16

FRANZ BOAS, DISSENTER

Born in Minden in Prussian Westphalia to middle-class parents, Franz Boas (1858–1942) had a sound German education. After attending a Protestant gymnasium, he studied at Heidelberg, Germany’s oldest university.* (See figure 16.1, Franz Boas.) Like many German undergraduates, he joined a fraternity (Burschenschaft) known for dueling and drinking. Interestingly, being Jewish did not stand in his way, for during the 1870s his Burschenschaft Allemannia accepted Jewish students; not until later in the century did Allemannia and other fraternities become exclusive anti-Semitic centers of German nationalism. After a semester at Heidelberg, Boas moved on to Bonn, then completed his graduate work at Kiel University, earning a Ph.D. in physics in 1881. Not that Boas escaped the barbs of German bigotry. In both Heidelberg and Kiel he had encountered Germany’s burgeoning anti-Semitism, from the “damned Jew baiters” who provoked “quarrel and fighting.”1 By the 1880s such harassment was becoming endemic, but Boas was able to avenge these insults, at least in part, through duels that left scars on his face, symbols of honorable, upper-class German manhood.

In 1881 Boas moved on to postgraduate work at Berlin with the pioneering German anthropologists Adolf Bastian and Rudolf Virchow (the latter considered a father of German anthropology), who taught him the physical anthropology of bodily measurement and alerted him to the possible influence of environment on head shape.2 No finer training could be had in Germany, but with anti-Semitism now closing in, his homeland hardly offered Boas a promising career. The German nationalist Berlin movement, led by its intellectual avatar, Professor Heinrich von Treitschke, had made overt hatred of Jews so widespread and respectable that Boas began to ponder emigration.3

An opportunity arose in 1883 to pursue his study of psychophysics (the relationship between physical sensation and psychological perception) far from Germany, in Anarniturg in the Arctic Cumberland Sound. There, living with the Inuit, he sought to perceive the environment as they did and to think like them. Those two years of fieldwork were useful and enjoyable. Even the hardships and strange food came to hold an appeal. Raw seal liver, he discovered, “didn’t taste badly once [he] overcame a certain resistance.”4

Fig. 16.1. Franz Boas.

Late nineteenth-century European anthropologists were typically both provincial and arrogant. They operated from two basic assumptions: the natural superiority of white peoples and the infallibility of elite modern science. Supposedly, scientific methodology endowed European scholars with universal knowledge. Boas might have accepted such dogma as a student, but during his time with the Inuit his independent streak took him toward diametrically opposite conclusions. Trying, for instance, to record and understand the Inuit language and failing, Boas realized that the fault lay not in the Inuit but in his own limitations. He began to see how hallowed European ways had disabled its scholars. “We [civilized people] have no right to look down on them,” he said of the Inuit, an almost unique, even heretical, thought at the time.

This breakthrough took Boas well toward the cultural relativism that would dominate twentieth-century anthropology. All knowledge, even Western knowledge, was relative and circumscribed: “our ideas and conceptions are true only so far as our civilization [i.e., our culture] goes.”5 To know everything worth knowing was impossible. And to know anything about other people required immersion in their world, to become, in a sense, one of them.

In the decade following 1885, Boas made several fieldwork trips to the Pacific Northwest and held a series of temporary positions, including stints at the American Museum of Natural History in New York, the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893, and G. Stanley Hall’s Clark University in Worcester, Massachusetts, then in its heady early years. Such wandering afforded refuge from Germany and sufficient time for research, but no financial security. Finally, in 1896, at the relatively advanced age of thirty-eight, he gained an appointment as lecturer in anthropology at Columbia University, joining a faculty that included the young luminary William Z. Ripley. Not that life had suddenly become cushy for Boas. Whereas Ripley had a choice of jobs and enjoyed generous remuneration, Boas began with temporary employment and a paltry salary at Columbia, evidently made possible only by his rich uncle’s underwriting. American anti-Semitism, then on the increase, doubtless played a role in such disparity.6

Even so, Boas quickly forged an international reputation as a careful yet innovative scholar. His colleagues soon came to respect his fieldwork and publications—they granted him tenure in 1899, when he was forty-one—even as he questioned their conventional notions of racial superiority and civilization. One such innovation appeared in Boas’s 1894 address to the Anthropology Division of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, called “Human Faculty as Determined by Race.” Its premises—that race, culture, and language are separate, independent variables and should not be confused—undergirded Boas’s classic book, The Mind of Primitive Man, first published in 1911 and revised in the late 1930s. But as statements applying to Americans, these points began to enter popular consciousness only in the 1930s, when anthropologists were becoming the experts on race. Boas’s Anthropology and Modern Life (1932) then emerged as a major scientific declaration.

