10

THE EDUCATION OF RALPH WALDO EMERSON

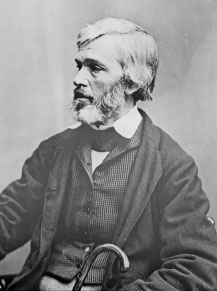

Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803–82) towers over his age as the embodiment of the American renaissance, but not, though he also should, as the philosopher king of American white race theory. Widely hailed for his intellectual strength and prodigious output, Emerson wrote the earliest full-length statement of the ideology later termed Anglo-Saxonist, synthesizing all the salient nineteenth-and early twentieth-century concepts of American whiteness. (See figure 10.1, Ralph Waldo Emerson.)

A quintessential New Englander born in Boston, Emerson descended from a family of scholarly ministers whose American roots reached back to 1635. Emerson’s esteemed father, the Reverend William Emerson, had delivered a Phi Beta Kappa address at Harvard—just as his son would a generation later—and served as pastor at Boston’s First Church. Such a lofty perch, while conferring eminent respectability, did not guarantee financial security even while the Reverend William Emerson lived. His death, when Waldo was not quite eight years old, plunged the family into outright hardship. Luckily Waldo’s diminutive aunt—she stood four feet three inches tall—Mary Moody Emerson (1774–1863) was there to fill a crucial gap in his education at home.*

An 1814 American edition of de Staël’s On Germany had introduced German romanticism and the wisdom of India to intellectual Americans like Mary Moody Emerson. She kept the book at hand throughout her life and used it to transmit her enthusiasm for de Staël and German romanticism to her nephew before, during, and after his formal studies.1 He had a good, traditional New England education, attending the Boston Latin School, then following his forebears to Harvard College, where he waited on tables to cover tuition. He taught school for four years before enrolling in the Harvard Divinity School, which he left as a Unitarian minister in 1829. That same year he married Ellen Louisa Tucker and became minister of Boston’s Second Church.

EMERSON’S FASCINATION with German thought was practically foreordained. At Harvard he studied with the confirmed romanticists George Ticknor and Edward Everett, two young scholars recently returned from studies at Göttingen’s Georg-August University. Well schooled by Aunt Mary, Emerson had incorporated her comments into his Harvard senior essay, winning second prize in 1821. Even his older brother, William, pitched in, going abroad to study at Göttingen in 1824–25 and writing home to Waldo urging him “to learn German as fast as you can” in order to follow him to Germany.2

Fig. 10.1. Ralph Waldo Emerson carte-de-visite.

German thought filled the air around Boston’s young intellectuals. In the 1820s Emerson read English writers like Samuel Taylor Coleridge, who had studied at Göttingen with Blumenbach,3 and William Wordsworth, both necessary guides into things German since Emerson never gained great competence in the German language. All in all, his Harvard study, Aunt Mary Moody Emerson’s keenness for German romanticism, and Germaine de Staël’s On Germany propelled Emerson ever deeper into study of German philosophy and literature.

TRANSCENDENTALISM, THE American version of German romanticism (à la Kant, Fichte, Goethe, and the Schlegel brothers), flourished in New England, particularly in eastern Massachusetts, from the mid-1830s into the 1840s. German transcendentalism offered an odd mixture, including even a hefty dose of Indian mysticism inspired by Friedrich von Schlegel, which Mary Emerson had also found congenial.* In place of established Christian religion (particularly the then prevailing Unitarianism), transcendentalism offered a set of romantic notions about nature, intuition, genius, individualism, the workings of the Spirit, and, especially, the character of religious conviction. At bottom, it prized intuition over study and emphasized the idea of an indwelling god who unified all creation. Guided by Aunt Mary, Emerson borrowed transcendentalism’s focus on nature as a spiritual force for his essay Nature (1836), now considered the transcendentalists’ manifesto.4†

Most leading New England transcendentalists had attended Harvard College, and many had continued into Harvard’s Divinity School preparing for the Unitarian ministry. Emerson fits the mold perfectly in several ways, as a minister and as one who resigned his pulpit after a crisis of faith. Even after leaving the ministry, however, Emerson remained intrigued throughout his life by the religious dimension of transcendentalism. In Nature he announces American transcendentalism as a new way of conceiving spirituality, amplified two years later in his classic Divinity School Address.*

WITHIN THIS German-driven transcendental swirl, one man, an Englishman, stood tallest: he was Thomas Carlyle (1795–1881). (See figure 10.2, Thomas Carlyle.) A reedy, stooped six-footer and a lifelong hypochondriac, Carlyle was usually half sick with a cold. The twenty-four-year-old Emerson (also tall, thin, and hypochondriac) discovered Carlyle’s unsigned reviews in the Edinburgh Review and the Foreign Review in 1827 and began to hail the British author as his “Germanick new-light writer,” as well as “perhaps now the best Thinker of the Saxon race.”5 Clearly Carlyle’s take on German mysticism would lay the foundation for American transcendentalism.

