9

THE FIRST ALIEN WAVE

Two centuries ago, Americans had already fallen into a number of thought patterns familiar to us. In a society largely based on African slavery and founded in the era that invented the very idea of race, race as color has always played a prominent role. It has shaped the determination not only of race but also of citizenship, beauty, virtue, and the like. The idea of blackness, if not the actual color of skin, continues to play a leading role in American race thinking.

Today’s Americans, bred in the ideology of skin color as racial difference, find it difficult to recognize the historical coexistence of potent American hatreds against people accepted as white, Irish Catholics. But anti-Catholicism has a long and often bloody national history, one that expressed itself in racial language and a violence that we nowadays attach most readily to race-as-color bigotry, when, in fact, religious hatred arrived in Western culture much earlier, lasted much longer, and killed more people. If we fail to connect the dots between class and religion, we lose whole layers of historical meaning. Hatred of black people did not preclude hatred of other white people—those considered different and inferior—and flare-ups of deadly violence against stigmatized whites.

By 1850, a prideful Saxon-American juggernaut was elevating Protestant Americans above Catholics of all classes and provenance. Obviously Irish Catholics were white, and, especially in the South, white enough to hold themselves above black and Chinese people in the name of whiteness. As Celts, however, the poor Irish could also be judged racially different enough to be oppressed, ugly enough to be compared to apes, and poor enough to be paired with black people.

Before about 1820, most Irish immigrants had been Protestants from the north of Ireland, fairly easily incorporated into American society as simply “Irish.” On the other hand, Irish Catholic immigration, while moderate before 1830, had now and then drawn Federalists and then Whigs toward nativist rhetoric, prompting the Protestant Irish to term themselves “Scotch Irish,” as distinguished from Catholics.1 And after 1830, as hardship in Ireland pushed the poor to America in growing numbers, opposition to them and their religion grew. To understand this antagonism we need some historical background.

ANTI-CATHOLIC LEGISLATION had long existed in the British colonies, inherited from the anti-Catholic struggles of England, led most notably by Henry VIII in the mid-sixteenth century and Oliver Cromwell during the mid-seventeenth-century English Civil War against Charles I. Various American colonial statutes forbidding, for example, the practice of the Roman Catholic religion, endured long past their rigorous enforcement. Until 1821 New York denied citizenship to Catholics unless they renounced allegiance to the pope in all matters, political or religious. In Massachusetts, all persons, Catholic and Protestant alike, were taxed to support state-sponsored Protestant churches until 1833. New Jersey’s constitution contained anti-Catholic provisions until 1844.2

When Ireland’s potato famine came to a crisis in the 1830s and 1840s, it turned the starving Irish into a sort of perverse tourist attraction. Intellectuals of all sorts, including Alexis de Tocqueville, Gustave de Beaumont, and Thomas Carlyle, sailed to Ireland to see for themselves whether such gut-wrenching reports could possibly be true. After their visit to the United States, Beaumont and Tocqueville toured Ireland and recorded their impressions. Tocqueville’s notes remained in manuscript until the mid-twentieth century, but Beaumont published his study as L’Irlande sociale, politique et religieuse (Ireland: Social, Political and Religious) in 1839.3

Before his time in Ireland, Beaumont had figured that parallels between American people of color and the Irish poor would make good sense. Thinking he had seen unmatched degradation in the United States—he considered Indians and Negroes “the very extreme of human wretchedness”—he was astonished to see in Ireland the worst of both American worlds: the impoverished Irish lacked the freedom of the Indian as well as the slave’s relative security. Consequently, “Irish misery [formed] a type by itself of which neither the model nor the imitation can be found anywhere else.” At bottom, Ireland lacked other countries’ varied histories, in which poor and rich played a part. For Beaumont, as for many others unable to see beyond the famine, Ireland had only a single essence: “the history of the poor is the history of Ireland.”4

Beaumont located the roots of the curse of Ireland in its history of pernicious British policy. Since occupying Ireland in the seventeenth century, Protestant English settlers had dispossessed the Catholic natives, depriving them of ownership or even unfettered use of the land, reducing them to abject poverty. Irish natives lived on potatoes, and when the potato blight destroyed this staple food, more than a million died of starvation. Twice that number emigrated, many to the United States. In the grimmest irony, while Irish people starved, Ireland was exporting food from settler-owned farms. Beaumont investigated this colonial history and drew his own conclusions. Blaming politics rather than the Irish themselves, he contradicted the prevailing assumption that inherent racial defects caused Irish wretchedness.

