26

THE THIRD ENLARGEMENT OF AMERICAN WHITENESS

The Second World War rearranged Americans by the millions. Some 12 percent among a population of 131.7 million—roughly 16 million people—served in the armed forces, which threw together people whose parents hailed from all over Europe.1 Millions of civilians migrated to jobs around the country, further diluting parochial habits. Some 2.5 million southerners left the South, and northerners went south to training camps and war work.2 Louis Adamic had dreamed of a second, more homogenized immigrant generation, and one had already started in the Civilian Conservation Corps, fruit of the New Deal’s earliest days. Now, a decade later, millions rather than tens of thousands left home.

Let us remember that this mixing occurred with several notable exceptions. Black Americans—who numbered some 13.3 million in 1940—were, of course, largely excluded. Their time would come much later, and with revolutionary urgency. But also excluded were Asian Americans. Even so, other Americans—provided they qualified as white for federal purposes—experienced a revolution of their own. Indeed, the white category itself had expanded enormously, well beyond European immigrants and their children. Included now were Mexicans and Mexican Americans.

The handsome Julio Martinez from San Antonio plays a leading role in the multicultural Army squad of Normal Mailer’s best-selling war novel The Naked and the Dead (1948). No bit player, Martinez, like Red Valsen, the Swede from Montana, and Sam Croft, the Anglo-Saxon hunter from Texas, rates a chapter of his own.3 Since the mid-1930s, federal and Texas state laws had defined Mexicans as white and allowed them to vote in Texas’s white primary.4 While Asian American and African American service personnel were routinely segregated and mistreated, Mexican Americans fought in white units and appeared in the media of the war, witness the boom in popular war movies like Bataan (1944), starring the Cuban Desi Arnaz (who in the 1950s would become a television star as Lucille Ball’s husband in the long-running I Love Lucy series).

Meeting new people in new places broke down barriers. The novelist Joseph Heller (1923–99) left his Jewish corner of Brooklyn’s Coney Island and went south to the Norfolk Navy Yard in Portsmouth, Virginia. Heller was not surprised to find that local whites studiously ignored their black fellow workers in the navy yard. But the “uniform virulence with which Protestants regarded Catholics” amazed him. Luckily for Heller, such hostility was not his problem; as a Jewish New Yorker, he became a novelty, treated well and chatted up warmly in lunchtime breaks—with a single exception.

One discussion, he wrote in his memoir, “turned to religion and I chose to volunteer the information that Jesus was in fact Jewish and of presumed Jewish parentage. The immediate and united stiffening of the entire circle of white faces was an instantaneous warning that they had never been told this before and did not want to be told it now, or ever. Even my closest pals bristled.”5 Similar lessons in cultural difference occurred countless times.

It was federal policy that supplied lessons in diversity, and federal policy also defined its limits, by means of a rigidly enforced segregation that imprisoned 110,000 Japanese Americans and counted up fractions of Negro “blood” in order to separate black servicemen from white.6 By and large, only those being kept apart and their allies noticed the segregation for quite a long while.* The loudest notes of wartime stressed inclusion, and the song of brotherhood echoed over the years.

THIS THEME of inclusion had emerged during the New Deal of the 1930s as a means of strengthening the Democratic allegiance of new voters in immigrant neighborhoods. President Roosevelt addressed immigrants and their children in a spirit of oneness. The outbreak of war in Europe in 1939 intensified American condemnation of intolerance. One of the president’s “four freedoms” defining the goals of the war was freedom of religion.7† In 1940, the popular picture magazine Look showed how far religious prejudice had fallen out of favor by publishing a special issue denouncing anti-Semitism. When Charles Lindbergh in September 1941 blamed the war on the British, the Roosevelt administration, and the Jews, the normally cautious New York Times denounced his anti-Semitism.8‡ An example of official wartime Americanism appears in the seven propaganda movies the U.S. Army Signal Corps commissioned. Entitled Why We Fight and directed by Hollywood’s Frank Capra (1897–1991). These films sought to teach enlisted men the democratic basis of the war.