Actually, Carlyle was, geographically speaking, just barely a “Thinker of the Saxon race,” having been born in Scotland in the little town of Ecclefechan, eight miles from the English border.† This provenance counted heavily for Carlyle, who wished to be known as a southern Scot, that is, as a Saxon rather than a Celt—the northern Scots, to his mind being the latter and therefore, as we have seen in this mind-set, inferior.

After study at the University of Edinburgh, Carlyle, like many other English speakers, encountered German thought in de Staël’s On Germany in 1817. So impressed was he that he sent his future wife, Jane Welsh, a copy of de Staël’s novel Delphine. Furthermore, what he saw in On Germany—with its racial introduction, its elevation of Goethe to mythic status, and its concluding section on German transcendental mysticism—encouraged Carlyle to study German. This enthusiasm for the German language and its literature gained him employment as a German tutor in Scotland and motivated his translation of Goethe’s Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship in 1824, which he sent along to Goethe in Weimar. That opening inaugurated a respectful correspondence lasting until Goethe’s death in 1832.6

Carlyle actually came to think of Goethe as “a kind of spiritual father,” and took upon himself the task of spreading the transcendental gospel.7 And spread it he did, writing the magazine articles Emerson was reading in New England in the late 1820s and early 1830s, many of them reviews of German authors and essays on German thought.8 Like Carlyle, Emerson worshipped Goethe throughout his scholarly life. So thorough was this adoration that Goethe’s Italienische Reise shaped Emerson’s European itinerary of 1833, dictating a first stop in Rome.9 Emerson even began collecting Goethe statuettes and portraits and named the Emerson family cat “Goethe.”10

Emerson was thirty when he first saw Europe. By then he had left his pastorate and lost his beloved young wife to tuberculosis two years after their marriage. Now he poured energy into seeing for himself the luminaries of this new philosophy. Coleridge and Wordsworth came first, and both disappointed Emerson greatly. He found Coleridge “a short, thick old man [who] took snuff freely, which presently soiled his cravat and neat black suit.” Even worse was Wordsworth who abused the beloved Goethe and Carlyle and nattered on as though reading aloud from his books. Wordsworth later sneered at Emerson as well, calling him “a pest of the English tongue” and lumping him with Carlyle as philosophers “who have taken a language which they suppose to be English for their vehicle…and it is a pity that the weakness of our age has not left them exclusively to the appropriate reward, mutual admiration.” Emerson felt he had spent an hour with a parrot.11

Fig. 10.2. Thomas Carlyle.

The visit in Scotland with Carlyle, however, went perfectly. Much younger than Coleridge and Wordsworth, Carlyle captivated Emerson through a day and a night of passionate exchange chock full of fresh ideas expressed energetically. At this point neither man had published canonical work, but recognizing kindred spirits, they fell into each other’s arms, initiating a lifelong correspondence that even weathered ideological strains over slavery and the American Civil War. Mutual support immensely enhanced both their careers.

At the time of Emerson’s visit, Carlyle’s novel Sartor Resartus had reached the public only in magazine form, and little wonder, for this ponderous, autobiographical tale drags English readers through a morass of German transcendentalism and the mysticism of Immanuel Kant, with nothing of de Staël’s clarity. Carlyle’s novel is clotted with German, making it a hard sell in Britain; its protagonist, for instance, bears the challenging name Diogenes Teufelsdröckh. While a later admirer would pronounce Sartor Resartus part of a “great spiritual awakening of the Teutonic race,” at the time, only two readers that we know of lauded its magazine publication: a Father O’Shea of Cork, Ireland, and Ralph Waldo Emerson.12*

In fact, without Emerson’s tireless promotion, Carlyle’s writing career might have ended there. But Emerson took Carlyle’s novel in hand, shepherding an American edition into print and contributing a preface. With this help, the thumping, clamorous, and obscure style of Sartor Resartus electrified the Americans becoming known as transcendentalists: Theodore Parker spoke admiringly of a “German epidemic,” and William Ellery Channing experienced it as a “quickener” of his own ideas.13 Thanks to Emerson, an American edition of Carlyle’s French Revolution soon followed. The first money—£50—that Carlyle ever earned through his writing came from Emerson, acting as Carlyle’s agent in the United States over the course of several years.14 Indeed, Emerson made Carlyle more popular by far in America than he had ever been in Great Britain. Carlyle returned the favor, launching Emerson’s career in the United Kingdom with the 1841 publication of Essays. Carlyle’s advocacy had a number of English critics calling Emerson a Yankee genius, a sterling compliment since “genius” offered the romantics’ highest form of praise.

