8

EARLY AMERICAN WHITE PEOPLE OBSERVED

North America’s unique jumble of peoples appealed to Western intellectuals as a test case for humanity. Who are the Americans? What are they like? Might the United States, so far across the western sea, reveal mankind’s future? Or at least Europeans’ future? Some observers saw Americans as white and egalitarian; others perceived a multiracial assortment of oppressors and oppressed. Meanwhile, the government of this new republic went about its own mundane business, answering its own questions by counting its people according to its own devices.

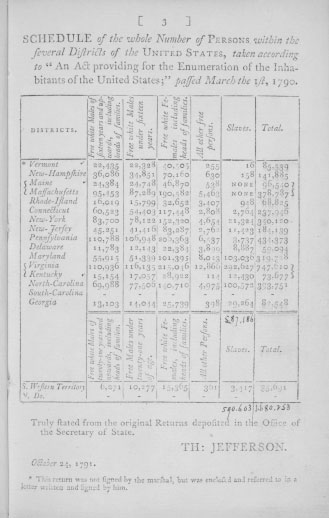

In article 1, sections 2 and 9, of the Constitution, the United States created a novel way of apportioning representation and direct taxation: a national census every ten years. The first U.S. census, taken in 1790, recognized six categories within the population: (1) the head of each household, (2) free white males over sixteen, (3) free white males under sixteen, (4) free white females, (5) all other free persons by sex and color, and (6) slaves.1 U.S. marshals conducted this first census, recording results on whatever scraps of paper lay at hand. The effort required eighteen months and counted 3.9 million people, incidentally a number George Washington called too low. The first undercount.

Three terms parsed the only race mentioned—white—and two categories demarcated slave and free legal statuses. (See figure 8.1, U.S. census, 1790.) Unfree white persons, of whom there were many in the new union, seem to have fallen through the cracks in 1790, though the fourfold mention of the qualifier “free” by inference recognizes the nonfree white status of those in servitude. Had all whites been free and whiteness meant freedom, as is often assumed today, no need would have existed to add “free” to “white.” The 1800 census fixed this problem through an enumeration of “all other persons, except Indians not taxed.”* For these early censuses, “free” formed a meaningful classification not identical with “white.”

Fig. 8.1. “Schedule of the whole Number of Persons within the several Districts of the United States…” (1790).

Census categories kept changing every ten years, as governmental needs changed and taxonomical categories shifted, including taxonomies of race. Throughout American census history, non-Europeans and part-Europeans have been counted as part of the American population, usually lumped as “nonwhite,” but occasionally disaggregated into black and mulatto, as in the censuses of 1850 and 1860.

Counting free white males by age sprang from a need to identify men eligible for militia service, the only armed service of the time. To calculate each state’s congressional representation, Congress counted all the free persons (women, too, although they did not have the vote) and three-fifths of “others,” that is, indentured laborers and slaves. Later on, realities behind the census’s careful separation of bondage and race changed, calling for new categories. As politics freed all white people and ideology whitened the face of freedom, “free white males” seemed a useless redundancy.†

DURING THE early nineteenth century, when “free white males” was losing its usefulness because fewer and fewer whites were not free, another phrase was coming into use, one with a much longer life: “universal suffrage.” The United States was the first nation to drastically lower economic barriers to voting. Between 1790 and the mid-1850s the ideology of democracy gained wide acceptance, so that active citizenship was opened to virtually all adult white men, including most immigrant settlers. Mere adult white maleness thus replaced eighteenth-century requirements of a stake in society (property ownership, tax paying) and political independence (one’s own steady income) before a man could vote. With the vote came inclusion in public life, so that the antebellum period associated with the rise of the Jacksonian common man witnessed the first major extension of the meaning of what it meant to be American.2

All women, people ineligible to become citizens (Native American Indians and Asians), the enslaved, and free people of African descent outside New England continued to be excluded, as well as paupers, felons, and transients such as canal workers and sailors. (Even today, children, noncitizens, and most convicted felons cannot vote. People who cannot meet residency requirements and do not register prior to voting are also disenfranchised.) In this situation, “universal suffrage” meant adult white male suffrage, though from time to time the definition of “white” came into question. Were men with one black and one white parent or three white and one black grandparent “white”? Did “white” mean only Anglo-Saxons, or all men considered Caucasian, including those classed as Celts?*

The abolition of economic barriers to voting by white men made the United States, in the then common parlance, “a white man’s country,” a polity defined by race and limited to white men. Once prerequisites for active citizenship came down to maleness and whiteness, poor men could be welcomed into the definition of American, as long as they could be defined as white—the first enlargement of American whiteness.

WE CAN date the pairing of “American” with descendants of Europeans to the quickly translated, widely read, and endlessly quoted Letters from an American Farmer of 1782, by the French soldier-diplomat-author Michel-Guillaume-Jean de Crèvecoeur (1735–1813). Crèvecoeur inaugurated a hardy tradition, that of contrasting class-riven Europe, the land of opulent aristocrats and destitute peasants, with the egalitarian United States, home of mobility and democracy.

Crèvecoeur’s road to fame meandered far and wide. After immigrating to Canada and fighting on the French side during the Seven Years’/French and Indian War of 1754–63, he moved to New York and changed his name to J. Hector St. John. The gratifying picture of Americans in Letters from an American Farmer and Crèvecoeur’s subsequent success as a French diplomat in the United States raised him high, earning election to the exclusive American Philosophical Society, plus many a local honor. The Vermont legislature so revered Crèvecoeur that it named a town St. Johnsbury after him; it became the largest city in Vermont’s impoverished and deeply conservative northeast region.