One theme of the 1894 lecture questioned the evolutionary view of human races that equated whiteness with development and civilization. Downplaying anatomical differences between races, Boas looked to environment and culture rather than to race as shapers of people’s bodies and psyches. Here was the radical germ of cultural relativism, one fast attracting adherents, among them Paul Topinard, successor to Paul Broca and then the leading French anthropologist. Topinard applauded Boas’s thinking, declaring him “the man, the anthropologist [he] wished for in the United States” and with whom “American anthropology enters into a new phase.” Boas, though he had not found a home in Europe, did retain some European chauvinism. He enjoyed outshining American anthropologists, who lacked his Old World education. “Actually,” he conceded, “it is very easy to be one of the first among anthropologists over here.”7

For all its originality, Boas’s 1894 address contained a number of dated ideas. One of them was the validity of comparing numbers of “great men,” in the fashion of Sir Francis Galton in England and Henry Cabot Lodge’s “Distribution of Ability in the United States.” And Boas remained tentative, closing with: “Although, as I have tried to show, the distribution of faculty among the races of man is far from being known, we can say this much: the average faculty of the white race is found to the same degree in a large proportion of individuals of all other races, and [even though] it is probable that some of these races may not produce as large a proportion of great men as our own race.” Counting up great men might be forgiven in Boas, even inferring failure in other races and cultures. After all, such was the tenor of impeccable scholarship at the time. Everyone else was doing it, but he was moving on. Boas soon jettisoned notions of comparative intelligence, as well as designations of “higher” and “lower” races.8

In 1906 he made another brave gesture toward racial tolerance by accepting an invitation from the pioneering African American social scientist W. E. B. Du Bois (1868–1963) to deliver a commencement address at Atlanta University. Not only was Boas a white scholar willing to go to a black institution; he came with a message of encouragement for young people about to enter a hostile America. Quite amazingly for 1906, he assured them they had nothing to be ashamed of. Other races—the ancestors of imperial Romans and the northern European barbarians—had endured their own dark ages. Now, if educated young black people could understand the “capabilities of [their] own race,” they could attack “the feeling of contempt of [their] race at its very roots,” and thereby “work out its own salvation.”9

In these Atlanta remarks, Boas draws intriguing parallels. For instance, he likens the differences between European Jews and Gentiles to imagined racial differences between European nobles and peasants. At this time French authors like Gobineau and Lapouge, along with many other European writers, considered France’s nobility Teutonic and the common people Celts, a supposedly different and inferior race. Not so, Boas declared. European nobles were “of the same descent as the people.” So were European Jews, “a people slightly distinct in type” from the Gentiles they live among.10 By “European” Jews, Boas doubtless had Germans in mind. In other commentary he did distance himself from Jewish immigrants newly arrived from Poland and Russia, people he termed “east European Hebrews.”

Thinking of himself as German American, Franz Boas neither hid nor proclaimed his Jewishness, and why should he have? For him, Judaism was a religion. His family, he said, had “broken through the shackles of dogma.” He had, therefore, been freed from the restraints “that tradition has laid upon us,” and could strive toward an ethical rather than a religious life.11 There could be no such thing as a Jewish race, because, for Boas, race resided in the physical body, something to be measured and weighed. He placed no faith in the notions of racial temperament so dear to Ripley and his English authority John Beddoe. Boas assumed that Jewishness might eventually disappear into American society through assimilation; he and most other German Jews in the United States lived by that belief. The new Jews from Russia and Poland, however, he judged differently. Their appearance in the early twentieth century caused him some consternation.