According to nineteenth-century popular wisdom and anthropological science, the Irish were Celts, a particular race separate from and inferior to the Anglo-Saxon English. Beaumont’s enlightened views would ultimately prevail, but at the time they found few supporters among the Western world’s theorists. Thomas Carlyle (1795–1881), the most influential essayist in Victorian England, held the racial-deficiency view, having fled Ireland’s scenes of destitution in disgust after brief visits in 1846 and 1849. In one cranky article he called Ireland “a human dog kennel.”5

From his perch in London, Carlyle saw the Irish as a people bred to be dominated and lacking historical agency. He took it for granted that Saxons and Teutons had always monopolized the energy necessary for creative action. Celts and Negroes, in contrast, lacked the vision as well as the spunk needed to add value to the world. Pushing the analogy further, Carlyle played on the antislavery question “Am I not a man and a brother?” But whereas the abolitionist query stresses the brotherhood of man, Carlyle refashioned the question to denigrate the oppressed. In his essay “The Present Time,” the first of several splenetic Latter Day Pamphlets (1850), he asks, “Am I not a horse, and half-brother?” then juxtaposes “Black Jamaica” and “White Connemara” as “our Black West Indies and our White Ireland.”6 The “sluttishly starving” Irish remind him of shiftless emancipated Negroes in the West Indies: “a Black Ireland; ‘free,’ indeed, but an Ireland, and Black!”7

Carlyle was hardly singular in turning the Irish into animals. A younger British Teutonist, the Oxford professor Charles Kingsley, termed the poor Irish “white chimpanzees.” Robert Knox in Scotland considered intermarriage between Saxons and Celts as much contrary to natural law as unions between Saxons and Hottentots.8

By the mid-1840s, as two million desperate Irish immigrants poured into the northern port cities of the United States, a backlash had developed. The Native American Party had appeared in New York City in 1835, and a number of anti-Catholic journals and organizations followed in New York and New England. Samuel F. B. Morse, father of the American telegraph, and Lyman Beecher, Yale-educated Presbyterian minister and father of the novelist Harriet Beecher Stowe and the Reverend Henry Ward Beecher, published slashing denunciations of Catholicism. Morse’s work carried windy titles: Foreign Conspiracy against the Liberties of the United States and Imminent Dangers to the Free Institutions of the United States through Foreign Immigration and the Present State of the Naturalization Laws, by an American. In it Morse evokes “the great truth, clearly and unanswerably proved,” that the Catholic monarchies of Europe, especially Austria and its allies the Jesuits, were sending “shiploads of Roman Catholic emigrants, and for the sole purpose of converting us to the religion of Popery.”9 Beecher’s Plea for the West accused Europeans of trying to subvert the Protestant virtues of American democracy, also by flooding the country with Catholics. In Beecher’s view it was tragic that poor Catholics could vote and hold office just like white men. In New York City and many another northeastern city, bourgeois voices joined those of Morse and Beecher in deploring “the very scum and dregs of Human nature” and the “low Irishmen” who decided election outcomes.10

In 1834, Beecher was heading the Lane Seminary in Cincinnati, a city housing a large number of Germans. From time to time, however, he returned to Boston, where he had lived during the 1820s. On one such occasion he preached three violently anti-Catholic sermons in a single day, and within twenty-four hours a mob had burned down the Ursuline convent school in neighboring Charlestown, setting off a wave of church burnings throughout New England and the Midwest.11 More obscenity was yet to come.