Crèvecoeur’s letter 3 asks, “What then is the American, this new man?”—and answers,

He is either an European or the descendant of an European, hence that strange mixture of blood, which you will find in no other country. I could point out to you a family whose grandfather was an Englishman, whose wife was Dutch, whose son married a French woman, and whose present four sons have now four wives of different nations. He is an American who, leaving behind him all his ancient prejudices and manners, receives new ones from the new mode of life he has embraced, the new government he obeys, and the new rank he holds…. Here individuals of all nations are melted into a new race whose labors and posterity will one day cause great changes in the world…. From involuntary idleness, service dependence, penury, and useless labor [in Europe], he has passed to toils of a very different nature, rewarded by ample subsistence.—This is an American.3

In addition to a willingness to innovate and to think new thoughts, heterogeneous—but purely European—ancestry characterizes the American.

This “new man” escapes old Europe’s oppression, embraces new opportunity, and glories in freedom of thought and economic mobility. Now a classic description of the American, Crèvecoeur’s paragraph constantly reappears as an objective eyewitness account of American identity. But letter 3 is only one part of the story. When other classes, races, sexes, and the South entered Crèvecoeur’s picture, all sorts of revisions became necessary. For instance, poor and untamed white people, particularly southerners, continued to occupy a separate category well below the American. While the American and the poor white might both be judged white according to American law, poor white poverty and apparent wildness kept him at a remove from the charmed circle. Such complexity ensured that the who question could not be answered clearly. But European and American observers never stopped pursuing it.

Crèvecoeur conceded the existence of other Americans—other white Americans—who do “not afford a very pleasing spectacle.” He offers a hope that the march of American progress would soon displace or civilize these drunken idlers; meanwhile, white families living beyond the reach of law and order “exhibit the most hideous parts of our society.” Crèvecoeur cannot decide whether untamed frontier families represent a temporary stage or a degeneration beyond redemption: “once hunters, farewell to the plow.” Indians appear positively respectable beside mongrelized, half-savage, slothful, and drunken white hunting families.

Concerning slavery, ugly scenes in Charleston, South Carolina, break Crèvecoeur’s heart, but his pessimism arises most from the shock of his hosts’ callousness. The rich slaveholders entertaining Crèvecoeur are the “gayest” people in America—but gay at the cost of their humanity: “They neither see, hear, nor feel the woes” of their slaves or the blood-curdling violence of their social arrangements. Crèvecoeur can only marvel at such insouciance. In their situation, he says,

never could I rest in peace; my sleep would be perpetually disturbed by a retrospect of the frauds committed in Africa in order to entrap them, frauds surpassing in enormity everything which a common mind can possibly conceive…. Can it be possible that the force of custom should ever make me deaf to all these reflections, and as insensible to the injustice of that [slave] trade, and to [slaves’] miseries, as the rich inhabitants of this town seem to be?4

Face-to-face with the realities of southern slavery, Crèvecoeur becomes the first to predict slave insurrection as an inevitable consequence of “inveterate resentment” and a “wish of perpetual revenge.” This is a European thinking in terms of rampant poverty and obscene wealth and seeing the enslaved as the poor, not simply as a race of people. Thus Crèvecoeur’s America is split as much by class as by race, a society in contrast with the sunny, democratic image of his more popular pronouncement.

WRITING A few years after Crèvecoeur, Thomas Jefferson (1743–1826) missed the class dimension that so alarmed Crèvecoeur. Born and raised in Virginia, Jefferson never questioned that American society was structured according to race, not class; to him, the poor people who served, including most prominently his slaves, belonged to a naturally servile race. By taking note of black people, he did not concede them status as Americans, who are “our people.”

Like many other intellectuals, Jefferson held that slavery harms whites more than blacks. “Query XVIII: Manners,” in Notes on the State of Virginia (1787), reflects upon the “unhappy” influence of slavery on the slave-owning class, scarcely mentioning the suffering of the enslaved. Rather it dwells on the price paid by the South’s white slave owners. Slave-owning children mimic their parents’ abuse of the people they own, coarsening their character and, thereby, their society. The white child, “thus nursed and educated, and daily exercised in tyranny,” Jefferson warns, “cannot but be stamped by it with odious peculiarities. The man must be a prodigy who can retain his manner and morals undepraved by such circumstances.”5

In apportioning the injuries of slavery, Jefferson and Crèvecoeur mostly agreed. But their theories of American ancestry conflict, for the eloquent Jefferson rejected any idea of a mongrel American, even though he fathered seven of them with Sally Hemings, a woman he owned. He also rejected Crèvecoeur’s “Dutch” man—probably meaning a deutsch man, or German—as essential to the American family tree. Jefferson’s family tree was of sturdy oak, the Saxons of England.

Throughout his life Thomas Jefferson believed in the Saxon myth, a story of American descent from Saxons by way of England. He had conceived a fascination with it as a student at William and Mary College in 1762 and never wavered in it. Over fifty years of book collecting—his personal library formed the basis of the Library of Congress—Jefferson came to own the country’s largest collection of Anglo-Saxon and Old English documents.6

As a founding father, Jefferson theorized Americans’ right to independence on the basis of Saxon ancestry. Laying out that claim in July of 1774, he makes English people “our ancestors,” and the creators of the Magna Carta “our Saxon ancestors.” Though the Magna Carta dates from 1215 and the Norman conquest from 1066, Jefferson maintains that the system of rights of “our ancestors” was already in place when “Norman lawyers” connived to saddle the Saxons with unfair burdens.7 He continued to associate Saxons with the liberal Whigs and Normans with the conservative Tories, as though liberal and reactionary parties had existed from time immemorial, almost as a matter of blood.8 For Jefferson, English-style Saxon liberty was not a trait to be found in Germans.

