6

JOHANN FRIEDRICH BLUMENBACH NAMES WHITE PEOPLE “CAUCASIAN”

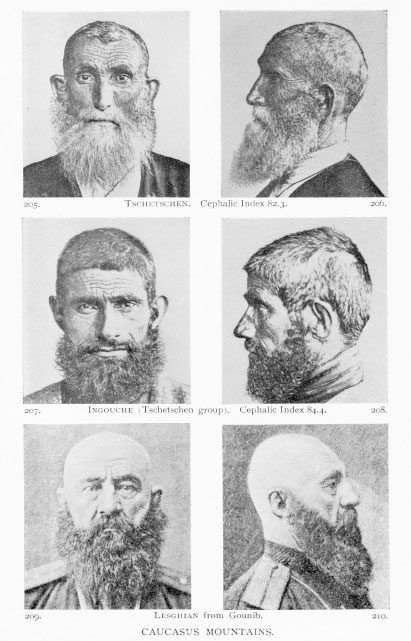

A reader might sensibly wonder why the social sciences, the criminal justice system, and, indeed, much of the English-speaking world label white people “Caucasian.” Why should this category have sprung from a troublesome, mountainous, borderland just north of Turkey, from peoples perpetually at war with Russia in the present-day regions of Chechnya, Stavropol Kray, Dagestan, Ingushetia, North Ossetia, South Ossetia, and Georgia? The long story begins in Göttingen, Lower Saxony, in 1795, and the better-known part of it belongs to Johann Friedrich Blumenbach. (See figure 6.1, Johann Friedrich Blumenbach.)

Blumenbach (1752–1840) was born into a well-connected, academic family in the east central German region of Thuringia. Recognized as a prodigy by age sixteen in 1768, he delivered a flattering address to an influential audience on the occasion of the local duke’s birthday, thereby opening the way to further recognition. Seven years later, his 1775 Göttingen doctoral dissertation, De generis humani varietate nativa (On the Natural Variety of Mankind), only fifteen pages long in revision, was the fruit of a year’s study with an older professor who owned an extraordinarily large and disordered natural history collection. De generis humani went into several editions and made Blumenbach both a medical doctor and an instant star in the German academic firmament.* Now in his mid-twenties, he quickly joined the faculty of the Georg-August University at Göttingen, the most prestigious center of modern education for young German nobles. Much sought after as an intellectual mentor, Blumenbach taught a bevy of aristocrats and other privileged men, including three English princes, the crown prince of Bavaria, and the scholarly, aristocratic brothers Wilhelm and Alexander von Humboldt.1

Fig. 6.1. Johann Friedrich Blumenbach in 1825, Katalog, Commercivm Epistolicvm J. F. Blvmenbachii. Niedersächsische Staats-und Universitätsbibliothek, Göttingen, Germany.

The university in Lower Saxony (whose capital was Hanover) offered not only the most up-to-date scholarship but also an opening to the educated, English-speaking world, for Hanoverians ruled Britain in the eighteenth century. Thus Göttingen’s situation accounts for a good part of the rapid spread of Blumenbach’s ideas.†

Maintaining the status of a world-renowned scholar demanded more than profound thinking on important topics such as the place of humankind in nature. It also required influential contacts, honors, the backing of strong institutions, and something to show off—for instance, a collection of skulls or a royal garden. In the two generations preceding Blumenbach, the greatest European naturalists had tended royal gardens—Carolus Linnaeus in Uppsala, Sweden, and Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon, in Paris, France, offer two prominent examples. In a sense, Blumenbach’s garden was his collection of human skulls. And he knew how to cultivate his learned connections.

Scholarly networking explains Blumenbach’s dedication of the third edition of On the Natural Variety of Mankind to the immensely rich and powerful English wool merchant naturalist Sir Joseph Banks (1740–1820), someone he hardly knew. Blumenbach thanks Banks fulsomely for skulls and other precious scientific items and for his hospitality in London in 1792. As president of the Royal Society, Banks ruled the natural history establishment of the day, dominating worldwide scientific exploration.2 Blumenbach’s dedication to Banks was intended to cement this tie between a humble researcher in Göttingen (still a provincial town compared with London and Paris) and a sovereign in Europe’s scientific kingdom. For Blumenbach, corresponding with Banks not only bolstered his standing as a scientist with international connections; it also eased the way for requests to Banks for exotic skulls and other specimens Banks controlled.