Given Emerson’s inability to read German very well, Carlyle stepped in as his teacher of transcendentalism, and not always an uncritical one. Early in their friendship Carlyle recognized the derivative nature of Emerson’s thought, explaining later “that Emerson had, in the first instance, taken his system out of ‘Sartor’ and other of [Carlyle’s] writings, but he worked it out in a way of his own.”15 Before meeting Emerson, the prominent English academic Henry Crabb Robinson, a founder of University College, London, had dismissed him as “a Yankee writer who has been puffed by [Carlyle] into English notoriety” but who was “a bad imitator of Carlyle who himself imitates Coleridge ill, who is a general imitator of the Germans.” (Once they met, Robinson’s view of Emerson softened.) John Ruskin’s estimation of Emerson wavered over time; at one point Ruskin, one of England’s leading intellectuals, considered Emerson “only a sort of cobweb over Carlyle.”16

This image of Emerson as a watered-down Carlyle-Teutonist never entirely dissipated, just as critics of Carlyle, Emerson, and transcendentalists have harped on the Teutonic opacity of their style. Southern critics, perhaps naturally, amplified these charges by tacking on an anti–New England, anti-antislavery twist. As the American sectional crisis deepened in the 1850s and Emerson spoke more pointedly against slavery and the slave power, a southern animus against him grew.17*

On the other hand, Americans adored Carlyle’s emphatic writing style and his apparent, if vague, sympathy for ordinary people and a disdain for the elite. Even Garrisonian abolitionists and feminists who advocated civil rights for all, seemed blind to the broader tendency of his politics. By 1840 Carlyle had come to despise their movement outright and deprecate the whole notion of universal human rights. Had they read him attentively, American fans would have realized this. But they did not. Antislavery Americans visiting London for the World Anti-Slavery Conference in 1840 unwittingly sought Carlyle out, ignorant of his approval of slavery as a perfectly appropriate labor regime for those he considered inferior races. Elizabeth Cady Stanton preserved an admiration for Carlyle even after he threw the visiting abolitionists out of his house. In the late 1860s, when abolitionists were splitting over the enfranchisement of poor black men (before educated white women got the vote), Stanton turned into a mean-spirited, Saxon chauvinist more in line with Carlyle’s thought. She happily quoted Carlyle’s Sartor Resartus to the detriment of people she considered inherently inferior.18

One notion guiding both Carlyle and Emerson, and supposedly liberal Americans like Stanton, was their heroic figuration of what they termed the Saxon race. Many other Americans—including Thomas Jefferson, the novelist Harriet Beecher Stowe, and Sarah Josepha Hale, editor of the most popular nineteenth-century American women’s magazine—proclaimed themselves Saxons.19* Most of these just briefly and easily looked back to “our Saxon ancestors,” before moving on, but Emerson dedicated an entire book to the subject, as we shall see. Cobbled together as race history, it drew on the eighth-century English historian Bede, Norse mythology, and many prevailing versions of English history, notably the (male) historian-bookseller Sharon Turner’s wildly popular The History of the Anglo-Saxons, from Their First Appearance above the Elbe, to the Death of Egbert, originally published in 1799 and in its seventh edition in 1852. Emerson owned a copy of the seventh edition and eagerly absorbed its Saxon chauvinism. Digging deep into Old Norse literature, Turner lumps Saxons and Norse together to come up with a list of undying “traits” of the English race. He proclaims liberty the first and foremost of these traits, which he believes persisted from the fifth-century Saxon/Norse conquest and had remained valid ever since. Like Thomas Jefferson, Turner contrasts the Anglo-Saxon tradition of liberty with the Norman inclination toward tyranny. However, Turner’s concept of a Norman “graft” onto England’s original Anglo-Saxon “stock” disagrees with Jefferson’s idea of permanently, racially pure Anglo-Saxons.20