Jefferson’s Saxon genealogy ignored a number of inconvenient facts. The oppressive English king George III was actually a Saxon and also the duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg as well as elector of Hanover in Lower Saxony. Furthermore, George III’s father and grandfather, Hanoverian kings of England before him, had been born in Germany and spoke German as a first language. It hardly mattered. To Jefferson, whatever genius for liberty Dark Age Saxons had bequeathed the English somehow thrived on English soil but died in Germany.*

In the Philadelphia Continental Congress of 1776, Jefferson went so far as to propose embedding his heroic Saxon ancestors in the great seal of the United States. Images of “Hengist and Horsa, the Saxon chiefs from whom we claim the honor of being descended,” would aptly commemorate the new nation’s political principles, government, and physical descent.9* This proposition did not win approval, but Jefferson soldiered on. In 1798 he wrote Essay on the Anglo-Saxon Language, which equates language with biological descent, a confusion then common among philologists. In this essay Jefferson runs together Old English and Middle English, creating a long era of Anglo-Saxon greatness stretching from the sixth century to the thirteenth.

With its emphasis on blood purity, this smacks of race talk. Not only had Jefferson’s Saxons remained racially pure during the Roman occupation (there was “little familiar mixture with the native Britons”), but, amazingly, their language had stayed pristine two centuries after the Norman conquest: Anglo Saxon “was the language of all England, properly so called, from the Saxon possession of that country in the sixth century to the time of Henry III in the thirteenth, and was spoken pure and unmixed with any other.”10 Therefore Anglo-Saxon/Old English deserved study as the basis of American thought.

One of Jefferson’s last great achievements, his founding of the University of Virginia in 1818, institutionalized his interest in Anglo-Saxon as the language of American culture, law, and politics. On opening in 1825, it was the only college in the United States to offer instruction in Anglo-Saxon, and Anglo-Saxon was the only course it offered on the English language. Beowulf, naturally, became a staple of instruction. Ironically, the teacher hailed from Leipzig, in eastern German Saxony. An intensely unpopular disciplinarian, Georg Blaettermann also taught French, German, Spanish, Italian, Danish, Swedish, Dutch, and Portuguese. After surviving years of student riots and protests, Blaettermann was fired in 1840 for horsewhipping his wife in public.11

JEFFERSON’S ENTHUSIASM for teaching Anglo-Saxon stayed confined to southern colleges until the 1840s, and his Essay on the Anglo-Saxon Language, a rambling 5,400 words composed mostly in 1798, did not appear in print until 1851.* Clearly, slavery and the characteristics of black people were stirring more passion than any American claim to Anglo-Saxon ancestry. By contrast, Jefferson’s Notes on the State of Virginia (1784) immediately enjoyed a wide and impassioned readership. This eloquent, though very self-centered, summary of American (not just Virginian) identity, impugns the physical appearance of African Americans and makes them out to be natural slaves. Not that this insult toward an oppressed people inspired only approval. One of a multitude of critics resided at the most Virginian of northern colleges: the College of New Jersey.

HANDSOME, ELEGANT Samuel Stanhope Smith (1751–1819) became president of the College of New Jersey (later Princeton College) at forty-three, its first alumnus president. (See figure 8.2, Samuel Stanhope Smith.) Both of Smith’s parents had strong Princeton connections: his mother’s father had been a founding trustee, and Smith’s father, a Presbyterian minister and schoolmaster, also served as a trustee. Smith graduated from Princeton with honors in 1769. As a tutor and postgraduate student with John Witherspoon, an eminent scholar from Scotland, Smith imbibed the “Common Sense” ideals of Scottish realism.

Following an established Princeton trajectory, Smith went south to Virginia as a missionary and became rector and then president of the academy in Prince Edward County that became Hampden-Sydney College. His future secure, he married John Witherspoon’s daughter and bought a plantation, evidently intending to remain among his appreciative Virginia hosts. However, a Princeton professorship in moral philosophy lured Smith back to New Jersey.

Ensconced once again in Princeton, Smith collected the young nation’s honors: Yale made him doctor of divinity in 1783, and in 1785 the American Philosophical Society took him into its membership. After Thomas Jefferson proposed a measure advocating widespread primary education in Virginia in 1788, he and Smith exchanged letters in its support. The measure did not pass, and the politics of the two men subsequently diverged. By 1801 Smith had turned politically conservative enough to deplore Jefferson’s presidential candidacy as likely to cause “turbulance [sic] & anarchy.”12

By then Smith had succeeded his mentor Witherspoon as president of Princeton, and had turned into an intellectual maverick, downgrading the college’s classics and Presbyterianism in favor of science, thereby antagonizing its trustees.13 As Smith grew older and Princeton students more rowdy, he expelled three-quarters of the student body for rioting in 1807. When the Presbyterian Church established a theological seminary right inside the college’s Nassau Hall, Smith grasped just where his lack of orthodoxy was leading. In 1812 he was forced to resign the presidency, and he died seven years later.14 All that lay ahead in 1787, when he addressed the American Philosophical Society on differences in skin color, and his star was still ascendant.

