21

THE GREAT UNREST

The United States stayed out of the European charnel house of war until 1917, when the conflict was already three years old. But even as American troops went to fight in Europe, the United States experienced the war less as a tragedy of trench warfare and more as a time of spiraling labor unrest and anti-immigrant paranoia. Between 1917 and 1919, a growing cycle of strikes and labor tension alarmed Americans across the political spectrum. A cartoon from the Saturday Evening Post, the nation’s most popular magazine, captured the all too facile coupling of immigrants, and radicalism, and race. (See figure 21.1, Johnson, “Look Out for the Undertow!”) Here Herbert Johnson, the Post’s regular cartoonist, depicts an American family dashing into the waves of “immigration,” grinning innocently.1* The mother wears the “sentimentalist” label that hardheaded, science-minded race theorists routinely attributed to anyone—especially women—who believed that the environment played a role in human destiny. The smiling father, equally clueless, leads his family into the wave as “employer of cheap labor.” Only the child, the “future of America,” hangs back, sensing the peril ahead. Rolling in with the “immigration” wave are fatal threats to the nation—“lowered standards,” “race degeneration,” “bolshevism,” and “disease.” In this cartoon, the race in question was white, as was the menace.

Fig. 21.1. Herbert Johnson, “Look Out for the Undertow!” Saturday Evening Post, 1921.

Republicans in Congress had been trying to restrict immigration on more or less racial grounds since the 1880s, but with limited success. Their party was, in fact, divided. Although normally allied with the Republicans, manufacturers employing cheap immigrant labor lobbied diligently against legislation to curtail it. Their economic interests weighed against a tightening of the labor market and the certainty of rising wages. The result was an unexpected alliance. Democratic presidents and congressmen representing large numbers of immigrants also resisted anti-immigration legislation as racist and discriminatory. So long as immigrants could vote—before or after naturalization—their representatives, usually Democrats, blocked much restrictive legislation.

At the center of these legislative storms were not the Irish or the Germans—they had mostly been accepted and assimilated (during the war, Germans sometimes through anxiety or intimidation). Rather, the main targets hailed from southern and eastern Europe, the masses of Slavs, Italians, and Jews, many said to be mentally handicapped, prone to disease and un-American ideologies. Therein lay the threat. Where in all this were Asians? Nowhere, for since 1882, after Chinese workers had completed the western portion of the transcontinental railroad, they had, one and all, been declared ineligible for citizenship. Not being part of the new American political economy meant that Asians lacked any influence in Congress. It took them a long time to gain parity.* A fundamental issue was labor: the stigmatized immigrants came as workers to feed American industry.

During the late nineteenth century, the United States had industrialized impressively. After recovery from the deep depression of the 1890s, American industrial output rivaled Europe’s. More than 14.5 million immigrants, mostly from southern and eastern Europe, entered the country between 1900 and 1920, their numbers far exceeding even the lowly Irish and Germans disdained by Ralph Waldo Emerson as “guano races.”2 In Emerson’s time the Irish had found paying work on the canals and the eastern railroads; now immigrants poured into manufacturing, rather than farming and transportation, generating the profits of twentieth-century America.3

By the 1890s industrialization had given rise to giant corporations like Standard Oil of John D. Rockefeller, U.S. Steel under Andrew Carnegie, and the combined Union Pacific, Southern Pacific, and Illinois Central railroads run by E. H. Harriman. The wealth of these corporations depended upon friendly state and federal legislators and a multitude of local corporation lawyers in the state legislatures that elected U.S. senators until 1913. Corporate-minded officeholders shaped a legal context friendly to corporations and hostile toward labor. Free to squelch workers’ attempts to organize and quick to exert the power of the state against strikers, corporations rewarded themselves with salaries, bonuses, and profits and their shareholders with dividends, rather than accord their workers wage increases. Inevitably, workers came to resent such exploitation. In the popular mind, their resentment wore an immigrant face.