The Capra family’s story, one of Sicilian immigrants, presents a cogent example of two experiences, one older and one newer. As eventually a fabulously successful filmmaker, Frank Capra stands out from the crowd. His older brother, Ben, was not so lucky. Frank and the rest of his family immigrated to California in 1903 to join Ben, whose life had been more representative of Italian immigrants’ misadventures.

Ben Capra had contracted malaria while working in the sugarcane fields of Louisiana with other Italians and African Americans. A black woman had nursed him back to health, and he stayed with the black family for two years. Later, in New Orleans, Ben fell victim to the beating, kidnapping, and transport that ensnared many a vulnerable immigrant of the time. Shipped to a sugar island in the Pacific Ocean, he and a buddy escaped peonage in a rowboat and were miraculously rescued by an Australian liner and taken on to California. There Ben settled,* and there his younger brother Frank spent, as he reports, a miserable American childhood: “I hated being poor. Hated being a peasant. Hated being a scrounging newskid trapped in the sleazy Sicilian ghetto of Los Angeles. My family couldn’t read or write. I wanted out. A quick out.”9 The military offered a route of escape.

Frank Capra served in the U.S. Army in the First World War and was naturalized a U.S. citizen in 1920. His extraordinary film career began in the 1930s, culminating in iconic films such as It Happened One Night (1934), Mr. Deeds Goes to Town (1936), You Can’t Take It with You (1938), and Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939). In Mr. Deeds Goes to Town and Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, ordinary Americans defeat the nefarious forces of financial and political corruption, confirming the power of upstanding, small-town individuals. The good guys were always unquestionably Anglo-Saxon.† Even scenes set in cities and on farms show exclusively Anglo-Saxon crowds forming an all-American, Anglo-Saxon backdrop to the all-American, Anglo-Saxon protagonists played by, say, Gary Cooper or Jimmy Stewart.‡ Omnipresent Nordicism characterized Hollywood feature films throughout the period, even though most filmmakers—writers, directors, producers—came from immigrant backgrounds, both Jewish and Catholic.

Frank Capra’s screenwriters Robert Riskin and Sidney Buchman were eastern European Jews. Buchman, a communist, would be black-listed during the anticommunist 1950s. Not that the Left would have offered Capra, Riskin, and Buchman ready examples of ethnic multiculturalism, for the Communist Party took its cues from the movies. Prominent communists in the United States routinely exchanged their European ethnic names for anodyne English-sounding ones: the Finnish American Avro Halberg became Gus Hall; the Jewish American Solomon Israel Regenstreif became Johnny Gates; the Croatian Stjepan Mesaros became Steve Nelson; Dorothy Rosenblum became Dorothy Ray Healey. Even the CP’s worker iconography gave the American worker a Nordic face and a tall, muscular body.10

Popular literature also mirrored the movies, even as the war effort stressed diversity. A 1945 study by Columbia’s Bureau of Applied Social Research found that stories published between 1937 and 1943 in magazines reaching twenty million readers featured 889 characters, of whom 90.8 percent were Anglo-Saxon. The rare non-Anglo-Saxons were stereotyped as menial workers, gangsters, crooked fight promoters, and thieving nightclub owners, while Anglo-Saxons in central roles were honest and admirable, their superiority taken for granted.11 The advertising seeping into every corner of American popular culture beamed out smiling Nordics free, beautiful, and desirable.

With real American identity coded according to race, being a real American often meant joining antiblack racism and seeing oneself as white against the blacks. Looking back to the war years, an Italian American recalled a tempting invitation to take sides during the Harlem riot of 1943: “I remember standing on a corner, a guy would throw the door open and say, ‘Come on down.’ They were goin’ to Harlem to get in the riot. They’d say, ‘Let’s beat up some niggers.’ It was wonderful. It was new. The Italo-Americans stopped being Italo and started becoming Americans. We joined the group. Now we’re like you guys, right?”12 The temptation and the decision to succumb did not pass unnoticed. Malcolm X, spokesman of the black nationalist Nation of Islam, and Toni Morrison, a Nobel Prize laureate in literature, later noted that the first English word out of the mouths of European immigrants was frequently “nigger.” Actually, Morrison said it was the second, after “okay.”13

Much—too much—of 1940s American culture stayed stuck in the racist 1920s, although some code words fell out of fashion. The roots of “Nordic” in Madison Grant’s Nazi-like eugenics disabled it for use in the 1940s. Prewar names of the categories of dolichocephalic and brachycephalic also disappeared, though FBI “wanted” posters and mug shots continued to depict miscreants in profile as well as full-face. The shape of the head, it seems, still said a good deal. Nor did the cephalic index fade as in the American’s ideal face shape—the dolichocephalic, long-headed oval of Norman Rockwell’s quintessential Americans, rather than the brachycephalic square or round. Be tall, be blue-eyed, and, if a woman, be blond.