SMITH’S ADDRESS looked back to the polygenetic essay of a Scottish philosopher named Henry Home, Lord Kames, entitled Discourse on the Original Diversity of Mankind (1776). One of Kames’s main points was a rejection of biblical doctrine that traces the unity of humanity through descent back to a single originating couple. Smith disagreed with Kames. Every people did belong to the same species, and differences sprang from circumstance: “I believe that the greater part of the varieties in the appearance of the human species,” Smith declares, “may justly be denominated habits of the body.” Where people live, not their ultimate ancestors, explains variations in human skin color: “In tracing the origin of the fair German, the dark coloured Frenchman, and the swarthy Spaniard, and Sicilian, it has been proved that they are all derived from the same primitive stock.”15 All mankind descended from Adam and Eve, subsequently diverging though adaptation.

Fig. 8.2. Samuel Stanhope Smith as president of Princeton College.

Smith’s defense of biblical truth met so warm a reception that the lecture appeared immediately in print. Mary Wollstonecraft, the feminist pioneer, favorably reviewed Smith’s Essay in the London Analytical Review, welcoming his insistence on the unity of mankind. Smith’s distinguished physician-historian brother-in-law, David Ramsay, a Pennsylvanian living in South Carolina, pitched in. Ramsay seconded Smith’s views on skin color, lauded his criticism of Thomas Jefferson’s antiblack slurs, and agreed with Smith about the dominance of climate in shaping human culture. Writing directly to Jefferson, Ramsay noted that “the state of society” also plays a crucial part. In complete agreement with Crèvecoeur and Smith, Ramsay added, “Our back country people are as much savage as the Cherokees.”16* Jefferson seems not to have replied to Ramsay. But encouraged by support, Smith continued tinkering with his Essay.

One influence was Blumenbach’s 1795 edition of De generis humani varietate nativa, which Smith read in its original Latin and incorporated into an enlarged 1810 edition of his lecture, An Essay on the Causes of the Variety of Complexion and Figure in the Human Species.17 Here Smith assumes that civilization, not barbarism, was humanity’s original condition; uncivilized people would have regressed on account of their harsh living conditions. Different climates, for instance, create differences in human skin color—not a new explanation. Beauty is not all that important, in any case, Smith goes on to say, citing the physical attractiveness of even some black people: “In Princeton, and its vicinity I daily see persons of the African race whose limbs are as handsomely formed as those of the inferior and laboring classes, either of Europeans, or Anglo-Americans.”

A bit—but only a bit—of a cultural relativist, Smith recognizes more emphatically than Blumenbach or Camper the cultural specificity of beauty ideals: “Each nation differs from others as much in its ideas of beauty as in personal appearance. A Laplander prefers the flat, round faces of his dark skinned country women to the fairest beauties of England.”18 Meanwhile, as we have seen, anthropologists of the time were debating whether Lapps in the north of Sweden and Finland might count as Europeans at all. Linnaeus, the great taxonomist, for instance, said no; Blumenbach, Germany’s leading racial classifier, wavering, said yes. Eventually the question faded into insignificance as anthropology’s terms of analysis moved away from questionable attempts to rank order of physical beauty.

We should note that Smith was no multiculturalist. His Americans, like Crèvecoeur’s, descend only from Europeans. While acknowledging the presence of Native Americans and Africans on American soil and occasionally comparing the height of Osage Indians to that of the ancient Germans, Smith had no intention of widening the category of American.

Thomas Jefferson and Samuel Stanhope Smith had both prospered in a Virginia of many mixed-race people, some right in Jefferson’s own family. We do not know the makeup of Smith’s household in Virginia, but we do know that the two men figured the notion of purity differently. Jefferson somehow kept the rainbow people of Monticello beyond the reach of his race theory, allowing him to conceive of a platonic “pure and unmixed” Saxon ideal. For Smith there could be no such European thing, “in consequence of the eternal migrations and conquests which have mingled and confounded its inhabitants with the natives of other regions” in a continuing process of perpetual change.19 Smith and Jefferson found words for purity and mixture in Europe, even among Europeans in the New World. But the African-Indian-European mixing occurring right under their noses in eighteenth-century Virginia overwhelmed their rhetorical abilities. The leaders of American society could not face that fact squarely. For them mixing produced a unique new man, this American, but mixing only among Europeans.

So if climate is paramount, what of the American climate, with its extremes of heat and cold and its stagnant waters? Not much good comes of it, Smith feels, for it imparts to Americans “a certain paleness of countenance, and softness of feature…in general, the American complexion does not exhibit so clear a red and white as the British, or the German. And there is a tinge of sallowness [paleness, sickliness, yellowness] spread over it.” Elevation and proximity to the sea also affect skin color. Hence the white people of New Jersey have darker skins than white people in hilly Pennsylvania. White skin darkens farther south. White southerners, especially the poor, living in a hot climate and at lower elevations, are visibly darker than northerners. Americans living in different climates look different, but, all in all, Americans look pretty much the same.20

To justify his tortured climatic theories, Smith has to practice a sort of wild conflation of climate to skin color to savagery. Even when all their ancestors were European, Smith finds that lower-class southerners look very much like Indians and live in a “state of absolute savagism.” This idea, that living among Indians made white Americans resemble them in skin color, enjoyed wide currency in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Crèvecoeur exclaimed that “thousands of Europeans are Indians,” and others in colonial America testified to the tendency in Europeans living with Indians to come to resemble them in color as well as in dress. Moreover, such a life rendered their bodies so “thin and meagre” that their bones showed through their skin. Had poor southerners been discovered in some distant land, Smith surmises, polygenesists would display them as proof of multiple human origins.21 Echoing Crèvecoeur, Smith calls uncivilized poor southerners—“without any mixture of Indian blood”—a potential drag on American society.

