Buttle, who died in the interrogation chair, our client hadn’t been as horribly abused as the typical prisoner held at Bagram or Guantánamo. Even according to his own accounts he hadn’t been mistreated. They hadn’t even really seemed that interested in interrogating him much in his early days at GTMO, when just about everybody else we represented had been the subject of intense scrutiny. What did they believe his story was?

Apparently, after a brief window of observation by military medical teams, they decided that he wasn’t a hardened Muslim extremist terrorist, but actually fell into the other generic category of Guantánamo detainees that officialdom recognized: opiate addict. Now, thinking that someone who seems out of it, hears voices in his head, has tics that occasionally resemble shaking, etc., is a withdrawing heroin or opium addict might be excusable for a few days. But it’s odd to attribute this behavior to opiate withdrawal when it goes on for months and years, as it did for our client, because (as anyone who’s seen Trainspotting can tell you) opiate withdrawal symptoms last a few days at most. (Seventy-two hours is about the average.) Our client certainly wasn’t getting a fresh supply at GTMO. Yet this initial medical diagnosis—so obviously wrong—lasted forever, in classic military style. “Once an enemy combatant, forever an enemy combatant”; label someone a druggie on day one and there’s no need to bother treating them for, say, psychosis.

The century-old map on which I first saw the mythical place name “Bara.” Source: John Murray, A Handbook for Travelers in India, Burma and Ceylon (4th ed., Calcutta, 1901)

But the military’s definitive conclusion3 was reassuring in one sense. The government seemed generally incapable of believing that the prisoners it had purchased from various proxies—Afghan warlords, corrupt Pakistani police, hungry villagers—had innocent reasons for being in the region. But if they labeled someone a druggie, that was sort of a signal that they believed your guy wasn’t a fundamentalist. They thought he wasn’t a proper Muslim? Couldn’t be a bad thing.

* * *

As it turned out they were wrong about his religious belief too. He’d grown up in Libya, in a large family—one of ten siblings. He’d been drafted into the military at 19, but right around that age (the classic time frame for psychotic breaks) he’d started to develop his symptoms. They got worse and then Gaddafi started a war with Chad. He fled the country, fell in with a bunch of exiles, and ended up shuttling for a decade between western Pakistan and Afghanistan.

Other than the folks at GTMO who decided he was a junkie (and did nothing in response), he had never had any exposure to Western psychiatry, never received any medication.

He had exposure to me. But despite my best intentions as an undergrad pre-med, I was not a psychiatrist. I did, however, have a phone card that let you connect to the mainland from Guantánamo for 20 cents a minute on a government-monitored line, and so I used the time freed up by our client’s unwillingness to come out and meet in April 2009 to find and consult with a wonderful Arabic-speaking psychiatrist at the medical school of the University of California, San Francisco. Talking to him, the pieces started to connect: in much of the Arab world, either there is no physical access to Western psychiatry or common people lack the financial ability to take advantage of whatever resources are available locally. So upon the onset of psychosis, concerned parents take their children to the only help accessible to them: faith healers. The diagnosis is typically couched in religious terms: the young man “has the Djinn,” or, in other words, is possessed by a devilish spirit. And the consultations invariably result in a simple, low-cost prescription: “pray more.” Who wouldn’t follow that advice? So our client became far more devout than his brothers and sisters, something that was eventually marked with all the outward signs—he grew a beard, read Koran to himself when the outside world became overwhelming, and so forth.

The contrast with his siblings, all mostly secular, was striking enough that he himself had noted it. Plenty of men I’ve met at GTMO are from highly secular families, relative to their larger community; for several, they stood out because in their adolescence they either had a psychotic break (the typical age of onset being roughly 18 to 24) or they lost their mother during that vulnerable period. And either the illness drove them to religion, or, seemingly, they embraced it in the void left by the absent parent.

Perhaps this pattern, where the onset of mental illness leads to increased religiosity, will change as time passes and pharmaceuticals become more widely available and cheaper. But there are obviously a lot of forms of resistance to the very concept of mental illness that may continue to draw people from every culture to understand its symptoms in other terms. Ironically, one of the few reliable tools for confirming a diagnosis of psychosis is to treat the patient with the drugs that that form of psychosis usually responds to and see if things change. The magical effect of psychotropic drugs has convinced many a parent that their child’s uncanny symptoms were in fact physiological in origin.