Unable to cast out every prejudice of the time, Boas dealt with the issue of immigrant strangeness in two ways, one inclusive, the other exclusive. Obviously, American society had over many decades worked its magic, as American-born generations assimilated physically and culturally. But could it Americanize these new immigrants, “Italians, the various Slavic people of Austria, Russia, and the Balkan Peninsula, Hungarians, Roumanians, east European Hebrews, not to mention the numerous other nationalities,” and bring them closer to “the physical type of northwestern Europe”? For Boas, “these people,” so distinct in many ways, were a worrisome “influx of types distinct from our own.”12

Here we have a contradiction. Boas did not support immigration restriction. Too much racism there. And yet his use of the language of “we” points straight to an “us” and “them” ideology. Not even this most liberal thinker could escape divisions of self and other inherent in racial ideology. The early 1900s were a particularly tough time to think about racial equality, and, as a result, such tension echoes across Boas’s work.

“HUMAN FACULTY as Determined by Race” might strike a twenty-first-century reader as timid, even retrograde. And “your own people” addressed to a black audience in Atlanta might ring uncomfortably close to the odious “you people.” But it was dramatic to hear Boas speak warmly across the black/white color line in an era of naked racial antagonism. During the late nineteenth century, poor, dark-skinned people often fell victim to bloodthirsty attack, with lynching only the worst of it. Against a backdrop of rampant white supremacy, shrill Anglo-Saxonism, and flagrant abuse of non-Anglo-Saxon workers, Boas appears amazingly brave.

It mattered little in those times that lynching remained outside the law. More than twelve hundred men and women of all races were lynched in the 1890s while authorities looked the other way. Within the law, state and local statutes mandating racial segregation actually expelled people of color from the public realm. On a national level, the U.S. Supreme Court decided Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896, validating Louisiana’s railroad segregation statute and opening the way to the segregation of virtually all aspects of southern life. Such laws and decisions, allied with local practice, disenfranchised hundreds of thousands, tightening a southern grip on federal power that racialized all of national politics.

Federal policy toward Native American Indians and people from Asia also signaled their vulnerability to white cupidity. In 1882 the Chinese Exclusion Act, passed after loud demands from organized labor, barred any sizable immigration of Chinese workers. Samuel Gompers, head of the American Federation of Labor and himself a Jewish immigrant from England, clamored for Asian exclusion when the legislation first passed and when it was up for renewal ten years later. Gompers even pressed for exclusion of Chinese from settling in American Pacific island possessions and from working on the Panama Canal.13 Before and after initial passage of Chinese exclusion, Indians and Asians in the West fell victim to whites lusting after their land and their jobs, as locals harried, attacked, and expulsed their Chinese neighbors. In 1887 the Dawes Severalty Act halved the land that Indians controlled by dividing up tribal territory among individuals and opening the so-called surplus Indian lands to white settlement. Southern states, beginning with Mississippi and South Carolina, revised their constitutions in the 1890s, encouraging the enactment of poll taxes, literacy and property qualifications, and grandfather clauses that ended black political life in the South.

Economic hard times further aggravated labor tensions. In the 1870s Slavic and Italian coal miners in western Pennsylvania suffered abuse, ostracism, cheating, incarceration, and attack. The U.S. Army massacred Lakota (Sioux) at Wounded Knee, South Dakota, in 1890, as lynching, that scourge of black Americans, took the lives of eleven Italians in New Orleans in 1891. Elsewhere labor conflict brought out company private militia (such as the Pinkertons) and state and national guards to coerce striking workers, as in the Homestead, Pennsylvania, steelworks in 1892.14 Doing the bidding of employers, local police and sheriffs and injunctions mandated by the Sherman Anti-Trust Act of 1890 broke labor unions, forcing striking workers back to work. Ugliness of spirit reached well beyond workers into the upper strata of American society.