AFTER SERIAL publication in 1835, the sensational, pornographic Awful Disclosures of Maria Monk: The Hidden Secrets of a Nun’s Life in a Convent Exposed appeared in book form in 1836 and went on to sell some 300,000 copies by 1860. Second only to Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Awful Disclosures of Maria Monk became antebellum America’s most popular book.12

A Canadian born in 1816, Monk begins her exposé by explaining, “One of my great duties [as a nun] was to obey the priests in all things; and this I soon learnt, to my utter astonishment and horror, was to live in the practice of criminal intercourse with them.”13 Monk vividly describes priests’ rape of nuns, the murder of the offspring, and the beating to death of recalcitrant nuns. Monk’s story traced just one example of a favorite plot—the escaped nun’s tale—a more or less graphic depiction of a former Protestant girl seduced by a priest. Such books pictured the Catholic Church as inherently sexually immoral. Not only were Catholics not Protestant; they drank liquor, partied on the Sabbath, and had near-constant sex—especially in their convents and churches.14

Although investigation quickly disproved Monk’s allegations, the book excited nativists as much as later abolitionist descriptions of sex between masters and slaves. Failing to capitalize on her literary fame, Monk disappeared into the urban underworld and died in 1839 a poor, obscure, and abandoned single mother.15

While Monk’s ignominious end passed unnoticed, anti-Catholic hatred surged. Between 1830 and 1860, some 270 books, 25 newspapers, 13 magazines, and a slew of ephemeral publications carried on.16 This plethora of anti-Catholic newspapers included New York City’s The Protestant, the Protestant Vindicator (which had published Awful Disclosures of Maria Monk in serial form), and the Downfall of Babylon.

IN TRUTH, the era’s sociopolitical context had created much anxiety. The Western world was being buffeted by an extraordinary set of crises in the mid-1840s. In France, Germany, Italy, and central Europe, political unrest spurred by widespread unemployment and poverty culminated in revolution in 1848. Such uprisings crystallized the thinking of writers eager to interpret class conflict as race war. In France, Arthur de Gobineau wrote his Essay on the Inequality of Races, published in the mid-1850s. Robert Knox in London published his mean-spirited lectures on race in 1850 as Races of Men: A Fragment. The revolutionary year of 1848 also generated unrest among educated women and workers: the first conference for women’s rights took place in Seneca Falls, New York. In Great Britain, Chartists advocating workers’ rights and universal male suffrage presented their third (and last) People’s Charter to the House of Commons.* As Chartism was dying and revolutionary sentiment strengthened throughout Europe, the Irish situation grew ever more desperate.

Ireland attracted the most attention in English-speaking lands, but continental Europe, where background conditions were similar, was sending distressed immigrants to the United States from German-speaking lands. Central Europeans were fleeing reactionary politics and the poverty caused not only by industrialization’s displacement of hand workers but also by failed harvests of wheat, wine, and potatoes. Such an upsurge of hard-pressed immigrants alarmed the U.S. government. For the first time, it answered the need to tabulate just how many desperate people were entering the country.

The U.S. census of 1850 was the first to collect statistics on immigrants. In a total population of 23,191,876, some 2,244,600 were deemed immigrants; among them, 379,093 from Great Britain, 583,774 from Germany, and a whopping 961,719 from Ireland. In the years of hardship in western Europe, especially 1845–55, 1,343,423 came from Ireland and 1,011,066 from the German-speaking lands.17

The Germans were a heterogeneous group in terms of wealth, politics, and religion. Settling largely in the Midwest in the “German Triangle” of Milwaukee, Cincinnati, and St. Louis, they stirred relatively little controversy, compared with the outcry against the Irish.18 For one thing, German Americans had been blending into Protestant white American life since before the Revolution, and many had climbed to the top of the nation’s economic ladder. Johann Jakob Astor, for instance, born near Heidelberg in 1763 and immigrating to the United States in 1784, was the richest man in the United States at his death in 1848. In the nineteenth century the Radical Republican Carl Schurz and the railroad magnate Henry Villard also presented a certifiably loyal image of middle-and upper-class German Americans.* Schurz had joined hundreds of other Germans turning to the United States after the failed revolutions of 1848. A taint of radicalism might dog them locally, but only sporadically did German radicalism raise the alarm on a national scale. The Catholic Irish were something else entirely.

SOME FIFTY thousand Irish lived in Boston by 1855, making the city one-third foreign born, the “Dublin of America.” There they found low-paying work in manufacturing, railroad and canal construction, and domestic service. Before long, Irishmen had gained a sorry reputation for mindless bloc voting on the Democratic (southern-based and proslavery) ticket, and also for drunkenness, brawling, laziness, pauperism, and crime. All these defects attached to the figure of “the Paddy.”