At Guantánamo, the ritual you go through when a client won’t come out and meet you is pretty routine. You take the ferry from the empty side of the base, where pesky human rights lawyers are warehoused overnight, to the windward side of the base, where some 11,000 troops and the prisoners are kept. (The vast majority of those troops have nothing to do with detainee operations.) You spend an hour and a half entering the camps, and along the way the military escorts inform you the client has refused his meeting. You write a short note on half of one side of paper and have your translator render it into Arabic. A military lawyer takes the note back to the cell and returns telling you either that it worked, or that the client still refuses (or sometimes, more troublingly, that the client refused to read the note or have it read to him). Unlike in regular prisons, even with mentally ill patients one isn’t allowed to enter the cell block and walk up to the front of your client’s cell and confirm his understanding of what’s happening or at least have a chance to observe his physical and psychological condition briefly in person. (Nor has there been any success to date in getting the courts to order outside doctors into the prison to treat mentally ill clients; again, administering drugs is sometimes the quickest way to confirm a diagnosis of psychosis.)

Instead, you head back on the ferry to the hotel. Oddly, for five days straight during that April 2009 trip when our client wouldn’t come out to talk, I noticed a small bump on my elbow gradually swell up to the point where it was clear something was wrong. Spending the day musing over the lack of proper mental health care for Guantánamo prisoners made me not want to try my own luck with the health clinic there. In retrospect, like many decisions to avoid medical intervention, this was a bad choice: eventually the bump got to be the size of a ping pong ball and was surgically cut out of my arm; only now, five years later, is the scar finally starting to disappear. But for the first two months afterward I was on Cipro, sick, trekking almost daily to a well-hidden Defense Department office in dystopian Crystal City, Virginia, to work on our classified court filings on behalf of this client.

This place—the “Secure Facility”—feels more isolated to me than being down at the empty side of Guantánamo. Like meeting rooms (and cell blocks, I am told) at GTMO, it is frigid and devoid of natural sunlight, and, ironically, I generally subsist while working there on meals from the local Afghan Kebab House. The Facility occupies one corner of a commercial office building, and, as far as I could tell, there was only one thermostat on each floor of the building, located in another office that didn’t have its shades drawn all day (to prevent leaks by telescope, surely). I’m guessing that the comfortable air conditioning in the adjacent offices was rendered freezing in the Facility by the absence of the heat of the sun. I spent most of the next two months there, drafting papers from morning to night. The day we filed the 290th page of classified briefing in the case, I opened my email on my BlackBerry and saw that that morning the government had notified us that our client had been cleared for transfer out of Guantánamo.

* * *

This was not the first time in the history of the legal profession that a huge mound of paper was consumed in vain. Nor was it the first time our client was cleared. In 2007, the Bush administration had also cleared him, but to be released to Libya, where he was certain he would be tortured as a beard-wearing, presumptive Islamic militant extremist who’d surely been in Afghanistan just biding the decades whilst plotting to overthrow Gaddafi. Whether he was or wasn’t mentally ill when he absconded from military service during that long-ago war with Chad wasn’t going to matter one bit.

In the spring and summer of 2007, we had tried to get the courts to intervene on an emergency basis to stop him being sent to what we felt certain would be a horrible death in Gaddafi’s jails. We ended up filing legal requests all the way up to the Supreme Court. All of the paperwork was in vain; none of the courts wanted to touch the issue. So for all CCR’s work on his case, the thing that saved his life was a photograph.

When the bombing in Afghanistan started in late 2001, as the U.S. prepared the way for its allies to take the country back from the Taliban, our client had crossed the border separately from his wife and infant child. His wife was an Afghan and, of course, a woman; with an infant child in tow, she would invariably have an easier time getting across the border than an able-bodied, recognizably foreign man would. They all made it across and were reunited in Lahore, far from any conflict, and lived in a house with some other exiles until Pakistani police showed up to arrest him. (More Guantánamo prisoners were arrested in Pakistan than in Afghanistan, helping Musharraf rack up millions of dollars in bounty payments.) After that, she returned with their daughter to live with her family in their village in rural Afghanistan.

The Afghan Human Rights Organization (AHRO) somehow tracked her down there during our client’s asylum crisis in 2007. His wife and child made the long trip to AHRO’s offices in Kabul, from where they emailed us a photograph of a sad-eyed little girl, recognizably our client’s child, holding up a small wrinkled photograph of her father. Next to her sat her mother, eyes downcast to the floor but with her veil pulled back to show her face.

The next day we had a brief phone call to ask permission to use the photo in public advocacy to stop our client from being sent back to Libya. We presumed it would be a difficult discussion, but it was not. His wife agreed. With Human Rights Watch working behind the scenes to make it happen, the Washington Post ran a story about the situation, featuring the photo, and before two weeks had passed, word got to us that the State Department would block our client’s repatriation.

That phone call was almost the last we ever heard from her. Our client was eventually released to Albania and granted refugee status there in 2010. Afterward, we spent years trying to connect the two of them, but as quickly as his wife was found in 2007, she managed to not be found after he was out. Perhaps she was fearful that custody of her daughter would become an issue. One condition of almost all releases from Guantánamo, even to places where men have been taken as refugees from their countries of birth, is that they not be allowed to travel freely internationally, and there seemed to be no chance that they would ever be reunited in Afghanistan.