Soon disruptive actions, such as the great steel strike in Homestead, Pennsylvania, in 1892 and the 1894 Pullman strike near Chicago, broke out regularly. Even voters who may have felt no particular warmth toward labor began to cast protest votes against the two major parties, both very dedicated to serving capital. In consequence, during the so-called Progressive Era before 1915, left-wing policies more attuned to the needs of people than to the wishes of powerful corporations gained favor.

The Socialist Party (SP), founded in 1901, led the way, powered by voters unhappy with the lockstep Republican and Democratic probusiness status quo. Throughout the country the SP grew quickly from around 1910, attracting some 100,000 members. One stronghold, New York City’s 1.4 million Yiddish-speaking, working-class immigrants, elected a series of socialist candidates, including ten state assemblymen, seven city councilmen, one municipal judge, and one congressman.4 The SP candidate for president, Eugene Debs, polled a million votes in 1912, the SP’s high-water mark.

The far more revolutionary labor organization, the Industrial Workers of the World, also seized the moment, waging a media-savvy textile strike in Lawrence, Massachusetts, birthplace of American industry in the heart of symbol-laden New England. The IWW had broken away from the SP in 1905 to pursue more radical, worker-centered policies. For many anxious Americans, the SP and IWW merged into a huge revolutionary threat to American society, one identified with immigrant “alien races.” In the tense, hyper-patriotic atmosphere of wartime, any hint of labor militancy did not play well across the country.

ONCE THE United States became a belligerent in April 1917, war production shot up, and the labor was in many cases supplied by immigrants. Long working hours and soaring inflation ensued. Everyone complained about the high cost of living, for wages did not keep pace with spectacular price increases. The result was a tsunami wave of strikes, peaking in 1917. The IWW, though small in number, staged highly publicized actions in the West, home to large numbers of Mexican immigrants. Although native-born lumberjacks and mineworkers vastly outnumbered Mexicans in the IWW, true to the hysteria of the moment, many Americans assumed the whole organization to be aliens. It was but a short step to draconian legislation. The Immigration Act passed in February 1917 targeted the IWW specifically and labor radicalism generally, barring entry into the United States of all “anarchists, or persons who believe in or advocate the overthrow by force or violence of the Government of the United States.”5 Vigilantes quickly took the law into their own hands; they lynched a Wobbly organizer in Butte, Montana, and in the fall federal agents raided IWW headquarters in forty-eight cities. Such federal action kept the IWW in court and on the defensive, even as strikes for more pay continued around the nation.

Meanwhile, in February and October 1917 Russia experienced a first and then a second revolution in the name of the working class. The second one, proclaiming itself Marxist, Bolshevik, and Soviet, took Russia out of the European slaughterhouse of war. Furthermore, it increased the attraction of socialism as an alternative to senseless, belligerent politics and bolstered the appeal of Marxism as a sweeping explanation for the human condition.

At bottom, Marxism touted class conflict, rather than race conflict, as the motor of history. Such a substitution of class for race did not alter Americans’ social ideology, for foundational law and the organization of government data (such as the census) still relied on categories of race. The Russian revolution did not persuade Americans to think about labor and politics in terms of class; they continued to interpret all sorts of human difference as race.

Therein lay a crisis of race ideology. If the Teutonic white peoples of Europe represented humanity’s apex, how had they reverted to savagery so easily? The African American sociologist W. E. B. Du Bois had an answer: “This is not Europe gone mad; this is not aberration nor insanity; this is Europe; this seeming Terrible is the real soul of white culture…stripped and visible today.”6 In the face of the first great crisis of whiteness, saving the “real soul of white culture” became Americans’ task after the war, one imposed and accepted amid a clash of ideas and events. The Russian revolution and wave after wave of strikes converged on hereditarian concepts of permanent racial traits à la Ripley’s Races of Europe. The idea of the “melting pot” was already under stress when wartime anxieties tested it further.