Autobiographical statements of Americans born in the 1940s reveal a keen awareness of the difference between American standards of beauty and the bodies of women increasingly being called “ethnic.” This term dated back to the 1920s, but it came into common discourse only after the Second World War as a way to label the children and grandchildren of Louis Adamic’s second immigrant generation. English, German, Scandinavian, and Irish Americans did not fall under the “ethnic” rubric, which had become a new marker for the former “alien races.” An Italian American recalled his mother, in the 1940s, “referring to the Irish families on the block as ‘the Americans.’”14 For quite some time, ethnic Americans looked from afar on the “blond people,” the term of the anthropologist Karen Brodkin for the “mythical, ‘normal’ America” of magazines and television. In quest of the tall, slender “normal” American silhouette, she wrote, “my mother and I were always dieting. Dieting was about my and my mother’s aspirations to blond-people standards of feminine beauty.”15

Much nose bobbing, hair straightening, and bleaching ensued. Anglo-Saxon ideals fell particularly hard on women and girls, for the strength and assertion of working-class women of the immigrant generations were out of place in middle-class femininity. Not only was the tall, slim Anglo-Saxon body preeminent, the body must look middle-rather than working-class.

And the middle class was growing in actual fact. Once again, Joseph Heller explains the economic transformation that began with military service: “My total income upon entering the air force as a private was as much as I’d been able to command outside, and as an officer on flight status was greater than I was able to earn afterward when starting out in my civilian pursuits.” After the war, the money just got better.16

Here is Heller again, on top of the world in 1945: “I felt myself walking around on easy street, in a state of fine rapture. What more could I ask for? I was in love and engaged to be married (to the same young woman I was in love with). I was twenty-two years old. I would be entering college as a freshman at the University of Southern California, with tuition and related costs paid for by the government.” And the guys from his neighborhood were doing all right, too:

After the war, Marty Kapp [a Heller neighbor] continued what technical education had begun in the navy V-12 program and graduated as a soil engineer (yet another thing I’d not heard of before). For all his career he worked as a soil engineer with the Port Authority of New York—on airfields and buildings, I know and perhaps on bridges and tunnels, too—and had risen to some kind of executive status before he died. He did well enough to die on a golf course…. I was able to go to college. Lou Berkman left the junk shop to start a plumbing supply company in Middletown, New York, and looked into real estate with the profits from that successful venture…. Sy Ostrow, who was taught Russian in the service so that he could function as an interpreter, returned to college and, with pained resignation, saw realistically that he had no better alternative than to study law.17

For Italian Americans, highly segregated in slum neighborhoods and routinely called “wops,” “dagoes,” and “guineas” before the war, the 1940s brought brand-new money for college and homes. Before the war, Italian Americans had rarely achieved a higher education. But around 1940 their rates of college attendance quickly approached the national norm. Educational mobility led to economic mobility, which fostered political clout. Rhode Island, with its large proportion of Italian Americans, elected John Pastore its first Italian American governor in 1946. Italian Americans in Rhode Island’s state house numbered four before 1948, when their number doubled. By the late 1960s they numbered sixteen.18 Less numerous, Slavic Americans did not succeed as brilliantly in politics, although their timetable for gaining office was similar. The first Slovenian governor of a state, Frank J. Lausche of Ohio, got elected in 1945 and was sent to the U.S. Senate in 1956.19

POSTWAR PROSPERITY drove the motor of mobility, and federal spending fueled the economy, most obviously in the form of the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, commonly called the GI Bill of Rights or simply the GI Bill. This multifaceted benefits program offered unemployment compensation, financing for education, and low-interest, fixed-rate, long-term loans for starting businesses and buying homes. Between 1944 and 1956, the GI Bill spent $14.5 billion to subsidize education for about half the veterans, some 7.8 million people all told.20*