Among Banks’s many sponsorships was his support of the collection of the unique plant and animal specimens gathered during Captain James Cook’s second voyage (1772–75) to the bay in newly discovered Australia that Cook named Botany. Blumenbach coveted these rare specimens for his collection, but without success. In 1783 he initiated a correspondence (in French) with Banks, sending him information on German plants. Blumenbach soon joined the legions of pilgrims to Banks’s home and his vast scientific collection. In a 1787 letter back to Blumenbach, Banks explains the impossibility of sending Blumenbach a skull from the South Sea, because Petrus Camper in the Netherlands has an earlier claim.3 But Blumenbach was not easily deterred. By dint of persistent correspondence in French and then in English, he finally wangled a South Seas skull out of Banks, who sharply reminded Blumenbach of the difficulty of wresting body parts from native peoples. At any rate, continuing to flatter the most powerful figure in late eighteenth-century natural history, Blumenbach proclaimed the South Seas skull as representative of a new variety—the Malay—and placed it between the beautiful Caucasian and the ugly Mongolian. Thus Blumenbach’s 1795 dedication to Banks both cemented a western European alliance and made an offering to a god of science. By the end of his life Blumenbach owned Europe’s greatest collection—he called it his “Golgotha”—245 whole skulls and fragments and two mummies.4*

Blumenbach was no firebrand. He worked along strictly scientific lines of the time, advancing the burgeoning science of human taxonomy in two important aspects. First, he eliminated the popular and long-standing classification of monsters (including diseased people) as separate human varieties, a category that had appeared even in the otherwise solid work of Linnaeus.† Second, he used what he and his peers saw as a complete and scientific means of classification: in addition to the now commonly accepted index of skin color, he factored in a series of other bodily measurements, notably of skulls.

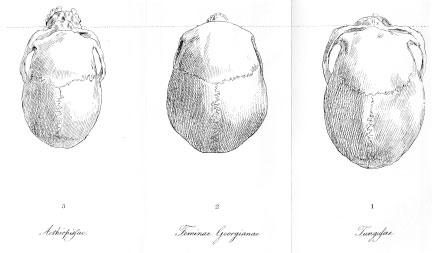

Unlike Petrus Camper, Blumenbach measured skulls in a number of ways, inaugurating a mania for ever more elaborate measurement. Placing scores of human skulls from around the world in a line and measuring the height of the foreheads, the size and angle of the jawbone, the angle of the teeth, the eye sockets, the nasal bones, and also Camper’s facial angle, Blumenbach came up with what he called the norma verticalis.5 (See figure 6.2, Blumenbach’s norma verticalis.) Adding skin color to the norma verticalis, he classified the single species of human beings into four and then five “varieties.” As we shall see, such meticulous measurement endowed the “Caucasian” variety with an unimpeachable scientific pedigree.

The first edition of On the Natural Variety of Mankind (1775) has many strengths. For one thing, it corrects a serious misconception about differences between various peoples. Climate, Blumenbach says—reasonably but in contradiction to others—produces differences in skin color, so that dark-colored people live in hot places and light-colored people live in cold places, a fact noted in antiquity but subsequently acknowledged only intermittently in the scholarly literature. He reminds readers that all individual human bodies contain lighter and darker places. The genitals, for instance, of light-colored people may be dark, and outdoor work darkens even people with light skin. Poor people who work outside become darker, and European skin becomes lighter in winter: “our own experience teaches us every year, when in spring very elegant and delicate women show a most brilliant whiteness of skin, contracted by the indoor life of winter.” If those women are careless and go into the summer sun and air, they lose “that vernal beauty before the arrival of the next autumn, and become sensibly browner.”6

Fig. 6.2. Blumenbach’s norma verticalis: Ethiopian, female Georgian, Asian, The Anthropological Treatises of Johann Friedrich Blumenbach, trans. Thomas Bendyshe, 1865.