So much for the bottom of the American barrel. But Smith also demeans elite southern whites like Thomas Jefferson and his self-satisfied, privileged class. In Notes on the State of Virginia Jefferson had scorned the poetry of the Boston slave Phillis Wheatley as proof that the Negro could never demonstrate genius. Smith’s retort vindicates black people and insults southern whites: Jefferson was just plain wrong to deride the abilities of a race living so wretchedly, first in Africa, then in American slavery. “Genius,” Smith says, “requires freedom” and the educational and psychological conditions permitting creative thought. Not stopping there, Smith goes after the intellectual abilities of Jefferson’s own class, asking, “Mr. Jefferson, or any other man who is acquainted with American planters, how many of those masters could have written poems equal to those of Phillis Whately [sic]?”22 In all of this we can see that for a hundred more years, identity of the American would contain a contradiction: Americans look and act pretty much the same, but southerners are different—and inferior.

AS LONG as observers thought only of European peoples as Americans, the country’s rosy egalitarian image glowed nicely. Always present, however, though little known, was a counterargument that calculated Americanness by experience rather than skin color. Though black authors often generalized about the character of white people, most of their commentary came in the form of asides embedded in work focused on people of African descent. David Walker and Hosea Easton represented their views, addressing their fellow Americans as critics of white supremacy.23

In 1829 David Walker (1785–1830), a thoughtful and politically engaged African American living in Boston, published an eighty-page tract with a jaw-breaking title: David Walker’s Appeal: in four articles, together with a preamble, to the coloured citizens of the world, but in particular, and very expressly, to those of the United States of America.* Born free in Wilmington, North Carolina, Walker had moved to Boston around 1825 and made his living as a dealer in used clothing. Among his many activities, he wrote for and distributed the nation’s first black newspaper, Freedom’s Journal, and frequently delivered public addresses at black Bostonians’ celebrations—of Haitian independence, for instance, or a visit to Boston by an African prince recently emancipated from southern slavery. A Mason and Methodist (but a critic of black religiosity), Walker was well known and well respected as an activist among Boston’s black people, who numbered about one thousand, and within the antislavery community that surrounded William Lloyd Garrison. Garrison reviewed Walker’s Appeal positively in an early number of the Liberator, soon to become the nation’s most influential abolitionist periodical.

Walker’s Appeal spread a wide net, excoriating “whites” and, indeed, “Christian America” for its inhumanity and hypocrisy. Over the long sweep of immutable racial history, Walker traces two essences. On one side lies black history, beginning with ancient Egyptians (“Africans or coloured people, such as we are”) and encompassing “our brethren the Haytians.” On the other lie white people, cradled in bloody, deceitful ancient Greece. Racial traits within these opposites never change:

The whites have always been an unjust, jealous, unmerciful, avaricious and blood-thirsty set of beings, always seeking after power and authority.—We view them all over the confederacy of Greece, where they were first known to be anything, (in consequence of education) we see them there, cutting each other’s throats—trying to subject each other to wretchedness and misery—to effect which, they used all kinds of deceitful, unfair, and unmerciful means. We view them next in Rome, where the spirit of tyranny and deceit raged still higher. We view them in Gaul, Spain, and Britain.—In fine, we view them all over Europe, together with what were scattered about in Asia and Africa, as heathens, and we see them acting more like devils than accountable men.*

Murder, Walker concludes, remains the central feature of whiteness, though a sliver of hope for their future might reside in the American heritage of freedom—he ends by quoting the Declaration of Independence, which he exempts from white Americans’ wickedness. The English, for instance, had surmounted their history, turned their backs on slaving, and offered black people the hand of friendship. Once the English stopped oppressing the Irish, Walker opines, their regeneration would be complete.24 At bottom, David Walker’s Appeal speaks to “white Christians,” blaming, ridiculing, and threatening them with destruction in retribution for their mistreatment of blacks. Given white people’s moral and behavioral weaknesses, he wonders, coyly, just which is the inferior race: “I, therefore, in the name and fear of the Lord and God of Heaven and of earth, divested of prejudice either on the side of my colour or that of the whites, advance my suspicion of them whether they are as good by nature as we are or not.”25 This is not to say that Walker was ready to boast about the slaves: as for black people, “we, (coloured people of these United States of America) are the most wretched, degraded and abject set of beings that ever lived since the world began.” He aimed pointed criticism at free northern blacks: “some of them can write a good hand, but who, notwithstanding their neat writing, may be almost as ignorant, in comparison, as a horse.” Walker discerns “a mean, servile spirit” among the people he calls “my colour.” Only when black people organize and throw off the oppressor’s yoke will they “arise from this death-like apathy” and “be men!”26

Walker’s Appeal testifies to its author’s immersion in the classics of American and European culture as well as to his familiarity with current politics affecting the Irish, Jews, and Greeks. He strongly indicts white American hypocrisy as exhibited by the Declaration of Independence and the work of Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson had died in 1826, but Walker, like Samuel Stanhope Smith, felt that the insults from an American of Jefferson’s stature demanded a response. How could Jefferson, a man of enormous learning and “excellent natural parts,” stoop to judge “a set of men in chains.” Jefferson may have believed that black people wanted to be white, but in this he is “dreadfully deceived—we wish to be just as it pleased our Creator to have made us.”27