The Federal Housing Authority (FHA), along with the Veterans Mortgage Guarantee program, offered veterans and developers federally insured mortgages and loans on terms far more favorable than those of savings and loan institutions and banks. The FHA and the Veterans Administration (VA) required only 10 percent down, and their attractively low interest rates were fixed for thirty years; people with modest incomes could pay for their homes over the long term, with no balloon payment at the end. Now it was cheaper to buy than to rent in the cities.21 An increase in home values would underlie family wealth and middle-class status in coming generations.

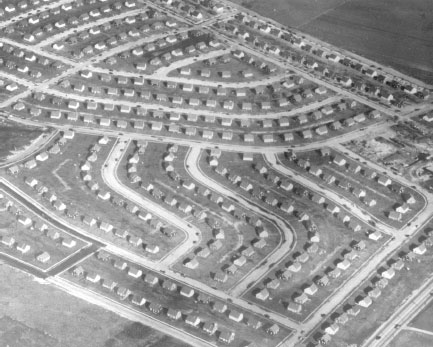

The FHA and VA financed more than $120 billion in housing between 1934 and 1964, peaking in the fifties and early sixties. By then, the FHA had become the nation’s prime mortgage lender, holding about one-half the home mortgages, and the VA had insured mortgages for nearly five million more.22 Those homes were largely in new suburbs, early and famously the two Levittowns in Nassau County, Long Island, New York (built between 1947 and 1951), and in Bucks County, Pennsylvania (built in 1951).23* (See figure 26.1, Levittown, Pennsylvania.)

Fig. 26.1. Levittown, Pennsylvania, mid-1950s.

Sameness marked the suburban theme. Even the Holocaust seldom got mention, though popular culture recognized Jews obliquely. In 1945 the first (and only) Jew was crowned Miss America after a tussle over her Jewish-sounding name—Bess Meyerson (b. 1924). The Miss America organizers had always preferred Mayflower girls and pressured Meyerson to change her name to something more One Hundred Percent American.24 But Meyerson resisted the pressure and won the crown.† Success also came to Laura Z. Hobson (1900–86), whose 1947 novel Gentleman’s Agreement became a number one best seller and an Academy Award–winning movie starring Gregory Peck as a Gentile journalist who passes for a Jew in order to expose American anti-Semitism. Biblical movies of the 1950s cast Gentiles as Jews: Charlton Heston (of English and Scottish descent) as Moses in The Ten Commandments (1956) and Victor Mature (of Italian and Swiss descent) as Samson in Samson and Delilah (1950). The war for independence of the scrappy republic of Israel in 1948 made Israelis into American revolutionaries and solidified the notion of the United States as a Judeo-Christian nation.25

Still primarily working-class, Italian Americans hovered longer on the fringes of American whiteness, longer than Jews, but the 1950s made individuals such as the singer Frank Sinatra (1915–98) and Annette Funicello (b. 1942), the star Mouseketeer of Walt Disney’s Mickey Mouse Club, into One Hundred Percent Americans who happened to be Italian. The simple and welcome point of these blockbusting books, movies, and figures—the essential sameness of Protestant, Catholic, and Jew (in the phrase of Will Herberg’s popular book)—was a theme that played well in the postwar era.* Some pointed out, however, that sameness could appear as conformity, a much less comforting idea. David Riesman’s The Lonely Crowd: A Study of the Changing American Character (1950) and William W. Whyte’s The Organization Man (1956) called attention to the anomie and conformity of the American of the postwar era on a best-selling scale. In its hardcover publication by Yale University Press and subsequent paperback abridgments, The Lonely Crowd sold more than a million copies, never mind that its American—white, northern, and middle-class—inhabited a constricted territory. Black Americans, poor Americans, and southerners of any race appear only in passing, as “remnants” of older traditions. To most Americans, these limitations seemed inconsequential. Riesman appeared on the cover of Time magazine, the first social scientist to receive this sign of national import.26

Jewish American writers—Philip Roth most notably—chronicled a transit from the old city neighborhood into the suburbs as an American, not merely a Jewish, tale. In Herman Wouk’s best-selling 1947 novel, Marjorie Morgenstern translates her quintessentially Jewish last name, into Morningstar, just as name changes, nose jobs, hair straightening, and dieting proliferated among would-be American Americans living in their “little boxes made of ticky-tacky, and they all look just the same.”