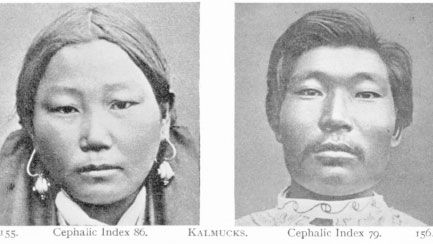

Blumenbach also cautions against drawing conclusions about whole peoples on the basis of only a small sample, a warning unfortunately not heeded, as the world of anthropology invariably continued to speak of human “types” embodied in the image of one single person. Take as an example the aforementioned Kalmucks of the northeastern Caucasus and western Asian regions, says Blumenbach. Well aware of the stereotype of Kalmucks as epitomes of ugliness, he warns us quite properly that one traveler’s drawing of an ugly Kalmuck’s skull cannot sustain conclusions about the group as a whole.

Blumenbach imagines that another traveler might describe Kalmuck men as beautiful, even as symmetrical, and conclude that their young women “would find admirers in cultivated Europe.”7 Blumenbach’s allusion to young women’s sexual attractiveness to European men evokes a gauge common among European travelers and scholars as far back as François Bernier in the seventeenth century. The French naturalist Buffon, for instance, pronounced Kalmucks the ugliest of peoples, the women as ugly as the men, but Circassians and Georgians the beautiful wives of eastern sultans.8

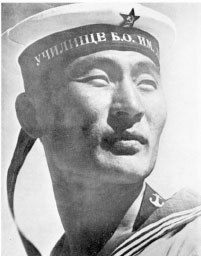

As we are seeing, Kalmucks remained salient exemplars of homeliness well into the nineteenth century. However, photographs from William Z. Ripley’s 1899 Races of Europe and Corliss Lamont’s Peoples of the Soviet Union of 1946 show two rather ordinary Kalmucks and a handsome one. (See figure 6.3, Ripley’s Kalmucks, and figure 6.4, Lamont’s Kalmyk Sailor.) Thus assumptions about the beautiful or the ugly pertained more to ideas than to actual physical appearance. As we have also seen regarding Circassians, Caucasians, and Georgians, the notion of their surpassing beauty became codified more by repetition than by any circulation of actual images of real people.

Like other race theorists, Blumenbach walked a tightrope between contradictions. On the one hand, he held fast to the prominent role that culture and climate play in determining outward appearance. Even so, he believed that certain groups maintain their distinctive physical and cultural characteristics over successive generations. Among the people of Europe, say, the Swiss retain their open countenance; the Turks remain manly and serious; the people of the far north keep their simple and guileless look; and, despite long residence among Gentiles, “the Jewish race presents the most notorious and least deceptive [example], which can easily be recognized everywhere by their eyes alone, which breathe of the East.”9 This last statement, delivered as scientific fact, turns up throughout racial science, deathless as the worship of the beautiful Caucasian/Circassian/Georgian.

Fig. 6.3. “Mongol Types,” Kalmucks, in William Z. Ripley, The Races of Europe (1899).

Fig. 6.4. “A Kalmyk Sailor,” in Corliss Lamont, The Peoples of the Soviet Union (1946).

ALL OF this classification appears in Blumenbach’s first edition.

Revising On the Natural Variety of Mankind in 1781, he adds the newly discovered Malays, thereby introducing a fivefold categorization. Note, however, that Europeans are not yet labeled Caucasian. Blumenbach explains that five groups, termed “varieties,” are “more consonant to nature” than the four Linnaeus had enumerated and that Blumenbach had originally accepted.* In 1781 Blumenbach also returns to the problem of the Lapps, finally admitting them as Europeans of Finnish origin, “white in colour, and if compared with the rest, beautiful in form.”10 As Europeans continued to discover ever more human communities, increasing numbers of peoples and their geographical boundaries aggravated the chaos of classification. Blumenbach revised once again.

In his third edition, published on 11 April 1795, Blumenbach does not increase the number of human varieties. But he gamely notes the existence of twelve competing schemes of human taxonomy and invites the reader to “choose which of them he likes best.” Three experts, including his Göttingen colleague Christoph Meiners, designate two varieties (Meiners’s were “handsome” and “ugly”); one posits three; six designate four; one, Buffon, speaks of six varieties (Lapp or polar, Tatar, South Asian, European, Ethiopian, and American); and one designates seven.11 Such anarchy had dogged human taxonomy from the beginning, for scholars could never agree on how many varieties of people existed, where the boundaries between them lay, and which physical traits counted in separating them. Nor have two hundred and more years of racial inquiry diminished confusion on this issue. Blumenbach’s idea of five varieties gained acceptance, but it was his introduction of aesthetic judgments into classification in 1795 that gave us the term “Caucasian.”12