Carlyle, who imagined himself a representative of Britain’s Norse heritage, infected his followers, including Emerson, with “we Saxon” jargon. Even the cosmopolitan Margaret Fuller, a foremost American interpreter of German romanticism, fell under the spell. On meeting Carlyle in London in 1846, Fuller portrays him admiringly, just the way he liked to be seen: “Carlyle, indeed, is arrogant and overbearing, but in his arrogance there is no littleness, no self-love: it is the heroic arrogance of some old Scandinavian conqueror—it is his nature and the untamable impulse that has given him power to crush the dragons…. [Y]ou like him heartily, and like to see him the powerful smith, the Siegfried, melting all the old iron in his furnace.”21

This Teutonic/Saxon race chauvinism increased in Carlyle and Emerson as they aged, but far more so in Carlyle. His identification with his Saxons as Germans seemed boundless, as he completely embraced German nationalism and Teutonic race chauvinism along the lines of Charles Villers and romantics like the two Schlegels, de Staël’s friends.22 As early as 1820, in his twenty-fifth year, Carlyle was already admiring German writers for the “muscle in their frames.”23 A decade later, he was delivering popular lectures on German themes. One of several 1837 lectures was entitled “On the Teutonic People, the German Language, the Northern Immigration, and the Nibelungen Lied,” the pagan German epic that later inspired Richard Wagner’s Ring cycle. It may seem odd to readers today, but when Carlyle spoke of “the German people,” he was including much of the population of Britain. In any case, Carlyle came to sound a lot like the willfully excerpted version of Germania by the Roman author Tacitus, which was then beginning to circulate among German nationalists. Alert to the values of his time, Carlyle sexes his German nationalism masculine.

His Germans are “the only genuine European people, unmixed with strangers. They have in fact never been subdued; and considering the great, open, and fertile country which they inhabit, this fact at once demonstrates the masculine and indomitable character of the race. They have not only not been subdued, but been themselves by far the greatest conquerors in the world.”24 Those themes of masculinity and race purity would soon reappear in Emerson, with masculinity of far greater consequence. On the matter of racial purity Emerson would waver.

But neither of them had a good word to say for France or the French people—an “Ape-population,” as Carlyle put it. France had turned revolutionary in 1789 and again in 1848, and Carlyle detested anything hinting of democracy. Such broad condemnation raised problems. What was one to make of the virile French Norman conquerors? Carlyle finessed that contradiction by pronouncing Normans to be Norsemen who had merely learned to speak French; obviously, for him, the change of language had not altered their blood, their basic nature, or their manly might. The Norman conquest had clearly benefited Britain, “entering with a strong man [William the Conqueror]…an immense volunteer police force…united, disciplined, feudally regimented, ready for action; strong Teutonic men.”25 All of this went quite a bit over the top, but American readers loved it. Carlyle might have trashed the French more lustily, but Emerson did his bit.

An 1835 lecture shows just how far Emerson would go. “Permanent Traits of the English National Genius” begins by connecting Americans to the English: “The inhabitants of the United States, especially of the Northern portion, are descended from the people of England and have inherited the traits of their national character.” As for the French, their early enemies may be trusted when they hold, “‘It is common with the Franks to break their faith and laugh at it. The race of Franks is faithless.’…An union of laughter and crime, of deceit and politeness is the unfavorable picture of the French character as drawn by the English and Germans, and even by the French themselves.”26 The unmanly vices of frivolity, corruption, and lack of practical know-how all afflicted the French. How else to view a people who invented the ruffle, while it took the English to invent the shirt?27* For manly practicality, look to the “English race.” For the childish, “singing and dancing nations,” look south.28 That north/south dichotomy would prove a durable theory, one Emerson trumpeted and his followers echoed, including his younger and rather priggish English admirer Matthew Arnold, ostensible defender of the beleaguered Celts.

Emerson and Carlyle outlined a transatlantic realm of Saxondom also taken up by Arnold, among many others. In his first letter after Emerson’s 1833 visit, Carlyle wrote, “Let me repeat once more what I believe is already dimly the sentiment of all Englishmen, Cisoceanic and Transoceanic, that we and you are not two countries, and cannot for the life of us be; but only two parishes of one country, with such wholesome parish hospitalities, and dirty temporary parish feuds, as we see; both of which brave parishes Vivant! vivant!”29 In the late 1830s Emerson was urging Carlyle to visit the United States, perhaps even to settle permanently: “Come, & make a home with me,” Emerson wrote.30 What a joy it would be to merge the intellects of Saxondom in their own two persons!