When Ralph Waldo Emerson, the leading American intellectual before the Civil War, casually referred to poor Irishmen as “Paddies,” he drew upon stereotypes of improvidence and ignorance as old as Sir Richard Steele’s 1714 description of “Poor Paddy,” who “swears his whole Week’s Gains away.”19 As a young minister in the late 1820s, Emerson posited a multitude of inferior peoples that included Irish Catholics. Cataloging the traits of backward races, he set stagnation atop the list, as though stagnation ran in the blood of human beings. Over the years Emerson’s cast of incompetent races would rotate indiscriminately around the globe, but two peoples nearly always figured: the African and the Irish. In a very early musing, Emerson actually expels the Irish from the Caucasian race:

I think it cannot be maintained by any candid person that the African race have ever occupied or do promise ever to occupy any very high place in the human family. Their present condition is the strongest proof that they cannot. The Irish cannot; the American Indian cannot; the Chinese cannot. Before the energy of the Caucasian race all the other races have quailed and ser done obeisance.

That was in 1829. Nothing had changed by 1852, when Emerson wrote,

The worst of charity, is, that the lives you are asked to preserve are not worth preserving. The calamity is the masses. I do not wish any mass at all, but honest men only, facultied men only, lovely & sweet & accomplished mwomen only; and no shovel-handed Irish, & no Five-Points, or Saint Gileses, or drunken crew, or mob or stockingers, or 2 millions of paupers receiving relief, miserable factory population, or lazzaroni, at all.20

Here we have the heart of Emerson’s view of the poor, typified by the Irish.

After the failure of the Hungarian revolution in 1848 and Lajos Kossuth’s triumphant tour as a hero in exile, Emerson found a way to view the Hungarian situation through an Irish lens: “The paddy period lasts long. Hungary, it seems, must take the yoke again, & Austria, & Italy, & Prussia, & France. Only the English race can be trusted with freedom.”21 Emerson pontificated against Central Europeans as well as the Irish: “Races. Our idea, certainly, of Poles & Hungarians is little better than of horses recently humanized.”22

Emerson would probably not have been surprised that Polish jokes abounded in the late twentieth century. Certainly during his time Paddy jokes amused the better classes, having been recycled from eighteenth-century English “jester” books. This one about the two sailors, one a dumb Irishman, lived for more than a century:

Two sailors, one Irish the other English, agreed reciprocally to take care of each other, in case of either being wounded in an action then about to commence. It was not long before the Englishman’s leg was shot off by a cannon-ball; and on his calling Paddy to carry him to the doctor, according to their agreement, the other very readily complied; but he had scarcely got his wounded companion on his back, when a second ball struck off the poor fellow’s head. Paddy, who, through the noise and disturbance, had not perceived his friend’s last misfortune, continued to make the best of his way to the surgeon, an officer observing him with a headless trunk upon his shoulders, asked him where he was going? “To the doctor,” says Paddy. “The doctor!” Says the officer, “why you blockhead, the man has lost his head.” On hearing this he flung the body from his shoulders, and looking at it very attentively, “by my soul, says he, he told me it was his leg.”23*

Cartoons played an important role in reinforcing the Paddy stereotype. Frequently apelike, always poor, ugly, drunken, violent, superstitious, but charmingly rascally, Paddy and his ugly, ignorant, dirty, fecund, long-suffering Bridget differed fundamentally from visual depictions of sober, civilized Anglo-Saxons. (See figure 9.1, “Contrasted Faces.”) Most Paddy phrases—such as “Paddy Doyle” for a jail cell, “in a Paddy” for being in a rage, “Paddyland” for Ireland, and “Paddy” for white person—have lost currency in today’s vernacular; only “paddy wagon” endures to link Irishmen to the American criminal class.

Fig. 9.1. “Contrasted Faces,” Florence Nightingale and Bridget McBruiser, in Samuel R. Wells, New Physiognomy, or Signs of Character, Manifested through Temperament and External Forms, and Especially in “The Human Face Divine” (1871).