BY 1795, twenty years had passed since the first publication of On the Natural Variety of Mankind. In the interim, skin color, not heretofore the crucial factor for Blumenbach, had risen to play a large role. He now sees it necessary to rank skin color hierarchically, beginning, not surprisingly, with white. Believing it to be the oldest variety of man, he puts it in “the first place.” His reckoning includes a large dose of aesthetic reasoning, led by the blush.* “1. The white colour holds the first place, such as is that of most European peoples. The redness of the cheeks in this variety is almost peculiar to it: at all events it is but seldom to be seen in the rest.” After white comes “the yellow, olive-tinge.” Then, third, “copper colour (Fr. bronzé)” fourth is “Tawny (Fr. basané)” last, “the tawny-black, up to almost a pitchy blackness (jet-black).”13 Like the first and second editions, this third edition of On the Natural Variety of Mankind keeps on ascribing differences of skin color to climate and individual experience in non-Europeans as well as Europeans.

Blumenbach seems once again to be arguing with himself, disregarding his own equitable explanation of individual difference and yet describing the “racial face” of each of his five human varieties. He dwells longest and lovingly on the Caucasian, from whom Lapps, having in 1781 been allowed a place, are once again excluded:

Caucasian variety. Colour white, cheeks rosy; hair brown or chestnut-colored; head subglobular; face oval, straight, its parts moderately defined, forehead smooth, nose narrow, slightly hooked, mouth small. The primary teeth placed perpendicularly to each jaw; the lips (especially the lower one) moderately open, the chin full and rounded. In general, that kind of appearance which according to our opinion of symmetry, we consider most handsome and becoming. To this first variety belong the inhabitants of Europe (except the Lapps and the remaining descendants of the Finns) and those of Eastern Asia, as far as the river Obi, the Caspian Sea and the Ganges; and lastly, those of Northern Africa.14

Like many other anthropologists, Blumenbach labels North Africans “Caucasian.” No problem there, at least not for the moment. But by placing the Caucasian variety’s eastern boundaries farther to the east than the Ural Mountains and as far south as the Ganges, Blumenbach enlarges Caucasian territory beyond the limits then becoming accepted as European.* Russia, always a problem, was sometimes placed within, sometimes outside Europe.

By bringing India into the Caucasian fold, Blumenbach was doubtless thinking linguistically. In 1786, the linguist Sir William Jones had traced similarities in various European and Asian languages to the archaic language of Sanskrit. Blumenbach’s colleague and friend Georg Forster had translated Jones’s version of an ancient Sanskrit classic drama into German in 1791. Others soon transformed a linguistic category, the Indo-European, or Aryan, into a race, giving rise to the idea of a biologically determined Indo-European people. By the mid-nineteenth century, scrupulous scholars had rejected any biological basis to the Indo-European/Aryan language group, but that hardly mattered. The judgment of sound scholarship did not suffice to kill off the notion of an Indo-European/Aryan race, with Germans and Greeks within and Semites outside. For determined racists, especially in the twentieth century, racial identity and language always had to coincide, and appearance would always figure in concepts of race. Race begat beauty, and even scientists succumbed to desire.

WITH THE concept of human beauty as a scientifically certified racial trait, we come to a crucial turning point in the history of white people. Now linking “Caucasian” firmly to beauty, Blumenbach remained divided of mind. Holding first place in his classification was always the scientific measurement of skulls. But second within human variety came a concern for physical beauty, going well beyond the beauty of skulls and giving birth to a powerful word in race thinking: “Caucasian variety. I have taken the name of this variety from Mount Caucasus, both because its neighborhood, and especially its southern slope, produces the most beautiful race of men, I mean the Georgian.” A long footnote follows, quoting the seventeenth-century traveler Jean Chardin as only one of a “cloud of eye-witnesses” praising the beauty of Georgian women. Blumenbach’s quote leaves out Chardin’s disapproval of Georgians’ heavy use of makeup, their sensuality, and the many bad habits Chardin had deplored. Now Chardin intones to Blumenbach the gospel of Georgian beauty:

The blood of Georgia is the best of the East, and perhaps in the world. I have not observed a single ugly face in that country, in either sex; but I have seen angelical ones. Nature has there lavished upon the women beauties which are not to be seen elsewhere. I consider it to be impossible to look at them without loving them. It would be impossible to point to more charming visages, or better figures, than those of the Georgians.15

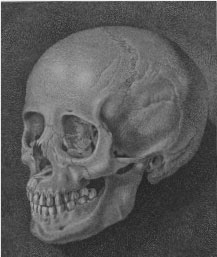

Beauty’s charms reached into science, but what of science’s bedrock, the measurement of skulls?