Not that sameness and conformity seemed all bad. That line from Malvina Reynolds’s 1963 hit song, “Little Boxes,” culminates a process of going to university to be doctors and lawyers and business executives. Those who “came out all the same” did so in nice, new neighborhoods, with good, new schools.27 In 1960, a quarter of the American housing stock was less than a decade old, and suburban residents in single-family homes outnumbered people living in the country or in what was coming to be denigrated as the “inner city.”28 Suburbia might be monotone, but it was a sameness to be striven toward.

Not surprisingly, suburbanization changed culture as well as residence. The literary critic Louise DeSalvo spoke for millions of postwar Jewish, Italian, and other working-class white ethnic families who used GI Bill loans to move out of the city. Her family left a fourth-floor tenement apartment in Hoboken for a home in suburban Ridgefield, New Jersey. Soon Louise’s mother began refusing to eat her immigrant mother’s homemade peasant bread, “a bread,” DeSalvo recalled, “that my mother disdains because it is everything that my grandmother is, and everything that my mother, in 1950s suburban New Jersey, is trying very hard not to be.” DeSalvo’s mother prefers commercial sliced white bread.

Maybe my mother thinks that if she eats enough of this other bread, she will stop being Italian American and she will become American American. Maybe…people will stop thinking that a relative of my father’s, who comes to visit us from Brooklyn once in a while, is a Mafioso, because he’s Italian American and has New York license plates on his new black car, and sports a black tie and pointy shoes and a shiny suit and a Borsalino hat tipped way down over his forehead so you can hardly see his eyes.29

Nor does DeSalvo, like so many of her generation, speak the European language of her immigrant grandparents. She has more in common with her Jewish and Irish American peers in the suburbs than with her cousins back in Puglia, which she did not visit until she was sixty years old. The GI Bill, the FHA, and the suburbs made her a middle-class American confronting American American ideals.

To be American American had rapidly come to mean being “middle class” and therefore white, as in the facile equation of “white” with “middle-class.” It was as though to be the one was automatically to be the other. Such a conflation of class and race had popped right out of postwar politics’ weakened organized labor, and led to dwindling visibility of the working class.

Passed after a nationwide wave of strikes in 1946, the Taft-Hartley Act of 1947 severely curbed the power of organized labor by barring sympathy strikes, secondary boycotts, and mass picketing. These tactics had stood at the heart of worker power in many a shop or industry. Now employers had the whip hand, and union growth languished. Prohibiting communists from working for unions, Taft-Hartley had also stripped organized labor of many dedicated rank-and-file organizers.30 To be prolabor came to smell like being a communist or at least a pinko, dangerous charges during the 1950s postwar red scare. Even the very image of “the working man” came to seem old-timey, as artists turned their backs on the worker as a theme. Painters invented nonfigurative abstract expressionism in a reaction against socialist realism and shopped it around internationally as proof that American art had come of age. Noteworthy prosperity inaugurated a fat new American era that generated its own mythology.

In the twilight of their years, members of the GI Bill–FHA generation looked back on their economic success with a good deal of self-congratulation. One Leonard Giuliano presented his history of his people: “With determination and perseverance…the Italian was able to…pull himself up by his own bootstraps…. His greatest desire, of course, was for his children and his family to have a better life than he had left in Italy, but he did not expect this for nothing. He had to work.” Al Riccardi told a similar story: “My people had a rough time, too. But nobody gave us something.”31 A daughter of Jewish garment workers agreed: “My grandparents were like Russian serfs, but we climbed our way out of poverty, we worked our way up. We were poor when we were growing up, but we were never on home relief, and our family still had closeness and warmth!”32 Hard work, yes, but pushed along nicely by government assistance rarely acknowledged in the aftermath.