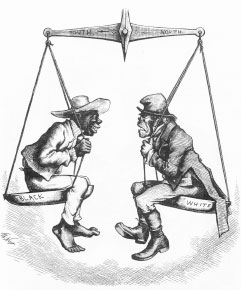

AMERICAN VISUAL culture testifies to a widespread fondness for likening the Irishman to the Negro. No one supplied better fodder for this parallel than Thomas Nast, the German-born editorial cartoonist for Harper’s Weekly. In 1876, for instance, Nast pictured stereotypical southern freedmen and northern Irishmen as equally unsuited for the vote during Reconstruction after the American Civil War. (See figure 9.2, Nast, “The Ignorant Vote.”)

This cartoon does two things at once: It draws upon anti-Irish imagery current in Britain and the United States, and depicts both figures in American racial terms. Bumpkin clothing and bare feet mark the figure labeled “black” as a poor rural southerner, while the face, expression, and lumpy frock coat of the “white” figure are stereotypically Irish. It is important here to recognize that the Irish figure is not only problematical but also, and most importantly, labeled white. Nast drew for a Republican journal identified with the struggle against slavery. However, figures on the other side of the slavery issue could just as easily draw the black-Irish parallel. James Henry Hammond, nullifier congressman, U.S. senator, and governor of South Carolina, denounced the British reduction of the Irish to an “absolute & unmitigated slavery.”24 And George Fitzhugh in Cannibals All! or Slaves without Masters (1855) intended his Irish comparisons to prove that enslaved workers fared better than the free.25 Fitzhugh hardly meant to recommend freedom to either poor community.

Fig. 9.2. Thomas Nast, “The Ignorant Vote—Honors Are Easy,” Harper’s Weekly, 1876.

Abolitionists saw the other side of the coin, frequently championing kindred needs for emancipation. In the 1840s, Garrisonians made Irish Catholic emancipation an integral part of their campaign for universal reform. Visiting the United States, Daniel O’Connell (1775–1847), the first Catholic since the Reformation to sit in the British House of Commons, the leading Irish champion of Catholic emancipation, and an indefatigable campaigner for Irish independence, saw the needs of starving Irish and enslaved blacks as analogous. The American abolitionists Wendell Phillips and Frederick Douglass adopted the same rhetorical ploy. In a visit to Ireland in the famine year of 1845, Douglass likened the circumstances of Ireland’s poor to those of enslaved black people. Such a tragic physiognomy of the two peoples wrenched his heart: “The open, uneducated mouth—the long, gaunt arm—the badly formed foot and ankle—the shuffling gait—the retreating forehead and vacant expression—and their petty quarrels and fights—all reminded me of the plantation, and my own cruelly abused people.” The Irish needed only “black skin and wooly hair, to complete their likeness to the plantation Negro.”26 For Douglass and other abolitionists, the tragedy of both peoples lay in oppression. Neither horror stemmed from weakness rooted in race.

One group, however, utterly repudiated the notion of black-Irish similarity, and that was the Irish in the United States. Irish immigrants quickly recognized how to use the American color line to elevate white—no matter how wretched—over black. Seeking fortune on the white side of the color line, Irish voters stoutly supported the proslavery Democratic Party. By the mid-1840s, Irish American organizations actively opposed abolition with their votes and their fists. In the 1863 draft riots that broke out in New York and other northeastern cities, Irish Americans attacked African Americans with gusto in a bloody rejection of black-Irish commonality. In Ireland and in Britain, too, cultural nationalists seeking to shed racial disadvantage counterattacked, forging a Celtic Irish history commensurate with that of Anglo-Saxonists.*

While Ireland’s political struggle for independence from Britain delayed an Irish dimension of the Celtic literary revival until late in the nineteenth century, political Irish nationalism had flourished long before the struggle for Irish independence succeeded in 1921. Irish nationalists could turn Saxon chauvinism inside out in ways similar to those of abolitionists like David Walker. In 1839 Daniel O’Connell won over American abolitionists’ hearts with a scathing condemnation of American imperialism. Abolitionists advocated peace, as expansionists were lusting after a seizure of Mexican territory: “There are your Anglo-Saxon race! Your British blood! Your civilizers of the world…the vilest and most lawless of races. There is a gang for you!…the civilizers, forsooth, of the world!”27 For O’Connell, Anglo-Saxons were nothing but natural-born thieves. At the same time, two non-Irish litterateurs laid a basis for the study of Celtic literature.