By the armistice of November 1918, “bolshevism” in the American public mind meant the world turned upside down. In Germany a socialist revolution followed the abdication of Emperor Wilhelm II, evidently spreading the red tide. Many in the United States felt themselves stuck in a bad dream, in which Bolshevik Wobblies were running things, foreign strikers were fomenting chaos, and an insurrectionary proletariat threatened to seize government, murder citizens, burn churches, and in general destroy civilization. The end of civilization meant ugly, ignorant, unwashed immigrants breeding freely—their defects innate, hereditary, and permanent—and native Americans trodden underfoot. Events of 1919 simply made things worse.

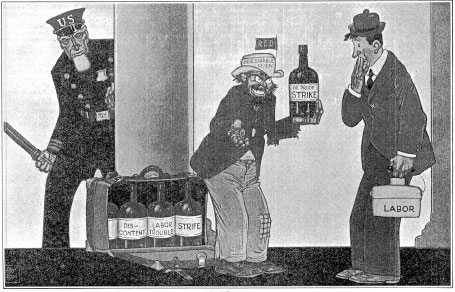

The whole world seemed in convulsion. Strikes and revolutions raged on every continent, in France and even in England. In the United States, 1919 began with a general strike of 100,000 workers in Seattle, an event that seemed so unthinkably un-American that it had to have foreign causes. Another Saturday Evening Post cartoon explains where strikes come from and offers a solution to the labor crisis.7 (See figure 21.2, Roun, “100% Impure.”) A grubby, dark-skinned “undesirable alien” with a red flag in his hat for socialism, offers a potent, tempting drug, “100% proof strike” to befuddled “labor.” According to race theory’s prevailing wisdom, labor’s head shape tells a tale. It is flat in the back, thus marking him as a brachycephalic Alpine, hence bovine of intelligence and easily misled by “undesirable alien.” The valise of “undesirable alien” contains four other bottles of poison, three labeled “discontent,” “labor trouble,” and “strife.” Arriving in the nick of time to save poor, dumbfounded “labor” is a policeman labeled “US.” The solution to the labor problem caused by “undesirable alien” must therefore come from stringent federal governance.

Fig. 21.2. Ray Roun, “100% Impure,” Saturday Evening Post, 1921.

Seattle’s general strike lasted only a week, but it was long enough to offer conservatives time to trumpet Bolshevik infiltration right here at home, which mounting strikes seemed to prove: 175 in March, 248 in April, 388 in May, 303 in June, 360 in July, and 373 in August. More strikes had taken place in 1917, but more workers had gone out in 1919’s climate of hysteria. This was also the summer of bloody attacks on African Americans who had come up from the South to jobs in northern industry. Antiblack pogroms made 1919 the Red Summer: red for bloodshed as well as labor conflict.8

Strikes rolled into the fall: some in places where famous strikes had occurred before and some where striking seemed unthinkable. In September 350,000 steelworkers struck U.S. Steel factories in six states, climaxing a decades-long campaign for an eight-hour-day and recognition of the steelworkers’ union. In November 600,000 railroad workers in twenty states walked off the job, and wildcat strikes paralyzed transportation locally. Nearly half a million coal miners threatened to strike in November, when coal heated American homes and schools.

Even the police played a part. In Boston 1,200 police struck for higher wages and union recognition, throwing the city into chaos. Calvin Coolidge, governor of Massachusetts, announced that the police had no right to strike, called in the state national guard, and emerged an instant hero. Commentators likened striking Boston police to Bolsheviks. Coolidge became the Republican vice presidential candidate in the fall of 1920 and president after President Warren G. Harding’s death in 1923.

Popular hysteria bred confused thought. Most strikes had centered on wages or conditions on the shop floor, but now labor militancy merged with socialism and anarchism, notions deemed foreign and un-American. A poem published in a steel industry magazine linked politics to nativity:

Said Dan McGann to a foreign man who worked at the self-same bench.