A notable instance of anti-Semitism occurred in 1877 when a Saratoga Springs hotel refused to admit the New York financier Joseph Seligman, whose bank had helped finance the Union during the Civil War. Organized outbreaks of anti-Jewish violence occurred for the first time during the depression of the 1890s. In Louisiana and Mississippi, night riders attacked Jewish families and businesses. Personal abuse like stone throwing, hitherto occasional, became common throughout the North. When their employer hired fourteen Russian Jews, five hundred New Jersey workers rioted for three days in 1891, forcing Jewish workers and residents to flee. Educated Americans like the Boston Brahmin Henry Adams had long harbored anti-Semitic feelings. Now they felt free to voice stereotypical notions of Jewish control of the nation.

As mobs rampaged and learned opinion asserted the absolute superiority of Anglo-Saxon Americans, imperialist expansion put theory into practice. The Anglo-Saxon identity of “manifest destiny” had been obvious since 1845, when the journalist John O’Sullivan (despite his Celtic name) coined the phrase savoring the image of “the Anglo-Saxon foot” on Mexico’s borders and “the irresistible army of Anglo-Saxon emigration” pouring down upon the entire western portion of North America. Surely, the Anglo-Saxon would take over the Caribbean and Asia. Not least, the Spanish-American-Cuban War of 1898, a fairly transparent grab for empire, promised new frontiers for the American ruling class. The now virtually deified Theodore Roosevelt certainly had his say. Of Dutch ancestry, he preferred to speak of “the American race,” or “our race,” sometimes echoing Thomas Carlyle and Ralph Waldo Emerson.15

Racism permeated scholarship. Within Boas’s own field, the older leaders quickly rejected his racial relativism. Daniel Brinton, a prominent evolutionist, used his 1895 presidential address to the American Association for the Advancement of Science to reject Boas’s 1894 theory. For Brinton, the “black, the brown and red races differ anatomically so much from the white…that even with equal cerebral capacity, they could never rival the results by equal efforts.”16 Assertions of Anglo-Saxon superiority continued pouring out, as from Boas’s Columbia colleague John W. Burgess. Writing in the Political Science Quarterly in 1895, Burgess denounced the ignorance and wickedness of those supporting open immigration to the United States. They sought, he maintained in newly fashionable racial terminology, “to pollute [the United States] with non-Aryan elements.”17 This kind of meanness far out-shouted Boas’s careful edging away from racial chauvinism.

WILLIAM Z. RIPLEY’S The Races of Europe appeared in 1899, the same year his Columbia colleague Franz Boas received a professorship. In a singular turn of events, Boas reviewed the book for Science, the respected journal of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. Boas’s criticism departs sharply from the prevailing chorus of acclaim in three important aspects. First, Boas questioned Ripley’s conceptualization of ideal racial types. To Boas, that made no sense. Furthermore, he doubted that three (or more) races existed in Europe, and, last, he harbored serious reservations on the robustness of the cephalic index as a test of race.18

Such skepticism undermined the truth value of Ripley’s book and pointed toward where Boas would take anthropology in the new century. At the same time, though, here was a matter of interpretation, for in 1899 Boas was himself still measuring heads. (Two of his best-known students, the anthropologist Margaret Mead and folklorist-novelist Zora Neale Hurston, came along later to assist in this research.) While at Clark University, Boas had begun a Virchow-style study of the cephalic indexes of schoolchildren. In this he was merely carrying on the work of his mentor in Germany, who had measured tens of thousands of schoolchildren and categorized them according to their pigmentation and cephalic index in the 1870s. By the mid-1890s, however, Virchow had grown skeptical. Such measurements, even by the thousands, had not yielded much of anything beyond the fact that language, culture, and physical body did not neatly coincide. Virchow concluded that “Indo-Europeans,” another contemporary term for northern Europeans, exhibited no uniform physical type.19 Boas, for his part, was not yet ready to go that far. Perhaps more research on the concepts of racial type and cephalic index would shed light on the pressing new immigrant question.