In the mid-nineteenth century, the French philosopher Ernest Renan (1823–92) and the English cultural critic and poet Matthew Arnold (1822–88) offered admiring portraits of the mystic, romantic, and doomed Celtic race in Poetry of the Celtic Races (1854) and On the Study of Celtic Literature (1866). Renan was a highly respected philosopher of religion, Arnold, one of Britain’s leading poets and literary critics. Their works, both very mixed blessings, were evidently meant to be affectionate. But in praising the Irish closeness to nature as a salutary counterweight to Anglo-Saxon and Teutonic modernity, Renan and Arnold reduced them into dumb, pathetic natives.

Witness Renan. Originally from Brittany, France’s self-proclaimed Celtic homeland, Renan fondly cites the natural Christianity of “that gentle little race,” the Celts. “The Teutons,” in contrast, “only received Christianity tardily and in spite of themselves, by scheming or by force, after a sanguinary resistance, and with terrible throes.” Compared with the brutal Teutons, the avatars of modernity, Renan’s Celts are childlike and superstitious, of all nations the “least provided [with]…practical good sense.”28 In the face of the onrushing, mechanized world of industry, this is meant as a compliment.

Arnold’s portrait drips with similar presumption. Claiming distant connection to Celts through his mother, yet identifying himself firmly as Saxon, Arnold sets the racial characteristics of Saxon-English in opposition to those of the Celtic Irish: Because “balance, measure, and patience” are ever required for success, even when a race has the most fortunate temperament “to start with,” the Celtic Irish are doomed. For “balance, measure, and patience are just what the Celt has never had.” Arnold extended Celtic incapacity even further: “And as in material civilisation he has been ineffectual, so has the Celt been ineffectual in politics.” In fact, Arnold serenely predicts failure for the race: “For ages and ages the world has been constantly slipping, ever more and more, out of the Celt’s grasp. ‘They went forth to war,’ Ossian says most truly, ‘but they always fell.’”29

Here is a puzzlement. How could any of this have pleased the Celts? And yet, believe it or not, Renan and Arnold actually counted as friends of the Celtic race at the time. Arnold’s campaign for a chair in Celtic studies at Oxford University succeeded in 1877, and he and Renan were praised for encouraging the late nineteenth-and early twentieth-century flowering of an Irish renaissance. True, their depiction of Celts had a distinctly racial flavor. But race was in the air at the time, and the alternative to Renan’s and Arnold’s patronizing lay in insults from the likes of Thomas Carlyle.

Defenders of the Celtic Irish race replied to English Saxon chauvinism with an older and more Christian version of their racial history. The popular, multivolume History of the Anglo-Saxons (1799–1805) by the English historian and bookseller Sharon Turner provided the template by portraying the modern English as direct descendants of Dark Age Saxons. So Irish nationalists could do that, too—and they did—claiming their pure descent from a bevy of ancient and luminous Celtic ancestors. There were, for instance, the prehistoric Firbolgs, Tuatha de Danann, and the followers of King Milesius from Spain, said to be the invaders of Ireland 1,500 to 1,000 years before the birth of Christ. Furthermore, Milesians traced their history back to Scythia (Ukraine and Russia), via Scota, an Egyptian pharaoh’s daughter who gave her name to the Scots.*

Whether friends or foes, British intellectuals seeking root causes of Irish distress rarely rose above the doubt that the Irish, as Celts and as Catholics, possessed any racial qualities for greatness. On the other side of the Atlantic, however, race functioned differently in the long run.

As we have seen, Irish people lived in disparate political cultures. In Britain and Ireland they were labeled as Catholic Celts, linked by race with the despised French. In the United States their situation was more complex. In Britain and Ireland religion carried far more weight than in the United States. Religious wars, after all, had long raged over England; for centuries Britain had dubbed Anglicanism the national, Protestant religion. In the United States no sect enjoyed constitutional recognition. The United States also lacked a long history of antagonism and entanglement with Catholic France. No wars had been fought over religion in North America, and no long history implanted religious identity at the root of American national consciousness. So while an aversion to Catholicism and Catholics was hardly a trivial facet of American life and could flare up in deadly violence, it never defined American identity over the long haul.