“Let me tell you this,” and for emphasis, he flourished a monkey wrench,

“Don’t talk to me of this bourgoissee, don’t open your mouth to speak

“Of your socialists or your anarchists, don’t mention the bolshevik,

“For I’ve had enough of this foreign stuff, I’m sick as a man can be

“Of the speech of hate, and I’m telling you straight, that this is the land for me.”9*

Anarchists had presented a popular target since the late nineteenth century, and in the present unrest a murder in Massachusetts offered opportunity to clobber anarchism in the persons of Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, Italian laborers associated with Luigi Galleani, publisher of the revolutionary Cronaca Sovversiva (Subversive Chronicle). Sacco and Vanzetti, convicted of murdering two security guards in the course of a robbery in Braintree, became a cause célèbre on account of the questionable conduct of their trials, which ended with the hanging of both men in 1927, after enormous controversy.†

INVESTIGATIONS PROLIFERATED. The Saturday Evening Post, which reached some ten million Americans, ran a series of “fire alarm” articles warning of the intertwined immigrant-bolshevik menace.10 The U.S. Senate took up investigations of domestic bolshevism, hearing testimony that Jews had caused the Russian revolution. With the Post’s amplification, claims that Jews caused strikes and revolutions, bolshevism, socialism, syndicalism, strikes, and the melting pot ricocheted through a jumpy society.

Bombs and bomb scares joined strikes as sowers of disorder. Bombs were sent to prominent men in the federal government and to post offices countrywide, aimed especially at proponents of immigration restriction. Although the identity of the bombers was not known, foreign radicals and labor organizers got the blame. American Legionnaires broke into IWW halls and beat up whomever they found, and the U.S. Justice Department began raiding socialist meeting halls far and wide in the fall. Dragnets in November yielded 249 deportable (i.e., noncitizen) radicals and took them on a “Red Special” to Ellis Island for deportation. The deportees included the famous anarchist Emma Goldman. No socialist, and certainly not Russian, Goldman was nevertheless shipped to Russia as a bolshevik.*

The specter of a bolshevism hagriding Americans made suspect any departure from conventional thought, political or cultural. Before and during the war “Americanization” projects had attempted to teach immigrants English and turn them into Americans. But wartime fears of espionage and sedition intensified this campaign into a press for “One-hundred percent Americanism.” One hundred percent Americanism meant not simply unstinting support for the war and the closing of radical newspapers such as Il Proletario, with its sharp criticism of American public life, but also a renunciation of old-country ways of living and speaking. Cities and employers coerced employees into Americanization courses, where the English language, civics, and an upstanding way of life were strictly encouraged. The National Americanization Committee, led by the New York labor reformer Frances Kellor, was nominally a federal organization but functioned according to Kellor’s vision. The committee defined its work as “the interpretation of American ideals, traditions, and standards and institutions to foreign-born peoples,” “the combating of anti-American propaganda activities and schemes and the stamping out of sedition and disloyalty wherever found,” “the elimination of causes of disorder, unrest, and disloyalty which make fruitful soil for un-American propagandists and disloyal agitators,” and “the creation of an understanding of and love for America and the desire of immigrants to remain in America, and have a home here, and support American institutions and laws.” These often intense classes met several times per week and were closely monitored by the authorities.11

Before the war Henry Ford had set up one of the longest-lived one hundred percent Americanism systems in his Michigan automobile plants. Ford’s Sociological Department, a model of Americanization, taught autoworkers “how to live a clean and wholesome life,” according to Ford’s own idea of “living aright.” Speaking English, passing regular home inspections, remaining sober, keeping a savings account, and sticking to “good habits” were mandatory, while riotous living and roomers were strictly forbidden.

The Ford school was intended to Anglo-Saxonize an immigrant workforce, as symbolized at graduation. At center stage stood a huge, papier-mâché melting pot with stairs on both sides. As the band struck up a rousing tune, graduates in their national clothing went up the stairs on one side, entered the melting pot, and came out on the other side singing “The Star-Spangled Banner” and waving American flags. They were now dressed in derby hats, pants, vests, jackets, stiff white collars, polka-dot ties, and a Ford Motor Company badge in each lapel.12 For women, Americanization meant conforming to social workers’ notions of proper housekeeping, cooking, dressing, and child rearing. In sum, Americanization imposed the use of English and patriotic conformity. Socialistic notions were nowhere to be found here or, indeed, anywhere in the American power structure.