THAT RESEARCH turned him to data compiled by Maurice Fishberg, a medical doctor practicing in New York’s heavily Jewish Lower East Side. Fishberg had measured forty-nine Jewish families over the course of two generations, producing intriguing results, but in a sample too small to support convincing conclusions.* To enlarge the sample size would require new funding, so Fishberg suggested that Boas approach the U.S. Immigration Commission, created by Congress in 1907. In the late eighteenth century, St. Jean de Crèvecoeur and Samuel Stanhope Smith had posited the creation of a new and particularly American physical type, and Ralph Waldo Emerson had voiced doubts along that line decades later. Taking up this idea, Boas proposed to study the effect of “change of environment upon the physical characteristics of man.” He specifically wished to discover whether immigrants from southern and eastern Europe could adjust to their American environment.

The Immigration Commission funded Boas’s application—such questions were in the air—and through 1908–09 he directed the measurement of some eighteen thousand eastern European and Russian Jews, Bohemians, Neapolitans, Sicilians, Poles, Hungarians, and Scots.20 The tens of thousands of northern Europeans, mostly Irish and Germans, still immigrating to the United States caused no alarm and therefore hardly figured in this research. Here was another token of the second enlargement of American whiteness.

The Immigration Commission of 1907 was also known as the Dillingham Commission, its chair being Senator William P. Dillingham, Republican from Vermont. Shortly after being formed, it took a big step toward immigration restriction. President Grover Cleveland, a Democrat, had frustrated restrictionists in 1897 by vetoing a bill (supported by the American Federation of Labor) limiting entry to immigrants who passed a literacy test. Southern states had begun to use literacy tests as a means of curbing black and poor white voting, and the Dillingham Commission took up the restrictionist cause with a vengeance. By the time it closed down in 1910, it had sponsored eighteen immigrant reports in forty-one volumes, most of them encouraging restriction. But one dealt with Boas’s measurements of immigrants and their children.

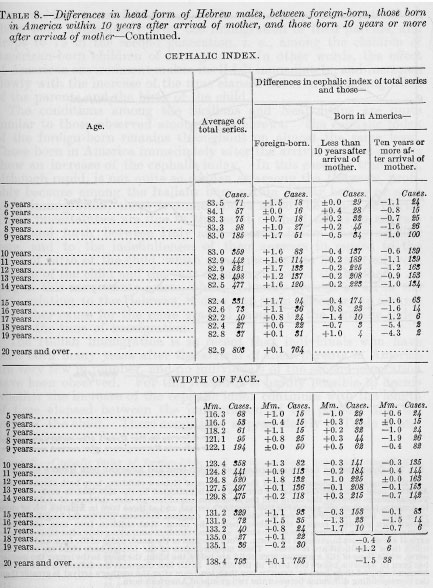

Nearly 600 pages long, Boas’s Changes in Bodily Form of Descendants of Immigrants consists largely of graphs, illustrations, and tables, the very scientific apparatus Ripley and others had employed to convey methodological soundness. Details of stature and weight figured, but were minor compared with the cephalic index, the king of race measurements. Among Boas’s several immigrant populations, some heads attracted more attention than others, and his most famous conclusions concerned the scariest immigrants: southern Italians (“Sicilians and Neapolitans”) and Russian/Polish Jews (“east European Hebrews”).

Boas presents his findings in conventional tabular form. (See figure 16.2, Boas’s “Table 8.”) Table 8, for instance, indicates differences in the head shapes of Jewish youngsters of three types: those born outside the United States, those born less than ten years after the immigrant mother’s arrival in the country, and those born subsequently. The bombshell lay in the columns on the right. They show that the longer the mother had lived in the United States, the more her American-born son’s head shape differed from that of her sons born abroad.21 These findings were nothing short of revolutionary.

Boas found that head shape, supposed never to change, was indeed changing. The round-headed “east European Hebrew” was becoming more long-headed, while “the south Italian, who in Italy has an exceedingly long head” was becoming more short-headed. All in all, it appeared “that in this country both approach a uniform type, as far as the roundness of the head is concerned.” Having found what he perhaps was looking for, Boas read enormous significance into these changes, even though they were modest. He concluded that “when these features of the body change, the whole bodily and mental make-up of the immigrants may change.” Thus, Alpines, Mediterraneans, and Jews would join Anglo-Saxons as real Americans in body and therefore in mind and spirit. For “the adaptability of the immigrant seems to be very much greater than we had a right to suppose before our investigations were instituted.” At bottom Boas’s study denied the need for hysteria over the new immigrants.*

Fig. 16.2. Franz Boas, “Table 8. Differences in head form of Hebrew males, between foreign-born, those born in America within 10 years after arrival of mother, and those born 10 years or more after arrival of mother —Continued,” in Reports of the United States Immigration Commission (New York: Columbia University Press, 1912).