Now Blumenbach squirms. By turns he embraces Enlightenment science—the measurements of his skulls—then lets go to reach for romanticism’s subjective passion for beauty. Yes, skull measurements count, but when it comes down to it, bodily beauty counts for more, but no, no, not conclusively. Even while extolling Caucasian beauty, he adopts a third line of reasoning meant to puncture European racial chauvinism. Consider the toads, says Blumenbach: “If a toad could speak and were asked which was the loveliest creature upon god’s earth, it would say simpering, that modesty forbad it to give a real opinion on that point.”16 As in the first edition of On the Natural Variety of Mankind, Blumenbach qualifies his estimation of European beauty as rife with European narcissism.

Even so, he uses the word “beautiful” five times on one page in describing the bony foundation of his favorite typology, a Georgian woman’s skull. It is “my beautiful typical head of a young Georgian female [which] always of itself attracts every eye, however little observant.* (See figure 6.5, Blumenbach’s “Beautiful Skull.”)

THE STORY of Blumenbach’s skull belongs within a long and sorry history of Caucasian vulnerability to eighteenth-century Russian imperialism. Blumenbach’s benefactor Georg Thomas (Egor Fedotvich), Baron von Asch (1729–1807), is little known today. Born in St. Petersburg of German parents, Asch had secured his medical degree from the University of Göttingen in 1750 and then joined the Russian army’s medical service in the imperial forces of Catherine the Great. A military man and a leader of Russia’s learned societies in St. Petersburg and Moscow, Asch traveled around the expanding Russian empire both in his official capacity and as a patron of science. Regarding the latter, he collected skulls, manuscripts, and various other trophies from throughout Russia and its hinterlands in the 1780s and 1790s, specimens he showered on Blumenbach and the research collections of his Göttingen alma mater.*

Fig. 6.5. Blumenbach’s “Beautiful Skull of a Female Georgian.”

In 1793, shortly after Catherine had won her second Caucasian war against the Ottomans, Asch sent Blumenbach a pristine female skull, explaining its provenance in a cover letter.17 The skull came from a Georgian woman the Russian forces had taken captive, precisely the kind of situation figuring in so many descriptions of beautiful Caucasian and Circassian women: as an archetype, she is a pitiful captive lovely in her subjection. Actually, the perfect appearance of the teeth support a suspicion that the owner was a very young person, indeed, more adolescent than woman. In this case, the story continued to its tragic end when the woman or girl was brought back to Moscow. Although Asch sheds little light on her life in Russia, he does tell us that she died from venereal disease. An anatomy professor in Moscow had performed an autopsy before forwarding the skull to Asch in St. Petersburg. Ironically, perhaps, the woman whose skull gave white people a name had been a sex slave in Moscow, like thousands of her compatriots in Russia and the Ottoman empire.

Blumenbach labeled his prize skull “beautiful” and “female Georgian,” going on to call the human variety it inspired “Caucasian,” a mysterious slippage he did not explain. Why not call it “Georgian,” we may ask, since the skull came from Georgia? The answer may lie in North America, where the newly formed United States already included a state called Georgia and, presumably, people called Georgians.* At any rate, during Blumenbach’s time, the notion of “Caucasian” achieved wide circulation.

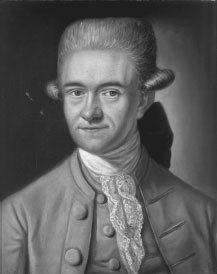

BLUMENBACH’S IDEA of Caucasian was as much mythical as geographical. On the one hand, he means the 170,000 square miles of land separating the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, comprising the embattled Muslim Chechnya as well as Christian Georgia and being home to some fifty ethnic groups. Today anthropologists parse these ethnicities into three main categories: Caucasian, Indo-European, and Altaic. Among the Altaic peoples are the Kalmyk/Kalmuck, whom Western tradition deemed ugly. Right beside them live the Circassians and Georgians, those beautiful white slave people of legend, both in the category of Caucasian peoples. Note that in 1899 William Z. Ripley pictured Caucasians in his authoritative Races of Europe. (See figure 6.6, Ripley’s “Caucasus Mountains.”)