Our client’s wife and daughter, holding a crumpled photo of her father. (As it worked out, this photo might be the last he ever saw of them.) Source: CCR/AHRO

* * *

I never had any idea what that marriage might have been like for her. They didn’t speak the same language. He frequently expressed that she was a nice woman and he wished he could have done more for her. But surely his illness was a mutual burden.

Nor did we (despite our sacred relationship, attorney and client) ever have the slightest connection. Most of the time it was like he was trapped in a box in his head, even after he got out of Guantánamo. After he was sent to Albania, he spent most of his time outside his room playing football with the wary Kosovar refugee kids in the refugee center where he was held for his first few months of freedom. Later he got an apartment (paid for by the state), and, eventually, two kittens.

Albania was a miserable place for him. As an underdeveloped former Eastern bloc country, social services there were far less well funded than elsewhere in Western Europe where other Guantánamo refugees had been sent—a fact of which those sent to Albania were all aware, thanks to the Internet (high-speed connections being one of the few luxury perks those ex-detainees had). In the refugee center in Albania the detainees experienced cold (natural cold—not the cold from the air conditioners at GTMO, which were always on high for the layered-up guards) for the first time in decades, with only the thin prison smocks from Guantánamo that they still wore to protect them. The refugee authorities gave them propane burner heaters, but they had to ration out the canisters, so the three men would sit in a circle between their three heaters, sharing this as they had shared everything in the prison for years.

None of the clothes they were offered by the authorities fit. We flew there to be there with them during their first week. After a day, we bought them clothes, although Albania, like Williamsburg, Brooklyn, is a land of tight-fitting jeans, and these were all big men who were used to things fitting loosely. We promised to send back more from the land of XXL, the United States, but they were skeptical. Finally, I snuck in a DSLR camera to take pictures of them—without flash, as that would have given us away—to send to their parents, who hadn’t seen them in years. (This was before the International Committee of the Red Cross routinely started being allowed to take and send home glossies from Guantánamo.) I took over a hundred pictures of our client’s two companions. But he did not want any pictures of himself made, thinking he didn’t look well. He was right about that.

Another thing not routinely available in Albania was quality mental health care. Though we had tried to impress on the State Department that our man should be resettled in a country with modern psychiatric care—Finland was one place high on our wish list—they claimed the burden of taking care of him was too daunting for the countries that were actually capable of doing it to want to take him. Albania was pliant, willing to take anyone rejected by the rest of Europe, but unable to care for them. In Albania, most working locals didn’t have adequate health care. And as to psychiatry, as one local psychiatrist who’d worked with Yugoslav civil war refugees put it, it was mostly “Soviet style”: if you were labeled as “mentally ill,” you’d end up hospitalized and put on Haldol or some other overwhelmingly powerful drug, turned into a zombie and forgotten. The middle ground between that and neurosis was not an acknowledged category. So even seeking local treatment seemed fraught with danger (putting to one side that the local language was impenetrable—exceptionally hard to learn by reputation, the sole surviving offshoot from ancient Illyrian on the modern-language family tree).

At great effort, our Arabic-speaking psychiatrist and a fellow native-speaker colleague from Montreal both volunteered to treat him, traveling from North America to Tirana on their own time. A year after his release, they found him severely depressed but improved to the point that they wondered whether their initial suspicions of psychosis were correct. That was encouraging news, though later we started to believe they had caught him during a good month. We had hoped to get him more advanced care than what was on offer in Albania—most likely involving medication as well as talk therapy, which he sometimes found useful and sometimes found absurd. But eventually Gaddafi was overthrown, and he went home to his family in Libya, where his story began.

Notes

1 I have chosen not to identify our client by name here given the personal nature of some of parts of his story. He gave us proxy to use his story in our advocacy efforts on behalf of the men still at Guantánamo, and, for her part, many years earlier his wife did as well.

2 To make sure it would continue to be acknowledged as a real place, I immediately did what every college student would do—I created a Wikipedia page for it: “Bara, FATA,” available at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bara,_FATA.

3 It’s worth noting that, depending on what the military was trying to rationalize at the moment, the government occasionally did acknowledge his mental illness. So, in trying to justify his continued detention, his Combatant Status Review Tribunal noted, “Detainee was previously treated for psychosis but now is in good health” (!), and from there somehow concluded, “Detainee’s psychological issues allow him to be easily influenced by extremist groups, who may utilize him for his talents, and who may possibly recruit him to act as a martyr, should he be released; therefore, it is imperative detainee be retained in the custody of the U.S. Government or the Libyan Government.” His documents from the Administrative Review Board, set up under President Bush to determine whether Guantánamo detainees should continue to be held, likewise refer to a “schizotypal personality disorder.”