The Dillingham Commission, not surprisingly, came to the opposite conclusion, one favoring the idea of permanent type. While duly noting the scholarly import of Boas’s work, just one report in a thickening fray, the commission declined to incorporate his findings in its report; deeming them incomplete, it vaguely recommended further study.22 In the long run, however, Boas won. Social scientists and the educated lay public took note of his study, increasing his stature internationally.23 The possibility that races from southern and eastern Europe might change physically began to circulate in enlightened discussions of immigration and American identity. Ultimately, Boas’s research on immigrants’ heads cast the cephalic index into anthropology’s waste bin and tipped the heredity versus environment balance toward environment, at least for a while. That tipping took a long time.

In the short run, U.S. immigration policy hardly changed. Rather, the restrictionist campaign petered out in the face of opposition in the form of the power generated by immigrant organizations and their allies. Immigrant neighborhoods created a panoply of institutions, starting with stores and saloons and extending into newspapers and political organizations. Their names reveal their provenance—the Pennsylvania Slovak Catholic Union, the Ukrainian Workingmen’s Association, the Polish Women’s Alliance, the Sons of Italy, the Serbian National Federation, the Chicagoer Arbeiter Zeitung, and the Irish World newspaper—and their numbers were legion; fraternal organizations, mutual-aid societies, burial societies, nationalist clubs, saloons and taverns, and foreign-language newspapers kept immigrants in touch with their homelands and supplied the news that mattered in native languages.24 A popular Italian language newspaper, Il Progresso Italo-Americano, a New York daily founded in 1880, reached more than 100,000 readers, and the Yiddish Jewish Daily Forward, founded in 1897, had a circulation of 175,000. Political clubs delivered the votes that elected the representatives who served the needs of immigrant constituencies.

Postponement of immigration restriction from the 1880s to the 1920s, for example, testifies to the clout of congressional representatives of immigrant communities, particularly in New York. The first Italian American U.S. representative was elected in 1890, after serving in the California State Assembly from 1882 to 1890. While a token number of Jews had entered in the U.S. House of Representatives during the nineteenth century, their numbers increased impressively after 1900. More than twenty Jewish representatives served in Congress before the First World War, the great majority as Democrats from New York.25

In addition, an articulate liberal-minded cohort of freethinkers, social workers, and settlement house workers had firsthand knowledge of the poor European immigrants who were being racialized and denigrated. Living out the promise of progressivism, liberals were gaining influence in the public sphere. Immigrants, their children, their institutions, and their friends—and their employers—together created a climate more favorable to immigration, even toward working people and the poor.26 Shying from controversy and content to leave well enough alone, Presidents William Taft and Woodrow Wilson each vetoed bills containing literacy tests.

American political culture was moving into the Progressive Era, and Boas’s own circle reflected the change. Boas had long prided himself on his family’s “Forty-eighter”* liberalism, and his wife came from a free-thinking Austrian Catholic family. A friend, Felix Adler, had founded the Society for Ethical Culture, and Boas’s Forty-eighter uncle Abraham Jacobi and his friend Carl Schurz championed reform, especially addressing the needs of poor children. Boas’s friends also included feminist progressives like Frances Kellor, Victoria Earle Matthews, and Mary White Ovington. His students, such as Melville Herskovits, Otto Klineberg, Ruth Benedict, Zora Neale Hurston, Margaret Mead, and Ashley Montagu, investigated non-Anglo-Saxons and stressed the crucial role of environment in human culture.27

It mattered that so many of the settlement house workers and moral reformers advocating public health and social services for the poor were educated women—the very women Theodore Roosevelt hectored over their duty to breed. Turning away from the nineteenth-century pattern of charity intended to correct personal weaknesses, they recognized the structural causes of poverty. Localities, states, and even the federal government, they said, owed the population certain services as rights, because environment, not inherent weakness, made people poor. When the environment changed for the better, then people would improve.