An effective promoter, Walker spread his Appeal widely, even, via black and white sailors, into the slaveholding South, where it made its author well known and much hated. The incendiary pamphlet, addressed directly to African Americans, so alarmed Virginia’s upper classes that discussion of it took place in a closed-door session of the General Assembly. In New Bern and Wilmington, North Carolina, any black readers associated with Walker’s Appeal paid with their lives.28

In 1830, at only forty-five years of age, Walker died of tuberculosis. That scourge of the nineteenth-century urban poor had, only days before, taken his daughter. A few months earlier, he had issued what became, by default, the final edition of Walker’s Appeal. Now, Boston’s Maria Stewart, the first American woman to publicly address “promiscuous” audiences (i.e., audiences including women as well as men), eulogized Walker as “most noble, fearless, and undaunted.” In the revolutionary year of 1848, the Reverend Henry Highland Garnet lauded Walker as a tireless fighter for freedom. Walker’s activism, Garnet concludes, “made his memory sacred.” Walker’s memory remained vivid among abolitionists well into the mid-nineteenth century, only to fade after the Civil War. But meanwhile, he had struck a strong blow against the notion that whiteness, throughout history, deserved to be judged positively.29

THE REVEREND Hosea Easton (1799–1837) of Hartford, Connecticut, had been born into an activist family with a quintessentially American mixed background, but of a sort Crèvecoeur had not been able to see. Easton’s mother was of at least partial African ancestry, and his father, James, a veteran of the Revolutionary War, had descended from Wampanoag and Narragansett Indians. After the war James Easton had prospered as an iron manufacturer in North Bridgewater (now Brockton, Massachusetts). With his complicated lineage, Hosea identified himself as “colored,” effectively suppressing the Indian ancestry, probably in the interest of achieving undisputed citizenship.*

Color lines were hardening in the first quarter of the nineteenth century in Massachusetts, with the result that the Easton family found itself rejected from the public sphere. After a long, spirited, dispiriting, and losing protest against enforcement of racial segregation in their local school and church, James Easton opened a school for colored youth in the mid-1810s.

Becoming a minister and following in his father’s activist footsteps, Hosea Easton attended the first meeting of the National Convention of Free People of Color in Philadelphia in 1831, when he was thirty-two. Times were harsh for people of color, and a mob of angry white supremacists attacked Easton’s parishioners and burned down his church in Hartford in 1836. Not one to back off, Easton issued his response the following year in the form of A Treatise on the Intellectual Character and Civil and Political Condition of the Colored People of the U. States; and the Prejudice Exercised towards Them: with a Sermon on the Duty of the Church to Them.30

Citing ancient and current history, Easton’s Treatise echoes David Walker’s Appeal by comparing the history of Africa—starting with Ham and ancient Egypt—to Europe’s from its roots in ancient Greece. A stout Afrocentrist, Easton maintains that black and brown ancient Egyptians taught the Greeks everything of value. Conversely, he considers European history one long saga of bloodletting, a particular irony since nineteenth-century Europeans and white Americans loudly proclaimed themselves superior in civilization:

It is not a little remarkable, that in the nineteenth century a remnant of this same barbarous people should boast of their national superiority of intellect, and of wisdom and religion; who, in the seventeenth century, crossed the Atlantic and practised the same crime their barbarous ancestry had done in the fourth, fifth and sixth centuries: bringing with them the same boasted spirit of enterprise; and not unlike their fathers, staining their route with blood, as they have rolled along, as a cloud of locusts, toward the West. The late unholy war with the Indians, and the wicked crusade against the peace of Mexico, are striking illustrations of the nobleness of this race of people, and the powers of their mind.

Five and a half pages of grisly wrongs perpetrated by Europeans through the ages close, “Any one who has the least conception of true greatness, on comparing the two races by means of what history we have, must decide in favor of the descendants of Ham. The Egyptians alone have done more to cultivate such improvements as comports to the happiness of mankind, than all the descendants of Japhet put together.”

What white supremacists praise as the products of energy and enterprise, Easton describes as booty obtained

by the dint of war, and the destruction of the vanquished, since the founding of London, A. D. 49. Their whole career presents a motley mixture of barbarism and civilization, of fraud and philanthropy, of patriotism and avarice, of religion and bloodshed…. And instead of their advanced state in science being attributable to a superior development of intellectual faculties,…it is solely owing to…their innate thirst for blood and plunder.31

In a slight concession, Easton connects civilization to white people, but only as an outcome of violence rather than of innate intelligence. White people are not smarter; they are meaner.

Despite their pungency, neither Walker’s Appeal nor Easton’s Treatise on the Intellectual Character ever truly penetrated the public consciousness at home or in Europe during the nineteenth century. The visibility of Walker’s Appeal grew in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, but never approached the reputation of the champion of foreign analysts.

DEMOCRACY IN AMERICA must hold a record as the most quoted French text in the United States. The Princeton University Library holds thirty-one English editions of the originally two-volume work, published to great acclaim in 1835 and 1840. The reason for such popularity is not far to seek. Alexis de Tocqueville (1805–59) not only approved of the United States; he possessed a lineage Americans prized in their visiting friends. (See figure 8.3, Alexis de Tocqueville.)

Tocqueville’s conventionally Catholic, conventionally conservative aristocratic family lived in Normandy. As a young man, he rose in the legal service of King Charles X, prospering in Versailles until the king’s abdication in the wake of the 1830 July Revolution. Such upheaval at the top of French management threatened Tocqueville’s future. So much so, it seemed a good moment for Tocqueville and a dear friend, Gustave de Beaumont, another aristocratic lawyer of progressive turn of mind, to take a sabbatical from France in the United States, ostensibly to study prison reform. In fact, Beaumont and Tocqueville did publish a report on prisons, in 1833.32 But it was Tocqueville’s subsequent study on the United States, Démocratie en Amérique (Democracy in America, 1835), which made him famous.