And then there was the ugly history of British colonialism and Ireland’s situation as a colony. England was, first and foremost, a colonial power centuries before the Act of Union of 1800 purportedly united the Irish and British crowns. During the nineteenth century, a question festered—what to do with Ireland? The firm assumption that the Irish were unfit for self-government often dominated domestic politics. The United States had black people and slavery to contend with, issues so huge that they blunted anti-Irish sentiment as a source of political conflict, but not before a decade of turmoil. As we have already noted, the 1840s were a tense time in the United States, an era of rising nativism.

THE BLOODSTAINED Order of United Americans first appeared in New York City in 1844 and soon spread to Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Connecticut. Catholic churches had been torched now and then since the mid-1830s (actually black churches, too, but not on account of religion). In 1834 a nativist mob had burned the Convent of the Ursuline nuns in Charlestown, Massachusetts. Now arson became endemic, climaxing in Philadelphia in 1844, when a mob of six hundred self-proclaimed American Republicans burned down St. Michael’s and St. Augustine’s Catholic churches and torched many Irish residences. The rioting lasted three days, killing thirteen and wounding fifty.30 In Pittsburgh in 1850 a candidate running on the “People’s and Anti-Catholic” ticket won the mayoral race. During the 1850s Massachusetts and Connecticut enacted voter literacy tests in an attempt to curtail immigrant Democratic voting power.31 By the mid-1850s clubs of the Order of United Americans flourished in sixteen states.32

Much early anti-Catholic violence was more or less spontaneous and poorly organized, driven by fear that the Irish would lower wages or increase crime. But nativism gained an important institutional basis with the founding in New York City, in about 1850, of the secret Supreme Order of the Star-Spangled Banner. Members soon became labeled “know-nothings” because they customarily responded to queries about their order with “I know nothing.” Members had to be men born in the United States of native-born parents. Natives married to Catholics could not join. Know-Nothings had a broad agenda that differed according to their class and their region. They especially hated Catholics, but they also opposed liquor and political corruption. In New England, they challenged the mass voting of immigrants for the proslavery Democratic Party.

In terms of their tactics, Know-Nothing clubs like the Order of United Americans and the Supreme Order of the Star-Spangled Banner traded on patriotism. Most local chapters took the names of founding fathers or heroes and battles of the American Revolution.33 A political party spun out of the Supreme Order of the Star-Spangled Banner was actually named the American Party. So patriotic a title encouraged members to brand opponents “anti-American.” In the Midwest, for instance, where Germans had settled and voted in large numbers, refugees from the European revolutions of 1848 almost automatically seemed anti-American on account of their suspected radicalism.

Such frequent mob violence made riot the signature Know-Nothing activity: against Irish people, against Catholic churches, and against other parties’ voters. Matters grew worse with the 1853 visit of a papal envoy dispatched to arbitrate disputed church property claims, which riled up anti-Catholic secret orders and societies. At every stop along the envoy’s itinerary, the American and Foreign Christian Union incited mobs. In Cincinnati a crowd attempted to lynch him. Back east, in a decidedly bizarre event, a Know-Nothing mob assaulted a block of marble. The offending stone, taken from the Temple of Concord in Rome, was a gift from Pope Pius IX to be placed in the Washington Monument, still under construction. When the stone proved resistant to destruction, the mob dumped it into the Potomac River.

In 1854 a mob in Ellsworth, Maine, tarred and feathered a Catholic priest before nearly burning him to death. In Newark, New Jersey, Know-Nothings and Orangemen (Protestant Irishmen) from New York City broke the windows and statuary of St. Mary’s Catholic Church and killed an Irish Catholic bystander. Elections particularly excited passions. Know-Nothing mobs beat up opposition voters in several cities, including Washington and Baltimore. After the election riots of 1855 in Louisville, a priest reported “a reign of terror surpassed only by the Philadelphia riots [of 1844]. Nearly one hundred poor Irish have been butchered or burned and some twenty houses have been consumed in the flames.”34 Here was a war of religion, deadly while it raged.