Fig. 6.6. “Caucasus Mountains,” in William Z. Ripley, The Races of Europe (1899).

WHITENESS NOW takes its place in racial classification, reorienting the science of human taxonomy from Linnaeus’s geographical regions to Blumenbach’s emphasis on skin color as beauty. Once Blumenbach had established Caucasian as a human variety, the term floated far from its geographical origin. Actual Caucasians—the people living in the Caucasus region, cheek by jowl with Turks and Semites of the eastern Mediterranean—lost their symbolic standing as ur-Europeans. Real Caucasians never reached the apex of the white racial hierarchy; indeed, many Russians call them chernyi (“black”) on account of their supposed wild troublesomeness.18 Somehow specificity faded while the idea of a supremely beautiful “Caucasian” variety lived on, eventually becoming the scientific term of choice for white people. When scholars nowadays use “Caucasian” as racial terminology, they are harking back to the illustrious Blumenbach. But the term has a more complex genealogy, too, one connecting it to the larger history of race, beauty, and reactionary politics.

That part of the story brings in Blumenbach’s cranky Göttingen colleague Christoph Meiners (1747–1810). (See figure 6.7, Christoph Meiners.) For lack of documentation, we cannot know the exact degree of the personal interaction between Blumenbach and Meiners.19 Clearly, however, Meiners, with his preoccupation with human beauty and his counterrevolutionary politics, shadows the background of German racial theory.

Both Blumenbach and Meiners studied and then taught at the University of Göttingen, where Meiners assumed a professorship in 1776, about the same time as Blumenbach.* The eminence of the egalitarian-minded Blumenbach lives on, and when Blumenbach died at eighty-eight, in 1840, his membership in seventy-eight learned societies attested to his eminence in the masculine realm of letters.20† Led by the illustrious Humboldts, Blumenbach’s students had supervised the celebration of his jubilee—the fiftieth anniversary of his doctorate—in 1825. The politically retrograde Meiners has largely been forgotten.

During the 1790s Blumenbach, already the more distinguished colleague, seems to have taken note of Meiners’s voluminous, if obscure, publications.21 To be sure, Meiners’s name appears only once in the 1795 edition of Varieties of Humankind, but Blumenbach’s emphases—notably beauty (and the evocation of an ancient Greek ideal), the repeated mention of Tacitus and the “ancient Germans’” racial purity, and even the name “Caucasian”—betray the pull of his contrary colleague.

Both Meiners and Blumenbach focused on the same towering subject—humankind’s divisions—but otherwise their views diverged over methodology, politics, and conclusions, converging only on the naming of varieties and, increasingly, the importance of personal appearance. Blumenbach, as we know, accorded pride of place to skull measurement, whereas Meiners relied on travel literature, with its inevitable ethnocentrism. Another difference: Meiners wrote hastily and at great length, distorting the meaning of scholars he cited and filling his pages with wildly contradictory claims. Blumenbach and more rigorous colleagues, though themselves no paragons of consistency, objected to such sloppiness, criticizing Meiners’s reactionary intellectual one-sidedness. Meiners made no bones about it—inferior peoples’ inferiority justified, even required, their enslavement and the use of despotism for their control.22 Beauty and ugliness, he said, led naturally to different fates. Blumenbach did not agree.

Fig. 6.7. Christoph Meiners.

Meiners initially posited a counterintuitive binary racial scheme whose strange two-way racial classification appears in Grundriß der Geschichte der Menschheit (Foundations of the History of Mankind), published in 1785:

- Tartar-Caucasian, divided into Celtic and Slavic, and

- Mongolian.

The Tartar-Caucasian was first and foremost the beautiful race. The Mongolian was the ugly race, “weak in body and spirit, bad, and lacking in virtue,” as characterized by the Kalmucks. Meiners classifies Jews as Mongolian (i.e., Asian) along with Armenians, Arabs, and Persians, all of whom Blumenbach defined as Caucasian. Meiners makes his ugly Mongolian race dark-skinned. And he joined most of his German contemporaries in locating the ideal of human beauty in ancient Greece, but, he adds immodestly, the Germans rival the Greeks in beauty and bodily strength.23

Göttingen’s scholarly community muttered a good deal about Meiners’s lack of rigor and cranky conclusions, but mostly the criticism remained buried in private and rather academic letters. In any case, Meiners’s fringy popularity was widespread, and his work circulated extensively. Grundriß der Geschichte der Menschheit went through three editions and was translated into several languages.* His circle included French counterrevolutionaries who later fed the intellectual history of twentieth-century National Socialism.