WERE ALL boats lifted by the government’s largesse? No, they were not. Economic subsidies reached few African Americans still segregated behind a veil created and constantly mended in Washington. Those lovely new suburbs, creatures of FHA and VA mortgages, were for white people only. Federal policy made and kept them all white—on purpose.33

As in the New Deal, postwar policies crafted by a southern-dominated Congress were intended to bypass the very poor, which meant southern blacks in particular. John Rankin of Mississippi chaired the Committee on World War Legislation in the House of Representatives. He made sure that the servicemen’s bill included no antidiscrimination clause and that every provision would be administered locally along Jim Crow lines.34

In 1940, 77 percent of black Americans lived in the South. They were leaving as fast as work opened up elsewhere, but 68 percent still remained in the South in 1950. A few aggressive blacks had pushed their way into GI programs, but local agents, invariably white, had obstructed the great mass. As early as 1947 it was clear—as investigations by black newspapers and a metastudy revealed—that the GI Bill was being administered along racially discriminatory lines. It was, the report Our Negro Veteran concluded, as though the GI Bill had been intended “For White Veterans Only.”35 This color line appeared sharply in the suburbs.

The Levittowns, for instance, managed to lock out African Americans by way of “restrictive covenants,” deeds and codicils that barred an owner from selling or renting to anyone not white. (Where the rare black buyer did succeed in purchasing a house, as in Levittown in Pennsylvania, neighbors resorted to violence.) Not one of the 82,000 new inhabitants of Levittown, New York, was black, a lily-white policy that held on well into the 1960s. No matter. Time magazine featured William Levitt on its cover of 3 July 1950, and for decades discussion of suburbs like his made no mention of white-lining.36

Not that the Levittowns of America had to persuade the FHA and VA to look the other way. They had crafted federal policies advocating racial restrictions precisely in order to “preserve neighborhood stability” and prevent “Negro invasion.”37 As a result, the inner-city boroughs of New York City, for instance, received drastically less in housing subsidies than Nassau County on Long Island, where Levittown was located. Per capita lending by the FHA for mortgages was eleven times higher on Long Island than in Brooklyn and sixty times more than in the working-class Bronx. This kind of federal funding inequity affected urban families of all races, leaving cities to decay for lack of credit and to be wracked by “urban renewal” that demolished more housing than it created.38 Black families, prohibited from moving to the suburbs, had to stay behind.

By the 1960s America’s deteriorating “chocolate” cities were ringed by fresh “vanilla” suburbs. Deindustrialization aggravated conditions, as industries that had offered well-paid, union jobs to the children of immigrants in the 1940s and 1950s headed overseas. Soon the image of the “black ghetto” appeared in American commentary, and the figure of the Negro became virtually conflated with those “degenerate families” and “alien races” of the century’s first half. The civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s as well as the urban riots of the 1960s were protests against a long, dismal history of racial discrimination, segregation, unemployment, and blight, economic as well as social. Looking on from afar, comfortable suburbanites saw little more than black people acting out, despite the 1968 Kerner Commission Report, which laid it all out clearly and offered very worthy recommendations. One of them, a Fair Housing Act, Congress passed the following year, outlawing discrimination in housing.

THE FAIR Housing Act had followed two landmark pieces of civil rights legislation—the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. These were products of a black civil rights movement that had gone unnoticed by most Americans since the First World War. The March on Washington Movement of 1941 and the Second World War “Double Vee” campaign (against fascism abroad and discrimination at home) had pushed President Roosevelt into issuing Executive Order 8802 (calling for fair employment practices). In 1948 President Truman appointed the Civil Rights Commission and ran for reelection on a platform including a civil rights plank.* Of late the civil rights movement had garnered more attention when television began to cover it.

By 1960 the civil rights movement had high visibility and undoubted justice on its side. How could any American president, leader of the free world, live with segregation and disenfranchisement? John F. Kennedy did not. Rather, he embraced the cause of black civil rights. So did his successor Lyndon B. Johnson, who pushed through the mid-1960s legislation that began redressing government practices as old as the nation itself. But redress came with much pain.

By the mid-1960s the whole world watched as Americans played out their race drama on television. The angrier the speaker, the more rapt the attention. And no voice was angrier than that of Malcolm X.