This rhetoric of bonding seemed to have no ceiling. In 1841 Carlyle, following Goethe’s infatuation with the ancient Greeks, wrote, “By and by we shall visibly be, what I always say we virtually are, members of neighboring Parishes; paying continual visits to one another. What is to hinder huge London from being to universal Saxondom what small Mycale was to the Tribes of Greece…. A meeting of All the English ought to be as good as one of All the Ionians….”31 And Emerson agreed. Enjoying a reputation for genius in Britain as well as the United States by 1853–55, he repeated a lecture entitled “The Anglo-American.” He might well have been speaking autobiographically in his comments on the “godly & grand British race”: “it is right to esteem without regard to geography this industrious liberty-loving Saxon wherever he works,—the Saxon, the colossus who bestrides the narrow Atlantic….”32 But in all this mutual admiration, a rift would soon appear.

Emerson saw himself as a New Englander, virtually as an Englishman, and therefore as a “Saxon.” “We Saxons” peppered his lectures, essays, and journals. In his classic 1841 essay “Self-Reliance,” Emerson exhorts his readers to wake up the “courage and constancy, in our Saxon breasts,” to realize that New Englanders are the final product of a process of distillation that had earlier turned Norsemen into Englishmen over the course of a millennium.* Later on, he would portray New Englanders as even more English than the English, as “double distilled English.”

Carlyle would not go that far. For all his Germanicism, Carlyle saw London as the natural capital of Saxondom for the present and foreseeable future. Perhaps later—probably much later—the capital might move west: “After centuries, if Boston, if New York, have become the most convenient ‘All-Saxondom,’ we will right cheerfully go thither to hold such festival….”33 Before long, this boil would fester and burst, for Emerson’s timetable sprang from a conviction that England was already practically worn out from excessive commercialism, labor troubles, and luxury. The Saxons on Americans’ side of the ocean, woodsmen who reminded Emerson of the Germans of Tacitus, would inherit the mantle of Saxon leadership sooner rather than later.†

Emerson did not visit Britain between 1833 and 1847. When he later did, he found Saxon identity weakening as a glue of friendship. Britain was enduring the economic hard times and suffering that would inspire Charles Dickens’s novel Hard Times (1854). The ever grumpy Carlyle grew more authoritarian, to the point that in 1848 he complained about Emerson’s equanimity: Emerson was “content with everything” and becoming “a little wearisome” with his “pleasant moonshiny lectures.” Emerson fired back, reporting that Carlyle “sits in his four-story house and sneers.”34 Basically, the friendship was over, but on one issue Emerson and Carlyle could still agree. Both looked askance at the Irish.

Carlyle termed the Irish “Human swinery,” playing on the commonplace analogy between Irish people and pigs. The Irish were believed to live with their pigs, and pigs were considered quintessentially Irish, as in the saying, “as Irish as Paddy’s pig.” Over in Concord, Massachusetts, where Irish laborers worked in mud and lived in shanties, Emerson saw no reason to dispute this libel. One of his rare comments on the districts of the poor, where he spent very little time, reveals both prejudice and naïveté: “In Irish districts, men deteriorated in size and shape, the nose sunk, the gums were exposed, with diminished brain and brutal form.”35 Like Carlyle in Chartism (1840), Emerson skirts the issue of whether race alone made the Irish ugly. On such an easy topic, the two found agreement.*

Then came the American Civil War. Emerson, no radical abolitionist, nonetheless opposed American slavery, particularly after the toughening of the Fugitive Slave Law in 1850 and John Brown’s raid on the Harpers Ferry, Virginia, federal arsenal in 1859. He also supported the Union during the war itself. Emerson did make a third and last trip to Europe, in 1872–73, only to find that he and Carlyle, both impaired by age, could no longer manage a meeting of the minds. Carlyle voiced a growing antipathy toward just about everybody. Gone were his youthful hints of sympathy for ordinary folk, an inclination always vaguely abstract. After his bitter pronouncements on what he called the “Nigger question” in 1850, he expressed no sympathy whatever with the poor, whether recently emancipated in the Western Hemisphere or despised and impoverished in Ireland and Britain.

But while their halcyon days may have gone, their influence lived on. Tutored in German race theory reaching back to Winckelmann and Goethe, each had become his country’s national voice, eloquently equating Americans with Britons and Britons with Saxons. The Anglo-Saxon myth of racial superiority now permeated concepts of race in the United States and virtually throughout the English-speaking world. To be American was to be Saxon.