Catholic-hating fervor swept Know-Nothings into office during the fall elections of 1854, as over a million followers in ten thousand local councils seized control of entire state governments.35 Massachusetts, New York, and six or seven other states elected Know-Nothing governors, and between seventy-five and a hundred congressmen as well as a host of state and local officials, including mayors in Boston, Philadelphia, and Chicago. (Numbers vary, owing to the difficulty of determining just who should be counted as a Know-Nothing. The movement went by an abundance of organizational names.) The future president Rutherford B. Hayes was moved to exclaim, “How people do hate Catholics.”36

On assuming power, Know-Nothings pushed a variety of measures opposing political corruption and promoting temperance, but Catholic immigrants remained the primary target. A bill was put forward to bar people not born in the United States from holding political office and to extend the waiting period for naturalization to twenty-one years. Such barriers and extensions would obviously have prevented many in the working class from voting, precisely the Know-Nothing intent. Like most Know-Nothing measures proposed by neophyte legislators, these failed to become law. In Massachusetts, however, Know-Nothings did manage to enact a nunneries inspection bill, which empowered legislators to inspect Catholic convents and schools, a mandate the legislators pursued with questionable enthusiasm.

Several luminaries played their part. Sam Houston (1793–1863), leader of the Texas revolution, president of the Republic of Texas, then governor and senator from the state of Texas, cobbled together a theory about the difference between old and new immigrants that functioned well into the twentieth century. For Houston, the founding fathers and heroes of the American Revolution constituted the fine old immigrants, in sharp contrast to the new immigrants of the 1850s, people “spewed loathingly from the prisons of England, and from the pauper houses of Europe.”37

Ulysses S. Grant (1822–85), only a decade from the U.S. presidency, pitied himself for his lack of “privileges” compared with German job seekers who seemed to have all the luck. During the Civil War, seizing a chance to legalize his prejudices, Grant enacted one of the rare nineteenth-century anti-Semitic policies. Called General Orders No. 11, it expelled all Jews, including families with children, from the Department of Tennessee in December of 1862. Grant’s excuse? He insisted that he had to control Jewish peddlers. In fact, his directive affected all Jews in Tennessee, no matter their vocation, sex, or age. President Abraham Lincoln quickly rescinded the order, but not before several families were displaced.38

In the South, Know-Nothings also did well in the mid-1850s elections. An Alabama Know-Nothing congressman spoke for many when he declaimed, “I do not want the vermin-covered convicts of the European continent…. I do not want those swarms of paupers, with pestilence in their skins, and famine in their throats, to consume the bread of the native poor. Charity begins at home—charity forbids the coming of these groaning, limping vampires.”39 This kind of proclamation played as well in the South, with its few immigrants, as in the North, with its many.

Eventually, as we know, fundamental political tensions destroyed Know-Nothingism as slavery—the elephant in the American living room—bumped about more aggressively. In 1855 the question of slavery in the Nebraska Territory set southern Know-Nothings on one side, demanding explicit safeguards for slavery, and northerners on the other, refusing to go along. Once the slavery issue split the Know-Nothing movement along sectional lines, the newly founded Republican Party picked up northern Know-Nothings unwilling to bow to southern devotion to slavery. In the South, Know-Nothings rejoined or ceded to Democrats. The split did not signal the definitive end of nativism. For instance, the Know-Nothing candidate for president in 1856, the former Whig president Millard Fillmore, polled some 800,000 votes, or over one-fifth of those cast nationwide, although he carried only the state of Maryland. Democrats elected James Buchanan of Pennsylvania, their last successful presidential candidate until the 1884 election of Grover Cleveland. Slowly the worst violence associated with Catholic hating in the United States ended, but poor Irish Catholics remained a race apart—Celts. At the same time, nine-tenths of African Americans remained enslaved, and they were not only abused as an inferior race: they were seldom counted as Americans. Towering over the notion of two inferior races, Celt and African, the figure of the Saxon monopolized the identity of the American. But at least the Celts had their whiteness.