Blumenbach may well have borrowed the name “Caucasian” from Meiners. But even if that borrowing took place, Blumenbach reached for higher authority in publication. He cited the illustrious Jean Chardin, not his neighbor’s cantankerous book. Though Meiners lacked the status of a member of the Royal Society, he did convince a certain circle of his own acolytes.

In the early 1790s, Meiners began to move racial discourse in Göttingen beyond comparisons between Europeans and non-Europeans and to concentrate on an intra-European hierarchy of lightness and beauty, with ancient Germans on top.24 In a series of articles vaunting the superiority of Germans among Europeans, Meiners describes non-German Europeans’ color as “dirty white” and compares it unfavorably with the “whitest, most blooming and most delicate skin” of the Germans. The early Germans he describes as “taller, slimmer, stronger, and with more beautiful bodies than all the remaining peoples of the earth.” Meiners maintains, following Tacitus, that Germans possess the prized quality of racial purity. By the late eighteenth century, Meiners was making claims for stereotypical Nordic/Teutonic attributes that some in the academic world would echo for another hundred years.25 That was radical enough, but he did not stop there.

As his thought continued to evolve, Meiners teased out distinctions not only between different kinds of Europeans but also between different kinds of Germans: Germans of the north and Germans of the south. Northerners, such as the Protestants of Dresden, Weimar, Berlin, Hanover, and Göttingen were in; southerners—the Catholics of Vienna—were out.

This may seem a strained dichotomy, but, in fact, it was not new. At this time the idea of southern Germany meant Vienna, the sophisticated, nineteen-hundred-year-old capital of the Holy Roman Empire. That empire, self-proclaimed heir of the Roman empire of antiquity, sprawled across Europe from the Low Countries to the Czech, Slovak, and Hungarian lands bordering the Ottoman empire. It might have been on its next-to-last legs, but Vienna, created as a barrier against the Germani tribes, still occupied at least a rhetorical space between peoples within and those outside civilization. Thus differences between southern and northern Germans in the late eighteenth century could be thought to resemble Caesar’s and Tacitus’s civilized Gauls within the Roman empire and wild Germans—those northerners outside. Envy also played its part. A wealthy imperial capital, Vienna had long boasted a high culture beyond the means of Germans of the north.

Such envy coupled easily with contempt. It was only a small step for north Germans to feminize the Viennese, to turn them into soft Gauls and trumpet the enduring masculinity of untamed northerners. This anticivilization strategy gendered north and south, Gaul and German, a Gaul/French, German/German metaphor that held a promising future as an anthropological strategy. It also contained a political dimension. Like most advocates of racial hierarchy, Meiners resented the French for their revolution, which had led to unfortunate leveling tendencies in the German lands and, critically, to Jewish emancipation.

It is not surprising, therefore, that Meiners later became the Nazis’ favorite intellectual ancestor, for he knew his Tacitus and built castles upon it. In phrases characteristic of nineteenth-century Teutomania, Meiners describes Germans’ possession of the “whitest, most blooming and most delicate skin,” the “tallest and most beautiful” men not only in Europe, but in the entire world, and a “purity of blood” that made them the physical, moral, and intellectual superiors of everyone. The ancient Germans were “strong like oak-trees,” but their descendants, though still better than everyone else, had degenerated through indulgence in civilization’s luxuries. Rigorous practice of the martial arts would restore Germans to their former virility and beauty.26

Some in Europe lapped up this super-racist theory, as Meiners attracted a coterie of French counterrevolutionaries in the late 1790s, including Jean-Joseph Virey, whose Histoire naturelle du genre humain (1800) divided humanity into “beautiful whites” and “ugly browns or blacks,” and Charles de Villers.27 A correspondent with Madame Germaine de Staël and an expert on Kant, Villers settled in Göttingen and studied with Meiners. With his influence on de Staël, German racial theory moved west. It consisted of a bundle of notions predicated on contrasts between European and African, but also between European and Asian, northerner and southerner, lighter and darker, and Germans and French.