POPULAR CULTURE played a leading role in this high point of progressivism. While the Immigration Commission gathered data and Boas measured heads, the American theater rode a wave of fascination with settlement houses and immigrants. A play called The Melting Pot opened in Washington, D.C., in October 1908 to Theodore Roosevelt’s praise, and moved on to long runs in Chicago and New York. Its author, the English Jewish immigrant Israel Zangwill, celebrates the creation of Americans out of immigrants in a melodramatic version of Boas’s graphs and tables of immigrant assimilation.†

The plot of The Melting Pot revolves around two characters who, unbeknownst to each other, have emigrated from the same Russian village of Kishinev (in modern Moldova, between Romania and Ukraine). Vera Ravendal, an aristocratic, revolutionary Christian, now works in a New York settlement house; David Quixano, a Jewish musician and composer, has witnessed the slaughter of his parents in the most infamous of the Russian pogroms, the trauma that drove him to the United States. The supporting cast includes David’s Orthodox uncle and aunt, a German symphony conductor, the Quixano family’s Irish domestic servant, and a nouveau riche American playboy. Although Zangwill places the Quixanos among the despised Ashkenazi “east European Hebrew” masses of early twentieth-century immigrants, he gives them a Sephardic name evoking a more prestigious Iberian history. Benjamin Disraeli, the late British prime minister, had given his characters Sephardic ancestry in novels written before his prime ministership in 1868.28*

When Vera and David fall in love in The Melting Pot, they find that old country rages are still boiling. Vera’s father, it turns out, had led the pogrom that killed David’s parents, and David’s uncle Mendel cannot forgive either the assailant or the descendant of a murderer. In America, however, Vera is free to understand David’s feelings better than his uncle, and the New World allows the young people to transcend their pasts. Vera and David agree to marry without sacrificing either of their religions.

The play ends on the Fourth of July with a rousing performance of David’s “American Symphony.” As David and Vera watch the sun set behind the Statue of Liberty, they celebrate the American melting pot:

DAVID [Prophetically exalted by the spectacle]

It is the fires of God round His Crucible.

[He drops her hand and points downward.]

There she lies, the great Melting Pot—listen! Can’t you hear the roaring and the bubbling? There gapes her mouth

[He points east]

—the harbour where a thousand mammoth feeders come from the ends of the world to pour in their human freight. Ah, what a stirring and a seething! Celt and Latin, Slav and Teuton, Greek and Syrian,—black and yellow—

VERA [Softly, nestling to him] Jew and Gentile—

DAVID Yes, East and West, and North and South, the palm and the pine, the pole and the equator, the crescent and the cross—how the great Alchemist melts and fuses them with his purging flame! Here shall they all unite to build the Republic of Man and the Kingdom of God.

Ah, Vera, what is the glory of Rome and Jerusalem where all nations and races come to worship and look back, compared with the glory of America, where all races and nations come to Labor and look forward! [He raises his hands in benediction over the shining city.] Peace, peace, to all ye unborn millions, fated to fill this giant continent—the God of our children give you Peace.

[An instant’s solemn pause. The sunset is swiftly fading, and the vast panorama is suffused with a more restful twilight, to which the many-gleaming lights of the town add the tender poetry of the night. Far back, like a lonely, guiding star, twinkles over the darkening water the torch of the Statue of Liberty. From below comes up the softened sound of voices and instruments joining in “My Country, ’tis of Thee.” The curtain falls slowly.]29

ALL IN all, questions of immigration and assimilation were a muddle between 1890 and 1914. The promise of assimilation exemplified by Boas and Zangwill encouraged Americans of a welcoming turn of mind. Conversely, Ripley’s idea of three separate European races, with lines deeply etched between them, held more power. Two emblematic figures, the patrician president Theodore Roosevelt and the scholar Edward A. Ross, enunciated the thinking of most educated early twentieth-century Americans who feared that immigrants would defile their America. This was thoroughly racist thinking, directed toward races that were white.