Democracy in America is seldom cited as part of any tradition of racial thought, for Tocqueville ascribes American behavior to the whole of American society rather than to any racial trait. Society grows out of laws, governance, and economic opportunity. Finding an exceptional society in the United States, Tocqueville locates the source of this exceptionalism in American democracy. While American religion plays a role in American life, democracy trumps it, setting the tone in spheres both private and public. “Equality” provides the keyword.

On its first page, Democracy in America mentions “the equality of social conditions” three times, and many of the following 800-plus pages elaborate that basic point. The opening statements and the hundreds more pages label the United States a country populated by white people directly descended from the English. The phrase “the English race” appears repeatedly in headings and in the body of the text. In the conclusion to volume 1, Tocqueville glimpses “the whole future of the English race in the New World.” Chapter 3 of volume 2 bears the title “Why the Americans Show More Aptitude and Taste for General Ideas Than Their Forefathers, the English.”33*

Fig. 8.3. Alexis de Tocqueville.

The American of Democracy in America is primarily a northerner, usually a New Englander of British, Puritan descent. If he lacks brilliance and bores his guests, it is because he concentrates on making money. But the American’s heart is in the right place, right enough, at any rate, for him to be about building a country of certain future greatness. Tocqueville does not make slavery a crucial theme of analysis, for his the American is a citizen of Massachusetts, a quintessential free state. Therefore he nestles his discussion of slavery in the chapter on race—admittedly a topic he prefers to leave to his friend Beaumont—and thereby minimizes one of the core issues in American politics and culture.

Only after 370 pages (in the Penguin Classic edition) does Tocqueville concede any racial heterogeneity to the United States, and with heterogeneity comes much unpleasantness. The following 100 pages, entitled “A Few Remarks on the Present-day State and the Probable Future of the Three Races Which Live in the Territory of the United States,” contrast sharply with the rest of volume 1. On the Lower Mississippi River, Tocqueville and Beaumont encounter Indians on the Trail of Tears, “these forced migrations” whose “fearful evils…are impossible to imagine…. I have witnessed evils,” Tocqueville admits a couple of paragraphs later, “I would find it impossible to relate.”* Regarding the plight of Indians in the United States, words practically fail Tocqueville.

As for black people, they seem less fated for extinction than Native Americans, but their situation is nevertheless dire: black people, enslaved or free, “only constitute an unhappy remnant, a poor little wandering tribe, lost in the midst of an immense nation which owns all the land.” Such an assessment seems strange, if not ridiculous, to the twenty-first-century ear, since “this poor little wandering tribe” comprised more than two million people, more than 18 percent of the total population.

Tocqueville very clearly realizes that slavery damages southern white people as well as the southern economy. Because of slavery, southern white people’s customs and character compare poorly with those of other Americans. Echoing Crèvecoeur and Jefferson, Tocqueville complains, “From birth, the southern American is invested with a kind of domestic dictatorship…and the first habit he learns is that of effortless domination…[which turns] the southern American into a haughty, hasty, irascible, violent man, passionate in his desires and irritated by obstacles. But he is easily discouraged if he fails to succeed at his first attempt.” While impatience robs southerners of the determination necessary to succeed, energy constitutes the American’s great talent: he goes about taming the wilderness and wrenching riches from the land. Not the southerner. “The southerner loves grandeur, luxury, reputation, excitement, pleasure, and, above all, idleness; nothing constrains him to work hard for his livelihood and, as he has no work which he has to do, he sleeps his time away, not even attempting anything useful.”34

The severity of discrimination against African Americans alarms Tocqueville, prompting his prediction of an inevitable war of the races that will entail “great misfortunes”: “If America ever experiences great revolutions, they will be instigated by the presence of blacks on American soil; that is to say, it will not be the equality of social conditions but rather their inequality which will give rise to them.”35

While the danger of “revolution” presses imminently in the South, the North enjoys no exemption. The specter of race war “constantly haunts the imaginations of [all] Americans like a nightmare,” but Tocqueville leaves his fears with that.36 Pursuing this line of thought would distort his egalitarian image of the United States. In truth, Tocqueville does not know what to do with the problem of slavery or how to integrate the South into his depiction of the United States. Revolutions do not arise on a level playing field, and he needs a level playing field to justify his sunny, democratic analysis. He solves his conundrum by cutting the South, slavery, and black people out of his theory, admitting, in a footnote in volume 2 that only Americans living in the free states conform to his image of a democratic, egalitarian society.37

The Ohio River offers a convenient dividing line. In Ohio, the American, driven to succeed, achieves through ingenuity. South of the Ohio River in slaveholding Kentucky, the southerner disdains labor: “living in a relaxed idleness, he has the tastes of idle men; money has lost a part of its value in his eyes; he is less interested in wealth than excitement and pleasure…. Slavery, therefore, not merely prevents the whites from making money but even diverts them from any desire to do so.” Northerners own the ships that ply the nation’s rivers and seas, the factories that produce untold wealth, the railroads that deliver produce to market, and canals that link the continent’s great natural waterways.38 Only the North possesses these symbols of America.

This long and tortured chapter seldom figures in the broadcast image of Tocqueville’s United States. Little read and less often heeded, it has even been omitted from abridged editions. Whether or not literally cleansed of anything pertaining to race war and the general American nastiness surrounding questions of race, Tocqueville’s America does not face all its racial facts.39* As he finally walks away from the topic of multiracial America, Tocqueville excuses the brevity of his own discussion by sending readers along to the novel of his friend Beaumont.

GUSTAVE DE BEAUMONT (1802–66), Tocqueville’s fellow lawyer, roommate in Versailles in the 1820s, traveling companion, lifelong friend, biographer, and literary executor, accompanied him in travels across the United States and Ireland in 1835. (See figure 8.4, Gustave de Beaumont.) Beaumont, not so theory driven, took more interest than Tocqueville in slavery and the conventions of racial identity. His sociological novel, Marie, ou L’esclavage aux États-Unis, tableau de moeurs américaines (Marie, or Slavery in the United States, a Picture of American Manners) in fact made slavery an integral, rather than an incidental, facet of American society. Marie appeared in two volumes in 1835, the same year as the first volume of Tocqueville’s Democracy in America. Both books won the Prix Montyon of the Académie Française, and both authors were elected members of the Académie des Sciences Morales et Politiques, but only Tocqueville was eventually inducted into the far more prestigious Académie Française, after an assiduous campaign for acceptance.

In his novel, Beaumont’s protagonists are Ludovic, a French immigrant to the United States, and his beloved American, Marie, the daughter of parents who both look white: a Bostonian father and a mother who grew up in New Orleans. According to American mores, Beaumont says, the father really is white; the mother is not. Marie’s Louisianan mother, whose great-grandmother was a mulatto, transmits to Marie the invisible taint of black blood. Although Marie’s imperceptible mixed ancestry does not dissuade her French suitor Ludovic, Americans’ one-drop rule makes her black even in the so-called free North. Marie’s drop of blackness marks her marriage to the Frenchman as miscegenation, an infraction sufficient to inspire a riot in New York City.* The marriage cannot proceed. Ludovic and Marie seek peace in the wilds of Michigan. But before they can settle down, Marie dies. Ludovic remains an exile in the wilderness.

Despite his novel’s grim message, Beaumont evinces a sly sense of humor. In the foreword to Marie, he relates an anecdote illustrating Americans’ preposterous racial rules. Although the theater was actually in New Orleans, Beaumont relates the incident as though taking place in Philadelphia:

Fig. 8.4. Gustave de Beaumont, 1848.

The first time I attended a theater in the United States [in October 1831], I was surprised at the careful distinction made between the white spectators and the audience whose faces were black. In the first balcony were whites; in the second, mulattoes; in the third, Negroes. An American, beside whom I was sitting, informed me that the dignity of white blood demanded these classifications. However, my eyes being drawn to the balcony where sat the mulattoes, I perceived a young woman of dazzling beauty, whose complexion, of perfect whiteness, proclaimed the purest European blood. Entering into all the prejudices of my neighbor, I asked him how a woman of English origin could be so lacking in shame as to seat herself among the Africans.

“That woman,” he replied, “is colored.”

“What? Colored? She is whiter than a lily!”

“She is colored,” he repeated coldly; “local tradition has established her ancestry, and everyone knows that she had a mulatto among her forebears.”

He pronounced these words without further explanation, as one who states a fact which needs only be voiced to be understood.

At the same moment I made out in the balcony for whites a face which was very dark. I asked for an explanation of this new phenomenon; the American answered:

“The lady who has attracted your attention is white.”

“What? White! She is the same color as the mulattoes.”

“She is white,” he replied; “local tradition affirms that the blood which flows in her veins is Spanish.”

Following the anecdote, Beaumont explains the deadly meaning of race prejudice in the United States. Echoing Crèvecoeur and Jefferson, he concludes that white supremacy in America corrupts white people by schooling them in “domination and tyranny,” while blasting Negro fate and engendering in them violent hatreds and resentments bound to provoke bloody crisis.40

Although as much an aristocrat as Tocqueville, Beaumont deeply disagrees with his friend over the nature of U.S. society. Tocqueville, it seems, can only see a virtuous democracy where Beaumont focuses on barriers as impassable as Europe’s. White Americans, Beaumont concludes, belong to a hereditary aristocracy by dint of a mythology driven by the notion of tainted blood and a belief in invisible ancestry. This fact alone suffices to destroy the possibility of a true democracy. David Walker’s indictment of hypocrisy reappears.

Beaumont’s mouthpiece Ludovic instructs a young traveler from France who is drawn to the United States by “the laws and customs of this country; they are liberal and generous. Every man’s rights are protected here.” Not so, advises Ludovic, who having lived with a family of color, knows that such impressions are mere “illusions” and “chimeras.”41

THESE TWO seminal books—very much two sides of the same coin—experienced contrasting fates in translation. Democracy in America was translated into English immediately upon publication in 1835, but Marie had to wait 123 years, until 1958, for its first English translation. An accessible paperback in English did not appear anywhere for 164 years, when published in 1999 by the Johns Hopkins University Press. One fact, a title change, says much about the elevation of Tocqueville at the expense of Beaumont: in 1938 George Wilson Pierson published Tocqueville and Beaumont in America, a scholarly analysis based on their notebooks and letters. When Johns Hopkins University Press republished Pierson’s book in 1996, its contents unaltered, Beaumont had disappeared from the title, now simply Tocqueville in America. Thus quietly but definitely, Beaumont and his troubled, multiracial United States ceded place to Tocqueville’s egalitarian, democratic, white male America.

Walker, Easton, and Beaumont, each in his own way, cast a wary eye on the myth of American democracy. Concurrently, another story was playing in the history of American whiteness.